ABSTRACT

Background

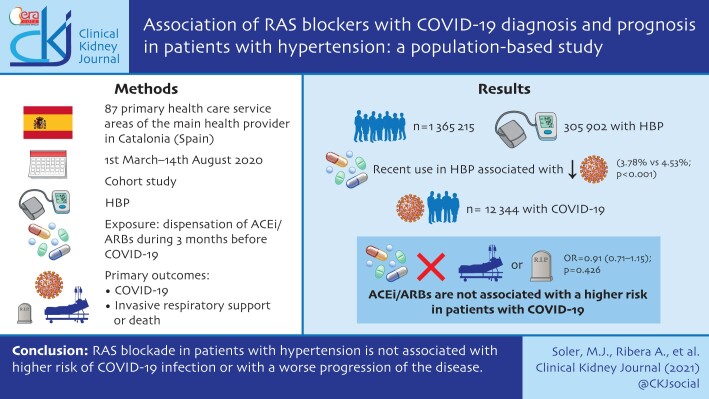

The effect of renin–angiotensin system (RAS) blockade either by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) susceptibility, mortality and severity is inadequately described. We examined the association between RAS blockade and COVID-19 diagnosis and prognosis in a large population-based cohort of patients with hypertension (HTN).

Methods

This is a cohort study using regional health records. We identified all individuals aged 18–95 years from 87 healthcare reference areas of the main health provider in Catalonia (Spain), with a history of HTN from primary care records. Data were linked to COVID-19 test results, hospital, pharmacy and mortality records from 1 March 2020 to 14 August 2020. We defined exposure to RAS blockers as the dispensation of ACEi/ARBs during the 3 months before COVID-19 diagnosis or 1 March 2020. Primary outcomes were: COVID-19 infection and severe progression in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (the composite of need for invasive respiratory support or death). For both outcomes and for each exposure of interest (RAS blockade, ACEi or ARB) we estimated associations in age-, sex-, healthcare area- and propensity score-matched samples.

Results

From a cohort of 1 365 215 inhabitants we identified 305 972 patients with HTN history. Recent use of ACEi/ARBs in patients with HTN was associated with a lower 6-month cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis {3.78% [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.69–3.86%] versus 4.53% (95% CI 4.40–4.65%); P < 0.001}. In the 12 344 patients with COVID-19 infection, the use of ACEi/ARBs was not associated with a higher risk of hospitalization with need for invasive respiratory support or death [OR = 0.91 (0.71–1.15); P = 0.426].

Conclusions

RAS blockade in patients with HTN is not associated with higher risk of COVID-19 infection or with a worse progression of the disease.

Keywords: angiotensin-converting enzyme, angiotensin receptor blockers, COVID-19, hypertension, mortality, renin–angiotensin system blockers

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

There has been a growing interest and speculation regarding the effect of the widely used classes of drugs that inhibit the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) on the novel coronavirus [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)] infection or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity from early 2020 [1]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 is a homolog of ACE, with 40% identity, which was discovered in 2000 [2–4]. Due to its important role as the receptor of SARS-CoV-2, recent studies have been focused on the potential implication of ACE2 in COVID-19 [5–8]. Prior data suggested that RAS blockade with ACE inhibitors (ACEis) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) may increase ACE2 expression or activity, though these data are mixed. Accordingly, during the last several months, various observational studies and clinical trials have been designed and conducted to address the effect of RAS blockade on COVID-19 severity [9–13].

Most studies that have evaluated the association between RAS blockade and the risk of development and severity of COVID-19 suggest a neutral effect of this therapy [14–16]. Yet, to assess the association between RAS blockade and the risk of diagnosis of COVID-19, the majority of published studies have a used case–control design [14–16]. This design could bias to some extent risk estimates, especially if COVID-19 cases requiring hospitalization are overrepresented [11, 17]. Furthermore, to assess whether ACEi or ARBs are associated with worse outcomes in COVID-19-infected patients, most of the published studies included exclusively hospitalized patients, which constitutes a highly selected population, especially during the massive blow of pandemic [18–21]. This is especially true for subpopulations with high cardiovascular risk profiles.

To overcome potential selection bias in this context, the ideal approach would be to use a closed community population-based cohort. In this sense, although there are several cohort studies that have been carried out in different populations, all of them have selected the final study population in ways that could limit the generalizability of their findings [12, 16, 20]. In this study, we used a large, unselected community cohort of 305 972 patients with a history of hypertension (HTN) to assess whether chronic treatment with RAS inhibitors (RASis) is associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 diagnosis or with worse outcomes in infected patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and data sources

We performed a cohort study using prospectively collected data stored in the Information Systems of the Institut Català de la Salut (ICS) in Catalonia, Spain. ICS is the main health provider of the Catalan health system, providing primary care to a representative >6.7 million people (>88% of the population in Catalonia), and hospital care to 1.5 million.

The cohort data were obtained from primary-care electronic health records (ECAP). ECAP contains high-quality validated diagnoses [International Classification for Diseases, 10th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM)], pharmacy dispenses and socio-demographic information. ECAP data have been previously validated [22] and used for COVID-19 research [23]. Registries of people with a diagnostic code related to HTN were linked to the official repository of reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2, to hospital admissions, intensive care units (ICUs) and mortality registries.

The Vall d’Hebron Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, including a waiver for the informed consent of patients taking part in the study, and the data extracted were fully anonymized. The data underlying this article were provided by ICS by permission. Data will be shared on request to the corresponding author with permission of ICS.

Study participants and follow-up

We included all individuals in all healthcare areas with primary and hospital care provided by ICS, aged ≥18 and <95 years with a diagnosis of HTN up to 1 March 2020.

For the first main study objective, the association of RASis use with risk of COVID-19 diagnosis, participants were followed from 1 March 2020 to the earliest of a first positive RT-PCR test or clinical diagnosis or death or the end of the study period (14 August 2020). COVID-19 was identified by a positive RT-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 (confirmed cases) and/or a clinical diagnosis (probable cases) recorded in primary care or hospital diagnoses, or in death certificates. ICD-10-CM codes used are listed in Supplementary data, Table S1.

For the second main study objective, the association of RASis use with risk of worse outcomes among infected patients, patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 were followed from the earliest COVID-19 diagnosis (confirmed or probable) until death or the end of the study period (14 August 2020). The merged data allowed us to assess different key events throughout the progression of COVID-19: hospitalization, admission to the ICU, need for respiratory support, need for invasive haemodynamic support and COVID-19 mortality. Our primary endpoint for this second objective was need for invasive organ/respiratory support or COVID-19 mortality (see the combinations of ICD-10 CM procedure codes for the need for invasive respiratory support).

Baseline characteristics and comorbidities

We assessed baseline characteristics and comorbidities on 1 March 2020, including: sex, age (in years), rurality (rural, urban), socio-economic status [MEDEA (‘Mortalidad en áreas pequeñas Españolas y Desigualdades Socioeconómicas y Ambientales’) deprivation index] and pre-existing comorbidities. Rural areas were defined as areas with <10 000 inhabitants and a population density ˂150 inhabitants/km2. The validated MEDEA deprivation index is calculated by census tract level in urban areas, categorized in quartiles, where the first and fourth quartiles are the least and most deprived areas, respectively [24]. Comorbidities were defined as the presence of a diagnosis code recorded any time before the index date and still active on 1 March for a pre-specified list of conditions. Lists of ICD-10-CM codes for each of these conditions are provided in Supplementary data, Table S2.

Drug exposure

We identified major classes of antihypertensive agents (ACEis, ARBs, calcium-channel blockers, diuretics and β-blockers) that were dispensed to patients in the 3 months prior to the date of COVID infection, or 1 March 2020 in the non-infected [see the list of ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System) codes of included pharmacy products in Supplementary data, Table S3]. We also identified other drugs including lipid-lowering agents, oral antidiabetic agents, insulin, antiplatelet agents, antiarrhythmic agents, anticoagulant agents, digitalis, nitrates, inhaled glucocorticoids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immunosuppressive agents, short-acting β-agonists, long-acting β-agonists and other agents used for chronic respiratory diseases. The exposure of interest was defined as the dispensation of ACEis or ARBs at least once during the 3 months before COVID-19 diagnosis or before the start of the first pandemic wave (1 March 2020). Patients with dispensation of both agents represented only 0.4% (n = 1532) of the cohort and were excluded.

