Abstract

The brain processes information by transmitting signals through highly connected and dynamic networks of neurons. Neurons use specific cellular structures, including axons, dendrites and synapses, and specific molecules, including cell adhesion molecules, ion channels and chemical receptors to form, maintain and communicate among cells in the networks. These cellular and molecular processes take place in environments rich of mechanical cues, thus offering ample opportunities for mechanical regulation of neural development and function. Recent studies have suggested the importance of mechanical cues and their potential regulatory roles in the development and maintenance of these neuronal structures. Also suggested are the importance of mechanical cues and their potential regulatory roles in the interaction and function of molecules mediating the interneuronal communications. In this review, we integrate the current understanding and suggest promising future directions of neuromechanobiology at the cellular and molecular levels. We examine several neuronal processes where mechanics likely plays a role and indicate how forces affect ligand binding, conformational change, and signal induction of molecules key to these neuronal processes, especially at the synapse. We also discuss the disease relevance of neuromechanobiology as well as therapies and engineering solutions to neurological disorders stemmed from this emergent field of study.

Keywords: neurons, synapse, protein–protein interaction, cell adhesion molecules, mechanics, force, stiffness

Introduction

Living systems are subjected to a variety of stimuli including not only chemical but also physical (e.g., visual, auditory, thermal, electrical, and mechanical) stimuli. Examples of mechanical stimuli include forces (e.g., pushing, pulling, shear stress, and pressure) and deformations (e.g., elongating, shortening, and twisting) that the environment exerts on the biological system, as well as reactions of the environment to the mechanical action of the biological system, such as the stiffness of the neighboring cell and/or the extracellular matrix (ECM). Mechanical stimuli can affect not only the whole organism and its parts such as various organs and tissues, but also individual cells and even a single molecule like a cell surface receptor. The study of the effects of mechanical stimulations has a long history, which is briefly summarized in Figure 1.

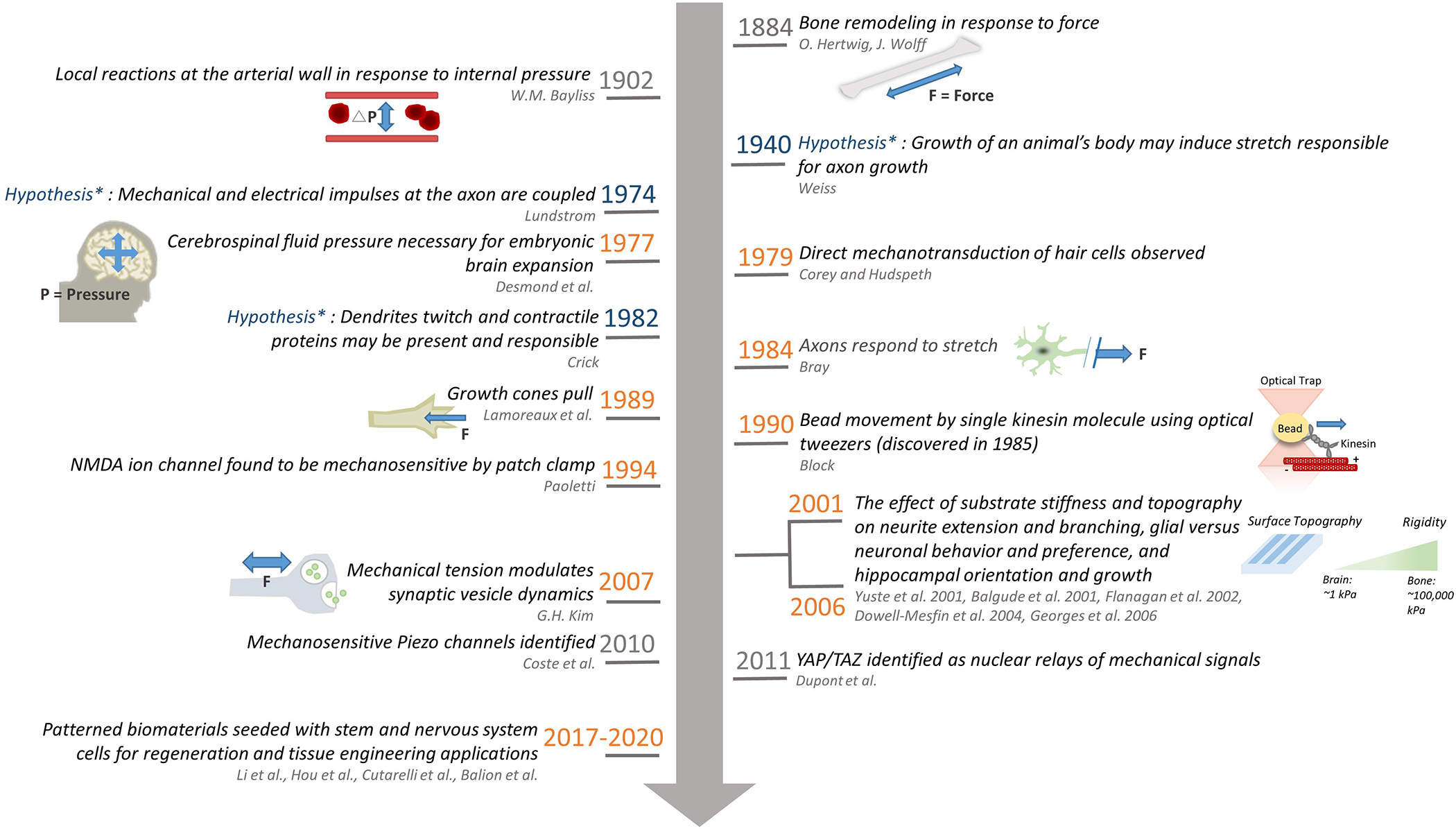

Figure 1.

Timeline of representative mechanobiology related hypotheses in the nervous system (blue), experimental findings in the nervous system (orange), and a few general pivotal works not specific to the nervous system (gray) where the lead author and the year on which the work was published is colored light and dark gray respectively, along with schematics depicting the work and the experimental techniques used in the study. The past few years have witnessed a rapid increase of studies on mechanobiology using biomaterials applied to the nervous system, and we only list a few representative papers here. Interested readers are referred to a recent review for more information[1].

Bone remodeling[2,3] and arterial wall response to pressure[4] where mechanical effects were noted were studied as early as the late 19th century, because the function of these systems involves generating or sustaining forces. However, there was little examination of the role of mechanical stimuli in the function of the nervous system until much later, perhaps because for a long time the brain had not intuitively been thought of as a mechanically rich environment (which it is as shown later). In 1941, Weiss hypothesized that the growth of an animal’s body places axons in a condition of stretching that could be responsible for axonal growth following synaptogenesis[5,6], yet this hypothesis was not directly tested until the 1970’s when mechanical aspects of the nervous system were considered and tested (Figure 1). CNS tissue is one of the softest tissues in the body, and in the absence of the arachnoid membranes, blood vessels, and skull, would collapse under its own weight. The softness and viscoelasticity results in part from the fact that the ECM of CNS tissue is rich in glycosaminoglycans but lacks the fibrous collagen-based ECM that contributes to the stiffness of other tissues.

Starting from the late 1970’s, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure was found necessary for embryonic brain development and loss of encasement in CSF pressure resulted in decreased brain volume[7]; axon growth was found to respond to applied mechanical tension[8]; the presence of mechanical detectors in vertebrate hair cells involved in hearing were noted[9], the molecules responsible for which were identified as the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels and Piezo channels (in addition to various other mechanosensitive channels at play) several decades later [10–12]. Since the 1990’s, the neural growth cone, an actin-rich structure at the distal end of sprouting axons, has been studied for the ability of its highly motile tip to integrate mechanical and chemical cues in the course of axon pathfinding[13]. Since the first observation[8], the research of tension-stimulated axon elongation has developed almost into a field entirely of its own [14–17], due in part to its potential as a regenerative strategy of nerves both in the central nervous system (CNS) and especially the peripheral nervous system (PNS)[18–20]. The molecular players underlying growth cone dynamics, including motors (myosin, kinesin and dynein) and filamentous tracks along which the motors move (actin, microtubule), have also been extensively studied[21–24] and even down to the level of single-molecule mechanical measurements using optical tweezers[25], one of the several ultrasensitive force tools extensively used for molecular mechanics experiments (Figure 1). Other key findings include dynamic regulation of synaptic vesicles by tension[26–28] and modulation of neurite extension, dendritic branching, and CNS cell type (i.e. neuron vs. glia) by mechanical cues such as surface stiffness and topography[29–32]. More recently, the level at which the mechanotransductive processes are probed has reached down to the nucleus of the cell through the discovery of mechanotransductive nuclear gene regulators such as the TAZ (transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif) and Yorkie-homologues YAP (Yes-associated protein)[33]. For example, it has been shown that a biosynthetic hydrogel functionalized with gelatin and sericin was unable to support 3D neural network formation, as the mesh size of the hydrogels partly limited cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation of YAP in astrocytes, leading to their inability to support the neurite outgrowth of co-cultured neurons. This study exemplifies the importance of understanding cell-material interactions at a molecular level. Ultimately, studying mechanics in the nervous system not only helps understand physiology and pathology, but it can also provide necessary information closer to the development of various therapeutic strategies[34–37].

Recent development witnesses the joining force of molecular biomechanics and molecular mechanobiology to identify, classify and characterize which molecules, parts of molecules, or assembly of molecules present, receive, transmit, transduce, and/or respond to mechanical stimuli and in what fashion and sequence[38]. Such combined work elucidates the working principles of the molecular players that present, receive, transmit, transduce, and respond to mechanical stimuli (mechanopresenters, mechanoreceptors, mechanotransmitters, mechanotransducers, and mechanoresponders, respectively). These molecular players are differentially expressed on various tissues and cells under the control of differentiation programs[38], which comprise parts of the pathways that connect the mechanical causes to biological effects.

