Abstract

Background

The ANA Code of Ethics for Nurses, regularly revised since 1896, may not provide guidance in an era of pandemic and sociopolitical unrest.

Purpose

This study explored whether the Code of Ethics comprehensively address current nursing challenges.

Methods

23 nurses participated in six Zoom focus groups to discuss whether provisions were applicable to their current practice. An iterative approach was used to review transcripts independently and then merge findings to identify ethical themes.

Findings

Provisions 4, 6, and 8 were most relevant. None of the provisions addressed the guilt secondary to isolating patients from support systems and not being “on the front lines” of COVID care.

Discussion

The co-occurring crises of COVID-19 and social unrest created an ethical crisis for many nurses. The Code of Ethics provided a useful guide for framing discussion and formulating strategies for change, but did not eliminate distress during a time of novel challenges.

Keywords: Code of ethics, Pandemic, Registered nurses

1. Background

Moral distress, compassion fatigue, and burnout are commonly reported consequences from the profession of nursing. Often, these feelings arise secondary to ethical issues experienced in the clinical setting (Peter, 2018).

While many studies have examined ethical issues particular to specific practice areas of nursing, Ulrich et al. (2010) were among the first to conduct a large regional survey of all nurses within four states from a major regional census area in the USA. The researchers assessed ethical concerns and the stress associated with them, finding that protecting the rights and autonomy of patients, assuring informed consent to treatment, adequate staffing levels, and facilitating end-of-life and surrogate decision making were most frequent. Similarly, when using nurse interviews to structure a Q-sort methodology, Chen et al. (2016) found the top three sources of ethical concerns were “conflict with personal values,” “excessive workload,” and “curbing of autonomy.”

A review of the literature on leading ethical dilemmas experienced by clinical nurses (Haahr et al., 2019) revealed that the most common sources of challenge clustered around three areas of practice: nurse–patient relationships, organizational context, and interprofessional collaborations. Specifically, the authors described three themes related to these domains as “balancing harm and care, work overload influences quality, and navigating in disagreement.”

Haddad and Geiger (2020) state, “Nurses at all levels of practice should be involved in ethics review in their targeted specialty area.” However, it is of concern that in an early study of behaviors used when ethical challenges occur, researchers asserted that nurses may rely on a conformist response (Dierckx De Casterlé et al., 2008).

The ANA Code of Ethics captures the long history of nursing concern in this area, beginning with the Nightingale Pledge of 1893 (Tinnon et al., 2018). Although it is considered universally applicable because our moral code remains the same even as our practice changes, crises such as pandemics and global traumas have the potential to alter how front line providers respond. Specifically, Iserson (2020) says, “In most disasters, and certainly during the current COVID-19 pandemic, frontline healthcare professionals face two key ethical issues: (1) whether to respond despite the risks involved; and (2) how to distribute scarce, lifesaving medical resources.”

During times of crises, each nurse must critically balance duty to care with potential harm to self. In one study, 289 US nurses were sorted by their willingness to care during crises. High vs. low willingness to care was attributed to fear of abandonment by co-workers, a philosophy that it was “the correct thing to do,” and a perceived ethical obligation (McNeill et al., 2020). However, Turale et al. (2020) wrote about the numerous Facebook posts from nurses around the world who were providing front line care during the initial phase of COVID-19 and concluded there was an unprecedented demand for “moral courage.”

The need for further study on ethical challenges which arise during pandemic is needed to address novel pressures and stresses for nurses. Rushton and Stutzer (2015) note that: “The impact and urgency of addressing ethical issues nurses face is intensified in the context of internal and external pressures that threaten the integrity of nurses, the profession and the people they serve.” Anecdotal observations suggest that COVID-19 has imposed unique ethical challenges which may be amenable to intervention, prompting design of a study that would seek input from frontline nurses.

2. Study aim

Identifying the ethical concerns of nurses is an important first step in developing resources that might be of benefit. Therefore, the aim of this descriptive study was to examine the relevance of the ANA Code of Ethics during the COVID pandemic.

