Abstract

Background:

Limited access to health care has been associated with limited uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM). This descriptive analysis examined, in a near universal healthcare setting, differences between MSM reporting using versus not using PrEP in the past 12 months.

Method:

Data come from the 2017 Boston sample of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system, containing a venue-based and time-spaced sample of 530 MSM. The analysis used descriptive frequencies and tests of bivariate associations by PrEP use using Fisher’s Exact Test.

Results:

N=504 respondents had data necessary to determine if PrEP was indicated and 233 (43.9%) had an indication for PrEP. Of these 233 participants, 117 (50.2%) reported using PrEP in the past 12 months. Not being out, in terms of disclosing one’s sexual orientation to a healthcare provider, lack of health insurance, limited access to healthcare, and history of incarceration were all significantly associated with not using PrEP in the past 12 months. Race/ethnicity was not significantly associated with PrEP use in the past 12 months.

Conclusions:

In the setting of Massachusetts healthcare expansion and reform, and in a sample somewhat uncharacteristic of the population of individuals experiencing difficulties accessing PrEP, structural and demographic factors remain potent barriers to PrEP uptake. Targeted PrEP expansion efforts in Massachusetts may focus on identifying vulnerable subgroups of MSM (e.g., underinsured or criminal justice system-involved MSM) and delivering evidence-based interventions to reduce stigma and promote disclosure of same-sex behavior in healthcare settings.

Keywords: PRE-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS (PrEP), MSM, HIV, SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS, PREVENTION

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV, accounting for 69% of the estimated 38,000 new infections occurring annually in the United States in 2018 [1]. In light of this continued HIV disparity, scaling up evidence-based HIV prevention for MSM continues to be a critical area of study. While past HIV prevention efforts focused primarily on behavioral strategies to reduce transmission risk behaviors (e.g., condomless sex, needle sharing), the field has evolved to include biomedical approaches to prevention [2–6], often integrated with behavioral interventions to promote adherence [7]. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) entails the use of antiretroviral medication (i.e., emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and, more recently, emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) to inhibit the establishment of viral infection, reducing the likelihood of seroconversion by 99% or greater among adherent individuals [4].

Despite the efficacy of PrEP in HIV prevention, PrEP uptake remains low among MSM [8,9]. PrEP uptake depends on identifying those at greatest risk for HIV, facilitating PrEP access, linking to PrEP care, receiving a prescription for PrEP, and initiating PrEP [10,11]. In the earlier days of PrEP, disparities in uptake were noted particularly among Black and Hispanic MSM; however, in recent years, more evidence has supported that these disparities may be a function of structural disadvantage rather than race/ethnicity [9]. Still, recent estimates show that of the estimated 1.1 million adults with indications for PrEP due to high HIV transmission risk, 74% identify as MSM [12]. However, one nationwide survey of MSM (N = 5,021) demonstrated that among those sampled, only 12% reported currently being on PrEP [13]. According to one mathematical modeling study of HIV transmission, with assumptions of PrEP uptake based on CDC PrEP guidelines, an increase in PrEP uptake by even 40% would avert a third of new infections among MSM [14]. Therefore, improving PrEP uptake among MSM is of critical public health concern, and further research to better understand the barriers and facilitators along the PrEP uptake cascade can inform PrEP implementation efforts.

The Modified Social Ecological Model provides a flexible model for situating HIV transmission risk, and therefore prevention, into multiple concentric contexts [15]. This model builds upon many existing models of HIV prevention by looking at higher order social and structural factors (e.g., community and public policy factors) in addition to individual-level risk factors. Indeed, a review of the empirical literature demonstrates a relationship between individual-level barriers to PrEP uptake including demographic (e.g., age, race/ethnicity), psychosocial (e.g., mental health symptoms, substance use) and attitudinal factors (attitudes towards the healthcare system, concerns about side effects or the efficacy of PrEP, or low perceived risk/self-efficacy; [16]). However, these factors exist within the context of structural factors, which also influence prevention behavior. For example, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that living in poverty, having unstable housing, and/or lacking current health insurance inhibit PrEP uptake [17–22]. Additionally, while much evidence points to a constellation of syndemic risk factors for HIV infection in MSM with incarceration histories [23], there has been much less research on PrEP uptake among MSM with such histories [24]. Notably, one criticism of PrEP is that it is a costly intervention that has not easily been integrated into HIV prevention services due to significant financial and logistical challenges [25].

