Abstract

Homalodisca vitripennis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), known as the glassy-winged sharpshooter, is a xylem feeding leafhopper and an important agricultural pest as a vector of Xylella fastidiosa, which causes Pierce’s disease in grapes and a variety of other scorch diseases. The current H. vitripennis reference genome from the Baylor College of Medicine's i5k pilot project is a 1.4-Gb assembly with 110,000 scaffolds, which still has significant gaps making identification of genes difficult. To improve on this effort, we used a combination of Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing technology combined with Illumina sequencing reads to generate a better assembly and first-pass annotation of the whole genome sequence of a wild-caught Californian (Tulare County) individual of H. vitripennis. The improved reference genome assembly for H. vitripennis is 1.93-Gb in length (21,254 scaffolds, N50 = 650 Mb, BUSCO completeness = 94.3%), with 33.06% of the genome masked as repetitive. In total, 108,762 gene models were predicted including 98,296 protein-coding genes and 10,466 tRNA genes. As an additional community resource, we identified 27 orthologous candidate genes of interest for future experimental work including phenotypic marker genes like white. Furthermore, as part of the assembly process, we generated four endosymbiont metagenome-assembled genomes, including a high-quality near complete 1.7-Mb Wolbachia sp. genome (1 scaffold, CheckM completeness = 99.4%). The improved genome assembly and annotation for H. vitripennis, curated set of candidate genes, and endosymbiont MAGs will be invaluable resources for future research of H. vitripennis.

Keywords: Glassy-winged sharpshooter, leafhopper, Homalodisca vitripennis, Hemiptera, insect vector, genome assembly, genome annotation, Wolbachia, endosymbionts

Introduction

Homalodisca vitripennis, commonly known as the glassy-winged sharpshooter, is a xylem-feeding leafhopper, nonmodel insect in the order Hemiptera and an important agricultural pest of grapes, citrus, and almonds (Turner and Pollard 1959; Blua et al. 1999). The full native range of H. vitripennis includes the southeastern USA and northeastern Mexico (Triapitsyn and Phillips 2000). However, since its invasion into California in the 1990s, it has proliferated to be the most extensive vector in California of Xylella fastidiosa, the causative agent of Pierce’s disease (Sorensen and Gill 1996; Redak et al. 2004; Stenger et al. 2010; Backus et al. 2012). Unfortunately, the long-term use of insecticides to control H. vitripennis has led to high levels of resistance in California populations (Byrne and Redak 2021).

Although both a transcriptome and draft genome for H. vitripennis are available, we believe there is value in expanding and improving on these resources (Nandety et al. 2013; Hunter et al. 2016). The current H. vitripennis reference genome (Hvit v.2.0) from the Baylor College of Medicine's i5k pilot project is a 1.4-Gb assembly with 110,000 scaffolds from a lab-reared Florida line. The assembly still has significant gaps making identification of genes difficult. Likely contributing to this is the large size and repetitive nature of many insect genomes (Cernilogar et al. 2011; Jiang et al. 2012); for example, repetitive regions make up to 40% of the genomes of silkworms (Cai et al. 2012), 47% in mosquitos (Nene et al. 2007) and 60% in locusts (Wang et al. 2014). The use of long-read sequencing can improve genome contiguity when repetitive regions are present (Richards and Murali 2015). In addition to improving genome contiguity for annotation purposes, an improved assembly would enable the ability to look into chromosomal-level rearrangements, like those observed in other Hemiptera to occur as a selection for insecticide resistance (Manicardi et al. 2015).

Using a combination of Oxford Nanopore long-read sequencing technology combined with Illumina-sequencing reads, we report an improved assembly of the H. vitripennis genome and genome annotation. We briefly describe the repetitive-sequence landscape of the H. vitripennis genome and identify candidate genes of interest for future experimental work. Finally, we identify and report on obligate and facultative endosymbiont genomes from the assembly. An improved genome for H. vitripennis, particularly from an invasive Californian individual, is a critical resource needed to support on-going management strategies (e.g., RNAi, CRISPR technologies, viral, and so on), and studies of H. vitripennis population structure, which may be important for understanding resistance to nonbiological controls.

Materials and methods

Organism collection and sequencing

In August 2019, sharpshooters were collected from citrus groves across multiple locations in California as part of a study on imidacloprid resistance (Byrne and Redak 2021). Of these, three sharpshooters (designated A6, A7, and A9) were collected from an organic citrus grove [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck] in Porterville, California (Tulare County) was used for genome sequencing. The insects from this location (Tulare-Organic) were confirmed to be susceptible to imidacloprid using a topical application bioassay (Byrne and Redak 2021).

Total DNA was extracted from three Tulare-Organic individuals (A6, A7, and A9) following the 10× Genomics protocol for high molecular weight genomic DNA extraction from single insects (“DNA extraction from single insects” 2018). DNA from A6 was then constructed into a paired-end DNA library at UC Riverside Institute of Integrative Genome Biology (IIGB) Genomics Core and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 at the Vincent J. Coates Genomics Sequencing Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley producing 97 Gb in 322 M Illumina reads. In addition, DNA from all three Tulare-Organic individuals (A6, A7, and A9) was sequenced on an Oxford Nanopore MinION using an R9.4.1 flow cell. Long-fragment DNA was validated using gel electrophoresis and Qubit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A total of 1.5 µg of high-quality DNA was prepared in singleplex with a SQK LSK-109 kit using End Prep, DNA Repair, and Blunt Ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) according to the Nanopore recommended protocol. Sequence reads were basecalled using Guppy version 3.3.0 on NVIDIA Tesla-P100 GPU in the UCR High Performance Computing Cluster (https://hpcc.ucr.edu).

Additional sharpshooters collected from California citrus groves in Porterville (Tulare-Organic), Temecula (Temecula-Organic), Bakersfield (GBR-Organic), and Terra Bella (Tulare-Conventional) were confirmed to have varying levels of imidacloprid resistance (Byrne and Redak 2021). Four sharpshooters were sampled from each of these locations for a total of 16 individuals that were processed for transcriptome sequencing (Byrne and Redak 2021). For each sharpshooter, RNA was extracted from adult prothoracic leg tissue using Monarch Total RNA Mini Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Paired-end RNA-Seq libraries were constructed with NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA prep (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 to produce an average of 87 M paired reads per library (minimum library 51 M, max library 124 M reads).

Genome assembly

Genome assembly was performed with the susceptible (Tulare-Organic) individuals by sequencing A6 Illumina library and the A6, A7, and A9 Nanopore libraries. The assembler MaSuRCA v. 3.3.8 (Zimin et al. 2013), which performs read correction and extension was used in combination with Flye v. 2.5 (Lin et al. 2016; Kolmogorov et al. 2019) as implemented in MaSuRCA with parameters (LHE_COVERAGE = 35 LIMIT_JUMP_COVERAGE = 300 EXTEND_JUMP_READS = 0 cgwErrorRate = 0.20). Additional assembly parameters and related scripts, as well as all code used throughout this work, are available on GitHub and archived in Zenodo (Ettinger and Stajich 2021).

