Abstract

Objective:

To describe a founder mutation effect and the clinical phenotype of homozygous FRRS1L c.737_739delGAG (p.Gly246del) variant in 15 children of Puerto Rican (Boricua) ancestry presenting with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE-37) with prominent movement disorder.

Background:

EIEE-37 is caused by biallelic loss of function variants in the FRRS1L gene, which is critical for AMPA-receptor function, resulting in intractable epilepsy and dyskinesia.

Methods:

A retrospective, multicenter chart review of patients sharing the same homozygous FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) pathogenic variant identified by clinical genetic testing. Clinical information was collected regarding neurodevelopmental outcomes, neuroimaging, electrographic features and clinical response to antiseizure medications.

Results:

Fifteen patients from 12 different families of Puerto Rican ancestry were homozygous for the FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) pathogenic variant, with ages ranging from 1 to 25 years. The onset of seizures was from 6 to 24 months. All had hypotonia, severe global developmental delay, and most had hyperkinetic involuntary movements. Developmental regression during the first year of life was common (86%). Electroencephalogram showed hypsarrhythmia in 66% (10/15), with many older children evolving into Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Six patients demonstrated progressive volume loss and/or cerebellar atrophy on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Conclusions:

We describe the largest cohort to date of patients with epileptic encephalopathy. We estimate that 0.76% of unaffected individuals of Puerto Rican ancestry carry this pathogenic variant due to a founder effect. Children homozygous for the FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) Boricua variant exhibit a very homogenous phenotype of early developmental regression and epilepsy, starting with infantile spasms and evolving into Lennox-Gastaut syndrome with hyperkinetic movement disorder.

Keywords: FRRS1L protein, epilepsy, early infantile epileptic encephalopathy, dyskinesias, developmental disabilities

Genetic epileptic encephalopathies are a growing group of neurodevelopmental disorders where abnormal electrical activity and seizures are associated with impaired neurocognitive and behavioral development. Previous reports have identified biallelic pathogenic variants in the FRRS1L (Ferric Chelate Reductase 1-Like) gene (MIM 604574) as causative of EIEE37 (MIM 616981).1,2 The FRRS1L protein has been shown to have a key role regulating the ionotropic glutamate AMPA receptor function, localization and stability.3 The FRRS1L protein interacts with the GluA1 subunit of the AMPA receptor in mouse hippocampal neurons and its knockdown reduces AMPA receptor–mediated synaptic transmission.4 Additionally, in Frrs1l-null mice, reduced and immature AMPA receptor levels have been shown to alter glutamatergic signaling.5 Previously published pathogenic variants include a homozygous in-frame deletion in the FRRS1L c.737_739delGAG (p.Gly246del), initially described in a child of Puerto Rican ancestry. Here, we report the presence of a founder variant and the detailed neurologic phenotype of 15 patients homozygous for this Boricua (Puerto Rican) variant in 12 unrelated families.

Consistent with previous reports, our patients exhibit symptoms of epileptic encephalopathy with choreoathetoid movements.1,2 We also document developmental regression and cerebral atrophy that has not been consistently reported previously as part of the phenotype. Most patients had an electroclinical diagnosis of infantile spasms (West syndrome), with older children evolving to the electroclinical phenotype of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epileptic spasms were reported between 6 and 24 months of age in 4 patients with hypsarrhythmia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Synopsis of Children With the Homozygous Boricua FRRS1L Variant.

| Case no. | Age (y) | Sex (F/M) | Regression (Y/N) | Movement disorder | Seizure onset (mo) | Dysphagia | Respiratory | Seizure semiology | EEG | Brain MRI/CT | CMA results | Current AEDs | Past AEDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | F | Y | Choreiform | 25 | Gastrostomy tube | Aspiration pneumonia | Epileptic spasms and tonic seizure | Hypsarrhythmia, then slow spike and wave | Normal at onset, later atrophy | N/A | CBL, LTG LVT, CBDa | ACTH, ZNS, VGB, VPA, RUF, TPM, KD |

| 2 | 3 | F | Y | Choreiform | 19 | Gastrostomy tube | CPAP | Focal and generalized clonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Trace lactate MRS | N/A | TPM, VGB, CBDa | Pred, GBT, PHB |

