Abstract

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disorder that affects behavioral, affective, and cognitive domains and consists of positive and negative psychotic symptoms. Antipsychotic therapy is the first-line treatment for schizophrenia. However, treatment adherence levels are low. Even if there is good treatment compliance, residual symptoms and treatment resistance can be seen. As a result, recent schizophrenia treatment guidelines suggest Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) as adjunctive to antipsychotic therapy. CBT is known effective, especially on positive symptoms. This paper aims to review CBT practices and their effectiveness in schizophrenia.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, cognitive, behavioral, psychotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder characterized by chronic and repetitive psychosis. Generally, signs and symptoms of schizophrenia are grouped as positive (delusion, hallucinations, disorganized behavior, and speech) and negative (reduced affect, alogia, loss of motivation, asociality, etc.). It is known that disruptive changes and symptoms appear in many domains of schizophrenia such as behaviors, emotions, and cognitive functions (1).

The first choice of treatment in schizophrenia is antipsychotic medications. Only about 30% of the patients using antipsychotic drugs are satisfied with the treatment in the first 18 months; the remaining patients either discontinue or change their treatment during this period. (2). It was reported that in patients with compliance to treatment, there were ongoing positive or negative symptoms close to 50%, and resistance to treatment is around 20–30%. (3). Although the effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs over positive symptoms is well known, their effectiveness in areas that remain in the background but strong determinants of the general functionality such as negative and cognitive symptoms are still controversial (4) the authors reviewed the findings published to date by searching PubMed with the keywords negative symptoms, antipsychotics, antidepressants, glutamatergic compounds, monotherapy and add-on therapy and identifying additional articles in the reference lists of the resulting publications. The findings presented here predominantly focus on results of meta-analyses. Evidence for efficacy of current psychopharmacological medications is difficult to assess because of methodological problems and inconsistent results. In general, the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs. Also, the side effects of antipsychotic drugs affect the patients’ quality of life negatively and disrupt treatment compliance. For this reason, current treatments in schizophrenia include psychotherapeutic approaches in addition to antipsychotic medication. Psychotherapeutic approaches can be divided into individual (supportive, social skill therapies, etc.), group, and cognitive-behavioral techniques in general. (1).

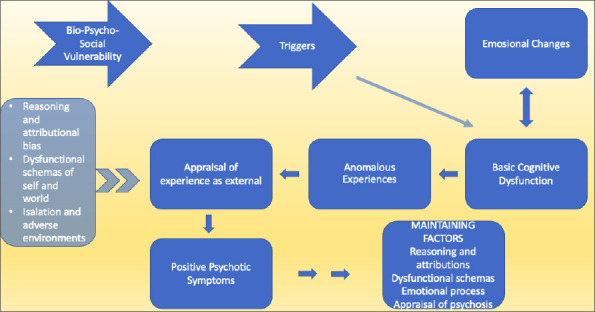

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for psychotic disorders (CBTp) interventions started to spread in the 1980 s. Before that, schizophrenia was considered only as a medical illness, and psychological factors were ignored. (5). With the emergence of the “stress-vulnerability” model, it has been suggested that schizophrenia is not only a disorder with a biological origin, but it occurs from the interaction between biological and psychosocial factors. The vulnerability may be due to biological origin (e.g., genetics), innate psychological characteristics, or social conditions in the intrauterine/early developmental stages. Also, stress can be biological (e.g., infection), psychological, or social (6). During the period following the “stress-vulnerability” model, the focus was shifted from “psychotic syndrome” to “psychotic symptoms” (7), and CBTp models were developed (8) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cognitive behavioral model of positive psychotic symptoms (Garety, 2001).

