Key Points

Question

Following new price transparency legislation, what are the availability, usability, and variability of standard reported prices for ophthalmologic procedures?

Findings

This economic evaluation of price transparency tools found issues of usability, availability, and large interhospital variability for price estimates for Current Procedural Terminology codes 66984 and 66821. These issues were not explained by geographic variability in costs.

Meaning

Despite recent federal legislature that codified price transparency requirements, some current standard charges remain ambiguous, which may disproportionately burden vulnerable and uninsured patients.

Abstract

Importance

Health care price transparency legislation is intended to reduce the ambiguity of hospital charges and the resultant financial stress faced by patients.

Objective

To evaluate the availability, usability, and variability of standard reported prices for ophthalmologic procedures at academic hospitals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this multicenter economic evaluation study, publicly available price transparency web pages from Association of American Medical Colleges affiliate hospitals were parsed for standard charges and usability metrics. Price transparency data were collected from hospital web pages that met the inclusion criteria. Geographic practice cost indices for work, practice expense, and malpractice were sourced from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data were sourced from February 1 to April 30, 2021. Multiple regression was used to study the geographic influence on standard charges and assess the correlation between standard charges.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Availability and variability of standard prices for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 66984 (removal of cataract with insertion of lens) and 66821 (removal of recurring cataract in lens capsule using laser).

Results

Of 247 hospitals included, 191 (77.3%) provided consumer-friendly shoppable services, most commonly in the form of a price estimator or online tool. For CPT code 66984, 102 hospital (53.4%) provided discount cash pay estimates with a mean (SD) price of $7818.86 ($5407.91). For CPT code 66821, 71 hospital (37.2%) provided discount cash pay estimates with a mean (SD) price of $2041.72 ($2106.44). The top quartile of hospitals, prices wise, listed included prices higher than $10 400 for CPT code 66984 and $2324 for CPT code 66821. Usability issues were noted for 36 hospitals (18.8%), including requirements for personal information or web page navigability barriers. Multiple regression analysis found minimal explanatory value for geographic practice cost indices for cash discount prices for CPT codes 66984 (adjusted R2 = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.41-0.67; P < .001) and 66821 (adjusted R2 = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51-0.77; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Despite recent legislature that codified price transparency requirements, some current standard charges remain ambiguous, with substantial interhospital variability not explained by geographic variability in costs. Given the potential for ambiguous pricing to burden vulnerable, uninsured patients, additional legislation might consider allowing hospitals to defer price estimates or rigorously define standards for actionable cash discount percentages with provisions for displaying relevant benchmark prices.

This economic evaluation assesses the degree to which hospitals provide standard charges for the required ophthalmologic shoppable services and characterizes the variability in these standard charges.

Introduction

The increasing financial burden of health care in the US is responsible for economic stress on the national, state, and individual levels.1 Medical bankruptcy remains commonplace even after legislation such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was designed to increase access and ameliorate the financial risk for patients.2 Congressional research suggests that greater price transparency can lead to more efficient outcomes and lower prices for health care.3 Although the ACA included a provision for hospitals to publish chargemasters (machine-readable files of standard charges), guidance for cost-reporting requirements was not well established until the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) provided specific guidelines for hospitals in January 2019.4 These guidelines tasked hospitals with creating publicly available chargemasters that delineate costs for certain medical services. However, the machine-readable chargemasters are often composed of inflated charges used for negotiation with insurers,5 with myriad line items from individual services and supplies. Various lines of evidence suggest these chargemasters have marked variability in prices and provide minimal useful information to patients seeking price estimates for their out-of-pocket financial responsibilty.6,7,8 Although some states have made efforts to encourage price transparency, such as requiring a statewide web page with each hospital’s chargemaster data, 43 states received a failing score for transparency in a previous analysis.9 As a result, legislation was modified for increased price transparency, which, effective January 1, 2021, established codified policies that require hospitals to publish standard charges.10

The Code of Federal Regulations requires that hospitals publish 5 types of standard charges in 2 formats, including all items and services provided by the hospital to a patient in a machine-readable file.11 In addition, hospitals must publish 300 shoppable services to be prominently displayed on a publicly available website. The 5 standard charges required for inclusion are the gross charge, discounted cash price, payer-specific negotiated charges, deidentified minimum negotiated charge, and deidentified maximum negotiated charge.12 Both versions of the public price list must include 70 CMS-specified shoppable services, including 2 ophthalmologic procedures: Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 66821 (removal of recurring cataract in lens capsule using laser) and CPT code 66984 (removal of cataract with insertion of lens).13

