Abstract

Sugammadex is a steroid binder and can potentially bind the estrogens and progestins contained within hormonal contraception. Therefore, the FDA label for sugammadex contains a drug-drug interaction warning between this medication and hormonal contraception, advising that women taking hormonal contraception use a back-up contraceptive method or abstinence for seven days after exposure to sugammadex. However, given concerns that this warning may not be appropriately provided to at-risk patients, we conducted a retrospective chart review to identify women administered sugammadex while using hormonal contraception to identify documented counseling on this drug-drug interaction prior to implementation of a formalized counseling process. We reviewed 1000 randomly selected charts from the University of Colorado Hospital between January 2016 and December 2017. We identified 134 women using hormonal contraception at the time of sugammadex exposure; only one patient (0.7%, 95% CI 0.0, 4.1) had documented counseling. One patient had an unintended pregnancy within the same cycle as her exposure to sugammadex. Improved counseling processes are needed to avoid unnecessary risk for unintended pregnancies.

Keywords: sugammadex, hormonal contraception, drug interaction

Introduction

Reproductive aged women undergoing surgery not only face the routine risks and obstacles, but must also contend with managing their contraception in the pre and post-operative periods. A little less than half of all unintended pregnancies occur in women using contraception with the most commonly used hormonal contraceptive method in the US (combined hormonal contraceptive pills) having a failure rate of 7% in the general population [1–3]. Potential pre-operative causes of contraceptive failures include missing pills, stopping hormonal contraceptives per surgical team preference, and now sugammadex. In 2015, sugammadex (Bridion®, Merck & Co., Whitehouse Station NJ) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a new method of reversing neuromuscular blockade at the time of surgery [4,5]. The FDA label for sugammadex contains a drug-drug interaction warning between this medication and hormonal contraception [4,6]. Sugammadex is a steroid binder and can potentially bind the estrogens and progestins contained within hormonal contraception. This can lead to increased clearance of these steroid hormones and the FDA label specifically mentions the binding and lowering of plasma progesterone concentrations [6,7]. The label advises that women taking hormonal contraception use a back-up contraceptive method or abstinence for 7 days after exposure to sugammadex [7].

Despite this advisory, the questions of who should be counseling women about this drug-drug interaction and how counseling should be done remain unanswered [8,9]. As anesthesiologists administer sugammadex, the counseling responsibility may reasonably fall to them, but the surgeons that reconcile medications pre- and post-operatively are not necessarily exempt from addressing this drug-drug interaction. Some institutions have implemented an official consent form for this drug-drug interaction that all women must sign prior to surgery and at least one institution in the US (University of Michigan) has a publicly available post-operative discharge instruction sheet to educate patients on this drug-drug interaction [8–10]. However, many institutions have not developed a formalized process to address this counseling requirement and it is unknown if anesthesiologists or surgeons take personal initiative to provide this counseling without a formalized process. We wanted to assess if patients at a large, academic hospital where sugammadex is administered as a first-line neuromuscular blockade reversal agent were receiving any form of documented counseling on this drug-drug interaction and the potential risk for unintended pregnancy prior to the implementation of any formalized consent process.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, retrospective chart review of all reproductive aged (18–45 years) women undergoing outpatient or inpatient surgery at the University of Colorado Hospital between January 2016 and December 2017. Sugammadex was placed on our institution’s formulary in April 2016 and quickly became first line therapy for neuromuscular blockade reversal. By January 2018, all patients receiving sugammadex during their admission automatically had a standardized medication alert added to their discharge instructions in our electronic medical record (EMR). This alert advised patients on the interaction between sugammadex and hormonal contraception, including the need for 7 days of back-up contraception [7]. Prior to this automatic alert, there was no standardized process for counseling patients on this drug-drug interaction. Patients were included in the chart review if they had documented sugammadex administration during their surgical admission. Patients were assigned a random number by an uninvolved third party and we reviewed the first 1,000 patient charts based on this numbering. For patients with multiple surgeries with sugammadex administration, we reviewed only the earliest surgical admission.

