Abstract

The number of gender diverse and transgender youth presenting for treatment are increasing. This is a vulnerable population with unique medical needs; it is essential that all pediatricians attain an adequate level of knowledge and comfort caring for these youth so that their health outcomes may be improved. There are several organizations which provide clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of transgender youth including the WPATH and the Endocrine Society and they recommend that certain eligibility criteria should be met prior to initiation of gender affirming hormones. Medical intervention for transgender youth can be broken down into stages based on pubertal development: pre-pubertal, pubertal and post-pubertal. Pre-pubertally no medical intervention is recommended. Once puberty has commenced, youth are eligible for puberty blockers; and post-pubertally, youth are eligible for feminizing and masculinizing hormone regimens. Treatment with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists are used to block puberty. Their function is many-fold: to pause puberty so that the youth may explore their gender identity, to delay the development of (irreversible) secondary sex characteristics, and to obviate the need for future gender affirmation surgeries. Masculinizing hormone regimens consists of testosterone and feminizing hormone regimens consist of both estradiol as well as spironolactone. In short term studies gender affirming hormone treatment with both estradiol and testosterone has been found to be safe and improve mental health and quality of life outcomes; additional long term studies are needed to further elucidate the implications of gender affirming hormones on physical and mental health in transgender patients. There are a variety of surgeries that transgender individuals may desire in order to affirm their gender identity; it is important for providers to understand that desire for medical interventions is variable among persons and that a discussion about individual desires for surgical options is recommended.

Introduction

As the number of youths identifying as gender diverse and the number of youths seeking care for gender dysphoria are increasing, it is essential that all pediatricians attain an adequate level of comfort and knowledge so that they are equipped to care for this vulnerable populations’ medical and mental health needs.

It is essential that all pediatricians attain an adequate level of comfort and knowledge so that they are equipped to care for this vulnerable populations’ medical and mental health needs.

Primary care pediatricians are in a powerful position to affect change: at the front lines of care, they are often the first point of contact for patients’ emerging questions of gender identity. Pediatricians may choose to initiate gender affirming medical care (GAMC) or refer to an adolescent medicine specialist or endocrinologist to provide this care; either way, timely initiation of medical care may be life-saving. A recent study demonstrated that more than half of pediatric providers surveyed were not aware of guidelines related to puberty blocking treatments,1 which may translate to TGNC youth not receiving time sensitive medical interventions. Timely administration of gender affirming medical care correlates with improved mental health outcomes and,2,3 conversely, a delay in medical care may lead to worse mental health outcomes.4

The following sections will be devoted to specifically discussing and outlining the practices for providing GAMC.

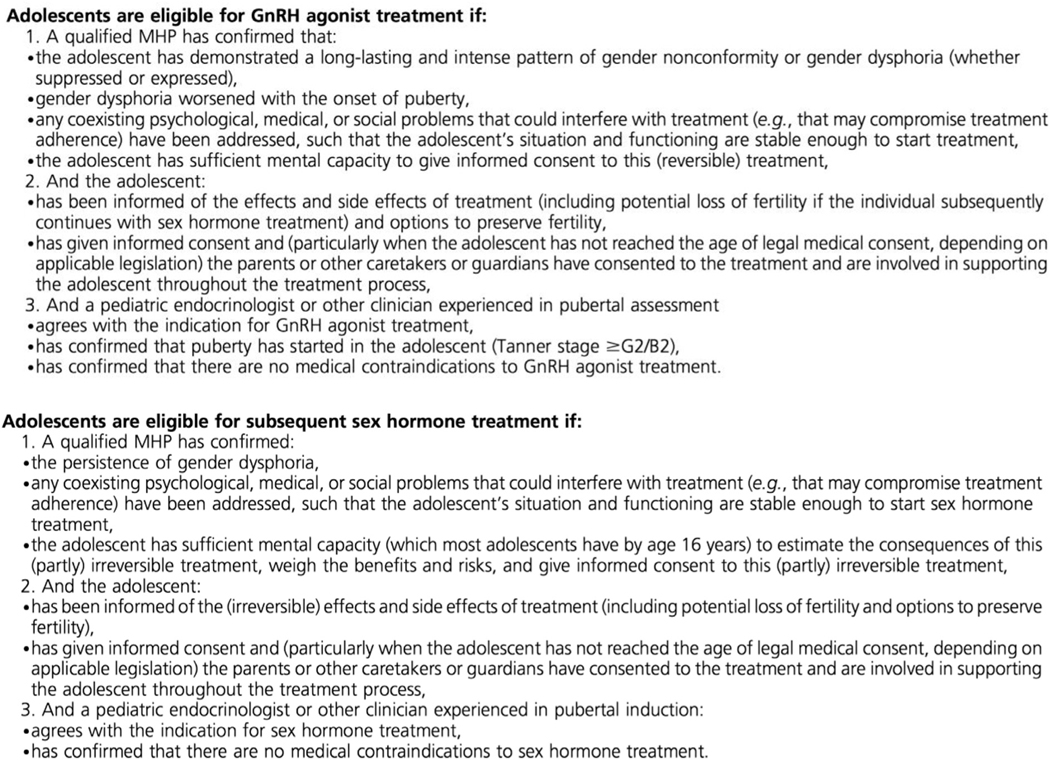

There are several organizations which provide clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of transgender individuals Including the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH), Standards of Care (SOC), Seventh Version (2012), the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines, Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons5 and the UCSF Center for Transgender Excellence, Primary Care Protocol for Transgender Patient Care (2011) all of which contain sections devoted to the care of the pediatric and adolescent populations. The Endocrine Society and the WPATH put forth eligibility criteria for hormonal therapy for adolescents; these eligibility criteria include that a mental health professional versed in gender variance has diagnosed the patient with gender dysphoria, the gender dysphoria worsened with the onset of puberty, coexisting medical, psychological or social problems that could interfere with treatment should be addressed, and the adolescent is able to give informed consent; and, if the adolescent has not yet reached the legal age of medical consent, then the parents must consent. Additionally, in the discussion regarding the risks and side effects of treatment, the provider should inform the patient of the potential compromise of fertility as well as the options available to preserve fertility prior to initiation of gender affirming hormones (GAH) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Criteria for gender affirming hormone treatment for adolescents

From Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869–3903. Reproduced by permission.

There are several organizations which provide clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of transgender individuals

It should be noted that there are several limitations to the current guidelines. While the guidelines are based on the best available evidence, because of the paucity of long-term outcome data in transgender youth, they significantly rely on expert professional consensus. The different guidelines also vary in content, are mutable, and those with age recommendations may be used to deny treatments or coverage for youth.

Timing of gender affirming medical care

Medical intervention for transgender youth can be divided into stages based on pubertal development (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Timeline of masculinizing effects in transgender males.

| Pre-pubertal (<8 yrs old) |

Pubertal (8–14 yrs old) |

Post-Pubertal (>14 yrs old) |

|---|---|---|

| - NO medical intervention - Acceptance and affirmation - Social transition - Referral to mental health provider |

- Puberty blockers | - Testosterone - Estrogen - Gender affirming surgeries |

GAMC for pre-pubertal transgender youth

Prior to puberty (pre-pubertal) no medical intervention is recommended. In fact, the Endocrine Society, in the most recent iteration of their guidelines, explicitly recommends against the use of puberty blocking prior to initiation of puberty. What is indicated during this pre-pubertal stage is acceptance and affirmation of the patient’s gender identity. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently released a policy statement on the care of gender diverse and transgender youth and recommends a gender-affirmative care model in which pediatric providers “offer developmentally appropriate care that is oriented towards understanding and appreciating the youth’s gender experience.”6 During this time the patient may be evaluated by a mental health provider with expertise in gender identity, diagnosed with gender dysphoria, and sometimes this provider may help the patient and family navigate a social transition (for further discussion regarding social transition please refer to Article 1, section title of article 1).

