Purpose of review

In order to promote optimal development of children and adolescents at risk for psychiatric disorders, a better understanding of the concept resilience is crucial. Here, we provide an overview of recent work on clinical and epidemiological correlates of resilience and mental health in children and adolescents.

Recent findings

Our systematic literature search revealed 25 studies that unanimously show that higher levels of resilience are related to fewer mental health problems, despite the heterogeneity of study populations and instruments. Correlates of resilience included multisystem factors, such as social, cultural, family and individual aspects, which is in line with the multisystem approach as described by recent resilience theories. Longitudinal studies are scarce but confirm the dynamical character of resilience and mental health. The application of longitudinal studies and innovative measurement techniques will improve our understanding on the cascade effects of stressors on resilience and mental health outcomes.

Summary

Resilience is strongly associated with mental health in children and adolescents and deserves a more prominent role in research, prevention programs and routine clinical care. Including social, cultural and family context in the evaluation of resilience is of great value, as this can identify targets for early and preventive interventions.

Keywords: children and adolescents, mental health, psychopathology, resilience

INTRODUCTION

Childhood adversity, parental psychopathology, bullying and significant threats are established risk factors for the development of psychopathology in children and adolescents [1,2▪,3–5]. However, the identification of risk factors does not necessarily lead to accurate prediction of psychopathology or adequate prevention. We argue that studies on emerging psychopathology should focus on factors that contribute to both risk and resilience. However, much less is known about factors that promote normative development or protect children and adolescents at risk for psychopathology. Insight into resilience and its modifiable clinical and epidemiological correlates in children and adolescents is important to inform clinicians and researchers on targets for preventive and early intervention strategies.

The purpose of this selected review is to provide an overview of recent work on resilience, its clinical and epidemiological correlates and mental health in children and adolescents. In part I we briefly describe the latest scientific insights regarding resilience and in part II we present a selected review of recent studies on resilience and mental health outcomes. We have conducted a systematic literature search (search period: January 2020–May 2021; for search strategy see Supplementary Material). Studies were included if they reported on resilience (measured with a resilience scale) [6▪,7]; mental health in children aged 0–18 years, clinical or epidemiological correlates of resilience and N at least 100.

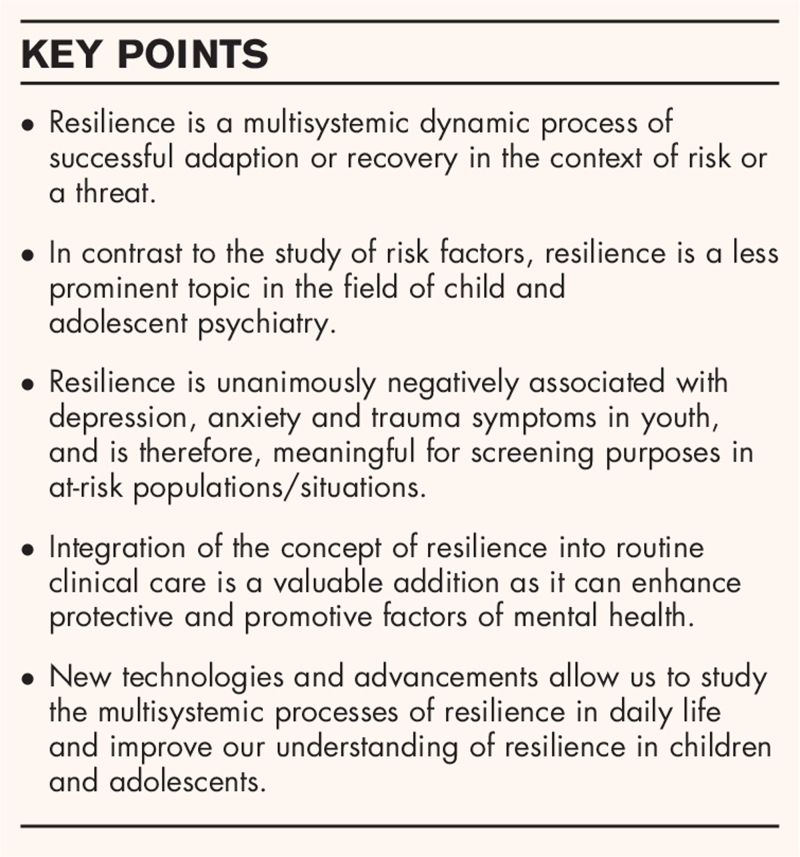

Box 1.