Massachusetts provides a unique landscape to examine barriers to PrEP uptake in a sample of MSM with wide access to PrEP-related health services. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) convened a PrEP Clinical Advisory Group in 2012 with the goal of increasing PrEP access and uptake [26]. This effort has included working with community partners to launch the “PrEP Navigator Program” to help MSM with indications for PrEP identify a provider who could prescribe PrEP and provide sexual health care [27]. More recently, MDPH launched a statewide PrEP demonstration project and PrEP Drug Assistance Program to promote access to, and utilization of, PrEP by high-risk individuals, with a goal of reducing new HIV diagnoses among MSM by 30% in the year 2021 [26]. In addition to PrEP focused initiatives, Massachusetts also has the lowest uninsured rate (around 3%) among adults of any state [28] due in large part to the statewide Health Care Reform Act in 2006 (also known as, “Romney Care”) and the federal Affordable Care Act in 2010. This is significantly lower than the federal average, which is around 10% [29]. The current study is a secondary, descriptive analysis that sought to explore, in a climate of expanded healthcare access, demographic/behavioral, structural, and psychosocial differences between MSM reporting using PrEP in the past 12 months versus not.

Method

This analysis used data from the 2017 Boston sample of the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system. This consists of a standardized protocol for the purposes of surveying and testing those with behaviors which are high risk for HIV [30]. The NHBS rotates among three key populations on a three-year cycle: MSM, people who inject drugs, and heterosexuals at increased risk of infection. The current analysis uses data from the latest completed MSM cycle. The MSM cycle uses venue-based recruitment and is time-spaced. NHBS uses a formative planning process to identify venues wherein at least half of the clients are MSM. This planning process yielded a collection of venues (e.g., bars, clubs, social group events) wherein the days and times for recruiting participants were selected at random. Potential participants were screened to determine whether they were at least 18 years old, ever had sex with another man, resided in the Boston Metropolitan Statistical area, were able to complete the interview in English or Spanish, and were able to provide informed consent. Recruitment and data collection activities were conducted anonymously.

We assessed general characteristics of those who were eligible to complete the survey including insurance status, income, race/ethnicity, age, and education for the purposes of sample description. To assess the main question of the analysis, participants were classified as having an indication for PrEP according to CDC criteria; if they reported having 2 or more male partners in the past 12 months and reported either anal sex without a condom or a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the past 12 months; or having one or more anal sex encounters without a condom with a male partner living with HIV in the past 12 months. Fisher’s Exact Tests were used to assess the significance of associations of various characteristics with self-reported PrEP status due to low expected cell sizes. The MDPH Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Measures

The main outcome assessed was PrEP use in the past 12 months, which was a yes/no answer to the question, “In the past 12 months, have you taken anti-HIV medicines before sex because you thought it would keep you from getting HIV?” This analysis examined associations of PrEP use with demographic/behavioral, structural, and psychosocial/substance use factors.

Demographically, we examined associations with age, race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and Other), educational attainment (below high school graduate, high school graduate/technical school, or college graduate/professional degree), and sexual identity (heterosexual/straight, homosexual/gay, or bisexual). Behaviorally, we looked at whether participants were generally open or “out” about their sexual orientation. Participants were categorized as “out” if they answered yes to the question, “Have you ever told anyone that you are attracted to or have sex with men?” Participants were asked the same question with reference to a healthcare provider.

