Abstract

Research question

How do infertility patients, endometriosis patients and health-care providers rate virtual care as an alternative to physical consultations during the first lockdown of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in the Netherlands, and how does this influence quality of life and quality of care?

Design

Infertility patients and endometriosis patients from a university hospital and members of national patient organizations, as well as healthcare providers in infertility and endometriosis care, were asked to participate between May and October 2020. The distributed online questionnaires consisted of an appraisal of virtual care and an assessment of fertility-related quality of life (FertiQol) and patient-centredness of endometriosis care (ENDOCARE).

Results

Questionnaires were returned by 330 infertility patients, 181 endometriosis patients and 101 healthcare providers. Of these, 75.9% of infertility patients, 64.8% of endometriosis patients and 80% of healthcare providers rated telephone consultations as a good alternative to physical consultations during the COVID-19-pandemic. Only 21.3%, 14.8% and 19.2% of the three groups rated telephone consultations as a good replacement for physical consultations in the future. A total of 76.6% and 35.9% of the infertility and endometriosis patients reported increased levels of stress during the pandemic. Infertility patients scored lower on the FertiQol, while the ENDOCARE results care seem comparable to the reference population.

Conclusions

Virtual care seems to be a good alternative for infertility and endometriosis patients in circumstances where physical consultations are not possible. Self-reported stress is especially high in infertility patients during the COVID-19-pandemic. Healthcare providers should aim to improve their patients’ ability to cope.

Key words: COVID-19, EHealth, Endometriosis, Infertility, Telemedicine, Virtual care

Introduction

The global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to a significant increase of pressure on healthcare systems all over the world. In the spring of 2020 all elective care and other ‘non-essential’ medical care was largely restricted or even shut down during the lockdown in the Netherlands in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to focus all resources and healthcare providers on COVID-19 care. For infertility patients and endometriosis patients, this first lockdown period resulted in a temporary cancellation of physical appointments, elective surgery and assisted reproductive technology (ART) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands.

In order to maintain continuity of care for both patient groups during the first COVID-19 lockdown, virtual care options such as telephone consultations and video consultations were quickly implemented in most hospitals throughout the Netherlands. Telephone consultations were already being used prior to the pandemic, mainly to communicate the results of diagnostic tests. Video consultations were not widely used in fertility and endometriosis care. With the use of these virtual care alternatives, healthcare providers were able to replace at least a proportion of the cancelled physical appointments in outpatient clinics, thus providing continuity in fertility and endometriosis care.

Under normal circumstances, infertility patients already experience high levels of stress, as well as a high sense of urgency to obtain treatment ( Aarts et al., 2011; Boivin et al., 2011). In addition, patients undergoing fertility treatments show higher levels of depression in comparison to the general population (Massarotti et al., 2019; Volgsten et al., 2008). The turbulent period of the first COVID-19 lockdown, with the temporary care restrictions resulting in cancellation of fertility treatments, might have led to additional stress and had a negative impact on the patients’ quality of life.

For patients with a chronic disease, such as endometriosis, continuity of care and more specifically the patient-centredness of the healthcare provided are very important as they are possibly associated with health-related quality of life (Apers et al., 2018). Patient-centred care is a method of providing care to patients while taking into account ‘the preferences, needs and values of the individual patient’ (Geukens et al., 2018; WHO, 2006). The cancellation of physical appointments, elective surgeries and fertility treatments during the COVID-19 lockdown could have a negative impact on the perceived quality of endometriosis care as patients might experience less support from their healthcare providers accompanied by an increase in waiting lists for consultations, surgery and ART.

The aim of this study was to evaluate patient and healthcare provider experiences of the alternative virtual care consultations and to investigate the impact of the restrictive measures and the shutdown of regular care during the COVID-19 pandemic on fertility-related quality of life and quality of endometriosis care.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional cohort study was performed in the Netherlands between March 2020 and October 2020. For this study three groups of participants were approached: (1) infertility patients, (2) women with endometriosis and (3) healthcare providers in the field of fertility and/or endometriosis in the Netherlands. In the Netherlands it is very common for gynaecologists to treat both endometriosis and infertility patients. As infertility patients often present with the urgent problem of wishing to conceive and endometriosis patients have complaints and worries of a more chronic nature, both groups can give a unique insight in both current and chronic care while the patients are visiting the same outpatient clinic. The healthcare providers were included in this study to investigate whether patients and professionals shared the same views on virtual care.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional review board of Amsterdam UMC for the two respective locations with their own medical ethical review committee (location AMC: reference no. 20.236, approved 7 May 2020; location VUmc: reference no. 2020.264, approved 19 May 2020).