The resulting contigs were scaffolded against the existing reference assembly from the Baylor College of Medicine’s i5k pilot project (hereafter referred to as i5k) (i5K Consortium 2013; Hunter et al. 2016) available in GenBank (GCA_000696855.2) using Ragtag v. 1.0.0 (Alonge et al. 2019). Vector and contaminant screening were performed using the vecscreen option in AAFTF v0.2.4 (Stajich and Palmer 2019). Mitochondrial and endosymbiont genome identification and removal were performed as described in detail below. Assembly evaluation and comparison were performed using QUAST v. 5.0.0 (Gurevich et al. 2013) and BUSCO v. 5.0.0 (Simão et al. 2015) against both the eukaryote_odb10 and hemiptera_odb10 datasets. Assembly statistics and BUSCO status were visualized in R v. 4.0.3 using the tidyverse v. 1.3.0 package (Wickham et al. 2019; R Core Team 2020).

To investigate genome size and potential heterozygosity, we used jellyfish v. 2.3.0 (Marçais and Kingsford 2011) to count a range of k-mers (k = 19, 21, 23, 25, 27) and produce k-mer frequency histograms. We then supplied these histograms to GenomeScope v. 2.0 (Ranallo-Benavidez et al. 2020) and findGSE (Sun et al. 2018), which both provide estimates of genome size, percent heterozygosity, and percent repeat content.

Mitochondria and endosymbiont identification

The mitochondrial genome was assembled and identified from the Illumina reads using the “all” module in MitoZ v. 2.4-alpha (Meng et al. 2019). We then used Minimap v.2.1 (Li 2018) to map the mitochondrial genome against the draft H. vitripennis genome. Partial matches to the mitochondrial genome found in the draft H. vitripennis genome were subsequently hard masked. Mitochondria annotation was performed with MITOS2 (Donath et al. 2019) and the tbl file was manually checked for gene name consistency and flagged discrepancies before conversion to sqn file format for upload to NCBI.

We used the BlobTools2 pipeline (Challis et al. 2020) to identify and flag scaffolds of microbial origin for possible removal. Taxonomy of each scaffold was putatively assigned using both diamond (v. 2.0.4) and command-line BLAST v. 2.2.30+ against the UniProt Reference Proteomes database (v. 2020_10) (Camacho et al. 2009; Buchfink et al. 2015; Boutet et al. 2016). We estimated coverage by mapping reads to the scaffolds with bwa (Li and Durbin 2009) and merged and sorted the alignments using samtools v. 1.11 (Li et al. 2009). We then used the BlobToolKit Viewer to visualize the resulting putative assignments.

As an alternative method to identify possible microbial contamination in the assembly, we ran the anvi’o v.7 pipeline (Eren et al. 2015). This involved first obtaining coverage information by mapping reads to scaffolds with bowtie2 v. 2.4.2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) and samtools v. 1.11 (Li et al. 2009). We then generated a scaffold database from the draft H. vitripennis genome using “anvi-gen-contigs-database,” which calls open-reading frames using Prodigal v. 2.6.3 (Hyatt et al. 2010). Single-copy bacterial (Lee 2019), archaeal (Lee 2019), and protista (Delmont 2018) genes were then identified using HMMER v. 3.2.1 (Eddy 2011) and ribosomal RNA genes were identified using barrnap (Seemann). Putative taxonomy was assigned to gene calls using Kaiju v. 1.7.2 (Menzel et al. 2016) with the NCBI BLAST nonredundant protein database nr including fungi and microbial eukaryotes v. 2020-05-25. Next, an anvi’o profile was constructed for contigs >2.5 kbp using “anvi-profile” with the “–cluster-contigs” option, which hierarchically clusters scaffolds based on their tetra-nucleotide frequencies. Scaffolds were manually clustered into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) using a combination of hierarchical clustering, taxonomic identity, and GC content using both “anvi-interactive” and “anvi-refine.” MAG completeness and contamination were assessed using “anvi-summarize” and then again using the CheckM v. 1.1.3 lineage-specific workflow (Parks et al. 2015). MAGs were taxonomically identified using GTDBTk v.1.3.0 (Chaumeil et al. 2019), which places bins in the Genome Taxonomy Database phylogenetic tree and putatively assigns taxonomy based on ANI to reference genomes and tree topology. D-GENIES was used to align MAGs to existing reference genomes using Minimap2 from known H. vitripennis obligate symbionts, which were downloaded from GenBank: Candidatus Sulcia muelleri (GCA_000017525.1) and Ca. Baumannia cicadellinicola (GCA_000013185.1) (Wu et al. 2006; McCutcheon and Moran 2007; Cabanettes and Klopp 2018; Li 2018). MAG placement was visualized in R v. 4.0.3 using the ggtree v. 2.2.4 and treeio v. 1.12.0 packages (R Core Team 2020; Wang et al. 2020; Yu 2020).

We took the resulting scaffolds from both approaches (e.g., scaffolds that were taxonomically flagged as containing bacteria, archaea, or viruses reads by BlobTools2 and all scaffolds assigned to MAGs through the anvi’o workflow) and assessed whether to remove the scaffolds from the assembly using JBrowse2 (Buels et al. 2016). To do this, we converted diamond and BLAST taxonomy file outputs, as well as the BUSCO v. 5.0.0 (Simão et al. 2015) matches to both the eukaryote_odb10 and hemiptera_odb10 datasets, into GFF formatted files to enable their import into JBrowse2. After manual assessment of these scaffolds via JBrowse2, we proceeded with conservatively removing from the draft H. vitripennis genome only those scaffolds that were assigned to MAGs. Additional symbiont and mitochondrial regions that were identified by NCBI’s Contamination Screen were subsequently removed during deposition.

Repetitive element annotation

Prior to gene annotation, we used RepeatModeler v. 2.0.1 (Flynn et al. 2020) and RepeatMasker v. 4.1.1 (Smit et al. 2013-2015) to generate and soft mask predicted repetitive elements in the draft H. vitripennis genome (Supplementary Table S1). To visualize the repeat landscape, we used the parseRM.pl script v. 5.8.2 (https://github.com/4ureliek/Parsing-RepeatMasker-Outputs) with the “−l” option on the RepeatMasker output (Kapusta et al. 2017). The parseRM.pl script calculates the percent divergence from the consensus for each predicted repeat using the Kimura 2-Parameter distance while correcting for higher mutation rates at CpG sites. Percent divergence can be a proxy for repeat element age with older elements expected to have higher divergence due to expected accumulation of more nucleotide substitutions relative to younger elements. Here, we chose to group repeats into bins of 1% divergence. Repeat landscapes were visualized in R v. 4.0.3 using the tidyverse v. 1.3.0 package (Wickham et al. 2019; R Core Team 2020).

Genome annotation

To identify protein-coding genes and tRNAs, we used the Funannotate pipeline v. 1.8.4 on the masked genome (Palmer and Stajich 2020). Briefly, this involved first training the gene predictors on the RNAseq data using Trinity v. 2.11.0 and PASA v. 2.4.1 (Haas et al. 2003; Grabherr et al. 2011). Next, gene prediction was performed using a combination of software including Augustus v. 3.3.3, GeneMark-ETS v. 4.62, GlimmerHMM v. 3.0.4, and SNAP v 2013_11_29 (Korf 2004; Majoros et al. 2004; Stanke et al. 2006; Ter-Hovhannisyan et al. 2008). Consensus gene models were then produced using EVidenceModeler v. 1.1.1 (Haas et al. 2008) and tRNAs were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v. 1.3.1 (Lowe and Eddy 1997). Consensus gene models were then refined using the RNAseq training data from PASA, which includes untranslated region (UTR) prediction. Protein annotations were then putatively assigned for consensus gene models based on similarity to Pfam (Finn et al. 2014) and CAZyme domains (Lombard et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2018) using HMMER v.3 (Eddy 2011) and similarity to MEROPS (Rawlings et al. 2014), eggNOG v. 2.1.0 (Huerta-Cepas et al. 2016), InterProScan v. 5.47-82.0 (Jones et al. 2014), and Swiss-Prot (Boutet et al. 2016) by diamond BLASTP v. 2.0.8 (Buchfink et al. 2015). In addition, Phobius v. 1.01 (Käll et al. 2004) was used to predict transmembrane proteins and SignalP v. 5.0b (Armenteros et al. 2019) was used to predict secreted proteins. Problematic gene models flagged by Funannotate were manually curated as needed. To investigate gene model support, we used STAR v. 2.7.5a to align transcriptome reads to the assembly and then used featureCounts v1.6.2 to generate read counts per gene model (Dobin et al. 2013; Liao et al. 2014). Read counts per gene model were then summarized in R v. 4.0.3 using the tidyverse v. 1.3.0 package (Wickham et al. 2019; R Core Team 2020).