We excluded patients who had no documented contraceptive method at the time of their surgical admission, were using a reliable, non-hormonal contraceptive method (i.e. copper intrauterine device), or were sterilized or undergoing an immediately-effective sterilization procedure. For patients using hormonal contraception at the time of sugammadex exposure, we reviewed the EMR to look for any pre- or post-operative counseling regarding this drug-drug interaction. We reviewed all documentation by both the anesthesia and surgical teams for counseling documentation. For patients with follow-up, we reviewed the records for three months after sugammadex exposure to identify any unintended pregnancies.

We performed descriptive analyses on the extracted data and calculated a two-sided 95% confidence interval for the percentage of patients with documented counseling. We used the Clopper-Pearson method to calculate exact binomial confidence intervals. Assuming that at least 10% of patients would meet our inclusion criteria and expecting 0% to have documented counseling, reviewing 1000 charts would allow us to say with at least 95% confidence that the actual percentage of patients with documented counseling was less than 5%. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board as a quality assessment project. These findings may not be generalizable to outside our academic hospital. This manuscript adheres to applicable STROBE guidelines, which are recommendations regarding the reporting of observational studies to ensure appropriate presentation of research methodology and interpretation [11].

Results

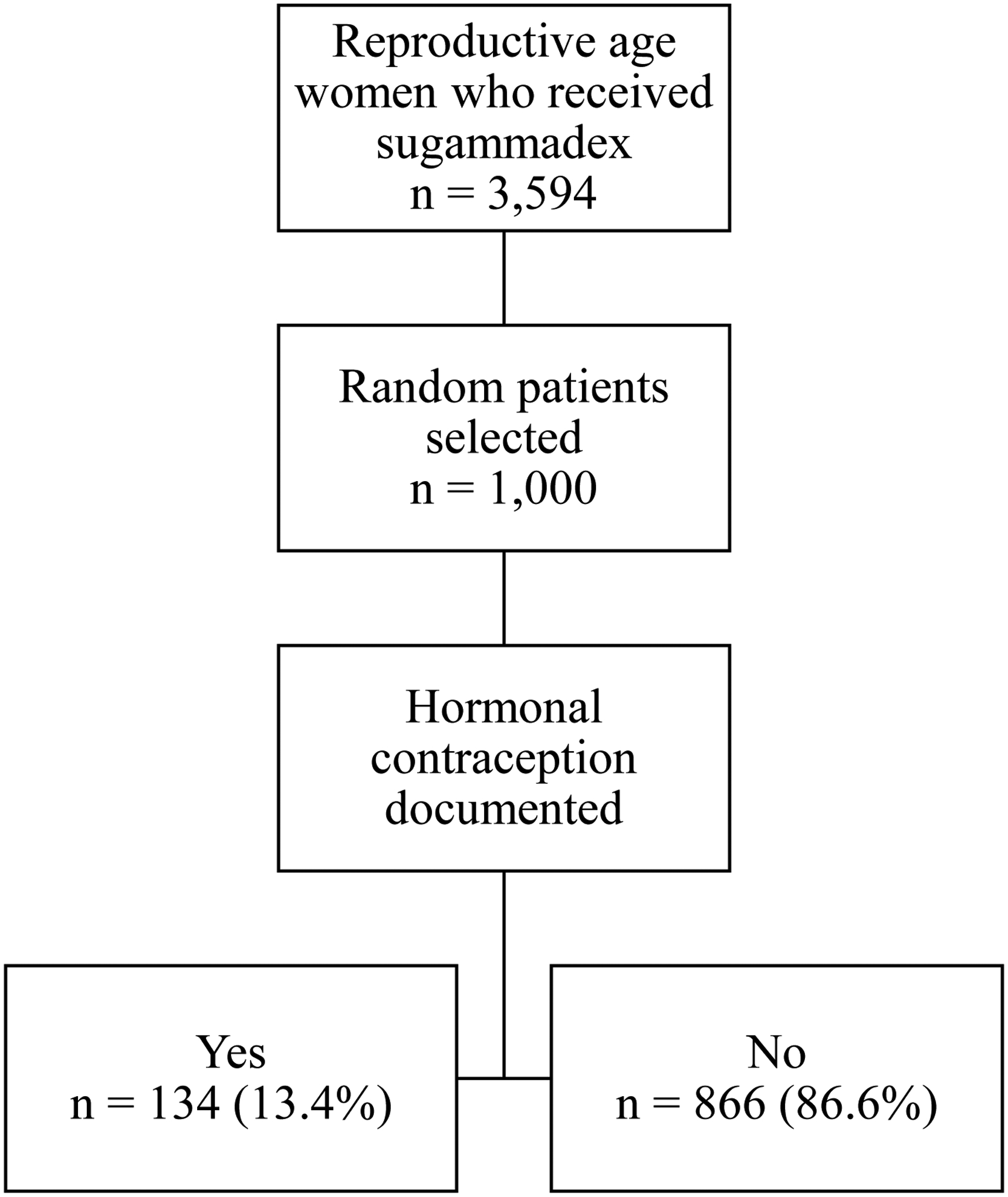

In the two-year period for this chart review, 3,594 reproductive-aged women received sugammadex at the University of Colorado Hospital. For the 1,000 charts reviewed, the median age was 35 years (range 18–45) and the median sugammadex dose was 100mg (range 3–430). Of these, 134 (13.4%) patients were using hormonal contraception at the time of sugammadex administration. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of retrospective chart review for reproductive age women (18–45 years) who received sugammadex during a surgical encounter at the University of Colorado Hospital between January 2016 and December 2017.

