Abstract

Prolonged pharmacological interventions have detrimental health consequences by developing drug tolerance or drug resistance, in addition to adverse drug events. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic-related stress has adversely affected the emotional and mental health aspects around the globe. Consequently, depression is growing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides specific pharmacological interventions, which if prolonged have detrimental health consequences, non-pharmacological interventions are needed to minimize the emotional burden related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Laughter therapy is a universal non-pharmacologic approach to reduce stress and anxiety. Therapeutic laughter is a non-invasive, cost-effective, and easily implementable intervention that can be used during this pandemic as a useful supplementary therapy to reduce the mental health burden. Laughter therapy can physiologically lessen the pro-stress factors and increase the mood-elevating anti-stress factors to reduce anxiety and depression. In this ongoing stressful period of the COVID-19 pandemic, keeping necessary social distancing, it is important to create a cheerful environment that will facilitate laughter among the family, neighbor, and community to cope with the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: Laughter, Anxiety, Insomnia, Depression

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Prolonged pharmacological interventions have detrimental health consequences.

-

•

Laughter therapy is a universal non-pharmacologic approach to reduce stress and anxiety.

-

•

Therapeutic laughter is a non-invasive, cost-effective, and easily implementable intervention.

-

•

Laughter therapy can be used during COVID-19 pandemic as a useful supplementary therapy to reduce the mental health burden.

1. COVID-19 and stress

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic-associated stress has impacted the quality of life of many people by negatively affecting the emotional and mental health aspects. Studies have shown that the number of individuals affected by depression has risen during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bareeqa et al., 2020; Bueno-Notivol et al., 2021). A population-based survey (U.S. adults aged 18 or older) has shown a three-fold increase in depression in the earlier months of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ettman et al., 2020). Additional surveys (conducted by multiple U.S. academic institutes from Indiana, New Mexico, Florida, and Texas) have found more than one-third of the adult U.S. population are having COVID-19-related distress (Khubchandani et al., 2021); the prevalence of and psychological distress (39%), anxiety (42%), and depression (39%) were also estimated by analyzing 1978 individuals across the U.S. (Khubchandani et al., 2021). Such COVID-19 pandemic-related stress, anxiety, and depression are likely to progress into debilitating mental illness, if timely intervention is not offered. Of relevance, persistent stressors can impair mental health and induce cardiovascular complications and metabolic diseases, including obesity and diabetes (Arigo et al., 2020; Cuevas et al., 2020; Gomez-Perez et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2020; Walker et al., 2020). The COVID-19-related fear of health risks, amalgamated with the anxiety of economic hardship, is preferentially affecting the vulnerable populations, including women, the elderly, and low resource communities (Ettman et al., 2020). Overuse and misuse of drugs in the management of COVID-19-associated signs and symptoms are a serious health concern, and finding non-pharmacological interventions to reduce pandemic-associated health hazards is an urgent necessity. Of importance, exacerbation of antimicrobial resistance due to unrestricted use of antimicrobial drugs appears to be another casualty of the COVID-19 pandemic (Razzaque, 2020e). Implementing antimicrobial stewardship to minimize the needless use of antimicrobial therapies to lessen the drug resistance in this pandemic should be a medical priority (Razzaque, 2020b; f).