Identification of genes of interest for future experimental work

We identified candidate genes that could be used as either (1) phenotypic markers, or (2) whose promoters may prove useful for future manipulative experiments using CRISPR technologies. Protein sequences for genes of interest were identified and downloaded from a variety of sources including (1) FlyBase (https://flybase.org/) to obtain orthologs in Drosophila melanogaster, (2) FlyBase to identify the closest Hemiptera annotated orthologs, and (3) the literature (Supplementary Table S2). Protein sequences were searched against the draft H. vitripennis genome using phmmer in HMMER v. 3.3.1 (Eddy 2011). Top hits were aligned using MUSCLE v. 3.8.1551 (Edgar 2004). Maximum likelihood trees based on these alignments were produced using FastTree v. 2.0.0 (Price et al. 2010) to confirm putative candidate status.

Results and discussion

Homalodisca vitripennis predicted genome characteristics

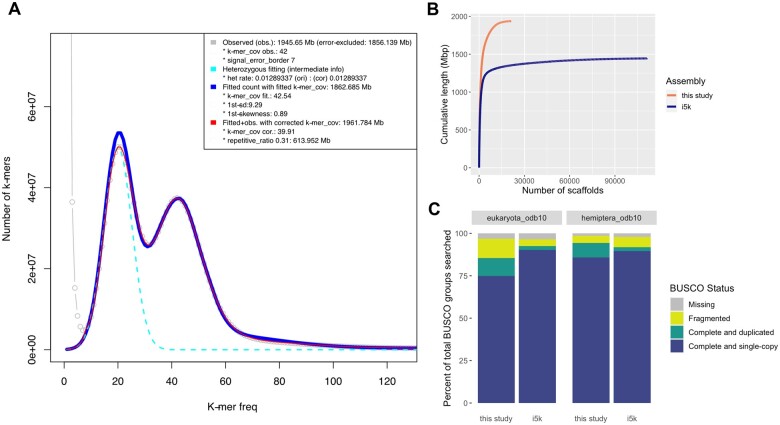

Genome size estimates from GenomeScope ranged from 1.74 to 1.75 Gb, whereas estimates from findGSE were higher, ranging from 1.89 to 1.96 Gb (Figure 1A, Table 1). Both of these approximations are larger than the size of the i5k project reference assembly (1.44 GB). Despite the diversity represented by the Hemiptera (∼82,000 species), relatively few genome sequences for this group are available (Panfilio and Angelini 2018). The predicted genome size of H. vitripennis fits within the current reported range of genome size estimates for Hemiptera [from 327 Mb in aphids (Biello et al. 2021) to 8.9 Gb in spittlebugs (Rodrigues et al. 2016)] with bloated genome sizes predicted for many members of the Auchenorrhyncha, particularly members of the Cicadidae (Hanrahan and Johnston 2011; Panfilio and Angelini 2018). The predicted heterozygosity of the assembly here was high with the GenomeScope estimates ranging from 1.56 to 1.68%, while the findGSE estimates were lower, ranging from 1.16 to 1.29%. High heterozygosity is not uncommon in Hemiptera and has been reported in planthoppers (Zhu et al. 2017), milkweed bugs (Panfilio et al. 2019), and aphids (Mathers et al. 2020).

Figure 1.

Genome assembly assessment and comparison. (A) k-mer frequency histogram output from findGSE using k = 21. The gray line represents the observed k-mer frequency, the teal line represents the fit for the heterozygous k-mer peak, the blue line represents the fitted model without k-mer correction, and the red line represents the fitted model with k-mer correction, which is used to estimate the genome size. (B) Plot depicting cumulative sequence length (y-axis) as the number of scaffolds increases (x-axis) comparing the H. vitripennis draft genome in this study to the reference genome from the i5k project. (C) Stacked barcharts depicting BUSCO analyses for the eukarytota_odb10 and hemiptera_odb10 gene sets for both the H. vitripennis genome reported here and the i5k reference genome. Bars show the percent of genes found in each assembly as a percentage of the total gene set and are colored by BUSCO status (missing = gray, fragmented = yellow, complete and duplicated = green, and complete and single-copy = blue).

Table 1.

Estimates of genome heterozygosity, length, and repeat content

| Genomescope | findGSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| k = 19 | Heterozygosity (%) | 1.65 | 1.26 |

| Genome haploid size (Gb) | 1.74 | 1.9 | |

| Repeat (%) | 45.86 | 37.79 | |

| k = 21 | Heterozygosity (%) | 1.68 | 1.29 |

| Genome haploid size (Gb) | 1.74 | 1.96 | |

| Repeat (%) | 36.91 | 31.3 | |

| k = 23 | Heterozygosity (%) | 1.65 | 1.29 |

| Genome haploid size (Gb) | 1.75 | 1.93 | |

| Repeat (%) | 34.28 | 28.93 | |

| k = 25 | Heterozygosity (%) | 1.6 | 1.27 |

| Genome haploid size (Gb) | 1.75 | 1.89 | |

| Repeat (%) | 33.14 | 27.55 | |

| k = 27 | Heterozygosity (%) | 1.56 | 1.16 |

| Genome haploid size (Gb) | 1.75 | 1.96 | |

| Repeat (%) | 32.37 | 27.03 |

These estimates include the percentage heterozygosity, haploid genome size and percentage of repeat content based on k-mer analysis using GenomeScope and findGSE for a range of k-mers (k = 19, 21, 23, 25, 27).

Homalodisca vitripennis genome assembly

The resulting H. vitripennis draft genome was assembled into 21,254 scaffolds totaling 1.93 Gb of sequence at 71x coverage with an N50 of 650 Mb (Figure 1B, Table 2). This is an improvement over the current i5k project reference genome, which has 111,110 scaffolds and has a similar N50 of 656 Mb. In addition, the genome length of the assembly here is in-line with the estimated size range from findGSE (1.89–1.96 Gb).

Table 2.

