Abstract

A newly identified DNA virus, named TT virus (TTV), was found to be related to transfusion-associated hepatitis. We conducted the following experiments to evaluate its pathogenic role in liver disease and potential modes of transmission. We used PCR to detect TTV DNA in serum. The rates of TTV viremia in 13 patients with idiopathic acute hepatitis, 14 patients with idiopathic fulminant hepatitis, 22 patients with chronic hepatitis, and 19 patients with cirrhosis of the liver were 46, 64, 55, and 63%, respectively, and were not significantly different from those in 50 healthy control subjects (53%). PCR products derived from seven patients with liver disease and three healthy controls were cloned and then subjected to phylogenetic analyses, which failed to link a virulent strain of TTV to severe liver disease. TTV infection was further assessed in an additional 148 subjects with normal liver biochemical tests, including 30 newborns (sera collected from the umbilical cord), 23 infants, 16 preschool children, 21 individuals of an age prior to that of sexual experience (aged 6 to 15 years), 15 young adults (aged under 30 years), and 43 individuals older than 30 years. The rates of TTV viremia were 0, 17, 25, 33, 47, and 54%, respectively. These findings suggest that TTV is transmitted mainly via nonparenteral daily contact and frequently occurs very early in life and that TTV infection does not have a significant effect on liver disease.

Although sensitive methods are available for the diagnosis of hepatitis A to E, about 10 to 15% of parentally transmitted hepatitis cases (1) and 4% community-acquired acute hepatitis cases do not have a defined etiology (2). Recently, a novel human DNA virus, named TT virus (TTV), was isolated from the serum of a Japanese patient with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology (8). TTV, like parvovirus, does not have an envelope. Its genome consists of a single-stranded, linear DNA molecule about 3,739 nucleotides in length (9). In a study by Okamoto et al. (9) in Japan, TTV DNA was detected in 47% of patients with fulminant hepatitis and 46% of patients with chronic hepatitis of unknown etiology, in comparison to 12% of accepted blood donors. Their findings suggest that TTV infection might be responsible for some cryptogenic liver diseases, including fulminant hepatitis. However, the pathogenic role of TTV in liver disease needs further investigation.

Herein we report our work on the evaluation of the pathogenic effect of TTV infection on human liver disease and on searching for potential modes of transmission of TTV, such as vertical or transplacental transmission, sexual exposure, and community contacts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Serum samples were collected from 68 patients with acute or chronic liver disease who received medical consultations in our hepatology department during the period from May 1995 to May 1998. Fifty age-matched healthy adults were included as controls. The subjects were categorized into five groups on the basis of diagnosis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of TTV infection in patients with liver disease and healthy controls

| Diagnosis of group (n) | No. (%) TTV DNA positive | Pa |

|---|---|---|

| Acute hepatitis of unknown etiology (13) | 6 (46)b | 0.903 |

| Fulminant hepatitis of unknown etiology (14) | 9 (64)b | 0.475 |

| Chronic hepatitis (22) | 12 (55)c | 0.858 |

| Chronic hepatitis B (6) | 2 | |

| Chronic hepatitis C (4) | 2 | |

| Chronic hepatitis B+C+D (1) | 1 | |

| Unknown etiology (11) | 7 | |

| Cirrhosis (19) | 12 (63)c | 0.430 |

| Chronic hepatitis B (9) | 6 | |

| Chronic hepatitis C (4) | 2 | |

| Chronic hepatitis B+C (1) | 1 | |

| Unknown etiology (5) | 3 | |

| Healthy controls (50) | 26 (53) |

Compared with the healthy controls by using the Yates corrected chi-square method.

P = 0.576.

P = 0.810.

The first group comprised 13 patients with acute hepatitis of unknown etiology. All of the subjects in this group were previously healthy subjects without remarkable medical histories who had developed typical symptoms and signs of acute viral hepatitis with elevation of serum aminotransferase activities to a level 10 times higher than the upper limit of normal. The second group comprised 14 patients with fulminant hepatitis of unknown etiology. They had typical symptoms and signs of acute hepatitis with progressive jaundice, prolonged prothrombin time, and development of stage III or IV hepatic encephalopathy within 2 weeks of the onset of jaundice. The categorization of patients with acute or fulminant hepatitis of unknown etiology was based on the following three sets of criteria: (i) seronegativity for hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg), immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies against hepatitis B virus core antigen, IgM antibodies against hepatitis A virus, antibodies against hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV), and IgM antibodies against cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus; (ii) seronegativity for HCV RNA; and (iii) no history of alcohol abuse or toxin or drug exposure.

