Abstract

An ambulatory elder with SCI, AIS C, balance deficits, and right ankle-foot-orthosis participated. RobUST-intervention comprised six 90 min-sessions of postural tasks with pelvic assistance and trunk perturbations. We collected three baselines and two 1 week post-training assessments—after the first four sessions (PT1) and after the last two sessions (PT2). We measured Berg Balance Scale (BBS), four-stage balance test (4SBT)—including a 30 s-window with and without vision—standing workspace area, and reactive balance (measured as body weight%). Kinematics, center-of-pressure (COP), and electromyography (EMG) were analyzed to compute root-mean-square-COP (RMS-COP), the margin of stability (MoS), ankle range of motion, and integrated EMG (iEMG) normalized to baseline. The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (BRPE), and change in the Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) compared with baseline were collected to address training tolerance. A 2SD-bandwidth method was selected for data interpretation. The maximum BBS was achieved (1-point improvement). In the 4SBT, the participant completed 30 s (baseline = 20 s) with reduced balance variability during semi-tandem position without vision (RMS-COP baseline = 50.32 ± 2 SD = 19.64 mm; PT1 = 21.29 mm; PT2 = 19.34 mm). A trend toward increase was found in workspace area (baseline = 996 ± 359 cm2; PT1 = 1539 cm2; PT2 = 1138 cm2). The participant tolerated higher perturbation intensities (baseline mean = 25%body weight, PT2 mean = 44% body weight), and on average improved his MoS (3 cm), ankle range of motion (4°), and gluteus medius activity (iEMG = 10). RobuST-intervention was moderate-sort of hard (BRPE = 3–4). A substantial reduction in MAP (9%) and HR (30%) were observed. In conclusion, RobUST-intervention might be effective in ambulatory SCI.

Subject terms: Rehabilitation, Medical research

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a multi-systemic condition accompanied by muscle tone dysregulation and paralysis that secondarily limits mobility, self-care, and participation [1, 2]. SCI frequently results from trauma and is an unexpected life-changing event that requires costly, complex, and long-term rehabilitation procedures [3–5]. A small percentage of people with SCI are community-dwelling ambulators [6]. Yet, these individuals live with impaired spinal-mediated proprioceptive deficits and corticospinal drive; which are the foundation for postural, limb, and walking control [7–11]. As a result, ambulatory people with SCI are prone to falls and cannot safely perform activities of daily living (ADLs) [6, 12–14]. Still, effective balance interventions are limited in SCI [15].

Posture, static and dynamic, can be subdivided into several dimensions. Steady-state postural control is the ability to cope with the body’s center of mass relative to the base of support (BOS). Active postural control is defined as the ability to elicit continuous compensatory postural adjustments during an action. Proactive posture accounts for anticipatory strategies to minimize the loss of balance before an action. And reactive postural control is the ability to execute rapid corrective muscle strategies during unforthcoming perturbations [14, 16]. In this study, we propose a novel robot-mediated intervention to train the multidimensionality of postural standing control in ambulatory people with SCI [14, 17].

The Robotic-Upright-Stand-Trainer (RobUST) controls simultaneously the trunk and pelvis via “perturbative” and “assist-as-needed” forces in combination with validated kinematic-related instrumentation in SCI [18–20]. We have implemented an activity-based intervention with RobUST (RobUST-intervention) that involves intense training, motor variability, repetitive trial-and-error practice, attention-to-task, and postural-task progression [21, 22]. The goal is to promote self-modulated and task-dependent postural adjustments in standing that are critical to each postural control dimension during actions such as reaching for a ball, hitting a punching bag, or pointing at a touchscreen device. Activity-based interventions are a promising neuro-rehabilitation approach because they promote neuroplastic changes (i.e., expanded motor cortex and re-modeling of corticospinal tracts) and long-term motor and functional outcomes such as reaching control, hand dexterity, posture, and gait; as has been shown in other neuromotor disorders [23–26]. In the present proof-of-principle study, we investigate the tolerance and feasibility of RobUST-intervention to enhance postural standing control in an ambulatory participant with SCI.

Material and methods

Clinical and anthropometric features of the participant

Table 1 summarizes the participant’s demographic and clinical information. Medical records were used to characterize the SCI following the Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) [27]. The American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) was used to define the severity of the SCI as motor complete (AIS A-B) or incomplete (AIS C-D) [27]. The Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM-III) was used to score the level of functional independence during daily tasks, in which a score of 100 indicates maximum independence [28]. Walking ability was classified with the Walking Index for Spinal Cord Injury-II (WISCI-II), which classifies the person’s ability to walk 10 m on a scale from 0 (no ability to stand or walk) to 20 (independent walking without devices, braces, or physical assistance) [29]. The participant was diagnosed with right foot drop. He could stand without his ankle-foot-orthosis (AFO) but with balance deficits. Hence, the AFO was removed to target active control of the ankle during RobUST-intervention. Functional balance was evaluated with Berg Balance Scale (BBS) [30]. The Four-Stage Balance Test (4SBT) was applied to examine steady-state balance with different foot placements [31]. Similar to the Clinical Test for Sensory Interaction on Balance, we used a 30s-interval with eyes open or closed during the 4SBT to discriminate proprioceptive-mediated postural deficits [32]. We measured the participant’s workspace area in standing with a RobUST-customized test (see “Experimental Setup and Procedures”). The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (BRPE), heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), and Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) were used as indicators of physical and cardiovascular tolerance [33, 34].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participant.