3. Methods

Qualitative data collection consisted of six virtual focus group sessions. Focus groups have been shown to have a potential benefit to participants because they often facilitate expression and discussion of emotions and rich interactions (Krueger & Casey, 2015).

After receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board for conduct of the study, an invitation to participate in a series of Zoom focus groups was sent to nurses employed throughout two sites of an academic health center. One site was located in a rural/suburban location and the other in an urban/suburban location, with a potential pool of 3000 nurses.

Registered nurses within the system received an email message with a brief explanation of the study and requests for volunteers, although it is not possible to determine how many nurses opened and read the invitation when demands on their time were high and work assignments were in flux. Nurse managers and advanced practice clinicians were included but those in executive level positions were excluded.

To protect identity and confidentiality, only basic demographic information was requested when nurses responded to indicate interest in participating. In addition, at the start of each focus group, subjects were asked not to reveal any personal or identifying information in the group.

Focus groups began on Day 140 of the pandemic's initial statewide lockdown and spanned one week. Eight focus groups were planned offering a variety of days of the week and time of the day. Initially, 65 nurses responded with interest, 40 (61%) registered for a focus group session, and 23 (57%) participated in one of the 60 min sessions. The low response rate was likely offset by the context of the pandemic.

Following the principal of data saturation, the investigators looked for the emergence of repeating themes in the focus groups to determine if further data collection was needed. Saturation was reached following the sixth session so additional groups were not pursued.

After collecting basic demographic data from participants, focus groups were scheduled and conducted virtually using Zoom video and audio technology from a secure account. This approach enabled subjects to participate remotely while recording and storing data. Each session was then transcribed verbatim and edited prior to analysis. All potentially identifiable information such as unit of practice or names of specific participants was redacted.

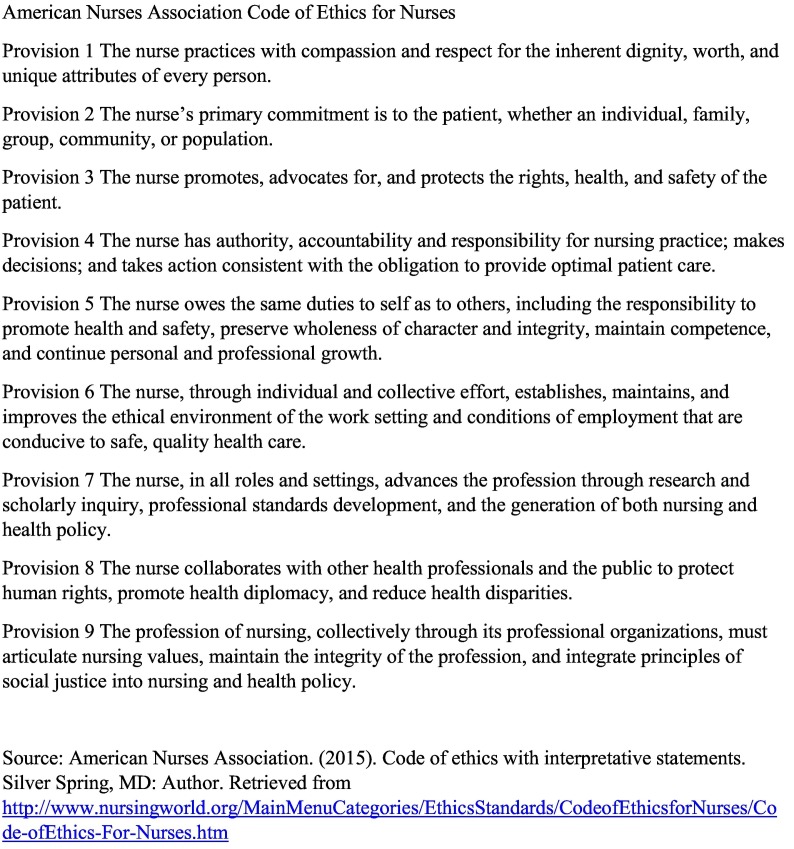

The sessions were conducted using a semi-structured interview approach. Prior to beginning each group, a copy of the current ANA Code of Ethics (ANA, 2015) (see Fig. 1 ) was projected and reviewed to provide a frame of reference and participants were asked to identify which provisions, if any, applied to their practice during the COVID pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Code of Ethics.