Assembly statistics and assessment

| Assembly | This study | i5k | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUAST | # contigs | 34,952 | 149,799 |

| # scaffolds (≥0 bp) | 21,254 | 111,110 | |

| # scaffolds (≥1000 bp) | 19,715 | 59,570 | |

| # scaffolds (≥5000 bp) | 14,959 | 13,241 | |

| # scaffolds (≥10,000 bp) | 12,524 | 7,359 | |

| # scaffolds (≥25,000 bp) | 8,796 | 4,438 | |

| # scaffolds (≥50,000 bp) | 5,168 | 3,132 | |

| Total length (≥0 bp) | 1,930,946,379 | 1,445,215,006 | |

| Total length (≥1000 bp) | 1,929,918,132 | 1,418,424,409 | |

| Total length (≥5000 bp) | 1,916,091,697 | 1,325,420,810 | |

| Total length (≥10,000 bp) | 1,898,148,486 | 1,285,066,097 | |

| Total length (≥25,000 bp) | 1,833,358,540 | 1,240,043,308 | |

| Total length (≥50,000 bp) | 1,703,319,989 | 1,194,181,890 | |

| Largest contig | 7,378,560 | 7,131,305 | |

| GC (%) | 32.87 | 32.65 | |

| N50 | 650,435 | 656,130 | |

| N75 | 171,660 | 211,051 | |

| L50 | 750 | 542 | |

| L75 | 2,178 | 1,423 | |

| # N's per 100 kbp | 71.13 | 3,005.46 | |

| BUSCO: hemiptera_odb10 | Complete BUSCOs (C) | 2,367 (94.3%) | 2,306 (91.9%) |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 2,152 (85.7%) | 2,247 (89.5%) | |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 215 (8.6%) | 59 (2.4%) | |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 108 (4.3%) | 150 (6.0%) | |

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 35 (1.4%) | 54 (2.1%) | |

| Total BUSCO groups searched | 2,510 | 2,510 | |

| BUSCO: eukaryota_odb10 | Complete BUSCOs (C) | 218 (85.5%) | 236 (92.6%) |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 191 (74.9%) | 230 (90.2%) | |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 27 (10.6%) | 6 (2.4%) | |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 29 (11.4%) | 10 (3.9%) | |

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 8 (3.1%) | 9 (3.5%) | |

| Total BUSCO groups searched | 255 | 255 |

Various statistics calculated by QUAST for the assembly in this study and the i5k reference assembly are provided here including the number of contigs in the assembly, the number of scaffolds of various lengths, the total assembly length, percent GC, the N50, and the L50. All statistics from QUAST are based on contigs of size ≥3000 bp, unless specifically noted (e.g., “# contigs (≥0 bp)” and “Total length (≥0 bp)” include all contigs in each assembly). We also report here the results of the BUSCO assessment of both assemblies using the hemiptera_odb10 and eukaryota_odb10 gene sets.

Assessment with the BUSCO Hemiptera set showed minor improvement in genome completion (94.3%) over the i5k reference genome (91.9%), but more duplications (8.6 vs 2.4%) (Figure 1C, Table 2). Using the BUSCO eukaryota_odb10 set, the draft genome here was actually less complete (85.5%) compared to the i5k reference genome (92.6%), although both were similarly complete when taking into account fragmented BUSCOs (96.9% here vs 96.5% i5k). The increased number of fragmented and duplicated BUSCOs may be in part due to the moderate heterozygosity (e.g., haplotigs—allelic variants assembled as separate scaffolds), but is more likely the result of poor assembly of repetitive regions given the relatively high proportion of genome predicted to be repetitive (described below).

Endosymbiont identification and assessment include high-quality draft MAG from Wolbachia sp.

Like many sap-feeding insects, H. vitripennis relies on obligate symbioses with bacterial species for biosynthesis of essential amino acids, which are limited in its xylem-based diet (Wu et al. 2006; McCutcheon and Moran 2007). The first of these obligate endosymbionts is Ca. Sulcia muelleri, which has a reduced genome (∼243 kb) (Moran et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2006; McCutcheon et al. 2009). The second obligate endosymbiont is Ca. Baumannia cicadellinicola has a relatively larger genome (∼686 kb) likely due to its more recent acquisition by H. vitripennis as a symbiont (Moran et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2006; Bennett and Moran 2013; Moran and Bennett 2014). In addition to these two obligate symbionts, Wolbachia sp. have been observed as abundant facultative symbionts in this species (Moran et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2006; Curley et al. 2007; Hail et al. 2011; Rogers and Backus 2014; Welch et al. 2015; Pascar and Chandler 2018).

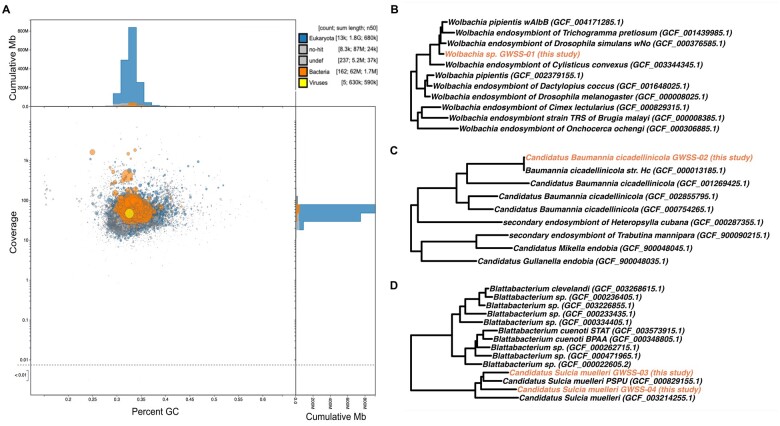

To identify potential contaminant reads due to obligate or facultative symbionts in the H. vitripennis draft genome, we used two complementary methods, BlobTools2 and anvi’o (Figure 2). BlobTools2 flagged 167 scaffolds as possible contaminants (Figure 2A). Of these, 19 were confirmed to also belong to draft MAGs assembled in anvi’o, and all scaffolds mapping to MAGs were subsequently removed from the H. vitripennis assembly. In total, we generated four draft MAGs for removal from the H. vitripennis draft genome assembly (Table 3). These included one near-complete (> 99%) high-quality Wolbachia sp. MAG (Figure 2B), one partial Ca. Baumannia cicadellinicola MAG (Figure 2C), and two partial Ca. Sulcia muelleri MAGs (Figure 2D). The two partial Ca. Sulcia muelleri MAGs likely represent a single haplotype. However, we have conservatively kept these separate due to differences in mean coverage and a shared 33,879 bp region (possibly resulting from real biological variation between the three sharpshooters sequenced or an artifact of assembly). Genomic comparisons between the near-complete Wolbachia sp. (GWSS-01) and other Wolbachia sp. may help shed light on the possible function (or lack thereof) of this facultative endosymbiont when associated with H. vitripennis. In addition, we hope that this MAG may serve as a useful resource for potential Wolbachia-mediated insect-control for H. vitripennis in its invasive range (Zabalou et al. 2004; Brelsfoard and Dobson 2009; Bourtzis et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Endosymbiont assessment in genome and identification. (A) BlobTools2 visualization of H. vitripennis scaffolds showing taxa-colored GC coverage plot. Each circle represents a scaffold in the assembly, scaled by length, and colored by superkingdom (eukaryota = blue, bacteria = orange, viruses = yellow, and unidentified = gray). On the x-axis is the average GC content of each scaffold and on the y-axis is the average coverage of each scaffold to the draft assembly. The marginal histograms show cumulative genome length (Mb) for coverage (y-axis) and GC content bins (x-axis). (B) Placement of Wolbachia sp. GWSS-01 (colored in orange) in the GTDB phylogenetic tree. (C) Placement of Ca. Baumannia cicadellinicola GWSS-02 (colored in orange) in the GTDB phylogenetic tree. (D) Placement of Ca. Sulcia muelleri GWSS-03 and GWSS-04 (colored in orange) in the GTDB phylogenetic tree.

