Purpose of review

Restrictions put in place to contain the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have significantly affected the lives of children and adolescents worldwide. School closure, home confinement and social distancing have the potential to negatively impact the mental health of this population. Several risk factors seem to contribute to worsening mental health of children and adolescents, with an increase of anxiety and depression symptoms. This review aims at exploring research available on risk factors that may worsen the mental health among children and adolescents during the pandemic.

Recent findings

Some of these predictors in worsening the effects are social isolation, screen time and excessive social media use, parental stress and poor parent–child relationship, low socioeconomic status, preexisting mental health conditions and/or disabilities.

Summary

Further research is needed in order to understand mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as risk factors associated with negative consequences. New findings will help in targeting evidence-based interventions to prevent and mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents.

Keywords: adolescents, children, coronavirus disease 2019, mental health, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease has significantly changed life and habits around the world. Measures taken to contain the spread of the virus had a severe impact on children's and adolescents’ lives, potentially negatively affecting their mental health and well being. Several studies conducted at different stages of the pandemic and in different countries found high rates of depressive, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) symptoms in children and adolescents of all ages [1▪]. School closures and limited outdoor leisure time activities have strongly restricted youngsters’ social interactions with their friends, which can be a risk factor for children's and adolescents’ psychological well being, as peer relationships play a key role in their development [2▪]. Children have been confined at home with their parents for a relatively long period of time, which can be a protective factor for children's well being [3▪▪] but in some cases, this has led to frictions and distress [1▪]. Financial loss and uncertainty for the future because of the economic recession added further pressure on parents, potentially worsening children's well being [2▪]. Some children may, therefore, be more vulnerable than others to negative psychosocial effects of the pandemic and some factors seem to impact more than others on the well being of children and adolescents. The purpose of this brief review is to outline the major risk factors associated with the current pandemic that may worsen the mental health of children and adolescents.

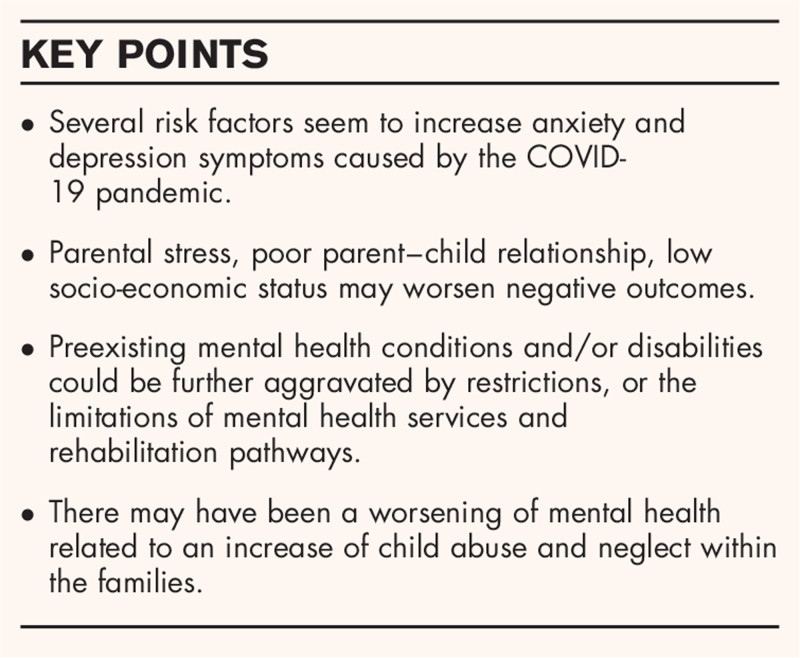

Box 1.