The third group comprised 22 patients with chronic hepatitis without evidence of cirrhosis. Of these, six were seropositive for HBsAg, four were seropositive for anti-HCV and HCV RNA, and one was seropositive for HBsAg, antibodies against hepatitis delta antigen, and anti-HCV. The remaining 11 cases of chronic hepatitis were attributed to unknown etiology.

The fourth group comprised 19 patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Of them, nine were seropositive for HBsAg, four were seropositive for anti-HCV, and one was seropositive for both HBsAg and anti-HCV. The cirrhosis in the remaining five patients was attributed to unknown etiology. The categorization of chronic hepatitis of unknown etiology with or without cirrhosis was based on the following three sets of criteria: (i) seronegativity for HBsAg, anti-HCV, antinuclear antibodies, or antimitochondrial antibodies; (ii) seronegativity for HCV RNA; and (iii) no history of alcoholism or toxin or drug exposure.

The control group comprised 50 age- and sex-matched healthy individuals with normal liver biochemical tests.

To assess modes of transmission, rates of TTV viremia were further assessed in 30 newborns (sera collected from the umbilical cord at birth) and in 118 additional individuals with normal liver biochemical tests, including infants, preschool children, schoolchildren, young adults, and adults (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Rates of TTV infection in different age groups of individuals with normal liver biochemical tests

| Age group (n) | No. (%) TTV DNA positive | Pa |

|---|---|---|

| 0 days (newborn) (30) | 0 (0) | |

| Under 1 yr (23) | 4 (17) | 0.030* |

| 1 to 6 yr (16) | 4 (25) | 0.694** |

| 6 to 15 yr (21) | 7 (33) | 0.723** |

| 15 to 30 yr (15) | 7 (47) | 0.644** |

| Over 30 yr (43) | 23 (54) | 0.877** |

*, significantly different from the preceding value; **, not significantly different from the preceding value.

Detection of TTV DNA in serum.

DNA was extracted from 100 μl of each serum sample by a method previously described (6). TTV DNA was amplified by nested PCR with TTV-specific primers derived from two conserved regions of the published TTV sequences (9). The first-round and second-round PCRs were done in the same manner, using 25 and 35 cycles, respectively, with denaturation for 40 s at 94°C, annealing for 1 min at 55°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C. The nested-PCR assays were done at least twice separately for each sample. If inconsistent results were obtained, two or more assays were done to confirm the results. The amplified DNA products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Some of the amplified DNA was further confirmed by cloning it into the pGEM-T vector as previously described (5). Sequencing analyses were done with an automatic sequencer kit (ABI PRISM 337 DNA sequencer; PRISM 337 collection, Sequence Analysis 3.0; Perkin-Elmer). The sequences of the first-round PCR primers were 5′-ACAGACAGAGGAGAAGGCAACATG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GTTGGTATCCATTTAGCTCTCATT-3′ (antisense). Those of the second-round PCR primers were 5′-GGCAACATGTTATGGATAGACTGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACCTCCTGGCATTTTACCATTTTCC-3′ (antisense). Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analyses were done with the aid of computer software, using the Clustal method with a weighted-residue weight table (DNAstar, Madison, Wis.).

Statistical analyses.

The Yates corrected chi-square method was used to evaluate the statistical differences in this study. However, when the expected number of individuals in any of the cells was less than five, Fisher’s exact test was used (4).

