Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 4

We have edited the manuscript according to the recommendation of the reviewers. Some general updates to Geographical Regions and Operational Definition of Diarrhea were made. Rational of the study had been clearly mentioned and improved. Its study method and statistical analysis had been clearly detailed. In-depth discussion of key findings in Discussion part had been improved.

Abstract

Background: Diarrhea diseases remain the leading cause of death among children under-five in lower and lower-middle-income countries. This study was conducted to investigate the factors related to diarrhea among children aged 12 to 35 months in Cambodia.

Methods: We analyzed cross-sectional data from the Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2014 using a combination of household and children’s datasets. A generalized linear mixed model was used to analyze the determinant factors of diarrhea.

Results: The survey included 2,828 children aged 12 to 35 months. The prevalence of diarrhea in the last 2 weeks was 16.44% (95% CI: 14.72%-18.31%). Factors significantly associated with childhood diarrhea were: maternal unemployment (AOR = 1.43; 95% CI: 1.14-1.78); the child being male (AOR = 1.25; 95%CI: 1.02-1.53); the presence of unimproved toilet facilities (AOR = 1.17; 95%CI: 1.05-1.31); and unhygienic disposal of children’s stools (AOR = 1.32; 95%CI: 1.06-1.64) when controlling for other covariates. Both maternal age (one year older; AOR = 0.85; 95%CI: 0.78– 0.93) and child age (one month older; AOR = 0.86; 95%CI: 0.78-0.94) had significant negative associations with the occurrence of childhood diarrhea.

Conclusion: Childhood diarrhea remains a public health concern in Cambodia. Intervention programs should focus on reducing diarrheal diseases by constructing improved toilet facilities and promoting behavior to improve hygiene, specifically targeting younger mothers.

Keywords: Prevalence, child, diarrhea, cross-sectional study, Cambodia

Introduction

Diarrhea is the second leading cause of death in children under the age of five years, with an estimated 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrhea and 525,000 deaths caused by diarrhea each year 1, 2 . Globally, 88% of diarrhea cases are attributable to poor water, poor sanitation or poor hygiene 3 . Childhood diarrhea is associated with multiple factors, including unimproved drinking water sources 4– 7 , untreated water 8– 10 , unimproved toilet facilities 6, 8, 9, 11 , unhygienic disposal of children’s stools 12– 14 , lack of hand washing facilities 15, 16 , type and location of residence 11, 16 , the child’s age 4, 13, 16 , the child’s sex (male) 13 , maternal illiteracy 12, 13, 17 , the mother’s occupation 9, 12 , maternal age 14, 18 , wealth index 4, 19 , and whether or not the child is breastfed 10, 15 .

In 2014, Cambodia still had one of the highest prevalence levels of diarrhea among children under the age of five amongst countries in South-East Asia, at 12.8% 20 . By comparison, Myanmar had a prevalence of 10.4% in 2015–16 21 , Malaysia 4.4% in 2016 7 , Laos 6.5% in 2017 22 , Philippines 6.1% in 2017 23 , and Indonesia 14.1% in 2017 24 . According to a 2014 report from UNICEF Cambodia, diarrhea alone accounted for one fifth of the deaths of children under the age of five in Cambodia, and an estimated 10,000 deaths overall each year 25 . However, according to a 2018 report from UNICEF, in 2016, Cambodia had 5,947 total neonatal deaths, of which 20 were due to diarrhea; 5,248 post-neonatal deaths, of which 672 were due to diarrhea (13%); and 692 deaths of children under five due to diarrhea (6%) 26 . This demonstrates that diarrhea is the most common cause of death in Cambodian children. According to the Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey (CDHS) 2014, the prevalence of diarrhea among children aged 12 to 35 months was high compared with other age groups and this age period is known to be crucial for child development and growth 20 .

It is of great importance to understand the factors related to the prevalence of diarrhea among children aged 12 to 35 months. There are no existing studies on the factors affecting the prevalence of diarrhea in this age group, and no national studies on the factors associated with childhood diarrhea in Cambodia have yet been published. This study was therefore conducted to investigate the factors associated with diarrhea among children aged 12 to 35 months in Cambodia.