no caption available

FINDINGS

Age and gender

Research suggests that the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic may affect children and adolescents differently according to sex. McKune et al.[4▪▪] examined risk factors for psychological outcomes, such as anxiety, depressive and obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD)-related symptoms, in a group of school-aged children during the early phase of the pandemic. Results showed that female individuals were at higher risk of presenting these symptoms of depression, anxiety and OCD. Similarly, Zhou et al.[5▪▪] in a sample of more than 8000 adolescents aged 12–18 years, found that being a female was a risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. A study conducted by Magson et al.[6▪▪] also showed greater depressive symptoms and anxiety in adolescent girls (13–16 years). In another study [7▪], male individuals showed increased oppositional-defiant and aggressive problems than female individuals. This is in line with previous studies indicating that female individuals tend to manifest more internalizing disorders, whereas male individuals exhibit more externalizing disorders [8]. Research also suggests that symptoms of mental health problems may be more likely to increase with age. Zhou et al.[5▪▪] demonstrated that attending senior grades, compared with junior grades, was a risk factor for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Chen et al.[9▪] also found more depressed and anxious adolescents in 13–15 years old group compared with 6–8 and 9–12 years old group (21.15 vs. 3.21 vs. 9.68% for depression; and 23.5 vs. 12.54 vs. 20.32% for anxiety, respectively). Nonetheless, with respect to age, research is not consistent. Jiao et al.[10] found mixed results for age effect, whereas a second study found no effect of age or grade on mental health outcomes [11]. Schmidt et al.[7▪] compared the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in three age groups: preschool children (1–6 years old), school children (7–10 years old) and adolescents (from 11 years old), founding that all age groups showed worsening mental health, although symptoms differed by age.

School closure, social isolation and loneliness

School closures have affected more than 150 countries, with 214 million children worldwide losing at least three quarters of classroom instruction time [12]. Since the beginning of the pandemic, it has been argued that school closures represent one of the most disruptive events for youngsters during the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. School is a place where children and adolescents spend a large amount of their lives [14], and its importance for children's and adolescents’ development goes beyond its educational function. In fact, for many students, school is the only way to access health and mental health services [15], and there is also evidence that school closure is affecting children's nutrition as school meals are often the only source of food for many vulnerable children around the world, which in turn can affect their cognitive and learning abilities [16]. Moreover, school represents a central development context for children and adolescents, and school-based relationships with peers and teachers play an important role in the well being of young people [17].

During the lockdown and the coronavirus pandemic, children and adolescents lived in a prolonged state of physical isolation from their social connections: peers, teachers, relatives and community networks [18▪]. Coronavirus restrictions are likely to result in increased loneliness [18▪]. Loneliness is a subjective perception, defined as a discrepancy between the social contacts a person would like to have and the social contacts he or she actually has [1▪,18▪,19]. Loneliness has been associated with a greater probability of developing mental health problems [18▪,20]. For instance, there is evidence showing that a sustained experience of loneliness during childhood predicts symptoms of depression reported during adolescence [21]. Although social isolation and loneliness are not necessarily co-existent, some studies indicated that adolescents and young people reported high levels of loneliness during lockdown [18▪]. For example, more than 31% of parents (n = 1143) interviewed by Orgilés et al.[22▪] reported feelings of loneliness as one of the symptoms most frequently experienced by their children during the very early phase of the pandemic. The negative effects of social and physical distancing might be particularly present in adolescents and young adults as adolescence is a crucial period for social interactions [23,24]. Cooper et al.[3▪▪] conducted an online survey on adolescents aged 11–16 years (n = 894) to investigate the association between perceived loneliness during the pandemic and various symptoms of poor mental health, including internalizing and externalizing problems and psychological distress. Higher levels of loneliness were correlated with higher levels on all mental health scales.

Similar results are reported by Rauschenberg et al.[25▪▪], in Germany. The authors, in a sample of adolescents and young adults aged 16–25 years, found a higher likelihood of experiencing psychological distress during the pandemic in people who reported subjective experiences of social isolation. Specifically, individuals who reported being ’often’ or ’very often’ socially isolated were respectively 22 and 42 times more likely to experience psychological distress than those who reported ‘never’ being socially isolated (ibidem).

