Abstract

Objectives

Death reporting and certification forms are essential elements of a country's healthcare policies. KSA faces several challenges regarding death reporting and certification. This study aims to provide recommendations to unify death notifications in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

In 2019, the General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council designed a qualitative research project that aimed to provide recommendations to unify death notifications. The council convened a task force of physicians and healthcare administrators to design and conduct qualitative research to review the Saudi Health Council's policies related to death certification and investigate potential methods of improvement. In addition, the task force performed an extensive review of the literature and current practices in KSA.

Results

The task force proposed a set of robust recommendations to correct the issues affecting the current systems of death reporting and certification.

Conclusions

This report presents the working methodology and recommendations of the task force.

Keywords: Autopsy, Cause of death, Death certification, Death reporting, Electronic reporting

الملخص

أهداف البحث

تعد نماذج الإبلاغ عن الوفاة وإصدار الشهادات جزءا أساسيا من سياسات الرعاية الصحية للبلد. هناك العديد من التحديات المتعلقة بالإبلاغ عن الوفيات وإصدار الشهادات في المملكة العربية السعودية.

طرق البحث

صممت الأمانة العامة للمجلس الصحي السعودي في عام ٢٠١٩، مشروع بحث نوعي يهدف إلى تقديم توصيات لتوحيد إخطارات الوفاة. شكل المجلس فريق عمل من الأطباء ومسؤولي الرعاية الصحية لتصميم وتطبيق بحث نوعي لمراجعة سياسات المجلس الصحي السعودي المتعلقة بشهادة الوفاة وللتحقق من الوسائل المختلفة لتحسينها. كما أجرى فريق العمل مراجعة شاملة للأدبيات والممارسات الحالية في المملكة العربية السعودية.

النتائج

اقترح فريق العمل مجموعة من التوصيات القوية لتصحيح المشكلات التي تؤثر على الأنظمة الحالية للإبلاغ عن الوفيات وشهادات الوفاة.

الاستنتاجات

يعرض هذا التقرير منهجية العمل وتوصيات فريق العمل.

الكلمات المفتاحية: تشريح الجثة, سبب الموت, الإبلاغ عن الوفاة, شهادة الوفاة, إعداد التقارير الإلكترونية

Introduction

When a death occurs, regardless of the reason, it must be investigated and recorded, and a complete and correct death certificate must be issued. The death certificate is a legal and statistical document for government agencies,1, 2, 3 used to record the cause of death and its mode and manner. Depending on the circumstances, a number of investigations, including a clinical or pathological autopsy,4 may be performed to obtain the necessary information to complete a death certificate.

It is crucial that everyone involved in end-of-life care and death certification be trained in the proper procedures to mitigate stress and difficulty for the loved ones of the deceased. All paperwork must be filled out speedily and efficiently, and questions must be phrased to cause the least pain to the bereaved family. In addition, sensitivity to religious and cultural preferences is of the utmost importance. Employees in this industry require sensitivity training and familiarity with institutional and local procedures to prevent errors. Policies related to the handling of deaths must be reviewed and updated frequently.2

Furthermore, heads of departments and managers must be up to date on the use of new technologies to simplify and expedite the death certification process in order to reduce stress and undue pain for families. Designated staff should be responsible for keeping up with the literature on death reporting to ensure the best possible decision-making. A common thread worldwide in handling deaths both inside and outside hospitals is a need for continuous auditing and monitoring of procedures by managers and agency officials.5,6 As such, a system for handling complaints compassionately and sensitively must be implemented. Careful documentation and strict adherence to guidelines helps to mitigate the risk of problems, particularly in unusual or challenging situations, such as wartime or pandemics.7 These general procedures are applicable to most countries and should be deployable under diverse circumstances.8