| 3 | 2 | M | Y | Choreiform, dystonia | Gastrostomy tube | Recurrent aspiration | Focal, epileptic spasms | Hypsarrhythmia | Cerebellar atrophy, thin CC | N/A | LVT, TPM CBL | N/A | |

| 4 | 2 | M | Y | Choreiform | 3 | Pending evaluation | Room air | Epileptic spams, focal clonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Chronic bleed at R caudothalamic groove | N/A | LVT | VGB, ACTH, CNZ |

| 5 | 3 | M | Y | None | 22 | Gastrostomy tube | Room air | Focal and generalized clonic | Slow, disorganized background, continuous epileptiform discharges | Normal MRI brain at 10 months, Normal F/U MRI brain at 21 months | Normal | RUF, LVT, KD, CBDa | N/A |

| 6 | 4 | M | Y | Choreiform | 18 | Fed orally, modified texture | Room air | Generalized tonicclonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Normal MRI at 2yo, no F/U imaging | Normal | VPA | ACTH, VGB |

| 7 | 4 | F | Y | Choreiform | 24 | Gastrostomy tube | Chronic respiratory failure | Generalized tonicclonic, myoclonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Enlarged subarachnoid spaces at age 1 y, no F/U MRI | Duplication 7q36.2 | VPA, CBL, TPM | LAC |

| 8 | 16 | M | Y | Choreiform | 8 | Gastrostomy tube | Tracheostomy | Generalized tonicclonic | Hypsarrhythmia, then slow spike and wave | Normal at 3 mo, cerebellar atrophy at age 5 y | Normal | CBDa, CBL, LVT, PHT | LTG, PHT, LVT, CNZ, KD |

| 9 | 28 | M | Y | Choreiform | <12 | Gastrostomy tube | Tracheostomy | Generalized tonicclonic | Slow spike and wave | Cortical and cerebellar atrophy at age 8 y, worsen by age 12 y | Normal | CBDa | LTG, KD |

| 10 | 2 | F | Y | Choreiform | 13 | Gastrostomy tube | Nocturnal CPAP | Myoclonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Normal CT brain at 2yo, no F/U imaging | Not tested | CBDa, VPA, LVT, CBL | TPM |

| 11 | Deceased at 8 | F | Y | Choreiform | 12 | Gastrostomy tube | Tracheostomy | Myoclonic | Hypsarrhythmia | Normal at age 1-4 y, no F/U imaging | N/A | N/A | LVT, TPM, CBL |

| 12 | 4 | F | Y | Choreiform, myoclonus | 26 | Fed orally, modified texture | Normal PSG | Secondary generalized tonicclonic, generalized tonic | 2-3-Hz rhythmic delta with superimposed multifocal spike discharges | Normal, (MRS GABA/glu peak at 2.3 ppm and trace lactate) | N/A | LVT | None |

| 13 | 13 | M | Y | Choreiform | 24 | Gastrostomy tube | Difficulty clearing secretions, aspiration | Epileptic spasms | Hypsarrhythmia, then slow spike and wave | Normal MRI brain at 21 mo, no F/U imaging | Normal | TPM, LVT | N/A |

| 14 | 25 | F | N | None | 18 | Gastrostomy tube | Difficulty clearing secretions | Myoclonic | N/A | Brain atrophy | N/A | LVT, KD | LTG, VNS |

| 15 | 1 | M | N | None | 24 | Gastrostomy tube | N/A | Generalized tonicclonic myoclonus | Multifocal sharp waves | Normal MRI brain at 7 months, no F/U imaging | Not tested | TPM | N/A |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotrophic hormone; AED, antiepileptic drug; CBD, cannabidiol; CBL, clobazam; CC, corpus callosum; CMA, chromosomal microarray; CNZ, clonazepam; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalogram; F/U, follow-up; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GBT, gabapentin; glu, glutamate; KD, ketogenic diet; LAC, lacosamide; LTG, lamotrigine; LVT, levetiracetam; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; N, no; N/A, not available; PHB, phenobarbital; PHT, phenytoin; Pred, prednisone; ppm, parts per million; PSG, polysomnography; R, right; RUF, rufinamide; TPM, topiramate; VGB, vigabatrin; VNS, vagal nerve stimulator; VPA, valproate; Y, yes; ZNS, zonisamide.

