Abstract

Objectives

Rates of age-associated severe maternal morbidity (SMM) have increased in Canada, and an association with neighbourhood income is well established. Our aim was to examine SMM trends according to neighbourhood material deprivation quintile, and to assess whether neighbourhood deprivation effects are moderated by maternal age.

Design, setting and participants

A population-based retrospective cohort study using linked administrative databases in Ontario, Canada. We included primiparous women with a live birth or stillbirth at ≥20 weeks’ gestational age.

Primary outcome

SMM from pregnancy onset to 42 days postpartum. We calculated SMM rate differences (RD) and rate ratios (RR) by neighbourhood material deprivation quintile for each of four 4-year cohorts from 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2018. Log-binomial multivariable regression adjusted for maternal age, demographic and pregnancy-related variables.

Results

There were 1 048 845 primiparous births during the study period. The overall rate of SMM was 18.0 per 1000 births. SMM rates were elevated for women living in areas with high material deprivation. In the final 4-year cohort, the RD between women living in high vs low deprivation neighbourhoods was 3.91 SMM cases per 1000 births (95% CI: 2.12 to 5.70). This was higher than the difference observed during the first 4-year cohort (RD 2.09, 95% CI: 0.62 to 3.56). SMM remained associated with neighbourhood material deprivation following multivariable adjustment in the pooled sample (RR 1.16, 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.21). There was no evidence of interaction with maternal age.

Conclusion

SMM rate increases were more pronounced for primiparous women living in neighbourhoods with high material deprivation compared with those living in low deprivation areas. This raises concerns of a widening social gap in maternal health disparities and highlights an opportunity to focus risk reduction efforts toward disadvantaged women during pregnancy and postpartum.

Keywords: epidemiology, obstetrics, perinatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data were from population linked administrative and health registries that capture all hospital births in Ontario, Canada.

Neighbourhood material deprivation was measured using the Ontario Marginalization Index, a comprehensive area-level measure based on census data developed using theoretical frameworks on marginalisation and deprivation.

Limiting our study to primiparous women enabled the evaluation of population severe maternal morbidity (SMM) trends and reduced confounding from previous births.

It was not possible to control for all covariates associated with SMM, including body mass index, comorbidities, and the use of assisted reproductive technology.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 4000 Canadian women survive a maternal ‘near-miss’—a life-threatening event associated with pregnancy.1 To characterise maternal near-misses in a standardised way, the WHO proposed the concept of severe maternal morbidity (SMM), a composite of conditions that represent end-organ dysfunction or states of heightened maternal mortality risk associated with pregnancy, birth or the postpartum period.2 3 Advances in the recognition and management of SMM have resulted in low maternal mortality rates in economically developed nations. Women living in high-income countries are now more likely to survive a life-threatening pregnancy condition and, correspondingly, the rates of SMM are 100-fold higher than the rates of maternal mortality in Canada.1 However, recent trends in Canada and other high-income countries show an increase in SMM rates coinciding with advancing maternal age and corresponding increases in pre-existing comorbidities and the use of assisted reproductive technology.4–9

The literature also shows persistent though complex associations between SMM and the social determinants of health. Low occupational class, Black ethnicity10 and non-private health insurance11 are all associated with higher risk of SMM in the USA. Canadian women who experience SMM are more likely to come from a low-income background, and to originate from an African or Caribbean country.4 6 12 A systematic review found evidence for effects of material dimensions of inequality on SMM risk, though it pointed out the need for further work on other dimensions and in elucidating effect mechanisms.13 Women of advanced maternal age may be more likely to come from more advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds and to have planned pregnancies.14–16 This suggests the possibility for effect modification, whereby the negative effects of advanced maternal age may be attenuated for women who come from more advantaged backgrounds, and exacerbated for women from disadvantaged backgrounds. The effects of maternal age and neighbourhood-level material deprivation may therefore interact, with the highest SMM risk among older women living in neighbourhoods with higher deprivation.

In this study, our first objective was to evaluate trends in SMM rates among primiparous women in Ontario by neighbourhood material deprivation quintile between 1 April 2002 and 31 March 2018. Our second objective was to determine if maternal age moderates the effect of neighbourhood material deprivation. We hypothesised that SMM rates would increase disproportionately over time among women living in neighbourhoods with high material deprivation. We further hypothesised that the highest risk of SMM would be among women of advanced maternal age living in neighbourhoods with the highest material deprivation.