| Age (yrs) | Gender (M, F) | Height (cm) | Weight (Kg) | ASIA Sensory R/L | ASIA Motor R/L | NLI | SCI Time (years) | AIS (A-D) | SCIM-III (score) | WISCI-II (score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 | M | 186 | 93 | S4–5/S4–5 | L3/S1 | L3 | 12 yrs | C | 100 | 18 |

Yrs years, M male, F female, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association, NLI neurological level of injury, SCI spinal cord injury. AIS ASIA impairment scale, SCIM-III Spinal Cord Independent Measure III.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) traumatic SCI, (2) chronic SCI injury (>1 yr), and (3) WISCI-II ≥ 6. Exclusion criteria included: (1) surgeries 6mos before participation, (2) any medical condition that contraindicates intense physical exertion (e.g., pulmonary, liver, or renal disease), and (4) uncontrolled neurologic or musculoskeletal pain by medication.

Study design

Approval for this study was obtained by the IRB for Human Research at Columbia University (Protocol# AAAR6780). The participant was informed about the study requirements and then consented.

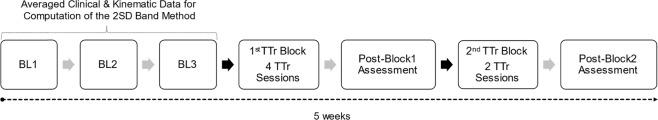

Figure 1 outlines our multiphase single-subject-research-design study. The study had a total of 11 sessions and was completed in 5 weeks. In the first week, we collected three baseline assessments scheduled one day apart. We used a 2 SD bandwidth method to interpret postural outcomes as substantial improvements, detriments, or unchanged with respect to baseline. The participant only underwent RobUST-intervention during the study to avoid potential interferences from other therapies [35].

Fig. 1. The study timeline.

We collected three baselines spread across 1 week to establish measurement stability of clinical and kinematic measurements. RobUST-intervention was subdivided into two training blocks with a total of six 90 min-training sessions. The 1st block comprised four training sessions and the 2nd block consisted of two additional training sessions. We collected two post-training evaluations after the end of each training block to evaluate short-term postural control improvements. The activity-based training targeted steady-state and proactive-active postural control in three training sessions, and reactive postural control in the other three training sessions. The training schedule followed was steady-state/proactive-active and then reactive. BL1, 2, or 3 baseline 1, 2, or 3, 1stTTr Block 1st training block, TTr Training, Post-Block 1 Assessment 1 week after 1st training block, 2ndTTr Block, 2nd training block, post-block 2 assessment 1 week after 2nd training block, 2SD 2 standard deviations.

We hypothesized that RobUST-intervention could improve steady-state, proactive-active, and reactive postural control. Also, a substantial increase or severe fluctuations in HR or BP were interpreted as inability to tolerate RobuST-Intervention.

Experimental setup and procedures

Experimental protocol

The participant stood unsupported and without AFO on two force plates (Bertec, Columbus, Ohio). We attached a harness to the participant’s pelvis to avoid falls and floor collisions. However, this harness was loosened and did not provide weight support. The participant was instructed to stand upright, look at a fixed point on the wall, and keep the feet at a shoulder-width distance (27.0 cm). This BOS was outlined with tape for consistent placement across sessions.

Kinematics were recorded with nine infrared video cameras (Vicon Vero 2.2, Denver). The body was modeled as a four linked-system (Fig. 3) [22, 36]. We recorded surface electromyography (EMG) (Delsys Trigno Wireless System, MA). We placed the electrodes bilaterally on tibialis anterior (TA), lateral gastrocnemius (LG), rectus femoris (RF), biceps femoris (BF), gluteus medius (GM), rectus abdominis (RA)—1 cm above and lateral to the umbilicus—and paravertebral lumbar muscles—latissimus dorsi, iliocostalis, longissimus, spinalis, and quadratum lumborum [37]. A medical vital sign monitor (Welch Allyn 300 Series, United States) was used to monitor the participant´s systemic cardiovascular responses: HR and BP.