An interview guide with further probes about COVID-specific ethical challenges and resources needed moving forward was used to enhance the discussion of the Code of Ethics.

3.1. Sample

A total of 23 participants were enrolled in the study, with a mean age of 48.7 (SD = 10.8) years and a mean of 23.7 (SD = 12.0) years of experience. The participants were 100% female and the majority had either a Bachelor's degree (n = 9, 39%) or Master's degree (n = 11, 48%) in Nursing. The participants practiced in areas of acute care, non-direct care, ambulatory outpatient care, and supportive (education, employee health, quality management). Most of the groups consisted of four to five registered nurses from diverse backgrounds, work locations, and areas of practice per group. None of the groups had individuals who worked in the same unit, although some nurses knew each other from previous associations.

Demographics of the participants are presented in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Demographic | Number of participants | Percentage of participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall total | 23 | 100% | |

| Age group | 20–29 years | 2 | 8.7% |

| 30–39 years | 3 | 13.0% | |

| 40–49 years | 5 | 21.7% | |

| 50–59 years | 11 | 47.8% | |

| 60+ years | 2 | 8.7% | |

| Gender | Female | 23 | 100% |

| Male | 0 | 0% | |

| Highest degree in nursing | ASN/diploma | 2 | 8.7% |

| BSN | 9 | 39.1% | |

| MSN | 9 | 39.1% | |

| MSN – NP | 2 | 8.7% | |

| DNP | 1 | 4.3% | |

3.2. Data analysis and management

The two investigators reviewed the transcripts independently using an iterative approach to compare recurring words, concepts, and ideas within and across transcripts to identify relevant provisions from the Code of Ethics. Once this first level analysis was completed, the investigators met to compare and merge findings from the preliminary review, leading to the identification of themes. Potential researcher bias included connections to or acquaintance with some of the participants which was addressed by having the interviews conducted by the investigator who did not have a clinical appointment or familiarity with participants (CD).

4. Results

There were robust discussions in each group, with participants tending to speak not only about concepts from the provisions but other reflections on challenges of their current practice environment. One nurse said, “I think it's hard to delineate one over another because some of them do coincide with one another.” (G6, P3).

Table 2 contains the provisions were specifically identified by one or more participant as being “most relevant” along with exemplar statements.

Table 2.

Code of ethics provisions with exemplars.

| The following provisions were specifically identified by one or more participant as being “most relevant.” The selections are presented as described by the participant, even when they might not align with the Interpretive Statement of the ANA Code of Ethics (ANA, 2015). | ||

|---|---|---|

| Provision | Endorsed | Exemplar statements |

| Provision 1. The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and personal attributes of every person, without prejudice. | This provision was not selected; however, nurses spoke of compassion and respect. | |

| Provision 2. The nurse's primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population. | One nurse chose both Provision 2 and Provision 3, with this rationale: | “When the pandemic hit, we are thinking about our patients but also thinking about how their care affects the whole family and our community and the population…I struggle with advocating for a family (who) can't get childcare. It's a single mom and they can't get childcare, but they're able to make it to this appointment but the clinic won't let them in because there's more than one person accompanying this patient” (G3, P1) |

| Provision 3. The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health and safety of the patient. | One nurse identified Provision 3 directly: however, many across and within groups spoke about being an advocate for patients. Several nurses confessed to internal struggles over limiting visitors for frail older patients and those who were isolated. | “I think we've all been, as nurses, traumatized by the restricted visitation at various points. And then just helping even using our own devices to make sure that the patients can talk to their family members via technology has been huge and really helpful…And now visitation has eased up a little bit. Certainly been less distressing for some of us nurses, because having that support person at the bedside is just huge.” (G4, P4) |

