Abstract

Frontline officials (such as mayors and commissioners) are responsible for local-level responses to the COVID-19 pandemic across the United States. Their actions and attitudes, either in support of or opposition to public health recommendations, have resulted in widespread variation in local-level pandemic response. Despite evidence that religion significantly impacts the general public’s response to the pandemic, the influence of religion on officials’ behaviors and attitudes is unknown. Using a unique, two-wave, representative survey of frontline officials, we examine how religion influenced officials’ reported personal health behaviors (mask wearing, social distancing) and attitudes toward institutional reopenings. Results show high levels of compliance with public health recommendations, but religious nationalism negatively influences all outcomes. Other religious factors, like affiliation and attendance, vary in their influence and even work differently among officials compared to the general public. Frontline officials are key for understanding how religion influences the pandemic and state action more generally.

Keywords: religion and state, street-level bureaucracy, COVID-19, public administration, Christian nationalism, public health

INTRODUCTION

Responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have been uneven and unequal across the United States. Thousands of local governments have been tasked with implementing state and federal policies and mobilizing local compliance, often with limited guidance and constrained resources. Many local government officials (“frontline officials”) have personally modeled disease prevention behavior and helped enforce public health mandates (Van Bavel et al. 2020). But others have violated public health recommendations either through their own behaviors or by voicing opposition to state mandates for institutional closures (Brzezinski et al. 2020; Gupta et al. 2020). What explains differences in the behaviors and attitudes of frontline officials, those whose actions can have immediate consequences for the public health of local communities? While a growing body of work examines how religion has influenced the attitudes and behaviors of the general public during the pandemic (Djupe and Burge 2020; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020a, 2020b; Smothers, Burge, and Djupe 2020), it has not yet examined how religion may have influenced the behaviors of frontline officials. In this paper, we fill this gap by examining how religion shaped frontline officials’ reported COVID-19 personal health behaviors—such as donning a mask and practicing social distancing—as well their support for COVID-19 mitigation strategies that involved the closing of key economic and civic institutions. We find that, while there is a great deal of compliance with public health recommendations overall, religious factors—especially religious nationalism and religious affiliation—are important predictors of both reported personal behavior and support for public health directives among frontline officials during the pandemic.

As Baker et al. (2020:360) argue, understanding the influence of religion on “disease transmission and mitigation” during the pandemic is crucial. To do so, however, it is especially important to focus on individuals who have greater power than the general public to shape the course of the pandemic and the public good in general. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the governing power of frontline officials, who number in the hundreds of thousands across the United States, has become increasingly visible. Because the U.S. public health system is so decentralized (Baker et al. 2005), frontline officials have been central actors in shaping local response to the COVID-19 threat. These frontline officials have formal duties, such as supporting state-issued public health mandates, as well as informal responsibilities, such as communicating public health information and modeling health behaviors (Van Bavel et al. 2020). Numerous factors can influence frontline officials’ actions (Lipsky [1980] 2010), and, as county clerk Kim Davis’ high-profile refusal on religious grounds to issue a same-sex couple a marriage license demonstrates (Tebbe 2017), religion is often an important one (Sullivan 2018). Indeed, one reason why it has been so difficult to achieve a unified public health response to the pandemic is that some frontline officials face competing demands between their duty to protect public health and their identities, both religious and political, which may discourage their support of public health recommendations. In sum, to understand the local shape of the pandemic response requires examining frontline officials, and to understand frontline officials requires examining their religion.

Much existing work on religion in the pandemic implicitly treats governmental action as something that happens to religious persons, and to which they must respond. Echoing Weberian institutional analyses as well as strands of secularization theory (Weber 1978), this framing envisions religion and government as separated institutional spheres, frequently opposed, residing in delineated organizations and enacted through separated actors. In contrast, we view government as “inhabited” by individuals who are motivated by personal identities drawn from their religious experiences and affiliations—identities that can complement or compete with commitments deriving from their institutional roles and contexts (Banaszak 2010; Hallett and Ventresca 2006; Lipsky [1980] 2010).

Drawing upon an original, two-wave, representative survey of frontline officials (including mayors, council members, managers) administered prior to and following the start of the pandemic, we analyze officials’ reported personal health behaviors (social distancing, masking) and their attitudes toward public health directives (reopening schedules for closed social institutions). We find overall high levels of compliance with recommended personal health behaviors and high levels of support for delaying the reopening of institutions. At the same time, we also show multiple ways that religion may contribute to either following or resisting personal health behavior and public health directives. Regarding personal health behaviors, religious nationalism and Evangelical Protestant affiliation predict disregard for social distancing and masking, while nonliteral beliefs about the Bible and Catholic affiliation predict engagement in those behaviors. Regarding public health attitudes, religious nationalism and Evangelical Protestant affiliation predict a desire for more immediate lifting of restrictions, whereas a low level of worship service attendance and Catholic affiliation predict a preference for a slower reopening.

Our results make clear that religion influences frontline officials’ governance-related behaviors and attitudes, with some religious factors influencing alignment with public health recommendations and other factors leading to opposition. We show evidence of how religion may influence frontline officials differently than the general public, as well as evidence that the religious nationalism influencing pandemic politics among the general public also significantly affects local governance. Overall, our results provide the first systematic analysis of religion among frontline officials, help to explain local-level variation in response to the pandemic, and point toward an exciting new avenue for understanding how religion shapes state processes more generally.

LINKING FRONTLINE OFFICIALS, GOVERNANCE, AND RELIGION

Local Government and the Pandemic

Frontline officials are the more than half-million government actors, both elected and appointed, who lead municipal governments, deliver public services, and make local laws (Lawless 2012). The activity of frontline officials occurs across 40,000 local governments, including townships, counties, cities, and school districts. Most frontline officials serve in small jurisdictions, their positions are typically part-time, and their work is done in view of constituents who have regular access to question or influence officials’ actions. Frontline officials are the tangible, accountable representative of the state with whom citizens are most likely to interact (Lipsky [1980] 2010; Sheingate 2009).

In previous disasters, local officials responded in divergent ways, resulting in widely varied public health and safety outcomes (Blendon et al. 2004). In a successful disaster response, local officials coordinate services, provide authoritative information to their constituents, and signal the efficacy of public response to threat (Tierney 2014). In contrast, they can also inhibit effective response by signaling distrust of other governmental authorities, withholding information, or providing conflicting advice (Clarke and Chess 2008).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, states have had primary authority for addressing public health, devolving financial resources and enforcement authorities for disease control to municipalities at the county and subcounty level. Many states do not allow localities to pre-empt state-level policies with policies of their own that are more powerful, but localities can choose whether and how to actively support state policies (Wagner, Rainwater, and Carter 2020). As a result, some frontline officials have facilitated enforcement of state mandates while others have vocally resisted mandates and behaved in opposition to public health guidance (Multistate Associates 2020).

Frontline Officials, Religion, and Civil Religion

Surprisingly, little systematic research exists on how frontline officials have responded to the pandemic and none has focused on the religious influences of their responses. Further, there is no systematic theory of how religion influences frontline officials which we could then apply to the pandemic. We draw from two research streams that suggest different ways that religion may influence local government action by shaping attitudes toward the public good.

One stream, best illustrated by Tocqueville ([1838] 2004), emphasizes the positive, cohesive contribution of religion to public life. Through its promotion of “mores,” religion tempers the self-interest of individuals, increases the capacity for self-government, and orients individuals to the common good of the wider citizenry (Mansfield 2016). In this stream, religion is assumed to influence officials and officials are assumed to engage religion toward prosocial ends. In the past few decades, research has provided evidence for a weak version of the Tocqueville view. Public officials, from members of Congress (Pew Research Center 2021) to government employees (Houston, Freeman, and Feldman 2008), are more likely to be religious than the general population and less likely to be nonreligious. Many local officials perceive and seek out religion’s civic contributions. For example, mayors and council members participate in events that promote local civil religion (Demerath III and Williams [1992] 2014) and partner with religious groups to solve social problems (Lichterman 2005; Owens 2008). These studies suggest that most officials will have religious identities and that religion will support governmental policies that promote the public good of a community.

