Abstract

Biological underpinnings (i.e., “bio” of bio-psycho-social approach) of Bipolar Disorder (BD) comes to the forefront when addressing its etiology and treatment. However, it is a condition that is challenging to manage with medication, and often the medication alone is insufficient since the symptoms of the disease have different episode characteristics. When the prevalence and inefficacy of drug treatments are considered together, the cruciality of psychosocial interventions in the treatment of the is undeniable. Moreover, treatment non-compliance is another problem that needs to be addressed psychosocially. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has its unique place among psychosocial interventions with numerous features such as being empirical and flexible, and it is recommended as an evidence-based adjuvant therapy in all stages of the disorder except acute mania. In this review, we discuss how CBT is used in specific domains of the disorder, following a general outlook on the evidence for CBT in BD. We focused on the essentials of psychotherapy practice with a pragmatic approach from the CBT point of view.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, cognitive therapy, behavioral symptoms, psychosocial deprivation

INTRODUCTION

According to the International Classification of Diseases Revision- 10 (ICD-10) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Revision (DSM-5), Bipolar disorder (BD) (1) is a chronic mental illness with episodes of mania, hypomania, and/or depression (2, 3). The lifetime prevalence is 0- 2.4% for bipolar-I disorder, 0.3-4.8% for the bipolar-II disorder, and 0.5-6.3% for cyclothymic disorder. Overall lifetime prevalence is as high as 7.8% when all bipolar disorders are taken into consideration (4). It is a mental disorder in which more emphasis is placed on the “bio” component of the biopsychosocial approach, regarding its etiology. However, studies in the literature have demonstrated that although there are many effective treatment alternatives, people with BD have unmet needs even when they are euthymic (5). Albeit unmet needs for begin with a delay in the diagnosis process, they are not limited to this. Problems continue with the treatment process, following diagnosis. Clinical situations in which different mood symptoms can be present separately or together make it difficult to optimize medications. Despite attempts to balance the response and adverse effects in treatments, it is only possible for a small percentage of patients to relieve symptoms for prolonged periods without residue (6). Hence, one of the foremost problems is that the symptoms of the disorder continue. Other problems are non-compliance with treatment, specific problems related to gender (for example, effective administration of acute and maintenance treatment of pregnant and lactating women), neglected quality of life, loss of social and occupational functionality (7).

The use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in four areas makes a significant contribution to the treatment process:

1. Easing the symptoms of the disease (intervention in depressive, dysphoric (irritable) and elevated mood episodes) 2. Enhancing adherence to drug treatment 3. Learning early signs and preventing episodes 4. Treatment of comorbid conditions.

Only interventions that are performed directly for BD treatment will be discussed, since the main focus of this review is the implementation of CBT in BD and due to the limitation regarding the volume of the study.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY

Although the standard treatments for BD invole somatic treatments such as medication and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), psychosocial treatments come to the forefront to obtain the ideal treatment goals in the case of well-being. In addition to medications, CBT is among the suggested evidence-based treatments, except for acute mania (8, 9). Regardless of the model used, psychoeducation is the most studied intervention and is recommended by almost all guidelines. Psychoeducation can be performed as a step of CBT in any phase, or it can be performed alone as an intervention to prevent recurrence in euthymic patients (10). Studies reveal that the six-session group psychoeducation protocols have an impact of preventing recurrence as much as longer individual CBT practices (11).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy protocols are mostly presented as protocols that include an average of 20 sessions followed by enhancement sessions. The evidence level of CBT for BD is lower compared to unipolar depression and psychotic disorders. The preventive effect of CBT seems to fade away in patients who have had multiple episodes, though it is effective in preventing recurrence (12). CBT is recommended in the second line in addition to drug therapy for all conditions except acute mania. It has been reported to be effective in the treatment of acute depression, in preventing recurrence, and in prolonging the period of remission (9). It has been demonstrated in 2017, in a meta-analysis, which involved 19 randomized controlled studies (RCTs) including a total of 1384 patients, that it increased psychological and social functionality (g=0.457; 95% CI=0.106-0.809) and decreased the severity of mania (g=−0.581; 95% CI=1.127 to −0.035) (13). Mindfulness-based CBTs, which are also considered as the third generation, are not suggested in the first-line since they have conflicting results (14).

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS

All CBT processes are fundamentally based on 4 steps: Assessment, psychoeducation, implementation of interventions (protocol), and relapse/recurrence prevention (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cognitive-behavioral treatment protocol

| Treatment stage The approximate number of sessions |

Sub-stages | Techniques and content |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment 1--2 sessions | Making a diagnosis | Employing semi-structured tools such as SCID, MINI |

| Symptom profile and severity assessment | Using symptom scales (such as BDI, YMRS) Creating a life chart |

|

| Creating formulation a biopsychosocial approach (25) | Establishing a holistic formulation that involves the environmental, emotional, physiological, behavioral and cognitive domains, and determining the factors and treatment goals related to each of them. | |

| Psychoeducation 1--2 sessions | Psychoeducation about the nature and symptoms of the disease | Giving information about the symptom, etiology, different stages, and treatment options of the disease |

| Narrating the treatment/therapy model through the formulation in the biopsychosocial framework established in the assessment phase | The interrelationship of environment, perceptions/thoughts, emotions, physiological reactions, and behaviors are discussed. What can be done about each part is determined. The power of the biological effect and the impact of medication should be underlined. It is discussed how thoughts and behaviors are amenable to change. | |

| Interventions 20-25 sessions * * Unlike other psychopathologies, the number of sessions cannot be limited in practice due to the nature of the disorder. |