Methods

Ethical statement

This research project received approval from the Khon Kean University Ethics Committee in Human Research (HE632097). This study uses existing CDHS data and re-analysis was done under the original consent provided by the participants.

CDHS 2014

The CDHS 2014 collected data nationally across the country, which is subdivided into 19 province domains. Its sampling frame consisted of 28,455 eligible enumeration areas (EAs), which comprised the 2008 Cambodian General Population Census (GPC). The sample was proportionately allocated to urban and rural in each domain with a power allocation preventing the oversampling of urban, areas, in order to represent the fact that Cambodia is mainly rural. The stratified sample was selected in two stages. In the first stage, a fixed number of EAs were chosen using probabilities weighted proportional to the size of the EA. In the second stage, 24 and 28 households were picked up from every urban cluster and rural cluster, respectively, through a systematic sampling process with equal probability weighting. 15,825 households, 17,578 women, and 5,190 men were interviewed between the 2 nd June and the 12 th December, 2014, across the country; further details can be found in the CDHS 2014 report 20 .

Population and Sample size

Among 7,044 children aged under five years, in our analysis, we included only children aged 12 to 35 months (n=2,828) due to the high prevalence of diarrhea among this age group compared to other age groups. We analyzed the sample power and it was found to provide a suitable degree of power, and was sufficient for this study (0.9627, 0.9682).

Data use

Two raw CDHS 2014 datasets, comprising household data and children’s data, were combined for use in this analytical cross-sectional study. All entries and variables in these datasets were included in the study.

Dependent variable

The operational definition of diarrhea used by the CDHS was the occurrence of three or more loose or liquid bowel movements over a 24 hour period, as reported by the mother/caregiver, in any given 24 hour period during the preceding 2 weeks, as described in a French article 27 cited by, and in agreement with, multiple other sources 1, 9 . The prevalence of diarrhea was the dependent variable considered in this study. This is referred to the questionnaire thus: “Has (NAME) had diarrhea in the last 2 weeks?” The dichotomous variable childhood diarrhea can take values “1” representing a response of “yes” or “0” representing “no” and “don’t know” responses.

Independent variables

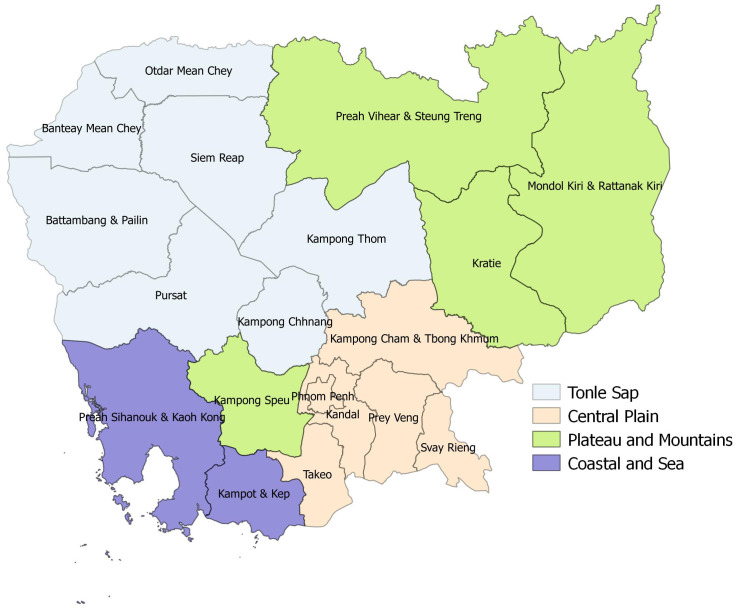

Socio-demographic characteristics take the form of continuous variables such as maternal age, child’s age, and number of household members and categorical variables such as maternal education (no education/primary/secondary/higher), maternal occupation (employed/unemployed), mother’s knowledge of oral rehydration salts (ORS) (good/poor) 28 , exposure to media (yes/no) 29 , sex of the child, breastfeeding (ever/never), deworming (yes/no) 28 , vaccination (ever/never), residence (urban/rural) and wealth index (poorest/poorer/middle/richer/richest) 28 . CDHS data were organized in 19 province domains, which we regrouped into four regions: Central Plain; Tonle Sap; Coastal and Sea; and Plateau and Mountains 30 ( Figure 1). Environmental characteristics were also treated as categorical variables, including drinking water source (improved/unimproved) 31 , whether or not the same source of drinking water was used during wet and dry seasons (same/different), whether or not water was treated before drinking (always/no), type of toilet facility (improved/unimproved) 31 , hygiene (adequate/inadequate) 31 , and disposal of children’s stools (sanitary/unsanitary) 32 . The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) were used to classify each WASH facility as either improved or unimproved, and either sanitary or unsanitary according to the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme ( Table 1 and Table 2) 31, 32

