Abstract

Background

Both DNA genotype and methylation of antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL) have been robustly associated with coronary artery disease (CAD), but the interdependent mechanisms of genotype and methylation remain unclear.

Methods

Eighteen tag single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of ANRIL were genotyped in a matched case–control study (cases 503 and controls 503). DNA methylation of ANRIL and the INK4/ARF locus (p14ARF, p15INK4b and p16INK4a) was measured using pyrosequencing in the same set of samples (cases 100 and controls 100).

Results

Polymorphisms of ANRIL (rs1004638, rs1333048 and rs1333050) were significantly associated with CAD (p < 0.05). The incidence of CAD, multi-vessel disease, and modified Gensini scores demonstrated a strong, direct association with ANRIL gene dosage (p < 0.05). There was no significant association between ANRIL polymorphisms and myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndrome (MI/ACS) (p > 0.05). Methylation levels of ANRIL were similar between the two studied groups (p > 0.05), but were different in the rs1004638 genotype, with AA and AT genotype having a higher level of ANRIL methylation (pos4, p = 0.006; pos8, p = 0.019). Further Spearman analyses indicated that methylation levels of ANRIL were positively associated with systolic blood pressure (pos6, r = 0.248, p = 0.013), diastolic blood pressure (pos3, r = 0.213, p = 0.034; pos6, r = 0.220, p = 0.028), and triglyceride (pos4, r = 0.253, p = 0.013), and negatively associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (pos2, r = − 0.243, p = 0.017). Additionally, we identified 12 transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) within the methylated ANRIL region, and functional annotation indicated these TFBS were associated with basal transcription. Methylation at the INK4/ARF locus was not associated with ANRIL genotype.

Conclusions

These results indicate that ANRIL genotype (tag SNPs rs1004638, rs1333048 and rs1333050) mainly affects coronary atherosclerosis, but not MI/ACS. There may be allele-related DNA methylation and allele-related binding of transcription factors within the ANRIL promoter.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12920-021-01094-8.

Keywords: ANRIL, Coronary artery disease, Single nucleotide polymorphisms, DNA methylation

Background

Current genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have added a considerable number of loci to serve as genetic markers of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction (MI)/acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Loci most frequently replicated in independently unbiased GWAS are at Chr9p21.3, Chr6p24.1, and Chr1p13.3. Chr9p21.3 stands out for its relatively large effect size, high allele frequency of more than 50% [1, 2] and ethnic diversity [3–5]. However, the causative gene for CAD at this locus is unknown. The CAD core risk region on 9p21.3 harbors no coding genes, but expresses the long non-coding RNA antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL). The closest adjacent protein-coding genes are in the INK4/ARF locus, which encodes the key tumor suppressors, p14ARF, p15INK4b and p16INK4a, and are considered as potential functional candidates [6].

Most of the 9p21.3 CAD-associated genomic variants are located within ANRIL [7], also, expression of ANRIL has been shown to associated with CAD and MI [8, 9], which makes ANRIL the most robust genetic marker of CAD today. However, inconsistent results have been reported [10]. Whether ANRIL polymorphisms are associated with the likelihood of CAD and its main effect (coronary atherosclerosis or plaque instability) on CAD remains controversial [11]. As an effector gene in 9p21.3, ANRIL can regulate its adjacent INK4/ARF locus in cis, as well as the distant loci in trans [9, 10, 12]. Causal variants at ANRIL can disrupt predicted transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) [13] and modulate ANRIL expression and/or structure [9, 14, 15], playing a pivotal role in mediating the 9p21.3 susceptibility for CVD. On the other hand, epigenetic modification, such as DNA methylation, at the ANRIL and INK4/ARF loci has been implicated in the genetic cause of CVD [16–19]. In cancer cells, transcription of ANRIL and p16INK4a is regulated by the methylation status of p16INK4a [20]. However, the relationship between polymorphism of ANRIL and DNA methylation of ANRIL and the INK4/ARF locus in CAD patients has not been examined. In this study, we systematically examined the polymorphisms of ANRIL using haplotype tag SNPs and detected their associations with CAD risk and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis, and then explored the potential relationship between the polymorphism of ANRIL and DNA methylation of ANRIL and the INK4/ARF locus in a Chinese population.

Methods

Subjects

Angiographic CAD was determined by blinded coronary angiographic analysis and defined as having > 50% diameter stenosis in at least 1 major epicardial coronary artery. Modified Gensini coronary scores were used to assess the severity of CAD [21, 22]. For a vessel to be scored, stenosis > 50% had to be noted in an epicardial coronary vessel of its major branches [23].

Subjects with other cardiac diseases (congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or rheumatic heart disease), cerebrovascular or neurological diseases, cancer, severe liver or kidney disease were excluded from the study. Furthermore, patients who had received angioplasty, intravenous thrombolysis, coronary artery stents, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery before the enrollment were also excluded.

Finally, 503 angiographic CAD cases and 503 age- (3-year bands) and sex-matched controls were selected from consecutive patients undergoing diagnostic or interventional coronary angiography within the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College from April 20, 2015 to August 20, 2016. One hundred eighty-eight MI/ACS and 188 age- (3-year bands) and sex-matched angiographic CAD controls (CAD patients without MI/ACS) were selected according to the third universal definition of myocardial infarction [24] from the same hospital during the same period. The controls were free of MI/ACS by questionnaires, history-taking, detection of troponin-T and myocardial enzymes, electrocardiography, chest X-ray, and Doppler echocardiography.

Demographic and clinical data required for this study were obtained from physician and hospital records, and included age, sex, health history (CAD, MI/ACS, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia), vital signs at entry, medication use, personal hobbies (smoking, alcohol use), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), triglycerides (TG), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbAlc), creatinine, uric acid, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP).

All subjects were from the Chinese Han population and gave informed consent prior to the study. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College.

SNP selection and genotyping

An arterial blood sample was taken at the time of the catheterization for deoxyribonucleic acid extraction and subsequent genotyping. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid was isolated with a FlexGen Blood DNA Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (CoWin Biosciences). Eighteen tag SNPs of ANRIL were selected by Haploview software (Version 4.1). The minor allele frequency of each SNP was > 5% in the HapMap of the Chinese Han Beijing (CHB) population (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Genotyping was performed with the Access Array micro-fluidics PCR platform (Fluidigm Corporation, South San Francisco, California, USA) according to the standard instructions [25]. Fluidigm SNP Genotyping Analysis (Version 4.3.2) software was used for data management and analyses.