Behavioral interventions | Efforts for behavioral activation during the depressive episode and behavioral inhibition during the manic or hypomanic episode are implemented in addition to increasing or decreasing the frequency of rewarding activities according to the polarity of the episode. |

| Cognitive interventions | Working through ruminations (particularly following the behavioral activation). Cognitive restructuring is conducted. It is aimed for the person to learn more realistic, appropriate and functional thinking. |

|

| Schema work | It is a continuation of cognitive interventions. Particularly, dysfunctional attitudes and dysfunctional core beliefs that lead the life of the individual are discussed. | |

| Skill development work | With an approach that mainly includes behavioral techniques, areas such as decision making, assertiveness, problem-solving, social skills, professional skills are studied. | |

| Relapse/recurrence prevantion 1--2 sessions | Compliance with medication | The individual’s beliefs and attitudes about the medications are discussed. |

| Identification of early signs | Functional coping plans are created by learning the early signs of both depressive and manic episodes. Techniques learned in the process are reinforced. | |

| Regulation of the daily rhythm | Awareness and self-management are studied in domains such as sleep, fatigue, and interpersonal relationships. | |

| Self-monitoring | Improving the person’s ability to look at their affective processes and behaviors from a distance. |

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale, SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, MINI: Mini International Neurology-Psychiatry Interview

Assessment

The assessment for the CBT for BD fundamentally shares the basic characteristics of the CBT assessment for all mental disorders. At this phase, it would be helpful both to clarify the diagnosis and to investigate additional diagnoses, if any (which is a must for BD, not an exception). For this purpose, the semi-structured interview for DSM-IV or DSM-5 (SCID) or mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI) may be preferred (15, 16).

The assessment interview is also a unique opportunity for that individual to get information about the context of the triggering factors in BD and how the episodes of illness affect the person’s relationship with the enviroment. The difficulties of patients in fulfilling their responsibilities in the depressive episode or how close relationships, occupational functionality and interpersonal relationships are affected during the manic or hypomanic episode should be learned. During episodes of hypomania and mania, the increase in goal directed activity (new attempts, rise in expenditures, increase in sexual and risky behaviors), their consequences, and the problems that arise should be noted down. Moreover, attention should be paid to patients’ comments on past experiences, and their attributions. Considerations regarding themselves or the outside world should be noted down when taking the history of the patient.

Scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (17) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (18) are used to assess the severity of episodes in BD and to monitor the severity of symptoms, and Cognitive Distortions Scale (CDS) (19), Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (20) and Social Comparison Scale (SCS) (21) are examples of scales useful for assessing the cognitive profile of the individual. The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS) can be used to assess the risk of suicide, particularly in depressive episodes (22, 23). Similarly, sentence completion tests (e.g. Beier sentence completion test) make a remarkable contribution for understanding the cognitive profile of the patient, albeit these tests are not developed for CBT (24). In addition to that, life charting gives us information about early symptoms and the general symptom profile with triggering factors, as well as its diagnostic benefit. When making a life chart, searching for the early signs is necessary, from the first assessment onward.

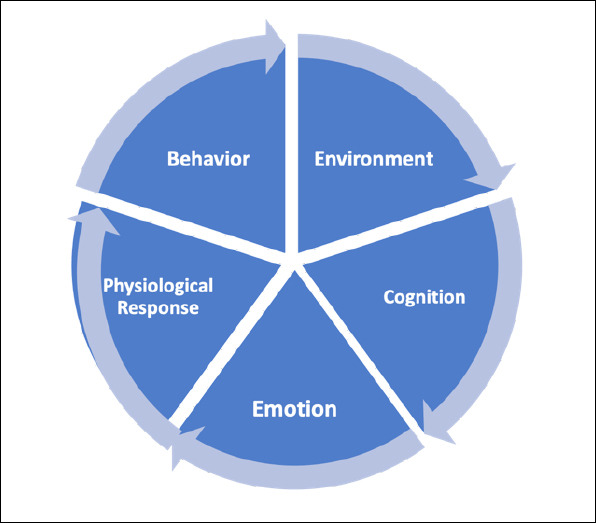

The special part of this whole evaluation process for CBT is the gathering of the necessary information to make the 5-area formulation based on biopsychosocial approach. These 5 areas can be summarized as follows:

Environment: the context in which the symptoms occur and the effects of the symptoms on the environment; Perception/thought: Individual’s thoughts (evaluation, attribution, comments and expectations) during the episodes or about the disorder; Emotion: depression, elevation, dysphoria, anxiety, sadness, anger etc.; Physiological responses : sleep, appetite, energy (cognitive symptoms such as inattention can also be assessed here or within the perception/thought area with a practical approach) and; Behaviors: behaviors that the individual tends to do under the influence of a certain period (e.g., increasing the amount time for travel, increasing alcohol use during the hypomanic episode), behavioral strategies used to cope with the mood (e.g. increasing the time spent in bed in depressive mood, social withdrawal) and information on their impact on the environment (eg, conflicts with the family or financial difficulties after expenditures during an episode of hypomania).