Figure 1. Geographical regions in Cambodia.

Table 1. Joint Monitoring Programme classification of improved and unimproved water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) 31 .

Please note this table has been reproduced with permission from UNICEF

| Service | Improved | Unimproved |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking

water |

Piped water, boreholes or tube wells, protected dug wells,

protected springs, rainwater, and packaged or delivered water, and provided collection time is not more than 30 minutes for a round trip, including queuing |

Unprotected dug well, unprotected spring, surface

water (river, reservoirs, lakes, ponds, streams, canals, and irrigation channels). |

| Sanitation | Flush and pour flush connected to piped sewer, septic tanks

or pit latrines; ventilated improved pit (VIP) latrine, composting toilets or pit latrines with slabs, and that are not shared with other households |

Flush and pour flush not to sewer/septic tank/pit

latrine, pit latrine without slab/open pit, bucket, hanging toilet/hanging latrine, no facility/bush/field |

| Hygiene | Availability of a handwashing facility on premises with soap and

water |

No handwashing facility on premises |

Table 2. Joint Monitoring Programme classification of sanitary and unsanitary disposal of children stool 32 .

Please note this table has been reproduced with permission from UNICEF

| Sanitary | Unsanitary |

|---|---|

| Child used toilet or latrine

Put or rinsed in the toilet or latrine Buried |

Put or rinsed into drain or ditch

Throw into the garbage Left in the open or not disposed of Other |

Statistical analysis

Statistical data analyses were performed using STATA/SE 14.0 33 as follows.

Categorical variables were analyzed using frequency and percentage. Continuous variables were analyzed as means, standard deviations, and ranges. A weighting variable was used in the form of the woman’s individual sample weighting. Cross-tabulations were run with the appropriate sample weights to provide nationally representative results 19 . The svyset command was used to test for complex survey sampling methods used in the original surveys, in order to adjust for differences in the probabilities of sample selection and to avoid using over-sampled strata within the survey data 28 .

The prevalence of diarrhea was estimated as a percentage. The numerator was the number of living children aged 12 to 35 months with an occurrence of diarrhea during the two weeks preceding the interview (i.e. an answer “yes” to, “Has (NAME) had diarrhea in the last 2 weeks?”) and the denominator was the number of living children aged 12 to 35 months.

A bivariate analysis with simple logistic regression was performed using the svyset ( svy command). A linearity test was conducted between the continuous variable and dependent variable. Variables associated with diarrhea in the bivariate analyses at a level of p<0.25 were included in the multivariable model 34, 35 . Multicollinearity assessment of the independent variables was performed by excluding those with a variance inflation factor (VIF) greater than four 36 . Finally, a multivariable analysis was performed using a generalized mixed linear model with four regions picked as ‘random effects’ corresponding to the various clusters in the sampling design 37 . The backward stepwise procedure was applied as the model fitting strategy. Statistical significance was considered at a threshold of p<0.05 and the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was considered as the magnitude of the effect.

The result was used to map geographical regions in Cambodia, applied using the free and open source geographic information system, QGIS V 2.18.4.

Results

The majority of the children (84.12%) lived in rural areas. Nearly half (44.03%) lived in Central Plain and one third (33.32%) lived in Tonle Sap. The mean maternal age was 28.27 years (standard deviation, SD = 5.89). More than half the mothers (51.08%) attended primary school. Three quarters (75.10%) of the mothers were employed and the average number of household members was five. More than half (51.18%) of the children were male and the mean age was 23.33 months (SD = 6.79). Almost all (96.17%) children had been breastfed; 59.60% had received deworming treatment. Out of 2,828 households, more than half (54.07%) always had treated water to drink; 57.97% had an unimproved toilet facility; while 68.01% used adequate hygiene; and 70.25% used sanitary disposal of children’s stool ( Table 3).

