Abstract

Infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has the potential to be collected in wastewater from mucus, sputum, and feces of infected individuals, raising questions about the appropriate handling and treatment of the resulting wastewater. Current evidence indicates the likelihood of waterborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission is low; nonetheless, confirming the efficacy of disinfection against SARS-CoV-2 is prudent to ensure multiple barriers of protection for infectious SARS-CoV-2 that could be present in municipal and hospital wastewater. Sodium hypochlorite (free chlorine) is widely used for pathogen control in water disinfection applications. In the current study, we investigated the inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 in DI water and municipal wastewater primary influent by sodium hypochlorite (free chlorine) addition. Our results showed rapid disinfection of SARS-CoV-2, with less than 1 mg-min/L required for >3 log10 TCID50 reduction in DI water. More than 5 mg-min/L was required for 3 log10 TCID50 reduction in primary influent, suggesting potential shielding of the virus by suspended solids. These results are consistent with expected virus inactivation by free chlorine and suggest the adequacy of free chlorine disinfection for inactivation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in water matrices.

Keywords: Wastewater, Water quality, COVID-19, Persistence, Water treatment, Disinfection, SARS-CoV-2

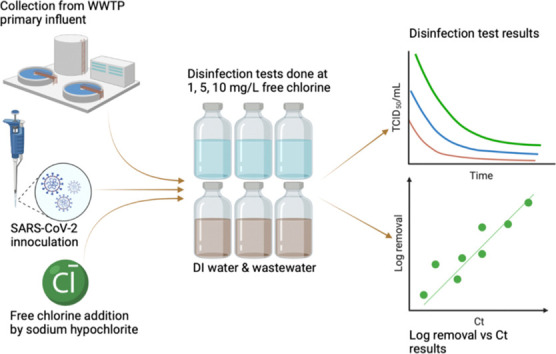

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the causative agent of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (Buonerba et al., 2021). SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, single stranded RNA virus (Buonerba et al., 2021) and infected individuals shed infectious virus in nasopharyngeal secretions (Pecson et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2021). These nasopharyngeal secretions may be collected in wastewater systems, raising concerns regarding infectious SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 RNA is common in stool samples, which has motivated global wastewater surveillance efforts to observe disease trends. While detection of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in fecal samples has been rare, these detections also contribute to potential infectious SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater (Ahmed et al., 2021; Jeong et al., 2020). Further exacerbating these concerns, the 2003 outbreak of the physiologically similar SARS-CoV had an implicated incident of wastewater exposure from faulty plumbing which caused illness in an apartment complex (Ghernaout and Elboughdiri, 2020). Some have suggested that wastewater could lead to surface, marine, or underground water SARS-CoV-2 contamination (García-Ávila et al., 2020) and aeration basins could lead to the production of bioaerosols containing SARS-CoV-2 (Buonerba et al., 2021). Efforts to detect infectious SARS-CoV-2 in environmental and wastewater samples have been unsuccessful, and critical evaluation of the evidence suggests that waterborne transmission is unlikely (Ahmed et al., 2021). Despite the evidence suggesting the low probability of waterborne SARS-CoV-2 transmission, data is necessary to confirm the efficient reduction of infectious SARS-CoV-2 in waste streams to reassure both the public and wastewater treatment workforce, and reinforce the efficacy of the ‘multiple barrier’ approach to pathogen exposure in the environment (Wigginton and Boehm, 2020). For example, disinfection of wastewater from hospital isolation wards has previously been applied to mitigate concerns regarding potential waterborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (Zhang et al., 2020).