Methylation analysis of ANRIL, p14ARF, p15INK4b and p16INK4a

Genomic DNA was isolated as mentioned above. Bisulfite treatment of DNA was done by using the EZ DNA MethylationTM kit (ZYMO Research, Orange, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then the resulting bisulfite-treated DNA was purified and eluted in 20 μl of M-elution buffer, and 4 μl of this was used in the methylation-specific PCR (MSP) amplification. Primers for MSP amplification were designed with the use of the bioinformatics program (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/index1.html) and are shown in Additional file 1: Table S2. After amplification, the MSP products were analyzed by bisulfite pyrosequencing (PyroMark Q96 System version 2.0.6, Qiagen).

Functional annotation of the ANRIL methylation region

PROMO (version 8.3 of TRANSFAC) was used to predict the putative TFBS within the ANRIL methylation region. The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v6.8 was used to annotate the function of the predicted TFBS. Pathways that were potentially affected by gene DNA methylation were generated by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp© 2010) and SNPassoc for R statistical package were used for statistical analyses. Haploview software (version 4.1) was used for analyses of the pairwise linkage disequilibrium, haplotype structure and selecting tagging SNPs. All p-values were two sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Continuous variables were reported as the mean value ± standard deviation (SD). Data with a normal distribution were compared by Student t test or ANOVA test, and those with unequal variance or without a normal distribution were analyzed by a Mann–Whitney rank sum test or Spearman correlation test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies with percentages and were compared by the chi-squared (χ2) test. A trend test was also examined by the χ2 test (linear-by-linear association). Genotypic frequencies in cases and controls were tested for departure from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium using a Fisher’s exact test. Genetic model analyses (dominant, recessive) were applied to assess the significance of SNPs, and the allelic frequencies were compared between cases and controls by χ2/Fisher’s exact test. The associations between CAD and genotypes of the SNPs were estimated by computing the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from the multivariable logistic regression, and adjusted for sex, age, smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, blood lipid (TC, TG, HDL, LDL), creatinine and uric acid.

Results

General characteristics of the subjects

The main demographic and clinical characteristics of the CAD cases and controls are summarized in Table 1. Mean age of the cases was 59.67 years old (from 39 to 87), mean age of the controls was 60.42 years old (from 33 to 85), there was no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.198). As expected, other traditional risk factors, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia were more prevalent in cases than the controls (p < 0.05). Accordingly, mean levels of SBP, HbAlc, TG and HDL were significantly different between the two groups (p < 0.05). DBP, TC and LDL did not differ between the cases and controls (p > 0.05), which could be the result of antihypertensive and cholesterol-lowering drugs in the patients after diagnosis.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the CAD cases and controls

| Variables | Case (n = 503) | Control (n = 503) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical variables, n (%) | |||

| Male | 311 (61.83) | 291 (57.85) | 0.222 |

| Smoking | 212 (42.15) | 180 (35.79) | 0.047 |

| Alcohol use | 52 (10.34) | 44 (8.75) | 0.396 |

| Hypertension | 390 (77.53) | 317 (63.02) | < 0.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 258 (51.29) | 149 (29.62) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 347 (68.99) | 303 (60.24) | 0.006 |

| Continuous variables, mean ± SD | |||

| Age (years) | 59.67 ± 9.85 | 60.42 ± 9.08 | 0.198 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 139.47 ± 23.09 | 136.57 ± 20.91 | 0.037 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 82.93 ± 12.82 | 83.38 ± 12.80 | 0.583 |

| HbAlc (%) | 5.66 ± 2.92 | 4.66 ± 2.82 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.76 ± 1.38 | 4.87 ± 1.09 | 0.383 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.60 ± 1.33 | 1.41 ± 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.09 ± 0.32 | 1.20 ± 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.16 ± 1.04 | 3.24 ± 0.85 | 0.594 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 104.08 ± 86.98 | 94.15 ± 31.89 | 0.017 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 397.46 ± 109.56 | 383.26 ± 111.30 | 0.048 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; SD: standard deviation; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Association of ANRIL genotype with CAD

Of the 18 tag SNPs, rs10965227 and rs10965241 did not conform to the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test in controls and cases (see Additional file 1: Table S1), and so were not used for further analysis. Univariate analyses found 5 SNPs (rs1004638, rs1333048, rs1333050, rs4977756, rs9632885) to be significantly associated with CAD (see Additional file 1: Table S3), while the other 11 SNPs had no association with CAD (data not shown).

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, after adjusting for conventional CAD risk factors such as sex, age, smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia, we found 3 SNPs (rs1004638, rs1333048 and rs1333050) significantly associated with CAD (Table 2). rs1004638 showed a large effect size both in heterozygotes (AT, OR = 2.13, 95% CI 1.34–3.40) and homozygotes (AA, OR = 2.50 (95% CI 1.58–3.95). rs1333048 showed a modest effect size in heterozygotes (AC, OR = 1.38, 95% CI 1.01–1.88) and was exaggerated in homozygotes (CC, OR = 2.02 (95% CI 1.40–2.91). rs1333050 showed no effect size in heterozygotes (CT, OR = 1.21, 95% CI 0.88–1.66), but was exaggerated in homozygotes (TT, OR = 1.58 (95% CI 1.09–2.28). The combined rs1004638 AA + AT genotypes (OR = 2.32, 95% CI 1.49–3.62), rs1333048 AC + CC genotypes (OR = 1.56, 95% CI 1.16–2.09), and rs1333050 CT + TT genotypes (OR = 1.32, 95% CI 0.97–1.78) had 2.32-, 1.56-, and 1.32-fold higher CAD risk respectively, compared with the rs1004638 TT, rs1333048 AA, and rs1333050 CC genotypes. For the risk allele A, C, T of the three SNPs, the adjusted ORs of CAD were 1.39 (95% CI 1.15–1.69), 1.40 (95% CI 1.17–1.67), and 1.24 (95% CI 1.04–1.48), respectively. There were dose–response effects of rs1004638 A, rs1333048 C, and rs1333050 T alleles with CAD (Ptrend = 0.008, 0.001, and 0.027, respectively).