GAMC for pubertal transgender youth

Youth are eligible for pubertal suppression once puberty has commenced (tanner stage 2). For birth assigned females the first manifestation of puberty is breast development (thelarche) which typically occurs in the age range of 8–13 years. For birth assigned males, the first sign of puberty is testicular enlargement (testicular volume ≥ 4 ml) which typically occurs in the age range of 9–14 years. According to the ES and WPATH SOC guidelines for eligibility, the youth should be diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a qualified mental health provider and the gender dysphoria should have worsened with the onset of puberty (see Fig. 1).5,7

Pubertal blockers function to effectively pause puberty in order to delay any further development of (potentially irreversible) secondary sex characteristics

Pubertal blockers function to effectively pause puberty in order to delay any further development of (potentially irreversible) secondary sex characteristics such as breast growth, voice deepening, facial structure changes, Adams’ apple development and facial hair. Pubertal suppression, therefore, may obviate the need for future surgical interventions and allow youth the option to undergo the puberty that aligns with their gender identity through the use of gender affirming hormones. Putting puberty on hold allows youth the time to explore their gender identity with the help of their support system (which may include a mental health provider) and without the anticipatory anxiety of impending pubertal changes. This form of intervention is considered reversible but there are no long term studies to determine if there are associated risks: if the blocker is discontinued then return to natal puberty will occur, typically within six months after cessation of the blocker. Alternatively, the adolescent may choose to continue pubertal suppression and start gender affirming hormones which may eliminate the need to suppress endogenous production of natal sex hormone. Currently there is no consensus on the length of time GnRH agonist should continue after youth begin gender affirming hormones, however if gonadectomy is performed then it may be discontinued at this time.

While pubertal suppression should typically be started in early puberty (Tanner 2/3), patients who present for care later in adolescent development may also derive benefit from use in later pubertal stages (Tanner 4/5). Use of blockers at later stages will prevent the development of further pubertal stages such as continued breast development or voice deepening. Additionally, the blockers can be beneficial to induce amenorrhea in a birth assigned female who experiences significant dysphoria with menses.

GAMC for post-pubertal transgender youth

As mentioned above, adolescents in later stages of puberty (Tanner 4/5) may also benefit from pubertal suppression. The blockers may be started at this stage or continued (if started in early puberty) with the addition of gender affirming hormones (estrogen, testosterone) to suppress endogenous production of sex steroids which may theoretically allow for the use of lower doses of cross sex hormones and therefore lessen any potential toxicities associated with treatment. Older adolescents may also present to care later and be eligible for gender affirming hormones (GAH) if certain criteria are met (See Fig. 1). The ES and WPATH SOC recommend evaluation by a qualified mental health provider prior to starting GAH. While historically the age of 16 was the age cut-off to start GAH, the recent ES Guidelines support a more flexible age of initiation (the timing of starting GAH will be discussed in the upcoming section titled “Timing of Gender Affirming Hormones”). Gender affirming surgeries are also an option for transgender youth post-puberty. The ES recommends delaying surgeries in adolescents until the age of 18, however, standard practices vary and some surgeries are performed prior to the age of 18.5,8 In the most recent iteration of the ES Guidelines, it is recommended that the timing of chest masculinization surgery in transgender males be determined based upon the physical and mental health status of the patient and there is no specific age requirement5 Gender affirming surgeries will be discussed in more detail in the upcoming section titled “Gender Affirming Surgery”.

Assessment visits

The initial medical assessment visits of the gender diverse patient may require several clinic sessions as there are several goals. The first is to learn about the patient’s gender story including their realization and understanding of their gender identity. It is important to understand the patient’s goals for medical intervention (e.g. menstrual suppression, pubertal suppression or gender affirming hormones) and what they hope to achieve with the use of gender affirming hormones. The provider should take a pubertal history including age of menarche and menstrual history along with pubertal staging with physical exam to guide medical decision making. A discussion regarding the patient’s desire for genetic offspring and available options for fertility preservation, both with the parent/guardian in the room and confidentially with the adolescent (discussed further in Article 3 titled “Fertility Preservation”).

A thorough medical history should be taken in an effort to assess for the presence of any absolute or relative contraindications to hormone therapy or conditions that may impact or complicate the decision to start hormonal therapy. The provider may consider a risk/benefit analysis discussion with the patient and/or guardians about the medical interventions which may potentiate the patients’ baseline risk of certain side effects. A thorough family history should be taken with attention to history of venous thromboembolism, cardiovascular disease and diabetes which may serve to guide a discussion regarding the risks of hormone use. Due to the increased risk of depression and anxiety in these youth (and especially if the young person has not yet engaged in mental health services) typically a risk assessment for suicide should be conducted to ensure the patients’ safety.9 Similar to any other adolescent encounter, a social history including a sexual and substance use history should be taken with special attention to tobacco use given the associated increased venous thromboembolism risk with the use of gender affirming hormones (to be discussed further in Article 3, section titled “Prevention and Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Infections and HIV in Transgender and Gender-Expansive Youth”).

It is important to stage puberty however, the chest and genitalia exams may cause the significant patient distress due to dysphoria, therefore it may be helpful to establish rapport with the patient prior to this part of the exam (refer to Article 1 title of article 1 for further discussion).

Lastly, a significant amount of time is spent discussing the known risks/benefits and safety profile of the hormones with the patient and parents/guardians (if the patient is under the age of 18). Several clinics caring for gender diverse youth utilize written consent forms outlining this information.

Informed consent process

According to the ES and WPATH SOC, adolescents should be able to provide informed consent and the parents or guardians should consent if the patient has not reached the age of legal medical consent (in which case the youth then provides assent for treatment).5 The age at which adolescents are able to give medical consent for treatment varies in different parts of the world. While 18 years of age is the age at which an individual is no longer a minor in the United States and may provide consent for medical treatment, there are exceptions: minors are able to consent for sexual and reproductive care, and, in some states, they can also consent for mental health and substance abuse care.10

The patient should also have sufficient mental capacity to provide informed consent. While the age for sufficient mental capacity can very much vary based on the developmental stage of the patient, the Endocrine Society states that most adolescents possess the ability to understand the partially irreversible consequences of gender affirming hormones by age 16.5 The updated ES guidelines state that it may be appropriate to start gender affirming hormones prior to the age of 16 and this determination is based on developmental stage of patient and not solely based on the chronological age of patient. There are several other factors which support the use of GAH prior to the age of 16 including peer concordance of puberty and benefits of bone health (both of which will be discussed in the upcoming section titled “Timing of gender affirming hormones”).

The uncertainty regarding age of appropriate consent is further complicated by the fact that youth are seeking GAMC at younger and younger ages. Young patients, as young as 8 years old, may present for pubertal suppression with their parents. It can be challenging to have a developmentally appropriate discussion with the youth about the risks and benefits regarding the use of blockers as well as a discussion about fertility preservation desires and options in a patient this young.

There is no standard practice for requirement on one parent vs. dual parental consent for gender affirming hormones. Anecdotally, many institutions require dual parental consent which poses impediments to intervention if one parent objects to treatment or one parent is not actively involved in the patient’s life. There is a need for further consensus on this topic given the lack of legal precedent and ethical implications.