Free chlorine is a commonly used wastewater disinfectant due to its wide availability, proven track record, effectiveness to inactivate microorganisms, and the production of a chlorine residual (EPA, 2007). Free chlorine is also used to treat wastewater on-site in hospital settings (Gautam et al., 2007). While SARS-CoV-2 disinfection by free chlorine has yet to be evaluated, the disinfection kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 have been studied using UV radiation and thermal inactivation. SARS-CoV-2 disinfection has also been studied on different surfaces using household bleach and ethanol, among other disinfectants (Chin et al., 2020). Overall, current evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 disinfection is in line with expectations for an enveloped virus with an RNA genome. Since the lipid envelope is susceptible to disruption via disinfection methods, SARS-CoV-2 is expected to have a higher sensitivity than the non-enveloped viruses that are a typically problematic for water systems (Pecson et al., 2020). For example, disinfection by UV radiation was extremely efficient, producing a three log10 inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 at 254 nm and 6.556 mJ/cm2, in 2.98 s (Lizasoain et al., 2018; Gibson et al., 2017; Sabino et al., 2020). Thermal inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 spiked in raw wastewater was also efficient, exhibiting a two log10 reduction of SARS-CoV-2 in 2 min at 70 °C (Bivins et al., 2020). Disinfection kinetic experiments using monochloramine and chlorine dioxide have primarily been conducted on surrogate viruses which have similar morphological structures to SARS-CoV-2, such as murine hepatitis virus, and human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 and these experiments have also shown efficient reduction of viruses (Silverman and Boehm, 2020). A current study from a Wuchang Cabin Hospital showed that heavy sodium hypochlorite concentrations and a 1.5 h contact time was needed to remove all SARS-CoV-2 RNA, however this study did not distinguish between infectious and non-infectious RNA which would skew the dosage and contact time (Zhang et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is known to be in wastewater in different forms; protected RNA implying an intact viral capsid and non-protected RNA (Wurtzer et al., 2021). Current evidence demonstrates that enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 are more susceptible to oxidative disinfectants than non-enveloped viruses; however, data is necessary to confirm this assumption and demonstrate the adequacy of current water and wastewater treatment methodologies (Silverman and Boehm, 2020).

The goal of this study was to examine the disinfection characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater with free chlorine. Chlorine residual was first assessed in the test matrices to enable disinfectant exposure calculations, followed by experimental disinfection of infectious SARS-CoV-2 spiked into these matrices. These results were then compared to previously reported viral disinfection requirements.

2. Materials and methods

Wastewater samples were collected from a municipal wastewater treatment plant in northern Indiana, United States then shipped frozen overnight to Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) where they were stored at −80 °C until used as previously described (Bibby et al., 2017). All experiments involving infectious SARS-CoV-2 were performed at RML under BSL4 conditions. SARS-CoV-2: hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021, B.1.351, Beta lineage was propagated in VeroE6 cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich, St, Louis, MO) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. All experiments were completed in triplicate at 20 °C. SARS-CoV-2 virus titration and cultivation were performed as previously described to evaluate disinfection of Ebola virus in wastewater (Bibby et al., 2017). The limit of detection for all replicates was 0.50 log median tissue culture infectious dose per milliliter (TCID50/mL). TCID50 is an endpoint culture dilution series that is used to determine at what dilution 50% of the infected wells produce cell death.

For disinfection experiments, stock virus was diluted 100× in wastewater or DI water and 1 mL was added to the top row of a 1 mL 96-well plate. The ‘time zero’ sample was taken prior to the addition of chlorine to obtain the initial virus concentration in the sample. Sodium hypochlorite (Acros Organics, Fair Lawn, NJ) was added to obtain an initial dose of 0, 1, 5, or 10 mg/L in triplicate. At the 0, 1, 5-, 10-, 30-, and 60-minute time points, 100 μL samples were added to 100 μL of sodium thiosulfate solution to quench remaining free chlorine. The resulting solution was triturated and 100 μL transferred to 400 μL of DMEM supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin resulting in a 1:10 dilution of the original sample. The 1:10 dilution was the starting concentration of the titrations. Titrations were carried out on VeroE6 cells in 96-well plates as a 10× dilution series using four columns for each sample. The plates were read five days after inoculation and the TCID50 calculated using the Spearman Karber method adjusted for the 1:10 initial dilution (Hierholzer and Killington, 1996).