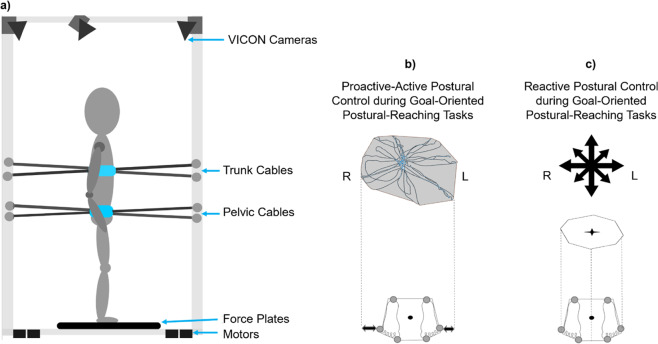

Fig. 3. Diagram displaying the Robotic-Upright-Stand-Trainer (RobUST) and postural training modalities.

a The motorized cables act simultaneously on the trunk and pelvis to deliver postural assistive or perturbative force fields. For this purpose, RobUST integrates measurements from VICON cameras (body kinematics) and two force plates (COP data represented as a black dot between the feet). We modeled the thorax, pelvis, legs, and feet to compute their geometrical center based on marker position. The markers were placed on acromion, xiphoid process, lateral rib cage (7th–9th ribs) and T1–T3, pelvic belt (anterior and posterior superior iliac spines), and rear, lateral and front sides of the feet (calcaneus, styloid process of the 5th metatarsal, and distal phalanx of the 1st metatarsal, respectively). b In the proactive-active postural control training, the goal was to expand the standing workspace area with respect to the base of support during “in-place” postural strategies (dotted lines and horizontal arrows), whereas the participant performs goal-oriented postural-reaching tasks. The assistive-force field was active at the balance control boundaries to prevent “change-in-support” postural strategies (i.e., stepping or reaching for support). These boundaries were adjusted across training sessions to offer postural-task progression. c In the reactive postural control training, the participant performed reaching tasks while receiving direction-specific perturbative forces on the trunk (black compass). The perturbation intensity was tailored and progressed to the force tolerance of the participant. During the training, the assistive-force field matched the BOS boundaries (dotted lines).

RobUST configuration to examine postural standing control

The engineering details of RobUST have been validated in previous studies [36, 38]. RobUST uses two motorized cable-driven belts to deliver force fields. These force field forces were tailored to either the participant’s area of standing control to train proactive-active balance or to the BOS limits to training reactive balance.

In proactive-active balance, we placed the trunk belt below the inferior angle of the scapulae (T9–12) to measure workspace area based on the postural star-standing test. This RobUST-customized test is based on the Star Excursion Balance Test for lower extremity injuries [39], SCI-related balance tests [40, 41], and our previously published postural-star sitting test in cerebral palsy [22]. The participant is instructed to maintain feet stationary while performing maximal trunk excursions along eight 45°star-radiated trajectories and return to a standing position. A maximum workspace of three attempts is used. The examiner places a ball close to the participant’s forehead and displaces it along the examined trajectory to guide the participant during the trunk movements.

RobuST delivered perturbative forces through the trunk belt. We implemented a progressive 4%incremental protocol based on the participant´s body weight (%Body weight). We determined the maximum intensity that the subject could tolerate against anterior, posterior, right, and left perturbations. Reactive balance control was subdivided into two events that were defined with respect to the force peak: perturbation (650 ms) and recovery (1500 ms). In the former, we evaluated the motor capability to resist perturbative forces; whilst in the latter, we examined in-place postural strategies to restore balance without stepping or reaching for support [14, 38].

Data reduction

MATLAB (R2017b, Mathworks, 2017), was used offline to filter and process data. Kinematics (100 Hz) were smoothed with a zero time-lag 4th order Butterworth filter at 4 Hz-cutoff. Rotations were computed as inter-segmental angles, following the right-hand convention and Euler sequence X-Y’-Z”: sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes, respectively.

We modeled the standing body as an inverted pendulum in which the center-of-pressure (COP) represents the final balance outcome of the neuromuscular system to maintain an upright stance, restore balance, and prevent falls [42]. Force plate data (1000 Hz) was used to compute the root-mean-square of the magnitude of COP position data (RMS-COP) during the 4SBT to measure the variability of steady-state balance control. We averaged the margin of stability (MoS), as measured by Sivakumaran et al. [43], to interpret balance control—i.e., control of the center of the pelvis (position and velocity) based on its distance relative to the BOS boundaries. We estimated the workspace area (cm2) with the in-built MATLAB function boundary(x,y, 0.05) based on maximal trunk excursion during the postural star-standing test [21, 22]. We also computed the RMS of the sum of angles across planes of motion of the ankles to measure the active range of motion (ROM).

EMG (1000 Hz) signals were band-pass filtered (60–500 Hz), rectified, low-pass filtered at 100 Hz, and normalized to the EMG baseline activity obtained when the participant received direction-specific perturbations: [44]

| 1 |

EMGnorm = Normalized EMG, in which a value >1 indicates muscle activation. ∫EMGreactive postural control = Integral EMG during either perturbation or recovery stage. ∫EMGbaseline = Integral EMG of background muscle activity during the same time interval of perturbation (620 ms) or recovery (1500 ms).