In 2015, the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO) put forward a proposal establishing the Civil Registration of Vital Statistics, an internationally linked system for the recording and sharing data on births, marriages, identifications, deaths, causes of death, and more.9 The WHO recognized that accurately defining a person's underlying cause of death—the chain of events or the fatal event—is of the utmost importance when providing health statistics for accurate record-keeping and epidemiological studies.10 Under the WHO system, death certificates are coded using an automated program called Iris to accurately identify and define the underlying cause of death.11 The international death certificate form issued by the WHO as per volume 2 of ICD-10 forms the basis of Iris. Moreover, the cause of death is coded following the ICD-10 rules and updated based on the WHO timeline.11 Progress has been made worldwide in implementing the WHO Civil Registration of Vital Statistics program, and it is hoped that a switch to electronic forms and transmission will be forthcoming, making electronic death registration standard in all countries.

However, current practices related to the investigation of deaths and the completion of death certificates vary widely across the globe. In the US, the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention serves as a repository for birth and death information. The US has 57 vital statistics jurisdictions, and it developed the Electronic Death Reporting System12 to provide timely health surveillance information and cause-of-death reporting to alert authorities to the possibility of an infectious disease outbreak or an environmental hazard. In addition, Electronic Death Reporting System data are vital for healthcare policy planners and service developers. The goal of the system is to complete and rapidly report data within ten days of the event from all jurisdictions across the country. The Electronic Death Reporting System has the advantages of rapid entry, ease of editing, seamless transmission to other agencies, and email reminders to ensure compliance. On a state-by-state basis, the system is implemented by the Bureau of Vital Statistics (births and deaths) to ensure the timely acquisition of all necessary information regarding death and make it accessible to relevant authorities.12 Electronic data processing has increased registration speed from weeks to a few days and has substantially increased the accuracy of death certificates.

Likewise, other countries have established central electronic repositories for the collection of death information. Scotland established an online death recording system in 2016, while England has to date continued to use its existing paper methods.13,14 Other European countries have begun using a form of electronic reporting with Iris, the automated cause-of-death software package described above. France initiated electronic death certification in 2007,11 reducing error rates by more than 50%, improving data reliability, lowering costs, and increasing the speed of the process. Finland,15 Sweden,16 India,17 South Africa,18 and Taiwan19 use electronic reporting systems and have established death certification procedures of sufficiently high accuracy. However, other countries face challenges in death reporting. Vietnam has no proper death reporting system.20 Thailand's system has been shown to have high levels of errors.21,22 Singapore does not use a digital system.23 China lacks a standardized country-wide system.24 Researchers in Kuwait have found that death registration lacked completeness.25 In the UAE, 10% of death causes were misclassified.26 Similarly, KSA faces a number of challenges when it comes to death reporting, including varied death certification practices depending on the health service sector and the lack of a standardized electronic reporting system.2

The Saudi healthcare system

The healthcare system in KSA is a mix of public and private institutions, each with their own administrative structures and reporting systems. In 2017, 259 Ministry of Health hospitals with a total of 35,828 beds were operating in KSA. In addition, various health facilities under the administration of other governmental sectors included King Saud University Medical City, other university hospitals, medical centres in the Kingdom, Armed Forces hospitals, National Guards medical services, Ministry of Interior medical services, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centres in Riyadh and Jeddah, Royal Commission hospitals, Aramco hospitals, school health units, Youth Welfare, the Saudi Red Crescent Society, the Saline Water Conversion Corporation, and the Institute of Public Administration. In 2018, the total number of hospital beds in the facilities of other governmental sectors was 12,662.27 Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of hospitals across different health sectors.

Figure 1.

Distribution of hospitals in the various sectors of the healthcare system, KSA.

A range of health facilities are managed by the private sector in the Kingdom. In 2018, Riyadh and Jeddah had the highest number of private sector hospitals (40 in each city), constituting about 50% of all private hospitals.27 Riyadh had the highest number of hospital beds in the private sector (5737 beds, 30%), followed by the Eastern region (4081 beds, 25%). The total number of general and specialized polyclinics was 2922, with Riyadh accounting for 1077 (37%), followed by 423 (15%) in Jeddah. The total number of private pharmacies was 8683, representing a rate of 1 pharmacy per 3848 people.

