Abstract

Background

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often the first drug of choice in the treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE), and in Denmark 8 weeks of high‐dose PPI therapy is recommended as first‐line treatment followed by rebiopsying, reflecting international recommendations.

Aims

To assess the population‐based effectiveness of PPIs in the treatment of EoE and evaluate whether patients were treated and followed according to the regional guideline.

Methods

This is a retrospective, registry‐based, DanEoE cohort study of 236 adult EoE patients diagnosed between 2007 and 2017 in the North Denmark Region. After patient file revision, the EoE diagnosis was defined according to the AGREE 2 consensus. Symptomatic PPI response was defined as complete symptom resolution and histological remission (<15 eosinophils per high‐power field).

Results

PPI treatment was initiated in 92% of the EoE patients. High‐ and low‐dose PPIs were prescribed in 55% and 45% of the cases, respectively. When treated with high‐dose PPIs, 68% of the patients were completely symptom‐free, and 49% were in histological remission. In 39% of high‐dose PPI‐treated patients, the symptomatic and histological responses were conflicting. While treated with PPIs, complications were rare, with <5% strictures in responders and <10% in non‐responders. Rebiopsying was done in 67% of the EoE patients started on PPIs.

Conclusions

High‐dose PPI treatment was effective in half of the EoE patients started on PPIs, but conflicting symptomatic and histological PPI responses were common. Complications were rare when PPIs were started. One‐third of the patients were not rebiopsied as recommended.

Keywords: complications, eosinophilic oesophagitis, oesophagus, proton pump inhibitors, treatment

Key summary.

Established knowledge

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a clinicopathological condition characterized by symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction and oesophageal eosinophilia

The incidence of EoE has increased rapidly over the last decade

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often the first drug of choice in the treatment of EoE

PPI therapy can induce clinical and histological remission in patients with EoE, but the reported effectiveness varies widely

New or significant findings

-

5.

High‐dose PPI therapy induced complete symptom resolution in 68% and histological remission in 49% of the EoE patients in this register‐based study

-

6.

Stricture formation was rarely seen in EoE patients treated with PPI therapy

-

7.

Conflicting symptomatic and histological PPI responses were seen in almost 40% of the treated EoE patients, supporting the importance of biopsying all patients with dysphagia, regardless of the macroscopic findings, to ensure the right treatment

-

8.

One‐third of the EoE patients treated with PPIs were not rebiopsied as recommended by the EoE guideline, indicating a continued lack of EoE awareness

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE) is a clinicopathological condition characterized by symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction and histologically by ≥ 15 eosinophils per high‐power field (eos/hpf). 1 , 2 The diagnosis of EoE has been developing since the first consensus in 2007 to the last definition published in 2018. 1 , 3 , 4 EoE has become increasingly recognized over the last decade, and the incidence is increasing rapidly in the Western world, now matching that of Crohn's disease. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 EoE is associated with low quality of life, and the development of strictures can be seen if untreated. 4 , 9 EoE is often easy to treat with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), dietary elimination, topical corticosteroids or oesophageal dilation. 4 , 10 PPIs are often the first drug of choice because they are inexpensive, easy to administrate, have minimal side effects and have shown to have some acid‐independent anti‐inflammatory properties. 4 , 11 , 12 It is already known that PPI therapy can induce clinical and histological remission in patients with EoE, but the reported effectiveness varies widely. 4 , 13 , 14 , 15 Currently, 8 weeks of high‐dose PPI therapy is recommended, but a recent study has shown that a longer duration of treatment up to 12 weeks may have a beneficial effect. 15 Follow‐up assessment, including rebiopsying, is important because symptomatic and histological remissions are not always in agreement. High‐dose PPI therapy and mandatory rebiopsy after 8 weeks were introduced in 2011 in the North Denmark Region guideline. The regional guideline endorsed sampling of at least 8 biopsies in all patients with oesophageal dysphagia regardless of the macroscopic findings, and the incidence of EoE increased 50‐fold in the first year after implementation of the guideline. 16 , 17 The DanEoE cohort was implemented to evaluate whether the diagnostic process and treatment of EoE patients were according to the guideline. The DanEoE cohort is a regional, population‐ and registry‐based cohort of EoE patients diagnosed between 2007 and 2017, with follow‐up to 31 December 2018. This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of PPI treatment in a population‐based setting and evaluate whether patients in the North Denmark Region were offered treatment and follow‐up according to the regional guideline, reflecting national and international recommendations. 4 , 12

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study database was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency via the Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, with ID number 2018‐59. The Regional Ethics Committee evaluated the project as not needing ethical approval within Danish law.