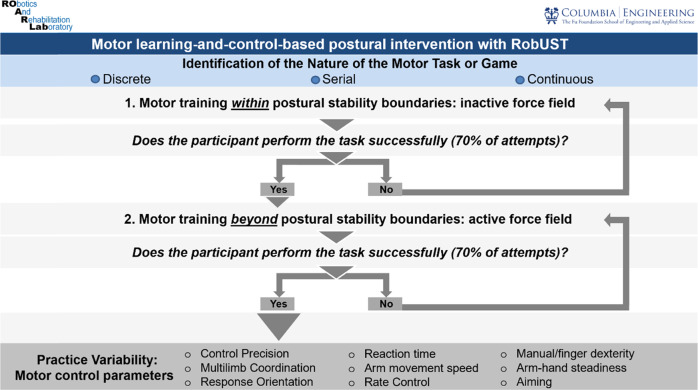

RobUST-intervention: general principles

The motor learning-control parameters applied in RobUST-intervention (Fig. 2) have been adapted from our previous robotic-mediated postural intervention, and other studies [21, 24, 25, 45]. The participant practiced (i) pointing tasks with buzzers, (ii) reaching for balls of different sizes and small checkers, (iii) bimanual catching and throwing, (iv) boxing, and (v) tablet games that involved pointing and attention-to-task such as crosswords, puzzles or hangman. In each one of the six 90 min-training sessions, a 10–15 min break was included. RobuST (Fig. 3) provides real-time visual feedback on the participant’s trunk and pelvic position relative to the stability boundaries so that the clinician can objectively target postural strategies within and beyond stability limits. The training follows the same star-shaped scheme applied in the postural-star-standing test. Within each proactive-active and reactive postural activity, a total of 20–30repetitions X direction, within and beyond postural stability limits (40–60 trials), were performed in the first two sessions. However, in the remaining sessions, we increased the training intensity—longer time and a greater number of repetitions—in the more-impaired directions: right-anterior, right, and right-posterior.

Fig. 2. The RobUST-intervention algorithm.

The task nature could be discrete, characterized by a defined start and end; continuous, motor task that stops arbitrarily; and serial: composition of discrete tasks. Practice variability was added when the participant was trained beyond postural stability boundaries to maximize the postural control training. The included parameters were: control precision, ability to perform rapid and precise movements to control devices/equipment (i.e., games or tablet); multilimb coordination, ability to move both upper limbs simultaneously; response orientation, ability to rapidly move to specific direction/s; reaction time, ability to respond as fast as possible to an external signal; arm movement speed, ability to perform rapid arm movements; rate control, ability to time anticipatory adjustments in response to speed and/or direction changes of a continuously moving target; manual dexterity, ability to perform skillful hand-arm movements with objects; finger dexterity, ability to perform skillful finger movements with small objects such as checkers; arm-hand steadiness, ability to maintain steady hand-arm and posture; and aiming, ability to move the hand/finger to a small target (static/moving). If verbal feedback was provided, terminal (augmented feedback delivered when the trial finalizes) and knowledge of results (augmented feedback that provides information about the movements outcome/s) were applied.

Steady-state and proactive-active postural control training

For training steady-state postural control, we administered through the trunk belt a constant force equivalent to 80% body weight to prevent compensatory upper body movements. Then, the participant practiced marching in-place and alternating steps on a 10 cm-height bench (3 sets × 20 repetitions).

In proactive-active postural control (Fig. 3a), we trained self-initiated and online corrections of postural strategies with an “assist-as-needed” pelvic force field equivalent to 15% body weight. The objective was to supplement voluntary movements beyond the participant´s stability limits without modifying the BOS. However, the force field remains inactive when the participant is within the workspace area (i.e., stability boundaries). Importantly, the force field boundaries were updated across training sessions—based on the postural-star-standing test—to address postural-task progression and prevent force-dependency during effortful muscle activity [22, 36].

Reactive postural control training

Reactive postural control training (Fig. 3c) combined both assistive-force fields at the pelvis and perturbative forces at the trunk. The perturbations were equivalent to the maximum intensity tolerated by the participant—defined by the 4% increment protocol. The participant received perturbations while first practicing activities within stability limits and then beyond stability limits. In the 2nd training block, the force perturbations were upgraded to the new tolerated intensities.

Results

Functional balance

The participant began the study with a high functional balance (BBS = 55/56). However, the participant improved 1-point in item 9 “retrieving object from floor” without the AFO after RobuST-intervention.

Steady-state postural control

In the 4SBT, the participant showed improvements in the semi-tandem position leading with the left foot without vision (Fig. 4). A reduction in postural variability (RMS-COP) was observed after RobuST-intervention (1st post-training block = 21.29 mm, and 2nd post-training block = 19.34 mm) compared with baseline (mean = 50 mm ± 2 SD = 20 mm). Also, the participant acquired the ability to sustain this semi-tandem configuration for 30 s (baseline = 20 s).