2. Laughter as an intervention

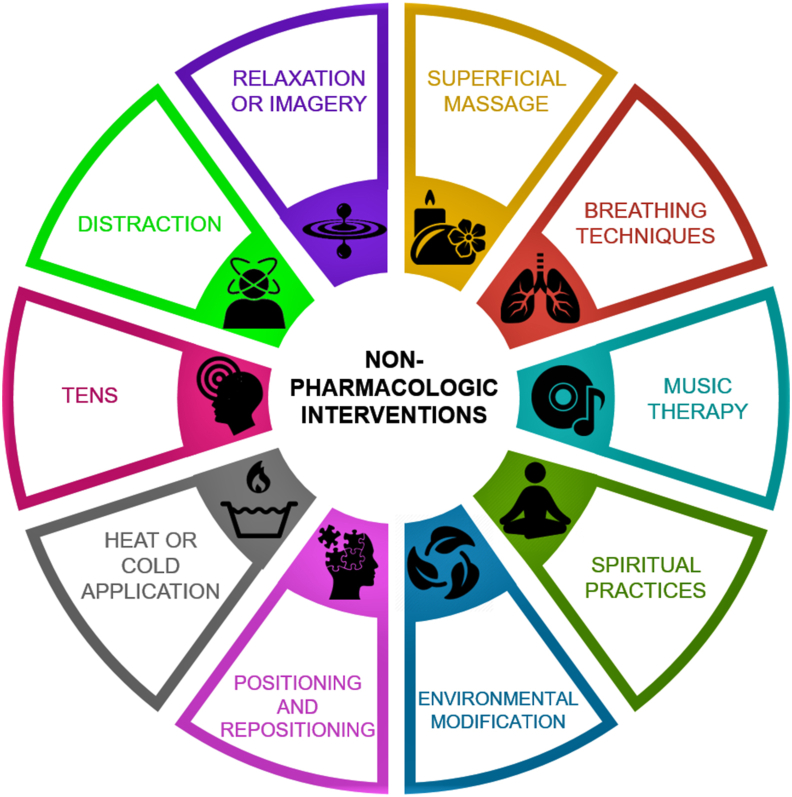

Non-pharmacologic interventions are recognized as being a useful approach to reduce pain, stress, and anxiety. Nonpharmacologic interventions range from superficial massage to breathing exercise to music therapy to yoga to spiritual practices (Lewis et al., 2018) (Fig. 1). Laughter therapy, one of the key non-pharmacological interventions, is a universal approach to reduce stress and anxiety. From ancient times, laughter has been used to influence cognitive behavior to improve and establish healthy physical, psychological, and social relationships. Studies have documented the positive role of laughter in enhancing the quality of life (Kuru and Kublay, 2017; Heidari et al., 2020). Laughter therapy may be used for both preventive and therapeutic purposes. Laughter can also be a clinical predictor of functional disability. An analysis of 14,233 elderly individuals (aged ≥65 years), selected for the ‘Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study’, a low frequency of laughter has shown to be linked to a higher risk of developing functional disability (Tamada et al., 2020); adjusting the potential confounders, the investigators reported an increased hazard ratio of functional disability among the individuals with decreased frequency of laughter. About 1.42 times higher risk of functional disability was noted among the individuals with low or no laughing habits (Tamada et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Major types of non-pharmacologic interventions.