Table 3.

Genome feature summary for endosymbiont MAGs

| MAG ID | Taxonomy | Total length (bp) | Number of scaffolds | N50 | Mean coverage | GC (%) | Number of genes | 16S rRNA copy present | Completion (%) | Redundancy (%) | Reference alignment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWSS-01 | Wolbachia sp. | 1,712,771 | 1 | 1,712,771 | 93.10 | 33.66 | 1,691 | Yes | 99.36 | 1.71 | NA |

| GWSS-02 | Ca. Baumannia cicadellinicola | 610,888 | 12 | 78,712 | 1280.76 | 32.65 | 531 | Yes | 66.46 | 1.25 | 66.40 |

| GWSS-03 | Ca. Sulcia muelleri | 209,259 | 1 | 209,259 | 1592.13 | 24.95 | 199 | Yes | 25.86 | 0 | 70.55 |

| GWSS-04 | Ca. Sulcia muelleri | 179,112 | 6 | 41,952 | 786.73 | 26.84 | 148 | No | 17.76 | 1.34 | 33.10 |

Genomic characteristics are summarized for each MAG, including putative taxonomic identity, length (bp), number of scaffolds, N50, mean coverage, percent GC content, number of genes, presence of 16S ribosomal RNA gene, completion and contamination estimates as generated by CheckM, and alignment to an existing reference genome using D-GENIES. MAGs are sorted by percent completion.

Homalodisca vitripennis genome annotation

In total, 98,296 protein-coding genes (91.5% of which are complete with both a stop and start codon) and 10,466 tRNA genes were predicted in the H. vitripennis using the funannotate pipeline (Table 4). This is almost twice the number reported by the previous transcriptome effort (47,265 protein-coding genes) (Nandety et al. 2013), but is consistent with the number of transcripts (106,998) reported for the transcriptome of H. liturata (Tassone et al. 2017). Of the 98,296 protein-coding genes reported here, approximately 38.3% (37,652) had at least one database match. In comparison, 45% (23,547) of predicted proteins in the transcriptome reported by Nandety et al. (2013) had database matches. The mean annotation edit distances (AED) reported for the predicted coding sequences (CDS) was 0.002 and for the mRNA was 0.024. AEDs are a measure of concordance between the gene models and input evidence (such as the transcriptome evidence provided to PASA) with low values like those obtained in this study indicating support for gene models. Furthermore, 58.6% (63,358) of gene models had at least one transcriptome read that aligned in our post-annotation assessment, indicating strong support for at least half of the predicted models. Only adult prothoracic leg tissue transcriptomes were sequenced here, so this value is likely an underestimate. Additional transcriptome data across a range of body parts and developmental stages would be necessary to further confirm the remaining predictions.

Table 4.

Genome annotation statistics

| Total gene models | 108,762 |

| Total number protein-coding genes | 98,296 |

| Total number of tRNAs | 10,466 |

| Total number of complete CDS | 89,929 |

| Total number of exons | 351,975 |

| Total number of CDS | 322,333 |

| Mean CDS AED | 0.002 |

| Mean mRNA AED | 0.024 |

| Mean gene size (bp) | 2,958.4 |

| Mean exon length (bp) | 214.9 |

| Mean CDS length (bp) | 193.9 |

| Mean 5'UTR length (bp) | 148.9 |

| Mean 3'UTR length (bp) | 810.9 |

| Mean tRNA length (bp) | 70.2 |

| Total number of gene models with 2 isoforms | 628 |

| Total number of gene models with 3 isoforms | 52 |

| Total number of gene models with 4 isoforms | 5 |

| Proteins with PFAM domain (%) | 14.4 |

| Proteins with InterProScan Hit (%) | 23 |

| Proteins with EggNog Hit (%) | 24.3 |

A summary of genome annotation results is reported here including the total number of gene models, protein-coding genes, tRNAs, complete (e.g., having both a start and stop codon) coding sequences (CDS), exons, and CDS regions, the mean CDS and mRNA annotation edit distances (AED), the mean gene size (bp), exon length (bp), CDS length (bp), 5'-UTR length (bp), 3'-UTR length (bp), and tRNA length (bp), the total number of gene models with 2, 3, or 4 isoforms, and the percentage of proteins with a PFAM domain, InterProScan or EggNog match.

The number of protein-coding genes predicted here, although similar to the number reported from the transcriptome of H. liturata, is substantially higher than the number of curated predictions from genomes of other Hemiptera species [ranging from 15,456 in Rhodnius prolixus (Mesquita et al. 2015) to 36,985 in Cimex lectularius (Rosenfeld et al. 2016)]. However, as of 2019, only 16 curated genome annotations were available in NCBI belonging to members of Hemiptera (Li et al. 2019). With the lack of reference genomes and annotations for Hemiptera, additional sequencing and annotation of close relatives of H. vitripennis may reveal similarly increased numbers of gene models. Given the high heterozygosity of the genome, however, overestimation or fragmentation of gene models during the predictions cannot be completely ruled out. Leveraging long-read sequencing technologies should help to further overcome any remaining gene-model fragmentation and future work should seek to validate and refine these predicted gene models.

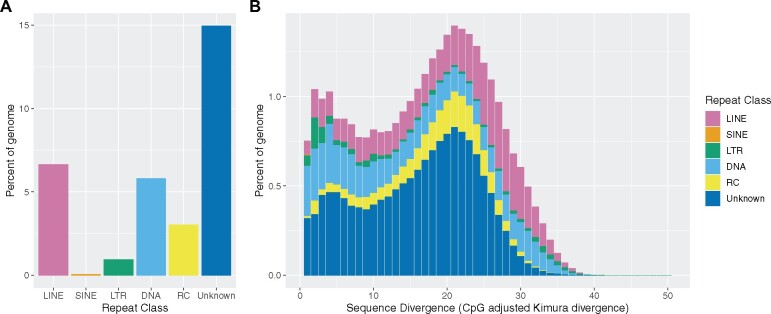

Repeat landscape indicates two possible expansion events

The estimated percentage of the genome that was repetitive was relatively high (GenomeScope = 32.37–45.86%; findGSE = 27.03–37.79%), with ultimately 33.06% of the genome being identified and masked as repetitive by RepeatMasker (see Supplementary Table S1 for detailed breakdown). This value is similar to other Hemiptera genomes, e.g., 23.0% in Laodelphax striatellus (Zhu et al. 2017), 38.9% in Nilaparvata lugens (Xue et al. 2014), 39.7% in Sogatella furcifera (Zhu et al. 2017), 45% in Bemisia tabaci (Chen et al. 2016), 56.6% in Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Xie et al. 2020), and 60% in Locusta migratoria (Wang et al. 2014), as well as other insect genomes, e.g., 33% in Tribolium castaneum (Richards et al. 2008), 40% in Bombyx mori (Cai et al. 2012), and 47% in Aedes aegypti (Nene et al. 2007). However, in contrast, Nandety et al. (2013) reported that only ∼1% of the H. vitripennis transcriptome represented repetitive elements. One possible explanation for this is that the majority of repeat content in H. vitripennis is not in coding regions and was not captured by previous transcriptome efforts.

