“A victory for science!” Who could possibly disagree with Christel van Geet, Vice-Rector of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Leuven? She was opening a symposium about the defence of rationality during the COVID-19 pandemic, held at the University of Sorbonne, Paris, last week. Jean-François Delfraissy, President of France's COVID-19 Scientific Council, called COVID-19 vaccines a “miracle”. The Rector of the University of Geneva, Yves Flückiger, described the contribution of science to the pandemic as “spectacular”. But before we drown in a sea of self-congratulation, it might be worth listening to how others see us. Barbara Katz Rothman, Professor of Sociology at the City University of New York, has written a lacerating challenge—The Biomedical Empire: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic—to those who are tempted to think that science has been such an untrammelled public good.

© 2021 pointbreak/Shutterstock

Her starting point is the notion of “biomedical imperialism”. Biomedicine is today's “ruling empire, colonising the planet”, and we are its citizens. Rothman doesn’t deny that biomedicine has saved lives during the pandemic. But her concern is the growing power of biomedicine in society. Biomedicine has transcended the power of the nation-state. It has “conquered all nation-states”. By empire, Rothman means three separate but linked elements. First, biomedicine as economic power. Its economic force “has left us with no mechanisms other than profit to do something presumably all human beings want done” anyway. Second, biomedicine as governmental power. Biomedicine has become “a colonising form of government” that needs to be restrained. And third, biomedicine as religious power—“when you violate its tenets or do not participate in its rites, you are treated as a heretic”. Rothman goes as far as to suggest that biomedicine is “an evil empire running in its own interests”. She identifies the root cause as today's version of capitalism, which “cannot expand without the constant recreation of needs…and focusing on health, vitality, and longevity are probably the most irresistible of needs”. Here lies the great limitation of the biomedical empire—that its success depends on exploiting existing wants and divisions in society. Biomedicine has colluded with our obsession with the individual over society, with the “endless expansion of risk”, and the demand to eliminate these risks. So what, you might ask? As long as biomedicine delivers its promise—diagnostics, medicines, vaccines—what have critics to complain about? The answer is that something has been lost and “the word care sums it up”. Health and health care in the biomedical empire have come to mean medical services, “very individualised and very professionalised”.

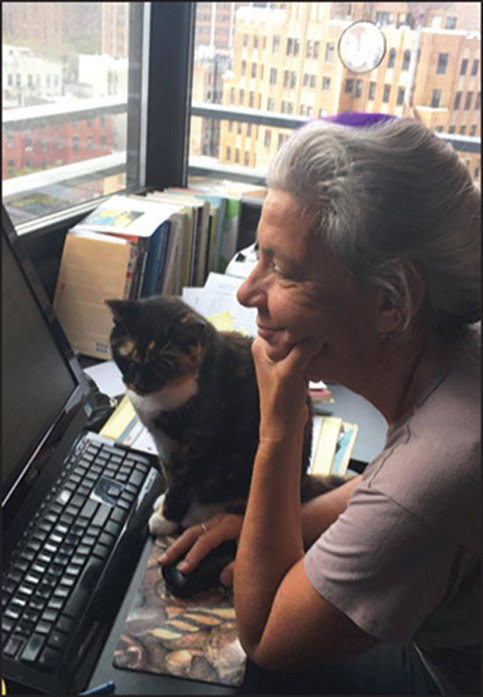

© 2021 Daniel Colb Rothman

How should society address the over-reach of the biomedical empire? Redefine medicine and medical science to include the social as well as the individual world. This call isn’t new—the notion of COVID-19 as a syndemic rather than a pandemic names poverty and inequality as core determinants of its consequences. But her indictment of hospitals as “essentially factories, processing people through procedures” does sting. She is correct that the biomedical empire led “people to do things that are mean, that do hurt”. Patients were isolated from families. The humanising touches in medicine so necessary to survive “were not understood as central to the services and mission of the hospital” during the pandemic. Indeed, in societies that did not value care, hospitals during the pandemic actually made care worse—overcrowding, stress, diminished access, suffering and dying alone, and the “warehousing of people”. This erosion of care was always worse for women and people of colour. I can imagine that some of my medical colleagues, who have worked so hard during the pandemic, will reject these arguments, perhaps with irritation. But Rothman is not attacking individual doctors or scientists. Instead, she is diagnosing a system where health “is not randomly distributed but very much a product of a social world”. She is attacking a system that operates outside the control of national citizenships and whose objective is to protect and augment its own economic interests. She is calling for a system that privileges care and brings that care out of the hospital and closer to home. Rothman's conclusion feels like a desperate plea—“There must be a way to put both health and care back into healthcare.” It is a plea that we citizens of the biomedical empire should heed.

© 2021 faboi/Shutterstock