Not only can the working principles of the molecular mechano-players bring insight into biochemical and biological studies, but they can also suggest novel drug strategies that target mechano-signaling pathways. Since mechano-signaling is often intertwined with biochemical signaling cascades, understanding how both biochemical and mechanical stimuli are processed by a system would aid in discovering and designing more comprehensive treatments. This could also bring insight into biomaterials work that may improve current therapeutic strategies or generate new ones that could work in a combinatorial way.

Neuromechanobiology at various levels

The CNS and PNS comprise complex and heterogeneous networks of cells and synaptic connections (Figure 2A), making it challenging to study the nervous system mechanobiologically and then translate the results into useful biomaterials and therapeutic approaches. This complexity is amplified by the variety of cell types present in addition to neurons. The largest class of non-neuronal cells, glial cells, within the CNS consist of oligodendrocytes, microglial cells, and astrocytes (Figure 2)

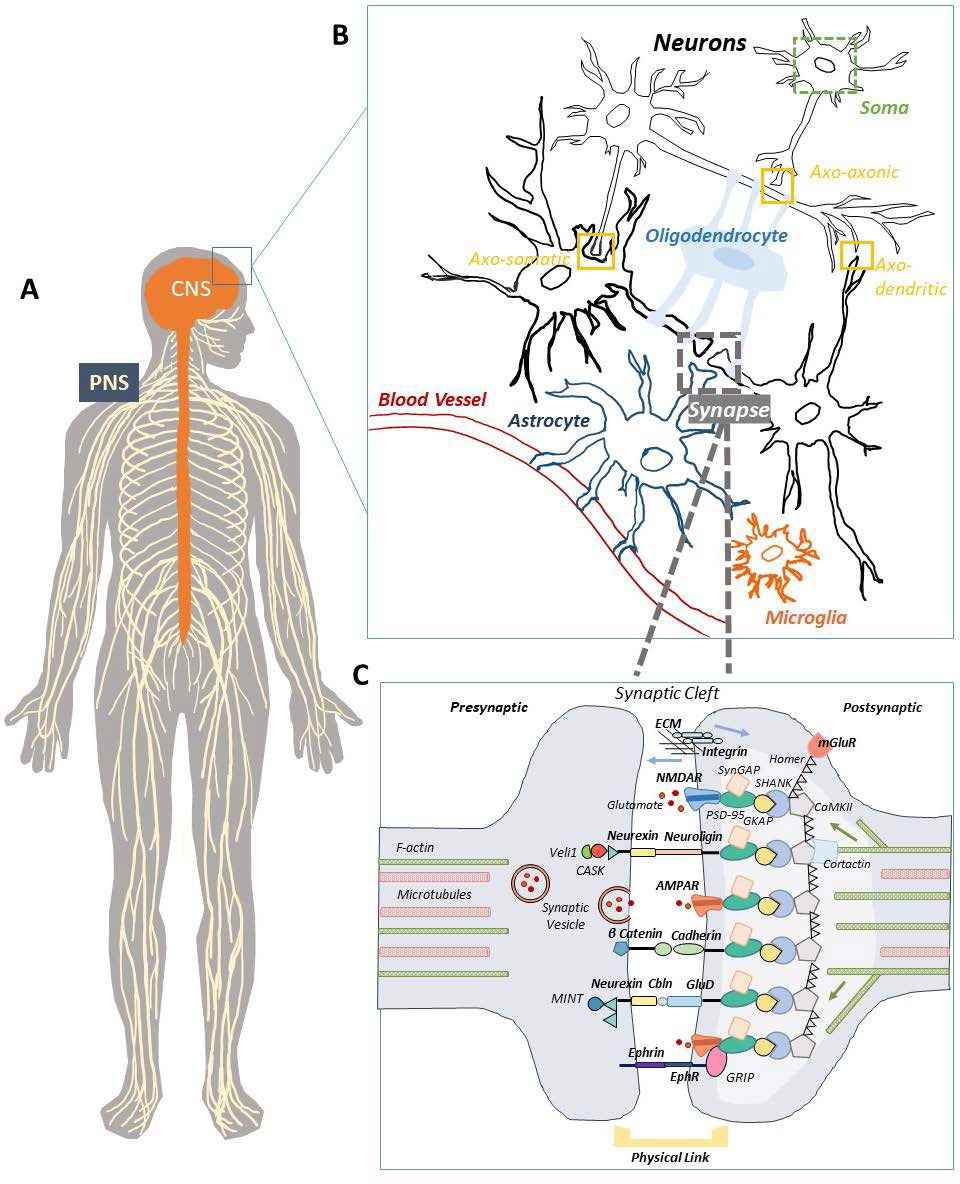

Figure 2.

A) The nervous system comprises of the brain and spinal cord, collectively referred to as the central nervous system (CNS), as well as nerves that innervate the surrounding body tissues and muscles, collectively referred to as the peripheral nervous system (PNS). B) Within the CNS, a mixed population of cells exist. The most common cells are excitable neurons (black), which consist of various parts including the cell body (soma), the unique space between the soma and axons (the axon initial segment), a long extension proceeding from the cell body (axon), branching segmentations of the axon (dendrites), and specialized communication points between neurons (synapse). Other cell types include oligodendrocytes (light blue) that serve several functions including ensheathing axons with myelin, astrocytes (dark blue) that serve many functions including supporting neuronal synapses with physical and chemical factors, and microglia (orange), the main resident immune cell of the CNS. C) Schematic of a synapse where synaptic vesicles, transsynaptic bonds, adaptor/scaffolding proteins, and cytoskeleton are shown – only a selection of proteins and molecules are depicted in this simplified diagram. Additional ligands and molecules may exist depending on the specific type of synapses or differentially expressed across different neuronal cell populations. The lighter colored gray at the post-synaptic terminal is depicting the post-synaptic density (PSD), for which the main scaffolding proteins have been shown.

Contacts are made between neurons themselves, with glial cells, and with the ECM, thus presenting an unique architecture and mechanical cues that the cells must sense and respond to accurately in order to establish and maintain appropriate connections. These inherently mechanical interactions are important not only for normal physiological function in the mature synapses, but they are also crucial mediators of other integral processes within the nervous system, including neuronal stem cell differentiation, migration, neurite extension, axon elongation, dendrite branching, etc. From a translational perspective, all these processes need to be studied first in vitro, e.g., using hydrogels as an optimal platform, to understand these processes with precise control, to develop therapeutic modalities for repairing the injured PNS and CNS. For example, injectable and resorbable hydrogels can be engineered to act as depots for the prolonged release of growth factors and chemoattracts for regrowing axons in spinal cord injury lesions. Similarly, hydrogels can be engineered to provide oriented scaffolds with linear guidance channels to facilitate the alignment of grafted cells and thereby direct axon regrowth. All these noted processes are important steps in terms of learning, memory, and regeneration following injury, but they are usually most broadly seen and characterized in the context of neural development.

Figure 3 depicts the schematic organization of this review. Because the recent increasing work in neuromechanobiology have more been at the whole-body, tissue, and cell scale, we will briefly touch on the mechanobiology at the tissue and cellular levels. But for progress in the organ and tissue levels, the readers are referred to excellent reviews and the references therein[39,40]. We will guide readers through work done at both various levels of scale as well as different developmental stages, ending at the synapse (Figure 3A). Our focus will be on the molecular level at which less work has been done, especially studies unique to the CNS. Our particular emphasis will be on receptor-mediated neural cell mechanoregulation, including cell surface receptors, intracellular adaptors, and cytoskeletal components whose current work and understanding are highly suggestive of their neuromechanobiological potential. We will also highlight some exciting areas of research on disease and therapy relevant to neuromechanobiology. In addition, we briefly summarize various newly developed treatments or tests based on such research and suggest areas where there are current gaps and disease types that could benefit from such work (Figure 3B).

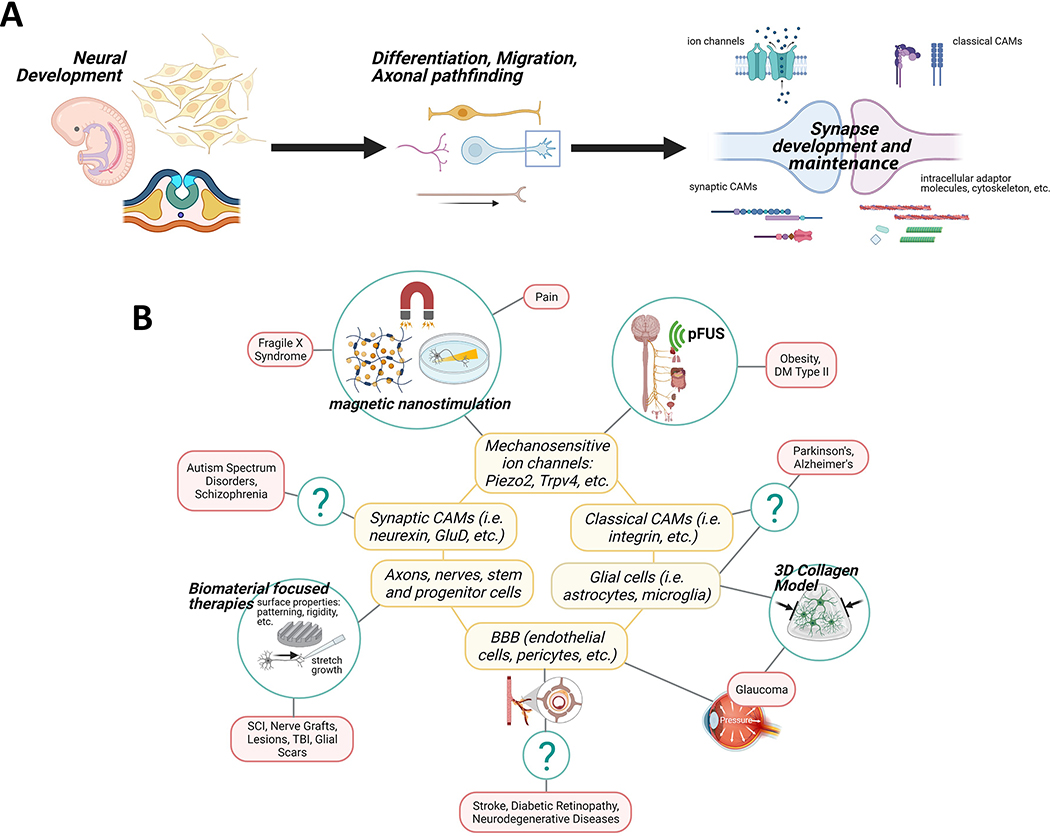

Figure 3.