Patient recruitment

To maximize the response, infertility and endometriosis patients were recruited by both Amsterdam UMC, a Dutch university hospital, and by their respective national patient organizations, FREYA (www.freya.nl) and De Endometriose Stichting (www.endometriose.nl). Patients from the university hospital were approached by e-mail when they had an appointment scheduled or were enrolled on a waiting list for ART or elective surgery in Amsterdam UMC between March 2020 and June 2020. Members of both patient organizations were approached via social media, newsletters and blogposts on the websites of the respective patient organizations. Healthcare providers were contacted through the Dutch Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (NVOG; www.nvog.nl) as well as the Dutch Society of Fertility Physicians (VVF; www.fertiliteitsartsen.nl). Due to the recruitment via social media, it was not possible to identify unique patients eligible for inclusion. A response rate could therefore not be calculated for the participants from the patients’ organizations.

The inclusion criteria for the infertility patients were (i) age ≥18 years, and (ii) women with infertility who were being treated at the Department of Reproductive Medicine of Amsterdam UMC or women who had joined the online network of the national patient organization for infertility. The inclusion criteria for endometriosis patients were (i) age ≥18 years, and (ii) a self-reported endometriosis diagnosis and a member of the national patient organization for endometriosis or receiving treatment at the Endometriosis Centre of Amsterdam UMC. For both groups of patients the exclusion criteria were: (i) age <18 years old, or (ii) an inability to read and write in the Dutch language. Healthcare providers were included if they were a member of the NVOG or the VVF and routinely treated women with infertility and/or endometriosis.

Questionnaires

Three different online questionnaires were developed for infertility patients, endometriosis patients and healthcare providers respectively. The questionnaires were developed in collaboration with the national patient organizations for infertility and endometriosis respectively: FREYA and De Endometriose Stichting. The questionnaires for infertility patients and endometriosis patients were distributed between May 2020 and July 2020. The questionnaire for healthcare providers was distributed between August 2020 and October 2020.

The questionnaires for infertility patients consisted of (i) a demographics and background section, (ii) a section on the assessment of virtual care and stress, and (iii) the Dutch fertility-related quality of life questionnaire (FertiQol). The questionnaires for endometriosis patients consisted of (i) a demographics and background section, (ii) a section on the assessment of virtual care and stress, and (iii) the patient-centredness of endometriosis care (ENDOCARE) questionnaire (ECQ).

The questionnaire on the assessment of virtual care and stress contained questions on changes in appointments during COVID-19, experience with the different modalities used to alter appointments and care (telephone and video consultations), communication and information during COVID-19, treatment during COVID-19, dealing with change and experiencing stress (Supplementary information).

FertiQol is a validated questionnaire evaluating the fertility-related quality of life of infertility patients. It consists of 36 items identifying core quality of life, treatment quality of life and overall quality of life (Aarts et al., 2011; Boivin et al., 2011). The FertiQoL questionnaire covers six different subdomains: (i) mind–body, (ii) relational, (iii) social, (iv) emotional, (v) environment, and (vi) tolerability (Table 1 ). Likert scales (0–4) are used to answer the FertiQoL questions, and the outcomes are transformed to a scale ranging from 0 to 100 for all individual subdomains (Boivin et al., 2011). A reference population obtained from Aarts and colleagues was used for a comparison of FertiQoL scores during the COVID-19 pandemic with FertiQoL scores obtained before the pandemic in the Dutch population (Aarts et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Examples of questions by FertiQoL domain

| Domain | Example |

|---|---|

| Mind–body | Do you feel drained or worn out because of your fertility problems? |

| Relational | Have fertility problems had a negative impact on your relationship with your partner? |

| Social | Are you socially isolated because of fertility problems? |

| Emotional | Do you feel sad and depressed about your fertility problems? |

| Environment | Are you satisfied with the quality of services available to you to address your emotional needs? |

| Tolerability | Are you bothered by the effect of treatment on your daily or work related activities? |

The ECQ is a validated questionnaire evaluating the patient-centredness of endometriosis care (Dancet et al., 2011, Dancet et al., 2012). It contains 38 aspects that are assessed using a 4-point Likert scale. Both performance and the importance of the care aspects are rated. The 38 aspects can be divided into 10 categories of patient-centred care: (i) respect for patients’ values, preferences and expressed needs; (ii) coordination and integration of care; (iii) information and communication; (iv) physical comfort; (v) emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; (vi) involvement of the significant other; (vii) continuity and transition; (viii) access to care; (ix) technical skills; and (x) endometriosis clinic staff (Table 2 ). The outcomes are converted to scores ranging from 0 to 100 for each category. The patient-centredness scores from the same university hospital obtained by Schreurs and colleagues are used as a reference population (Schreurs et al., 2020).