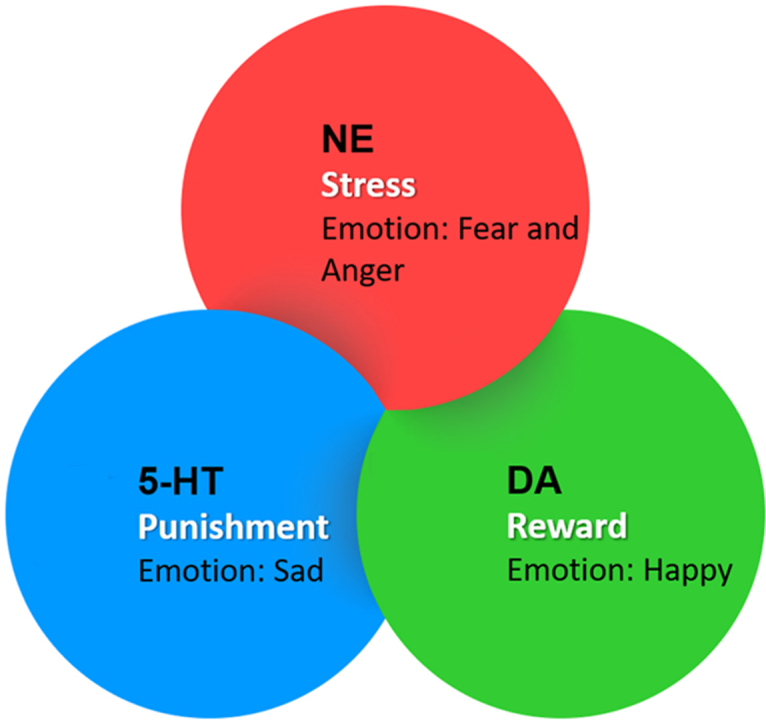

There is a biological explanation of how laughter is reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. Laughter has been shown to exert stress-reducing effects by suppressing the bioactivities of epinephrine, cortisol, and 3,4-dihydrophenylacetic acid (a major dopamine catabolite) (Berk et al., 1989; Yim, 2016). Reduced neurotransmitter activities, including norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine are linked to depression, and laughter is shown to enhance dopamine and serotonin activities (Yim, 2016). Emotion is an expression from the mixture of the three monoamine neurotransmitters: norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin (Wang et al., 2020). A three-dimensional model for monoamine neurotransmitters and basic emotions is suggested, where each basic emotion has its own concentration level of neurotransmitters (Lovheim, 2012). The model was based on an elaborate and comprehensive theory of basic emotions, where human emotions were divided into one neutral (surprise/startle), two positive (interest/excitement and enjoyment/joy), and five negatives (distress/anguish, fear/terror, shame/humiliation, contempt/disgust, and anger/rage) categories, and further connects them with facial expressions, and posture as well as typical physiological manifestations (Tomkins and Mccarter, 1964; Tomkins, 1975; Atwood and Tomkins, 1976). Gu et al. proposed a “three primary color model” of basic emotions: norepinephrine is responsible for fear and anger emotions, joy is subsided by dopamine, while punishment is subsided by serotonin (Gu et al., 2018). Many follow-up studies have supported this emotion theory and reported that three monoamines (as substrates) might play a central role in emotional expression, including laughter (Gu et al., 2016, 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

A randomized controlled trial of laughter intervention on patients with schizophrenia has found differential regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BNDF) and cortisol, when significantly higher serum levels of BDNF were recorded following 8-week of simulated laughter therapy, the level of BNDF dropped following discontinuation of laughter intervention (Cheng et al., 2020). No change in cortisol level was noted following 8 weeks of laughter therapy (Cheng et al., 2020). Whether simulated laughter intervention can be used as an alternative or complementary treatment or as a social support system for rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia to reduce their stress responses will need additional studies, but the potential exists for such non-pharmacology intervention as a supportive treatment (Cheng et al., 2020).

Laughter therapy has been shown to benefit a wide range of non-COVID-19 patients. A Japanese study conducted on 41 female patients with rheumatoid arthritis has shown that the basal level of serum growth hormone in rheumatoid arthritis patients was markedly elevated, as compared to the healthy control subjects, and the level of growth hormone significantly reduced in rheumatoid arthritis patients following laughter therapy (Ishigami et al., 2005). In a similar line of study, the basal levels of serum proinflammatory cytokines, Interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-alpha), were markedly higher in the rheumatoid arthritis patients than the healthy controls; the serum levels of IL-6 and TNF-alpha significantly reduced in the rheumatoid arthritis patients after laughter intervention (Matsuzaki et al., 2006). Additionally, the laughter-induced release of endorphins can help in reducing depressed mood (Lebowitz et al., 2011). Without even pharmacological intervention, laughter therapy can physiologically lessen the pro-stress factors and increase the mood-elevating anti-stress factors to reduce the stress responses, including anxiety and depression (Bennett and Lengacher, 2009). Laughter can also assist muscle relaxation and increase circulation to reduce the physical symptoms of stress. Moreover, laughter may decrease pain sensation by facilitating the synthesis of natural painkillers. In addition, studies have shown that laughter can enhance the tolerance of pain (Dunbar et al., 2012; Lapierre et al., 2019).