Pubertal suppression

Mechanism of action

As discussed above (in section titled “GAMC for Pubertal Transgender Youth”), once puberty has commenced, youth are eligible for pubertal suppression. At the onset of puberty GnRH is secreted by neuroendocrine cells in the hypothalamus in a pulsatile fashion. GnRH then binds to receptors on the anterior pituitary gland, stimulating the release of LH (luteinizing hormone) and FSH (follicle stimulating hormone). LH and FSH then stimulate the release of sex steroids from the gonads (testosterone in male individuals and estrogen and progesterone in female individuals) that leads to the development of secondary sex characteristics. GnRH agonists (or puberty blockers) are synthetic peptides which work to continually stimulate gonadotropin release which effectively desensitizes the gonadotropin receptors and ultimately causes complete, reversible suppression of the pituitary-gonadal axis. Suppression of this hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis leads to a cessation of the progression of secondary sexual development for as long as the patient is taking the GnRH agonist. Puberty blockers are thought to be a reversible intervention (with the caveat that there are no long-term studies in transgender youth, only in youth with precocious puberty): if discontinued there is a reactivation of the axis and progression of endogenous puberty.11

Formulations/Dosing of pubertal suppression medications

While other medication options exist to achieve pubertal suppression, such as progestins, GnRH agonists are most commonly used given their superior efficacy, albeit higher cost. Histrelin and leuprolide are the two most commonly used formulations. There is also a newer formulation, called triptorelin, however, it is not used as often as it is considered a chemotherapeutic agent and requires mixing under a hood. Leuprolide is an injectable GnRH agonist which is available in different dosing frequencies, from daily to every 3–4 months. Histrelin is an implantable version of GnRH agonist, surgically inserted subcutaneously in the upper inner arm in an outpatient or surgical suite setting. While this formulation indicates that it is effective for one year, it typically will last longer than one year and can be replaced when it is no longer functioning. Both leuprolide and histrelin function to suppress the HPG axis. These medications are not FDA approved for the use of pubertal suppression in transgender youth. Both leuprolide and Supprelin (pediatric brand name of histrelin) have indications for use in the pediatric population, however an additional adult formulation, Vantas, can be used and is often cheaper.

Costs of pubertal suppression medications

The costs of GnRH agonists, unlike gender affirming hormones, can be prohibitively expensive for patients: estimated out of pocket cost for the 3 month depot pediatric leuprolide is roughly $9500 and for the histrelin is $39,000. There is a recent trend for increasing insurance coverage, with a recent study demonstrating insurance company coverage of blockers 72% of the time in cases surveyed.12

Monitoring while on pubertal suppression

Patients should be monitored both at baseline and with regular frequency clinically, biochemically and with the use of DXA scans to assess bone density. According to the Endocrine Society patients should be seen every 3–6 months for measurement of height, weight, blood pressure and tanner stages, and every 6–12 months for laboratory monitoring including testosterone levels for transgender males and estradiol levels for transgender females. At baseline and annually, a bone age and DXA should be performed to assess for bone density given that pubertal suppression can compromise bone density accrual, although in clinical practice, this practice varies. This topic will be discussed in more detail in the upcoming section titled “Effect on Bone Mineral Density”.

Potential benefits, risks, and side effects of puberty suppression

While these medications have been used for over 30 years to suspend puberty in youth with central precocious puberty, and therefore the side effect and efficacy profile is known in this cohort, there is a dearth of long-term data about their use in transgender youth. Specific areas of uncertainty will be covered in the upcoming sections.

Reported side effects of puberty suppression include hot flashes (particularly if used in older adolescents), fatigue, alterations in mood, leg pain and sterile abscesses (at the site of leuprolide injections). Additionally, following the first month of GnRH agonist therapy there is a surge of gonadal hormones which can cause a menstrual bleed.13

Psychosocial effects

The available scientific evidence regarding the effect of pubertal suppression on psychosocial functioning is limited and mainly was performed by researchers in the Netherlands. GnRH agonist treatment was associated with marked improvements in many psychological domains, including global functioning, depression and overall behavioral and/or emotional problems.4,14,15 Puberty blockers, however, are not associated with a decrease in gender dysphoria.4,15 This may be, in part, due to the fact that puberty blockers do not act to ameliorate the discrepancy between physical body and gender identity.

Effects on bone mineral density

The period of adolescence is a critical window of time during which there is peak bone density accrual due to the increase in sex steroids (estrogen and testos-terone).16 The absence of sex steroids during a portion of this time frame therefore, may lead to a future risk of osteoporosis. While these medications have been used for many years in the treatment of precocious puberty, there is a paucity of data examining the long-term effects on bone health in transgender youth and there are limitations in extrapolating outcomes to transgender youth as they are a unique patient population. When GnRH agonists are used in patients with central precocious puberty, data demonstrates conflicting results about its effects on BMD, with treatment showing a reduction in BMD in some,17,18 but not others.19 Studies demonstrate normal bone mineral density after discontinuation of treatment.18,20,21

Based on scientific evidence currently available examining the use of GnRH agonists in transgender adolescents, it is unclear whether or not using puberty blockers in adolescence will increase the risk for future fractures in transgender adults. The data available for GnRH agonist use in transfemales demonstrates that lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) z scores decreased after the use of GnRH agonist.22,23 In transmale adolescents there was an even greater decrease in BMD compared with transfemales.22–24 In these same studies, however, the addition of estrogen or testosterone after use of GnRH agonist was associated with a significant increase in z scores for both transmales and transfemales.22,23 Specifically, estrogen was associated with significant increases in the lumbar spine,22,23 but not the hip in transfemales23 and testosterone was associated with significant increase in the lumbar spine and hip in transmales.22,23 While this data demonstrates that there is improvement in BMD after the addition of GAH, it is notable that for those transfemales who received estrogen, their BMD was still lower than age-matched peers two years after estrogen treatment, which suggests only partial compensation.23

Given the small number of studies on the effect of pubertal suppression on transgender adolescents, the Endocrine Society recommends both baseline and regular BMD monitoring with the use of puberty blockers.5 Additionally, it is important to counsel patients to optimize their bone health by maintaining adequate calcium and vitamin D intake as well as engaging in weight bearing exercise as is recommended for all adolescents.

Effects on cognition

Analogous to bone density accrual during adolescence, there is significant brain development during the window of adolescence and the effects of GnRH agonist treatment on the developing adolescent brain are currently unknown. Animal data suggest that there may be some effect of GnRH agonists on cognitive function.25 A recent study, however, which examined the effect of pubertal suppression on executive functioning (specifically cognitive planning) through the use of functional MRI found no effect on this higher order cognitive processing.26

Effects on body composition and height

Often parents/guardians and patients will have concerns and questions about the effect of pubertal suppression on final adult height. Only two studies thus far have examined the effect of GnRH agonist use on growth and height, however, these studies followed patients only in the short-term and therefore it is unclear what the effect of using pubertal suppression is on final adult height of patients. These studies showed that growth velocity decreased in adolescents on GnRH agonists compared with their pubertal-matched peers, particularly in younger patients.22,27

In terms of effect on body composition, studies show that after one year of GnRH agonist therapy, there is a significant increase in body fat percentage and BMI and a decrease in lean body mass percentage.22,24,27

Timing of gender affirming hormones

As discussed above (in section titled “GAMC for Pubertal Transgender Youth”) gender affirming hormones may be added to puberty blockers or started alone, particularly for older adolescents. Historically, GAH were started at the age of 16. There are several factors, however, that support starting GAH at an age younger than 16 and the Endocrine Society, in the most recent iteration of their guidelines, propose a more flexible age of initiation. Factors that support consideration of hormone initiation prior to age 16 include: 1. if there is a large gap of time between when a patient starts pubertal suppression and when they start GAH this could lead to sub-optimal accrual of bone mineral density and lead to a higher risk of osteoporosis in the future 2. the potential detrimental effect on mood including that lack of peer concordance with puberty could amplify the emotional and social challenges that are experienced with gender dysphoria. The Endocrine Society recommends an expert multidisciplinary approach to this decision including an assessment of medical decision-making capacity, as well as assessments of bone health the effect of delayed puberty on mental health, while also recognizing that there is a dearth of published studies of GAH used before the age of 13.5–14 years.