Table 2.

Examples of care aspects per dimension

| Dimension | Example of ENDOCARE questionnaire care aspect |

|---|---|

| Respect for patients’ values, preferences and expressed needs | My complaints were taken seriously |

| Coordination and integration of care | Care was taken to plan examinations and treatments on 1 day |

| Information and communication | Everything necessary was done so that I would understand the information given |

| Physical comfort | The consultation waiting room is comfortable |

| Emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety | I was informed as to the psychological impact of endometriosis |

| Involvement of significant other | There were efforts to involve my partner during consultations |

| Continuity and transition | The physician who is treating me really follows up on my case personally |

| Access to care | I was able to contact a caregiver with specific knowledge of endometriosis in urgent cases |

| Technical skills | I was able to rely on the expertise of the caregivers |

| Endometriosis clinic staff | The caregivers were understanding and concerned during my treatment |

The healthcare provider questionnaire consisted of two different subsections: (i) demographics and (ii) assessment of virtual care. The questions used mirrored the questions in the patient questionnaires on virtual care (Supplementary information).

When respondents did not complete the full questionnaire but did complete one or more sections, the completed sections were included in the analysis.

Timeline of COVID-19 restrictions

From 16 March 2020 the Netherlands was in the first lockdown and all elective and non-essential care was paused at that point. Fertility treatments that had started before the 16th of March were completed, but new or subsequent cycles were cancelled. Endometriosis consultations, investigations and surgeries were all cancelled, and only emergency consultations in cases of severe pain or bleeding were possible. From mid-May 2020 planned care was able to slowly restart in the Netherlands.

The questionnaires for infertility patients and endometriosis patients were sent during this lockdown. The questionnaire for healthcare providers was sent shortly after the lockdown. During this period physical consultations were possible, but only in limited capacity, so telephone and video consultations were still used regularly throughout the Netherlands.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 24 (IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to report on the demographics of participants and the assessment of virtual care. One-way analysis of variance were used to test differences between infertility patients, endometriosis patients and endometriosis patients with infertility.

The results of the FertiQoL and ECQ questionnaires were analysed according to their respective guidelines (Aarts et al., 2011; Boivin et al., 2011; Dancet et al., 2011; Dancet et al., 2012). The means and standard deviations provided for the FertiQoL related to the infertility patients were compared with those provided for the Dutch reference population, and mean differences with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Linear regression was used to assess the association of the baseline variables age and duration of subfertility with the FertiQoL scores. For the ECQ no comparative statistics were possible in relation to the reference population of the questionnaire, so the results are shown in a bar chart. Answers to the open-ended questions were read and explanations for the results from the questionnaires were sought.

Results

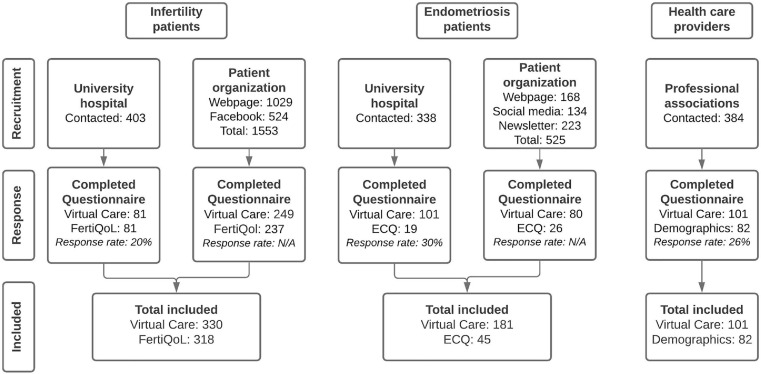

A total of 330 infertility patients (81 from the university hospital, 249 from the patient organization), 181 endometriosis patients (101 from the university hospital, 80 from the patient organization) and 101 healthcare providers responded. Not all questionnaires were fully completed, but all available data were used in the results (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Recruitment of participants. The response rate was calculated for the participants from the university hospital and the healthcare providers. As the participants from the patient organizations were recruited via social media, the number of individual clicks on the link are given but a response rate cannot be calculated. Virtual care refers to the part of the questionnaire consisting of questions evaluating telephone consultations and video consultations. ECQ, ENDOCARE questionnaire.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics for the infertility patients are shown in Table 3 , and those for the women with endometriosis in Table 4 . The median age of the infertility patients was 33. Around half of the infertility patients suffered from primary infertility. The participants from the endometriosis population had a median age of 35 and predominantly reported having moderate to severe endometriosis. One-third of the participants with endometriosis reported a change in endometriosis complaints during COVID-19. Of these participants, 81.7% reported an increase in endometriosis symptoms.