Structurally, we examined associations of PrEP use with educational attainment (below high school graduate, high school graduate/technical school, and college graduate/professional degree), income below the US federal poverty level [31], incarceration history (yes/no answer to, “Have you ever been held in a detention center, jail, or prison more than 24 hours?”), limited access to healthcare (yes/no answer to, “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed medical care but didn’t get it because you couldn’t afford it?”), health insurance coverage, recent homelessness, and sexual orientation related discrimination (yes/no answer to, “Were you denied or given lower quality health care because someone knew or assumed you were attracted to men?”).

Psychosocial factors examined in this analysis included presence of clinically significant mood symptoms, history of physical assault related to sexual identity, past month binge drinking, and use of non-injection drugs in the past 12 months. The Kessler-6 scale was used to assess for psychological distress including symptoms of depression and anxiety. The published cut-off of 12 was used to classify participant distress as clinically significant [32]. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.863. Participants were rated positive for binge drinking if they reported drinking five or more alcoholic drinks within a 2-hour period in the past 30 days.

Results

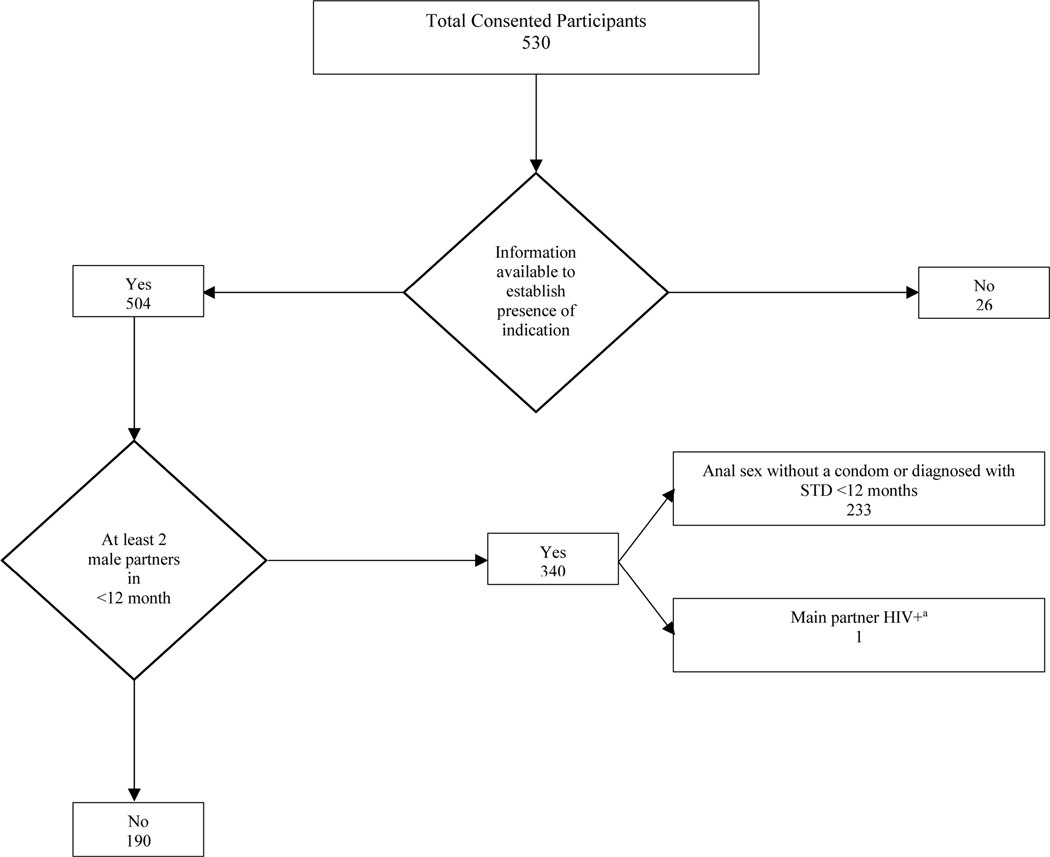

A total of 530 individuals were eligible and provided consent to participate in the 2017 Boston NHBS system (Figure 1). These individuals had a mean age of about 37.0 years old (SD= 12.8), 62.7% of participants identified as White, 8.2% of participants identified as Black, 16.0% of participants identified as Hispanic/Latinx, and 13.1% of participants identified as another race. Most participants were gay-identified (85.5%), 13.4 % identified as bisexual, and 1.1% identified as heterosexual. Approximately 97.6% of participants had disclosed their sexuality to at least one person. Structurally, 4.3% of the sample lacked health insurance, 8.3% reported an annual income below poverty, and 8.3% reported having an incarceration history. N=504 of these respondents had data necessary to classify whether PrEP was indicated and 233 participants (43.9%) met criteria for a PrEP indication.

Figure 1.

Flowchart demonstrating distributions of participants in the Boston NHBS cohort of men who have sex with men who were evaluated for indication of treatment with PrEP and self-reported PrEP status in the past 12 months