Study population

The study was a retrospective, cohort study using the DanEoE database previously described. 16 DanEoE is a registry‐based database built on the Danish Patho‐histology registry using the SNOMED system. 16 Since 1997, all biopsies obtained in Denmark have been registered in the national pathology database using ‘SNOMED’ codes for topography and morphology. 18 Via the unique personal identification number assigned to all Danish citizens, all individuals in a region having oesophageal eosinophilia could be found. The personal identification number is linked to all medical information and all registries in Denmark, giving ideal possibilities for population‐based studies. 19 , 20 Patients having at least one biopsy coded with both the SNOMED code for oesophagus mucosa (T62010) and inflammation with eosinophilia defined as 15+ eosinophils in one high‐power field (hpf) (M47150) were included in the DanEoE database; details were published previously. 16 Included in DanEoE are all patients with oesophageal eosinophilia in the North Denmark Region diagnosed between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2017, with follow‐up to 31December 2018. Of the 308 DanEoE patients, 76% (236) have EoE (55% purely EoE and 21% EoE + gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease [GORD]) and 18% (54) have GORD with eosinophilia but not EoE. The remaining patients had other reasons for eosinophilia and were excluded (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

In the DanEoE cohort all patients with oesophageal eosinophilia in the North Denmark Region diagnosed between 2007 and 2017 were included. Of the 308 DanEoE patients, 236 had EoE and 54 had GORD with eosinophilia but not EoE. Almost all patients with EoE were treated with a PPI. Symptomatic follow‐up 8 weeks after initiation of PPI therapy was more often done than histological assessment. EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor

For the current study, all patient files, radiology reports, histology reports, medication history and referral documents were reviewed in detail by a gastroenterologist or gastroenterologist in training. All patients were manually checked by author ALK for correct placement in groups as described below. Collecting of data was possible via the unique personal identification number. 19 , 20

Patient groups

Eosinophilic oesophagitis

The EoE group was defined as patients fulfilling the international diagnostic criteria for EoE according to the AGREE 2 consensus. 21 The EoE patients had symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction for example, dysphagia without stenosis or stenosis not described as peptic and eosinophilic inflammation in at least one oesophageal biopsy. Eosinophilic infiltration should be isolated to the oesophagus, otherwise the patient was excluded. The diagnosis was supported by concomitant atopic conditions, and endoscopic findings typical of EoE for example, rings, furrows, exudates, oedema, strictures, narrowings, and crepe‐paper.

The EoE group was sub‐grouped according to whether they had comorbid GORD (EoE + GORD) or not (pure EoE).

Gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease

GORD was defined according to the Montreal consensus. 22 Patients were allocated to the GORD group if they presented with symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) or objective findings of GORD and did not have the EoE phenotype despite oesophageal eosinophilia.

Further classification of this subgroup can be found in a recently published study. 17 Barrett's oesophagus was defined as intestinal metaplasia in salmon‐coloured oesophageal mucosa. 23 Oesophagitis was defined according to the Los Angeles (LA) classification and grouped into mild (LA‐grade A + B) or moderate to severe (LA grade C + D). When the endoscopist did not use the LA classification, the description in the patient file was used by the author to grade the severity when possible. 24

Types of PPI response

Symptomatic PPI response was defined as complete symptom resolution written in the medical record. Histological remission was defined as <15 eos/hpf. Patients were divided into four types of PPI responses depending on response pattern: (1) PPI responders, (2) PPI non‐responders, (3) Inflamed and asymptomatic, and (4) Symptomatic and non‐inflamed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Types of responses to PPI treatment defined by symptoms and histology

| Compatible PPI responses | Conflicting PPI responses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Responders | Non‐responders | Inflamed and asymptomatic | Symptomatic and non‐inflamed |

| Histologic remission <15 eos/hpf | ≥15 eos/hpf | ≥15 eos/hpf | Histologic remission <15 eos/hpf |

| No symptoms | Symptomatic | No symptoms | Symptomatic |

Abbreviation: PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Guidelines during the study period

In Denmark, the first EoE guideline was the regional guideline for the North Denmark Region published in 2011. 16 The first national EoE guideline was published in 2015, but already in 2014 the regional guideline in the North Denmark Region was updated to reflect the current change in treatment of EoE. From 2011 to 2014 the regional guideline recommended first‐line treatment to be pantoprazole 40 mg daily (no other PPIs mentioned), and this was changed in 2014 to pantoprazole 40 mg twice a day. In the national guideline from 2015, PPIs in standard doses twice a day was recommended. In the current study, high‐dose PPI treatment was defined as a dose equal to or above the following: pantoprazole 80 mg per day, lansoprazole 60 mg per day, omeprazole 40 mg per day, esomeprazole 40 mg per day or rabeprazole 40 mg per day. Low‐dose PPI therapy was defined as less than the above mentioned.