Table 3.

Characteristics of infertility participants

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR] | 33.00 (30.00–36.00) |

| Primary infertility, n (%) | 167 (50.6) |

| Has children, n (%) | 84 (25.5) |

| Pregnant at time of participation, n (%) | 1 (0.3) |

| Duration of infertility (months), median (95% CI) | 27.5 (18.0–39.0) |

A total of 330 fertility patients completed the patient characteristics part of the questionnaire.

Table 4.

Characteristics of endometriosis patients

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35.00 (31.00–40.50) |

| Stage of endometriosisa | |

| Minimal to mild | 18 (9.9) |

| Moderate to severe | 117 (64.6) |

| Unknown | 46 (25.4) |

| Surgical confirmation of diagnosis | 101 (55.8) |

| Change in endometriosis-related complaints during COVID-19 | 60 (33.1) |

| Reported increase in complaintsb | 49 (81.7) |

| Reported decrease complaintsb | 16 (26.7) |

| Hormonal treatment | 93 (51.4) |

| Pregnant at time of participation | 3 (1.7) |

| Has children | 61 (33.7) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

A total of 181 endometriosis patients completed the patient characteristics part of the questionnaire.

Determined at first diagnosis

Patients were able to report both an increase and a decrease in complaints.

The healthcare providers had a median age of 45.5 years and the majority were gynaecologists (Supplementary Table 1).

Virtual alternatives to regular care

A total of 88% of infertility patients reported that appointments were cancelled or postponed during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thirty-three per cent of participants reported that physical infertility appointments were converted to telephone consultations, and 4% reported conversion to video consultations. Of the endometriosis patients, 67% reported that physical appointments were adjusted to telephone consultations, while 3% of patients had appointments changed to video consultations. Of the healthcare providers, 83% reported that one or more of their physical appointments had been changed to a telephone consultation and 39% reported conversion to video consultations. For both infertility and endometriosis patients, healthcare providers spent a median time of 15 min on telephone consultations and 20 min on video consultations.

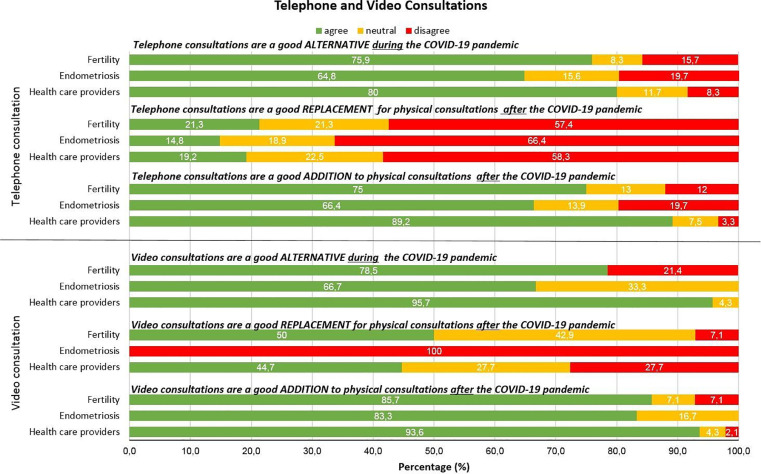

The evaluation of virtual care methods by infertility patients, endometriosis patient and healthcare providers is shown in Figure 2 . During the lockdown, telephone consultations and video consultations were seen as good alternatives for physical appointments. For the future, both telephone consultations and video consultations were thought to be useful additions to physical appointments. Telephone consultations were not seen as good replacements for future physical appointments by the majority of respondents. On video consultations as a replacement for future physical appointments, respondents were more positive, but still not truly convinced. Endometriosis patients in particular still preferred a physical appointment (six respondents).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of virtual care options by infertility patients, endometriosis patients and their healthcare providers. ‘Good alternative’ refers to the situation during the pandemic; ‘Good addition’ and ‘Good replacement’ refer to consultations in the time after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Coping with altered care