The most abundant repeat elements (∼18% of genome) in H. vitripennis were unclassified, followed by LINES (∼6.7% of genome) and DNA elements (5.8% of genome) (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table S1). Generally, this repeat element diversity was consistent with other Hemiptera (e.g., Petersen et al. 2019). In addition, the repeat landscape indicates that elements have accumulated gradually through time in this species and also exposes two possible expansions of repeat content, one ancient (corresponding to ∼21% divergence) and one more recent (corresponding to 2–4% divergence) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Repetitive element diversity and divergence landscape. (A) A barplot representing the percent of the genome composed of elements from each repeat class. (B) A stacked barplot representing the percent of the genome made of repeat elements from each repeat class binned by 1% sequence divergence (CpG adjusted Kimura divergence). Bars are colored repeat class (LINE = pink, SINE = orange, LTR = green, DNA = light blue, RC = yellow, and Unknown = dark blue). Abbreviations: long-interspersed nuclear element (LINE), small-interspersed nuclear element (SINE), long-terminal repeat retrotransposon (LTR), DNA transposons (DNA), and rolling-circle transposons (RC).

Identification of 27 candidate genes as tools for use in genetic analyses

We identified 14 candidate genes that can be used as phenotypic markers and 13 candidate genes whose promoters may prove useful for future manipulative experiments (e.g., using CRISPR technologies) (Table 5). Of the 14 candidate morphological markers identified, nine are involved in eye color, one in body color, three in wing morphology, and one in eye morphology. These phenotypes are predicted based on known phenotypes in D. melanogaster where these genes have been useful resources for genetic analysis for years (Chyb and Gompel 2013). For the 13 candidate genes with promoters of interest, we searched for and identified four actin genes, two polyubiquitin genes, one exuperantia (exu) gene, one vasa gene, and five beta-tubulin genes. In order to genetically manipulate H. vitripennis, we first need to identify genes with promoters that are constitutively expressed, or expressed in tissues and developmental stages of interest. We believe that the reported collection of phenotypic marker genes and genes with promoters of interest, will be a useful resource for the community of researchers using genetic tools in this species.

Table 5.

Orthologous candidate genes identified for use in genetic analyses

| Gene name | Gene ID | Category | Scaffold | Start | Stop | Strand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scarlet | J6590_063422 | Eye color marker | scaffold_912 | 460005 | 478693 | − |

| brown | J6590_023567 | Eye color marker | scaffold_152 | 394070 | 408336 | + |

| white | J6590_025764 | Eye color marker | scaffold_175 | 597341 | 620522 | − |

| punch | J6590_079319 | Eye color marker | scaffold_1776 | 27869 | 36915 | − |

| purple | J6590_010106 | Eye color marker | scaffold_46 | 401764 | 405463 | + |

| cinnabar | J6590_030756 | Eye color marker | scaffold_237 | 304451 | 312309 | + |

| rosy | J6590_021669 | Eye color marker | scaffold_136 | 1442727 | 1477619 | − |

| sepia | J6590_059208 | Eye color marker | scaffold_778 | 21807 | 32946 | + |

| vermilion | J6590_086284 | Eye color marker | scaffold_2636 | 59559 | 69160 | + |

| ebony | J6590_055645 | Body color marker | scaffold_679 | 520340 | 534402 | − |

| curly | J6590_045190 | Wing shape marker | scaffold_458 | 853125 | 882297 | + |

| miniature | J6590_040001 | Wing shape marker | scaffold_363 | 1027789 | 1033916 | + |

| vestigal | J6590_019057 | Wing shape marker | scaffold_113 | 220253 | 229632 | + |

| bar | J6590_017333 | Eye shape marker | scaffold_97 | 1592445 | 1593704 | − |

| actin | J6590_029566 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_221 | 1237702 | 1242922 | + |

| actin | J6590_045793 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_469 | 433018 | 434887 | − |

| actin | J6590_054039 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_640 | 212856 | 215547 | − |

| actin | J6590_054038 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_640 | 189320 | 196363 | − |

| polyubiquitin | J6590_108590 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_4772 | 8657 | 13082 | + |

| polyubiquitin | J6590_108371 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_193 | 446565 | 453062 | + |

| exuperantia | J6590_010109 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_46 | 468344 | 476975 | − |

| vasa ATP-dependent RNA helicase | J6590_020497 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_126 | 1164356 | 1180159 | − |

| β-tubulin at 60D | J6590_031071 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_241 | 149582 | 155900 | + |

| β-tubulin at 56D | J6590_027853 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_199 | 1301426 | 1304526 | + |

| β-tubulin at 85D | J6590_005648 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_20 | 2635108 | 2648607 | − |

| β-tubulin at 97EF | J6590_073055 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_1324 | 191354 | 201726 | − |

| Tub2B | J6590_064570 | Promoter of interest | scaffold_950 | 15066 | 25700 | − |

Here for each identified gene, we provide the gene name, gene ID (e.g., the loci name provided to NCBI), scaffold number, strand direction, and start and stop locations. We also report the category of interest for each gene. Broadly, these fall into two larger groupings: (1) promoter of interest or (2) a morphological marker category based on phenotype from the literature (e.g., eye color, body color, wing shape, and eye shape).

Conclusions

Using a combination of Oxford Nanopore long-read and Illumina short-read technologies, we generated an improved reference genome for H. vitripennis of 21,254 scaffolds and a total genome size of 1.93 Gb. As part of this process, we also assembled four endosymbiont genomes, including a high-quality near complete Wolbachia sp. We further provide a first pass at genome annotation for H. vitripennis, predicting 98,296 protein-coding genes and 10,466 tRNA genes, of which 38.3% had homology matches to current databases. As an additional community resource, we identified 27 orthologous candidate genes of interest to be leveraged in future studies that seek to genetically manipulate H. vitripennis. Given the increasing role of H. vitripennis as an invasive agricultural pest, we hope that the generated genome assembly, endosymbiont MAGs, annotation and curated set of candidate genes will serve as important resources for future genomics, genetics, biocontrol, and insect biology research of H. vitripennis, other sharpshooters, and leafhoppers.

Data availability

The draft H. vitripennis Tulare genome assembly, annotation, and mitochondrial genome are deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JAGXCG000000000. The version described in this paper is version JAGXCG010000000. The raw sequence reads for the genome and RNA-Seq are available through BioProjects PRJNA717305 and PRJNA717315, respectively. The four MAG assemblies are available from BioProject PRJNA723626 and are deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession numbers JAGTUP000000000, JAGTUQ000000000, JAGTUR000000000, and JAGTUS000000000. Data analysis, assembly, and annotation-related scripts for this work are available on GitHub (https://github.com/stajichlab/GWSS_Genome) and archived in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4891938) (Ettinger and Stajich 2021).