Table 2.

Odds ratios of ANRIL tag SNPs for CAD by multivariable logistic regression analysis

| SNP | Model | Cases (n) | Controls (n) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1004638 | Genotype | TT (Ref.) | 27 | 68 | 1 | |

| AT | 206 | 208 | 2.13 (1.34–3.40) | 0.001 | ||

| AA | 268 | 225 | 2.50 (1.58–3.95) | < 0.001 | ||

| AT + AA | 474 | 433 | 2.32 (1.49–3.62) | < 0.001 | ||

| Ptrend | 0.008 | |||||

| Allele | T (Ref.) | 260 | 344 | 1 | ||

| A | 742 | 658 | 1.39 (1.15–1.69) | < 0.001 | ||

| rs1333048 | Genotype | AA (Ref.) | 104 | 141 | 1 | |

| AC | 249 | 259 | 1.38 (1.01–1.88) | 0.044 | ||

| CC | 147 | 97 | 2.02 (1.40–2.91) | < 0.001 | ||

| AC + CC | 396 | 356 | 1.56 (1.16–2.09) | 0.003 | ||

| Ptrend | 0.001 | |||||

| Allele | A (Ref.) | 457 | 541 | 1 | ||

| C | 543 | 453 | 1.40 (1.17–1.67) | < 0.001 | ||

| rs1333050 | Genotype | CC (Ref.) | 101 | 124 | 1 | |

| CT | 259 | 265 | 1.21 (0.88–1.66) | 0.242 | ||

| TT | 142 | 109 | 1.58 (1.09–2.28) | 0.015 | ||

| CT + TT | 401 | 374 | 1.32 (0.97–1.78) | 0.074 | ||

| Ptrend | 0.027 | |||||

| Allele | C (Ref.) | 461 | 513 | 1 | ||

| T | 541 | 483 | 1.24 (1.04–1.48) | 0.018 | ||

Ref.: reference variable; CAD: coronary artery disease; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. Trend test was examined by χ2 test (linear-by-linear association)

The linkage disequilibrium was defined as D ≥ 95, and five haplotype blocks were identified in the ANRIL region (see Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Haplotype analysis found blocks 1, 2, 3, and 5 were not significantly associated with CAD. rs1004638 and rs1333048 showed strong linkage in block 4, and the haplotype AC (A, C are the risk alleles of rs1004638 and rs1333048, respectively) was significantly associated with an increased risk of CAD (OR = 1.42, 95% CI 1.22–1.66; p < 0.001).

Effect of ANRIL genotype on CAD severity and MI/ACS

There was a strong positive association between the incidence of CAD and increasing gene dose of the rs1004638 (p < 0.001), rs1333048 (p < 0.001) and rs1333050 (p = 0.034) risk variants. Multi-vessel disease (p = 0.027) increased as increasing gene dosage of rs1333048 risk variant. Gensini scores in the mutant homozygote of rs1333048 (CC, p < 0.001) and rs1333050 (TT, p = 0.001) were significantly higher than that of the heterozygote or wild-type homozygote. Patients with two hazardous alleles of ANRIL were more likely to suffer severe CAD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of gene dosage of ANRIL tag SNPs with CAD severity

| SNP | Genotype/p-value | CAD, n (%) | Criminal Vessels, n (%) | Gensini scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Multi-VD | 1-VD | n | Mean ± SD | ||

| rs1004638 | TT | 27 (28.42) | 68 (71.58) | 15 (55.56) | 12 (44.44) | 27 | 37.17 ± 34.28 |

| AT | 206 (49.76) | 208 (50.24) | 131 (63.59) | 75 (36.41) | 205 | 37.36 ± 32.62 | |

| AA | 268 (54.36) | 225 (45.64) | 183 (68.28) | 85 (31.72) | 268 | 41.93 ± 34.08 | |

| P | < 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.313 | ||||

| rs1333048 | AA | 104 (42.45) | 141 (57.55) | 63 (60.58) | 41 (39.42) | 104 | 34.47 ± 30.52 |

| AC | 249 (49.02) | 259 (50.98) | 158 (63.45) | 91 (36.55) | 248 | 36.69 ± 32.78 | |

| CC | 147 (60.25) | 97 (39.75) | 107 (72.79) | 40 (27.21) | 147 | 49.01 ± 35.16 | |

| P | < 0.001 | 0.027 | < 0.001 | ||||

| rs1333050 | CC | 101 (44.89) | 124 (55.11) | 66 (65.35) | 35 (34.65) | 101 | 36.96 ± 32.39 |

| CT | 259 (49.43) | 265 (50.57) | 162 (62.55) | 97 (37.45) | 258 | 36.11 ± 31.51 | |

| TT | 142 (56.57) | 109 (43.43) | 102 (71.83) | 40 (28.17) | 142 | 48.61 ± 36.24 | |

| P | 0.034 | 0.172 | 0.001 | ||||

CAD: coronary artery disease; Multi-VD: multi-vessel disease; 1-VD: 1-vessel disease. SD: standard deviation

In addition, we performed a stratified analysis by age. Premature CAD (PCAD) in this study was defined as CAD occurring in males < 55 years of age and females < 65 years of age [26]. Accordingly, late-onset CAD (LCAD) was defined as males ≥ 55 years of age and females ≥ 65 years of age. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that there were appreciably higher ORs for the risk alleles in the PCAD set (p < 0.05) when compared with the LCAD set (p ≥ 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Odds ratios of ANRIL tag SNPs for PCAD and LCAD by multivariable logistic regression analysis

| SNP | Genotype | PCAD | LCAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| rs1004638 | TT (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| AT | 6.32 (2.27–17.61) | < 0.001 | 1.98 (1.01–3.87) | 0.047 | |

| AA | 6.14 (2.19–17.16) | 0.001 | 1.43 (0.73–2.83) | 0.301 | |

| rs1333048 | AA (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| AC | 2.19 (1.26–3.78) | 0.005 | 0.88 (0.56–1.38) | 0.568 | |

| CC | 2.77 (1.46–5.24) | 0.002 | 1.55 (0.92–2.60) | 0.098 | |

| rs1333050 | CC (Ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| CT | 1.65 (0.96–2.85) | 0.072 | 1.03 (0.69–1.55) | 0.873 | |

| TT | 2.30 (1.21–4.36) | 0.011 | 1.28 (0.81–2.02) | 0.296 | |

Ref.: reference variable; PCAD: premature CAD; LCAD: late-onset CAD; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

To explore the effect of ANRIL on plaque instability, another case–control study (188 MI/ACS and 188 age- (3-year bands) and sex-matched CAD controls) was carried out. The results showed that there was no association between ANRIL tag SNPs and MI/ACS (p > 0.05) (see Additional file 1: Table S4).