aCondomless sex with serodiscordant partner

Of the 233 respondents who met criteria for PrEP indication, 50.2% indicated having used PrEP in the past 12 months. Table 1 shows frequencies of the variables of interest and tests of their association with having used PrEP in the past 12 months. In terms of demographic and behavioral factors, use of PrEP was significantly associated with being out to their healthcare provider. Use of PrEP was not associated with age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or being out to at least one other person. With regard to structural factors, not using PrEP was significantly associated with a history of incarceration, limited use of healthcare due to cost, and lack of health insurance. Recent homelessness, annual income below the federal poverty line, and education were not associated with whether PrEP was used in the past year. In terms of psychosocial and substance use variables, recent binge drinking, history of physical assault related to sexual orientation, presence of clinically significant mental health symptoms, and non-injection drug use were not associated with PrEP use in the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Frequencies of variables of interest and tests of associations with self-reported PrEP status for N=233 Boston MSM

| Variables | PrEP use n (%) | Total | Two-sided p-value derived from Fisher’s Exact Testa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=117) | No (N=116) | |||

|

| ||||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age M (SD) | 35.4 (11.1) | 35.1 (12.4) | 35.3 (11.7) | t = −0.149, p =.882 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 80 (69.6) | 78 (67.8) | 158 (68.7) | .224 |

| Black | 3 (2.6) | 10 (8.7) | 13 (5.7) | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 23 (20.0) | 18 (15.7) | 41 (17.8) | |

| Other | 9 (7.8) | 9 (7.8) | 18 (7.8) | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | .247 |

| Gay | 104 (88.9) | 97 (84.3) | 201 (87.0) | |

| Bisexual | 12 (10.3) | 18 (15.7) | 30 (13.0) | |

| Out to other people | ||||

| No | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | .666 |

| Yes | 116 (99.1) | 114 (98.3) | 230 (98.7) | |

| Out to healthcare provider | ||||

| No | 2 (1.7) | 11 (9.6) | 13 (5.7) | .009** |

| Yes | 114 (97.4) | 103 (90.4) | 217 (94.3) | |

|

| ||||

| STRUCTURAL FACTORS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| ≤ High School | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | .910 |

