Abstract

Purpose of Review

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) has emerged as an effective treatment option for patients with rotator cuff arthropathy resulting from irreparable rotator cuff tears. However, patients with combined loss of abduction and external rotation may still experience functional deficits after rTSA. One option to address this has been the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer (LDTT), or modified L’Episcopo procedure. The purpose of this review is to describe the role of LDTT with rTSA and to critically evaluate the evidence on whether a supplemental LDTT ultimately improves patient function.

Recent Findings

Patients with an intact rotator cuff demonstrated a significant increase in active external rotation following rTSA compared to those with a deficient rotator cuff following rTSA. Compared to their pre-operative baseline assessments, patients who undergo rTSA with LDTT report significant improvements in active external rotation. However, a randomized trial comparing rTSA patients with and without LDTT failed to demonstrate a significant difference in active external rotation or patient-reported outcomes between groups.

Summary

Observational studies have shown that patients experience significant improvements in active range of motion and various patient-reported outcome measures following rTSA with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer. When directly comparing rTSA with LDTT to rTSA alone, the current literature fails to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in active external rotation or patient-reported outcomes at short-term follow-up. Further randomized controlled trials are required to fully understand the potential benefits of added tendon transfer in the rTSA patient population.

Keywords: Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, Rotator cuff arthropathy, Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer, Irreparable rotator cuff tear

Introduction

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (rTSA) serves as an effective means to improve shoulder function and active range of motion while alleviating pain for patients with rotator cuff arthropathy. Specifically, the rTSA prosthesis is designed to improve forward flexion and abduction by altering the shoulder center of rotation, increasing the deltoid lever arm, and partially constraining the articulation to prevent superior translation of the proximal humerus [1–3]. However, its impact on external rotation of the shoulder remains less predictable, particularly with the more medialized center of rotation common to the traditional Grammont prostheses [4, 5]. When rTSA is performed with an intact rotator cuff compared to a deficient rotator cuff, patients demonstrate significantly greater improvements in active external rotation (31.3° improvement when performed for osteoarthritis versus 16.3° improvement when performed for rotator cuff arthropathy, p=0.015) [6]. This has resulted in less satisfactory outcomes in patients with pre-operative combined loss of elevation and external rotation (CLEER), especially when advanced teres minor atrophy is present [7].

Transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon, initially described for obstetric brachial plexus palsy by L’Episcopo, was adapted to restore active external rotation in patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears [8••, 9•]. When early results indicated that rTSA was unable to restore external rotation in patients with CLEER, the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer was further modified for use in combination with rTSA with the goal of improving active external rotation and reversing external rotation lag signs [10•, 11•]. The purpose of this review is to present the recent literature on both the technical aspects and patient outcomes following LDTT in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

Functional and Surgical Anatomy of the Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer

The latissimus dorsi is a broad muscle of the posterior thorax that originates on the spinous processes of thoracic, lumbar, and sacral vertebrae as well as multiple ribs and the pelvis [12]. The muscle converges in a cephalad and lateral direction, and the musculotendinous unit rotates 90° through the axillary region as it passes towards its anteromedial humeral insertion [13]. The insertion site of the latissimus dorsi tendon, which is 37.1 mm broad, is located medial to the bicipital groove and approximately 17.3 mm distal to the perimeter of the lesser tuberosity [14]. This insertion is directly adjacent to the teres major insertion, with interconnecting fibers noted in many cases [15•]. In its native orientation, latissimus dorsi contraction induces adduction, internal rotation, and extension of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint [12].

Transfer of the latissimus dorsi tendon for humeral external rotation involves releasing it from the anteromedial humerus and transferring its insertion to the greater tuberosity. In an anatomic study, two areas of fibrous thickening were noted to limit excursion of the tendon during this transfer [13]. The first, the distal fibrous band (DFB), can be found in the area where the LD and TM tendons converge, approximately 36.5 mm proximal to the humeral insertion of the LD tendon. This band is in close proximity to the radial nerve, which passes directly inferior to it. The second fibrous band is a proximal connection between the LD tendon and triceps brachii, which helps tether the brachial plexus to the medial humerus.