Ophthalmologic service prices are a convenient reference for study because of the significant cost pressure on routine procedures. Specifically, cataract surgery is cost-effective,14 and reimbursement has decreased by 16.6% for CPT code 66821 and 41.9% for CPT code 66984 in the past decade.15 Given this substantial reimbursement pressure, if price transparency policies encouraged efficient and free-market dynamics, we would expect standard charges and discount cash prices commensurate with Medicare reimbursement. Furthermore, the variability in pricing should be explained to some degree by geographic cost variability. Therefore, we explored the degree to which hospitals provide standard charges for the required ophthalmologic shoppable services and sought to characterize the variability in these standard charges.

Methods

In this economic evaluation, academic hospitals were identified as Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) hospital or health systems members and sourced from the AAMC website.16 Exclusion criteria included the following: Veteran Affairs hospitals (not required to disclose prices), duplicate health care systems (health care systems with the same address and/or the same price transparency web page), large multihospital health networks (which would have multiple locations and prices), nonophthalmologic single-specialty hospitals, and children’s hospitals. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review because the study did not meet the criteria for human research; therefore, informed consent was not required. No identifiable data were used in the study. This study followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) reporting guideline.

Pricing Disclosure Data

A routine search engine query was used to emulate an average consumer’s approach to finding shoppable service prices by graders (J.S., S.H., A.T., and S.B.). Each query consisted of the hospital name followed by “AND price transparency OR price estimate OR standard charges OR chargemaster OR price check OR discount cash price OR gross charge” and was limited to the first page of results.17,18 The presence of a machine-readable file (or chargemaster) and consumer-friendly shoppable services (or price estimator) were recorded. For those with shoppable services or a price estimator tool, the gross charge, discounted cash price, deidentified minimum and deidentified maximum prices for CPT codes 66821 and 66984 were recorded if available. For each price, graders recorded the specific components of each price (hospital, physician, anesthesia, pharmaceuticals, or supplies) if available. Given that not all cash prices are in fact discounted, for consistency, the discounted cash price will be referred to here as the cash price.

If insurance status was a required question, graders selected “uninsured.” If personal information limited to name and birthday was required, “John Doe” and “01/01/1960” were used. Additional username or password requirements are not aligned with the shoppable services mandate; therefore, the standard charges for these hospitals were considered unavailable. Graders documented whether the price was clearly identified as a cash price or gross charge. Hospitals are allowed to provide a gross charge instead of the cash price if they have not calculated the latter. Therefore, ambiguously labeled prices were considered to be gross charges. The presence of payer-specific prices, requirements for personal information to access prices, and the required service availability indication (whether or not the specific service is offered at the hospital) were documented.

User Friendliness

Consumer-friendliness metrics were defined based on internet search literature. Specifically, graders recorded time from initial query required to ascertain a single price (>5 or >15 minutes) as well as whether more than 3 clicks were required to reach a relevant page.17,18,19,20

Data Sourcing

Data were initially sourced from February 1 to March 31, 2021. However, in March 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that 307 hospitals contained syntax on their price-transparency web pages designed to hide web pages from search engines.21 As a result, hospitals without price disclosures in the initial data pull were researched from March 31 to April 30, 2021.

Geographic Practice Cost Indices

To better understand the variability in pricing among hospitals, geographic practice cost indices (GPCIs) were sourced from the CMS22 and assigned to each hospital based on the listed address from the AAMC. The GPCIs are specified by the CMS for work (related to the time and intensity of labor), practice expense (related to overhead, supplies, equipment, and staff costs), and malpractice expense (related to the costs of malpractice insurance). The GPCIs are weightings used to adjust for geographic differences for each cost relative to the national mean of each component.23 The GPCIs were assigned to each hospital based on the Medicare administrative contractor locality of the GPCI and the hospital’s primary address.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable regression analysis was used to determine the explanatory value of GPCIs for cash prices. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the correlation between cash prices for hospitals with all available data. Planned analyses for specific price components could not be conducted because of the small sample size of hospitals that report components in their price disclosures. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data collection and statistical analysis were conducted with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp), and StatTools, version 8.1 (Palisade Company LLC).