Methods

This population-based retrospective cohort study used linked administrative datasets for Ontario, held at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences). ICES is an independent, non-profit research institute funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. As a prescribed entity under Ontario’s privacy legislation, ICES is authorised to collect and use healthcare data for the purposes of health system analysis, evaluation and decision support. Secure access to these data is governed by policies and procedures that are approved by the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. The use of data in this project was authorised under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. We followed the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected Data guidelines for reporting this study.17

Patient and public involvement

There was no direct patient or public involvement in this study.

Study population and data sources

The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) was used to capture all hospital admissions for birth and link to newborn records using the ICES-derived MOMBABY dataset. We included primiparous women aged 10–55 years who had a hospital birth in Ontario and were enrolled in the province’s universal health insurance programme (OHIP). We identified the first live birth or stillbirth delivery at a gestational age of ≥20 weeks. We used gestational age at birth to calculate pregnancy onset. Women were included if the onset of their first pregnancy was on or after 1 April 2002 and the corresponding birth occurred on or before 17 February 2018—allowing 42 days of postpartum follow-up through the study end date of 31 March 2018. Women who had a previous birth within 14 years prior to the index date were excluded. We linked these data with the Registered Persons Database, DAD and OHIP Claims Database to identify exposures and outcomes of interest. To identify women who had recently immigrated to Ontario, we used the Ontario portion of the federal Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Permanent Resident Database. For neighbourhood material deprivation, we used the 2001 and 2006 Canadian Census, and Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-MARG).18 These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES and are shown in online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjopen-2020-046174supp001.pdf (139.5KB, pdf)

Main outcome

The main outcome was a composite of medical conditions and interventions that comprise SMM. Cases of SMM were identified using diagnosis and procedural codes (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision and Canadian Classification of Health Interventions, respectively) within the DAD database.15 19–21 The DAD data have been validated and shown to accurately reflect the information in medical records.21 22 The composite SMM outcome included: (1) causes of direct obstetric death and conditions related to these (antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum haemorrhage; hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and eclampsia; puerperal sepsis; uterine rupture; obstetric embolus); (2) severe organ system dysfunction (cardiac arrest, failure, or arrhythmia; renal or hepatic failure; coagulation defect; thromboembolism; respiratory failure; coma or non-eclamptic seizure; psychosis); (3) procedures or interventions accompanying life-threatening conditions or health states (caesarean or postpartum hysterectomy; pelvic vessel ligation; surgical repair of bowel, bladder, or urethra; endotracheal or tracheostomy ventilation; dialysis; blood transfusion in the context of severe blood loss); and (4) deaths that were ill-defined or sudden, as these could not reliably be classified as non-obstetric deaths. Online supplemental appendix 1 shows the list of SMM indicators for this study. We specified a binary SMM outcome variable for the presence of one or more indicators occurring from the onset of pregnancy up to and including 42 days after birth.

Exposures and covariates

Our main exposure of interest was neighbourhood material deprivation quintile from the ON-MARG. ON-MARG is the Ontario-specific version of the Canadian Marginalization Index (CAN-MARG).23 The index was developed based on theoretical frameworks of marginalisation and deprivation, and derived empirically using principal component analysis of Canadian Census variables.18 23 The material deprivation dimension is comprised of the following census measures, each expressed as a proportion: population aged ≥20 without secondary school graduation, single-parent families, households receiving government transfer payments, population aged ≥15 who are unemployed, population living below the low income cut-off (adjusted for community size, household size and inflation).18 The geographical unit of aggregation is dissemination areas, which average 400–700 people and cover the entirety of Canadian territory.24 ON-MARG can be operationalised as a standardised interval scale based on factor loadings from the principal component analysis, or as quintiles each representing 20% of dissemination areas.18 23 We modelled this exposure as quintiles, with quintile 1 representing neighbourhoods with the lowest material deprivation, and quintile 5 representing neighbourhoods with the highest deprivation.18 23 ON-MARG has been used to demonstrate inequalities in various health measures and is stable over time.25–27 We used the 2001 material deprivation index for births between years 2002 and 2003, and the 2006 index for years 2004–2018. The change from mandatory census reporting to the voluntary National Household Survey and resulting data quality concerns meant that the 2011 index was comprised from alternate data sources.28 We used the 2006 version for all years after 2004 to avoid operationalising this variable differently between study years.