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved cannabidiol.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of patients homozygous for the FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) pathogenic variant at 8 different academic institutions in the United States was performed. Clinical variables included age of onset, presence of developmental delay, age of epilepsy onset, physical examination findings, neuroimaging findings, genetic testing, ancestry information, and prior and current antiseizure drugs regimen. Institutional review board consent was obtained at Drexel University College of Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, or through a commercial laboratory (GeneDx). Sites reporting a single case were institutional review board exempt. Carrier rates and population allele frequencies were estimated using the gnomAD6 browser (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org), the Exome Variant Server7 (https://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), the 1000 Genomes Project,8 and the BioMe Biobank.9

Results

We describe the clinical presentation of 15 patients, 8 males and 7 females, who share the identical FRRS1L homozygous pathogenic p.Gly246del variant and Puerto Rican ancestry (Table 1). The patients were born at full term, and hypotonia was noticed within the first year of life, with severe motor and speech delay. Most patients also developed intractable epilepsy within the first 2 years of life, with electroencephalograms showing hypsarrhythmia in 66% (10/15) of cases. Dyskinetic movements, specifically the choreiform type, were reported by 2 years of age in 80% (12/15) of cases. Placement of a gastrostomy tube due to failure to thrive and recurrent aspiration due to neurologic dysphagia was common. Respiratory complications including chronic respiratory insufficiency were reported in 5 cases, all older than 5 years. Clinical findings on neurologic examination included nystagmus, muscle atrophy, hypotonia with variable appendicular hyperreflexia, and spasticity. None of the patients developed speech or ambulation. No clear hearing or ophthalmologic deficits were identified, but most patients had cortical visual impairment. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal for most of the cases, followed by cortical and cerebellar atrophy in those with available follow-up imaging. Six of 15 patients were prescribed cannabidiol for epilepsy management. Of these, 2 showed a decrease in seizure frequency with clobazam to 50% from the baseline and to 90% when Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved cannabidiol (Epidiolex, GW Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, UK) was added to clobazam, and the third patient improved in seizure frequency but had no sufficient data to quantify response, with the caveat that it was concurrently administered with clobazam. Therefore, it is also possible that cannabidiol was acting synergistically with clobazam by altering its hepatic metabolism.