Results

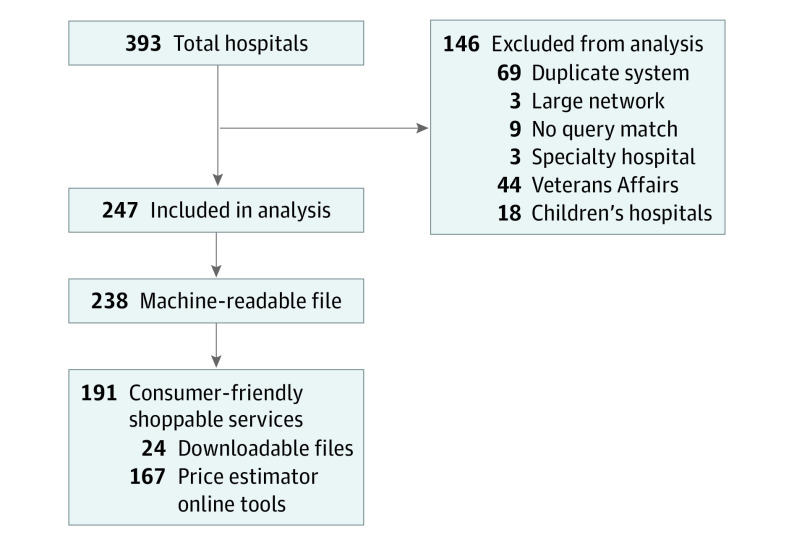

Of 393 total affiliate hospitals, 247 met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis (Figure). Of these 247 included hospitals, 238 (96.4%) provided a machine-readable chargemaster file, whereas 191 (77.3%) provided consumer-friendly shoppable services, most commonly in the form of a price estimator or online tool (Figure). Although legislation allows for hospitals to provide a gross price in cases where a cash price is unavailable, 58 prices (30.4%) did not clearly identify whether the presented estimate was a gross or cash price. Usability issues were noted for 36 hospitals (18.8%). These issues included requirements for personal information (23 [12.0%]), lengthy searching (16 [8.4%]), and more than 3 clicks to a relevant web page (11 [5.8%]) (Table 1).

Figure. Flow Diagram of Hospital Inclusion and Price Estimator Format.

Table 1. Usability Statistics for the 191 Hospitals With Shoppable Services.

| Statistic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Unclear gross or discount cash price | 58 (30.4) |

| Any usability issue | 36 (18.8) |

| Personal information required | 23 (12.0) |

| Time to price, min | |

| >5 | 16 (8.4) |

| >15 | 3 (1.6) |

| Clicks to a relevant page >3 | 11 (5.8) |

Most hospitals provided a gross charge (155 [81.2%]) and cash price (102 [53.4%]) for CPT code 66984. The CPT code 66821 prices were less frequently available, with smaller numbers presenting gross charge (101 [52.9%]) and cash price (71 [37.2%]). Only 29 hospitals (15.2%) provided full pricing data, including either all 5 components of the standard charges for each CPT code or an indicator that signified that the service was not offered at that location (Table 2).

Table 2. Shoppable Service Summary Statistics for CPT Codes 66984 and 66821.

| Charge type | Hospitals with data, No. (%) | Price listed mean (SD), $ |

|---|---|---|

| CPT code 66984a | ||

| Gross charge | 155 (81.2) | 13 144.59 (7939.68) |

| Discount cash price | 102 (53.4) | 7818.86 (5407.91) |

| Deidentified negotiated rate | ||

| Minimum | 21 (11.0) | 4606.72 (5236.19) |

| Maximum | 21 (11.0) | 13 228.65 (12 391.42) |

| Payer option present | 156 (81.7) | NA |

| CPT code 66821b | ||

| Gross charge | 101 (52.9) | 3300.26 (3961.37) |

| Discount cash price | 71 (37.2) | 2041.72 (2106.44) |

| Deidentified negotiated rate | ||

| Minimum | 15 (7.8) | 786.02 (754.11) |

| Maximum | 15 (7.8) | 2691.31 (1185.05) |

| Payer option present | 96 (50.3) | NA |

| Full pricing data | 29 (15.2) | NA |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; NA, not applicable.

Removal of cataract with insertion of lens.