Masculinizing hormone regimens

Many adolescents who identify as male may request testosterone therapy. The purpose of using exogenous testosterone in transgender males is twofold: to both decrease the effects of estrogens and to promote male secondary sex characteristics such as deepening of the voice, development of facial hair, and increased muscle mass. Discussion of when to start testosterone usually involves discussions between the patient, their guardian (s), mental health providers, and treating provider and The Endocrine Society and WPATH propose eligibility criteria for starting gender affirming hormone treatment (see Fig. 1). Typically, testosterone is administered starting at the age of 16 years, though as indicated above, if a young person has been stable in their gender identity, has appropriate supports in place and is able to provide informed consent with parental assent, the Endocrine Society suggests that earlier initiation with testosterone is acceptable and may alleviate mood symptoms due to gender dysphoria (see section: Timing of Gender Affirming Hormones).

Testosterone: Mechanism of action

Testosterone has both anabolic and virilizing effects. Anabolic effects include increasing muscle mass and increasing bone mineral density, whereas virilizing effects include deepening of the voice, growth of the genitalia, and hair growth on the face, chest, and back.

In natal males, testosterone is secreted mostly by the testes under the influence of pituitary hormones-follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) and leutinizing hormone (LH). After the age of 6 months and prior to puberty, testosterone levels are low (0.3 ng/dL) in the plasma; with the onset of puberty and pulsatile release of gonadotropin releasing hormone and LH, testosterone levels begin to increase. The diurnal variation in testosterone continues to be present and the plasma concentration in an adult cis-male can also be varied.28

Formulations

Testosterone comes in several forms, injectable (both intramuscular and subcutaneous), patches, and gels, with injectable being the most common delivery route. Testosterone cypionate and testosterone enanthate are injectable formulations commonly used in the United States.

The injectable formulations are FDA-approved for use via the intramuscular route, however, multiple studies have shown that the subcutaneous route for both testosterone enanthate and testosterone cypionate yield similar drug levels, have less associated pain, and are not associated with additional comorbidities and therefore the subcutaneous route is often a preferred method of delivery.29,30

Other less commonly used forms include buccal and nasal formulations as well as subdermal implants.31 Buccal and nasal preparations require multiple time/day dosing to achieve male range testosterone levels as they are typically used to mimic the circadian rhythm of peaks and troughs in cisgender males. They are infrequently used because they are associated with the adverse event of hepatic injury.32

Subdermal implants are available in the form of multiple pellets which are placed in the arm and are to be removed and replaced every three months. This method of delivery has not yet gained popularity in the adolescent and young adult age groups.

Gels and patches are widely available and are replaced daily and may be considered in persons in whom injections are undesired (e.g. in a patient with needle phobia). Sites for application include the back, abdomen, upper arm, and thighs. Side effects of this method of delivery include local contact dermatitis which can be severe and limit its use. Additionally, gels can be transferred to others via skin-to-skin contact.

Dosing

Most of the data for testosterone dosing is derived from treating cisgender males with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.33 In pre-pubertal cisgender males, less frequent and low dose testosterone is initiated to mimic male puberty and to give age-appropriate bone health without premature closure of epiphyses. In adult cis-males with hypogonadism, higher doses of testosterone are used to achieve adult appropriate steady levels of testosterone.34 It is important to note that with injectable forms of testosterone, the diurnal variation in levels is not achieved and this is currently of unknown consequence.

Typically, the goal is to titrate testosterone to that of cisgender male testosterone levels and to consider the age of the patient, presence or absence of pubertal blockade, and height of the patient. It is typical to start a low dose of any formulation, and then to titrate slowly based on testosterone levels and patient desires for gender expression.

The Endocrine Society outlines the dose escalation recommended for starting testosterone therapy in both persons who are on pubertal suppression as well as adolescents who have already progressed through puberty and are not on suppression with most persons requiring between 50 mg to 75 mg injectable testosterone weekly.5

Monitoring

Initiating testosterone therapy for adolescent transgender males requires initial assessment of sexual maturity rating, also known as Tanner staging and evaluation of genitalia for any anomalies. Baseline lab studies are also delineated by the Endocrine Society.

Given the potential for polycythemia which will be discussed below, experts recommend baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit as well as monitoring every three months while the dose is adjusted.

Cis gender males have testosterone levels 350–1150 ng/dL (which may vary depending on the laboratory used) with averages near 600 ng/dL for adult males. In line with the treatment of male hypogonadism, recommendations suggest aiming for goal testosterone levels of 400–700 ng/dL for adult males.5,35 Vitamin D levels, DEXA scans, and bone age is also recommended, however, there is poor evidence for this recommendation.5

Eligibility for initiation of masculinizing therapy

Please see Fig. 1 above. Additionally, persons should have baseline labs evaluated and informed consent procedures should be applied.

Screening for conditions prior to testosterone therapy

There are no common contraindications to testosterone therapy, but blood count monitoring for baseline polycythemia and hyperlipidemia is recommended.

Effects of testosterone therapy

Timeline of changes

The effects of testosterone can vary from person to person. Changes experienced by the patient from testosterone are dependent upon many variables including the dosing used and testosterone levels achieved (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Masculinizing effects in transgender males.

| Effect | Onset | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Skin oiliness/acne | 1–6 mo | 1–2 y |

| Facial/body hair growth | 6–12 mo | 4–5 y |

| Scalp hair loss | 6–12 mo | _a |

| Increased muscle mass/strength | 6–12 mo | 2–5 y |

| Fat redistribution | 1–6 mo | 2–5 y |

| cessation of menses | 1–6 mo | _b |

| Clitoral enlargement | 1–6 mo | 1–2 y |

| Vaginal atrophy | 1–6 mo | 1–2 y |

| Deepening of voice | 6–12 mo | 1–2 y |

Estimates represent clinical observations: Toorians et al.(149), Asscheman et al. (156),Gooren et al. (157),Wierckx et al. (158).

Prevention and treatment as recommended for biological men.

Menorrhagia requires diagnosis and treatment by a gynecologist.

Voice changes

Voice changes occur primarily within the first 6 months of testosterone treatment. By six months of therapy almost all persons on testosterone can expect permanent voice changes.36

Hair growth/alopecia

Studies looking at transmasculine persons on testosterone therapy show that hair growth increases especially within the first 6 months of treatment36 but continues throughout the first year of treatment and thereafter37 hair growth is irreversible.

Androgenic alopecia may also develop in transmasculine patients with long term testosterone therapy. There may be additional therapies with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors to counteract this issue38 though these are not approved for use in persons under the age of 18 years and there is limited data to support the use of these medications.

Menstrual cessation

Menses can be a significant source of dysphoria and distress in many transmales. Use of testosterone alone often induces amenorrhea. Studies have shown that even a low dose (less than 50 mg injected subcutaneously every week) can lead to menstrual cessation in about 55% of persons with an additional 32% reporting amenorrhea by one year.39 If testosterone alone is inadequate at causing amenorrhea, progesterone-only methods, such as norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, or medroxyprogesterone, given orally or every three months intramuscular can be used as an adjunct. It is important to note that although amenorrhea may result, testosterone formulations should not be used as contraception (further discussed in Article 3, section titled “Contraception and Menstrual Suppression”.