The fragmented nature of the healthcare system in KSA has led to inconsistencies in approaches across various sectors, particularly regarding death reporting. Ministry of Health facilities use an electronic system to report deaths; however, facilities in other parts of the system have their own forms and procedures for collecting and reporting death-related information.

Electronic mortality reporting system

The electronic death notification system is part of the birth and mortality system project developed by the Saudi Ministry of Health and integrated with the Ministry of the Interior (Figure 2). It uses two forms:

-

•

The electronic death notification form, which records the notification number, date of death, data on the deceased, the country and city in which the death occurred, the cause of death, the refrigerator number, and data on the recipient of the body. It aims to speed up the death notification process to meet the requirements of the relevant agencies. Data are shared electronically with civil authorities who complete the documentation of the deceased as well as other bodies, such as the Saudi Central Bank and the Ministry of Justice.

-

•

The electronic information of the deceased, which lists the cause of death and other medical data of critical importance for public health prevention measures.

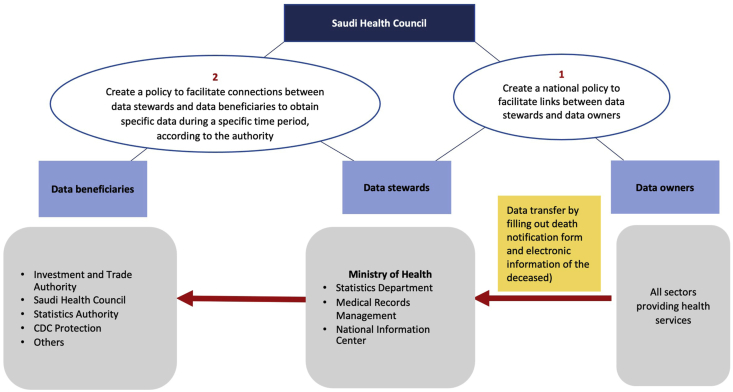

Figure 2.

Role of the Saudi Health Council and concerned authorities.

The healthcare service sectors involved with the death complete the above forms and send them electronically to the Ministry of Health (Figure 3), which transmits the data to the relevant authorities. These data are kept in the database in the Department of Statistics at the Ministry of Health. The system is currently operational in all hospitals affiliated with the Ministry of Health. In other sectors that provide health services, the electronic system is employed by some hospitals, such as those that are part of the medical services of the Armed Forces and those affiliated with the General Administration of Medical Services at the Ministry of the Interior. Hospitals that are not using the system—such as King Faisal Specialist Hospitals and Research Centre and the Security Forces Hospital in Riyadh—use different forms of their own development to report deaths to the Ministry of Health.

Figure 3.

Current status of the death notification system, adapted from https://lean.sa/; https://www.moh.gov.sa/Pages/Default.aspx.

Procedures for registering deaths in hospitals

The process of recording data for deceased persons in the electronic death notification system in hospitals involves four people that receive in-service training (Figure 4):

-

•

Doctor, who writes the death report, whether the case was inside or outside the hospital.

-

•

Death registrar, who enters the required information in all fields of the death notification form after referring to the medical file of the deceased and the death report prepared by the doctor. Conditions for an appointment are being a Saudi national, being specialized only in registering death cases, and having passed the legal security survey. After the required conditions are met, the registrar is granted a validity-of-use permit for the system approved by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of the Interior.

-

•

Mortality manager, who reviews and verifies the correctness of the information entered by the registrar in the death notification form. Conditions for an appointment are being a Saudi national, working in the Department of Mortality, and having passed the legal security survey. After the required conditions are met, the director of mortality is granted a validity-of-use permit for the system approved by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of the Interior. This task is in addition to the manager's assigned hospital work.