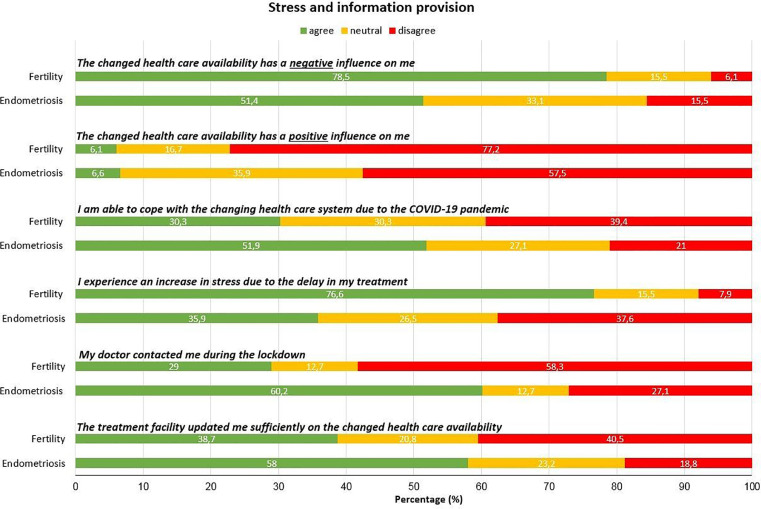

The results on stress and spread of information as reported by the infertility patients and endometriosis patients are presented in Figure 3 . The results on stress (‘I experience an increase in stress due to the delay in my treatment’) differed between the patient groups: 76.6% of the infertility patients agreed with this statement against only 35.9% of the endometriosis patients (P < 0.001). A similar difference was seen in self-reported coping (‘I am able to cope with the changing health care system due to the COVID-19 pandemic’), where 30.3% and 51.9% of infertility and endometriosis patients, respectively, agreed (P < 0.001). In addition, of a subgroup of endometriosis patients who were currently undergoing fertility treatment (n = 23), 60.9% reported increased stress and 43.5% reported that they were able to cope (Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 3.

Experienced stress and communication. A total of 330 fertility patients and 181 endometriosis patients completed the stress and coping-related questions.

Open-ended questions

Both infertility patients and endometriosis patients reported that the use of telephone consultations and video consultations is seen as a feasible option when no physical examinations are needed. For infertility patients, acceptable appointments to use telephone consultations or video consultations for could be communicating laboratory results or solely providing information. Possible examples for the use of telephone consultations and video consultations with endometriosis patients were follow-up consultations with known patients or discussing alterations in medication. The downside noted by infertility patients during the COVID-19 pandemic is that they missed personal contact with their doctor as fertility treatments are intensive treatments. For endometriosis patients, a reported downside was missing the choice to be able to have a physical consultation when they felt they needed one.

Healthcare providers reported the lack of travel time, being able to provide a safe alternative for healthcare during the pandemic, and time efficiency (e.g. ‘patients don't have to wait when the doctor is delayed’ and ‘more flexible planning of appointments’) as benefits of telephone consultations. The additional benefit that video consultations have over telephone consultations according to healthcare respondents is the ability to experience non-verbal communication as well as being able to have conversations with the patient and their partner at the same time. The most important downside of telephone consultations reported by healthcare providers was the lack of non-verbal communication. For video consultations, healthcare providers reported technical difficulties (including connection errors and patients not understanding the technology) to be the most important downside.

Not being able to perform physical examinations and additional investigations (e.g. ultrasonography or blood sampling) and difficulties with providing emotional support were recorded as downsides for both telephone and video consultations.

Fertility patients reported having an increase in stress, reasons being increasing age, which could damage the chance of pregnancy, fear of aggravating underlying illness and ambiguity in information from the hospitals on when treatments could restart.

Infertility patients’ quality of life

The fertility-related quality of life information of the infertility patients (n = 318) and the data from a Dutch reference population (n = 473) are shown in Table 5 (Aarts et al., 2011), with the core FertiQoL subdomains shown separately. Although a statistical comparison between the infertility patients in this study and the reference population was not possible due to a lack of access to the data describing the reference population, the quality-of-life scores seem to be lower in the group in the current study compared with the reference population for all subdomains of the FertiQoL.

Table 5.

Fertility-related quality of life as reported in the core FertiQoL outcome and the subscales

| Fertility patients Mean (SD) | Reference populationa Mean (SD) | Difference Mean (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core FertiQoL | 58.6 (14.8) | 70.8 (13.9) | 12.2 (10.2–14.2) |

| Social subscale | 63.3 (17.8) | 74.0 (16.6) | 10.7 (8.3–13.1) |

| Relational subscale | 71.6 (17.1) | 78.2 (14.5) | 6.6 (4.4–8.8) |

| Emotional subscale | 45.4 (20.2) | 59.8 (18.7) | 14.4 (11.7–17.1) |

| Mind–body subscale | 54.0 (20.1) | 70.8 (19.5) | 16.8 (13.9–19.6) |

A total of 318 out of 330 patients completed the FertiQoL questionnaire. The reference population consisted of 473 patients.