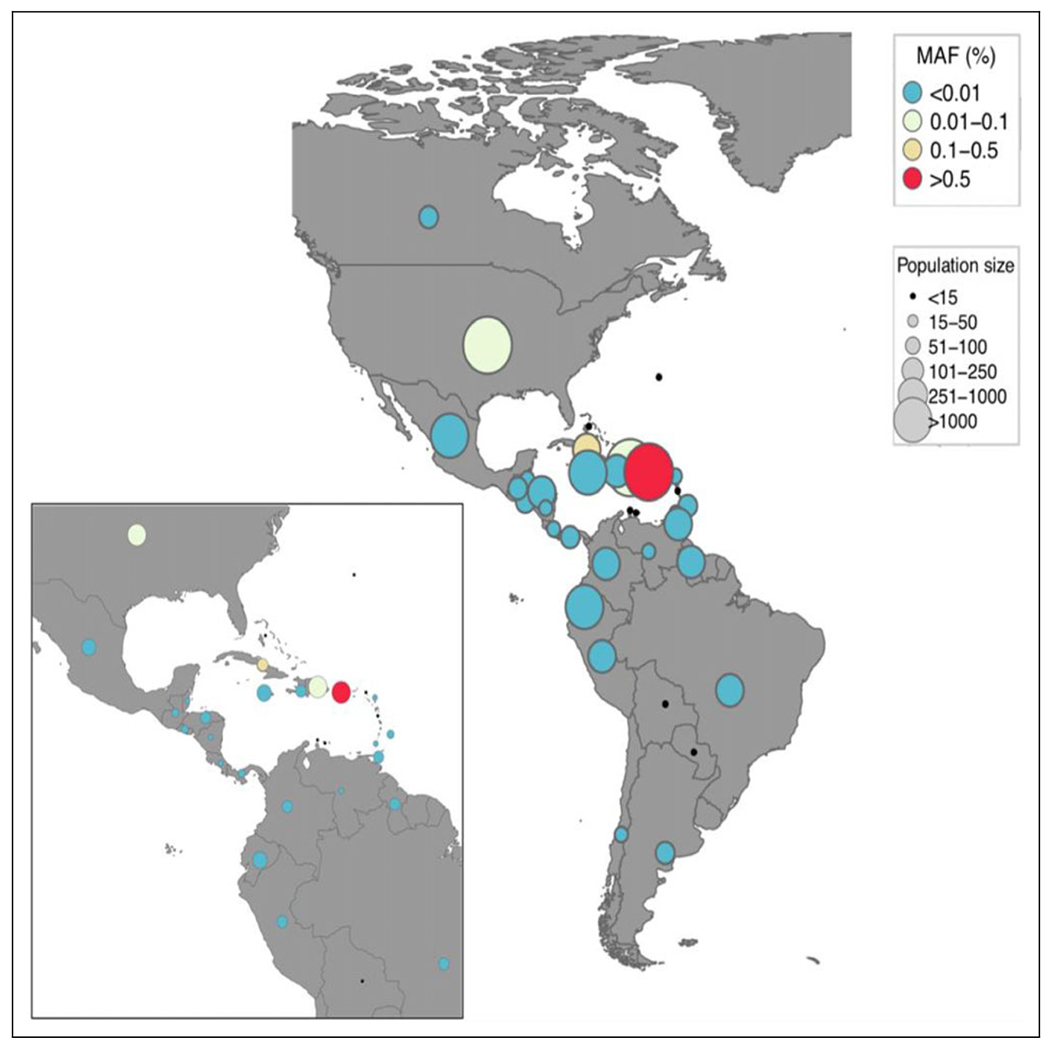

The p.Gly246del variant is present in 5 copies in 251 484 exomes in the gnomAD6 data set (95% confidence intervals 7×10−6 to 5×10−6 in the overall gnomAD population and 2 × 10−5 to 3 × 10−4 in the gnomAD “Latino” population). It is not present in 6503 European American and African American exome sequences from NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project,7 nor in 2504 whole genome sequences from 25 worldwide populations, including 104 from Puerto Rico, from the 1000 Genomes Project.8 The BioMe Biobank9 contains 90 carriers (out of 30 813 unrelated participants [less than second-degree relatives]). All except 1 reported place of birth as Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Cuba, or continental United States and have genetic ancestry consistent with Puerto Rican ancestry. This one carrier with inconsistent ancestry has East Asian genetic ancestry. Carrier rate is much higher in BioMe compared with gnomAD, suggesting that the variant is highly specific to Puerto Rican and related populations that may not be represented in gnomAD. Restricting analysis to 2251 BioMe participants born in Puerto Rico, we estimate an allele frequency of 34/4502, that is, 0.76% (95% confidence interval 0.53% to 1.06%), supporting the hypothesis that this variant is a founder variant largely restricted to the Puerto Rican population (Figure 1). One caveat is that the BioMe cohort may not be fully representative of Puerto Rican genetic diversity, although it is not deliberately enriched for EIEE cases or carriers. Finally, of 75 carriers with local ancestry information at the locus, 74/75 have European ancestry on at least 1 haplotype flanking the deletion (hg19 chr9:108147768-110131397), across chromosome 9; noncarriers have on average 63% European ancestry, implying that the variant is carried on a haplotype of European origin (P = .0002 that the European ancestry of carriers at this locus is the same as the chromosome-wide ancestry of noncarriers). No homozygotes were found in the gnomAD database.

Figure 1.

Allele frequency of FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) variant in BioMe participants by country of birth, restricting to the Americas. (MAF, minor allele frequency).

