Abstract

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are a heterogenic population of immature myeloid cells with immunosuppressive effects, which undergo massive expansion during tumor progression. These cells not only support immune escape directly but also promote tumor invasion via various non-immunological activities. Besides, this group of cells are proved to impair the efficiency of current antitumor strategies such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and immunotherapy. Therefore, MDSCs are considered as potential therapeutic targets for cancer therapy. Treatment strategies targeting MDSCs have shown promising outcomes in both preclinical studies and clinical trials when administrated alone, or in combination with other anticancer therapies. In this review, we shed new light on recent advances in the biological characteristics and immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs. We also hope to propose an overview of current MDSCs-targeting therapies so as to provide new ideas for cancer treatment.

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Tumour immunology

Introduction

The overall survival of cancer patients has been greatly extended in recent years due to improved healthcare. However, malignant tumors still remain one of the leading causes of deaths around the world, with almost 10 million cancer deaths occurring in 2020.1 The great success of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy has attracted more and more studies focusing on immune cell populations and signaling pathways with immunosuppressive effects, in order to develop more efficient immunotherapeutic approaches. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), characterized by their suppressive effects on immune responses, are important motivators to promote tumor immune escape. MDSCs expand massively along with tumor progression, and play critical roles in tumor development, metastasis, and treatment resistance. There has been increasing evidence indicating that MDSCs are one of the fundamental features of malignant tumors, as well as potential therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.2

MDSCs originate from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) as a result of an altered myelopoiesis. At steady-state, myelopoiesis is a structured process to sustain the stable supply of host myeloid cells. Bone marrow (BM)-derived HSCs give rise to immature myeloid cells (IMCs), which terminally differentiate into monocytes (further differentiating into macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs)) and granulocytes (including neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils). A variety of pathological conditions such as infection or tissue damage can initiate emergency myelopoiesis to eliminate the potential threats to the host.3 In these conditions, myeloid cells rapidly mobilize from the BM and are classically activated in response to pathogenic signals such as toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), resulting in dramatic increases in phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines.4 This transient myelopoiesis terminates upon the elimination of stimulus, and then the homeostasis of myeloid cells is restored. However, some pathological conditions such as chronic inflammation, cancer, and autoimmune disease can lead to an aberrant, sustained myelopoiesis to prevent the host from extensive tissue damage caused by unresolved inflammation.5–7 In these conditions, persistent inflammation signals make IMCs deviate from normal differentiation and pathologically activated. Compared to physiologically differentiated myeloid cells, these IMCs have distinct features such as immature phenotypes and morphologies, relatively weak phagocytic activities, as well as anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions, which are now collectively termed as MDSCs.6

In recent years, studies on the role of MDSCs in cancer have profoundly expanded our knowledge of tumor pathobiology. MDSCs are characterized by their abilities to suppress immune responses and shield tumor cells from the host immune attack. Besides, they also contribute to tumor progression through various non-immunological mechanisms such as promoting vascularization and pre-metastatic niche formation.8 MDSCs expansion has been observed in both cancer patients and tumor-bearing mice, and the frequencies of MDSCs in circulation and tumor site are correlated positively with tumor burden but negatively with antitumoral therapy response and overall survival (OS) in tumor-bearing hosts.9–11 In addition, numerous studies have indicated that MDSCs act as a valuable prognostic biomarker for cancer development, as well as a potential target for anticancer therapies.12,13 Currently, multiple novel drugs targeting MDSCs have been investigated in preclinical and clinical studies. At the same time, a number of conventional drugs have been reported to be effective in depleting MDSCs and consequently improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.14

In this review, we delineated the development and characteristics of MDSCs, as well as their biological roles in tumor progression, and reviewed current MDSCs-targeting approaches. In summary, this review provides an overview of the characteristics and immunosuppressive roles of MDSCs, along with a detailed discussion on MDSCs-targeting therapies in cancer.

A brief history of MDSCs investigation in cancer

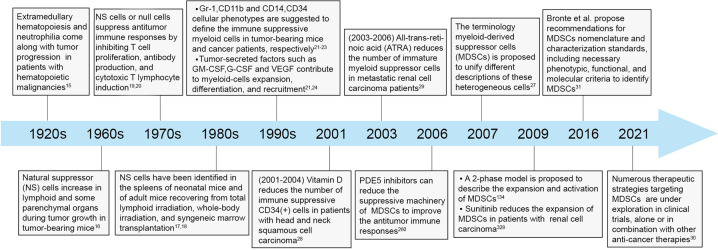

Studies of MDSCs in cancer can be traced back to the early 1900s when Sonnenfeld et al. found that extramedullary hematopoiesis and neutrophilia came along with tumor progression in patients with hematopoietic malignancies.15 In the mid-1960s, pathologic leukemoid reaction and increased myeloid cells infiltration were found in A-280 tumor-bearing mice, which were motivated by tumor-derived factors and were positively associated with tumor growth.16 In addition, these myeloid cells had also been found in inflammatory and hematopoietic processes, such as the spleens of neonatal mice and the spleens of adult mice receiving total lymphoid irradiation.17,18 In the 1970s, these abnormal myeloid cells were identified to have the properties to inhibit antibody production, T cell proliferation, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) induction, and were described as natural suppressor (NS) cells, veto cells, or null cells in disparate studies due to the lack of classic membrane markers of T cells, B cells, natural killer cells (NKs), or macrophages.19,20 Until the late 1990s, the surface markers Gr-1 and CD11b were identified to define these immune suppressive myeloid cells in tumor-bearing mice.21 Also, in cancer patients, these populations of myeloid cells were described based on their expression of CD34 and CD14 as well as their capabilities to suppress T cells.22,23 Nevertheless, descriptions of these cells in later investigations were diverse, including myeloid suppressor cells (MSCs), immature myeloid cells, and Gr1+ myeloid cells.24–26 Until 2007, the MDSCs terminology was proposed to describe these heterogeneous cells, and most investigators accepted this nomenclature since then.27 Around that period, studies on the strategies targeting these clusters of cells also made meaningful progress. Notably, in the early 2000s, vitamin D and all trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) administration were demonstrated to induce the differentiation of immature myeloid cells and reduce their immunosuppressive function in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) respectively.28,29 After that, new drugs were developed increasingly to target MDSCs, most of which could induce a superior tumor control when added to the existing therapeutic regimens. More importantly, several conventional drugs have shown synergistic effects in cancer patients by effectively depleting MDSCs when combined with traditional antitumor therapies (Fig. 1).30 It is foreseeable that MDSCs-targeting therapies will become an important compliment to current cancer treatment strategies in the near future.

Fig. 1.

Historical progression in the investigation of MDSCs.

Development and characteristics of MDSCs

Based on the density, morphology, and phenotype, MDSCs fall mainly into two subsets: polymorphonuclear (PMN)-MDSCs and monocytic (M)-MDSCs. PMN-MDSCs were initially termed as granulocytic (G)-MDSCs. Gradually, the term PMN-MDSCs gained more popularity, since it makes this cluster of cells distinguishable from steady-state neutrophils in the aspects of morphology and phenotype (such as having altered buoyancy, less granules, reduced CD16, CD62L, and upregulated CD11b, CD66b).31 Additionally, a group of more immature progenitor cells are defined as “early-stage MDSCs” (eMDSCs) with the phenotype of CD11b+Gr-1+CCR2+Sca1+CD31+ in mouse and CD33+HLA-DR− Lin− in human.31–33 Besides, a unique population of fibrocystic MDSCs (F-MDSCs) has been described and characterized in human.34,35

