Abstract

Objective:

We sought to characterize caregiver medication assistance for older adults with multiple chronic conditions.

Design:

Semi-structured qualitative interviews.

Setting:

Community and academic-affiliated primary care practices.

Participants:

A total of 25 caregivers to older adults participating in an ongoing cohort study with ≥3 chronic conditions.

Measurements:

A semi-structured interview guide, informed by the Medication Self-Management model, aimed to understand health-related and medication-specific assistance caregivers provided.

Results:

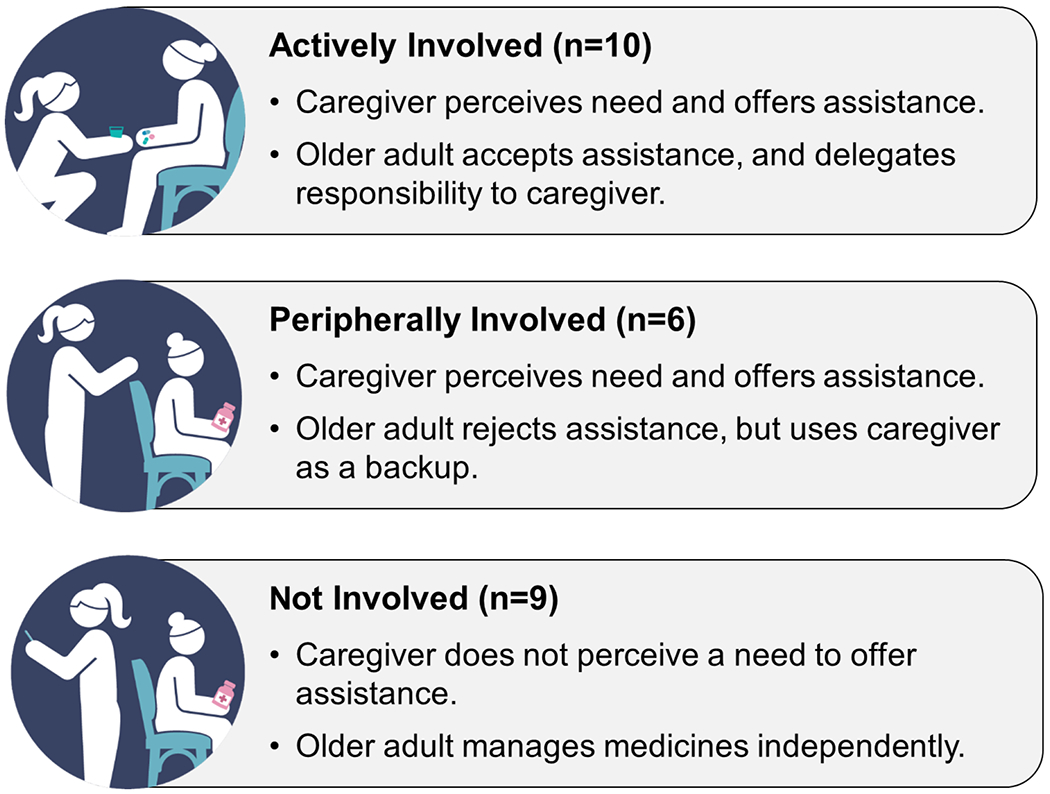

Three typologies of caregiver assistance with medications emerged: Actively Involved, Peripherally Involved, and Not Involved. A total of 10 caregivers were Actively Involved, which was defined as when the caregiver perceived a need for and offered assistance, and the patient accepted the assistance. Peripherally Involved (n=6) was defined as when the caregiver perceived a need and offered assistance; however the patient rejected this assistance, yet relied on the caregiver as a backup in managing his or her medications. To combat resistance from the patient, caregivers in this typology disguised assistance and deployed workaround strategies to monitor medication-taking behaviors to ensure safety. Lastly, 9 caregivers were classified as Not Involved, defined as when the caregiver did not perceive a need to offer assistance with medications, and the patient managed his or her medicines independently. A strong preference towards autonomy in medication management was shared across all three typologies.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest caregivers value independent medication management by their care recipient, up until safety is seriously questioned. Clinicians should not assume caregivers are actively and consistently involved in older adults’ medication management; instead, they should initiate conversations with patients and caregivers to better understand and facilitate co-management responsibilities, especially among those whose assistance is rejected by older adults.

