Abstract

Intermittent injections of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and mechanical loading are both known to effect a net increase in bone mass. Fundamentally, bone metabolism can be divided into modeling (uncoupled formation or resorption) and remodeling (subsequent formation biologically coupled to resorption in space and time). Methods to delineate the bone response between these regimes are scant but have garnered recent attention and acceptance, and will be critical tools to properly assess short- and long-term efficacy of osteoporosis treatments. To this end, we employ a time-lapse micro-computed tomography strategy to quantify and localize modeling and remodeling volumes over four weeks of concurrent PTH treatment and mechanical loading. Modeled and remodeled volumes are probed for differences with respect to treatment, loading, and interactions thereof in trabecular and cortical bone compartments, which were further separated by plate/rod microarchitecture and periosteal/endosteal surfaces, respectively. Loading effects are further considered independently with regard to localized strain environments. Our findings indicate that in trabecular bone, PTH and loading stimulate anabolic modeling additively, and remodeling synergistically. PTH tends to lead to bone accumulation indiscriminate of trabecular microarchitecture, whereas loading tends to more strongly affect plates than rods. The cortical surfaces responded uniquely to PTH and loading, with synergistic effects on the periosteal surface for anabolic modeling, and on the endosteal surface for catabolic modeling. The increase in catabolic modeling due to loading, which is enhanced by PTH, is concentrated to areas of the endosteal surface under low strain and to our knowledge has not previously been reported. Taken together, the effects of PTH, loading, and their interactions, are shown to be dependent on the specific bone compartment and metabolic regime; this may explain some discrepancies in previously-reported findings.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is characterized by low bone mass and/or deteriorations in bone microstructure that can leave patients more susceptible to debilitating and costly fragility fractures. The total cost of osteoporosis to patients, families, and the healthcare system was estimated at around $57 billion in 2018 and is expected to nearly double by 20401. Intermittent injections of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and mechanical loading have both been shown to provide benefits to overall bone mass; however, some questions persist regarding their specific mechanisms of action. Furthermore, both have been suggested to have a limited duration of effectiveness. There is evidence that mechanical responsiveness decreases with age2, and current clinical guidelines do not recommend PTH treatment for longer than two years3. Current literature on how, when, and where these two therapies can produce a synergistic effect (i.e. an enhancement) even beyond an independent, additive effect in improving bone health is currently sparse and includes discrepancies.

PTH was granted clinical approval by the FDA for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis in 20024. It was initially seen as somewhat of a paradoxical solution, since it was known clinically that elevated levels of PTH (found in patients with hyperparathyroidism) tended to be associated with reduced bone mineral density and increased fracture risk4. However, net anabolic effects were observed with intermittent dosages and histological studies confirmed bone formation immediately following PTH injections, largely tied to increased osteoblast number5–9. Numerous studies have addressed the dichotomous outcomes of intermittent and continuous PTH administration10–13 and importantly for preclinical research, methods to mimic the anabolic clinical effects in mouse models have been established14–16.

The effect of mechanical loading on bone has a more storied history, dating back over a century to Wolff’s Law positing that bone adjusts its size and shape to meet mechanical demands17. Landmark clinical studies have recently highlighted significantly thicker bones in the dominant (more frequently- and heavily-loaded) arms of tennis18 and baseball19 players. Importantly for preclinical research, these phenomena have also been reproduced using in vivo mouse loading studies16,20–22. More recently, specific structures23 and proteins24,25 tied to the inner workings of mechanoadaptation have sparked curiosity with regard to the roles they play and whether they are independent, critical, or complimentary in function. As an additional non-invasive therapeutic option, it remains to be determined how mechanical loading specifically stimulates proteins in localized bone regions as a way to improve bone mass clinically.

There are two basic and distinct regimes through which alterations in bone mass are executed: remodeling and modeling26,27. Bone remodeling represents the standard turnover that occurs throughout life. Bone resorption by osteoclasts is followed by bone formation by osteoblasts on the same surface, and is thus coupled in time and space. The specific coupling factors have been the subject of debate, with particularly compelling evidence surrounding transforming growth factor β and insulin like growth factors stored in the matrix and released during resorption to recruit preosteoblastic mesenchymal stem cells28. PTH is also among the factors known to be involved in the regulation of bone remodeling29. Bone modeling simply refers to uncoupled formation or resorption. The process of uncoupled formation, or anabolic modeling, is typical and necessary for early development, but is more restricted to specific stimuli (such as loading) beyond adolescence30. However, it makes for a naturally attractive therapeutic route to accelerate bone gain, and has only recently begun to be specifically considered and targeted in osteoporosis therapies5,30,31. Catabolic modeling, or uncoupled resorption wherein the anticipated bone formation is absent, has received the least attention of the three described processes in literature. Outside of accelerating a widening of the marrow cavity in the diaphyses of long bones, the functional or evolutionary benefits are not obvious. Nevertheless, as a corollary to uncoupled formation with the abovementioned biological relevance, it should be considered. In light of past findings and the basic science and clinical importance of modeling and remodeling, it is critical to be able to identify changes in bone mass according to which of the regimes they are executed in order to more thoroughly evaluate the overall efficacy of the treatment.

To this end, in this study we use weekly in vivo micro-computed tomography (μCT) to monitor changes in bone volume in response to combined PTH and mechanical loading. Using image registration to align the weekly scans, volumes formed or resorbed are classified as modeling- or remodeling-based using preceding and/or subsequent formation/resorption events to identify the spatiotemporal coupling effect. Modeling and remodeling events are quantified and then further segregated by distinct, strain-unique trabecular and cortical structures on which they occur to provide further insight into the relationship between these stimuli and specific local mechanical cues.

Methods

Mice

Female C57Bl/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, Stock No. 000664) at 14 weeks of age, and allowed to acclimate two additional weeks in house prior to the start of experimental treatment. Mice were housed 3–4 per cage, randomly assigned to treatment groups (n=6/group), and weighed weekly to determine appropriate dosage levels and to monitor for any drastic changes in weight throughout the duration of the study. In the strain-related sub-analyses, an additional 4 genetically-equivalent, vehicle-treated mice from a separate but similarly-designed study were included to increase statistical power. Mice were housed in standard conditions, having access to a standard diet and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed under a protocol approved by the Columbia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Treatment

Parathyroid Hormone Fragment 1–34 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (P3796, St. Louis, MO), stored as a stock solution at 400 μg/mL, and further diluted in vehicle (1 mM acetic acid in sterile PBS) on the day of injections. PTH was administered subcutaneously at 40 μg/kg body weight, 5 consecutive days per week for 5 weeks, concurrent with mechanical loading. An equivalent volume of vehicle was given to control mice (average injection volume approximately 0.1 mL). For each mouse the daily injection was given approximately 40 minutes before the loading bout.

In Vivo Mechanical Loading

Mechanical stimulation was applied to the right limb of each mouse 5 consecutive days per week (Monday-Friday) from onset through the conclusion of the study (5 total weeks of loading), leaving the left limb as an internal, nonloaded control. The loading apparatus consisted of a custom 3D-printed angled plate to stabilize the foot and an actuator featuring a hemispherical cavity to house the knee joint. These parts were affixed to a standard load frame with a linear actuator and control system (Bose Electroforce/TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). For the duration of loading, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane at a concentration of 1.5% Vol/Vol in oxygen delivered at 1.5 L/min. The loading profile consisted of a haversine waveform between compressive loads of 1 and 9 Newtons, carried out for 100 cycles at 2 Hz. To ameliorate potential instabilities in the loading control system and to mitigate the soft tissue response, a compressive preload of 1 N was held on the limb for at least 4 minutes prior to the initiation of the load-controlled cycles. At the conclusion of each loading procedure, mice were allowed to recover from the anesthesia on a heating pad in an isolated cage, where they could also be monitored for any gross deficiencies in gait or behavior before returning to standard housing.

In Vivo μCT Imaging

Since modeling and remodeling are defined by the coupling to preceding or succeeding formation/resorption events, making this distinction at the onset of treatment requires imaging to commence before treatment. To this end, weekly in vivo μCT scans using the Scanco VivaCT 80 system (Scanco, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) were initiated one week before the first week of loading and injections. All scans were performed on Mondays to reflect changes from the prior week of treatment/loading. The first two scans served as baseline data, and thus occurred before the onset of treatment/loading. The first week of treatment/loading commenced on the same Monday as the second baseline scan. Thus, the third scan is reflective of changes immediately following the first week of treatment/loading, and thus for clarity is hereafter referenced as “Week 1” or changes between Week 0 and Week 1. In brief, scanning parameters were 55 kVp, 145 μA, and 300 ms integration time. To maximize precision, scans were reconstructed at 5μm isotropic voxel size.

Since both limbs of the same mouse need to be scanned for pairwise comparisons of the effect of loading, only one scan is performed per limb: a 3.84 mm long region of interest from which trabecular and cortical sub regions are subsequently extracted. The full length of this scan corresponded to one full cone beam “stack” as determined by the machine settings.

Mice were kept unconscious throughout scanning using isoflurane anesthesia delivered through a nose cone inside the scanner at a concentration of 1.5% Vol/Vol in oxygen delivered at 1.5 L/min, identical to the process used during loading. Tape and gauze were used to secure the mouse limbs in place during scanning in an effort to mitigate any motion artifacts. Upon completion, mice were allowed to recover prior to returning to standard housing following the same procedures as in the in vivo mechanical loading.

Region of Interest Extraction

From the first weekly scan, a trabecular region of interest starting at the metaphyseal growth plate and extending 1.5 mm distally is extracted. Similarly, a cortical region of interest starting 2 mm distal from the growth plate and extending a further 1.25 mm is extracted (Figure 1). For all scans after the first, these regions of interest at first included an additional .15 mm on both the proximal and distal ends to ensure a sufficient range for image registration by accounting for differences in the manual setup of the scan, as well as longitudinal displacements of trabecular bone occurring as a result of the continually-active murine metaphyseal growth plate. Woven bone formation was manually checked for in each scan, and was not observed.