Statistical analysis

We report descriptive statistics including means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for binary and categorical variables. Differences in means were assessed using the Student’s t-test and differences in percentages were assessed using the chi-square test.

The association between use of RASis and risk of COVID-19 diagnosis was assessed using mixed effects Cox regression analysis, and the association between the use of RASis and outcomes in infected patients was assessed using mixed effects logistic models. We used random slope models and a non-structured covariance matrix for random effects. In both analyses, we adjusted for the effect of clustered structure of data among patients cared for by different health providers located in different geographic locations (i.e. healthcare areas; n = 89) that might differ in socio-economic status and in the level of exposure to the virus. We also adjusted all analyses by the estimated prevalence of COVID-19 at each healthcare area as an indicator of COVID-19 impact in the area or a surrogate marker of the probability of each individual living in each area to be exposed to the virus.

To minimize confounding, all comparisons performed were matched by age, sex, healthcare area and the propensity score for the corresponding exposure. Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression and they included the variables age, gender, MEDEA deprivation index, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD) history (i.e. myocardial infarction, angina, stroke, heart failure and peripheral vascular disease), asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) history, dementia, hypercholesterolaemia, atrial fibrillation, cancer, renal impairment, obesity [diagnosis or body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2] and the dispensed medications. Each patient with the exposure of interest was 1:1 matched without replacement to the non-treated patient of the same age, sex and healthcare area with the lowest propensity score difference. Balance in patient characteristics between exposure groups in matched data was assessed using standardized differences (Supplementary data, Tables S4–S6). Outcomes between matched cohorts were compared with conditional logistic regression models. We performed further analyses within the matched cohorts to adjust for those variables with standardized differences >10%. All analyses were performed using the statistical package RStudio.

RESULTS

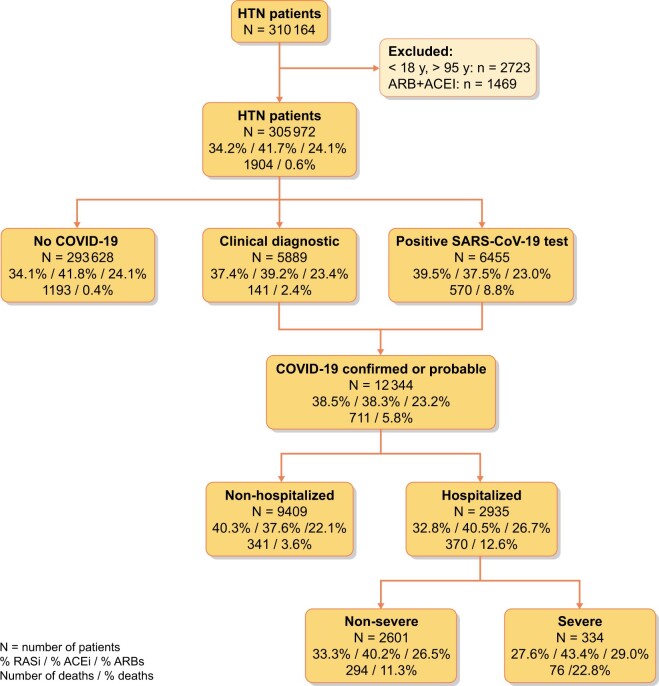

From a reference population of 1 365 215 inhabitants, ≥18 years old, living in areas with both primary and hospital care delivered by ICS centres (a total of 87 health areas), we identified 305 972 patients with HTN (Figure 1). Among these, 201 131 (66%) were dispensed RAAS inhibitor (RAASi) therapy during the 3 months prior to the initial pandemic wave: 127 532 (41.6%) were on an ACEi and 73 599 (24%) were on an ARB. The cumulative incidence of COVID-19 infection during the first 6 months of the pandemic in this population was 4.03% [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.96–4.10].

FIGURE 1:

Flow chart. The values in boxes represent: percentage of patients on RASis/percentage of patients on ACEi/percentage of patients on ARBs/number of deaths/percentage of patients dying.

RASis therapy and the risk of COVID-19 diagnosis

Table 1 shows the baseline differences between RASi users versus non-users and, within the RASis group, between ACEi and ARB users. Compared with non-users, RASi users were older, mostly male, with higher deprivation indexes, higher prevalence of obesity, HTN and hypercholesterolaemia, and lower prevalence of diabetes. Other comorbidities were in general also more common in patients on RASis, although stroke history and dementia were less frequent in these patients. Similarly, RASis users were prescribed more other drugs on average (mean total number of other drugs 2.16 ± 1.87 versus 1.55 ± 1.8, P < 0.001), except for NSAIDs. Patients in both groups lived in healthcare areas with a fairly similar COVID-19 impact, although with a trend of higher cumulative incidence in the group of patients on RASis. Differences were smaller when comparing ACEi with ARB users, although the latter tended to have a higher prevalence of baseline risk factors, comorbidities and concomitant therapies. The cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis at 6 months (Table 2) was lower in RASi users compared with non-users [3.8% (95% CI 3.7–3.8%) versus 4.53% (95% CI 4.4–4.7%); P < 0.001]. Within the RASis group, cumulative incidence was slightly higher in patients on ARBs [3.9% (95% CI 3.8–4.0%)] than in those on ACEis [3.7% (95% CI 3.6–3.8%); P = 0.036].

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics by RASi, ACEi or ARB use

| Global (n = 305 972) | RASi use |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 104 841) | Yes |

P-value (ACEi versus ARB) | P-value (RAS versus no RAS) | ||||

| All (n = 201 131) | ACEi users (n = 127 532) | ARB users (n = 73 599) | |||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 68.86 ± 13.41 | 67.1 ± 15.01 | 69.77 ± 12.4 | 68.8 ± 12.68 | 71.46 ± 11.71 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 157 070 (51.3) | 56 093 (53.5) | 100 977 (50.2) | 61 086 (47.9) | 39 891 (54.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MEDEA deprivation index, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| NA | 908 (0.3) | 423 (0.4) | 485 (0.2) | 274 (0.2) | 211 (0.3) | – | – |

| 0 Rural | 16 245 (5.3) | 5596 (5.3) | 10 649 (5.3) | 6826 (5.4) | 3823 (5.2) | – | – |

| 1 Rural | 28 718 (9.4) | 9749 (9.3) | 18 969 (9.4) | 12 481 (9.8) | 6488 (8.8) | – | – |

| 2 Rural | 45 262 (14.8) | 15 961 (15.2) | 29 301 (14.6) | 17 435 (13.7) | 11 866 (16.1) | – | – |

| 1 Urban | 41 266 (13.5) | 14 295 (13.6) | 26 971 (13.4) | 17 269 (13.5) | 9702 (13.2) | – | – |

| 2 Urban | 43 619 (14.3) | 15 157 (14.5) | 28 462 (14.2) | 17 628 (13.8) | 10 834 (14.7) | – | – |

| 3 Urban | 77 321 (25.3) | 26 400 (25.2) | 50 921 (25.3) | 32 047 (25.1) | 18 874 (25.6) | – | – |

| 4 Urban | 52 633 (17.2) | 17 260 (16.5) | 35 373 (17.6) | 23 572 (18.5) | 11 801 (16) | – | – |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 173 103 (56.6) | 62 345 (59.5) | 110 758 (55.1) | 67 279 (52.8) | 43 479 (59.1) | – | – |

| Yes | 43 139 (14.1) | 15 915 (15.2) | 27 224 (13.5) | 19 644 (15.4) | 7580 (10.3) | – | – |

| Former | 89 730 (29.3) | 26 581 (25.4) | 63 149 (31.4) | 40 609 (31.8) | 22 540 (30.6) | – | – |