Subgroup analysis showed that increasing female age was associated with a lower relational score (P = 0.005) and primary infertility was associated with a higher score on the mind–body and relational domains (P < 0.001).

Patient centredness of endometriosis care

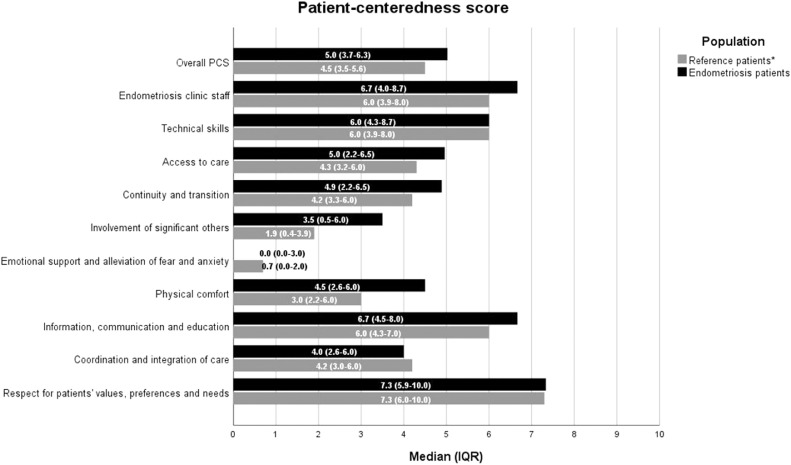

Figure 4 demonstrates the patient-centredness scores for endometriosis participants (n = 45) measured using the ECQ. As a reference, the patient-centredness scores from 177 patients reported by Schreurs and colleagues (Schreurs et al., 2020) were added to the figure as a comparison with the pre-COVID-19 situation. The patient-centredness of endometriosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic seems comparable to that of the reference population that was used.

Figure 4.

Patient-centredness scores (PCS) by dimension, as measured by the ENDOCARE questionnaire. A total of 45 out of 181 endometriosis patients completed the ENDOCARE questionnaire. The reference population consisted of 177 patients.*Schreurs et al, 2020. IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

This study shows that the use of virtual care, specifically telephone and video consultations, during the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic proved to be a good alternative to regular physical consultations for the large majority of patients with infertility and endometriosis and their healthcare providers. Both the patient groups and the healthcare providers thought that the use of telephone consultations would be a good addition to regular care in the future, but that it could not replace regular physical consultations. All groups were positive about video consultations, although video consultations had not yet been widely implemented at the time of this study. Quality of life in infertility patients appeared to be lower for all subdomains when compared with the reference population. The patient-centredness of endometriosis care during the COVID-19 pandemic seems comparable to that of the reference population used.

The first lockdown in the Netherlands came quite suddenly. One of the strengths of this study was the early distribution of questionnaires to the patients during the first lockdown of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limits the chance of recall bias from patients. The use of the validated FertiQoL and ECQ allowed for an objective and validated measurement of quality of life for infertility patients and of patient-centredness of endometriosis care during COVID-19.

The questionnaires were developed in collaboration with two patient organizations to ensure that the questions were relevant and reflected patients’ experiences during that stage of the pandemic. Due to the short time frame of this study and despite the extensive collaboration with the patient organizations and multiple reminders to complete the questionnaires, the response rate remained relatively low, and this is a potential source of response bias.

The use of virtual care as an alternative for physical consultations during the pandemic was rated positively by patients; these results are in line with recently published studies during the COVID-19 pandemic (Barsom et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Lun et al., 2020). Yet the replacement of physical consultations by telephone consultations in the future was not seen as a desirable option by the majority of patients from both groups. A possible explanation is that fertility treatments are not possible without physical appointments, for instance for the monitoring of follicle growth. Endometriosis patients receive regular check-ups where their physician routinely performs a physical examination, including transvaginal ultrasonography. The desire to obtain reassurance in this way might also explain why endometriosis patients prefer physical appointments. However, the results should be interpreted with caution, as the number of respondents to these questions was low.

In the current study, the use of video consultations was limited in both patient groups while 39% of the healthcare providers reported using video consultations. A possible reason for this difference could be that the questionnaire for healthcare providers was distributed 3 months later than the questionnaire for patients. After the first lockdown an increased use of video consultations may have occurred as hospitals were developing strategies to continue consultations without inviting patients to their clinics. Another possibility for this difference is that healthcare providers have multiple appointments a day, so an overestimation of the number of video consultations by recall bias cannot be excluded. In accordance with both patient groups, the healthcare providers reported that video consultations are a good addition to regular care for the future, and this is also in line with other recent studies (Barsom et al., 2020; Jimenez-Rodriguez et al., 2020). The benefit of video consultations compared with telephone consultations lies in the visual aspect, which aids non-verbal communication and gives a more personal interaction (Jimenez-Rodriguez et al., 2020).