Effect on bone mineral density

Bone mass accrual in natal females is achieved during puberty with peak bone mineral density reached between the ages of 18–20 years. It is theorized that by increasing muscle mass, testosterone will cause an increase in mechanical load on long bones and therefore would be protective against osteoporosis. There are few studies, however, that examine the effect of gender affirming hormones on bone mineral density and no studies examining the prevalence of fractures in transgender males.40 It is also unclear if the impact on bone health is reversible with cessation of testosterone therapy. One metanalyses in adult transmales demonstrated no effect of masculinizing hormone treatment on bone mineral density.41

Final height

Testosterone in natal males is aromatized to estrogen, and this gives testosterone the ability to increase both height and bone mineral density. Testosterone also modulates growth hormone levels, further playing a role in final adult height. The impact of testosterone on final height in transgender males is complicated because there are a variety of factors at play that can influence height: genetics, stage of puberty at the onset of medical therapies, presence or absence of pubertal blockers, and dosing of testosterone. Discussion of final height in transgender males on testosterone is therefore complex and often a final height prediction cannot be made with certainty.

Effect of body shape

Estrogen increases the waist-hip ratio (WHR) while testosterone decreases this ratio throughout puberty. Though there are few studies that demonstrate how WHR is changed by gender-affirming hormones; existing data demonstrates that adolescents who begin testosterone therapy achieve a lower waist-hip ratio than those transmales who start testosterone therapy into adulthood. Testosterone therapy also increases lean body mass while decreasing body fat in the pelvic region.42 Some of these changes may be irreversible.

Mood

Studies in both adolescents and adults have repeatedly shown that gender affirming hormones, including testosterone, reduce depression rates and improve symptoms of anxiety.43 There is, however, a paucity of data regarding long term mental health outcomes for transgender and gender expansive youth. There are reports of increased anger with testosterone therapy, particularly within the first seven months of treatment.44,45 Ongoing mental health support is recommended to help support transgender males both before, during, and after medical transition.

Current evidence for potential adverse effects

Data for adverse effects is derived mostly from adult data as there have been few long-term studies of transgender males who have started medical or surgical transition as adolescents.

Metabolic parameters

BMI

Testosterone therapy in adolescents has been associated with an increase in BMI.46 Studies in adults suggest that this increase in BMI may be due to an increase in lean body mass with testosterone therapy.47

Blood pressure

There are no long term studies of the effect of testosterone on blood pressure in adolescents who started on gender affirming hormones and followed into adulthood. In the short-term, one study demonstrated no change in blood pressure.46 Studies in adults have shown mixed results, and it is unclear if there are other comorbidities that lead to increases in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure.47 As will be discussed below, there is not an increase in cardiovascular events in transmales taking testosterone when compared to cismales and females. It is still recommended that blood pressure be checked every 3–6 months for transgender males on testosterone therapy.

Lipids/Cardiovascular risk

Data is unclear about whether or not there is an increase in cardiovascular risk in studies in cismales with hypogonadism using supplemental testosterone.48 With the suppression of female range estradiol, HDL levels decrease46 and LDL increase,49,50 which leads to concern that cardiovascular risk may be negatively altered. Preliminary studies from Europe have failed to show an increase in cardiovascular events or death compared with cisgender males and females. It is unclear how prolonged testosterone therapy when started in this adolescent population may alter cardiovascular risk.40

Polycythemia

Natal males have higher hemoglobin and hematocrit than natal females, and it is speculated that testosterone increases erythropoietin, thus leading to polycythemia.51

One study of adolescent transgender males showed an increase in hemoglobin and hematocrit with testosterone therapy46 and metanalyses have not shown that hemoglobin/hematocrit exceeded male typical values.47 Guidelines do recommend obtaining hemoglobin levels every 3 months5 and with dose changes to ensure hemoglobin levels do not increase past 17.5 g/dL. If polycythemia develops, lowering the dose of testosterone or phlebotomy/blood donation is an option. Additionally, the risk of clot should be discussed as polycythemia is associated with both venous and arterial thromboembolism.52

Effects on liver

While there have been a few studies which have shown mild elevations in both AST and ALT with the use of testosterone, numerous studies have shown that there are no clinically relevant changes to transaminases with testosterone therapy.46,47 The Endocrine Society recommends to check liver enzymes initially and every three months to monitor for elevations. Of note, with potential increases in BMI, transaminases may also become elevated, as in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Malignancy

Many cancers are sex hormone dependent and the role that sex hormones play in their pathogenesis is unclear. There is little data available on the effect of testosterone on the development of hormone–dependent neoplasms.

In regards to breast cancer, there was one small study which suggested that the incidence of breast cancer in transgender males is similar to that of cisgender males and is less than that of cisgender females.53 Because of the paucity of current data, transgender males should have the same breast cancer screening as cisgender females.54

In regards to cervical and uterine cancer, there have been a few case reports and cohort studies which have been unable to characterize if there is a change in risk of cervical and uterine cancer with testosterone therapy.53 Of note, many studies have shown that transgender males are less likely to be up to date on papanicolou screening than cis female counterparts.55 One study also showed that transgender males on testosterone therapy have higher rates of inadequate specimens than cisgender females, likely due to testosterone therapy as well as provider and patient comfort in specimen collection.56 The current recommendation is to follow pap smear guidelines for cis gender females and to encourage HPV vaccination for all adolescents and adults under the age of 45 years.

In regards to risk of ovarian cancer, there is insufficient evidence linking testosterone and ovarian malignancy.53 There has been one published cohort study which showed no cases of ovarian cancer in 112 transmales on a minimum of six months of testosterone therapy.53

Acne

Acne on the face, back, and chest appears within the first six months of testosterone therapy, but seems to clear away by the first year of treatment.37 To mitigate this, acne prevention and potential treatment regimens can be started with the initiation of testosterone therapy. The prescription of tetracyclines, such as minocycline and doxycycline may cause hepatic injury, however, as noted above, there is less concern for alterations in liver function with testosterone therapy. Oral isotretinoin may be indicated for persons who do not respond to more conservative acne treatments. Practitioners should counsel regarding suicide risk and pregnancy prevention prior to prescribing isotretinoin.57

Feminizing hormone regimens

Adolescents and adults who identify as transgender females may desire estrogen therapy for feminization. Exogenous estrogens can be used to induce female body changes such as breast development and fat redistribution as well as decrease body hair. As discussed previously (see Fig. 1: Criteria for Gender Affirming Hormone Treatment for Adolescents) gender affirming therapy with estradiol involves discussions between the patient, their guardian(s), mental health providers, and treating provider. Newer guidelines suggest that treatment at younger ages may alleviate gender dysphoria and allow for pubertal development concordant with same age peers.

Estradiol: Mechanism of action

Estradiol is the primary hormone responsible for the development of secondary sex characteristics in individuals assigned female at birth. The vast majority of estradiol is secreted by the ovaries. Ovarian theca cells produce estradiol precursors in response to LH stimulation, which are converted to estradiol. Though the two primary target tissues for estrogen stimulation are the female genital tract and breasts, estradiol also has effects on bone, fat distribution, and sexual drive and function. In the first three years of pubertal development, cyclic changes in estradiol and progesterone eventually result in menarche.

Similar to when treating patients with ovarian insufficiency, pubertal induction begins with low doses of estradiol that are gradually increased over time to achieve the development of female secondary sex characteristics.58 Similar regimens can be used to induce desired secondary sex characteristics in transgender females.

Formulations/Dosing

Ethinyl Estradiol, an agent previously used for feminizing hormone therapy, has been associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events, and for this reason its use is no longer recommended. The preferred formulation of estradiol for feminizing hormone therapy is with 17 beta estradiol. Multiple routes of 17 beta estradiol delivery are available, although oral and transdermal routes are used most frequently. All possible routes of delivery will be discussed here, as decisions about the ideal method of delivery may differ from patient to patient. Routes that avoid hepatic first pass metabolism (sublingual, transdermal and intramuscular) are often preferred to decrease thromboembolic risk. Additionally, some providers prefer the transdermal route specifically, because of the consistent rate of estradiol delivery and lower peak levels.58–60

Generally, the approach is to begin treatment with low doses of estradiol that are gradually increased over time based on clinical effect and laboratory monitoring. Patients who received a GnRH agonist in early puberty should receive lower starting doses of estradiol and have their doses increased more slowly given the potential impact on final height.