STATISTICS

Descriptive statistics were given as median and range (25–75 percentile [IQR]) for continuous variables or mean (standard deviation [SD]) as appropriate. For categorical variables, counts and percentages were displayed. Comparing the three groups of (1) pure EoE, (2) EoE + GORD, with the (3) GORD group, was done by one‐ or two‐way ANOVAs, and results were given as mean and 95% confidence interval. Comparison of proportion between groups was done using the Chi2 test. The data management and statistics were done using SAS enterprise guide 71 (SAS Institute Inc.) and figures using SigmaPlot 11.0 Build 11.1.0.102 (Systat Software Inc.).

RESULTS

PPI treatment was initiated in most patients with oesophageal eosinophilia

The PPI treatment and follow‐up patterns in patients with either EoE or GORD with oesophageal eosinophilia are specified in Table 2, the flowchart in Figure 1, and Table S2. For subgroups of EoE patients see Tables S1 and S3.

TABLE 2.

PPI effectiveness according to PPI doses in patients with EoE in the population‐based DanEoE cohort

| Patient group | EoE | |

|---|---|---|

| PPI dose | High dose | Low dose |

| % of PPI‐treated patients, n | 55%, n 118 | 45%, n 98 |

| Delay from diagnose to when PPI was started, if not started before the index endoscopy, mean (SD) | 43 (103) days | 66 (153) days |

| PPI duration before assessment of symptoms ± histology | ||

| Information of duration available, n | 75%, n 88 | 54%, n 53 |

| Weeks, mean (SD) | 26 (52) | 44 (63) |

| Weeks, median (IQR) | 11 (8.4; 18) | 17 (12; 37) |

| Symptomatic efficacy on PPI % of those assessed, number | ||

| Symptoms assessed after PPI therapy | 94%, n 111 | 83%, n 81 |

| Symptom reduction, any | 86%, n 96 | 75%, n 61 |

| Completely asymptomatic | 68%, n 76 | 44%, n 36 |

| No effect | 14%, n 15 | 25%, n 20 |

| Histological efficacy on PPI in % of those assessed, number | ||

| Rebiopsied on PPI | 73%, n 86 | 53%, n 52 |

| <15 eos/hpf | 49%, n 42 | 33%, n 17 |

| Still inflamed | 30%, n 26 | 44%, n 23 |

Abbreviations: EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; Eos, eosinophilic granulocytes; GORD, gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease; Hpf, high‐power field; IQR, interquartile range; N, number; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SD, standard deviation.

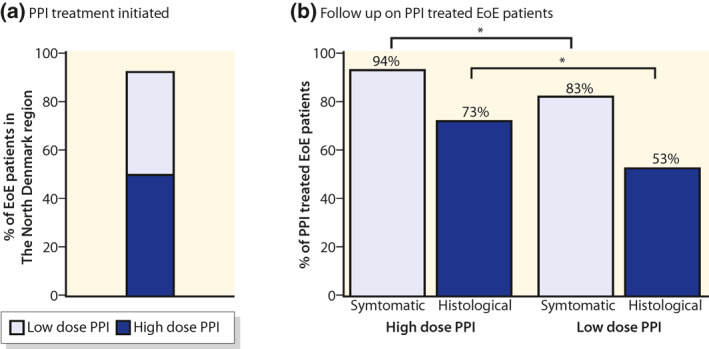

Of the 236 EoE and 54 GORD patients with oesophageal eosinophilia 92% of EoE, and 91% of GORD patients were treated with a PPI. High‐dose PPI therapy was chosen for 55% of the EoE patients started on treatment (Figure 2a). Pantoprazole was used in 85% of cases, omeprazole in 13%, lansoprazole in 1.4%, esomeprazole in 1.4% and rabeprazole was not used. The delay from the index endoscopy to initiation of PPI treatment was 43 (103) to 66 (153) days for high‐ and low‐dose PPIs, respectively. The delay corresponds well with histology reports arriving about 4–6 weeks after the endoscopy and some delay from the clinician to the start treatment (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Almost all patients with EoE in the North Denmark Region were treated with a PPI (a). The regional guideline specified that EoE should be treated with high‐dose PPI therapy and the efficacy should be evaluated after 8 weeks both symptomatic and histological. Patients treated with a high‐dose PPI was more often evaluated according to the guideline (b). EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor

High‐dose versus low‐dose PPI effectiveness in EoE patients

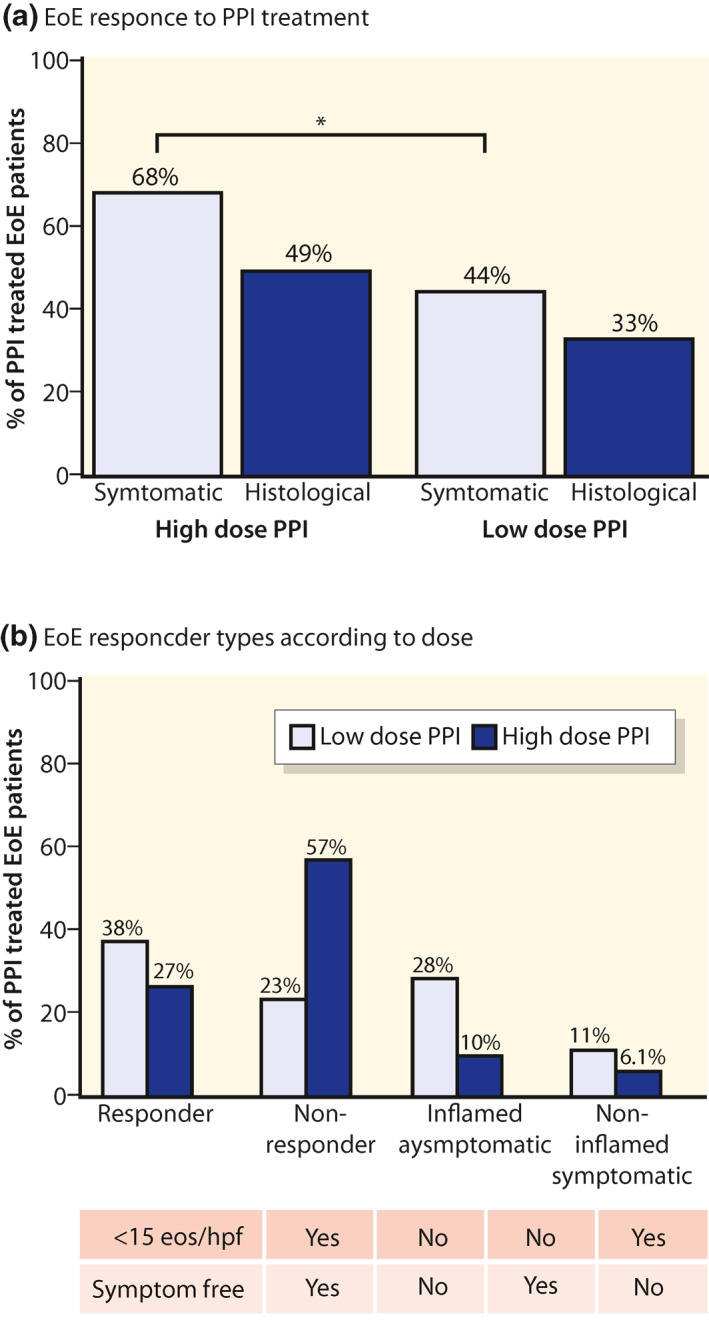

The regional guideline recommended both symptomatic and histological follow‐up 8 weeks after initiation of PPI therapy. If the patient was treated with a high‐dose PPI, the follow‐up was more often in accordance with the regional guideline (Figure 2b). The patients receiving a high‐dose PPI started earlier on PPI treatment when the diagnosis was established (Table 2). The symptomatic effectiveness in high‐dose PPI therapy was higher compared to low‐dose PPI (68% vs. 44%, p < 0.001), and histologically, the difference was borderline significant (49% vs. 33%, p = 0.06) (Figure 3a). Treatment of GORD patients with eosinophilia with high‐dose PPIs showed the same treatment pattern compared to low‐dose PPIs, but the PPI response was much less pronounced (Table S2). Both clinical and histological remission was seen in 38% and 27% of the EoE patients for, respectively, high‐ and low‐dose PPI therapy (Figure 3b). Data for EoE subgroups are shown in Table S3.