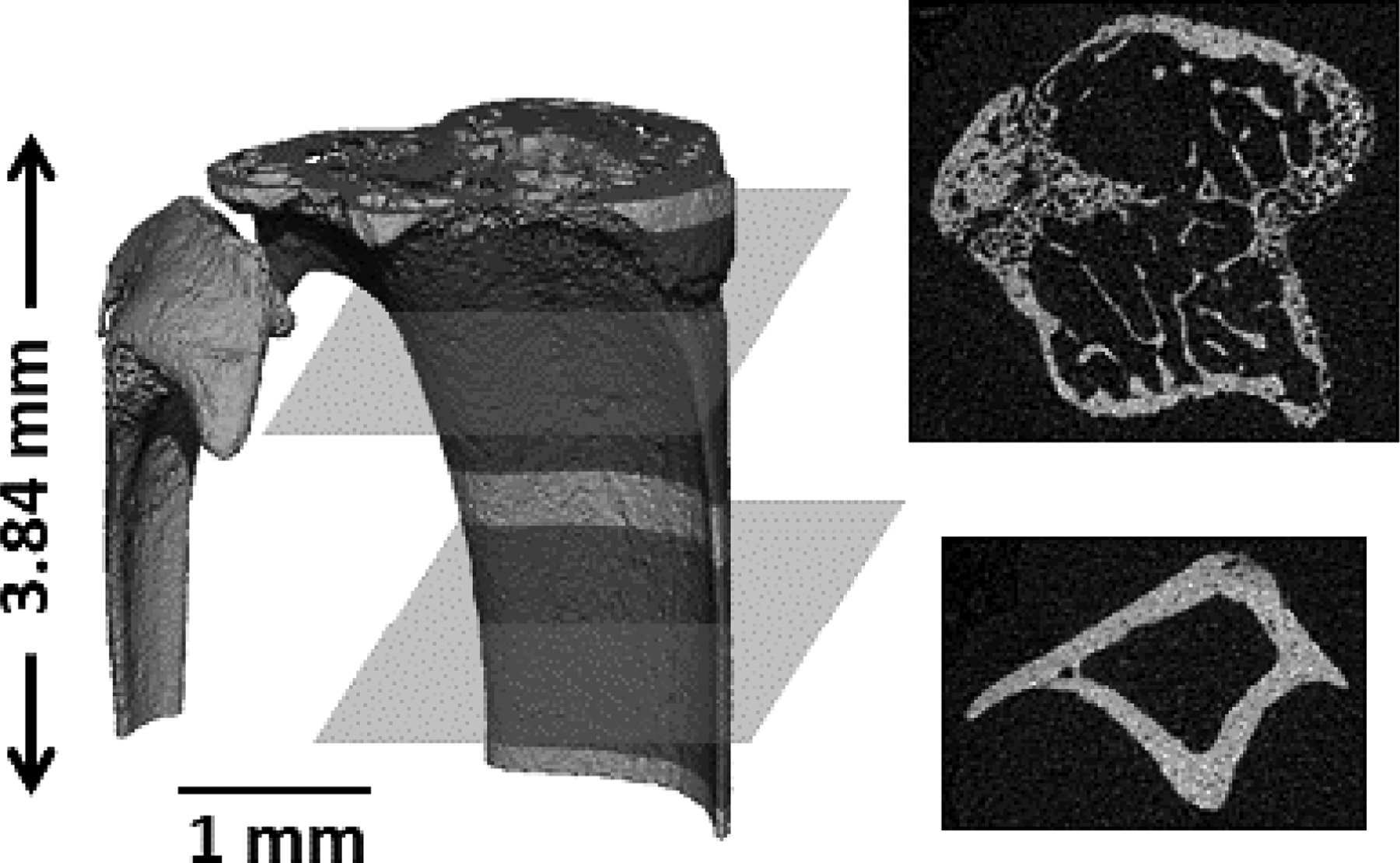

Figure 1. Regions of Interest Extraction.

To limit in vivo micro-computed tomography scans to two per mouse per week (one on each leg), a single scan was performed from which trabecular and cortical subregions were extracted. From the desired scanning parameters, a maximum 3.84 mm region was acquired, from which a 1.5 mm trabecular region (starting from the metaphyseal growth plate extending distally), and a 1.25 mm cortical region (starting 2 mm from the metaphyseal growth plate and extending distally) were manually extracted.

Image Registration

All image registration and associated rotations were performed on full-resolution 16-bit grayscale images. Weekly isolated regions of interest were registered to a common coordinate system using algorithms available in the Scanco Image Processing Language (IPL) library. Following a centers of mass alignment, a gradient descent strategy is employed to optimally align adjacent weekly images based on maximizing a normalized correlation coefficient. Multiple registration steps of increasing image resolution are utilized to help avoid local maxima. For trabecular bone, the whole metaphyseal segment is first registered, and then a trabecular-only sub region is registered to account for longitudinal shifts relative to the cortical shell, a technique that has previously shown to ameliorate the effects of the persistently-active growth plate shifting trabecular structures distally32. Other than this, the registration processes for trabecular and cortical bone were the same. To minimize bias resulting from image rotation such as partial volume effects, the first and second weekly scans are both rotated to their midpoint in 3D space32. Subsequent scans are also rotated into this 3D spatial location, thereby ensuring all scans are rotated once into the same global coordinate system.

In Vivo Modeling/Remodeling Analysis

Registered grayscale images were segmented using a global threshold of 40% of the maximum grayscale value. Voxels classified as bone in one week, but as background the previous week, were classified as bone formed. Similarly, voxels classified as bone in one week and as background the next week were classified as bone resorbed. Registered grayscale images from consecutive weeks were subtracted from one another, and in an effort to capture newly-mineralizing bone at its earliest indication, voxels were also considered to be formed (or correspondingly resorbed) bone if the difference in grayscale intensity of a voxel between two weeks was greater than 75% of the global threshold value. This concept was implemented in a previous study33, and has a biological basis in that it is known that during bone formation, unmineralized osteoid is first laid down by osteoblasts and becomes more slowly mineralized over time thereafter. Thresholding, in conjunction with scanning the third day following loading, were used to mitigate lag in the relevant biological processes. Nonphysiological sequences likely resulting from noise (i.e., resorption or formation of the same voxel consecutive weeks) were filtered with masking algorithms.

Prior to segmentation and subtraction, grayscale images were subjected to a Gaussian filter (sigma = 0.8, support = 1). Furthermore, instances of formation or resorption clusters with a total volume of less than 10 voxels were considered likely noise and removed33. Masking algorithms were employed to ensure no voxels could be considered to have undergone formation or resorption in consecutive weeks. For subsequent data processing, images were stored in the form of weekly transitions (i.e., the week 1 to week 2 image). These 3D images consisted of voxels labeled with one of four values indicating whether bone was formed, resorbed, remained unchanged as quiescent bone, or remained unchanged as non-bone/background (Figures S1, S2). The separation of the latter two is necessary to distinguish voxel history in space where bone could potentially be formed in later weeks. These transition images were exported from the Scanco system, processed through a custom C-based program to decompose the 3D image into a text file, and then imported into MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for subsequent processing.

From interweek transition images, formation and resorption sequences were tracked on a voxel basis to identify instances of modeling and remodeling. If the three-week progression of a voxel was identified as background-background-formation, it was classified as anabolic modeling (i.e. uncoupled formation) (Figure 2). If the three-week progression of a voxel was identified as resorption-background-background, it was classified as catabolic modeling (i.e. uncoupled resorption). If the three-week progression of a voxel was identified as resorption-background-formation, it was classified as bone remodeling. All three indices were tracked and summed separately over trabecular and cortical regions of interest for each of the four weeks they could be computed, and reported as either raw or relative volumes (volume on loaded side minus volume on nonloaded side).

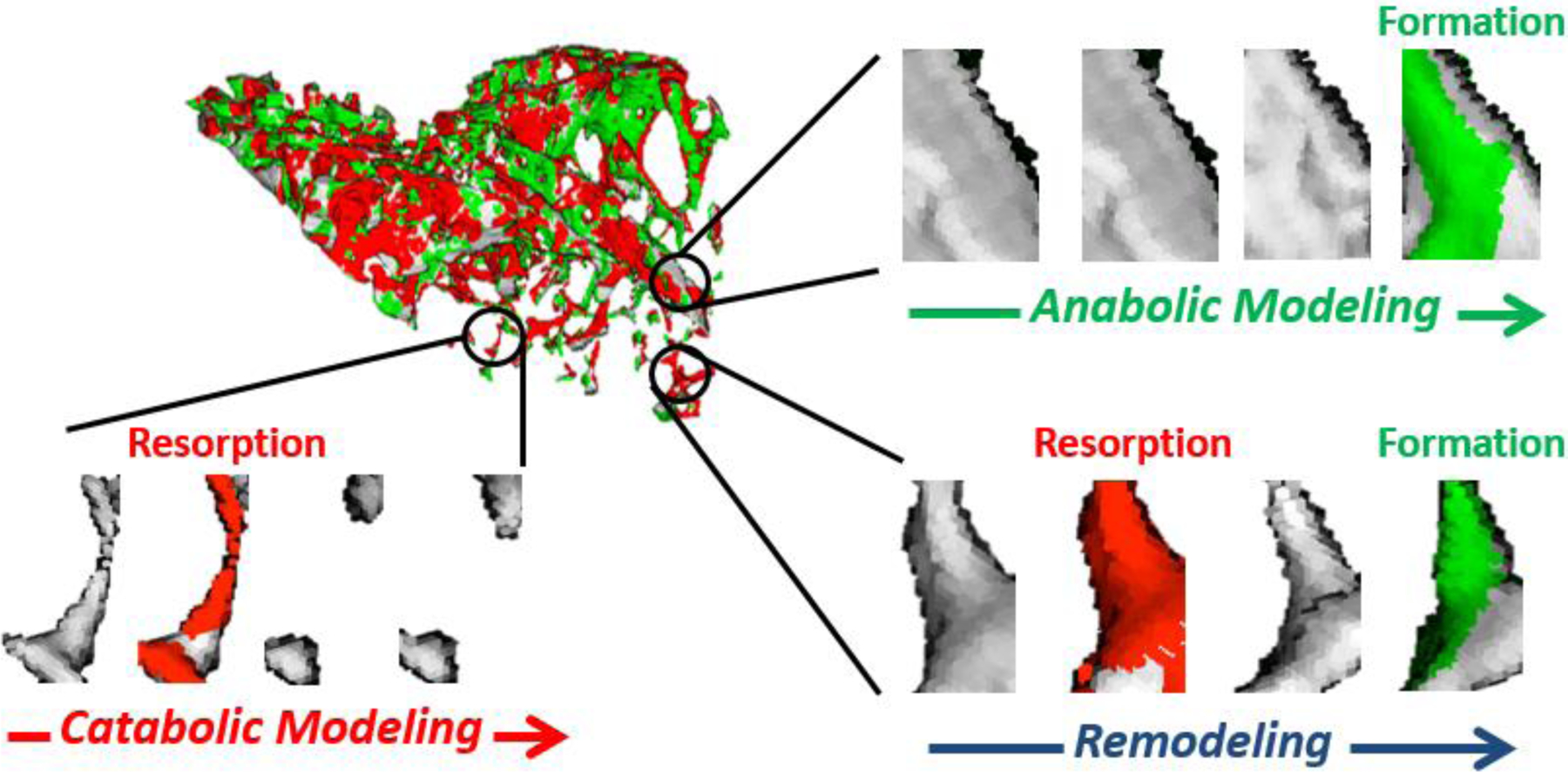

Figure 2. In Vivo Quantification of Bone Modeling and Remodeling.