-

•

Hospital system director, whose duties include appointing the hospital director of mortality, the registrar, and system administrators, following up on users in terms of daily admission cases, resolving users' problems, and informing the district/governorate coordinator of any reporting situation problem that the hospital's system manager was unable to resolve. Conditions for an appointment are being a Saudi national and having passed the legal security survey. After the required conditions are met, the auditor is given a validity-of-use permit for the system approved by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of the Interior. This task is in addition to the director's assigned hospital work.

Figure 4.

Parties responsible for providing and entering mortality data.

The Ministry of Health undertakes the process of supervising the system, and the follow individuals are responsible for the supervision process:

-

•

System director at the ministry, who supervises system workflow.

-

•

Technical support at the ministry, who resolves major problems related to the system.

-

•

District coordinator, whose duties include assigning users belonging to the region (director of the system for each hospital, area coordinator for the same region), transferring work procedures on the system to hospitals, supervising the workflow of the system in the region, resolving problems faced by system administrators in hospitals affiliated with the region (such as forgotten passwords), and communicating with system administrators at the Ministry of Health in the event of any obstacles faced by users that could not be resolved and clarifying their data in the facility.

Procedures for registering deaths outside of hospitals

Outside of hospitals, procedures for handling deaths differ according to the place of death and whether it was natural or criminal (Figure 5).

-

•

Criminal deaths are referred directly to forensic medicine in coordination with the police.

-

•

Natural deaths are categorized as having occurred inside or outside the hospital. In-hospital death procedures are explained in the section above. For deaths outside of hospitals, the procedures depend on whether the person was inside or outside of the Kingdom.

-

•Deaths inside the Kingdom are divided into those occurring inside and outside cities, governorates, or centres.

-

○Procedures to handle deaths outside cities, governorates, and centres—for example, in traffic accidents on highways—are the only procedures that are officially outlined in Cabinet Resolution No. 344 (16/16/1437H).

-

○Within cities, governorates, and centres, deaths inside a facility or house and those resulting from accidents or fires are included.

-

○

Figure 5.

Procedures for registration of deaths outside hospitals.

When a death occurs outside a hospital, the body becomes the responsibility of the individual providing healthcare to the deceased person. If such a person is unknown, the body is referred directly to a hospital with the Ministry of Health.

Procedures for registering foetal deaths

If a foetus is born alive and at least 22 weeks old at the time of death, the death is reported first in the birth system (Ministerial Agency for Civil Affairs system for birth registration), followed by reporting through regular channels. If the child was named, that name is used on the death certificate; otherwise, the mother's name is used, such as “son/daughter (of mother's name).” If the baby was stillborn, it is recorded only in the birth system and not in the mortality system (Ministerial Agency for Civil Affairs system for death registration).

Materials and Methods

Task force

In 2019, The General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council (National Health Economics and Policies General Directorate) convened a task force of physicians and health administrators to review and evaluate the Saudi Health Council's policies related to death certification and investigate ways to improve them (see Table 1). The background of the health administrators included physicians, pharmacists, public health experts, computer specialists, and health informatics. The main goal of the task force was to provide support for coordinating and expediting the completion of death notification forms and the gathering of electronic information on the deceased from all health service sectors. To achieve this goal, the task force conducted a thorough review of death certification practices across KSA and provided a number of recommendations for streamlining and improving the system.

Table 1.

Meeting details, dates, and titles.

1.

|

2.

|

3.

|

4.

|

5.

|

6.

|

7.

|

8.

|

As established by the National Health Economics and Policies General Directorate of the Saudi Health Council, the role of the task force was as follows:

-

•

Provide access to the death notification form and electronic information regarding the deceased to the relevant health care services, including the Ministry of Health, the Medical Services of the Armed Forces, the Health Affairs of the Ministry of the National Guard, the Medical Services of the Ministry of Interior, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, King Fahad Medical City, King Saud University Medical City, Al Habib hospitals, and Dallah hospitals. In addition, other relevant authorities were given access to the information to determine the possibility of their application, including Weqaya – Saudi Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the General Directorate of Traffic Police, Special Forces for Road Security, General Directorate of Civil Defence, Ministerial Agency for Civil Affairs, The National Information Centre, the Red Crescent Authority, and King Saud University.