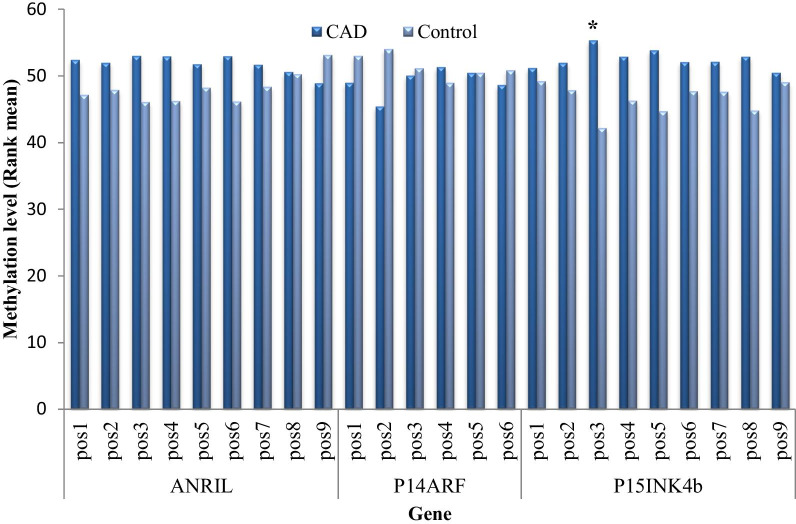

Methylation of ANRIL, p14ARF, p15INK4b and p16INK4a in the study population

To further explore the possible molecular mechanism of CAD, we assessed DNA methylation of the ANRIL, p14ARF, p15INK4b and p16INK4a promoter region in CAD and control subjects. The one-sample K–S test was used to test the normality of DNA methylation levels, and it was found that the data did not conform to a normal distribution, so the Mann Whitney rank sum test was used to compare the differences between groups. As shown in Fig. 1, only one CpG site within the third CpG island (pos3) located upstream of p15INK4b was hyper-methylated in CAD subjects compared to the matched controls (p = 0.025). No differences in ANRIL or p14ARF methylation were observed (P > 0.05). Methylation of p16INK4a was at barely detectable levels in both CAD patients and controls, so the data was not shown.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of methylation level of ANRIL, P14ARF and P15INK4b in CAD patients and controls. pos: methylation sites; *p value < 0.05

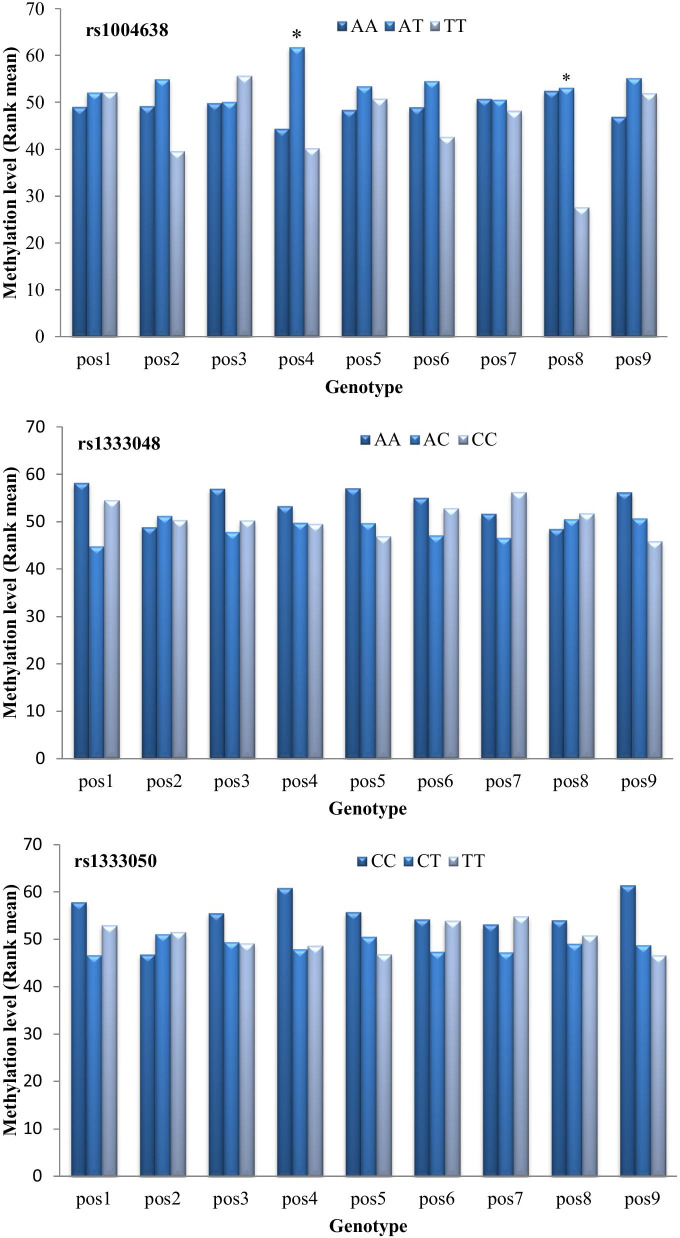

Association of ANRIL genotype with methylation

Further, we assessed the association between CAD risk genotypes and methylation of ANRIL, p14ARF and p15INK4b. CAD-associated rs1004638 was associated with methylation of ANRIL. Compared with carriers of TT genotypes, AA and TT genotype carriers of rs1004638 had markedly elevated levels of methylation [ANRIL pos4 (p = 0.006) and pos8 (p = 0.019)]. rs1333048 and rs1333050 had no effect on the methylation level of ANRIL (Fig. 2). There were no differences between CAD-associated SNPs (rs1004638, rs1333048, rs1333050) and methylation of p14ARF or p15INK4b (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Association of ANRIL polymorphisms (rs1004638, rs1333048, rs1333050) with ANRIL methylation. pos: methylation sites; *p value < 0.05