A second stream, illustrated by some liberal theorists of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, suggests that governance problems and inequality in governmental provision might be produced by the religion of governmental officials (Rawls 1972). Religion, like other thick identities, may produce in-group favoritism and legitimate narrow conceptions of the good that conflict with public goods. This approach suggests that the demands of idealized neutral state bureaucratic administration are irreconcilable with the demands of religion. Some of these assumptions have been substantiated, especially through research on religion as a component of “personal representation” (Burden 2007). For example, religious affiliation and religiosity influence elected state officials’ support of partisan legislation. Legislators for whom religious identity is more salient are more likely to vote conservatively on a range of policy issues (Mctague and Pearson-Merkowitz 2015; Yamane and Oldmixon 2006). And versions of Christian nationalism have long motivated policies that emphasize exclusion and inequality in the name of preserving a “Christian nation” (Gorski 2017). Whitehead and Perry (2020) argue that contemporary Christian nationalists, which include elected officials, promote not only state support for Christianity, but nativist immigration policies and economic libertarianism as well.

Within this second stream, some research looks specifically at how religion influences local officials toward minority or discriminatory positions. For example, Berkman, Pacheco, and Plutzer (2008) show that religious belief is a major determinant in how public-school science teachers implement state mandates to teach evolution. A recent audit study of school principals shows that principals’ perception of parents having a minority religious identity impacts their willingness to engage with them (Pfaff et al. 2021).

THEORIZING RELIGIOUS INFLUENCE ON FRONTLINE OFFICIALS DURING THE PANDEMIC

These two streams of research suggest that religious differences among elected officials should be part of explaining the diversity of governmental action, with religion potentially undergirding support or opposition to state policies that promote equitable public goods. We note, however, that they generally do not clarify how religion relates to the unique type of governance that occurs at the local level. To correct this deficiency, we draw on street-level bureaucracy (SLB) theory, a research paradigm that explains how government administration occurs in ways not anticipated by legal–rational frameworks (Adler et al. 2020; Lipsky [1980] 2010). In particular, SLB theory draws attention to how governmental action occurs through the action of individual agents operating in local contexts (Lipsky [1980] 2010; Morgan and Orloff 2017). In classic studies, street-level bureaucrats were social workers, beat cops, and other low-level service providers who had regular interaction with citizens, working with constrained resources and under weak oversight. Consequently, they had considerable discretion to make decisions in light of specific circumstances (Lipsky [1980] 2010; Watkins-Hayes 2009), a form of autonomy that generated variation across different arms of the state. By advancing a vision of government working through individuals in local contexts, SLB theory provides an important corrective to the dominant view that bureaucratization leads to coherent or consistent action across governmental bodies.

We extend SLB theory to encompass frontline officials, a wider category that includes not simply government agents but also elected and appointed officials at the local level. Two primary aspects of SLB inform our study. First, SLB theory illuminates the informal, public nature of frontline officials’ daily actions. Frontline officials are highly visible to local citizens through regular town meetings, public ceremonial duties, and press coverage. Even when they are not governing, their high status in the community symbolically connects their personal behavior to their public role. Thus, SLB theory suggests that any analysis of the impact of religion on local officials should consider how religion influences not only their policy preferences, but also a broad range of actions taken in view of the public.

To that end, we examine two types of pandemic-related actions by local officials. First, we examine officials’ reported personal health behaviors, which can be publicly visible and serve as cues to citizens regarding how they should respond to the pandemic. Second, we examine officials’ attitudes toward institutional reopening after closures mandated by state authorities. Institutional closures, such as those applied to nonessential businesses, schools, and places of worship, have been implemented during the pandemic in order to slow disease spread. Attitudes toward institutional reopening likely mattered to whether and how local officials supported or opposed local compliance with closures.

Second, SLB theory shows that frontline officials implement their authority in complicated ways in response to a variety of influences. In particular, frontline officials govern by exercising discretion, especially when bureaucratic constraints are weak, resources are limited, and easy solutions do not exist. Discretion is a structural feature of frontline work, allowing flexibility for officials who often balance multiple interests while seeking to act in “the public interest” (Zacka 2017). Frontline officials draw on a number of potentially conflicting inputs, including role expectations, community context, and their own values about the meaning of the public interest (Berkman and Plutzer 2010; Lipsky [1980] 2010; Zacka 2017). Thus, religious factors exist alongside other factors that motivate frontline officials’ governmental actions. We examine how three religious factors may influence officials’ actions: religious affiliation, practice, and belief.

Religious Affiliation

Religious affiliation is linked to different conceptions of appropriate governmental authority, including whether the state has equivalent authority to other institutional entities (Martí 2020) and whether religious groups should engage with the state. For example, White Evangelicalism is characterized by an anti-institutionalism that sees inequality as due to individual decision-making, not systemic policies or institutional processes (Emerson, Smith, and Sikkink 1999). As a result, whereas those in the Catholic and Black Protestant religious traditions generally embrace state support for social services, those in the White Evangelical tradition oppose it (Owens 2008; Wilcox and Jelen 2016). Further, Mainline and Catholic religious traditions are generally more supportive than the White Evangelical tradition of scientific authority (Evans and Hargittai 2020). Studies of elites in nonpolitical fields show that these traditions influence how faith shapes elites’ approach to their professional lives: in a study of journalists Schmalzbauer (2003) shows that Catholics attend more to consensus, community, and social justice, whereas Evangelicals are more apt to adopt conflictive, individualistic, and moralistic stances. Because of such skepticism toward science and government intervention, there is evidence from the pandemic that Evangelical Protestants may be more resistant to disease prevention behaviors and may also resist governmental closures of businesses and religious organizations (Evans and Hargittai 2020; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020b). We expect that, net of other factors, officials affiliated with the Evangelical Protestant tradition, in contrast to Mainline Protestants and Catholics, will be less likely to adopt recommended public health behaviors and more likely to support immediate institutional reopenings.

Religious Practice

Religious practice is an indicator of commitment to religion and the salience of religion to identity. Once the influences of religious affiliation and belief are accounted for, religious attendance is associated with attitudes and behaviors that reinforce social stability of communities, such as family formation, but is also associated with progressive attitudes and behaviors, such as greater tolerance of immigrants and greater involvement with civic organizations (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995; Whitehead and Perry 2020). During the pandemic, there is evidence that religious attendance is positively associated with reported behaviors (such as handwashing and mask wearing) (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020b). We expect that, because of the association between religious attendance and other prosocial outcomes, attendance will be positively associated with adopting recommended personal health behaviors and support for delayed institutional reopening (Smothers, Burge, and Djupe 2020).

Religious Beliefs

Bible views

Specific religious beliefs can be associated with a wide range of attitudes and behaviors. Literal scriptural beliefs are an identity statement associated with skepticism toward governmental power and nonscriptural bases of authority (Franzen and Greibel 2013). For example, Gauchat (2015:734) finds that “belief that the Bible is the literal word of God is negatively associated with support for scientifically informed government policy.” During the pandemic, Biblical literalism is associated with opposition to government policies that restrict religious practice for the protection of public health (Smothers, Burge, and Djupe 2020). Based on past research that demonstrated a link between Biblical literalism and skepticism toward governmental authority, we expect that officials with more traditional views of the Bible will be less likely to report adopting recommended health behaviors and will be more likely to support immediate institutional reopenings.

Religious nationalism

Beliefs about religious nationalism have recently been emphasized in the study of religion and politics (Whitehead and Perry 2020). Religious nationalism connects ideas about the role of religion in national identity, governmental policy, and national life (Gorski 2017). Religious nationalism works as a cognitive schema that provides implicit shortcuts to how religious authority should connect to public life (Delehanty, Edgell, and Stewart 2019). Individuals with lower levels of religious nationalism have greater openness to religious diversity, skepticism about the protective role of government in establishing religion, and skepticism of the primacy of religious liberty claims (Whitehead and Perry 2020). Individuals with higher levels of religious nationalism oppose religious diversity, support a protective role for government toward religion, and have an expansive view of personal claims to religious liberty (Bennett 2017; Delehanty, Edgell, and Stewart 2019). Among the general public during the pandemic, religious nationalism is positively associated with opposition to government restrictions on religion (Smothers, Burge, and Djupe 2020) and is one of the strongest influences on incautious behavior (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020b). Further, religious nationalism has been linked to specific pandemic-related restrictions among the general public. Those with higher levels of religious nationalism would prefer to “save the economy” by permitting unrestrained personal behavior instead of social distancing (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020a). We expect that officials with higher levels of religious nationalism will be less likely to adopt recommended personal health behaviors and will be more likely to support immediate institutional reopenings.