-

•

Collect death notification forms that were not part of the electronic mortality reporting system and compare them with forms in the electronic system.

-

•

Hold five national workshops to collect observations on the forms from October 2019 to January 2020.

-

•

Conduct internal reviews.

-

•

Study the role of all relevant authorities in the project.

Literature and document review

In September 2019, prior to the first workshop, a group of reviewers conducted a literature search using PubMed with the keywords “death certificate” and “death certification” for English-language papers from 2010 to the search date.

The initial literature search found 3720 reports. After removal of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts, 75 reports were determined to be relevant to the focus of the task force. The reviewers used the framework described in the European Cystic Fibrosis Society to assess the quality of the evidence.28 Of the 75 relevant papers, 29 were of low quality and were discarded, yielding a total of 46 reports that were included in the analysis. The reviewers synthesized the evidence according to the Institute of Medicine standards29 and presented the evidence at task force workshops.

Consensus process and development of recommendations

The task force met five times in the course of developing recommendations. Each workshop consisted of the following:

-

•

Presentation of research findings.

-

•

Separating into groups for focused, small-group discussion.

-

•

Full group discussion of small-group findings.

-

•

Development of consensus recommendations based on research findings and group discussion.

The objectives of the task force were to review the mortality reporting systems in other jurisdictions, identify changes that could be implemented to bring mortality reporting in KSA in line with other jurisdictions, and develop recommendations for implementing those changes.

Results

Over the course of the five workshops, the task force developed a set of 16 recommendations for improving death certification and mortality reporting in KSA (healthcare sector[s] affected by the recommendation are indicated in italics) (see Table 1).

Electronic death notification form

-

•

Recommendation 1: The task force recommends that a process be implemented for revising the existing Ministry of Health electronic death notification form. (Ministry of Health)

-

•

Recommendation 2: The task force recommends that the revised form be established as the standard for electronic mortality reporting across the Saudi healthcare system. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

Death reporting system

-

•

Recommendation 3: The task force recommends that the role of the hospital system director be eliminated, and that those duties be merged with those of the mortality director. (hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 4: The task force recommends that at least six authorized users of the system be provided for each hospital to ensure the availability of more than one person able to as a mortality director to cover times outside official working hours. This individual must have the authority to act as the registrar if the registrar, auditor, and system administrator are absent or if a malfunction occurs in the system platform. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 5: The task force recommends that solutions be found to the problem of insufficient numbers of people qualified to work as registrars on the system. Hospitals need qualified employees able to work on both the birth system and the mortality system. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 6: The task force recommends that the electronic mortality reporting system be connected to the National Information Centre in order to automatically input data based on the national identity number. It must include the full name, nationality, religion, age, sex, and date of birth. This information must be free of errors and non-editable, as these are fixed data that do not change. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior)

-

•

Recommendation 7: The task force recommends that the guidelines attached to the electronic health form be updated based on the recommended changes, provide more detailed explanations of procedures, such as procedures for registering deaths of foetuses, and that they be circulated to all healthcare sectors. (Ministry of Health)

-

•

Recommendation 8: The task force recommends that the role of data managers at the National Information Centre be clarified, including what information is necessary for a unified system as well as a rationale for including this information. (Ministry of Health)

-

•

Recommendation 9: The task force recommends that a formal agreement be established between owners (i.e., hospitals) and stewards (i.e., data centres) regarding the information to be provided to beneficiaries to ensure the privacy of the deceased. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

System supports

-

•

Recommendation 10: The task force recommends that a policy be created to reduce the correction period for errors when entering data. (Ministry of Health)