Wastewater physiochemical characteristics and chlorine residuals experiments were done at the University of Notre Dame. Wastewater physiochemical characteristics are summarized in Table S1. For the chlorine residuals experiment, DMEM was diluted 100× in DI water and wastewater to simulate viral spiking, then the free chlorine concentration was determined outside of the Biosafety Level 4 (BSL 4) facility using a Hach Free Chlorine test kit (Method 10069) (HACH, 2014). The free chlorine concentration was then plotted versus time for each initial chlorine dose and matrix combination. Chlorine decay was then modeled using the below first-order decay equation (Eq. (1)) as previously described (Bibby et al., 2017).

| (1) |

where Ct is the concentration of free chlorine at any time point, C0 is the concentration of free chlorine at time zero, t is time and k is the free chlorine decay rate. The concentration-time (Ct) (Chick, 1908) exposure was then calculated for each sampling time point by integrating the area under the modeled chlorine residual curve at each time point. Graphing and statistical analysis were done using PRISM 9.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

3. Results and discussion

Using results from the chlorine residual tests, concentration-time (Ct) values were calculated and plotted on an observed log removal vs Ct graph (Fig. S1). Observed log removal was calculated by subtracting data points for the 1, 5, and 10 mg/L chlorine conditions from the data points for the 0 mg/L chlorine condition. Chlorine residual was dose dependent as previously observed (Bibby et al., 2017), and modeling of immediate chlorine demand determined that 1, 5, and 10 mg/L doses resulted in initial free chlorine residuals of 0, 0.16, and 0.31 mg/L in wastewater, respectively, and 0, 0.16, and 0.43 mg/L in DI water, respectively. This initial high free chlorine consumption observed is due to the DMEM (viral media) that was spiked in DI water and wastewater for both the disinfection and chlorine residuals experiments.

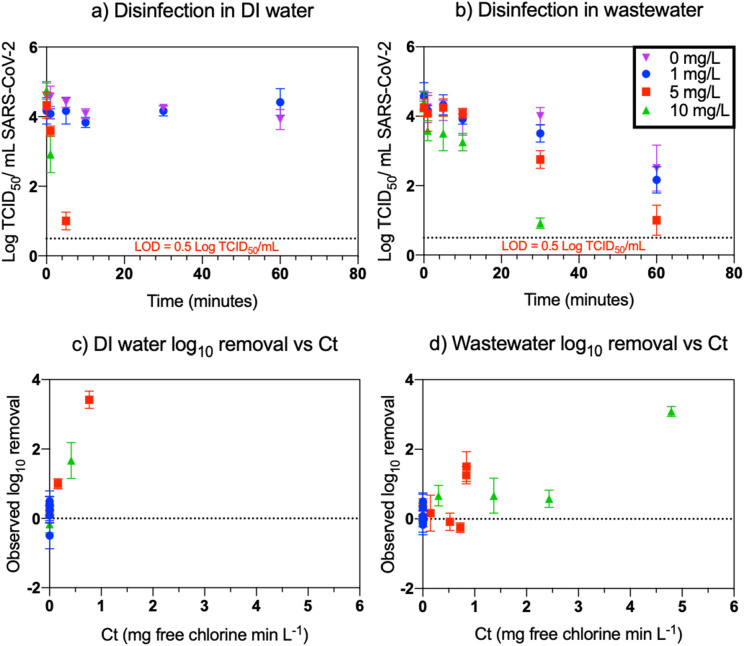

Disinfection results of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater and DI water are displayed in Fig. 1 (panels a & b). No decay of virus was observed at 0 and 1 mg/L chlorine conditions in DI water for the duration of the experiment (1 h). For the 5 and 10 mg/L chlorine conditions in DI water, infectious SARS-CoV-2 was detected up to 5 min and 1 min, respectively. Two log10 SARS-CoV-2 decay was observed over the study period (1 h) at the 0 mg/L chlorine condition in wastewater. For the 10 mg/L chlorine condition in wastewater, SARS-CoV-2 was detected for 30 min whereas for the 1 and 5 mg/L chlorine conditions in wastewater, infectious SARS-CoV-2 was detected for the entire duration of the experiment.

Fig. 1.