Extending Public Opinion Research to Frontline Officials

Nearly all of the relevant research on COVID-19 has focused on the general public. Since frontline officials are drawn directly from local communities and most serve on a part-time basis, this could lead us to conclude that findings on the general public will extend to them as well, with religious characteristics being especially important to their reported behaviors and attitudes.

However, the essential dilemma highlighted by SLB theory is the tension of conflicting demands. Mayors, council members, and appointed officials are influenced by professional role norms; they have legal obligations to faithfully implement state and federal policies; and they are accountable to local citizens for whom they visibly embody governmental power. These demands could lead frontline officials to err on the side of professional role expectations and state guidelines, favoring personal health behaviors and institutional closures during a challenging public health crisis. Or, since frontline officials have considerable discretion regarding state and federal guidelines, they may give greater weight to local public preferences that oppose a robust public health response. Or, facing uncertainty, frontline officials may draw on components of their personal identities, particularly religion and political affiliation. This process of balancing conflicting demands as part of active leadership is similar to that experienced by clergy who “read” their congregation and local context, generally opting for opinion stances and organizational processes that downplay difference between leader and the led to avoid conflict (Campbell and Pettigrew 1959).

Thus, it is possible that local officials will be influenced by professional public health concerns, by local public context, and by their own identity components, with these demands working in different directions. If public health concerns about COVID-19 spread dominate, we would expect higher COVID-19 rates to predict adoption of recommended personal health behaviors and support for delayed institutional reopenings. If local public context is critical, we would expect the political and religious characteristics of the community to play a major role. In this case, we would expect that local contexts characterized by religious and political affiliations related to pandemic skepticism encourage opposition to recommended personal health behaviors and delayed institutional reopenings among frontline officials. Finally, if personal identity is most important, then we would expect that officials’ partisan and religious identities will play a greater role than local health indicators and the public context. In this last case, religious factors would play out according to our review above, with some leading toward support of, and some opposition to, COVID-19 prevention and protection strategies.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

We use data from two linked surveys conducted in Pennsylvania in February to May 2020. Pennsylvania is ideal for examining variation among local officials’ COVID-19-related actions for numerous reasons. First, it is one of only a handful of states that makes publicly available the name and contact information of all elected and nonelected officials in the state, constituting a comprehensive sampling frame (Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (PDCED) 2020b). Second, Pennsylvania is diverse in ways that mirror the United States in regard to median age, educational level, and rural location of the population (Pennsylvania State Data Center 2012, 2020; U.S. Census Bureau 2010, 2019, 2020). Third, Pennsylvania was especially susceptible to a disparate public health response by local officials. Only six of 67 counties have a public health department, and most municipalities have no public health services (Advisory Committee on Public Health 2013). Fourth, at the time of our survey, Pennsylvania’s communities had varied levels of coronavirus community spread, morbidity, and mortality. In this sense, Pennsylvania reflected the varied conditions across the United States at that time. Finally, Pennsylvania has been especially beset by a partisan divide that has grown over the past decade (Lai and Whalen 2019), which resulted in well-organized pushback to the Democratic governor’s orders during the pandemic (Rubinkam and Scolforo 2020). While the precise patterns may differ in other states, Pennsylvania affords the opportunity to observe how religion impacts local officials’ response to the pandemic.

The first survey was a long-planned study focusing on the religious identities of local officials and their attitudes toward church–state issues and was fielded on February 24th using a combination of mail and e-mail collection techniques. Recruitment and collection were managed by the Survey Research Center at the Pennsylvania State University through the Qualtrics platform. It resulted in 1,036 valid responses for an AAPOR RR6 response rate of 22%. Here, we only use responses gathered on or before March 19th, the day that the governor of Pennsylvania declared that a statewide closure of all “non-life sustaining business operations and services” would go in effect on March 21st (Fullman et al. 2020)1 (see Supplementary Appendix A for a timeline of the survey set along national- and state-level COVID-19 events).

Given our prior investment in developing the sampling frame and initial survey, we were able to extend our research with a second survey that was entirely online and focused on officials’ attitudes about COVID-19 and the response of their municipalities. The survey was fielded between May 1st and May 11th, 2020 on the Qualtrics survey platform. A total of 1,386 officials completed the survey. The AAPOR RR6 response rate was 23%. In the five weeks preceding the survey, the Pennsylvania governor had declared an emergency; extended stay-at-home orders to cover the whole state; and declared that only certain life-sustaining activities could occur. Schools, in-person restaurant dining, and state parks were closed. While religious congregations were never mandated to close, the governor’s office strongly encouraged alternative forms of worship and many political actors accused the state of restricting religion (PDCED 2020a). On May 1st, plans for slow, partial “reopening” for some portions of the state were announced, with those plans going into effect on May 8th (Fullman et al. 2020).

Each survey is representative of senior elected municipality leaders (mayors, council presidents, chairpersons, supervisors, council members, commissioners) and executive appointed staff (manager, secretaries) in all Pennsylvania municipalities, except Philadelphia.2 Each survey was separately weighted to adjust for sample selection probability, mode of data collection, and nonresponse characteristics (determined by comparison to the minimal demographic information present in the public files). A final survey weight incorporates weights from both surveys. In this paper, we restrict analysis to elected officials who completed both surveys (n = 390) (see Supplementary Appendix B for an illustration of analytic cases resulting from the two surveys).

Dependent Variables

All dependent variables were measured during the second wave (see table 1). We use two binary variables to measure reported personal health behavior, including whether, when away from home, officials reported “staying at least 6 feet from other people” at all times or not and reported “wearing a mask” at all times, or not.3 The first variable measures a personal health behavior that was relatively less symbolically stigmatized and politically contested in early May than masking (Allcott et al. 2020; Bertrand et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Univariate Descriptive Statistics

| Mean | Median | Min | Max | Missing (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables (time 2) | |||||

| Social distancing frequency | 0.72 | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Mask wearing frequency | 0.57 | 0 | 1 | 8 | |

| Institutional reopening scale | 5.19 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 5 |

| Independent variables (time 1) | |||||

| Religious tradition | 17 | ||||

| Evangelical Protestant | 0.17 | ||||

| Mainline Protestant | 0.33 | ||||

| Catholic | 0.26 | ||||

| Non-Christian | 0.04 | ||||

| No affiliation | 0.20 | ||||

| Attendance | 15 | ||||

| Never | 0.27 | ||||

| Monthly or less | 0.28 | ||||

| Few times a month | 0.16 | ||||

| Weekly or more | 0.28 | ||||

| Bible views | 17 | ||||

| Literal Bible | 0.21 | ||||

| Nonliteral Bible | 0.43 | ||||

| All else | 0.36 | ||||

| Religious nationalism scale | 4.65 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 19 |

| Political affiliation | 19 | ||||

| Democrat | 0.40 | ||||

| Other | 0.06 | ||||

| Republican | 0.55 | ||||

| Controls (time 1) | |||||

| Elected (appointed) | 0.70 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Sex (female) | 0.39 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Municipality population (log) | 7.97 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 0 |

| % adults Evangelical (county) | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.50 | 0 |

| % County Republican vote (2016) | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.83 | 0 |

| Education | 1 | ||||

| High school or less | 0.15 | ||||

| Some college | 0.36 | ||||

| College | 0.24 | ||||

| Graduate | 0.26 | ||||

| Age | 0 | ||||

| Less than 45 years old | 0.14 | ||||

| 45–64 years old | 0.41 | ||||

| 65 years old and over | 0.35 | ||||

| Controls (time 2) | |||||

| Know someone with COVID-19 | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | 18 | |

| County COVID-19 cases/10K | 25.38 | 13.81 | 0.24 | 81.55 | 0 |

To measure officials’ attitudes about institutional reopening, we summed respondents’ answers across four questions about when “restrictions on public activity should be lifted in your municipality” (α = .85). Respondents were asked to evaluate four types of institutions: schools, bars and restaurants, houses of worship, and public parks. For each type, respondents reported if institutions should reopen “Immediately,” “Soon,” “Later,” or “Not applicable.” (Respondents with any “not applicable” answers were excluded from analysis.) This variable captures the range of institution-focused public health policies that state leaders had created, which affected all local communities, and which were hotly contested at the time (Bertrand et al. 2020).

