Abstract

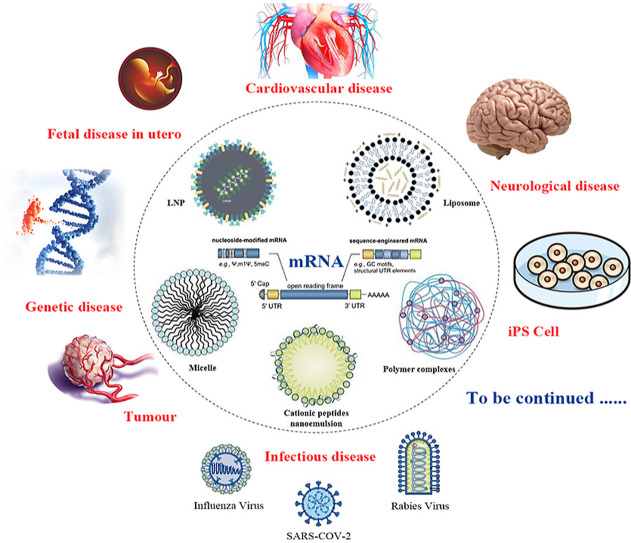

The current COVID-19 epidemic has greatly accelerated the application of mRNA technology to our real world, and during this battle mRNA has proven it's unique advantages compared to traditional biopharmaceutical and vaccine technology. In order to overcome mRNA instability in human physiological environments, mRNA chemical modifications and nano delivery systems are two key factors for their in vivo applications. In this review, we would like to summarize the challenges for clinical translation of mRNA-based therapeutics, with an emphasis on recent advances in innovative materials and delivery strategies. The nano delivery systems include lipid delivery systems (lipid nanoparticles and liposomes), polymer complexes, micelles, cationic peptides and so on. The similarities and differences of lipid nanoparticles and liposomes are also discussed. In addition, this review also present the applications of mRNA to other areas than COVID-19 vaccine, such as infectious diseases, tumors, and cardiovascular disease, for which a variety of candidate vaccines or drugs have entered clinical trials. Furthermore, mRNA was found that it might be used to treat some genetic disease, overcome the immaturity of the immune system due to the small fetal size in utero, treat some neurological diseases that are difficult to be treated surgically, even be used in advancing the translation of iPSC technology et al. In short, mRNA has a wide range of applications, and its era has just begun.

Keywords: mRNA, Nano delivery system, Material, Applications, COVID-19

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- SM-102

(heptadecan-9-yl 8-((2-hydroxyethyl) (6- oxo-6-(undecyloxy) hexyl) amino) octanoate

- DSPC

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3 phosphocholine

- DMG-PEG2000

1-monomethoxypolyethyleneglycol-2,3-dimyristylglycerol with poly-ethylene glycol of average molecular weight 2000

- ALC-0315

(4-hydroxybutyl) azanediyl)bis (hexane-6,1-diyl)bis(2-hexyldecanoate)

- ALC-0159

2-[(polyethylene glycol)-2000]-N,N ditetradecylacetamide

- DODAP

1, 2-Dioleoyl-3-Dimethylammonium-Propane

- DOBAQ

N-(4-carboxybenzyl)-N, N-dimethyl-2,3-bis(oleoyloxy)propan-1-aminium

1. Introduction

The mRNA (messenger RNA) is responsible for transferring genetic information from DNA to proteins [1]. In recent decades, there have been great breakthroughs in mRNA technology. And mRNA-based therapy has emerged as an effective platform for infectious diseases, cancer, genetic diseases, and so on. Compared to rRNA or tRNA, mRNA accounts for the smallest proportion of total RNA in the cell, has the shortest lifetime, and the differences between cells are relatively great, so it was the last one to be discovered and studied up to now. In 1960, Monod et al. [2] speculated the existence of a new type of RNA with short life period and named it messenger RNA, and it always appears with phage invasion of bacteria. In 1961, Brenner et al. [3] discovered the existence of a middleman between DNA and proteins. This important discovery showed that there must be a bridge between the chromosomes in the nucleus and the ribosomes in the cell. There exists a mechanism in the cell to transfer the genetic information in the nucleus to the cytoplasm. In 1964, Brenner et al. [4] experimentally proved the validity of the mRNA hypothesis. In 1978, scientists had used fatty membrane structures called liposomes to transport mRNA into mouse [5] and human [6] cells to induce protein expression. The liposomes packaged and protected the mRNA and then fused with cell membranes to deliver the genetic material into cells. In 1987, Malone [7] performed a landmark experiment. He mixed strands mixed strands of mRNA with droplets of fat, to create a kind of molecular stew. Human cells bathed in this genetic gumbo absorbed the mRNA, and began producing proteins from it. This was the first time that demonstrating the possibility of mRNA therapeutic applications.

As the core of genetics, DNA can only be transcribed into mRNA when it enters the nucleus. However, mRNA can initiate protein translation in the cytoplasm without entering the nucleus, which is much more efficient than DNA. Moreover, mRNA will not be inserted into the genome, and the protein encoded by mRNA will only be expressed instantaneously. In this way, there is no risk of gene integration. Furthermore, compared with protein and virus, mRNA production process is more simple and less cost, then it is easy to promote to industrial production.

However, mRNA is negatively charged and easy to be degraded by enzymes in vivo and in vitro, these all hinder its entry into cells and limit the application of mRNA. In addition to modifying mRNA to increase its own stability, it is more important to make an effective vehicle, which on the one hand, wrap and protect mRNA, on the other hand, break through the cell membrane barrier and deliver mRNA into the cytoplasm in a certain way.

At present, there has been an urgent need of vaccines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Among all approaches, mRNA-based vaccine has emerged as a rapid and versatile platform to quickly respond to such a challenge [8]. This review based on the research of mRNA in recent years, including the nano delivery systems, and innovative materials. Besides these, the application prospects and current problems of mRNA are also discussed.

2. The nano delivery systems of mRNA

Because mRNA is large (104–106 Da) and negatively charged, it cannot pass through the anionic lipid bilayer of cell membranes. Moreover, inside the body, because the mRNA is a single chain, it is extremely fragile, will be engulfed by cells of the innate immune system or degraded by nucleases [9]. The induction of an immune response by injection of naked mRNA in conventional and self-amplifying forms has been widely reported [[10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. However, mRNA delivery can be limited by the presence of extracellular exonucleases in the target tissues, inefficient cell uptake or unsuccessful endosomal release [15]. Various techniques, including electroporation, gene guns and ex vivo transfection can intracellularly deliver mRNA in a dish [16]. In vivo application, nevertheless, requires mRNA nano delivery system that transfect immune cells without causing toxicity or unwanted immunogenicity.

Fortunately, a number of innovative materials-based solutions have been developed for this purpose [17,18]. Currently, the commonly used nano delivery systems include lipid nano particles (LNPs), liposomes, lipid polycomplexes, polymer materials, micelles, polypeptides, protamine, electroporation, and so on [[19], [20], [21]]. LNPs and liposomes are one of the most promising mRNA delivery tools [22].

2.1. Lipid nano particles (LNPs)

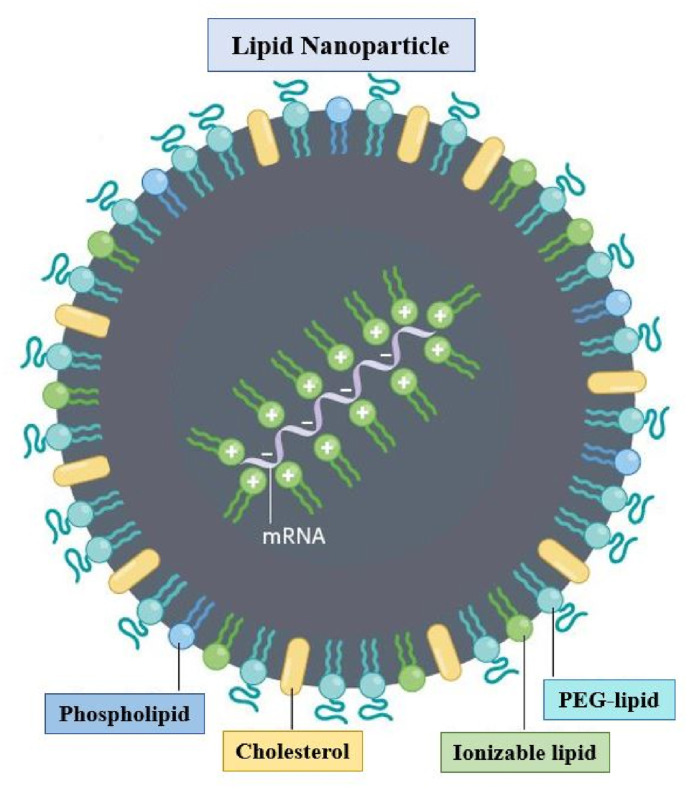

LNPs are currently the leading non-viral delivery vector for gene therapy [23]. As LNP-mediated siRNA therapeutic Onpattro® (patisiran) advanced towards clinical trials and subsequent approval [24], it was only natural that the mRNA delivery field adopted LNP technology. LNP is a biocompatible vehicle of phospholipid monolayer structure (Fig. 1 ), which could wrap mRNA in lipid nuclear and avoid degradation [25]. In addition to the negatively charged mRNA, the LNP generally have four other components: ionizable cationic phospholipids, neutral auxiliary phospholipids, cholesterol, and polyethylene glycol modified phospholipids. Among them, the neutral auxiliary phospholipids are generally saturated phospholipids, which can improve the overall phase transition temperature and stability [26]. Cholesterol has strong membrane fusion ability, which promotes the intracellular intake of mRNA and cytoplasmic entry [27]. PEGylated phospholipids are located on its surface to improve its hydrophilicity, avoid being quickly cleared by the immune system, prevent particle aggregation, and increase stability [28]. The most critical component is ionizable cationic phospholipid, which is the decisive factor for the efficiency of mRNA delivery and transfection [29,30]. It needs to be non-ionized under physiological conditions (pH = 7.4), but ionized under acidic conditions (≤5) [31]. At this point, the tertiary amine is protonated, and the phospholipids form a smaller zhiphoteric ion head and a hydrophobic chain tail, forming a conical structure, promoting the transformation of the membrane to hexagonal crystal phase to achieve efficient delivery and transfection [32]. The existence of carboxylic ester ensures the degradability of phospholipids in vivo and avoids the toxic and side effects caused by the accumulation of phospholipids [33].

