Abstract

Background: Cancer poses a serious threat to one’s health, which caused significant economic burden on the family and society. Poor availability and affordability resulted in some essential medicines failing to meet the basic health needs of this group of patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate the availability, prices and affordability of 32 anticancer essential medicines in Hubei Province, China.

Methods: Data on the availability and price related information of 32 essential anticancer medicines in the capital and five other cities of Hubei Province were collected. A total of 28 hospitals were sampled, which included 13 tertiary hospitals and 15 secondary hospitals. We used the standard methods developed by the World Health Organization and Health Action International to compare the differences in drug price, availability and affordability between secondary hospitals and tertiary hospitals.

Results: Overall, the availability of medicine was higher in tertiary hospitals. The average availability of originator brand (OBs) was 13.70% (tertiary hospitals) VS 6.67% (secondary hospitals), and lowest-priced generic (LPGs) was 62.83% (tertiary hospitals) VS 42.92% (secondary hospitals). The MPR value of most sampled medicines in secondary hospitals were less than 1. In contrast, the MPR of Cytarabine (17.15), Oxaliplatin (12.73) were significantly higher than the international reference price. The top three OBs’ total expenses for 30-days treatment were Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin, Bicalutamide. Further, their affordability was relative low, as the costs for one course using these medicines were much higher than 20% of the minimum family monthly income.

Conclusion: Though the “Zero Mark-Up” and “Centralized procurement policy of anti-tumor drugs” policies have been implemented in China, the availability issue yet to be addressed. High price and low affordability were the major barriers to the access of essential anticancer medicines. Measures should be taken to provide sufficient, available and affordable medicines to patients in need.

Keywords: essential anti-cancer medicine, availability, affordability, price, cancer

Introduction

Cancer has become a serious health problem, which contributed to severe burden of disease and even death (Zhu et al., 2019). A total of 9.6 million deaths due to cancer diseases were reported worldwide in 2018 (Erratum, 2020). China accounts for 21.0% of the worldwide new cancer cases, and total of 22.96 million Chinese residents died of cancer (Shaoqing, 2019). At present, anticancer medicine is a core component of treatment, but barriers to receiving cancer therapy such as high price of anticancer medicines and poor availability were yet to be solved (Smith et al., 2014). These problems may be related to medical information asymmetry and the distribution of responsibilities between the drug purchasing sector and the patients who bear the cost restrict competition in the market (Hasan et al., 2019).

Essential medicines are the indispensable drugs that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population. Meanwhile, they are selected with due regard to rational use and equitable access on their efficacy, safety and comparative cost-effectiveness (Beran et al., 2018). To better meet the necessary treatment needs, the Chinese government attaches great importance to the development and implementation of the Essential Medicine List (EML) (Khanal et al., 2019). In 2018, China re-adjusted the national EML, and increased the growth rate of oncology drugs by 35%. In terms of cancer treatment, the 2018 edition of the “National Essential Medicine List” added five kinds of non-targeted drugs, including Ifosfamide, Gemcitabine, Pingyangmycin, Capecitabine, and Letrozole (Dong et al., 2020). The supplementary medicines can greatly alleviate the burden of cancer treatment.

In addition, the price of 14 anticancer drugs fell by an average of 14.95% in China, as the National Medical Security Bureau issued centralized drug purchase measures and accelerated the pace of medical insurance drug-price negotiation (Chinese, Government, 2018; Kaiyue et al., 2021). Despite medical insurance policy system was improved, dozens of targeted anticancer drugs have been included in category B (local medical expense settlement institutions could bear approximate 55–70% of the patients’ cost of anticancer drug) (Kunhe et al., 2017), due to the unbalanced distribution of medical resources and the per capita financing guarantee level of China’s medical insurance is still relatively weak, the total amount of medical insurance controlled by provinces and hospitals has limited funds allocated for health care, as a result, many cancer drugs still have high treatment costs even after medical insurance promotion policies are implemented (Yf).

Recently, most of domestic studies on essential medicines focused on antibacterial drugs and medications for chronic diseases (Wu et al., 2018; Dong et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). Their study can reflect the common problems in the availability and affordability of essential drugs in China, however, the question regarding whether it is the same case for anticancer still awaits further investigation. Therefore, we investigated the price, availability and affordability of anticancer drugs in 28 public hospitals in Hubei Province, in order to explore the factors influencing the shortage of medicines and rapidly increasing health expenditure, and accordingly, propose corresponding strategies to the government and pharmaceutical management institutes.

Methods

A cross sectional survey was conducted from November 2018 to January 2019. Data were collected on medicine price, availability and affordability information from tertiary hospitals and secondary hospitals in six cities of Hubei Province following WHO/HAI standardized approach and Health Action International (HAI) (Khuluza and Heide, 2017).

Study Design/Sampling

Area Selection

We selected six cities as survey regions in Hubei Province by referring to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2018, according to which, we selected three cities in high-income (Wuhan, Yichang, Xiangyang) and low-income (Huanggang, Xianning, Suizhou) areas, respectively (China YearBooks, 2019). Hospitals were selected using a multistage clustered approach. Firstly, we chose the best tertiary hospital as the survey anchor (it ranked the first in this area) in each city (for instance, Tongji affiliated hospital of Tongji medical college was selected in Wuhan city). After identifying the survey anchor, we selected at least one secondary hospital pharmacy, which was closest to the anchor hospital. Since Baidu maps was used to select secondary hospital pharmacies from a list of all facilities within a 3-h drive from each survey anchor hospital. But if back-up outlet was less than 50% of the medicines on the Medicine Price Data Collection form, then we would select another secondary hospital pharmacy in the sample list. Last, a total of 13 tertiary hospitals and 15 secondary hospitals in the public sector were selected from six cities in Hubei Province. As anticancer drugs belong to the category of key controlled drugs in China, hence, they are mainly available in secondary and tertiary hospitals of China. So we don’t include retail pharmacies in our investigation.

Medicine Selection

A total of 32 medicines were included in this survey, referring to 2017 WHO Essential Medicine List (WEML) and 2018 National Essential Medicine List (NEML). Considering the common acute and medication conditions in tertiary and secondary hospitals of Hubei Province, we divided the selected medicines into two parts according to the available data collected from the sample hospitals. Firstly, the intersection area of anticancer drugs were from the WHO Essential Medicine List and National Essential Medicine List, which included 20 core essential medicines. Then, additional 12 sample drugs were also included in this survey list as supplementary according to oncologist’s recommendation and the actual needs of local hospitals. For each medicine in the survey, data were collected for two medicine types: the originator brand (OBs), and the lowest-priced generic (LPGs) equivalent found at each hospital.

