Abstract

Twenty-two isolates of St. Louis encephalitis (SLE) virus of various geographical origins (Brazil, Argentina, Panama, Texas, Missouri, Maryland, California, and Florida) were examined for genetic variation by the base excision sequence scanning (BESS T-scan) method. A fragment was amplified in the envelope gene with the forward primer labeled in the PCR. The BESS T-scan method determined different clusters according to the profiles generated for the isolates and successfully grouped the isolates according to their geographical origins. Two major clusters, the North American cluster (cluster A) and the South and Central American cluster (cluster B), were defined. Two subgroups, the Texas-California subgroup (subgroup A1) and the Missouri-Maryland-Florida subgroup (subgroup A2), were distinguished within group A. Similarly, group B strains were subclustered to a South American subgroup (subgroup B1) and a Central American subgroup (subgroup B2). These results were consistent with those obtained by DNA sequencing analysis. The ability of the BESS T-scan method to discriminate between strains that present with high degrees of nucleotide sequence similarity indicated that this method provides reliable results and multiple applications for other virus families. The method has proven to be suitable for phylogenetic comparison and molecular epidemiology studies and may be an alternative to DNA sequencing.

St. Louis encephalitis (SLE) virus is a member of the genus Flavivirus within the family Flaviviridae. On the basis of its antigenic reactivity, SLE virus has been placed in the Japanese encephalitis serogroup. First isolated in Missouri in 1933, SLE virus has been responsible for approximately 5,000 officially reported human cases of infection in the United States since 1955 (16). SLE virus has been isolated from various species of Culex mosquitoes and birds. In tropical America, SLE virus has also been isolated from many non-Culex mosquito species. The case-fatality ratio for human disease is variable depending on the geographical location (16). Thus, the epidemiology of SLE virus still needs to be clarified, although a recent report has helped to clarify the mechanisms of viral persistence and transmission in nature (9). Since the earliest days of virology, typing of viruses has been an important tool for the characterization of viral populations and for the study of their epidemiology. Typing provides information on the relationships among isolates within the same group, species, or genus. Historically, serological methods have been used to identify antigenic differences among virus populations. Increasingly, nucleotide or deduced amino acid sequence data have largely replaced serology as a means of providing more sophisticated epidemiological information. However, most molecular methods other than DNA sequencing, such as PCR-based techniques, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and ribotyping, either are not suitable for viruses or provide data that are too weakly discriminative for typing purposes.

Although sequencing is still the preferred method, it is an expensive and time-consuming technique, especially when large numbers of samples need to be processed. Thus, other molecular methods that are easier and less expensive to perform would be useful for typing of virus isolates for epidemiological studies.

Recently, base excision sequence scanning (BESS) has been used to detect and localize point mutations in mammalian genes (6). The PCR product, which is amplified with one labeled primer and a dUTP-containing nucleotide mixture, is then enzymatically treated with a combination of uracil-N-glycosylase and endonuclease IV. The resulting nested labeled fragments are then separated on a standard sequencing gel and are detected by fluorescent dye detection.

We report here the results of studies in which we evaluated the usefulness of BESS for the detection of genetic variations in virus populations and for phylogenetic analysis. We have applied this technique to characterization and strain comparison of 22 isolates of SLE virus from various geographical locations in the Americas and have compared the results with those obtained by direct PCR sequencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SLE virus strains.

The SLE virus strains used in this project were part of a larger phylogenetic study based on comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the envelope gene. The 22 SLE virus isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1 by strain, source, geographical location, year of isolation, GenBank accession number, and identification code used in the phylogenetic trees. Each virus strain was inoculated onto a confluent Vero cell monolayer, and virus and cells were incubated for 3 to 5 days at 37°C in 25-cm2 flasks until a 3+ cytopathic effect was evident. Following passage in Vero cells, a stock of each isolate was prepared and stored at −70°C until the time of RNA extraction.

TABLE 1.