Fig. 1.

Structure of LNP [7].

LNPs are prepared through rapid mixing, often facilitated by microfluidic devices [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. A particularly popular microfluidic preparation method is ethanol dilution, referring to the rapid condensation of lipids into nanodroplets when their ethanol solution is added to the excess of aqueous media [38]. The resulting LNPs may be considered a kinetic product and typically yield considerable encapsulation of nucleic acid.

There are currently two ‘conventional’ mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in use that delivering S-mRNA through LNPs. These are the mRNA-1273 vaccine by Moderna and the BNT162b2 by BioNTech/Pfizer (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Information about three mRNA-LNP products that are presently in use [39].

| Category | Moderna | BioNTech/Pfizer |

|---|---|---|

| Product | mRNA-1273 | BNT162b2 |

| mRNA dose | 100 μg | 30 μg |

| Components | SM-102 | ALC-0315 |

| DSPC | DSPC | |

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol | |

| DMG-PEG2000 | ALC-0159 | |

| Ionizable cationic lipid: neutral lipid: cholesterol: PEG-lipid (Molar ratios, %) | 50:10:38.5:1.5 | 46.3:9.4:42.7:1.6 |

| Molar N/P ratiosa | About 6 | 6 |

| Other excipients | Potassium chloride | Sodium acetate Sucrose Water for injection |

| Sodium chloride | ||

| Sucrose | ||

| Water for injection |

N = ionizable cationic lipid (nitrogen), P = nucleotide (phosphate).

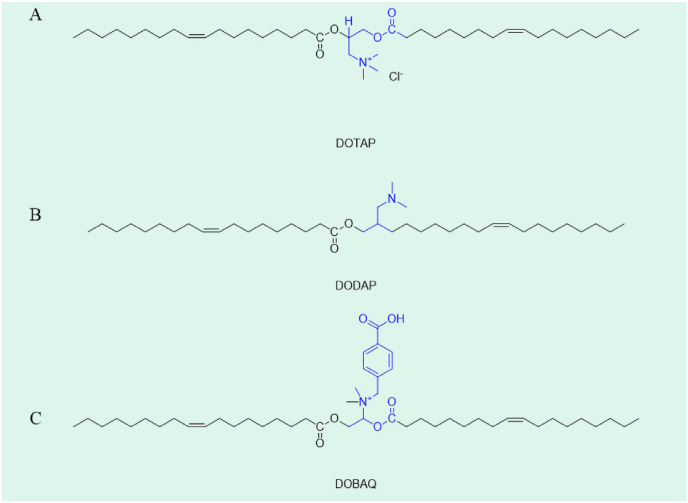

In addition to the LNPs listed in the table above, there are many novel LNPs with innovative materials in the R & D stage. Different materials have a great influence on the properties of LNPs. Aguado et al. [40] developed four kinds of LNPs with different composition for mRNA delivery (as shown in Table 2 ). In the comparison of DOTAP, DODAP and DOBAQ (as shown in Fig. 2 .), DOTAP as the only cationic lipid showed good stability after 7 months, and the stability was improved with the addition of polysaccharides.

Table 2.

Solid lipid nanoparticles with different formulations [40].

| Number |

Cationic lipids (%) |

Twain 80 (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTAP | DODAP | DOBAQ | ||

| 1 | 0.4 | 0.1 | ||

| 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| 3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | ||

| 4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

Fig. 2.

Structure of DOTAP, DODAP and DOBAQ.

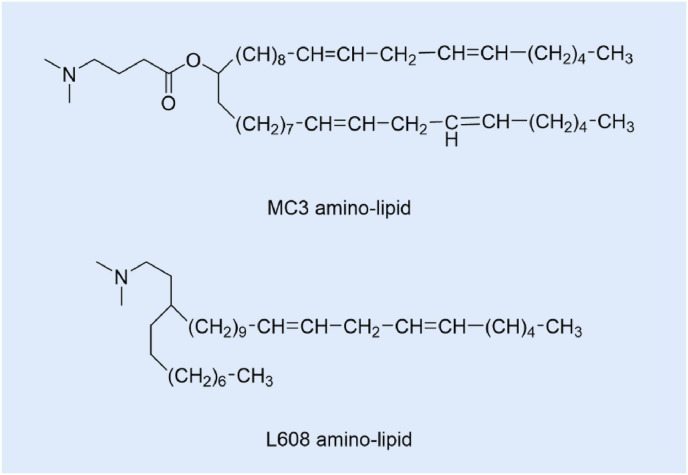

Davies et al. [41] found that subcutaneous injection of LNPs containing mRNA, can result in measurable secreted proteins in plasma exposure, but will be affected by dose limit of related inflammation. In order to overcome this limitation, the LNPs composed of MC3 amino-lipid and L608 amino-lipid (Fig. 3 .) were constructed, showing extended protein expression duration, which can realize system level of therapeutic proteins for chronic disease.

Fig. 3.

MC3 amino-lipid and L608 amino-lipid structures.

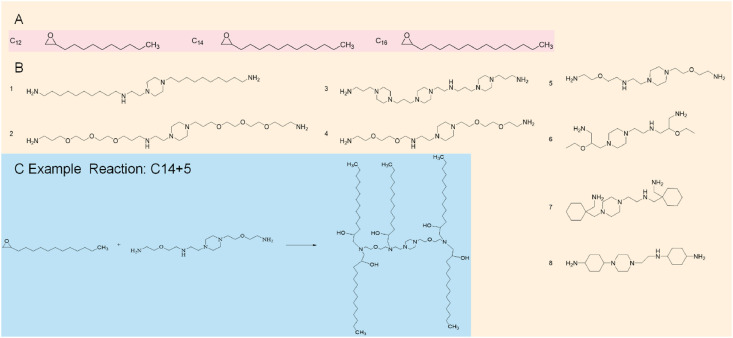

Billingsley et al. [42] investigated the efficacy of targeted therapies against chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T), which had the ability to induce remission in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and large B-cell lymphoma. However, CAR -T-cell engineering methods used viral vectors to induce permanent CAR expression, which may lead to serious adverse reactions. Therefore, in order to reduce the toxicity of adverse reactions, they designed LNPs for in vitro delivery of mRNA to human T cells. They used Michael addition to synthesize 24 isolable lipid libraries (as shown in Fig. 4 .) to synthesize LNPs and screen luciferase mRNAs for delivery into Jurkat cells. Seven isolable lipids were found to be able to alleviate symptoms by enhancing mRNA delivery via LNPs.

Fig. 4.

Structures of the AlkylChains (A) and Polyamine Cores (B) used to Generate the ionizable lipid library and Areaction scheme (C) of the Michael addition chemistry used to synthesize the ionizable lipids by reacting an excess of alkyl chains with the polyamine cores. “C14 + 5” was a representative reaction.

Yang et al. [43] proposed an ionizable LNPs based on IBL0713 lipids called ILP171, which was composed of IBL0713, cholesterol, C16-PEG, and mRNA. The mRNA encapsulated in ILP171 could successfully express proteins in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and hepatocytes, without toxicity or immunogenicity. Roshan et al. [44] found that mannose, as a stable cholesterol-amine conjugate, could enhance the efficacy of mRNA-LNPs through the enhanced uptake of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). During the study, LNPs were modified with different lengths mannan (from simple sugar to four sugars) to be MLNPs, indicating that with the increase of mannose chain length, the antibody response was remarkably improved. Compared with LNPs, the modified MLNPs showed increased IgG1 and IgG2A level, indicating improved immunogenicity.

Different LNPs also have different targeting and administration effects. Zhang et al. [45] used a microflow controller to prepare atomizable lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of mRNA to the lungs. During in vitro evaluations, high protein expression was detected. In addition, the luciferase protein was found to be highly expressed in the lungs of mice after the inhalation of four lead preparations.

The development of mRNA delivery by LNP is very fast. At present, many companies are developing mRNA LNP products for different diseases. Some of the mRNA-LNP technology in development or on the market was shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

mRNA-LNPs in development or on the market.

| Name | Adaptation disease | Company |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA-1273 | SARS-CoV-2 | Moderna |

| CV7202 | CureVac AG | |

| BNT-162b1 | BioTech | |

| BNT-162b2 | ||

| BNT-1623 | ||

| Tozinameran | ||

| ARCT-021 | Arcturus | |

| mRNA-1647 | Cytomegalovirus infection | Moderna |

| mRNA-1443 | ||

| mRNA-1345 | Metabolic virus infection Canine parainfluenza virus infections |

Moderna |

| mRNA-1653 | ||

| mRNA-1440 | Infectious disease | Valera LLC |

| mRNA-1851 | ||

| mRNA-1325 | Zika virus infection | Moderna |

| mRNA-1893 | ||

| CV-7202 | Rabies infection | CureVac AG |

| mRNA-1388 | Chikungunya virus infection | Valera LLC |

| mRNA-1172 | Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections | Moderna |

Although LNP is one of the most effective means for mRNA delivery, there is a virtually endless parameter space that can be modified in order to achieve a highly efficient, nontoxic, and tissue, organ, or cell-selective LNP formulation. In addition, the poor stability makes mRNA-LNP expensive to transport and store. The long-term storage of it is a significant yet underexplored part of the LNP lifecycle.