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

In recent studies, CBTp was utilized for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general functionality, prodromal stage, individuals at risk for the development of psychosis and for comorbid psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder. (9–11). Meta-analyzes showed that CBTp had a low to medium efficiency. The effect size of CBT for positive psychotic symptoms was estimated as 0.31 in a meta-analysis when compared to the group receiving standard treatment (12), and another meta-analysis reported it as 0.37 (13), e.g., in groups. Aim: To explore the effect sizes of current CBTp trials including targeted and nontargeted symptoms, modes of action, and effect of methodological rigor. Method: Thirty-four CBTp trials with data in the public domain were used as source data for a meta-analysis and investigation of the effects of trial methodology using the Clinical Trial Assessment Measure (CTAM. In another meta-analysis that analyzed delusions or hallucinations individually instead of positive psychotic findings, the effect size of CBT for hallucinations was 0.44, and CBT effect size for delusions was 0.36 with comparison to control group (14). A following meta-analysis reported CBT effect size for negative symptoms as 0.44 (13) eg, in groups. Aim: To explore the effect sizes of current CBTp trials including targeted and nontargeted symptoms, modes of action, and effect of methodological rigor. Method: Thirty-four CBTp trials with data in the public domain were used as source data for a meta-analysis and investigation of the effects of trial methodology using the Clinical Trial Assessment Measure (CTAM. In a recent meta-analysis, it was stated that CBTp was effective over general psychopathology and positive symptoms; however, its effect on negative symptoms was not clear (15). It should be noted that negative symptoms were generally assessed as secondary therapy targets in studies (16). A meta-analysis including 34 CBTp studies showed an effect of 0.35–0.44 on positive and negative symptoms, functionality, mood, and social anxiety (13). Contradicting results about the effect size of the CBTp can be explained by the differences in treatment protocols, applied CBTp models, session frequency or intensity, target symptoms, and individual (acute-chronic period) differences (17).

When the impact of schizophrenia and the scarcity of evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches are considered, importance of CBTp can be recognized. Hence, nowadays, all schizophrenia treatment guidelines recommend CBTp (17). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis reported that CBT’s effectiveness in treating delusions increased between years 1998 and 2018 (16). This finding may be related to the development of more effective therapy models or the training of more competent psychotherapists with better understanding of mechanisms underlying psychotic disorders. Either way, the results are promising.

RAPPORT BUILDING, ADAPTATION AND INTRODUCING THE MODEL IN COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

What to say and how to say are more important in CBT for schizophrenic patients when compared to other psychiatric patient groups. If we take the wrong step, it will be more difficult for us to test the reality of psychotic symptoms. Although the general features of CBT such as empathy, sincerity, and unconditional acceptance are also valid for patients with schizophrenia, general knowledge and expertise about the psychotic experiences of these patients are required. Correct and proper word choice is crucial in this patient group. We should not engage in any discourse or behavior that would devaluate the psychotic experiences of schizophrenic patients. Confronting the patient with his delusional belief may disrupt the relationship, treatment compliance and sometimes even strengthen the delusional belief. Rather than telling a patient who has the delusional belief that his spouse cheated on him or this belief is not valid, stating that such a possibility exists, but there are also other possibilities which we can test the situation together would be a more appropriate approach. It should be determined which situations and subjects make the patient feel more troubled, and the patient should be provided with the necessary support in these cases. Understanding and formulating psychotic experiences can be complex, especially during initial assessments. Evaluating the patient’s history, schemes and beliefs altogether will facilitate the formulation. The word ‘schizophrenia’ should not be avoided, patient’s concerns of the schizophrenia diagnosis should be listened and accurate information should be provided. It will be helpful to explain the stress-vulnerability model and situations that may lead to psychosis (e.g., sleep and stimulus deprivation, trauma) (18).

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR HALLUCINATIONS

The sensory perceptions, which are real sensations but occur without any stimulus for the relevant sensory organ, are defined as hallucinations. In schizophrenia, the most common hallucinations are in the auditory type (approximately 70%). Auditory hallucinations are also seen in psychiatric disorders other than schizophrenia and around 15% of the normal population. Therefore, they are now considered as transdiagnostic (19). In studies that compared auditory hallucinations in psychotic patients and normal populations, no difference was found between the two groups in terms of gender, identity, frequency, duration, intensity, location (inside/outside of the head), and content (20). The reason that auditory hallucinations were more distressing in psychotic patients when compared to the normal population was found to be related to the psychotic patients’ evaluation of voices as dangerous and uncontrollable (21). It was reported that psychotic patients evaluate voices as more malicious, they try to resist, leading to an increase in the frequency of the voice and worsening depression (22, 23). For example, hearing the voice of a deceased person after the death of a loved one can be evaluated as positive (“still with me”) or expected (“I’m in a difficult period”). But if the voice is thought to be from a malicious outside source that may cause harm (“the devil is talking to me”), the patient’s reaction can be very different.