Independent Variables: Religious Factors

Measures of religious characteristics were only available from the time one survey. Religious affiliation captured at time one is categorized using a modified religious tradition coding scheme (Steensland et al. 2000). We began with an expansive list of religious affiliations (Protestant/Christian, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Jewish, Muslim, Eastern Orthodox, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, Agnostic, Nothing in Particular, and Something Else). These were recategorized into five intermediary groups: Protestant, Catholic, Atheist/Agnostic, No Affiliation, and Non-Christian. Answers to a follow-up of the “Something Else” category were sorted, with answers like “follower of Christ” and “Baptist” placed in “Protestant,” Polish Catholic placed in “Catholic,” etc. We used respondent answers to a question on born-again experience to split Protestants into Mainline and Evangelical Protestant (Hackett et al. 2018). We combined atheists, agnostics, and Nones into one category. Our final scheme is as follows: Evangelical Protestant, Mainline Protestant (reference), Catholic, Non-Christian, and No Affiliation. The final two categories are admittedly heterogenous, though our theoretical expectations are not primarily based on these categories.

Religious practice is measured with a religious attendance question from time one with the following answer categories: “Never,” “Less than once a month,” “About once a month,” “Two to three times a month,” “About once a week,” “Once a week,” and “More than once a week.” Due to sample size, we collapsed responses into four categories: never attend, attend monthly or less, attend a few times a month, and attend weekly or more.

Religious belief at time one is measured in two ways. First, we use a measure of Bible views with the question, “Which of these statements comes closest to describing your feelings about the Bible?” Answer categories were: “The Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word,” “the Bible is the word of God but not everything in it should be taken literally,” “the Bible is a book written by humans and is not the word of God,” and “I don’t have an opinion about this.” The last two answer categories reflect nonreligious views of scripture and were combined. Second, we created a scale measure of religious nationalism similar to the one used by Whitehead and Perry (2020). Our measure uses one of their questions (“The success of the United States is part of God’s plan”), a question similar to one of theirs (“Prayer should begin all public meetings”), and a third measure (“A person needs to be religious to be a good American”) suggested by other research (Delehanty, Edgell, and Stewart 2019). Each question had answer categories ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with a midpoint of “neither agree nor disagree.” The items were summed together into a scale (α = .76). We refer to our measure as religious nationalism in contrast to Christian nationalism since there is no overtly Christian content.

Independent Variables: Other Factors

We measure local public health threat using the number of confirmed coronavirus cases per 10,000 persons in a county as of May 1st (Dong, Du, and Gardner 2020). We measure local political context with the level of 2016 Republican presidential vote share in an official’s county and local religious context with the percentage of adults in the county who are Evangelical (Grammich et al. 2012).

Control Variables

We control for a number of individual-level demographic characteristics that have been shown to influence behavioral and attitudinal responses to the pandemic (Allcott et al. 2020; Druckman et al. 2020; Evans and Hargittai 2020; Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020b; Shepherd, MacKendrick, and Mora 2020; Smothers, Burge, and Djupe 2020): sex (reference = male), age (reference = 18–44, 45–64, and 65+), and educational level (reference = high school or less, some college, college graduate, and graduate degree). Political affiliation is drawn from Pennsylvania state data files. The primary source was the sampling frame made publicly available by the PDCED, supplemented by state voter registration files. At the individual level, we also control for whether an official is elected (reference) or appointed, and whether they knew a personal contact that had been diagnosed with the coronavirus (reference = do not know such person). We include the population size of the municipality that officials serve using a log of 2010 Census population values (PDCED, 2020b).4

Method

We imputed the relatively small amount of missing data in order to maintain our modest sample size (see last column of table 1).5 All analyses are run on the five imputed datasets generated with Stata’s multiple imputation command. We use binary logistic regression and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression according to dependent variable type.6 Plots indicate statistical significance and relative effect of individual coefficients, presented as log-odds. For ease of comparison to other variables within a model, continuous variables are standardized to range between 0 and 1. For each dependent variable, we present nested coefficient plots. The full model adds religious nationalism which, as we describe below, is related to other variables and was significantly associated with all outcomes.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for variables used in the analysis. While most of Pennsylvania’s frontline officials report religious affiliations, behaviors, and beliefs, one-fifth have no religious affiliation, about a quarter (27%) never attend worship service, and the overwhelming majority (79%) do not view the Bible literally. Regarding actions during the pandemic, though the large majority of local officials were not secluded at home, most reported adopting recommended personal health behaviors at all times when outside the home. Over half reported always wearing a mask (57%) and nearly three-quarters (72%) reported always social distancing when away from home. Local officials also generally supported delayed institutional reopenings. Only 8% supported “immediate” reopening of schools, while 12% supported “immediate” reopening of restaurants, 18% for houses of worship, and 33% for public parks. The picture of local officials is one of overall caution in the face of the pandemic, with pandemic-related health behaviors and attitudes appearing more aligned with public health recommendations than the general public (Bertrand et al. 2020, Shepherd, MacKendrick, and Mora 2020).

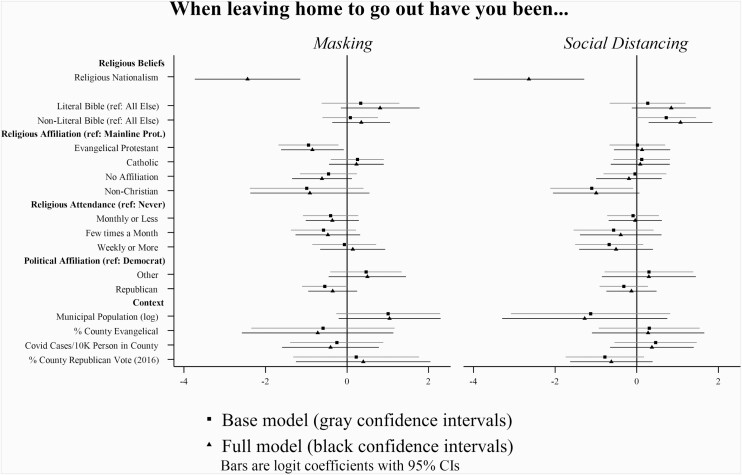

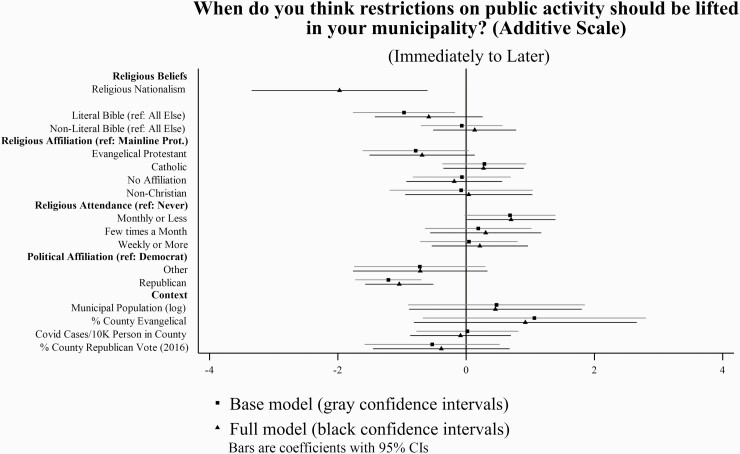

We now turn to examining which factors differentiate the pandemic-related behaviors and attitudes of officials. Figures 1 and 2 show plotted logit coefficients for selected variables with bars displaying 95% confidence intervals, while table 2 shows unstandardized and standardized coefficients for all variables and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Logistic regression results for personal health behaviors.

Figure 2.

OLS regression results for institutional reopening scale.