Lab monitoring

Baseline laboratory evaluation

Given the inconclusive data regarding the development of hyperprolactinemia and hypertriglyceridemia (which will be discussed below), the following laboratory values are routinely obtained at baseline prior to the initiation of Estradiol: prolactin, lipids, testosterone. Assessment of baseline renal function and potassium level should also be considered in patients receiving Spironolactone (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Baseline and follow-up protocol during induction of puberty.

| Every 3–6 mo |

|---|

| • Anthropometry:height, weight, sitting height, blood pressure.Tanner stages |

| Every 6–12 mo |

| • In transgender males: hemoglobinlhematocrit,lipids,testostero- ne,25OH vitamin D |

| • In transgender females: prolactin,estradiol,25OH vitamin D Every 1–2 y |

| • BMD using DXA |

| • Bone age on X-ray of the left hand (if clinically indicated) |

| BMD should be monitored into adulthood (until the age of 25–30 y or until peak bone mass has been reached). For recommendations on monitoring once pubertal induction has been completed, see Tables 14 and 15. |

Adapted from Hembree et al. (118).

Abbreviation: DXA. dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Subsequent lab monitoring

During the induction of puberty with feminizing hormone therapy, laboratory evaluation is recommended every three months for the first year and then every six to twelve months thereafter. Estradiol and testosterone levels are typically monitored to ensure estradiol levels remain in a physiologic range (100–200 pg/mL) and to ensure gradual suppression of testosterone levels to a goal level of <50 mg/dL5). In addition, patients receiving spironolactone, serum electrolytes, specifically potassium level, should also be monitored. Given the inconclusive data regarding the development of hyperprolactinemia and hypertriglyceridemia, prolactin levels and lipids are also commonly monitored in clinical practice.

Eligibility for initiation of feminizing therapy

Similar to the criteria noted above in Fig. 1, estradiol initiation can be considered in patients who have demonstrated persistent gender dysphoria and have sufficient mental capacity. It is important that all youth understand the irreversibility and potential side effects of initiating estradiol and are capable of providing informed consent (in addition to their guardian if they are under the legal age to consent for themselves).

Screening for conditions prior to estradiol therapy

In addition to Tanner staging, a thorough personal and family history should be obtained from all patients prior to estradiol initiation. Specific care should be taken to assess for the presence of any medical conditions that have the potential to increase their risk of complications related to hormone therapy. All patients should be asked whether they have a personal history of thromboembolism or migraine with aura, as either of these conditions would warrant an in-depth conversation with a patient and their guardian (if they are under the legal age of consent) to weigh the benefits of initiating estradiol with the potential risks.

Effects of estradiol therapy

Timeline of changes

The timeline of clinical changes that occur in response to feminizing hormone therapy varies significantly from individual to individual. Additionally, the importance of providing clear expectations regarding the typical timeline of expected physical changes from 17 beta estradiol administration cannot be understated. As noted in Table 4 from the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice guidelines (see Table 4),5 many patients will begin to see some noticeable changes in the first few months of therapy, but the maximum effects likely take years to develop.

TABLE 4.

Feminizing effects in transgender females.

| Effect | Onset | Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Redistribution of body fat | 3–6 mo | 2–3 y |

| Decrease i n muscle mass and strength | 3–6 mo | 1–2 y |

| Softening of skin/decreased oiliness | 3–6 mo | Unknown |

| Decreased sexualde5ire | 1–3 mo | 3–6 mo |

| Decreased spontaneous erections | 1–3 mo | 3–6 mo |

| Male sexual dysfunction | Variable | Variable |

| Breast growth | 3–6 mo | 2–3 y |

| Decreased testicular volume | 3–6 mo | 2–3 y |

| Decreased sperm production | Unknown | >3 y |

| Decreased terminal hair growth | 6–12 mo | >3 ya |

| Scalp hair | Variable | b |

| Voice changes | None | c |

Estimates represent clinical observations: Toorians et al. (149). Asscheman et al. (156). Gooren et al. (157).

Complete removal of male sexual hair requires electrolysis or laser treatment or both.

Familial scalp hair loss may occur if estrogens are stopped.

Treatment by speech pathologists for voice training is most effective.

Breast development

The degree to which feminizing hormone therapy is able to induce breast development varies greatly61). Prior studies have suggested that maximal breast development typically occurs 2 years after initiation of Estradiol,5,62 but a recent prospective cohort study suggests that maximum growth may actually occur earlier. Formulation of estradiol does not seem to impact accrual of breast tissue.

Bone mineral density (BMD)

It is critical to recognize the role pubertally mediated sex steroids play in bone mineralization during adolescence and to understand how the use of pharmacologic agents influence bone health. Given that GnRH agonists are often used for pubertal suppression in transgender patients and are associated with a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD),24 it is important to understand that estradiol can improve bone density accrual in these patients. Given existing evidence regarding the impact of estrogen on BMD in cisgender women, it is expected that hormone therapy with estradiol would have a positive influence on BMD.41,63

Final height

Little data exists regarding the influence estradiol therapy has on final height. Final height is dependent on a multitude of factors including if the patient was on pubertal suppression prior to starting estradiol and the pubertal stage/bone age when estradiol was initiated. One recent, Dutch prospective study involving 28 transgirls investigated the impact of 17 beta estradiol initiation on growth and bone maturation.64 They found that adolescents with a bone age > 15 years at the time of initiation of estradiol grew only slightly, while height gain was much more variable in adolescents with bone age between 13 and 15 years64). As the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines5 suggest, there may be a role for the use of higher doses or more rapid escalation of estradiol to decrease final height in young transgender women, though there is insufficient data investigating this approach in practice.

Mood

There is no prospective data examining the psychosocial effects of estradiol therapy in transfeminine adolescents. This dearth of data underscores the importance of facilitating access to knowledgeable and affirming behavioral health support both before and during the receipt of feminizing hormone therapy. There are however, multiple studies in transgender adults which demonstrate a decrease in depressive symptoms following the initiation of gender affirming hormone therapy.43,65,66

Current evidence for potential adverse effects

Metabolic parameters

BMI

Multiple European studies involving adult transgender women have shown that feminizing hormone therapy is associated with increases in both body fat67 and BMI.43,65 Despite these larger adult studies suggesting an association between feminizing hormones and increases in weight and BMI, some smaller studies, including one in adolescents46 have shown no significant impact on BMI.46,68,69

Blood pressure

Data regarding the impact of feminizing hormone therapy on blood pressure in adult transgender women is inconclusive.38,59 Some smaller studies have indicated that feminizing hormone therapy may be associated with decreases in systolic blood pressure.67,68,70 Notably, however, in one of these studies, the majority of participants were concurrently taking the antihypertensive agent Spironolactone, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the impact of estradiol alone on blood pressure.68 With respect to what is known about the influence of feminizing hormone therapy has on blood pressure in adolescents, a US-based retrospective study of 44 transfeminine adolescents and young adults showed no short-term change in blood pressure through 6 months of follow up.46 This uncertainty highlights the importance of routine blood pressure monitoring every three to six months with the initiation of hormone therapy as is recommended in the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines.5

Lipids

Overall, data regarding the impact feminizing hormone therapy has on lipids in adult transgender women is inconclusive.38 Two meta-analyses49,50 demonstrate increases in triglyceride levels in response to feminizing hormone therapy; however, no change in LDL, HDL or total cholesterol was found. As might be expected given the known sex differences in lipid profiles, some studies have shown improvement in HDL68,69,71 while others have not.43,67,70 Until more definitive data become available, it is reasonable to monitor lipid profiles at baseline and annually when inducing puberty in transgender females.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

It is well established that exogenous estrogen administration increases thromboembolic risk, but rates of thromboembolic events in transgender women receiving hormone therapy are rare.72,73 Prior to estradiol initiation, a thorough personal and family history regarding thromboembolic risk should be taken. Care should also be taken to identify other potentially modifiable risk factors like smoking and obesity and counsel all patients regarding how to recognize the signs and symptoms of venous thromboembolism. As is the case for cisgender women initiating therapy with estrogen containing medications, there is no recommendation to perform routine screening for underlying genetic mutations prior to initiation of estradiol. There is some thought that the use of routes of estradiol delivery that avoid first pass metabolism (such as the transdermal route) may carry lower risk for VTE development, but there have not been sufficient head to head studies to conclude this in transgender women.