Fig. 4. Postural balance variability during semi-tandem position with and without vision in the 4SBT.

Note the substantial improvement in steady-state balance control (i.e., reduced RMS-COP) when the participant adopted a semi-tandem position, leading with the left foot and without vision. This improvement in steady balance control was observed after the 1st training block (PT1) and remained until the completion of RobUST-intervention (PT2). R right. L left. RMS-COP root-mean-square of the center of pressure. BL baseline. PT1 1 week after 1st training block. PT2 1 week after 2 training block.

Proactive-active postural control

The participant expanded his workspace area and increased the length of upper body excursions during the postural star-standing test. Nonetheless, these improvements did not meet the 2 SD bandwidth criteria (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Postural star-standing test outcomes.

The participant increased the workspace area (a) and performed greater larger upper body excursions (b) 1 week after the 1st and 2nd training blocks with respect to baseline. However, these improvements did not meet the 2 SD bandwidth criterion. BL baseline, PT1 1 week after the 1st training block. PT2 1 week after the 2nd training block, cm centimeters.

Reactive postural control

Tolerance to perturbative forces

The participant tolerated higher levels of force intensity after RobUST-intervention during posterior, anterior, and rightward perturbations (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The direction-specific perturbations delivered by RobUST to examine reactive postural control.

The subject was able to react against a higher reactive force intensity at the trunk after RobUST-intervention. However, this was not the case during leftwards perturbations since the participant achieved maximum intensity (50% of body weight) at baseline. BL baseline, PT1 1 week after 1 training block. PT2 1 week after 2nd training block.

Reactive postural control in stance

The participant showed greater balance control in standing (i.e., increased MoS). during anterior and right perturbations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Balance control per perturbation direction and across testing sessions.

| Perturbation direction | Baseline (cm ± 2 SD) | 1st post-training block (cm ± 2 SD) | 2nd post-training block (cm ± 2 SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior: 12% BW A–P axis | −1.4 (±3.4) | −0.8 (±1.6) | 1.2 (±2.1) |

| Anterior: 24% BW A–P axis | −3.2 (±3.8) | −1.7 (±1.7) | 2.4 (±6.1)a |

| Right: 40% BW lateral-axis | 0.1 (±0.1) | −0.1 (±0.1) | 0.8 (±2.0)a |

The percentage reflects the intensity of the perturbative force based on the participant’s total body weight. Note that during baseline and the 1st training block the participant was pushed close to the BOS boundaries, as indicated by a negative Margin of Stability value (MoS) or MoS close to 0. However, after the 2nd post-training block, the participant acquired more effective reactive in-place postural control strategies during anterior and rightwards perturbations. However, we should note that the improved reactive postural control adjustments were not consistent across all trials, as shown by a high SD. cm centimeter, 2 SD 2 standard deviation, %BW body weight, A–P anterior–posterior axis.

aSubstantial change.

EMG responses were highly variable across study sessions. We could not establish measurement stability during baseline assessments and we did not find substantial changes after each training block. However, we observed a consistent increase in right gluteus medius activity (iEMG) during perturbative forces towards the more-impaired lower extremity (i.e., right side) (Fig. 7 and Table 3).

Fig. 7. iEMG of gluteus medius activity during the reactive postural control exam.

A substantial increase in muscle activity was found during both the perturbation (650 ms) and recovery (1500 ms) events. mV millivolts, BL baseline, PT1 1 week after 1st training block. PT2 1 week after 2nd training block.

Table 3.

Normalized gluteus medius activity after each training block.

| Baseline normalized iEMG of gluteus medius during right perturbations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Perturbation: PT1 | Perturbation: PT2 | Recovery: PT1 | Recovery: PT2 |

| 0.93 | 1.10 | 10.70 | 8.90 |

A value >1 indicates greater iEMG activity than when the participant was receiving the perturbation at the same intensity and direction during baseline. iEMG integrated electromyography, PT1 1 week after 1st training block. PT2 1 week after 2nd training block.

Active ankle ROM

The active ROM of the right ankle improved substantially during the perturbation and recovery events across anterior, posterior, and rightwards perturbations (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Active ROM of the right ankle during the perturbation and recovery event in reactive postural control examination.

The participant increased the ankle ROM approximately by 5° (±2 SD = 0.2°) during anterior–posterior perturbations. Similarly, the ankle ROM increased about 3° (±2 SD = 0.3°) during rightwards perturbations. The dotted line at the upper 2 SD margin is used as a reference to interpret substantial ankle ROM improvements. BL baseline, PT1 1 week after 1st training block. PT2 1 week after 2nd training block.