Severity of restrictions

Harshness of restrictions adopted by governments and differences in confinement rules could also have determined differences in mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. One study [39▪▪] examined the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in a sample of Spanish, Italian and Portuguese children and adolescents (3–18 years old). Spanish and Italian children showed higher levels of depression compared with Portuguese children whereas Spanish children reported more symptoms of anxiety compared with both Italian and Portuguese children. According to the authors, this could be explained by the fact that in Italy and Spain, confinement was mandatory, whereas in Portugal, it was only recommended. Moreover, at the time of data collection, Italian children had been allowed to go out for walks for several weeks, whereas Spanish children had only been allowed to go out for 1 week (ibidem).

Screen time and social media use

There is evidence that screen time and social media use have increased during the pandemic [26–28]. This was to be expected as many activities have been carried out remotely, starting with school. Social media has been helpful during confinement in maintaining social relationships with relatives and peers and helping to cope with loneliness and anxiety [26]. However, excessive Internet use may also have negatively affected children and adolescents’ well being. For example, Cauberghe et al.[26] found an increased use of social media among adolescent girls to keep in touch with friends and family, especially those who experienced higher levels of loneliness; however, this finding was not associated with a heightened feeling of happiness (ibidem). Muzi et al.[28] found higher levels of problematic social media use during the pandemic in a sample of Italian adolescents, compared with prepandemic levels. Increased problematic social media use was associated with more emotional and behavioural symptoms, such as delinquent and attention problems, and binge eating behaviour (ibidem). Previous research has found that excessive screen time may be associated with several health risks, including poor sleep quality, cardiovascular diseases, and mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety and suicide [29]. Moreover, uncontrolled Internet use may have exposed children and adolescents to online risks, such as cyberbullying, cyber predators and exposure to inappropriate content (e.g. sexual or violent material) [30].

The Internet and social media have also been an important source of information on the pandemic, especially during these past months. At the same time, the overabundance of information on coronavirus has generated an ‘infodemic’ that can be harmful to people's mental health [31]. One study conducted in China found that the exposure to radio reports around COVID-19 was associated with greater depression and anxiety [32]. Similarly, Magson et al. [6▪▪] found that COVID-19-related distress and feeling socially disconnected from others were significantly associated with viewing posts about coronavirus on social media.

Orben et al.[23], however, observed that in order to understand how digital technologies impact young people who are physical distancing, we need to differentiate between connection promoting (i.e. active and communicative) and nonconnection promoting (i.e. passive) uses of social media, and not focusing uniquely on the time spent online. Furthermore, consequences of the use of social media and digital technologies during the pandemic should also consider individual differences (ibidem).

Parent–child relationship and parental stress

A good parent–child relationship can be an important protective factor for children's mental health when coping with natural disasters [33] and this also seems to apply to COVID-19 pandemic. Cooper et al.[3▪▪] found that adolescents who reported being closer to their parents showed fewer symptoms related to mental disorders and feelings of loneliness. Wang et al.[34] found a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms in adolescents with good parent–child relationship, compared with those with poor parent–child relationship (16.3 vs. 52.4%). On the contrary, parental distress and poor mental health can predict a worsening in children's mental health (ibidem).

Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a reorganization of habits and rules within the family. The families had to cope with the stress of quarantine and social distancing, with home-schooling and home-working and in most cases, this situation resulted in a considerable amount of stress and psychological distress [2▪]. Not only fear of the disease itself, fear of losing family members but also grief and mourning may lead to adjustment problems, posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental health issues (ibidem). Caffo et al. [35] report results from a national Italian survey conducted by Telefono Azzurro and DoxaKids during the quarantine. A sample of 291 Italian parents, with at least one son aged from 0 to 18 years old, was interviewed. According to the results, 61% of the participants declared that their involvement in their sons’ school activities had been increased. Moreover, 23% of them experienced difficulties at home during the quarantine, 18% found it difficult to find adequate spaces inside the house and 20% found it difficult to coordinate between homeworking and their children's online school activities (ibidem). One study found that parents with higher distress and anxiety were more likely to observe distress in their children [36▪▪]. Findings from a longitudinal study conducted in the UK suggest that young women living with children, especially school age children, are more likely to show an increase of mental distress during the pandemic [37] In one study, children and adolescents reported higher mental and social health complaints during the lockdown if they were part of a single-parent family or if there were three or more children in the family [38▪▪]. Orgilés et al.[39▪▪] found that anxiety and depressive symptoms were higher in those children whose parents reported higher levels of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Poor parental mental health was found to be one of the main factors to influence mental health outcomes in preschool and school children but not in adolescents [7▪].

Socioeconomic status and economic challenges

As the pandemic extended to low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), there have been growing concerns about the risks of coronavirus disease [40]. In these countries, reduced access to care, poverty and other factors may lead to delays in seeking care for sick children (ibidem). All over the globe, during the pandemic, low-income families faced additional threats and consequences on children's health, well being and learning gap [41]. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, one study had already found that school closure during summer holidays could lead students, especially those coming from poorer families, to experience more feelings of loneliness, which can negatively impact their mental well being [42]. In Europe, 5% of children live in homes in which they have no place to do homework and 6.9% have no access to the Internet [41,43]. This can lead to difficulties in accessing alternative modalities, like home-schooling or telemedicine [2▪].

Furthermore, the pandemic is causing a serious economic recession, adding pressure on low-income families, which in turn can negatively affect children's well being [2▪,44]. In a study conducted in the United States [36▪▪], financial difficulties predicted higher anxiety and depressive symptoms. McKune et al.[4▪▪] also found an association between loss of household income and increased risk of depressive, anxiety and OCD symptoms in school-aged children and adolescents. Moreover, Zhou et al.[5▪▪] found higher rates of both anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents (12–18 years old) living in rural areas than those living in urban areas (40.4 vs. 32.5% and 47.5 vs. 37.7%, respectively), suggesting that families living in rural areas are more economically disadvantaged than those living in cities (i). Therefore, during the ongoing pandemic, socioeconomic status and social factors can be predictors of poor mental health in children and adolescents [2▪,45].

Children with disabilities and/or preexisting mental health conditions and reduction in health services activity

Since the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic, researchers and mental health professionals have expressed particular concern for children with prior mental illness, whose lives may have been highly impacted by restrictive measures. For example, the UK charity organization YoungMinds [46] interviewed adolescents with psychiatric disorders, and 83% of them reported a worsening in their mental health. In a study conducted in Turkey by Tanir et al.[47▪▪], children and adolescents (aged 6–18 years) with a previous diagnosis of OCD reported an increase in the frequency of contamination obsessions and cleaning/washing compulsions during the pandemic period.

Of particular concern are children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), whose development could deteriorate because of uncertainty and social restrictions, which may also cause more intense and frequent behaviour problems, as shown by Colizzi et al.[48▪▪]. Masi et al.[49▪▪] also examined the mental health of children (2–17 years old) with neurodevelopmental disabilities (NDD), such as ADHD and ASD, through an online survey distributed to parents and caregivers (n = 302). More than 76% of respondents reported a worsening in overall children's well being, whereas 64.7% reported a deterioration of NDD or comorbidity symptoms. Additionally, the condition of children and adolescents with preexisting conditions could be further aggravated by the limitations of mental health services and rehabilitation pathways [1▪,2▪,50]. In the study by Masi et al.[49▪▪], parents reported low effectiveness of services and support received during the pandemic: 68.8% used telehealth services during this period, but only 30% said telehealth worked well for their children. Furthermore, 41.3% reported that telehealth services for therapy were not an option for their children (ibidem). However, not everyone agrees on the fact that the pandemic is worsening the clinical condition of these patients. For example, Lavenne-Collot et al.[51] found no worsening in the clinical condition of children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders during lockdown. According to the authors, having to remain confined at home with their family may have been a protective factor for these patients.