The proximity of the LD tendon to neurovascular structures must be carefully noted. The neurovascular pedicle of the LD from the thoracodorsal artery and nerve can be found 85–140 mm proximal to the humeral insertion [13]. With regard to the neurovascular pedicle of the TM tendon, the lower subscapular nerve can be found an average of 7.4 cm medial to its humeral insertion [16•]. The axillary nerve traverses the quadrangular space only 27.1 mm (range 17–49 mm) proximal and superior to the humeral insertion of the LD and TM tendons. Similarly, the radial nerve passes through the triangular interval just 22.1 ± 3.6 mm distal and inferior to the humeral insertion [13]. This distance is somewhat dynamic such that both nerves are closer to the LDTT insertion in a position of adduction [17]. When the LDTT is performed, the tendon can be safely released directly off the humeral insertion under direct visualization. However, during passage of the tendon posteriorly towards the greater tuberosity, the posterior branches of the axillary nerve are obscured by the humerus. These fibers, crucial for deltoid motor function in rTSA, can be damaged if the tendon is passed too superficial as they are located along the deep surface of the posterior deltoid musculature in the area of the greater tuberosity [16•].

The fundamental principles of tendon transfers [18] and their application towards the LDTT for humeral external rotation are outlined in Table 1. In biomechanical studies, the transferred vector of the latissimus has been successful in producing humeral external rotation moments [19, 20]. However, it should be noted that the LDTT for humeral external rotation satisfies most, but not all of the fundamental tenets of tendon transfers.

Table 1.

Fundamental principles of tendon transfers as outlined by Wilbur and Hammert [18] with application to the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for rTSA in the context of combined loss of elevation and external rotation.

| Principle [18] | Application to rTSA with LDTTT | Pass/fail |

|---|---|---|

| Supple joints | rTSA maintains passive motion through a semi-constrained metal-on-polyethylene bearing surface | ✓ |

| Tissue equilibrium | rTSA is performed on a semi-elective basis and not in the context of non-healing wounds or developing scar formation | ✓ |

| Adequate strength and excursion | The latissimus dorsi is of adequate strength and has adequate excursion to be transferred to the greater tuberosity without an interpositional graft | ✓ |

| One tendon for each function | LDTT is designed to restore external rotation; elevation is achieved separately with the deltoid | ✓ |

| Collinear line of pull | The latissimus dorsi and posterosuperior rotator cuff do not have collinear lines of pull | ✘ |

| Expendable donor | The latissimus dorsi transfer does not cause significant morbidity as the pectoralis major can continue to function for adduction and internal rotation | ✓ |

| Synergistic or “in phase” transfer | The native latissimus dorsi is an adductor and internal rotator and is not in phase with the posterosuperior rotator cuff (abduction and external rotation) | ✘ |

Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer in Native Shoulders

The latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for humeral external rotation was initially described by L’Episcopo for use in obstetric brachial plexus palsies [9•]. The procedure was later modified by Gerber et al. [8••] to improve external rotation in patients with irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears [21]. The procedure has historically been accomplished using a two-incision technique [8••], although single-incision techniques have also been described [22]. The latissimus dorsi tendon is harvested sharply from the bone interface or may include a small wafer of bone [23]. The tendon is bought over the superior aspect of the humeral head and is secured to the supraspinatus footprint on the greater tuberosity using either suture anchors or transosseous tunnels. A partial repair of the rotator cuff can then be incorporated side-to-side along the transferred latissimus dorsi tendon in some cases [21].

Gerber et al. examined long-term outcomes of LDTT in patients with irreparable tears of the posterosuperior cuff at 10-year follow-up [24]. They noted a statistically significant increase in subjective shoulder values (SSV), constant scores, and pain scores at the time of final follow-up compared to pre-operative baseline [24]. Additionally, they found an increase in the range of shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation, as well as an increase in abduction strength [24]. Another study by El-Azab et al. with an average of 9.3-year follow-up found statistically significant improvements in constant scores, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores, and visual analog scores (VAS) for pain in patients who underwent latissimus dorsi transfer compared to pre-operative baseline [25]. However, only 19% of patients reported being pain-free, and there was a 10% clinical failure rate [25]. Failure rates have also been reported to be as high as 41%, with risk factors for failure including high-grade fatty infiltration of the posterosuperior rotator cuff and acromiohumeral interval less than 7 mm [26].