RESULTS

TTV viremia was detected in 6 (46%) of 13 patients with acute hepatitis of unknown etiology, 9 (64%) of 14 patients with fulminant hepatitis of unknown etiology, and 26 (53%) of 50 healthy individuals (Table 1). The rate of TTV viremia in healthy controls was not significantly different from the rate in the group with acute hepatitis of unknown cause (P = 0.903) or the group with fulminant hepatitis of unknown cause (P = 0.475). The rates of TTV viremia between the groups with acute hepatitis of unknown cause and fulminant hepatitis of unknown cause were not significantly different (P = 0.576). TTV viremia was detected in 12 (55%) of 22 chronic hepatitis patients without cirrhosis and in 12 (63%) of 19 chronic hepatitis patients with cirrhosis (Table 1) (P = 0.810). Again, the rates of TTV infection in chronic hepatitis patients without or with cirrhosis were not significantly different from the rate in normal controls (P = 0.858 and P = 0.430, respectively).

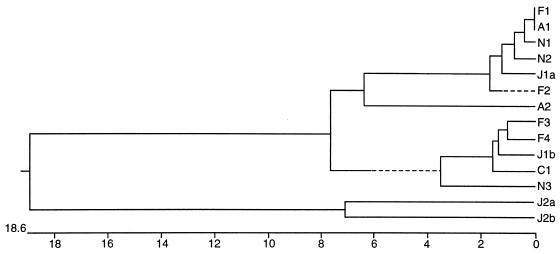

To examine whether a virulent TTV strain was responsible for liver diseases such as fulminant hepatitis or cirrhosis, and to correlate the evolutionary relationship of our isolates with the Japanese isolates, we cloned and sequenced amplified DNA from the sera of two patients with acute hepatitis, four patients with fulminant hepatitis, one patient with cirrhosis, and three healthy individuals. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that all of our TTV isolates belonged either to genotype 1a or 1b of the Japanese isolates as described by Okamoto et al. (9). No specific virulent strain of TTV related to severe liver disease, such as fulminant hepatitis or cirrhosis, was found (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of the TTV isolates from Taiwan and the prototypes of Japanese isolates. N1, N2, and N3 are the isolates from three healthy individuals; A1 and A2 are the isolates from two patients with acute hepatitis; F1, F2, F3, and F4 are the isolates from four patients with fulminant hepatitis; C1 is the isolate from a patient with liver cirrhosis. J1a, J1b, J2a, and J2b are the four Japanese prototypes of genotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b, respectively (8). Sequence comparison was made for nucleotide positions 1939 to 2166 within open reading frame 1 of the TTV genome (9). The phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the computer software Clustal method with a weighted-residue weight table (DNAstar) grounded on the sequence divergence. The length of each pair of branches represents the distance between sequence pairs. The scale beneath the tree measures the distance between sequences. Units indicate the number of substitution events.

The high prevalence of TTV infection in normal individuals in this study suggests that transmission of TTV mainly occurs via nonparenteral routes. To test this hypothesis, TTV infection was further analyzed to evaluate potential means of transmission on the basis of age. An additional 148 subjects were categorized as follows: 30 newborns (sera obtained from the umbilical cord at birth), 23 infants (age, <1 year), 16 preschool children (age, 1 to 6 years), 21 individuals without prior sexual experience (age, 6 to 15 years), 15 young adults (age, 15 to 30 years), and 23 adults over 30 years of age. The rates of TTV infection were 0, 17, 25, 33, 47, and 54%, respectively (Table 2). Neither the difference in prevalence of TTV viremia between the groups of preschool-age and school-age children (1 to 6 years versus 6 to 15 years, P = 0.852) nor the difference in prevalence of TTV viremia between the groups under and over the age of first sexual experience (6 to 15 years versus 15 to 30 years, P = 0.644) was significant. However, the difference in prevalence of TTV viremia between the groups of newborns and infants was statistically significant (P = 0.030).