| “You know that really impacted the way we practice…It impacted them and us. You know of course our team is always supportive and caring and just going above and beyond. But during these scary times, you know our patients are already quarantining and already isolated and then you throw this in the mix. They're terrified and they don't have the same supports that they usually had within the treatment room, within the treatment center and that's impacted us as well.” (G4, P3) | ||

| Provision 4. The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice, makes decisions, and takes action consistent with the obligation to provide optimal care. | Nurses were acutely aware of their responsibility to provide optimal care as well as the tensions that arose in trying to do so. | “You're right, I think we had a lot of people say ‘Yes, I'm ready, I can do it. We can take action.’ There was a lot of involvement in making sure we were doing the right things by ourselves to mitigate our own risk in order to continue to take care of our patient population.” (G1, P6) |

| Another nurse agreed describing the way they acclimated to different units or patient populations. | “So we were challenged with taking care of a lot of SICU patients and medical ICU patients that we aren't used to the care of. Getting to know new teams, their way of doing things, caring for patients and learning about diagnoses we haven't talked about—some of us—in 10–20 years…” (G1, P7) | |

| Others echoed these beliefs with the inability to provide “optimal care.” They also cited the rewards in finding creative ways to communicate with families. | “They need us, I would hope they would need us more now than they ever would… there's a lot of things that are still happening besides COVID out there that we still need to consider in our everyday lives. Appointments were being put on hold and now we have patients coming in that are flaring, can't control their pain because they were afraid to come out and seek care because of COVID.” (G3, P1) | |

| “… every one's coming together and keeping positive and trying to do the best we can. Even some pride in my immediate family, I almost feel like they're helping me take care of you know the community by helping educate a little bit. Yeah, just pride I would say.” (G4, P4) | ||

| Provision 5. The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth. | Only one nurse chose Provision 5, but it prompted others in the group to validate the importance of self-care. | “So I think it was #5 up on the code but [it] was the self-care. That's well you know, we'll just call it self-care for now. You know it's not only my employees but the vulnerable populations that we're taking care of. And you know kind of what all that meant and implementing all those safety standards and so on going forth.” (G4, P3) |

| “I will say I did take my vacation that I had planned…but there was a part of me that felt guilty going away.” (G4, P1) | ||

| “I think as a group, you know, it was mentioned earlier that we take care of everyone and leave ourselves for last. I think that we have to be reminded that it's ok for us to take some time for ourselves. Because you know you just keep going, going, going in this crisis pandemic situation and you really do need to step back and reset. And sometimes, you know you should and sometimes having someone remind you or make you do it is a good thing.” (G6, P1) | ||

| Provision 6. The nurse, through individual and collective action, establishes, maintains, and improves the moral environment of the work setting and the conditions of employment, conducive to quality health care. | One nurse was clear that this provision was very relevant. | “Quality care. I think we all experienced – we went from hand washing, was the big focus to handwashing, masks, gloves, gowns, fit testing, PPE, you know and learning so many new guidelines that changed so frequently…my cardiac rehab nurse went to the testing site. So a huge eye opener for her…You hugged everybody, you were friends with them, to being covered up and swabbing people, you know, watching your distance, maintaining your social distance, going home and showering, changing and washing your clothes.” (G1, P4) |

| Another spoke about the importance of science as a guiding principle. | “I think there's this division in the country, there's a lack of the science and the evidence being shared to really protect people and I think that puts nurses in a really challenging position ethically and it eats away at your moral compass. Because you know the right things to do and what we should be doing, and yet they're not being done.” (G2, P5) | |

| Provision 7. The nurse, whether in research, practice, education, or administration, contributes to the advancement of the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and generation of nursing and health policies. | This provision was not selected although the nurse's role as “scientist” and “educator” was described. | |

| Provision 8. The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect and promote human rights, health diplomacy, and health initiatives. | Two nurses commented on the role of nurses as community ambassadors who were resources for both their colleagues, families, and the larger community. | “And then #8, I think we all do. The nurse collaborates with other healthcare professionals and the public, community, national, international. I'm sure as nurses, we get all of our families reaching out to us for all of their medical questions, guidance, what do you think. I think we all get those calls. And it's been an eye opener. I think it's made me educate myself even more. What should I be telling people, what should I be practicing, what should I be promoting?” (G1, P4) |