SLE virus isolates used for BESS T-scan and sequencing analyses

| Year of isolation | Strain | Source | Location | Denomination in this study | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | GML902612 | Hemagogus equinus | Panama | PAN-73/1 | AF112375 |

| 1973 | GML902613 | Hemagogus equinus | Panama | PAN-73/2 | AF112376 |

| 1973 | GML900968 | Unknown | Panama | PAN-73/3 | AF112377 |

| 1977 | GML902991 | Mansonia dyari | Panama | PAN-77/1 | AF112378 |

| 1977 | GML902984 | Mansonia dyari | Panama | PAN-77/2 | AF112379 |

| 1977 | GML903050 | Mansonia dyari | Panama | PAN-77/3 | AF112380 |

| 1983 | GML903797 | Sentinel chicken | Panama | PAN-83 | AF112381 |

| 1983 | GML903699 | Sentinel chicken | Panama | PAN-81 | AF112382 |

| 1978 | 78V6507 | Culex pipiens | Argentina | ARG-78 | AF112383 |

| 1971 | BeH203235 | Human | Brazil | BRA-71 | AF112384 |

| 1960 | BeAr23379 | Sabethes belisarioi | Brazil | BRA-60 | AF112385 |

| 1966 | CorAn9124 | Calomys musculinus | Brazil | BRA-66 | AF112386 |

| 1967 | CorAn9275 | Mus musculus | Argentina | ARG-67 | AF112387 |

| 1933 | Parton | Human | Missouri | SL-33 | AF112388 |

| 1937 | Hubbard | Human | Missouri | SL-37 | AF112389 |

| 1977 | Fort Washington 4 | Culex pipiens | Maryland | MAR-77 | AF112390 |

| 1979 | FL79-411 | Culex nigripalpus | Florida | FLO-79 | AF112391 |

| 1950 | BFS508 | Unknown | California | CAL-50 | AF112392 |

| 1970 | BFN1324 | Culex tarsalis | California | CAL-70 | AF112393 |

| 1966 | TD6-4G | Culex pipiens | Texas | TEX-66 | AF112394 |

| 1962 | Barnett | Unknown | California | CAL-62 | AF112395 |

| 1968 | 68V1587 | Culiseta inornata | Texas | TEX-68 | AF112396 |

RNA purification and reverse transcription procedure.

For RNA extraction, stock material was thawed, and 200 μl was removed and mixed with 600 μl of Trizol LS reagent (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). Following incubation at room temperature for 5 min, 200 μl of chloroform was added, and the materials were mixed and incubated again for 5 min. The aqueous phase was separated by centrifugation, and the RNA was precipitated from the solution by addition of an equal volume of isopropanol. RNA was recovered by centrifugation and was resuspended in 50 μl of sterile, RNase-free water.

Oligonucleotide primers.

Primers were designed on the basis of the sequence of SLE MSI-7 (Genbank accession no. M16614) with the MacVector program (Oxford Molecular Group, Oxford, England). Primers were designed to amplify a 750-bp portion of the 5′ half of the envelope gene. The sequence of the forward primer (primer F880) is 5′-GATTGGATGGATGCTAGGTAG-3′ and represents nucleotides 880 to 901. The sequence of the reverse primer (B1629) is 5′-GGTTCAAGTCGTGAAACCAGTC-3′ and represents nucleotides 1629 to 1608.

Reverse transcription.

Five microliters of RNA was mixed with 15 pmol of the reverse primer (primer B1629) in a total reaction volume of 12.7 μl. The mixture was heated to 70°C for 5 min to denature the secondary structure in the RNA and was then cooled to 20°C for primer annealing. Reverse transcription was performed by adding 7.3 μl of reverse transcription buffer so that each reaction mixture contained 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 20 mM dithiothreitol, and 60 Units of Superscript II (Gibco BRL). Synthesis of cDNA was performed by incubation at 42°C for 1 h. The reverse transcriptase was denatured at 95°C for 5 min. PCR amplification was performed immediately following cDNA synthesis.

PCR protocol.

Five microliters of the reverse transcription reaction mixture was transferred to 40 μl of 1× PCR buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 0.1% Triton X-100, each nucleotide at a concentration of 200 μM, and 200 pmol of each primer). The solution was overlaid with 50 μl of sterile mineral oil, and the samples were heated to 80°C. While the tubes were held at 80°C, 10 μl of 1× PCR buffer containing 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was added to each tube. The samples were amplified on a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, Mass.) by the following program: denaturation at 92°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 56°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 2 min for 25 cycles, followed by a 7-min final extension at 72°C. The complete PCR product from the complete 50 μl was purified with the Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega) and was stored at −20°C.

