Abstract

Prostate cancer (CaP) remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths in western men. These deaths occur because metastatic CaP acquires resistance to available treatments. The novel and functionally diverse treatment options that have been introduced in the clinic over the past decade each eventually induce resistance for which the molecular basis is diverse. Both initiation and progression of CaP have been associated with enhanced cell proliferation and cell cycle dysregulation. A better understanding of the specific pro-proliferative molecular shifts that control cell division and proliferation during CaP progression may ultimately overcome treatment resistance. Here, we examine literature for support of this possibility. We start by reviewing recently renewed insights in prostate cell types and their proliferative and oncogenic potential. We then provide an overview of the basic knowledge on the molecular machinery in charge of cell cycle progression and its regulation by well-recognized drivers of CaP progression such as androgen receptor and retinoblastoma protein. In this respect, we pay particular attention to interactions and reciprocal interplay between cell cycle regulators and androgen receptor. Somatic alterations that impact the cell cycle-associated and -regulated genes encoding p53, PTEN and MYC during progression from treatment-naïve, to castration-recurrent, and in some cases, neuroendocrine CaP are discussed. We considered also non-genomic events that impact cell cycle determinants, including transcriptional, epigenetic and micro-environmental switches that occur during CaP progression. Finally, we evaluate the therapeutic potential of cell cycle regulators, and address challenges and limitations approaches modulating their action, for CaP treatment.

Keywords: treatment resistance, castration, androgen receptor, proliferation

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (CaP) remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths in western men (Siegel et al., 2020). These deaths occur because of acquired resistance to the systemic therapies for metastatic CaP. Because of CaP’s well-known dependence on the androgen-activated androgen receptor (AR), for men whose localized CaP recurs after surgical and/or radiation therapies or who present with CaP that has spread beyond the prostate, androgen deprivation strategies remain the mainstay for treatment (Denmeade and Isaacs, 2002, Dai et al., 2017). Such treatments usually start with first-line androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) that inhibits androgen-activation of AR by interfering with androgen synthesis (e.g. leuprolide) or preventing androgens to interact with AR (e.g. bicalutamide). Despite initial remissions, almost invariably CaP recurs because AR signaling is reactivated, which led to the development of a repertoire of drugs that either more potently inhibit androgen biosynthesis (e.g. abiraterone acetate) and/or more efficiently compete for AR binding (e.g. enzalutamide, apalutamide) (Dai et al., 2017). Following a relatively short-lived response, CRPC growth resumes. In the majority of cases (~80%), CRPC re-growth occurs due to activating alterations in the AR signaling axis (Dai et al., 2017, Watson et al., 2015). In the remaining, smaller fraction of CRPC patients, potent second-generation AR inhibition activates alternative lineage programs including neuronal, neuroendocrine, stem-like, and developmental pathways that are associated with loss of AR and RB1/TP53 function (Beltran et al., 2016, Davies et al., 2020). Neuroendocrine CaP (NEPC) expresses markers of neuroendocrine differentiation (e.g. chromogranin, synaptophysin) and relies on transcription factors such as BRN2 and epigenetic modifiers such as EZH2 instead of AR to drive disease progression (Bishop et al., 2017, Dardenne et al., 2016).

After failure of AR-targeting therapies, treatment options become more limited and remissions are usually short-lived. CRPC treatment involves chemotherapy using for instance docetaxel or cabazitacel, and in some cases immunotherapy or treatments targeting bone microenvironment, a frequent site of CaP metastasis (James et al., 2016, Sweeney et al., 2015, Sweeney, 2019, Kantoff et al., 2010). NEPC is even more challenging to treat and options are mostly limited to platinum-based therapies (Aparicio et al., 2013). The therapeutic landscape for metastatic CaP is however, evolving rapidly and the scope of late stage CaP phenotypes, the mechanisms underlying acquired treatment resistance, and the drivers of lethal CaP progression are expected to become even more diverse and complex. Indeed, novel treatment options such as PARP inhibitors that are administered based on a patient’s CaP genomic make-up or germline, potent next generation AR targeting drugs that are increasingly considered for first-line ADT, and new combination therapies such as ADT and chemotherapy earlier in disease progression are becoming more routine (Mateo et al., 2015, James et al., 2016, Sweeney et al., 2015). The long term consequences of these emerging combinations and sequencing on CaP biology and mechanisms of treatment resistance remain unknown.

Deregulated cell proliferation has been recognized as the minimal common platform upon which all neoplastic evolution occurs. Cell proliferation is tightly regulated by orderly transitions through the cell cycle. Alteration in the cell cycle machinery is one of the major routes by which normal cell proliferation is converted into uncontrolled cell division and eventually carcinogenesis and cancer progression (Feitelson et al., 2015, Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). The therapeutic potential of targeting critical cell cycle checkpoints and the possibility of such strategies to overcome cancer treatment resistance and prolong patient survival has been recognized also (Otto and Sicinski, 2017, Whittaker et al., 2017). Yet the contribution of key cell cycle regulators and their molecular and genomic dysregulation to CaP growth, acquired treatment resistance and disease progression remain poorly understood. Here, we provide an updated overview of the spectrum of CaP cell cycle regulators, examine if and how their deregulation associates with treatment resistance and explore the potential of targeting these proteins as novel therapeutic targets to improve CaP survival.

2. Cell cycle regulation is central to CaP growth and progression

Cell proliferation and cell cycle progression are hallmarks of all human cancers, including CaP (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). However, the molecular mechanism(s) that control prostate (cancer) cell proliferation, and their contribution to CaP treatment resistance and progression remain poorly understood. In this section, we start by reviewing knowledge on the proliferation of prostate (cancer) cells, the cell of origin of CaP, the key phases of cell cycle progression, and cell cycle (dys)regulation that has been recognized to contribute to aggressive CaP behavior.

2.1. Proliferative potential of prostate (cancer) cells

The human prostate is a small accessory gland that is part of the male reproductive system. It is located below the bladder and surrounds the urethra and is composed of multiple acini and ducts that make up its glandular structure, are lined with epithelium, produce an alkaline fluid that is secreted as a major compound of the semen, and are embedded in a fibromuscular stromal network. The prostatic epithelium consists of two major layers of cells: an outer basal cell layer which rests on a basement membrane, and an inner luminal secretory cell layer which faces the lumen of the gland. A third minor population of neuroendocrine (NE) cells is interspersed between basal and epithelial cells (Selman, 2011, Verze et al., 2016).

Careful characterizations over the past decades had led to the consensus that luminal cells are terminally differentiated cells that express AR and differentiation markers such as prostate specific antigen (PSA) as well as low levels of cytokeratins 8 and 18. Basal cells were recognized to express high levels of cytokeratins 5 and 14 but not AR or differentiation markers (Ware, 1994). NE cells, on the other hand, lack differentiation markers but are rich in intracytoplasmic secretory granules and express high levels of NE differentiation markers such as chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Ware, 1994). Using techniques such as Ki67 immunostaining and thymidine incorporation assays, basal cells had been shown to display a higher proliferation rate than secretory luminal cells (Bonkhoff et al., 1994, Hudson et al., 2001, Bonkhoff and Remberger, 1996).The basal cell layer has also long been proposed to harbor the regenerative potential needed to maintain prostate physiology and to restore prostate structure and function after AR inactivation, such as that induced by ADT (Strand and Goldstein, 2015). Indeed, the reversal of androgen deprivation–induced involution of the prostate gland to about 90% of its normal size, which results from loss of luminal cells, by androgen re-administration has been attributed to a small percentage of rare prostate stem cells residing in the basal cell layer (Strand and Goldstein, 2015, Goldstein et al., 2008).

Very recently, the application of single cell transcriptomics has allowed to more precisely define the prostate cell populations and lineages, which is starting to elucidate further the regenerative potential of the basal and luminal prostate epithelial compartments. A pioneering study performed single cell RNA-Seq analyses on benign prostate tissues of healthy young men and uncovered 5 epithelial cell types, which included - in addition to basal, luminal and NE cell types - also 2 novel epithelial cell types that are enriched in the prostate urethra and proximal prostatic ducts (Henry et al., 2018). Simultaneously, others performed single cell transcriptomics analyses on mouse prostate tissues, some also validated their findings in benign human prostate tissues that were obtained from adult men (Guo et al., 2020, Karthaus et al., 2020, Crowley et al., 2020). Collectively, these efforts have confirmed the presence of previously unrecognized and functionally diverse prostate epithelial cell populations, which an initial comparative analysis of the transcriptome data sets from these distinct studies has started to reconcile (Crowley et al., 2020). The incorporation of mouse models verified the AR-dependence and the regenerative potential of these cell populations in organoid, tissue recombination and in vivo studies (Karthaus et al., 2020, Crowley et al., 2020), which uncovered that prostate regeneration can be driven by nearly all luminal cells that persist in the prostate after castration, not just rare stem cell populations.

These renewed insights in the diverse prostate cell populations, and their regenerative and proliferative potential, may ultimately settle also the ongoing debate regarding the precise prostate cell of origin for CaP. Transgenic mouse studies and tissue reconstitution experiments have indicated both basal and luminal cell populations may give rise to CaP (Strand and Goldstein, 2015, Goldstein and Witte, 2013), which appears consistent with the broadened regenerative potential observed among the newly characterized epithelial cell populations. To our knowledge, these first-in-field single cell transcriptomics studies have not yet systemically examined, compared and verified the proliferation indices or cell cycle progression rates in the diverse prostate epithelial cell populations. The latter information could be useful to clarify further the molecular prostate oncogenesis process. Non-malignant prostate tissue has a low proliferation rate, as assessed via immunohistochemical evaluation of proliferation markers such as Ki67 or PCNA (Wolf and Dittrich, 1992, Berges et al., 1995), and more recently, via the GTEX portal data of non-diseased tissue-specific gene expression (Consortium, 2020). Although the proliferation rate in newly diagnosed treatment-naïve CaP still remains relatively low, it is significantly increased compared to that of adjacent benign prostate tissues (Hammarsten et al., 2019, Berlin et al., 2017) and is higher in treatment-resistant than -naive CaP (Lobo et al., 2018, Berlin et al., 2017). The clinical importance of CaP proliferation rates is underscored by the routine quantification of proliferation markers such as Ki67, which values are directly correlated with prognosis, by GU pathologists. Of note, one of the commercially available genomic CaP prognosticators that are increasingly used to guide post-operative disease monitoring and treatment, the Prolaris test, also specifically measures expression of cell cycle proliferation genes (Shore et al., 2014).