| Obesity, n (%) | 145 438 (47.5) | 43 744 (41.7) | 101 694 (50.6) | 62 439 (49) | 39 255 (53.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 85 156 (27.8) | 26 953 (25.7) | 58 203 (28.9) | 36 773 (28.8) | 21 430 (29.1) | 0.179 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 86 157 (28.2) | 22 914 (21.9) | 63 243 (31.4) | 38 187 (29.9) | 25 056 (34) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 28 792 (9.4) | 9117 (8.7) | 19 675 (9.8) | 10 716 (8.4) | 8959 (12.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 57 601 (18.8) | 17 109 (16.3) | 40 492 (20.1) | 23 639 (18.5) | 16 853 (22.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 9794 (3.2) | 2785 (2.7) | 7009 (3.5) | 4362 (3.4) | 2647 (3.6) | 0.039 | <0.001 |

| Angina, n (%) | 9102 (3) | 2857 (2.7) | 6245 (3.1) | 3442 (2.7) | 2803 (3.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 16 370 (5.4) | 4968 (4.7) | 11 402 (5.7) | 6961 (5.5) | 4441 (6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 16 126 (5.3) | 5162 (4.9) | 10 964 (5.5) | 5755 (4.5) | 5209 (7.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 11 483 (3.8) | 3326 (3.2) | 8157 (4.1) | 4889 (3.8) | 3268 (4.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 86 370 (28.2) | 27 332 (26.1) | 59 038 (29.4) | 34 999 (27.4) | 24 039 (32.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 8555 (2.8) | 3729 (3.6) | 4826 (2.4) | 3053 (2.4) | 1773 (2.4) | 0.843 | <0.001 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 3117 (1) | 1116 (1.1) | 2001 (1) | 1186 (0.9) | 815 (1.1) | <0.001 | 0.072 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 46 867 (15.3) | 14 724 (14) | 32 143 (16) | 17 760 (13.9) | 14 383 (19.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Recent concomitant drug therapy | |||||||

| Number of concomitant agents, mean ± SD | 1.95 ± 1.87 | 1.55 ± 1.8 | 2.16 ± 1.87 | 2 ± 1.79 | 2.45 ± 1.97 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 0–1, n (%) | 150 551 (49.2) | 62 431 (59.5) | 88 120 (43.8) | 60 361 (47.3) | 27 759 (37.7) | – | – |

| 2–4, n (%) | 123 495 (40.4) | 34 283 (32.7) | 89 212 (44.4) | 54 606 (42.8) | 34 606 (47) | – | – |

| >4, n (%) | 31 926 (10.4) | 8127 (7.8) | 23 799 (11.8) | 12 565 (9.9) | 11 234 (15.3) | – | – |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 60 984 (19.9) | 17 124 (16.3) | 43 860 (21.8) | 24 744 (19.4) | 19 116 (26) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Thiazides, n (%) | 30 711 (10) | 13 176 (12.6) | 17 535 (8.7) | 11 701 (9.2) | 5834 (7.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 29 116 (9.5) | 9083 (8.7) | 20 033 (10) | 10 631 (8.3) | 9402 (12.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| β-blockers, n (%) | 62 900 (20.6) | 20 452 (19.5) | 42 448 (21.1) | 23 687 (18.6) | 18 761 (25.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering agents, n (%) | 112 910 (36.9) | 25 649 (24.5) | 87 261 (43.4) | 52 691 (41.3) | 34 570 (47) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agents, n (%) | 57 127 (18.7) | 13 056 (12.5) | 44 071 (21.9) | 26 028 (20.4) | 18 043 (24.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonists, n (%) | 15 381 (5) | 4098 (3.9) | 11 283 (5.6) | 6383 (5) | 4900 (6.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 11 278 (3.7) | 3038 (2.9) | 8240 (4.1) | 4325 (3.4) | 3915 (5.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Digital, n (%) | 2895 (0.9) | 822 (0.8) | 2073 (1) | 1155 (0.9) | 918 (1.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 8713 (2.8) | 2649 (2.5) | 6064 (3) | 3297 (2.6) | 2767 (3.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 18 528 (6.1) | 4085 (3.9) | 14 443 (7.2) | 7954 (6.2) | 6489 (8.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Oral antidiabetic agents, n (%) | 63 803 (20.9) | 12 872 (12.3) | 50 931 (25.3) | 30 789 (24.1) | 20 142 (27.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppressive agents, n (%) | 18 278 (6) | 5826 (5.6) | 12 452 (6.2) | 7202 (5.6) | 5250 (7.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 32 521 (10.6) | 10 548 (10.1) | 21 973 (10.9) | 14 459 (11.3) | 7514 (10.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Long-action β-adrenergic agents, n (%) | 24 126 (7.9) | 6545 (6.2) | 17 581 (8.7) | 9960 (7.8) | 7621 (10.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Short-action β-adrenergic agents, n (%) | 12 078 (3.9) | 3438 (3.3) | 8640 (4.3) | 5278 (4.1) | 3362 (4.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Steroid agents, n (%) | 7088 (2.3) | 2115 (2) | 4973 (2.5) | 2852 (2.2) | 2121 (2.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 infection, n (%) | 12 344 (4) | 4746 (4.5) | 7598 (3.8) | 4731 (3.7) | 2867 (3.9) | 0.036 | <0.001 |

| Impact of COVID-19 infection in the corresponding healthcare areas (n = 87) | |||||||

| Mean prevalence in the corresponding census area, mean ± SD | 4.19 ± 1.77 | 4.19 ± 1.79 | 4.19 ± 1.76 | 4.21 ± 1.78 | 4.14 ± 1.73 | <0.001 | 0.859 |

| Terciles of prevalence, n (%) | |||||||

| <3.3 | 101 633 (33.2) | 35 153 (33.5) | 66 480 (33.1) | 41 233 (32.3) | 25 247 (34.3) | – | – |

| 3.3–4.7 | 102 272 (33.4) | 34 251 (32.7) | 68 021 (33.8) | 43 281 (33.9) | 24 740 (33.6) | – | – |

| >4.7 | 102 067 (33.4) | 35 437 (33.8) | 66 630 (33.1) | 43 018 (33.7) | 23 612 (32.1) | – | – |

NA, not available.

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis and incidence of main outcomes in the COVID-19 infected, in the whole study sample and in the age-, sex-, area- and propensity score-matched samples

| All sample % incidence (95% CI) | Matched sample % incidence (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence of COVID-19 infection | ||

| Non-users | 4.5 (4.4–4.6) | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) |

| ACEi users | 3.7 (3.6–3.8) | 1.7 (1.6–1.8) |

| ARB users | 3.9 (3.8–4.0) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) |

| COVID-19-infected patients | ||

| Hospitalization | ||

| Non-users | 20.2 (19.1–21.3) | 20.5 (18.7–22.3) |

| ACEi users | 25.2 (22.7–27.7) | 21.9 (19.6–24.2) |

| ARB users | 27.4 (24.3–20.5) | 23.8 (20.7–26.9) |

| Severe episode | ||

| Non-users | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 1.9 (1.3–2.5) |

| ACEi users | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) | 2.0 (1.2–2.8) |

