Abstract

In India, high rates of antibiotic consumption and poor sanitation infrastructure combine to pose a significant risk to the public through the environmental transmission of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The WHO has declared extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Escherichia coli a key indicator for the surveillance of AMR worldwide. In the current study, we measured the prevalence of AMR bacteria in an urban aquatic environment in India by detecting metabolically active ESBL-positive E. coli. Water samples were collected in duplicate from 16 representative environmental water sources including open canals, drains, and rivers around Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. We detected culturable E. coli in environmental water at 11 (69%) of the sites. Out of the 11 sites that were positive for culturable E. coli, ESBL-producing E. coli was observed at 7 (64%). The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli detected in the urban aquatic environment suggests a threat of AMR bacteria to this region.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, fecal indicator, water quality

INTRODUCTION

Despite efforts to achieve access to safe water and sanitation through the Millennium Development Goals, poor sanitation infrastructure remains prevalent in India (Vedachalam & Riha 2015). In 2015, the Joint Monitoring Programme found that only 39.6% of India’s population had access to improved sanitation facilities (WHO/UNICEF 2015). Poor sanitation conditions expose the public to a heightened risk of exposure to fecal-contaminated drinking water, endangering the lives of vulnerable populations (Ezeh et al. 2017). Pit latrines and other sanitation facilities that may be available in these environments often contaminate groundwater, which can lead to the spread of wastewater contaminated with bacteria that has developed antimicrobial resistance (AMR) through communal water sources (Graham & Polizzotto 2013). India is at a particular risk of AMR as its population is among the highest consumers of antibiotics globally, with the consumption of 4,500 defined daily doses per 1,000 individuals in 2015 (Kumar et al. 2013; CDDEP 2015).

There are sparse data on environmental sources of antimicrobial resistance in low- and middle-income countries. Animal and sewage systems can act as environmental reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance, but the extent of this depends on how humans and the environment interact, which can vary much between countries (Gwenzi et al. 2018). The studies that do exist often characterize bacteria molecularly rather than phenotypically (Bajaj et al. 2016). Previous studies have demonstrated a discrepancy between results from phenotypic and molecular data, so characterizing bacteria phenotypically is vital to understand the spread of antimicrobial resistance (Lob et al. 2016).

The WHO has declared extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli a key indicator for the surveillance of AMR worldwide (Matheu et al. 2017). ESBL-producing E. coli has been detected in hospital wastewater and in pig feces in India, so it is possible that the bacteria from hospitals and pig farming could be contaminating where people cook, do laundry, and live (Diwan et al. 2012; Nirupama et al. 2018; Puii et al. 2019). ESBL-resistant determinants were found in sewage water in Delhi, and it is unknown how far this resistance is spread throughout India (Gogry et al. 2019). In this study, we aimed to document the prevalence of ESBL-positive E. coli in environmental water sources along the Ganga River in Kanpur, in Northeast India. Wastewater is dumped untreated into the waterways of Kanpur so they are likely to be reservoirs of antimicrobial resistance (Zia & Devadas 2008). In this setting, pig farming is a common profession and often takes place close to people’s homes (Sanjukta et al. 2019). Although ESBL-producing E. coli has been studied in pig feces in this area, the prevalence of this resistant bacteria in the urban environment of Kanpur is unknown. We recognize that our dataset of 16 samples is not large, and are considering this study a pilot study to prepare for sampling in a larger spatial context. This study characterizes the presence of E. coli and ESBL-producing E. coli in environmental water throughout Kanpur, India.

METHODS

Sample collection

Water samples were collected near open drains, canals, and rivers in and around the city of Kanpur. Sampling locations were chosen by predetermining locations with moving water to maintain consistency across samples as the bacteria profile of stagnant water can be very different. All samples were collected from areas where people frequently gather to investigate the plausibility of human exposure.