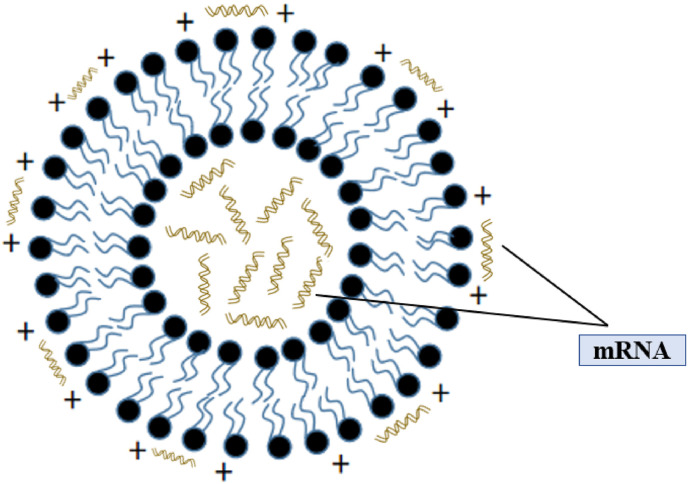

2.2. Liposome

Liposomes (Fig. 5 .) are spherical enclosed vesicles formed by phospholipid bilayer [46,47]. Liposome was first discovered by A. D. Bangham in 1965 and used for small molecule drug delivery for a long time, with particle size range from 20 nm to 1000 nm [48,49]. In addition to the encapsulation of small molecule chemotherapeutic drugs, more and more studies focus on the encapsulation and delivery ability of liposomes for gene drugs (including mRNA, pDNA, siRNA et al.), protein drugs, hormone drugs and so on. Cationic liposomes are positively charged, mainly composed of cationic lipids, which are able to efficiently concentrate nucleic acids in a targeted manner [50,51]. In addition, good pharmacokinetic properties can be obtained in vivo by changing the physical and chemical properties of cationic liposomes, such as adjusting the size of particle size and modifying the surface of cationic liposomes [52]. The commonly used phospholipid materials for mRNA delivery liposomes was shown in Table 4 . In general, the preparation methods of liposomes include thin film dispersion, solvent injection, freeze drying, pH gradient method, etc.

Fig. 5.

Structure of Cationic Liposome encapsulating mRNA.

Table 4.

The commonly used lipid materials for mRNA delivery.

| Phospholipid materials | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| (2, 3-dioleoacyl-propyl) -trimethylamine | DOTAP |

| 1, 2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerol-3- phosphate ethanolamine | DOPE |

| cholesterol | chol |

| 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine- N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] | DSPE-PEG2000 |

| anisamide | AA |

| Histidylated polylysine | HPK |

| l-histidine- (N, N-di-n-hexadecylamine)ethylamide | HDHE |

| O,O-dioleyl-N- [3N-(N-methylimidazoliumiodide)propylene] | KLN25 |

| O,O-dioleyl-N-histamine phosphoramidate | MM27 |

| 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine | DSPC |

| Poly-(β-amino ester)polymer | PBAE |

| 1, 2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine | DOPC |

| N-[1- (2,3-dioleyloxy)propyl]-N, N,N-trimethylammonium chloride | DOTMA |

| 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine | DOPS |

| 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] | C14-PEG2000 |

| 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-ethylphosphocholine | EDOPC |

There are a number of advantages to deliver mRNA by liposomes. Firstly, liposomes are spherical vesicles, which can encapsulate mRNA and resist nucleases. Secondly, liposomes are similar to cell membrane, easy to fuse with recipient cells and have high transfection efficiency. Thirdly, as a delivery system, liposomes are not subject to host restrictions. Finally, phospholipid double layered membrane structure highly simulates cell membrane. It is a stable structure known from biological evolution theory and has excellent long-term storage stability.

Michel et al. [53] prepared cationic liposome by thin film dispersion method, and encapsulated mRNA. The liposome was composed of 3B [N-(N, N-dimethylaminoethane) carbamyl](DC-cholesterol)/DOPE, and was stable even after stored at room temperature for 80 days. Kuznetsova et al. [54] modified DPPC liposomes with a non-covalent triphenylphosphine (1, 2-2 palmiacyl-Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate choline). Compared with tetradecylimidazolium hydrocarbon tail surfactant, the liposomes had higher stability for more than 4 months. Mai et al. [55] prepared cationic liposomes composed of DOTAP/CHOL/DSPES-PEG, by thin film dispersion method. Then mixed liposomes, mRNA and protamine at 10:1:1 to form stable liposome/protamine-mRNA complex. Through nasal administration, the study had shown greate efficiency and ability to stimulate dendritic cell maturation, and further inducing a strong anti-tumor immune response. Zhang et al. [56] modified DOTAP liposomes with cholesterol-modified cationic peptide DP7 with transmembrane structure and immune adjuvant function to form a common mRNA delivery system. It improves the efficiency of personalized neoantigen mRNA delivery and enhances the ability to activate dendritic cells (DCs). Huang [57] et al. first constructed RBD-encoding mRNA formulated in liposomes (LPX/RBD-mRNA), which could express RBD in vivo and successfully induced SARS-CoV-2 RBD specific antibodies in the vaccinated mice, then efficiently neutralized SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped virus. Moreover, the administration routes were found to affect the virus neutralizing capacity of sera derived from the immunized mice and the types (Th1-type and Th2-type) of cellular immune responses.

However, although mRNA has been successfully delivered through liposomes, liposomes have some disadvantages. Compared with LNP, the production process of liposome preparation and mRNA encapsulation is much more complex. In general, LNP and liposome are both lipid nanoparticles. They have many similarities, as well as great differences (as shown in Table 5 ).

Table 5.

The comparison between LNP and liposome.

| LNP | Liposome | |

|---|---|---|

| Similarities | Particle size distribution, shape, lipid composition, positive charge | |

| Differences | 1 Phospholipid monolayer structure | 1 Phospholipid bilayer structure |

| 2 The microfluidic preparation method | 2 The thin film dispersion method | |

| 3 Self assembly | 3 High energy dispersion | |

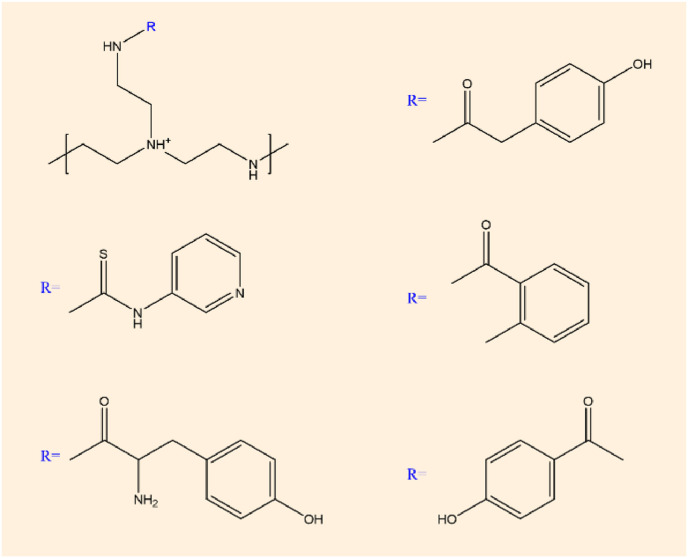

2.3. Polymer complexes

Although less explored, polymer based delivery systems can also be used. Polymer materials are high molecular weight (usually up to 10–106) compounds, which are repeatedly connected by covalent bonds from simple structural units, such as chitosan, polyethyleneimine, polyurethane, and so on. Most polymer materials used for mRNA delivery require modification to improve their transfection efficiency and stability [58]. Polyethylenimine (PEI) systems successfully delivered mRNA to cells [59] and intranasally [60]. Additionally, PEI-based systems improved the response to sa-mRNA vaccines in skin explants [61] and in mice [62].

Soliman et al. [63] prepared nanoparticles containing mRNA by electrostatic complexation, which were composed of different degrees of deacetylation and sulfonation. The results showed that the polymer length and charge density of hyaluronic acid and chitosan directly affected the transfection efficiency by regulating the mRNA affinity, and the mixture concentration of N:P:C ratio trehalose and the nucleic acid dose also affected the transfection efficiency. Choia et al. [64] reported an mRNA delivery system employing graphene oxide (GO)-polyethylenimine (PEI) complexes for the efficient generation of gene integration-free induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). GO-PEI complexes were found to be very effective for loading mRNA of reprogramming transcription factors and protection from mRNA degradation by RNase. Dynamic suspension cultures of GO-PEI/RNA complexes-treated cells dramatically increased the reprogramming efficiency and successfully generated rat and human iPSCs from adult adipose tissue-derived fibroblasts without repetitive daily transfection. Chiper et al. [65] chemically modified primary amine to aromatic domain, which realized nucleic acid transfer of 1.8 kDa polyethylenimine (PEI) particles. The modified chemical structure is shown in Fig. 6 . This modification does not affect the buffering capacity of polyethylenimine, but enhances its pH-sensitive aggregation, stabilizing extracellular complexes while still allowing nucleic acid to be released after cell entry.

Fig. 6.

Chemical structure of chemically modified polyethylenimine.