| ARB users | 3.4 (2.7–4.1) | 3.0 (1.8–4.2) |

| Death | ||

| Non-users | 7.2 (6.5–7.9) | 6.5 (5.4–7.6) |

| ACEi users | 4.4 (3.8–5.0) | 4.4 (3.3–5.5) |

| ARB users | 5.5 (4.7–6.3) | 7.0 (5.1–8.9) |

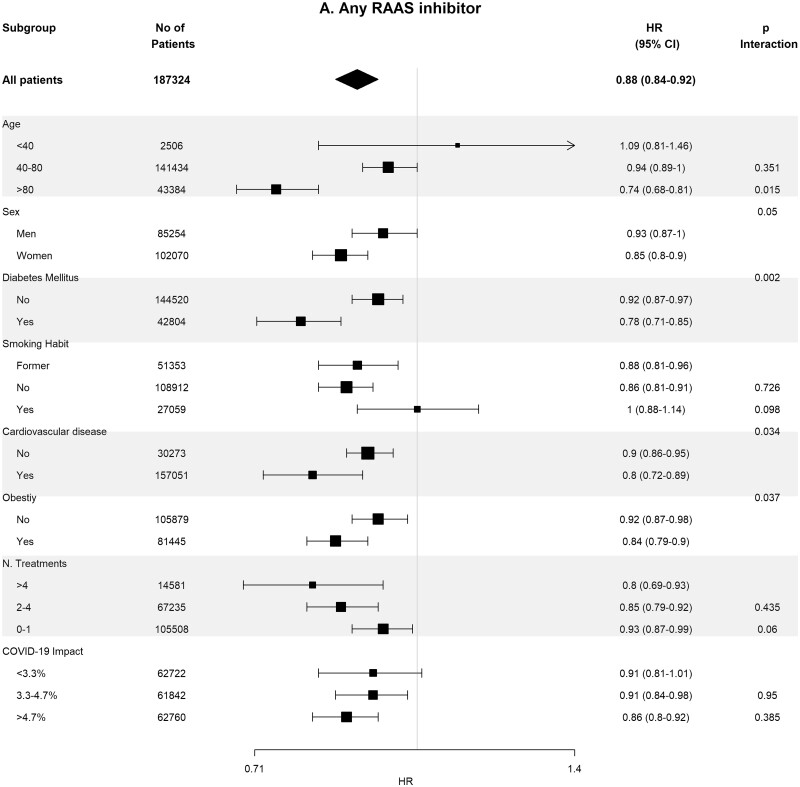

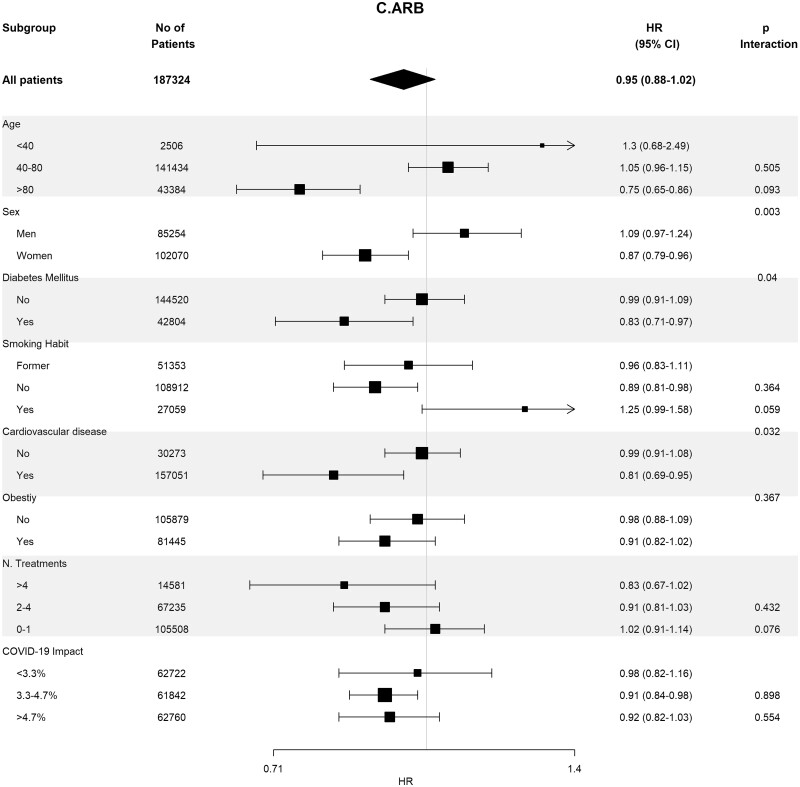

Baseline covariates between RASi users versus non-users were well-balanced in 93 662 pairs of age-, sex-, area- and propensity score-matched patients (Supplementary data, Table S4). In these matched cohorts, cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis (Table 2) was lower in RASi users versus non-users [3.9% (95% CI 3.8–4.0%) versus 4.4% (95% CI 4.3–4.5%); P = 0.016]. In the matched pairs of ACEi users versus non-users (n = 60 964 pairs) and ARB users versus non-users (n = 32 698 pairs), covariates were also well balanced (Supplementary data, Tables S5 and S6). In these matched cohorts, cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis (Table 2) was also lower in those patients on ACEis and in those patients on ARBs comparing their respective non-user pairs: 1.7% (95% CI 1.6–1.8%) versus 1.8% (95% CI 1.7–1.9%) (P ≤ 0.011) in the ACEi cohort and 2.2% (95% CI 2.0–2.4%) versus 2.6% (95% CI 2.4–2.7%) (P = 0.023) in the ARBs cohort. Figure 2 shows the subgroup analyses for each therapy stratified by age, sex, diabetes, HTN, CVD, obesity, number of concomitant treatments and the COVID-19 impact in the corresponding healthcare areas. Association of RASis with a lower cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis was consistent across the different subgroups.

FIGURE 2:

Association of recent use of RAASi (A), ACEi (B) or ARB (C) users versus non-users with the risk of COVID-19 infection, stratified by different variables. Estimates are presented for the age-, sex- and propensity score-matched samples. N. Treatments, number of concomitant pharmacological treatments; COVID-19 impact, estimated prevalence of COVID-19 at the corresponding healthcare area.

RAASis and prognosis in patients infected with COVID-19

Table 3 shows the baseline differences in the 12 344 COVID-19-infected patients between RASi users (n = 7598) and non-users (n = 4746) and, within the RASi group, between ACEi (n = 4731) and ARB (n = 2867) users. In general, differences observed in the whole study population were also reproducible in infected patients, although without statistically significant differences in angina, cancer and concomitant treatment with digitalis, loop diuretics, vitamin K, nitrates and steroids. As in the whole population group, differences between ACEi and ARBs users were smaller. Table 2 shows the cumulative incidence of main outcomes according to RASis therapy. Hospitalization rates, need for intensive care and the need for invasive respiratory support were higher in RASis users versus non-users. In contrast, the death rate was lower in RASi users [4.8% (95% CI 4.4–5.3%) versus 7.2% (95% CI 6.5–8.0%); P < 0.001]. The same pattern was observed in the composite endpoint of death or need for invasive respiratory support in RASi users [7.3% (95% CI 6.7–7.90)] versus in non-users [8.7% (95% CI 7.9–9.5%); P = 0.006]. Within the RASi group, higher rate of hospitalization, death and in the composite endpoint death or need for invasive respiratory support was observed in patients on ARBs compared with patients on ACEis.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of patients with COVID-19 diagnosis by RASi, ACEi or ARB use

| Global (n = 12 344) | RASi use |

P-value (ACEi versus ARB) | P-value (RAS versus no RAS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 4746) | Yes |

||||||

| All (n = 7598) | ACEi (n = 4731) | ARB (n = 2867) | |||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 68.22 ± 15.31 | 67.83 ± 16.95 | 68.47 ± 14.19 | 67.42 ± 14.67 | 70.21 ± 13.16 | <0.001 | 0.028 |

| Female, n (%) | 6829 (55.3) | 2786 (58.7) | 4043 (53.2) | 2439 (51.6) | 1604 (55.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MEDEA deprivation index, n (%) | 0.026 | 0.108 | |||||

| NA | 47 (0.4) | 16 (0.3) | 31 (0.4) | 20 (0.4) | 11 (0.4) | – | – |

| 0 Rural | 513 (4.2) | 210 (4.4) | 303 (4) | 174 (3.7) | 129 (4.5) | – | – |

| 1 Rural | 1181 (9.6) | 432 (9.1) | 749 (9.9) | 496 (10.5) | 253 (8.8) | – | – |

| 2 Rural | 1600 (13) | 625 (13.2) | 975 (12.8) | 613 (13) | 362 (12.6) | – | – |

| 1 Urban | 1097 (8.9) | 451 (9.5) | 646 (8.5) | 403 (8.5) | 243 (8.5) | – | – |

| 2 Urban | 2184 (17.7) | 857 (18.1) | 1327 (17.5) | 823 (17.4) | 504 (17.6) | – | – |