Table 2:

Logistic Regression Models for Three Dependent Variables

| Mask Wearing | Social Distancing | Institutional Repoening | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | Full | Base | Full | Base | Full | ||||||||||

| b | p | b | p | β | b | p | b | p | β | b | p | b | p | β | |

| Religious nationalism | -2.441 | *** | -0.552 | -2.642 | *** | -0.594 | -1.974 | ** | -0.205 | ||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.006) | |||||||||||||

| Literal belief (all else) | 0.332 | 0.814 | 0.336 | 0.268 | 0.846 | 0.371 | -0.969 | * | -0.583 | -0.101 | |||||

| (0.496) | (0.099) | (0.571) | (0.086) | (0.018) | (0.170) | ||||||||||

| Nonliteral bible (all else) | 0.079 | 0.347 | 0.187 | 0.722 | 1.073 | ** | 0.568 | -0.069 | 0.133 | 0.028 | |||||

| (0.822) | (0.340) | (0.054) | (0.007) | (0.829) | (0.680) | ||||||||||

| Evangelical Protestant (Mainline) | -0.948 | * | -0.851 | * | -0.348 | 0.015 | 0.131 | 0.036 | -0.787 | -0.687 | -0.112 | ||||

| (0.012) | (0.030) | (0.965) | (0.710) | (0.062) | (0.099) | ||||||||||

| Catholic (Mainline) | 0.253 | 0.229 | 0.082 | 0.121 | 0.087 | 0.040 | 0.284 | 0.272 | 0.050 | ||||||

| (0.449) | (0.504) | (0.731) | (0.814) | (0.389) | (0.389) | ||||||||||

| No affiliation (Mainline) | -0.457 | -0.617 | -0.238 | -0.044 | -0.191 | -0.052 | -0.067 | -0.186 | -0.032 | ||||||

| (0.200) | (0.099) | (0.912) | (0.641) | (0.861) | (0.618) | ||||||||||

| Non-Christian (Mainline) | -0.992 | -0.913 | -0.177 | -1.104 | * | -0.993 | -0.190 | -0.078 | 0.041 | 0.003 | |||||

| (0.163) | (0.220) | (0.033) | (0.066) | (0.889) | (0.934) | ||||||||||

| Attend monthly or less (never) | -0.406 | -0.363 | -0.171 | -0.091 | -0.037 | 0.010 | 0.683 | 0.700 | * | 0.134 | |||||

| (0.240) | (0.274) | (0.778) | (0.912) | (0.058) | (0.047) | ||||||||||

| Attend few times a month (never) | -0.580 | -0.472 | -0.157 | -0.567 | -0.392 | -0.136 | 0.189 | 0.305 | 0.048 | ||||||

| (0.154) | (0.243) | (0.257) | (0.442) | (0.649) | (0.482) | ||||||||||

| Attend weekly or more (never) | -0.068 | 0.139 | 0.068 | -0.677 | -0.507 | -0.252 | 0.043 | 0.214 | 0.041 | ||||||

| (0.865) | (0.734) | (0.112) | (0.272) | (0.910) | (0.569) | ||||||||||

| Other (Democrat) | 0.464 | 0.498 | 0.111 | 0.298 | 0.297 | 0.131 | -0.722 | -0.716 | -0.068 | ||||||

| (0.300) | (0.305) | (0.586) | (0.610) | (0.163) | (0.177) | ||||||||||

| Republican (Democrat) | -0.549 | -0.354 | -0.181 | -0.318 | -0.129 | -0.045 | -1.212 | *** | -1.043 | *** | -0.222 | ||||

| (0.053) | (0.248) | (0.293) | (0.680) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| Municipal population (log) | 1.009 | 1.045 | 0.176 | -1.130 | -1.275 | -0.178 | 0.473 | 0.457 | 0.032 | ||||||

| (0.121) | (0.102) | (0.256) | (0.217) | (0.494) | (0.499) | ||||||||||

| % County Evangelical | -0.591 | -0.721 | -0.139 | 0.307 | 0.279 | 0.048 | 1.064 | 0.923 | 0.080 | ||||||

| (0.511) | (0.448) | (0.627) | (0.692) | (0.225) | (0.292) | ||||||||||

| County Covid cases/10K | -0.252 | -0.406 | -0.108 | 0.463 | 0.372 | 0.078 | 0.019 | -0.088 | -0.011 | ||||||

| (0.666) | (0.504) | (0.368) | (0.477) | (0.962) | (0.823) | ||||||||||

| % County Republican vote (2016) | 0.222 | 0.396 | 0.092 | -0.781 | -0.622 | -0.169 | -0.530 | -0.387 | -0.043 | ||||||

| (0.778) | (0.638) | (0.111) | (0.228) | (0.317) | (0.469) | ||||||||||

| Appointed (elected) | -0.310 | -0.193 | -0.100 | 0.176 | 0.320 | 0.074 | 0.230 | 0.344 | 0.066 | ||||||

| (0.302) | (0.535) | (0.575) | (0.331) | (0.379) | (0.178) | ||||||||||

| Female | 0.558 | 0.474 | 0.264 | -0.077 | -0.190 | -0.050 | 0.833 | *** | 0.735 | ** | 0.153 | ||||

| (0.083) | (0.153) | (0.806) | (0.554) | (0.001) | (0.003) | ||||||||||

| Know someone w/Covid | 0.832 | * | 0.985 | * | 0.276 | -0.122 | 0.053 | 0.018 | -0.319 | -0.219 | -0.030 | ||||

| (0.031) | (0.015) | (0.693) | (0.870) | (0.369) | (0.561) | ||||||||||

| Some college (high school) | 1.083 | * | 0.967 | * | 0.480 | 0.948 | ** | 0.830 | ** | 0.401 | 0.129 | -0.021 | -0.004 | ||

| (0.014) | (0.021) | (0.002) | (0.008) | (0.723) | (0.954) | ||||||||||

| College (high school) | 0.992 | * | 0.783 | 0.361 | 1.050 | ** | 0.833 | * | 0.355 | 0.117 | -0.086 | -0.015 | |||

| (0.046) | (0.116) | (0.008) | (0.027) | (0.752) | (0.821) | ||||||||||

| Graduate (high school) | 0.504 | 0.163 | 0.101 | 1.325 | ** | 1.000 | * | 0.449 | 0.922 | * | 0.603 | 0.114 | |||

| (0.229) | (0.711) | (0.002) | (0.026) | (0.014) | (0.120) | ||||||||||

| 45 to 64 years old (less than 45) | 0.711 | * | 0.692 | * | 0.346 | 0.369 | 0.304 | 0.170 | 0.057 | 0.021 | 0.004 | ||||

| (0.028) | (0.049) | (0.229) | (0.302) | (0.870) | (0.949) | ||||||||||

| 65 years old plus (less than 45) | 0.960 | ** | 1.027 | ** | 0.490 | 0.554 | 0.590 | 0.283 | 0.549 | 0.587 | 0.120 | ||||

| (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.250) | (0.198) | (0.123) | (0.069) | ||||||||||

| Constant | -1.112 | -0.411 | 0.567 | 1.414 | 4.721 | *** | 5.366 | *** | |||||||

| (0.159) | (0.613) | (0.513) | (0.144) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||||||||

| N | 390.000 | 390.000 | 390.000 | 390.000 | 346.000 | 346.000 | |||||||||

Notes: All models based on 5 imputed datasets. Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients for continuous varaibles standardized between 0 and 1.

Beta (β) = x-standardized coefficients. *p<.05; *p<.01; *p<.001

In full models, a number of variables other than religion were associated with personal health behavior in ways suggested by previous research on the general public: officials with higher education levels were more likely to report maintaining social distance and the oldest officials were most likely to report wearing masks. Support for institutional reopening among officials appears gendered, with female officials more likely to support delayed reopening. Notably, and in contrast to research on the general public, the political affiliation of frontline officials had no effect on reported personal health behaviors.7 It was, however, related to support for institutional reopening, with Republicans a full unit less supportive of delayed institutional reopening than Democrats (p < .001), even after controlling for religious affiliation, beliefs, and attendance.