Table 3. Socio-demographic and environmental characteristics of households in Cambodia, 2014 (n=2,828).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 16–24 | 397 | 14.04 |

| 25–34 | 1591 | 56.26 |

| 35–49 | 840 | 29.70 |

| Mean±SD | 28.27±5.89 | |

| Range | 16 to 49 | |

| Education | ||

| No education | 366 | 12.96 |

| Primary | 1445 | 51.08 |

| Secondary | 921 | 32.58 |

| Higher | 96 | 3.38 |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed | 2124 | 75.10 |

| Unemployed | 704 | 24.90 |

|

Knowledge of oral rehydration

salts |

||

| Good | 2717 | 96.05 |

| Poor | 111 | 3.95 |

| Exposure to media | ||

| Yes | 1808 | 63.92 |

| No | 1020 | 36.08 |

| Children’s characteristics | ||

| Age (months) | ||

| 12–23 | 1460 | 51.64 |

| 24–35 | 1368 | 48.36 |

| Mean±SD | 23.33±6.79 | |

| Range | 12 to 35 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1448 | 51.18 |

| Female | 1381 | 48.82 |

| Breastfeeding status | ||

| Ever | 2720 | 96.17 |

| Never | 108 | 3.83 |

| Deworming | ||

| Yes | 1686 | 59.60 |

| No | 1142 | 40.40 |

| Household characteristics | ||

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 449 | 15.88 |

| Rural | 2379 | 84.12 |

| Region | ||

| Coastal and Sea | 169 | 5.98 |

| Tonle Sap | 942 | 33.32 |

| Central Plain | 1245 | 44.03 |

| Plateau and Mountains | 472 | 16.67 |

| Number of household members | ||

| 1–4 | 969 | 34.28 |

| >4 | 1859 | 65.72 |

| Mean±SD | 5.73±2.31 | |

| Range | 1 to 22 | |

| Wealth index | ||

| Poorest | 672 | 23.76 |

| Poorer | 523 | 18.49 |

| Middle | 550 | 19.44 |

| Richer | 493 | 17.45 |

| Richest | 590 | 20.86 |

| Environmental characteristics | ||

|

Drinking water during dry

season |

||

| Improved | 1745 | 61.71 |

| Unimproved | 1083 | 38.29 |

|

Drinking water during wet

season |

||

| Improved | 2320 | 82.02 |

| Unimproved | 508 | 17.98 |

|

Same source of drinking water

during wet and dry season |

||

| Same | 1955 | 69.11 |

| Different | 873 | 30.89 |

| Treating water to drink | ||

| Yes, always | 1529 | 54.07 |

| No | 1299 | 45.93 |

| Toilet facility | ||

| Improved | 1189 | 42.03 |

| Unimproved | 1640 | 57.97 |

| Hygiene | ||

| Adequate | 1923 | 68.01 |

| Inadequate | 905 | 31.99 |

| Disposal of children’s stool | ||

| Sanitary | 1987 | 70.25 |

| Unsanitary | 841 | 29.75 |

SD, standard deviation.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with childhood diarrhea in Cambodia

The result from the bivariable analyses revealed that as maternal age increased by a year, the odds of the child suffering from diarrhea decreased 18% (COR = 0.82; 95%CI: 0.73– 0.92; p<0.001). The odds of suffering from diarrhea were 49% higher (COR = 1.49; 95% CI: 1.11-1.98; p=0.007) in children whose mother was unemployed compared to employed. As the child’s age increased by a month, the odds of the child suffering from diarrhea decreased 17% (COR = 0.83; 95%CI: 0.75-0.92; p<0.001). The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 20% higher (COR = 1.20; 95%CI: 1.04-1.39; p=0.013) in children living in a household with unimproved toilet facilities compared with those with improved toilet facilities. The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 40% higher (COR = 1.40; 95%CI: 1.05-1.87; p=0.020) in children whose stools were disposed of unhygienically compared to children whose stools were disposed of hygienically ( Table 4). Further, the child’s sex, the number of household members, wealth index, source of drinking water during dry season, whether or not the same source of drinking water was used during wet and dry seasons, and the treatment/non-treatment of drinking water did not reach significance but did meet the pre-determined threshold of p<0.25 for inclusion in the multivariable model. Finally, region (p<0.25) also met the criteria for inclusion in the multivariable model and was used as a random effect. As such, the multivariable analysis was conducted using a generalized mixed linear model with each of the four regions of Cambodia treated as random effects.