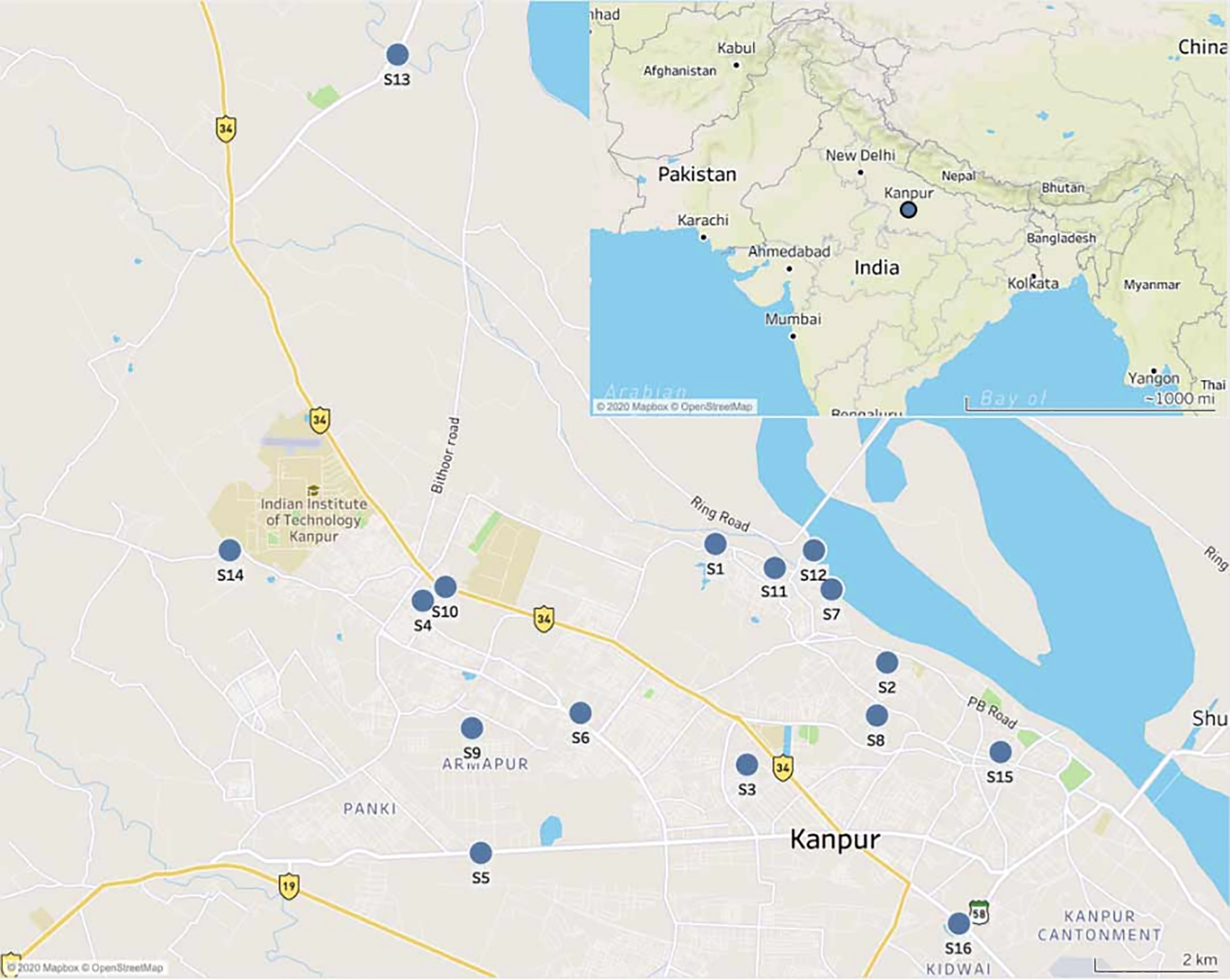

Water samples were collected from 16 different locations around Kanpur, indicated in Figure 1. Samples were collected from March to April 2019. Two 100 mL samples of water were collected from each of the sites. The samples were collected in sterile plastic bags. A negative control sample was also collected where DI water was poured from a sterile container into a plastic bag at each site. The water samples were kept in portable coolers with ice to minimize further replication of microorganisms during sampling. The samples were processed in the laboratory within 2 hours of collection.

Figure 1 |.

Location of sampling sites in Kanpur, India.

E. coli culture growth and enumeration

The water samples were serially diluted up to 100-fold to achieve countable plates in the 30–300 coliform forming units (CFU) range. One mL of each dilution along with the field sampling negative control was pipetted onto its own Compact Dry EC plate (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA). After the water samples were plated, 1 mL of DI water was pipetted onto a separate Compact Dry EC plate as another negative control. Compact Dry EC plates were used because they allow E. coli to be distinguished from other coliforms using chromogenic enzyme substrates. These substrates allow E. coli colonies to turn blue and the other bacterial colonies to turn red (HyServe Compact Dry). The plates were incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 24–30 hours and then the E. coli colonies were identified and enumerated.

ANTIMICROBIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY TESTING

E. coli ESBL pre-screening

After enumeration, a presumptive E. coli colony was selected from the Compact Dry plate and placed in a test tube with 0.11 g ± 0.02 g of Aquatest medium for growth, along with 10 μg (1μg/mL) of cefotaxime powder and 10 mL sterile water (Bain et al. 2015). Aquatest was used because it is a low-cost test that has been validated as highly sensitive and specific for detecting E. coli when compared to Colilert-18, Compact Dry, and MI agar (Franziska et al. 2019; Brown et al. 2020), which has been validated for culturing isolates for resistance testing. The solution turned pink to indicate the growth of metabolically-active of E. coli after 24 hours of incubation. This suggested the culture solution contained ESBL-producing E. coli, and these pink culture solutions were streaked on disk diffusion plates to further confirm the presence of ESBL-producing E. coli.

DISK DIFFUSION

Following pre-screening, ESBL-producing E. coli were confirmed by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) modified confirmatory test for phenotypic detection of ESBLs (Poulou et al. 2014). This updated test has a sensitivity of 97.5% and a specificity of 100% for detecting ESBLs in Enterobacteriaceae even in the presence of other types of β-lactam resistance.

This test uses the disk diffusion technique with a combination of cefotaxime (CTX) and ceftazidime (CAZ) with and without the presence of clavulanic acid (CA). Cefotaxime and ceftazidime were used because they are both antibiotics of the class cephalosporin, each of which demonstrates enhanced activity in the presence of CA (Rawat & Nair 2010). Therefore, the difference in the size of the growth-inhibitory zone with and without CA can be used to determine if ESBL-producing E. coli is present. Boronic acid was used to inhibit AmpCs and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs), which may otherwise be detected as ESBLs. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was used to inhibit metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) which also may mask the presence of ESBL.

The Muller-Hinton agar plates were prepared and autoclaved with the sampling solution. Stock EDTA and BA solutions were prepared in advance of sampling and refrigerated. The EDTA solution had a concentration of 0.1 MEDTA and the BA solution was made by dissolving phenylboronic acid at a concentration of 40 mg/ml. Ten μl of the 0.1 MEDTA and 10 μl of the BA solution were dispensed onto each antibiotic disk, CTX (30 μg) and CAZ (30 μg) with or without CA (10 μg) were also added. Then the plates were inoculated with the solution where ESBL-producing E. coli was detected with the color change of the Aquatest medium. The four antibiotic disks were pressed into equally divided slices around the plate. After inoculation with presumptive ESBL-producing E. coli from the Aquatest broth, the plates were incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C.

If the growth-inhibitory zone diameter for either CTX or CAZ where CA was present were ≥5 mm larger than the corresponding growth-inhibitory zone without CA, the sample was deemed positive for ESBL production (Poulou et al. 2014).