We included maternal age at birth, categorised in 5-year bands. We adjusted for rural setting using the 2004 and 2008 Rurality Index of Ontario (RIO).29 We used the 2004 RIO index for pregnancies between years 2002 and 2006, and the 2008 index for pregnancies between years 2007 and 2018. We adjusted for number of years since immigration using data from the IRCC. Additional demographic and pregnancy-related variables included delivery mode and multiple gestations. For multiple gestation pregnancies, delivery mode was specified based on the highest level of intervention: unassisted vaginal birth of all fetuses (lowest), forceps or vacuum assisted vaginal birth of one or more fetuses, vaginal breech birth of one or more fetuses and caesarean birth of one or more fetuses (highest). We examined SMM rates by gestational age at birth, induction of labour and the use of epidural analgesia; however, these variables were not adjusted for in the multivariable models.

Statistical analysis

We summarised baseline characteristics and SMM rates overall for the study population. Due to low birth counts for ages 10–14 years, we collapsed these into an age <20 years group for analysis. We plotted SMM rates by year for the whole study population, and then to evaluate changes over time, we divided the population into four, 4-year cohorts based on pregnancy onset: 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2006 (cohort 1); 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2010 (cohort 2); 1 April 2010 to 31 March 2014 (cohort 3); and 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2018 (cohort 4). To address our first objective, we calculated average annual SMM rates for each 4-year cohort by neighbourhood material deprivation quintile. Within each cohort, we estimated unadjusted absolute rate differences (RD) and rate ratios (RR) with 95% CI comparing women in quintile 5 (highest deprivation) with women in quintile 1 (lowest deprivation).

Our second objective was to evaluate the effect of neighbourhood material deprivation, adjusting for covariates and testing for interaction with maternal age for the overall study population. We constructed multivariable log-binomial regression models. We initially fit a model with neighbourhood material deprivation, adjusting only for year of pregnancy onset (model 1). We then added maternal age (model 2), followed by demographic and pregnancy-related covariates, immigration status, and rurality (model 3). We tested for interaction between material deprivation and maternal age using a cross product term. We did not adjust for stillbirth or gestational age at birth, as these variables are considered colliders rather than true confounders of outcomes associated with SMM.30 We did not include induction of labour or epidural analgesia, as these interventions are associated with clinical decisions surrounding birth rather than SMM risk factors. We excluded women with missing information for neighbourhood material deprivation from the multivariable analysis, as these women represented less than 2% of the study population (n=17 130).

We performed two additional analyses evaluating SMM rate trends (RD and RR) over the study period, comparing the 4-year average annual rates during cohort 4 to cohort 1 separately by maternal age and by neighbourhood material deprivation quintile. We also examined the 4-year average rates of SMM excluding cases defined by HIV disease. This was done in reference to recently proposed changes to the Canadian SMM composite indicator excluding chronic, asymptomatic HIV disease.12 31 Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (V.7.15, SAS Institute Inc) and STATA (V.13, StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