Discussion

Loss of function variants in the FRRS1L gene have been recently reported as causative of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy with hyperkinetic movement disorder.1,2 Several lines of evidence in vitro and in vivo using mouse models converge on a critical role of the FRRS1L protein in modulating AMPA receptor function, localization, and stability in neurons.3–5

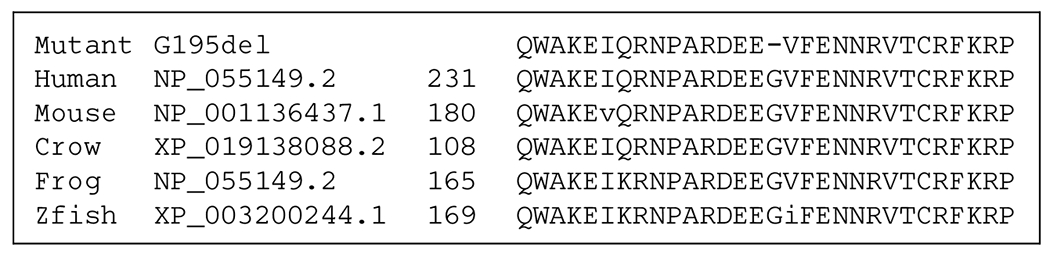

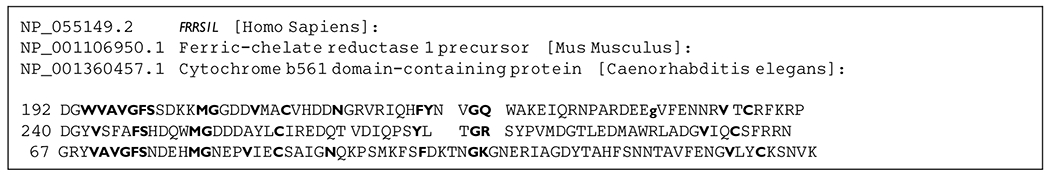

Knockdown expression of the FRRS1L gene with siRNA in human neuronal cells (SH-SY5Y) attenuated calcium influx and diminished AMPA-induced inward currents in patchclamp experiments.1 Nearly all FRRS1L variants in EIEE-37 patients are biallelic loss of function variants, which in combination with the in vitro knockdown experiments and recent mouse knockout data5 suggest the loss of function as the disease mechanism. Not including the p.Gly246del variant, of the 13 FRRS1L pathogenic entries in ClinVar, all but one are null variants.10 Although the functional effects of the p.Gly246del variant has not been established in the literature, it does alter a highly conserved residue of this protein, located in the predicted transmembrane and extracellular dopamine betamonooxygenase N-terminal (DOMON) domain involved in protein-sugar interactions (Figure 2). In a comparison between distantly related proteins with DOMON domain, we cannot define a conserved role for the deleted glycine-246 residues (Figure 3). It is not a residue conserved between these DOMON domains. However, this may mean that this glycine is related to the specificity of the binding site of the FRRS1L DOMON domain. The function of the DOMOM domain in this protein is unclear, and we hypothesize that a well-defined function may be crucial given that this variant leads to a severe phenotype.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the mutant G246del FRRS1L with other homologues from other species demonstrates the glycine residue is conserved unchanged from man to fish.

Figure 3.

Aligned DOMON domain of human FRRSIL, mouse ferric-chelatase, and nematode Cytb651 show that Gly246 in FRRS1L (small bolded letter g) is not conserved between these distantly related proteins. Conserved and semiconserved amino acids are bolded.

The phenotype presented by children harboring the Boricua FRRS1L p.Gly246del variant in our series is similar to that previously described by Madeo et al,1 which includes the first patient in the literature with this specific variant. The same proband is reported here with updated information as patient 1, now 14 years old. In our cohort, developmental regression, which had been reported inconsistently, is typical for FRRS1L epileptic encephalopathy. Patients clinically deteriorated during the first year of life, with 86% (13/15) reporting regression, often coinciding with onset of epilepsy. In addition, our cohort presents evidence of progressive neuroimaging changes (progressive cortical and/or cerebellar atrophy) in patients who had serial neuroimaging studies available. Salient features that help distinguish FRRS1L early epileptic encephalopathy from others are the onset of seizures between 6 and 24 months of age and prominent dyskinetic movements in early childhood.