Modeling and remodeling sequences were identified on a voxel basis from sequential weekly scans. Anabolic modeling was defined by voxels formed (in green) in previously quiescent space, catabolic modeling was defined by voxels resorbed (in red) that were not followed by formation, and remodeling was defined by voxels that were resorbed and then replaced.

Morphological and Strain-Based Categorization

To further examine and delineate the modeling and remodeling responses in bone microarchitecture, weekly segmented trabecular images were processed through the Individual Trabecula Segmentation (ITS) software previously developed in our laboratory34. Briefly, local topological characteristics are considered and each individual trabecula is classified as either plate-like or rod-like in structure. Bone volumes were thus further classified as being formed on or resorbed from plate-like or rod-like trabeculae. Cortical scans were manually cut using Scanco software to isolate and quantify periosteal (outer) and endosteal (marrow facing) surface responses independently.

To more closely examine the mechanoresponse specifically, trabecular and cortical regions were further stratified in the vehicle-treated mice. Plates and rods were classified as axially (0°–30°), obliquely (30°–60°), or transversely (60°–90°) aligned with respect to the longitudinal axis of loading (Figure S3). Finite element modeling of the whole metaphyseal region of interest (trabecular region plus surrounding metaphyseal cortex) from all loaded bones prior to the onset of the first loading bout was performed in Abaqus (2019, Dassault Systemes, Waltham, MA). A standard voxel-to-element conversion was used after downscaling images from 5 μm to 10 μm to ease computational requirements. A uniaxial, distributed compressive load of 9 N was applied to the proximal layer of the model, and the distal layer was fixed. Peak principle strains were averaged over each of the two trabecular types, and each of the three orientations. For the cortical region of interest, high tension, high compression, and low strain regions of the periosteal and endosteal surfaces were manually separated based on patterns observed in whole bone finite element models from our samples at the study endpoint, which were consistent with previously published findings35–37. In brief, the anteromedial surface is in tension, the posterolateral zone is in compression, and a low strain region flanks the neutral axis that, in our region of interest, is approximately parallel to the tibial ridge.

Radiation Control Mice

An additional subset of mice was used to analyze the effects of weekly micro-CT scanning alone. Five groups of mice (n=3/group) were subjected to all the same conditions as the experimental mice, except they were only scanned at one of the 5 treatment weeks. While modeling and remodeling indices could not be computed from these single scans, they allow for comparisons of the trends of basic trabecular morphological parameters that would indicate any gross effects of the radiation or stress from scanning and mechanical loading. For purposes of mimicking experimental conditions as closely as possible, these radiation control mice did have one limb loaded, but only the nonloaded limbs of these mice were compared to nonloaded limbs of the experimental (weekly-scanned) mice.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise noted. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (Version 23, Armonk, NY) using a repeated measures or mixed model ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni adjustments made for post hoc tests between limb groups. Loading is treated as a within-subject factor, since limbs from the same mouse are inherently related, PTH or vehicle injection is treated as a between-subject factor, and week after the onset of loading is included as a covariate. A difference in degree of mechanosensitivity (synergistic or tempering effect) resulting from PTH treatment is represented by a significant two-way interaction between loading and PTH, while the presence of mechanosensation alone is identified via the post hoc tests between loaded/nonloaded limbs of the respective treatments groups. Statistical significance is noted at p < 0.05.

Results

Loading and PTH both work against a natural decrease of trabecular bone volume fraction, and the effects of weekly scanning is negligible

Female C57Bl/6 mice at 16 weeks (as used in this study) are already in the process of a marked decline in trabecular bone volume fraction that persists over the 5-week experimental period regardless of weekly scanning. This has been reported previously38, and herein it is shown that experimental mice in this study started with similar baseline trabecular properties, and loading and/or PTH can slow this predominating phenomenon (Figure 3). The natural bone loss occurs primarily as a result of decreases in trabecular number, as trabecular thickness is shown to remain relatively constant in vehicle-treated, nonloaded limbs of both the experimental and single-scan radiation control mice (Figure S4).

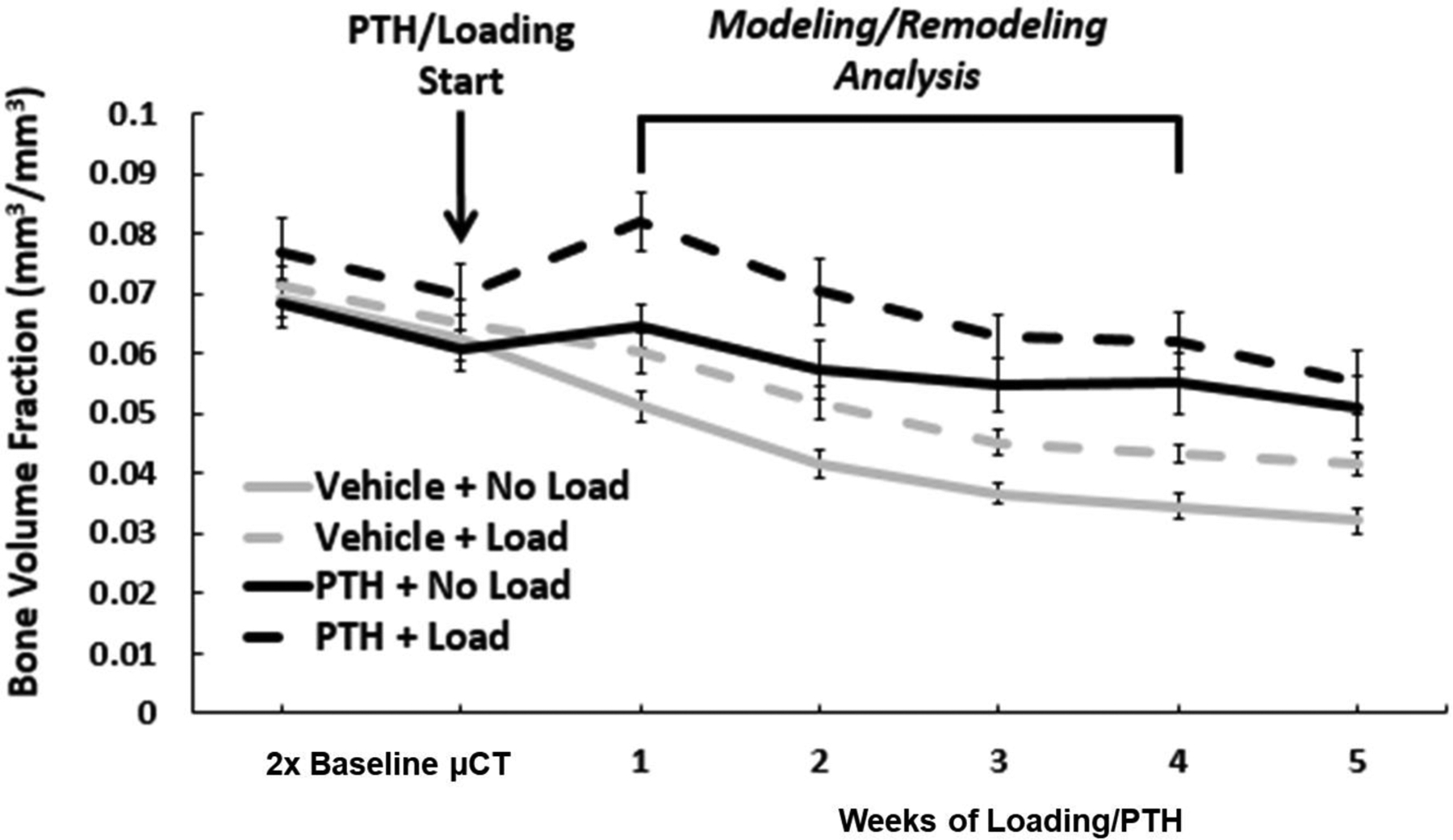

Figure 3. Experimental Timeline and Gross Changes in Trabecular Bone Volume Fraction.

Bone volume fraction (BV/TV) was tracked over time in loaded and nonloaded limbs of mice treated with vehicle or PTH to broadly characterize the response and illustrate the timeline of modeling/remodeling analysis. To capture modeling/remodeling events in response to loading/PTH at onset, it is necessary to start scanning before treatment and to extend scanning beyond the timeframe of these measurements, as they inherently rely on data at preceding and/or succeeding time points. Weekly scans were performed on the third day following the last loading bout of the relevant week. Treatment and loading were continued through the end of the experimental timeline. Error bars indicate SEM (n=6/group).

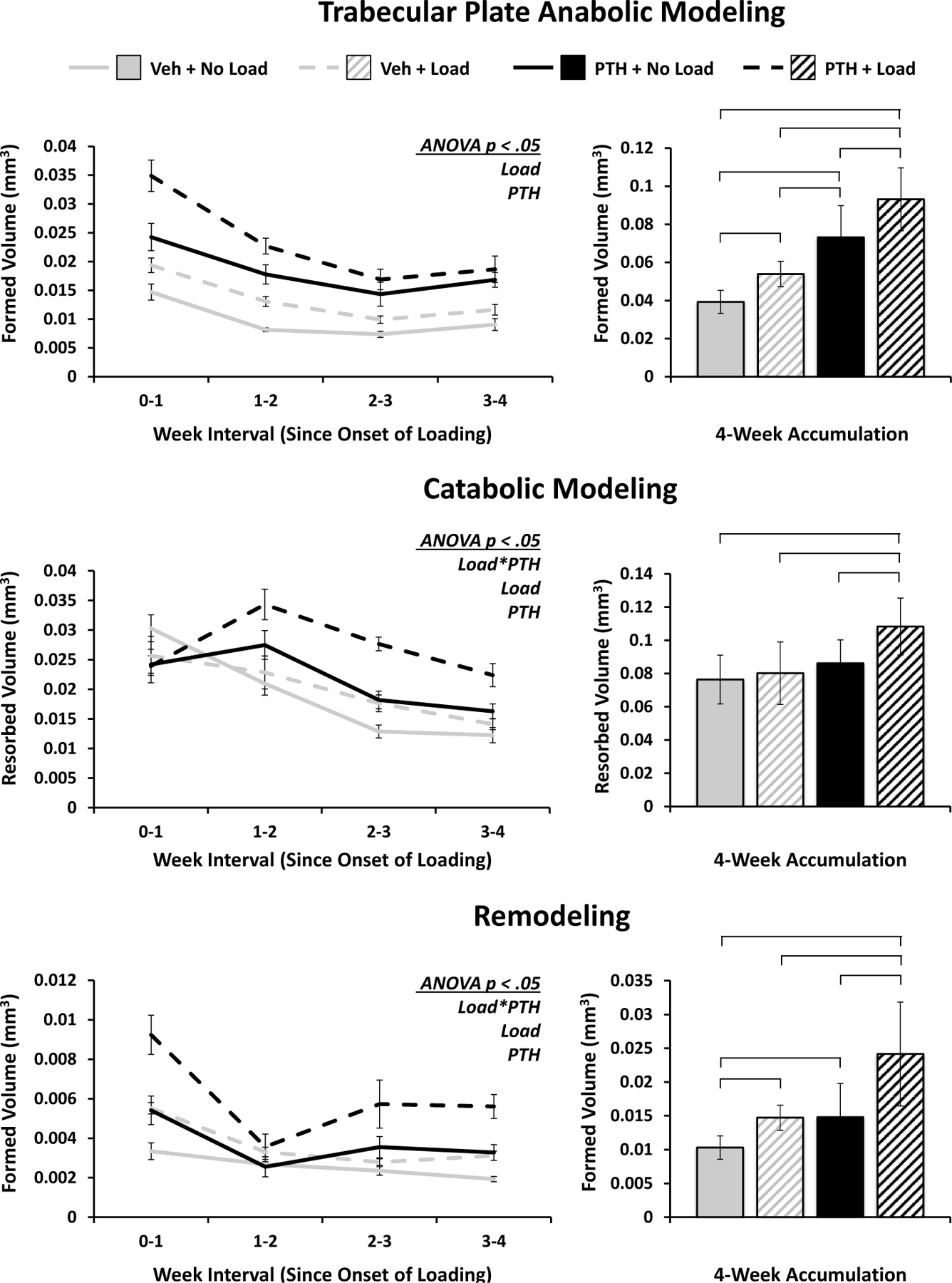

Loading and PTH produce additive effects on trabecular bone accumulation through anabolic modeling and a synergistic effect though remodeling and catabolic modeling