Surgical Technique for Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Two-incision and one-incision techniques have been described to combine the LDTT with rTSA in a single operative setting [10•, 11•]. In both techniques, the patient is placed in the beach chair position, and a deltopectoral approach is utilized. In the two-incision technique, the arm is then abducted and internally rotated, and a second incision is made just lateral to the posterior axillary crease [11•]. Under direct visualization, the tendon is released from its insertion on the humeral shaft and secured with a running, locking stitch. A large blunt clamp is passed from the anterior deltopectoral incision between the teres minor and deltoid and out the posterior axillary incision to retrieve the sutures which are then pulled with the tendon out the anterior deltopectoral incision. Great care is taken to safely develop the plane of tendon passage through the subdeltoid space to avoid damaging the posterior branches of the axillary nerve. In preparation for the humeral stem, the humeral head is resected at the anatomic neck, and the metaphysis and shaft are sequentially reamed and broached. The arm is positioned in adduction, 45° of hyperextension, and 60° of external rotation, while the LDTT sutures are passed transosseously through the posterolateral aspect of the greater tuberosity. These sutures are then tied over a button on the intra-medullary surface of the cortex. Continuation of rTSA implantation is then performed in standard fashion.

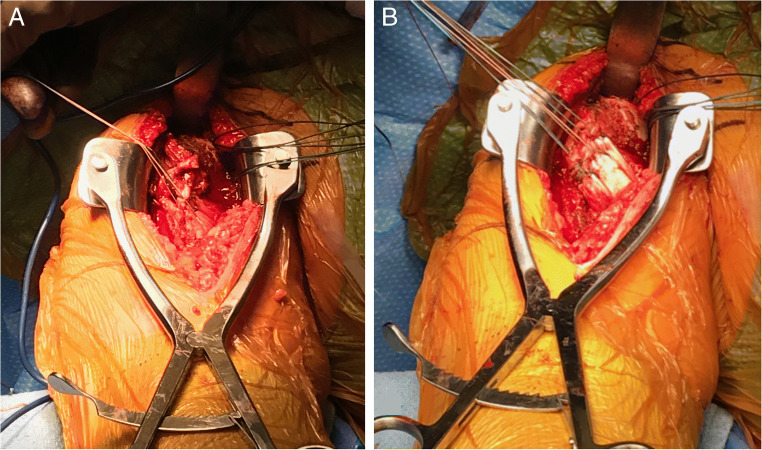

In the one-incision technique, the deltopectoral interval is used for both rTSA and LDTT. After completion of the deltopectoral approach, the upper third to half of the pectoralis major is divided at its musculotendinous junction, leaving a cuff of healthy tissue for later repair [10•]. Medial reflection of the pectoralis major reveals the insertion of the latissimus dorsi and teres minor. These tendons are released directly off the humerus while the arm is progressively externally rotated to keep the fibers on tension. The LD and TM tendons are sutured together with heavy non-absorbable suture, or alternatively the LD is secured alone with the heavy non-absorbable suture (Figure 1A). The tendons are mobilized bluntly (Figure 1B) and then passed posteriorly around the humerus using a curved clamp. These tendons are then secured to the proximal humerus either at stump of the pectoralis major tendon or transosseously through the greater tuberosity, as tendon excursion allows similar to the two-incision technique [10•].

Figure 1.

Operative photos of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer. A Heavy sutures fixed to the latissimus dorsi tendon through the anterior deltopectoral incision. B Latissimus dorsi tendon excursion demonstrated following blunt mobilization. Photos courtesy of Dr. Brian Waterman.

Although different locations for tendon attachment can be used, recent studies have suggested that the location of the latissimus dorsi transfer may also have implications in restoring function in rTSA. Chan et al. showed in a biomechanical study that transferring the latissimus dorsi tendon to the greater tuberosity at the teres minor footprint resulted in significantly greater external rotation torques than when it was transferred to the lateral humeral shaft [20]. However, this must be balanced with a more proximal transfer location being further from the LD tendon footprint, therefore requiring greater tendon excursion and potentially over-constraining the rTSA.

Outcomes of Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

There have been several studies investigating the results of latissimus dorsi tendon transfer in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Boileau et al. initially reported results of 11 patients undergoing rTSA with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer [27]. Post-operative mean active elevation increased from 70 to 148° and external rotation increased from −18 to 18°; there was one transient axillary nerve palsy that resolved without intervention. In another prospective cohort of 17 patients, Boileau et al. noted similar improvements with elevation increasing from 74 to 149° and external rotation increasing from −21 to 13° [28]. In both studies, there was no control group for comparison.