Disinfection for SARS-CoV-2 at initial chlorine doses of 1 (blue), 5 (red), and 10 mg/L (green). Observed disinfection of SARS-CoV-2 in DI water (a) and wastewater (b). Disinfection experiments included an initial chlorine dose of 0 mg/L (purple) as a control. The limit of detection was 0.5 TCID50/mL. Bottom figures show virus log removal versus chlorine concentration-time (Ct) values in DI water (c) and wastewater (d). Each point represents the average of triplicate values and error bars represent standard deviations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Ct values were then determined by integrating the area under the chlorine residual curve at each sampling time point. The area under the chlorine residual curve was not calculated for the 1 mg/L condition in wastewater and DI water because there was a limited number of points. Therefore, the Ct was assumed to be zero for the 1 mg/L condition. Observed viral inactivation versus calculated Ct is shown in Fig. 1 (panels c & d). Less than 1 mg-min/L was required for a three log10 reduction of SARS-CoV-2 in DI water. Over 5 mg-min/L was required for a three log10 reduction in wastewater (accounting for the background two log10 reduction observed without addition of any chlorine).

Higher Ct values were needed to disinfect SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater than in DI water. While we assessed the effective Ct values in both matrices, this lower removal efficiency in wastewater is possibly due to the higher background chlorine demand of the wastewater matrix compared with the DI water matrix. As free chlorine reacts with the different components of wastewater, such as organic matter or other microorganisms, less free chlorine is available to react with SARS-CoV-2 leading to longer persistence of infectious virus in wastewater than in DI water (Ye et al., 2016). Wastewater also contains particles that SARS-CoV-2 may adsorb to; indeed, prior research has demonstrated that enveloped viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 preferentially adhere to solids in wastewater (Ye et al., 2016). These larger particles may shield SARS-CoV-2 from free chlorine disinfection allowing SARS-CoV-2 to persist longer (Grünwald et al., 2002).

Table 1 summarizes the Ct values required to achieve three log10 reduction of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses in DI water. The Ct value determined for SARS-CoV-2 for this experiment is lower than the Ct values of other viruses under similar conditions. In addition to the data provided in this study, SARS-CoV, which is closely related to SARS-CoV-2, is also highly susceptible to chlorine disinfection; however, the results of the study did not allow for exact Ct calculations (Silverman and Boehm, 2020; Wang et al., 2005). This work adds to a growing body of evidence that the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 waterborne transmission is low, and existing water infrastructure is adequate for public and worker safety.

Table 1.

Three log10 (99.9%) inactivation Ct values for various enveloped and non-enveloped viruses with free chlorine disinfection in deionized water.

| Virus | Enveloped/non-enveloped | Method of measurement | 3-log10 Ct (mg min/Liter) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | Enveloped | TCID50/ml | <1.0a | This study |

| Human Rotavirus | Non-enveloped | TCID50/ml | 1.35 to 2.35 | (Xue et al., 2013) |

| Coxsackievirus B5 | Non-enveloped | PFU/ml | 7.6 | (Cromeans et al., 2010) |

| Echovirus E1 | Non-enveloped | PFU/ml | 1.3 | (Cromeans et al., 2010) |

| Echovirus E12 | Non-enveloped | PFU/ml | 4.23 | (Rachmadi et al., 2020) |

| H5N1 | Enveloped | TCID50/ml | 1.08 | (Rice et al., 2007) |

| Poliovirus 1 | Enveloped | PFU/ml | 3.0 | (Black et al., 2009) |

Fig. 1 (panel c).

The study goals were limited due to the constraints of working with infectious SARS-CoV-2 in a containment laboratory. For instance, we could not perform the multiple replicates needed to develop more complicated Ct model fits, hence, the main goal of our study was limited to demonstrating that chlorine disinfection was adequate at treating the virus in water and wastewater. Another primary limitation of this study is the use of wastewater samples collected from only one wastewater treatment plant on a single day and time. Because there was only a single set of water quality parameters that were measured, differing environmental factors that can affect wastewater and disinfection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater could not be examined. Furthermore, spiking in exogenous virus at higher titers may have led to viral behavior deviating from the behavior of endogenous viruses in real world scenarios. Future experiments should incorporate more wastewater sample replicates along with cell cultures with lower limits of detection so to accurately model disinfection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater and water.