FIGURE 3.

On high‐dose PPI histological remission was induced in half of EoE patients and in one of three on low‐dose PPI (a, grey boxes). Compatible symptomatic and histological responses were observed in 61% of high‐dose PPI‐treated patients (38% Responders and 23% Non‐responders [b]. Although 68% of patients on high‐dose PPI were completely asymptomatic, only 49% were in histological remission (b). EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor

PPI responses in EoE patients: The compatible and conflicting responses

Compatible symptomatic and histological responses were observed in 61% of high‐dose PPI‐treated patients (38% responders and 23% non‐responders) shown in Figure 3b. When treated with high‐dose PPIs, 68% of the EoE patients were completely asymptomatic and 49% were in histological remission (Figure 3a). Conflicting PPI responses were very common, especially in high‐dose treated patients. Twenty‐eight percent of EoE patients on high‐dose PPIs had complete symptom resolution but were still inflammatory active with more than 15 eos/hpf (Figure 3b). The opposites were the patients having dysphagia despite being in complete histological remission and having no stenosis. This group constituted 11% of the EoE patients treated with high‐dose PPI therapy (Figure 3b). Conflicting PPI responses were not as common when treating with low‐dose PPI therapy (Figure 3b).

Endoscopic changes and complication rate on PPI in EoE patients

When EoE patients were rebiopsied after PPI initiation, 34% of endoscopists described a normal oesophagus in inflamed patients (Table 3). Macroscopic EoE signs were described in 29% of patients in histological remission. Rings were observed in 19% of EoE patients in histological remission and 22% in inflamed patients (Table 3). In EoE patients in histological remission, food bolus obstruction was observed in 3.4% and strictures in 3.4%. In EoE patients who were still inflamed with ≥15 eos/hpf, food bolus obstruction was observed in 2.5% and strictures in 3.8% (Table 3). Of the hiatal hernias described at the index endoscopy 33% had disappeared when the follow‐up endoscopy was described, whereas 3% more had new hiatal hernias diagnosed. Sedation at the follow‐up endoscopy was given to 21% of EoE patients and 7.1% of GORD patients. While treated with a PPI, both high‐ and low‐dose, complications were rarely seen in EoE patients and not observed in any GORD patient (Table 3). The mean observation time on PPI treatment was 207 (110) weeks, approximately 4 years. If PPI effectiveness on complications were divided accordingly to both symptomatic and histological response instead of histological only, the picture changes (Figure 4a,b). In particular, stricture formations were rarely seen in asymptomatic patients regardless of the histological outcome. Complications were more often seen in non‐responders compared to responders (Figure 4a).

TABLE 3.

After PPI treatment, the endoscopic findings showed a large overlap between EoE patients with histological remission and inflamed patients

| Patient type | EoE | |

|---|---|---|

| Histological response | Remission | ≥15 eos/hpf |

| Macroscopic normal | 46%, n 27 | 34%, n 27 |

| Any macroscopic EoE signs | 29%, n 17 | 46%, n 37 |

| Rings | 19%, n 11 | 22%, n 17 |

| Previous rings disappearing on PPI | 8.5%, n 5 | 15%, n 12 |

| Strictures | 3.4%, n 1 | 3.8%, n 3 |

| Scope passable | 0.0%, n 0 | 3.8%, n 3 |

| Not passable | 3.4%, n 1 | 0.0%, n 0 |

| Food bolus present | 3.4%, n 1 | 2.5%, n 2 |

| Oesophagitis in total | 6.8%, n 2 | 1.3%, n 1 |

| LA A–B | 6.8%, n 2 | 1.3%, n 1 |

| LA C–D | 0.0%, n 0 | 0.0%, n 0 |

Note: Data includes patients treated with high‐ or low‐dose PPI.

Abbreviations: EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; Eos, eosinophilic granulocytes; GORD, gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease; Hpf, high‐power field; LA, Los Angeles; N, number; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

FIGURE 4.