Although laughter is the natural expression of positive emotion, it can be broadly grouped into five different categories (Table 1). Laughter has a wide range of benefits, ranging from increase cognitive functions to improve respiration to enhance pain tolerance threshold to reduce stress hormones, with cumulative effects being the improved psychological well-being (Scholl and Ragan, 2003; Sahakian and Frishman, 2007; Yim, 2016). Hence, laughter therapy is used to augment psychosocial behaviors to improve the overall quality of life (Ko and Youn, 2011). Depression is one of the frequently observed mental disorders, and clinical depression needs pharmacological intervention. Laughter can mitigate the adverse consequences of stress and reduce depression by releasing neurotransmitters (Farifteh et al., 2014). While it is not always possible to dissociate confounding factors, laughter therapy tends to increase the sense of well-being across age groups and gender, including vulnerable elderly individuals (Gonot-Schoupinsky and Garip, 2018). In a meta-analysis on 814 participants from 10 published studies, laughter interventions were reported to significantly reduce depression and anxiety levels, along with an increase in better quality of sleep; the benefits on depression were more pronounced with long-term laughter intervention (Zhao et al., 2019). In a randomized controlled trial (aged ≥60 years), a laughter therapy program lead to reduced anxiety and insomnia among the elderly participants, with the resultant effect being the overall improvement of the general health (Ghodsbin et al., 2015). Similar positive effects on depression and insomnia were also documented following laughter therapy among the community-dwelling (≥60 years of age and living independently) elderly individuals in South Korea (Ko and Youn, 2011). In another study on 26,368 elderly Japanese individuals (men, 12,174; women, 14,194; aged ≥60 years), after adjusting for depression, sociodemographic factors, and social participation, the prevalence ratio for poor subjective health was noted among women who hardly laughed as compared with those who reported to have daily laughing habits (Hayashi et al., 2015). Of relevance, laughter in the elderly population is associated with the status of their oral health. In another Japanese study, conducted on the 11,239 male and 12,799 female community-dwelling elderly individuals, after adjusting for all covariates, the participants with 10 or more teeth were more likely to laugh than the edentulous (lacking teeth) participants (Hirosaki et al., 2021). The association between (the status of) oral health and (subsequent implications on) general health is well-documented in various systemic diseases, including diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Table 1.

Five main categories of laughter (Yim, 2016).

|

|

|

|

|

3. Conclusion and recommendation

Laughter is a human asset, and effectively using laughter to minimize short-term and long-term stresses can significantly improve the quality of life (Zhao et al., 2019). The potential benefits of laughter are summarized in Fig. 2. In fact, in this ongoing stressful period of COVID-19 pandemic, creating a cheerful environment to laugh is perhaps more important than ever to cope with the stresses related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therapeutic laughter is a non-invasive, cost-effective and easily implementable intervention that can be used as an effective complementary therapy to reduce the intensity of many mental illnesses (Van Der Wal and Kok, 2019). However, the effects of laughter on the neuroendocrine, and immune systems are needed to be objectively studied to define the underlying molecular regulation of psychosocial behaviors.

Fig. 2.

A few potential benefits of laughter therapy.

In the absence of specific pharmacological therapy for COVID-19, non-pharmacological interventions (Fig. 1) to lessen emotional and physical stresses related to COVID-19 are essential. Such non-pharmacological interventions and community compliance are required to attain the desired goals of minimizing COVID-19 transmission and reduce stress-related burdens. It appears likely that maintaining an adequate nutritional balance through healthy eating habits, keeping an active lifestyle, along with practicing laughter can help in reducing the stress-related disease burden of COVID-19 pandemic and other chronic debilitating diseases (Razzaque, 2020d; c;a; Abukabda and Razzaque, 2021; Razzaque, 2021).

Author contributions

Mohammed S. Razzaque conceptualized, designed, drafted and edited the manuscript. Nuraly S. Akimbekov edited the manuscript and contributed to the artworks.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Margo Wolfe, Dr. Arafat Tannum and Ms. Peace Uwambaye for carefully reading the manuscript and providing useful suggestions. We also want to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Salim Hussain for providing helpful information on the psychiatric aspects of depression.