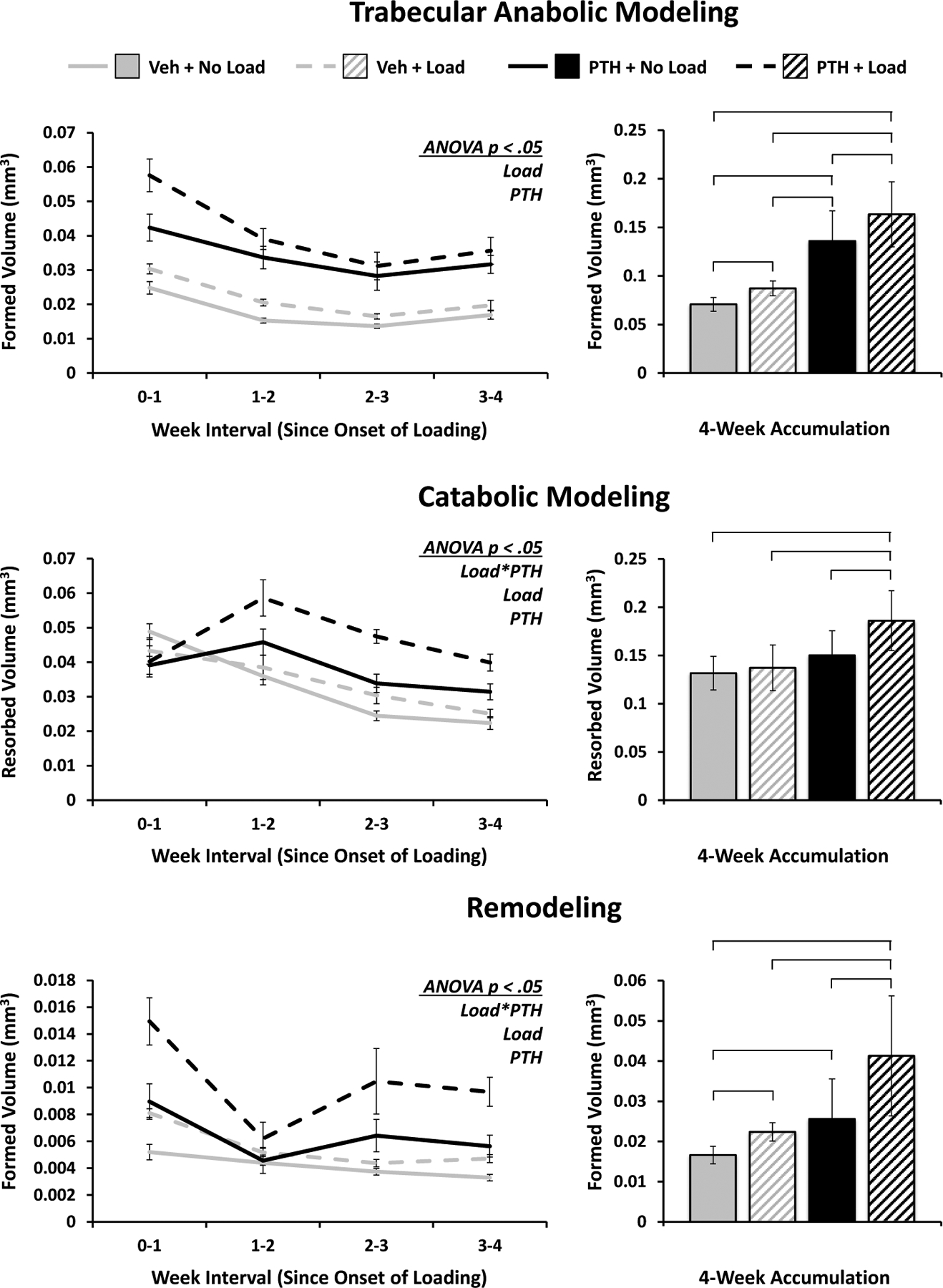

Mechanical loading and PTH both resulted in significant increases in bone formed through anabolic modeling, as significant differences existed between all limb groups, but there was no significant interaction (Figure 4). Bone remodeling was significantly increased as a result of loading and PTH acting synergistically to heighten the effect of loading in PTH-treated mice. Likewise, they produced a significant interaction on catabolic modeling, however the group differences were much less pronounced overall, with only the PTH-treated and loaded limbs exhibiting significantly more catabolic modeling than the other groups. Altogether, the volume of bone formed via remodeling was generally around a quarter to a third the amount of bone formed via anabolic modeling, with both being lesser in magnitude than the catabolic modeling volumes, a reasonable discrepancy given the observed trend in total trabecular volume.

Figure 4. Trabecular Bone Modeling and Remodeling in Response to PTH and Mechanical Loading.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling in the trabecular region of interest are quantified over time and as a 4-week accumulation. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations.

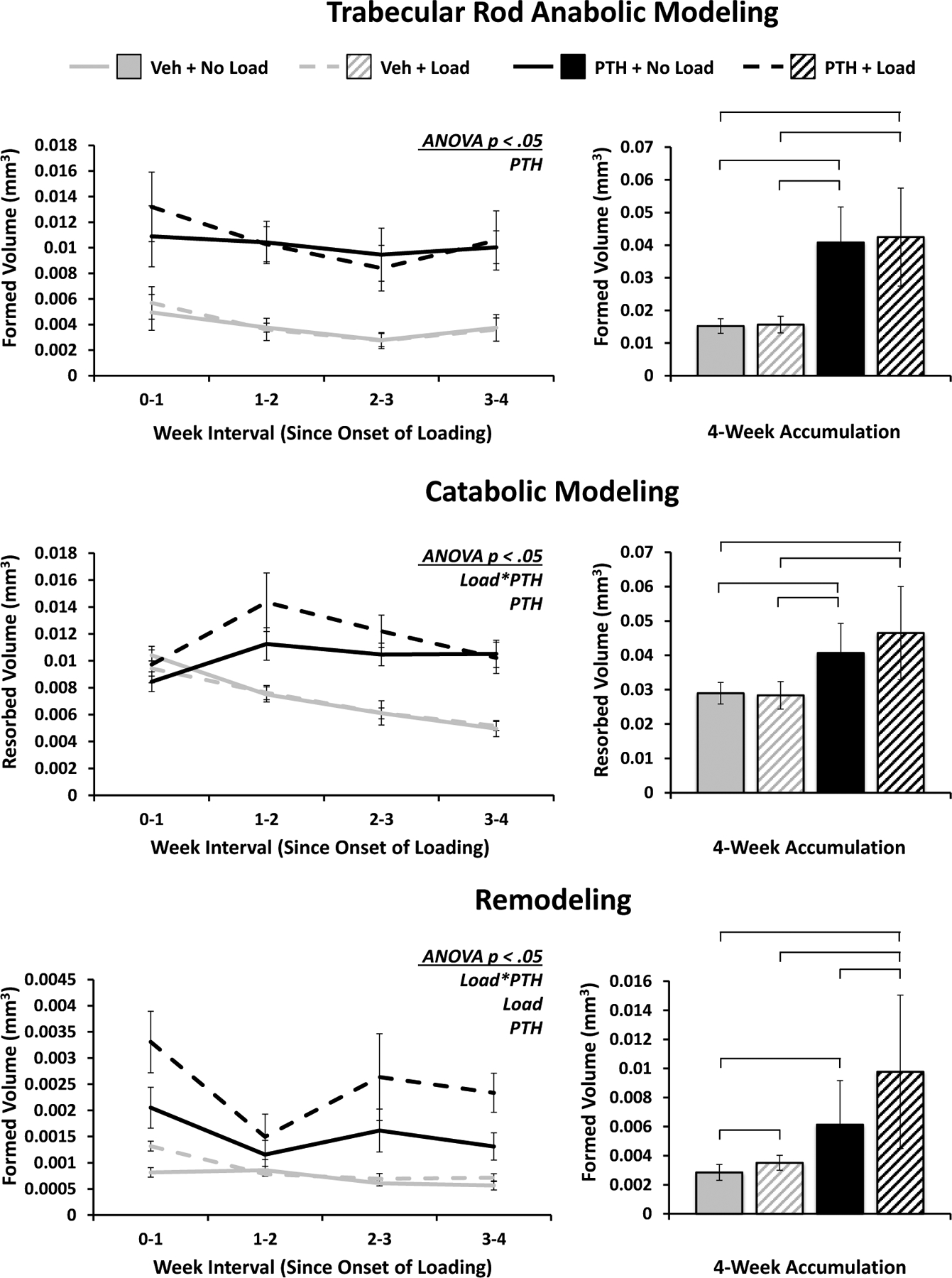

The effects of mechanical loading on trabecular bone are typically manifested in plate-like trabeculae, whereas the effects of PTH are less preferential

In classifying the modeling and remodeling events based on whether bone is being formed on or resorbed from trabecular plate-like or rod-like elements, the trabecular plate data very closely mirrors the results from the whole trabecular structure. Mechanical loading and PTH both tend to increase metabolic activity, with additive effects on anabolic modeling and a significant interaction in catabolic modeling and remodeling volumes (Figure 5). In contrast, the response on rod-like elements were dominated by PTH, which led to significant increases in both types of modeling and remodeling. However, the effect of loading and the significant positive synergistic interaction with PTH treatment were maintained in the volumes of bone formed via remodeling on rod-like elements (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Modeling and Remodeling of Plate-like Trabeculae.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling strictly on plate-like trabeculae. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations.