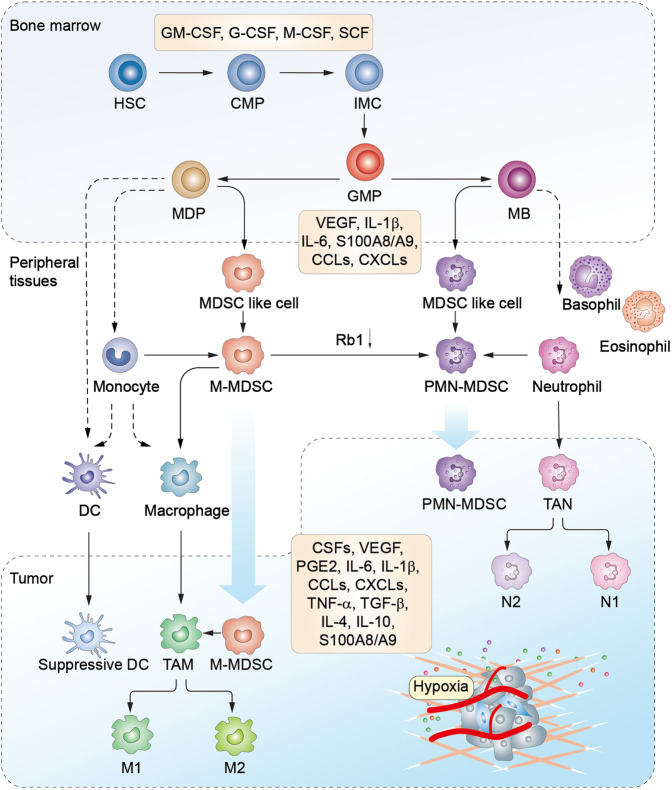

A two-phase model was proposed to describe the development of MDSCs in the context of cancer.36 The first expansion phase involves IMCs proliferation in the BM, which is induced by various factors produced by tumors or the BM stroma.36 Currently, it has been gradually accepted that during myelopoiesis in the BM, a similar procedure referred to as extramedullary myelopoiesis is initiated in the peripheral organs, such as spleen.37 The second activation phase involves the conversion of IMCs to MDSCs in peripheral tissues, which is mainly motivated by pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from tumor-associated stromal cells and activated T cells. This 2-phase model suggests that the accumulation of MDSCs is realizable only when the signals of the two phases are provided simultaneously.38 Recently, Karin proposed a four-step event to characterize the development of MDSCs (step I–IV: myelopoiesis, mobilization to the blood, homing to the tumor site, retention at the tumor site) from a migratory viewpoint (Fig. 2).39 This model is not contrary to the two-phase model, but adds two additional steps (III, IV) to provide detailed and complementary information associated with the migratory properties of MDSCs. On the other hand, the signal factors initiate all the processes mentioned above through inducing crosstalk between HSCs and tumor tissues. Overall, these signals overlap significantly. It involves growth factors including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte (G)-CSF, macrophage (M)-CSF, stem cell factor (SCF),40 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-1β, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,41 transforming growth factor (TGF)-β,42 and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2); alarmins like high-mobility grow box-1 (HMGB1)43 and S100 calcium-binding protein A8/A9 (S100A8/A9); chemokines such as C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CXCL5), and CXCL12; enzymes like cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). These signals also include tumor-derived exosomal proteins, RNAs, and microRNAs.44 Furthermore, these signals form an interactive communication network under the modulation of transcription factors,45 such as signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-β (C/EBPβ), and NOTCH (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of MDSCs development, recruitment, and differentiation. In the bone marrow (BM), hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)-derived common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) give rise to granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) expansion. GMPs further differentiate into macrophage/dendritic cell progenitors (MDPs) and myeloblasts (MBs). This myelopoiesis process is controlled by growth factors such as GM-CSF, G-CSF, M-CSF, and SCF, etc. In normal physiological condition, as illustrated with the dotted line, MDPs further increase and are converted to macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). MBs are further converted to granulocytes including basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Under cancer conditions, lager population of immature myeloid cells (IMCs) are pathologically activated and then differentiate into M-MDSCs and PMN-MDSCs in the presence of tumor-derived factors such as VEGF, IL-6, and IL-1β, etc. In early tumor stages, cells with similar biochemical features as MDSCs do not have suppressive activity, and are reffered as MDSC-like cells. MDSCs may also arise partially from reprogramming of the existing differentiated monocytes and polymorphonuclear cells. M-MDSCs can differentiate into PMN-MDSCs through transcriptional silencing of the retinoblastoma gene (Rb1). MDSCs are recruited into peripheral tissues and tumor microenvironment (TME) under chemotaxis of several factors, such as CCL2, CXCLs, and S100A8/A9, etc. In the TME, M-MDSCs can further differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and TAMs may acquire M1 or M2 phenotypes. Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) can be classified as tumor-inhibitory N1 and tumor-promoting N2 subtypes. M1, type 1 TAM; M2, type 2 TAM; N1, type 1 TAN; N2, type 2 TAN.

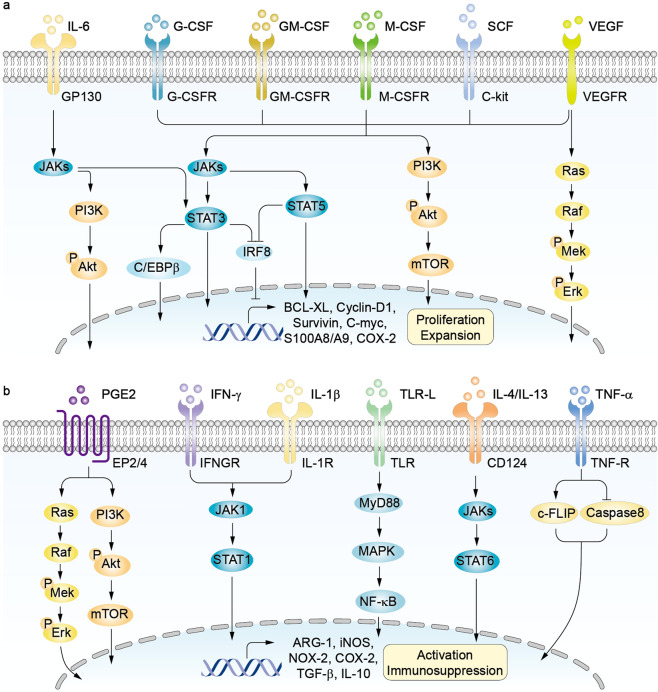

Fig. 3.

Signaling pathways of MDSCs expansion and activation. a CSFs, SCF, IL-6 and VEGF are key promoters of MDSCs proliferation and expansion. The process is regulated by JAKs-STATs, PI3K-Akt, and Mek-Erk signaling pathways, leading to the expression of BCL-XL, Cyclin-D1, and C-myc in MDSCs. MDSCs expansion is inhibited by interferon-related factor 8 (IRF-8). G-CSF and GM-CSF downregulate IRF-8 expression through modulation of STAT3 and STAT5, respectively. b Numerous cancer-associated factors mediate the activation and immunoregulatory function of MDSCs. PGE2 activates EP2/4 signaling through Mek-Erk and PI3K-Akt pathways. IFN-γ and IL-1β activate MDSCs through JAK1-STAT1 pathway. Proinflammatory danger signals such as S100A8/A9 proteins and high-mobility grow box-1 (HMGB1) enhance MDSCs trafficking and function by binding to TLRs. IL-4 and IL-13 function through IL-4Rα-dependent STAT6 activation. TNF-α activates TNF-R signaling by upregulating cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (c-FLIP) expression and by suppressing caspase-8 activity. All these signals can induce the expression of inhibitory factors such as ARG-1, iNOS, NOX-2, COX-2, TGF-β, and IL-10 in MDSCs.

Expansion and recruitment of MDSCs

Several unique mechanisms involved in the development of MDSCs have been proposed and verified in recent years. CSFs (G-CSF, GM-CSF, and M-CSF) were demonstrated to drive emergency hematopoiesis in tumors by upregulating a critical transcription factor, retinoic-acid-related orphan receptor C1 (RORC1).46 Additionally, GM-CSF and G-CSF negatively regulate interferon-related factor 8 (IRF-8) through STAT3 and STAT5 signaling pathways to reverse IRF-8-mediated hindering effect on MDSCs formation.47 Recently, reduced retinol metabolism and attenuated retinoic acid (RA) signaling were proved to provide a possible driving force that fostered the generation of PMN-MDSCs in colorectal tumors.48 On the other hand, infiltration of newly formed MDSCs to tumor sites are recruited by tumor-associated C–C and C–X–C motif chemokines and their receptors.49 These chemokines are not unique for specific cancer types and have high redundancy to sustain the constant migration of MDSCs. The CCL2/CCR2 axis is the main pathway implicated in monocytes/M-MDSCs migration,50 while neutrophils/PMN-MDSCs are recruited mainly by the CXCLs-CXCR1/2 axis.51 Moreover, it was found that the expression of chemokine CCL26 in tumor cells induced the accumulation of CX3CR1+ MDSCs,52 and the CCR5/CCR5 ligand axis also supported the maintenance of MDSCs in the tumor niches.53

Differentiation of MDSCs

At the early stage of cancer, MDSCs are rarely detectable, however, there are a group of cells sharing similar genomic and biochemical characteristics with MDSCs but lacking immunosuppressive activities, which are termed as MDSC-like cells.31,54 There is a controversy concerning the origin of MDSCs. Single-cell transcriptomics revealed that MDSCs derived from distinct clusters of neutrophilic and monocytic lineages55, while another hypothesis proposed that MDSCs arose partially from reprogramming of classical monocytes and polymorphonuclear cells.56 In addition, MDSCs in the periphery and tumor tissues can further differentiate. It was recently reported that a large proportion of M-MDSCs could differentiate into PMN-MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice, and transcriptional silencing of the retinoblastoma gene (Rb1) via epigenetic modifications by histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC-2) mediated this phenotype conversion.57 In the periphery, the existence of tumor-derived inflammatory factors promotes the differentiation of M-MDSCs into immunosuppressive macrophages as well as inhibits the functional maturation of DCs. Whereas in the hypoxic TME, M-MDSCs can differentiate into tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs).58 A recent study reported that tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs downregulated STAT3 activity via hypoxia-induced activation of CD45 phosphatase to promote their rapid differentiation into TAMs.59 Additionally, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are classified into N1 (tumor-inhibitory) and N2 (tumor-promoting) subtypes based on their functional differences.60 It was hypothesized that N2 TANs in the TME were either periphery-recruited PMN-MDSCs or periphery-derived neutrophils, which obtained an N2 phenotype under the stimulation of TGF-β. Based on the N1/N2 classification, N2 neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs appear to be equivalent or the same population essentially.61 Therefore, a better definition of PMN-MDSCs is necessary to provide a consensus, especially within the context of the N1/N2 classification.

Functional regulation of MDSCs

Different mechanisms are involved in the regulation of immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs. It was reported that MDSCs dramatically upregulated TAM RTKs (TYRO3, AXL, MERTK transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases) and the corresponding ligands to mediate immunosuppression in tumor-bearing mice and metastatic melanoma patients.62 A recent study revealed that the long noncoding RNA Pvt1 (lncRNA Pvt1) also significantly regulated the immunosuppressive activities of PMN-MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice.63 More importantly, tumor represents a special state of stress, which is thought to greatly contribute to the generation and suppressive function of MDSCs.64,65 MDSCs derived from cancer patients and tumor-bearing mice were found to overexpress endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress markers such as C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and spliced X-box binding protein 1 (sXBP1),58 furthermore, the ER stress response level was substantially higher at the tumor site than in the peripheral lymphoid organs in tumor-bearing mice.65 Interestingly, activation of stress-induced β2-adrenergic receptors (ARs) and expression of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated TIPE2 (TNF-α-induced protein 8-like 2) in MDSCs were both reported to mediate the immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs.66,67 In summary, these mediators may be regarded as promising therapeutic targets to reduce MDSCs-mediated immunosuppression in cancer.