CBT interventions for auditory hallucinations:

Elaboration of sounds: Whose voice? Where does it come from? How many voices are there? Where do they appear? How do they talk? How does the person respond to the voice? How strong does he think the voice is? What does this sound mean for the person? What is he doing to deal with the voices? How does it start? How often does it occur? How long does it take?

Psycho-education and normalization: The patient may think that hearing voices is strange or stupid and may not want to talk about it. The knowledge that auditory hallucinations can occur in many situations such as stressful life events, insomnia, grief, trauma, social isolation, physical illness, and drug use may prevent the patient from assessing voices negatively and reduce their anxiety and loneliness.

ABC model: In the time the patient experienced the voices, what exactly the voice said (A), the patient’s thoughts about the voice (B), and what the patient feels and does when he hears the sound? (C) Such kind of experiences are formulated (Table 1). The patient may be asked to make a list.

Patient’s beliefs such as that they have no control over voices (“Nothing can destroy them.”), voices are strong (“I have to do whatever they say.”), voices are external (“Voices are voices of external forces.”) and whether the voices are believable (“Voices know everything about me.”) are examined using socratic questioning (guided discovery). Evidence for and against the patient’s beliefs are inspected, the patient may be asked to evaluate these beliefs through the eyes of another person, and alternative explanations are created. During the therapy, patient’s belief level is assessed.

Avoidance and safety-seeking behaviors that support/strengthen the beliefs of the patient are discussed.

Simple coping strategies can be created: distracting attention, such as listening to music, walking, or focusing on what voices are saying and taking notes to investigate them.

Table 1.

ABC model example for auditory hallucinations

| A– Situation– Voices | B– Automatic thoughts | C– Emotions | C– Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|

| After fighting with mother, hearing the voice ‘stab her’ | I am a dangerous person | Sadness, anger | Does not leave the room |

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR DELUSIONS

Delusions are false beliefs that are not generally accepted by other members of the culture and subculture and that arise from the misinterpretation of experiences or perceptions, which are kept despite clear counter-evidence and contrary to what almost everyone else believes. In the past, it was thought that psychotic symptoms such as delusions were qualitatively different from typical experiences and cannot be explained by normal reasoning and learning mechanisms. Epidemiological studies conducted later showed that normal and psychotic experiences are in a continium, and common mechanisms of reasoning can play a role in forming and maintaining delusional beliefs (24) CBTp is recommended by national guidelines for all patients with schizophrenia. However, although CBTp was originally developed as a means to improve delusions, meta-analyses have generally integrated effects for positive symptoms rather than for delusions. Thus, it is still an open question whether CBTp is more effective with regard to change in delusions compared to treatment as usual (TAU. As a matter of fact, it has been shown that 47% of the population have paranoid ideas (25), and 66–79% of them have paranormal beliefs (26).

Cognitive biases which can be defined as deviations in the processing, selection, and evaluation of information, are thought to play a role in the development of psychotic symptoms, particularly delusions (27). Cognitive biases are not pathological; even self-serving attribution bias or unrealistic optimism has been associated with “feeling good”. Some cognitive biases were reported to be related to delusional thought formation (28). These are:

Jumping to conclusion bias: It can be defined as a tendency to make quick decisions despite the lack of sufficient evidence. Usually, the probability is evaluated by reasoning tests. It was detected with a frequency around 60% in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. It was associated with the presence of delusions rather than schizophrenia diagnosis, and it was thought to play a role in the development of delusion (29). Also, its presence in individuals with a tendency towards delusions shows that situations such as general cognitive deficiency in schizophrenia and being under psychotropic treatment are not effective in the emergence of this bias, and this bias is present before delusions appear (30).

Bias against disconfirmatory evidence: Despite contradictory information and evidences against the belief, the individual maintains the belief. This bias is thought to be effective in the sustention of the delusion (29).

Need for closure bias: It can be defined as the need to make quick decisions in order to get an answer or to get rid of the uncertainty. It is thought to be effective in delusion formation (30).

Overconfidence bias: It has been shown that patients with schizophrenia are overconfident with their decisions and predictions. This is usually evaluated with memory tests (31).