| 3 Urban | 3421 (27.7) | 1318 (27.8) | 2103 (27.7) | 1260 (26.6) | 843 (29.4) | – | – |

| 4 Urban | 2301 (18.6) | 837 (17.6) | 1464 (19.3) | 942 (19.9) | 522 (18.2) | – | – |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| No | 7184 (58.2) | 2908 (61.3) | 4276 (56.3) | 2601 (55) | 1675 (58.4) | – | – |

| Yes | 1492 (12.1) | 595 (12.5) | 897 (11.8) | 605 (12.8) | 292 (10.2) | – | – |

| Former | 3668 (29.7) | 1243 (26.2) | 2425 (31.9) | 1525 (32.2) | 900 (31.4) | – | – |

| Obesity, n (%) | 5949 (48.2) | 2081 (43.8) | 3868 (50.9) | 2334 (49.3) | 1534 (53.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 3490 (28.3) | 1265 (26.7) | 2225 (29.3) | 1354 (28.6) | 871 (30.4) | 0.108 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3498 (28.3) | 1147 (24.2) | 2351 (30.9) | 1400 (29.6) | 951 (33.2) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 1365 (11.1) | 550 (11.6) | 815 (10.7) | 454 (9.6) | 361 (12.6) | <0.001 | 0.145 |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 2702 (21.9) | 977 (20.6) | 1725 (22.7) | 994 (21) | 731 (25.5) | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 435 (3.5) | 144 (3) | 291 (3.8) | 172 (3.6) | 119 (4.2) | 0.284 | 0.022 |

| Angina, n (%) | 411 (3.3) | 141 (3) | 270 (3.6) | 146 (3.1) | 124 (4.3) | 0.006 | 0.088 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 932 (7.6) | 356 (7.5) | 576 (7.6) | 347 (7.3) | 229 (8) | 0.319 | 0.898 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 879 (7.1) | 359 (7.6) | 520 (6.8) | 266 (5.6) | 254 (8.9) | <0.001 | 0.139 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 488 (4) | 165 (3.5) | 323 (4.3) | 192 (4.1) | 131 (4.6) | 0.312 | 0.036 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 4132 (33.5) | 1491 (31.4) | 2641 (34.8) | 1575 (33.3) | 1066 (37.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Dementia, n (%) | 841 (6.8) | 424 (8.9) | 417 (5.5) | 274 (5.8) | 143 (5) | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 141 (1.1) | 54 (1.1) | 87 (1.1) | 45 (1) | 42 (1.5) | 0.054 | 1 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 2084 (16.9) | 875 (18.4) | 1209 (15.9) | 645 (13.6) | 564 (19.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Concomitant drug therapy during prior 3 months | |||||||

| Number of concomitant agents, mean ± SD | 2.12 ± 1.99 | 1.76 ± 1.94 | 2.34 ± 1.98 | 2.18 ± 1.91 | 2.61 ± 2.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 0–1, n (%) | 5767 (46.7) | 2642 (55.7) | 3125 (41.1) | 2094 (44.3) | 1031 (36) | – | – |

| 2–4, n (%) | 5006 (40.6) | 1631 (34.4) | 3375 (44.4) | 2057 (43.5) | 1318 (46) | – | – |

| >4, n (%) | 1571 (12.7) | 473 (10) | 1098 (14.5) | 580 (12.3) | 518 (18.1) | – | – |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 2482 (20.1) | 739 (15.6) | 1743 (22.9) | 954 (20.2) | 789 (27.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Thiazides, n (%) | 1229 (10) | 560 (11.8) | 669 (8.8) | 436 (9.2) | 233 (8.1) | 0.114 | <0.001 |

| Loop diuretics, n (%) | 1723 (14) | 659 (13.9) | 1064 (14) | 560 (11.8) | 504 (17.6) | <0.001 | 0.875 |

| β-blockers, n (%) | 2487 (20.1) | 907 (19.1) | 1580 (20.8) | 875 (18.5) | 705 (24.6) | <0.001 | 0.025 |

| Lipid-lowering agents, n (%) | 3901 (31.6) | 974 (20.5) | 2927 (38.5) | 1716 (36.3) | 1211 (42.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agents, n (%) | 2451 (19.9) | 715 (15.1) | 1736 (22.8) | 1012 (21.4) | 724 (25.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin K antagonists, n (%) | 602 (4.9) | 212 (4.5) | 390 (5.1) | 220 (4.7) | 170 (5.9) | 0.017 | 0.103 |

| Direct oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 599 (4.9) | 215 (4.5) | 384 (5.1) | 195 (4.1) | 189 (6.6) | <0.001 | 0.202 |

| Digital, n (%) | 124 (1) | 52 (1.1) | 72 (0.9) | 41 (0.9) | 31 (1.1) | 0.416 | 0.478 |

| Nitrates, n (%) | 428 (3.5) | 147 (3.1) | 281 (3.7) | 146 (3.1) | 135 (4.7) | <0.001 | 0.085 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 862 (7) | 257 (5.4) | 605 (8) | 338 (7.1) | 267 (9.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Oral antidiabetic agents, n (%) | 2330 (18.9) | 562 (11.8) | 1768 (23.3) | 1057 (22.3) | 711 (24.8) | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Immunosuppressive agents, n (%) | 1140 (9.2) | 404 (8.5) | 736 (9.7) | 433 (9.2) | 303 (10.6) | 0.047 | 0.031 |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 1331 (10.8) | 440 (9.3) | 891 (11.7) | 613 (13) | 278 (9.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Long-action β-adrenergic agents, n (%) | 1291 (10.5) | 421 (8.9) | 870 (11.5) | 496 (10.5) | 374 (13) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Short-action β-adrenergic agents, n (%) | 801 (6.5) | 264 (5.6) | 537 (7.1) | 347 (7.3) | 190 (6.6) | 0.263 | 0.001 |

| Steroid agents, n (%) | 444 (3.6) | 159 (3.4) | 285 (3.8) | 155 (3.3) | 130 (4.5) | 0.006 | 0.265 |

| Impact of COVID-19 infection in the corresponding healthcare areas (n = 87) | |||||||

| Mean prevalence in the corresponding area, mean ± SD | 4.94 ± 1.82 | 4.97 ± 1.8 | 4.93 ± 1.84 | 4.98 ± 1.87 | 4.84 ± 1.78 | 0.001 | 0.267 |

| Terciles of prevalence, n (%) | |||||||

| <3.3 | 2233 (18.1) | 840 (17.7) | 1393 (18.3) | 833 (17.6) | 560 (19.5) | 0.008 | 0.051 |

| 3.3–4.7 | 4172 (33.8) | 1557 (32.8) | 2615 (34.4) | 1600 (33.8) | 1015 (35.4) | – | – |

| >4.7 | 5939 (48.1) | 2349 (49.5) | 3590 (47.2) | 2298 (48.6) | 1292 (45.1) | – | – |