Survival of MDSCs

MDSCs turnover varies with cancer types, with a half-life of a few days. Activated T cells contribute to this rapid turnover of MDSCs since FasL+ T cells can induce the apoptosis of Fas+ MDSCs.68 Additionally, it has been found that MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice had a shorter half-life and lower viability than classical neutrophils and monocytes because of increased apoptosis mediated by the ER stress-induced expression of TRAIL-Rs (TNF-related apoptosis-induced ligand receptors) in MDSCs.65 However, MDSCs also have some anti-apoptosis mechanisms. It was demonstrated that the inflammatory environment could increase MDSCs resistance to Fas-FasL signaling-mediated lysis, resulting in a longer half-life of MDSCs in vivo.69 MDSCs were also proved to increase BCL-XL (B cell lymphoma XL) expression to deregulate Fas-FasL signaling-induced apoptosis and to escape the elimination by host CTLs.70 More importantly, it was found that M-MDSCs required continuous c-FLIP (cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein) expression to prevent cell death, whereas PMN-MDSCs required the anti-apoptotic molecule MCL-1 (myeloid cell leukemia 1) to counter the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.71 Besides, TNF was also reported to promote MDSCs survival by upregulating c-FLIP and inhibiting the activity of caspase-8.72

Identification of MDSCs

At present, the same phenotypical characteristics used to identify neutrophils and monocytes are also used for identifying PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs, respectively. However, some newly reported methods and molecular markers may help to further distinguish these two pairs of cells.5,31,73

One method allowing for the distinguishment between PMN-MDSCs and neutrophils in the peripheral blood is the standard Ficoll gradient centrifugation. In healthy individuals, PMN-MDSCs are rarely detectable in the peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) fraction. In tumor-bearing hosts, the high-density fraction of neutrophils (HDNs) are classical neutrophils which were previously described as N1-type neutrophils (Nc1), which have antitumor effects such as phagocytosis and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity. The low-density fraction (mononuclear cell fraction) consists of at least two morphologically distinct neutrophil subsets: activated mature neutrophils (circulating N2-type neutrophils, Nc2) and immature PMN-MDSCs,74 and both subsets display pro-tumor properties.75 Mature Nc2 in the low-density fraction are derived from mature HDNs in a TGF-β-dependent manner. Since low density and immunosuppressive activity are two defining characteristics of PMN-MDSCs as described in numerous studies, both mature Nc2 and immature PMN-MDSCs can be qualified as MDSCs.74 Therefore, there is a need for a unified nomenclature of immunosuppressive neutrophils.76 Nevertheless, this method has some limitations: some PMN-MDSCs can pass through the low-density gradient and in turn contaminate HDNs, and the results rely heavily on the collection and storage conditions of the blood. On the other hand, there are no established methodologies currently to unequivocally distinguish between PMN-MDSCs and immunosuppressive TANs in tumor tissues.77 Notably, LOX-1 (lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor 1) was identified recently in humans to separate PMN-MDSCs from neutrophils without the need of gradient centrifugation.78 In cancer patients, LOX-1+ immunosuppressive cells with PMN-MDSCs features accounted for 5–15% of neutrophils in the blood and up to 50% of neutrophils in tumor tissues.79 However, these cells were practically undetectable in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals.

M-MDSCs and classical monocytes can be discriminated based on MHC-II molecules expression in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. M-MDSCs have the CD11b+CD14+CD15–CD33+HLA-DR–/lo phenotype, whereas monocytes are HLA-DR positive.76 However, phenotype alone is possibly insufficient to fully distinguish M-MDSCs from monocytes, making the distinguishment between this pair of cells in tumor-bearing mice much more challenging. Fortunately, a recent study on single-cell RNA sequencing in breast cancer confirmed that cell surface receptors CD84 and JAML (junction adhesion molecule like) could be used in combination with CD11b/Gr-1 or CD11b/CD15/CD14 to detect MDSCs in mouse breast cancer model and breast cancer patients, respectively. However, it remains to be determined whether these findings are applicable to other cancers.55 Additionally, Khan et al. recently found that, among the cells with e-MDSCs phenotype markers in patients with ovarian cancer, 58% in blood and 36% in ascites were basophils on the basis of cytology and high CD123 expression, while immature cells were rare. This suggests that e-MDSCs phenotype markers need to be re-evaluated to exclude basophils.80

Therefore, future studies in terms of genomic, proteomic, molecular, and functional characterizations are wanted to specifically identify MDSCs populations.81 Bronte et al. proposed an algorithm including necessary phenotypic, functional, and molecular criteria to identify MDSCs, which provides a unified framework for future MDSCs research.31

MDSCs-mediated tumor-promoting effects

MDSCs utilize multiple mechanisms to dampen antitumor immunity and promote tumor progression. For one thing, MDSCs contribute to the formation of an immunosuppressive milieu which in turn exerts influence on the biology and function of MDSCs. For another, MDSCs also support tumor progression and induce antitumoral therapy resistance in various non-immunological manners.

MDSCs-mediated suppression on immune responses

The immune defense system, mainly comprising cytotoxic T lymphocytes, NK cells, antigen presenting cells (APCs), and B cells, is indispensable in tumor control and elimination although it is always disrupted by immune inhibitory cells. Notably, in tumor-bearing hosts, MDSCs play a critical role in facilitating tumor immune escape by inhibiting tumoricidal immune cells as well as through acting in league with other inhibitory immune cells.

Expression of negative immune checkpoint molecules

Numerous studies have revealed that MDSCs increase PD-L1 expression to induce T-cell anergy through interacting with PD-1 on T cells.82,83 Tumor-infiltrating MDSCs always come with higher PD-L1 expression compared with their counterparts in the periphery, indicating their acclimatization in the hypoxic microenvironment.82,83 Interestingly, Cassetta et al. reported that in cancer patients, profound PD-L1 expression was restricted to M-MDSCs and e-MDSCs, whereas LOX-1 expression was confined to PMN-MDSCs.7 Besides, MDSCs also express cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), although the specific regulating mechanism is unclear. Blocking CTLA-4 has been reported to dampen the accumulation of granulocytic MDSCs and reduce their arginase 1 (ARG1) production in the peripheral blood of patients with metastatic melanoma.84

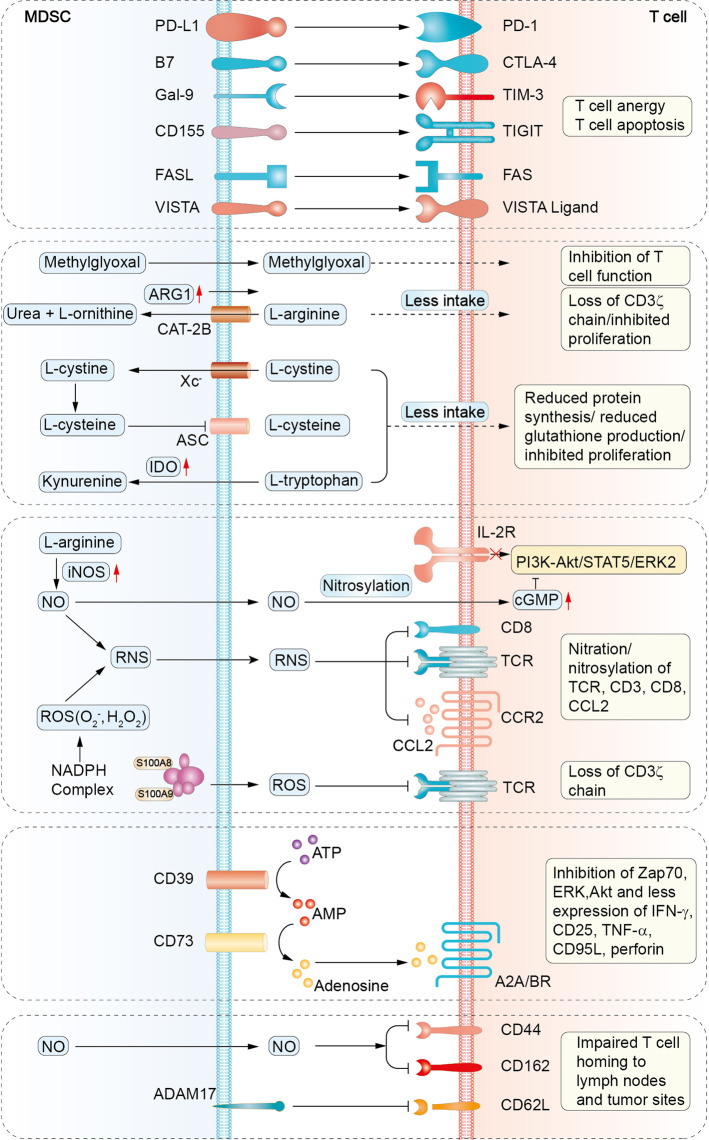

Recently, some other immune checkpoint molecules, such as VISTA (V-domain Ig-containing suppressor of T-cell activation), Gal-9 (galectin-9), and CD155, have been reported in MDSCs-mediated immunosuppression (Fig. 4). In the peripheral blood of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, high VISTA expression on MDSCs was positively associated with T cell-expressed PD-1,85 while blockade of VISTA was proved to allow the restoration of the protective antitumor response in mouse melanoma models.86 Additionally, T cell-expressed TIM-3 (T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 3) can interact with Gal-9 on MDSCs to promote MDSCs expansion and suppress T cells responses.87 The TIM-3/Gal-9 pathway was demonstrated to be critical in primary and secondary resistance to anti-PD-1 treatment in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients.88 Gal-9 has also been reported to promote myeloid lineage-mediated immunosuppression in TME by enhancing the degradation of STING.89 Moreover, TIGIT (T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain) is an inhibitory regulator expressed on T lymphocytes, and the TIGIT/CD155 pathway is involved in tumor-infiltrating T cell exhaustion.90,91 Recent studies have indicated that CD155 expression on MDSCs contributes to MDSCs-mediated T cell inhibition, and targeting the TIGIT/CD155 pathway in vitro with anti-TIGIT antibody significantly abrogated the immunosuppressive activities of MDSCs.92 In summary, these researches suggest that immune checkpoint molecules expressed on MDSCs negatively regulate T cells functions.