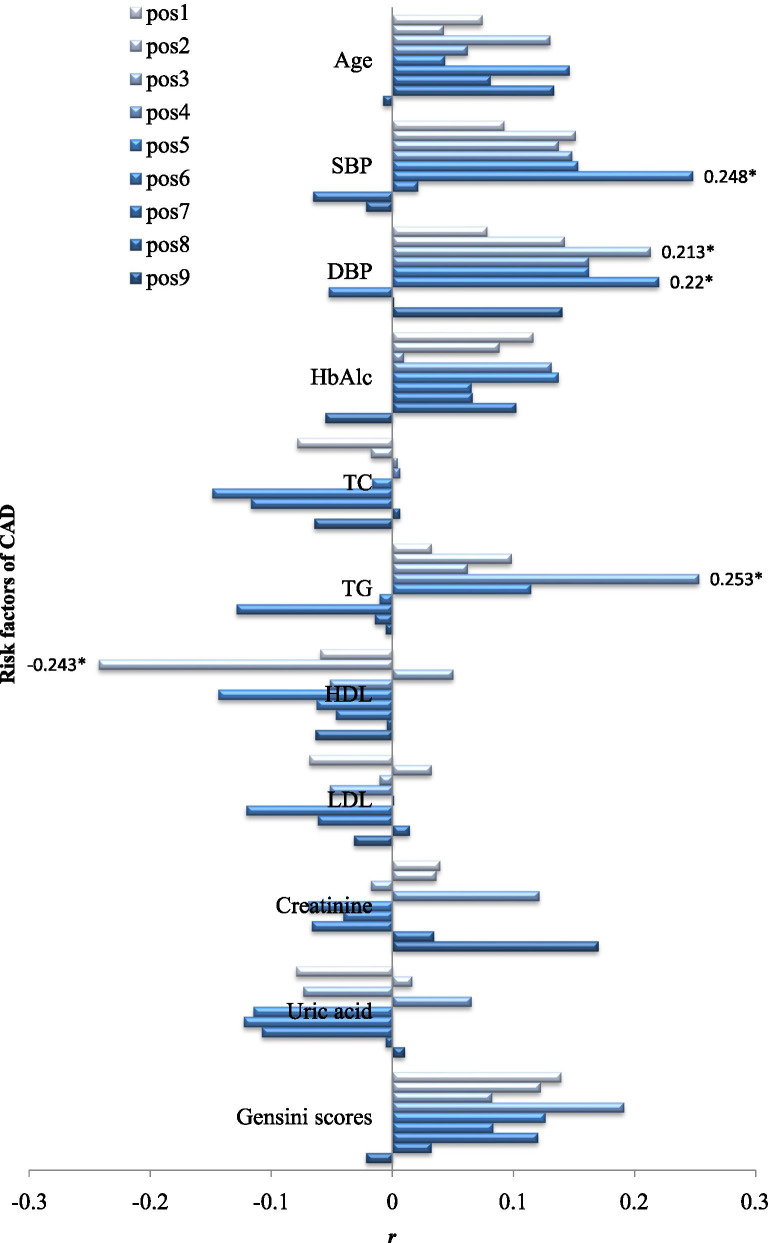

Correlation between ANRIL methylation and risk factors of CAD

Figure 3 shows the results of correlation analyses between ANRIL methylation and risk factors of CAD. Spearman analyses indicated that ANRIL methylation levels were positively associated with SBP (pos6, r = 0.248, p = 0.013), DBP (pos3, r = 0.213, p = 0.034; pos6, r = 0.220, p = 0.028), and TG (pos4, r = 0.253, p = 0.013), and negatively associated with HDL (pos2, r = − 0.243, p = 0.017).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between ANRIL methylation and risk factors for CAD. Correlation coefficients with statistical significance are listed in the figure. pos: methylation sites; *p value < 0.05; r: Spearman correlation coefficient; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglyceride; HDL: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

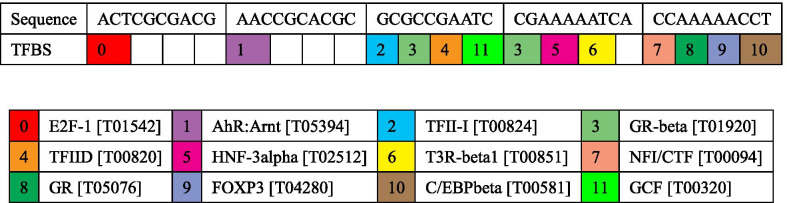

Functional annotation of ANRIL methylation region

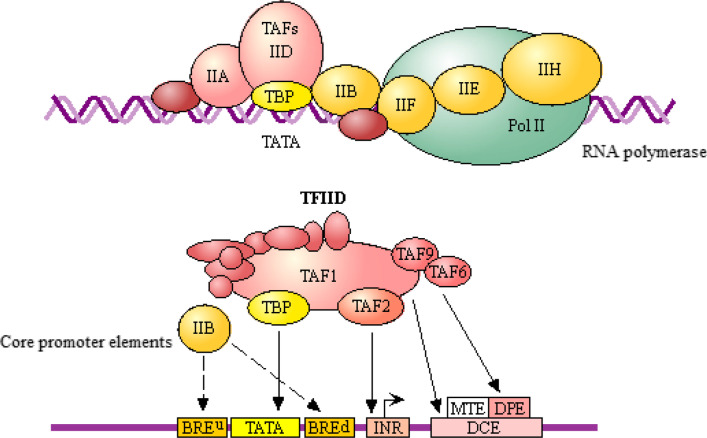

We predicted 12 TFBS in DNA sequences within the ANRIL methylation region (Fig. 4). Functional annotation by KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated these TFBS-binding sites were associated with basal transcription (Fig. 5). Among them, transcription factor IID (TFIID) was identified as a key transcription factor, which is composed of the TATA-binding protein and binds to the core promoter to position the RNA polymerase II properly, serves as the scaffold for assembly of the remainder of the transcription complex, and acts as a channel for regulatory signals [27–30].