Table 4. Bivariate analysis of factors associated with childhood diarrhea in Cambodia, 2014 (n=2,828).

| Variables | Number | Diarrhea

% |

COR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 2828 | 16.44 | 14.72-18.31 | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 2828 | N/A | 0.82 | 0.73-0.92 | <0.001 |

| Maternal education | 0.681 | ||||

| Literate | 2462 | 16.29 | 1 | ||

| Illiterate | 366 | 17.46 | 1.09 | 0.73-1.62 | |

| Maternal occupation | 0.007 | ||||

| Employed | 2124 | 15.00 | 1 | ||

| Unemployed | 704 | 20.78 | 1.49 | 1.11-1.98 | |

|

Mother’s knowledge of oral

rehydration salts |

0.481 | ||||

| Good | 2717 | 16.61 | 1 | ||

| Poor | 111 | 12.21 | 0.69 | 0.25-1.90 | |

| Mother’s exposure to media | 0.502 | ||||

| Yes | 1808 | 15.99 | 1 | ||

| No | 1020 | 17.23 | 1.09 | 0.84-1.42 | |

| Child’s age (months) | 2828 | N/A | 0.83 | 0.75-0.92 | <0.001 |

| Child’s sex | 0.075 | ||||

| Female | 1381 | 14.86 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1448 | 17.94 | 1.25 | 0.97-1.61 | |

| Breastfeeding status | 0.268 | ||||

| Ever | 2720 | 16.64 | 1 | ||

| Never | 108 | 11.42 | 0.64 | 0.29-1.40 | |

| Deworming | 0.504 | ||||

| Yes | 1686 | 16.91 | 1 | ||

| No | 1142 | 15.75 | 0.91 | 0.71-1.17 | |

| Residence | 0.561 | ||||

| Urban | 449 | 15.39 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 2379 | 16.64 | 1.10 | 0.80-1.50 | |