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms of MDSCs-mediated T cells suppression. MDSCs suppress T cell activity through distinct mechanisms including expression of negative immune checkpoint molecules, depletion of amino acids necessary for T cell response, production of NO, ROS, RNS, generation of adenosines, and impairment of T cell homing to peripheral lymph nodes and tumor sites. TIM-3, T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3; Gal-9, galectin-9; TIGIT, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain; VISTA, V-domain Ig-containing suppressor of T-cell activation; CAT-2B, cationic amino acid transporter 2B; ASC, asctype amino acid transporter; Xc–, cystine–glutamate transporter; IDO, indole-2,3 dioxygenase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; TCR, T cell receptor; Zap70, zeta-associated protein 70; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; Akt, protein kinase B; ADAM17, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17.

Depletion of amino acids required for T cell response

MDSCs are notorious for deprivation of essential amino acids required for T cells metabolism and function. Large amounts of TME-derived factors, such as HIF-1, TGF-β, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ, can induce the expression of CAT-2B (cationic amino acid transporter) and ARG1 in MDSCs.93,94 CAT-2B rapidly transfers extracellular L-arginine into MDSCs, which is subsequently degraded into urea and L-ornithine under the catalysis of ARG1.94 Consequently, the deficiency of arginine in the extracellular space can lead to the CD3ζ chain loss and apparent proliferation inhibition of T cells.95 In cancer patients, MDSCs were reported to release ARG1 into the extracellular environment, which also resulted in a consumption of extracellular L-arginine and further facilitated T cells inhibition in a similar manner.96 Notably, MDSCs have been recently reported to induce T cell suppression through the cell–cell transfer of methylglyoxal into T cells. Methylglyoxal suppressed T cells not only through depleting cytosolic L-arginine but also by rendering L-arginine-containing proteins non-functional through glycation.97 In addition, MDSCs can uptake cystine and metabolize it into cysteine. However, due to the lack of neutral amino acid transporter, MDSCs cannot export cysteine back to the extracellular environment, leading to the deprivation of cysteine for T cell activation.98 Furthermore, depletion of tryptophan through IDO in MDSCs can induce T cell autophagy, cell cycle arrest, and even cell death.99

Production of NO, ROS, and RNS

MDSCs secrete a serious of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species to damage T cell function. Upregulated inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in MDSCs metabolizes L-arginine into nitric oxide (NO) and L-citrulline. NO drives several molecular blockades in T cells, including interference with IL-2R signaling and nitration of T cell receptors (TCRs) specific for the peptides presented by MDSCs.100,101 ROS, comprising oxygen radicals (such as superoxide anion, O2−), hydroxyl radicals, and non-radicals (such as hydrogen peroxide, H2O2), are generated in high amounts by the NADPH oxidase isoform (NOX-2) in MDSCs. ROS not only play an important role in oxidative stress of MDSCs, but also catalyze the nitration of TCR/CD8 molecules to prevent the TCR/MHC-peptide interactions.102 Furthermore, O2− combines with NO rapidly to produce reactive nitrogen species (RNS) such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which can induce the nitration/nitrosylation of TCR/CD8 molecules and further elicit an altered TCR/MHC-peptide recognition.103,104 Notably, RNS were reported to induce the posttranslational modification of CCL2, and the reduced affinity of CCL2 to CCR2 consequently inhibited the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to tumor tissues.105 However, it does not lead to complete loss of myeloid cells function, because myeloid cells have higher CCR2 expression levels than CD8+ T cells.105

Adenosines and adenosine receptors

The immunosuppressive factor adenosine has also been proved to participate in MDSCs-mediated T cell suppression.106 Hypoxic tumor tissues release high amounts of adenosine triphosphates (ATPs) in the extracellular space, which are immediately degraded into adenosines. In this process, CD39 converts ATP to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and/or adenosine monophosphate (AMP), and CD73 catalyzes the generation of adenosine from AMP.107 The accumulated extracellular adenosines activate downstream signaling pathways through adenosine receptors: A2AR, A2BR (both are typically associated with profound immunosuppression), A1R, and A3R. In the TME, these adenosinergic molecules (CD39, CD73, A2AR, and A2BR) are generally expressed by tumor cells as well as stromal and immune cells, forming a positive feedback loop. This feedback produces a constant stream of adenosines, which not only facilitate the development and immunosuppressive capability of MDSCs, but also impair the activities of tumoricidal immune cells, including T cells, DCs and NK cells.108 In a mouse melanoma model, Umansky et al. proposed that tumor cells, MDSCs, and regulatory T cells (Tregs) could generate extracellular adenosines in a paracrine manner to inhibit T-cell function.109 Moreover, it was reported that a fraction of activated MDSCs from NSCLC patients expressed both CD39 and CD73, which was correlated with cancer progression and chemotherapy resistance.110

Impairment of T cell trafficking

MDSCs utilize a variety of ways to impair T cells trafficking in tumor-bearing hosts. ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17) expressed on MDSCs directly cleaves the ectodomain of L-selectin (CD62L) on naive T cells to inhibit them homing to peripheral lymph nodes and tumor sites.111 Moreover, downregulation of CD44 and CD162 on T cells by M-MDSCs-derived NO can damage T cells extravasation and tissue infiltration.112 In addition, NO was also reported to decrease E-selectin expression on tumor vessels, thereby inhibiting T cells trafficking to tumor tissues.113

Crosstalk between MDSCs and other immune cells

Apart from T cells, MDSCs also deliver immune inhibition on other tumoricidal immune cells such as NK cells, DCs, and B cells. It was reported that membrane-bound TGF-β1 on MDSCs contributed to suppressing the innate immune function of NK cells in mouse tumor models.114 Moreover, M-MDSCs from liver cancer patients were found to cause autologous NK cells anergy in vitro, mainly via the interaction of NKp30 receptor on NK cells with NKp30 ligand on MDSCs.115 Additionally, PMN-MDSCs were reported to block antigen cross-presentation of DCs by transferring oxidized lipids from PMN-MDSCs to DCs in tumor-bearing mice.116 In melanoma patients, high frequencies of M-MDSCs in the starting culture of monocytes could inhibit DCs maturation and resulted in impaired overall quality of monocytes-derived DC vaccines.117 MDSCs also can impair the function of B cells to suppress humoral immune responses. In a lung cancer mouse model, MDSCs inhibited the differentiation and function of B cells by modulating IL-7 and downstream STAT5 signaling.118 In a breast cancer mouse model, MDSCs upregulated PD-L1 expression on B cells, and further transformed them into regulatory B cells (Bregs) which had higher inhibitory abilities on T cells.119 What’s more, splenic MDSCs from tumor-bearing mice were reported to downregulate the adhesion molecule L-selectin on splenic B cells, resulting in reduced B cells homing to lymph nodes.120

On the other hand, MDSCs can incite other immune inhibitory cells such as Tregs and TAMs to facilitate immunosuppression. In mouse tumor models, it was demonstrated that tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs could produce CCR5 ligands to chemoattract Tregs with high CCR5 expression into tumor tissues.121 Furthermore, MDSCs can induce Tregs proliferation through either a direct cell-cell interaction or secretion of soluble factors like IL-10 and TGF-β.122 The expression of ARG1, IDO, and CD40 by MDSCs have also been reported to participate in Tregs induction.123 Macrophage is another accomplice of MDSCs. The cell–cell interactions between MDSCs and macrophages can elicit a type 2 tumor-promoting immune response, which is mediated by elevated IL-10 production in MDSCs and downregulated IL-12 production in macrophages.124 Overall, MDSCs together with other immune suppressive cells build an inhibitory network, crippling the cytotoxic effects on tumor cells.

Non-immunological functions of MDSCs

Other than the effects on immune responses, MDSCs also contribute to tumor progression via multiple non-immunological mechanisms such as supporting angiogenesis, promoting stemness of tumor cells, facilitating epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and pre-metastatic niche formation.8,125 MDSCs not only exploit abundant VEGFs in the TME but also generate VEGFs themselves, creating a positive feedback loop to promote angiogenesis and stimulate their accumulation.126 Interestingly, MDSCs could directly induce vascularization and tumor invasion by secreting matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) and differentiating into endothelial-like cells (ECs).127 MDSCs were also reported to support vascularization by means of exosomes which not only release proangiogenic factors but also prime target cells to acquire a proangiogenic phenotype.128 In addition, it was reported that granulocytic MDSCs-derived exosomal S100A9 promoted colorectal cancer (CRC) stemness in a HIF-1α-dependent manner.129 MDSCs from ovarian carcinoma patients were demonstrated to trigger miRNA101 expression and repress the corepressor gene C-terminal binding protein-2 (CtBP2) in cancer cells, subsequently leading to increased cancer cell stemness and metastatic potential.130 What’s more, in specimens from breast cancer patients, the level of MDSCs correlated with the presence of cancer stem-like cells (CSCs).131 Additionally, in colorectal carcinoma mouse model, elevated CXCL1 in the premetastatic liver was found to recruit CXCR2+ MDSCs to form a premetastatic niche, which in turn promoted liver metastases.132 Furthermore, PMN-MDSCs were reported to inhibit NK cells-mediated killing of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and promote extravasation of CTCs through secreting IL-1β and MMPs in several mouse tumor models.133

Differences in suppressive functions between PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs

PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs are distinct in terms of the phenotype and morphology, and in addition, they have unique although partially overlapping functional characteristics.134 Upregulated ARG1, iNOS, and ROS in MDSCs mainly mediate the immunosuppression on T cells. Among them, ARG1-induced suppression does not need cell-to-cell contact, while iNOS and ROS-mediated inhibition require proximity of T cells and MDSCs.135 Notably, the immunosuppressive activities of M-MDSCs primarily depend on ARG1, NO, and cytokines like IL-10 and TGFβ, which inhibit both antigen-specific and non-specific T-cell responses. However, PMN-MDSCs, whose functions mainly depend on high levels of ROS and RNS, primarily inhibit antigen-specific T-cell responses.136

Furthermore, the proportion and functional specialization of MDSCs differ in disparate tumor types and organs.137,138 In most mouse tumor models and cancer patients, PMN-MDSCs are predominantly detected in the peripheral lymphoid tissues and blood with relatively modest suppressive activities,7,139,140 while M-MDSCs are enriched in tumor tissues and rapidly differentiate into TAMs. In the TME, M-MDSCs are assessed to be more suppressive than PMN-MDSCs on a per-cell basis.141,142 These differences between PMN-MDSCs and M-MDSCs lead to more potent immunosuppressive properties of the total MDSCs population in tumor tissues compared with that in the periphery.