A) Schematic organization of the paper showing the flow of topics according to descending anatomical levels and scales from organism, organ, tissue, cell, subcellular structure, to molecule. Also shown is the presentation flow from where mechanobiology has already been shown to play a role in Fthe nervous system to where future opportunities are suggested. B) A visual representation of various newly developed treatments or tests that have recently risen out of the neuromechanobiological work, broken down by area of the nervous system. Also presented are areas where there are current gaps and disease types that could benefit from such work. Figure was created with BioRender.com.

Mechanotransduction in neural development

As alluded to earlier, mechanical inputs play an important role in neuronal development. The recognition of the need of a proper CSF pressure in embryonic brain development dates back to 1977 [7]. Further work has identified and characterized more specific players involved in this process. Working models have also been developed to describe the role of stretch and pressure in brain volume development and cortex folding (gyrification), which are necessary for normal development and function of the adult brain. The main findings are briefly summarized below. The readers are referred to the recent review by Abuwarda et al.[41] for more details. Of note, neural tube closure varies with mechanical stiffness based on zippering points[42], but the stiffness sensors and effectors are largely unknown. The embryonic CSF is secreted into the lumen of the brain and ventricles, hollow cavities lined by neural stem and progenitor cells. Once the neural tube closes, the CSF induces a dramatic, pressure-driven expansion of the brain[7,43]. More recently, this CSF pressure-induced mechanical feedback during embryo development has been shown to also affect telencephalon growth and splitting into right and left hemispheres[44]. Such expansion may govern forebrain morphogenesis as suggested by a model that was based on a biphasic mechanism taking into account both differential contractility and stress-dependent growth[45]. Furthermore, only tangential growth but not radial growth was affected by CSF pressure differences[44] indicating a mechanoregulated portion of directionality in growth and development. This also suggests that there may be differentially expressed mechanosensors and transducers, as well as potentially different signaling mechanisms of various cell populations during embryogenesis and brain morphogenesis that would need to be better studied and characterized.

Another early feature of neurodevelopment is neural crest cell migration. In 2006, a seminal paper on lineage specification of stem cells put their differentiation into neural cells, muscle cells and bone cells under the same mechanical control of ECM stiffness independent of biochemical signals[46]. Similar to stem cells[47], tumor cells[48,49], epidermal cells[50], fibroblasts[51], smooth muscle cells[52], endothelial cells[53,54] and leukocytes[55], neural crest cells have been found to adhere, migrate, and differentiate into different CNS cell subtypes and exert traction force differentially on substrate of different stiffness and topography[56,57], characterized by reduced adhesion and increased traction forces at the leading edge during initial migration with increasing stiffness[58]. However, although actomyosin contraction has been shown to be involved in these processes, the specific molecules responsible for sensing these pressure changes and substrate stiffness are still poorly understood. So are the subsequent signaling pathways regulating neurodevelopment. For greater detail, the reader is referred to several recent reviews[41,59–61].

Even prior to the first demonstration of stem cell differentiation into neuron-like cells on soft substrates[46], ECM topography was suggested to modulate neurite outgrowth and differentiation in hippocampal neurons, with cells preferring pillared surfaces over smooth surfaces, and specifically the substrates with geometries of 2 μm inter-pillar spacing as the smallest gap size[31]. The hypothesis that neurons may be guided by external cues either from other cells (e.g., glia) or the ECM, a concept consistent with mechanosensing (despite not being classified as such), has actually been around since the 1980s and 1990s. Hynes and colleagues found that during prenatal development of the cerebellum in rats, the external granula (or germinal) layer migrated along the axon independent of the ECM molecule fibronectin[62]. This was also seen in movement of neural cells in the medulla oblongata of the fetal mouse. Here the tangential fibers potentially serve as a guidance with cues for relocation of immature neurons in the mouse subpial medullary region. The migration of neurons is associated with brain development[63] and mediated in part by neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM)[64]. The work on substrate architecture and stiffness was extended to examine how gold surfaces of different nano-scale roughness affects growth and physiology of a human neuroblastoma cell line[65]. The roughness could be sensed down to a differential scale of a few nanometers. Sensing of this fine level of difference is mainly mediated by focal adhesion complexes that exhibit a clear pattern of vinculin aggregates at the periphery of cells grown on “flat” surfaces relative to rough surfaces. This manifested in lost polarization and disorganized focal adhesions, resulting in necrosis on the rough surface, which was suggested to result from the lack of focal adhesions that deprives neurons of the integrin-mediated intracellular signals necessary for anchorage-dependent cell growth[65].

Forces at the axon, growth cone, and synapse

Axon extension and growth cone activities depend on cell motility and adhesion where cell adhesion molecules (CAMs)[66–68], molecular motors[69,70] and their filamentous tracks (actin and microtubules)[71–73] play key roles. In addition to endogenous forces, externally applied forces also have effects. As early as 1984, it was found that axons grow in response to stretch[8,74,75]. However, that perspective lost traction as the dominant view of biochemical guidance of axon growth took over. However, it has now been well established that neurite growth and expansion are driven by not only biochemical but also mechanical signals[15,72]. It is also well known that axonal transport is mechanically driven by motor proteins such as kinesin, myosin, dynesin [25]. Axonal stretch has also been shown to be a regulator for axonal transport[76]. The effect of different levels of stretch and tension on neuronal cell physiology has also been implicated in disease and trauma such as traumatic axonal injury[14]. Beyond the initial growth and expansion, contacts are also made along the axon either on ECM[30,77] or glial cells[78–80]. There is a large body of literature on these topics and the interested reader is referred to several recent reviews for more details[6,13,72,81].

Synapse neuromechanobiology and associated techniques

Since Joseph Altman’s 1962 discovery that, contrary to the previous prevailing thought, new neurons are generated in the adult brain[82,83], it has now been widely accepted that new neuronal connections, i.e., synapses, are made, maintained, and recycled throughout the lifespan. Based on the main method of studying synapses in the past, electron microscopy (EM), synapses also were for a long time thought to be static structures. It is now widely accepted that synapses are dynamically changing structures. The presynaptic active zone (PAZ) is maintained by a dense lattice of proteins consisting of the cytoskeleton and is also equipped with specialized membrane-bound proteins and machinery necessary for neurotransmission (i.e SNAP Soluble NSF Attachment Protein Receptor Complex aka SNARE). The post-synaptic neuron is also characterized by an electron-dense zone broadly referred to as the postsynaptic density (PSD) that physically anchors an assortment of membrane-bound proteins, including CAMs, ion channels, and metabotropic receptors. These post-synaptic terminals have been shown to be activated either biochemically (i.e. neurotransmitter binding) and/or electrically (i.e. voltage-gated Na+ channels), and we hypothesize and presume mechanically too (although supporting evidence remains to be shown). The dense opposing pre- and postsynaptic cores are maintained and aligned properly by the trans-synaptic CAMs. These structures are formed and dynamically regulated by intramolecular protein driven conformational changes[84] (Figure 2C).

Synapse formation, specification and plasticity involves multiple steps: neural growth cones recognize the target cell, specialized components are recruited for synapse specification, and synaptic junctions mature with circuit-specific properties or are removed by pruning or elimination[85]. This provides ample opportunities for neurons to experience mechanical forces some of which are likely supported by the molecular bonds and their associated adaptor proteins across and beneath the synaptic membrane. Synapses have different functions which are determined by their different structures. This structure-function relationship has been exemplified by the dendritic spine control of excitatory synapses and the presence of inhibitory synapses on the dendrite shaft. Additionally, the synaptic cleft between pre and post-synaptic neurons is known to be tightly regulated at a general distance of ~20 nm, for which the widths of the spine head vary greatly between excitatory versus inhibitory synapses (~20–24 nm vs ~12 nm)[86]. Furthermore, these post-synaptic receptors and synaptic cell adhesion molecules (sCAMs) are known to be bound to and modulated by intracellular adaptor/scaffolding proteins, kinases/phosphatases, and cytoskeletal elements, making them prime candidates for mechanotransduction. Whether they can sense and transduce mechanical information down to the nucleus through these connections remains to be investigated.

Some of the molecules involved in the regulation of synapse development, maintenance and function, their distributions in the nervous system and the roles of transsynaptic forces have recently been described in an excellent review[87]. Known regulatory mechanisms involve various binding proteins and CAMs in the synapse. To introduce the vast potential of synaptic CAMs and their associated intracellular and cytoskeletal connections for neuromechanobiological studies and translations, we will begin our discussion of synaptic molecules with the better characterized mechanosensitive ion channels.