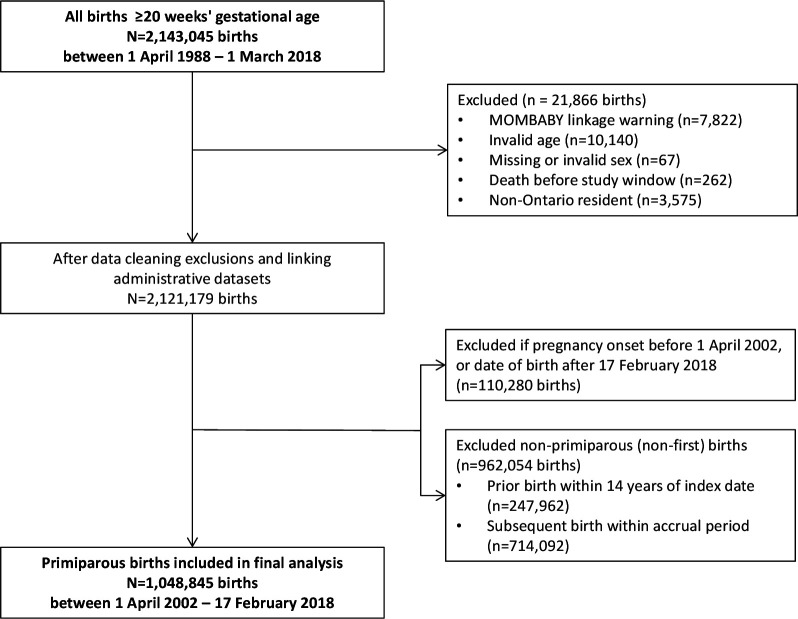

There were 2 143 045 hospital-based births in Ontario between 1 April 2002 and 17 February 2018, of which 1 048 845 were primiparous births included in the study (figure 1). The overall SMM rate across the study period was 18.0 per 1000 births, and increased from 16.7 per 1000 births in 2002–2003 (95% CI: 15.6 to 17.9) to 23.0 per 1000 births in 2017–2018 (95% CI: 21.2 to 25.0, online supplemental figure 1). Baseline characteristics and SMM case number and rate for each characteristic are presented in table 1. SMM rates were higher at the extremes of maternal age, and among women living in neighbourhoods with the highest material deprivation.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion/exclusion flow chart, primiparous births.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population, 2002–2018

| Variable | Number of births | Percent | Number of SMM cases | SMM rate per 1000 births |

| Overall study population | 1 048 845 | 100 | 18 880 | 18.00 |

| Maternal age at birth, years | ||||

| 10–14 | 1330 | 0.1 | 35 | 26.32 |

| 15–19 | 72 579 | 6.9 | 1291 | 17.79 |

| 20–24 | 178 074 | 17.0 | 2684 | 15.07 |

| 25–29 | 342 003 | 32.6 | 5324 | 15.57 |

| 30–34 | 305 898 | 29.2 | 5653 | 18.48 |

| 35–39 | 123 698 | 11.8 | 3017 | 24.39 |

| ≥40 | 25 263 | 2.4 | 876 | 34.68 |

| Gestational age at birth, weeks | ||||

| 20–23 | 2751 | 0.3 | 147 | 53.44 |

| 24–27 | 4158 | 0.4 | 306 | 73.59 |

| 28–33 | 17 688 | 1.7 | 1104 | 62.42 |

| 34–36 | 59 040 | 5.6 | 1966 | 33.30 |

| 37–41 | 961 322 | 91.7 | 15 278 | 15.89 |

| ≥42 | 3886 | 0.4 | 79 | 20.33 |

| Induced labour | 275 262 | 26.2 | 5836 | 21.20 |

| Epidural | 655 107 | 62.5 | 10 713 | 16.35 |

| Delivery mode | ||||

| Vaginal unassisted | 579 814 | 55.3 | 6386 | 11.01 |

| Vaginal assisted | 156 383 | 14.9 | 2724 | 17.42 |

| Vaginal breech | 2328 | 0.2 | 95 | 40.81 |

| Caesarean | 310 320 | 29.6 | 9675 | 31.18 |

| Multiple gestations | 20 850 | 2.0 | 1137 | 54.53 |

| Stillbirth | 3645 | 0.3 | 199 | 54.60 |

| Rurality | ||||

| Urban | 993 282 | 94.7 | 17 814 | 17.93 |

| Rural | 55 563 | 5.3 | 1066 | 19.19 |

| Immigration status | ||||

| Non-immigrant/before 1985 | 739 252 | 70.5 | 13 222 | 17.89 |

| Immigrated >10 years | 62 381 | 5.9 | 1165 | 18.68 |

| Immigrated 5–10 years | 62 090 | 5.9 | 1249 | 20.12 |

| Immigrated <5 years | 185 122 | 17.7 | 3244 | 17.52 |

| Neighbourhood material deprivation | ||||

| Quintile 1 (least deprived) | 237 877 | 22.7 | 4183 | 17.58 |

| Quintile 2 | 186 550 | 17.8 | 3112 | 16.68 |

| Quintile 3 | 189 575 | 18.1 | 3327 | 17.55 |

| Quintile 4 | 191 376 | 18.2 | 3423 | 17.89 |

| Quintile 5 (most deprived) | 226 337 | 21.6 | 4397 | 19.43 |

| Missing | 17 130 | 1.6 | 438 | 25.57 |

N=1 048 845 births.