However, systematic evaluation of the mechanism(s) that control cell proliferation and cell cycle progression during prostate carcinogenesis and CaP progression has, to our knowledge, not been done. Below, we start by reviewing the cell cycle and its disturbance during CaP progression and treatment resistance.

2.2. Cell cycle progression in CaP progression and treatment resistance

a. The basics of cell cycle regulation

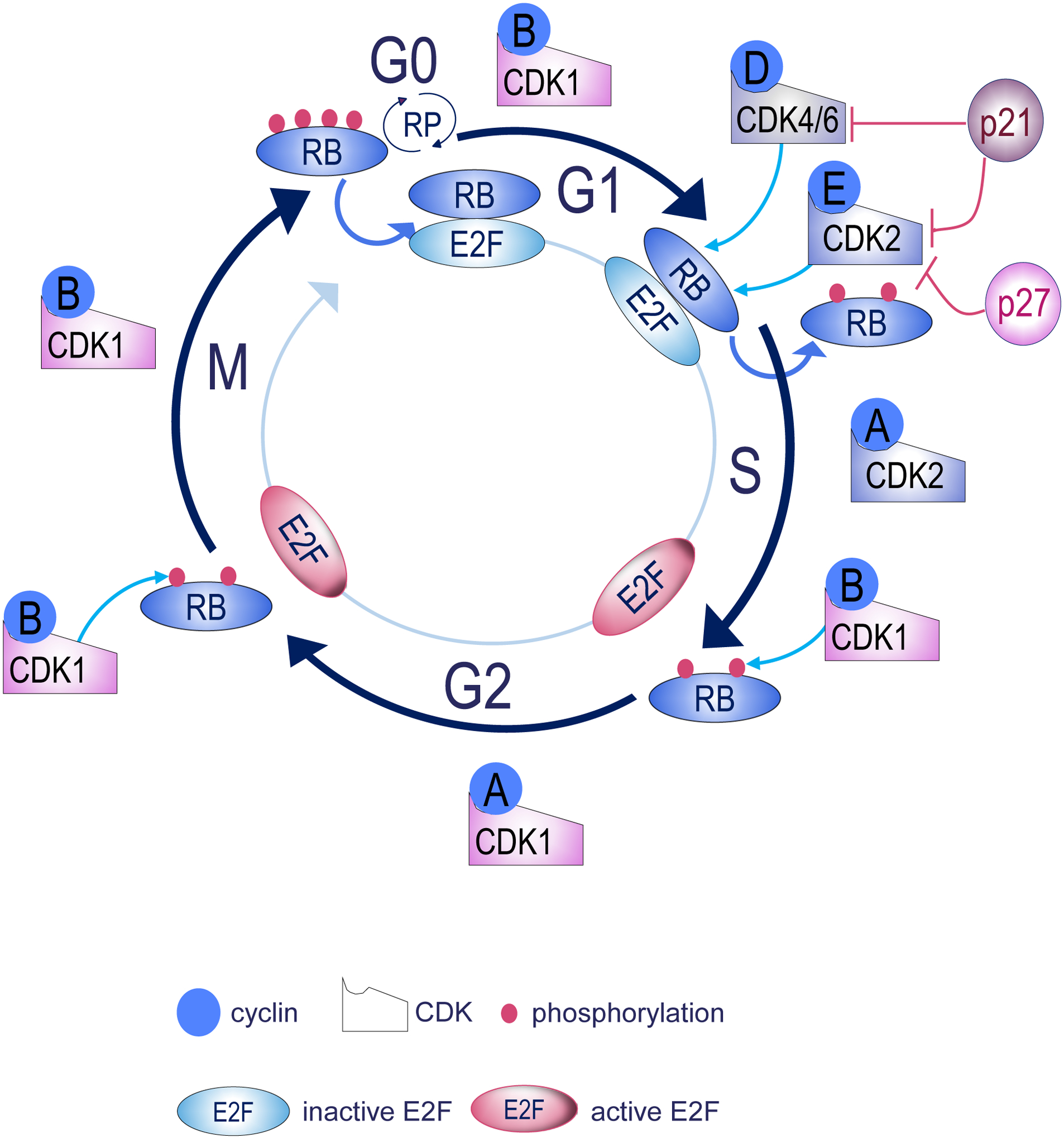

The eukaryotic cell cycle is divided into 2 major phases: the interphase, which proceeds in 3 stages (G1, S and G2) and the mitotic (M) phase, which includes mitosis and cytokinesis (Carlton et al., 2020, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007) (Figure 1). During interphase, the cell grows by accumulating nutrients that are needed for mitosis and replicates its DNA and some of its organelles. During the M phase, the cell replicates its chromosomes, organelles, which is followed by cytoplasm separation into 2 new daughter cells (Carlton et al., 2020, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007). To ensure the authentic replication of cellular components and correct cell division, control mechanisms known as cell cycle checkpoints are in place after each of the key steps of the cycle to determine whether the cell can or not progress to the next phase (Figure 1). Cell cycle control has been described in detail in numerous excellent reviews (Massague, 2004, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006), we will summarize only key steps below (Figure 1). The regulation of the cell cycle is driven by sequential expression of cyclins that activate specific cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) (Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). Starting in G1 phase, cyclin D is expressed in response to mitogenic signaling, which activates CDK4/6 leading to retinoblastoma protein (RB) phosphorylation (Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). This results in E2F release, which facilitates transcription of cyclin E and cyclin A that results in further RB phosphorylation. The activity of G1/S cyclin-cdk complexes is controlled by members of the cip-kip (p21cip1/waf1, p27kip1, and p57kip2) and INK4 (p16INK4a, p15INK4b, and p18INK4c) families of cdk inhibitors (Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). By binding to cyclin-cdk complexes, both families inhibit RB phosphorylation, prevent the release of E2F, and thereby arrest the replicative machinery. The second major event in the cell cycle is the entry to mitosis that is driven by cyclin B-CDK1 interactions (Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). Cyclin-B-CDK1 complexes continue to inhibit RB via phosphorylation at both S to G2 and G2 to M transition. Cyclin B is expressed and accumulated in G2 phase (Figure 1), binds and activates its catalytic partner CDK1 for nuclear import and generation of the mitotic spindle, chromosome condensation, and nuclear envelope breakdown (Satyanarayana and Kaldis, 2009, Sullivan and Morgan, 2007, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006). The hyperphosphorylation of RB drives cell passage through the restriction point where cell growth becomes independent from mitogenic signaling (Moser et al., 2018, Giacinti and Giordano, 2006).

Figure 1. Overview of cell cycle progression.

The cell cycle is regulated by the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), which are controlled by the availability of their binding partners from the cyclins family. During G1, Cyclins D and E are overexpressed, complex with their partner CDKs and phosphorylate RB. Phosphorylated RB releases E2F transcription factors which in turn activate genes required for S phase entry. Inhibition of RB is maintained by cyclin B-CDK1 during S-G2 and G2-M transitions. Cells exist the M phase after dephosphorylation of RB, which binds and inhibit E2F. During all cell cycle phases, CDK inhibitors (i.e p27, p21) govern proper transition by inhibiting CDKs function. RP, Restriction point, RB, Retinoblastoma.

b. Cell cycle dysregulation during CaP progression

i. Role of alterations in RB and E2F transcription factor function

The central protein in cell cycle regulation is RB as phosphorylation of RB induces cell division. RB’s prevention of tumor development relies in large part on its capacity to modulate activity of E2F family transcription factor activity, which controls the production of proteins that are important for cellular replication (Giacinti and Giordano, 2006, Moser et al., 2018, Chen et al., 2009). Under normal circumstances, unphosphorylated RB binds and thereby inhibits E2F family members (Sharma et al., 2007, Chen et al., 2009). Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at the RB locus is an early event that promotes the initiation and progression of CaP, and is significantly more prevalent in CRPC. RB loss causes acquired treatment resistance and emergence of NEPC (Knudsen and Knudsen, 2008, Macleod, 2010, Thangavel et al., 2017, Mandigo et al., 2020, Sharma et al., 2010, Zhou et al., 2006). Therefore, loss of RB function is associated with poor clinical outcome (Abida et al., 2019, Beltran et al., 2016, Beltran et al., 2013, Hamid et al., 2019, Taylor et al., 2010, Choudhury and Beltran, 2019). Moreover, restoration of wildtype RB in DU145 CaP cells that express a truncated short RB form, prevented these cells to form tumors in nude mice (Bookstein et al., 1990). Of note, some RB mutations can also alter the affinity for RB binding proteins such as E2F without affecting the level of RB expression (Kubota et al., 1995, Sun et al., 2011)

Consistent with these findings, levels of E2F1, the best-studied E2F family member in CaP, increased in the transition from benign prostate to localized CaP, to metastatic lymph nodes from treatment-naïve patients, and to CRPC (Pierce et al., 1998, Davis et al., 2006, Handle et al., 2019). Increased expression of E2F1 was associated with CaP growth, cell survival and treatment resistance (Davis et al., 2006, Handle et al., 2019). In a transgenic mice model, overexpression of E2F1 caused prostate hyperplasia (Pierce et al., 1998) while its loss in CaP xenograft models delayed CaP growth (Sun et al., 2011). Recently, a novel E2F1 cistrome was observed after RB loss that diverged considerably from the canonically described E2F1 binding patterns (McNair et al., 2018) after phosphorylation-induced RB functional inactivation, suggesting that RB loss might reprogram the E2F1 cistrome (McNair et al., 2018). In addition, in phosphoproteomic analysis of CRPC specimens, members of E2F family and their target genes were found to be significantly enriched (Drake et al., 2016) and in transcriptomics analyses of NEPC patient-derived xenografts and circulation tumor cell-derived explant models, E2F pathways were among upregulated pathways (Faugeroux et al., 2020, Lam et al., 2020), verifying the importance of E2F action for aggressive CaP progression.