Psychoeducation

It should be highlighted that there are two primary components in this step. The first component involves explaining the symptoms of the disease, its bipolar nature, and giving general information about its etiology. At this stage, examples of other chronic illnesses that have a dominant biological basis but also have psycho-social components can be presented to enable the patient to look at the disease from outside and embody it. For instance, the effects of medications and behavioral changes in the treatment of diseases such as diabetes or hypertension are discussed. When working with the patient at this stage, it is suggested that the therapist sticks to the principles of motivational interviewing (26) (see 27 for detailed information).

Conveying the model: Making use of the information in the 5 areas we obtained in the previous stage, it is shared with the patient how these five factors interact with each other and what kind of model is suggested for change. The environment has an impact on perceptions and thoughts, and hence on emotions, physiological reactions, and behaviors. Emotion and physiological responses are internal processes that impact each other as well as perception and thought. We also influence the environment mainly through our behavior. However, there is also an aspect of the environment, which is independent of us. Our emotions and physiological responses are not directly under our control. However, these responses may change directly with methods such as medications, or indirectly with changes in the environmental domain, thought domain, or behavioral domain. Moreover, the form taken by each of these changes in the short and long run may differ from each other. For instance; the termination of a person’s employment contract is in the environmental domain and “I will not find such a job again; I was subjected to injustice” thoughts are elements in the domain of cognition, while unhappiness, anxiety, and anger are in the emotional domain and fatigue and exhaustion in the physiological response domain, not answering incoming calls and staying indoor and not going outside is an element in the domain of behavior. When we consider the above-mentioned interaction network, we can predict how these areas increase or decrease each other’s impact. For example, we know that behavior of staying indoor can reduce anxiety in the short term and increase unhappiness in the long term and reinforce the belief that they will not be able to find a job again (See. Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conveying the CBT model from biopsychosocial perspective.

Interventions

Behavioral interventions

Mood monitoring: It is a basic method in terms of ensuring that patients are aware of their mood changes before the application of many cognitive or behavioral techniques. Patients score their general moods for that day on the calendar days of the month and mark other emotions that may be significant, the amount of sleep, and whether they have taken their medication (Form 1). Mood monitoring plays a facilitating role in making other behavioral and cognitive interventions applicable to the patient during the process. Almost all BD-CBT protocols have this intervention (28). Patients may not always be willing to participate. Loss of motivation and negative expectations are among the reasons why patients in the depressive episode are not eager to do this, while in patients who are in the episode of hypomania/mania, not being able to give up reinforcing behaviors may be a reason for this situation (29).

Form 1.

Mood tracking chart for patients with Bipolar Disorder.

| Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mood | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 (Highest) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 (Moderate) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 (Lowest) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discomfort-Anger | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amount of sleep (hours) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Received medications (plus for those that are received) |

This document was prepared by Dr. Kadir Özdel and it can only be used after being cited.

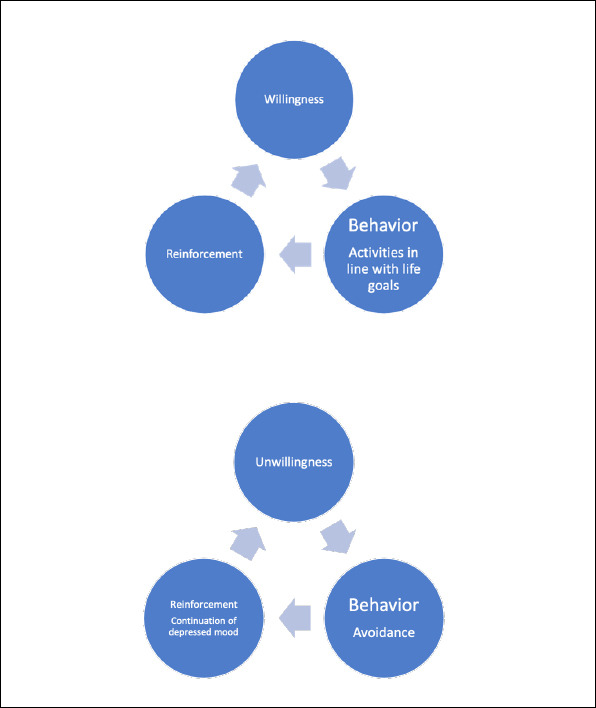

Activity planning interventions: Behavioral interventions in manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes are different from each other. These interventions originate from learning theories. According to the learning theory, if a reinforcement situation occurs after a behavior, the frequency of that behavior tends to increase (operant conditioning). In depression, behaviors that often have an avoidance function and can cause other problems in the long term are negatively reinforced with temporary relief, whereas, in mania or hypomania, behaviors that have significant long-term costs for the person are positively reinforced (30). In addition to this suggested model for unipolar depression, the model of behavioral activation and increase in response to reward, which was put forward by Depue et al. (31), explains mania and hypomania with the increase of the individual’s behavioral engagement.