Supplementary material is available at G3 online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nancy A. Moran (ORCID: 0000-0003-2983-9769) for helpful comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Funding

J.E.S. is a CIFAR Fellow in the program Fungal Kingdom: Threats and Opportunities and partially supported by USDA Agriculture Experimental Station at the University of California, Riverside and NIFA Hatch projects CA-R-PPA-5062-H. This work was supported by the Pierce's Disease Control program (sponsor award #: 14-0379-000-SA-2) to F.J.B. and R.R., a California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) agreement # 007011-003 to R.R. and F.J.B., and a CDFA agreement # 20-0267 to R.R., L.L.W., P.W.A., and J.E.S.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Literature cited

- Alonge M, Soyk S, Ramakrishnan S, Wang X, Goodwin S, et al. 2019. RaGOO: fast and accurate reference-guided scaffolding of draft genomes. Genome Biol. 20:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenteros JJA, Tsirigos KD, Sønderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, et al. 2019. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol. 37:420–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backus EA, Andrews KB, Shugart HJ, Carl Greve L, Labavitch JM, et al. 2012. Salivary enzymes are injected into xylem by the glassy-winged sharpshooter, a vector of Xylella fastidiosa. J Insect Physiol. 58:949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GM, Moran NA.. 2013. Small, smaller, smallest: the origins and evolution of ancient dual symbioses in a phloem-feeding insect. Genome Biol Evol. 5:1675–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biello R, Singh A, Godfrey CJ, Fernández FF, Mugford ST, et al. 2021. A chromosome-level genome assembly of the woolly apple aphid, Eriosoma lanigerum Hausmann (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Mol Ecol Resour. 21:316–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blua MJ, Phillips PA, Redak RA.. 1999. A new sharpshooter threatens both crops and ornamentals. Cal Ag. 53:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K, Dobson SL, Xi Z, Rasgon JL, Calvitti M, et al. 2014. Harnessing mosquito–Wolbachia symbiosis for vector and disease control. Acta Tropica. 132:S150–S163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet E, Lieberherr D, Tognolli M, Schneider M, Bansal P, et al. 2016. UniProtKB/Swiss-prot, the manually annotated section of the uniprot knowledgebase: how to use the entry view. Methods Mol Biol. 1374:23–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brelsfoard CL, Dobson SL.. 2009. Wolbachia-based strategies to control insect pests and disease vectors. Asia Pac J Mol Biol Biotechnol. 17:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH.. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 12:59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buels R, Yao E, Diesh CM, Hayes RD, Munoz-Torres M, et al. 2016. JBrowse: a dynamic web platform for genome visualization and analysis. Genome Biol. 17:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne FJ, Redak RA.. 2021. Insecticide resistance in California populations of the glassy-winged sharpshooter Homalodisca vitripennis. Pest Manag Sci. 77:2315–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanettes F, Klopp C.. 2018. D-GENIES: dot plot large genomes in an interactive, efficient and simple way. PeerJ. 6:e4958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Zhou Q, Yu C, Wang X, Hu S, et al. 2012. Transposable-element associated small RNAs in Bombyx mori genome. PLoS One. 7:e36599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, et al. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 10:421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernilogar FM, Onorati MC, Kothe GO, Burroughs AM, Parsi KM, et al. 2011. Chromatin-associated RNA interference components contribute to transcriptional regulation in Drosophila. Nature. 480:391–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis R, Richards E, Rajan J, Cochrane G, Blaxter M.. 2020. BlobToolKit - interactive quality assessment of genome assemblies. G3 (Bethesda). 10:1361–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumeil P-A, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH.. 2019. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Hasegawa DK, Kaur N, Kliot A, Pinheiro PV, et al. 2016. The draft genome of whitefly Bemisia tabaci MEAM1, a global crop pest, provides novel insights into virus transmission, host adaptation, and insecticide resistance. BMC Biol. 14:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyb S, Gompel N.. 2013. Atlas of Drosophila Morphology: Wild-Type and Classical Mutants. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curley CM, Brodie EL, Lechner MG, Purcell AH.. 2007. Exploration for facultative endosymbionts of glassy-winged sharpshooter (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 100:345–349. [Google Scholar]

- Delmont T. 2018. Assessing the completion of eukaryotic bins with anvi’o.

- DNA extraction from single insects, 2018. 10X Genomics. https://support.10xgenomics.com/permalink/7HBJeZucc80CwkMAmA4oQ2 [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, et al. 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath A, Jühling F, Al-Arab M, Bernhart SH, Reinhardt F, et al. 2019. Improved annotation of protein-coding genes boundaries in metazoan mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:10543–10552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. 2011. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput Biol. 7:e1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics. 5:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren AM, Murat Eren A, Esen ÖC, Quince C, Vineis JH, et al. 2015. Anvi’o: an advanced analysis and visualization platform for ‘omics data. PeerJ. 3:e1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger CL, Stajich JE.. 2021. stajichlab/GWSS_Genome v1.0. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4891938. [DOI]

- Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, et al. 2014. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D222–D230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, et al. 2020. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:9451–9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, et al. 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 29:644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G.. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 29:1072–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Mount SM, Wortman JR, Smith RK Jr, et al. 2003. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:5654–5666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, et al. 2008. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9:R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hail D, Lauzìere I, Dowd SE, Bextine B.. 2011. Culture independent survey of the microbiota of the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis) using 454 pyrosequencing. Environ Entomol. 40:23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan SJ, Johnston JS.. 2011. New genome size estimates of 134 species of arthropods. Chromosome Res. 19:809–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Zhang H, Wu P, Entwistle S, Li X, et al. 2018. dbCAN-seq: a database of carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZyme) sequence and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46:D516–D521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Forslund K, Cook H, Heller D, et al. 2016. eggNOG 4.5: a hierarchical orthology framework with improved functional annotations for eukaryotic, prokaryotic and viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:D286–D293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WB, Murali SC, Bandaranaike D, Hernandez B, Chao H, et al. 2016. Homalodisca vitripennis Genome Assembly 1.0. Ag Data Commons. doi: 10.15482/USDA.ADC/1409834. Accessed 2021-07-26. [DOI]

- Hyatt D, Chen G-L, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, et al. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- i5K Consortium 2013. The i5K initiative: advancing arthropod genomics for knowledge, human health, agriculture, and the environment. J Hered. 104:595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Yang M, Guo W, Wang X, Kang L.. 2012. Large-scale transcriptome analysis of retroelements in the migratory locust, Locusta migratoria. PLoS One. 7:e40532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, et al. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 30:1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer ELL.. 2004. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 338:1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta A, Suh A, Feschotte C.. 2017. Dynamics of genome size evolution in birds and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E1460–E1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA.. 2019. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. 37:540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. 2004. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL.. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 9:357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MD. 2019. GToTree: a user-friendly workflow for phylogenomics. Bioinformatics. 35:4162–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Zhao X, Li M, He K, Huang C, et al. 2019. Insect genomes: progress and challenges. Insect Mol Biol. 28:739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 34:3094–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R.. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25:1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W.. 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 30:923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Yuan J, Kolmogorov M, Shen MW, Chaisson M, et al. 2016. Assembly of long error-prone reads using de Bruijn graphs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 113:E8396–E8405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V, Golaconda Ramulu H, Drula E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B.. 2014. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:D490–D495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR.. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL.. 2004. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 20:2878–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicardi GC, Nardelli A, Mandrioli M.. 2015. Fast chromosomal evolution and karyotype instability: recurrent chromosomal rearrangements in the peach potato aphid Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Biol J Linn Soc. 116:519–529. [Google Scholar]