| Region | 0.203 | ||||

| Coastal and Sea | 169 | 12.36 | 1 | ||

| Tonle Sap | 942 | 15.55 | 1.31 | 0.82-2.07 | |

| Central Plain | 1245 | 16.92 | 1.44 | 0.92-2.25 | |

| Plateau and Mountains | 472 | 18.40 | 1.60 | 1.02-2.51 | |

|

Number of household

members |

0.095 | ||||

| >4 | 1859 | 15.38 | 1 | ||

| 1–4 | 969 | 18.47 | 1.25 | 0.96- 1.62 | |

| Wealth index | 0.128 | ||||

| Richest | 590 | 14.44 | 1 | ||

| Richer | 493 | 17.40 | 1.25 | 0.82-1.90 | |

| Middle | 550 | 14.65 | 1.02 | 0.67-1.55 | |

| Poorer | 523 | 14.50 | 1.00 | 0.67-1.50 | |

| Poorest | 672 | 20.46 | 1.52 | 1.03-2.26 | |

|

Drinking water during dry

season |

0.065 | ||||

| Improved | 1745 | 15.12 | 1 | ||

| Unimproved | 1083 | 18.56 | 1.28 | 0.98-1.66 | |

|

Drinking water during wet

season |

0.676 | ||||

| Improved | 2320 | 16.27 | 1 | ||

| Unimproved | 508 | 17.22 | 1.07 | 0.78-1.48 | |

|

Same source of drinking water

during wet and dry season |

0.161 | ||||

| Same | 1955 | 15.56 | 1 | ||

| Different | 873 | 18.40 | 1.22 | 0.92-1.62 | |

| Treating water to drink | 0.139 | ||||

| Yes, always | 1529 | 15.28 | 1 | ||

| No | 1299 | 17.81 | 1.20 | 0.94-1.53 | |

| Toilet facility | 0.013 | ||||

| Improved | 1189 | 13.61 | 1 | ||

| Unimproved | 1640 | 18.49 | 1.20 | 1.04-1.39 | |

| Hygiene | 0.995 | ||||

| Adequate | 1923 | 16.44 | 1 | ||

| Inadequate | 905 | 16.43 | 0.99 | 0.74-1.34 | |

| Disposal of children’s stool | 0.020 | ||||

| Sanitary | 1987 | 14.99 | 1 | ||

| Unsanitary | 841 | 19.85 | 1.40 | 1.05-1.87 |

COR, crude odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with childhood diarrhea in Cambodia

The multivariable analysis ( Table 5) showed that as maternal age increased by a year, the odds of the child suffering from diarrhea decreased 15% (AOR = 0.85; 95%CI: 0.78– 0.93; p=0.001). The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 43% higher (AOR = 1.43; 95% CI: 1.14-1.78; p=0.002) in children whose mother was unemployed compared to employed. As the child’s age increased by a month, the odds of the child suffering from diarrhea decreased 14% (AOR = 0.86; 95%CI: 0.78-0.94; p=0.001). The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 25% higher (AOR = 1.25; 95%CI: 1.02-1.53; p=0.031) in males compared to females. The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 17% higher (AOR = 1.17; 95%CI: 1.05-1.31; p=0.004) in children living in a household with unimproved toilet facilities compared with those with improved toilet facilities. The odds of suffering from diarrhea was 32% higher (AOR = 1.32; 95%CI: 1.06-1.64; p=0.011) in children whose stools were disposed of unhygienically compared to children whose stools were disposed of hygienically.

Table 5. Multivariable analysis of factors associated with childhood diarrhea in Cambodia, 2014 using generalized mixed linear model (n=2,828).

| Variables | Number | Diarrhea

% |

AOR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 2828 | N/A | 0.85 | 0.78-0.93 | 0.001 |

| Maternal occupation | 0.002 | ||||

| Employed | 2124 | 15.00 | 1 | ||

| Unemployed | 704 | 20.78 | 1.43 | 1.14-1.78 | |

| Child’s age (months) | 2828 | N/A | 0.86 | 0.78-0.94 | 0.001 |

| Child’s sex | 0.031 | ||||

| Female | 1381 | 14.86 | 1 | ||

| Male | 1448 | 17.94 | 1.25 | 1.02-1.53 | |

| Toilet facility | 0.004 | ||||

| Improved | 1189 | 13.61 | 1 | ||

| Unimproved | 1640 | 18.49 | 1.17 | 1.05-1.31 | |

| Disposal of children’s stool | 0.011 | ||||

| Sanitary | 1987 | 14.99 | 1 | ||

| Unsanitary | 841 | 19.85 | 1.32 | 1.06-1.64 |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This is the first study to report factors associated with diarrhea in children aged 12 to 35 months at the national level in Cambodia. Younger maternal age, maternal unemployment, younger child age, being male, lack of unimprovement to toilet facilities, and unhygienic disposal of children’s stools were found to be associated with childhood diarrhea.

Socio-demographic characteristics such as maternal age were significantly associated with reduced incidence of diarrhea, in line with studies conducted in Brazil that found younger mothers to be associated with a higher prevalence of diarrhea among their children 18 . It is likely that older mothers have more experience in childcare and feeding. The association of maternal unemployment with the incidence of diarrhea is consistent with a study in Senegal that found children of housewives to have a higher risk of diarrhea compared to children of women who worked in the public or private sector 9 . It is likely that the employment status of the mother will improve a child’s quality of living standards and as well as improving hygienic practice and sanitation in the home during feeding and childcare. The child’s age had a significant, negative association with the incidence of diarrhea, in line with many studies in Ethiopia and Tanzania 4, 14, 16 . This might be due to the development of the immune system throughout childhood. Males were more likely to suffer from diarrhea than females, which may simply reflect a natural predisposition of males to develop diarrhea more frequently than females 38 , and is also supported by a previous study conducted in India 13 .