Domestic violence and child maltreatment

An important risk factor that should be further investigated is the worsening of mental health of children and adolescents related to an increase of child abuse and neglect within the families. Since the beginning of the pandemic, authors have drawn attention to the risk of an increase in child abuse and maltreatment [2▪,52,53]. Mandatory stay-at-home, school closures and movement restrictions, although necessary to reduce the spread of the virus, left many children and adolescents confined with violent adults increasingly frustrated by stress and other risk factors related to pandemic, such as unemployment or increased consumption of alcohol [52]. Research conducted after natural disasters or conflicts reports a surge in cases of domestic violence [54], and there is already evidence that this is also occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kovler et al.[55], for example, reported an increase in trauma attributable to child physical abuse at the Johns Hopkins Children's Center paediatric trauma centre. Specifically, in 2020, 13% of total trauma patients were identified as victims of child physical abuse, compared with 4 and 3% in the same period in 2019 and 2018, respectively. The average age of these patients was 11.5 months. Children victims of abuse have a higher probability of suffering from several psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety and PTSD that may persist into adulthood [2▪], therefore, it is essential to intervene early. However, during the pandemic, many cases of abuse may have gone unnoticed as many community services, starting with schools, remained closed.

CONCLUSION

Studies conducted during the pandemic found increased symptoms of mental health problems in youngsters, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms. School closures and physical distancing in many cases generated a feeling of loneliness in children and adolescents [39▪▪], which could cause psychosocial distress [18▪]. A good parent–child relationship may have acted as a protective factor against loneliness and other symptoms of poor mental health [3▪▪] but on the other hand, children of parents who reported high distress showed increased levels of anxiety and depression [39▪▪]. Children and adolescents living in poor socioeconomic conditions could be more negatively impacted by the pandemic. These children had less opportunity to study from home and access mental health services, increasing preexisting social and learning gaps. Children's and adolescents’ mental health may have suffered of COVID-19 changes in the presence of preexisting mental health conditions or disabilities [48▪▪,49▪▪]. Future and more accurate research should be implemented to better understand how the pandemic is impacting children's and adolescents’ mental health, what are the risk factors that could worsen the outcomes, and if these consequences will last in the mid-long term. New findings will help in targeting evidence-based interventions to prevent and mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1▪.Marques de Miranda D, da Silva Athanasio B, Sena Oliveira AC, Simoes-E-Silva AC. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 2020; 51:101845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This comprehensive review provides a detailed outline of major effects of the pandemic on children's and adolescents’ mental health.

- 2▪.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2020; 14:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review outlines major challenges for the mental health of children and adolescents during the pandemic and provides important insights for the implementation of policies enacted to contain the effects of the pandemic on children's and adolescents’ mental health.

- 3▪▪.Cooper K, Hards E, Moltrecht B, et al. Loneliness, social relationships, and mental health in adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 2021; 289:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examines cross-sectional associations and longitudinal relationships between loneliness, social contact, parent relationships and subsequent mental health.

- 4▪▪.McKune SL, Acosta D, Diaz N, et al. Psychosocial health of school-aged children during the initial COVID-19 safer-at-home school mandates in Florida: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021; 21:603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This cross-sectional study identifies risk factors associated with worsening of mental health, specifically depressive, anxiety-related and OCD-related symptoms.

- 5▪▪.Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020; 29:749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is one of the first studies that assesses the prevalence rate and socio-demographic correlates of depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese adolescents.

- 6▪▪.Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, et al. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc 2021; 50:44–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first longitudinal study that investigates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents’ mental health and that assesses the risk factors.

- 7▪.Schmidt SJ, Barblan LP, Lory I, Landolt MA. Age-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2021; 12:1901407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study investigates the age-related effects of the pandemic on children aged 1–19 years, finding significant age-related effects regarding the type and the frequency of the problems.