Removal of recurring cataract in lens capsule using laser.

For CPT code 66984, the mean (SD) cash price was $7818.86 ($5407.91), with a range of $1120.50 to $29 729. For CPT code 66821, the mean (SD) cash price was $2041.72 ($2106.44), with a range of $251 to $12 987. The top quartile of hospitals, pricewise, listed cash prices higher than $10 400 for CPT code 66984 and $2324 for CPT code 66821. For each charge, hospital, physician, anesthesia, and materials were infrequently presented, with 94 (49.2%) presenting subcomponent pricing for CPT code 66984 and 70 (36.7%) for CPT code 66821 (Table 3).

Table 3. Subcomponents of Gross Price for Shoppable Services at 191 Hospitals.

| Subcomponent | Hospitals, No. (%) | Component price, mean (SD), $ |

|---|---|---|

| CPT code 66984a | ||

| Clear components of gross price | 94 (49.2) | NA |

| Hospital | 91 (47.6) | 13 558.99 (7664.72) |

| Physician | 51 (26.7) | 3185.35 (1600.28) |

| Anesthesia | 2 (1.0) | 407.00 (318.20) |

| Materials | 3 (1.6) | 1763.00 (652.65) |

| CPT code 66821b | ||

| Clear components of gross price | 70 (36.6) | NA |

| Hospital | 64 (33.5) | 3066.72 (4799.73) |

| Physician | 51 (26.7) | 1286.33 (777.52) |

| Anesthesia | 2 (1.0) | 91.00 (128.69) |

| Materials | 4 (2.1) | 702.38 (1161.76) |

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; NA, not applicable.

Removal of cataract with insertion of lens.

Removal of recurring cataract in lens capsule using laser.

Multiple regression analysis was performed using each standard charge as a dependent variable and all 3 GPCI adjustment measures (work GPCI, practice expense GPCI, and malpractice GPCI) as independent variables. The GPCIs were poor explanatory variables for the interhospital variation in each price. Multiple regression to determine cash prices using gross charge and all 3 GPCIs as independent variables yielded an adjusted R2 = 0.54 (95% CI, 0.41-0.67; P < .001) for CPT code 66984 and adjusted R2 = 0.64 (95% CI, 0.51-0.77; P < .001) for CPT code 66821 (Table 4). In addition, for hospitals with cash prices for both CPT codes (n = 65), the mean (SD) discount percentages for cash prices relative to gross charges were 41.2% (21.9%) for CPT code 66984 and 39.2% (21.6%) for CPT code 66821. The discount percentage for CPT code 66984 was significantly correlated with the discount percentage for CPT code 66821 (adjusted R2 = 0.92; 95% CI, 0.89-0.95; P < .001).

Table 4. Regression Analysis for the Explanatory Value of GPCIs for Variability in Standard Charges for CPT Codes 66984 and 66821.

| Standard charge | Hospital No. | Multiple regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPCIa | GPCI and grossb | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | P value | Adjusted R2 | P value | ||

| CPT code 66984c | |||||

| Gross charge | 155 | 0.00 | .39 | NA | NA |

| Discount cash price | 102 | 0.00 | .71 | 0.54 | <.01 |

| Negotiated rate | |||||

| Minimum | 21 | 0.23 | .06 | NA | NA |

| Maximum | 21 | 0.18 | .10 | ||

| CPT code 66821d | |||||

| Gross charge | 101 | 0.00 | .60 | ||

| Discount cash price | 71 | 0.00 | .43 | 0.64 | <.01 |

| Negotiated rate | |||||

| Minimum | 15 | 0.03 | .37 | NA | NA |

| Maximum | 15 | 0.00 | .95 | ||

Abbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; GPCI, geographic practice cost index; NA, not applicable.

Multiple regression using standard charge as dependent variables and work GPCI, practice expense GPCI, and malpractice expense GPCI as independent variables.

Multiple regression using discount cash price charge as dependent variables and gross charge, work GPCI, practice expense GPCI, and malpractice expense GPCI as independent variables.

Removal of cataract with insertion of lens.

Removal of recurring cataract in lens capsule using laser.