Mechanosensitive channels

Mechanosensitive channels are ion channels on the cell membrane that open to allow ion influx upon change in membrane tension or curvature due to mechanical pushing, stretching or pulling. Two examples are Piezo1 and Piezo2[10]. Piezo1 is involved in cardiovascular mechanotransduction[88], red blood cell volume regulation[89], and epithelial homeostasis[90], but has also illustrated a role in sensing the local environment in neurons of the CNS[79]. Piezo2 is more associated with the nervous system due to their role in sensory neurons, including sensing touch and lung stretch[91]. Increasing work also suggests a role for both channels in the nervous system. For instance, Piezo1 regulates retinal ganglion cell axons’ differential growth patterns and expansions in response to substrate stiffness changes in the absence of chemical stimulants[16]. Piezo1 channel conductance was shown to respond to different micropillar properties, including greater stimulation with increased pillar spacing and reduced stiffness[92]. These changes were computationally modelled to be different from more commonly used techniques for probing mechanosensitive ion channels, including cellular indentation or high-speed pressure clamp assays. The techniques are important not only in defining function but also in translating basic science into clinical applications. Piezo channels have also been shown to mediate neuron-astrocyte connections and rigidity sensing of astrocytes by neurons. Substrates composed to mimic astrocyte stiffness allowed more functional development of neurons as measured by polarity and Ca2+ dynamics, despite the absence of live astrocytes co-cultured with neurons[79]. Furthermore, recently Piezo channels were shown to be recruited after axon injury to inhibit axon regeneration via the CamKIINos-PKG pathway[93]. A better understanding of their mechanosensitivity in homeostatic conditions as well as in injury as it relates to other biochemical mediators of this signaling pathway could be exploited for regenerative therapies. Some recent translational work in this area has already seen promise and will be covered later.

Additional mechanosensitive channels known to participate in the nervous system include a subset of the TRP family of proteins[94], N-type channels, and TRAAK channels, to name a few. Since their details have been thoroughly summarized in more specialized reviews (e.g., [95], [96]), this topic will not be covered here. However these mechanosensitive channels are important not only for allowing ion influxes and thus enabling cell-cell communication, but also in sensing their environment for further downstream signaling to help a cell make decisions in its life cycle[97].

Another well-known mechanosensitive ion channel specific to the nervous system is the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor. Since 1994, NMDA receptor has been known to be mechanosensitive[98]. However, there was not consistent follow-up research after that finding[99]. Like many other receptors, NMDA receptors have been identified to be bound to intracellular scaffolding proteins that comprise the PSD, which in turn are linked to the cytoskeleton and modulate morphology and number of spines at the postsynaptic terminal[100–102]. In addition, these proteins have been found to modulate receptor clustering into “supercomplexes” triggered by synapse maturation[103] and are physically linked to synaptic CAMs like neuroligin (NLGN)[104] (Figure 2c). How these synaptic scaffolding molecules mediate force transmission from the cell surface receptor that physically links the intracellular cytoskeletal components to the extracellular environment is currently not well understood. Yet knowledge of how the NMDA receptor is mechanosensitive suggests a very complex, intertwined dynamic system, which includes how the NMDA receptor is physically linked to NLGN and then recruited in supercomplexes through the help of sCAMs and intracellular scaffolding proteins that are connected to the cytoskeleton.

Cell adhesion molecules

Like anchorage-dependent cells of other systems, neurons physically interact with support cells such as glial cells (i.e. astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, etc.) and the ECM via specific CAMs. Three CAMs have already been mentioned in the preceding section: NCAM, integrins, and N-cadherin. Because ligand binding of CAMs connects cells to their physical surroundings, these molecular interactions must mediate the mechanical communications between them. Various bioactive hydrogels that in part or fully contain short peptide sequences of CAMs have been explored for neural tissue engineering. For example, various groups have tethered sequences such as IKVAV, or KHIFSDDSSE and many others to a host of substrate biomaterials (alginate, agarose, fibrin, PEG etc.) to study neuronal dynamics as well as develop implantable biomaterials[105,106]. For example, a IKVAV peptide-amphiphile (PA) material was synthesized that assembles into nanofibers at physiological pH[107]. The PA-IKVAV showed increased neural stem cell survival compared to 2D laminin controls in vitro. When used in a murine pre-clinical model of spinal cord injury, a reduction of glial scar formation, the regeneration of sensory fibers, and the significant improvement of behavior in mice were reported[108]. The leading CAM families involved are described below; for a complete list of CAMs in synapses, see recent reviews[109–111].

IgCAMs.

The immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily of CAMs[112] contain tandem repeats of Ig-like domains, hence the name IgCAMs. For example, NCAM is an IgCAM critical for neurodevelopment[113,114]. It uses the extracellular Ig-like domains to form variable trans and cis bonds, resulting in zipper-like structures. These zippers are hypothesized to be linked to neuronal avoidance mechanisms. The force-induced unfolding of Ig domains has been extensively researched by single-molecule experiments[115,116]. Since domain unfolding changes protein conformations, which can regulate intracellular signaling[117], IgCAMs have the potential to play a mechanobiology role. NCAM crosslinks calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and NMDA receptor through spectrin-based postsynaptic scaffolds that regulates synapses[118]. Additionally, dynein and NCAM reinforce synapse stability via tethering of microtubule plus-ends[119].

Integrins.

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors comprised of one each of 18 α and 8 β subunits[120,121]. The integrins expressed by neurons (e.g., α3, β1 and β3 integrins) on the nascent and mature synaptic membranes have defined functions[122–125] in the previously described processes where mechanics may have a role: neuronal migration[126], neurite growth[126] and path finding[67], dendritic spine plasticity[127], synaptic differentiation and maturation[128–130], synapse density[131], synaptic strength[132], and plasticity[133]. One of integrins’ key role is to regulate plasticity of dendritic spines: α3β1 integrin regulates long-term potentiation (LTP) through modulating NMDA receptor activity[123], whereas αVβ3 integrins modulates synaptic strength by stabilizing membrane-bound AMPA receptors[134]. Furthermore, integrins use actin regulated remodeling to adjust the spine’s structural plasticity: the integrin/focal adhesion pathway defines the following actin binding proteins (ABPs): Arp2/3 complex[135], cortactin[136], and cofilin[137]. Integrins’ role in mechanosignaling has been the focal point of mechanobiology across disciplines, including neuromechanobiology. Here, we use integrins to draw parallels to other more specialized synaptic CAMs and to exemplify how sCAMs could benefit from being evaluated in a similar fashion. Briefly, integrins physically link the ECM ligands to the actin cytoskeleton via adaptor proteins[138]. By doing so, integrins receive and transmit mechanical signals across the cell membrane, thus functioning as mechanoreceptor and transmitter[38,139]. One well-known feature of integrins is their existence of multiple conformations and their ability to undergo several types of conformational changes (Figure 4A).

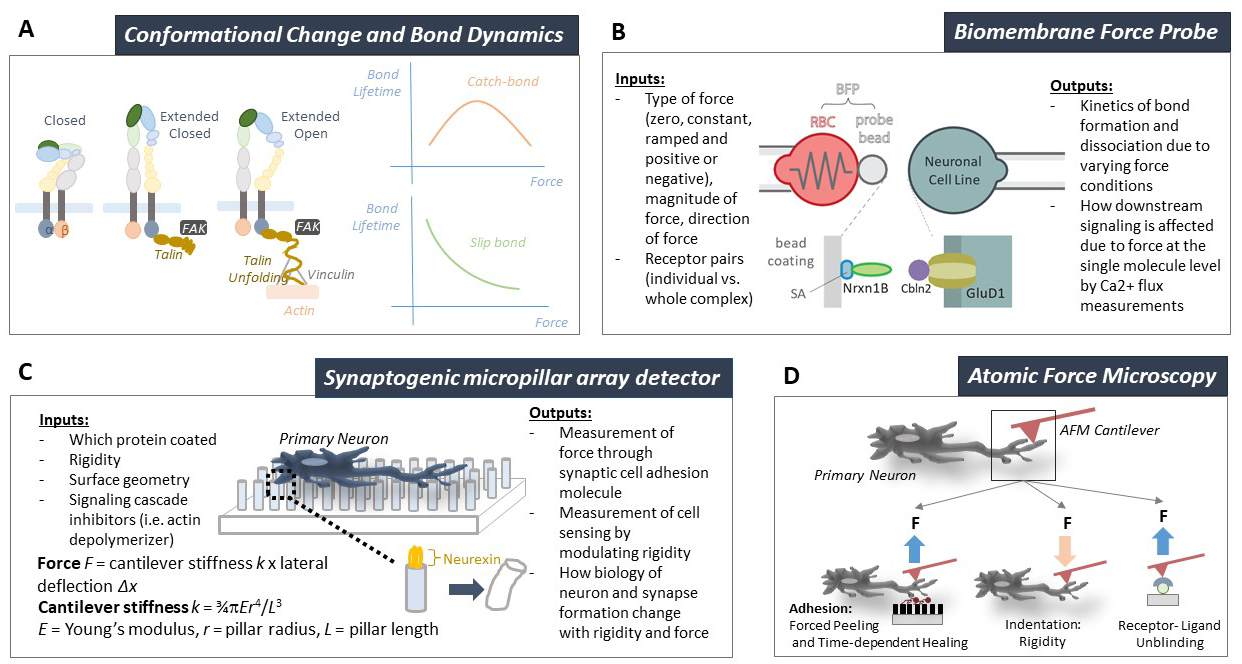

Figure 4.