| Other nurses noted that the reframing of the practice environment also led to interpersonal challenges related to team collaboration. | “I think for me, Provision 8. Collaborating with other health professionals and the public has been really integral to what I've been doing. I've had to find new ways to connect with the staff in XXX, our schedulers, our providers who have also been working remotely and then relay all this information to our patients and you know keep everybody connected without seeing anyone for months at a time.” (G6, P4) | |

| “I think people came together pretty well especially at the beginning. It was kind of like have each other's back. But then there were definitely people that there was ruffled feathers and talking among (themselves) that they felt like different people were taking advantage of the system…. So then I think there was some angst towards specific people. I didn't really care about that. I just do what I want to do and go to work but that's like lunchroom conversation that you would hear.” (G4, P1) | ||

| “…I just feel like there's 19 different paths and it's so uncertain which was it's going to go that you almost, you can't wrap your head around it to make a good solid plan moving forward other than to just prepare for all 19 paths and then like you said before about the conflict and how other people feel about it and the dissent.” (G1, P6) | ||

| Provision 9. The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy. | Although no one identified Provision 9 as most relevant, there were discussions around the role of nurses given the current political climate and need for social justice. | |

The selections are presented as described by the participant, even when they might not align verbatim with the Interpretive Statement of the ANA Code of Ethics (Fowler, 2017).

5. Thematic analysis

To analyze the text, the framework provided by the ANA (ANA, 2015) was used to examine underlying concepts discussed by participants. Specifically, concepts were sorted into three categories related to the provisions: #1–3 refer to basic values and commitments all nurses share, #4–6 describe the parameters of duty and loyalty, and #7–9 relate to the role of the nurse that transcends relationships with individual patients (ANA, 2015).

5.1. Continuing commitment to core nursing values

The majority of the nurses who participated in the focus groups expressed determination to provide appropriate care as a team, bear the suffering of others, and attempt to maintain resiliency. There was a strong sense of placing duty over personal safety, even early on in the pandemic when information was changing on a daily basis. Said one participant:

“I felt very unsafe because I wanted to wear a mask and was told I was not allowed…Of course the policy changed a week later and I think mostly because a patient was down the hall positive for COVID the day they told me I couldn't wear a mask. …I feel like for the most part we buckle up, go to work, do our job.”

(G4, P1)

Another shared,

“…I feel like we have a duty to represent the evidence and the science and when it turns into something other than science and evidence. I really struggle with that. Because we are scientists, right? And we need to represent the facts and it doesn't really matter which side you're on. You need to be on the side of good science.”

(G2, P1)

Another noted that,

“We're nurses and we just do it. We do what has to be done. Like somebody said, it's a profession by choice. We chose this profession and I think we've all - a good skilled nurse is a critical thinker and we don't panic, we critically think and we figure out how to make things happen and we just make it happen.”

(G1, P4)

A more experienced nurse shared their response to some newer employees who commented that “this isn't what we signed up for”:

“I said well it is what you signed up for. We're nurses. Our job is to take care of people and do the best we can and you know so it is a way of looking at it….you make the change and be the change.”

(G2, P1)

However, there was a toll exacted from these commitments, especially as the pandemic continued unabated. Two participants in Group 2 spoke about the impact of being a nurse during times of crisis:

P5: “I would comment that my observation was initially there was a very tight, supportive environment where people were like you know we're not sure what we're facing. We're kind of all coming together and as time has gone by and COVID has taken, oddly enough, a back seat, we've kind of incorporated that into our work a little bit and I've seen the- I don't want to say disengagement but I want to say I'm seeing the effects of the stress, you know of having to don and doff every time you go out of a room.”

P2: “I agree. The resilience is wearing out. So when this all started we had all kinds of resources because there was no patients to take care of, regular patients, so they gave us all kinds of help. Well ok come May [2020] everything starts ramping back up again. They take those resources away, and so now my team is looking around and we're going they keep wanting us to keep this up but how are we supposed to do it?”