bmjopen-2020-046174supp002.pdf (907.6KB, pdf)

Table 2 presents SMM rates by material deprivation quintile for the pooled study sample (2002–2018) and each of the four 4-year cohorts. The RD was 2.09 cases per 1000 births (95% CI: 0.62 to 3.56), corresponding with an RR of 1.13 (95% CI: 1.04 to 1.23) comparing women in quintile 5 with women in quintile 1 during the first 4-year cohort. This increased to an RD of 3.91 cases per 1000 births (95% CI: 2.12 to 5.70) and RR of 1.21 (95% CI: 1.11 to 1.32) in the final 4-year cohort of the study period. Average annual SMM rates increased between cohort 1 and cohort 4 for women aged 30–34, and ≥40 years (online supplemental table 1 and online supplemental figure 2). For the latter group, the absolute increase was 14.69 cases per 1000 births (95% CI: 7.96 to 21.43, online supplemental table 1). SMM rates increased over time for women in each quintile of neighbourhood deprivation, and this increase was most pronounced for women in the highest quintile of neighbourhood deprivation (RD 4.19 cases per 1000 births 95% CI: 4.13 to 4.24, online supplemental table 1).

Table 2.

Four-year average SMM rates per 1000 births for neighbourhood material deprivation quintiles, by pooled sample (2002–2018) and by study period cohort

| Cohort* | SMM rates by material deprivation quintile | Q5 versus Q1 | |||||

| Q1 (least) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 (most) | Rate difference (95% CI) | Rate ratio (95% CI) | |

| Pooled | 17.58 | 16.68 | 17.55 | 17.89 | 19.43 | 1.84 (1.82 to 1.87)*** | 1.10 (1.10 to 1.11)*** |

| 1 | 16.05 | 16.36 | 17.46 | 16.49 | 18.14 | 2.09 (0.62 to 3.56)** | 1.13 (1.04 to 1.23)** |

| 2 | 16.58 | 15.97 | 15.73 | 16.37 | 17.32 | 0.75 (−0.70 to 2.20) | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.14) |

| 3 | 19.36 | 16.17 | 18.34 | 19.19 | 20.78 | 1.41 (−0.20 to 3.02) | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) |

| 4 | 18.41 | 18.52 | 18.99 | 20.18 | 22.32 | 3.91 (2.12 to 5.70)*** | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.32)*** |

**p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

*Cohort 1: 1 April 2002 to 31 March 2006; cohort 2: 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2010; cohort 3: 1 April 2010 to 31 March 2014; cohort 4: 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2018.

SMM, severe maternal morbidity.

bmjopen-2020-046174supp003.pdf (54.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046174supp004.pdf (884.6KB, pdf)

In the multivariable regression analysis for the overall study population, women living in neighbourhoods with the highest material deprivation had higher rates of SMM compared with those in neighbourhoods with the lowest after adjusting for pregnancy year (RR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.16, table 3). Full adjustment for age, demographics, pregnancy-related variables and rurality had minimal effect on the association between material deprivation and SMM rates (adjusted RR: 1.16, 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.21, table 3). The association between age and SMM persisted in the fully adjusted model, with higher risk for women<20 and ≥30 years of age. We did not find evidence of statistical interaction between maternal age and neighbourhood material deprivation quintile.

Table 3.

Neighbourhood material deprivation and risk of severe maternal morbidity: adjusted multivariable models, RR (95% CI)

| Variable | Model 1* | Model 2† | Model 3‡ |

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| <20 | 1.05 (0.99 to 1.12) | 1.20 (1.13 to 1.28) | |

| 20–24 | 0.95 (0.90 to 0.99) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | |

| 25–29 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | |

| 30–34 | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.23) | 1.10 (1.06 to 1.15) | |

| 35–39 | 1.56 (1.49 to 1.63) | 1.34 (1.28 to 1.40) | |

| ≥40 | 2.21 (2.06 to 2.37) | 1.73 (1.61 to 1.86) | |

| Material deprivation | |||

| Quintile 1 (least) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Quintile 2 | 0.95 (0.91 to 0.99) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.01) |

| Quintile 3 | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 1.04 (0.99 to 1.08) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.07) |

| Quintile 4 | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.07) | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.11) |

| Quintile 5 (most) | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 1.17 (1.12 to 1.22) | 1.16 (1.11 to 1.21) |

N=1 031 715 births.