Behavioral Interventions to be Applied in the Depressive Episode: In the depressive episode, as a result of the change in the daily life activities of the individual, both internal and external reinforcements decrease. Even, sometimes negative outcomes that serve as punishment are encountered such as the result of behaviors in social situations leading to anxiety symptoms. In this case, the individual reduces the level of activity. Typically, first the pleasurable activities and then the number of routine activities related to responsibilities begins to decrease. During this period, behaviors such as procrastination, social isolation, and staying in bed for a long time are negatively reinforced due to the temporary relief provided by these behaviors or the decrease in their distress. So the person enters into a cycle of depression(32) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Euthymic cycle and depressive cycle.

An activity schedule is used to perform this intervention in both depressive and manic periods. First of all, the person’s environment, mood and behaviors are monitored. The patient is asked to score between 0 (no pleasure) and 10 (the most pleasurable) for the pleasure received about the environment or the activity in a certain period. Moreover, mastery/achievement scoring between 0 (never achieved/did not reach its goal) and 10 (fully achieved/achieved its goal) is formed for the appropriate ones among these activities (Form 2). Primarily, behaviors that can be naturally reinforced and associated with pleasure are recorded to the table. If the patient does not have any disability, exercise in the form of brisk walking is the first activity to be included. Exercise has been shown to be associated with fewer depression symptoms, higher functionality, and quality of life, independent of other factors (33). In the next step, activities that are more likely to be reinforced (pleasurable) should be planned with the patient and included in the person’s daily life.

Form 2.

Activity Schedule

| In this chart, we ask you to score your life in two aspects for each day when you are active at certain times of the day (e.g., going somewhere) or in a passive behavior (e.g., being in the living room when a guest comes to visit). 1) If it is appropriate for that behavior or situation (e.g., eating), you should score between 0 (no pleasure) and 10 (most pleasurable) for that behavior or situation in terms of pleasure. 2) If it is appropriate for that behavior or situation (e.g., cleaning a room), you should give a score between 0 (never succeeded/did not achieve the goal) to 10 (most successful/achieved the goal) in terms of achieving the success/goal. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please fill in the chart as soon as possible when the event or behavior occurred. Give the points as you feel right at the moment. There is no absolute right or wrong scoring. | ||||||||

| Period | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

| Morning | Time: | |||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Afternoon | Time: | |||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Evening | Time: | |||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Night | Time: | |||||||

| Time: | ||||||||

| Time: : | ||||||||

This document was prepared by Dr. Kadir Özdel and it can only be used after being cited.

When the patient adapts to the above-mentioned (pleasure-oriented) activity plans, the activities that the patient has to do but has given up in the depressive episode are selected. In the euthymic period, these are generally the activities that are reinforced by accomplishing the person’s duties and responsibilities or the achieving the purpose of the activity rather than being pleasure-oriented activities. Two basic methods are functional for such domains of the activity or situations: Cascading and using problem-solving skills.

In cascading, the patient is asked to stage the activities first with the therapist, then alone. There should one step at a time with focusing only on that step. The weight of the therapist’s support can be adjusted at this step depending on the severity of the depressive symptoms. More contribution from therapist is needed for patients with severe loss of functionality.

During the depressive episode, problem-solving techniques are used for avoided situations that has to be dealt (34). Problem-solving practice should be conducted under the supervision of the therapist until each step is thoroughly understood, and then it should be included in the person’s activity program. Problem-solving skills consist of 6 steps: 1) identifying the problem, 2) brainstorming about all possible solutions regardless of their feasibility and difficulties 3) evaluating the pros and cons of solutions, 4) choosing one of the solution or solutions, 5) implementing the solution, 6 ) evaluating the results of the solution and altering the solution partially or completely.

Sleep-related behavioral interventions: During the depressive episodes, basic sleep hygiene rules are applied, but during the hypomania/manic periods, techniques that help increase the amount of sleep are used (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recommendations for sleep hygiene

| The measures that will make it easier for you to dose off and improve your sleep quality and quantity are listed below. Try to follow all the recommendations as much as possible. When you encounter a recommendation that has a negative impact on you, you can skip that recommendation. Conflicting recommendations should be implemented where appropriate. |

| Establish a routine for sleep. Sleep at a certain time in a certain place with clothes that will make you comfortable. This setting should be as isolated as possible in terms of sound, light, and other stimuli. |

| If you have trouble sleeping despite following the first recommendation, change your sleeping place and setting. Sleep in different beds for a few days. |

| Set a time for going to bed and getting out of bed, which is suitable for the physiology. Be strict at waking up at the time you planned to, even if you have slept a little. If your waking up time has shifted to the later hours of the day, you can do this by adjusting wake-up time gradually. |

| If you have spent a long time trying to sleep in bed, get up and do activities that will not stimulate you mentally and physically, then come back to bed again. Do not check the clock in the meantime. |

| Avoid stimulants such as tea or coffee, heavy exercise, or drinking alcohol in the evening. Albeit alcohol makes it easier to fall asleep, it adversely affects your sleep quality. |

| Do not use the bed for purposes other than sex and sleep. Do not take care of your daily routines in bed, do not watch TV. |

| Do not take naps (short light sleep breaks) during the day. |

| Prefer to sleep in a dark and slightly cool room, as it is known to increase melatonin secretion. |

| Do not ponder on insomnia and its consequences. |

| Stop accounting for what happened that day and making plans for what could happen tomorrow. If you need it, you can set a time zone that is not close to bedtime as a worry or plan time. (This period should not be longer than half an hour) |