Recently, MDSCs subsets were reported to function in different spatiotemporal and sexual manners. In mouse tumor models, Ouzounova et al. demonstrated that tumor-infiltrated M-MDSCs promoted EMT/CSC phenotype to facilitate tumor cell dissemination from the primary sites. In contrast, pulmonary-infiltrating PMN-MDSCs supported the metastatic tumor growth through reverting EMT/CSC phenotype and promoting tumor cell proliferation.143 In glioblastoma (GBM) mouse models, proliferating M-MDSCs were predominant in the tumors of males, while a high PMN-MDSC/IL-1β gene signature was correlated to a poor prognosis in females. Moreover, chemotherapy was more efficient in targeting M-MDSCs in males, whereas IL-1 pathway inhibitor was more beneficial to inhibit PMN-MDSCs in females.144

Overall, the prevalence of a specific immunosuppressive mechanism depends on the MDSC subtypes, the tumor types/stages, and the organs/sites. Since the phenotype and function of MDSCs can change in response to local inflammatory factors, it is difficult to define particular markers predictive of their immune-suppressive properties.

Therapeutic strategies targeting MDSCs in cancer

The fact that MDSCs play critical roles in tumor progression and metastasis has inspired the search for therapeutic strategies targeting these cells, which can be broadly classified into five categories: (1) inhibiting MDSCs expansion and recruitment; (2) promoting MDSCs differentiation into mature myeloid cells; (3) inhibiting MDSCs function; (4) inhibiting MDSCs metabolism; (5) depleting MDSCs directly. Herein, we will review this interesting field and also highlight some recent new studies.

Inhibiting MDSCs expansion and recruitment

Anti-colony-stimulating factors

The development of MDSCs seems to be governed by the same growth factors modulating normal myelopoiesis.145,146 Recombinant human GM-CSF (rhGM-CSF) is used in the clinic to promote myeloid reconstitution following bone marrow transplantation or induction chemotherapy in AML patients. However, GM-CSF has also been found to stimulate the accumulation of MDSCs and impair the anticancer immune responses.147 In a clinical study, rhGM-CSF administration was proved to increase the MDSCs levels in the peripheral blood of patients with recurrent prostate cancer.148 Also, in a large randomized trial of advanced HNSCC patients treated with chemoradiotherapy, adjuvant G-CSF treatment was identified as a factor associated with poor prognosis due to decreased locoregional disease control.149 Moreover, G-CSF is a positive regulator of Bv8 (Bombina variegata 8) which not only mobilizes MDSCs from the bone marrow but also promotes angiogenesis in tumor.150 A lot of preclinical studies have reported that the blockade of GM-CSF/G-CSF signaling restricted the accumulation of MDSCs and restored antitumor immune response.151,152 In addition, myeloid cells in tumor sites always undergo the differentiation from monocytes/M-MDSCs towards TAMs, and this conversion is primarily mediated by CSF-1 and HIF-1α.153 CSF-1R blockade is an excellent approach to restrain the polarization towards M2 type macrophages in the TME.154 Previous studies have emphasized that improved effects were observed when CSF-1/CSF-1R blockade was combined with irradiation, paclitaxel, anti-VEGFR antibody, and immune checkpoint inhibitors in preclinical tumor models.155,156 In conclusion, CSFs blockade-based combination therapies require further verification as promising strategies to inhibit MDSCs expansion in cancer patients.

Anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapy

VEGF is an indispensable stimulator in MDSCs mobilization and expansion, and MDSCs in turn promote tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by secreting VEGF.157 VEGFR1 expressed on MDSCs is also accountable for their recruitment into tumor environment. In ovarian cancer patients, high VEGF expression in peritoneal dissemination was correlated with high MDSCs infiltration as well as an unfavorable prognosis.158 Thus, targeting the VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathway can reduce the recruitment of MDSCs and impede their angiogenesis-promoting effects.

The effects of widely applicated anti-VEGF/VEGFR therapies on MDSCs have been demonstrated in cancer patients. For instance, bevacizumab-based therapy significantly reduced the proportion of PMN-MDSCs in the peripheral blood of NSCLC patients.159 In a phase 0/I dose-escalation clinical trial (NCT02669173), low-dose, metronomic capecitabine combined with bevacizumab treatment significantly reduced circulating MDSCs levels in recurrent GBM patients and increased cytotoxic immune cells infiltration into the TME.160 Another study on patients with colorectal cancer reported that first line combination regimen of 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab (FOLFOX-bevacizumab) elicited a decrease of PMN-MDSCs in 15 of 25 patients, which was associated with a better survival outcome.161 However, in another study, bevacizumab treatment alone did not decrease the accumulation of MDSCs in the peripheral blood of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients.96 These discrepancies may be resulted from different choices in dosage, timing, or interval of drug administration. In fact, in preclinical studies, anti-VEGF/VEGFR agents could delete MDSCs in tumor, spleen, and in circulation in a dose-dependent manner.162

Anti-S100A8/A9

S100A8 (calgranulin A or myeloid-related protein 8, MRP8) and S100A9 (calgranulin B or myeloid-related protein 14, MRP14) are small molecular calcium-binding proteins that play crucial roles in cancer development, and thus are considered as diagnostic markers and novel targets for cancer therapy.163,164 MDSCs express both S100A8/A9 and the corresponding receptors RAGE, working as a positive feedback loop to recruit MDSCs and enhance their immunosuppressive function.165 Inhibiting S100A8/A9 has been indicated to restrain tumor growth by reducing the accumulation of MDSCs in several mouse tumor models.166–168 Tasquinimod is an oral agent that can bind to S100A9 and in turn block the interaction between S100A9 and its sensors, including RAGE and TLR4.169 Many studies have established that tasquinimod treatment in cancer can lead to depletion of blood monocytes, reduction of MDSCs infiltration into tumor sites, and induction of TAMs to M1 polarization.170 In a phase II trial, tasquinimod treatment improved PFS in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) by reducing the recruitment of MDSCs and inhibiting metastasis.171,172 Recently, in a phase III clinical trial, tasquinimod treatment in mCRPC patients led to considerably longer radiologic PFS compared with the placebo group, but no influence on the OS was observed.173 Contradictorily, another phase II clinical trial (NCT01743469) aiming to examine the effectiveness of tasquinimod in patients with advanced hepatocellular, gastric, ovarian, and renal cell carcinomas revealed no efficiency of tasquinimod on any of these tumor types.174 Together, these findings propose S100A8/A9 as advisable targets to ameliorate MDSCs-mediated immunosuppression in cancer. However, further exploration on the efficacy of S100A8/A9-targeting strategies is wanted.

Anti-IL-1β

IL-1β contributes to tumor initiation and progression mainly by inducing chronic non-resolved inflammation, promoting angiogenesis, as well as driving MDSCs expansion and migration.175 In the peripheral blood of advanced melanoma patients, an elevated frequency of IL-1β was positively correlated with the level of M-MDSCs.176 And it was reported that M-MDSCs in the premetastatic lungs of tumor-bearing mice could produce IL-1β to increase E-selectin expression, which in turn promoted the arrest of tumor cells on endothelial cells.177 On the other hand, the NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome is one of the most well recognized inflammasomes that promotes IL-1β maturation and secretion.178 In a study from both HNSCC patients and mouse models, the level of IL-1β was increased in the peripheral blood, while the NLRP3 inflammasome was overexpressed in the tumor tissues. Currently, several agents are available to inhibit IL-1, which include IL-1Ra (anakinra), IL-1β specific antibodies (canakinumab), as well as inflammasome inhibitors.179–181 Notably, multiple cancer therapeutic agents such as chemotherapeutic drugs, MAPK inhibitors, and BRAF V600E inhibitor (BRAFi) have been reported to either increase the expression of IL-1β or activate inflammasomes in myeloid cells,182,183 causing unwanted side effects. In this regard, IL-1β blockade may generate adjunctive effects when combined with chemotherapies or other treatments in cancer.184