*Adjusted for pregnancy year.

†Adjusted for pregnancy year, age.

‡Adjusted for pregnancy year, age, delivery mode, multiple gestations, immigration status, rurality.

Discussion

Main findings

This study demonstrated an association between neighbourhood material deprivation and SMM among primiparous women in Ontario from 2002 to 2018. Rates of SMM increased across all material deprivation quintiles, and we found some evidence that women in the highest deprivation quintile experienced a higher magnitude SMM rate increase over the 16-year study period compared with women in the lowest deprivation quintile. This finding suggests a possible widening of the gap between women living in the most and least deprived neighbourhoods.

Strengths/limitations

The current study was a population-based analysis of all primiparous hospital births at ≥20 weeks’ gestational age in Ontario. Hospital births account for over 98% of births in the province. We used a measure of neighbourhood marginalisation that includes income along with other measures of material resources, and that is stable across time and different health outcomes.23 25 Our study nonetheless had some limitations. We were unable to account for births prior to 20 weeks’ gestation or births that occurred outside of the province. Our measure of SMM was based on validated perinatal health data for Canada.15 21 A revision of the Canadian SMM composite was recently developed which resolves issues surrounding the inclusion of some pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome measures, as well as the exclusion of HIV infection—a condition that is unlikely to represent SMM when asymptomatic.12 31 We elected to use the former SMM composite for comparison with the previous literature, recognising this may complicate direct comparison with recent Canadian studies.4 6 12 31 The proportion of women with SMM defined by HIV disease was around 2% for each of the 4-year cohorts, and thus we do not believe these cases substantively altered the results of this study. Information on immigrants arriving prior to 1985 is not captured in the IRCC Permanent Resident Database, and the database does not identify immigrants who landed in other provinces and subsequently moved to Ontario. Although we used a measure of neighbourhood material deprivation developed for Ontario using Canadian Census elements,28 the ON-MARG Index does not include individual-level indicators of marginalisation or socioeconomic status. Important social determinants may differ among individuals living in areas characterised by similar measures of neighbourhood deprivation, and it is not possible to elucidate the causal pathways that link social disadvantage to poor health outcomes without incorporating such factors.32 33 Finally, pre-pregnancy comorbidities, obesity, and the use of assisted reproductive technology, contribute to higher SMM rates and may partially explain SMM trends.8 9 34 We were unable to account for these factors. Obstetric comorbidity indices have been developed for risk prediction and adjustment in clinical research.35 36 We did not use an obstetric comorbidity index in our adjusted analysis as some index indicators represent SMM outcomes themselves, or are mediators of SMM outcomes. In addition, our aim was to examine population SMM trends rather than individual clinical risk factors.

Interpretation

The present study contributes to our understanding of the association between neighbourhood marginalisation and SMM and provides preliminary evidence of a possible widening of this health disparity over time in Ontario. The association between neighbourhood-level measures of inequality and risk of SMM has been demonstrated previously in several high-income countries.6 9 11 13 37–41 Notably in Canada, Aoyama et al reported a rise in SMM linked to the relative increase in maternal age and found a significant association between SMM and neighbourhood income quintile.4 Our study confirms this finding using a measure that encompasses income along with additional measures of neighbourhood material deprivation. Moreover, we extend the current understanding of this association by providing evidence for a possible disproportionate rise in SMM risk experienced by women living in marginalised neighbourhoods over time. We interpret this last finding with caution, as our study showed significant RD by neighbourhood marginalisation only during the first and final 4-year cohorts of the 16-year study period. SMM risks have been demonstrated among other social determinants of health; for example, lower occupational class, Black ethnicity10 and non-private health insurance11 are associated with higher risk of SMM in the USA. Interaction between socioeconomic indicators—including ethnicity, education and poverty—likely contribute to the social gradient of risk such that the protective effects afforded by higher education and income do not fully ameliorate racial disparities in SMM.38 Our study showed an association between neighbourhood deprivation and SMM suggesting the effects of marginalisation persist even in the context of universal healthcare. This is a consistent finding across countries that have similar publicly funded healthcare systems.41–43 The factors contributing to social inequality are myriad; ethnicity and country of origin, rurality and access to care, income, material resources, education and psychosocial supports all have worrisome associations with maternal reproductive health risks.6 10–12 38 41–47 How these factors contribute to widening health gaps, and what interventions may attenuate their effects will be imperative lines of inquiry going forward as the global challenge to lower SMM continues.