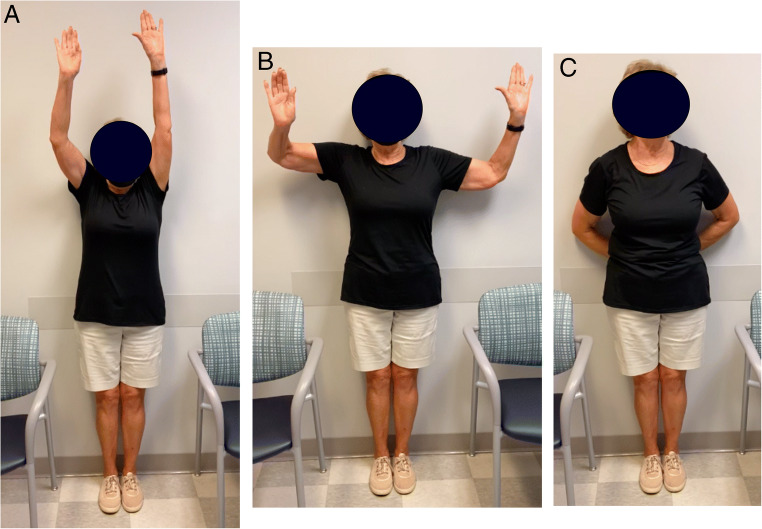

Similarly, Popescu et al. examined ten patients with combined loss of active elevation and external rotation (CLEER) who underwent rTSA without subscapularis repair with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer [29]. The authors reported improvements in outcome scores and range of motion compared to pre-operative baseline at an average of 57 months post-operatively. Specifically, constant score improved from 29.8 to 71.9 (p<0.05), and active external rotation improved from a mean of 0 to 21° (p<0.05). Patients were able to demonstrate post-operative external rotation force of 3.65 kg with external rotation at the side and 4 kg with external rotation in abduction. This study did not include a control group or pre-operative force measurements making it difficult to appreciate how much improvement in these patients undergoing rTSA can be attributable to the tendon transfer. Figure 2 demonstrates post-operative range of motion in a patient with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with CLEER who underwent right rTSA with LDTT, who experienced significant improvements in range of motion, including forward flexion (Figure 2A), external rotation (Figure 2B), and internal rotation (Figure 2C). The patient was also able to return to racquet sports post-operatively.

Figure 2.

Post-operative range of motion in a patient with glenohumeral osteoarthritis with combined loss of elevation and external rotation following right reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer. A forward flexion. B external rotation. C internal rotation. Photo courtesy of Dr. Brian Waterman.

In a series of 17 patients with minimum 5-year follow-up, Valenti and colleagues demonstrated impressive improvements in active range of motion after rTSA with LDTT [30]. In their cohort, forward elevation increased by 58.2°, external rotation at the side increased by 31.8°, and external rotation in abduction increased by 47.1° (p<0.05 when compared to pre-operative values for all). Constant scores, simple shoulder test scores, and subjective shoulder value scores all improved significantly from baseline pre-operative values. Two infections with cutibacterium acnes were noted (11.8%). No control group was presented for comparison. Another series of 21 patients reported by Shi et al. found similar results [31]. In that series, active forward flexion improved by 64°, active external rotation at the side improved by 30°, and active external rotation in abduction improved by 44° (p<0.001 for all). There were significant reductions in lag signs, as well as significant improvements in single assessment numeric evaluation (SANE) scores. One axillary nerve palsy was reported (4.8%) and was managed without surgical intervention.

Flury et al. also examined a series of patients with an external rotation deficit who underwent rTSA with or without a latissimus dorsi tendon transfer [32]. As a control group, they also examined patients without an external rotation deficit who underwent rTSA. All groups experienced improvements compared to baseline, and there was a significant difference in active external rotation between those with an external rotation deficit who received a tendon transfer and controls at 24-month follow-up [32]. Although this difference in active external rotation between treatment and control groups persisted at the final 60-month follow-up, it did not reach statistical significance at that time point [32].

A systematic review analyzed studies of rTSA patients who underwent latissimus dorsi and teres major (LD-TM) transfers [33]. The authors found that LD-TM transfer patients experienced a significant improvement in their constant score (28 to 65, p<0.0005) and active external rotation (−7.4 to 22.9°, p<0.0005) compared to their pre-operative values at an average follow-up of 44.5 months. None of the included studies directly compared LD-TM transfer patients to those who underwent rTSA alone.