Anti-CCL2/CCR2

The CCL2/CCR2 pathway contributes significantly to the migration of M-MDSCs to tumor sites. Moreover, overexpressed CCL2 has been found in many cancers, which is always associated with disease progression.50,185,186 In preclinical mouse tumor models, the combinations of CCL2/CCR2 blockade with radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy have shown synergistic and improved antitumoral effects, along with decreased tumor-associated MDSCs as well as increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.187–189 In a phase I dose-escalation study, patients with primary breast cancer were administered safely with CCL2 inhibitor propagermanium (PG), which was expected to exert anti-metastatic potential.190 However, a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) against CCL2 CNTO888 showed no antitumor activity as a single agent in mCRPC patients.191 The limited therapeutic efficacy of CNTO888 may be ascribed to transient neutralization of free-CCL2, followed by significant accumulation of total CCL2 in the circulation.191 Additionally, CCR2-targeting strategies also show efficacy in cancer management. Results from a phase Ib trial revealed that, PF-04136309 (a small molecule inhibitor of CCR2) in combination with the chemotherapy regimen FOLFIRINOX treatments in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma inhibited the migration of inflammatory monocytes from the bone marrow, leading to decreased TAMs and higher tumor control rates.192 Moreover, pancreatic cancer patients treated with CCR2 inhibitor CCX872 coupled with FOLFIRINOX had longer overall survival compared with those in FOLFIRINOX monotherapy group.193 Currently, another CCR2 inhibitor BMS-813160 is being tested in clinical trials combined with immunotherapy or chemotherapy for the treatment of solid tumors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of clinical trials targeting MDSCs in cancer.

| Target | Drug name | Indications | Phase | Last reported status | NCT number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibiting expansion and recruitment | G-CSF | G-CSF, Cabazitaxel | Prostate cancer | III | Recruiting | NCT02961257 |

| VEGF | Bevacizumab, Capecitabine | Glioblastoma | I | Recruiting | NCT02669173 | |

| VEGF/ VEGFR | Bevacizumab, Pazopanib | Renal cell carcinoma/cancer | I/II | Recruiting | NCT01684397 | |

| VEGF | Bevacizumab, Anakinra, LV5FU2 | Colorectal cancer | II | Completed | NCT02090101 | |

| VEGFR | Pazopanib | Prostate adenocarcinoma | II | Completed | NCT01832259 | |

| VEGFR | Cabozantinib | Prostate cancer | II | Recruiting | NCT03964337 | |

| EGFR | Cetuximab, Edodekin alfa | Head and neck carcinoma | I/II | Active, not recruiting | NCT01468896 | |

| EGFR | Cetuximab, Cyclophosphamide | Head and neck cancer | II | Completed | NCT01581970 | |

| S100A9 | Tasquinimod | Advanced cancer | II | Completed | NCT01743469 | |

| CXCR1/2 | Reparixin, Paclitaxel | Metastatic breast cancer | II | Completed | NCT02370238 | |

| CXCR1/2 | Reparixin, Paclitaxel | Metastatic breast cancer | I | Completed | NCT02001974 | |

| CCR2 | CCX872-B | Pancreatic cancer | I | Active, not recruiting | NCT02345408 | |

| CCR2 | MLN1202 | Cancer | II | Completed | NCT01015560 | |

| CCR2 | PF-04136309, Chemotherapy | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | I | Completed | NCT01413022 | |

| CXCR2 | AZD5069, Enzalutamide | Prostate cancer | I/II | Recruiting | NCT03177187 | |

| CCR5 | Leronlimab + Carboplatin | Triple negative breast neoplasms | I/II | Recruiting | NCT03838367 | |

| IL-8 | HuMax-IL8 | Solid tumor | I | Completed | NCT02536469 | |

| PI3K | Duvelisib, Ibrutinib | Lymphocytic leukemia | II | Recruiting | NCT04209621 | |

| PI3K | Idelalisib | Hodgkin lymphoma | II | Completed | NCT01393106 | |

| Promoting differentiation | STAT3 | AZD9150 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | I | Completed | NCT01839604 |

| STAT3 | IONIS-STAT3Rx | DLBCL lymphoma | I/II | Completed | NCT01563302 | |

| TLR7 | Imiquimod, Abraxane | Breast cancer | II | Completed | NCT00821964 | |

| Curcumin | Breast cancer | I | Recruiting | NCT03980509 | ||

| Curcumin | Prostate cancer | III | Recruiting | NCT03769766 | ||

| Curcumin | Breast cancer | II | Completed | NCT03072992 | ||

| β-glucan | Oral cavity carcinoma | Not applicable | Active, not recruiting | NCT04387682 | ||

| β-glucan | NSCLC | Not applicable | Recruiting | NCT00682032 | ||

| Inhibiting function | PDE5 | Tadalafil | Head and neck cancer | Not applicable | Completed | NCT00843635 |

| PDE5 | Tadalafil | Head and neck carcinoma | II | Completed | NCT00894413 | |

| PDE5 | Tadalafil | Head and neck carcinoma | II | Completed | NCT01697800 | |

| PDE5 | Sildenafil, Chemotherapy | NSCLC | II/III | Completed | NCT00752115 | |

| NRF2 | Omaveloxolone | NSCLC, Melanoma | I | Completed | NCT02029729 | |

| H2R | Ranitidine | Cancer | IV | Active, not recruiting | NCT03145012 | |

| Inhibiting metabolism | IDO | Indoximod, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel | Breast cancer | II | Completed | NCT01792050 |

| CD73/A2AR | MEDI9447, AZD4635 | Carcinoma, NSCLC | I/II | Active, not recruiting | NCT03381274 | |

| Depleting MDSCs | CD33 | GTB-3550 TriKE™ | Leukemia | I/II | Recruiting | NCT03214666 |

| Gemcitabine | Pancreatic cancer | II | Completed | NCT01019382 | ||

| Cyclophosphamide, Docetaxel, Doxorubicin, Oxidized glutathione | Breast cancer | II | Completed | NCT00499122 | ||

| TRAIL-R2 | DS-8273a | Solid tumor, Lymphoma | I | Completed | NCT02076451 | |

| Other therapies | Octreotide acetate | Neuroendocrine tumor | II | Active, not recruiting | NCT04129255 | |

| Qingshu-Yiqi-Tang | Carcinoma, NSCLC | II/III | Recruiting | NCT01802021 | ||

| Soy bread diet | Prostate adenocarcinoma | II | Recruiting | NCT03654638 |

One of the plausible reasons for the dissatisfactory results from current clinical trials is that neither CCL2 neutralizing antibodies nor CCR2 inhibitors can effectively block the CCL2-CCR2 axis for a long time.191,194 In addition, the infiltration of MDSCs into tumor sites is controlled by various alternative factors such as the ligands of CCR5, hence therapeutic blockade with a single particular chemokine inhibitor has limited effects.53 Although targeting chemokine receptors is more efficient because one receptor may interact with several chemokines, we should pay attention that many of the CC chemokines can simultaneously induce the recruitment of APCs and TILs into tumor tissues.195 Nevertheless, targeting the CC chemokine/receptor axis exhibits great potential for cancer therapy, particularly in combination with immunotherapies.

Anti-CXCLs/CXCR1/2

In tumor-bearing hosts, the activated CXCLs/CXCR1/2 axis plays an important role in supporting immune evasion and tumor progression partially through promoting neutrophils and PMN-MDSCs recruitment.196 Further, traditional anticancer treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been found to induce inflammatory CXCLs release, which in turn lead to therapy resistance. The combination of chemotherapies with the CXCLs/CXCR1/2 axis blockade showed synergistic effects in enhancing antitumor activity in preclinical tumor models.197,198 Anti-CXCLs/CXCR1/2 therapies have also been reported to improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), adoptive transferred engineered T cells and NK cells in various tumor models through abrogation of PMN-MDSCs trafficking into tumor sites.51,199,200 To date, several CXCR1/2 inhibitors have been assessed in clinical trials for cancer treatment, such as Reparixin, Navarixin, AZD5069, and SX-682.201 In addition, ABX-IL8 and HuMax-IL8 are two well-investigated humanized mAbs targeting IL-8 (CXCL8 is also known as IL-8 in human).202 Importantly, HuMax-IL8 has been confirmed to be safe and tolerable in patients with locally advanced solid tumors, and now is under evaluation in a phase Ia/II study in combination with nivolumab (NCT03400332).203 In all, blockade of the CXCLs/CXCR1/2 axis exhibits limited direct antitumor effects, and therefore, combining the CXCLs/CXCR1/2 axis inhibition therapy with chemotherapy, anti-angiogenesis therapy, and immunotherapy in cancer treatment is practicable. Additionally, the level of serum IL-8 can be used as a valuable diagnostic biomarker to select patients in whom these combinations should be evaluated.204

Promoting MDSCs differentiation into mature myeloid cells

STAT3 inhibitors

Constitutive phosphorylation of STAT3 is a pivotal molecular event that regulates the expansion and immunosuppressive function of MDSCs in cancer,205 besides, STAT3 also prevents the differentiation of IMCs into mature DCs and macrophages.206 Thus, STAT3 can serve as an attractive therapeutic target to reduce MDSCs for cancer management.207 Oral treatment with cucurbitacin B (a selective inhibitor of JAK2/STAT3) daily for seven consecutive days was found to decrease IMCs and simultaneously increase the levels of mature myeloid cells in the peripheral blood of patients with advanced lung cancer.208 Furthermore, a phase Ib trial (NCT01563302) revealed that systemic administration of AZD9150, an antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of STAT3, reduced the levels of peripheral PMN-MDSCs in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).209 More interestingly, accumulating studies have indicated the rationale and feasibility of STAT3 inhibition in combination with immunotherapy in cancer treatment. In mouse liver metastasis tumor models, STAT3 inhibitors markedly promoted Bax-dependent apoptosis of MDSCs and further enhanced the antitumor efficiency of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy.210 Currently, a phase II clinical trial testing AZD9150 coupled with anti-PD-L1 mAb (MEDI4736) and anti-CTLA-4 mAb (tremelimumab) in patients with advanced solid tumors and relapsed metastatic HNSCC is ongoing (NCT02499328). Therefore, targeting STAT3 signaling is along the encouraging direction of tumor immunotherapy.