Attributional biases: Externalization; can be defined as attributing personal meanings to unrelated external events and external causes to internal psychological or bodily events. Personalization; can be defined as the bias of holding people responsible for adverse events, not circumstances. Intentionality; is the bias to think that an external factor is trying to affect the person positively or negatively. The ability to predict, explain, and interpret the behavior, thoughts, and intentions of others is referred to as the theory of mind. Attribution biases have been explained with false beliefs about the tendencies and behaviors of others due to the deficits in theory of mind (32).

Delusions are known to consolidate over time and are closely related to biographical or situational factors (31). For example, although the precursors for persecutory delusions are difficult to detect, the beginning is usually with fear or anxiety. The steps in delusion formation can be exemplified as follows: The patient frequently listens to news about an organization against the state, and the thought that their colleagues may also be from this organization increases the worry, thinking that they might want to harm the patient who is not in this organization (attribution bias). The patient focuses on the behavior of their friends (threat monitoring) and thinks that they are using certain words to send a message, this is followed by becoming uncomfortable with the gaze (jumping to conclusion bias). Increasing anxiety is interpreted as an evidence that others really want to harm (emotion-based bias). After seeing a friend from work on the subway, the patient becomes convinced about the thought (settling of delusion).

CBT interventions for delusions:

Identifying Antecedents: Two different approaches can be used: 1) Direct approach: Trying to get information directly with questions such as “When did you first think about this?” 2) Personal history taking: Developmental history, family history, clinical records, reports, prescriptions, discharge reports, doctor’s notes, etc.

-

Assessing Delusion: It is important to evaluate delusion in 5 areas;

- Content (What is happening?)

- Formation of delusional thinking-Reasoning (How is it happening?)

- Explanation (Why is it happening?)

- Expectation (Where will this end up, and what will be the result?)

- Response-action (What will he do about it?)

Delusional belief level: We can evaluate at four levels: 1st level) Delusion is now absent but happened in the past, and the patient now admits that it was wrong, 2nd level) His delusion is now non-existent, but he accepts that what had happened was real, 3rd level) Delusion continues, but the patient does not act according to the delusion, 4th level) Believes the delusion absolutely and behaves accordingly (32). Therapist should accept the situation in patients who initially lack insight. It is necessary to work with the patient by accepting this without trying to change it. Focusing on the distress experienced by the patient or trying to alleviate the fears and interpersonal problems caused by the delusion may be enough.

The ABC model is helpful for working through the relationship between the thoughts and our emotions and behaviors (Table 2). Reviewing the evidence and the alternative explanations can be used. In addition, thinking on delusional content can be described, and treating these thoughts only as thoughts with distancing them could be of use.

Questioning one’s beliefs with behavioral experiments can be a more effective way of learning.

Avoidance and safety-seeking behaviors that support or strengthen patient’s beliefs should also be discussed.

Table 2.

ABC Model Example for Delusions

| A– Triggering Event | B– Belief | C– Result |

|---|---|---|

| Colleagues talking to each other | They are talking about me and planning something | Leaves the room, isolates themselves |

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS FOR NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS

Negative symptoms are divided into two main groups: avolition-apathy (amotivation, anhedonia, asociality) and reduced expression (verbal and non-verbal). (33). Negative symptoms that occur due to the neurobiology of schizophrenia are defined as primary, and those that arise due to factors such as medications, delusions, hallucinations or depression and social isolation are defined as secondary negative symptoms (34). In secondary negative symptoms, interventions aiming at the underlying cause are necessary (such as psychoeducation on medications, CBT for psychotic symptoms or depression). Deficits in the neurocognitive domain are seen in schizophrenia, such as attention, memory, executive functions, and social cognition and these have been associated with the presence of more severe negative symptoms (35). Negative symptoms also have psychological and cognitive components. Patients generally have negative self-assessments, low expectations for success or pleasure, low expectations due to stigma or awareness of their already limited cognitive abilities (32).