Cardiovascular and physical exertion tolerance

The participant showed optimal cardiovascular tolerance to the intensity of RobUST-intervention. The participant’s physical exertion adapted from easy-moderate (BRPE = 2–3), in the first training session, to moderate-sort of hard (BRPE = 3–4), during the middle part of the training (training sessions 2–5), and again to easy-moderate at the end of RobUST-intervention (training session 6). The participant’s cardiovascular status did not show irregular BP or training-induced hypertensive responses. RobUST-intervention improved the cardiovascular response (Fig. 9). With respect to baseline, the participant experienced a reduction in MAP (1 week after 1st post-training block = 7% and 1 week after 2nd post-training block = 11%) and HR (1 week after 1st post-training block = 31% and 1 week after 2nd post-training block = 29%).

Fig. 9. Systemic cardiovascular condition of the participant prior to, during, and after RobUST-intervention.

Graph a shows BP (mmHG). Compared with baseline (mean systolic BP: 137 ± 3mmHG and mean diastolic BP: 97 ± 3 Hgmm), there was a substantial BP decrease (systolic/diastolic) during the 2nd training block, mainly on the diastolic response. Graph b shows MAP (mmHG). Similarly, we found a substantial decrease in MAP across training sessions and 1 week after the 1st and 2nd training blocks. Graph c displays HR. The cardiac response decreased substantially after the 1st training session compared with baseline (mean HR = 95 ± 2 bpm). Squares indicate before training. Circles represent after training. Solid black circles represent baseline ± 2 SD. BL baseline. c Syst systolic (red), Diast diastolic (blue), MAP mean arterial pressure, Pre before, Post posterior. Numbers 1–6 represent each training session. HR heart rate. Block 1 1 week after 1st training block. Block 2 1 week after 2nd training block.

Discussion

This single-subject-research study shows the preliminary efficacy of RobUST-intervention to train steady-state, proactive-active, and reactive postural standing control. The participant completed all the scheduled sessions, did not fall or report muscular or articular pain (visual analog scale ≤2/10), and showed cardiovascular tolerance to RobUST-intervention.

Research has shown that fear of falling during gait in people with SCI is associated with impaired postural standing sway [13]. As a potential solution, activity-based training can restore sensorimotor impairments and functions in SCI. Indeed, a study showed that gait-specific training accompanied by high cardiovascular intensity improves walking velocity and balance confidence [46]. However, this seems not to be the case with current balance interventions [47]. Hence, technological advances are opening new frontiers to design new postural training in SCI. For instance, Sayenko et al. [48] showed that for people with incomplete SCI, a variety of video games synchronized with force plate and visual feedback induces trial-and-error learning and improves balance control. Similarly, our pilot data show that activity-based postural training with RobUST technology is highly effective to train postural standing in ambulatory people with SCI.

The participant of our study was a safe community-dwelling ambulator since his BBS score at baseline (55/56) was superior to the average 47.9 found in ambulatory people with SCI and AIS D [49]. Still, he improved his dynamic balance to pick up objects from the floor after RobUST-intervention.

Research has shown that postural sway during upright stance and subtle perturbations are controlled via continuous sensory-mediated corrective torques [50]. In the 4SBT, the participant was able to stand for 30 s and demonstrated greater balance in a semi-tandem position while leading with the left foot. This position per se is characterized by a small BOS and high postural imbalance, where the participant bears his weight on the more-impaired right hemipelvis and lower extremity. The participant, however, developed effective postural strategies to overcome the BOS-induced balance challenges. Aside from the plausible improved muscle condition of the lower body, we assume that RobUST-intervention enhanced the fine control of proprioceptive-mediated joint torques since steady-state balance improved without vision. Thus, the participant relied on somatosensory, and to less degree, vestibular inputs to control upright stance [50, 51].

In previous research, we demonstrated the capability of trunk force fields to increase the sitting workspace of individuals with SCI and improve seated postural abilities in cerebral palsy [21, 22]. The therapeutic potential of robotic-aided trunk control is also supported by SCI animal models [52]. Our participant showed a trend to substantially improve his standing workspace area after RobUST-intervention. The participant was able to counteract larger perturbative forces and elicit more effective direction-specific in-place postural strategies. The participant was oblivious to the directionality of the forces and thus could not respond via anticipatory postural adjustments. Furthermore, the participant improved reactive postural control mechanisms by increasing the MoS and active ankle motion. These postural adjustments were accompanied by increased activity of right gluteus medius; which was impaired in our clinical case—neurological level of injury: L3—together with the muscles of the anterior, posterior, and lateral compartments of the leg. Gluteus medius is an important pelvic stabilizer, and during postural imbalance in the frontal plane, it had a critical contribution in accepting body weight support on the most-impaired right leg (perturbation stage) and restoring postural balance (recovery stage) during upright stance. We believe these improved in-place postural control strategies are clinically relevant because people with SCI often compensate with their arms to control the body during ADLs in standing [53]. In this line, we have also shown in healthy participants that “assist-as-needed” pelvic force fields improve postural sway during postural perturbations in unsupported standing at a similar level to holding a handlebar for body support [38].