P5: “I think they've run out. I'll go out on a limb and say I think they've run out. It's just getting harder. It's almost like a battery that's drained down and needs to be plugged in for a while and recharged, not necessarily jumped but just recharged.”

To help alleviate this ethical fraying, nurses stressed the need for input by nurses as planning for the future was implemented. Commented one:

“I know that there's some plans for some after action follow ups to what went on as far as the response and how things went… They should include some staff nurses on that so they get our feedback from it. You know how managers feel it went isn't always how staff feel it went. So getting to the front line workers who were there, who were actually taking care of the patients.”

(G4, P2)

5.2. Redefining the parameters of duty and loyalty

Nurses expressed a fierce sense of moral identity as a nurse and the obligation to provide care, with several discussing their sense of failure to perform their duty. Although their roles varied between different areas of research, practice, education and clinical management, those who were not providing direct face-to-face care to COVID patients spoke at length about feeling guilty for this.

“I struggled with the fact that I wasn't actually in the hospital working as a staff nurse. I actually felt very guilty for all of my friends and my fellow nurses who were fighting on the front lines. So that was my struggle, something I still feel guilty about. That was probably the biggest thing. I was never – I wasn't afraid of it. I feel like I had the same calling as XX. But my feeling is of guilt.”

(G3, P1)

“I think that my problem was thinking about, not knowing what was going to happen and thinking about the nurses who are working on the COVID units. Hoping they're ok. I prayed for them a lot. But feeling guilty, almost shameful. That I wasn't there to help. And I'm still sorry that I'm not there to help. Sorry I don't even know where that came from, sorry.”

(G3, P1)

A great deal of loyalty was expressed as nurses commended their colleagues and their employers for providing support and guidance.

“Even with our staffing issues we still met our patient population every day with a smile and positivity and moved forward. Now were we always positive, probably not. But I think presenting that united front made the patient population believe we were and that was important for us to not have any chaos ensue because of how busy our unit is. And I think our management, immediate management team was very, very supportive and it was visible. They were out there with us every day and there wasn't anything about being in an office, they were there and they were part of the team. And I think that was important too for us.”

(G1, P5)

Several others spoke of how their role and commitment to nursing included a need to maintain a healthy self and family so that they could take care of patients, yet this “duty” became challenging at times. Many nurses felt an obligation not to expose family and friends to possible infection. One said,

“Whether it's community, patient, self-care or family, it's a profession by choice. But there's also a responsibility to, for me anyway, of making sure that I'm healthy to be able to take care of myself, to take care of family, to take care of patients. So for me I know it was social distancing, became a big thing. Talking to my family and making them aware there's certain times I could not participate in activities because I had to protect myself to be able to protect everybody else that I came in contact with.”

(G1, P5)

Despite recognizing this “obligation,” nurses often experienced demands on their time that made maintaining their health and fulfilling their duty difficult. This nurse said:

“The other piece I found more personally as a mother to a young child with daycares being shut down. Trying to figure out that self-care piece, like I was working off hours for my husband and trading my daughter in the parking lot with him. And figuring out how I was going to care for myself sleeping with working off shift and still having to take care of her during the day and kind of living day by day. A lot of our nurses kind of fell into that same bucket of the self-care went away. It was work and childcare or school for some of our parents that had young kids in elementary school and figuring that out. So that was a challenge…”

(G 1, P7)

Another noted,

“… I think one thing that's come out of it too is the lack of vacation, I've personally felt like since the pandemic hit I couldn't take off work but I was getting to the point that I was almost crazy.”

(G2, P4)

One nurse commented on how the sense of duty and obligation could become self-defeating:

“And helping the nurses, the people that were showing up at our check-in desk with symptoms and we were like why are you coming to work ill and they're like well it's going to short my unit, it's going to impact you know pay or whatever so they were very struggling with. Nurses are really good at not taking care of themselves and putting their own illnesses aside in order to be here because they don't want to let their coworkers down and let their patients down.”