Keywords: Caregiver, Older Adults, Medication, Qualitative Research

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 40% of adults 65 years and older take five or more prescription medications to manage multiple chronic conditions (MCC).1 Adherence to multi-drug regimens is challenging, as it requires individuals to engage in a series of complex tasks. For individuals to gain the benefits of drug therapy, they must: 1) fill prescriptions in a timely manner, 2) understand how to use their medication, 3) organize and consolidate multiple medications for an efficient daily schedule, 4) remember to take the correct dosage at the correct time, 5) monitor use and side effects, and 6) sustain the behavior over time.2 Previous research has consistently demonstrated that many older adults have difficulty performing these tasks,3–7 and as a result half of patients demonstrate suboptimal medication adherence,8 which is linked to greater morbidity and mortality.9–11

With increasing medication responsibilities, many older adults receive assistance from caregivers to manage their health. Roughly three quarters of caregivers broadly assist with medications,12,13 but no studies have investigated the degree to which caregivers support medication-related behaviors among older adults with MCC. Furthermore, few studies have enrolled racially and ethnically diverse caregivers in a variety of contexts that go beyond dementia-specific caregiving.14 This limitation is important, as societal values create differential access to resources and exposure to health-damaging conditions by race and ethnicity,15 and as a result Black and Latino individuals experience higher rates of comorbidity and subsequent medication burden;16–18 therefore understanding their experience is critical. The Health Literacy and Cognitive Function study (LitCog) offers the opportunity to explore this; LitCog is an ongoing cognitive aging study among a racially diverse sample of older adults and their caregivers. For this analysis, we conducted qualitative interviews among a subset of caregivers enrolled in the LitCog cohort to characterize caregiver medication assistance for diverse older adults with MCC.

METHODS

Parent Study

Beginning in 2008, 900 adults ages 55-74 were enrolled and continue to complete comprehensive cognitive, psychological, behavioral, and functional health assessments every 3 years as part of the LitCog study.19 The cohort began enrolling patients’ caregivers in 2019 to complete separate corresponding interviews. At that time, caregivers were eligible if they 1) were ≥18 years of age, 2) provided care for ≥6 months, and 3) assisted with at least one activity of daily living, instrumental activity of daily living or health management task.

Sub-study Sample and Procedure

For this sub-study, we deployed purposive sampling techniques to identify caregivers of patients managing ≥3 chronic conditions and prescribed ≥5 medications. Caregivers who met these criteria were invited by telephone on a rolling basis to participate in a qualitative interview held in a private room in a primary care clinic. A total of 31 caregivers were identified as eligible over the 5 month study period and invited to participate; 25 caregivers enrolled and provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

The research team developed a semi-structured qualitative interview guide (Supplementary Appendix S1). The interview guide was informed by the Medication Self-Management model; questions and probes sought to deconstruct caregiver experiences managing older adults’ medication-specific tasks.2 Caregivers were first asked to detail the general and health-related assistance they provided. Next, questions targeted the nature of any medication-specific assistance they provided, what kind of interactions, if any, caregivers had with healthcare providers, and any difficulties they faced when completing these activities. The lead author (RO) conducted all interviews. Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes, were audio recorded and transcribed by an independent transcription company.

Qualitative data from caregivers was supplemented with quantitative data (self-reported demographic and health information) collected from patients and caregivers during their ongoing participation in the LitCog study, which occurred an average of 7 weeks (Range: 1-23 weeks) prior to their qualitative interview.