Malignancy

Risk for the development of hormone sensitive malignancies with the initiation of feminizing hormone therapy is a common concern for both clinicians and patients. Two systematic reviews have recently stated that there is insufficient existing evidence to draw conclusions about the risk of breast cancer development in transgender populations.53,54 Despite these recent reviews, in two large studies involving thousands of transgender women, breast cancer incidence appears to be no higher than that seen in cisgender men.74,75 Though the body of data on incidence of prostate cancer in transgender women is also limited, one recent study found transgender women had a lower incidence of prostate cancer than cisgender men.76 Until more definitive data become available, transgender women should receive cancer screening based on current guidelines after a thorough anatomy inventory has been performed.

Hyperprolactinemia

In cisgender women, prolactinomas have been shown to occur in response to increases in endogenous estrogen levels in the context of pregnancy and with the administration of exogenous estrogen. Multiple European studies in adult transgender women have shown that increases in serum prolactin levels occur in response to feminizing hormone therapy67,77 yet there are only few cases of prolactinoma development in this population. Of note, many of the feminizing hormone therapy regimens used in these studies include the GnRH agonist, Cyproterone Acetate (CA), which is not available in the US and may be responsible for some of the increases in prolactin levels seen.69,78 No definitive data exists regarding the risk of development of hyperprolactinemia in adolescents receiving feminizing hormone therapy with or without the use of GnRH agonists commonly used in the US.46,64 Until more definitive data become available, it is reasonable to continue to monitor at least yearly prolactin levels when inducing puberty in transgender females as is suggested in the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines.5 If hyperprolactinemia develops, a thorough history and neurologic exam should be performed to evaluate for signs and symptoms of prolactinoma and imaging and consultation with Endocrinology should be strongly considered.

Drug interactions

Care should be taken to perform a thorough review of medications a patient is taking prior to the initiation of estradiol given that estrogen influences the metabolism of many routinely used medications. Existing tools such as the CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria may be helpful resources to determine potential risks associated with the concurrent use of estrogen containing medications and the influence initiation may have on other serum drug levels. It should be noted however, that there is minimal data regarding how different doses or routes of estradiol used for feminizing hormone therapy may influence other serum drug levels, therefore care should be taken to monitor these interactions closely.

Spironolactone

Given the variability in the extent to which estradiol alone suppresses testosterone levels to a cisgender female range,79 in clinical practice, 17B estradiol is commonly administered in combination with other adjunctive medications.5,80 As discussed earlier, GnRH agonists serve as potent suppressants of the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal axis and should be considered adjunctive agents in patients receiving feminizing hormone therapy. With barriers such as cost and inconsistent insurance approval, however, GnRH agonists may not be accessible for many transgender youth. The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and potassium sparing diuretic, Spironolactone, is often used for adjunctive therapy due to its ability to directly block androgen receptor binding.5 Given that there is no existing data on the use of Spironolactone alone in transgender women, it is difficult to determine the extent to which it is able to ameliorate hirsutism in transgender women. As is typically prescribed in cisgender women, Spironolactone is typically initiated with a gradual increase in dose over the course of weeks to ensure patient tolerance. Care should be taken to monitor for side effects such as hyperkalemia, increased thirst, frequent urination and lightheadedness.

Progesterone

Estradiol and progesterone are commonly used in combination in cisgender young women with ovarian insufficiency. Despite this, there is limited data for or against the use of progesterone to enhance breast development in transgender women.81 Additionally, the current version of the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines cites insufficient evidence to provide a recommendation for or against the use of progesterone in transgender women.5 Some of the fear surrounding the use of progesterone in transgender women is likely rooted in the increased risk for breast cancer and cardiovascular disease seen with estrogen and progesterone supplementation in cisgender women in the Women’s Health Initiative study.82 Given there are multiple methodologic differences that exist between this study including the study population and pharmacologic agents used, it is difficult to determine what conclusions, if any, can be made others may use different pronouns. As with all regarding the risks of progesterone use in transgender patients, it is important to ask what terminology women.

Conclusions

In short term studies gender affirming hormone treatment with both estradiol and testosterone have been shown to be safe and also have been shown to improve mental health and quality of life outcomes in patients. Additional long term studies are needed to fully understand the implications of GAH on physical and mental health in transgender patients. Care should be taken at the time of informed consent with the patient and guardians to discuss physical changes, both permanent and transient with GAH, as well as the uncertainty regarding the long term effects of therapy (refer to section titled Informed Consent Process for further discussion). Additionally, a discussion with the patient and/or guardian about desire for future fertility and fertility preservation options is necessary as there is a paucity of aggregate data on the impact of gender affirming hormones (with or without pubertal suppression) on future fertility (refer to section on fertility preservation for further discussion).

In short term studies gender affirming hormone treatment with both estradiol and testosterone have been shown to be safe and also have been shown to improve mental health and quality of life outcomes in patients.

Non-binary youth

The vast majority of existing guidelines that provide recommendations regarding the care of transgender youth focus on the care of patients who identify on the gender binary_as either male or female. It is important to recognize that gender identity exists on a spectrum, and that an increasing number of youth are identifying with a gender identity outside of these two binary gender categories. Some patients in this group may use the term nonbinary to describe their gender identity, while others may use other terms like agender or genderqueer. Some patients who identify as non-binary may use gender neutral pronouns like they/them/theirs, while others may use different pronouns. As with all patients, it is important to ask what terminology patients use to describe their gender identity and what pronouns they use so that patient-centered language can be used throughout the clinical encounter.

Patients with a non-binary gender identity may identify with varying degrees of masculinity or femininity and therefore may experience differing degrees of dysphoria with certain parts of their body. In light of this, it is critical to discuss individual goals of care with each patient to determine what, if any, pharmacologic or surgical interventions may be needed to affirm their identity. For example, a patient assigned female at birth who identifies as non-binary, might experience significant dysphoria with their chest or menstrual periods and wish to alleviate this dysphoria with masculinizing chest surgery or the use of a pharmacologic agent for menstrual suppression. They might also be interested in initiating other pharmacologic agents, such as testosterone, to further masculinize their appearance to align with their gender identity. Other patients may desire a more fluid presentation and may be able to alleviate dysphoria without the use of pharmacologic agents by accessing reversible interventions such as voice coaching or styling services. As should be discussed with all patients prior to the initiation of GnRH agonists, it critically important to set clear expectations regarding the time limitations of GnRH agonist use without the addition of sex steroids given the detrimental effect on bone health.

Gender affirming surgery

Important for providers to understand that desire for medical interventions is variable among persons and discussion about individual desires for surgical options is important.

There are a variety of surgeries that transgender individuals may desire in order to affirm their gender identity. The details of surgical interventions are beyond the scope of this article and can be found elsewhere. It is important for providers to understand that desire for medical interventions is variable among persons and discussion about individual desires for surgical options is important.