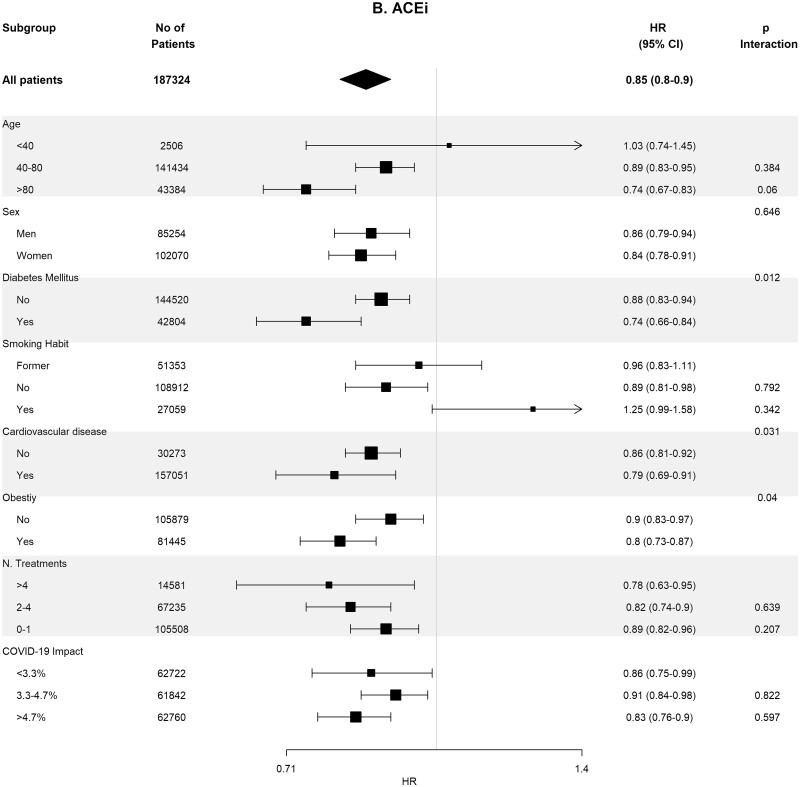

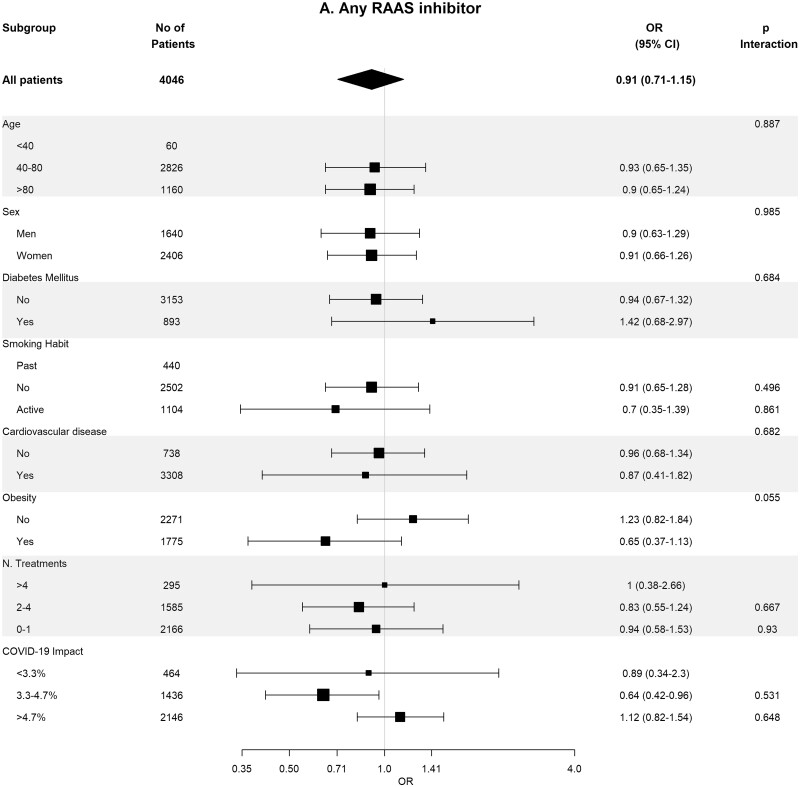

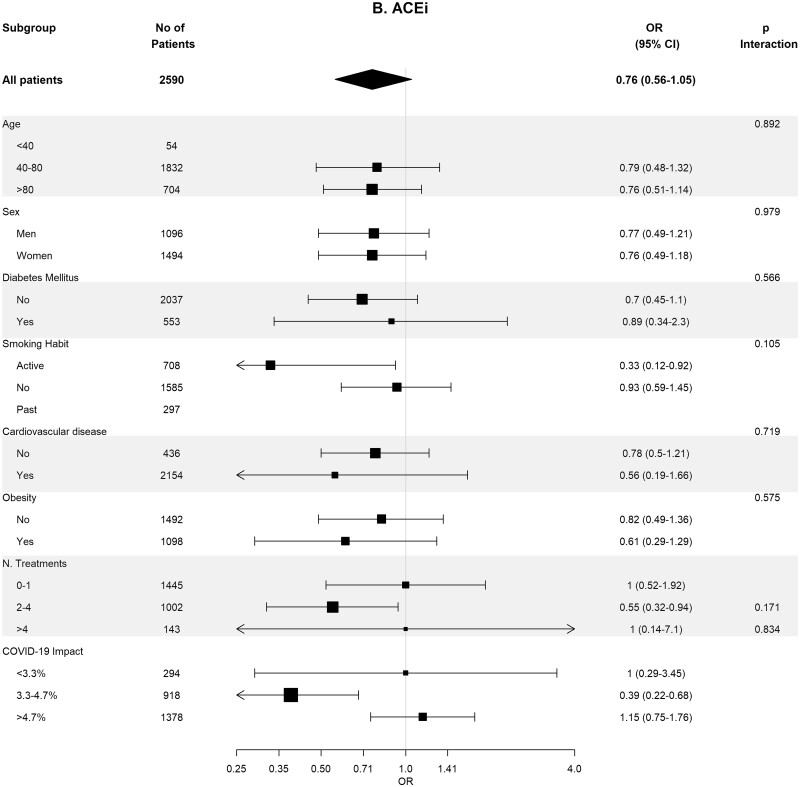

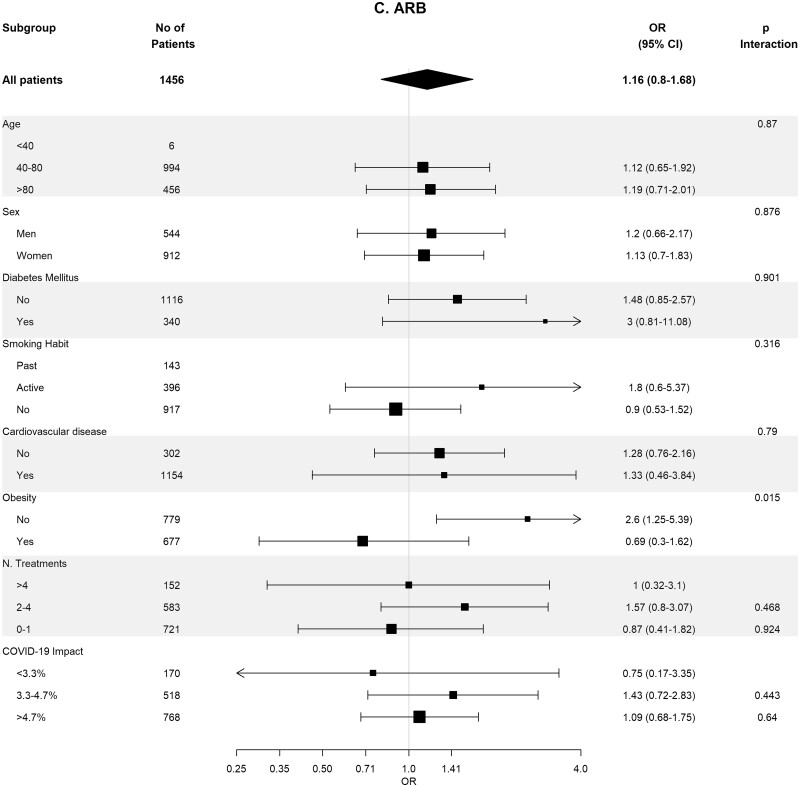

Table 4 shows the crude and adjusted effects of RAS (ACEi and ARB) use on main outcomes. In the age-, sex-, area- and propensity score-matched analyses, baseline differences between patients on RASis (ACEi users n = 1295, ARB users n = 728, any RASi n = 2023) were well balanced (Supplementary data, Tables S7 and S8). In the matched cohorts, there were no differences between RASi users and non-users regarding hospitalization, death, need for invasive respiratory support and the composite of death or need for invasive respiratory support (Table 4). Interestingly, the death rate was lower in ACEi users as compared with non-ACEi users [4.40% (95% CI 3.28–5.52%) versus 6.25% (95% CI 4.94–7.57%); P = 0.044]. Subgroup analyses for the risk of severe COVID-19 disease showed consistent results across the different subgroups (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted effect of RAS, ACEi and ARB use on main outcomes in COVID-19-infected patients