Data Collection

With the aid of skilled pharmacy present, trained investigators visited the pharmacy department of the sampled tertiary and secondary hospitals. They collected information regarding the cost and availability using a standardized data collection form. At the end of each day, two students would enter the data into a designed MS Excel Workbook provided as a part of the WHO/HAI methodology (Eden et al., 2019; Saeed et al., 2019). The items included in the standardized form were as follows: basic information of the facility (hospital name, hospital level, survey date), information of the medicine (medicine in stock in the hospital on the day of data collection, yes or no), dosage, strength, medicine type (OB/LPG), and the retail price at the time of survey (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

List of 32 anticancer medicines surveyed in the Hubei Province.

| Name | Strength | Dosage Form | Volume | WHO EML | NEML |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Folinate | 100 mg/10 ml | VIAL | 1 | no | yes |

| Capecitabine | 500 mg | TAB-CAP | 12 | yes | yes |

| Carboplatin | 100 mg/10 ml | VIAL | 1 | no | no |

| Ciclosporin | 25 mg | TAB-CAP | 50 | yes | yes |

| Cisplatin | 20 mg | VIAL | 1 | no | yes |

| Cyclophosphamide | 200 mg | VIAL | 1 | no | yes |

| Cytarabine | 100 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Daunorubicin | 10 mg | VIAL | 1 | no | no |

| Docetaxel Trihydrate | 20 mg/ml | VIAL | 1 | yes | no |

| Doxorubicin | 10 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Etoposide | 20 mg/ml | VIAL | 1 | yes | no |

| Fluorouracil | 0.25 g/10 ml | VIAL | 1 | no | yes |

| Gemcitabine | 200 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Ifosfamide | 500 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Imatinib | 100 mg | TAB-CAP | 60 | yes | yes |

| Irinotecan | 40 mg/2 ml | VIAL | 1 | yes | no |

| Mercaptopurine | 50 mg | TAB-CAP | 50 | yes | yes |

| Mesna | 0.4 g/4 ml | AMPOULE | 1 | yes | yes |

| Methotrexate Sodium | 100 mg/ml | VIAL | 1 | no | no |

| Methylprednisolone | 500 mg | VIAL | 1 | no | no |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil |

250 mg | TAB-CAP | 40 | no | yes |

| Oxaliplatin | 50 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Paclitaxel | 30 mg/5 ml | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Tamoxifen Citrate | 10 mg | TAB-CAP | 60 | yes | yes |

| Vincristine | 1 mg | VIAL | 1 | yes | yes |

| Letrozole | 2.5 mg | TAB-CAP | 10 | no | yes |

| Gefitinib | 250 mg | TAB-CAP | 10 | no | yes |

| Bicalutamide | 50 mg | TAB-CAP | 28 | yes | no |

| Hydroxycarbamide | 500 mg | TAB-CAP | 100 | yes | yes |

| Vinorelbine | 10 mg/ml | VIAL | 1 | yes | no |

| Tacrolimus | 1 mg | TAB-CAP | 10 | no | no |

| Ondansetron | 4 mg | TAB-CAP | 10 | yes | yes |

Patient and Public Involvement

It was not possible or appropriate to involve patients or the public in the design, data collection, reporting or dissemination plans of this analysis.

Assessment of Availability

The availability of anticancer medicines was reported as the percentage (%) of medicine outlets in which the information was documented by surveyed facilities on the day of data collection. Availability was classified as 4°; Absent: 0 of facilities, suggested that we could not find these medicines in the facility; Low: < 50%, these medicines were rarely purchased; Fairly high: 50–80%, these medicines were found in several facilities; High: > 80%, most institutions sold these medicines. In addition, mean percentage availability of OBs and LPGs were calculated for the investigations (Zhu et al., 2019).

Price Assessment

In order to make standard comparisons, price was evaluated by median price ratio (MPR) according to WHO/HAI approach, which is the ratio of median price of individual medicine obtained during the survey (Dong et al., 2020). Moreover, we used Management Sciences for Health (MSH 2015) International Drug Price Indicator Guide as the source of reference prices. MPR was calculated using the formula given below: Median Price Ratio (MPR) = Median local unit price/International reference unit price. It can provide a more intuitive data presentation for drug price monitoring: when the value of MPR is less than 1, it indicates that the price of the drug under investigation is lower than the international average standard. In other words, the price control is efficient. The value of MPR between 1 and 2 indicates that the drug price is acceptable; if MPR>2, this means that the drug price level is high and needs to be contained (Guan et al., 2018).

Affordability

In general, the total cost of the unit treatment for chronic diseases with the standard dose of the drug is equivalent to 1 month’s working days (daily wages) of the lowest paid non-technical government employee that enables him/her to purchase the standard course of cancer treatment. However, the duration of anticancer therapy may be longer. Moreover, the price of many anticancer drugs is too expensive, which causes heavy economic burden for cancer patients. Thus, with the aim to precisely assess the affordability, we used the approach proposed by Khatib and Sarwar (Khatib et al., 2015; Sarwar et al., 2018): if the total expenditure of medicine in 30 days accounted for 20% or less of the minimum family monthly income, it was regarded as affordable (Eden et al., 2019). The calculation formula was:

Results

We calculated the availability of originator brands (OBs) and lowest priced generics (LPGs) across the 32 anticancer medicines. In this survey, 92.43% OB was unavailable overall, and 10 OBs of 32 medicines were not available in tertiary hospitals nor secondary hospitals. The top three percentage availability of OBs in tertiary hospitals included Bicalutamide (47.62%), Methylprednisolone (38.10%) and gefitinib (28.57%). In tertiary hospitals, the average availability of OBs was 13.70%. In contrast, the mean availability of OBs was 6.67% in secondary hospitals (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Availability of anticancer medicines in Tertiary and Secondary hospitals.