Figure 6. Modeling and Remodeling of Rod-like Trabeculae.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling strictly on rod-like trabeculae. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations.

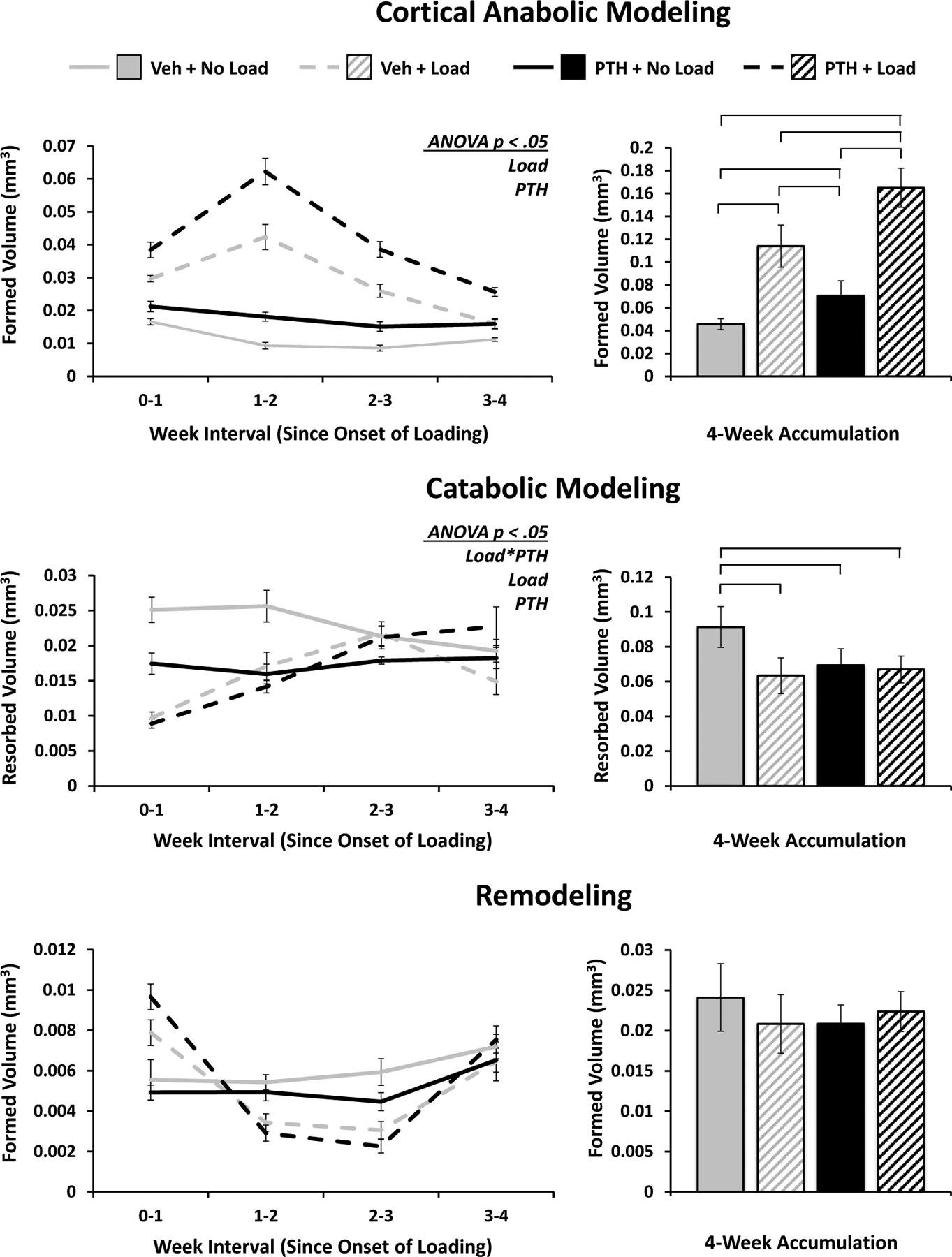

Mechanical loading and PTH lead to greater cortical bone volume through differences in anabolic and catabolic modeling

Loading and PTH both resulted in significantly increased anabolic modeling, with the effect of loading being particularly pronounced, exhibiting a robust peak after the second week of loading, and attenuating thereafter (Figure 7). Over four weeks, all groups showed statistically significant differences from one another, with more striking contrasts than were observed in trabecular bone. There were similarly stark contrasts in catabolic modeling: uncoupled resorption was significantly inhibited by both stimuli, with a significant, attenuating interaction owing to a partial suppression of resorption by PTH, paired with relatively similar levels of suppression observed as a result of loading in both PTH- and vehicle-treated mice. The cumulative effects of remodeling were not significant, although the time course displayed a trend roughly the inverse of anabolic modeling, suggesting a potential tradeoff between the two types of bone formation.

Figure 7. Cortical Bone Modeling and Remodeling in Response to PTH and Mechanical Loading.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling in the cortical region of interest are quantified over time and as a 4-week accumulation. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations.

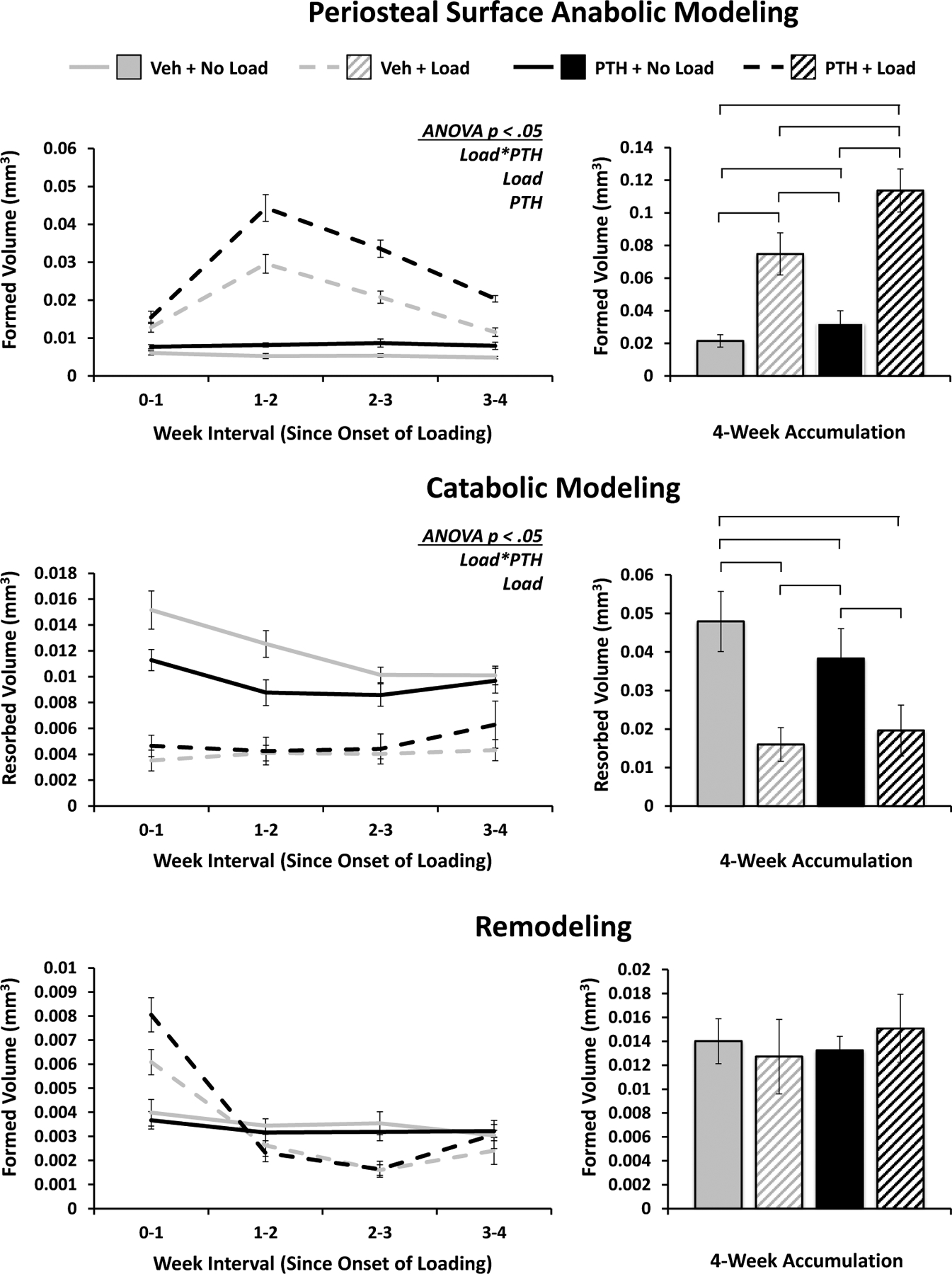

Periosteal and endosteal surfaces of cortical bone exhibit markedly different responses, particularly to loading

In many aspects, the bulk cortical response to loading and PTH is reflected on the periosteal surface. There is a significant anabolic modeling response to both loading and PTH, however there is also a significant interaction indicative of a synergistic effect. Over 4 weeks, all groups show significant differences, with the effect of loading being more pronounced (Figure 8). Like the bulk catabolic response, periosteal catabolic modeling is significantly inhibited by loading and PTH, with a similar interaction showing diminished returns due to a predominantly loading-induced suppression. Remodeled volumes accumulated over the 4 weeks do not display significant differences between groups, though the time course again suggests a potential interchange of the bone formation regime from remodeling to modeling in response to load.

Figure 8. Periosteal Surface Modeling and Remodeling.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling strictly on the periosteal surface of cortical bone. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations.