During the same period that this study was being conducted, the Dutch Institute for Public Health and the Environment reported that 23.9% of Dutch citizens were experiencing high levels of stress (RIVM, 2020). This is much lower than the 76.7% of the infertility patients who reported stress in the current study. Unfortunately, the specific reasons for this increase of stress were not explored. Earlier studies showed that women with infertility experience a high sense of urgency to obtain treatment (Aarts et al., 2011). The current delay in treatment due to the pandemic could intensify feelings of stress and urgency, as treatment cancellation has previously been negatively associated with quality of life in infertility patients (Heredia et al., 2013). A recent study by Boivin and colleagues found similar results: 11% of participants reported feeling unable to cope with the stress caused by fertility clinic closure (Boivin et al., 2020). Another study investigating the perceptions and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infertile patients identified that feeling helpless and having lower self-control and less social support were correlated with higher psychological distress (Ben-Kimhy et al., 2020).

In the current study, women with endometriosis experienced less stress than those with infertility. This may be related to the chronic nature of their illness in comparison to the more time-sensitive issues that patients with fertility problems face. In addition, even though continuous endometriosis care is valued as important, endometriosis patients might be able to accept a temporary decrease of care possibilities or a delay in their yearly appointment. A study performed in Turkey during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic showed that 83.9% of responders were afraid of experiencing endometriosis-related problems during the pandemic, and 63.0% were afraid that their healthcare professional might be unavailable to them during the pandemic (Yalcin Bahat et al., 2020). In the current study, only 33.1% of patients actually experienced changes in endometriosis-related complaints, indicating that the high levels of fear of endometriosis-related problems as previously reported by patients are an overestimation of the actual numbers.

The results of the patient-centredness scores reported by women with endometriosis during the first lockdown were similar to those of the reference population outside the COVID-19 pandemic. This indicates that even during a COVID-19 pandemic, the same care aspects remain important to patients.

At the time of writing, the Netherlands is recovering from the second lockdown of the pandemic. In contrast to the first lockdown, fertility treatments and endometriosis care have continued, with some restrictions on the number of physical consultations a day and a diminished capacity for surgical and ART care. With the results of the current study in mind, the importance of continuity of care can be underlined. Even though fertility care can be classified as ‘non-essential’ or ‘not life threatening’ during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study shows that restriction of care is associated with an increase in stress and a lowered quality of life among infertile women. It is necessary to stress the importance of the use of virtual care in combination with regular physical care to continue treatment for infertility patients as much as is possible.

This study shows that women with endometriosis do not experience the same level of stress as a result of the temporary halting of their treatment as women with infertility do, and the ECQ results are comparable to the reference population. It can, however, be advised that healthcare providers should be accessible for endometriosis patients, and that they should make sure that their patients know how to reach them with questions related to an increase of endometriosis complaints.

Conclusions

Virtual care seems to be a good alternative for infertility and endometriosis patients in circumstances where physical consultations are not possible. Self-reported stress is especially high in infertility patients during the COVID-19-pandemic and they do not feel that they can cope well with the changes to their care. Healthcare providers should aim to increase their patients’ ability to cope with the healthcare changes. Future research should focus more on the role of video consultations as this approach has only recently been implemented in current care.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant from ZonMw, a Dutch government funder (reference number 10430042010008).

Biography

Kimmy Rosielle obtained her medical degree at the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in 2017. She is currently working as a PhD student at the Department of Reproductive Medicine of the Amsterdam University Medical Center. Her thesis focuses on evaluating the diagnostic and therapeutic effects of visual tubal patency tests.

Key message.