Fig. 4.

Predicted TFBS in DNA sequences within the ANRIL methylated region. Numbers in the colored boxes of the upper panel refer to the binding site of different transcription factors. E2F: transcription factor 1 (Gene ID: 1869); AhR: aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Gene ID: 196); Arnt: aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (Gene ID: 405); TFII-I: general transcription factor Iii (Gene ID: 2969); GR-beta: nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (Gene ID: 2908); TFIID: TATA box-binding protein (Gene ID: 6908); HNF-3alpha: forkhead box A1 (Gene ID: 3169); T3R-beta1: thyroid hormone receptor alpha (Gene ID: 7067); NFI/CTF: nuclear factor I C (Gene ID: 4782); GR: nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (Gene ID: 2908); FOXP3: forkhead box P3 (Gene ID: 50943); C/EBPbeta: CCAAT enhancer binding protein beta (Gene ID: 1051); GCF: GC-rich sequence DNA-binding factor 2 (Gene ID: 6936)

Fig. 5.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the ANRIL methylated region. General transcription factors for RNA polymerase II. TFIID is composed of TATA-binding protein (TBP) and a number of TBP-associated factors (TAFs). Pol II: RNA polymerase II; TAF: TATA box-binding protein-associated factor; TBP: TATA box-binding protein; BRE: TFIIB recognition element; DPE: downstream promoter element; INR: initiator; DCE: downstream core components; MTE: motif ten elements

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that: (1) tag SNPs (rs1004638, rs1333048, rs1333050) of ANRIL significantly influence the hazard of CAD in a Chinese Han population. Homozygous carriers showed higher coronary atherosclerosis risk, whereas heterozygous carriers showed intermediate risk between that of wild-type and homozygous carriers, indicating a genetic dose effect, especially for premature CAD. (2) ANRIL polymorphism was significantly associated with CAD severity, but not MI/ACS. (3) DNA methylation levels of ANRIL were not associated with CAD, but were associated with rs1004638 and CAD risk factors (SBP, DBP, TG and HDL). (4) Twelve TFBS were predicted within the ANRIL methylation region. These findings indicate that there may be allele-related DNA methylation and allele-related binding of transcription factors within the ANRIL promoter region.

Our results are consistent with previous studies conducted in China and other populations in which ANRIL polymorphisms were found to be associated with CAD [11, 31]. A quantitative assessment of the severity of coronary stenosis is better than a binary phenotype [32], while previous studies found that ANRIL confers risk for CAD vs. controls. So, a validated semi-quantitative angiographic score, Gensini scores, was used to estimate severity of CAD in this study. Our results showed a dose–effect relationship between the Gensini scores and ANRIL risk alleles. Homozygotes of the rs1333048 risk allele are more likely (72.79%) to suffer multi-vessel disease than wild-type carriers (60.58%), thus providing clues for predicting severity of CAD.

Considering that ANRIL is related to the degree of coronary stenosis, we wondered whether it is also related to MI/ACS. MI/ACS patients are prone to suffer multiple vessel lesions [23]. Over 50% of ST-segment elevation MI patients have multiple vessel lesions, which indicates poor prognosis [33]. However, our results demonstrate that there is no association between ANRIL and MI/ACS when both cases and controls have coronary stenosis. Such an analytical method has been used in previous studies as a means to distinguish the effect of genetic factors on CAD from MI [34]. However, by comparing MI cases with healthy controls, Abdul Azeez et al. [35] and Cheng et al. [36] did not distinguish the effect of ANRIL on CAD and MI, but showed that ANRIL is associated with MI in both the Saudi population and Chinese Han population. Given that MI is a more downstream phenotype of CAD, comparisons between MI and healthy controls means comparing CAD with non-CAD. Hence, it can be considered that ANRIL mainly influences coronary atherosclerosis, instead of MI/ACS, which is pathophysiologically distinct from CAD [37].

Risk factors for CAD are both environmental and genetic. PCAD has a stronger genetic susceptibility [38], and heritability of PCAD is more obvious than that of the LCAD [39]. We observed an appreciably higher OR for the risk alleles of ANRIL in PCAD individuals compared with the LCAD individuals. Previous evidence has reported the associations of 9p21 SNPs with PCAD in different populations [40, 41]. Our results may favor prediction of PCAD by providing new SNPs.

Epigenetics has been shown to play an important role in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is even regarded as an epigenetic disease [42]. Among different epigenetic mechanisms, DNA methylation is the key epigenetic process for CAD and its risk factors [43]. Our results show that p15INK4b, but not p14ARF or p16INK4a, is hypermethylated in CAD cases, consistent with the study of Zhuang et al. [19]. DNA methylation of ANRIL has been reported as an important epigenetic regulatory factor in mediating CAD [16], adiposity [18] and cardiovascular risk [17]. However, its relation with ANRIL polymorphism has not been reported. In the post-GWAS era, increasingly evidence has suggested a complex relationship between SNP, allele-specific binding of transcription factors, and allele-specific DNA methylation for disease risk [44].

Our results found that methylation levels of ANRIL are similar between the cases and controls (p > 0.05), but are different for the rs1004638 genotype, where AA and AT had a higher level of ANRIL methylation (p < 0.05). Furthermore, correlation analysis found ANRIL methylation levels are significantly associated with risk factors for CAD, and functional annotation indicates that the ANRIL methylated region has binding sites for transcription factors that are associated with basal transcription. These results showed there may be allele-related DNA methylation and allele-related binding of transcription factors within the ANRIL promoter. ANRIL may cause CAD via allele-related binding of transcription factors or allele-related gene expression. As for the role of allele-related DNA methylation, the mediator or the phenotype of CAD, further prospective studies are needed to explore this. Previous methylation quantitative-trait loci (met QTL) analyses also revealed that DNA methylation is under strong genetic influence [45] and most effective methylation is associated with nearby SNPs [46–48].