Future line of research and limitations

Overall, our findings emphasize the therapeutic value of the dual application of trunk and pelvic force fields to train posture in people with SCI. However, large sample size is necessary to generalize these outcomes to the ambulatory SCI population. Also, the inclusion of participants with severe balance deficits could address the full therapeutic potential of RobUST-intervention.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the participant for his valuable collaboration. This research was funded by NYS research funding DOH01-C31290GG, Dr. Sunil K. Agrawal principal investigator; and SCIRB fellowship grant, Tatiana Luna.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors contributed equally: V. Santamaria, T. D. Luna.

Change history

12/20/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41394-021-00467-6

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41394-021-00454-x.

References

- 1.Fulk GD, Behrman AL, Schmitz TJ. Traumatic spinal cord injury. In: O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk GD (eds). Physical Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA, 2014, pp 889–964.

- 2.Carpenter C, Forwell SJ, Jongbloed LE, Backman CL. Community participation after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornhaber R, Mclean L, Betihavas V, Cleary M. Resilience and the rehabilitation of adult spinal cord injury survivors: a qualitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:23–33. doi: 10.1111/jan.13396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. World Health Organization. SCI. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/spinal-cord-injury (2013).

- 5.French DD, Campbell RR, Sabharwal S, Nelson AL, Palacios PA, Gavin-Dreschnack D. Health care costs for patients with chronic spinal cord injury in the veterans health administration. J. Spinal Cord. Med. 2007; 477–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Brotherton SS, Krause JS, Nietert PJ. Falls in individuals with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:37–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson K, Gordon J. Spinal Reflexes. In: Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T, Siegelbaum S, Hudspeth A (eds). Principles of neural science. (The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2013).

- 8.Takakusaki K. Functional neuroanatomy for posture and gait control. J Mov Disord. 2017;10:1–17. doi: 10.14802/jmd.16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumprou M, Amatachaya P, Sooknuan T, Thaweewannakij T, Mato L, Amatachaya S. Do ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury walk symmetrically? Spinal Cord. 2017;55:204–7. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saensook W, Mato L, Manimmanakorn N, Amatachaya P, Sooknuan T, Amatachaya S. Ability of sit-to-stand with hands reflects neurological and functional impairments in ambulatory individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:232–8. doi: 10.1038/s41393-017-0012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewko JP. Assessment of muscle electrical activity in spinal cord injury subjects during quiet standing. Paraplegia. 1996;34:158–63. doi: 10.1038/sc.1996.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phonthee S, Saengsuwan J, Amatachaya S. Falls in independent ambulatory patients with spinal cord injury: incidence, associated factors and levels of ability. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:365–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John LT, Cherian B, Babu A. Postural control and fear of falling in persons with low-level paraplegia. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:497–502. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.09.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott MH. Postural Control. In: Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice. Wolters Kluwer, 2017, pp 153–82.

- 15.Tse CM, Chisholm AE, Lam T, Eng JJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of task-specific rehabilitation interventions for improving independent sitting and standing function in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2018;41:254–66. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1350340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massion J. Jean Massion_Mov posture and equilibrium. Prog Neurobiol. 1992;38:35–56. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(92)90034-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurfinkel V, Cordo P. The Scientific Legacy of Nikolai Bernstein. In: Latash M (ed). Progress in Motor Control: Bernstein’s traditions in movement studies. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, 1998, pp 1–20.

- 18.Alm M, Gutierrez E, Hultling C, Saraste H. Clinical evaluation of seating in persons with complete thoracic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:563–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CL, Yeung KT, Bih LI, Wang CH, Chen MI, Chien JC. The relationship between sitting stability and functional performance in patients with paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1276–81. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santamaria V, Khan M, Luna T, Kang J, Dutkowsky J, Gordon A, et al. Promoting functional and independent sitting in children with cerebral palsy using the robotic trunk support trainer. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2020;28:2995–3004. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2020.3031580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santamaria V, Luna T, Khan M, Agrawal S. The robotic Trunk-Support-Trainer (TruST) to measure and increase postural workspace during sitting in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2020; 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Friel KM, Kuo H-C, Fuller J, Ferre CL, Brandão M, Carmel JB, et al. Skilled bimanual training drives motor cortex plasticity in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30:834–44. doi: 10.1177/1545968315625838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon AM, Hung Y-C, Brandao M, Ferre CL, Kuo H-C, Friel K, et al. Bimanual training and constraint-induced movement therapy in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:692–702. doi: 10.1177/1545968311402508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bleyenheuft Y, Ebner-Karestinos D, Surana B, Paradis J, Sidiropoulos A, Renders A, et al. Intensive upper- and lower-extremity training for children with bilateral cerebral palsy: a quasi-randomized trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:625–33. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleyenheuft Y, Dricot L, Ebner-Karestinos D, Paradis J, Saussez G, Renders A, et al. Motor skill training may restore impaired corticospinal tract fibers in children with cerebral palsy. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34:533–46. doi: 10.1177/1545968320918841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirshblum SC, Waring W, Biering-Sorensen F, Burns SP, Johansen M, Schmidt-Read M, et al. Reference for the 2011 revision of the international standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:547–54. doi: 10.1179/107902611X13186000420242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catz A, Itzkovich M, Tesio L, Biering-Sorensen F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, et al. A multicenter international study on the spinal cord independence measure, version III: Rasch psychometric validation. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:275–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ditunno PL, Ditunno JF. Walking index for spinal cord injury (WISCI II): scale revision. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:654–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wirz M, Müller R, Bastiaenen C. Falls in persons with spinal cord injury: validity and reliability of the berg balance scale. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:70–77. doi: 10.1177/1545968309341059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CDC. Four-Stage Balance Test. 2017; 1–2.