| Medicine name | OBs(%) | LPGs (%) | Total (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary hospital | Secondary hospital | Tertiary hospital | Secondary hospital | OBs | LPGs | |

| Calcium Folinate | 0.00 | 0.00 | 47.62 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 53.81 |

| Capecitabine | 23.81 | 40.00 | 52.38 | 66.67 | 31.90 | 59.52 |

| Carboplatin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 52.38 | 33.33 | 0.00 | 42.86 |

| Ciclosporin | 23.08 | 6.67 | 38.10 | 13.33 | 10.48 | 25.71 |

| Cisplatin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 42.86 | 53.33 | 0.00 | 48.10 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 15.38 | 0.00 | 52.38 | 93.33 | 4.76 | 72.86 |

| Cytarabine | 7.69 | 0.00 | 28.57 | 13.33 | 2.38 | 20.95 |

| Daunorubicin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 28.57 | 26.67 | 0.00 | 27.62 |

| Docetaxel Trihydrate | 7.69 | 0.00 | 47.62 | 73.33 | 2.38 | 60.48 |

| Doxorubicin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.81 | 33.33 | 0.00 | 28.57 |

| Etoposide | 0.00 | 0.00 | 57.14 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 68.57 |

| Fluorouracil | 7.69 | 0.00 | 33.33 | 46.67 | 2.38 | 40.00 |

| Gemcitabine | 7.69 | 0.00 | 61.90 | 73.33 | 2.38 | 67.62 |

| Ifosfamide | 23.08 | 0.00 | 33.33 | 13.33 | 7.14 | 23.33 |

| Imatinib | 7.69 | 6.67 | 38.10 | 20.00 | 5.71 | 29.05 |

| Irinotecan | 7.69 | 6.67 | 47.62 | 46.67 | 5.71 | 47.14 |

| Mercaptopurine | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.38 |

| Mesna | 7.69 | 0.00 | 38.10 | 20.00 | 2.38 | 29.05 |

| Methotrexate Sodium | 0.00 | 0.00 | 52.38 | 66.67 | 0.00 | 59.52 |

| Methylprednisolone | 38.10 | 40.00 | 9.52 | 26.67 | 39.05 | 18.10 |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 7.69 | 13.33 | 28.57 | 13.33 | 9.05 | 20.95 |

| Oxaliplatin | 15.38 | 6.67 | 61.90 | 93.33 | 8.10 | 77.62 |

| Paclitaxel | 23.08 | 0.00 | 42.86 | 40.00 | 7.14 | 41.43 |

| Tamoxifen Citrate | 0.00 | 0.00 | 52.38 | 80.00 | 0.00 | 66.19 |

| Vincristine | 0.00 | 6.67 | 28.57 | 46.67 | 3.33 | 37.62 |

| Letrozole | 23.08 | 20.00 | 52.38 | 66.67 | 17.14 | 59.52 |

| Gefitinib | 28.57 | 13.33 | 28.57 | 20.00 | 23.33 | 24.29 |

| Bicalutamide | 47.62 | 40.00 | 23.81 | 20.00 | 43.81 | 21.90 |

| Hydroxycarbamide | 0.00 | 0.00 | 38.10 | 40.00 | 0.00 | 39.05 |

| Vinorelbine | 7.69 | 0.00 | 42.86 | 53.33 | 2.38 | 48.10 |

| Tacrolimus | 15.38 | 13.33 | 28.57 | 20.00 | 11.43 | 24.29 |

| Ondansetron | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.81 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 21.90 |

| Mean Percent | 13.70 | 6.67 | 38.84 | 42.92 | 7.57 | 40.88 |

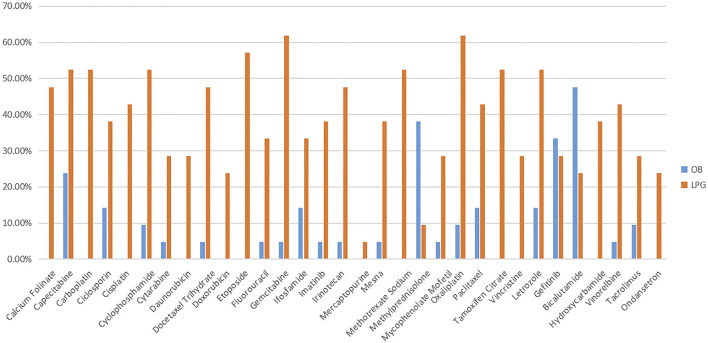

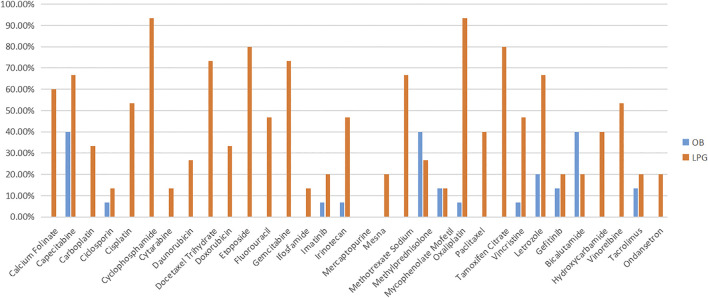

For LPGs, overall, the mean availability of surveyed medicines was 40.88%, and the mean availability of LPGs was 38.84% in tertiary hospitals, and 42.92% in secondary hospitals (Table 2). Besides, Oxaliplatin and Gemcitabine were maximal for 61.90% in tertiary hospitals (Figure 1). Two medicines with the highest availability in the secondary hospitals were Cyclophosphamide (93.33%) and Oxaliplatin (93.33%). Nevertheless, most LPGs were available in secondary hospitals (Figure 2). In general, the availability of the selected medicines in tertiary hospitals was higher than that in secondary hospitals.

FIGURE 1.

The availability of LPG and OB medicines in tertiary hospital.

FIGURE 2.

The availability of LPG and OB medicines in secondary hospital.

Table 3 illustrates the median price patients paid and MPR in tertiary and secondary hospitals for 32 anticancer medicines in Hubei Province. The results showed that the overall price of medicines varied from RMB0.49 to RMB2290.12. In total, the median patient prices of 4 OBs were over double the IRP. The median patient prices of OB for Oxaliplatin (RMB2290.12) ranked first. Especially, its MPR was 12.73 times higher than the international reference price (IRP)from MSH. Furthermore, the MPR of 3 OBs were more than double that of IRP in tertiary hospital: Cytarabine (MPR = 17.15), Ifosfamide (MPR = 2.30), Paclitaxel (MPR = 2.81), respectively. The MPR value of sample medicines in secondary hospitals were less than 2, except Letrozole (MPR = 3.26). Additionally, the median patient prices of most LPGs were in line with IRP standards.