BESS product amplification.

Two microliters of a 1:50 dilution of the purified PCR product was used as the target DNA for amplification on a PTC-100 thermocycler (MJ Research) in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Promega), 1.5 mM (final concentration) MgCl2, 2 μl of BESS T-scan dNTP Mix with each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 2.5 mM and 200 μM dUTP (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.), 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega), 3 pmol of 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled forward primer (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.), and 3 pmol of a reverse primer. The amplification cycles were identical to those mentioned above. All products of the reverse transcription-PCRs were revealed by UV transillumination after electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide to verify that only the specific band had been amplified.

Assembly of the excision and cleavage reaction.

Eight microliters of PCR product containing dUTP was mixed, on ice, with 1 μl of BESS T-scan 10× excision enzyme buffer, 0.5 μl of BESS T-scan excision enzyme mixture, and 0.5 μl of sterile water (Epicentre). This mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped by heating at 95°C for 2 min. The BESS T-scan excision enzyme mixture contains uracil N-glycosylase (UNG) and endonuclease IV. UNG hydrolyzes the uracil-glycosidic bond (base excision) at a dU-containing DNA site, releasing uracil and creating an alkali-sensitive apyrimidic site in the DNA (4). Endonuclease IV specifically cleaves the phosphodiester bond 3′ to the abasic site, generating a defined series of fragments (13). The amplification of the target with the 6-FAM-labeled primer allows detection of the nested fragments that result from the excision reaction.

Gel electrophoresis.

Two microliters of the excision and cleavage reaction mixture was mixed with 2 μl of formamide and 0.5 μl of the fluorescent dye-labeled GS500 size marker (Perkin-Elmer), and the mixture was heated at 95°C for 2 min and then quickly cooled on ice. Two microliters was loaded onto a standard sequencing gel (6 M urea, 4.8% PAGE-PLUS; Amresco, Solon, Ohio), and the gel was run for 4 h on a ABI Prism 377XL automated sequencer (Perkin-Elmer).

Data collection.

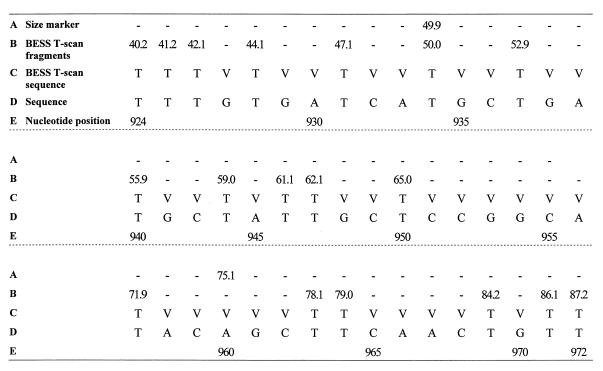

The fluorescence-labeled nested PCR fragments were separated according to their size by gel electrophoresis, detected as peaks by the fluorescent dye, and sized by determination of comigration with the size marker. The analysis of the resulting profiles was performed with Genotyper, version 2.0, software (Perkin-Elmer). Fragments smaller than 25 nucleotides were detected concurrently with the remaining labeled primer and resulted in a scrambled signal. For the PCR fragments larger than 210 nucleotides, the signal decreased and several labeled fragments were not detected. Therefore, the analysis was done only with the BESS T-scan fragments between nucleotides 924 and 1105 (numbered after strain MSI-7; GenBank accession no. M16614). The results were provided in a spreadsheet format in which labeled fragments were ordered by size and were converted into a sequence-like format, which was amenable to analysis with phylogenetics software. The sequence-like data were constructed by replacing each detected fragment with a T. Nucleotides other than T, potentially A, C, or G, were identified as V, the code for a non-T nucleotide according to the nomenclature for the identification of redundancies (see Fig. 2). The data were analyzed with the MEGA software program (10) by using the Jukes-Cantor algorithm and the neighbor-joining method. The robustness of the resulting branching patterns was tested by bootstrap analysis with 500 replications.

FIG. 2.