-

•

Recommendation 11: The task force recommends that a policy be created to provide material benefits to system workers, particularly for alternates who work on the system outside of normal hours. (Ministry of Health, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 12: The task force recommends that a policy aimed at increasing capacity in the registration departments of the system of births and deaths under the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of the Interior be created to ensure 24-h coverage. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 13: The task force recommends that a policy be created to establish a formal regulation of procedures for handling deaths outside hospitals for each pathway. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 14: The task force recommends that mortality related training programs be developed by universities and Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 15: The task force recommends that a process be developed to determine which bodies require treatment before burial to reduce the possibility of disease transmission. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

-

•

Recommendation 16: The task force recommends that a policy be created to link the determination of the cause of death with the healthcare accreditation of the Saudi Centre for Accreditation of Health Facilities as a system for auditing and monitoring the policy, implementation, and outcome of this project, with periodic review for improvement. (Ministry of Health, Ministry of Interior, hospitals)

Discussion

Death certification is important for both medical and government agencies.2, 3, 4 In addition to documenting deaths and providing statistics, death certification provides medical agencies with information about possible causes of death.2, 3, 4 The recommendations made by the General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council are logical and in line with international recommendations. The improvement of the quality of data in the death certificate is seen as an essential task of the General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council similar to that of the WHO.10 The General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council's task force made recommendations that are similar to those adopted by the WHO.10 A major task is to unify the electronic death certificate amongst all agencies involved in death certification. In addition, the WHO adapted electronic death certification.11 Further research should involve considering the adaptation/adoption of the WHO IRIS system and modifying it according to national needs.

Limitations of this study included that some agencies preferred to send personnel from Riyadh. Logistics had an influence and differences between personnel were negligible. Additionally, corresponding agencies elected the personnel, which may have introduced a bias.

Another limitation relates to the implementation of these recommendations. A major obstacle is that the General Secretariat of the Saudi Health Council does not have the authority to implement the recommendations. However, it has the ability to publish the recommendations. This is similar to the WHO as a non-enforcing agency.

As noted in Recommendation 5, the numbers of qualified individuals are low. Therefore, increasing the number of qualified personnel via in-service training or certificate-based courses may be a solution. Future research examining the application of these recommendations and differences in death certification is highly recommended.

Conclusion

KSA requires a centralized electronic reporting system. Following a targeted literature review, the Saudi Health Council task force proposed a number of recommendations for such a system. Restructuring the hierarchy of the personnel involved in the system would help reduce discrepancies and streamline the reporting process. Connecting the electronic reporting system with the National Information Centre would ensure that data homogeneity is maintained to facilitate maintaining a national register and conducting research. In addition, policy changes were recommended to promote developments, such as helping structure the system, enforcing formal regulations, and introducing reforms in universities. Implementing these recommendations would advance the improvement and updating of the death certification system in KSA and facilitate its utilization by all concerned stakeholders.

Source of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

The authors confirm that this study had been prepared in accordance with COPE roles and regulations. Given the nature of the study, the IRB review was not required.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally conceived and designed the study, conducted research, provided research materials, and collected and organized data. All authors analysed and interpreted data. All authors wrote the initial and final draft of the article and provided logistic support. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the College of Medicine Research Center, King Saud University, and the National Health Economics and Policies General Directorate, Saudi Health Council, KSA.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Taibah University.