ii. Cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinases

As indicated above, RB phosphorylation is controlled by cyclin-CDK complexes. Altered expression or activity of several of these key cell cycle regulators has been associated with CaP growth, metastasis, and treatment resistance (Balk and Knudsen, 2008, Choudhury and Beltran, 2019, Ku et al., 2017, Schiewer et al., 2012). Cyclin A, B, D and E expression was upregulated in treatment-naïve CaP tissues and p27 or p21 was downregulated or in rare instances subject to inactivating mutations (Mashal et al., 1996, Kuczyk et al., 2001, Bott et al., 2005, Fizazi et al., 2002, Comstock et al., 2007, Cordon-Cardo et al., 1998). While inactivating mutations in the INK4 cdk inhibitors family occur at very low rate in CaP (Park et al., 1997, Chi et al., 1997, Jarrard et al., 1997), hypermethylation of the promoter of p16INK4a that silences its expression has been reported in CaP and not in benign tissues (Chi et al., 1997, Jarrard et al., 1997). CDK1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 were upregulated in CaP, where their expression correlated with increasing Gleason score (Kallakury et al., 1997, Halvorsen et al., 2000, Gregory et al., 2001). For cyclin A, B and D, such overexpression in treatment-naïve CaP was significantly associated with proliferative index (Ki67) (Mashal et al., 1996) and tumor grade (Aaltomaa et al., 1999). Tissues from preclinical models and patient specimens support deregulated expression pattern of cyclins, CDKs and CDK inhibitors that favor cell cycle transitions during CRPC progression (Gregory et al., 1998, Gregory et al., 2001). Noteworthy, CaP progression in the TRAMP mouse model has been linked to a cyclin switch in which decrease in cyclin D expression is associated with an increase in cyclin E (Li et al., 2019), suggesting switches in cell cycle regulation during CaP progression. That the observed changes in expression or activation can cause differences in cell cycle progression was supported, for instance, by findings that loss of both p27 and p21 in DU145 accelerates G1-S phase transition (Roy et al., 2008).

iii. Role of AR

AR regulation of cell cycle

The core machinery that drives the cell cycle is well conserved among cell and tissue types although the signals that dictate commitment to the cell cycle are often cell type-specific. Androgen and AR activation have been recognized as such lineage-specific signals to drive growth in benign and malignant prostate glands (Arnold and Isaacs, 2002, Isaacs and Coffey, 1989, Isaacs, 1999). The increased proliferation rate in CaP compared to benign glands coincides with a shift in AR’s function from transcription factor only in normal gland to both transcription factor and DNA replication factor in CaP, and from paracrine stimulator of benign growth to autocrine growth regulator in CaP (Guedes et al., 2016, Li et al., 2008, Gao et al., 2001). In treatment-naïve localized CaP cells, AR has been reported as a master regulator of G1-S phase progression, able to induce signals that promote G1 cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity, induce phosphorylation/inactivation of RB, induce E2F activity and reduce p27 expression and thereby stimulate androgen-dependent CaP cell proliferation (McNair et al., 2017, Balk and Knudsen, 2008, Schiewer et al., 2012). AR remains a major regulator of CaP growth also in the majority of cases once one or more rounds of ADT have failed. Analyses of AR-dependent transcriptomes and cistromes have revealed a shift of AR control over G1-S checkpoint in treatment-naive CaP to G2-M checkpoints in CRPC (Wang et al., 2009). While AR remains expressed in a significant fraction of NEPC, these cancers have been deemed AR-indifferent; the remaining portion of NEPC is even AR-negative, reducing the likelihood of similar control of AR over cell cycle in this CaP phenotype.

Interactions between cell cycle regulators and AR

Several reports indicate also direct protein-protein interactions between AR and several cell cycle regulators, which may underlie AR’s involvement in cell cycle control. In addition to AR’s control over CDK and cyclin expression and activity, already referred to above, members of the cell cycle-related subfamily of CDKs such as CDK6 have been reported to bind directly to AR (Lim et al., 2005), and so have cyclins that are mostly relevant to cell cycle phase transition such as cyclin D (1 and 3) and cyclin E (Yamamoto et al., 2000, Knudsen et al., 1999, Reutens et al., 2001, Petre-Draviam et al., 2005, Petre-Draviam et al., 2003, Burd et al., 2005, Petre et al., 2002). Moreover, Rb1 has been described to directly interact with AR (Yeh et al., 1998, Lu and Danielsen, 1998). It should be noted that these studies were mostly done in the context of AR transcriptional regulation, i.e. they evaluated the coregulator and cofactor potential of cell cycle regulators to influence AR-dependent transcription (Heemers and Tindall, 2007, DePriest et al., 2016). Such transcriptional involvement is consistent with CDK and cyclin family members having either selective, dual or preferential roles in cell cycle control or transcriptional regulation (Malumbres, 2014). In this respect, transcription-related subfamily members such as CDK11, 7 and 9, and cyclin H have also been reported as coregulators modulating AR’s transcription output (Heemers and Tindall, 2007, DePriest et al., 2016).

Cell cycle regulation of AR

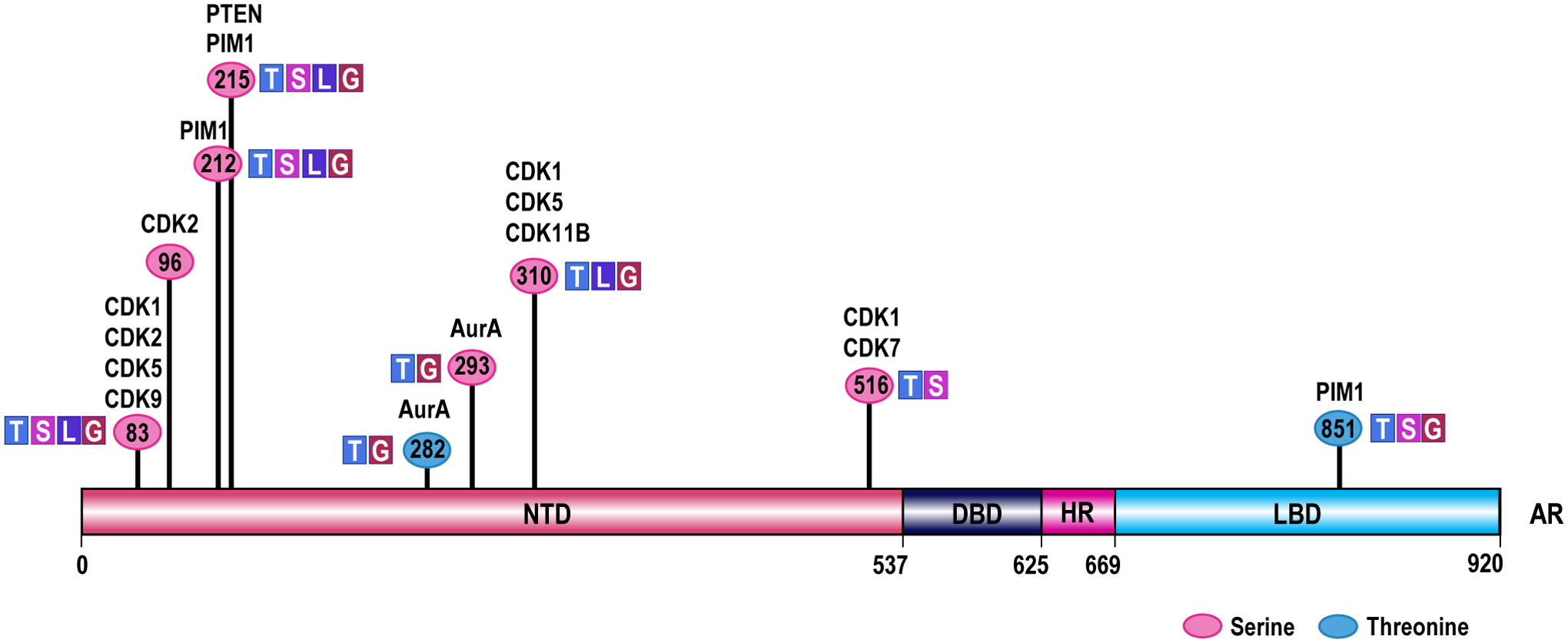

The interactions between AR and select cell cycle regulators suggest that the stage of the cell cycle may influence the transactivation function of AR. This possibility is supported by other lines of evidence. For instance, AR activation and stability is regulated by phosphorylation by cell cycle regulators: e.g. phosphorylation of AR on S83 by CDK1 enhances AR stability and transcriptional activity (Gordon et al., 2010, Chen et al., 2012); while AR phosphorylation on S310 by CDK 1, 5 and 11 represses AR transcriptional activity and alters its localization during mitosis (Gioeli et al., 2002, Koryakina et al., 2015, Lindqvist et al., 2015). These finding already suggest that CDKs that are not necessarily solely involved with cell cycle progression can modify these as well as other AR sites. Moreover, non-CDK cell cycle regulators such as Aurora A phosphorylate AR and impact its transcriptional output (Figure 2). These data also indicate the possibility of regulation of AR activity in the stage of cell cycle where an AR-modifying regulator is most expressed and/or active. Studies that specifically examined the influence of the stage of cell cycle on AR repression, AR nuclear localization and AR transcriptional output also have confirmed this possibility although some discrepancies, for instance in AR expression levels, were noted between different research groups. Indeed, while some have shown that AR levels are altered during cell cycle and peak during interphase while all but disappearing during mitosis (Litvinov et al., 2006), others have reported uniform, comparable AR levels during all stages of cell cycle (McNair et al., 2017). It will be important to reconcile such discrepancies; the experimental approaches used may already start to explain some of differences that were observed. For instance, one group analyzed unsynchronized cells in regular growth conditions that were sorted by flow cytometry based on their DNA content as an indicating of their cell cycle stage and then analyzed enriched fractions for AR expression via western blotting (Litvinov et al., 2006). The other team, however, used pharmacological interventions to arrest androgen-stimulated cells in specific cell cycle stage to examine AR expression and nuclear localization (McNair et al., 2017). Yet another group found that during G1/S transition, AR protein level is reduced due to enhanced E2F1 activity that represses AR transcription; the reduction in AR transcriptional activity was linked to an increase in cyclin D1 protein levels, an AR corepressor and RB hyper-phosphorylation (Martinez and Danielsen, 2002). In addition, even when AR expression levels were even throughout the cell cycle progression, differences in AR transcription function can exist between different cell cycle phases, as evidenced by a recent series of elegant and detailed transcriptome and cistrome analyses (McNair et al., 2017). In the latter study, CaP cells were arrested pharmacologically in early G1, late G1, early S, late S, or G2/M stage and gene expression analysis and AR-ChIP-Seq was done on cells enriched in each stage. These integrated analyses uncovered a set of AR target genes that was common to all phases of the cell cycle, and distinct sets of genes which were AR-responsive only in specific cell cycle phases. Pathway enrichment analyses confirmed differences in associated biology for these sets of AR target genes, for instance DNA repair and p53-regulated genes were upregulated exclusively in S and G2/M phases. The differences in AR target gene expression were reflected also in differential AR cofactor requirements throughout cell cycle, with specific transcription factor binding motifs present in cell-cycle specific AR binding peaks e.g. RUNX1 binding sites enriched exclusively in AR cistrome in late G1 stage (McNair et al., 2017). Some of these AR target genes or gene sets, for instance, dihydroceramide desaturase 1 that is primarily involved in the formation of ceramide can promote pro-metastatic phenotypes, associate with development of metastases, recurrence after therapeutic intervention and reduced overall survival. These studies delving into cell cycle regulation of AR action have been done mostly in models for treatment-naïve CaP, the extent to which results apply also to CRPC were cell cycle specific AR activity has not yet been examined but will be important to determine.