| HS Diploma | 28 (23.9) | 29 (25.0) | 57 (24.5) | |

| Grad School | 88 (75.2) | 86 (74.1) | 174 (74.7) | |

| Annual Income | ||||

| No | 110 (94.0) | 105 (90.5) | 215 (92.3) | .317 |

| Yes | 7 (6.0) | 11 (9.5) | 18 (7.7) | |

| Incarcerated | ||||

| No | 114 (97.4) | 105 (90.5) | 219 (94.0) | .026* |

| Yes | 3 (2.6) | 11 (9.5) | 14 (6.0) | |

| Limited Access to Healthcare | ||||

| No | 113 (96.6) | 101 (87.1) | 214 (91.8) | .008** |

| Yes | 4 (3.4) | 15 (12.9) | 19 (8.2) | |

| Have health insurance | ||||

| No | 1 (0.9) | 12 (10.3) | 13 (5.6) | .001** |

| Yes | 116 (99.1) | 104 (89.7) | 220 (94.4) | |

| Homelessness | ||||

| No | 115 (98.3) | 115 (99.1) | 230 (98.7) | .999 |

| Yes | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) | |

| Sexual Orientation Discrimination in Healthcare | ||||

| No | 112 (95.7) | 113 (98.3) | 225 (97.0) | .446 |

| Yes | 5 (4.3) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (3.0) | |

|

| ||||

| PSYCHOSOCIAL/SUBSTANCE USE | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mental Health Symptoms | ||||

| No | 104 (89.7) | 104 (89.7) | 208 (89.3) | .999 |

| Yes | 13 (10.3) | 12 (10.3) | 25 (10.7) | |

| Physical Assault due to sexual orientation | ||||

| No | 113 (96.6) | 108 (93.3) | 221 (94.8) | .253 |

| Yes | 4 (3.4) | 8 (6.9) | 12 (5.2) | |

| Binge drinking in past month | ||||

| No | 73 (62.4) | 57 (49.6) | 139 (56.0) | .064 |

| Yes | 44 (37.6) | 58 (50.4) | 102 (44.0) | |

| Non-injection drug use (past 12 months) | ||||

| No | 45 (38.5) | 36 (31.0) | 81 (34.8) | .272 |

| Yes | 72 (61.5) | 80 (69.0) | 152 (65.2) | |

p <.05

p <.01

T-tests were used in place of Fisher’s exact test for continuous outcomes.

Given the dearth of literature and evidence of structural syndemics in MSM with incarceration histories, ancillary analyses explored correlations between incarceration history and other structural factors explored in the main analysis. Incarceration history was associated with lacking health insurance (Φ = −.253, p <.001), having annual income below poverty level (Φ =.197, p =.003), homelessness in the past year (Φ =.131, p =.045), and higher educational attainment (Cramer’s V =.175, p =.028). Incarceration history was not associated with limited use of healthcare due to cost (Φ =.123, p =.061) or experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings (Φ = −.045, p =.496).

Discussion

Over 40% of Boston MSM sampled in 2017 had an indication for PrEP, according to CDC criteria, reporting 2 or more male partners in the past 12 months and anal sex without a condom, a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the past 12 months, or having one or more anal sex encounters without a condom with a male partner living with HIV in the past 12 months. Using PrEP was significantly associated with reporting having health insurance, not lacking healthcare due to cost, never having been incarcerated, and being out to one’s healthcare provider. The most recent MSM cycle of the NHBS, which pools results from 20 U.S. cities, showed PrEP use among 35% of those with indications, an increase from 6% in 2014 [33]. In the present analysis, PrEP use among those with indications was around 50% from only around 10% in 2014 [34], suggesting that PrEP use in Massachusetts remains consistently above national rates. These findings are encouraging and suggest that efforts in Massachusetts to expand usage are having a positive impact. It was suggested that use of PrEP by 30–40% of those with indications in a community could result in the aversion of approximately one-third of incident HIV infections over a 10-year period and an even greater impact with increasing coverage [33]. While the current rates of PrEP use in our sample are encouraging, higher rates of PrEP use will be needed in order to reduce the number of HIV infections by 90%, consistent with the Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) initiative [35].