no caption available

PART I: RESILIENCE SCIENCE

Two recent reviews describe the emergence of current theories, models, methods and challenges in the field of resilience science in relation to mental health [8▪▪] and from a developmental perspective [9▪▪]. Accordingly, resilience is best defined as a multisystemic dynamic process of successful adaption or recovery in the context of risk or a threat. In essence, there are two main components of resilience: risk or threats to the person or system (e.g. maltreatment, natural disasters, mental illness in parents) and criteria by which successful adaption or recovery is evaluated (e.g. physical health or subjective wellbeing). Both authors argue that too often mental health studies on promotive or protective factors in relation to mental health and wellbeing focus on adaptive psychological systems alone, such as coping or self-regulation, without taking into account the instability of the different physical and social ecological systems, which is referred to as the multisystem approach [8▪▪,9▪▪]. For an example of these multiple systems in a developmental framework, we refer to Masten's shortlist of resilience in Table 1. Additionally, apart from processes and systems of resilience at the individual, social and ecological level, also neurobiological processes, such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis system reflecting the biology of stress and self-regulation, are important.

Table 1.

Masten's shortlist of multisystem resilience factors

| Sensitive caregiving, close relationships, social support; |

| Sense of belonging, cohesion; |

| Self-regulation, family management, group or organization leadership; |

| Agency, beliefs in system efficacy, active coping; |

| Problem-solving and planning; |

| Hope, optimism, confidence in a better future; |

| Mastery motivation, motivation to adapt; |

| Purpose and a sense of meaning; |

| Positive views of self, family, or group; |

| Positive habits, routines, rituals, traditions, celebrations. |

Reproduced with permission from Masten et al.[9▪▪].

Historically, assessment of resilience has been challenging. Early research focused on separate aspects of resilience, such as family support; however, an overarching concept was lacking. Current resilience measures reflect an aggregate of those aspects [9▪▪]; however, measures of resilience in children and adolescents are scarce [6▪,7]. Importantly, resilience is not simply the absence of psychopathology but a construct that reflects dynamic adaptation to adversity that can change over time [10]. This underscores the importance of longitudinal research. Advances in assessment methods [e.g. experience sampling methods (ESM)] and modelling (e.g. residualized approach [11], network modelling [12]) will improve our understanding of the cascade effects of a stressor in relation to resilience and mental health [9▪▪].

PART II: SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE SEARCH

Our systematic search resulted in 681 studies. In total, we included 25 original studies (see Table 2). We thematically organized studies based upon population or risk. There was heterogeneity in the assessment of resilience and study populations. Four studies had a longitudinal design. Only, two studies included children with a mean age below 12 years.

Table 2.

Overview of selected original studies

| Theme | Population | Country of origin | N | Age range | Mean age (SD) | Study design | Resilience instrument | Outcome |

| General population | ||||||||

| Chung et al.[15] | Adolescents | Hong Kong | 1816 | 11–15 | NA | Cross-sectional | Resilience Scale-14 | Depressive symptoms |

| Finch et al.[17] | Adolescents | Australia | 456 | 9–14 | 11.54 | Cross-sectional | Child and Youth Resilience | Depressive, anxiety symptoms and flourishing |

| Gong et al.[13▪] | Adolescents from nine schools in Wuhan | China | 6019 | 10–17 | NA | Cross-sectional | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | Depressive symptoms |

| Lee et al.[14▪▪] | Adolescents 10th–12th grade | Taiwan | 450 | NA | NA | Cross-sectional | Inventory of Adolescent Resilience | Depressive symptoms |

| Xiong et al.[16] | Adolescents | China | 1473 | 12–18 | 15.28 | Cross-sectional | Positive PsyCap Questionnaire | Anxiety/Depression |