- 8.Van Droogenbroeck F, Spruyt B, Keppens G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪.Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, et al. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun 2020; 88:36–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The study assessed the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in a sample of Chinese children (6–15 years), finding higher prevalence in older children.

- 10.Jiao WY, Wang LN, Liu J, et al. Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Pediatr 2020; 221:264.e1–266.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu S, Liu Y, Liu Y. Somatic symptoms and concern regarding COVID-19 among Chinese college and primary school students: a cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res 2020; 289:113070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNICEF. Covid-19 and school closures. One year of education disruption. March, 2021. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/resources/one-year-of-covid-19-and-school-closures/. (Accessed 11 May 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman JA, Miller EA. Addressing the consequences of school closure due to COVID-19 on children's physical and mental well being. World Med Health Policy 2020; 12:300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu T, Tomokawa S, Gregorio ER, Jr, et al. School-based interventions to promote adolescent health: a systematic review in low- and middle-income countries of WHO Western Pacific Region. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0230046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr 2020; 174:819–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borkowski A, Ortiz Correa JS, Bundy DAP, et al. COVID-19: missing more than a classroom. The impact of school closures on children's nutrition. Florence: Innocenti Working Paper 2021–01, UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiuru N, Wang MT, Salmela-Aro K, et al. Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. J Youth Adolescence 2020; 49:1057–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18▪.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2020; 59:1218.e3–1239.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This systematic review outlines major findings on the impact of loneliness and containment measures on children's and adolescents’ mental health, showing that these factors increase the risk of depression and possibly anxiety.

- 19.Perlman D, Peplau LA. Gilmour R, Duck S. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal relationships. London: Academic Press; 1981. 31.e3–56.e3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D, et al. Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017; 52:1451–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qualter P, Brown SL, Munn P, Rotenberg KJ. Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: an 8-year longitudinal study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010; 19:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22▪.Orgilés M, Morales A, Delvecchio E, et al. Immediate psychological effects of the COVID-19 quarantine in youth from Italy and Spain. Front Psychol 2020; 11:579038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides information about the effects of home confinement on children's mental health in two European countries, reporting changes in children's emotional states and behaviors.

- 23.Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore SJ. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020; 4:634–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blakemore SJ, Mills KL. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu Rev Psychol 2014; 65:187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25▪▪.Rauschenberg C, Schick A, Goetzl C, et al. Social isolation, mental health, and use of digital interventions in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationally representative survey. Eur Psychiatry 2021; 64:e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study indicates that during the pandemic, psychological distress was progressively more likely to occur as levels of social isolation increased.

- 26.Cauberghe V, Van Wesenbeeck I, De Jans S, et al. How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2021; 24:250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt SCE, Anedda B, Burchartz A, et al. Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: a natural experiment. Sci Rep 2020; 10:21780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muzi S, Sansò A, Pace CS. What's happened to Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A preliminary study on symptoms, problematic social media usage, and attachment: relationships and differences with prepandemic peers. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12:590543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagata JM, Abdel Magid HS, Pettee Gabriel K. Screen time for children and adolescents during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020; 28:1582–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobe B, Velicu A, Staksrud E, et al. How children (10–18) experienced online risks during the Covid-19 lockdown, Publication Office of the European Union, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Managing the COVID-19 infodemic: promoting healthy behaviours and mitigating the harm from misinformation and disinformation. 23 September 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-09-2020-managing-the-covid-19-infodemic-promoting-healthy-behaviours-and-mitigating-the-harm-from-misinformation-and-disinformation. Accessed on May 26, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17:1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung G, Lanier P, Wong PYJ. Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. J Fam Viol 2020. 1–12. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Wang H, Lin H, et al. Study problems and depressive symptoms in adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak: poor parent-child relationship as a vulnerability. Global Health 2021; 17:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caffo E, Scandroglio F, Asta L. Debate: COVID-19 and psychological well being of children and adolescents in Italy. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2020; 25:167–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36▪▪.Rosen Z, Weinberger-Litman SL, Rosenzweig C, et al. Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U. S due to COVID-19: psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. PsyArXiv 2020; Available at: https://psyarxiv.com/7eq8c/ Accessed on June 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]; This study assesses distress/anxiety and predictors of distress/anxiety associated with quarantine because of COVID-19 exposure in the United States (303 participants). Distress levels were markedly elevated among people in quarantine.