Conclusion

Ontario women living in areas with higher neighbourhood material deprivation experienced the highest risk of SMM, and this association was not fully explained by maternal age. Additionally, women living in high-deprivation neighbourhoods may have experienced a disproportionate increase in the risk of SMM over time. Future work must focus on addressing the widening social gap in maternal health disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Josie Chundamala, Scientific Grant Editor funded by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Mount Sinai Hospital, for assistance editing and preparing this manuscript for submission.

Footnotes

Twitter: @5nelgrove, @LauraCRosella

Contributors: JWS, DBF, KEM and LCR contributed to the overall conception of the study. JWS, ML, LR, DBF and LCR contributed to study design and protocol. TW had full access to data used in the study. JWS, TW and LCR take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. JWS wrote the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to the data analysis interpretation, and manuscript editing and revising for this project. All authors approve the final submitted version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: John Snelgrove received funding for this project through an internal grant from the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University of Toronto, and Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mount Sinai Hospital. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. This study was completed at the ICES University of Toronto site and ICES Western site—where core funding is provided by the Academic Medical Organisation of Southwestern Ontario, the Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, and the Lawson Health Research Institute. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, and by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

ICES is a prescribed entity under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act. Section 45 authorises ICES to collect personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of analysis or compiling statistical information with respect to the management of, evaluation or monitoring of, the allocation of resources to or planning for all or part of the health system. Projects conducted under section 45, by definition, do not require review by a Research Ethics Board. This project was conducted under section 45, and approved by ICES’ Privacy and Legal Office.