Analysis

Analyses followed a quasi-inductive descriptive approach. A team of two coders (RO, ME) utilized an iterative, hybrid-coding process.20 Initial themes, used to structure the interview guide, were coded and then refined and supplemented with emergent codes that arose during review of the transcripts. Coders independently reviewed three transcripts, amended a list of preliminary codes, and then met to reconcile interpretive differences and update the coding scheme. They proceeded to review and write memos with the additional transcripts using the updated coding scheme. Regular meetings were held to review and refine the coding categorizations. During this process, coders identified three overarching medication management typologies within which participants fell based on the level of involvement caregivers reported at the time of the interview. Working definitions were developed for each typology, and the two coders independently assigned preliminary typologies to each caregiver. Coders then met to discuss, reconcile differences, amend definitions and apply final typologies to caregivers. Quantitative data was merged with the qualitative data, and crosstab queries were conducted on the demographic and health-related characteristics by medication management typology.21 All qualitative coding was conducted using NVivo Version 12 (QSR International), and descriptive statistics were calculated using STATA/SE software, version 15 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Caregivers had a mean age of 61 years (SD 12.5); 68% were female (68%), 52% identified as Black, 36% as White, and 12% as Latino. The majority were the patient’s spouse (40%) or adult child (44%) (Table 1). Patients had a mean age of 73 years (SD 6.4) and were managing an average of 5 chronic conditions and 7 daily medications.

Table 1.

Caregiver Demographic Characteristics

| Caregiver Characteristic, n(%) | Total N=25 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.4 (12.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 17 (68.0) |

| Male | 8 (32.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Latino | 3 (12.0) |

| White | 9 (36.0) |

| Black | 13 (52.0) |

| Income | |

| <$25,000 | 7 (28.0) |

| $25,000-49,999 | 9 (36.0) |

| $50,000-99,999 | 5 (20.0) |

| >$100,000 | 4 (16.0) |

| Education | |

| High School Degree or less | 7 (28.0) |

| Some college or technical school | 9 (36.0) |

| College graduate | 3 (12.0) |

| Graduate degree | 6 (24.0) |

| Relationship to LitCog Participant | |

| Spouse/Partner | 10 (40.0) |

| Child | 11 (44.0) |

| Other Family Member or Friend | 3 (12.0) |

| Unrelated Paid Caregiver | 1 (4.0) |

| Paid Caregiver* AND family member | 6 (24.0) |

| Live with Care Recipient | |

| Yes | 18 (72.0) |

| No | 7 (28.0) |

Employed by a caregiving agency to receive compensation for the care they provided

Upon review of the transcripts, three medication management typologies were observed (Figure 1). Caregivers were classified as Actively Involved (n=10), Peripherally Involved (n=6), and Not Involved (n=9). Caregiver and patient demographic characteristics by typology are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Three Classifications of the Need for and Acceptance of Caregiver Assistance in Managing Medications

Typology 1: Actively Involved

A total of 10 caregivers were classified as Actively Involved, which was defined as when the caregiver perceived a need and offered assistance, and the patient accepted the assistance and delegated responsibility to the caregiver. Actively Involved caregivers assumed primary responsibility for organizing, reminding, administering, and monitoring the patient’s medications (Table 2). This responsibility was often assumed after caregivers monitored patients’ medication taking behaviors, and noticed they were experiencing difficulties. Additionally, a critical component of this arrangement was that the patient accepted the assistance. One caregiver stated, “She used to get her medicines herself, but when I started learning them, the names and everything, she liked the assistance” (#11). This quote illustrates the caregiver perceived the arrangement was mutually agreed upon.

Table 2.