Environmental characteristics such as the lack of improvements to toilet facilities were significantly associated with the incidence of diarrhea, consistent with many studies including a systematic review 4, 6, 8, 11 . Finally, disposal of children’s stools was significantly associated with the incidence of diarrhea, consistent with previous studies in Ethiopia, India, and Tanzania 12– 14 . The present findings demonstrate that the quality of sanitation facilities strongly influences the prevalence of childhood diarrhea. Increasing the number of toilet facilities that receive improvements is likely to reduce direct contact with children’s stools, and consequently reduce the occurrence of childhood diarrhea in Cambodia.

A limitation of this research study was that it used a cross-sectional design with just one outcome measure (diarrhea prevalence) taken as a snapshot at a given point in time and cannot be used to infer a causal relationship. Future longitudinal studies may improve on this. The CDHS 2014 was not fully comprehensive in that it did not cover the WASH factors of hand washing before preparing meals and after defecating. The inclusion of these questions in the survey would give a more comprehensive analysis of hygiene practices in the population. Despite all efforts to prevent bias in the data collection process, the use of self-reporting measures and recall bias may have had an effect on the study findings. Further, the CDHS 2014 captured data by household, rather than by individual person, which may introduce a confound in that it has a tendency to under-estimate the quality of both drinking water source and sanitation facility available.

Conclusion and recommendations

Diarrhea still remains a public health concern among children in Cambodia. The probability of developing diarrhea is strongly associated with maternal unemployment, being male, not having access to improved toilet facilities, or practicing hygienic disposal of children’s stools. Conversely, increasing maternal and child age is associated with a reduction in the probability of developing diarrhea.

”Based on these findings, the authors provide the following recommendations.

National: The WASH program should prioritize their efforts in reaching out to younger mothers, mothers of younger children, boys, and unemployed mothers. Guidance should include the use of sanitary methods for disposing of children’s stool, as well as water treatment methods, the importance of practicing good sanitation, and maintaining one’s health. Intervention programs should focus on the construction of new sanitary toilet facilities, making improvements to existing toilet facilities, and promoting hygienic behaviors.

Local: Younger mothers should be encouraged to enroll in health education programs. Additional community sanitation facilities should be constructed, and existing facilities should be improved and properly maintained to ensure continued access to sanitation.

Future study: Longitudinal studies are needed to measure the impact of these interventions on multiple aspects of public health, not necessarily limited to the incidence of diarrhea in children.

Data availability

Our study used raw children’s and household data from the DHS, Cambodia 2014. Data are free to access for research purposes and can be obtained through the DHS Program after registering and obtaining an approval letter from the Inner City Fund (ICF) ( https://dhsprogram.com/data/Access-Instructions.cfm).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere thanks and appreciation to:

Dr. Kavin Thinkhamrop, Health and Epidemiology Geoinformatics Research (HEGER), Faculty of Public Health, Khon Kaen University; Dr. Wilaiphorn Thinkhamrop, Data Management and Statistical Analysis Center (DAMASAC), Faculty of Public Health, Khon Kaen University for their statistical support; and Rebecca S Dewey, University of Nottingham for language editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 5; peer review: 2 approved]