TABLE 3.

The median patient price and MPR of anticancer medicines in tertiary and secondary hospitals in Hubei Province.

| Medicine name | Medicine type | Tertiary hospital (n = 13) | Secondary hospital (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median price | MPR | Median price | MPR | ||

| Calcium Folinate | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 16.18 | 1.00 | 16.18 | 1.00 | |

| Capecitabine | OB | 30.72 | 1.00 | 30.72 | 1.00 |

| LPG | 8.16 | 0.27 | 11.14 | 0.36 | |

| Carboplatin | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 53.90 | 1.00 | 53.90 | 1.00 | |

| Ciclosporin | OB | 9.15 | 1.00 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 5.18 | 0.57 | 5.36 | 0.59 | |

| Cisplatin | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 7.57 | 1.04 | 7.30 | 1.00 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 25.20 | 1.00 | 25.20 | 1.00 | |

| Cytarabine | OB | 140.49 | 17.15 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 8.19 | 1.00 | 8.09 | 0.99 | |

| Daunorubicin | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 27.15 | 1.00 | 27.15 | 1.00 | |

| Docetaxel | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 204.84 | 0.66 | 123.00 | 0.40 | |

| Doxorubicin | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 23.28 | 1.00 | 23.28 | 1.00 | |

| Etoposide | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 7.79 | 0.78 | 9.28 | 0.93 | |

| Fluorouracil | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 9.80 | 1.98 | 5.10 | 1.03 | |

| Gemcitabine | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 150.99 | 1.00 | 79.75 | 0.53 | |

| Ifosfamide | OB | 107.88 | 2.30 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 47.00 | 1.00 | 42.21 | 0.90 | |

| Imatinib | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 14.05 | 0.70 | 14.05 | 0.70 | |

| Irinotecan | OB | 385.87 | 1.66 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 252.44 | 1.08 | 252.44 | 1.08 | |

| Mercaptopurine | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 0.62 | 0.26 | NA | NA | |

| Mesna | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 8.80 | 1.00 | 8.80 | 1.00 | |

| Methotrexate Sodium | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 19.60 | 1.00 | 19.60 | 1.16 | |

| Methylprednisolone | OB | 123.96 | 1.00 | 125.83 | 1.02 |

| LPG | 165.72 | 1.34 | 169.10 | 1.36 | |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | OB | 14.85 | 1.85 | 14.87 | 1.85 |

| LPG | 8.04 | 1.00 | 8.31 | 1.03 | |

| Oxaliplatin | OB | 2,290.12 | 12.73 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 179.88 | 1.00 | 73.10 | 0.41 | |

| Paclitaxel | OB | 94.19 | 2.81 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 33.55 | 1.00 | 15.99 | 0.48 | |

| Tamoxifen Citrate | OB | NA | 1.09 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 0.58 | NA | 0.56 | 1.06 | |

| Vincristine | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 43.47 | 3.25 | 9.49 | 1.00 | |

| Letrozole | OB | 37.55 | 1.00 | 37.73 | 3.26 |

| LPG | 10.51 | 1.00 | 11.56 | 1.00 | |

| Gefitinib | OB | 228 | 0.69 | 231.90 | 1.02 |

| LPG | 158.4 | 1.32 | 158.50 | 0.70 | |

| Bicalutamide | OB | 40.83 | 0.90 | 40.83 | 1.32 |

| LPG | 27.88 | NA | 40.83 | 1.32 | |

| Hydroxycarbamide | OB | NA | 1.00 | NA | NA |

| LPG | 0.49 | NA | 0.49 | 1.00 | |

| Vinorelbine | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 134.82 | 1.00 | 134.82 | 1.00 | |

| Tacrolimus | OB | 23.11 | 1.98 | 23.21 | 1.99 |

| LPG | 10.51 | 0.90 | 16.32 | 1.40 | |

| Ondansetron | OB | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LPG | 13.89 | 1.16 | 22.24 | 1.86 | |

The unit of measurement of Median Price is RMB.

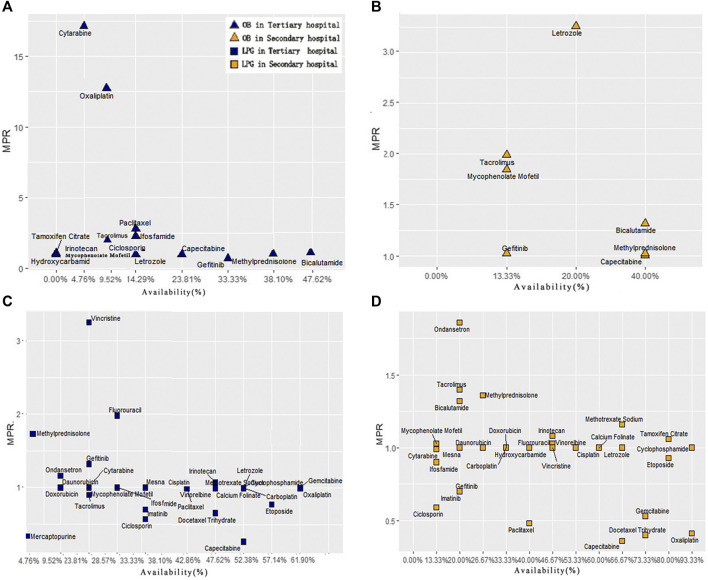

In order to compare the difference of drug availability and MPR value between secondary and tertiary hospitals, we made 4 scatter plots of the availability and MPR value of 32 anticancer drugs (Figure 3). In tertiary hospitals, for OBs, two points located in the upper left area of the graph, which were cytarabine and oxaliplatin, whose MPR was more than 10 times. However, their availability was quite low. The medicines with higher availability of OBs were gefitinib, Bicalutamide and Methylprednisolone with low MPR. For LPGs, Vincristine had the highest MPR value (3.25), and its availability was low. Eight medicines had fairly high availability with acceptable MPR value (MPR of 1 or less is interpreted as efficient procurement in the public sector) (Mendis et al., 2007; Kasonde et al., 2019).