(G2, P2)

5.3. Transcendent role of the nurse

Nurses were acutely aware of their role beyond patient care. They acted as advocates for families and felt traumatized when they had to “police” visitors and deny contact. One nurse described both the stress and satisfaction that occurred while trying to educate community members on this principal.

“…we had to get very creative dealing with multiple patients, especially the Hispanic populations that were coming into the care areas very sick, very fast. A lot of them were getting irritated…they just didn't understand that having multiple generations, multiple people in a home or an apartment is just not the best thing to do… it was just a lot of balls up in the air and a lot of collaboration with a lot of people that just really did a phenomenal job.”

(G1, P3)

Given national discussions about distribution of resources, one acute care nurse said:

“I'm really thankful in this area. We didn't have to think about who deserved the ventilator or removing a ventilator from someone who needed it or withholding care. I don't think we were faced with that challenge, which is really, very thankful. But it is a potential with a pandemic and I had never really thought about it until the media brought it up as a true crisis that we could face and if we would have had to face it I don't know how I would have felt or emotionally how I would have gotten through it.”

(G1, P7)

Helping nurses and all health care professionals to cope with pandemic-level death and dying was viewed as another important nursing focus:

“Nurses are often the professionals most intimately involved with death and dying. As the initial ‘first wave’ of COVID-19 swept across the country, there was a struggle to cope with not only death, but the dying process in isolation”

Said two participants from Group One:

“I think that we experienced a tremendous amount, a higher volume of death than we're used to ever seeing. I did worry about the staff and the support that they had to go through that. I know that we had spiritual care here but I don't know… are you aware of anything that was done for people who were repeatedly exposed on a daily basis to a lot of death? … I just think we could add some services there that would be really helpful.”

(G1, P3)

“We did have palliative care. I forget the physician's name. She was very involved. She made rounds daily with the critical care staff that were involved with the COVID patients and the priority was the ones, the challenging ones, just to have that support. I know that the staff knew they had a support place to go. So we did have that involved here.”

(G1, P4)

6. Discussion

The nurses in this study experienced a complex response to quarantine and pandemic, which was nested in a time of political unrest and turmoil. Overall, most of the provisions in The ANA Code of Ethics had relevance and provided a helpful prompt for discussions. The majority of the participants expressed gratitude for the opportunity to share their feelings and opinions and indicated a need for ongoing groups that incorporated discussions from different practice areas and sites. In addition, there was a strong sense of pride in the nursing profession and an appreciation for the collaborative efforts that occurred within and across disciplines.

What was not specifically captured by the Code of Ethics was guidance on how nurses could process their sense of guilt for a perceived lack of participation in care and the despair of isolating patients from sources of support. This sense of guilt was expressed by nearly every participant who felt they were not actively “working with COVID” despite expanded workdays for those assigned to remote roles with triage, telehealth, and other patient care activities, there was often an emotional statement about not participating as fully as possible in the bedside care of those acutely ill with the virus.

Nurses who had taken on a more direct role (i.e. providing in-person care to critically ill inpatients) expressed a “warrior” stance, expressing their cohesiveness with other “COVID nurses.” They reported situations where they were treated negatively by peers, with some stigma attached to their role in “fighting” the virus, but also reassured their colleagues that every nurse played an important role.

Despite the many professional and personal challenges, a strong sense of obligation and commitment consistently emerged. These findings align with a previous study of how COVID impacted nursing ethics and practice in that nurses did not question their obligation to continue their work (Sperling, 2021) and research by Fernandez et al. (2020) who found nurses show a high level of commitment despite a sense of risk during crises.

This study did not intend to assess nurses' psychological burden during the pandemic; however this was a repeating theme. Whether moral distress occurred from the role a nurse at or away from the bedside, enforcing the need to maintain patient quarantine, responding to community distress, or sensing tension within the work unit, this might be our most significant finding and one that is not addressed by the ANA Code of Ethics. Dzau et al. (2020) warn of the downstream effect of a “parallel epidemic” related to the physical and mental health effect of those in COVID-19 service, which the current study may support. In response to this potential danger, healthcare professionals and professional organizations worldwide are providing services and resources to promote the well-being of healthcare workers (American Nurses Foundation, 2020; Bernstein et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021).