All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA)

ATRA is a derivative of vitamin A with agonistic activity towards retinoid-activated transcriptional regulators (RARα and RARβ). These regulators consecutively activate downstream signals and subsequently induce the maturation of primitive myeloid cells into fully differentiated (less-immunosuppressive) variants.211 Acute promyelocytic leukemia is considered as one of the most well-defined targeted cancer types of ATRA. Recent studies on other cancer types have highlighted that ATRA can stimulate the differentiation of MDSCs into mature DCs, macrophages, and granulocytes.211,212 The ATRA-induced differentiation of MDSCs deals with increased glutathione synthase (GSS) and glutathione (GSH) production in MDSCs, which neutralize ROS and drive the myeloid-cell differentiation.213 In patients with mRCC, administration of ATRA with high plasma concentration (>150 ng/mL) abrogated MDSCs-mediated immunosuppression by promoting their differentiation into APC precursors, effectively improving T cells-induced cytotoxicity on tumor cells.29 ATRA has also been utilized to enhance the effects of conventional chemotherapeutic agents and immunotherapies in cancer.214 Data from a clinical trial in patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) elucidated that the combination of ATRA with vaccination (DCs transduced with wild-type p53) depleted MDSCs from peripheral blood substantially and enhanced the immune response to vaccination.215 Another trial (NCT02403778) found that the addition of ATRA to the standard ipilimumab therapy in patients with stage IV metastatic melanoma considerably reduced the number of circulating MDSCs compared with ipilimumab therapy alone.216 Although ATRA as a single agent is less effective in solid tumors, it might augment immune response and prolong the survival of patients by inducing the differentiation of MDSCs.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) agonists

TLRs are type I transmembrane proteins that can recognize both endogenous and exogenous damage-associated and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs and PAMPs), inducing innate immune responses. Many clinical trials have indicated that synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) containing unmethylated cytosine-phosphorothioate-guanine (CpG) motifs, agonists for TLR9, have antitumoral immune activity as therapeutic vaccine adjuvants.217 Recent papers have documented that the anticancer efficiency of CpG ODN acted partially by inducing the differentiation and maturation of MDSCs.218,219 IFN-α produced by plasmacytoid DCs upon CpG stimulation has been identified as a key effector to promote the maturation of PMN-MDSCs.220 Intriguingly, the CpG-STAT3siRNA conjugate (ODN coupled to STAT3 siRNA) strategy could trigger TLR9 immunostimulation and eliminate the negative effects of STAT3 concomitantly in myeloid cells.221 Studies have concluded that PMN-MDSCs expressing high levels of TLR9 and STAT3 accumulated in the circulation and tumor site of prostate cancer patients, and CpG-STAT3siRNA abrogated the immunosuppressive effects of these MDSCs effectively.222

TLR7/8 agonists also serve as monotherapy or synergize with immunotherapeutic approaches to enhance antitumor effects by inducing MDSCs to acquire non-suppressive capability.223,224 In a phase Ib trial (NCT02124850), fourteen patients with primarily diagnosed HNSCC were enrolled and treated with TLR8 agonist motolimod plus cetuximab preoperatively. The findings revealed that fewer MDSCs and increased M1 monocytes were found in tumor tissues.225 Folate-linked TLR7 agonists could also induce the abrogation of MDSCs/TAMs-mediated immunosuppression and enhance T cell infiltration, improving survivals of mouse tumor models.226

Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C, a synthetic double-stranded RNA ligand for TLR3) is utilized as an adjuvant to enhance antitumor immunity.227 Poly I:C also exhibits the potential to decrease the frequency of MDSCs and abrogate their immunosuppressive function.228 In a B16 tumor model, after poly I:C administration, MDSCs produced increased IFN-α through the activation of the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) pathway and sequentially motivated NK cells, leading to delayed tumor growth.229 Currently, poly I:C is mainly used in combination with other anticancer therapies in preclinical studies, including irradiation,230 cancer vaccine, and CAR-T therapy.231 Nevertheless, the effect of poly I:C in cancer patients requires further investigation.

Other potential therapies

Like ATRA, vitamin D3 can induce the differentiation of MDSCs and improve the antitumor immune responses.28,232 Treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3 in HNSCC patients before surgery reduced the frequency of immune inhibitory CD34+ progenitor cells while increased the maturation of DCs in tumor tissues.233 In another study, HNSCC patients administrated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 had increased intra-tumoral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and a lengthier tumor progression free time compared to untreated patients.234

Curcumin,235 icariin (ICA),236 and β-glucans237 have also been reported to promote the differentiation of MDSCs as well as reduce the associated immunosuppression in preclinical tumor models. For instance, curcumin treatment polarized MDSCs to an M1-like phenotype with increased CCR7 expression and decreased dectin 1 expression in vivo and in vitro.238,239 Additionally, treatment of NSCLC patients with particulate β-glucan for two weeks reduced the levels of PMN-MDSCs in the peripheral blood.240 Further research found that whole β-glucan particles (WGPs) could inhibit nuclear factor I-A (NFIA) expression in PMN-MDSCs.241 Based on this concept, intensive studies are wanted to identify the therapeutic potential of above-mentioned compounds, especially in cancer patients.242,243

Inhibiting MDSCs function

COX-2/PGE2/EP axis inhibitors

The abnormally activated COX-2/PGE2/EP pathway has recently emerged as an attractive therapy target in tumor-bearing hosts. This pathway was demonstrated to enhance MDSCs accumulation,244 maintain their suppressive function,245,246 and regulate the PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating MDSCs.247 Particularly, PGE2 has been proved to improve the production of CXCL12, causing the CXCL12-CXCR4-mediated attraction of MDSCs into the TME.244 In addition, tumor-derived PGE2 was reported to mediate the activation of nuclear p50/NF-κB in M-MDSCs, diverting their response to IFN-γ towards NO-mediated immunosuppression and reducing their TNFα production.248 On the other hand, there is a positive feedback loop between PGE2 and COX-2 in MDSCs. PGE2 derived from tumor or stroma cells induces high levels of COX-2 expression in MDSCs through prostaglandin E (EP) 2/EP4 receptors, and COX-2 consecutively initiates the autocrine production of endogenous PGE2 and stabilizes the suppressive functions of MDSCs.249 Recently, a novel signaling circuit has been demonstrated in colorectal cancer. The downregulation of RIPK3 (receptor-interacting protein kinase 3) in tumor-infiltrating MDSCs potentiated COX-2-mediated PGE2 production which further reduced RIPK3 and promoted the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs.250

Multiple preclinical studies have explored the effects of the COX-2/PGE2/EP axis blockade on the development of MDSCs in cancer.251,252 For example, dietary treatment of celecoxib decreased local and systemic accumulation of all MDSC subtypes and reduced the levels of ROS and NO in tumor-bearing mice.253 Moreover, combination treatment of anti-CD40 agonist and celecoxib decreased the ARG1 expression in MDSCs and increased the survival of GL261 glioma-bearing mice, compared with monotherapy alone.254 Current therapies targeting COX-2 using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors have severe adverse effects because of global prostanoid suppression, therefore, targeting the downstream molecules of the PGE2 pathway can also be a potential approach.255 Results from a phase I clinical trial (NCT02540291) in patients with advanced solid tumors showed that oral administration of E7046, an EP4 inhibitor, significantly enhanced tumor infiltration of CD3+ and CD8+ T cells, but the levels of MDSCs in these patients were not reported. Accumulating evidence has shown that EP4 antagonism should be investigated further as a promising strategy for cancer treatment, particularly in combination with chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or immune-based therapy.256,257

Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitors

PDE5 inhibitors (such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil) have been routinely applied for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, benign prostatic hyperplasia, cardiac hypertrophy, and pulmonary hypertension.258 These inhibitors were also reported to downregulate the expression of ARG1, iNOS, and IL-4Ra in MDSCs via increasing the intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) concentrations, thus making MDSCs less immunosuppressive.259,260 One possible molecular mechanism for these effects is that cGMP destabilizes iNOS mRNA by reducing the ubiquitous mRNA binding protein. Another possibility is that high levels of cGMP reduce the concentration of cytosolic Ca2+ and thus inhibit the activity of calcium-dependent protein kinase C, which consecutively prevents the upregulation of IL-4Rα and ARG1 in MDSCs.261

In an open-label, dose de-escalation trial, tadalafil treatment in metastatic melanoma patients was proved to be safe and well-tolerated, with clinically stable patients displaying significant infiltration of CD8+ T cells and reduction of MDSCs in metastasis lesions.262 Another study (NCT00843635) showed that, in HNSCC patients, tadalafil therapy considerably reduced the concentrations of both MDSCs and Tregs in the blood and tumor.263 The activity of tadalafil was maximized at an intermediate dose (10 mg/d) compared with a high dose (20 mg/d), indicating that high dosages might negatively affect antitumor immunity by increasing the production of intracellular cAMP. Similar findings were also reported in another clinical trial (NCT00894413), in which tadalafil treatment in HNSCC patients augmented systemic and tumor-specific immunity, reduced peripheral MDSCs numbers, and decreased ARG1 and iNOS in total MDSCs.264 However, even though PDE5 inhibitors can induce enhanced CTL responses, such treatment alone is unlikely to eliminate tumors completely, and on this basis, a combination with other therapies is a rational choice. For instance, a recent study showed that tadalafil combined with lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and clindamycin generated a durable clinical response in a patient with end-stage multiple myeloma, along with decreased expression levels of IL-4Ra, ARG1, and iNOS in bone marrow M-MDSCs.259 Moreover, a phase I trial (NCT01342224) testing tadalafil and a telomerase vaccine (GV1001) alongside gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma is ongoing.