4. Conclusions

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater has raised concerns about the potential for waterborne wastewater associated transmission of the virus (Jeong et al., 2020; García-Ávila et al., 2020; Silverman and Boehm, 2020). This has led to concerns regarding the fate and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. SARS-CoV-2 was efficiently disinfected by free chlorine in both DI water and wastewater, and the determined Ct value is less than that of other waterborne viruses of interest. Disinfection was also more rapid in DI water than in wastewater. This is expected as wastewater contains high concentrations of organic matter that could consume this disinfectant. Rapid disinfection in DI water compared to wastewater could also suggest that particle association may be an important consideration for wastewater disinfection. Ultimately, our study showed that free chlorine disinfection is an effective method at reducing SARS-CoV-2 levels in DI water and wastewater.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Justin Greaves: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Robert J. Fischer: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Marlee Shaffer: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Aaron Bivins: Writing – review & editing. Myndi Holbrook: Investigation. Vincent J. Munster: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Kyle Bibby: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Isolate hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP01542/2021 was obtained from Andrew Pekosz, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1ZIAAI001179-01), and the Water Research Foundation.

Editor: Warish Ahmed

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150766.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmed W., et al. Differentiating between the possibility and probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission associated with wastewater: empirical evidence is needed to substantiate risk. FEMS Microbes. 2021;2 doi: 10.1093/femsmc/xtab007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibby K., et al. Disinfection of ebola virus in sterilized municipal wastewater. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivins A., et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:937–942. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S., Thurston J.A., Gerba C.P. Determination of ct values for chlorine of resistant enteroviruses. 2009;44:336–339. doi: 10.1080/10934520802659653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonerba A., et al. Coronavirus in water media: analysis, fate, disinfection and epidemiological applications. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;415 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chick H. An investigation of the Laws of disinfection. J. Hyg. (Lond) 1908;8:92–158. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400006987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.W.H., et al. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromeans T.L., Kahler A.M., Hill V.R. Inactivation of adenoviruses, enteroviruses, and murine norovirus in water by free chlorine and monochloramine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:1028–1033. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01342-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA . 2007. Effectiveness of disinfectant residuals in the distribution system. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ávila F., et al. Considerations on water quality and the use of chlorine in times of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in the community. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2020.100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam A.K., Kumar S., Sabumon P.C. Preliminary study of physico-chemical treatment options for hospital wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2007;83:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghernaout D., Elboughdiri N. Environmental engineering for stopping viruses pandemics. OALib. 2020;07:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson J., Drake J., Karney B. UV Disinfection of Wastewater and Combined Sewer Overflows. 2017. pp. 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünwald A., Šťastný B., Slavíčková K., Slavíček M. Formation of haloforms during chlorination of natural waters. Acta Polytech. 2002;42 [Google Scholar]

- HACH . 2014. Method 10069: Chlorine, Free, DPD Method. doi:DOC316.53.01025. [Google Scholar]

- Hierholzer J.C., Killington R.A. Academic Press; 1996. Virology Methods Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H.W., et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in various specimens from COVID-19 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26:1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizasoain A., et al. Human enteric viruses in a wastewater treatment plant: evaluation of activated sludge combined with UV disinfection process reveals different removal performances for viruses with different features. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;66:215–221. doi: 10.1111/lam.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecson B., et al. Editorial perspectives: will SARS-CoV-2 reset public health requirements in the water industry? Integrating lessons of the past and emerging research. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2020;6:1761–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmadi A.T., et al. Required chlorination doses to fulfill the credit value for disinfection of enteric viruses in water: a critical review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:2068–2077. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice E.W., et al. Chlorine inactivation of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:1568–1570. doi: 10.3201/eid1310.070323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino C.P., et al. UV-C (254 nm) lethal doses for SARS-CoV-2. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020;32 doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman A.I., Boehm A.B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the persistence and disinfection of human coronaviruses and their viral surrogates in water and wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020;7:544–553. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-W., et al. Study on the resistance of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;126:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigginton K.R., Boehm A.B. Environmental engineers and scientists have important roles to play in stemming outbreaks and pandemics caused by enveloped viruses. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:3736–3739. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c01476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtzer S., et al. Several forms of SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be detected in wastewaters: implication for wastewater-based epidemiology and risk assessment. Water Res. 2021;198 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., et al. Effects of chlorine and chlorine dioxide on human rotavirus infectivity and genome stability. Water Res. 2013;47:3329–3338. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Ellenberg R.M., Graham K.E., Wigginton K.R. Survivability, partitioning, and recovery of enveloped viruses in untreated municipal wastewater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:5077–5085. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., et al. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang hospital. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material