The majority of women (54.5%, 73/134) were taking a combined hormonal contraceptive pill at the time of their surgery. The frequency of hormonal contraceptive methods used is presented in Table 1. Patients primarily underwent surgery with a General Surgery (23.9%) or Orthopedic Surgery (17.9%) team. The full list of surgical services is available in Table 1.

Table 1:

Hormonal contraceptives used at the time of surgery and primary surgical team (n=134).

| Contraceptive method | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Combined hormonal contraceptive methods | |

| Combined oral contraceptive pills | 73 (54.5) |

| Contraceptive vaginal ring | 3 (2.2) |

| Contraceptive patch | 2 (1.5) |

| Progestin-only contraceptive methods | |

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device | 28 (20.9) |

| Etonogestrel contraceptive implant | 15 (11.2) |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection | 10 (7.5) |

| Progestin-only pills | 3 (2.2) |

| Surgical Team | |

| General Surgery | 32 (23.9) |

| Orthopedic Surgery | 24 (17.9) |

| Otolaryngology Surgery | 21 (15.7) |

| Obstetrics and Gynecologic Surgery | 18 (13.4) |

| Neurosurgery | 10 (7.5) |

| Gastrointestinal Surgery | 8 (6.0) |

| Plastic Surgery | 6 (4.5) |

| Transplant Surgery | 5 (3.7) |

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 5 (3.7) |

| Urologic Surgery | 1 (0.7) |

| Ophthalmologic Surgery | 1 (0.7) |

No patients had documented counseling on the interaction between sugammadex and hormonal contraception in any pre or post-operative documentation by their surgical team (0.0%, two-sided 95% CI 0.0, 2.7). One patient had documented counseling performed by the anesthesia team (0.7%, two-sided 95% CI 0.0, 4.1). The vast majority of patients (98.5%, 132/134) had at least one post-operative follow-up in our EMR. One patient had a documented pregnancy within three months of sugammadex administration. This patient was using combined hormonal contraceptive pills at the time of her surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy) and had a negative urine pregnancy test on the day of surgery. She had no documented counseling on this drug-drug interaction in her EMR. Her estimated date of conception was 19 days after surgery based upon a dating ultrasound performed at 8 weeks gestational age. She had an unsure last menstrual period, thus the pregnancy was dated by this ultrasound. At her prenatal intake, she stated that the pregnancy was the result of a birth control failure.