Epigenetic regulators

Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) are important epigenetic regulators.265 Recent studies in preclinical mouse tumor models have shown that HDACis can significantly reduce ARG1, iNOS, and COX-2 expression in MDSCs, thus promoting the efficiency of immunotherapeutic agents.266,267 A study on EL4 lymphoma and LLC (Lewis lung carcinoma) mouse models reported that the selective class I HDACi entinostat reduced the immunosuppressive activity of PMN-MDSCs. Whereas, M-MDSCs expressed high levels of class II HDAC6, and inhibition of HDAC6 using ricolinostat decreased the immunosuppressive activity of M-MDSCs.268 Furthermore, adjuvant epigenetic therapies using entinostat and low-dose 5-azacytidine (DNA methyltransferase) disrupted the formation of premetastatic niche after surgery in pulmonary metastases mouse models. The underlying mechanism was that epigenetic therapies not only inhibited MDSCs trafficking by downregulating CCR2 and CXCR2 but also induced MDSCs differentiation towards a more-interstitial macrophage-like phenotype.269 A phase II clinical trial confirmed that the combination of entinostat and pembrolizumab provided a clinical meaningful benefit for patients with immune checkpoint inhibitor-resistant NSCLC.270 Another clinical trial testing the combination treatment of nivolumab, 5-azacytidine, and entinostat in NSCLC patients (NCT01928576) is ongoing. Nevertheless, HDACis were reported to have both stimulatory and detrimental effects on immune cells, depending on immune cell types, cell activation status, and the class of HDACis.265 Therefore, further studies are required to explore the mechanisms of rational combination of immunotherapy with HDACis to develop effective therapies for cancer patients.

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway activator

Nrf2 is a ubiquitous master transcription factor which modulates several genes to attenuate oxidative stress. Nrf2 also contributes to the clearance of ROS in MDSCs and enables MDSCs to survive in the noxious TME.271 Systemic Nrf2-deletion or myeloid lineage Nrf2-deficiency in tumor-bearing mice could cause aberrant ROS accumulation in MDSCs, leading to increased susceptibility to cancer metastasis.272,273 The synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-Me (bardoxolone methyl, RTA402) is used for the treatment of chronic kidney disease, cancer, and other diseases.274 Recent studies have found that CDDO-Me could inhibit the immunosuppressive capacity of MDSCs by activating Nrf2 and inhibiting ROS generation in MDSCs. Nagaraj et al. reported that CDDO-Me treatment in tumor-bearing mice inhibited the suppressive activity of splenic MDSCs, resulting in decreased tumor growth.275 In addition, they performed a phase I clinical trial (NCT00529113) in which pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients were intravenously administered with gemcitabine on days 1, 8, and 15 weekly and CDDO-Me orally once daily for 21 days. Analysis showed that CDDO-Me had no effect on MDSCs levels in the peripheral blood, but it significantly improved the immune response in these patients.275 However, it is not clear whether the level of Nrf2 in MDSCs from peripheral lymphoid organs or tumor tissues is different.276 In addition to its anti-oxidative activity, Nrf2 may also contribute to a context-dependent regulation of MDSCs.277 In general, Nrf2 is a potential target in cancer treatment which deserves further investigation.

Other potential therapies

Nitroaspirin or NO-releasing aspirin, a compound covalently linking a NO-releasing moiety and a classic aspirin molecule,278 was reported to inhibit ARG1 and iNOS production in MDSCs. When co-administered with a DNA vaccine, nitroaspirin (NCX 4016) inhibited the function of MDSCs and improved the survival of CT26 colon carcinoma mouse model.279 Mechanistically, analysis showed that the NO release contributed to iNOS inhibition, whereas the aspirin spacer portion caused the ARG-dependent inhibitory effect.279

NOV-002 (oxidized glutathione), a glutathione disulfide mimetic with the ability to induce S-glutathionylation, has been examined effective in patients with platinum-refractory ovarian cancer and advanced NSCLC.280,281 A preclinical study in mouse tumor model demonstrated that NOV-002 ameliorated cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced hematopoietic and immune suppression partially through inhibiting ROS production in MDSCs.282 In a phase II clinical trial (NCT00499122), breast cancer patients were treated with a combination of NOV-002 and preoperative chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and docetaxel). Analysis showed that patients with higher pathologic complete response (pCR) rates had lower levels of MDSCs in blood.283

Inhibiting MDSCs metabolism

Targeting fatty acid metabolism

MDSCs are characterized by high uptake of free fatty acids (FFAs) and increased expression of key fatty acid oxidation (FAO) enzymes (Fig. 5).284,285 Selectively targeting fatty acid metabolism of MDSCs can impede the associated immune suppression. Etomoxir, a specific inhibitor of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1, the first rate-limiting enzyme in FAO pathway), significantly delayed tumor growth in several mouse tumor models in a T-cell-dependent manner. Furthermore, the combination of etomoxir with low-dose chemotherapy completely abrogated the immunosuppressive function of tumor-infiltrating MDSCs.141 Besides, a previous study reported that GM-CSF signaling induced the overexpression of fatty acid transport protein 2 (FATP2) in PMN-MDSCs through activation of STAT5, and FATP2 in turn modulated the immunosuppressive function of PMN-MDSCs through uptake of arachidonic acid and synthesis of PGE2. The selective FATP2 inhibitor lipofermata, alone or in combination with checkpoint inhibitors, inhibited the activity of PMN-MDSCs and substantially delayed tumor progression in mice models.286

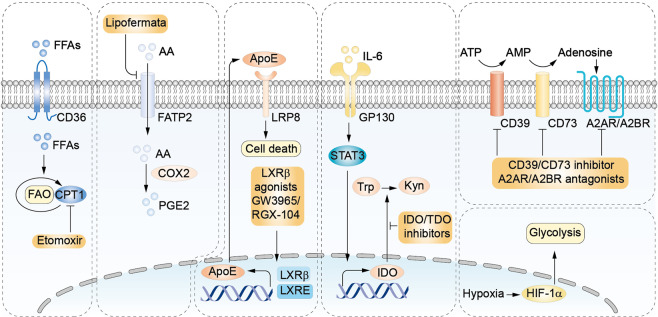

Fig. 5.

Targeting MDSCs by interrupting their metabolism. MDSCs are characterized by high free fatty acids (FFAs) uptake and fatty acid oxidation (FAO). Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), the first rate-limiting enzyme in the FAO cycle, can be inhibited by etomoxir. FATP2 mediates the uptake of arachidonic acid (AA) which subsequently promotes the synthesis of PGE2 in MDSCs. Lipofermata selectively inhibits FATP2. LXR agonists promote the transcriptional upregulation of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) which subsequently reduces MDSCs survival by binding to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8) on MDSCs. IDO and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) catalyze the first rate-limiting step in the conversion of L-tryptophan to L-kynurenine. IL-6 upregulates the transcription of IDO promoter in MDSCs through STAT-3 activation. IDO/TDO inhibitors attenuate the suppressive capability of MDSCs. Adenosine-generating axis and its receptor A2AR/A2BR are also metabolic targets to inhibit MDSCs. MDSCs exhibit upregulated glycolysis which is regulated by HIF-1α. CD36, fatty acid translocase; FATP2, fatty acid transport protein 2; LXR, Liver-X receptors; Trp, tryptophan; Kyn, kynurenine.

Transcription factors liver-X receptors (LXRβ and LXRα) are additional lipid metabolism-related targets in MDSCs. LXRs belong to the nuclear hormone receptor family and are involved in the transcriptional activation of genes associated with cholesterol, fatty acid, and glucose metabolism. LXR agonists have the potential to inhibit tumor proliferation and survival, as well as to elicit significant antitumor immunity effects.287 A recent study reported that the LXRβ agonists, GW3965 and RGX-104, reduced the MDSCs levels in several mouse tumor models.288 Mechanistically, LXR agonism upregulated the transcriptional target apolipoprotein E (ApoE), which bound to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8) on MDSCs to reduce MDSCs survival. Moreover, the combination of RGX-104 and various immune-based therapies (such as CAR-T and anti-PD-1 therapies) elicited robust antitumor immunity responses in mouse tumor models.289 A multicenter dose-escalation phase I trial of RGX-104, alone or in combination with chemotherapy/immune checkpoint inhibitor in patients with lymphomas or metastatic solid tumors, is ongoing (NCT02922764). Primary data have shown that the combined therapies induced MDSCs depletion and CTLs activation in cancer patients.

Targeting glycolysis

MDSCs upregulate glycolysis enzymes and exhibit high glycolytic rate, which protect them from apoptosis and result in their accumulation in cancer patients.290 Moreover, it was shown that tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs had upregulated mTOR phosphorylation and higher glycolysis than splenic M-MDSCs in mouse tumor models.291 And mTOR inhibitor rapamycin decreased the glycolysis, the immunosuppressive activities, and the percentage of tumor-infiltrating M-MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice.292 In addition, the glycolytic pathway of MDSCs is modulated by HIF-1α which can be inhibited by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation. And AMPK activation also can inhibit immune-related NF-κB, JAK-STAT, CHOP, and C/EBP pathways which are involved in the expansion and activation of MDSCs.293 Studies reported that pharmacological activation of AMPK by metformin inhibited the aggregation and immunosuppressive ability of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice.294,295 Moreover, metformin therapy was reported to abrogate the inhibitory activity of MDSCs in ovarian cancer patients through downregulating the expression and the extracellular enzyme activities of CD39 and CD73 in MDSCs.296 However, another study in tumor-bearing mice reported that conditional deletion of Prkaa1 in myeloid cells or systemic inhibition of AMPKα both reduced the immunosuppression of MDSCs and delayed tumor growth.297 Therefore, more studies should be conducted to investigate the role of glycolysis in modulating the immunosuppressive effects of MDSCs, especially in the context of tumors.

Targeting tryptophan catabolism