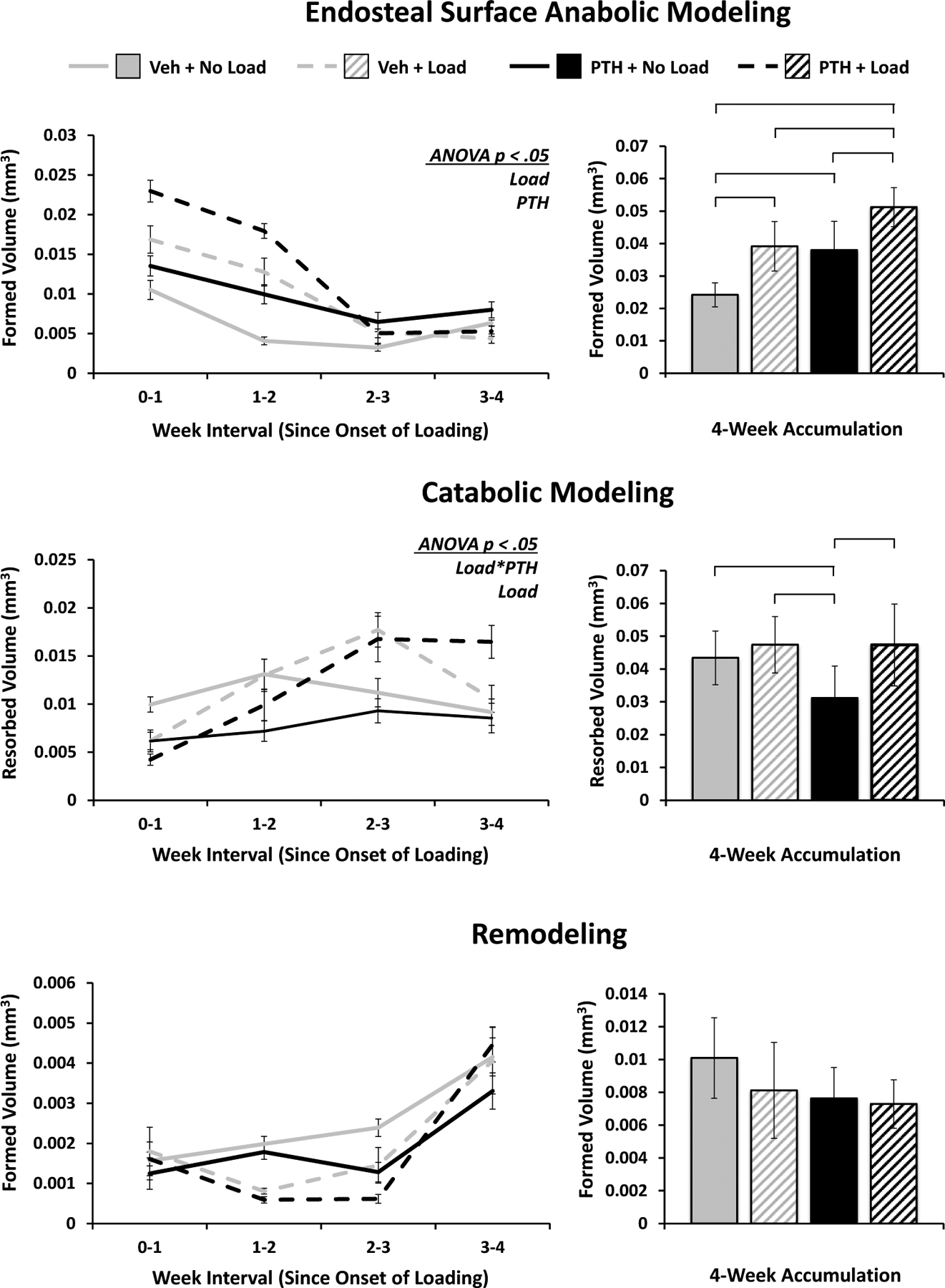

On the endosteal surface the significant effects of loading and PTH are still present for anabolic modeling, but the differences are less pronounced and their synergistic effect is not observed. Additionally, the peak in response occurs after the first week, and the attenuation phase begins immediately thereafter (Figure 9). The effect of loading over time on catabolic modeling is more complex, being initially suppressed, but by the third week enhanced in loaded limbs compared to nonloaded limbs. The baseline suppression of catabolic modeling with PTH magnifies the effect of loading in the PTH group, driving a significant difference and interaction effect, as loading with and without PTH induces a nearly consistent amount of catabolic modeling. Similar to the bulk cortical and periosteal responses, remodeling showed no significant differences resulting from loading or PTH on the endosteal surface.

Figure 9. Endosteal Surface Modeling and Remodeling.

Volumes of bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling, and resorbed via catabolic modeling strictly on the endosteal surface of cortical bone. Weekly progression error bars indicate SEM; accumulation bar graphs are shown with standard deviations (n = 6/group).

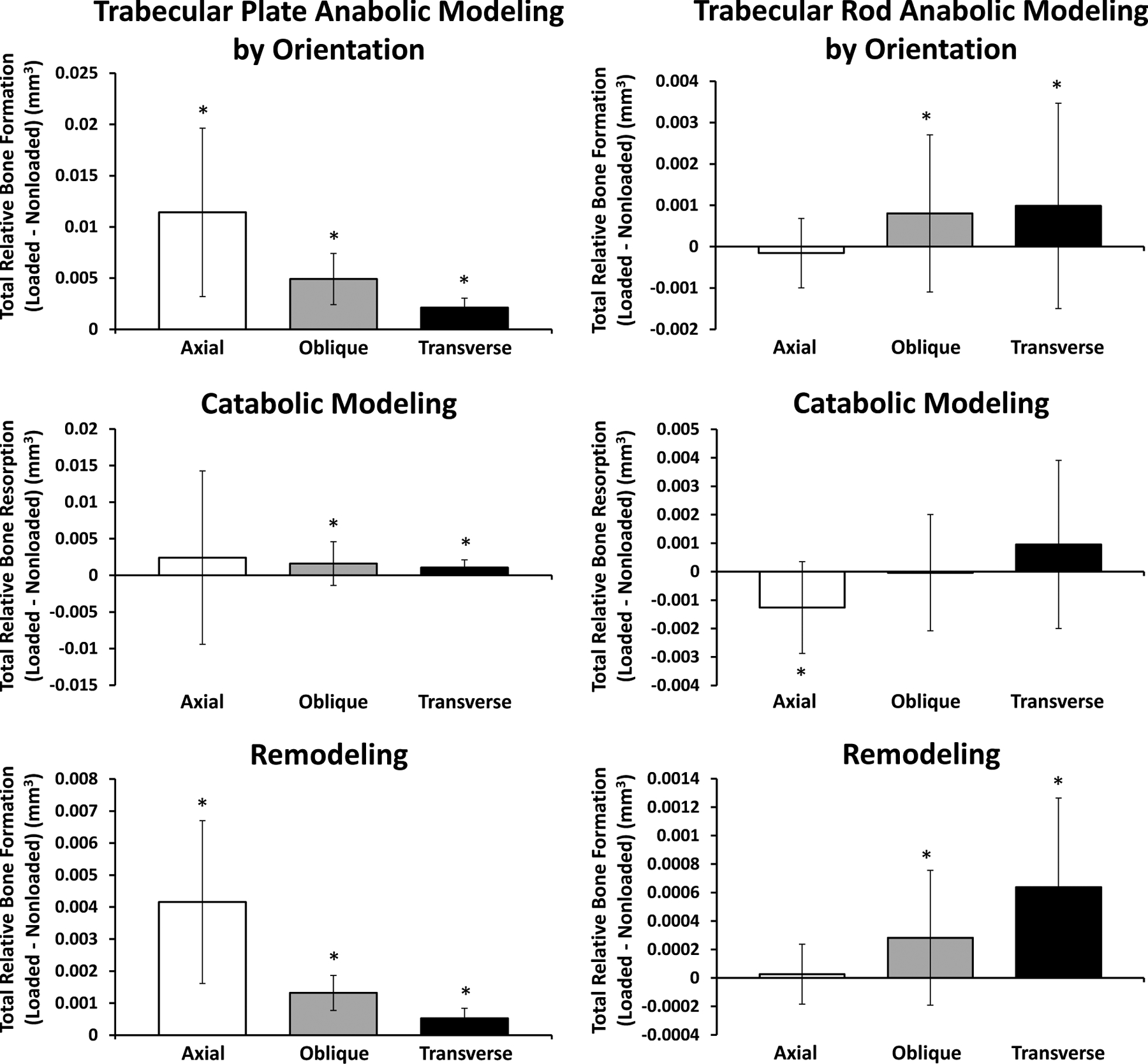

Loading affects modeling/remodeling on plates and rods in all orientations, with greatest volumetric differences on axially aligned plates and transversely aligned rods

Trabeculae aligned at different orientations with respect to the longitudinal axis are subject to different strain magnitudes predicted by finite element modeling of proximal tibia segments. Under a distributed compressive load, average peak principal compressive strains are greater in axial plates and rods than their obliquely- and transversely-oriented counterparts. Average peak principle tensile strains in plates are also significantly greater in the more axially aligned elements; however, in contrast the average peak principle tensile strain in rods was greatest on transversely aligned elements (Figure S5).

Mechanical loading led to significantly more relative bone formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling on trabeculae in all orientations, while catabolic modeling is slightly, but significantly enhanced only on oblique and transverse plates (Figure 10). For rods, anabolic modeling and remodeling volumes are increased on obliquely- and transversely-oriented elements, while catabolic modeling is suppressed on axially-aligned elements.

Figure 10. Cumulative Trabecular Plate and Rod Modeling and Remodeling Volumes Separated by Orientation in Response to Loading.

Trabecular plate (left column) and rod (right column) volumes formed via anabolic modeling and remodeling and resorbed via catabolic modeling in response to loading were calculated for trabeculae in each orientation independently. Plots indicate relative amounts of formation or resorption (loaded – nonloaded). All mice included in these results were treated with vehicle injections.