We do not find evidence that the local public health threat from COVID-19 or that the local context, measured by county-level Evangelical religion and Republican vote share, influenced frontline officials.8 In other words, professional norms and local context were relatively unimportant. Instead, we find the strongest evidence for personal religious characteristics in shaping the discretionary behavior of frontline officials. For ease of presentation, we analyze each individual religious factor (affiliation, attendance, belief) across outcomes, with reference to full models.

Religious affiliation differentiated one reported personal health behavior as well as attitudes about institutional reopening. In contrast to Evangelical Protestants, officials in both the Mainline Protestant (p < .05) and Catholic (p < .05, reference group contrast not shown) religious traditions were significantly more likely to report always wearing a mask. The odds of a Catholic official reporting always wearing a mask were nearly 200% higher (odds ratio [OR] = 2.9) and the odds of a Mainline Protestant official reporting always wearing a mask 130% higher (OR = 2.3) than for an otherwise similar Evangelical Protestant official. Catholic officials were also significantly more likely than religiously nonaffiliated officials to report wearing a mask (OR = 2.3, p < .05, reference group contrast not shown). Regarding institutional reopening, the only significant religious affiliation difference was between Catholic and Evangelical officials, with the former scoring nearly one point higher on the institutional reopening scale (β = .96, p < .05, reference group contrast not shown), marking support for delayed reopening.9

Worship service attendance did not influence officials’ personal health behaviors. It did influence officials’ attitudes about institutional reopening, but in a surprising way: only officials with a low level of attendance (monthly or less) were more likely to support delayed institutional reopening compared to officials who never attended worship services (β = .70, p < .05).

Scriptural views were only associated with adopting recommended personal health behaviors, not attitudes toward institutional reopening. Those officials with a nonliteral view of the Bible, in contrast to officials with secular views of the Bible, had nearly 200% higher odds (OR = 2.92, p < .01) of reporting social distancing at all times.

Religious nationalism—a measure of officials’ attitudes about the religious character of the country and the role of religion in government—was the only religious variable that was significant across all outcomes. It consistently, negatively influenced personal health behaviors and support for delayed institutional reopening. For a one unit increase on the religious nationalism scale, an official had 20% (OR = 0.80, p < .001) lower odds of reporting always social distancing.10 Similarly, for each unit increase on the religious nationalism scale, an official had about 20% (OR = 0.82, p < .001) lower odds of reporting always wearing a mask. And, for each unit increase on the religious nationalism scale, officials decreased a sixth of a step on the institutional reopening scale (β = −.16, p < .01), moving toward support for immediate reopening.

The visual contrasts of the base and full models in figures 1 and 2 provide a sense of how religious nationalism influences all results.11 When religious nationalism is added in the full model, the positive effect of a nonliteral Bible view on social distancing increases and the negative effect of Evangelical Protestant affiliation on mask wearing is reduced. For the institutional reopening scale, the addition of religious nationalism decreases the negative effect of Evangelical affiliation and increases the positive effect of monthly attendance. And religious nationalism reduces the effect of Republican affiliation in all models. To sum, all religious factors, as well as political affiliation, trend toward cooperative public health behaviors and attitudes once religious nationalism is controlled for in models.

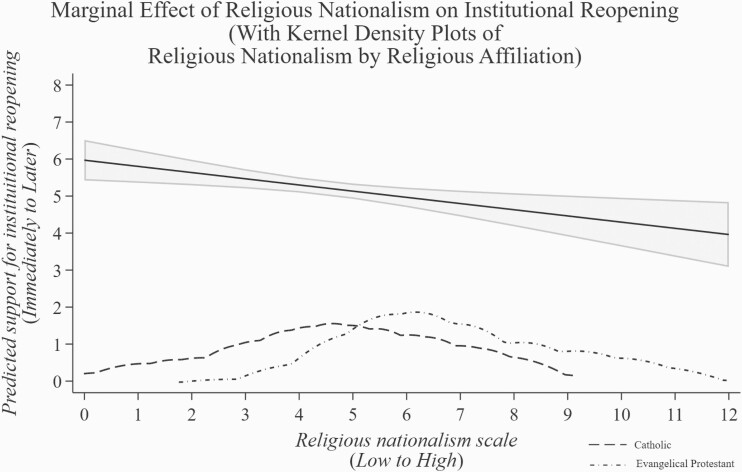

Clearly religious nationalism reflects salient concerns and perspectives that help us better understand officials’ behavior. However, we do not assert the causal priority or conceptual independence of religious nationalism in relation to other variables since the relationships among religious factors, as well as political affiliation, are complex and multidirectional (Lewis 2021; Margolis 2018). Figure 3 helps to demonstrate this, showing the negative effect of increased religious nationalism on support for delayed institutional reopening as all other variables are kept at observed values. At the bottom of the figure, the kernel density plot lines show the distribution of religious nationalism among Catholic and Evangelical Protestant officials. These plot lines reveal that the extent of the effect of religious nationalism is tied to religious affiliation. Catholic officials never display the highest levels of religious nationalism, while Evangelical Protestant never display the lowest. Frontline officials who are Evangelical Protestant are likely more exposed to, and appear more susceptible to, the effects of religious nationalism on their pandemic-related actions and attitudes. (A similar pattern of differential presence of religious nationalism exists across political affiliations, as Republican officials demonstrate higher levels of religious nationalism. See Supplementary Appendix C). These results suggest it is important to consider the reinforcing, conjunctural effects of religious and political factors in order to understand the effect of religious nationalism on frontline officials (Lewis 2021).

Figure 3.

Marginal effect of religious nationalism on institutional reopening (with kernel density plots of religious nationalism by religious affiliation).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Frontline officials have important roles in the local-level fight against the pandemic but have rarely been systematically studied. They are highly visible local leaders whose behaviors and attitudes signal to community members whether and how they should, in turn, live during the pandemic. Our research, which draws on the insights of SLB theory, makes clear that local frontline officials are not homogenous. Further, our research shows that officials’ actions cannot be reduced to their institutional roles or local context alone. Instead, the enactment of governmental action by frontline officials is shaped by discretion connected to their religious affiliations, experiences, and identities. By presenting results from the only longitudinal survey of local officials—and the only survey of frontline officials with extensive information about religion—we have shown how religious characteristics influence both reported public health disease behaviors and attitudes about institutional reopenings during the pandemic. Here, we highlight the main contributions of our research.

First, our results show that, early in the pandemic, most frontline officials reported engaging in recommended personal health behaviors and supporting the delayed reopening of closed institutions. In general, frontline officials were providing visible cues about public health to their constituents during an anxious time. This is a storyline about local government that should not be forgotten in light of the disease-denying mobilizations that have occurred since spring 2020. This is also in line with our expectations, derived from SLB theory, in which frontline officials orient toward public health considerations at greater levels than the general public.

Second, our results show no evidence that the influence of professional public safety norms or local context differentiated officials’ actions. These aspects, which are highlighted by SLB theory as salient, appear relatively unimportant to officials’ actions. This is in contrast with evidence from most studies of frontline officials. It is also in contrast with studies of clergy who balance individual identities with denominational identity, congregational opinion, and local context. We see three potential reasons for this result. First, the large majority of frontline officials serve part-time and for short terms, conditions which may limit their formation in and commitment to role norms. Second, our measures of the local context may have been weak, as they were limited to the county level. Third, the pandemic introduced unique exigencies for officials. In its early months, the pandemic was a threat with unclear resolution. The state governmental response in Pennsylvania was poorly coordinated with local officials (Ortiz, Adler, and Plutzer 2020). Without guidance about a clear resolution, and with growing contestation of public health guidelines by some political and religious groups, frontline officials appear to have been influenced by their identities.

Demographic characteristics of officials, like age, sex, and education, were important, as was political affiliation, but these did not solely or consistently explain the behaviors and attitudes of frontline officials in the pandemic. Indeed, unlike in studies of the general population from the same time period, the political affiliation of frontline officials was unrelated to their reported personal health behaviors. If accurate, this is intriguing evidence that, despite the increasing salience of political identity in American life, frontline officials may experience political affiliation differently, possibly resisting some effects of polarization due to communal accountability, personal identity, or both. Another recent example of this involves local election officials who resisted pressure from their fellow partisans to discount votes in the 2020 election (Gellman 2021).