Medication Management Quotes by Medication Management Typology

| Actively Involved (n=10) |

Peripherally Involved (n=6) |

Not Involved (n=9) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Organize | “I suggested we line up the pill bottles front to back from morning, noon, midday-ish, and then dinner and evening. So we have these little rows of pill bottles, and I was putting them in a pill container.” (#23) | “She can’t remember if she took them. I’m like, ‘Well let’s start putting them in a daily thing so then you know if you took them or not.’ ‘No.’ She refuses and says ‘I know when I’m taking my pills. I know.’” (#14) | “I’m not involved. And she’s not involved in mine. We have one of those daily, you know, it’s seven days for the whole week. When mine are empty I get all my medicines, fill them all up and she does the same thing.” (#18) |

| Remind |

“I’ll remind her at night when I’m on my way to work I’ll say, ‘Did you take your medicine?’ I call her every night when I’m in the car on my way to work to make sure.” (#21) “I set alarms on my phone. When the alarms go off, I say, ‘Oh, okay. I guess it’s time for you to take a pill.’” (#12) |

“Sometimes he forgets and he’ll ask me, ‘Did I take such and such a thing?’ But I’ll be sitting right where I can see him. ‘No, you didn’t take that one.’ ‘Well, am I supposed to?’ ‘Yes, you do. You have to take that one too.’” (#24) “I reinforce [her taking her medicine], because she has the alarm set on her phone. But she doesn’t carry her phone on her person all the time. So I’ll go over there, shut it off and say, “Did you take your medicine?” (#15) |

“She sets up her daily medicine herself. She takes it. I give her no reminders. I don’t have to say, “Mom, did you take your medicine today?” She’s good about that.” (#17) “He remembers all the time. I don’t have to remind him. He does all that himself.” (#3) |

| Administer |

“I’II just give her the three different medicines and then a glass of water and then she take them.” (#8) “I can’t even trust him to keep [the pills] in his room and take them. They’re in with my pills. And so when I take my pills, I hand him his [pill box organizer] and I say “Give this back to me as soon as you take your pills,” and it goes back with me.” (#16) |

When she’s in the kitchen and she goes, ‘Daughter, go downstairs and bring me my medicine, my little box.’ So I’ll go down there and there’s three of them, so I just pick it up and take it to her. I’m not going to look at it.” (#25) “She has [her medicines] in a drawer organized in there. So I see it when she has the drawer out and taking them out and taking them.” (#14) |

“After her second surgery I had to hide [her pain medicines] in my room because whenever she hurt, she just wanted to pop them but she’s a recovering addict. And I had to actually issue it to her. I just did it with all the meds until she was better and then I gave them all back to her and she takes care of all that now.” (#1) |

| Monitor | “We’ll have breakfast together. I noticed that she was forgetting to take her thyroid medication. So it’s like, ‘Okay, here’s the thyroid pill, take it now with breakfast.’” (#12) | “He’s getting better, but I still have to make sure that you take your medication. Which pill are you supposed to take today? I keep up with it.” (#24) |

“I don’t help her. I take my pills, she takes her pills, we don’t have to help each other. We’re not at that point.” (#18) |

Typology 2: Peripherally Involved

A total of 6 caregivers were classified as Peripherally Involved. This typology was defined as when the caregiver perceived a need and offered assistance; however, the patient rejected this assistance, yet relied on the caregiver as a backup in managing his or her medications. Caregivers in this typology described making numerous attempts to problem solve with the patients’ medication-taking behaviors; however, these conversations were met with resistance when patients felt they had a sufficient system: ‘“No’ She refuses. ‘I know when I’m taking my pills. I know’” (#14). Caregivers were resigned to actively monitor from a distance, in order to provide backup assistance when requested. Caregivers reported experiencing difficult emotions when met with resistance from patients, “I get frustrated too because sometimes I’m trying to tell him things that would help him and he’ll shoot me off” (#24). Overall, these quotes illustrated how caregivers perceived discordance in the caregiving arrangement, and how concessions they made were emotionally challenging.