6.1. Implications for practice

While some of the provisions in the code held more relevance than others, the ethical standards continue to provide guidance for discussions about nursing practice. It was clear that nurses shaped the “moral environment” of their clinical units during COVID-19 as they were the continuity and consistency of the team caring for all patients served by the organization.

Although nurses were clear on the challenges that COVID-19 brought to their practice, there were still struggles. In particular, although nurses recognized the ethical parameters of their practice, establishing a balance between care for self and others, serving as an advocate and role model for families and communities especially during a time of social unrest, and coping with suffering and death, these situations still caused unique stresses and challenges. As they looked forward, nurses felt strongly that COVID-19 was a significant event that will require more than a passing mention in the annals of nursing history.

References

- American Nurses Association . Author; Silver Spring, MD: 2015. Code of ethics with interpretative statements.http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/EthicsStandards/CodeofEthicsforNurses/Code-ofEthics-For-Nurses.htm Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Foundation American Nurses Foundation launches national well-being initiative. 2020. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2020/american-nurses-foundation-launches-national-well-being-initiative-for-nurses

- Bernstein C.A., Bhattacharyya S., Adler S., Alpert J.E. The joint commission on quality and patient safety. Vol. 47. 2021. Staff emotional support at Montefiore medical center during the COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 185–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Lee H., Huang S., Wang C., Huang C. Nurses’ perspectives on moral distress: A Q methodology approach. Nursing Ethics. 2016;25(6):734–745. doi: 10.1177/0969733016664976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierckx De Casterlé B., Izumi S., Godfrey N., Denhaerynck K. Nurses’ responses to ethical dilemmas in nursing practice: meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;63(6):540–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzau V.J., Kirch D., Nasca T. Preventing a parallel pandemic-a national strategy to protect clinician’s’ well-being. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(6):513–515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2011027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R., Lord H., Halcomb E., Moxham L., Middleton R., Alananzeh I., Ellwood L. Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;111(103) doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler M.D. Faith and ethics, covenant and code. Journal of Christian Nursing. 2017;34(4):216–224. doi: 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haahr A., Norlyk A., Martinsen B., Dreyer P. Nurses experiences of ethical dilemmas: A review. Nursing Ethics. 2019;27(1):258–272. doi: 10.1177/0969733019832941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad L., Geiger A. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2020, Feb. 20. Nursing ethical considerations. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iserson K.V. Healthcare ethics during a pandemic. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;21(3):477–483. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R.A., Casey M.A. 5th ed. Sage Publications Inc; Los Angeles, California: 2015. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill C., Alfred D., Nash T., Chilton J., Swanson M. Characterization of nurses’ duty to care and willingness to report. Nursing Ethics. 2020;27(2):348–359. doi: 10.1177/0969733019846645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter E. Overview and summary: Ethics in healthcare: Nurses respond. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2018, January 31;23(1) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No01ManOS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton C., Stutzer K. Addressing 21st Century Nursing Ethics: Implications for critical care nurses. AACN Adances in Critical Care. 2015;26(2):173–176. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M., Roggenkamp M., Ferrer L., et al. Mental health and COVID-19: The psychological implications of a pandemic for nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2021;25(1):69–75. doi: 10.1188/21.CJON.69-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling D. Ethical dilemmas, perceived risk, and motivation among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Ethics. 2021;28(1):9–22. doi: 10.1177/0969733020956376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinnon E., Masters K., Butts J. A pragmatic approach to the application of the code of ethics in nursing education. Nurse Educator. 2018;43(1):32–36. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turale S., Meechamnan C., Kunaviktikul W. Challenging times: Ethics, nursing and the COVID-19 pandemic. International Nursing Review. 2020;67(2):164–167. doi: 10.1111/inr.12598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich C., Tayor C., Soeken K., O’Donnell P., Farrar A., Danis M. Everyday ethics: Ethical issues and stress in nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66(11):2510–2519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]