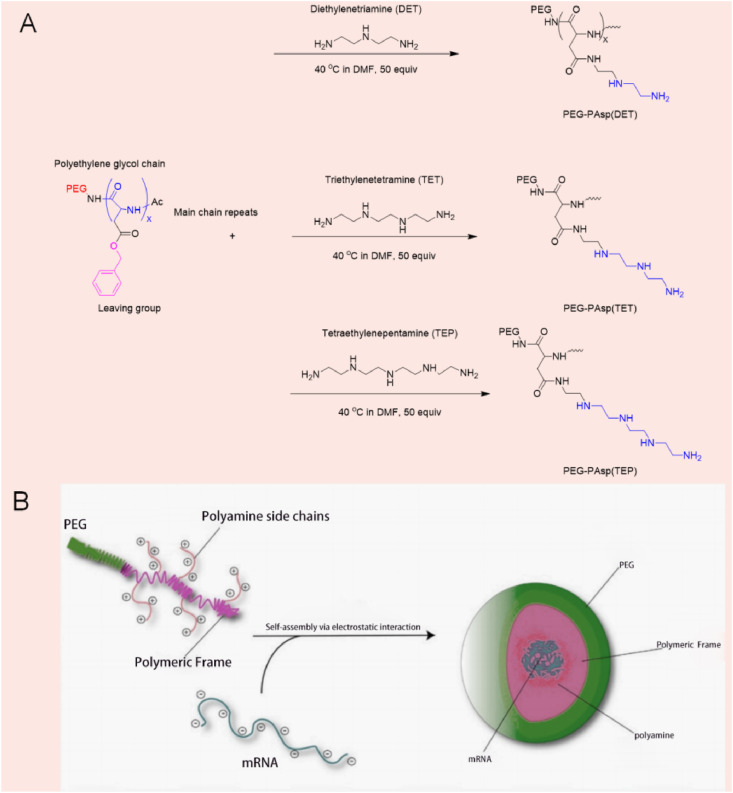

2.4. Micelles

Micelles refer to ordered aggregates of molecules that begin to form in large quantities after surfactant concentration reaches a certain value in aqueous solution. In micelles, hydrophobic groups of surfactant molecules aggregate to form the core of micelles, and hydrophilic polar groups form the outer layer of micelles [66]. Roloff [67] et al. studied the assembly of a novel RNA-polymer amphiphilic molecule into spherical micelle (as shown in Fig. 7 ) with diameters of about 15–30 nm, demonstrating that they can efficiently enter living cells without the use of transfection reagents. Chan et al. [68] propose the use of specially tailored polyplex nanomicelles for the intravenous delivery of mRNA into the brain of mice. In brief, along the backbone of a polyaspartamide polymer that is terminated with a 42k Polyethylene glycol chain (PEG), aminoethylene-repeating groups (two, three, and four units, respectively) were conjugated to side-chains to promote electrostatic interactions with mRNA. This structural configuration would ultimately condense into a polyplex nanomicelle ranging between 24 and 34 nm. Then the luciferase (Luc2) mRNA as a reporter gene through in vitro transcription (IVT) and subsequently infused the polyplex nanomicelles into mouse brains via an intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection to bypass the blood–brain barriers (BBB). Data revealed that PEGylated polyplex nanomicelles possessing four repeating units of aminoethylene groups had exhibited the best Luc2 mRNA delivery efficiency with no significant immune response registered, and may be applied in the treatment of brain diseases.

Fig. 7.

(A) Graphical illustration on the assembly of the polyamine of various length (DET, TET, and TEP) respective via the aminolysis of the benzylic alcohol side chains. (B) The subsequent condensation with mRNA into nanomicelles in physiological environment [68].

2.5. Cationic peptides

Peptide-based delivery is a less explored system, as only protamine has been evaluated in clinical trials [69]. New delivery approaches include the use of cationic cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) and anionic peptides. CPPs systems have proved to improve T-Cell immunity response in vivo [70], modulate innate immune response and enhance protein expression in both DC and human cancer cells in vitro [71,72]. mRNA polyplexes conjugated with an anion peptide, exhibited an increase in cellular uptake without inducing cytotoxicity in DC cells [73].

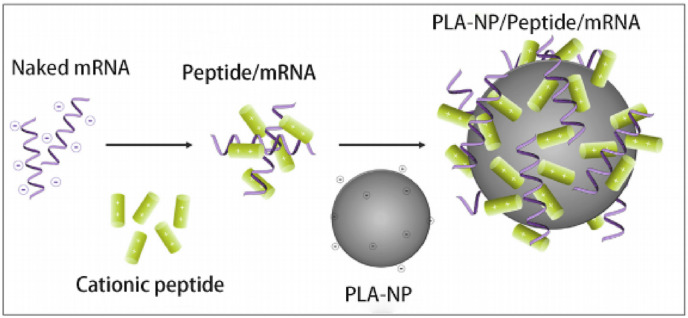

Qiu et al. [74] studied a novel RNA delivery vector, PEG12KL4, which synthesized cationic KL4 peptide (KLLLLKLLLLKLLLLK-NH2) and 12 monodisperse linear PEG molecules, PEG12KL4 and mRNA in a 10:1 ratio (w/w) to form a nanoscale complex, and mediate the effective transfection of human lung epithelial cells. The PEG12KL4/mRNA complex was successfully prepared by spray drying (SD) and spray freeze drying (SFD) techniques, and both SD and SFD powders showed satisfactory atomization inhalation stability and high transfection efficiency, which showed a great prospect for clinical application of PEG12KL4 peptide as mRNA delivery carrier. Coolen et al. [75] developed an alternative lipid-based mRNA delivery system using polylactic acid nanoparticles (PLA-NPs) and cationic cell-penetrating peptides as mRNA polycondensation agents. The formulation was assembled in two steps. The first step was to combine mRNA with an peptide (RALA, LAH4 or LAH4-L1), and the second was to absorb polymer on the surface of PLA-NPS, resulting in PLA-NP/Peptide/mRNA complex (as shown in Fig. 8 ). It modulated DCs innate immune response by activating endosomal and cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), and induced adaptive response markers in primary human DCs with universal Th1 signaling in vitro.

Fig. 8.

Composition of PLA-NP/peptide/mRNA [75].

In view of the great application potential of mRNA, more and more researches are advanced for mRNA nano delivery systems, and are bound to invent novel delivery vectors with stronger transfection efficiency, lower toxicity and better stability.

3. The applications of mRNA

The specific delivery of mRNA is an excellent alternative to plasmid DNA, due to the latter's potential risk for random integration into the host genome. With the development of mRNA modification technology and delivery technology, its application prospect is more and more widespread.

3.1. Infectious diseases

In addition, mRNA vaccine could activate both cellular and humoral immunity, achieving high protection rate. The research of mRNA vaccine focuses on RNA viruses with strong infectivity and high harmfulness, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), influenza A virus, rabies virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), Zika virus (Zika), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), Ebola virus (EBOV), and so on [76].

3.1.1. SARS-CoV-2

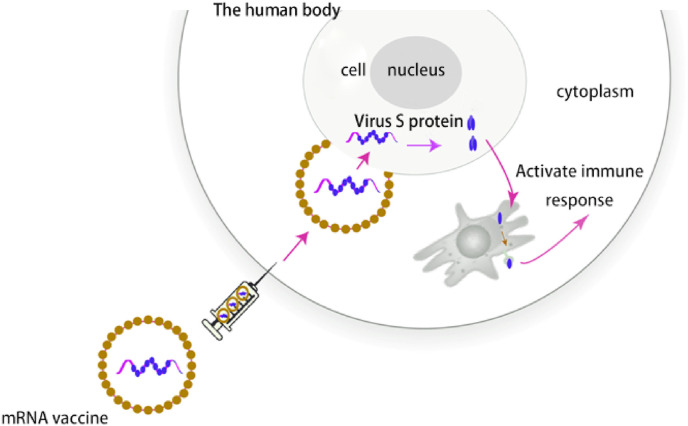

The development and technological breakthrough of mRNA vaccine in recent decades laid the foundation for its rapid rise during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. SARS-Cov-2 enveloped positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses, and the virion is composed of a helical capsid formed by nucleocapsid (N) proteins bound to the RNA genome and an envelope made up of membrane (M) and envelope (E) proteins, coated with “crown” like trimeric spike (S) protein, which is the main site for neutralizing antibodies and prone to mutation [77,78]. N501Y mutation can enhance the infectivity by enhancing the binding force with host ACE2 [79], while the variant G614 virus gradually replaced the originally discovered D614 as the main epidemic strain, and the patients with G614 will release more viral nucleic acid [80]. The variant strains with reduced antibody sensitivity will become the main strain, such as N439K is not only more infectious, but also has the ability to resist a variety of antibodies, including a neutralizing antibody authorized by the FDA for emergency use [81]. Highly mutated viruses pose a great threat to the effectiveness of existing vaccines, while mRNA vaccines can be rapidly applied by updating their sequences based on the mutated genes of the mutant strains. As shown in Fig. 9 , after entering the cytoplasm, S-mRNA could be translated to S protein, which were produced by the host cell and could induce immune response. Meanwhile, the mRNA vaccine also shortened time by using the body's own molecular mechanisms.

Fig. 9.

The immune mechanism of an mRNA vaccine [82].

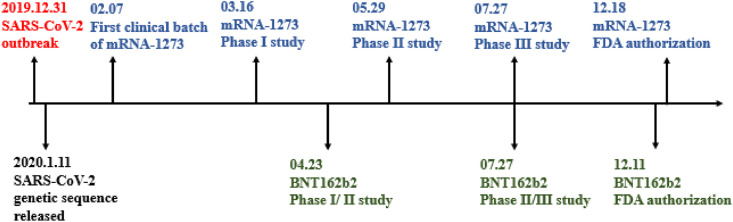

COVID-19 has caused a worldwide challenging and threatening pandemic, with huge health and economic losses. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted emergency use authorization for treatment with the BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna). They are both mRNA vaccines coated by LNPs that encodes S-protein. BNT162b2 has been recommended for people 16 and older at a dose of 30 μg and at a cost of $19.50. It provides immunogenicity for at least 119 days after the first vaccination and is 95% effective in preventing the SARS-COV-2 infection. However, mRNA-1273 has been recommended to people 18 years of age and older, with a dose of 50 μg at a cost of $32 to $37. It provides immunogenicity for at least 119 days after first vaccination and is 94.5% effective in preventing SARS-CoV2 infection. However, both vaccines have reported some associated allergic symptoms, including pain, redness, fever, fatigue, headache and muscle pain at the injection site [83]. The BNT162b2 was reported to have a lower incidence of adverse reactions compared to mRNA-1273; However, mRNA-1273 is more stable for transport and store. For nursing home residents in USA, two doses of mRNA vaccines were 74.7% effective against infection (March–May 2021). During June–July 2021, when B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant circulation predominated, effectiveness declined significantly to 53.1% [84]. Nevertheless, mRNA vaccine is still the vaccine with the shortest R & D and application cycle, and is expected to be rapidly upgraded for new strains. The timeline of mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 is showned in Fig. 10 .

Fig. 10.

Timeline of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273.