Typology 3: Not Involved

For the third typology, a total of 9 caregivers were classified as Not Involved. This was defined as when the caregiver did not perceive a need to offer assistance with medications, and the older adult managed his or her medicines independently. Caregivers commonly emphasized that they would help if the patient experienced a change in functioning or demonstrated a need for assistance, as described by one caregiver: “Well, if she needed my help with her medicine, I would help her. But so far, she has not” (#17).

Crosscutting Themes

Across all three typologies, caregivers expressed a strong preference for patients to maintain as much autonomy as possible. A caregiver who was classified as Not Involved stated “My mom is very headstrong so she likes to do stuff herself so I don’t wanna take that from her, and she’s not gonna let me do it so she takes care of all [of her medicines]” (#1). This sentiment of autonomy was echoed by a caregiver who was Peripherally Involved and stated: “I try to let her maintain her independence as much as possible, but all at the same time I’m observing as well” (#19). Even caregivers who were Actively Involved, credited the patient’s independence, as one caregiver stated: “Well, she can do it, but she’s slow doing it because of her arthritis. Of course I’ve always just made that one of my tasks” (#10). Overall, all caregivers valued promoting independence of medication management.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation identified three typologies in the manner which caregivers assisted older adults with managing their medications: active, peripherally, and uninvolved. Interestingly, caregivers did not become actively involved with medication management until they perceived the patient could benefit from assistance. Furthermore, patients’ acceptance of this assistance was a prerequisite for caregivers to become actively involved. When older adults rejected assistance, caregivers noted having to discretely monitor patients’ medication taking behaviors. Despite this, across the three typologies caregivers perceived a shared value with patients of promoting independence of medication management up until safety was questioned. Notably, we did not observe differences by race or ethnicity in typology membership, suggesting that these typologies may be ubiquitous across our study sample, and may be informed by overarching U.S. societal values of autonomy and personal responsibility.

Peripheral involvement in medication management appeared to be the most challenging for caregivers. While the caregiver perceived a need for assistance, the patient did not willingly accept this assistance; consequently, the caregiver continued to covertly monitor the patient and provide ongoing backup support. Clinicians may falsely assume that the presence of a caregiver indicates they are actively involved with their patient’s medications, yet our findings show there is a spectrum of assistance. It may be beneficial for clinicians to ask both the patient and caregiver how involved caregivers are with their patients’ medications. Clinicians could broadly ask the patient and caregiver to describe a typical day in how they take and manage their medicine, or ask whether different aspects of medication management occur mostly independently, together with caregivers, or by others.22 Engaging in this triadic dialogue may be challenging, yet this might more accurately reflect the manner which the patient and caregiver are managing their medications.

Our findings add to a large body of research on the role which caregivers support older adults in managing their health, as we further focus on the tasks, necessary skills, and capacity caregivers must possess to assist older adults manage their chronic conditions. Our findings are similar to Pohontsch and colleagues who found caregivers played a minimal role in medication management, but reported monitoring patients for assistance needs. Caregivers in their sample also reported a high degree of patient independence in managing their medications.23 Among patient-caregiver dyads managing MCC, Riffin et al. found two caregiving typologies: supportive and conflicted caregiving relationships. Supportive relationships were characterized by patient and caregiver agreement about the level of caregiver involvement, ability to perform health-related tasks, and collaborative decision-making and disease management, while conflicted relationships were characterized by disagreement in these aspects.24 Similar to our findings, this study also highlighted the complexity of health management between two individuals with distinct perceptions and preferences.

This research should be recognized in the context of several limitations. Our findings are limited to a small sample of English-speaking caregivers of older adults in one urban city who were contending with MCC and multidrug regimens. However, we purposefully included caregivers to older adults with high medication burden, as these caregivers are more likely to assist with complex medication regimens. Furthermore, we enrolled caregivers actively engaged in a caregiving role, which may have prevented the observation of other potential typologies. Additionally, we only interviewed caregivers and did not obtain the perspectives of the older adults. Lastly, the cross-sectional study design does not allow us to examine how caregivers assume new roles or how medication management responsibilities change over time.