BESS T-scan profile analysis of fragments detected with Genotyper, version 2.0, software (rows A and B) and the binary sequence (row C) used for phylogenetic analysis. A, size of the marker that comigrated with the sample; B, each value corresponds to the size of a BESS T-scan fragment; C, the binary sequence was deduced from the BESS T-scan fragments (each detected fragment corresponds to a T base); D, DNA sequence of isolate SL-33; E, nucleotide positions are numbered relative to the MSI-7 strain (GenBank accession no. M16614); −, absence of the detected fragment; V, nucleotide A, C, or G.

Determination of the nucleotide sequences of the 22 SLE virus strains.

The PCR products amplified from the virus isolates listed in Table 1 were sequenced directly with the F880 and B1629 primers on a ABI Prism 377XL automated sequencer with BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit with Amplitaq FS (Perkin-Elmer). Nucleotide sequences located between positions 924 to 1604 (681 nucleotides) were used to perform phylogenetic analysis.

RESULTS

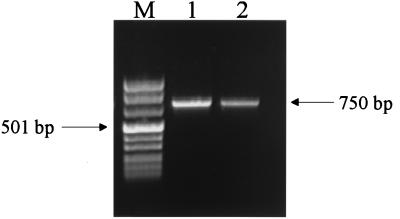

The PCR products obtained by the standard protocol and by the BESS T-scan protocol are presented in Fig. 1. The results of the conversion of the primary data (BESS T-scan fragments) into a binary sequence suitable for phylogenetic analysis and comparison of virus isolates are presented in Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

RT-PCR amplification of SLE virus SL-33. Lane M, Marker VIII (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany); lane 1, PCR product obtained by the standard protocol (with each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM); lane 2, PCR product obtained by the BESS T-scan protocol (each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 2.5 mM and 200 μM dUTP).