In addition to these, many more optimized mRNA vaccines against SARS-CoV2 are in the clinical or preclinical stage. Qin et al. [77] constructed mRNA-LNPs with much better stability at 2–8 °C, and is in clinical stage now. Lederer et al. [85] revealed the superior ability of SARS-CoV2 mRNA vaccine to induce a SARS-COV2-specific GCB cell response, which was associated with the effective production of Nabs after a single or enhanced immunization. In addition, it has been demonstrated that mRNA vaccine could effectively promote the induction of TFH cell program and shape the functional characteristics of TFH cells, emphasizing the importance of GC reaction for the production of protective ABS in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine vaccination, and pointing out that mRNA vaccine is a promising candidate vaccine for inducing effective and high-quality adaptive immune response. Corbett et al. [86] used it to make an mRNA vaccine and evaluated viral replication in non-human primates. Results showed that mRNA vaccine produced strong SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody without any pathological changes in the lungs.

3.1.2. Influenza

Martinon et al. [87] demonstrated immunization of animals by subcutaneous injection of mRNA liposome vaccines, inducing influenza-resistant cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. The flu vaccine was the first to attempt to use mRNA for disease prevention. Petsch et al. [88] evaluated the effects of multivalent mRNA vaccines (hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, and nucleoprotein) against influenza A (H1N1), H3N2, and H5N1 strains in mice, ferrets, and pigs. This intradermal mRNA vaccine induces antigen-specific neutralizing antibodies and protects the animal against influenza A virus. Similarly, in human trials conducted by Moderna, intramuscular vaccines against avian influenza A virus H10N8 and H7N9 have been shown to be safe and immunogenic [89].

3.1.3. Rabies

The protective effects of mRNA vaccines have been shown to be useful beyond respiratory pathogens. For example, Schnee et al. [90] demonstrated the efficacy of mRNA vaccines against rabies in rodents and pigs. The vaccine against viral glycoproteins induces an antigen-specific immune response in the body. Notably, mRNA vaccine induced more specific CD4+T cells than licensed vaccine induced cells, and neutralizing antibody titers remained stable in mice throughout the observation period (up to 1 year). The safety, reactivity, and immune response of this vaccine are currently being evaluated in a phase I trial of Curev AC (CV7202). Lou et al. [91] found that the amplified mRNA vaccine using LNPs to deliver the self-coding rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) had a good protective effect against rabies virus. Firstly, they compared several commonly used cationic lipids, and then selected DOTAP or DDA, which were the most efficient in inducing antigen expression, for animal evaluation of LNPs formed by them.

3.1.4. Zika virus

Pardi et al. [92] proposed a bivalently modified mRNA vaccine that encodes the foremembrane and envelope glycoproteins of the Zika virus strain in the 2013 outbreak. A single dose of the vaccine, encapsulated in LNPs and delivered intradermally, was sufficient to protect mice from viral attack two weeks or five months after vaccination and was sufficient to protect non-human primates five weeks after vaccination. Using the same antigen, Moderna has developed an unmodified, encapsulated mRNA-1893 vaccine against Zika, which received rapid FDA approval and was undergoing phase I trials to evaluate its safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity [93]. Importantly, mRNA-1893 prevented congenital transmission of the virus in a mouse model of congenital infection.

3.1.5. Cytomegalovirus

John et al. [94] have designed a cytomegalovirus (CMV) vaccine to prevent CMV infection and disease during pregnancy and in transplant patients. The vaccine consists of six modified mRNAs encoding CMV glycoprotein and pentameric complexes and was injected intramuscular in the form of LNPs. A single dose of it elicit a strong immune response in mice and non-human primates and was currently in a clinical trial sponsored by Moderna (mRNA-1647).

3.1.6. Chikungunya

In addition to enhancing active immunity, mRNA can also be used for passive immunity. The candidate drug mRNA-1944 is a good example of mRNA therapy that encodes human monoclonal neutralizing antibodies. The mRNA-1944 is designed to provide passive protection against chikungunya infection [95]. The super-potent antibody was isolated from B cells of natural infection survivors, and its sequence was encoded into mRNA molecules, encapsulated in LNPs, and delivered to mice by infusion. After mRNA delivery, CHKV-24, a human monoclonal antibody, was found to be expressed at immune-related levels and its protective ability was evaluated in a chikungunya mouse model. Treatment with CHKV-24 mRNA 2 days after inoculation reduced viremia to undetectable levels and protected mice from death. Further studies in non-human primates have also shown that the mRNA-1944 has long-lasting immunogenic effects [96]. In general, preclinical data encourage first human trials.

3.1.7. Neonatal herpes

Latourette II et al. [97] evaluated the protection of mRNA-LNP and protein vaccine against neonatal herpes by immunizing female mice before copulation, then compared the levels of IgG and neutralizing antibodies in mothers and newborns. Both vaccines protected first and second borns from disseminated infection, and proved effective in preventing neonatal herpes.

3.2. Tumor

The purpose of mRNA tumor vaccine is to prompt the cell-mediated response, such as the typical T lymphocyte response, so as to achieve the aim of remove or reduce tumor cell without harming normal cells [98]. STING is considered to be the center of the innate immunity and adaptive immunity adjustment factor. When stimulated, STING will induce type I interferon. The expression of cytokines and T cell recruiting factors leads to the natural effector cells of macrophages dendritic cells (such as NK) and the tumor specific T cells, which can not only express antigen in vivo, but also activate STING signaling pathway, and significantly enhance the tumor antigen-specific immune response. This also means that mRNA vaccines can be combined with other oncology therapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors and immune agonists, to achieve a more comprehensive oncology therapeutic effect [99].

Moderna, BioNtech and CureVac AG are three tycoon committed to mRNA technology, and invested a lot in the application of mRNA technology in tumor vaccine (as shown in Table 6 ). Several mRNA tumor vaccines are currently in clinical trials. CV9202 is a self-modifying mRNA vaccine that expresses six antigens commonly expressed in non-small cell lung cancer. mRNA-5671 targets KRAS and is currently being evaluated in patients with advanced or metastatic KRAS mutations in NSCLC, colorectal or pancreatic cancer. The mRNA-4157 is another cancer vaccine from Moderna, but, unlike mRNA-5671, it is an individualized therapeutic vaccine for melanoma. In this approach, gene sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of the patient's tumor is performed to identify 20 patient-specific neoantigen epitopes that are encoded by mRNA structures manufactured for an individual patient. BNT122 (phase II) is designed to treat locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors, including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and bladder cancer. BioNtech has a number of other anti-tumor vaccines in development, such as BNT111 for advanced melanoma, BNT112 for the treatment of metastatic castration against prostate cancer and high-risk localized prostate cancer, BNT114 for triple negative breast cancer, BNT115 for ovarian cancer and so on. BNT113 is anti-HPV16-derived oncoproteins E6 and E7, which are found in HPV16-positive solid cancers, such as squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Table 6.

The mRNA tumor vaccines of Moderna, BioNtech, and CureVac AG.

| Company | Name | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Moderna | mRNA-4157 | Personalized tumor vaccines |

| mRNA-5671, mRNA-2416, mRNA-2752, and so on. | Colorectal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, pancreatic cancer | |

| BioNTech | BNT111 | Advanced melanoma |

| BNT112 | Prostate cancer and high-risk localized prostate cancer | |

| BNT113 | HPV16-positive solid cancers | |

| BNT114 | Triple Negative Breast Cancer | |

| BNT115 | Ovarian cancer | |

| BNT122 | Melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, etc. | |

| CureVac AG | – | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| – | Superficial tumors |

Besides the above, cationic liposomes have been extensively studied in mRNA tumor vaccine and the preclinical studies have been conducted in different tumors [100,101](see Table 7 ).

Table 7.

A partially developed liposome containing mRNA.

The mRNA vaccine enhances the antiviral and antitumor effects of the host by enhancing the antigenic reactivity of T cells [105]. Some exogenous gene expression products directly act on immune cells and promote the growth and proliferation of immune cells. Thus, they could enhance the host's anti-tumor and antiviral capabilities.

3.3. Cardiovascular disease

There is a growing body of studies demonstrating utility of RNA for targeting previously ‘undruggable’ pathways involved in development and progression of cardiovascular disease. Despite significant advances in treatment options, cardiovascular disease remains the number one cause of death in the world [106].

One of the earliest nucleic acid therapies for cardiovascular disease was Mipomersen, a second-generation phosphorothioate ASO targeting mRNA encoding apolipoprotein B-100. ASOs have been chemically modified to have reduced toxicity. In a recent Phase II trial of TQJ230 [AKCEA-APO(a)-LRx], an ASO targeting lipoprotein(a) m RNA, more than 90% of patients achieved lipoprotein(a) concentrations below 50 mg/dl, after either 20 mg weekly injection or 60 mg injection every 4 weeks [107]. Another ASO that has reached clinical trials is volanesorsen. This ASO can be injected subcutaneously and functions by binding APOC3 mRNA and promoting its degradation. In a Phase II study, volanesorsen, decreased Apoc-II (−80%) and triglycerides (−71%), and increased HDL-cholesterol levels (46%) [108]. Another approach to lowering cholesterol is to target mRNA encoding the enzyme proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) which is predominantly produced in the liver [109].

Beyond drugs inhibiting endogenous mRNA, the first cardiovascular-related mRNA drug to have reached clinical trials, is the mRNA encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A mRNA (Moderna, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). In a Phase I study, intradermal administration of VEGF-A mRNA led increased local VEGF-A protein expression (as assessed by cutaneous microdialysis) and increased skin blood flow in men with type 2 diabetes [110]. Based on these results, a Phase 2a clinical trial will determine if this mRNA therapeutic restores ischemic but viable myocardial regions in patients with coronary artery disease, as assessed by ejection fraction [111]. This is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study in patients with moderately impaired systolic function undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients are randomized to doses of 0, 3, or 30 mg of VEGF A mRNA in a citrate buffer by epicardial injections. If this programmatic effort is successful, it would provide evidence that direct injection of mRNA into an ischemic tissue may improve perfusion and function.