- Marçais G, Kingsford C.. 2011. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 27:764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers TC, Mugford ST, Hogenhout SA, Tripathi L.. 2020. Genome sequence of the banana Aphid, Pentalonia nigronervosa Coquerel (Hemiptera: Aphididae) and its symbionts. G3 (Bethesda). 10:4315–4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JP, McDonald BR, Moran NA.. 2009. Convergent evolution of metabolic roles in bacterial co-symbionts of insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:15394–15399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JP, Moran NA.. 2007. Parallel genomic evolution and metabolic interdependence in an ancient symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:19392–19397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng G, Li Y, Yang C, Liu S.. 2019. MitoZ: a toolkit for animal mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel P, Ng KL, Krogh A.. 2016. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat Commun. 7:11257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita RD, Vionette-Amaral RJ, Lowenberger C, Rivera-Pomar R, Monteiro FA, et al. 2015. Genome of Rhodnius prolixus, an insect vector of Chagas disease, reveals unique adaptations to hematophagy and parasite infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112:14936–14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran NA, Bennett GM.. 2014. The tiniest tiny genomes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 68:195–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran NA, Dale C, Dunbar H, Smith WA, Ochman H.. 2003. Intracellular symbionts of sharpshooters (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadellinae) form a distinct clade with a small genome. Environ Microbiol. 5:116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran NA, Tran P, Gerardo NM.. 2005. Symbiosis and insect diversification: an ancient symbiont of sap-feeding insects from the bacterial phylum Bacteroidetes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 71:8802–8810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandety RS, Kamita SG, Hammock BD, Falk BW.. 2013. Sequencing and de novo assembly of the transcriptome of the glassy-winged sharpshooter (Homalodisca vitripennis). PLoS One. 8:e81681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, et al. 2007. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 316:1718–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JM, Stajich J.. 2020. Funannotate v1.8.1: Eukaryotic genome annotation. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4054262. [DOI]

- Panfilio KA, Angelini DR.. 2018. By land, air, and sea: hemipteran diversity through the genomic lens. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 25:106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panfilio KA, Vargas Jentzsch IM, Benoit JB, Erezyilmaz D, Suzuki Y, et al. 2019. Molecular evolutionary trends and feeding ecology diversification in the Hemiptera, anchored by the milkweed bug genome. Genome Biol. 20:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW.. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25:1043–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascar J, Chandler CH.. 2018. A bioinformatics approach to identifying Wolbachia infections in arthropods. PeerJ. 6:e5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Armisén D, Gibbs RA, Hering L, Khila A, et al. 2019. Diversity and evolution of the transposable element repertoire in arthropods with particular reference to insects. BMC Evol. Biol. 19:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP.. 2010. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS One. 5:e9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranallo-Benavidez TR, Jaron KS, Schatz MC.. 2020. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 11:1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A.. 2014. Using the MEROPS database for proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors and substrates. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 48:1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Redak RA, Purcell AH, Lopes JRS.. 2004. The biology of xylem fluid–feeding insect vectors of Xylella fastidiosa and their relation to disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Control. 49:243–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Gibbs RA, Weinstock GM, Brown SJ, Denell R, et al. 2008. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature. 452:949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S, Murali SC.. 2015. Best practices in insect genome sequencing: what works and what doesn’t. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues ASB, Silva SE, Pina-Martins F, Loureiro J, Castro M, et al. 2016. Assessing genotype-phenotype associations in three dorsal colour morphs in the meadow spittlebug Philaenus spumarius (L.) (Hemiptera: Aphrophoridae) using genomic and transcriptomic resources. BMC Genet. 17:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EE, Backus EA.. 2014. Anterior foregut microbiota of the glassy-winged sharpshooter explored using deep 16S rRNA gene sequencing from individual insects. PLoS One. 9:e106215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld JA, Reeves D, Brugler MR, Narechania A, Simon S, et al. 2016. Genome assembly and geospatial phylogenomics of the bed bug Cimex lectularius. Nat Commun. 7:10164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemann T. barrnap: BAsic Rapid Ribosomal RNA Predictor. https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap.

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM.. 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 31:3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P.. 2013-2015. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. 2013-2015. http://www.repeatmasker.org.

- Sorensen JT, Gill RJ.. 1996. A range extension of Homalodisca coagulata (Hemiptera: Clypeorrhyncha: Cicadellidae) to Southern California. Pan-Pac Entomol. 72:160–161. [Google Scholar]

- Stajich J, Palmer J.. 2019. stajichlab/AAFTF: v0.2.3 release. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3437300. [DOI]

- Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I, Hayes A, Waack S, et al. 2006. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W435–W439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger DC, Sisterson MS, French R.. 2010. Population genetics of Homalodisca vitripennis reovirus validates timing and limited introduction to California of its invasive insect host, the glassy-winged sharpshooter. Virology. 407:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Ding J, Piednoël M, Schneeberger K.. 2018. findGSE: estimating genome size variation within human and Arabidopsis using k-mer frequencies. Bioinformatics. 34:550–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone EE, Cowden CC, Castle SJ.. 2017. De novo transcriptome assemblies of four xylem sap-feeding insects. Gigascience. 6:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Lomsadze A, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M.. 2008. Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Res. 18:1979–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triapitsyn SV, Phillips PA.. 2000. First Record of Gonatocerus triguttatus (Hymenoptera: Mymaridae) from eggs of Homalodisca coagulata (Homoptera: Cicadellidae) with notes on the distribution of the host. Florida Entomologist. 83:200. [Google Scholar]

- Turner WF, Pollard HN.. 1959. Life Histories and Behavior of Five Insect Vectors of Phony Peach Disease. U.S. Dep Agric Tech Bull. 1188. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Fang X, Yang P, Jiang X, Jiang F, et al. 2014. The locust genome provides insight into swarm formation and long-distance flight. Nat Commun. 5:2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L-G, Lam TT-Y, Xu S, Dai Z, Zhou L, et al. 2020. Treeio: an R package for phylogenetic tree input and output with richly annotated and associated data. Mol Biol Evol. 37:599–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch EW, Macias J, Bextine B.. 2015. Geographic patterns in the bacterial microbiome of the glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca vitripennis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Symbiosis. 66:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, et al. 2019. Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Soft. 4:1686. [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Daugherty SC, Van Aken SE, Pai GH, Watkins KL, et al. 2006. Metabolic complementarity and genomics of the dual bacterial symbiosis of sharpshooters. PLoS Biol. 4:e188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, He C, Fei Z, Zhang Y.. 2020. Chromosome-level genome assembly of the greenhouse whitefly (Trialeurodes vaporariorum Westwood). Mol Ecol Resour. 20:995–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J, Zhou X, Zhang C-X, Yu L-L, Fan H-W, et al. 2014. Genomes of the rice pest brown planthopper and its endosymbionts reveal complex complementary contributions for host adaptation. Genome Biol. 15:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G. 2020. Using ggtree to visualize data on tree-like structures. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 69:e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabalou S, Riegler M, Theodorakopoulou M, Stauffer C, Savakis C, et al. 2004. Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a means for insect pest population control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:15042–15045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Jiang F, Wang X, Yang P, Bao Y, et al. 2017. Genome sequence of the small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus. Gigascience. 6:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimin AV, Marçais G, Puiu D, Roberts M, Salzberg SL, et al. 2013. The MaSuRCA genome assembler. Bioinformatics. 29:2669–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The draft H. vitripennis Tulare genome assembly, annotation, and mitochondrial genome are deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JAGXCG000000000. The version described in this paper is version JAGXCG010000000. The raw sequence reads for the genome and RNA-Seq are available through BioProjects PRJNA717305 and PRJNA717315, respectively. The four MAG assemblies are available from BioProject PRJNA723626 and are deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession numbers JAGTUP000000000, JAGTUQ000000000, JAGTUR000000000, and JAGTUS000000000. Data analysis, assembly, and annotation-related scripts for this work are available on GitHub (https://github.com/stajichlab/GWSS_Genome) and archived in Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4891938) (Ettinger and Stajich 2021).

Supplementary material is available at G3 online.