Methylation of p15INK4b or p14ARF is not affected by ANRIL genotype. Zhuang et al. also found that methylation of the INK4/ARF locus is not affected by SNPs in the ANRIL locus (typified by rs10757274) [19]. This led Lillycrop et al. to speculate that both risk genotype of ANRIL (rs10757274) and methylation of the INK4/ARF locus independently affect ANRIL expression to mediate disease risk [18]. We are in favor of this hypothesis.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the relatively large number of participants with definite diagnosis and detailed clinical characteristics. On the other hand, the genetic (genotype) and epigenetic (methylation) association analysis are from the same set of samples. There are some potential limitations. First, our study is only a preliminary study with just the results of association analysis. Further cellular and molecular experiments are warranted to validate the specific mechanism. Second, the epigenome is dynamic as the environment changes and due to the heterogeneity of patients and variations in therapies, so it is probably inappropriate to extend the present research results to other cells or tissues. Finally, our study is a case–control and cross-sectional design study. Whether methylation of ANRIL is a driver of CAD or a consequence of CAD requires further evaluation. Dynamic detection of ANRIL methylation before and after the occurrence of CAD would be a better choice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings indicate that polymorphisms of ANRIL (rs1004638, rs1333048 and rs1333050) might serve as a genetic biomarker of CAD, but not MI/ACS. There may be allele-related DNA methylation and allele-related binding of transcription factors within the ANRIL promoter. Our study provides new mechanistic insight into the regulation of ANRIL. Further studies are warranted to illustrate potential mechanisms for crosstalk of genetic factors, allele-related DNA methylation, and allele-related binding of transcription factors.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Linkage disequilibrium structure and haplotype blocks of ANRIL in the Chinese population. Table S1. ANRIL tag SNP genotyping assay and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test. Table S2. Primer sequences for ANRIL, P14ARF, P15INK4b and p16INK4a. Table S3. Genetic model analysis of the association of ANRIL tag SNPs with CAD risk. Table S4. Association of ANRIL tag SNPs with MI/ACS risk.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants for donating their blood for this study. We would like to thank colleagues of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, for their generous help in peripheral blood collection and clinical parameters detection for this study. We would also like to thank Dr. Stanley Li Lin, Department of Cell Biology and Genetics, Shantou University Medical College, for his helpful comments and English language editing.

Abbreviations

- ANRIL

Antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- PCAD

Premature CAD

- LCAD

Late-onset CAD

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- SD

Standard deviation

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TFBS

Transcription factor binding sites

Authors' contributions

B.X. and X.T. conceived the research question. Y.C. and Z.S. carried out the diagnostic or interventional coronary angiography. Z.S. carried out coronary angiographic analysis and assessed the severity of CAD. Z.X. and N.L. carried out the sample collection, data management and analysis. B.X. performed the DNA isolation, genotyping and methylation detection. B.X. and Z.X. completed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangdong Medical Research Foundation [No. A2019280 (BX)] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 81473063 (XT)].