3.4. Others

3.4.1. Genetic disease

Patel et al. [112] also used the microflow controller to prepare 11 lipid nanoparticles and tested their ability to deliver mRNA to the back of the eyeball. Studies have shown that lipid nanoparticles containing low PKA and unsaturated lipid chains have the highest number of reporter gene transfectants in the retina, and the gene expression kinetics show a rapid start (within 4 h) and a continuation of 96 h. Gene delivery is cell type specific, with most expression in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and limited expression in Muller glial cells, demonstrating that mRNA delivery by this drug delivery system can be used to treat single-gene retinal degenerative diseases of RPE and prevent blindness.

3.4.2. The immaturity of the immune system due to the small fetal size

Riley et al. [113] studied the use of LNPs in utero to overcome the immaturity of the immune system due to the small fetal size. They developed a library of LNPs for mRNA delivery to mouse fetuses in utero. The LNPs for luciferase mRNA delivery were first screened and formulations that could accumulate in the fetal liver, lung and intestine compared to the benchmark delivery systems with higher efficiency and safety, demonstrating that LNPs can deliver mRNA to induce liver production of therapeutic secretory proteins.

3.4.3. Neurological diseases

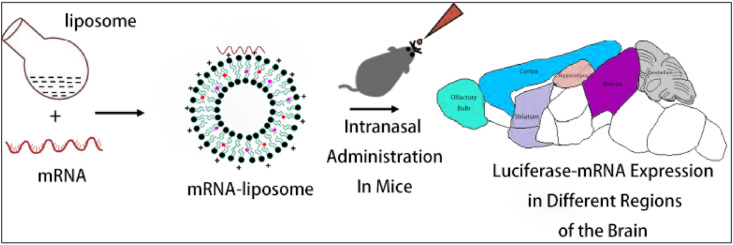

Dhaliwal et al. [114] developed an mRNA cationic liposome for the treatment of chronic diseases based on nucleic acid therapy, in which the liposome was composed of DOTAP, DPPC and cholesterol. The potential of intranasal delivery to the brain in mouse model has been evaluated. The results demonstrated the feasibility of brain-specific non-viral mRNA delivery in the treatment of various neurological diseases, as shown in Fig. 11 .

Fig. 11.

The range of the mRNA-liposome complex in the mouse brain after injection. This figure is adapted from Dhaliwal et al. [114].

3.4.4. Advance the translation of iPSC technology

Production of safe induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) holds great promise for the development of regenerative therapies. Choi et al. [64] utilized GO-PEI complexes for efficient mRNA delivery into adipose tissue-derived fibroblasts and successfully developed a simple RNA-based technology of iPSC production. They found that the dynamic suspension culture significantly increases the reprogramming efficiency of cells treated with GO-PEI-RNA complexes, and produced iPSCs from human or rat adipose tissue-derived fibroblasts. The GO-PEI-mediated mRNA based technology of iPSC production may be useful for the preparation of clinically safe and economically feasible iPSCs, advancing the translation of iPSC technology into the clinical settings.

4. Outlook

The synthetic mRNA undergoes transient protein expression after delivered to cytoplasm and can be completely degraded via physiological metabolic pathways, which can avoid the risk of genomic integration. This transient feature meets the need for many applications which require protein expression for only limited periods of time, such as gene editing, cell reprogramming, and some immunotherapies [115]. Different mRNA delivery system has different delivery mechanisms. Taking lipid nano delivery system for example, LNPs entrap mRNA in the core through microfluidic preparation method, and delivery mRNA to cells mainly by endocytosis, lysosomal escape pathway; however, mRNA attach inside and outside liposomes electrostatically, and delivery mRNA to cells mainly by membrane fusion. Besides lipid nano delivery systems, the other nano delivery systems also have their own mRNA entrapping strategy and delivery features, such as polymer complexes, micelles, cationic peptides, and so on. However, the synthetic mRNA-based therapeutics also suffer from some drawbacks such as inefficient delivery and instability [116]. At present, hampered by limited endosomal escape of nano delivery system, only a small amount of mRNA (0.01%) could successfully enter the cytoplasm and express the protein [117]. Therefore, high dose administration is still normal and will bring great side effects. In the nearest future, lyophilization or other pharmaceutical processing methods may help to resolve these problem and even enable nasal, oral, or respiratory administration [118]. The administration routes of mRNA nano delivery systems is very important to determine the metabolism of the mRNA vaccine in vivo and the efficiency of the translation of the target antigen protein. For example, if exposed mRNA is given intravenously without any treatment, it is rapidly degraded by nucleases in the blood. Currently, mRNA vaccines are administered systematically or locally, depending on where the antigenic protein needs to be expressed. Prophylactic vaccines are usually administered locally subcutaneously and intramuscularly to induce a strong immune response, while therapeutic mRNA vaccines are usually administered intraperitoneally or intravenously. Moreover, innovative versatile materials may be another solution to the challenge of mRNA applications.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed mRNA technologies to the world, which showed their unique advantages at the critical moment. These technologies have been developed through years of painstaking work by scientists in academia and industry. Although not perfect, it is undeniable that mRNA therapeutics are ready for its time to shine, and the transition to a full-scale industrial revolution.