Our core contribution is that we find religious factors are crucial for understanding variation in frontline officials’ responses to COVID-19. Religious nationalism, which has recently been shown to influence a wide array of behaviors and attitudes, including those related to the pandemic (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020a, 2020b), has a notable effect on frontline officials. In fact, religious nationalism was the only factor that was significantly associated with each of the reported behaviors that we analyzed, and always in a direction that indicated resistance to public health guidance. Frontline officials with strongly religious nationalist views may prefer a particular social order that, paradoxically, prioritizes personal freedom from a government while also embracing the presence of religion in government (Whitehead and Perry 2020). During the pandemic, this aspect of religious nationalism has led to the libertarian rejection of public health guidance among the general public (Perry, Whitehead, and Grubbs 2020a). A similar dynamic appears to exist among frontline officials. We note that our models suggest the importance of viewing religious nationalism as part of a complex relationship among religious factors and political identity (Lewis 2021). To that end, Republican and Evangelical Protestant affiliations are notably associated with religious nationalism, suggesting the organizational bases of religious nationalist belief and confirming the importance of studying formations of politico-religious identity among elected officials (Margolis 2018).

Other religious factors also influenced frontline officials, including in ways not seen among the general population during the pandemic. To simplify, Bible views only influenced officials’ reported personal health behaviors and only differentiated between those with nonliteral views of the Bible against officials with no religious view of the Bible. The expected negative effect of literal Bible views was not observed. Worship attendance only influenced officials’ attitudes about institutional closures and only differentiated those with low levels of worship attendance against those who never attend. The expected positive effect of high attendance on personal health behaviors was not observed. These findings suggest that moderate aspects of religious belief and low levels of religious behavior, in contrast with nonbelief and nonbehavior, influence frontline officials toward behaviors and attitudes in line with public health recommendations. However, as we did not anticipate these findings, we recommend further study to understand whether and how these aspects of religion actually differentiate frontline officials’ actions.

A final important finding concerned religious affiliation, which only influenced officials’ reported masking behaviors and attitudes toward institutional reopenings. Such findings prompt the question as to why adherence to or support of public health recommendations, compared to social distancing behaviors, were influenced by religious affiliation. Religious affiliation appeared to matter for those outcomes (mask wearing, institutional reopening attitudes) that were relatively more politicized in Spring 2020. In both cases, Evangelical Protestant officials were less supportive of public health recommendations while Catholic officials were more supportive. As suggested by other research, Catholic officials may be more accepting of both state-based authority in general and of the scientific knowledge that undergirds public health recommendations during the pandemic (Evans and Hargittai 2020). Further, Catholicism, with its centralized authority structure, was at times quite visible in support for public health recommendations during the pandemic, for example with diocese-wide parish closings or curtailments of in-person services.

Beyond contributing to knowledge of the role of religion in local officials’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic, our research also informs theorizing on how religion may influence government action in general. Research in the Tocquevillian tradition suggests that religion undergirds prosocial action by public officials. Our findings that officials from some religious affiliations were more likely to report wearing masks and support slow reopenings resonates with the Tocquevillian approach to understanding the connection of religion to public life. Also, the findings about moderate Bible views and low levels of attendance point in this direction. However, our findings that officials who belong to the Evangelical Protestant religious tradition and those who hold religious nationalist views were often opposed to mask wearing and institutional closures echo the other research stream reviewed above, suggesting that some religious factors may discourage local officials from collaborative action with state and scientific authorities. A key issue to address regarding religion among frontline officials is how multiple processes coexist, with religion at times influencing governmental action that promotes public goods and at other times not.

Beyond the case of pandemic, we encourage more examination of the individuals that govern on the frontline, instead of just governmental policies. A focus on frontline officials will illuminate how religion–state engagements occur in the form of government that is closest and most visible to Americans. Frontline officials offer a unique window into understanding religion–state relations at a moment when the local level is an important locus for decision-making around controversial social issues. Conflict between religion and governance was a familiar story of some past public health campaigns, like HIV/AIDS prevention, in which disease was refracted through conflicting moral and religious visions (Petro 2015). A similar tension between religion and governance has developed during the COVID-19 pandemic and clearly impacted some local officials. The disaggregated institutional scale, referred to in footnote 9 above, provides evidence that frontline officials’ religious characteristics can work differently by individual institutional domain. Americans’ schematic understanding of the state and how it should relate to other institutions varies across governmental domains (Mayrl and Quinn 2016), and our findings suggest that this understanding may intersect with religious factors in complex ways. It is thus an open question as to how frontline officials’ religion might affect their action on a range of other local issues, such as zoning, addiction treatment, policing, voting, or the placement of public religious symbols (Adler et al. 2020). In these or other domains, officials’ decisions and behavior may be shaped more by professional norms or community context. For these issues, the effects of religion on governance may be reduced or reconfigured given the unique conditions of frontline officials’ work, which includes local visibility and embedded community relationships. Either way, the religion of frontline officials needs to be understood in context, as sometimes leading to conflict and at other times to cooperation with state, legal, or scientific authorities (Adler et al. 2020; Gorski 2017).

In closing, we note a number of limitations of our research. First, there is no national-level study of frontline officials’ religious beliefs, so it is impossible to claim with certainty that our research is representative beyond Pennsylvania. Second, the surveys used in the analyses occurred early in the pandemic. It is possible that some factors may have increased in importance if our research had been done later; for example, political affiliation may have mattered more as the general election season began. It is also possible that a later survey date would have increased the salience of religious characteristics, such as the contrast between religious affiliations or between levels of religious nationalism. Third, our measures of health behaviors are self-reports, not observations of actual practice. Fourth, our measure of political affiliation limited insight into the potential effects of partisanship. Finally, the population of local elected officials in our survey was overwhelmingly white, which prevented analysis of the particular impact of race while raising questions about racial inequality among frontline officials more generally.

While further research is clearly needed, our work does show that understanding religion needs to be a part of how we understand the inner workings of government. Frontline officials are not automatons simply carrying out the rules and policies put into place by other levels of government. Instead, they understand and respond to those policies and practices through their own understandings and beliefs about politics and religion. By examining how these beliefs impacted their response to COVID-19, we begin to see how and why religion is an important mitigating factor to government action, or inaction. How this will play out with other events and other types of government officials remains to be seen, but we now have good reason to believe that religion will likely be a factor.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Isaiah Gerber who wrangled sampling data.

Footnotes

Ninety-seven percent of all responses to the survey were collected by that date.

Philadelphia was excluded because it is the only large city in the state. Responses from its small number of officials would have been difficult to blind and would have affected reliability of estimates, even with an adequate response rate.

Only 2% of officials had not left home at all. These were logically excluded from these two dependent variables.

We do not control for race given that very few officials reported a non-white racial identity. This is due to the fact that the overwhelming majority of municipalities in Pennsylvania, though small, are in predominantly white areas of the state.

Religious tradition was not imputed; all missing were coded as “No affiliation.”

We also examined ordinal logistic regression results for the institutional reopening scale. OLS results are slightly more conservative in terms of p-values, so we report those.

A reviewer noted that, since our measure of political affiliation cannot capture strength of affiliation, this finding may underestimate the role of political affiliation. This is possible. However, officials in a closed-primary state like Pennsylvania appear to be substantially more partisan than the general public and thus have less variation in strength of affiliation, reducing possible bias.

There was also no significant interaction between officials’ religious affiliations and county religiosity or between officials’ political affiliations and county partisanship.

Regression models of the individual dependent variables that make up the institutional reopening scale show that the following factors are significant: religious nationalism (immediate reopening for schools, restaurants, houses of worship), literal Bible views (immediate for houses of worship), Catholic and Mainline religious affiliation (later for parks), monthly religious attendance (later for restaurants, parks), and Republican political affiliation (immediate for schools, restaurants, houses of worship, parks). Our scale reveals patterns across public institutions in general, while these disaggregated results suggest how specific public policy domains relate to individual religious factors differently.

Coefficients reported in this paragraph are from models that use an unstandardized scale of religious nationalism, which helps with comparison to other research.

Since logistic regression coefficients may not be directly comparable across models with additional variables, we used Stata’s khb command, which decomposes effects of variables in nonlinear models, to confirm the adequacy of doing so here.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the 2019 RGK-ARNOVA President’s Award and grants from the Social Science Research Institute and the Population Research Institute at Pennsylvania State University.