Discussion

The findings of this economic evaluation corroborate known variability in hospital pricing as well as the difficulty with CMS price transparency adherence. Given that the current requirements are intended to help vulnerable, uninsured patient populations find price estimates, it is concerning that cash price estimates varied 27-fold among hospitals for CPT code 66821 and 51-fold among hospitals for CPT code 66984. An uninsured patient with visually significant cataracts may find a price estimate of more than $10 000 in one-quarter of hospitals (and as high as roughly $30 000). In contrast, the CMS facility-limiting charge for CPT code 66984 is $598.88.22

The markup ratio or ratio of total charges to Medicare allowable costs for surgery varies by procedure as well as within and between geographic regions.24,25 Hospitals may use these markups in negotiation with insurers; therefore, higher markups can contribute to higher premiums, and uninsured patients without bargaining power are asked to pay the full charge.26 Although out-of-pocket responsibility is exceedingly difficult to calculate, self-pay patients often pay more than privately insured or Medicare patients.27 As a result, patients may elect to defer cataract surgery until they reach Medicare eligibility, travel to a distant hospital for a more affordable procedure, or, most concerningly, not pursue vision-restoring surgery.

Prior work28 in Tennessee found that 16% of hospitals fully adhered to all price transparency criteria, with 49% displaying cash prices, whereas negotiated rates and cash prices varied up to 10-fold among hospitals. Although only 31 hospitals had sufficient data for analysis, cash prices appeared unrelated to negotiated rates. These results align with the current analysis in which only 15.2% of hospitals displayed full pricing data and could be considered objectively adherent. According to the CMS, the estimated burden for reporting these estimates is $11 898.60 per hospital (approximately 150 hours of labor), with an annual maintenance cost of $3610.88 (approximately 46 hours) per hospital, whereas the penalty for nonadherence is limited at $300 per day.11 This penalty would equate to approximately 6% of the SD in cash price estimates for CPT code 66984 and 14% for CPT code 66821. Despite the minor penalty, most hospitals in the current study provided shoppable service estimates for at least 1 ophthalmologic procedure.

Although the present study is not intended to audit hospitals to report adherence issues, even if they were technically adherent, hospitals’ price transparency information had significant ambiguities that will likely limit the practical utility of these estimates. Approximately 30% of hospitals did not clearly distinguish whether the presented price was a gross or cash price, and most hospitals that provided shoppable services did not clearly distinguish the specific components of their price estimate. Although legislation requires all items and services furnished by the hospital to be included in the estimate, our results suggest that the prices provided may account for only the hospital component of a procedure, meaning that the estimates likely reflect a fraction of the true cost, with other expenses also varying widely. The total out-of-pocket responsibility for patients therefore is difficult to ascertain.

The GPCIs were poorly correlated with standard charges, and the use of gross charge and all 3 GPCIs could modestly explain 54% of the cash charge variance for CPT code 66984 and 64% for CPT code 66821. However, the percentage discounts for both procedures were strongly correlated. These findings suggest that although cash prices are at least in part unrelated to geographic cost variation and gross charges, the cash prices may simply represent a fixed percentage discount from the gross charge, which varies among hospitals. Therefore, the discounted cash prices required by the new legislation appear to represent new information for consumers. Although the magnitude of interhospital variance should incentivize consumers to use price transparency tools to shop among facilities, the ambiguity of price components and poor usability may significantly limit the practical utility.

The variability in charges for shoppable services corroborates prior findings on hospital chargemasters.6,7,8,24 Chargemasters demonstrate barriers to access, use inconsistent naming of items, and 53% to 243% interhospital price variation.6 For oncologic indications, analysis of chargemaster data found considerable variation in disclosure of charges, and significant markup of prices relative to Medicare reimbursement.24 Although the top 20 ranked hospitals in US News and World Report were found to have publicly available chargemasters, the information was rarely sufficient to allow patients to estimate out-of-pocket costs for diagnostic imaging services.7 Given these limitations, chargemasters appear to be of limited use to patients who seek an accurate estimate for their care,8 and gross charges may be not only irrelevant but also misleading for consumer-friendly public display. The findings of this economic evaluation extend these concerns to cash prices. Only 53.4% of hospitals provided cash prices for CPT code 66984 and 37.2% for CPT code 66821. Without cash prices, uninsured patients cannot compare out-of-pocket costs.