DISCUSSION

Correlation of TTV infection with hepatitis was documented first by the initial identification of this virus from a Japanese patient with posttransfusion hepatitis (8) and then by the findings that the prevalence of TTV infection in patients with liver disease was higher than that in blood donors (3, 9). However, in another study from the United Kingdom, the rates of TTV infection were not significantly different between patients with liver disease and healthy individuals (7). Whether TTV causes liver disease and whether variations in clinical manifestations are due to the genetic heterogeneity of different TTV isolates remain to be investigated. In this report, we provide three lines of circumstantial evidence against the original hypothesis of a pathogenic effect of TTV on the liver. First, the rates of active TTV infection were not significantly different between patients with liver disease and normal individuals. Second, most healthy subjects in our control group did not have a previous history of liver disease (data not shown). Furthermore, a high prevalence of TTV infection in accepted blood donors has also been reported in other countries (3, 9, 10). Obviously, asymptomatic TTV infection occurs. Third, no evidence of a specific virulent strain was linked to severe liver disease such as fulminant hepatitis or cirrhosis. Similar findings of no specific virulent TTV strain were also reported by Naoumov et al. from the United Kingdom (7). Nevertheless, to clarify the role of TTV infection in human liver diseases, long-term follow-up of the individuals with persistent TTV infection is needed. Whether TTV infects and replicates in hepatocytes also remains to be clarified.

Surprisingly, a high prevalence of TTV infection was noted in our general population, which included healthy children and infants. Because most of the healthy adults, children, and infants included in our studies did not have a history of transfusion or drug abuse, TTV infection was very likely via nonparenteral routes. Similar speculation of nonparenteral transmission of TTV has also been reported in the United Kingdom (7, 10). It is, therefore, intriguing to examine potential routes of transmission of TTV, such as vertical or transplacental transmission, community contacts, and sexual exposure. However, vertical or transplacental transmission is not likely because none of 30 newborns was found to be positive for TTV infection. Possibly, the high prevalence of TTV infection in infants is attributed to close contact with a TTV-infected mother. Sexual exposure, although another possible route of transmission, may not be important in TTV transmission in our population, because the rates of infection were not significantly different between the groups under (33% of subjects aged from 6 to 15 years) and over (46% of subjects aged from 15 to 30 years) the age of first sexual activity (P = 0.644). Nevertheless, the clinical significance of the unusually high prevalence of TTV infection in our population and the means of TTV transmission are required for further investigations.

In summary, a high prevalence of active TTV infection was found in patients with liver disease, as well as in healthy adults, children, and infants, in Taiwan. TTV appears to be a highly contagious virus and is probably mainly transmitted nonparenterally. Although it may not be pathogenic to the liver, it is very important to determine whether TTV causes any disease in humans. Further studies are required to elucidate its tissue tropism, its potential pathogenic effects, and its transmission routes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pei-Ying Yang for technique assistance and Su-Chen Chi for graphics assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alter H J, Bradley D W. Non-A, non-B hepatitis unrelated to the hepatitis C virus (non-ABC) Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:110–120. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter M J, Gallagher M, Morris T T, Mayer L A, Meeks E L, Krawczynski K, Kim J P, Margolis H S. Acute non-A-E hepatitis in the United States and the role of hepatitis G virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:741–746. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703133361101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charlton M, Adjei P, Poterucha J, Zein N, Moore B, Therneau T, Krom R, Weisner R. TT-virus infection in North American blood donors, patients with fulminant hepatic failure, and cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;28:839–842. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glantz S A. How to analyze rates and proportions. In: Glantz S A, editor. Primer of biostatistics. 2nd ed. Singapore: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1989. pp. 101–137. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsieh S Y, Yang P Y, Ho Y P, Chu C M, Liaw Y F. Identification of a novel strain of hepatitis E virus responsible for sporadic acute hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1998;93:300–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<300::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liaw Y F, Tsai S L, Sheen I S, Chao M, Yeh C T, Hsieh S Y. Clinical and virological course of chronic hepatitis B virus infection with hepatitis C and D virus markers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:354–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naoumov N V, Petrova E, Thomas M G, Williams R. Presence of a newly described human DNA virus (TTV) in patients with liver disease. Lancet. 1998;352:195–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:92–97. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto H, Nishizawa T, Kato N, Ukita M, Ikeda H, Iizuka H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Hepatol Res. 1998;10:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simmons P, Davidson F, Lycett C, Prescott L E, MacDonald D M, Ellender J, Yap P L, Ludlam C A, Haydon G H, Gillon J, Jarvis L M. Detection of a novel DNA virus (TTV) in blood donors and blood products. Lancet. 1998;352:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]