It has been shown that patients with negative symptoms actually enjoy when they participate in an activity. The reason for not participating in the activity is the belief that they will not enjoy it. Having difficulties with completing the work due to the difficulty in focusing or inadequacy in executive functions results in a lack of motivation for even simple tasks. The reason that patients describe themselves as unsuccessful and worthless is because the diagnosis of schizophrenia magnifies the existing difficulties. Deficiencies in cognitive functions also lead to dysfunctional beliefs (36) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Negative expectation evaluations in negative symptoms (Rector, 2003)

| Evaluations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs | Low expectations of success | Low expectations of pleasure | Low expectations of acceptance | Limited cognitive abilities |

| Flat affect | If I show my emotions, other people will see that I am inadequate. | I don’t feel like usual. | My face looks hard and crooked. | I have no ability to express my feelings. |

| Alogia | I will not find the right words to express myself. | It will take me too long to get to the point I want, boring. | My voice will sound strange, stupid, or different. | It takes a lot of effort to talk. |

| Avolition | Why should I try, I’m going to fail. | Not worth the try, very difficult. | It’s best not to participate at all. | It takes a lot of effort to try. |

Working with patients with negative symptoms can be difficult due to the lack of speech or difficulty expressing their feelings, and lack of motivation.

The cognitive approach in negative symptoms is similar to the one in depression and anxiety disorders; Socratic questioning, thought recording, identification of autonomic thoughts, evidence analysis, alternative explanation creation, cognitive restructuring, and revision of schemes.

Behavioral activation: Simple activities (such as walking in the garden or going to the market) can be planned with the therapist for increasing the patient’s activity level. Planning too complicated activities may reduce the patient’s chances of success.

The activity schedule consists of the patient’s scoring (between 0 to 10) the level of liking and finding himself successful in the daily work throughout the week. This chart will reduce patient’s likelihood to forget tasks which they enjoyed or found themselves successful until the therapy session. This will also prevent them from finding these tasks not worthwhile over time because of their negative beliefs.

Creating a staged task structure allows more realistic planning for the goals of the patient. The aim is increasing the cognitive competence of the patient step by step.

Social skills training can be given for affective participation.

CONCLUSION

CBTp’s purpose is to eliminate the distress caused by psychotic experiences or at least enable the patient to cope with this distress, rather than completely curing the patient. Therefore, it should be kept in mind that CBTp can also be used for delusions which are resistant to antipsychotic treatment. It has been shown that CBTp is more effective in individuals with a low constancy of belief and with more flexible beliefs, good insight, and a shorter duration of illness. CBTp interventions for negative symptoms are relatively new compared to positive symptoms. Studies in this area will clarify the effectiveness of CBTp and will also improve the patients’ general functionality. Future studies which will be conducted in the field of CBTp should consider treatment planning according to the subgroups (e.g., divided by the level of neurocognitive impairment or disease severity) with better structuring of treatment protocols, and clear goals including long-term results.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed

Conflict of Interest: No.