References

- 1.Agrawal S. How to write a correct death certificate and why? IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2017;16:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aljerian K. Death certificate errors in one Saudi Arabian Hospital. Death Stud. 2019;43:311–315. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2018.1461712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alipour J., Karimi A., Haghighi M.H.H., Teshnizi S.H., Mehdipour Y. Death certificate errors in three teaching Hospitals of Zahedan, Southeast of Iran. Death Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07481187.2020.1801893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aljerian K. The final consultation: the autopsy. J Forensic Leg Investig Sci. 2017;3:17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raadschelders J., Vigoda-Gadot E. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. Global dimensions of public administration and governance: a comparative voyage. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2016. Making every baby count: audit and review of stillbirths and neonate deaths: highlights from World Health Organization 2016 audit guide. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aljerian K., Ba Hammam A.S. COVID-19: lessons in laboratory medicine, pathology and autopsy. Ann Thorac Med. 2020;15:138. doi: 10.4103/atm.ATM_173_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Waheeb S., Al-Quandary N., Aljerian K. Forensic autopsy practice in the Middle East: comparisons with the west. J Forensic Leg Med. 2015;32:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Bank, World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2015. Global civil registration and vital statistics: scaling up investment plan 2015–2024. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rampatige R., Mikkelsen L., Hernandez B., Riley I., Lopez A.D. Systematic review of statistics on causes of deaths in hospitals: strengthening the evidence for policy-makers. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:807–816. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.137935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iris Institute . 2015. Cologne: federal Institute for drugs and medical devices.https://www.dimdi.de/dynamic/en/classifications/iris-institute/index.html Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2016. Electronic death reporting system online reference manual.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/edrs-online-reference-manual.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health and Social Care . Department of Health and Social Care; London: 2016. An overview of the death certification reforms.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/changes-to-the-death-certification-process/an-overview-of-the-death-certification-reforms Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peres L.C. Post-mortem examination in the United Kingdom: present and future. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:1–3. doi: 10.4322/acr.2017.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahti R.A. University of Helsinki; 2005. From findings to statistics: an assessment of Finnish medical cause-of-death information in relation to underlying-cause coding. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godtman R., Holmberg E., Stranne J., Hugosson J. High accuracy of Swedish death certificates in men participating in screening for prostate cancer: a comparative study of official death certificates with a cause of death committee using a standardized algorithm. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:226–232. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.559950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotabagi R.B., Chaturvedi R.K., Banerjee A. Medical certification of cause of death. Med J Armed Forces India. 2004;60:261–272. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80060-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehohla P. 2012. Cause of death certification: a guide for completing the notice of death/stillbirth.https://www.samrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/files/2017-07-03/CODcertificationguideline.pdf Statistics South Africa. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng C.L., Chien H.C., Lee C.H., Lin S.J., Yang Y.H.K. Validity of in-hospital mortality data among patients with acute myocardial infarction or stroke in National Health Insurance Research Database in Taiwan. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walton M., Harrison R., Chevalier A., Esguerra E., Van Duong D., Chinh N.D. Improving hospital death certification in Viet Nam: results of a pilot study implementing an adapted WHO hospital death report form in two national hospitals. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choprapawon C., Porapakkham Y., Sablon O., Panjajaru R., Jhantharatat B. Thailand's national death registration reform: verifying the causes of death between July 1997 and December 1999. Asia Pac J Publ Health. 2005;17:110–116. doi: 10.1177/101053950501700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tangcharoensathien V., Faramnuayphol P., Teokul W., Bundhamcharoen K., Wibulpholprasert S. A critical assessment of mortality statistics in Thailand: potential for improvements. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:233–238. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.026310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singapore Legal Advice . Singapore Legal Advice; Singapore: 2019. Death procedures and all death expenses in Singapore 2019.https://singaporelegaladvice.com/law-articles/death-registry-autopsy-funeral-expenses-singapore/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiaying Z., Edward J.C.T., Chi-kin L. The incomparability of cause of death statistics under “one country, two systems”: Shanghai versus Hong Kong. Popul Health Metrics. 2017;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah N.M., Shah M.A., Al-Sayed A.M. Quality of birth and death notifications in Kuwait. Med Prin Pract. 1992;3(2):102–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barss P., Grivna M., Al-Dhaheri A., Harrison O. New death notification form and training in the United Arab Emirates as improved sources of data on injury and other main causes. Inj Prev. 2010;16(Suppl 1):A243. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health; 2018. Health statistics annual book. [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Boeck K., Castellani C., Elborn J.S., ECFS Board Medical consensus, guidelines, and position papers: a policy for the ECFS. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(5):495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research . In: Eden J., Levit L., Berg A., Morton S., editors. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. (Finding what works in health care: standards for systematic reviews). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]