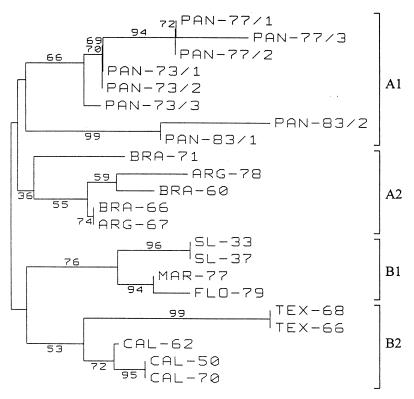

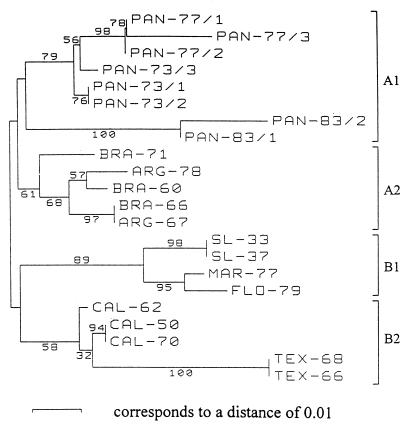

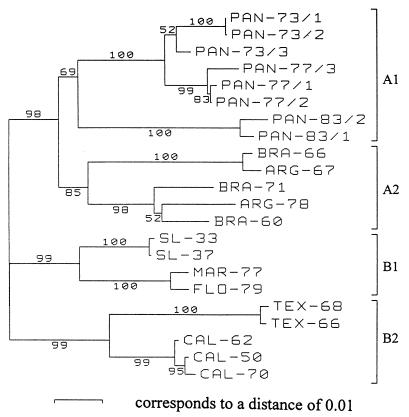

Phylogenetic trees based on the 182-nucleotide fragment analyzed by the BESS T-scan method (Fig. 3) and from analyses of 182- and 681-nucleotide sequences (Fig. 4 and 5, respectively) are presented in Figures 3, 4, and 5, respectively. Regardless of the method (the BESS T-scan method or nucleotide sequencing), the 22 isolates formed four groups on the basis of their geographical origins.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of SLE virus isolates based on a 182-nucleotide fragment between nucleotides 924 and 1105 (numbered after strain MSI-7 [GenBank accession no. M16614]) located in the envelope gene by BESS T-scan technique. Distances and groupings between the 22 isolates were determined by the Jukes-Cantor algorithm and neighbor-joining method with the MEGA software program (10). Bootstrap values are indicated and correspond to 500 replications.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of SLE virus isolates based on a 182-nucleotide DNA sequence between nucleotides 924 and 1105 (numbered after strain MSI-7 [GenBank accession no. M16614]) located in the envelope gene. Distances and groupings between the 22 isolates were determined by the Jukes-Cantor algorithm and neighbor-joining method with the MEGA software program (10). Bootstrap values are indicated and correspond to 500 replications.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of SLE virus isolates based on a 681-nucleotide DNA sequence between positions 924 to 1604 (numbered after strain MSI-7 [GenBank accession no. M16614]) located in the envelope gene. Distances and groupings between the 22 isolates were determined by the Jukes-Cantor algorithm and neighbor-joining method with the MEGA software program (10). Bootstrap values are indicated and correspond to 500 replications.

Eight Panamanian isolates form a clade designated group A1, and five South American isolates form group A2. Group A1 isolates were subgrouped according to the year of isolation, but the case group A2 isolates were not subgrouped. The two Panamanian isolates recovered in 1981 and 1983 are very divergent from the isolates recovered in 1973 and 1977 (6.1 to 6.9% distance in a pairwise comparison of nucleotide sequences). This divergence was identified by both BESS T-scan and sequence analyses.

North American isolates were divided into two groups: group B1, which included four isolates recovered from Missouri, Maryland, and Florida, and group B2, which contained five isolates from California and Texas. They were clearly grouped according to their geographical origins, regardless of the year of isolation. The robustness of these groupings was confirmed by the high bootstrap values, which ranged from 69 to 100%, obtained for each of the four groups in Fig. 5. The same groupings were obtained when the DNA sequences were trimmed to 182 nucleotides; the bootstrap values were lower. Bootstrap values from the results obtained by the BESS T-scan method were variable and ranged from 36 to 76% for the same four groups. The bootstrap values obtained from BESS T-scan data (Fig. 3) are lower than those obtained from nucleotide sequence analysis (Fig. 4 and 5). Nevertheless, the groupings of the three 1977 and the two 1983 Panamanian isolates, SL-33 and SL-37, MAR-77 and FLO-79, TEX-68 and TEX-66, and CAL-50 and CAL-70 are supported by high bootstrap values (94 to 99%) in Fig. 3.

DISCUSSION

Historically, epidemiological typing of virus isolates has been performed by serological techniques. Molecular techniques can provide a powerful approach to epidemiological typing because of their ability to detect minor genetic changes not reflected by serology tests. DNA sequencing is currently the “gold standard” in the molecular analysis of viruses. However, DNA sequencing of RNA viruses, especially viruses that are difficult to culture, remains expensive, time-consuming, and sometimes, technically challenging. A highly purified product is required for direct sequencing, and in some cases sequencing must be preceded by cloning and subcloning procedures.

Viruses, because of their small genome size and in many cases their RNA content, are not easily typed by such methods as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of DNA macrorestriction fragments or PCR-based techniques (random amplification of polymorphic DNA, repetitive extragenic palindromic element-based PCR, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-based PCR, or PCR-ribotyping). Recently, viruses have been typed by various techniques used as alternatives to DNA sequencing (1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 17–21, 23–25). Most of these involve PCR amplification followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, single-strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, cleavase fragment length polymorphism (CFLP; Third Wave Technologies, Madison, Wis.), and heteroduplex migration analysis (HMA).

The SSCP and HMA techniques have successfully been used for genotype characterization of hepatitis C virus (11) and for epidemiological studies of parvovirus B19, enterovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus type 1, influenza virus, and bunyaviruses (1, 5, 8, 12, 17, 19, 25).

By RFLP analysis, the choice of enzymes used for restriction digestion needs to be based on the comparison of a large number of sequences to be reliable, and thus, RFLP analysis is more frequently applied to highly studied viruses. However, even in this favorable case, only relatively short genomic regions (sequences of from a few to 20 bases) are investigated for mutations. Additionally, when isolates are closely related, specific distinguishing restriction patterns can rarely be determined.