Financial Disclosure: All authors declare that there is no financial interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, Atkinson D. Schizophrenia: Overview and treatment options. P T. 2014;39:638–645. https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4159061/pdf/ptj3909638.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RSE, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conley RR, Buchanan RW. Evaluation of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23:663–674. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Möller H-J, Czobor P. Pharmacological treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265:567–578. doi: 10.1007/s00406-015-0596-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brockman R, Murrell E. What Are the Primary Goals of Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Psychosis?A Theoretical and Empirical Review. J Cogn Psychother. 2015;29:45–67. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.29.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zubin J, Spring B. Vulnerability –a new view of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1977;86:103–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentall R. Deconstructing the concept of schizophrenia. J Ment Heal. 1993;2:223–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Freeman D, Bebbington PE. A cognitive model of the positive symptoms of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2001;31:189–195. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowak I, Sabariego C, Switaj P, Anczewska M. Disability and recovery in schizophrenia: a systematic review of cognitive behavioral therapy interventions. BMC Psychiatry [Internet] 2016;16:228. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0912-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tavares S. Severe Mental Disorders from a Cognitive-Behavioural Perspective: A Comprehensive Review from Conceptualization to Intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2017;13:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callcott P, Standart S, Turkington D. Trauma within psychosis: Using a CBT model for PTSD in psychosis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2004;32:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws KR. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. Br J Psychiatry [Internet] 2014;204:20–29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Schizophrenia: Effect Sizes, Clinical Models, and Methodological Rigor. Schizophr Bull [Internet] 2008;34:523–537. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Gaag M, Valmaggia LR, Smit F. The effects of individually tailored formulation-based cognitive behavioural therapy in auditory hallucinations and delusions: A meta-analysis. Schizophr Res [Internet] 2014;156:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polese D, Fornaro M, Palermo M, de Luca V, Bartolomeis A. Treatment-Resistant to Antipsychotics: A Resistance to Everything?Psychotherapy in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia and Nonaffective Psychosis: A 25-Year Systematic Review and Exploratory Meta-Analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:210. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sitko K, Bewick BM, Owens D, Masterson C. Meta-analysis and Meta-regression of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp) Across Time: The Effectiveness of CBT has Improved for Delusions. Schizophr Bull Open [Internet] 2020;1 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Candida M, Campos C, Monteiro B, Rocha N, Paes F, Nardi A, Machado S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an overview on efficacy, recent trends and neurobiological findings. Med Express. 2016;3:M160501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turkington D, Kingdon D. Using a normalising rationale in the treatment of schizophrenic patients. In: Haddock G, Slade PD, editors. Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions with Psychotic Disorders. London and New York: Routledge; 1996. pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters F, Allen P, Aleman A, Fernyhough C, Woodward TS, Badcock JC, Barkus E, Johns L, Varese F, Menon M, Vercammen A, Larøi F. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia populations: a review and integrated model of cognitive mechanisms. Schizophr Bull [Internet] 2012;38:683–693. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumeister D, Sedgwick O, Howes O, Peters E. Auditory verbal hallucinations and continuum models of psychosis: A systematic review of the healthy voice-hearer literature. Clin Psychol Rev [Internet] 2017;51:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill K, Varese F, Jackson M, Linden DEJ. The relationship between metacognitive beliefs, auditory hallucinations, and hallucination-related distress in clinical and non-clinical voice-hearers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2012;51:434–447. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2012.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrew EM, Gray NS, Snowden RJ. The relationship between trauma and beliefs about hearing voices: a study of psychiatric and non-psychiatric voice hearers. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1409–1417. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700253X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor G, Murray C. A qualitative investigation into non-clinical voice hearing: what factors may protect against distress? Ment Health Relig Cult [Internet] 2012;15:373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehl S, Werner D, Lincoln TM. Does Cognitive Behavior Therapy for psychosis (CBTp) show a sustainable effect on delusions?A meta-analysis. Front Psychol [Internet] 2015;6:1450. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellett L, Lopes B, Chadwick P. Paranoia in a Nonclinical Population of College Students. J Nerv Ment Dis [Internet] 2003;191:425–430. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000081646.33030.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross CA, Joshi S. Paranormal experiences in the general population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:357–358. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moritz S, Vitzthum F, Randjbar S, Veckenstedt R, Woodward TS. Detecting and defusing cognitive traps: metacognitive intervention in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:561–569. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32833d16a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yilmaz AE, Gencoz T, Wells A. Psychometric characteristics of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and Metacognitions Questionnaire-30 and metacognitive predictors of worry and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a Turkish sample. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15:424–439. doi: 10.1002/cpp.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SauvéG, Lavigne KM, Pochiet G, Brodeur MB, Lepage M. Efficacy of psychological interventions targeting cognitive biases in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev [Internet] 2020;78:101854. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juárez-Ramos V, Montánchez Torres M. Cognitive Biases in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. In: Shen YC, editor. Schizophrenia Treatment-The New Facets. Croatia: InTech; 2016. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moritz S, Ramdani N, Klass H, Andreou C, Jungclaussen D, Eifler S, Englisch S, Schirmbeck F, Zink M. Overconfidence in incorrect perceptual judgments in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn [Internet] 2014;1:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck A, Rector N. Cognitive Approaches to Schizophrenia: Theory and Therapy. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millan MJ, Fone K, Steckler T, Horan WP. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: clinical characteristics, pathophysiological substrates, experimental models and prospects for improved treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:645–692. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batinic B. Cognitive Models of Positive and Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia and Implications for Treatment. Psychiatr Danub. 2019;31:181–184. http: //www.psychiatria-danubina.com/UserDocsImages/pdf/dnb_vol31_noSuppl%202/dnb_vol31_noSuppl%202_181.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant PM, Beck AT. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull [Internet] 2009;35:798–806. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarin F, Wallin L. Cognitive model and cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: an overview. Nord J Psychiatry. 2014;68:145–153. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.789074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]