Our findings indicate that even in a state with exemplary health insurance coverage, cost-related issues remain problematic for some. In recent years, focus has shifted from individual-level barriers (e.g., race/ethnicity) to structural disparities, which impede uptake of PrEP among vulnerable groups of people. Insurance and other access-related issues have been chief among these [9, 21]. Obtaining a PrEP prescription typically involves consultation with a medical provider, thus the finding that insurance status was a significant correlate of PrEP uptake was not surprising. However, Massachusetts boasts the lowest uninsured rate in the US at approximately 3% [29]; yet, even in this sample with a small minority of people underinsured, the association with PrEP uptake was strong. The healthcare landscape of Massachusetts indicates a need to understand the complexity of individuals who may remain uninsured due to inability to afford health insurance, lack of eligibility for government-subsidized or employer-sponsored health insurance, challenges with the application processes, satisfaction with services that can be obtained without health insurance, or immigration concerns for themselves or others. These potential barriers speak to the need for a multimodal outreach strategy (e.g., affordable insurance options, convenient in-person assistance available in different languages, etc.) to continue to improve PrEP utilization. This outreach strategy should be informed by the experiences and desires of those in Massachusetts who are currently uninsured and should include those with insurance to understand other financial limits.

Cost remains a barrier to obtaining PrEP for many MSM. Results from this analysis showed lacking healthcare due to cost to be a barrier to PrEP uptake, but not living below the poverty line. Ancillary analyses did not show these two variables to be significantly correlated, supporting the notion that these two groups of people may not be the same. Out-of-pocket PrEP is approximately $1500 per month. While medication assistance programs exist to help with the actual cost of the medication, a significant portion of individuals (even those with private insurance who are well-resourced) have trouble accessing these programs and may not uptake PrEP as a result [36]. Additionally, there are still out-of-pocket costs associated with PrEP. These include insurance premiums, deductibles, and copayments. An analysis of young adult MSM receiving PrEP care at a private university infectious disease clinic showed that varying out-of- pocket costs were associated with non-use of PrEP when evaluated at 3-month follow-up [37]. There is currently a large need to quantify out-of-pocket costs and their relation to PrEP use over time so as to inform potential plans for subsidizing the cost of care to maximize PrEP use.

Such programs may be especially beneficial to ameliorate cost-related issues faced by those with a history of incarceration who face structural and stigma-related barriers to PrEP uptake [38]. Sexual minority individuals are incarcerated at a rate three times that of the general population [39]. Those involved in the criminal justice system often sit at the intersection of multiple overlapping risk factors for both HIV transmission and lack of access to care, including difficulty finding housing or employment and PrEP-specific barriers such as, concerns about cost, anticipated partner/family disapproval, and the impact of multiple barriers deprioritizing PrEP use [38]. In our sample, ancillary analyses suggest that homelessness, poverty, and lack of insurance are key issues facing this population. There is a lack of research on factors influencing PrEP uptake in incarcerated populations, especially Black and Latinx MSM. Available research suggests PrEP uptake may be impeded within criminal justice institutions as a function of both real and perceived threats of disclosing sexual orientation and institutional distrust [40]. Within these institutions, PrEP delivery should utilize outside organizations to enhance trust or, given the high risks for HIV in this population and the barriers that impede access to care, including PrEP, consider adopting risk-based World Health Organization guidelines for PrEP candidacy versus behavior-based CDC guidelines [40].

PrEP use depends on disclosure of behaviors that represent a substantial risk of HIV infection including condomless MSM behaviors whether or not one ascribes to the MSM label. Studies indicate, however, that fewer than half of MSM disclose their sexual orientation to their primary care providers or have conversations with their providers about HIV prevention [41,42]. Barriers to disclosure include internalized homophobia [43], anticipated discrimination on the basis of MSM identity [44], and judgement of elevated risk status based purely on MSM identity [45]. These disclosure concerns may be exacerbated among those with heightened risk (MSM of color and MSM engaged in sex work; [46]). Approximately 94% of Boston participants in this sample were out to their healthcare provider and this was significantly associated with PrEP use. Our findings in the context of the extant literature underscore the importance of disclosure of MSM behavior in uptaking PrEP and therefore the ongoing need for culturally competent and affirming care to facilitate disclosure of such information [47]. Resources/training for such care can be found in places like the National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center (www.lgbthealtheducation.org).