FIGURE 3.

Comprehensive analysis of anticancer medicine availability and MPR in Hubei Province. (A) Scatter plot of OBs availability and MPR in tertiary hospitals. (B) Scatter plot of OBs availability and MPR in secondary hospitals. (C) Scatter plot of LPGs availability and MPR in tertiary hospitals. (D) Scatter plot of LPGs availability and MPR in secondary hospitals.

In secondary hospitals, for OBs, only seven drugs with MPR value could be obtained. Figure 3 indicates Letrozole with high availability and MPR. Only Capecitabine’s MPR is acceptable. For LPGs, 11 medicines were highly available. Moreover, 21 drugs with MPR value were included. The result also showed that these eight medicines: Irinotecan, Methotrexate Sodium, Methylprednisolone, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Tamoxifen Citrate, Bicalutamide, Tacrolimus, Ondansetron were out of the acceptable range (MPR of 1 or less).

Table 4 shows the affordability of the anticancer medicines based on the duration of treatment. Overall, the mean affordability of the studied medicines was 2.89. For 31 LPGs, the mean affordability value was 1.79, which was within normal range. However, for 14 OBs, the mean value of affordability was 5.29. Further, irinotecan (13.89) and oxaliplatin (11.91) induced large payment burden, as the cost of 30 days dosage was higher than 10 times of 20% household minimum monthly income. In the surveyed hospitals, the affordability of 50% (7/14) of the OBs exceeded the mean affordability value (5.29), and 22.58% (7/31) of LPGs was over the average affordability.

TABLE 4.

Affordability of anticancer medicines based on 20% of the minimum household monthly income in Hubei Province.

| Medicine name | Medicine type | Dosage | Strength | Total course of treatment | Median patient price | Affordability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Folinate | OB | VIAL | 100 mg/10 ml | NA | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 100 mg/10 ml | 10 | 16.18 | 0.32 | |

| Capecitabine | OB | TAB-CAP | 500 mg | 105 | 30.72 | 6.45 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 500 mg | 105 | 8.16 | 1.71 | |

| Carboplatin | OB | VIAL | 100 mg/10 ml | 6 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 100 mg/10 ml | 6 | 53.90 | 0.65 | |

| Ciclosporin | OB | TAB-CAP | 25 mg | 30 | 9.15 | 0.55 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 25 mg | 30 | 5.18 | 0.31 | |

| Cisplatin | OB | VIAL | 20 mg | 10 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 20 mg | 10 | 7.57 | 0.15 | |

| Cyclophosphamide | OB | VIAL | 200 mg | 20 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 200 mg | 20 | 25.20 | 1.01 | |

| Cytarabine | OB | VIAL | 100 mg | 20 | 140.49 | 5.62 |

| LPG | VIAL | 100 mg | 20 | 8.19 | 0.33 | |

| Daunorubicin | OB | VIAL | 10 mg | 6 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 10 mg | 6 | 27.15 | 0.33 | |

| Docetaxel | OB | VIAL | 20 mg/ml | 3.75 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 20 mg/ml | 3.75 | 204.84 | 1.54 | |

| Doxorubicin | OB | VIAL | 10 mg | 6 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 10 mg | 6 | 23.28 | 0.28 | |

| Etoposide | OB | VIAL | 20 mg/ml | 30 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 20 mg/ml | 30 | 7.79 | 0.47 | |

| Fluorouracil | OB | VIAL | 0.25 g/10ml | 300 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 0.25 g/10ml | 300 | 9.80 | 5.88 | |

| Gemcitabine | OB | VIAL | 200 mg | 15 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 200 mg | 15 | 150.99 | 4.53 | |

| Ifosfamide | OB | VIAL | 500 mg | 15 | 107.88 | 3.24 |

| LPG | VIAL | 500 mg | 15 | 47.00 | 1.41 | |

| Imatinib | OB | TAB-CAP | 100 mg | 112 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 100 mg | 112 | 14.05 | 3.15 | |

| Irinotecan | OB | VIAL | 40 mg/2 ml | 18 | 385.87 | 13.89 |

| LPG | VIAL | 40 mg/2 ml | 18 | 252.44 | 9.09 | |

| Mercaptopurine | OB | TAB-CAP | 50 mg | 240 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 50 mg | 240 | 0.62 | 0.30 | |

| Mesna | OB | VIAL | 0.4 g/4 ml | 10 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 0.4 g/4 ml | 10 | 8.80 | 0.18 | |

| Methotrexate Sodium | OB | VIAL | 100 mg/ml | 32 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 100 mg/ml | 32 | 9.80 | 0.63 | |

| Methylprednisolone | OB | VIAL | 500 mg | 20 | 123.96 | 4.96 |

| LPG | VIAL | 500 mg | 20 | 161.72 | 6.47 | |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | OB | TAB-CAP | 250 mg | 240 | 14.85 | 7.13 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 250 mg | 240 | 8.04 | 3.86 | |

| Oxaliplatin | OB | VIAL | 50 mg | 2.6 | 2290.12 | 11.91 |

| LPG | VIAL | 50 mg | 2.6 | 179.88 | 0.94 | |

| Paclitaxel | OB | VIAL | 30 mg/5 ml | 30 | 94.19 | 5.65 |

| LPG | VIAL | 30 mg/5 ml | 30 | 33.55 | 2.01 | |

| Tamoxifen Citrate | OB | TAB-CAP | 10 mg | 30 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 10 mg | 30 | 0.58 | 0.03 | |

| Vincristine | OB | VIAL | 1 mg | 4 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | VIAL | 1 mg | 4 | 134.82 | 1.08 | |

| Letrozole | OB | TAB-CAP | 2.5 mg | 75 | 23.11 | 3.47 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 2.5 mg | 75 | 10.51 | 1.58 | |

| Gefitinib | OB | TAB-CAP | 250 mg | 30 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 250 mg | 30 | 13.89 | 0.83 | |

| Bicalutamide | OB | TAB-CAP | 50 mg | 30 | 134.82 | 8.09 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 50 mg | 7 | 23.11 | 0.32 | |

| Hydroxycarbamide | OB | TAB-CAP | 500 mg | 7 | 10.51 | 0.15 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 500 mg | 7 | NA | 0.00 | |

| Vinorelbine | OB | VIAL | 10 mg/ml | 7 | 13.89 | 0.19 |

| LPG | VIAL | 10 mg/ml | 7 | 134.82 | 1.89 | |

| Tacrolimus | OB | TAB-CAP | 1 mg | 6 | 23.11 | 2.77 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 1 mg | 6 | 10.51 | 0.13 | |

| Ondansetron | OB | TAB-CAP | 4 mg | 80 | NA | 0.00 |

| LPG | TAB-CAP | 4 mg | 80 | 13.89 | 2.22 | |

| Mean affordability | OB | 5.29 | LPG | 1.79 | Total | 2.89 |

Total course of treatment is calculated as 30 days' dose of anticancer medicines.