Behavioral Interventions in Manic or Hypomanic Episode

The activity schedule can also be used effectively during hypomanic and manic episodes. Without a doubt, the behavior pattern in the depressive episode and the behavioral patterns in this period show quite different characteristics from each other. It may be beneficial to reduce activities that are rewarding for the person. In addition to this, the following behavioral suggestions are useful.

Increasing the amount of sleep: The decrease in the amount of sleep is both a sign of mania and a condition that affects the increase in mood. Thus, it should be ensured that the individual sleeps more than he/she thinks enough, close to the amount of sleep in the euthymic period. Some activities, such as going out at night and attending nightly entertainment, should be restricted on the schedule of activities, since they may delay the transition to sleep.

Tightening the money management: It is possible to make monthly and weekly budgets with the patient. It may be beneficial to take measures that restrain or slow down the individual’s access to financial resources. Obtaining the help of the people that the person trusts can be useful in restricting the purchases above a certain limit. Restrictive measures can be taken in the bank account for avoiding excessive spending. For these regulations to be effective, it may be necessary to continue the contact with the patient during the manic episode. Moreover, these interventions may need to be reapplied during each episode.

Slowing down important decisions: The patient is advised to make the decisions that are involving major financial and moral changes for her/his life only after getting enough sleep for two consecutive nights. Besides, before making a decision, the person is asked to consult at least two trusted person about that decision. The decision-making mechanisms of large companies or the peer-review system in scientific studies can be given as examples in explaining this process to the patient.

Slowing down impulsive behaviors: An individual with an elevated mood is asked to think for 5 seconds before acting when discussing or joking with others and visualizing two different consequences of that action. An example is trying to imagine a smiling reaction and a distressed reaction from the other person in response to a dirty joke.

Stimulus regulation: Avoidance of the stimuli that may be associated with elevated mood or dysphoria are detected from the person’s activity schedule or the information he/she gives us is the goal. These triggers may be certain places, people, or situations. These stimuli can be related with a certain friend, a work done in a certain field such as writing an article, writing a project or a can be a physiological state like hunger or fatigue.

Behavioral Methods in the Remission Period

Mindfulness training and relaxation techniques: Both practices can be used for all periods of BD except severe and acute exacerbations of mania and depression. Mindfullness is mostly aimed at increasing the ability to look at internal experiences from the outside, while relaxation techniques are useful in controlling physical tension and dysphoria (35). In addition, meta-cognitive techniques can be used to reduce the vulnerability of the person for certain images that are disturbing or that may affect mood elevation (36).

Cognitive interventions

Cognitive interventions are not suitable for situations where the depressed or elevated mood is very severe. Care should be taken, since it may increase the feeling of inadequacy and rumination, particularly in the presence of severe depression (37). Schema theory provides the basis for cognitive therapy. Schemas are cognitive structures that regulate the perception and attention, enable information processing, and influence emotion and behavior. Instant thoughts and images originate from these schemas embedded in the memory system. Schemas that are activated by biological and environmental factors shape cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses. Emotional and behavioral responses to the situation, person, or internal stimulus in a given context are regulated by the cognitive system (38). In the process of working with thoughts, the interventions that can be made for the cognitive systems at reflexive and reflective levels are different. The reflexive thinking is a system that responds faster but uses fewer data sources, whereas a reflective system is slower but uses more data and produces more comprehensive output (39). For this purpose, the basis of cognitive techniques is recognizing thoughts, establishing a connection with emotion and behavior, and testing the beliefs. The individual would learn to handle the thoughts in the mind in terms of reality/rationality, appropriateness, and functionality, and to produce more realistic, appropriate, and functional alternatives for this situation.

Examining the Evidence : It is conducted in three stages.

1) The “data” that supports the idea of the individual is noted down: Objectivity is not necessary at this stage. The reason why the individual thinks so and the preconceptions that support this belief are asked.

2) The “supporting evidences” are noted down: At this stage, the objectivity of the patient’s belief is discussed. What would the decision be if this situation was assessed by an objective observer with the objective data available? To strengthen the objective view, the person assesses the thoughts through someone familiar or through the “court room” metaphor.

3) The evidences against the current belief is investigated: In this section, Socratic questioning is used to reveal information, which the person cannot remember or synthesize due to cognitive bias. A comprehensive thought analysis form is used (Form 3). Before giving this form, it should be discussed in the light of these principles during the session.

Form 3.