Figure 2. Schematic overview of sites of AR phosphorylation by cell cycle regulators.

Numbers indicate the AR amino acid residue that is phosphorylated. The functional implication of phosphorylations at these residues is indicated, and the cell cycle regulator responsible for phosphorylations at specific residues across AR’s functional domains is listed. Please note that the (updated) amino acid numbering system used in this figure and the associated manuscript section is based on NCBI reference sequence NM_000044.2. AR, Androgen Receptor; NTD, N-terminal transactivation domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; HR, hinge region; LBD, ligand binding domain; AurA, Aurora kinase A; CDK, cyclin dependent kinase; PIM1, proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase; PTEN, Phosphatase and tensin homolog; T, phosphorylation impacts AR transcription function; S, phosphorylation impacts AR stability; L, phosphorylation impacts AR localization; G, phosphorylation impacts CaP growth.

3. Other molecular events that contribute to regulation of CaP cell proliferation

The proteins discussed in the previous section are all well-characterized critical regulators of cell cycle progression. Expression of several of these growth regulators is subject to genomic alterations (e.g. RB, loss), which impact their function, during CaP progression. Other important modulators of CaP cell proliferation that may be less readily recognized as cell cycle regulators include for instance PLK1, whose overexpression has been linked to prostate tumorigenesis (Weichert et al., 2004, Deeraksa et al., 2013), or MYC, whose gene amplification drives CaP/NEPC progression (Ellwood-Yen et al., 2003, Kwon et al., 2020). The full scope of CaP cell cycle modulators and the extent to which somatic alterations impact their expression or function, and subsequently, clinical CaP progression and treatment response, has likely not yet been determined. Moreover, novel independent growth-regulatory mechanisms are emerging that involve e.g. gene methylation events or tissue microenvironmental changes, some of which are CaP stage-specific. In this section, we examine genomic alterations in genes whose products are well-known to (in)directly influence cell cycle progression, and review alternative, non-genomic mechanisms that influence CaP growth and treatment response.

a. Genomic events

During the past decade, thousands of clinical CaP specimens obtained at different stages of disease progression have been analyzed via whole exome/genome sequencing and/or copy number alteration assays. These studies have provided entirely novel insights into the genomic drivers of CaP progression, treatment resistance and lethality and have identified recurrent alterations, some present in a significant subset of CaP cases and others mutated at lower frequencies that follow a long-tail distribution (Armenia et al., 2018). Although these datasets have not been specifically analyzed for genomic events that impact genes in control over cell cycle and cell proliferation, they do confirm the well-known rate of TP53, PTEN, and MYC alterations, which are recurrent in CaP, well-recognized to influence cell proliferation via impact on cell cycle, and have been linked to treatment resistance and aggressive CaP progression (Dawson et al., 2020, Abida et al., 2019, Armenia et al., 2018, Robinson et al., 2015, Hamid et al., 2019).

TP53 alterations:

TP53 is a master regulator and the guardian of genomic integrity during cell cycle progression (Levine, 2020). TP53 expression is increased in response to cellular stresses that cause DNA damage. For instance, upon DNA-damage by radiation, TP53 halts the cell cycle at the G1 phase in part by transcriptionally activating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (Macleod et al., 1995). TP53 loss and missense gain-of function mutations, which suppress the p53 tumor suppressor function, are present in up to ~10 % of treatment-naïve localized CaP and up to half of CRPC and NECP specimens (Robinson et al., 2015, Cancer Genome Atlas Research, 2015).

PTEN alterations:

PTEN controls cell proliferation and survival by regulating G1/S and G2/M transitions. Cells lacking PTEN exhibit cell cycle deregulation and cell fate reprogramming. PTEN manifests its tumor suppressor function by inducing G1-phase cell cycle arrest by decreasing the level and nuclear localization of cyclin D1 (Radu et al., 2003), and regulating mitotic checkpoint complex formation during the cell cycle (Choi et al., 2017). Moreover, PTEN loss leads to activation of AKT pathway, which modulates a number of downstream targets, including mTOR signaling, that also have key roles in the regulation of cell cycle progression. Inactivation of PTEN by deletion or mutation is identified in significant subset (<20%) of treatment-naïve primary CaP samples at radical prostatectomy and in some studies in as many as ~50% of CRPC/NECP (Hamid et al., 2019, Wyatt et al., 2017, Ferraldeschi et al., 2015, Dawson et al., 2020, Abida et al., 2019).

Myc alterations:

MYC is a proto-oncogene and encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that plays a role in cell cycle progression through activation of cyclins, CDKs, E2F transcription factors and DNA replication genes and downregulation of cell cycle inhibitors such as p21 and p27 (Lin et al., 2012, Rahl et al., 2010, Herkert and Eilers, 2010, Dang et al., 2006). Amplification of the gene encoding MYC is frequently observed in human cancers ((Dang et al., 2006, Schaub et al., 2018). MYC is encoded by the 8q24 locus, which was first found to be amplified in human treatment-naïve localized CaP in 1986 (Fleming et al., 1986). MYC amplification and overexpression contribute to CaP progression, and have recently been recognized to be particularly important for NEPC development (Berger et al., 2019, Lee et al., 2016, Dardenne et al., 2016, Williams et al., 2005).

b. Non-genomic events

Transcriptional switches

Alterations in transcription factor (TF) function occur during lethal CaP progression, some of which impact cell cycle regulation. As mentioned, AR function shifts from preferential control over G1-S checkpoint in treatment-naïve CaP to regulation of G2-M phase transition in CRPC (Wang et al., 2009). Similarly, the RB loss that occurs during CaP progression alters the cistrome and transcriptome under control of the cell cycle-related TF E2F1(McNair et al., 2018). On the other hand, HOXB13 overexpression, which is tumorigenic in primary CaP, has emerged also as critical regulator of a mitotic kinase network that drives CRPC (Yao et al. 2019), while an increase in Hippo pathway effector Yes is observed during CRPC (but not NEPC) (Cheng et al., 2020, Kuser-Abali et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2015).

Epigenetic changes

Recurrent epigenetic alterations such as locus-specific DNA methylation at have been long-recognized in treatment-naïve localized CaP and their association with CaP progression was validated recently (Zhao et al., 2020). Several of these epigenetic events impact growth regulatory genes. For example, Ras association domain family member 1 (RASFF1) promoter methylation occurs in primary CaP and is maintained in CRPC (Liu et al., 2002). RASFF1 prevents cell proliferation by negative regulating of G1/S-phase transition of the cell cycle by reducing accumulation of cyclin D1 protein. Moreover, promoter hypermethylation of stratifin, which inhibit the cyclin B1–CD2 complex from entering the nucleus by enforcing a G2/M arrest was associated with CaP progression (Sing et al. 2017), and loss of Pygopus (Pygo) 2 chromatin effector enhances Myc oncogenic activity in CaP (Andrews et al. 2018).

Alternative splicing events

Alternative splicing events occur that impact CaP growth and progression via cell cycle. A recently reported example is the generation of AR variant 7 under the selective pressure of ADT, which then regulates a gene module enriched for mitotic cell cycle and chromosome segregation in CRPC (Magani et al. 2018). Conversely, the RNA binding protein Sam68 induces alternative splicing of cyclin D1, which is upregulated in CaP (Comstock et al., 2007, Paronetto et al., 2010).

Changes in the CaP micro-environment

Changes in the CaP micro-environment such as inflammation have long been recognized to contribute to CaP development by augmenting proliferation of normal prostate epithelial cells via differentially expressed macrophage-secreted cytokines including CCL3, IL-1ra, osteopontin, M-CSF1 and GDNF that activated ERK and Akt (Dang et al. 2018). Prostatic inflammation can incude loss of cell cycle inhibitors and decrease expression of tumor suppressors such as p27 in luminal cells, which is associated with higher proliferation index (De Marzo et al., 2007).