Funding

The research was supported by Tianjin Natural Science General Project Fund [2018KJ124] and Open Fund of Tianjin Enterprise Key Laboratory on Hyaluronic Acid Application Research [no. KTRDHA-Y201906] provided by Tianjin Kangting Bioengineering Group Corp. Ltd.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Alboushi L., Hackett A.P., Naeli P., Bakhti M., Jafarnejad S.M. Multifaceted control of mRNA translation machinery in cancer. Cell. Signal. 2021;84:110037. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josephson K., Ricardo A., Szostak J.W. mRNA display: from basic principles to macrocycle drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today. 2014;19:388–399. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melčák I., Raška I. Structural organization of the pre-mRNA splicing commitment: a hypothesis, J. Struct. Biol. 1996;117:189–194. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner S. Replicating and reshaping DNA: a celebration of the jubilee of the double helix. Perspect. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2004;359:153–154. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitriadis G.J. Translation of rabbit globin mRNA introduced by liposomes into mouse lymphocytes. Nature. 1978;274:923–924. doi: 10.1038/274923a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostro M.J., Giacomoni D., Lavelle D., Paxton W., Dray S. Evidence for translation of rabbit globin mRNA after liposome-mediated insertion into a human cell line. Nature. 1978;274:921–923. doi: 10.1038/274921a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolgin E. The tangled history of mRNA vaccines, Nature. 2021;597:318–324. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02483-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang N.N., Li X.F., Deng Y.Q., Zhao H., Huang Y.J., Yang G., Huang W.J., Gao P., Zhou C., Zhang R.R., Guo Y., Sun S.H., Fan H., Zu S.L., Chen Q., He Q., Cao T.S., Huang X.Y., Qiu H.Y., Nie J.H., Jiang Y., Yan H.Y., Ye Q., Zhong X., Xue X.L., Zha Z.Y., Zhou D., Yang X., Wang Y.C., Ying B., Qin C.F. A thermostable mRNA vaccine against COVID-19, Cell. 2020;182:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.024. e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knudson C.J., Peixoto P.A., Muramatsu H., Stotesbury C., Tang L.J., Lin P.J.C., Tam Y.K., Weissman D., Pardi N., Sigal L.J. Lipid-nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA vaccines induce protective memory CD8 T cells against a lethal viral infection. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2769–2781. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johanning F.W., Conry R.M., LoBuglio A.F., Wright M., Sumerel L.A., Pike M.J. A Sindbis virus mRNA polynucleotide vector achieves prolonged and high level heterologous gene expression in vivo. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 1995;23:1495–1501. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diken M., Kreiter S., Selmi A., Britten C.M., Huber C., Türeci Ö. Selective uptake of naked vaccine RNA by dendritic cells is driven by micropinocytosis and abrogated upon DC maturation. Gene Ther. 2011;18:702–708. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreiter S., Selmi A., Diken M., Koslowski M., Britten C.M., Huber C. Intranodal vaccination with naked antigen-encoding RNA elicits potent prophylactic and therapeutic antitumoral immunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9031–9040. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyte J.A., Aamdal S., Dueland S., Sæbøe L.S., Inderberg E.M., Madsbu U.E. Immune response and long-term clinical outcome in advanced melanoma patients vaccinated with tumor-mRNA-transfected dendritic cells. OncoImmunology. 2016;5 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1232237. e1232237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Probst J., Weide B., Scheel B., Pichler B.J., Hoerr I., Rammensee H.G. Spontaneous cellular uptake of exogenous messenger RNA in vivo is nucleic acid-specific, saturable and ion dependent. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1175–1180. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajj K.A., Whitehead K.A. Tools for translation: non- viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017;2:17056. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W., Liu Y., Chin J.M., Phua K.K.L. Sustained release of PKR inhibitor C16 from mesoporous silica nanoparticles significantly enhances mRNA translation and anti-tumor vaccination. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021;163:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosa S.S., Prazeres D.M.F., Azevedo A.M., Marques M.P.C. mRNA vaccines manufacturing: challenges and bottlenecks. Vaccine. 2021;39:2190–2200. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarzebska N.T., Lauchli S., Iselin C., French L.E., Johansen P., Guenova E., Kündig T.M., Pascolo S. Functional differences between protamine preparations for the transfection of mRNA. Drug Deliv. 2020;27:1231–1235. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2020.1790692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coppin L., Leclerc J., Vincent A., Porchet N., Pigny P. Messenger RNA life-cycle in cancer cells: emerging role of conventional and non-conventional RNA-binding proteins? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;19:650. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li B., Zhang X.F., Dong Y.Z. Nanoscale platforms for messenger RNA delivery, Wiley. Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1002/wnan.1530. e1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowalski P.S., Rudra A., Miao L., Anderson D.G. Delivering the messenger: advances in technologies for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:710–728. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullis P.R., Hope M.J. Lipid nanoparticle systems for enabling gene therapies. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1467–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rizk M., Tuzmen S. Update on the clinical utility of an RNA interference-based treatment: focus on Patisiran. Pharmacogenomics Personalized Med. 2017;10:267–278. doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S87945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koitabashi K., Nagumo H., Nakao M., Machida T., Yoshida K., Kato K.S. Acidic pH-induced changes in lipid nanoparticle membrane packing. BBA - Biomembranes. 2021;1863:183627. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2021.183627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guimaraes P.P., Zhang R., Spektor R., Tan M., Chung A., Billingsley M.M., Mayta R.E., Riley R.S., Wang L., Wilson J.M., Mitchell M.J. Ionizable lipid nanoparticles encapsulating barcoded mRNA for accelerated in vivo delivery screening. J. Contr. Release. 2019;316:404–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horiuchi Y., Lai S.J., Yamazaki A., Nakamura A., Ohkawa R., Yano K., Kameda T., Okubo S., Shimano S., Hagihara M., Tohda S.J., Tozuka M. Validation and application of a novel cholesterol efflux assay using immobilized liposomes as a substitute for cultured cells. Atherosclerosis Suppl. 2018;32:59. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baskararaj S., Panneerselvam T., Govindaraj S., Arunachalam S., Parasuraman P., Pandian S.R.K., Sankaranarayanan M., Mohan U.P., Palanisamy P., Ravishankar V., Kunjiappan S. Formulation and characterization of folate receptor-targeted PEGylated liposome encapsulating bioactive compounds from Kappaphycus alvarezii for cancer therapy. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:136. doi: 10.1007/s13205-020-2132-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drescher S., Hoogevest P.V. The phospholipid research center: current research in phospholipids and their use in drug delivery, Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:1235. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12121235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tombácz I., Laczkó D., Shahnawaz H., Muramatsu H., Natesan A., Yadegari A., Papp T.E., Alameh M.G., Shuvaev V., Mui B.L., Tam Y.K., Muzykantov V., Pardi N., Weissman D., Parhiz H. Highly efficient CD4+ T cell targeting and genetic recombination using engineered CD4+ cell-homing mRNA-LNPs. Mol. Ther. 2021;S1525-0016:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pengnam S., Plainwong S., Patrojanasophon P., Rojanarata T., Ngawhirunpat T., Radchatawedchakoon W., Niyomtham N., Yingyongnarongkul B.E., Opanasopit P. Effect of hydrophobic tails of plier-like cationic lipids on nucleic acid delivery and intracellular trafficking. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 2020;573 doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satoa Y., Okabea N., Notea Y., Hashiba K., Maeki M., Tokeshi M., Harashima H. Hydrophobic scaffolds of pH-sensitive cationic lipids contribute to miscibility with phospholipids and improve the efficiency of delivering short interfering RNA by small-sized lipid nanoparticles. Acta. Biomater. 2020;102:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rak M., Ochałek A., Gawarecka K., Masnyk M., Chmielewski M., Chojnacki T., Swiezewska E., Madeja Z. Boost of serum resistance and storage stability in cationic polyprenyl-based lipofection by helper lipids compositions. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020;155:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2020.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jahn A., Stavis S.M., Hong J.S., Vreeland W.N., Devoe D.L., Gaitan M. vol. 4. ACS. Nano; 2010. pp. 2077–2087. (Microfluidic Mixing and the Formation of Nanoscale Lipid Vesicles). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leung A.K.K., Tam Y.Y.C., Chen S., Hafez I.M., Cullis P.R. Microfluidic mixing: a general method for encapsulating macromolecules in lipid nanoparticle systems. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:8698–8706. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b02891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H., Sung J., Chang Y., Alfeche A., Leal C. vol. 12. ACS. Nano; 2018. pp. 9196–9205. (Microfluidics Synthesis of Gene Silencing Cubosomes). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belliveau N.M., Huft J., Lin P.J., Chen S., Leung A.K., Leaver T.J., Wild A.W., Lee J.B., Taylor R.J., Tam Y.K., Hansen C.L., Cullis P.R. Microfluidic synthesis of highly potent limit-size lipid nanoparticles for in vivo delivery of siRNA. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2012;1 doi: 10.1038/mtna.2012.28. e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samaridou E., Heyes J., Lutwyche P. Lipid nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery: current perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;154-155:37–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoenmaker L., Witzigmann D., Kulkarni J.A., Verbeke R., Kersten G., Jiskoot W., Crommelin D.J.A. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: structure and stability. Int. J. Pharm. 2021;601:120586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguado I.G., Castejón J.R., Pascual M.V., Gascón A.R., Rodríguez A.D.P., Aspiazu M.Á.S. Nucleic acid delivery by solid lipid nanoparticles containing switchable lipids: plasmid DNA vs. Messenger RNA. Molecules. 2020;25:5995. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies N., Hovdal D., Edmunds N., Nordberg P., Dahlén A., Dabkowska A., Arteta M.Y., Radulescu A., Kjellman T., Höijer A., Seeliger F., Holmedal E., Andihn E., Bergenhem N., Sandinge A.S., Johansson C., Hultin L., Johansson M., Lindqvist J., Björsson L., Jing Y.J., Bartesaghi S., Lindfors L., Andersson S. Functionalized lipid nanoparticles for subcutaneous administration of mRNA to achieve systemic exposures of a therapeutic protein. Mol. Ther- Nucleic. Acids. 2021;24:369–384. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Billingsley M.M., Singh N., Ravikumar P., Zhang R., June C.H., Mitchell M.J. Ionizable lipid nanoparticle-mediated mRNA delivery for human CAR T cell engineering. Nano. Lett. 2020;20:1578–1589. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang T., Lia C.H., Wang X.X. Efficient hepatic delivery and protein expression enabled by optimized mRNA and ionizable lipid nanoparticle. Bioact. Mater. 2020;5:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roshan G., O'Hagan D.T., Roberto A., Baudner B.C. Conjugation of mannans to enhance the potency of liposome nanoparticles for the delivery of RNA vaccines. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:240. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H., Leal J., Soto M.R., Smyth H.D.C., Ghosh D. Aerosolizable lipid nanoparticles for pulmonary delivery of mRNA through design of experiments. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:1042. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M.Y., Du C.Y., Guo N., Teng Y.O., Meng X., Sun H., Li S.S., Yu P., Galons H. Composition design and medical application of liposomes. Euro. J. Med. Chem. 2019;164:640–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Du C.Y., Li S.S., Li Y., Galons H., Guo N., Teng Y.O., Zhang Y.M., Li M.Y., Yu P. F7 and topotecan co-loaded thermosensitive liposome as a nano-drug delivery system for tumor hyperthermia. Drug. Deliv. 2020;27:836–847. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2020.1772409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gkionis L., Aojula H., Harris L.K., Tirella A. Microfluidic-assisted fabrication of phosphatidylcholine-based liposomes for controlled drug delivery of chemotherapeutics. Int. J. Pharm. 2021;604:120711. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramireza R.E.R., Orth E.S., Pires C., Zawadzki S.F., Freitas R.A.D. DODAB-DOPE liposome surface coating using in-situ acrylic acid polymerization. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;330:115689. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J.B., Zhou S., Yu J., Cai W.X., Yang Y.X., Kuang X., Liu H.Z., He Z.G., Wang Y.J. Low dose shikonin and anthracyclines coloaded liposomes induce robust immunogenetic cell death for synergistic chemo-immunotherapy. J. Contr. Release. 2021;335:306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jabali S.M., Farshbaf M., Walker P.R., Hemmati S., Fatahi Y., Milani P.Z., Sarfraz M., Valizadeh H. An update on actively targeted liposomes in advanced drug delivery to glioma. Int. J. Pharmaceut. 2021;602:120645. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takata H., Shimizu T., Kawaguchi Y., Ueda H., Elsadek N.E., Ando H., Ishima Y., Ishida T. Nucleic acids delivered by PEGylated cationic liposomes in systemic lupus erythematosus-prone mice: a possible exacerbation of lupus nephritis in the presence of pre-existing anti-nucleic acid antibodies, Int. J. Pharm. (Lahore) 2021;601:120529. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michel T., Luft D., Abraham M.K., Reinhardt S., Medina M.L.S., Kurz J., Schaller M., Adali M.A., Schlensak C., Peter K., Wendel H.P., Wang X.W., Krajewski S. Cationic nanoliposomes meet mRNA: efficient delivery of modified mRNA using hemocompatible and stable vectors for therapeutic applications. Mol. Ther. - Nucl. Acids. 2017;8:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuznetsova D.A., Vasileva L.A., Gaynanova G.A., Pavlov R.V., Sapunova A.S., Voloshina A.D., Sibgatullin G.V., Samigullin D.V., Petrov K.A., Zakharova L.Y., Sinyashin O.G. Comparative study of cationic liposomes modified with triphenylphosphonium and imidazolium surfactants for mitochondrial delivery. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;330:115703. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mai Y.P., Guo Y.S., Zhao Y., Ma S.J., Hou Y.H., Yang J.H. Intranasal delivery of cationic liposome-protamine complex mRNA vaccine elicits effective anti-tumor immunity. Cell. Immunnol. 2020;354:104143. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang R., Tang L., Tian Y.M., Jia X., Hu Q.Y., Zhou B.L., Ding Z.Y., Xu H., Yang L. DP7-C-modified liposomes enhance immune responses and the antitumor effect of a neoantigen-based mRNA vaccine. J. Contr. Release. 2020;328:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang H., Zhang C.L., Yang S.P., Xiao W., Zheng Q., Song X.G. The investigation of mRNA vaccines formulated in liposomes, administrated in multiple routes against SARS-CoV-2. J. Contr. Release. 2021;335:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Solomun J.I., Cinar G., Mapfumo P., Richter F., Moek E., Hausig F., Martin L., Hoeppener S., Nischang I., Traeger A. Solely aqueous formulation of hydrophobic cationic polymers for efficient gene delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2021;593:120080. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.120080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao M., Li M., Zhang Z., Gong T., Sun X. Induction of HIV-1 gag specific immune responses by cationic micelles mediated delivery of gag mRNA. Drug Deliv. 2016;23:2596–2607. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2015.1038856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li M., Zhao M., Fu Y., Li Y., Gong T., Zhang Z. Enhanced intranasal delivery of mRNA vaccine by overcoming the nasal epithelial barrier via intra-and paracellular pathways. J. Contr. Release. 2016;228:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blakney A.K., Abdouni Y., Yilmaz G., Liu R., McKay P.F., Bouton C.R. Mannosylated poly(ethylene imine) copolymers enhance saRNA uptake and expression in human skin explants. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21:2482–2492. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vogel A.B., Lambert L., Kinnear E., Busse D., Erbar S., Reuter K.C. Self-amplifying RNA vaccines give equivalent protection against influenza to mRNA vaccines but at much lower doses. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:446–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soliman O.Y., Alameh M.G., Cresenzo G.D., Buschmann M.D., Lavertu M. Efficiency of chitosan/hyaluronan-based mRNA delivery systems in vitro: influence of composition and structure. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;109:1581–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choia H.Y., Leebe T.J., Yang G.M., Oh J., Won J., Han J., Jeong G.J., Kim J., Kim J.H., Kim B.S., Cho S.G. Efficient mRNA delivery with graphene oxide-polyethylenimine for generation of footprint-free human induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Contr. Release. 2016;235:222–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chiper M., Tounsi N., Kole R., Kichler A., Zuber G. Self-aggregating 1.8 kDa polyethylenimines with dissolution switch at endosomal acidic pH are delivery carriers for plasmid DNA, mRNA, siRNA and exon-skipping oligonucleotides. J. Contr. Release. 2017;246:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo Q.L., Zhang L., He M.M., Jiang X.H., Tian J.R., Li Q.R., Liu Z.W., Wang L.G., Sun H.T. Doxorubicin-loaded natural daptomycin micelles with enhanced targeting and anti-tumor effect in vivo. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;222:113582. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roloff A., Nelles D.A., Thompson M.P., Yeo G.W., Gianneschi N.C. Self-transfecting micellar RNA: Modulating nanoparticle cell interactions via high density display of small molecule ligands on micelle coronas. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018;29:126–135. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chan L.Y., Khung Y.L., Lin C.Y. Preparation of messenger RNA nanomicelles via non-cytotoxic PEG-polyamine nanocomplex for intracerebroventicular delivery: a proof-of-concept study in mouse models, Nanomaterials. 2019;9:67. doi: 10.3390/nano9010067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weide B., Pascolo S., Scheel B., Derhovanessian E., Pflugfelder A., Eigentler T.K. Direct injection of protamine-protected mRNA: results of a phase 1/2 vaccination trial in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 2009;32:498–507. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Udhayakumar V.K., Beuckelaer A.D., McCaffrey J., McCrudden C.M., Kirschman J.L., Vanover D. Arginine-rich peptide-based mRNA nanocomplexes efficiently instigate cytotoxic T cell immunity dependent on the amphipathic organization of the peptide. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017;6:1601412. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201601412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coolen A.L., Lacroix C., Mercier G.P., Delaune E., Monge C., Exposito J.Y. Poly(lactic acid) nanoparticles and cell-penetrating peptide potentiate mRNA-based vaccine expression in dendritic cells triggering their activation. Biomaterials. 2019;195:23–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bell G.D., Yang Y., Leung E., Krissansen G.W. mRNA transfection by a Xentryprotamine cell-penetrating peptide is enhanced by TLR antagonist E6446. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lou B., Koker S.D., Lau C.Y.J., Hennink W.E., Mastrobattista E. mRNA polyplexes with post-conjugated GALA peptides efficiently target, transfect, and activate antigen presenting cells. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019;30:461–475. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qiu Y.S., Man R.C.H., Liao Q.Y., Kung K.L.K., Chow M.Y.T., Lam J.K.W. Effective mRNA pulmonary delivery by dry powder formulation of PEGylated synthetic KL4 peptide. J. Contr. Release. 2019;314:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coolen A.L., Lacroix C., Gouy P.M., Delaune E., Monge C., Exposito J.Y., Verrier B. Poly(lactic acid) nanoparticles and cell-penetrating peptide potentiate mRNA-based vaccine expression in dendritic cells triggering their activation. Biomaterials. 2019;195:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Öhlund P., Arriaza J.G., Zusinaite E., Szurgot I., Männik A., Kraus A., Ustav M., Merits A., Esteban M., Liljeström P., Ljungberg K. DNA-launched RNA replicon vaccines induce potent anti-Ebolavirus immune responses that can be further improved by a recombinant MVA boost. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12459. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang N.N., Li X.F., Deng Y.Q., Zhao H., Huang Y.J., Yang G., Huang W.J., Gao P., Zhou C., Zhang R.R., Guo Y., Sun S.H., Fan H., Zu S.L., Chen Q., He Q., Cao T.S., Huang X.Y., Qiu H.Y., Nie J.H., Jiang Y., Yan H.Y., Ye Q., Zhong X., Xue X.L., Zha Z.Y., Zhou D., Yang X., Wang Y.C., Ying B., Qin C.F. A thermostable mRNA vaccine against COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182:1271–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nimrat K., Inderbir P., Urooj J., Harshan A., Shreya N., Mayur S.P. Tozinameran (BNT162b2) vaccine: the journey from preclinical research to clinical trials and authorization. AAPS. PharmSciTech. 2021;22:172. doi: 10.1208/s12249-021-02058-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mittal A., Verma V. Connections between biomechanics and higher infectivity: a tale of the D614G mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6:11. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00439-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;182:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Emma C.T., Laura E.R., James G.S. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike N439K variants maintain fitness while evading antibody-mediated immunity. Cell. 2021;184:1171–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.037. e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim J., Choi K.W., Lee J., Lee J., Lee S., Sun R., Kim J. Wnt/β-catenin signaling inhibitors suppress the tumor-initiating properties of a CD44+CD133+subpopulation of caco-2 cells.International. J. Biol. Sci. 2021;17:1644–1659. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.58612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meo S.A., Bukhari I.A., Akram J., Meo A.S., Klonoff D.C. COVID-19 vaccines: comparison of biological, pharmacological characteristics and adverse effects of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021;25:1663–1669. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202102_24877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nanduri S., Pilishvili T., Derado G., Soe M.M., Dollard P., Wu H., Li Q., Bagchi S., Dubendris H., Link-Gelles R., Jernigan J.A., Budnitz D., Bell J., Benin A., Shang N., Edwards J.R., Verani J.R., Schrag S.J. Effectiveness of pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among nursing home residents before and during widespread circulation of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (delta) variant - national healthcare safety network. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;34:1163–1166. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lederer K., Castaño D., Atria D.G., Oguin T.H., Wang S., Manzoni T.B., Muramatsu H., Hogan M.J., Amanat F., Cherubin P., Lundgreen K.A., Tam Y.K., Fan S., Eisenlohr L.C., Maillard I., Weissman D., Bates P., Krammer F., Sempowski G.D., Pardi N., Locci M. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines foster potent antigen-specific germinal center responses associated with neutralizing antibody, generation. Immunity. 2020;53:1281–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.11.009. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Corbett K.S., Flynn B., Foulds K.E., Francica J.R., Barnum S.B., Werner A.P., Flach B., O'Connell S., Bock K.W., Minai M. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1544–1555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosenbaum P., Tchitchek N., Joly C., Pozo A.R., Stimmer L., Langlois S., Hocini H., Gosse L., Pejoski D., Cosma A., Beignon A.S., Bosquet N.D., Levy Y., Grand R.L., Martinon F. Vaccine inoculation route modulates early immunity and consequently antigen-specific immune response. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:645210. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.645210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petsch B., Schnee M., Vogel A.B. Protective effica-cy of in vitro synthesized, specific mRNA vaccines against infl-uenza A virus infection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:1210–1216. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Armbruster N., Jasny E., Petsch B. Advances in RNA vaccines for preventive indications: a case study of A vaccine against rabies, Vaccines. 2019;7:132. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7040132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Castanha P., Marques E. A glimmer of hope: recent updates and future challenges in Zika vaccine development, Viruses. 2020;12:1371. doi: 10.3390/v12121371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lou G., Anderluzzi G., Schmidta S.T., Woods S., Gallorini S., Brazzoli M., Giusti F., Ferlenghi I., Johnson R.N., Roberts C.W., O'Hagan D.T., Baudner B.C., Perrie Y. Delivery of self-amplifying mRNA vaccines by cationic lipid nanoparticles: the impact of cationic lipid selection, J. Contr. Release. 2020;325:370–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pardi N., Hogan M.J., Porter F.W., Weissman D. mRNA vaccines - a new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:261–279. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Diamond D.J., Rosa C.L., Chiuppesi F., Contreras H., Dadwal S., Wussow F., Bautista S., Nakamura R., Zaia J.A. A fifty-year odyssey: prospects for a cytomegalovirus vaccine in transplant and congenital infection, Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2018;17:889–911. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1526085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kose N., Fox J.M., Sapparapu G., Bombardi R., Ennekoon T.R.N., Silva A.D.D., Elbashir S.M., Theisen M.A., Narayanan E.H., Ciaramella G., Himansu S., Diamond M.S., Crowe J.E. A lipid-encapsulated mRNA encoding a potently neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against chikungunya infection, Sci. Immunol. 2019;4 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw6647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Anderson A.A., Gropman A., Mons C.L., Stratakis C.A., Gandjbakhche A.H. Hemodynamics of prefrontal cortex in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency: a twin case study. Front. Neurol. 2020;11:809. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Papachristofilou A., Hipp M.M., Klinkhardt U., Früh M., Sebastian M., Weiss C., Pless M., Cathomas R., Hilbe W., Pall G., Wehler T., Alt J., Bischoff H., Geißler M., Griesinger F., Kallen K.J., Mleczek M.F., Schröder A., Scheel B., Muth A., Zippelius A. Phase Ib evaluation of a self-adjuvanted protamine formulated mRNA-based active cancer immunotherapy, BI1361849 (CV9202), combined with local radiation treatment in patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Canc. 2019;7:38. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.LaTourette P.C., II, Awasthi S., Desmond A., Pardi N., Cohen G.H., Weissman D., Friedman H.M. Protection against herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in a neonatal murine model using a trivalent nucleoside-modified mRNA in lipid nanoparticle vaccine. Vaccine. 2020;38:7409–7413. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]