References

- 1. World Health Organization: Diarrhoeal disease.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. : Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2151–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prüss-Üstün A, Bos R, Gore F, et al. : Safer water, better health: costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2008.2008. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azage M, Kumie A, Worku A, et al. : Childhood diarrhea in high and low hotspot districts of Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel modeling. J Health Popul Nutr. 2016;35:13. 10.1186/s41043-016-0052-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kapwata T, Mathee A, Le Roux WJ, et al. : Diarrhoeal Disease in Relation to Possible Household Risk Factors in South African Villages. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):E1665. 10.3390/ijerph15081665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yaya S, Hudani A, Udenigwe O, et al. : Improving Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Practices, and Housing Quality to Prevent Diarrhea among Under-Five Children in Nigeria. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2018;3(2):E41. 10.3390/tropicalmed3020041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aziz FAA, Ahmad NA, Razak MAA, et al. : Prevalence of and factors associated with diarrhoeal diseases among children under five in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study 2016. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1363. 10.1186/s12889-018-6266-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Godana W, Mengistie B: Determinants of acute diarrhoea among children under five years of age in Derashe District, Southern Ethiopia. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13(3):2329. 10.22605/RRH2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thiam S, Diène AN, Fuhrimann S, et al. : Prevalence of diarrhoea and risk factors among children under five years old in Mbour, Senegal: a cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):109. 10.1186/s40249-017-0323-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Acharya D, Singh JK, Adhikari M, et al. : Association of water handling and child feeding practice with childhood diarrhoea in rural community of Southern Nepal. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(1):69–74. 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alebel A, Tesema C, Temesgen B, et al. : Prevalence and determinants of diarrhea among under-five children in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199684. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sinmegn Mihrete T, Asres Alemie G, Shimeka Teferra A: Determinants of childhood diarrhea among underfive children in Benishangul Gumuz Regional State, North West Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):102. 10.1186/1471-2431-14-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bawankule R, Singh A, Kumar K, et al. : Disposal of children’s stools and its association with childhood diarrhea in India. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):12. 10.1186/s12889-016-3948-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwin P, Azage M: Geographical Variations and Factors Associated with Childhood Diarrhea in Tanzania: A National Population Based Survey 2015–16. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2019;29(4):513–24. 10.4314/ejhs.v29i4.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dagnew AB, Tewabe T, Miskir Y, et al. : Prevalence of diarrhea and associated factors among under-five children in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):417. 10.1186/s12879-019-4030-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mengistie B, Berhane Y, Worku A: Prevalence of diarrhea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age in Eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Open J Prev Med. 2013;03(07):446–53. 10.4236/ojpm.2013.37060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gebru T, Taha M, Kassahun W: Risk factors of diarrhoeal disease in under-five children among health extension model and non-model families in Sheko district rural community, Southwest Ethiopia: comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):395. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vasconcelos MJOB, Rissin A, Figueiroa JN, et al. : Factors associated with diarrhea in children under five years old in the state of Pernambuco, according to surveys conducted in 1997 and 2006. Rev Saude Publica. 2018;52:48. 10.11606/s1518-8787.2018052016094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rutstein SO, Staveteig S, Winter R, et al. : Urban Child Poverty, Health, and Survival in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.DHS Comparative Reports No. 40. Rockville, Maryland, USA;2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kosal S, Satia C, Kheam T, et al. : Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey 2014.Phnom Penh: National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health, and ICF International.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS), ICF: Myanmar Demographic Household Survey 2015–16. Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, and Rockville, Maryland USA;2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lao Statistics Bureau: Lao Social Indicator Survey II 2017, Survey Findings Report. Vientiane, Lao PDR;2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 23. Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), ICF: Philippines National Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Quezon City, Philippines, and Rockville, Maryland, USA;2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Population and Family Planning Board (BKKBN), Statistics Indonesia (BPS), Ministry of Health (Kemenkes) et al. : Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey 2017. Jakarta, Indonesia;2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 25. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF): Water, sanitation, and hygiene. Unicef,2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 26. United Nations Children’s Fund: Diarrhoeal disease | Diarrhoea as a cause of death in children under 5. Unicef,2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 27. ANSD, ICF International: Sénégal: Enquête Démographique et de Santé Continue (EDS-Continue 2014).Rockville: Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie (ANSD) et ICF International;2015. (in French). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 28. Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK: Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA ICF,2018;22–51. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westoff CF, Bankole A: Mass media and reproductive behaviour in Africa. DHS Analytical Reports no. 2,1997. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministry of Planning: General Population Census of the Kingdom of Cambodia 2019.2019. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 31. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization: Core questions on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene for household surveys: 2018 update. New York;2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 32. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization: Core questions on drinking-water and sanitation for household surveys. World Health Organization.2006. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 33. StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression, Second Edition. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.2000;1–369. 10.1002/0471722146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX: Applied Logistic Regression Analysis, Third Edition. The Statistician. New York, United States: John Wiley & Sons Inc;2013;528. 10.1002/9781118548387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hair JF, Jr, Black WC, Babin BJ, et al. : Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Edition). 7th edition. Pearson Education Limited. Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education Limited;2014;740. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R: Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications.New York, NY 10017 and Oxon, OX14 4RN: Routledge;2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization: Addressing sex and gender in epidemic-prone infectious diseases.2007;1–46. Reference Source [Google Scholar]