Our findings suggest that caregivers value promoting independence of medication management by their care recipient, up until safety is questioned. Clinicians should not assume caregivers are actively involved in patients’ medication management and should initiate conversations with patients and caregivers to better understand and facilitate co-management responsibilities, especially among those who are peripherally involved.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Appendix S1: Interview Guide

Supplementary Table S1. Caregiver and Patient Demographic and Health Characteristics by Caregiver Medication Management Type

Key Points.

We identified three distinct typologies for the type of assistance older adults received from caregivers in managing their medications: Actively Involved, Peripherally Involved, and Not Involved.

Caregivers value independent medication management by their care recipient, up until safety is seriously questioned.

Why does this Paper Matter?

There is a range of assistance that older adults with multiple chronic conditions receive with their medication management, and clinicians should not assume caregivers are actively and consistently involved in older patients’ medication management.

Disclosure of Financial Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Wolf reports grants from Merck, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the NIH, and Eli Lilly outside the submitted work; and personal fees from Sanofi, Pfizer, and Luto outside the submitted work. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor played no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis and preparation of this manuscript.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institute on Aging, (R01AG030611), and by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001422). The funding agencies played no role in the study design, collection of data, analysis or interpretation of data. Dr. O’Conor is supported by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine (P30AG059988) and a training grant from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG070107).

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: These data were presented at the 2020 virtual Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting, November 5, 2020.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use Among Adults in the United States From 1999-2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1818–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey SC, Oramasionwu CU, Wolf MS. Rethinking adherence: a health literacy-informed model of medication self-management. J Health Commun. 2013;18 Suppl 1:20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gellad WF, Grenard JL, Marcum ZA. A Systematic Review of Barriers to Medication Adherence in the Elderly: Looking Beyond Cost and Regimen Complexity. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9:11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcum ZA, Gellad WF. Medication adherence to multidrug regimens. Clin Geriatr Med 2012;28: 287–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes CM. Medication Non-Adherence in the Elderly. Drugs & Aging. 2004;21:793–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey SC, Opsasnick LA, Curtis LM, et al. Longitudinal Investigation of Older Adults’ Ability to Self-Manage Complex Drug Regimens. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:569–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindquist LA, Lindquist LM, Zickuhr L, Friesema E, Wolf MS. Unnecessary complexity of home medication regimens among seniors. Patient Educ Couns 2014;96:93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho P, Rumsfeld JS, Masoudi FA, et al. Effect of medication nonadherence on hospitalization and mortality among patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1836–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho P, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, et al. Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1842–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care. 2005;43(6):521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:372–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhard SC, Young HM, Levine C, Kelly K, Choula R, Accius J. Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Care. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinbami OJ. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001-2010. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried V, Bernstein A, Bush M. Multiple chronic conditions among adults aged 45 and over: Trends over the past 10 years (NCHS Data Brief No. 100). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fryar C, Hirsch R, Eberhardt M, Yoon S, Wright J. Hypertension, high serum total cholesterol, and diabetes: racial and ethnic prevalence differences in US adults, 1999-2006. NCHS data brief. 2010(36):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Wilson EA, et al. Literacy, cognitive function, and health: results of the LitCog study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1300–1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson K, Bazeley P. Qualitative data analysis with NVivo. Third ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff JL, Boyd CM. A Look at Person-Centered and Family-Centered Care Among Older Adults: Results from a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohontsch NJ, Löffler A, Luck T, et al. Informal caregivers’ perspectives on health of and (potentially inappropriate) medication for (relatively) independent oldest-old people–a qualitative interview study. BMC Geriatr 2018;18: 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Iannone L, Fried T. Patient and Caregiver Perspectives on Managing Multiple Health Conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66: 1992–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Appendix S1: Interview Guide

Supplementary Table S1. Caregiver and Patient Demographic and Health Characteristics by Caregiver Medication Management Type