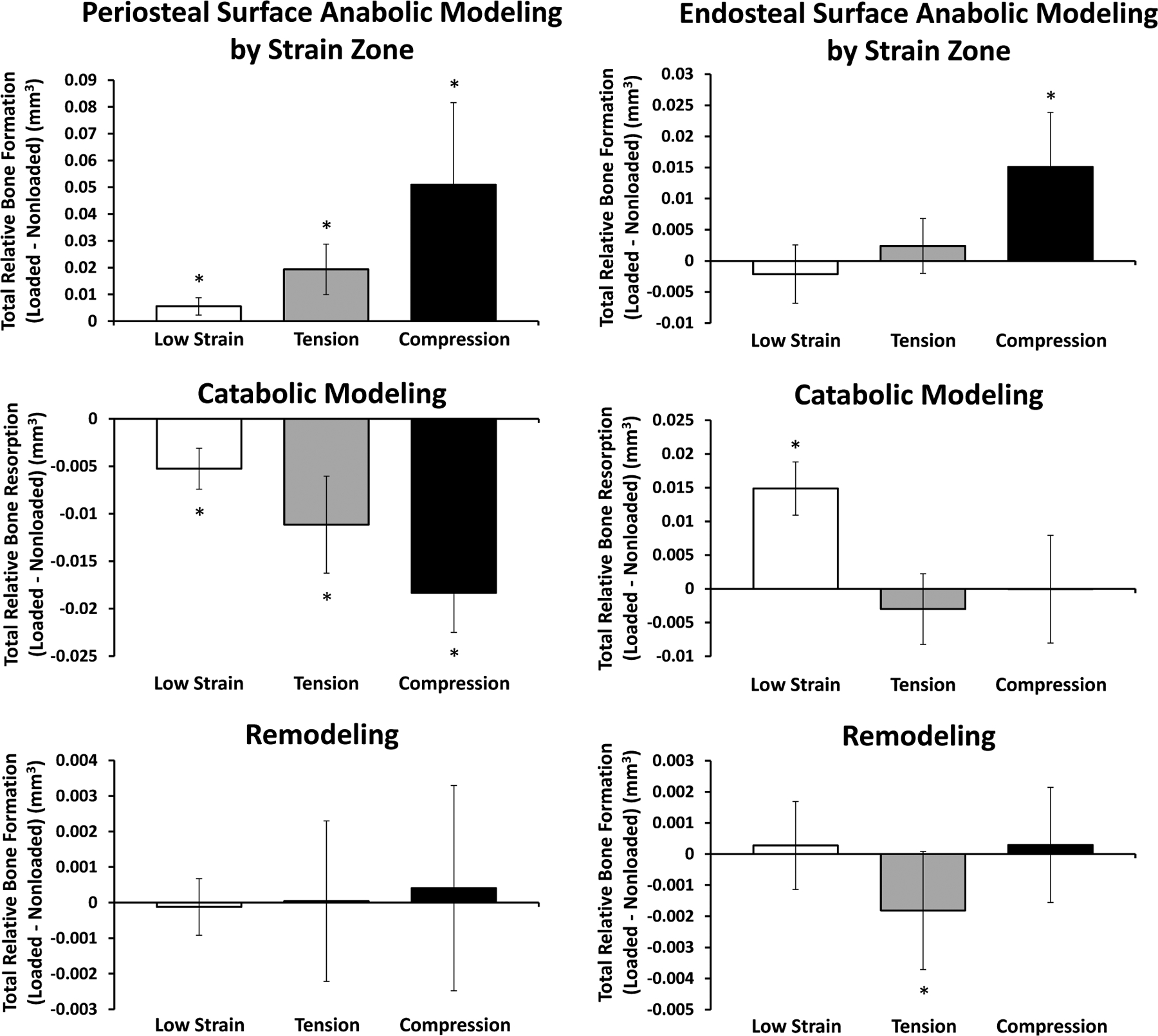

Periosteal and endosteal modeling/remodeling dynamics in response to loading depend on local strain environments

It has been shown previously2,16,20–22,35–37 and confirmed here using whole bone finite element modeling that axial loading of the uniquely curved murine tibia results in distinctive axial strain zones across transverse sections. Broadly, the anteromedial zone is subjected to tensile strains peaking around 2000 με, whereas the posterolateral zone is under compressive strains peaking around 3500 με. Between the two resides the neutral axis and a continuum of relatively low-magnitude strains (Figure S6).

The periosteal surface showed significant anabolic and catabolic modeling responses in all strain zones, which correlated positively with strain magnitude (Figure 11). Loading increased bone volume formed via anabolic modeling, while inhibiting bone volume resorbed via catabolic modeling. Remodeling is not significantly affected in any region. On the endosteal surface, the only region experiencing a significant increase in anabolic modeling with loading is that under compression, and remodeling is suppressed in the region of tension. Interestingly, the loading-induced differences in endosteal catabolic modeling are entirely concentrated to the low strain region.

Figure 11. Cumulative Periosteal and Endosteal Modeling and Remodeling Volumes Separated by Strain Zone in Response to Loading.

Periosteal (left column) and endosteal (right column) volumes formed via anabolic modeling and remodeled and resorbed via catabolic modeling in response to loading were calculated for each cortical strain zone independently. Plots indicate relative amounts of formation or resorption (loaded – nonloaded). All mice included in these results were treated with vehicle injections.

Discussion

In the present study, two well-established stimulants to improve bone mass (mechanical loading and intermittent parathyroid hormone) are tracked in a novel method to better quantify, localize, and distinguish changes in bone volume as modeling or remodeling using longitudinal in vivo micro-computed tomography. Techniques similar to this approach have gained momentum in recent years39–42 as the distinction between the biological mechanisms governing modeling- and remodeling-based bone formation have gained clarity26,28,43, and with that an opportunity to optimize osteoporosis therapies44. PTH has a well-established clinical benefit but a nuanced mechanism of action, highlighted by the dichotomy of continuous administration leading to bone loss, but intermittent dosage leading to bone gain29,45,46. Though it has been shown that PTH can redirect quiescent bone lining cells into bone forming osteoblasts15 and may produce short term increases in anabolic bone modeling, its most established function relates to bone remodeling through serum calcium regulation (resorbed bone being a primary source)10,29. This has driven belief towards a favorable remodeling ratio being the primary means of bone accrual with PTH, while in contrast, Wolff’s Law and the adaptation of bone to mechanical loading depends on a modeling response, inherently relying on shape changes to reflect mechanical demands.

In broad terms, our trabecular data are in agreement with prior studies16,47,48, and may serve to help reconcile some prior discrepancies. Sugiyama et al. specifically noted that they did not observe a synergistic effect between PTH and mechanical loading in trabecular bone16 as was previously observed by Chow et al. and Kim et al47,48. Our findings indicate that trabecular bone formed via anabolic modeling does not behave synergistically, but bone formed via remodeling does, though at a smaller overall volume. It therefore may stand to reason that for traditional, bulk measures of bone morphology, particularly if the remodeling rate is inherently lower (such as it may be for mice in the Sugiyama study compared to rats in the other studies), the synergistic effect may be obscured. Even within species, site-specific differences in the modeling/remodeling rates could similarly confound the effects. In fact there is some support for this supposition, in that it has been shown the effects of combined alendronate (an antiresorptive bisphosphonate) and PTH behave synergistically in the lumbar vertebra, but only additively in the femur of C57Bl/6J mice49, and Yamane et al. specifically propose a dependence on the effectiveness of PTH and antiresorptives on the remodeling status50. Furthermore, we have shown that PTH tends to result in nondiscriminatory bone accrual, whereas mechanical loading produces greater volumetric increases on plate-like trabeculae, suggesting that the bulk effects of these stimuli may depend on preexisting microarchitectural differences between species or between different anatomical sites of the same species. The relative proportions of trabeculae at each orientation may also play a role in this regard, as they are important to whole bone stiffness and failure properties (correlations to that effect have been observed previously51,52), and we demonstrate significantly different strains corresponding to different orientations. Relatedly, it should be noted that while our study shows bone is principally accumulated in larger volumes on axial plates and transverse rods, this is undoubtedly in part because those types of trabeculae are more prevalent at the outset, as differences between volumes formed in the different orientations do not persist when controlling for initial bone volume in those orientations.

Similar to the trabecular findings, many of the bulk cortical results are in agreement with prior literature, however, our novel methods again bring forward some interesting and unique insights. Importantly, we observe a synergistic effect of loading and PTH in the anabolic bone modeling regime on the periosteal surface, and this was the one region of interest also observed to have a significant interaction in bone volume accrued in the study by Sugiyama et al16. Interestingly, however, we did not observe this phenomenon on the endosteal surface where PTH elevated the anabolic response, and loading increased it in vehicle- and PTH-treated mice to a similar magnitude. It should be noted that based on the structure of the tibia, the axial strains induced from bending will always be greater on the periosteal surface, as they will always be farther from the neutral axis. It would be interesting, therefore, to observe if the synergistic effect on the periosteal surface persisted at lower magnitudes of whole bone axial compression (bringing the strain closer to what was observed on the endosteal surface in our loading regimen). It is also worth noting the compressive strain magnitudes tended to be higher in cortical bone compared to trabecular bone (Figures S5, S6). This may account for some of the more prominent differences between the experimental groups, and decreasing the imposed loading on a subset of mice wherein peak cortical strains are more closely matched with peak trabecular strains would provide a unique and interesting set of strain-matched data between the two types of bone.

The cortical catabolic modeling response provided another particularly unique and novel contrast between cortical surfaces. While both PTH and loading tended to suppress periosteal catabolic modeling (which is already naturally very low), loading tended to increase the amount of catabolic modeling on the endosteal surface regardless of treatment, though this only reached statistical significance in the PTH-treated group. Load-induced bone resorption is somewhat counterintuitive in the classical bone mechanobiology sense, and to our knowledge has not previously been reported. Furthermore, we found this load-induced uncoupled resorption occurs predominantly in the region experiencing the lowest strain magnitudes (surrounding the neutral axis). While areas of high strain have been associated with more bone formation and measurable decreases in local osteocyte sclerostin expression37,53. To our knowledge, no one has identified a mechanism by which resorption would be not only favored, but the expected subsequent remodeling-based formation inhibited. It should also be noted that the catabolic modeling peaks between the second and third weeks of loading. Many in vivo loading studies are carried out for two weeks, and as our results verify, this is sufficient to observe the expected net anabolic effect. Thus, our specific combination of an extended treatment period and time lapse computed-tomography methods to quantify and localize resorption, which is not achieved through traditional histological methods, allowed us to observe this unique and unexplored phenomenon. While this remains to be fully expounded upon, it may stand to reason that the sequential peaks in first anabolic, then catabolic modeling are reflective of a system akin to the conservation of mass as bone is laid down in an area experiencing high strains, and subsequently removed from an area experiencing lower strains.

There are several limitations in our study worth acknowledging. While 16 weeks is often cited as skeletally mature or adult for mice, peak trabecular bone mass has passed and female C57Bl/6 mice have a significant predisposition for trabecular resorption at this age38. While age is controlled across groups and thus naive dynamics will be equal, the bone microenvironment is clearly favorable to resorption, thus it is reasonable to question how an environment less favorable to resorption (and/or more favorable for formation) would react to our imposed stimuli. Unfortunately, mice maintain their peak trabecular mass for a relatively short period of time that coincides more closely with adolescence and could therefore introduce a host of other confounding factors such as growth effects. Furthermore, 16-week-old female mice are one of the most common subsets used for bone research and best allows our findings to be considered within the context of existing literature. Varying levels of mechanical loading and/or PTH dosage may also be of interest as our values are in line with methods across the literature. There is an acceptable range for both stimuli, and as Sugiyama et al. illustrated well, this may play a role in the presence or effectiveness of the interactions16. Also in the realm of interactions, it bears consideration that bone metabolic processes producing net changes in volume have an inherent level of synergism or at least self-preservation. Notably, agents that preserve bone volume (or more specifically bone surface) naturally retain a higher capacity to build bone in subsequent weeks. Future work and alternative techniques will serve to more precisely address surface-specific dynamics such as percentage of mineralizing surface and the thickness of newly-deposited mineral. Current resolution limits in μCT would likely result in considerable noise, and these metrics would be better addressed with further studies utilizing fluorochrome labels. Computationally, there is likely an underestimation of true remodeling-based bone formation. Our classification requires sequential resorption and formation at the voxel level, and as such, any bone formation that occurs just outside of an adjacent resorbed voxel will be quantified as modeling-based formation, when in fact it may have been induced by nearby remodeling-based biochemical signals. An algorithm that implements proximity thresholds has been considered, but may induce other unique shortcomings. It should be noted that while strain magnitudes were reported, they naturally varied between and even within the regions of interest (particularly for cortical bone). Strain-matched studies are classically useful in this regard, though to our knowledge strain matching between the endosteal and periosteal surfaces has rarely, if ever, been performed. As the endosteal and periosteal surfaces are inherently unique in their constitutive cells, additional subsets of cortical surface strain-matched mice could prove useful in clarifying the specific dependence and/or interaction between strain and biological microenvironments. Immunohistochemical techniques would provide unique and valuable insight to this end as well, however, as evidenced by the time courses of our results, these experimental mice are likely exhibiting markedly attenuated gene/protein signals by the time of sacrifice. A study design to incorporate additional mice sacrificed at intermediate time points would be necessary to address the more transient changes, but this would not allow for the full, localized μCT-based modeling/remodeling time course.