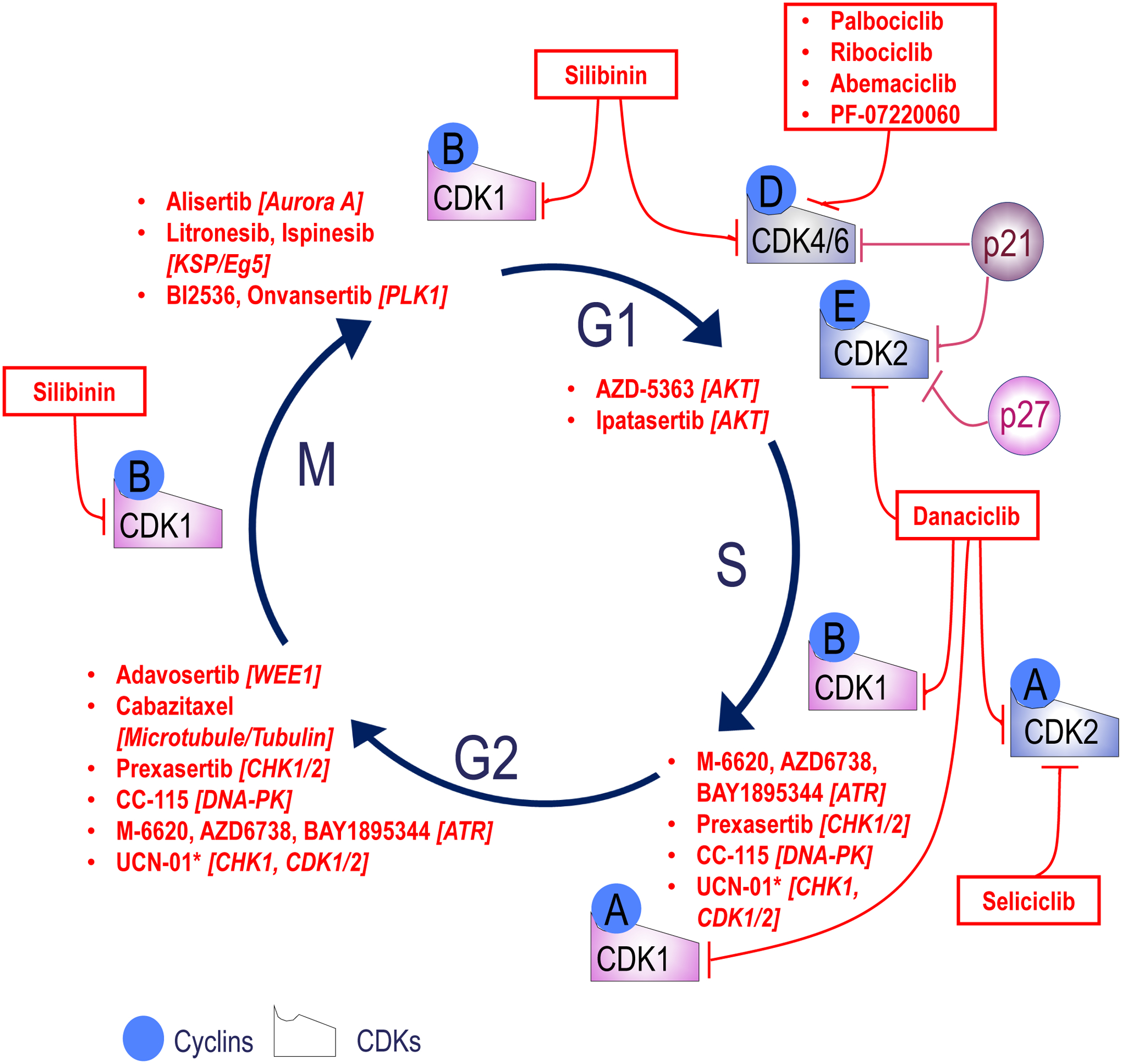

4. Therapeutic potential of targeting cell cycle regulators in CaP

Because of its central role in cancer progression, the cell cycle has long been viewed as a viable target for therapy (Otto and Sicinski, 2017, Whittaker et al., 2017). Pharmacologic intervention has focused on central regulators of cell cycle phase transitions, leading to development of inhibitors against CDK1 or CDK4/6 (Yan et al., 2020) - the latter are administered as standard of care in advanced breast cancer (Nagaraj and Ma, 2020). In CaP, preclinical studies on CDK4/6 inhibition have shown promise (Comstock et al., 2013), and the inhibitor palbociclip is currently tested in a phase 2 CRPC clinical trials (NCT02905318). Several other well-recognized cell cycle regulators harbor druggable moieties for which inhibitors have been developed that are being tested in clinical trials for CaP, sometimes in a stage-specific manner (Figure 3). These include CHK1/2 inhibitors (LY2606368, in CRPC, NCT02203513), Aurora kinase inhibitors (MLN8237, Alisertib, in NEPC, NCT01799278), and PLK1 inhibitors (BI2356, NCT00706498, or onvansertib, in CRPC, NCT03414034). In this respect, it is important to recognize that other, lesser known cell cycle regulators have been implicated in G1/S and G2/M phase transition or exhibited cell-cycle dependent protein expression (Supplemental Table 1) and may thus contribute to CaP progression or constitute previously unrecognized but viable targets for therapy (Liberzon et al., 2011) (Thul et al., 2017, Cho et al., 2001).

Figure 3. Overview of drugs targeting cell cycle regulators and in clinical trials for CaP treatment.

Targets for drugs are shown in italics between brackets. Data to generate the figure was obtained by searching the clinicaltrial.gov site for all prostate studies using the (cell cycle regulator) target as keyword. CDKs, cyclin dependent kinases; AKT, Protein kinase B; ATR, Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3 related; CHK, checkpoint kinase; DNA-PK, DNA-dependent protein kinase; WEE1, G2–M cell-cycle checkpoint kinase; Aurora A, serine/threonine kinase; KSP/Eg5, Kinesin spindle protein; PLK1, polo-like kinase 1; *, Multi-kinase inhibitor.

In many cases, interest for a cell cycle regulator as therapeutic target for CaP therapy was triggered by aberrant expression patterns. Recent genomic characterization of clinical CaP progression has identified several novel CaP and CRPC subtypes, sometimes because of alterations that affect genes relevant to cell cycle progression. For instance, recently a class of CDK12 mutant CRPC cases has been isolated that is associated with elevated neoantigen burden and increased tumor T cell infiltration/clonal expansion suggesting that mCRPC patients with CDK12 inactivation might benefit from immune checkpoint immunotherapy (Wu et al., 2018).

Somatic alterations impacting genes encoding cell cycle regulators may thus position as them as therapeutic targets or serve as predictive biomarker of responses to other treatments. These dual contributions already point towards the complexity and potential limitations of considering and targeting cell cycle regulator action for CaP treatments. That somatic alterations may also alter function of the affected gene (e.g. cyclin D splicing (Comstock et al., 2009)) or even hinder success of targeted therapies (e.g. EGFR (Linardou et al., 2009)) has been well-recognized. Somatic alterations, such as those assessed above, are increasingly characterized in patient’s CaP specimens to facilitate personalized cancer treatments, but do no capture or fully consider wild-type gene function that may be altered at the messenger of protein level, and can be asses via shRNA or CRISPR screens (e.g. (Tsherniak et al., 2017)). The choice of an appropriate regulator to target for therapy may warrant also additional information regarding contribution of target to embryogenesis and organ development and its basal expression status in normal tissues via the human protein atlas (protein) and GTEx tools (RNA). Such considerations may avoid subsequent therapeutic failures such as those encountered for CDK1 inhibitors: CDK1 appeared a perfect target that was a drugable, common essential cancer gene (Tsherniak et al., 2017) and cell-cycle specific CDK for which specific inhibitors could be developed that yielded encouraging preclinical results until they failed in cancer clinic/trials and were abandoned because of intolerable toxicities in highly proliferating benign tissues (Yan et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

Our updated overview of current insights in prostate cell types and their proliferative potential, with a focus on AR- or classical cell cycle regulator-dependent CaP cell proliferation, confirms that cell cycle progression is implicated in CaP progression and may represent a viable therapeutic target that remains incompletely understood. Mostly underappreciated interdependence between cell cycle components and AR, the major driver of CaP progression, was noted and emerging insights in previously unappreciated cell-cycle stage specific AR action were presented. Limitations and challenges encountered while targeting cell cycle regulators for cancer therapy were discussed, and supported the long-term possibility of mechanistically novel CaP treatment strategies. Such approaches are expected to benefit from the information on the CaP cell of origin derived from ongoing and future single cell characterization of prostate cell populations, and from a more complete characterization of the genomic heterogeneity that impacts the full complement of cell cycle regulators during CaP progression and treatment resistance.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Overview of memberships for 3 cell cycle-related gene signatures

Funding:

This work was supported the National Cancer Institute (grant number CA166440) and a VeloSano 5 pilot Research Award and a Falk Medical Research Trust Catalyst Award (to HVH).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: the authors declare no conflicting interests