Over the last decade, there has been marked improvement in gender affirming surgical techniques and the benefits of surgery on mental health outcomes has been further delineated.5

Most guidelines cite the need for documentation of gender dysphoria with gender affirming hormone therapy for at least 12 months as a requirement for surgery. For some surgeries, the necessity of consultation with a mental health provider and documentation of adequate control of any co-morbid mental health issues is mandatory. As different surgeries have differing levels of risk, practitioners should be aware of the legal processes as well as medical risks and benefits and should familiarize themselves with new techniques in order to discuss short and long-term outcomes with patients.

As with all procedures, discussion of risks, benefits, complications, and expectations for surgery should involve a multidisciplinary team to ensure individuals are well supported in making the decision for surgery and have adequate physical and emotional support peri‑operatively. Furthermore, discussion with the individual and surgeon should entail discussions regarding individual risk of venous thromboembolism, and the need to hold hormone therapy peri‑operatively. The importance of family planning discussions is discussed elsewhere (see Article 3 section title of article 3).

Transmasculine surgeries

Chest surgery

Chest surgery for removal of chest tissue is often sought out by transgender patients, even by minors <18 years of age, and is the most common of all the transgender surgical procedures. As many report dysphoria of the chest and because there is minimal reduction in breast tissue with testosterone therapy, the Endocrine Society is permissive toward offering this at a younger, developmentally appropriate age with recommendations from mental health providers. For this reason, it is important that all pediatric providers have a basic understanding of chest surgeries and are capable of appropriately counseling patients pre and post-operatively. There are three common procedures for tissue removal, (1) “keyhole” method, (2) double incision mastectomy with free nipple grafting, and (3) semicircular circumareolar approaches.83 Hematoma is a complication most associated with need for revision.84 Individuals often have to decrease physically demanding activities until healing of the incisions is near complete at 4–6 weeks post-operatively.83

Though there is limited data, research suggests that chest surgery for transmasculine patients reduces gender dysphoria and is seen as having an overall positive impact on quality of life.85

Facial masculinization

Areas for reconstruction can include but are not limited to: the forehead, chin, and mandibular angle to create sharper lines and angulations. Because of growth of facial hair with testosterone therapy, there are few persons who opt for facial masculinization86 as the hair covers these angles of the face.

Phalloplasty

There are various methods of penile reconstruction using autologous skin grafts from various sites, including the thigh, forearm, and the hypertrophied clitoris. Some individuals may choose a penile prosthesis. Penile prosthesis have no functionality.86

Total abdominal hysterectomy with oophorectomy

Transmasculine patients may wish for their female pelvic organs to be removed. The effects on fertility should be discussed. Of note, when ovaries are removed, lower doses of testosterone may be used.

Transfeminine surgeries

Voice surgery

The pitch or frequency of the vocal sound gives the impression of femininity. For transfeminine persons, there are a variety of voice surgeries to elongate the vocal cords and reduce vocal fold mass in order to give more feminine quality to the voice in terms of pitch. Long term endpoints for these methods are lacking and, to date, there is no standard technique used by otolaryngologists for transfeminine persons.87

Facial feminization surgeries

Surgeries to reduce frontal concavity of the forehead, reduce the angle of the jaw line, and change the nasal tip to a more female profile (rhinoplasty) are options that some transfemale adults may desire and explore. Cricoid shave may also be desired to remove the Adam’s apple.86

Chest surgery

Feminizing hormones with estrogen and with or without progesterone often will increase chest growth. Many surgeons request at least 12 months on feminizing hormones at final doses in order to see the full effect of hormones on breast tissue prior to performing surgery. Options include breast augmentation with implants or fat grafting. With the fat grafting procedure, fat may be reabsorbed with resultant need for revision.88 Additionally, the risk of breast cancer with this method along with estradiol therapy has not been studied.86 Hematoma, seroma, infection, and implant rupture are relatively rare complications that may occur usually within the first 4 weeks post-operatively.89 The age of consent for chest surgery is 18 years of age per the Endocrine Society and the age of majority per WPATH.

Gender reassignment surgery

Commonly known as bottom surgery, there are several ways to create a neovagina. With creation of the neovagina, orchiectomy is often done, and reproductive life plans should be discussed prior to this surgery.86 Persons will undergo removal of the penis, creation of the neovaginal cavity, elongation of the urethra and construction of labia and clitoris. Vaginal dilation postoperatively is often needed, especially to maintain functionality. Complications include rectovaginal fistula.86

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Siobhan Gruschow M, Kinsman Sara, Dowshen Nadia. Pediatric primary care provider knowledge, attitudes, and skills in caring for gender non-conforming youth. J Adolesc Health 2018;62(Issue 2):S29.29273115 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen-Kettenis PT, Schagen SE, Steensma TD, de Vries AL, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Puberty suppression in a genderdysphoric adolescent: a 22-year follow-up. Arch Sex Behav 2011;40(4):843–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steensma TD, McGuire JK, Kreukels BP, Beekman AJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Factors associated with desistence and persistence of childhood gender dysphoria: a quantitative follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52(6):582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries AL, Steensma TD, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J Sex Med 2011;8(8):2276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102(11):3869–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafferty J, Committee On Psychosocial Aspects Of C, Family H. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2018;142(4):pii: e20182162. Epub 2018 Sep 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman E, B W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism 2012;13(4):165–232: DOI: 10.1080/15532739.15532011.15700873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milrod C, Karasic DH. Age is just a number: wPATH-Affiliated surgeons’ experiences and attitudes toward vaginoplasty in transgender females under 18 years of age in the united states. J Sex Med 2017;14(4):624–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex 2011;58(1):10–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz AL, Webb SA, Committee On B. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2016;138(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jay N, Mansfield MJ, Blizzard RM, et al. Ovulation and menstrual function of adolescent girls with central precocious puberty after therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1992;75(3):890–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevens J, Gomez-Lobo V, Pine-Twaddell E. Insurance coverage of puberty blocker therapies for transgender youth. Pediatrics 2015;136(6):1029–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatchadourian K, Amed S, Metzger DL. Clinical management of youth with gender dysphoria in Vancouver. J Pediatr 2014;164(4):906–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa R, Dunsford M, Skagerberg E, Holt V, Carmichael P, Colizzi M. Psychological support, puberty suppression, and psychosocial functioning in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J Sex Med 2015;12(11):2206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries AL, McGuire JK, Steensma TD, Wagenaar EC, Doreleijers TA, Cohen-Kettenis PT. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics 2014;134(4):696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabedian M, McKay HA, Moreno LA. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone 2010;46(2):294–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saggese G, Bertelloni S, Baroncelli GI, Battini R, Franchi G. Reduction of bone density: an effect of gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue treatment in central precocious puberty. Eur J Pediatr 1993;152(9):717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertelloni S, Baroncelli GI, Ferdeghini M, Menchini-Fabris F, Saggese G. Final height, gonadal function and bone mineral density of adolescent males with central precocious puberty after therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues. Eur J Pediatr 2000;159(5):369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neely EK, Bachrach LK, Hintz RL, et al. Bone mineral density during treatment of central precocious puberty. J Pediatr 1995;127(5):819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magiakou MA, Manousaki D, Papadaki M, et al. The efficacy and safety of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog treatment in childhood and adolescence: a single center, long-term follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95(1):109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thornton P, Silverman LA, Geffner ME, Neely EK, Gould E, Danoff TM. Review of outcomes after cessation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment of girls with precocious puberty. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2014;11(3):306–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’elemarre-van de Waal HAC-KP. Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: a protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155(Suppl 1):S131–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlot MC, Klink DT, den Heijer M, Blankenstein MA, Rotteveel J, Heijboer AC. Effect of pubertal suppression and cross-sex hormone therapy on bone turnover markers and bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) in transgender adolescents. Bone 2017;95:11–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]