A) Integrin molecule displaying its three conformational states, i.e. closed, extended closed, and extended open that are dependent upon force and signal through both outside-in and inside-out mechanisms via additional adaptor molecules and complexes such as talin, vinculin, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and actin cytoskeleton. Shown on the right are representative graphs of bond lifetime vs force plots showing catch-slip bond (top) where force first prolongs and later shortens bond lifetime and slip bond (bottom) where force monotonically shortens bond lifetime. B) Biomembrane force probe (BFP) for measuring receptor–ligand interaction under force (top). The lower cartoon depicts an experimental set up with a representative synapse specific cell adhesion molecules Neurexin 1β (NRXN1B) coated onto a bead attached to the red blood cell via biotin–streptavidin (SA) coupling, which acts as spring as a force transducer (left), and its corresponding binding partners, Cerebellin 2 (Cbln2) and Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor (GluD1) on the opposing side (right). C) Synapse differentiation and maintenance is mediated in part by specific cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs) which have been studied in individual cells on micropatterned assays. Here we depict a proposed cross-technique between micropatterned assays and micropillar array detectors (mPADs) that could concurrently measure synapse specification and endogenous force generation as part of mechanobiology study. D) Three applications of atomic force microscopy (AFM): 1) adhesion assay with peeling and healing timeframes to assess bond dissociation and association, 2) indentation assay for cell or ECM stiffness, and 3) kinetic assay for single receptor–ligand unbinding.

Distinct integrin conformations correspond to different ligand binding affinities and kinetics[140–143] and give rise to different molecular stiffness and bond durability under force[144–146]. Typically, the low affinity and fast-dissociating integrins have a bent ectodomain, closed legs, and closed headpiece (Figure 4A, left cartoon). The intermediate affinity and intermediate-dissociating integrins have an extended ectodomain, closed legs and closed headpiece (Figure 4A, middle cartoon). The high affinity and slow-dissociating integrins have an extended ectodomain, open legs and open headpiece (Figure 4A, right cartoon)[147–149]. Integrins’ conformations are dually regulated by both biochemical signaling and by force[150–152]. Molecular dynamics simulations[153–156] and single-molecule experiments[144,145] show that force applied to an integrin–ligand bond induces integrin conformational change to increase the binding affinity and prolong bond lifetime. This has been suggested to provide allosteric control of ligand binding properties from inside the cells by endogenous forces, as well as allosteric triggering of cell activation due to ligand binding and exogenous force exertion.

Single-bond force spectroscopy by AFM (Figure 4D)[157,158] and biomembrane force probe (BFP, Figure 4C)[159,160] have shown that force modulates ligand dissociation kinetics of integrins α5β1[161], α4β1[162], αLβ2[163], αMβ2[150], αVβ3[145,164], and αIIbβ3[146] by catch bond formation. Catch bonds are an unusual force dependency of the bond dissociation kinetics where mechanical force counterintuitively prolongs the bond lifetime by decelerating its dissociation[165] (Figure 4A, top curve). This is in contrast to the intuitive force dependency of slip bonds where force shortens the bond lifetime by accelerating its dissociation[166] (Figure 4A, bottom curve). Catch bonds usually occur at a low force or intermediate force regime because the bond would eventually be overpowered by force as it continues to increase, hence manifesting as catch-slip or slip-catch-slip bonds[157,161] (Figure 4A, top curve). Some integrin–ligand bonds have been observed to display other modes of force dependence of bond lifetime, including force-history dependence[167] where the bond lifetime depends on the previous force application, cyclic mechanical reinforcement[168] where the bond lifetime is substantially prolonged by cyclic forces, and dynamic catch[169] where trimolecular bond exhibits cooperative catch bond behavior despite that its two legs form slip bonds when interact separately. Such rich capacities for physical force to regulate their conformation, binding affinity and bond lifetime should provide integrins with the needed properties to play their putative mechanobiological roles. For example, integrin catch bond has been suggested to be a critical element in the molecular clutch for cell sensing of substrate rigidity[164], which will be discussed in detail shortly.

Understanding the mechanism of integrin mechano-signaling is important for designing patterned biomaterials that promote focal adhesions, enhance integrin clustering, and stimulate downstream signaling for the regeneration of neuron-like cells from human neural stem cells[170]. Furthermore, hydrogels formulated with the appropriate structure and viscoelasticity (relative to stiffer plastic or glass substrates) in tandem with presentation of the integrin-binding motif improves cerebellar cell self-assembly with increased neurites and greater synaptic efficiency as measured by Ca2+ signals[37].

Cadherins.

Cadherins consists of subfamilies of classical cadherins such as protocadherins, seven-pass transmembrane cadherins, fat cadherins, and cadherin-like neuronal receptors[171]. These Ca2+-dependent transmembrane proteins are found at intercellular junctions of many cell types, including neurons, to mediate stable cell–cell adhesion through the formation of homophilic bonds between their ectodomains[172], and may regulate neuronal recognition and connectivity[173,174] by inducing intracellular signaling[175]. For example, N-cadherin mediated neuron adhesion is required for the branching of growing dendrites[176] and stabilization of new synapses[177]. Overexpressing or knocking down N-cadherin could strengthen or diminish spine stability, respectively[178]. Signaling cascades induced by N-cadherin binding affect spine morphology, postsynaptic organization, presynaptic organization, and synapse functions[179]. This has been studied in vitro using a gelatin-based biomaterial platform. Gelatin methacrylate was functionalized with an N-cadherin extracellular peptide epitope to create a biomaterial that can form soft, patternable hydrogels[180]. It was shown that the N-cadherin functionality promoted survival and maturation of iPSC-derived glutamatergic neurons into synaptically connected networks.

Like integrins, cadherins are known to play important role in mechanotransduction[181,182]. For example, reducing the substrate stiffness results in less traction forces at cadherin-mediated cell–cell junctions. This suggests a mechanosenor and mechanomodulator role for the cadherin-mediated adhesion complex to adjust its strength in the context of environments of varying rigidity. During development, activity dependent dendrite arborization is fine-tuned by changing cadherin-dependent neuron-neuron interactions. N-cadherin and E-cadherin dimers show different disassembly kinetics, with N-cadherin depending strongly upon Ca2+ binding and being unable to form X-dimers[183]. These distinctions imply that N-cadherin and E-cadherin regulate unique mechanical effects. How force impacts cadherin bond dissociation has been examined using optical tweezers (Figure 1), AFM (Figure 4D) and BFP (Figure 4B)[184–189]. The rigid and stable ectodomain structure is believed to facilitate the transmission of mechanical force[190,191]. N-cadherin is necessary for long term potentiation (LTP) and spine enlargement, but not required for long term depression or spine density/morphology, suggesting that cadherins can selectively mediate synapse plasticity via N-cadherin presence in postnatal, excitatory synapses[192]. The N-cadherin/β-catenin complex has distinct mechanical behavior and supports synaptic spine formation through the regulation of plasticity in excitatory neurons[190]. Indeed, cadherin accumulates on synaptic membranes to stabilize postsynaptic receptors, e.g., kainate receptors[193] and AMPAR[194]. Furthermore, the surface-bound N-cadherin/β-catenin complex is a key player in active spine pruning, where β-catenin is rearranged to stabilize or remove individual spines[195].

Neurexins and neuroligins.

Synapse formation, function and specification are intricately linked to the interactions of sCAMs that are specific to neurons[196]. These include neurexins (NRXN) and neuroligins (NLGN), ephrin and ephrin receptor, and glutamate delta receptors whose trans interactions forms bridges spanning across the synaptic cleft[110].

Vertebrate NRXNs and NLGNs are the most well-known sCAMs with a more well-established role in synaptic function[197,198]. Inhibitory or excitatory synapse formation is mediated in part by alternative splicing of postsynaptic NLGNs[199,200]. NRXN–NLGN bonds are presented as heparan sulfate chains on NRXNs to monitor synapse specificity in isoforms[201,202], perform synapse development[203], and stabilize dendritic filopodia during synaptogenesis[204].

This is important because the strength of mature synapses can be decreased by proteolytic cleavages of juxtamembrane NLGN, which triggers presynaptic release[205,206]. NRXNs and NLGNs activate their respective mechanisms by binding to each other and interacting with intercellular proteins, such as PDZ-domain proteins, and their role is evidenced from the observations that mice lacking NRXNs or NLGNs lose significant numbers of synaptic transmissions. However, the exact mechanism underlying their function for synaptic transmissions remain unclear. One hypothesis is that NRXNs and NLGNs not only mediate trans-synaptic cell adhesion but also activate pre-and-post-synaptic signals that allow for proper operation of synapses[207]. Activation of synapses via NRXNs and/or NLGNs specifically shapes synaptic efficacy and plasticity. In addition to NLGNs[208], neurexophilins (neuropeptide-like proteins) and dystroglycan (a cell-adhesion molecule involved in many types of cell junction) are also NRXN ligands[209,210]. The functional change in synapses triggered by the binding of neurexophilin or dystroglycan to NRXNs is less clear than that of binding to NLGNs, despite more recent work elucidating binding affinity as it relates to alternative splicing of NRXN[211].

Eph receptors and ephrin.

Most receptor tyrosine kinases are Eph receptors, and these are comprised of A- and B-subclass Eph receptors. Their ligands, ephrins, also consist of A- and B-subclass ephrins based on their affinities and preservation of sequences[212]. Similar to integrins, signaling induced by Eph–ephrin interactions can be bidirectionally transmitted across cell membrane[213]. Similar to cadherins, Ephs and ephrins bind with each other in trans or cis: trans-interactions propagate Eph–ephrin signaling, but cis-interactions inhibit signaling from occurring[214]. On cell surface, activated Ephs form clusters of different Eph ligands[215,216], which are able to activate each other’s counterparts by transphosphorylating kinase domains of inactivated Ephs, which initiates the downstream signaling cascades[217].