| RAS users versus non-users [HR (95% CI)] | P-value | ACEi users versus non-users [HR (95% CI)] | P-value | ARB users versus non-users [HR (95% CI)] | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Crude | 1.39 (1.27–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.20–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.33–1.66) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted | 1.22 (1.12–1.34) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) | 0.002 |

| Matched | 1.14 (0.98–1.33) | 0.097 | 1.18 (0.97–1.44) | 0.100 | 1.08 (0.84–1.39) | 0.559 |

| Death | ||||||

| Crude | 0.65 (0.56–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.60 (0.50–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.004 |

| Adjusted | 0.69 (0.59–0.82) | <0.001 | 0.66 (0.54–0.80) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.61–0.93) | 0.008 |

| Matched | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | 0.095 | 0.67 (0.46–0.96) | 0.030 | 1.00 (0.66–1.53) | 1 |

| Severe episode | ||||||

| Crude | 1.66 (1.31–2.13) | <0.001 | 1.60 (1.23–2.09) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.33–2.37) | <0.001 |

| Adjusted | 1.36 (1.07–1.75) | 0.015 | 1.30 (0.99–1.71) | 0.058 | 1.41 (1.05–1.91) | 0.024 |

| Matched | 1.26 (0.83–1.93) | 0.282 | 0.96 (0.56–1.65) | 0.891 | 2 (0.97–4.12) | 0.061 |

| Death or severe episode | ||||||

| Crude | 0.83 (0.73–0.95) | 0.005 | 0.77 (0.66–0.90) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 0.383 |

| Adjusted | 0.80 (0.69–0.92) | 0.001 | 0.77 (0.66–0.91) | 0.002 | 0.85 (0.71–1.02) | 0.077 |

| Matched | 0.91 (0.71–1.15) | 0.426 | 0.76 (0.56–1.05) | 0.095 | 1.16 (0.80–1.68) | 0.446 |

HR, hazard ratio.

FIGURE 3:

Association of recent use of RASis (A), ACEis (B) or ARBs (C) versus non-users with the risk of severe COVID-19 disease, stratified by different variables. Estimates are presented for the sex-, age- and propensity score-matched samples. N. Treatments, number of concomitant pharmacological treatments; COVID-19 impact, estimated prevalence of COVID-19 at the corresponding healthcare area.

DISCUSSION

In this large population-based, unselected cohort of 305 972 patients with HTN, recent use of ACEis or ARBs was associated with a lower 6-month cumulative incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis. In addition, in the 12 344 patients with COVID-19 infection, the use of ACEis or ARBs was not associated with a higher risk of hospitalization, need for invasive respiratory support or death.

SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses can infect host cells by means of interaction with membrane-bound ACE2 on alveolar epithelial cells [25]. ACE2 is an enzyme part of the RAS that shares around 40% homology with the classical ACE [2, 3]. Prior experimental and clinical studies demonstrated that treatment with RASis may increase ACE2 in different compartments in the body such as circulating ACE2 and ACE2 expression in the heart and renal vasculature [26–28]. For this reason, Fang et al. [29] suggested that treatment with ACEis or ARBs could increase the risk and severity of COVID-19 after exposure to SARS-CoV-2. This speculation motivated researchers to investigate this hypothesis, while medical societies urged against withdrawal of RAS blockade in patients with or at risk of cardiac or renal disease in the COVID-19 pandemic era [30].

The primary function of ACE2 is to counterbalance the actions of ACE. Thus, whereas ACE degrades angiotensin I to angiotensin II, ACE2 degrades angiotensin II into angiotensin-(1–7), exerting counterregulation of the RAS [31]. Circulating ACE2 activity is increased in patients with increased cardiovascular risk characteristics such as male sex, heart failure, myocardial infarction and diabetes [28, 32–34]. Some authors postulate that this increase in circulating ACE2 may be in part due to a compensatory mechanism, where in conditions with high cardiovascular risk the excess of angiotensin II accumulation may lead to a circulating rise of ACE2 to degrade angiotensin II to angiotensin-(1–7) [28, 35].

The potential harm related to RAS blockade in patients with COVID-19 infection has now been widely studied. In the last 6 months, 15 observational studies have been focused in the effect of prior RAS blockade on the severity of COVID-19 [36, 37]. Consistently, no association between ACEi or ARB use and illness severity has been found, in studies performed across several continents [36]. However, most of these studies were performed exclusively in hospitalized patients, who are not necessarily representative of the whole spectrum of COVID-19 patients, or used case–control designs, which are prone to several sources of bias [12, 14–16, 21, 38]. Among the latter, the most notable studies were performed by Mancia et al., de Abajo et al. and Fosbøl et al. [14–16]. Mancia et al. conducted a case–control study involving patients with confirmed COVID-19 in the Lombardy region of Italy. In this study, 6272 people with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were compared with 30 759 controls matched by age, sex and region. In a logistic-regression multivariate analysis, neither ACEis nor ARBs were associated with an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 [14]. Similarly, de Abajo et al. collected data from 11 139 hospitalized patients and 11 390 age- and sex-matched population controls from the Madrid region, and estimated that users of RASis had an adjusted OR for COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital of 0.94 (95% CI 0.77–1.15) [15]. Finally, in the nested case–control aspect of Fosbøl et al.’s study, the use of ACEis or ARBs compared with other antihypertensive medications, was not significantly associated with COVID-19 diagnosis in 494 170 patients with HTN (data from Danish national administrative registries) [16].

There are several cohort studies that have been conducted in community population cohorts. Reynolds et al. conducted a study based on data from the electronic health records of 12 594 patients in the New York University Langone Health system who were tested for COVID-19. A total of 5894 patients had a positive test, among whom 1002 had severe illness (defined as admission to the ICU, mechanical ventilation or death). The authors observed no positive association of any of the analysed drug classes, including ACEis and ARBs, with either a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result or severe illness [12]. In the retrospective cohort aspect of Fosbøl et al.’s study 4480 patients who were examined in a hospital and had a diagnosis code for COVID-19 were included [16]. Finally, the recently published Dublin et al. [20] study addresses two objectives, namely the association between RASis and the risk of COVID-19 diagnosis and the risk of hospitalization in the infected patients. Neither of these studies observed significant associations between RASi use and COVID-19 diagnosis or severity.

All of these studies, although well conducted and properly analysed, may have limited external validity because of the selection of the study population. For instance, although Dublin et al.’s study had a population-based setting, the final study population was highly selected, since only 322 044 out of 732 410 potential participants were ultimately included [20].

Our study performed in an unselected cohort of 305 972 patients with HTN has demonstrated, using a properly balanced 93 662 age-, sex-, area- and propensity score-matched pairs, that prior treatment with RASis in this high cardiovascular risk cohort is associated with a lower frequency of COVID-19 diagnosis. Whether this association is related to the effect of RAS blockade, or the treatment with RASis is merely a marker of other unknown factors should be elucidated in a randomized clinical trial. In any case, this finding is in concordance with a recently published meta-analysis that included three studies with a total of 8766 patients with COVID-19, showing that ACEis or ARBs were not associated with a higher likelihood of positive SARS-CoV-2 test results in symptomatic patients [36].

In agreement with the majority of previous observational studies, in our large cohort in hypertensive patients from Catalonia (Spain), we have been able to replicate the same results and demonstrated that there was no association between ACEis or ARBs and negative outcomes such as hospitalization, total mortality, need for invasive organ/respiratory support and the composite of total mortality or need for invasive organ/respiratory support in COVID-19-infected patients. Furthermore, the BRACE CORONA study, the first randomized clinical trial with results available demonstrated that among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection and receiving chronic ACEis/ARBs, suspending ACEis/ARBs was not beneficial/deleterious in terms of mortality and hospitalization days [13]. In addition, in the REPLACE COVID study, a multicentre trial involving 20 sites in seven countries, there was a total enrolment of 152 patients who were admitted to hospital with COVID-19. COVID-19 patients were randomly assigned to continuation or discontinuation of RAASis. The primary composite endpoint, which was a global rank score based on (i) days to death during hospitalization, (ii) days on mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxigenation, (iii) days requiring kidney replacement therapy, inotropes or pressors; and, for patients who did not fit into the previous three categories, (iv) area under the curve of a modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score. Similar to the previous study, there was no significant difference in any of the secondary endpoints examined, including all-cause death, length of hospitalization, ICU admission or duration of mechanical ventilation [10]. On the basis of these findings, no evidence exists to recommend RAS blockade withdrawal for COVID-19 concerns. Furthermore, in patients at risk for CVD such as our studied population with HTN, diabetes or CVD, RAS discontinuation may play a deleterious role in cardio- and renoprotection.