Nevertheless, these findings highlight unique elements of mechanotransduction heretofore unreported, and add to the growing body of literature in support of the utility of combination therapies to address issues of bone health. PTH and mechanical loading are of established clinical relevance, and our methods could be easily translated to analogous clinical imaging modalities54,55 and other approved therapeutics. Beyond that, in the preclinical realm these methods could be used to probe overlap in the efficacy of targeted pathways or emerging treatments. In both arenas, there is a naturally increasing potential and sensitivity of the analysis as resolution limits are extended.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

New μCT based technology for quantifying anabolic modeling, remodeling, and catabolic modeling

Loading/PTH act synergistically in trabecular remodeling and periosteal modeling

Loading more strongly affects (re)modeling on structures experiencing higher strain

Loading induces endosteal catabolic modeling around the neutral axis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lewiecki EM, Ortendahl JD, Vanderpuye-Orgle J, et al. Healthcare Policy Changes in Osteoporosis Can Improve Outcomes and Reduce Costs in the United States. JBMR Plus 2019;3:e10192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holguin N, Brodt MD, Sanchez ME, Silva MJ. Aging diminishes lamellar and woven bone formation induced by tibial compression in adult C57BL/6. Bone 2014;65:83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, et al. Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev 2005;26:688–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenner D, Redman C, Riggs A. Teriparatide in the management of osteoporosis. Clin Interv Aging 2007;2:499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindsay R, Cosman F, Zhou H, et al. A novel tetracycline labeling schedule for longitudinal evaluation of the short-term effects of anabolic therapy with a single iliac crest bone biopsy: early actions of teriparatide. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma YL, Zeng Q, Donley DW, et al. Teriparatide increases bone formation in modeling and remodeling osteons and enhances IGF-II immunoreactivity in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:855–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt IU, Dobnig H, Turner RT. Intermittent parathyroid hormone treatment increases osteoblast number, steady state messenger ribonucleic acid levels for osteocalcin, and bone formation in tibial metaphysis of hypophysectomized female rats. Endocrinology 1995;136:5127–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone 2007;40:1434–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellido T, Ali AA, Plotkin LI, et al. Proteasomal degradation of Runx2 shortens parathyroid hormone-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in osteoblasts. A putative explanation for why intermittent administration is needed for bone anabolism. J Biol Chem 2003;278:50259–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva BC, Costa AG, Cusano NE, Kousteni S, Bilezikian JP. Catabolic and anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on the skeleton. J Endocrinol Invest 2011;34:801–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poole KE, Reeve J. Parathyroid hormone - a bone anabolic and catabolic agent. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2005;5:612–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tam CS, Heersche JN, Murray TM, Parsons JA. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the bone apposition rate independently of its resorptive action: differential effects of intermittent and continuous administration. Endocrinology 1982;110:506–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hock JM, Gera I. Effects of continuous and intermittent administration and inhibition of resorption on the anabolic response of bone to parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res 1992;7:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Bellido T, Roberson P, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest 1999;104:439–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SW, Pajevic PD, Selig M, et al. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration converts quiescent lining cells to active osteoblasts. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:2075–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiyama T, Saxon LK, Zaman G, et al. Mechanical loading enhances the anabolic effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone (1–34) on trabecular and cortical bone in mice. Bone 2008;43:238–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff J The Law of Bone Remodelling. (Translated by Maquet and Furlong) Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones HH, Priest JD, Hayes WC, Tichenor CC, Nagel DA. Humeral hypertrophy in response to exercise. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:204–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warden SJ, Mantila Roosa SM, Kersh ME, et al. Physical activity when young provides lifelong benefits to cortical bone size and strength in men. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:5337–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross TS, Srinivasan S, Liu CC, Clemens TL, Bain SD. Noninvasive loading of the murine tibia: an in vivo model for the study of mechanotransduction. J Bone Miner Res 2002;17:493–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fritton JC, Myers ER, Wright TM, van der Meulen MC. Loading induces site-specific increases in mineral content assessed by microcomputed tomography of the mouse tibia. Bone 2005;36:1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Souza RL, Matsuura M, Eckstein F, Rawlinson SC, Lanyon LE, Pitsillides AA. Non-invasive axial loading of mouse tibiae increases cortical bone formation and modifies trabecular organization: a new model to study cortical and cancellous compartments in a single loaded element. Bone 2005;37:810–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KL, Guevarra MD, Nguyen AM, Chua MC, Wang Y, Jacobs CR. The primary cilium functions as a mechanical and calcium signaling nexus. Cilia 2015;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, You X, Lotinun S, Zhang L, Wu N, Zou W. Mechanical sensing protein PIEZO1 regulates bone homeostasis via osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk. Nat Commun 2020;11:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Han L, Nookaew I, et al. Stimulation of Piezo1 by mechanical signals promotes bone anabolism. eLife 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeman E Bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2009;19:219–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robling AG, Turner CH. Mechanical signaling for bone modeling and remodeling. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2009;19:319–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Y, Wu X, Lei W, et al. TGF-beta1-induced migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with formation. Nat Med 2009;15:757–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin L, Raggatt LJ, Partridge NC. Parathyroid hormone: a double-edged sword for bone metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2004;15:60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langdahl B, Ferrari S, Dempster DW. Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2016;8:225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ominsky MS, Libanati C, Niu QT, et al. Sustained Modeling-Based Bone Formation During Adulthood in Cynomolgus Monkeys May Contribute to Continuous BMD Gains With Denosumab. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30:1280–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Bakker CM, Altman AR, Tseng WJ, et al. μCT-based, in vivo dynamic bone histomorphometry allows 3D evaluation of the early responses of bone resorption and formation to PTH and alendronate combination therapy. Bone 2015;73:198–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christen P, Ito K, Ellouz R, et al. Bone remodelling in humans is load-driven but not lazy. Nat Commun 2014;5:4855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu XS, Sajda P, Saha PK, et al. Complete volumetric decomposition of individual trabecular plates and rods and its morphological correlations with anisotropic elastic moduli in human trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:223–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel TK, Brodt MD, Silva MJ. Experimental and finite element analysis of strains induced by axial tibial compression in young-adult and old female C57Bl/6 mice. J Biomech 2014;47:451–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Butz KD, Duffy D, Niebur GL, Nauman EA, Main RP. Characterization of cancellous and cortical bone strain in the in vivo mouse tibial loading model using microCT-based finite element analysis. Bone 2014;66:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moustafa A, Sugiyama T, Prasad J, et al. Mechanical loading-related changes in osteocyte sclerostin expression in mice are more closely associated with the subsequent osteogenic response than the peak strains engendered. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:1225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glatt V, Canalis E, Stadmeyer L, Bouxsein ML. Age-related changes in trabecular architecture differ in female and male C57BL/6J mice. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birkhold AI, Razi H, Duda GN, Weinkamer R, Checa S, Willie BM. Mineralizing surface is the main target of mechanical stimulation independent of age: 3D dynamic in vivo morphometry. Bone 2014;66:15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambers FM, Schulte FA, Kuhn G, Webster DJ, Muller R. Mouse tail vertebrae adapt to cyclic mechanical loading by increasing bone formation rate and decreasing bone resorption rate as shown by time-lapsed in vivo imaging of dynamic bone morphometry. Bone 2011;49:1340–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lukas C, Ruffoni D, Lambers FM, et al. Mineralization kinetics in murine trabecular bone quantified by time-lapsed in vivo micro-computed tomography. Bone 2013;56:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altman AR, Tseng WJ, de Bakker CMJ, et al. Quantification of skeletal growth, modeling, and remodeling by in vivo micro computed tomography. Bone 2015;81:370–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie H, Cui Z, Wang L, et al. PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts induces angiogenesis during coupling with osteogenesis. Nat Med 2014;20:1270–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramchand SK, Seeman E. Reduced Bone Modeling and Unbalanced Bone Remodeling: Targets for Antiresorptive and Anabolic Therapy. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang LX, Balani YM, Trinh S, Kronenberg HM, Mu Y. [Differential effects on bone and mesenchymal stem cells caused by intermittent and continuous PTH administration]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2018;98:781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lotinun S, Sibonga JD, Turner RT. Differential effects of intermittent and continuous administration of parathyroid hormone on bone histomorphometry and gene expression. Endocrine 2002;17:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chow JW, Fox S, Jagger CJ, Chambers TJ. Role for parathyroid hormone in mechanical responsiveness of rat bone. Am J Physiol 1998;274:E146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim CH, Takai E, Zhou H, et al. Trabecular bone response to mechanical and parathyroid hormone stimulation: the role of mechanical microenvironment. J Bone Miner Res 2003;18:2116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnston S, Andrews S, Shen V, et al. The effects of combination of alendronate and human parathyroid hormone(1–34) on bone strength are synergistic in the lumbar vertebra and additive in the femur of C57BL/6J mice. Endocrinology 2007;148:4466–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamane H, Sakai A, Mori T, Tanaka S, Moridera K, Nakamura T. The anabolic action of intermittent PTH in combination with cathepsin K inhibitor or alendronate differs depending on the remodeling status in bone in ovariectomized mice. Bone 2009;44:1055–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu XS, Zhang XH, Guo XE. Contributions of trabecular rods of various orientations in determining the elastic properties of human vertebral trabecular bone. Bone 2009;45:158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi X, Liu XS, Wang X, Guo XE, Niebur GL. Effects of trabecular type and orientation on microdamage susceptibility in trabecular bone. Bone 2010;46:1260–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robling AG, Niziolek PJ, Baldridge LA, et al. Mechanical stimulation of bone in vivo reduces osteocyte expression of Sost/sclerostin. J Biol Chem 2008;283:5866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishiyama KK, Shane E. Clinical imaging of bone microarchitecture with HR-pQCT. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2013;11:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu XS, Stein EM, Zhou B, et al. Individual trabecula segmentation (ITS)-based morphological analyses and microfinite element analysis of HR-pQCT images discriminate postmenopausal fragility fractures independent of DXA measurements. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:263–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.