Thought record and survey form

| Event Place-time | Emotions/physiological reactionsIntensity (0-100) | Triggered thoughts Level of Convincing (0--100) | Behavior that is wanted/performed | Rationality test | Appropriateness test | Functionality test | Alternative thought & behavior | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What exactly is the internal or external event that happened? What would be perceived by an eye or camera seeing this event for the first time, and what would a device measure? E.g., my heart is beating fast and loudly (internal event) My friend said he/she can’t go out with me tonight (external event) |

Are there bodily sensations/senses you are feeling? How can you describe this most objectively? For instance, tremors, shaking, sweating, muscle contractions in the stomach, fatigue. How are you feeling emotionally? Sad, joyful, excited, uncomfortable, anxious, fearful, enthusiastic, etc. Give a score for both groups, rating “0” for the lowest intensity of this emotion or feeling and “100” for the highest intensity. |

What do these situations and these feelings mean? What does this situation mean for you? What does it indicate about the future? What kind of person does it show you? What kind of situation does it show you? How convincing does this thought sound to you right now? “0” is not convincing at all. “100” is strongly convincing. |

If you haven’t done anything about this situation yet, what do you want to do? What would you usually do in such a situation? What did you do regarding this situation? |

Among the thoughts in the second column, which one is the most influential on your feelings and behavior? 1.Why does this thought seem convincing to you (write down all the ideas that come to mind) 2. Is there any objective evidence that this thought to be true? For example, can this data be used as an evidence in a court of law? 3. Is there any data that suggests that your opinion may not be accurate? What would someone you trust present as an evidence against this situation? (No matter how convincing this data is to you, focus on how objective it is). |

Does this thought (in the third column) adequately account for the current situation? If you were an inspector and you were asked to prepare an objective report on this situation, what would you write in the report? Keep in mind that there may not be a single truth to explain this situation. Again, if there were a council made up of people you trust in such a situation, what kind of a statement would they make if they made a joint statement to explain this situation? | What kind of a situation does this thought drive you to? What kind of behavior does it bring along? What could be the function and consequence of this thought as it is? Would you advise someone you are responsible for to think this way? How much influence do you think this thought has in your behavior or do you want to behave this way (fourth column)? What are the short and long-term effects of this behavior? What would you recommend to the person whose care and protection you are responsible for doing? |

What could be realistic alternatives for this situation? How can one behave as an alternative? How do you behave to test the rationality, appropriateness, and functionality of this idea? |

How are you feeling emotionally right now? What would be the outcome if you have behaved differently? What did you infer from these outcomes? |

This document was prepared by Dr. Kadir Özdel It can only be used after being cited.

The cognitive domain consists of negative beliefs about the self, environment, and future during a depressive episode. Negative thoughts have the themes that the individual is unlovable, inadequate, and malevolent. Moreover, there may be beliefs that both medication and psychotherapy will not be effective during this period. Feelings of despair and hopelessness negatively affect patients’ compliance with treatment. Despair and hopelessness have priority in both drug therapy and psychotherapy interventions, since they are associated with the risk of suicide (40). During an episode of mania or hypomania, there may be unrealistic positive beliefs about the self, the world, and the future, such as “I am better than anyone else”, “I can do whatever I want”, “From now on I will be strong and energetic”. In addition to these, there may be beliefs that the disorder can be overcomed by own “willpower” or that there is no need for medications. Accordingly, the relevant beliefs are addressed in the light of the above-mentioned principles.

Working with repetitive thinking patterns (Ruminations and Worry): Rumination is defined as a repetitive thinking style about the past, the present, and worry about the future. Emotionally, it is often associated with sadness, anger, and dysphoria. A repetitive thinking style has also been reported to be present during the manic episode of BD (41). From a cognitive perspective, what the individual does is engaging in a detailed thinking process on the same subject within a self limited cognitive system without considering new data. Although the triggering of this thought process is automatic, the voluntary reactions of the individual are important for perseverance of the process. Regarding the management of the repetitive thought process, the cognitive strategies such as trying to find a response to the thought, trying to think positively, or trying to suppress the thought, and behavioral strategies such as withdrawal, self-isolation, assurance seeking from others constitute the targets of the intervention. Many patients find it difficult to understand the influence/control they have on their thoughts (thought processes). The emergence of a certain thought or image in the mind is an uncontrollable element of the thought process. Although the individual effortlessly goes through this thought process, voluntary actions occur in order to avoid the emotion created by this thought or to cope with the situation or consequences indicated by the thought. Most of the time, this voluntary behavioral process is accompanied by voluntary cognitive activity. The goal of cognitive intervention is to ensure that this mental (cognitive) activity is problem-solving and healthy. When conducting these interventions, either the individual is helped to develop one’s own perspective and hence use more data, or the person is encouraged to refrain from the worry and rumination process that is not expected to reach any results.

Cognitive interventions for repetitive thinking are basically meta-cognitive. Metacognitive beliefs are divided into three groups:

A) Beliefs that repetitive thinking is uncontrollable, B) Beliefs that repetitive thinking is dangerous (such as that this process will harm the person physically or mentally, causing to become sick or mad) C) Beliefs that repetitive thinking is useful (one can solve the problem by extended thinking, satisfactory and beliefs that he/she will be able to reach a lasting solution, that he/she will ultimately be relieved).