RESULTS

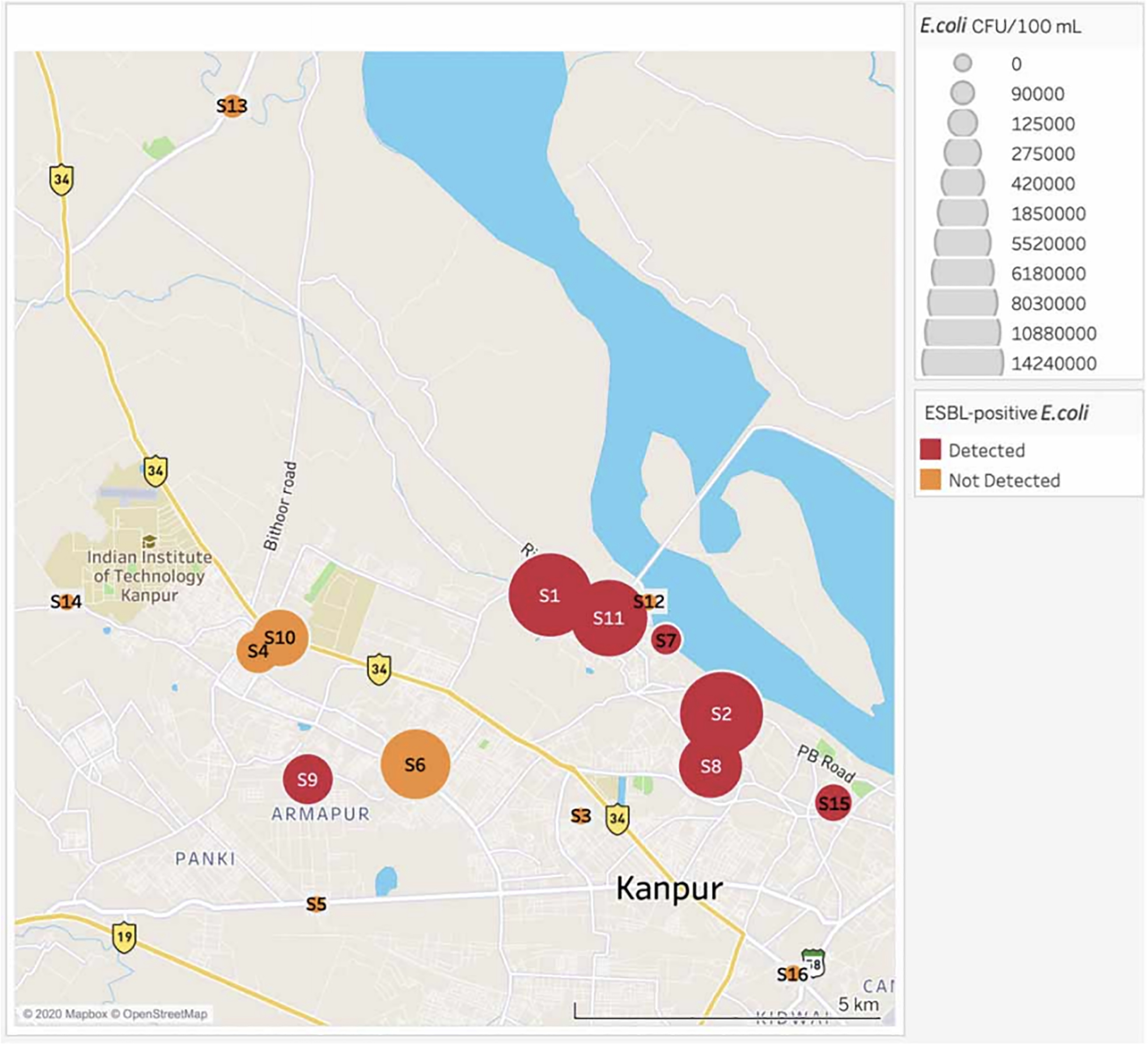

E. coli quantities measured in the water samples ranged from undetectable to 1.4 × 107 CFU/100 mL (median: 4.2 × 105 CFU/100 mL), as shown in Table 1. From the sites sampled (n = 16), 69% contained culturable E. coli. Out of the sites that contained detectable E. coli, ESBL-producing E. coli was found at 64%.

Table 1 |.

Average CFU/mL of E. coli across 16 sites in Kanpur, India

| Site ID | ESBL-producing E. coli | Average E. coll CFU/100 mL |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| S1 | X | 1.4 × 107 |

| S2 | X | 1.4 × 107 |

| S3 | ND | |

| S4 | 4.2 × 105 | |

| S5 | ND | |

| S6 | 8.0 × 106 | |

| S7 | X | 1.2 × 105 |

| S8 | X | 6.2 × 106 |

| S9 | X | 1.9 × 106 |

| S10 | 5.5 × 106 | |

| S11 | X | 1.1 × 107 |

| S12 | ND | |

| S13 | 9.0 × 104 | |

| S14 | ND | |

| S15 | X | 2.8 × 105 |

| S16 | ND | |

Samples were collected in duplicate from the sites and averaged. ND stands for no detected colonies. The negative control collected at each site had no detected colonies. The negative controls from water in the laboratory had no detected colonies.