REFERENCES

- Adler, Gary, Damon Mayrl, Jonathan S. Coley, and Rebecca Sager. . 2020. “The Frontline of Church–State Relations: Local Officials and the Regulation of Religion in a New Era.” Working Paper Series. RGK Center for Philanthropy and Community Service, Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, University of Texas at Austin. http://churchstaterelations.com/papers/ [Google Scholar]

- Advisory Committee on Public Health . 2013. Public Health Law in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Joint State Government Commission of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, Hunt, Levi Boxell, Jacob Conway, Matthew Gentzkow, Michael Thaler, and David Yang. . 2020. “Polarization and Public Health: Partisan Differences in Social Distancing During the Coronavirus Pandemic.” Journal of Public Economics 191: 104254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Joseph O., Gerardo Martí, Ruth Braunstein, Andrew L. Whitehead, and Grace Yukich. . 2020. “Religion in the Age of Social Distancing: How COVID-19 Presents New Directions for Research.” Sociology of Religion 81(4): 357–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. L., M. A. Potter, D. L. Jones, S. L. Mercer, J. P. Cioffi, L. W. Green, P. K. Halverson, M. Y. Lichtveld, and D. W. Fleming. . 2005. “The Public Health Infrastructure and Our Nation’s Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 26: 303–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banaszak, Lee Ann. 2010. The Women’s Movement Inside and Outside the State. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Daniel. 2017. Defending Faith: The Politics of the Christian Conservative Legal Movement. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, Michael B., Julianna Sandell Pacheco, and Eric Plutzer. . 2008. “Evolution and Creationism in America’s Classrooms: A National Portrait.” PLOS Biology 6(5): e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, Michael, and Eric Plutzer. . 2010. Evolution, Creationism, and the Battle to Control America’s Classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Marriane, Guglielmo Briscese, Maddalena Grignani, and Salma Nassar. . 2020. How COVID-19 Is Changing Americans’ Behaviors, Expectations, and Political Views. Chicago: Becker Friedman Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Blendon, Robert J., John M. Benson, Catherine M. DesRoches, Elizabeth Raleigh, and Kalahn Taylor-Clark. . 2004. “The Public’s Response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Toronto and the United States.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 38(7): 925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski, Adam, Guido Deiana, Valentin Kecht, and David Van Dijcke. . 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic: Government vs. Community Action across the United States.” Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 7: 115–56. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, Barry C. 2007. Personal Roots of Representation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Ernest Q., and Thomas F. Pettigrew. . 1959. “Racial and Moral Crisis: The Role of Little Rock Ministers.” American Journal of Sociology 64(5): 509–16. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Lee, and Caron Chess. . 2008. “Elites and Panic: More to Fear Than Fear Itself.” Social Forces 87(2): 993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Delehanty, Jack, Penny Edgell, and Evan Stewart. . 2019. “Christian America? Secularized Evangelical Discourse and the Boundaries of National Belonging.” Social Forces 97(3): 1283–306. [Google Scholar]

- Demerath, Nicholas Jay III, and Rhys H. Williams. [1992] 2014. A Bridging of Faiths: Religion and Politics in a New England City. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Djupe, Paul A., and Ryan P. Burge. . 2020. “The Prosperity Gospel of Coronavirus Response.” Politics and Religion 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Ensheng, Hongru Du, and Lauren Gardner. . 2020. “An Interactive Web-based Dashboard to Track COVID-19 in Real Time.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20(5): 533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druckman, James N., Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan. . 2020. “How Affective Polarization Shapes Americans’ Political Beliefs: A Study of Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Michael O., Christian Smith, and David Sikkink. . 1999. “Equal in Christ, But Not in the World: White Conservative Protestants and Explanations of Black-White Inequality.” Social Problems 46(1): 398–417. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, John H., and Eszter Hargittai. . 2020. “Who Doesn’t Trust Fauci? The Public’s Belief in the Expertise and Shared Values of Scientists in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Socius 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, Aaron B., and Jenna Griebel. . 2013. “Understanding a Cultural Identity: The Confluence of Education, Politics, and Religion within the American Concept of Biblical Literalism.” Sociology of Religion 74(4): 521–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fullman, Nancy, Bree Bang-Jensen, Grace Reinke, Beatrice Magistro, Rachel Castellano, Megan Erickson, Kenya Amano, John Wilkerson, and Christopher Adolph. . 2020. State-Level Social Distancing Policies in Response to COVID-19 in the U.S. GitHub. https://github.com/COVID19StatePolicy/SocialDistancing. [Google Scholar]

- Gauchat, Gordon. 2015. “The Political Context of Science in the United States: Public Acceptance of Evidence-Based Policy and Science Funding.” Social Forces 94(2): 723–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gellman, Barton. 2021. “America’s Second-Worst Scenario.” The Atlantic, January 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, Philip. 2017. American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sumedha, Thuy D. Nguyen, Felipe Lozano Rojas, Shyam Raman, Byungkyu Lee, Ana Bento, Kosali I. Simon, and Coady Wing. . 2020. “Tracking Public and Private Response to the COVID-19 Epidemic: Evidence from State and Local Government Actions.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series: 27027. [Google Scholar]

- Grammich, Clifford, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley, and Richard H. Taylor. 2012. “2010 U.S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study.” Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Conrad, Philip Schwadel, Gregory A. Smith, Elizabeth Podrebarac Sciupac, and Claire Gecewicz. . 2018. “Choose the Method for Aggregating Religious Identities That Is Most Appropriate for Your Research.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57(4): 807–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, Tim, and Marc J. Ventresca. . 2006. “Inhabited Institutions: Social Interactions and Organizational Forms in Gouldner’s Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy.” Theory & Society 35: 213–36. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, David J., Patricia K. Freeman, and David L. Feldman. . “How Naked Is the Public Square? Religion, Public Service, and Implications for Public Administration.” Public Administration Review 68(3): 428–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Jonathan, and Jared Whalen. . 2019. Pennsylvania, Polarized. Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Inquirer. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, Jennifer L. 2012. Becoming a Candidate: Political Ambition and the Decision to Run for Office. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Andrew R. 2021. “Christian Nationalism and the Remaking of Religion and Politics.” Sociology of Religion 82(1): 111–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lichterman, Paul. 2005. Elusive Togetherness: Church Groups Trying to Bridge America’s Divisions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, Michael. [1980] 2010. Street-Level Bureaucracy, 30th Ann. Ed.: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service. Thousand Oaks, CA: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, Harvey C. 2016. “Tocqueville on Religion and Liberty.” American Political Thought 5(2): 250–76. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, Michele F. 2018. From Politics to the Pews: How Partisanship and the Political Environment Shape Religious Identity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martí, Gerardo. 2020. “White Christian Libertarianism and the Trump Presidency.” In Religion Is Raced: Understanding American Religion in the Twenty-First Century, edited by G. Yukich and P. Edgell, 19–40. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrl, Damon, and Sarah Quinn. . 2016. “Defining the State from Within: Boundaries, Schemas, and Associational Policymaking.” Sociological Theory 34(1): 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mctague, John, and Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz. . 2015. “Thou Shalt Not Flip Flop: Senators’ Religious Affiliations and Issue Position Consistency.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 40(3): 417–40. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Kimberly J., and Ann Shola Orloff. . 2017. The Many Hands of the State: Theorizing Political Authority and Social Control. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Multistate Associates . 2020. COVID-19 State and Local Policy Dashboard. Alexandria, VA: MultiState Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Selena, Gary Adler, Jr., and Eric Plutzer. . 2020. How Pennsylvania’s Municipalities and Local Officials Confront the Coronavirus. University Park: The McCourtney Institute for Democracy, Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Michael Leo. 2008. God and Government in the Ghetto: The Politics of Church–State Collaboration in Black America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (PDCED) . 2020a. Local Government COVID-19 FAQs. Harrisburg, PA. https://dced.pa.gov/local-government-covid-19-faqs/ [Google Scholar]

- ———.2020b. “Municipal Statistics.” https://dced.pa.gov/local-government/municipal-statistics/