In the intervention phase, these beliefs are dealt within the above-mentioned order. The behavioral experiment perspective is used both in the session and in the real-life practice (42). The implementation of the behavioral activity in combination with the relevant meta-cognitive techniques enhances its effectiveness. When working with repetitive thoughts, it would be helpful to use a chart, just as when working on behaviors (Form 4).

Form 4.

Repetitive thought work out form

| Date Time | What is the intrusive thought that first initiated repetitive thinking? - Question - Image |

The content of repetitive thought -What were the central issues in the worry/rumination process? |

How long did your repetitive thinking process take? | What are your feelings about the subject you are thinking about? | What was your reaction while thinking? -What have you done to control thinking? -How did you handle your other activities while you were thinking? |

Result How was your level of distress affected? -Have you reached a concrete decision or tangible outcome? How was your motivation in terms of problem-solving? |

This document was prepared by Dr. Kadir Özdel and it can only be used after being cited.

Working with Schemas: There is a mutual interaction of genetic and environmental factors in the formation of schemas (38). Individuals with BD are more likely to have experienced negative life events compared to individuals without this disorder (43). The cause and effect relationships of negative life events and trauma are considerably complex. Genetic traits, family environment, and attachment problems are some of the factors involved in this interaction. Working with the patient’s schemas may provide additional benefit, particularly when there are ongoing challenges in interpersonal relationships (44).

Interventions for Relapse Prevention

This stage of the process should focus on two domains. First is to reinforce the newly learned cognitive and behavioral techniques; with application by the patient for similar situations. For this reason, a summary of the treatment process is made, so to speak. It would be appropriate to make emergency planning for further challenging situations in this domain. In this emergency planning includes determining the situations in which help from relatives are needed as well as the planning work which should be done alone. These measures may be simple measures such as giving control of the credit card to the management of a spouse during the hypomanic episode, or the application of a technique such as asking for help from an appropriate friend for increasing the level of activity in the depressive episode.

The second domain is efforts aimed at preventing recurrence. To prevent a recurrence, it would be appropriate to provide specific psychoeducation at the end of the treatment process. Primary goal of this step is to learn the early signs of mood episodes and to develop appropriate coping strategies for these early signs. Especially the patients with a recent onset of illness may have less awareness. The therapist should focus on potential early signs by using the information from the literature and their own clinical experience. Improvement of the patient’s ability to receive help and feedback from his relatives for the domains related to recurrence prevention and early signs would be beneficial as in the part of reinforcing useful interventions. In the early stages, the therapist can acquire information from collateral sources by obtaining the patient’s permission in order to understand the personal characteristics of the patient.

CONCLUSION

On the one hand, it is suggested that the lifetime prevalence of subthreshold cases in BD ranges between 4% and 6%, but on the other hand, there is a discussion of the potential problems that may be caused by overdiagnosis (45, 46). Even in the best scenario, only a small percentage of the diagnosed patients can achieve the desired treatment goals with regular use of an effective medication (47). CBT is an evidence-based, important adjuvant method to address non-compliance with medications, partial response to treatment, or cognitive, occupational, and social loss of functionality (13). It is recommended for the prevention of depressive or manic episodes, for increasing treatment compliance, for the treatment of comorbid substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, or sleep disturbance in the euthymic period and for acute treatment of depression (8, 9, 48).

The CBT process includes assessment, psychoeducation, and methods for mood episodes or preventing recurrences. Psychoeducation is the most crucial and the most evidence based module of the process, both at the beginning of the therapy process and at the stage of relapse prevention (10). All patients should be provided some or all of this process according to their needs and compatibility. Psychoeducation in a style of CBT would be much more effective than lecturing. CBT is both a therapeutic and a user-friendly tool, as it is based on learning theories. Its practice is based on this theoretical background and good treatment relationship. Besides, as it is based on an empirical approach since beginning, it can easily incorporate new developments into its structure.

Although we have not reached the best point we targeted in BD, CBT is one of the approaches that will provide the clearest contribution to the goal of relieving the suffering of patients and improving their lives.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed

Author Contributions: Concept – KÖ, AK, MHT; Design – KÖ, AK, MHT; Supervision – KÖ, AK, MHT; Resources – (-); Materials – (-); Data Collection and/or Processing – (-); Analysis and/or Interpretation – KÖ, AK, MH; Literature Search – KÖ, AK, MHT; Writing Manuscript – KÖ, AK, MHT; Critical Review – KÖ, AK, MHT.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure: All co-authors declare that there is no financial interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Provencher MD, Hawke LD, Thienot E. Psychotherapies for comorbid anxiety in bipolar spectrum disorders. J Affect Disord. 2011;133:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation (WHO). International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)-10. 2010 https: //www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICD10Volum|ne2_en_|y2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub. 2013 https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rihmer Z, Angst J. Aydın H, Bozkurt A, editors. Duygudurum Bozuklukları: Epidemiyoloji. Türkçe: Kaplan &Sadock's Comprehensive Text Book of Psychiatry. 2007;8:1575–1582. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michalak EE, Yatham LN, Lam RW. Quality of life in bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:72. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer M, Andreassen OA, Geddes JR, Vedel Kessing L, Lewitzka U, Schulze TG, Vieta E. Areas of uncertainties and unmet needs in bipolar disorders: clinical and research perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:930–939. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fountoulakis KN, Vieta E, Young A, Yatham L, Grunze H, Blier P, Moeller HJ, Kasper S. The International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-|y2017), Part 4: Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and Recommendations for Future Research. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:196–205. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyw072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Laws KR. NICE guidance on psychological treatments for bipolar disorder: searching for the evidence. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:386–388. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, Sharma V, Goldstein BI, Rej S, Beaulieu S, Alda M, MacQueen G, Milev RV, Ravindran A, O’ Donovan C, McIntosh D, Lam RW, Vazquez G, Kapczinski F, McIntyre RS, Kozicky J, Kanba S, Lafer B, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, Vieta E, Malhi G, Post RM, Berk M. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD)2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97–170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colom F, Vieta E. Psychoeducation manual for bipolar disorder: Cambridge University Press. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parikh SV, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Yatham LN, Young LT, Patelis-Siotis I, Macqueen GM, Levitt A, Arenovich T, Cervantes P, Velyvis V, Kennedy SH, Streiner DL. A randomized controlled trial of psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety treatments (CANMAT) study [CME] J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:803–810. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66–72. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08r04559yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang K-J, Tsai J-C, Liu D, Lin C-H, Chiu H-L, Chou K-R. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS one. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176849. e0176849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xuan R, Li X, Qiao Y, Guo Q, Liu X, Deng W, Hu Q, Wang K, Zhang L. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113116. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.First MB. Structured clinical interview for the DSM (SCID). The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. Wiley Online Library. 2015:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9881538/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbauch J. Beck depression inventory (BDI) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Covin R, Dozois DJ, Ogniewicz A, Seeds PM. Measuring cognitive errors: Initial development of the Cognitive Distortions Scale (CDS) Int J Cogn Ther. 2011;4:297–322. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissman A, Beck A. Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy. Chicago, IL: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allan S, Gilbert P. A social comparison scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;19:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozcelik HS, Ozdel K, Bulut SD, Orsel S. The reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (Turkish BSSI) Clin Psychopharmacol B. 2015;25:141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1979;47:343–352. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beier H, Hanfmann E. Emotional attitudes of former Soviet citizens, as studied by the technique of projective questions. J Abnorm Psychol. 1956;53:143–153. doi: 10.1037/h0041706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu CS, Stubbs B, Chen TY, Tang CH, Li DJ, Yang WC, Wu CK, Carvalho AF, Vieta E, Miklowitz DJ, Tseng PT, Lin PY. The effectiveness of adjunct mindfulness-based intervention in treatment of bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unützer J, Operskalski B. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:500–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otto MW, Reilly-Harrington N, Sachs GS. Psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral strategies in the management of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2003;73:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burns DD, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Coping styles, homework compliance, and the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:305–311. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimidjian S, Barrera Jr M, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Depue RA, Krauss SP, Spoont MR. A two-dimensional threshold model of seasonal bipolar affective disorder. In: Magnusson D, Öhman A, editors. Psychopathology: An interactional perspective (Personality, Psychopathology, and Psychotherapy) 1st ed. Academic Press; 1987. pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Türkçapar H. Depresyon; Klinik uygulamalarda bilişsel davranışçıterapi. Ankara: HYB Basım Yayın; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melo MCA, Daher EDF, Albuquerque SGC, de Bruin VMS. Exercise in bipolar patients: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;198:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray SM, Otto MW. Psychosocial approaches to suicide prevention: applications to patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 25):56–64. https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11765098/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovas DA, Schuman-Olivier Z. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes EA, Arntz A, Smucker MR. Imagery rescripting in cognitive behaviour therapy: Images, treatment techniques and outcomes. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatr. 2007;38:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: Longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:339–352. doi: 10.1037/a0031994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Haigh EA. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck AT, Warman DM. Amador XF, David AS, editors. Cognitive insight: theory and assessment. Insight and psychosis: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and related disorders. (2nd ed) 2004;2:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Modif. 2008;32:77–108. doi: 10.1177/0145445507304728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McEvoy PM, Hyett MP, Ehring T, Johnson SL, Samtani S, Anderson R, Moulds ML. Transdiagnostic assessment of repetitive negative thinking and responses to positive affect: Structure and predictive utility for depression, anxiety, and mania symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:375–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, Ritzler BA. Impact of childhood abuse on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:121–125. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawke LD, Provencher MD, Parikh SV. Schema therapy for bipolar disorder: A conceptual model and future directions. J Affect Disord. 2013;148:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell PB. Bipolar disorder: the shift to overdiagnosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57:659–65. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, Viana MC, Andrade LH, Hu C, Karam EG, Ladea M, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y. bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gitlin MJ, Miklowitz DJ. The difficult lives of individuals with bipolar disorder: A review of functional outcomes and their implications for treatment. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raglan GB, Swanson LM, Arnedt JT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with medical and psychiatric comorbidities. Sleep Med Clin. 2019;14:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]