DISCUSSION

The water tested in this study is generally not used as daily drinking water, but it is sometimes consumed as part of a religious ritual, particularly the water sampled from the Ganga and its tributaries, or out of necessity. E. coli counts in seven of the canals tested, all of which run uncovered through communities, were greater, and in three of them an order of magnitude greater, than the average estimated E. coli count of 1.5 × 106 CFU/100 mL from a study of untreated wastewater in Canada (Payment et al. 2001). Three of the canals tested in Kanpur had greater E. coli counts than the estimated E. coli count of 1.05 × 107 CFU/100 mL in untreated wastewater in South Africa (Teklehaimanot et al. 2014), and two had greater E. coli counts than the estimated E. coli count of 1.35 × 107 CFU/100 mL in untreated wastewater in Portugal (Da Costa et al. 2008). The concentrations of bacteria found in the canals studied suggests that the people living around them may be at risk of illness due to potential exposure.

The cluster of ESBL-producing E. coli sites around the Ganga and its tributaries, as shown in Figure 2, indicates that this heavily trafficked waterway is likely to harbor and contribute to the spread of AMR bacteria. The most comparable urban aquatic study in India is a study that was conducted along the Yamuna River in Delhi (Bajaj et al. 2016). Sixteen percent of the E. coli strains they analyzed were ESBL-producing E. coli. This is not a direct comparison to the samples collected in this study as the Yamuna study used molecular and not phenotypical analysis. However, the differences in the proportion of samples with ESBL-producing E. coli detected in the Yamuna River versus the Ganga are striking, because the Yamuna River exists in a similarly highly populated region surrounded by poor sanitation facilities. Potentially, this supports the hypothesis that specific regional factors to Kanpur, such as the heavy concentration of swine farming in the area, led to a higher proportion of ESBL-producing E. coli. Elucidating the source of this environmental contamination and preventing it is essential for stopping the spread of AMR.

Figure 2 |.

Map displaying the average E. coli CFU/100 mL and ESBL-positive E. coli presence.

CONCLUSIONS

This study detected surprisingly high proportions of ESBL-producing E. coli in an urban aquatic environment in India. Because ESBL-producing E. coli is a key indicator for the surveillance of AMR worldwide, the high prevalence of these bacteria in India suggests a threat of AMR in this region.

HIGHLIGHTS.

This study provides further information for the understanding of WASH and the environmental transmission of AMR.

This study provides data useful for motivating studies of environmental transmission of AMR.

This study characterized the threat of AMR bacteria to Kanpur, India.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AJ was supported by a Fulbright-Nehru Fellowship jointly funded by the United States Department of State and the Republic of India. This material is partly based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 1653226. Funding organizations were not involved in the planning or execution of this study.

Contributor Information

Ann Johnson, Yale School of Medicine, 333 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT, 06510, USA.

Olivia Ginn, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, 30332, USA.

Aaron Bivins, Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame, 156 Fitzpatrick Hall, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA.

Lucas Rocha-Melogno, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Duke University, Durham, NC, 27708, USA.

Sachchida Nand Tripathi, Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, Kanpur, 208016, India.

Joe Brown, Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Ford Environmental Science and Technology Building, 311 Ferst Drive, Atlanta, GA 30332 USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All relevant data are included in the paper or its Supplementary Information.

REFERENCES

- Bain RES, Woodall C, Elliott J, Arnold BF, Tung R, Morley R, Preez M, Bartram J, Davis A, Fundry S & Pedley S 2015. Evaluation of an inexpensive growth medium for direct detection of Escherichia coli in temperate and subtropical waters. PLoS ONE 10 (10), e0140997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj P, Kanaujia PK, Singh NS, Sharma S, Kumar S & Virdi JS 2016. Quinolone co-resistance in ESBL- or AmpC-producing Escherichia coli from an Indian urban aquatic environment and their public health implications. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 23 (02), 1954–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Bir A & Bain RES 2020. Novel methods for global water safety monitoring: comparative analysis of low-cost, field-ready E. coli assays. npj Clean Water 3 (9). [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP) 2015. Drug Resistance Index and Resistance map. Available from http://www.cddep.org (accessed 3 February 2020).