References

- AALTOMAA S, ESKELINEN M & LIPPONEN P 1999. Expression of cyclin A and D proteins in prostate cancer and their relation to clinopathological variables and patient survival. Prostate, 38, 175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABIDA W, CYRTA J, HELLER G, PRANDI D, ARMENIA J, COLEMAN I, CIESLIK M, BENELLI M, ROBINSON D, VAN ALLEN EM, et al. 2019. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116, 11428–11436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APARICIO AM, HARZSTARK AL, CORN PG, WEN S, ARAUJO JC, TU SM, PAGLIARO LC, KIM J, MILLIKAN RE, RYAN C, et al. 2013. Platinum-based chemotherapy for variant castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 19, 3621–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARMENIA J, WANKOWICZ SAM, LIU D, GAO J, KUNDRA R, REZNIK E, CHATILA WK, CHAKRAVARTY D, HAN GC, COLEMAN I, et al. 2018. The long tail of oncogenic drivers in prostate cancer. Nat Genet, 50, 645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARNOLD JT & ISAACS JT 2002. Mechanisms involved in the progression of androgen-independent prostate cancers: it is not only the cancer cell’s fault. Endocr Relat Cancer, 9, 61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALK SP & KNUDSEN KE 2008. AR, the cell cycle, and prostate cancer. Nucl Recept Signal, 6, e001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELTRAN H, PRANDI D, MOSQUERA JM, BENELLI M, PUCA L, CYRTA J, MAROTZ C, GIANNOPOULOU E, CHAKRAVARTHI BV, VARAMBALLY S, et al. 2016. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med, 22, 298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELTRAN H, YELENSKY R, FRAMPTON GM, PARK K, DOWNING SR, MACDONALD TY, JAROSZ M, LIPSON D, TAGAWA ST, NANUS DM, et al. 2013. Targeted next-generation sequencing of advanced prostate cancer identifies potential therapeutic targets and disease heterogeneity. Eur Urol, 63, 920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGER A, BRADY NJ, BAREJA R, ROBINSON B, CONTEDUCA V, AUGELLO MA, PUCA L, AHMED A, DARDENNE E, LU X, et al. 2019. N-Myc-mediated epigenetic reprogramming drives lineage plasticity in advanced prostate cancer. J Clin Invest, 129, 3924–3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGES RR, VUKANOVIC J, EPSTEIN JI, CARMICHEL M, CISEK L, JOHNSON DE, VELTRI RW, WALSH PC & ISAACS JT 1995. Implication of cell kinetic changes during the progression of human prostatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 1, 473–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERLIN A, CASTRO-MESTA JF, RODRIGUEZ-ROMO L, HERNANDEZ-BARAJAS D, GONZALEZ-GUERRERO JF, RODRIGUEZ-FERNANDEZ IA, GONZALEZ-CONCHAS G, VERDINES-PEREZ A & VERA-BADILLO FE 2017. Prognostic role of Ki-67 score in localized prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol, 35, 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISHOP JL, THAPER D, VAHID S, DAVIES A, KETOLA K, KURUMA H, JAMA R, NIP KM, ANGELES A, JOHNSON F, et al. 2017. The Master Neural Transcription Factor BRN2 Is an Androgen Receptor-Suppressed Driver of Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov, 7, 54–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONKHOFF H & REMBERGER K 1996. Differentiation pathways and histogenetic aspects of normal and abnormal prostatic growth: a stem cell model. Prostate, 28, 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BONKHOFF H, STEIN U & REMBERGER K 1994. The proliferative function of basal cells in the normal and hyperplastic human prostate. Prostate, 24, 114–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOOKSTEIN R, SHEW JY, CHEN PL, SCULLY P & LEE WH 1990. Suppression of tumorigenicity of human prostate carcinoma cells by replacing a mutated RB gene. Science, 247, 712–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOTT SR, ARYA M, KIRBY RS & WILLIAMSON M 2005. p21WAF1/CIP1 gene is inactivated in metastatic prostatic cancer cell lines by promoter methylation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 8, 321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURD CJ, PETRE CE, MOGHADAM H, WILSON EM & KNUDSEN KE 2005. Cyclin D1 binding to the androgen receptor (AR) NH2-terminal domain inhibits activation function 2 association and reveals dual roles for AR corepression. Mol Endocrinol, 19, 607–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANCER GENOME ATLAS RESEARCH, N. 2015. The Molecular Taxonomy of Primary Prostate Cancer. Cell, 163, 1011–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARLTON JG, JONES H & EGGERT US 2020. Membrane and organelle dynamics during cell division. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 21, 151–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN HZ, TSAI SY & LEONE G 2009. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer, 9, 785–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN S, GULLA S, CAI C & BALK SP 2012. Androgen receptor serine 81 phosphorylation mediates chromatin binding and transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem, 287, 8571–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG S, PRIETO-DOMINGUEZ N, YANG S, CONNELLY ZM, STPIERRE S, RUSHING B, WATKINS A, SHI L, LAKEY M, BAIAMONTE LB, et al. 2020. The expression of YAP1 is increased in high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma but is reduced in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 23, 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHI SG, DEVERE WHITE RW, MUENZER JT & GUMERLOCK PH 1997. Frequent alteration of CDKN2 (p16(INK4A)/MTS1) expression in human primary prostate carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res, 3, 1889–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHO RJ, HUANG M, CAMPBELL MJ, DONG H, STEINMETZ L, SAPINOSO L, HAMPTON G, ELLEDGE SJ, DAVIS RW & LOCKHART DJ 2001. Transcriptional regulation and function during the human cell cycle. Nat Genet, 27, 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI BH, XIE S & DAI W 2017. PTEN is a negative regulator of mitotic checkpoint complex during the cell cycle. Exp Hematol Oncol, 6, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOUDHURY AD & BELTRAN H 2019. Retinoblastoma Loss in Cancer: Casting a Wider Net. Clin Cancer Res, 25, 4199–4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMSTOCK CE, AUGELLO MA, BENITO RP, KARCH J, TRAN TH, UTAMA FE, TINDALL EA, WANG Y, BURD CJ, GROH EM, et al. 2009. Cyclin D1 splice variants: polymorphism, risk, and isoform-specific regulation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 15, 5338–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMSTOCK CE, AUGELLO MA, GOODWIN JF, DE LEEUW R, SCHIEWER MJ, OSTRANDER WF JR., BURKHART RA, MCCLENDON AK, MCCUE PA, TRABULSI EJ, et al. 2013. Targeting cell cycle and hormone receptor pathways in cancer. Oncogene, 32, 5481–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMSTOCK CE, REVELO MP, BUNCHER CR & KNUDSEN KE 2007. Impact of differential cyclin D1 expression and localisation in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer, 96, 970–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONSORTIUM GT 2020. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science, 369, 1318–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORDON-CARDO C, KOFF A, DROBNJAK M, CAPODIECI P, OSMAN I, MILLARD SS, GAUDIN PB, FAZZARI M, ZHANG ZF, MASSAGUE J, et al. 1998. Distinct altered patterns of p27KIP1 gene expression in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst, 90, 1284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROWLEY L, CAMBULI F, APARICIO L, SHIBATA M, ROBINSON BD, XUAN S, LI W, HIBSHOOSH H, LODA M, RABADAN R, et al. 2020. A single-cell atlas of the mouse and human prostate reveals heterogeneity and conservation of epithelial progenitors. Elife, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAI C, HEEMERS H & SHARIFI N 2017. Androgen Signaling in Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANG CV, O’DONNELL KA, ZELLER KI, NGUYEN T, OSTHUS RC & LI F 2006. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin Cancer Biol, 16, 253–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DARDENNE E, BELTRAN H, BENELLI M, GAYVERT K, BERGER A, PUCA L, CYRTA J, SBONER A, NOORZAD Z, MACDONALD T, et al. 2016. N-Myc Induces an EZH2-Mediated Transcriptional Program Driving Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cancer Cell, 30, 563–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIES A, ZOUBEIDI A & SELTH LA 2020. The epigenetic and transcriptional landscape of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer, 27, R35–R50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS JN, WOJNO KJ, DAIGNAULT S, HOFER MD, KUEFER R, RUBIN MA & DAY ML 2006. Elevated E2F1 inhibits transcription of the androgen receptor in metastatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res, 66, 11897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON NA, ZIBELMAN M, LINDSAY T, FELDMAN RA, SAUL M, GATALICA Z, KORN WM & HEATH EI 2020. An Emerging Landscape for Canonical and Actionable Molecular Alterations in Primary and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther, 19, 1373–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE MARZO AM, PLATZ EA, SUTCLIFFE S, XU J, GRONBERG H, DRAKE CG, NAKAI Y, ISAACS WB & NELSON WG 2007. Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer, 7, 256–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEERAKSA A, PAN J, SHA Y, LIU XD, EISSA NT, LIN SH & YU-LEE LY 2013. Plk1 is upregulated in androgen-insensitive prostate cancer cells and its inhibition leads to necroptosis. Oncogene, 32, 2973–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENMEADE SR & ISAACS JT 2002. A history of prostate cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer, 2, 389–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEPRIEST AD, FIANDALO MV, SCHLANGER S, HEEMERS F, MOHLER JL, LIU S & HEEMERS HV 2016. Regulators of Androgen Action Resource: a one-stop shop for the comprehensive study of androgen receptor action. Database (Oxford), 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAKE JM, PAULL EO, GRAHAM NA, LEE JK, SMITH BA, TITZ B, STOYANOVA T, FALTERMEIER CM, UZUNANGELOV V, CARLIN DE, et al. 2016. Phosphoproteome Integration Reveals Patient-Specific Networks in Prostate Cancer. Cell, 166, 1041–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLWOOD-YEN K, GRAEBER TG, WONGVIPAT J, IRUELA-ARISPE ML, ZHANG J, MATUSIK R, THOMAS GV & SAWYERS CL 2003. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell, 4, 223–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAUGEROUX V, PAILLER E, OULHEN M, DEAS O, BRULLE-SOUMARE L, HERVIEU C, MARTY V, ALEXANDROVA K, ANDREE KC, STOECKLEIN NH, et al. 2020. Genetic characterization of a unique neuroendocrine transdifferentiation prostate circulating tumor cell-derived eXplant model. Nat Commun, 11, 1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEITELSON MA, ARZUMANYAN A, KULATHINAL RJ, BLAIN SW, HOLCOMBE RF, MAHAJNA J, MARINO M, MARTINEZ-CHANTAR ML, NAWROTH R, SANCHEZ-GARCIA I, et al. 2015. Sustained proliferation in cancer: Mechanisms and novel therapeutic targets. Semin Cancer Biol, 35 Suppl, S25–S54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERRALDESCHI R, NAVA RODRIGUES D, RIISNAES R, MIRANDA S, FIGUEIREDO I, RESCIGNO P, RAVI P, PEZARO C, OMLIN A, LORENTE D, et al. 2015. PTEN protein loss and clinical outcome from castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with abiraterone acetate. Eur Urol, 67, 795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIZAZI K, MARTINEZ LA, SIKES CR, JOHNSTON DA, STEPHENS LC, MCDONNELL TJ, LOGOTHETIS CJ, TRAPMAN J, PISTERS LL, ORDONEZ NG, et al. 2002. The association of p21((WAF-1/CIP1)) with progression to androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 8, 775–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLEMING WH, HAMEL A, MACDONALD R, RAMSEY E, PETTIGREW NM, JOHNSTON B, DODD JG & MATUSIK RJ 1986. Expression of the c-myc protooncogene in human prostatic carcinoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cancer Res, 46, 1535–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO J, ARNOLD JT & ISAACS JT 2001. Conversion from a paracrine to an autocrine mechanism of androgen-stimulated growth during malignant transformation of prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res, 61, 5038–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIACINTI C & GIORDANO A 2006. RB and cell cycle progression. Oncogene, 25, 5220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIOELI D, FICARRO SB, KWIEK JJ, AARONSON D, HANCOCK M, CATLING AD, WHITE FM, CHRISTIAN RE, SETTLAGE RE, SHABANOWITZ J, et al. 2002. Androgen receptor phosphorylation. Regulation and identification of the phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem, 277, 29304–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDSTEIN AS, LAWSON DA, CHENG D, SUN W, GARRAWAY IP & WITTE ON 2008. Trop2 identifies a subpopulation of murine and human prostate basal cells with stem cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105, 20882–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDSTEIN AS & WITTE ON 2013. Does the microenvironment influence the cell types of origin for prostate cancer? Genes Dev, 27, 1539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GORDON V, BHADEL S, WUNDERLICH W, ZHANG J, FICARRO SB, MOLLAH SA, SHABANOWITZ J, HUNT DF, XENARIOS I, HAHN WC, et al. 2010. CDK9 regulates AR promoter selectivity and cell growth through serine 81 phosphorylation. Mol Endocrinol, 24, 2267–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREGORY CW, HAMIL KG, KIM D, HALL SH, PRETLOW TG, MOHLER JL & FRENCH FS 1998. Androgen receptor expression in androgen-independent prostate cancer is associated with increased expression of androgen-regulated genes. Cancer Res, 58, 5718–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREGORY CW, JOHNSON RT JR., PRESNELL SC, MOHLER JL & FRENCH FS 2001. Androgen receptor regulation of G1 cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinase function in the CWR22 human prostate cancer xenograft. J Androl, 22, 537–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUEDES LB, MORAIS CL, ALMUTAIRI F, HAFFNER MC, ZHENG Q, ISAACS JT, ANTONARAKIS ES, LU C, TSAI H, LUO J, et al. 2016. Analytic Validation of RNA In Situ Hybridization (RISH) for AR and AR-V7 Expression in Human Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 22, 4651–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUO W, LI L, HE J, LIU Z, HAN M, LI F, XIA X, ZHANG X, ZHU Y, WEI Y, et al. 2020. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies a distinct luminal progenitor cell type in distal prostate invagination tips. Nat Genet, 52, 908–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALVORSEN OJ, HOSTMARK J, HAUKAAS S, HOISAETER PA & AKSLEN LA 2000. Prognostic significance of p16 and CDK4 proteins in localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 88, 416–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMID AA, GRAY KP, SHAW G, MACCONAILL LE, EVAN C, BERNARD B, LODA M, CORCORAN NM, VAN ALLEN EM, CHOUDHURY AD, et al. 2019. Compound Genomic Alterations of TP53, PTEN, and RB1 Tumor Suppressors in Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol, 76, 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMMARSTEN P, JOSEFSSON A, THYSELL E, LUNDHOLM M, HAGGLOF C, IGLESIAS-GATO D, FLORES-MORALES A, STATTIN P, EGEVAD L, GRANFORS T, et al. 2019. Immunoreactivity for prostate specific antigen and Ki67 differentiates subgroups of prostate cancer related to outcome. Mod Pathol, 32, 1310–1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANAHAN D & WEINBERG RA 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell, 144, 646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANDLE F, PREKOVIC S, HELSEN C, VAN DEN BROECK T, SMEETS E, MORIS L, EERLINGS R, KHARRAZ SE, URBANUCCI A, MILLS IG, et al. 2019. Drivers of AR indifferent anti-androgen resistance in prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep, 9, 13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEEMERS HV & TINDALL DJ 2007. Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: a diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr Rev, 28, 778–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENRY GH, MALEWSKA A, JOSEPH DB, MALLADI VS, LEE J, TORREALBA J, MAUCK RJ, GAHAN JC, RAJ GV, ROEHRBORN CG, et al. 2018. A Cellular Anatomy of the Normal Adult Human Prostate and Prostatic Urethra. Cell Rep, 25, 3530–3542 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERKERT B & EILERS M 2010. Transcriptional repression: the dark side of myc. Genes Cancer, 1, 580–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUDSON DL, GUY AT, FRY P, O’HARE MJ, WATT FM & MASTERS JR 2001. Epithelial cell differentiation pathways in the human prostate: identification of intermediate phenotypes by keratin expression. J Histochem Cytochem, 49, 271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISAACS JT 1999. The biology of hormone refractory prostate cancer. Why does it develop? Urol Clin North Am, 26, 263–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISAACS JT & COFFEY DS 1989. Etiology and disease process of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Prostate Suppl, 2, 33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAMES ND, SYDES MR, CLARKE NW, MASON MD, DEARNALEY DP, SPEARS MR, RITCHIE AW, PARKER CC, RUSSELL JM, ATTARD G, et al. 2016. Addition of docetaxel, zoledronic acid, or both to first-line long-term hormone therapy in prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): survival results from an adaptive, multiarm, multistage, platform randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 387, 1163–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARRARD DF, BOVA GS, EWING CM, PIN SS, NGUYEN SH, BAYLIN SB, CAIRNS P, SIDRANSKY D, HERMAN JG & ISAACS WB 1997. Deletional, mutational, and methylation analyses of CDKN2 (p16/MTS1) in primary and metastatic prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer, 19, 90–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KALLAKURY BV, SHEEHAN CE, AMBROS RA, FISHER HA, KAUFMAN RP JR. & ROSS JS 1997. The prognostic significance of p34cdc2 and cyclin D1 protein expression in prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer, 80, 753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANTOFF PW, HIGANO CS, SHORE ND, BERGER ER, SMALL EJ, PENSON DF, REDFERN CH, FERRARI AC, DREICER R, SIMS RB, et al. 2010. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med, 363, 411–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARTHAUS WR, HOFREE M, CHOI D, LINTON EL, TURKEKUL M, BEJNOOD A, CARVER B, GOPALAN A, ABIDA W, LAUDONE V, et al. 2020. Regenerative potential of prostate luminal cells revealed by single-cell analysis. Science, 368, 497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNUDSEN ES & KNUDSEN KE 2008. Tailoring to RB: tumour suppressor status and therapeutic response. Nat Rev Cancer, 8, 714–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNUDSEN KE, CAVENEE WK & ARDEN KC 1999. D-type cyclins complex with the androgen receptor and inhibit its transcriptional transactivation ability. Cancer Res, 59, 2297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KORYAKINA Y, KNUDSEN KE & GIOELI D 2015. Cell-cycle-dependent regulation of androgen receptor function. Endocr Relat Cancer, 22, 249–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KU SY, ROSARIO S, WANG Y, MU P, SESHADRI M, GOODRICH ZW, GOODRICH MM, LABBE DP, GOMEZ EC, WANG J, et al. 2017. Rb1 and Trp53 cooperate to suppress prostate cancer lineage plasticity, metastasis, and antiandrogen resistance. Science, 355, 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUBOTA Y, FUJINAMI K, UEMURA H, DOBASHI Y, MIYAMOTO H, IWASAKI Y, KITAMURA H & SHUIN T 1995. Retinoblastoma gene mutations in primary human prostate cancer. Prostate, 27, 314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUCZYK MA, BOKEMEYER C, HARTMANN J, SCHUBACH J, WALTER C, MACHTENS S, KNUCHEL R, KOLLMANNSBERGER C, JONAS U & SERTH J 2001. Predictive value of altered p27Kip1 and p21WAF/Cip1 protein expression for the clinical prognosis of patients with localized prostate cancer. Oncol Rep, 8, 1401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSER-ABALI G, ALPTEKIN A, LEWIS M, GARRAWAY IP & CINAR B 2015. YAP1 and AR interactions contribute to the switch from androgen-dependent to castration-resistant growth in prostate cancer. Nat Commun, 6, 8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWON OJ, ZHANG L, JIA D, ZHOU Z, LI Z, HAFFNER M, LEE JK, TRUE L, MORRISSEY C & XIN L 2020. De novo induction of lineage plasticity from human prostate luminal epithelial cells by activated AKT1 and c-Myc. Oncogene, 39, 7142–7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAM HM, NGUYEN HM, LABRECQUE MP, BROWN LG, COLEMAN IM, GULATI R, LAKELY B, SONDHEIM D, CHATTERJEE P, MARCK BT, et al. 2020. Durable Response of Enzalutamide-resistant Prostate Cancer to Supraphysiological Testosterone Is Associated with a Multifaceted Growth Suppression and Impaired DNA Damage Response Transcriptomic Program in Patient-derived Xenografts. Eur Urol, 77, 144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE JK, PHILLIPS JW, SMITH BA, PARK JW, STOYANOVA T, MCCAFFREY EF, BAERTSCH R, SOKOLOV A, MEYEROWITZ JG, MATHIS C, et al. 2016. N-Myc Drives Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Initiated from Human Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer Cell, 29, 536–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE AJ 2020. p53: 800 million years of evolution and 40 years of discovery. Nat Rev Cancer, 20, 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI T, WANG F, DANG Y, DONG J, ZHANG Y, ZHANG C, LIU P, GAO Y, WANG X, YANG S, et al. 2019. P21 and P27 promote tumorigenesis and progression via cell cycle acceleration in seminal vesicles of TRAMP mice. Int J Biol Sci, 15, 2198–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI Y, LI CX, YE H, CHEN F, MELAMED J, PENG Y, LIU J, WANG Z, TSOU HC, WEI J, et al. 2008. Decrease in stromal androgen receptor associates with androgen-independent disease and promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion. J Cell Mol Med, 12, 2790–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIBERZON A, SUBRAMANIAN A, PINCHBACK R, THORVALDSDOTTIR H, TAMAYO P & MESIROV JP 2011. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics, 27, 1739–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIM JT, MANSUKHANI M & WEINSTEIN IB 2005. Cyclin-dependent kinase 6 associates with the androgen receptor and enhances its transcriptional activity in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102, 5156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN CY, LOVÉN J, RAHL PB, PARANAL RM, BURGE CB, BRADNER JE, LEE TI & YOUNG RA 2012. Transcriptional amplification in tumor cells with elevated c-Myc. Cell, 151, 56–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINARDOU H, DAHABREH IJ, BAFALOUKOS D, KOSMIDIS P & MURRAY S 2009. Somatic EGFR mutations and efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 6, 352–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDQVIST J, IMANISHI SY, TORVALDSON E, MALINEN M, REMES M, ORN F, PALVIMO JJ & ERIKSSON JE 2015. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 acts as a critical determinant of AKT-dependent proliferation and regulates differential gene expression by the androgen receptor in prostate cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell, 26, 1971–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LITVINOV IV, VANDER GRIEND DJ, ANTONY L, DALRYMPLE S, DE MARZO AM, DRAKE CG & ISAACS JT 2006. Androgen receptor as a licensing factor for DNA replication in androgen-sensitive prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103, 15085–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU L, YOON JH, DAMMANN R & PFEIFER GP 2002. Frequent hypermethylation of the RASSF1A gene in prostate cancer. Oncogene, 21, 6835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOBO J, RODRIGUES A, ANTUNES L, GRACA I, RAMALHO-CARVALHO J, VIEIRA FQ, MARTINS AT, OLIVEIRA J, JERONIMO C & HENRIQUE R 2018. High immunoexpression of Ki67, EZH2, and SMYD3 in diagnostic prostate biopsies independently predicts outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol, 36, 161 e7–161 e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU J & DANIELSEN M 1998. Differential regulation of androgen and glucocorticoid receptors by retinoblastoma protein. J Biol Chem, 273, 31528–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLEOD KF 2010. The RB tumor suppressor: a gatekeeper to hormone independence in prostate cancer? J Clin Invest, 120, 4179–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACLEOD KF, SHERRY N, HANNON G, BEACH D, TOKINO T, KINZLER K, VOGELSTEIN B & JACKS T 1995. p53-dependent and independent expression of p21 during cell growth, differentiation, and DNA damage. Genes Dev, 9, 935–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALUMBRES M 2014. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol, 15, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANDIGO AC, MCNAIR C, KU K, PANG A, GUAN YF, HOLST J, BROWN M, KELLY WK & KNUDSEN KE 2020. Molecular underpinnings of RB status as a biomarker of poor outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38, 189–189. [Google Scholar]