Different types of Ephs and ephrins are expressed at different cells of the nervous system during different developmental stages. For example, EphB2s are expressed in dendrites and dendritic spines[218], EphA4 on the PSD[219], and Ephrin-A3 and EphA on dendritic spines[220]. Eph and ephrin have been reported to mediate neural development[221,222], dendritic spine formation[223], morphology[224], maturation[225,226], axon guidance[227], synapse formation[228], synaptic specializations[229], synaptic plasticity[230,231], and synaptogenesis[232,233]. Eph–Ephrin interactions can regulate actin cytoskeleton reorganization[226,234] and NMDA receptor trafficking[235,236].

Eph–Ephrin interactions also mediate cell signaling in response to mechanical cues. For example, tensile strain and compressive force have been shown to alter the expression of EphrinA2 and EphrinB2[237]. It has been proposed that the Eph–Ephrin binding can mediate force-induced modification of cellular activities, suggesting a mechanotransducer role of the Eph receptors[238]. Further, Eph’s downstream signals can induce actin cytoskeleton remodeling and actomyosin contraction[239].

Glutamate Delta receptors.

The delta receptors, Glutamate Delta 1 and 2 (GluD1 and GluD2), form a trimolecular complex with NRXN1 expressed on pre-synaptic membrane through the mediation of soluble protein cerebellins, Cbln2 and Cbln1, respectively[240,241]. These cross-synaptic cleft interactions play important roles in both cerebellar function and hearing at high frequency sounds. GluD1 is expressed highly in several regions including the hippocampus[242,243] and cerebellar interneurons[244] where it has been found to aid in ensuring proper excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation[245] as well as correct alignment of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell interneuron synapses in the cerebellum[244]. It is also highly expressed in inner ear hair cells and lack of its presence leads to the incapacity for mice to hear high frequency sounds[246]. Genetic association studies have pointed to a role of GluD1 in several neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depressive disorders[247,248]. GluD1 knockout in mice results in social deficits[249], abnormal cognitive function[249,250], and increased dendritic spine counts similar to what is seen in disorders like autism[251]. To maintain a stable junctional structure important to the communication between the pre- and post-synaptic cell membranes, the transynaptic bonds of the sCAMs likely experience mechanical forces during long-term growth or short-term body movement that stretch the neurons. It is therefore possible that these bonds may receive and respond to such mechanical cues. Much of the knowledge and work on GluD1 has stemmed from the more extensive knowledge found in GluD2 receptors. For instance, work on GluD2 receptors has already shown that the adhesion to its counterpart sCAMs (NRXN1β via Cbln1) is essential for consequential D-serine (one of the known agonists for the other iGluRs) signaling[252]. Furthermore, this low-affinity D-serine binding is modulated by the hinge region of the ligand binding domain in the GluD2 receptor. This hinge region varies greatly between different iGluRs, but is known to alter gating ability[253]. Integrins also have a hinge structure, different conformational states, and force-regulated outside-in and inside-out signaling activities as discussed earlier. These comparisons further support the hypothesis that GluD receptors may be mechanically regulated. In conjunction with this hinge structure, synaptic terminal differentiation by GluD2 is mediated by its extracellular leucine/isoleucine/valine binding protein domain[254] of the amino terminal domain (the portion of the receptor that binds Cbln1 and thus NRXN). This extracellular binding domain is well known to exhibit conformational changes that opens or closes the clamshell-like structure related to ligand binding in the ligand binding domain[255,256], displaying yet another similar feature with integrins.

Overall, there has not been much direct evidence of mechanoregulation of synapses. However, during long-term growth or short-term synapse dynamics that creates tensile forces at the synaptic terminal, the transynaptic bonds of the sCAMs likely experience mechanical forces in order to maintain a stable junctional structure important to the communication between the pre- and post-synaptic cell membranes. It is therefore possible that these bonds may receive mechanical cues. However, to transmit such mechanical cues into the cell and transduce them into biological signals, it requires intracellular interactions of the sCAMs cytoplasmic domains with adaptor/scaffolding proteins, which is the topic of the next subsection.

Mechanical techniques applicable to studying sCAMs

Recently, a variety of techniques have been developed to study synaptogenesis and the role of various molecules in synaptic terminal differentiation and maturation, including biomimetic models, co-culture assays with non-neuronal cells, microspheres, and micropatterning assays[257]. An example is plating neuroligin expressing neurons on micropatterned assays coated with the corresponding neurexin -for studying the role of these molecular interactions in synaptogenesis[258]. Although the micropatterning assay substrates used in this study do not fully resemble the natural in vivo environment of the brain, they nevertheless enable high-throughput and high-content analysis of synapse mimics. In parallel, various techniques have been developed from other fields of mechanobiology and bioengineering to study the role of forces on molecular interactions[185]. An example is microfabrication technology used to pattern CAMs on the micropillar array detectors (mPADs)[259] (Figure 4C). Each elastomeric pillar in the array behaves mechanically as a cantilever the deflection of which is directly proportional to the lateral force acting on its tip. mPADs have been widely used to measure cell-generated traction forces mediated by various CAMs, including N-cadherin[260] and integrins[261], and even in neural stem cells[262]. An additional novel technique has also been used that combined the use of a microarray based synaptogenic assay with AFM to study strength of synaptogenic CAMs as well as re-association and healing rates[263] (Figure 4D). Future studies will benefit from the fusion of synaptogenesis and force measurement techniques to further define the role of forces in synaptogenesis and synaptic maturation, bridging the gap of knowledge between the initial forces at the growth cone and dendrite arborization that eventually leads to synapse formation. A more comprehensive understanding of mechanomodulation of synaptogenesis is key for developing biomaterials that would not only match with the natural environment, but also function to enhance survivability of implanted cells and promote their integration with existing cells. Without appropriate mechanical cues, the biomaterials solution to neural tissues may not be successful, as demonstrated in a recent study of 3D neural tissue analogs where insufficient cues for astrocytic mechanosignaling through YAP/actin polymerization resulted in the inability to form appropriate neuron-astrocyte networks and growth[264].

Intracellular signaling proteins and cytoskeleton

The mechanically encoded signals that are first received through the CAM’s ectodomain are transmitted through interactions between their cytoplasmic domains and intracellular adaptor proteins. These in turn may be biochemically regulated by kinases and phosphatases. For integrins, the adaptors include talin[265,266], kindlin[267], filamin[268] and α -actinin[269]. Talin serves as a mechanosensitive signaling hub[151] and transmits force by interacting directly as well as indirectly via vinculin with the actin cytoskeleton[152,270]. Both talin[271,272] and vinculin[273] have been shown to bear endogenous force with Förster resonance energy transfer-based (FRET)-tension sensors[274,275]. Their activities can be regulated dually by force-induced conformational changes[164,272,273] and by binding of signaling molecules that relieves their autoinhibition[151]. In addition, integrins and their adaptor proteins are capable of direct binding to kinases (e.g., Arg kinase and focal adhesion protein-tyrosine kinase or FAK), in turn initiating signaling for gene transcription and dynamic cytoskeleton organization, as well as inducing neuronal firing activities and modulating trafficking of NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors[127].

Cadherins’ cytoplasmic domain also binds vinculin, but their main associated adaptors are the catenin family (e.g., α, β, γ, or p120 catenin)[181]. Cadherin/catenin complexes are mechanically linked via force and their ability to expose vinculin binding sites on α-catenins[276]. Force is able to conformationally change α-catenin and allow vinculin to bind and trigger actomyosin cascades. Activated vinculin not only directly binds to F-actin, but also recruits Ena/VASP family proteins to promote actin assembly, further reinforcing the cadherin–cytoskeleton coupling[276]. Existing evidence has already shown that a mechanical coupling between the cadherin/β-catenin complex along with actin in primary neurons plays a major role in growth cone advancement and neurite extension via neuron/N-Cadherin coated substrate adhesions[68].

NRXNs and NLGNs also interact with the actin cytoskeleton via adaptor/scaffolding proteins. These include the trimolecular complex among CASK, VEILs and MINTs on the presynaptic side[277]. On the post-synaptic side, these include PSD protein 95 (PSD-95), which binds to AMPA-type glutamate receptors through its first PDZ domain, and to NLGNs through its third PDZ domain[278], synaptic scaffolding molecule, GKAP and SHANKs (Figure 2C). As a result of their binding to PDZ-domain proteins, NRXNs and NLGNs form a tight, asymmetric junction[85].

An important concept of cell motility and rigidity sensing is that of mechanical clutch, which plays a central role of transmitting the intracellular forces generated by motors exerting on the cytoskeleton to the CAMs. In so doing, cellular traction is applied via interactions with the ECM ligands to the substrate to propel cell motion or gauge substrate rigidity[279,280]. The molecular mechanism underlying the mechanical clutch is thought to involve the dynamic balance of the force-modulated lifetimes of various bonds in the force transmission pathways[281]. The integrin αVβ3-mediated rigidity sensing involves talin and vinculin[145,164]. In the ‘actin–talin–integrin–ligand clutch’ model, the mechanism involves the interplay of two force-dependent events, the unfolding of talin and the unbinding of integrin–ligand bond, because large forces in response to a stiff substrate (but not small forces in response to a soft substrate) unfold talin to expose its cryptic binding sites for the recruitment of vinculin[164].