- 32.Shumway-Cook A, Horak F. Assessing the influence of sensory integration on balance. Suggestion from the field. Phys Ther. 1986;66:1548–9. doi: 10.1093/ptj/66.10.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borg G. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1982;14:377–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeMers D, Wachs D. Mean Arterial Pressure. StatPearls [Internet]: Treasure Island (FL), 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538226/.

- 35.Perdices M, Tate RL. Single-subject designs as a tool for evidence-based clinical practice: are they unrecognised and undervalued? Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2009;19:904–27. doi: 10.1080/09602010903040691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan M, Luna T, Santamaria V, Omofuma I, Martelli D, Rejc E, et al. Stand trainer with applied forces at the pelvis and trunk: response to perturbations and assist-as-needed support. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2019;27:1855–64. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2933381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spratt J. Thorax. In: Standring S (ed). Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier, 2016, pp 953–75.

- 38.Luna TD, Santamaria V, Omofuma I, Khan MI, Agrawal SK. Control mechanisms in standing while simultaneously receiving perturbations and active assistance from the robotic upright stand trainer (RobUST). IEEE Int Conf Biomed Robot Biomechatronics 2020; 396–402.

- 39.Gribble PA, Hertel J, Facsm À, Plisky P. Using the star excursion balance test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. J Athl Train. 2012;47:339–57. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.3.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao KL, Chan KM, Purves S, Tsang WWN. Reliability of dynamic sitting balance tests and their correlations with functional mobility for wheelchair users with chronic spinal cord injury. J Orthop. Transl. 2015;3:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quinzaños J, Villa AR, Flores AA, Pérez R. Proposal and validation of a clinical trunk control test in individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:449–54. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winter DA. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement. 4th edn. John Wiley & Son, 2009.

- 43.Sivakumaran S, Schinkel-Ivy A, Masani K, Mansfield A. Relationship between margin of stability and deviations in spatiotemporal gait features in healthy young adults. Hum Mov Sci. 2018;57:366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aruin AS, Latash ML. The role of motor action in anticipatory postural adjustments studied with self-induced and externally triggered perturbations. Exp Brain Res. 1995;106:291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00241125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boswell-Ruys CL, Harvey LA, Barker JJ, Ben M, Middleton JW, Lord SR. Training unsupported sitting in people with chronic spinal cord injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:138–43. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lotter JK, Henderson CE, Plawecki A, Holthus ME, Lucas EH, Ardestani MM, et al. Task-specific versus impairment-based training on locomotor performance in individuals with chronic spinal cord injury: a randomized crossover study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2020;34:627–39. doi: 10.1177/1545968320927384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tse CM, Chisholm AE, Lam T, Eng JJ. A systematic review of the effectiveness of task-specific rehabilitation interventions for improving independent sitting and standing function in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;41:254–66. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1350340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sayenko DG, Alekhina MI, Masani K, Vette AH, Obata H, Popovic MR, et al. Positive effect of balance training with visual feedback on standing balance abilities in people with incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:886–93. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lemay JF, Nadeau S. Standing balance assessment in ASIA D paraplegic and tetraplegic participants: concurrent validity of the Berg Balance Scale. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:245–50. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maurer C, Peterka RJ. A new interpretation of spontaneous sway measures based on a simple model of human postural control. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:189–200. doi: 10.1152/jn.00221.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horak FB, Henry SM, Shumway-Cook A, Hemy SM. Postural perturbations: new insights for treatment of balance disorders. Phys Ther. 1997;77:517–33. doi: 10.1093/ptj/77.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martin Moraud E, von Zitzewitz J, Miehlbradt J, Wurth S, Formento E, DiGiovanna J, et al. Closed-loop control of trunk posture improves locomotion through the regulation of leg proprioceptive feedback after spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18293-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moynahan M. Postural responses during standing in subjects with spinal-cord injury. Gait Posture. 1995;3:156–65. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.