Most recently, Young et al. performed a randomized controlled trial in patients undergoing rTSA for RCA with CLEER comparing patients who underwent concurrent combined latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer to those who did not [34••]. Although both groups saw improvements compared to their pre-operative baselines at 2-years post-operatively, the authors found no significant difference in active external rotation with the elbow in 90° abduction between those who underwent concurrent tendon transfer and those who did not [34••]. The added tendon transfer also did not result in a significant difference in patient-reported outcomes between the two groups post-operatively.

While published complications are unusual, latissimus dorsi transfers in rTSA do carry inherent risks and potential drawbacks. Flury et al noted that the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer resulted in an average increase in surgical time by 26 min [32]. Two observational studies have reported osteolysis at the latissimus dorsi transfer site on the proximal humerus in rTSA patients and suggested that this may place the proximal humeral cortex at risk for fracture and that long-stemmed prostheses may limit potential consequences of this finding [35, 36]. In the systematic review by Wey and colleagues, the complication rates for infection, dislocation, and aseptic loosening were comparable to reported rates for rTSA alone [33]. Three nerve injuries were identified (two radial nerve and one axillary nerve palsy, 3.4% incidence). The authors concluded that potential benefit of improving function and patient satisfaction outweighed the risks of incorporating the LD-TM transfer in rTSA patients with CLEER [33].

Conclusions

The latissimus dorsi tendon transfer can be performed in the setting of rTSA with a low rate of complications, so long as careful consideration is given to the proximity of the axillary and radial nerves. Observational studies have shown that patients experience significant improvements in active range of motion and various patient-reported outcome measures following rTSA with latissimus dorsi tendon transfer. Studies directly comparing rTSA with LDTT to rTSA alone have failed to show a statistically significant difference in active external rotation or patient-reported outcomes at short-term follow-up. Further randomized controlled trials are required to fully understand the potential benefits of this added intervention in the rTSA patient population, particularly when CLEER and external rotation lag signs are present.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Donald Scholten, Nicholas Trasolini, and Brian Waterman declare that they have no conflicts of interest that pertains to this work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Donald J. Scholten, II, Email: dscholte@wakehealth.edu.

Nicholas A. Trasolini, Email: ntrasoli@wakehealth.edu

Brian R. Waterman, Email: bwaterma@wakehealth.edu

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Nyffeler RW. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(5):284–295. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker M, Brooks J, Willis M, Frankle M. How reverse shoulder arthroplasty works. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2440–2451. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackland DC, Roshan-Zamir S, Richardson M, Pandy MG. Moment arms of the shoulder musculature after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1221–1230. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ackland DC, Richardson M, Pandy MG. Axial rotation moment arms of the shoulder musculature after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(20):1886–1895. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: The Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2006;15(5):527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waterman BR, Dean RS, Naylor AJ, Otte RS, Sumner-Parilla SA, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Comparative clinical outcomes of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary cuff tear arthropathy versus severe glenohumeral osteoarthritis with intact rotator cuff: a matched-cohort analysis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(23):e1042–e10e8. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simovitch RW, Helmy N, Zumstein MA, Gerber C. Impact of fatty infiltration of the teres minor muscle on the outcome of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):934–939. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.••.Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):51–61 First desription of the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. [PubMed]