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample included is not particularly representative of the population of individuals who have the greatest difficulties accessing PrEP and may not be representative of all those in Massachusetts. This also reflects the strength and potency of these structural and demographic factors. Recruitment was venue-based and, as alluded to in previous iterations of MSM, NHBS venues tend to be more integrated versus MSM-specific. Urban and suburban MSM tend to be overly represented in PrEP users, and it is possible that our Boston sample may overestimate PrEP use compared to more rural areas of Massachusetts. Secondly, our sample size was relatively small, yielding small cell sizes in some cases and preventing us from being statistically powered to run more complex analyses (e.g., logistic regressions). Additionally, analyses were cross-sectional, preventing us from making causal inferences. There were also several variables that have been correlated with PrEP uptake which were not examined here including medical mistrust, risk appraisals, and the multilevel barriers among individuals with intersecting identities, which may impede PrEP uptake. Lastly, the survey was administered by an interviewer, which may have led respondents to answer in socially desirable ways.

Massachusetts provides a unique landscape to describe factors associated with PrEP use as health insurance is less of a barrier for many to obtain preventive services. Indeed, rates of PrEP use in this sample surpass the national PrEP usage statistics. Still, however, barriers to PrEP uptake exist among those who may not be “highly resourced,” specifically individuals who lack access to care, those who have a history of incarceration, or those who have not yet disclosed their sexual orientation to their healthcare provider. In service of meeting EHE goals of reducing new infections by 90%, PrEP expansion efforts must focus on identifying, assessing, and engaging these individuals in prevention efforts.

Acknowledgements:

This publication was made possible by Grant Numbers T32 AI007433 and 5P30AI060354-15 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Ken Mayer has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead Sciences. The other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Statement Regarding Informed Consent:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statement Regarding Ethical Approval:

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018. (Updated). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer KH, Skeer M, Mimiaga MJ. Biomedical approaches to HIV prevention. Alcohol Res Health. 2010. November 3;33(3):195–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayer KH, Molina JM, Thompson MA, Anderson PL, Mounzer KC, De Wet JJ, ... & Hare CB (2020). Emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (DISCOVER): primary results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet, 396(10246), 239–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2237–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer KH, Safren SA, Elsesser SA, et al. Optimizing Pre-Exposure Antiretroviral Prophylaxis Adherence in Men Who Have Sex with Men: Results of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of “Life-Steps for PrEP”. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1350–1360. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1606-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan PS, Giler RM, Mouhanna F, et al. Trends in the use of oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection, United States, 2012–2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan PS, Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, et al. National trends in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness, willingness and use among United States men who have sex with men recruited online, 2013 through 2017. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(3):e25461. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS. 2017;31(5):731–734. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield TH, Starks TJ, Grov C. Uptake of HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in a National Cohort of Gay and Bisexual Men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(3):285–292. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition--United States, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6446a4.htm?s_cid=mm6446a4_w. Published November 2015. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grov C, Jonathan Rendina H, Patel VV, Kelvin E, Anastos K, Parsons JT. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with the Use of HIV Serosorting and Other Biomedical Prevention Strategies Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a US Nationwide Survey. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2743–2755. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2084-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenness SM, Goodreau SM, Rosenberg E, et al. Impact of the Centers for Disease Control’s HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Guidelines for Men Who Have Sex With Men in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(12):1800–1807. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. Limited Awareness and Low Immediate Uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among Men Who Have Sex with Men Using an Internet Social Networking Site. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, Leibowitz AA. Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1136–1145. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hannaford A, Lipshie-Williams M, Starrels JL, et al. The Use of Online Posts to Identify Barriers to and Facilitators of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Among Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Comparison to a Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed Literature. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1080–1095. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng P, Su S, Fairley CK, et al. A Global Estimate of the Acceptability of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Among Men Who have Sex with Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1063–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1675-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, Eddy JA, Halkitis PN. Acceptability of PrEP Uptake Among Racially/Ethnically Diverse Young Men Who Have Sex With Men: The P18 Study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(2):112–125. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.2.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wao H, Aluoch M, Odondi GO, Tenge E, Iznaga T. MSM’s Versus Health Care Providers’ Perceptions of Barriers to Uptake of HIV/AIDS-Related Interventions: Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2016;28(2):151–162. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2016.1153560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. The high prevalence of incarceration history among Black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):448–454. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaller ND, Neher TL, Presley M, et al. Barriers to linking high-risk jail detainees to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231951. Published 2020 Apr 17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan PS, Siegler AJ. Getting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to the people: opportunities, challenges and emerging models of PrEP implementation. Sex Health. 2018;15(6):522–527. doi: 10.1071/SH18103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Massachusetts Integrated HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care Plan. https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2016/12/vz/mass-hiv-aids-plan.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massachusetts Department of Public Health. HIV/AIDS Service and Resource Guide. https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2018/01/09/resources-guide.pdf. Published January 2018. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser Family Foundation. Election 2020: State Health Care Snapshots. https://www.kff.org/statedata/election-state-fact-sheets/. Published February 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin M, Gurewich D, Muhr K, Posner H, Rosinski J, & LaFlamme E. The Remaining Uninsured in Massachusetts: Experiences of Individuals Living without Health Insurance Coverage. https://www.bluecrossmafoundation.org/sites/default/files/download/publication/Remaining_Uninsured_Final.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/systems/nhbs/index.html. Updated May 2020. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. US federal poverty guidelines used to determine financial eligibility for certain federal programs. https://aspe.hhs.gov/2017-poverty-guidelines. Published January 2017. Accessed August 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finlayson T, Cha S, Xia M, et al. Changes in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Awareness and Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - 20 Urban Areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(27):597–603. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6827a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klevens RM, Martin BM, Doherty R, Fukuda HD, Cranston K, DeMaria A Jr. Factors Associated with Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in a Highly Insured Population of Urban Men Who Have Sex with Men, 2014. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1879-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doblecki-Lewis S, Liu A, Feaster D, et al. Healthcare access and PrEP continuation in San Francisco and Miami following the US PrEP demo project. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2017;74(5), 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel RR, Mena L, Nunn A, et al. Impact of insurance coverage on utilization of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0178737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Peterson M, Arnold T, et al. Knowledge, interest, and anticipated barriers of pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and adherence among gay, bisexual, and men who have sex with men who are incarcerated. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0205593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer IH, Flores AR, Stemple L, Romero AP, Wilson BD, & Herman JL (2017). Incarceration rates and traits of sexual minorities in the United States: National Inmate Survey, 2011–2012. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), 267–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Peterson M, Zaller ND, & Wohl DA (2019). Best practices for identifying men who have sex with men for corrections-based pre-exposure prophylaxis provision. Health & justice, 7(1), 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metcalfe R, Laird G, Nandwani R. Don’t ask, sometimes tell. A survey of men who have sex with men sexual orientation disclosure in general practice. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(14):1028–1034. doi: 10.1177/0956462414565404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2015;29(7):837–845. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos GM, Beck J, Wilson PA, et al. Homophobia as a barrier to HIV prevention service access for young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(5):e167–e170. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318294de80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maloney KM, Krakower DS, Ziobro D, Rosenberger JG, Novak D, Mayer KH. Culturally Competent Sexual Healthcare as a Prerequisite for Obtaining Preexposure Prophylaxis: Findings from a Qualitative Study. LGBT Health. 2017;4(4):310–314. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowan D, DeSousa M, Randall EM, White C, Holley L. “We’re just targeted as the flock that has HIV”: health care experiences of members of the house/ball culture. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53(5):460–477. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2014.896847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Irvin R, Wilton L, Scott H, et al. A study of perceived racial discrimination in Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and its association with healthcare utilization and HIV testing. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(7):1272–1278. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0734-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beyrer PC, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, et al. A call to action for comprehensive HIV services for men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):424–438. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61022-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]