CFLP has recently been used for hepatitis C virus genotype determination (14), and seems to be a promising technique, but as for the SSCP and HMA techniques, precise localization of the mutations is not possible. Moreover, the pattern provided presents many bands, and computerized analysis may be required when numerous isolates are investigated. The RFLP, SSCP, and HMA techniques allow analysis of DNA sequences longer than those that can be analyzed by BESS T-scanning, but because quantitative data are not collected, they are not suitable for phylogenetic analysis. Mutation mapping cannot be achieved by HMA or SSCP analysis, and both techniques need to be optimized to provide reliable results. CFLP and RFLP provide a more precise localization of the mutations, but neither method indicates the nature or the exact position of the mutations. Finally, most of these methods cannot be used for phylogenetic analysis because of the paucity of quantitative data that they generate. Moreover, in none of these techniques do the resulting patterns consistently correlate with the nucleotide sequences of the isolates under study.

The BESS T-scan method is a rapid and powerful method for the detection and precise localization of 95% of the mutations in mammalian genes (6). With only one labeled primer, this method can distinguish all the thymidine mutations; thus, 6 of 12 theoretically possible mutations can be detected. The patterns are virtually identical to a T lane sequencing ladder, which represents the banding profile of dUTP incorporation during PCR amplification.

In the study described here, we evaluated the BESS T-scan method as a tool to study the molecular epidemiology of SLE virus isolates recovered in the Americas. We compared the ability of the BESS T-scan method to that of direct sequencing to identify genetic variation among the isolates and to provide phylogenetic data. The 22 isolates have been correctly assigned to distinct groups according to their geographical origins, despite pairwise nucleotide distances of less than 10.2% (data not shown) between isolates belonging to distinct groups. The lower bootstrap values obtained by the BESS T-scan method compared to those obtained from analysis of a 681-nucleotide sequence may reflect the fact that a shorter fragment has been analyzed and that BESS T-scan data consist of binary results (V or T), whereas traditional nucleotide sequence data (A, C, T, or G) do not. Interestingly, the bootstrap values observed for the sequences analyzed by sequencing of the 182-nucleotide sequence and BESS T-scan analysis are not very different.

The results indicated that SLE virus isolates from homogeneous genetic groups depending on their geographical origins, which is in agreement with the results reported by others (2, 9, 15, 22). Pairwise nucleotide distances observed between isolates from distinct geographical areas were similar to those reported previously (9).

Compared to nucleotide sequence data, the results obtained by the BESS T-scan method demonstrate its capability to discriminate between closely related virus strains and thus its usefulness for epidemiological and phylogenetic studies. Although not yet tested, the BESS T-scan method has the potential to be used for genetic comparison of viral strains involved in clinical outbreaks of viral diseases such as rotavirus, cytomegalovirus, and hepatitis C virus infections to help investigate their epidemiology. Further studies with more data and others viruses are necessary to confirm the potential of the BESS T-scan method to be an alternative to DNA sequencing for epidemiological and phylogenetic analyses of viral populations.