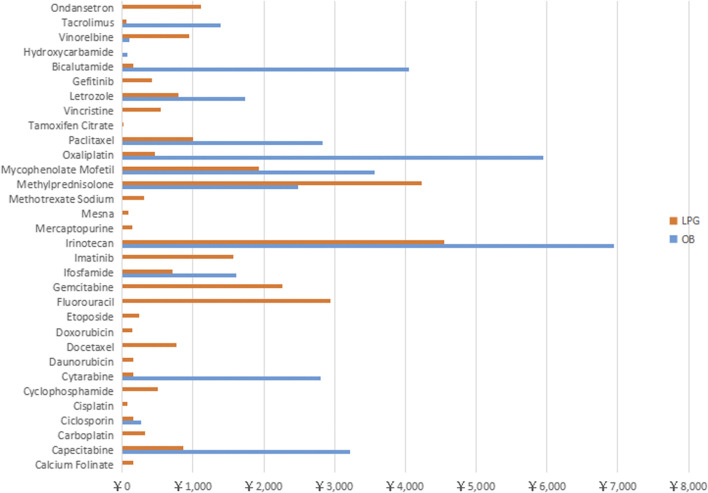

Figure 4 shows that the monthly medicine expenditure of 3 OBs (Irinotecan, Bicalutamide, Oxaliplatin) exceeded 4000 RMB, and the cost of five medicines (Paclitaxel, Methylprednisolone, Mycophenolate Mofetil, Cytarabine and Capecitabine) were within 2000–4000 RMB. For LPGs, the 30 days treatment expenditure of four medicines (Irinotecan, Methylprednisolone, Gemcitabine, Fluorouracil) were over 2000 RMB, and the cost of most of the rest medicines were around 1000 RMB.

FIGURE 4.

Total treatment cost of 32 anti-neoplastic for Originator Brand and Lowest Prices Generic expressed in RMB across Hubei Province.

Discussion

Availability of Surveyed Medicines

The study evaluated the availability, price and affordability of 32 anticancer medicines in Hubei Province by using the WHO and HAI standard methodology. After investigating 13 tertiary hospitals and 15 secondary hospitals’ essential drugs, overall, we found that 7.57% of OB and 40.88% of LPGs were available in Hubei Province, China. The findings are similar with prior surveys in developing countries (Khuluza and Haefele-Abah, 2019; Saeed et al., 2019; Lambojon et al., 2020). Amna Saeed found that the overall availability of surveyed medicines in public sector was 6.8% only for OBs and 35.3% for the LPGs in Pakistan. In Philippines, the mean availability of surveyed medicines in the public sector was 1.3% for OBs and 25.0% for LPGs (Rui et al., 2019). They also found that most of the OB medicines were produced by large international manufacturers. Due to the lack of effective external supervision and approval for the OB medicines, price leading and brand premiums led to the relatively higher price.

Compared with secondary hospitals, the availability of surveyed medicines were higher in tertiary hospitals. Since radiotherapy and chemotherapy of tumor are very professional and expensive, they are mostly concentrated in large specialized hospitals or departments of tertiary hospitals, which contributed to the higher availability (Rui et al., 2019).

In general, the price of the OBs was high because of its core patent right of drugs, which endowed the original drug enterprises with a monopoly position (Babar et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019). However, LPG can be used as a competitive product to make up for its lack of accessibility (Abdel Rida et al., 2019). Especially in low and middle-income countries, hospitals will take into account the actual purchasing power of patients, and appropriately reduce the inventory proportion of OBs in hospitals (Dorj et al., 2018; Guan et al., 2018). The findings of our study showed that the availability of some medicines was relatively high, including Gemcitabine, Etoposide, Oxaliplatin, Cyclophosphamide, Tamoxifen, the underlying reason may be that these medicines could achieve better survival time in the treatment of advanced cancer and adverse reactions can be tolerated (Juxiang et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2018). Other reasons maybe they were included early in the list of national essential medicines, and widely used in the treatment of some high incidence and mortality cancers, such as lung cancer, gastric cancer, colon cancer in China (Yahong, 2019).

Price Comparison

As presented in Figure 3, most of the LPGs for anticancer could be acquired with acceptable price. Meanwhile, for OBs, the MPR value of Cytarabine, Oxaliplatin and Paclitaxel were much higher than the international reference price from MSH. Compared with LPGs, the relatively retail prices for OBs were much higher. This may be explained by the large patient’s rigid demand for the above three categories of medicines. In addition, the particularity of pharmaceutical production technical and core-patient barriers made it difficult for many domestic generic drugs to reach the ideal level and curative effect of the originator brand drugs (Cameron et al., 2009).

The government has been very concerned about the field of medicine prices. In recent years, it has also issued relevant policies to curb the disordered competition in pharmaceutical market. Launching the new direction of “purchasing with quantity, linking quantity with price and combining bidding and purchasing” has pushed the price of national essential drugs back to a reasonable level (Mao et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2020). Especially, after the conformity evaluation, generic drugs gradually occupy the share of originator brand drugs and expand the OBs’ substitution in favour of lowering public health expenditure in hospitals (Faruqui et al., 2019). Diversified and fair competitions between OBs and LPGs may bring more preferential benefits to patients.