References

- 1.Public Health Agency of Canada . Perinatal health indicators for Canada, 2017 edition. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications: the WHO near-miss approach for maternal health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pattinson R, Say L, Souza JP, et al. WHO maternal death and near-miss classifications. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:734. 10.2471/BLT.09.071001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoyama K, Pinto R, Ray JG, et al. Association of maternal age with severe maternal morbidity and mortality in Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e199875. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoyama K, Ray JG, Pinto R, et al. Temporal variations in incidence and outcomes of critical illness among pregnant and postpartum women in Canada: a population-based observational study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:631–40. 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray JG, Park AL, Dzakpasu S, et al. Prevalence of severe maternal morbidity and factors associated with maternal mortality in Ontario, Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e184571. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheen J-J, Wright JD, Goffman D, et al. Maternal age and risk for adverse outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:390.e1–390.e15. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dayan N, Fell DB, Guo Y, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in women with high BMI in IVF and unassisted singleton pregnancies. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1548–56. 10.1093/humrep/dey224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayan N, Joseph KS, Fell DB, et al. Infertility treatment and risk of severe maternal morbidity: a propensity score-matched cohort study. CMAJ 2019;191:E118–27. 10.1503/cmaj.181124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayem G, Kurinczuk J, Lewis G, et al. Risk factors for progression from severe maternal morbidity to death: a national cohort study. PLoS One 2011;6:e29077. 10.1371/journal.pone.0029077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guglielminotti J, Landau R, Wong CA, et al. Patient-, hospital-, and Neighborhood-Level factors associated with severe maternal morbidity during childbirth: a cross-sectional study in New York state 2013-2014. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:82–91. 10.1007/s10995-018-2596-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urquia ML, Wanigaratne S, Ray JG, et al. Severe maternal morbidity associated with maternal birthplace: a population-based register study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2017;39:978–87. 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang E, Glazer KB, Howell EA, et al. Social determinants of pregnancy-related mortality and morbidity in the United States: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:896–915. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goisis A, Schneider DC, Myrskylä M. The reversing association between advanced maternal age and child cognitive ability: evidence from three UK birth cohorts. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:850–9. 10.1093/ije/dyw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph KS, Liu S, Rouleau J, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 2003 to 2007: surveillance using routine hospitalization data and ICD-10CA codes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2010;32:837–46. 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34655-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldenström U, Cnattingius S, Norman M, et al. Advanced maternal age and stillbirth risk in nulliparous and parous women. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:355–62. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational Routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matheson FI. Ontario marginalization index: user guide. 2006. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Institute for Health Information . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision. ICD-10CA, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Canadian classification of health interventions. Ottawa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph KS, Fahey J, Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System . Validation of perinatal data in the discharge Abstract database of the Canadian Institute for health information. Chronic Dis Can 2009;29:96–101. 10.24095/hpcdp.29.3.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) . Data quality study of the 2015−2016 discharge Abstract database: a focus on hospital harm. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matheson FI, Dunn JR, Smith KLW, et al. Development of the Canadian marginalization index: a new tool for the study of inequality. Can J Public Health 2012;103:S12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Canada, Government of Canada . Census dictionary 2016, Dissemination areas, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moin JS, Moineddin R, Upshur REG. Measuring the association between marginalization and multimorbidity in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. J Comorb 2018;8:2235042X1881493. 10.1177/2235042X18814939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urquia ML, Frank JW, Glazier RH, et al. Neighborhood context and infant birthweight among recent immigrant mothers: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health 2009;99:285–93. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White HL, Matheson FI, Moineddin R, et al. Neighbourhood deprivation and regional inequalities in self-reported health among Canadians: are we equally at risk? Health Place 2011;17:361–9. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matheson FL. 2011 Ontario marginalization index: user guide. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: An empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Rev 2000;67:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:1062–8. 10.1093/aje/kwr230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzakpasu S, Deb-Rinker P, Arbour L, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada: temporal trends and regional variations, 2003-2016. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:1589–98. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise. operationalise and measure them? Social Science & Medicine 2002;55:125–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cottrell EK, Hendricks M, Dambrun K, et al. Comparison of community-level and patient-level social risk data in a network of community health centers. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2016852. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leonard SA, Main EK, Carmichael SL. The contribution of maternal characteristics and cesarean delivery to an increasing trend of severe maternal morbidity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:16. 10.1186/s12884-018-2169-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:957–65. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a603bb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aoyama K, D'Souza R, Inada E, et al. Measurement properties of comorbidity indices in maternal health research: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:372. 10.1186/s12884-017-1558-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amjad S, Chandra S, Osornio-Vargas A, et al. Maternal area of residence, socioeconomic status, and risk of adverse maternal and birth outcomes in adolescent mothers. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:1752–9. 10.1016/j.jogc.2019.02.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howland RE, Angley M, Won SH, et al. Determinants of severe maternal morbidity and its racial/ethnic disparities in New York City, 2008-2012. Matern Child Health J 2019;23:346–55. 10.1007/s10995-018-2682-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton BA, Jane MacDonald E, Stanley J, et al. Preventability review of severe maternal morbidity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019;98:515–22. 10.1111/aogs.13526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lepine S, Lawton B, Geller S, et al. Severe maternal morbidity due to sepsis: the burden and preventability of disease in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;58:648–53. 10.1111/ajo.12787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindquist A, Noor N, Sullivan E, et al. The impact of socioeconomic position on severe maternal morbidity outcomes among women in Australia: a national case-control study. BJOG 2015;122:1601–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwart JJ, Richters JM, Öry F, et al. Severe maternal morbidity during pregnancy, delivery and puerperium in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based study of 371,000 pregnancies. BJOG 2008;115:842–50. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knight M, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, et al. Inequalities in maternal health: national cohort study of ethnic variation in severe maternal morbidities. BMJ 2009;338:b542. 10.1136/bmj.b542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louis JM, Menard MK, Gee RE. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:690–4. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metcalfe A, Wick J, Ronksley P. Racial disparities in comorbidity and severe maternal morbidity/mortality in the United States: an analysis of temporal trends. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97:89–96. 10.1111/aogs.13245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson AL, Baskind NE, Karuppusami R, et al. Effect of deprivation on in vitro fertilisation outcome: a cohort study. BJOG 2020;127:458–65. 10.1111/1471-0528.16012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urquia ML, Glazier RH, Mortensen L, et al. Severe maternal morbidity associated with maternal birthplace in three high-immigration settings. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:620–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cku230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046174supp001.pdf (139.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046174supp002.pdf (907.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046174supp003.pdf (54.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046174supp004.pdf (884.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.