In conclusion, any viral population that presents with variability similar to that observed for SLE virus and that can be amplified with primers is a candidate for study of its phylogenetic makeup and its molecular epidemiology by application of the BESS T-scan technology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Robert E. Shope and Sophie Le Pogam for critical review of the manuscript and to Doug Norris and Bill Sweeney for help with the BESS T-scan and sequencing experiments.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI-10984) and from the John Sealy Memorial Endowment Fund for Biomedical Research. R.N.C. is partly supported by grants from the French Foreign Affairs Ministry (Bourse Lavoisier) from Servier Laboratories and from The Philippe Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black W C, Vanlandingham D L, Sweeney W P, Wasieloski L P, Calisher C H, Beaty B J. Typing of LaCrosse, snowshoe hare, and Tahyna viruses by analyses of single-strand conformation polymorphisms of the small RNA segments. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3179–3182. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3179-3182.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowen G S, Monath T P, Kemp G E, Kerschner J H, Kirk L J. Geographic variation among St. Louis encephalitis virus strains in the viremic responses of avian hosts. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:1411–1419. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delwart E L, Shpaer E G, Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Grez M, Rubsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins J I. Genetic relationships determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan B K. DNA glycosylases. In: Boyer P D, editor. The enzymes. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1981. pp. 565–586. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujioka S, Koide H, Kitaura Y, Duguchi H, Kawamura K. Analysis of enterovirus genotypes using single-strand conformation polymorphisms of polymerase chain reaction products. J Virol Methods. 1995;51:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)00112-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins G A, Hoffman L M. Base excision sequence scanning. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:803–804. doi: 10.1038/nbt0897-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katayama Y, Shibahara K, Kohama T, Homma M, Hotta H. Molecular epidemiology and changing distribution of genotypes of measles virus field strains in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2651–2653. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2651-2653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerr J R, Curran M D, Moore J E, Erdman D D, Coyle P V, Nunoue T, Middleton D, Ferguson W P. Genetic diversity in the non-structural gene of parvovirus B19 detected by single-stranded conformational polymorphism assay (SSCP) and partial nucleotide sequencing. J Virol Methods. 1995;53:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00017-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer L D, Presser S B, Hardy J L, Jackson A O. Genotypic and phenotypic variation of selected Saint Louis encephalitis viral strains isolated in California. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:222–229. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis, version 1.02. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lareu R R, Swanson N R, Fox S A. Rapid and sensitive genotyping of hepatitis C virus by single-strand conformation polymorphism. J Virol Methods. 1997;64:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(96)02134-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J C, De B K, Lin S C. Rapid and sensitive genotyping of Epstein-Barr virus using single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of polymerase chain reaction products. J Virol Methods. 1993;43:233–246. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd R S, Linn S M. Nucleases involved in DNA repair. In: Linn S M, Lloyd R S, Roberts R J, editors. Nucleases. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 263–316. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall D J, Heisler L M, Lyamichev V, Murvine C, Olive D M, Ehrlich G D, Neri B P, de Arruda M. Determination of hepatitis C virus genotypes in the United States by cleavase fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3156–3162. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3156-3162.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monath T P, Cropp C B, Bowen G S, Kemp G E, Mitchell C J, Gardner J J. Variation in virulence for mice and rhesus monkeys among St. Louis encephalitis virus strains of different origin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:948–962. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monath T P, Heinz F X. Flaviviruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 961–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novitsky V, Arnold C, Clewley J P. Heteroduplex mobility assay for subtyping HIV-1: improved methodology and comparison with phylogenetic analysis of sequence data. J Virol Methods. 1996;59:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(96)02014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawlotsky J M, Pellerin M, Bouvier M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Germanidis G, Bastie A, Darthuy F, Remire J, Soussy C J, Dhumeaux D. Genetic complexity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of hepatitis C virus (HCV): influence on the characteristics of the infection and responses to interferon alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1998;54:256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters T, Schlayer H J, Hiller B, Rosler B, Blum H, Rasenack J. Quasispecies analysis in hepatitis C virus infection by fluorescent single strand conformation polymorphism. J Virol Methods. 1997;64:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(96)02144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritacco V, Di Lonardo M, Reniero A, Ambroggi M, Barrera L, Dambrosi A, Lopez B, Isola N, de Kantor I N. Nosocomial spread of human immunodeficiency virus-related multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Buenos Aires. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:637–642. doi: 10.1086/514084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saitoh-Inagawa W, Oshima A, Aoki K, Itoh N, Isobe K, Uchio E, Ohno S, Nakajima H, Hata K, Ishiko H. Rapid diagnosis of adenoviral conjunctivitis by PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2113–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2113-2116.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trent D W, Monath T P, Bowen G S, Vorndam A V, Cropp C B, Kemp G E. Variation among strains of St. Louis encephalitis virus: basis for a genetic, pathogenetic, and epidemiologic classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1980;354:219–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb27969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Belkum A, Juffermans L, Schrauwen L, van Doornum G, Burger M, Quint W. Genotyping human papillomavirus type 16 isolates from persistently infected promiscuous individuals and cervical neoplasia patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2957–2962. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2957-2962.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou S. A practical approach to genetic screening for influenza virus variants. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2623–2627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2623-2627.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou S, Stansfield C, Bridge J. Identification of new influenza B virus variants by multiplex reverse transcription-PCR and the heteroduplex mobility assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1544–1548. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1544-1548.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]