- MARTINEZ ED & DANIELSEN M 2002. Loss of androgen receptor transcriptional activity at the G(1)/S transition. J Biol Chem, 277, 29719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASHAL RD, LESTER S, CORLESS C, RICHIE JP, CHANDRA R, PROPERT KJ & DUTTA A 1996. Expression of cell cycle-regulated proteins in prostate cancer. Cancer Res, 56, 4159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSAGUE J 2004. G1 cell-cycle control and cancer. Nature, 432, 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATEO J, CARREIRA S, SANDHU S, MIRANDA S, MOSSOP H, PEREZ-LOPEZ R, NAVA RODRIGUES D, ROBINSON D, OMLIN A, TUNARIU N, et al. 2015. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 373, 1697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCNAIR C, URBANUCCI A, COMSTOCK CE, AUGELLO MA, GOODWIN JF, LAUNCHBURY R, ZHAO SG, SCHIEWER MJ, ERTEL A, KARNES J, et al. 2017. Cell cycle-coupled expansion of AR activity promotes cancer progression. Oncogene, 36, 1655–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCNAIR C, XU K, MANDIGO AC, BENELLI M, LEIBY B, RODRIGUES D, LINDBERG J, GRONBERG H, CRESPO M, DE LAERE B, et al. 2018. Differential impact of RB status on E2F1 reprogramming in human cancer. J Clin Invest, 128, 341–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOSER J, MILLER I, CARTER D & SPENCER SL 2018. Control of the Restriction Point by Rb and p21. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 115, E8219–E8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGARAJ G & MA CX 2020. Clinical Challenges in the Management of Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Literature Review. Adv Ther. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OTTO T & SICINSKI P 2017. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 17, 93–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK DJ, WILCZYNSKI SP, PHAM EY, MILLER CW & KOEFFLER HP 1997. Molecular analysis of the INK4 family of genes in prostate carcinomas. J Urol, 157, 1995–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARONETTO MP, CAPPELLARI M, BUSA R, PEDROTTI S, VITALI R, COMSTOCK C, HYSLOP T, KNUDSEN KE & SETTE C 2010. Alternative splicing of the cyclin D1 proto-oncogene is regulated by the RNA-binding protein Sam68. Cancer Res, 70, 229–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRE-DRAVIAM CE, COOK SL, BURD CJ, MARSHALL TW, WETHERILL YB & KNUDSEN KE 2003. Specificity of cyclin D1 for androgen receptor regulation. Cancer Res, 63, 4903–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRE-DRAVIAM CE, WILLIAMS EB, BURD CJ, GLADDEN A, MOGHADAM H, MELLER J, DIEHL JA & KNUDSEN KE 2005. A central domain of cyclin D1 mediates nuclear receptor corepressor activity. Oncogene, 24, 431–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETRE CE, WETHERILL YB, DANIELSEN M & KNUDSEN KE 2002. Cyclin D1: mechanism and consequence of androgen receptor co-repressor activity. J Biol Chem, 277, 2207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERCE AM, FISHER SM, CONTI CJ & JOHNSON DG 1998. Deregulated expression of E2F1 induces hyperplasia and cooperates with ras in skin tumor development. Oncogene, 16, 1267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RADU A, NEUBAUER V, AKAGI T, HANAFUSA H & GEORGESCU MM 2003. PTEN induces cell cycle arrest by decreasing the level and nuclear localization of cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol, 23, 6139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAHL PB, LIN CY, SEILA AC, FLYNN RA, MCCUINE S, BURGE CB, SHARP PA & YOUNG RA 2010. c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell, 141, 432–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REUTENS AT, FU M, WANG C, ALBANESE C, MCPHAUL MJ, SUN Z, BALK SP, JANNE OA, PALVIMO JJ & PESTELL RG 2001. Cyclin D1 binds the androgen receptor and regulates hormone-dependent signaling in a p300/CBP-associated factor (P/CAF)-dependent manner. Mol Endocrinol, 15, 797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINSON D, VAN ALLEN EM, WU YM, SCHULTZ N, LONIGRO RJ, MOSQUERA JM, MONTGOMERY B, TAPLIN ME, PRITCHARD CC, ATTARD G, et al. 2015. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell, 161, 1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROY S, SINGH RP, AGARWAL C, SIRIWARDANA S, SCLAFANI R & AGARWAL R 2008. Downregulation of both p21/Cip1 and p27/Kip1 produces a more aggressive prostate cancer phenotype. Cell Cycle, 7, 1828–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SATYANARAYANA A & KALDIS P 2009. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene, 28, 2925–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAUB FX, DHANKANI V, BERGER AC, TRIVEDI M, RICHARDSON AB, SHAW R, ZHAO W, ZHANG X, VENTURA A, LIU Y, et al. 2018. Pan-cancer Alterations of the MYC Oncogene and Its Proximal Network across the Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell Syst, 6, 282–300.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIEWER MJ, AUGELLO MA & KNUDSEN KE 2012. The AR dependent cell cycle: mechanisms and cancer relevance. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 352, 34–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELMAN SH 2011. The McNeal prostate: a review. Urology, 78, 1224–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA A, COMSTOCK CE, KNUDSEN ES, CAO KH, HESS-WILSON JK, MOREY LM, BARRERA J & KNUDSEN KE 2007. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor status is a critical determinant of therapeutic response in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res, 67, 6192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARMA A, YEOW WS, ERTEL A, COLEMAN I, CLEGG N, THANGAVEL C, MORRISSEY C, ZHANG X, COMSTOCK CE, WITKIEWICZ AK, et al. 2010. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor controls androgen signaling and human prostate cancer progression. J Clin Invest, 120, 4478–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE N, CONCEPCION R, SALTZSTEIN D, LUCIA MS, VAN BREDA A, WELBOURN W, LEWINE N, GUSTAVSEN G, POTHIER K & BRAWER MK 2014. Clinical utility of a biopsy-based cell cycle gene expression assay in localized prostate cancer. Curr Med Res Opin, 30, 547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIEGEL RL, MILLER KD & JEMAL A 2020. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin, 70, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRAND DW & GOLDSTEIN AS 2015. The many ways to make a luminal cell and a prostate cancer cell. Endocr Relat Cancer, 22, T187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN M & MORGAN DO 2007. Finishing mitosis, one step at a time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 8, 894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN H, WANG Y, CHINNAM M, ZHANG X, HAYWARD SW, FOSTER BA, NIKITIN AY, WILLS M & GOODRICH DW 2011. E2f binding-deficient Rb1 protein suppresses prostate tumor progression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108, 704–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWEENEY CJ 2019. Time for an Integrated Global Strategy to Decrease Deaths from Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Focus, 5, 111–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWEENEY CJ, CHEN YH, CARDUCCI M, LIU G, JARRARD DF, EISENBERGER M, WONG YN, HAHN N, KOHLI M, COONEY MM, et al. 2015. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med, 373, 737–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR BS, SCHULTZ N, HIERONYMUS H, GOPALAN A, XIAO Y, CARVER BS, ARORA VK, KAUSHIK P, CERAMI E, REVA B, et al. 2010. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell, 18, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THANGAVEL C, BOOPATHI E, LIU Y, HABER A, ERTEL A, BHARDWAJ A, ADDYA S, WILLIAMS N, CIMENT SJ, COTZIA P, et al. 2017. RB Loss Promotes Prostate Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res, 77, 982–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THUL PJ, AKESSON L, WIKING M, MAHDESSIAN D, GELADAKI A, AIT BLAL H, ALM T, ASPLUND A, BJORK L, BRECKELS LM, et al. 2017. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science, 356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSHERNIAK A, VAZQUEZ F, MONTGOMERY PG, WEIR BA, KRYUKOV G, COWLEY GS, GILL S, HARRINGTON WF, PANTEL S, KRILL-BURGER JM, et al. 2017. Defining a Cancer Dependency Map. Cell, 170, 564–576 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERZE P, CAI T & LORENZETTI S 2016. The role of the prostate in male fertility, health and disease. Nat Rev Urol, 13, 379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Q, LI W, ZHANG Y, YUAN X, XU K, YU J, CHEN Z, BEROUKHIM R, WANG H, LUPIEN M, et al. 2009. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell, 138, 245–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARE JL 1994. Prostate cancer progression. Implications of histopathology. Am J Pathol, 145, 983–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATSON PA, ARORA VK & SAWYERS CL 2015. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, 15, 701–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEICHERT W, SCHMIDT M, GEKELER V, DENKERT C, STEPHAN C, JUNG K, LOENING S, DIETEL M & KRISTIANSEN G 2004. Polo-like kinase 1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and linked to higher tumor grades. Prostate, 60, 240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]