Other causes of the charge variability may include hospital characteristics, negotiation leverage, state laws, and the hospital’s payer mix. For example, for-profit, system affiliated, and urban hospitals are associated with the highest charge-to-cost ratios, and the markup may vary among states with specific legal requirements to offer discounts for eligible uninsured patients.26 A legitimate reason for price variability would be differences in quality and outcomes, although it is unlikely that variability in routine cataract surgery outcomes would explain the price ranges found here. In either case, the gap in charge variability may disproportionately affect the most vulnerable, self-pay patient populations. In theory, the high variability in pricing represents actionable information for consumers who can choose to travel for lower-cost alternatives. In turn, demand for lower-cost alternatives can exert price pressure, lowering the prices hospitals are able to charge for routine procedures. The small proportion of uninsured or self-pay consumers may limit this price pressure, and uninsured patients may instead face artificially inflated prices with limited ability to shop around because of socioeconomic or health care system literacy constraints. Inaccurate or ambiguous price estimates, insulation from true out-of-pocket responsibility, and poorly reported quality metrics are fundamental barriers to consumerism. In addition, despite proximate lower-priced health care professionals, insured individuals tend to receive care in higher-priced locations, which is influenced by referring practitioners and vertically integrated systems.29 As a result, practitioners too should be empowered with accurate price transparency tools, which may enable patients and physicians to make better health care decisions.

To best protect patients, a centralized database may be needed to allow patients to shop prices across hospitals. Companies are trying to centralize price disclosures to allow consumers to search across hospitals; however, early efforts suggested that 45% of 2267 acute care children’s and rural hospitals had poor adherence ratings.21 Nearly all hospital web pages included in the current study contained programming intended to distinguish human from machine input, which creates a large barrier to centralization of pricing information. Additional legislation as well as auditing of ambiguous pricing information may be needed. Such a policy can focus more on clear component pricing, technical requirements that allow data parsing for external tools, as well as a refined estimate of the total out-of-pocket responsibility for patients.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Hospital networks and private hospitals were excluded from the analysis. Academic medical centers may have a high cost burden for ophthalmologic procedures that exceeds Medicare reimbursement.30 Moreover, the graders are knowledgeable about the nuances of the legislation and performed repeated price estimate searches for numerous hospitals. This approach may have biased our ability to find cash prices, and our results may underestimate the extent of usability issues present for more novice health care consumers similar to prior chargemaster studies.31 Similarly, price estimator tools may have been under construction, and the specific prices collected here may represent estimates that hospitals may plan to modify with more accurate figures. Finally, this study investigated data that were readily observable, and less measurable factors may be associated with adherence and variation in standard charges.

Despite these limitations, our findings indicate considerable variability and ambiguity in estimates that are currently publicly available to patients. To our knowledge, there has been minimal literature on pricing in ophthalmology, and few studies have focused on the most recent policy updates. The current study sheds light on the current state of price transparency, or lack thereof, and identifies areas for improvement for hospital price tools. Given the potential for price estimates to influence vulnerable patients’ health-seeking behaviors, further attention as well as ongoing legislation seem warranted.

Conclusions

Although most hospitals displayed shoppable services web pages, these findings suggest policy adherence issues, usability issues, and considerable ambiguity in the prices presented. Moreover, standard prices had substantial interhospital variability not explained by geographic variability in costs. The effects of ambiguous and potentially inflated pricing information on patients’ health-seeking behavior would seem to warrant further attention. Additional legislation may be necessary to protect uninsured patients who seek shoppable cash prices.

References

- 1.Cunningham PJ. The growing financial burden of health care: national and state trends, 2001-2006. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):1037-1044. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Himmelstein DU, Lawless RM, Thorne D, Foohey P, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy: still common despite the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):431-433. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Congressional Research Service. Does price transparency improve market efficiency? implications of empirical evidence in other markets for the health sector. Updated April 29, 2008. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL34101