Affordability

For the patients from low-income families in Hubei Province, they are still unable to afford course of treatment. Economic burden of disease becomes the major barrier that affects their access to effective targeted anticancer medicines (Mengyuan et al., 2017). In this study, the measurement affordability based on the total cost of treatment and the estimation of household income. The top five medicines with poor affordability were: Irinotecan, Oxaliplatin, Bicalutamide and Mycophenolate Mofetil, Methylprednisolone, which were more than 6 times of the 20% minimal monthly household income. The heavy payment burden may be caused by different dosages of 30 days treatment course and the unit price of each medicine. Meanwhile, in Mexico, most cancer medicines are also unaffordable for patients, the median affordability of patented medicines was 30.17 days’ wages needed to buy 1 day of one medicine’s supply (Moye-Holz et al., 2020). Hence, our government should establish special funds to support low-income household, and improve the efficiency of national medical insurance (Sarwar et al., 2018). Potential strategies worth consideration include: simplifing the approval process of new drugs at home and abroad, improving their access to the market, reducing the innovation cost, and attracking more high-quality anticancer generic drugs to enter the market (Eden et al., 2019). Importantly, in terms of the bidding and procurement process, National Health-care Security Administration negotiates with pharmaceutical manufacturers for reducing the OBs price and ensuring that the patients can afford the essential anticancer medicines (Jiao et al., 2018).

Limitations

In this survey, private hospitals and pharmacies were not included in the survey because only few designated pharmacies were licensed to operate special drugs (such as anti-cancer drugs) in China. Hence, the use of target anticancer drugs in designated pharmacies is of particular concern in subsequent studies. Second, during data collection, some “out-of-stock” medicines were not included in the calculation. Thus, the findings may not be generalizable to the whole availability of anticancer medicines. Lastly, for the convenience in comparing the affordability indicators, but lack of accounting for detailed cancer treatment protocols, all medicines charges were calculated according to the course of 30 days. In fact, the patient’s cancer type and risk stratum are different, which could lead to some biases in the accuracy of affordability.

Conclusion

Compared with secondary hospitals, it is obvious that the availability of essential anticancer medicines was found to be much higher in tertiary hospitals. Overall, LPGs was prior to OBs in terms of availability. “Drug addition cost” is a policy adopted by the government to compensate hospital income in a specific period of time. However, with the implementation of the “Zero Mark-up of Drugs” policy from 2009, for getting rid of compensation effect of drug income on public hospitals, the price of anticancer medicines returned to a reasonable level (Mao et al., 2019), apart from some special Originator Brand medicines’ price were still much higher than the international reference price. This study also identified several types of drugs that patients could hardly afford during the treatment. Policymakers should pay more attention to the possibility of poverty caused by expenditure on major cancer diseases. More actions should be adopted to regulate and restrict the pharmaceutical industry, drug circulation, patients and doctors, and improve the availability of essential anticancer medicines in Hubei Province.

Acknowledgments

The authors were thankful for Professor Rui Huang and their stuff who support their available time for coordination and arrangement of investigation, in addition, we also would like to all the participants who attended in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, and the approval number is 2020(S223). The Surveyed hospitals were informed by sending research letter prior to data collection, and all hospitals agreed to participant in this survey.

Author Contributions

CC participate in study design and conception, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript drafting. We thank ZF and YD for guiding this study, and DF design the whole investigation and attend to collect data, ZY and JW help us to input and check data, RW is responsible for proposing the revising suggestions of the manuscript draft.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Youth Fund (Grant Number: 71,804,052).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

HAI, Health Action International; WHO, World Health Organization; EML, Essential Medicine List; OB, Originator Brand; LPG, Lowest Priced Generic; NEML, National Essential Medicine List.

References

- Abdel Rida N., Mohamed Ibrahim M. I., Babar Z. U. D. (2019). Relationship between Pharmaceutical Pricing Strategies with price, Availability, and Affordability of Cardiovascular Disease Medicines: Surveys in Qatar and Lebanon. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19 (1), 973. 10.1186/s12913-019-4828-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babar Z. U., Ramzan S., El-Dahiyat F., Tachmazidis I., Adebisi A., Hasan S. S. (2019). The Availability, Pricing, and Affordability of Essential Diabetes Medicines in 17 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 1375. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran D., Ewen M., Lipska K., Hirsch I. B., Yudkin J. S. (2018). Availability and Affordability of Essential Medicines: Implications for Global Diabetes Treatment. Curr. Diab Rep. 18 (8), 48. 10.1007/s11892-018-1019-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron A., Ewen M., Ross-Degnan D., Ball D., Laing R. (2009). Medicine Prices, Availability, and Affordability in 36 Developing and Middle-Income Countries: a Secondary Analysis. Lancet 373 (9659), 240–249. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China YearBooks (2019). Statistical Yearbook of Hubei Province in 2019. Wuhan city: Hubei Provincial Bureau of Statistics. available at: http://tjj.hubei.gov.cn/tjsj/sjkscx/tjnj/qstjnj/ . [Google Scholar]

- Chinese, Government, Chinese, Government. Notice of the State Medical Security Administration on Bringing 17 Anticancer Drugs into Category B of the National Catalogue of Drugs for Basic Medical Insurance, Industrial Injury Insurance and Maternity Insurance ,2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z., Tao Q., Sun G. (2020). Survey and Analysis of the Availability and Affordability of Essential Drugs in Hefei Based on WHO/HAI Standard Survey Methods. BMC Public Health 20 (1), 1405. 10.1186/s12889-020-09477-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorj G., Sunderland B., Sanjjav T., Dorj G., Gendenragchaa B. (2018). Availability, Affordability and Costs of Pediatric Medicines in Mongolia. BMC Pediatr. 18 (1), 149. 10.1186/s12887-018-1123-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden T., Burns E., Freccero P., Renner L., Paintsil V., Dolendo M., et al. (2019). Are Essential Medicines Available, Reliable and Affordable in Low-Middle Income Countries?. J. Cancer Pol. 19, 100180. 10.1016/j.jcpo.2018.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erratum (2020). Erratum: Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70 (4), 313. 10.3322/caac.21609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruqui N., Martiniuk A., Sharma A., Sharma C., Rathore B., Arora R. S., et al. (2019). Evaluating Access to Essential Medicines for Treating Childhood Cancers: a Medicines Availability, price and Affordability Study in New Delhi, India. BMJ Glob. Health 4 (2), e001379. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X., Hu H., Man C., Shi L. (2018). A Survey of Availability, price and Affordability of Essential Medicines from 2011 to 2016 in Chinese Secondary and Tertiary Hospitals. Int. J. Equity Health 17 (1), 158. 10.1186/s12939-018-0870-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan S. S., Kow C. S., Dawoud D., Mohamed O., Baines D., Babar Z. U. (2019). Pharmaceutical Policy Reforms to Regulate Drug Prices in the Asia Pacific Region: The Case of Australia, China, India, Malaysia, New Zealand, and South Korea. Value Health Reg. Issues 18, 18–23. 10.1016/j.vhri.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Yangzheng L., Lin Y. (2018). Evaluation of the Bid-Winning Effect of Centralized Procurement of Medicines in Public Hospitals in 6 central and Southern Provinces or Districts. China Pharm. 29 (15), 2017–2020. [Google Scholar]