Founder variant effects are common in island populations. In Puerto Rico, more than a dozen autosomal recessive conditions due to founder variants have been described, including Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome types 1 and 3 (MIM 203300, MIM606118) and primary ciliary dyskinesia (MIM 612649).11 Among pediatric neurologic disorders, TBCK encephaloneuronopathy (MIM 616900) and limb-girdle muscular dystrophy due to gamma sarcoglycan (SGCG) pathogenic variants have been reported to be associated with founder Boricua variants.12,13 Analysis of exome sequence cohorts suggest that FRRS1L (p.Gly246del) variant is largely restricted to the Puerto Rican population, whose genetic ancestry is a mixture of European, American, and African ancestry. Like many populations in the Americas, the Puerto Rican population had an extreme founding bottleneck. In fact, this bottleneck is one of the most extreme observed in any present-day American population, with an effective population size of around 100 for the American component and 1000 for the European and African components.14 The FRRS1L pathogenic variant described in this article appears to lie on the background of a European ancestry haplotype. The small size of bottleneck suggests finding many founder variants on all ancestry backgrounds in the Puerto Rican population.

In conclusion, we report the largest cohort of patients affected by FRRS1L epileptic encephalopathy, and homozygous for a Boricua variant. We provide detailed phenotypic characterization for counseling and prognosis discussion with families affected by this devastating disorder. Although access to genetic testing remains a challenge in Puerto Rico, we speculate that the FRRS1L variant may be the most common cause of EIEE among children of Puerto Rican ancestry, given the carrier frequency of around 0.76%. With the growing number of genetic disorders linked to founder effects in Puerto Rican individuals, genetic screening of asymptomatic carriers may be considered in the future for reproductive planning purposes, similar to current clinical practice in other populations with high burdens of founder disease variants. Although preliminary, there is a suggestion of therapeutic response to cannabidiol combined with clobazam for epilepsy management in our cohort, which should be examined in future studies.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: XOG is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Faculty Development Award.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

Written informed consent was obtained in research protocols approved by the respective institutional review boards (IRB) at Drexel University College of Medicine (#1904007105), Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (#15-012226). Sites reporting a single case were institutional review board exempt, per the regulations of their local institutions.

References

- 1.Madeo M, Stewart M, Sun Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FRRS1 L lead to an epileptic-dyskinetic encephalopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(6):1249–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaheen R, Al Tala S, Ewida N, Abouelhoda M, Alkuraya FS. Epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during sleep maps to a homozygous truncating mutation in AMPA receptor component FRRS1 L. Clin Genet. 2016;90(3):282–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brechet A, Buchert R, Schwenk J, et al. AMPA-receptor specific biogenesis complexes control synaptic transmission and intellectual ability. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han W, Wang H, Li J, Zhang S, Lu W. Ferric Chelate Reductase 1 Like protein (FRRS1 L) associates with dynein vesicles and regulates glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart M, Lau P, Banks G, et al. Loss of Frrs1 l disrupts synaptic AMPA receptor function, and results in neurodevelopmental, motor, cognitive and electrographical abnormalities. Dis Model Mech. 2019;12(2):dmm036806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes. 10.1101/531210v3, n.d. [DOI]

- 7.NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Exome Variant Server. http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/. Accessed May 17, 2019.

- 8.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belbin GM, Odgis J, Sorokin EP, et al. Genetic identification of a common collagen disease in Puerto Ricans via identity-by-descent mapping in a health system. Elife. 2017;6:e25060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ClinVar. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar, n.d.

- 11.Daniels ML, Leigh MW, Davis SD, et al. Founder mutation in RSPH4A identified in patients of Hispanic descent with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Hum Mutat. 2013;34(10):1352–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Zaidy SA, Malik V, Kneile K, et al. A slowly progressive form of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2C associated with founder mutation in the SGCG gene in Puerto Rican Hispanics. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2015;3(2):92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz-González XR, Tintos-Hernández JA, Keller K, et al. Homozygous Boricua TBCK mutation causes neurodegeneration and aberrant autophagy. Ann Neurol. 2017;83:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning SR, Browning BL, Daviglus ML, et al. Ancestry-specific recent effective population size in the Americas. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(5):e1007385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]