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare program; hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and policy changes and fiscal year 2019 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; Medicare and Medicaid electronic health record (EHR) incentive programs (promoting interoperability programs) requirements for eligible hospitals, critical access hospitals, and eligible professionals; medicare cost reporting requirements; and physician certification and recertification of claims. Fed Regist. 2018;83(160):41144-41784. 42 CFR § Parts 412, 413, 424, 495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai G, Anderson GF. US Hospitals are still using chargemaster markups to maximize revenues. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1658-1664. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu AJ, Chen EM, Vutam E, Brandt J, Sadda P. Price transparency implementation: accessibility of hospital chargemasters and variation in hospital pricing after CMS mandate. Healthc (Amst). 2020;8(3):100443. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2020.100443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glover M, Whorms D, Singh R, et al. A radiology-focused analysis of transparency and usability of top U.S. Hospitals’ Chargemasters. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(11):1603-1607. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anzai Y, Delis K, Pendleton RC. Price transparency in radiology-a model for the future. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(1 pt B):194-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Brantes F, Delbanco S, Butto E, Patino-Mazmanian K, Tessitore L. Price Transparency & Physician Quality Report Card. 2017. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.catalyze.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Price-Transparency-and-Physician-Quality-Report-Card-2017_0-1.pdf

- 10.Department of Health and Human Services; Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. Fed Regist. 2019;84(229):65524-65606. 45 CFR Subchapter E. § RIN 0938-AU22.

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates: price transparency requirements for hospitals to make standard charges public. Fed Regist. 2019. 45 CFR §180, CMS-1717-F2. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cms-1717-f2.pdf

- 12.Hospital Price Transparency Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) . 2021. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/hospital-price-transparency-frequently-asked-questions.pdf

- 13.US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 10 Steps to making public standard charges for shoppable services. 2021. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/steps-making-public-standard-charges-shoppable-services.pdf

- 14.Lansingh VC, Carter MJ, Martens M. Global cost-effectiveness of cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(9):1670-1678. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel S, Glasser D, Repka MX, Berkowitz S, Sternberg P Jr. Changes in Medicare reimbursement for commonly performed ophthalmic procedures. Ophthalmology. 2021;(Mar):S0161-6420(21)00194-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). AAMC Hospital/Health System Members. Accessed February 20, 2021. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/DynamicPage.aspx?webcode=AAMCOrgSearchResult&orgtype=Hospital%2FHealth%20System

- 17.Jansen BJ, Spink A, Saracevic T. Real life, real users, and real needs: a study and analysis of user queries on the web. Inf Process Manag. 2000;36(2):207-227. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00056-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen BJ, Spink A. An Analysis of Web Documents Retrieved and Viewed. Citeseer; 2003:65-69. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter T, Miller R. Investigating the three-click rule: a pilot study. MWAIS 2016 Proceedings. 2016. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://aisel.aisnet.org/mwais2016/2

- 20.Parr O, Dunmall K. An evaluation of online information available for women with breast implants aged 47-73 who have been invited to attend the NHS Breast Screening Programme. Radiography (Lond). 2018;24(4):315-327. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGinty T, Mathews AW, Evans M. Hospitals hide pricing data from search results. The Wall Street Journal. Accessed April 23, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hospitals-hide-pricing-data-from-search-results-11616405402

- 22.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician Fee Schedule. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-physician-fee-schedule-guide.pdf

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. How to Use the Searchable Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) MLN Booklet. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-physician-fee-schedule-guide.pdf

- 24.Xiao R, Miller LE, Workman AD, Bartholomew RA, Xu LJ, Rathi VK. Analysis of price transparency for oncologic surgery among National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers in 2020. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):582-585. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gani F, Makary MA, Pawlik TM. The price of surgery: markup of operative procedures in the United States. J Surg Res. 2017;208:192-197. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai G, Anderson GF. Extreme markup: the fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):922-928. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson GF. From ‘soak the rich’ to ‘soak the poor’: recent trends in hospital pricing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):780-789. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Triana A, Van Horn L.. Most Tennessee hospitals struggle to comply with CMS price transparency rule, Vanderbilt study finds. Modern Healthcare. February 26, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2021. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/hospitals/most-tennessee-hospitals-struggle-comply-cms-price-transparency-rule-vanderbilt-study

- 29.Chernew M, Cooper Z, Larsen-Hallock E, Scott Morton F. Are health care services shoppable? evidence from the consumption of lower-limb MRI scans. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 24869. Updated January 2019. Accessed June 2, 2021. NBER working paper series. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w24869/w24869.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkowitz ST, Sternberg P Jr, Patel S. Cost analysis of routine vitrectomy surgery. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(6):496-502. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haque W, Ahmadzada M, Allahrakha H, Haque E, Hsiehchen D. Transparency, accessibility, and variability of US hospital price data. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110109. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]