- Juxiang C., Hongxuan Z., Shao M. L., Liu M., Lianke L. (2015). Comparison between Gemcitabine Plus Oxaliplatin or S-1 and Singleagent Gemcitabine in the Treatment of Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Anhui Med. Pharm. J. 19 (2), 359–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiyue L., Hui L., Qian J. (2021). Overview and Analysis of National Medical Insurance Negotiation Drugs in Past Years -- Special Topic of Anti-tumor Drugs. Oncol. Pharm. 11 (02), 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kasonde L., Tordrup D., Naheed A., Zeng W., Ahmed S., Babar Z. U. (2019). Evaluating Medicine Prices, Availability and Affordability in Bangladesh Using World Health Organisation and Health Action International Methodology. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19 (1), 383. 10.1186/s12913-019-4221-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanal S., Veerman L., Ewen M., Nissen L., Hollingworth S. (2019). Availability, Price, and Affordability of Essential Medicines to Manage Noncommunicable Diseases: A National Survey from Nepal. Inquiry 56, 46958019887572. 10.1177/0046958019887572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib R., McKee M., Shannon H., Chow C., Rangarajan S., Teo K., et al. (2015). Availability and Affordability of Cardiovascular Disease Medicines and Their Effect on Use in High-Income, Middle-Income, and Low-Income Countries: an Analysis of the PURE Study Data. Lancet 387 (61), 61–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00469-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuluza F., Haefele-Abah C. (2019). The Availability, Prices and Affordability of Essential Medicines in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One 14 (2), e0212125. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuluza F., Heide L. (2017). Availability and Affordability of Antimalarial and Antibiotic Medicines in Malawi. PLoS One 12 (4), e0175399. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunhe L., Wenjun Z., Jianru L. (2017). Analysis of Economic burden of Cancer Patients in Hubei Province. J. Med. Soc. 30 (8), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Lambojon K., Chang J., Saeed A., Hayat K., Li P., Jiang M., et al. (2020). Prices, Availability and Affordability of Medicines with Value-Added Tax Exemption: A Cross-Sectional Survey in the Philippines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (14). 10.3390/ijerph17145242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z., Qiuyun Z., Xuemeng Z. (2020). Investigation and Study on the Accessibility of Antibiotics in Essential Medicine List in Medical Institutions. China Pharm. 31 (11), 1281–1287. 10.6039/j.issn.1001-0408.2020.11.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mao W., Huang Y., Chen W. (2019). An Analysis on Rational Use and Affordability of Medicine after the Implementation of National Essential Medicines Policy and Zero Mark-Up Policy in Hangzhou, China. PLoS One 14 (3), e0213638. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendis S., Fukino K., Cameron A., Laing R., Filipe A., Khatib O., et al. (2007). The Availability and Affordability of Selected Essential Medicines for Chronic Diseases in Six Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 85 (4), 279–288. 10.2471/blt.06.033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengyuan T., Dan C., Yuxiao Z., Xiao Y., Xin F., Jianglin H. (2017). Evaluation of the Affordability of Three Antitumor Targeted Drugs: a Case Study of Hubei Province. Chin. Pharm. 28 (20), 2746–2749. [Google Scholar]

- Moye-Holz D., Ewen M., Dreser A., Bautista-Arredondo S., Soria-Saucedo R., van Dijk J. P., et al. (2020). Availability, Prices, and Affordability of Selected Essential Cancer Medicines in a Middle-Income Country - the Case of Mexico. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20 (1), 424. 10.1186/s12913-020-05167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui S., Zhimei X., Yue L. (2019). A Study on the Availability and Affordability of Anti-tumor Drugs in Public Hospitals--Based on the Data Analysis of the Typical Survey of Public Hospitals in Jiangsu Province. Price Theor. Pract. (5), 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A., Saeed H., Saleem Z., Fang Y., Babar Z. U. (2019). Evaluation of Prices, Availability and Affordability of Essential Medicines in Lahore Division, Pakistan: A Cross-Sectional Survey Using WHO/HAI Methodology. PLoS One 14 (4), e0216122. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar M. R., Iftikhar S., Saqib A. (2018). Availability of Anticancer Medicines in Public and Private Sectors, and Their Affordability by Low, Middle and High-Income Class Patients in Pakistan. BMC Cancer 18 (1), 14. 10.1186/s12885-017-3980-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaoqing L. (2019). The Status Quo and Dilemma, hope and Way Out of Cancer–Based on the analysis of the global cancer incidence, prevention and control situation in 2017 and 2018. Med. Philos. 40 (12), 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. K., Nicolla J., Zafar S. Y. (2014). Bridging the gap between financial distress and available resources for patients with cancer: a qualitative study. J. Oncol. Pract. 10 (5), e368–72. 10.1200/JOP.2013.001342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng J. P., Yang Z. Y., Zhu Y. M., Ni D., Zhu Z. J., Li X. Q. (2018). Gemcitabine and cisplatin for treatment of lung cancer In Vitro and vivo. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 22 (12), 3819–3825. 10.26355/eurrev_201806_15266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Gong S., Cai H., Ding Y. (2018). The availability, price and affordability of essential antibacterials in Hubei province, China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 (1), 1013. 10.1186/s12913-018-3835-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahong L. (2019). Study on Family Burden, Quality of Life and Influencing Factors of Lung Cancer Patients in a Cancer Hospital. Lanzhou City: Lan Zhou University. [Google Scholar]

- Yf D. Research on Public Security Policy and Drug Accessibility Evaluation of Novel Antitumor Drugs in China. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Wang Y., Sun X., Li X. (2019). Availability, Price and Affordability of Anticancer Medicines: Evidence from Two Cross-Sectional Surveys in the Jiangsu Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 (19), 3728. 10.3390/ijerph16193728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.