- Da Costa P, Vaz-Pires P & Bernardo F 2008. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolated in wastewater and sludge from poultry slaughterhouse wastewater plants. Journal of Environmental Health 70 (7), 40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan V, Chandran S, Tamhankar A, Lundborg C & Macaden R 2012. Identification of extended-spectrum β-lactamase and quinolone resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from hospital wastewater from central India. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 67 (4), 857–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeh A, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, Chen Y-F, Ndugwa R, Sartori J, Mberu B, Melendez-Torres GJ, Haregu T, Watson S, Caiaffa W, Capon A & Lilford R 2017. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The Lancet 389 (10068), 547–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franziska G, Clair-Caliot SJM, Mugume G, Johnston DS, Bain RB, & Timothy RES & R J. 2019. Evaluation of the novel substrate RUGTM for the detection of Escherichia coli in water from temperate (Zurich, Switzerland) and tropical (Bushenyi, Uganda) field sites. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 5, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Gogry FA, Siddiqui MT & Rizqanul Haq QM 2019. Emergence of mcr-1 conferred colistin resistance among bacterial isolates from urban sewage water in India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26, 33715–33717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JP & Polizzotto ML 2013. Pit latrines and their impacts on groundwater quality: a systematic review. Environmental Health Perspectives 121 (5), 521–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwenzi W, Musiyiwa K & Mangori L 2018. Sources, behaviour and health risks of antimicrobial resistance genes in wastewaters: a hotspot reservoir. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering S2213–3437 (18), 30101. [Google Scholar]

- HyServe Compact Dry Manual. https://hyserve.com/files/Compact-Dry_72dpi_engl.pdf (accessed 3 February 2020).

- Kumar SG, Adithan C, Harish BN, Sujatha S, Roy G & Malini A 2013. Antimicrobial resistance in India: a review. Journal of Natural Science Biology and Medicine 4 (2), 286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lob SH, Biedenbach DJ, Badal RE, Kazmierczak KM & Sahm DF 2016. Discrepancy between genotypic and phenotypic extended-spectrum β-lactamase rates in Escherichia coli from intra-abdominal infections in the USA. Journal of Medical Microbiology 65 (9), 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheu J, Aidara-Kane A & Andremont A 2017. The ESBL Tricycle AMR Surveillance Project: A Simple, one Health Approach to Global Surveillance. One Health. Available from: http://resistancecontrol.info/2017/the-esbl-tricycle-amr-surveillance-project-a-simple-one-health-approach-to-global-surveillance/ (accessed 3 February 2020).

- Nirupama KR, Kumar ORV, Pruthvishree BS, Sinha DK, Murugan MS & Singh BR 2018. Molecular characterisation of blaOXA48 carbapenemase, extended spectrum betalactamase (ESBL) and Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli isolated from farm piglets of India. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 13, 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payment P, Plante R & Cejka P 2001. Removal of indicator bacteria, human enteric viruses, Giardia cysts, and Cryptosporidium oocysts at a large wastewater primary treatment facility. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 47 (3), 188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulou A, Grivakou E, Vrioni G, Koumaki V, Pittaras T, Spyrous P & Tsakris A 2014. Modified CLSI extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) confirmatory test for phenotypic detection of ESBLs among Enterobacteriaceae producing various β-lactamases. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 52 (5), 1483–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puii LH, Dutta TK, Roychoudhury P, Kylla H, Chakraborty S, Mandakini R, Kawlni L, Samanta I, Bandopaddhay S & Singh SB 2019. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Shiga-toxin producing-Escherichia coli in piglets, humans and water sources in North East region of India. Letters in Applied Microbiology 69, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat D & Nair D 2010. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Gram negative bacteria. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases 2 (3), 263–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjukta R, Surmani H, Mandakini K, Milton A, Das S, Puro K, Ghatak S, Shakuntala I & Sen A 2019. Characterization of MDR and ESBL-producing E. coli strains from healthy swine herds of north-eastern India. The Indian Journal of Animal Sciences 89, 625–631. [Google Scholar]

- Teklehaimanot GZ, Coetzee MAA & Momba MNB 2014. Faecal pollution loads in the wastewater effluents and receiving water bodies: a potential threat to the health of Sedibeng and Soshanguve communities, South Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 21, 9589–9603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedachalam S & Riha S 2015. Who’s the cleanest of them all? sanitation scores in Indian cities. Environment and Urbanization 27 (1), 117. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNICEF 2015. Joint Monitoring Programme. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zia H & Devadas V 2008. Urban solid waste management in Kanpur: opportunities and perspectives. Habitat International 32 (1), 58–73. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the paper or its Supplementary Information.