Although studies of the above level of details have yet to be done using cells of the nervous system, a plausible mechanical clutch molecule in hippocampal neurons has been suggested, which is Shootin1, a key molecule that participates in neuronal polarization and axon outgrowth[282–284]. Shootin1 has two isoforms, Shootin1a and Shootin1b. Shootin1b accumulates at the leading process of growth cones and couples F-actin retrograde flow through the F-actin-binding protein cortactin to L1-CAM[285], a cell adhesion molecule on the opposing cell surface. The axonal chemoattractant netrin-1 activates Pak1, a downstream kinase of Cdc42 and Rac1, which phosphorylates Shootin1 to enhance its interaction with cortactin, thereby potentially tuning the coupling between F-actin and adhesion to upregulate traction forces for axon outgrowth[286]. Importantly, the proposed role of Shootin1b as a mechanical clutch[287] for olfactory neurons is necessary for force generation and neuronal migration, since knocking out Shootin1b disturbed the leading process extension and ultimately movement to the olfactory bulb[66]. A recent work employed ECM mimicking hydrogels composed of collagen and hyaluronic acid to understand the role of matrix viscoelasticity on neurite sprouting, axon elongation, and expression of neurogenic proteins[288]. Utilizing a modified Chan’s motor-clutch model[289] with a dissipation component to mechanistically understand the impact, the authors observed that downregulation of Piezo1 and cytoplasm localization of YAP played a role in viscoelasticity-induced neurogenesis, in vitro and in vivo. Similarly, Fmn2, a member of the formin family that had previously been classified as a growth cone motility regulator, has recently been found to function as a molecular clutch using traction force microscopy[290].

These intracellular adaptor molecules have both direct and indirect interactions with the cytoskeleton, an interconnected network that consists of tightly coupled actin filaments, microtubules and neurofilaments plus a variety of regulatory proteins. The cytoskeleton mediates not only mechanics such as shape change and cell motility, but also structural integrity and organization inside the cell[291]. There are many mechanisms that make the cytoskeleton a key player in the mechanobiology, which have also been extensively characterized in the neuronal growth cone. For example, dendritic spine shape is a structural element maintained in part by the actin cytoskeleton. F-actin is spatiotemporally organized in different dendritic spines via actin binding proteins.

Additionally, microtubule dynamics are altered by specific factors like dendritic kinesin-4 [292] and microtubule plus end-binding protein EB3’s interactions with postsynaptic scaffold protein PSD-95. Dendritic kinesin-4 is involved in retaining memory and knowledge[293]; whereas EB3 and PSD-95’s pairing decreases microtubule interaction as a whole[294]. Understanding how the dendritic spine size and shape are modulated and maintained through these factors is important since these factors are related to electrical activity as well as changes in synaptic activity and efficiency[295–297].

Dysfunctional neuromechanotransduction and diseases

The importance of neuromechanobiology lies not only in the mechanical effects on normal neurophysiology but also in its relevance to neurological disorders, as summarized in Figure 3B. Indeed, a broad spectrum of neurological diseases may result from problems connected to neuromechanobiological aspects, ranging from changes in mechanical properties to the dysfunction of the cellular and molecular players in the nervous system discussed earlier. At the tissue mechanics level, for example, altered mechanical properties of the brain and neurons have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Using magnetic resonance elastography, the viscoelastic properties of brains were found to be changed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease[298]. Although such changes were found in both areas that demonstrated volume loss as well as those that did not, and how such changes relate to diseased vs. healthy tissue has not been elucidated, different tissue mechanics may affect signaling via rigidity sensing.

At the level of molecular mechanics, examining actin cytoskeletal dynamics has been instrumental in understanding maladaptive neuronal plasticity and memory formation as a contributing factor to vulnerability to substance abuse disorder relapse. For instance, it was shown that memory storage involving methamphetamine (METH), but not those for fear or food, results in an increased spine density of dendrites of the amygdala that can be reversed by specific depolymerization of actin[299]. Actin polymerization is a necessary process for many homeostatic events including learning and memory and long-term potentiation, thus a therapy aimed at inhibiting actin polymerization is too broad and also does not address specific mechanisms of METH-associated learning memory[300]. As such, authors also evaluated nonmuscle myosin II, which triggers actin polymerization induced by mechanical forces in part with synaptic stimulation[301]. With a single systemic injection of blebbistatin (a small molecule inhibitor of class II myosin isoforms) context-induced drug seeking is disrupted long-term (≥30 days)[302]. This METH-associated learning is driven by NMII-dependent increases in spine motility of the basolateral amygdala but not the hippocampus[303], which presents with findings important in understanding the molecular mechanism of addiction as well as novel potential therapeutic avenues.

Actin dynamics is also regulated by F-actin-binding protein drebrin, which bundles actin filaments necessary in maintaining synaptic integrity[304]. Drebrin is downregulated in the nucleus accumbens following heroin delivery in mice accompanied with disruption in dendritic spine structure and function[305] that is similar to what is seen persisting even in prolonged abstinence[306]. These changes are further validated by findings that knockdown of drebrin exacerbated these alterations but were normalized by its overexpression, which mediates actin cycling and relapse-like behavior[305]. Further studies of these molecules from neuromechanobiology perspectives could add additional insight into therapies aimed at one of the greatest challenges of opiate addiction: the life-long potential for relapse[307], which is in large part mediated by maladaptive synaptic plasticity[308,309].

At the level of molecular neuromechanobiology, the NMDA receptor has long been known to be mechanically activatable[98,99] where the C terminus of the NR2B subunit regulates its mechanosensitivity[310]. Increasing evidence has shown the NMDA receptor (especially the NR2B portion) is associated with the chronic pain as a result of rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[311]. A better understanding of this mechanosensitivity as it relates to normal physiological and disturbed states such as in RA would allow for the development of better therapeutic strategies aimed at dysfunctions within the receptor. Another family of molecules that play a role in the etiology of RA are integrins[150,312,313], whose role in the mechanosensing has been documented by a vast array of literature[38,146,314,315] and discussed earlier. The mechanoregulation, or the dysregulation thereof, of integrins may play a role in other neurological diseases. For example, integrin αMβ2 has been implicated in accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ)[316], blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability in a mouse stroke model[317], and Aβ-induced triggering of microglia, the primary immunity brain cells[318]. In addition, integrin αMβ2 has been shown to be an important regulator of microglial activation[319]. The αMβ2 inflammasome activation was found to be directly linked to loss of coeruleus noradrenergic neurons by inducing microglial proinflammatory activation that contributed to oxidative stress and ultimately neuron loss[320]. β1 and β2 integrins have also been shown to interact with scaffolding protein Ran-binding protein 9 (RanBP9)[321]. RanBP9 is upregulated in brains affected with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and promotes accumulation of Aβ peptides by scaffolding amyloid precursor protein (APP), lipoprotein receptor-related protein, and β-site APP-cleaving enzyme complexes that accelerate APP endocytosis[322]. Overexpression of RanBP9 interrupts integrin-mediated focal adhesion signaling and cell attachment and spreading by increasing β1 integrin endocytosis and by inhibiting talin and vinculin localization at focal adhesion sites[323]. Also, the ABP cofilin has been shown to form cofilin-rod aggregates, which act as a marker for Alzheimer’s pathophysiology in addition to Aβ and tau aggregates, the hallmark markers for Alzheimer’s disease progression[324–326].

Yet another integrin-related neurological disorder is Parkinson’s disease (PD). PD is clinically known for a loss of dopamine, especially of dopaminergic neuron projections from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the dorsolateral striatum. Yet, how dopaminergic neuron projections are initially made and then lost in PD remains elusive. However, integrin α5β1 has been shown to be involved in the outgrowth of dopaminergic neurites onto striatal neurons, as inhibition of α5β1 expression resulted in suppressed dopaminergic neurite outgrowth[327]. This suggests a potential mechanism underlying some of the cellular changes associated with PD. In addition, there has recently been a lot of interest in microglia for mechanotransductive processes as potential regulatory mechanisms underlying their roles in disease[328–330], including PD. For instance, microglia have been shown to exhibit durotaxis towards stiffer tissues[329,330]. PD is also associated with abnormal formation of protein known as Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, composed of various proteins, of which α-synuclein is the most prominent[331–333]. Although α-synuclein in normal quantities serves physiological roles, its accumulation results in cell death in neurons[334] and inflammatory responses in astrocytes[335]. Specifically, β1-integrin-mediated migration of microglia in a PD model changes in response to neuron-released α-synuclein in a dose-dependent manner[336]. Another hallmark of neurodegenerative disorders, including PD, is loss of coeruleus noradrenergic neurons in the brainstem, which is thought to be in part regulated by microglia-mediated neuroinflammation through β2-integrins[319,320].

Almost all brain function abnormalities are directly or indirectly connected with synaptic function[85], providing a potential link to synapse neuromechanobiology. For example, mutations in NRXN and NLGN associated genes have correlated with autism spectrum disorders, Tourette’s syndrome, learning disability and/or schizophrenia; sometimes members of the same family have also presented with different cognitive disorders despite the same genetic mutation[337–349], suggesting additional mechanisms beyond genetic encoding. In addition to the sCAMs, the intracellular scaffolding proteins to which these sCAMs are bound have been implicated in the same or similar neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders (such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder) on several accounts[279,280]. These include but are not limited to SHANK proteins[101], PSD-95[350], and Ankyrins[351,352]. The continuance in presentation of independent clinical phenotypes across the various levels of both sCAMs and their intracellular binding partners suggests a common signaling pathway. For example, at the cytoskeletal level, the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain has also been associated with synaptic plasticity through the remodeling of dendritic spines. Synaptic plasticity in the CNS is dynamically altered via the pharmacological targeting of specific proteins, such as actin cytoskeleton regulatory proteins srGAP3 and Rac1, in varying neuropathic pain development phases[353]. Although the direct role of force in neuropathic pain has not been evaluated, one cannot help to speculate a potential role based on the involvement of mechanical players (such as actin, microtubules, etc.) in dendrite initiation, stabilization, remodeling and turnover. Thus, in addition to identifying common biomolecular players and genetic changes, understanding the mechanical effects on these molecules could help elucidate disease mechanisms and develop novel therapeutic strategies for the neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric diseases in which these molecules are implicated.