- 9.•.L'Episcopo J. Tendon transplantation in obstetrical paralysis. Am J Surg. 1934;25(1):122–125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(34)90143-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.•.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Neyton L, Trojani C. Modified latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer through a single delto-pectoral approach for external rotation deficit of the shoulder: as an isolated procedure or with a reverse arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2007;16(6):671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.•.Gerber C, Pennington SD, Lingenfelter EJ, Sukthankar A. Reverse Delta-III total shoulder replacement combined with latissimus dorsi transfer. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(5):940–947. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeno SH, Varacallo M. Anatomy, back, latissimus dorsi. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morelli MMDFM, Nagamori JMF, Gilbart MMDF, Miniaci AMDF. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive irreparable cuff tears: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2008;17(1):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moatshe G, Marchetti DC, Chahla J, Ferrari MB, Sanchez G, Lebus GF, Brady AW, Frank RM, LaPrade RF, Provencher MT. Qualitative and quantitative anatomy of the proximal humerus muscle attachments and the axillary nerve: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(3):795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.•.Ranade AV, Rai R, Rai AR, Dass PM, Pai MM, Vadgaonkar R. Variants of latissimus dorsi with a perspective on tendon transfer surgery: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2018;27(1):167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.•.Pearle AD, Kelly BT, Voos JE, Chehab EL, Warren RF. Surgical technique and anatomic study of latissimus dorsi and teres major transfers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(7):1524–1531. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.E.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gates S, Sager B, Collett G, Chhabra A, Khazzam M. Surgically relevant anatomy of the axillary and radial nerves in relation to the latissimus dorsi tendon in variable shoulder positions: a cadaveric study. Should Elb. 2020;12(1):24–30. doi: 10.1177/1758573218825476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilbur D, Hammert WC. Principles of Tendon Transfer. Hand Clin. 2016;32(3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Favre P, Loeb MD, Helmy N, Gerber C. Latissimus dorsi transfer to restore external rotation with reverse shoulder arthroplasty: a biomechanical study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2008;17(4):650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan K, Langohr GDG, Welsh M, Johnson JA, Athwal GS. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: transfer location affects strength. JSES Int. 2021;5(2):277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omid R, Lee B. Tendon transfers for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(8):492–501. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-08-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Rudolph T, Lichtenberg S, Liem D. Transfer of the tendon of latissimus dorsi for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff: a new single-incision technique. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88(2):208–212. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B2.16830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moursy M, Forstner R, Koller H, Resch H, Tauber M. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a modified technique to improve tendon transfer integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1924–1931. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerber C, Rahm SA, Catanzaro S, Farshad M, Moor BK. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for treatment of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: long-term results at a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1920–1926. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Azab HM, Rott O, Irlenbusch U. Long-term follow-up after latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(6):462–469. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muench LN, Kia C, Williams AA, Avery DM, 3rd, Cote MP, Reed N, et al. High clinical failure rate after latissimus dorsi transfer for revision massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2019.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Bicknell RT, Rochet N, Trojani C. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a modified latissimus dorsi and teres major tendon transfer for shoulder pseudoparalysis associated with dropping arm. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):584–593. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boileau P, Rumian AP, Zumstein MA. Reversed shoulder arthroplasty with modified L'Episcopo for combined loss of active elevation and external rotation. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2010;19(2 Suppl):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popescu IA, Bihel T, Henderson D, Martin Becerra J, Agneskirchner J, Lafosse L. Functional improvements in active elevation, external rotation, and internal rotation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with isolated latissimus dorsi transfer: surgical technique and midterm follow-up. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019;28(12):2356–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenti P, Zanjani LO, Schoch BS, Kazum E, Werthel JD. Mid- to long-term outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty with latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Int Orthop. 2021;45(5):1263–1271. doi: 10.1007/s00264-021-04948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi LL, Cahill KE, Ek ET, Tompson JD, Higgins LD, Warner JJP. Latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer with reverse shoulder arthroplasty restores active motion and reduces pain for posterosuperior cuff dysfunction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(10):3212–3217. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4433-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flury M, Kwisda S, Kolling C, Audige L. Latissimus dorsi muscle transfer reduces external rotation deficit at the cost of internal rotation in reverse shoulder arthroplasty patients: a cohort study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2019;28(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wey A, Dunn JC, Kusnezov N, Waterman BR, Kilcoyne KG. Improved external rotation with concomitant reverse total shoulder arthroplasty and latissimus dorsi tendon transfer: a systematic review. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25(2):2309499017718398. doi:10.1177/2309499017718398. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.•.Young BL, Connor PM, Schiffern SC, Roberts KM, Hamid N. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty with and without latissimus and teres major transfer for patients with combined loss of elevation and external rotation: a prospective, randomized investigation. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2020;29(5):874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein JS, Johnston PS, Sears BW, Patel MS, Hatzidakis AM, Lazarus MD. Osseous changes following reverse total shoulder arthroplasty combined with latissimus dorsi transfer: a case series. JSES Int. 2020;4(4):964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2020.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnevialle N, Elia F, Thomas J, Martinel V, Mansat P. Osteolysis at the insertion of L'Episcopo tendon transfer: incidence and clinical impact. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(4):102917. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]