Limitations of our work include the retrospective and observational study design that lack the causal interpretation provided by interventional studies and randomized clinical trials. Another limitation of our study is that the number of people tested for COVID-19 varied over time during the study period. At the beginning, a larger amount of people with possible COVID-19 were not tested, especially those with no or mild symptoms and who were not hospitalized. Thus, the proportion of people infected is very likely underestimated and the proportions of patients with severe illness among the infected are likely overestimated. At the time of the study, there was no clear recommendation from scientific societies regarding what to do with RAS therapy in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and the decision to suspend or maintain RAS therapy was left to the physician’s discretion. Although we do not have specific data in the entire cohort, we were able to retrospectively analyse the data from our single centre. A total of 1413 patients were hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19. Of these, 435 (31%) patients were on RAS blockade at the time of hospitalization. Of these, 154 (35%) patients withdrew RAS therapy during the first 3 days of hospitalization. Thus, based on this indirect analysis, we can infer that the most common decision at the time of the study was to maintain RAS therapy. In any case, we do not believe that the interruption of this therapy during hospitalization in part of the cohort could affect the results, in light of the results of the BRACE CORONA study [13].

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that the use of RAS blockade in patients with HTN does not increase the risk of COVID-19 diagnosis or of disease severity among patients with COVID-19.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at ckj online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Manuel Medina-Peralta from SISAP in the ICS for supervision of data extraction and Sònia Abilleira from ICS for supervision of data extraction and for reviewing the manuscript.

FUNDING

The study was partially funded by ‘CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP)’.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M.J.S. reports personal fees from NovoNordisk (Honoraria, Advisory), Janssen (honoraria), Boehringer (honoraria, advisory, grant and consultancy), Eli Lilly (Honoraria), AstraZeneca (honoraria and advisory), Esteve (honoraria), Fresenius Medical Care (honoraria), Mundipharma (honoraria and advisory) and Vifor (honoraria and advisory). M.J.S. is also a Member of the CKJ Editorial Board.

Contributor Information

María José Soler, Department of Nephrology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Nephrology Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain.

Aida Ribera, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Josep R Marsal, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain.

Ana Belen Mendez, Department of Cardiology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain.

Mireia Andres, Department of Cardiology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Maria Antonia Azancot, Department of Nephrology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Nephrology Research Group, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain.

Gerard Oristrell, Department of Cardiology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain.

Leonardo Méndez-Boo, Departament de Salut, SISAP: Sistema d′Informació dels Serveis d′Atenció Primària, Direcció de Sistemes d′Informació, Institut Català de la Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain.

Jordana Cohen, Division of Renal-Electrolyte and Hypertension, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania, PA, USA.

Jose A Barrabés, Department of Cardiology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Ignacio Ferreira-González, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Madrid, Spain; Department of Cardiology, Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR), Barcelona, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sparks MA, South A, Welling P et al. Sound science before quick judgement regarding RAS blockade in COVID-19. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 714–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res 2000; 87: E1–E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crackower MA, Sarao R, Oudit GY et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature 2002; 417: 822–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soler MJ, Wysocki J, Batlle D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and the kidney. Exp Physiol 2008; 93: 549–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wysocki J, Lores E, Ye M et al. Kidney and lung ACE2 expression after an ACE inhibitor or an Ang II receptor blocker: implications for COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31: 1941–1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee IT, Nakayama T, Wu CT et al. ACE2 localizes to the respiratory cilia and is not increased by ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallentin L, Lindbäck J, Eriksson N et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) levels in relation to risk factors for COVID-19 in two large cohorts of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 4037–4046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vergara A, Jacobs-Cachá C, Molina-Van den Bosch M et al. Effect of ramipril on kidney, lung and heart ACE2 in a diabetic mice model. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2021; 529: 111263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS et al. Association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5: 1020–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen JB, Hanff TC, William P et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen JB, D’Agostino McGowan L, Jensen ET et al. Evaluating sources of bias in observational studies of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blocker use during coronavirus disease 2019: beyond confounding. J Hypertens 2021; 39: 795–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2441–2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, De Barros E Silva PGM et al. ; BRACE CORONA Investigators. Effect of discontinuing vs. continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers on days alive and out of the hospital in patients admitted with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 254–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockers and the risk of COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2431–2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Abajo FJ, Rodríguez-Martín S, Lerma V et al. Use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1705–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fosbøl EL, Butt JH, Østergaard L et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker use with COVID-19 diagnosis and mortality. JAMA 2020; 324: 168–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Case-control studies: research in reverse. Lancet 2002; 359: 431–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen C, Wang F, Chen P et al. Mortality and pre-hospitalization use of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in patients with hypertension and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9: e017736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soleimani A, Kazemian S, Karbalai Saleh S et al. Effects of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) on in-hospital outcomes of patients with hypertension and confirmed or clinically suspected COVID-19. Am J Hypertens 2020; 33: 1102–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dublin S, Walker R, Floyd J et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and COVID-19 infection or hospitalization: a cohort study. Am J Hypertens 2021; 34: 339–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ssentongo AE, Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and the risk of mortality in patients with hypertension hospitalised for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2020; 7: e001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ramos R, Balló E, Marrugat J et al. Validity for use in research on vascular diseases of the SIDIAP (information system for the development of research in primary care): the EMMA study. Rev Español Cardiol 2012; 65: 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burn E, You SC, Sena AG et al. Deep phenotyping of 34,128 adult patients hospitalised with COVID-19 in an international network study. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 5009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caro-Mendivelso J, Elorza-Ricar J, Hermosilla E et al. Associations between socioeconomic index and mortality in rural and urban small geographic areas of Catalonia, Spain: ecological study. J Epidemiol Res 2015; 2: 80 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Batlle D, Soler MJ, Sparks MA et al. ; COVID-19 and ACE2 in Cardiovascular, Lung, and Kidney Working Group. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: emerging evidence of a distinct pathophysiology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 31: 1380–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soler MJ, Barrios C, Oliva R, Batlle D. Pharmacologic modulation of ACE2 expression. Curr Hypertens Rep 2008; 10: 410–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Soler MJ, Ye M, Wysocki J et al. Localization of ACE2 in the renal vasculature: amplification by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade using telmisartan. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2009; 296: F398–F405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J et al. ; NEFRONA Study. Circulating angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease without previous history of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1176–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sparks MA. The Coronavirus Conundrum: ACE2 and Hypertension Edition. NephJC http://www.nephjc.com/news/covidace2 (2020). (8 September 2021, date last accessed)

- 31. Batlle D, Soler MJ, Ye M. ACE2 and diabetes: ACE of ACEs? Diabetes 2010; 59: 2994–2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Epelman S, Tang WH, Chen SY et al. Detection of soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in heart failure: insights into the endogenous counter-regulatory pathway of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 750–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ortiz-Pérez JT, Riera M, Bosch X et al. Role of circulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: a prospective controlled study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e61695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soro-Paavonen A, Gordin D, Forsblom C et al. Circulating ACE2 activity is increased in patients with type 1 diabetes and vascular complications. J Hypertens 2012; 30: 375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J et al. Circulating angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity as a biomarker of silent atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Atherosclerosis 2016; 253: 135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mackey K, King VJ, Gurley S et al. Risks and impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers on SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults: a living systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173: 195–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cordeanu E-M, Jambert L, Severac F et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalized patients previously treated with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 3472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1054–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.