Patients with infertility, endometriosis patients and their healthcare providers rate telemedicine as a good alternative during the pandemic but agree that it cannot replace physical consultations in the future. Fertility patients report a lower quality of life during this period. Patients with endometriosis judge the care to be comparable to the reference population.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Declaration: V.M., C.B.L. and M.G. report that their department receives unrestricted grants from Guerbet, Merck and Ferring outside the submitted work. The other authors report no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.06.001.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Aarts J.W., van Empel I.W., Boivin J., Nelen W.L., Kremer J.A., Verhaak C.M. Relationship between quality of life and distress in infertility: a validation study of the Dutch FertiQoL. Hum. Reprod. 2011;5:1112–1118. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apers S., Dancet E.A.F., Aarts J.W.M., Kluivers K.B., D'Hooghe T.M., Nelen W. The association between experiences with patient-centred care and health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2018;2:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsom E.Z., Feenstra T.M., Bemelman W.A., Bonjer J.H., Schijven M.P. Coping with COVID-19: scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nat. Med. 2020;5:632–634. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsom E.Z., Jansen M., Tanis P.J., van de Ven A.W.H., Blusse van Oud-Alblas M., Buskens C.J., Bemelman W.A., Schijven M.P. Video consultation during follow up care: effect on quality of care and patient- and provider attitude in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2020;3:1278–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07499-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Kimhy R., Youngster M., Medina-Artom T.R., Avraham S., Gat I., Haham L.M., Hourvitz A., Kedem A. Fertility patients under COVID-19: Attitudes, Perceptions, and Psychological Reactions. Hum. Reprod. 2020;12:2774–2783. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Harrison C., Mathur R., Burns G., Pericleous-Smith A., Gameiro S. Patient experiences of fertility clinic closure during the COVID-19 pandemic: appraisals, coping and emotions. Hum. Reprod. 2020;11:2556–2566. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J., Takefman J., Braverman A. The fertility quality of life (FertiQoL) tool: development and general psychometric properties. Hum. Reprod. 2011;8:2084–2091. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry H., Nadeem S., Mundi R. How Satisfied Are Patients and Surgeons with Telemedicine in Orthopaedic Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2020;1:47–56. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancet E.A., Ameye L., Sermeus W., Welkenhuysen M., Nelen W.L., Tully L., De Bie B., Veit J., Vedsted-Hansen H., Zondervan K.T., De Cicco C., Kremer J.A., Timmerman D., D'Hooghe T.M. The ENDOCARE questionnaire (ECQ): a valid and reliable instrument to measure the patient-centeredness of endometriosis care in Europe. Hum. Reprod. 2011;11:2988–2999. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancet E.A., Apers S., Kluivers K.B., Kremer J.A., Sermeus W., Devriendt C., Nelen W.L., D'Hooghe T.M. The ENDOCARE questionnaire guides European endometriosis clinics to improve the patient-centeredness of their care. Hum. Reprod. 2012;11:3168–3178. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geukens E.I., Apers S., Meuleman C., D'Hooghe T.M., Dancet E.A.F. Patient-centeredness and endometriosis: Definition, measurement, and current status. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018;50:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heredia M., Tenias J.M., Rocio R., Amparo F., Calleja M.A., Valenzuela J.C. Quality of life and predictive factors in patients undergoing assisted reproduction techniques. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013;2:176–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Rodriguez D., Santillan Garcia A., Montoro Robles J., Rodriguez Salvador M.D.M., Munoz Ronda F.J., Arrogante O. Increase in Video Consultations During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Healthcare Professionals' Perceptions about Their Implementation and Adequate Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;14:5112. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.L., Chan Y.C., Huang J.X., Cheng S.W. Pilot Study Using Telemedicine Video Consultation for Vascular Patients' Care During the COVID-19 Period. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020;68:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun R., Walker G., Daham Z., Ramsay T., Portela de Oliveira E., Kassab M., Fahed R., Quateen A., Lesiuk H., M P.D.S., Drake B. Transition to virtual appointments for interventional neuroradiology due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of satisfaction. J. Neurointerv. Surg. 2020;12:1153–1156. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massarotti C., Gentile G., Ferreccio C., Scaruffi P., Remorgida V., Anserini P. Impact of infertility and infertility treatments on quality of life and levels of anxiety and depression in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019;6:485–489. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1540575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIVM, 2020. Resultaten 3e ronde: Welbevinden en leefstijl. 01-12-2020

- Schreurs A.M.F, van Hoefen Wijsard M., Dancet E.A.F, Apers S., Kuchenbecker W.K.H., van de Ven P.M., Lambalk C.B., Nelen W.L.D.M., van der Houwen L.E.E., Mijatovic V. Towards more patient-centered endometriosis care: a cross-sectional survey using the ENDOCARE questionnaire. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa029. hoaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgsten H., Skoog Svanberg A., Ekselius L., Lundkvist O., Sundstrom Poromaa I. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in infertile women and men undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment. Hum. Reprod. 2008;9:2056–2063. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2006. Quality of care: a process for making strategic choices in health systems.

- Yalcin Bahat P., Kaya C., Selcuki N.F.T., Polat I., Usta T., Oral E. The COVID-19 pandemic and patients with endometriosis: A survey-based study conducted in Turkey. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020;2:249–252. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.