Discussion

At a large, academic institution, less than 1% of women using hormonal contraception had appropriate documentation of counseling regarding the interaction between sugammadex and their contraceptive method. Without documentation that patients were counseled on this drug-drug interaction, we must assume from a medicolegal perspective that the counseling did not occur. We found one unintended pregnancy that occurred in a patient taking combined oral contraceptive pills and within the same cycle as her exposure to sugammadex. We do not know if this pregnancy occurred solely due to this drug-drug interaction and not due to other factors (e.g. compliance in taking her pills), as the typical use failure rate of oral contraceptive pills is 7% in the general population [3]. However, the patient believed the pregnancy to be a result of birth control failure and sugammadex exposure cannot be ruled out as a factor.

This study’s major limitation is its lack of generalizability to all healthcare settings, as it was a quality assessment for one institution. This was also a retrospective chart review reliant on documentation of counseling by the surgical or anesthesia team. However, without documentation of counseling or consent in the EMR, one should be concerned that counseling did not occur. Though the measure of documented counseling may not represent the rate of actual counseling, there is no way to determine the correlation between the two in this retrospective review. At the time of this review, no regulatory authorities or medical societies in the US have provided guidance on the best approach or timing for this counseling, which potentially contributes to the lack of standard practices across institutions. Additionally, reasonable alternatives to sugammadex for neuromuscular blockade reversal (i.e. acetylcholinesterase inhibitors) remain readily available and clinicians may need to consider use of these alternatives in reproductive-age women taking hormonal contraception [5,9].

Even though all female patients who receive sugammadex at our institution as of January 2018 have a discharge medication alert similar to other institutions, what constitutes full disclosure in this specific healthcare situation remains unstandardized, as consent processes range from stringent written informed consent signed by both the patient and healthcare provider to simple discharge instructions advising patients of this drug-drug interaction [6,9,10]. Furthermore, the severity of this drug-drug interaction has no currently published pharmacokinetic data, including to what extent sugammadex affects long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (e.g. levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device, etonogestrel contraceptive implant) [4]. More research on the pharmacokinetic interaction between sugammadex and different hormonal contraceptive methods is needed to determine the actual risk for contraceptive failure. Until that research is available, both anesthesiologists and surgeons should follow the counseling recommendations included in the sugammadex drug label including clearly documenting that either consent or counseling has occurred to avoid any unnecessary risk for unintended pregnancy.

Conflicts of interest statement:

Dr. Aaron Lazorwitz has received research funding from Merck and Co. for an Investigator Initiated Study on drug-drug interactions with the etonogestrel contraceptive implant.

The University of Colorado Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology has received research funding from Bayer, Agile Therapeutics, Sebela, Merck and Co, and Medicines360.

Eva Dindinger has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Natasha Aguirre has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Jeanelle Sheeder has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethical information: This project was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board as a quality assessment project and the requirement for written informed consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board.

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Finer LB and Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2991. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(2):90–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. NCHS data brief. 2014(173):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Kowal D, Policar MS. Contraceptive technology. New York: Ardent Media. Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mornar S, Chan LN, Mistretta S, Neustadt A, Martins S, Gilliam M. Pharmacokinetics of the etonogestrel contraceptive implant in obese women. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2012;207(2):110.e111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keating GM. Sugammadex: A Review of Neuromuscular Blockade Reversal. Drugs. 2016;76(10):1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams R, Bryant H. Sugammadex advice for women of childbearing age. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(1):133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration Prescribing Information: Bridion (sugammadex). Reference ID: 3860969. Revised: December/2015.

- 8.Corda DM, Robards CB. Sugammadex and Oral Contraceptives: Is It Time for a Revision of the Anesthesia Informed Consent? Anesth Analg. 2018;126(2):730–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webber AM, Kreso M. Informed Consent for Sugammadex and Oral Contraceptives: Through the Looking Glass. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(3):e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman J Birth Control Drug Interaction with Sugammadex (Bridion®) and/or Aprepitant (Emend®): Information for Female Surgery Patients. 2016; Patient Education by University of Michigan Health System: Department of Anesthesiology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007;370(9596):1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]