PPI effectiveness on complications divided accordingly to both symptomatic and histological response instead of histological only. Particularly stricture formations were rarely seen in asymptomatic patients regardless of histological outcome. Complications were more often seen in non‐responders compared to responders (a). This was also observed in patients on high‐dose only (b). EoE, eosinophilic oesophagitis; PPI, proton pump inhibitor

Guideline adherence

In this study, 8% of the EoE patients were never started on PPI therapy, and 45% of the EoE patients treated with PPIs were not started on high‐dose PPI therapy (Table 2). From 2011 to 2014, the regional guideline recommended pantoprazole 40 mg daily. In 2015, the first national EoE guideline was published, and high‐dose PPI therapy was now recommended for example, pantoprazole 40 mg twice a day. Before the implementation of the national guideline, 35% of the EoE patients were treated with high‐dose PPI compared to 86% after the implementation. Symptomatic follow‐up 8 weeks after initiation of PPI therapy was more often done than histological assessment (Figure 2b). Symptomatic follow‐up after PPI initiation was done in 94% and 83% for high‐ and low‐dose PPI therapy, respectively. Rebiopsying after 8 weeks PPI treatment was done in 67% of the EoE patients. The EoE patients treated with high‐dose PPI therapy were rebiopsied in 73% of the cases and 53% for low‐dose PPI therapy (Table 2). Of the EoE patients being rebiopsied, 43% had ≥8 biopsies sampled in accordance with the regional guideline, and 66% had ≥6 biopsies sampled. Treating patients with PPI therapy for more than 16 weeks did not seem to improve efficacy (Figure S1).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective, registry‐based DanEoE cohort study, data from 236 adult EoE patients were evaluated for PPI effectiveness and follow‐up regimen compared to the regional guideline. PPI therapy was initiated in 92% of the patients with EoE, and high‐dose PPI therapy was chosen for 55% of the patients treated with PPIs. When treated with high‐dose PPI, 68% of the patients were completely symptom‐free, and 49% were in histological remission. In almost 40% of the patients, symptomatic and histological PPI responses were conflicting. Complications in PPI‐treated EoE patients were below 5% in responders and below 10% in non‐responders.

The study design was strong and based on the Danish medical registries, ensuring a high grade of external validity. 16 In Denmark, all citizens are assigned a unique personal identification number, thus enabling clear differentiation between individuals and access to all medical records in the country. 19 , 20 We were, therefore, able to review all medical information, and the patient phenotype has been determined in 97% of the cases in the DanEoE cohort describing this population well. Weaknesses were that the cohort included patients from only one of five regions. However, the regions are similar with respect to geographical and demographical data. 25 The study was retrospective, and therefore the clinical information from the medical records was not always described systematically and dysphagia scoring by a validated questionnaire was not possible. Almost all patients were treated with pantoprazole, which makes comparisons within different PPIs impossible for the time being. One‐third of the EoE patients started on PPI treatment were not rebiopsied, and we cannot know if they were in histological remission or not. Furthermore, 8% of the EoE patients were not started on PPIs and the clinical information accessible was sparsely. This group was excluded, and we have no knowledge whether the patients developed complications. Another limitation was that the number of patients in the subgroups were too low for a multivariate analysis, and data are currently collected for the time period 2018–2020 to remedy that forward.

In EoE patients treated with PPI therapy, complete symptom resolution and histological remission were more likely to occur when higher doses of PPI were used instead of lower doses, comparing well to earlier findings. 15 When treated with high‐dose PPIs, complete symptom resolution was seen in almost 70% and histological remission in half of the patients. In the literature, the histological response ranged from 23%–83% when treated with PPI therapy. 4 In a prior meta‐analysis by Lucendo et al. 13 data from 619 patients, including both children and adults treated with high‐ and low‐dose PPIs, showed that PPI therapy overall led to a clinical response in almost 61% and histological remission in half of the patients, fitting well with our data. In general, studies on the effectiveness of PPI treatment in EoE patients are heterogeneous in population, study design, type and doses of PPIs, and the number of cases included are often small, which makes comparison difficult. Moreover, the definition of symptomatic response varies from a 50% symptom decrease to complete symptoms resolution as in our study. Another aspect to consider is ongoing changes in the definition of the diagnosis EoE, which has been developing since the first consensus in 2007 to the last definition published in 2018. 1 , 3 , 4 In these definitions, GORD was first excluded and later included, which would result in expected differences in PPI response as EoE with GORD responds well to PPIs, and GORD with eosinophilia have less effectiveness to PPIs. 11

A recently published study by Laserna‐Mendiate et al. 15 from 2020, including 630 adults and children, reported a combined efficacy for PPIs in achieving both clinical and histological remission in half of the patients. This is higher compared to the current study, where 38% had combined clinical and histological remission on high‐dose PPI therapy. This is probably explained by the difference in symptomatic responders as Laserna‐Mendiate et al. used a decrease of more than 50% from baseline in the Dysphagia Symptoms Score where we used the term ‘completely symptom‐free’ in the patient file.