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript except for the raw sequence data. Any data providing genotype information is considered to be personal property by Chinese law, hence the submission to public achieves is prohibited. The raw sequence data can be acquired upon reasonable request from the authors (xubayi81@qq.com) if approval could be granted from the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. All protocols were carried out in accordance with clinical research guidelines and regulations of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College. All participants signed informed consent voluntarily prior to the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Holdt LM, Teupser D. From genotype to phenotype in human atherosclerosis—recent findings. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24(5):410–418. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283654e7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts R, Stewart AF. 9p21 and the genetic revolution for coronary artery disease. Clin Chem. 2012;58(1):104–112. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.172759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, Cox DR, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316(5830):1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Gretarsdottir S, Blondal T, Jonasdottir A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316(5830):1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng X, Shi L, Nie S, Wang F, Li X, Xu C, et al. The same chromosome 9p21.3 locus is associated with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease in a Chinese Han population. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):680–684. doi: 10.2337/db10-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hannou SA, Wouters K, Paumelle R, Staels B. Functional genomics of the CDKN2A/B locus in cardiovascular and metabolic disease: what have we learned from GWASs? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(4):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Congrains A, Kamide K, Oguro R, Yasuda O, Miyata K, Yamamoto E, et al. Genetic variants at the 9p21 locus contribute to atherosclerosis through modulation of ANRIL and CDKN2A/B. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220(2):449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunnington MS, Santibanez Koref M, Mayosi BM, Burn J, Keavney B. Chromosome 9p21 SNPs associated with multiple disease phenotypes correlate with ANRIL expression. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(4):e1000899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holdt LM, Beutner F, Scholz M, Gielen S, Gabel G, Bergert H, et al. ANRIL expression is associated with atherosclerosis risk at chromosome 9p21. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(3):620–627. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holdt LM, Teupser D. Recent studies of the human chromosome 9p21 locus, which is associated with atherosclerosis in human populations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(2):196–206. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Y, Zhao D, Dong P, Wang H, Li D, Lai L. Effects of ANRIL polymorphisms on the likelihood of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(4):6113–6119. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holdt LM, Hoffmann S, Sass K, Langenberger D, Scholz M, Krohn K, et al. Alu elements in ANRIL non-coding RNA at chromosome 9p21 modulate atherogenic cell functions through trans-regulation of gene networks. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(7):e1003588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harismendy O, Notani D, Song X, Rahim NG, Tanasa B, Heintzman N, et al. 9p21 DNA variants associated with coronary artery disease impair interferon-gamma signalling response. Nature. 2011;470(7333):264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature09753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burd CE, Jeck WR, Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Wang Z, Sharpless NE. Expression of linear and novel circular forms of an INK4/ARF-associated non-coding RNA correlates with atherosclerosis risk. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(12):e1001233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai Y, Nie S, Jiang G, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Zhao Y, et al. Regulation of CARD8 expression by ANRIL and association of CARD8 single nucleotide polymorphism rs2043211 (p.C10X) with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(2):383–388. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao CH, Cao HT, Zhang J, Jia QW, An FH, Chen ZH, et al. DNA methylation of antisense noncoding RNA in the INK locus (ANRIL) is associated with coronary artery disease in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15340. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51921-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray R, Bryant J, Titcombe P, Barton SJ, Inskip H, Harvey NC, et al. DNA methylation at birth within the promoter of ANRIL predicts markers of cardiovascular risk at 9 years. Clin Epigenet. 2016;8:90. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0259-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lillycrop K, Murray R, Cheong C, Teh AL, Clarke-Harris R, Barton S, et al. ANRIL promoter DNA methylation: a perinatal marker for later adiposity. EBioMedicine. 2017;19:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhuang J, Peng W, Li H, Wang W, Wei Y, Li W, et al. Methylation of p15INK4b and expression of ANRIL on chromosome 9p21 are associated with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gan Y, Ma W, Wang X, Qiao J, Zhang B, Cui C, et al. Coordinated transcription of ANRIL and P16 genes is silenced by P16 DNA methylation. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30(1):93–103. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2018.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Veglia F, Briganti A, et al. Association between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Role of coronary clinical presentation and extent of coronary vessels involvement: the COBRA trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2632–2639. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(3):606. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(83)80105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dandona S, Stewart AF, Chen L, Williams K, So D, O'Brien E, et al. Gene dosage of the common variant 9p21 predicts severity of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(6):479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver JM, Ross-Innes CS, Shannon N, Lynch AG, Forshew T, Barbera M, et al. Ordering of mutations in preinvasive disease stages of esophageal carcinogenesis. Nat Genet. 2014;46(8):837–843. doi: 10.1038/ng.3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen B, Xie F, Tang C, Ma G, Wei L, Chen Z. Study of five pubertal transition-related gene polymorphisms as risk factors for premature coronary artery disease in a Chinese Han population. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravarani CNJ, Flock T, Chavali S, Anandapadamanaban M, Babu MM, Balaji S. Molecular determinants underlying functional innovations of TBP and their impact on transcription initiation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2384. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardiville S, Banerjee PS, Selen Alpergin ES, Smith DM, Han G, Ma J, et al. TATA-box binding protein O-GlcNAcylation at T114 regulates formation of the B-TFIID complex and is critical for metabolic gene regulation. Mol Cell. 2020;77(5):1143–52.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav D, Ghosh K, Basu S, Roeder RG, Biswas D. Multivalent role of human TFIID in recruiting elongation components at the promoter-proximal region for transcriptional control. Cell Rep. 2019;26(5):1303–17.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel AB, Louder RK, Greber BJ, Grunberg S, Luo J, Fang J, et al. Structure of human TFIID and mechanism of TBP loading onto promoter DNA. Science. 2018;362(6421):eaau8872. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu L, Su G, Wang X. The roles of ANRIL polymorphisms in coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 2019;39:BSR20181559. doi: 10.1042/BSR20181559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel RS, Su S, Neeland IJ, Ahuja A, Veledar E, Zhao J, et al. The chromosome 9p21 risk locus is associated with angiographic severity and progression of coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(24):3017–3023. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widimsky P, Holmes DR., Jr How to treat patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction and multi-vessel disease? Eur Heart J. 2011;32(4):396–403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan K, Patel RS, Newcombe P, Nelson CP, Qasim A, Epstein SE, et al. Association between the chromosome 9p21 locus and angiographic coronary artery disease burden: a collaborative meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(9):957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AbdulAzeez S, Al-Nafie AN, Al-Shehri A, Borgio JF, Baranova EV, Al-Madan MS, et al. Intronic polymorphisms in the CDKN2B-AS1 gene are strongly associated with the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease in the Saudi population. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):395. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng J, Cai MY, Chen YN, Li ZC, Tang SS, Yang XL, et al. Variants in ANRIL gene correlated with its expression contribute to myocardial infarction risk. Oncotarget. 2017;8(8):12607–12619. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horne BD, Anderson JL. Irrelevance of the chromosome 9p213 locus for acute cardiovascular events and restenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(11):1156–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen GQ, Girelli D, Li L, Rao S, Archacki S, Olivieri O, et al. A novel molecular diagnostic marker for familial and early-onset coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction in the LRP8 gene. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014;7(4):514–520. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nora JJ, Lortscher RH, Spangler RD, Nora AH, Kimberling WJ. Genetic–epidemiologic study of early-onset ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1980;61(3):503–508. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.61.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beckie TM, Groer MW, Beckstead JW. The relationship between polymorphisms on chromosome 9p21 and age of onset of coronary heart disease in black and white women. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15(6):435–442. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Qian Q, Ma G, Wang J, Zhang X, Feng Y, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of early-onset coronary artery disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36(5):889–893. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu S, Pelisek J, Jin ZG. Atherosclerosis is an epigenetic disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(11):739–742. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan L, Hu J, Xiong X, Liu Y, Wang J. The role of DNA methylation in coronary artery disease. Gene. 2018;646:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Lou D, Wang Z. Crosstalk of genetic variants, allele-specific DNA methylation, and environmental factors for complex disease risk. Front Genet. 2018;9:695. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu YH, Wang BH, Jiang F, Mo XB, Wu LF, He P, et al. Multi-omics integrative analysis identified SNP-methylation-mRNA: interaction in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(7):4601–4610. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grundberg E, Meduri E, Sandling JK, Hedman AK, Keildson S, Buil A, et al. Global analysis of DNA methylation variation in adipose tissue from twins reveals links to disease-associated variants in distal regulatory elements. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93(5):876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClay JL, Shabalin AA, Dozmorov MG, Adkins DE, Kumar G, Nerella S, et al. High density methylation QTL analysis in human blood via next-generation sequencing of the methylated genomic DNA fraction. Genome Biol. 2015;16:291. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harris RA, Nagy-Szakal D, Pedersen N, Opekun A, Bronsky J, Munkholm P, et al. Genome-wide peripheral blood leukocyte DNA methylation microarrays identified a single association with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(12):2334–2341. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Linkage disequilibrium structure and haplotype blocks of ANRIL in the Chinese population. Table S1. ANRIL tag SNP genotyping assay and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test. Table S2. Primer sequences for ANRIL, P14ARF, P15INK4b and p16INK4a. Table S3. Genetic model analysis of the association of ANRIL tag SNPs with CAD risk. Table S4. Association of ANRIL tag SNPs with MI/ACS risk.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript except for the raw sequence data. Any data providing genotype information is considered to be personal property by Chinese law, hence the submission to public achieves is prohibited. The raw sequence data can be acquired upon reasonable request from the authors (xubayi81@qq.com) if approval could be granted from the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College.