In addition to neurons, as mentioned prior, several other classes of non-excitable cells exist within the CNS and PNS, i.e. glial cells (Figure 2B). Glial cells are implicated in many processes and greater emphasis has been placed on their role in diseases, especially from a mechanical perspective[330]. An example is the preferential growth and extension of astrocytes and other glial cells on harder substrates relative to neuronal cell’s preference for softer substrates. Astrocytes serve as a director of synaptic plasticity by forming a tripartite complex with the pre and post-synaptic terminals of neurons, which are poised in a likely position to play a neuromechanobiological role and an increasing body of literature aimed at their mechanosensitivity seems to suggest the same[354,355]. For instance, in glaucoma, which is often characterized by a high intraocular pressure (IOP) that results in nerve damage at the optic nerve head (ONH) and thus vision loss, a prevailing thought is that the lamina cribrosa at the ONH sustains pressure induced damage[356]. However, in rats that lack a lamina cribrosa, the same increased pressure induced glaucomatous phenotype is observed. Increasing efforts and focus have thus been placed at the astrocyte[356–358], which may even experience changes that precede nerve axonopathy[359]. Astrocytes normally maintain the ECM within the ONH, but in response to pathological deformation they are shown to transition from a quiescent phenotype to a reactive, proliferative one[358]. These reactive astrocytes are thought to remodel the ONH via synthesis of ECM proteins and matrix metalloproteinases[360,361]. They are strengthened along the radial axis by dense cytoskeletal beams of tubules and filaments, which were hypothesized to act as potential mechanical transducers of altered IOP[357]. In addition, astrocytes have been shown to maintain connections with the basement membrane at the ONH through β1 integrin and α-dystroglycan and upon IOP elevations, a disruption in these connections is shown by both an abnormal increase in extracellular space as well aslack of astrocytic adherence[362]. Fibroblasts in the experimental glaucomatous eye also display an increase in integrin mediated signaling of kinase and actin cytoskeleton pathways[363].

The role of mechanics is also important to the BBB, which experiences shear stress from the blood flow sensed by endothelial cells. Shear stress has been shown to modulate endothelial cell cytoskeletal protein content, glucose metabolism, and the expression of integrins, vascular adhesion molecule, and tight and adherent junction CAMs[364]. As such, it would prove valuable to assess how the BBB is modulated by shear stress in addition to other factors in the context of altered BBB in disease states. In addition to endothelial cells, pericytes, along with vascular smooth muscle cells, glial and neuronal cells, comprise what is known as the neurovascular unit[365,366]. The neurovascular unit has recently been recognized to have a role in BBB integrity and can control capillary diameter bidirectionally in whole retina and cerebellar slices[367]. This communication between neurons and vasculature is known as neurovascular coupling. Not only is it necessary for normal physiological function but it also plays an important role in neurodegenerative disorders[368] as well as ocular diseases such as diabetic retinopathy[369] and glaucoma[370]. These microvascular pericytes have contractile proteins such as muscle (alpha-smooth) and nonmuscle (beta and gamma) actin[371], which have been extensively studied in other mechanobiology subfields, but seems to have been largely ignored in the pericyte function. Alterations in the BBB have also been implicated in ischemic stroke. Despite the many studies in peripheral vasculature, the direct links between mechanotransductive processes to vascular pathology that reduces BBB integrity as a result of stroke are still missing[372].

Therapies and engineering solutions to disease stemmed from neuromechanobiology

Besides relating dysfunctional neuromechanobiology to diseases in the CNS, it is natural to extend the mechanical approach and perspective to finding therapies or solutions to disease, as depicted in Figure 3B. In general, a better understanding of neuromechanobiology can be harnessed for biomedical engineering applications via synthetic biology[373] and biomaterials such as piezoelectric scaffolds as smart materials for neural tissue engineering[374], where it has been demonstrated that, in addition to proper mechanical input via substrate stiffness[20], proper electrical input is necessary for therapeutic applications such as nerve regeneration using advanced biomaterials[375–377]. Take glaucoma for example. Better evaluation of the direct role of mechanical events in glaucoma and nerve pathology help delineate disease progression and thus therapeutic strategies. One proposed strategy is the development of in vitro 3D collagen gels that mimic the ECM and ONH deformation due to elevated IOP that can simultaneously compress astrocytes seeded in the gels[378]. This could potentially be taken further into organoid models that allow for simultaneous testing and interaction of astrocytes with neurons and axons in the context of disease and normal physiology for better understanding and better therapies. Another example relates to solid stress exerted by brain tumors on brain parenchyma. The extreme softness of brain tissue makes it susceptible to deformation and damage, not only due to large stresses exerted during trauma but also by the small compressive stresses arising from tumor growth. Solid stress generated by tumors in the brain has been shown to deform neighboring normal brain parenchyma, causing malfunction of nearby neuronal cells with subsequent behavioral deficits[379,380]. It was further shown that the pathological and behavioral deficits can be partially prevented and reversed by lithium administration and stress removal respectively, although the exact mechanism is unknown. It stands to reason that understanding the mechanobiology of stress effects on tumor growth, CNS cell responses, and tissue remodeling may lead to better therapeutic targets. Not only may glial cells act as modulators of mature synapses as in the case of the previously mentioned astrocytes, but they may also be important in neurodevelopment and mechanosensation for axon guidance and neuronal pathfinding. Just beyond the eye for instance, in the cochlea (where a significant body of mechanobiology literature already exists), glial cells not only impact growth rates of spinal ganglion neurons that project to the CNS, but also form a “scaffolding” of chains that precedes spinal ganglion neuron projections and radial bundles along the migratory path[381]. These recent findings could be used in the future for therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring hearing loss either through implantable devices, hydrogels for regenerating lost neuronal projections, or something entirely new.

Neuromechanobiology is also relevant to the question of how and why exercise is beneficial. Numerous papers have shown the beneficial effects of exercise on a myriad of cell-types and systems. Also, extensive work has been done to elucidate the biochemical signaling pathways involved in the mechanism of this positive outcome. Yet, little had been done on the mechanical mechanism behind the biochemical and physiological effects of exercise. Using treadmill running and a passive head motion controlled physical stimulation to induce CSF shear stress, a recent study showed that increased shear stress led to internalization of serotonin receptors (5-HT2a subclass) the absence of which reduces anxiety-like behavior in mice and is associated with many psychiatric disorders[382]. This was abolished when interstitial fluid movement was inhibited, thus showing how the mechanical load of exercise plays a role in the molecular and physiological outcomes.

The studies of substrate stiffness[29,30,32], patterning and geometry[31,60,170,383–385], and roughness[65] on axonal elongation, neurite extension and migration in the past decade have generated better-suited regenerative strategies. For instance, CNS and PNS regenerative studies have been guided by different modalities of substrate properties as a cue for cell sensing in development in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical progenitors for cortical tissue engineering[36], neuromuscular tissue engineering[386], correctly aligned axon regrowth[20], reconstruction of a rat sciatic nerve as a model for nerve grafting[35], and even in vitro organoid models that promote neural cell cultures. Such models function more similarly to in vivo neurons for the testing and development of novel therapeutic strategies or platforms to study neuronal cell cultures[37]. The strategies of controlling the substrate viscoelasticity, spatial patterning, and nano-topology for biomedical applications can be combined with a plethora of other customization capabilities such as controlled release of biological factors and drugs, repair-site shape conformation etc. The ECM of nervous tissue is rich in glycosaminoglycan polysaccharides such as hyaluronic acid (HA) and chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycans (CS GAGs)[387,388]. Rational material design strategies using HA and CS GAG matrices have shown tremendous promise in preclinical models of spinal cord injury (SCI), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and stroke[389–393]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that cationic biomaterials, when implanted in rodent brains, lead to a foreign body response that is detrimental to brain parenchyma[394]. Cationic interfaces resulted in stromal cell infiltration, peripherally derived inflammation, neural damage and amyloid production. In contrast, they noted that nonionic and anionic formulations of hydrogels resulted in minimal levels of these responses resulting in better resorption and molecular delivery. This study provides additional design criteria for rational biomaterial design for the CNS. In addition to biomaterials strategies, cell transplantation can be used in the CNS for treatment of focal injuries (SCI, TBI, stroke) or chronic degenerative disorders (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s etc.). From this perspective, biomaterial-based strategies (with or without cell transplantation) are an important component of the toolkit to engineer tissue repair and regeneration. Precisely designed biomaterials offer possible control over cell survival, differentiation, integration, and modulating the host immune response[395,396].

In general, force is a potent stimulus for axonal growth, with the elongation rate being directly proportional to the magnitude of tension[6,397]. From a translation perspective, one immediate application of stretch growth is ex vivo development of elongated nerve conduits that are ready to transplant for peripheral nerve repair[398]. Interestingly, in models of cyclic low magnitude strain, it was shown that glial cells exhibited signs of inflammatory reactive gliosis, and neurons became vulnerable to apoptosis[399]. This finding is important in the context of brain-machine interfaces (BMIs), where the implanted electrodes, which are orders of magnitude stiffer than CNS parenchyma, lead to micromotion and subsequent low magnitude strain on neurons and glia. Several research efforts are focusing on reducing this mismatch of mechanical properties between neural electrodes and CNS tissue by using hydrogel-based coatings/substrates or ECM based matrices for reliable brain-machine interfacing; a technology that offers great hope for functional restoration after multiple CNS pathologies (SCI, TBI, Parkinson’s disease etc.)[400,401].