When treating with PPI therapy in both high and low doses, complications were rarely seen in this study with <5% food bolus obstruction and strictures in responders and <10% in non‐responders. This is considerably lower than previously reported in the literature, where stricture prevalence for EoE in a larger adult series ranges from 11% to 31%. 1 , 26 , 27 Croese et al. 28 reported in a study from 2003 stricture formation in up to 57% of the patients. These studies had an observation time between 7 years and up to almost 30 years. Furthermore, the risk of complications was previously calculated by Dellon et al. 29 to double for every 10‐year increase in age. The lower complication rate found in our study may be due to the shorter observation time of approximately 4 years (mean 207 weeks). It could also be influenced by the use of over‐the‐counter PPIs sold in Danish pharmacies, which is without our knowledge. Lastly, the low rate of complications may be caused by the registry approach where patients are included by inflammation with eosinophilia in the biopsies. Therefore, some of the EoE patients in the current study had a low symptom burden and possibly milder disease presentation than some of the patients in the studies compared to.

In 39% of high‐dose PPI‐treated EoE patients, the symptomatic and histological responses were conflicting. One group of patients was still inflamed but completely asymptomatic even though they had been treated with high‐dose PPI therapy. These patients were either truly asymptomatic despite the inflammation or accustomed to dysphagia through so many years that any improvement was highly appreciated, and mild symptoms were neglected. Previous studies 29 , 30 have found that the duration of untreated inflammation is strongly associated with stricture development. In our study, particular stricture formations were rarely seen in asymptomatic patients regardless of the degree of inflammation in the biopsies, and maybe symptom resolution is more important than ongoing inflammation when predicting the risk of developing strictures in EoE patients. Further investigation is needed to see if these patients who are still inflamed but asymptomatic over time will develop strictures if not started on other treatment. The other group of patients experienced dysphagia despite being in complete histological remission and having no stenosis. If this group of patients had not been rebiopsied, they could falsely have been evaluated as having active disease and started on the next class of drugs unnecessarily. These patients should be evaluated for other causes of oesophageal dysfunction. This finding supports the importance of biopsying all patients with dysphagia, regardless of the macroscopic findings, to ensure the right treatment.

Our study showed that most of the EoE patients were treated with PPIs, and high‐dose PPI therapy was chosen for over half of the patients treated with PPIs. During the study period, guideline recommendations was changed, and the first national EoE guideline was published in 2015 recommending high‐dose PPI therapy as first‐line treatment in line with the regional guideline implemented in 2014. After the implementation 86% of the EoE patients were treated with high‐dose PPIs as recommended. Rebiopsying was more often done in patients prescribed higher doses of PPIs instead of lower doses, indicating that the clinician who knew that high‐dose PPI treatment was necessary also had read that rebiopsying was recommended. Rebiopsying after the initiation of PPIs was not done as recommended in almost half of the EoE patients treated with low‐dose PPIs and 25% of the EoE patients treated with high‐dose PPIs. Some patients may have refused rebiopsying due to discomfort, which was not recorded. In patients with complete symptomatic resolution on PPI therapy, the procedure could falsely be found unnecessary by the clinician. Fewer than half of the EoE patients rebiopsied had ≥8 biopsies sampled, which could be due to lack of awareness or due to an uncomfortable patient, explained by only one‐fifth of the patients having received IV sedation or general anaesthesia when rebiopsied. Before the regional biopsy guideline was published in 2011 the incidence of EoE in the North Denmark Region was very low (0.2/100.000), 16 and the disease was almost non‐existing. Even though the awareness of EoE has increased, one‐third of the EoE patients treated with PPIs were not rebiopsied as recommended by the regional guideline.