References

- Abukabda A.B., Razzaque M.S. COVID-19 pandemic: impacts of social lockdown on nutritional health and beyond. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2021;11:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Arigo D., Juth V., Trief P., Wallston K., Ulbrecht J., Smyth J.M. Unique relations between post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and patient functioning in type 2 diabetes. J. Health Psychol. 2020;25:652–664. doi: 10.1177/1359105317727839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood G.E., Tomkins S.S. On the subjectivity of personality theory. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1976;12:166–177. doi: 10.1002/1520-6696(197604)12:2<166::aid-jhbs2300120208>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareeqa S.B., Ahmed S.I., Samar S.S., Yasin W., Zehra S., Monese G.M., Gouthro R.V. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress in China during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychiatr. Med. 2020;91217420978005 doi: 10.1177/0091217420978005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M.P., Lengacher C. Humor and laughter may influence health IV. Humor and immune function. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2009;6:159–164. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk L.S., Tan S.A., Fry W.F., Napier B.J., Lee J.W., Hubbard R.W., Lewis J.E., Eby W.C. Neuroendocrine and stress hormone changes during mirthful laughter. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1989;298:390–396. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198912000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Notivol J., Gracia-Garcia P., Olaya B., Lasheras I., Lopez-Anton R., Santabarbara J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021;21:100196. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.L., Yang F.C., Chu H.T., Tsai C.K., Ku S.C., Tseng Y.T., Yeh T.C., Liang C.S. Incongruent expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cortisol in schizophrenia: results from a randomized controlled trial of laughter intervention. Psychiatr. Investig. 2020 doi: 10.30773/pi.2020.0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas A.G., Chen R., Slopen N., Thurber K.A., Wilson N., Economos C., Williams D.R. Assessing the role of health behaviors, socioeconomic status, and cumulative stress for racial/ethnic disparities in obesity. Obesity. 2020;28:161–170. doi: 10.1002/oby.22648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R.I., Baron R., Frangou A., Pearce E., Van Leeuwen E.J., Stow J., Partridge G., Macdonald I., Barra V., Van Vugt M. Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2012;279:1161–1167. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettman C.K., Abdalla S.M., Cohen G.H., Sampson L., Vivier P.M., Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. e2019686-e2019686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farifteh S., Mohammadi-Aria A., Kiamanesh A., Mofid B. The impact of laughter yoga on the stress of cancer patients before chemotherapy. Iran. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;7:179–183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodsbin F., Sharif Ahmadi Z., Jahanbin I., Sharif F. The effects of laughter therapy on general health of elderly people referring to jahandidegan community center in shiraz, Iran, 2014: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Commun. Based Nurs. Midwifery. 2015;3:31–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Perez D., Cancino M., Moreno P.I., Ortiz M.S. Weight stigma, chronic stress, unhealthy diet, and obesity in Chilean adults. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12529-020-09917-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonot-Schoupinsky F.N., Garip G. Laughter and humour interventions for well-being in older adults: a systematic review and intervention classification. Compl. Ther. Med. 2018;38:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S., Gao M., Yan Y., Wang F., Tang Y.Y., Huang J.H. The neural mechanism underlying cognitive and emotional processes in creativity. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1924. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu S., Wang W., Wang F., Huang J.H. Neuromodulator and emotion biomarker for stress induced mental disorders. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:2609128. doi: 10.1155/2016/2609128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Kawachi I., Ohira T., Kondo K., Shirai K., Kondo N. Laughter and subjective health among community-dwelling older people in Japan: cross-sectional analysis of the Japan gerontological evaluation study cohort data. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015;203:934–942. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M., Ghodusi Borujeni M., Rezaei P., Kabirian Abyaneh S., Heidari K. Effect of laughter therapy on depression and quality of life of the elderly living in nursing homes. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020;27:119–129. doi: 10.21315/mjms2020.27.4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirosaki M., Ohira T., Shirai K., Kondo N., Aida J., Yamamoto T., Takeuchi K., Kondo K. Association between frequency of laughter and oral health among community-dwelling older adults: a population-based cross-sectional study in Japan. Qual. Life Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami S., Nakajima A., Tanno M., Matsuzaki T., Suzuki H., Yoshino S. Effects of mirthful laughter on growth hormone, IGF-1 and substance P in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2005;23:651–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Webb F.J., Wiblishauser M.J., Bowman S.L. Post-lockdown depression and anxiety in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H.J., Youn C.H. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2011;11:267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuru N., Kublay G. The effect of laughter therapy on the quality of life of nursing home residents. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017;26:3354–3362. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre S.S., Baker B.D., Tanaka H. Effects of mirthful laughter on pain tolerance: a randomized controlled investigation. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019;23:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz K.R., Suh S., Diaz P.T., Emery C.F. Effects of humor and laughter on psychological functioning, quality of life, health status, and pulmonary functioning among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a preliminary investigation. Heart Lung. 2011;40:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M.J.M., Kohtz C., Emmerling S., Fisher M., Mcgarvey J. Pain control and nonpharmacologic interventions. Nursing. 2018;48:65–68. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000544231.59222.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovheim H. A new three-dimensional model for emotions and monoamine neurotransmitters. Med. Hypotheses. 2012;78:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki T., Nakajima A., Ishigami S., Tanno M., Yoshino S. Mirthful laughter differentially affects serum pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels depending on the level of disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2006;45:182–186. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R.L., Lucas-Thompson R.G., Sanchez N., Smith A.D., Annameier S.K., Casamassima M., Verros M., Melby C., Johnson S.A., Shomaker L.B. Effects of a mindfulness-induction on subjective and physiological stress response in adolescents at-risk for adult obesity. Eat. Behav. 2020;40:101467. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. Can excessive dietary phosphate intake influence oral diseases? Adv. Hum. Biol. 2020;10:35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. Commentary: microbial resistance movements: an overview of global public health threats posed by antimicrobial resistance, and how best to counter. Front. Publ. Health. 2020;8:629120. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.629120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. COVID-19 pandemic: can boosting immune responses by maintaining adequate nutritional balance reduce viral insults? Adv. Hum. Biol. 2020;10:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. COVID-19 pandemic: can maintaining optimal zinc balance enhance host resistance? Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2020;251:175–181. doi: 10.1620/tjem.251.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. Exacerbation of antimicrobial resistance: another casualty of the COVID-19 pandemic? Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1865802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship to reduce antimicrobial drug resistance. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1840977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque M.S. COVID-19 pandemic: can zinc supplementation provide an additional shield against the infection? Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:1371–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian A., Frishman W.H. Humor and the cardiovascular system. Alternative Ther. Health Med. 2007;13:56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl J.C., Ragan S.L. The use of humor in promoting positive provider-patient interactions in a hospital rehabilitation unit. Health Commun. 2003;15:319–330. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1503_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamada Y., Takeuchi K., Yamaguchi C., Saito M., Ohira T., Shirai K., Kondo K. Does laughter predict onset of functional disability and mortality among older Japanese adults? The JAGES prospective cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins S.S. The phantasy behind the face. J. Pers. Assess. 1975;39:551–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins S.S., Mccarter R. What and where are the primary Affects?Some evidence for a theory. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1964;18:119–158. doi: 10.2466/pms.1964.18.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wal C.N., Kok R.N. Laughter-inducing therapies: systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;232:473–488. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R.J., Garacci E., Campbell J.A., Egede L.E. The influence of daily stress on glycemic control and mortality in adults with diabetes. J. Behav. Med. 2020;43:723–731. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Yang J., Pan F., Ho R.C., Huang J.H. Editorial: neurotransmitters and emotions. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:21. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim J. Therapeutic benefits of laughter in mental health: a theoretical review. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2016;239:243–249. doi: 10.1620/tjem.239.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Yin H., Zhang G., Li G., Shang B., Wang C., Chen L. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of laughter and humour interventions on depression, anxiety and sleep quality in adults. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019;75:2435–2448. doi: 10.1111/jan.14000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]