- 37.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7:883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38▪▪.Luijten MAJ, van Muilekom MM, Teela L, et al. The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and social health of children and adolescents. Qual Life Res 2021. 1–10. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study compared two representative samples of Dutch children and adolescents (8–18 years) before COVID-19 (2018) and during lockdown (April 2020). Results reported a worsening on all PROMIS domains.

- 39▪▪.Orgilés M, Espada JP, Delvecchio E, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a transcultural approach. Psicothema 2021; 33:125–130. Doi: 10.7334/psicothema2020.287. PMID: 33453745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This comparative study found differences in anxiety and depression between countries (Spain, Italy and Portugal) and highlighted that anxiety and depressive symptoms were more likely in children (3–18 years) whose parents reported higher levels of stress.

- 40.Zar HJ, Dawa J, Fischer GB, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Challenges of COVID-19 in children in low- and middle-income countries. Paediatr Respir Rev 2020; 35:70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 2020; 5:e243–e244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgan K, Melendez-Torres GJ, Bond A, et al. Socio-economic inequalities in adolescent summer holiday experiences, and mental wellbeing on return to school: analysis of the school health research network/health behaviour in school-aged children survey in Wales. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16:1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guio AC, Gordon D, Marlier E, et al. Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indic Res 2018; 11:835–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiernan FM. Income loss and the mental health of young mothers: evidence from the recession in Ireland. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2019; 22:131–149. PMID: 32060231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vukojević M, Zovko A, Talić I, et al. Parental socioeconomic status as a predictor of physical and mental health outcomes in children - literature review. Acta Clin Croat 2017; 56:742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young Minds. Coronavirus: impact on young people with mental health needs. Coronavirus report March 2020. Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3708/coronavirus-report_march2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 47▪▪.Tanir Y, Karayagmurlu A, Kaya İ, et al. Exacerbation of obsessive compulsive disorder symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020; 293:113363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Young subjects (6–18 years) with a diagnosis of OCD reported an increase in the frequency of contamination obsessions and cleaning/washing compulsions during the pandemic period.

- 48▪▪.Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: an online parent survey. Brain Sci 2020; 10:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Parents and guardians of young individuals with ASD (mean age 13 years) reported more intense and more frequent disruptive behavior in children who had behavior problems before the COVID-19 outbreak.

- 49▪▪.Masi A, Mendoza Diaz A, Tully L, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well being of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents. J Paediatr Child Health 2021; 57:631–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Caregivers of children aged 2–17 years with a NDD reported a worsening of child health and well being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- 50.Constantino JN, Sahin M, Piven J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: clinical and scientific priorities. Am J Psychiatry 2020; 177:1091–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lavenne-Collot N, Ailliot P, Badic S, et al. Les enfants suivis en psychiatrie infanto-juvénile ont-ils connu la dégradation redoutée pendant la période de confinement liée à la pandémie COVID-19 ? [Did child-psychiatry patients really experience the dreaded clinical degradation during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown?]. Neuropsychiatrie de l’enfance et de l’adolescence 2021; 69:121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci Int Rep 2020; 2:100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 2020; 146:e20200982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seddighi H, Salmani I, Javadi MH, Seddighi S. Child abuse in natural disasters and conflicts: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021; 22:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kovler ML, Ziegfeld S, Ryan LM, et al. Increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl 2021; 116 (Pt 2):104756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]