CONCLUSION

In this registry‐based population of the North Denmark Region, high‐dose PPI therapy was effective in half of the EoE patients treated with PPIs, but conflicting symptomatic and histological PPI responses were common. Complications were rare when PPI therapy was started, and symptomatic PPI response seemed more important than histological in stricture formation. One‐third of EoE patients were not rebiopsied, indicating a continued lack of EoE awareness.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Specific author contributions were as follows: Study concept and design: Line Tegtmeier Frandsen and Anne Lund Krarup; acquisition and analysis of data: Anne Lund Krarup; interpretation of data: Line Tegtmeier Frandsen and Anne Lund Krarup; drafting of manuscript: Line Tegtmeier Frandsen, Anne Lund Krarup, Signe Westmark and Dorte Melgaard; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Signe Westmark and Dorte Melgaard; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information 1

Supporting Information 2

Supporting Information 3

Supporting Information 4

Supporting Information 5

Supporting Information 6

Frandsen LT, Westmark S, Melgaard D, Krarup AL. Effectiveness of PPI treatment and guideline adherence in 236 patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis—Results from the population‐based DanEoE cohort shows a low complication rate. United European Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(8):910–8. 10.1002/ueg2.12146

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21:575–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina‐Infante J, Furuta GT, Spergel JM, Zevit N, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shaheen NJ, Mukkada V, Eichinger CS, Schofield H, Todorova L, Falk GW . Natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review of epidemiology and disease course. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31(8):doy015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molina‐Infante J, Gonzalez‐Cordero PL, Ferreira‐Nossa HC, Mata‐Romero P, Lucendo AJ, Arias A. Rising incidence and prevalence of adult eosinophilic esophagitis in midwestern Spain (2007‐2016). United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population‐based studies. Lancet. 2017;390:2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Navarro P, Arias Á, Arias‐González L, Laserna‐Mendieta EJ, Ruiz‐Ponce M, Lucendo AJ. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: the growing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population‐based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:1116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen ET, Aceves SS, Bonis PA, Bray K, Book W, Chehade M, et al. High patient disease burden in a cross‐sectional, multicenter contact registry study of eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;71:524–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bohm M, Richter JE, Kelsen S, Thomas R. Esophageal dilation: simple and effective treatment for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal rings and narrowing. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Molina‐Infante J, Rivas MD, Hernandez‐Alonso M, Vinagre‐Rodríguez G, Mateos‐Rodríguez JM, Dueñas‐Sadornil C, et al. Proton pump inhibitor‐responsive oesophageal eosinophilia correlates with downregulation of eotaxin‐3 and Th2 cytokines overexpression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:955–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gonsalves NP, Aceves SS. Diagnosis and treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lucendo AJ, Arias Á, Molina‐Infante J. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor drugs for inducing clinical and histologic remission in patients with symptomatic esophageal eosinophilia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laserna‐Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Savarino E, Perelló A, Pérez‐Martínez I, Guagnozzi D, et al. Efficacy of therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in real‐world practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2903–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laserna‐Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Guagnozzi D, Savarino E, Perelló A, Guardiola‐Arévalo A, et al. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic oesophagitis in 630 patients: results from the EoE connect registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krarup AL, Drewes AM, Ejstrud P, Laurberg PT, Vyberg M. Implementation of a biopsy protocol to improve detection of esophageal eosinophilia: a Danish registry‐based study. Endoscopy. 2021;53:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melgaard D, Westmark S, Laurberg PT, Krarup AL. A diagnostic delay of 10 years in the DanEoE cohort calls for focus on education—a population‐based cross‐sectional study of incidence, diagnostic process and complications of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the North Denmark Region. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2021;9:688–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Erichsen R, Lash TL, Hamilton‐Dutoit SJ, Bjerregaard B, Vyberg M, Pedersen L. Existing data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish National Pathology Registry and Data Bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2010;2:51–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frank L. Epidemiology. The epidemiologist's dream: Denmark. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2003;301:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frank L. Epidemiology. When an entire country is a cohort. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2000;287:2398–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lucendo AJ, Molina‐Infante J, Arias Á, Arnim U, Bredenoord AJ, Bussmann C, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence‐based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:335–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vakil N, Van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence‐based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:16928254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett's oesophagus. Lancet (London, England). 2009;373:850–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal F, Galmiche J, et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andersen O. Det nye demografiske danmarkskort ‐ Befolkningen i de nye kommuner. 500th ed. København: Danmarks Statistiks Trykkeri; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Wilson LA, Woosley JT, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Elias RM, et al. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, Chong AKH, Whitaker DA, Kanowski PA, et al. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:516–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SLW, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:577–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warners MJ, Nijhuis RABO, de Wijkerslooth LRH, Smout AJPM, Bredenoord AJ. The natural course of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Long‐term consequences of undiagnosed disease in a large cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information 1

Supporting Information 2

Supporting Information 3

Supporting Information 4

Supporting Information 5

Supporting Information 6

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.