| Adverse childhood experiences and negative life events | ||||||||

| Askeland et al.[26▪] | Population-based sample | Norway | 9546 | 16–19 | 17.4 | Cross-sectional | Resilience Sale for Adolescents | Depressive symptoms |

| Elmore et al.[20▪] | Population-based sample | USA | 40 302 | 8–17 | NA | Cross-sectional | HOPE framework, 5 independent resilient factors: child resilience, after school activities, family problem solves together, family remains hopeful, other adult factor | Depression |

| Hall et al. (2021) [19] | Youth presenting at a preventive care visit at urban academic pediatric practice | USA | 450 | 12–18 | 14.9 | Cross-sectional | Child Youth Resilience measure | Poor health outcome; depression, obesity, hypertension |

| Hamby et al. (2020) [23] | Community sample | USA | 440 | 10–21 | 16.38 | Cross-sectional | Resilience Portfolio Model | Trauma symptoms |

| Konaszewski et al.[27] | Youth sent to educational centers by a family court | Poland | 253 | 13–18 | 16.3 | Cross-sectional | Resilience Scale | Mental wellbeing |

| Kwon et al.[25] | Adolescent school dropouts | Korea | 278 | 14–19 | NA | Longitudinal | Ego-Resiliency scale | Depressive symptoms |

| Racine et al.[18▪] | Children referred to a Child Abuse Service | Canada | 176 | 3–18 | 10.45 | Retrospective file review | The Child and Youth Resilience Measure | Child trauma-related distress |

| Wei et al. (2021) [24] | Students from five elementary school and four middle schools | China | 6510 | 10–17 | 12.6 | Cross-sectional | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | Depressive symptoms |

| Zhao et al. (2020) [21▪] | Middle school students from five schools | China | 742 | 11–19 | 14.32 | Cross-sectional | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | Depression and school bullying victimization |

| Zhao et al. (2020) [22▪] | Left behind children recruited at two rural junior middle schools | China | 345 | 12–17 | 14.31 | Cross-sectional | Healthy Kids Resilience Assessment; | Depressive symptoms |

| Natural disasters | ||||||||

| An et al.[28▪▪] | Adolescents from two middle schools who were exposed to the Yancheng tornado | China | 121 | 12–19 | 14.04 | Longitudinal study | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | PTSD |

| Fuchs et al.[32] | Adolescents from Louisiana area who were exposed to both Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Oil Spill | USA | 1268 | 14–18 | 15.6 | Cross-sectional | Masten's short list for resilience | Risky substance use behavior, posttraumatic stress and depression |

| Liang et al.[31] | Students in grade 5–7 after Lushan Earth Quake | China | 102 | NA | 12.59 ± 1.13 | Longitudinal Study | Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale | Posttraumatic stress |

| Liu et al.[29▪▪] | Students from the most and least severe damaged school after the Wenchuan earthquake | China | 1015 | 10–15 | 12.7 | Longitudinal study | Block and Kremen's Ego-Resiliency Scale | Common mental health problems |

| Shi et al.[30] | Wenchuan Earthquake Adolescent Health Cohort | China | 1266 | NA | 15.98 ± 1.28 | Cross-sectional | Resilience Scale | PTSD, depression, anxiety |

| War | ||||||||

| Wilson et al.[33▪] | Palestinian refugee children living in a refugee camp | Palestina | 106 | 11–17 | NA | Cross-sectional | Child- and Youth Resilience Measure | Emotional, behavioral and psychosomatic problems |

| Dehnel et al.[34] | Syrian refugee children | Jordan | 339 | 10–17 | 13.4 | Cross-sectional | Child and Youth Resilience Measure | Depressive symptoms |

| COVID-19 pandemic | ||||||||

| Cusinato et al.[36] | Parents and children, community sample | Italy | 463 | 5–17 | NA | Cross-sectional | Child- and Youth Resilience Measure | Children's wellbeing |

| Yu et al.[37] | High school students | China | 430 | 15–22 | 18.51 | Cross-sectional | Brief Resilience Scale | Depression and anxiety symptoms |

| Wang et al.[38] | High school students from two schools | China | 1488 | 12–16 | 13.85 | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire of Adolescent Emotional Resilience | Intrusive rumination |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; NA, information not available.

General population

Five cross-sectional studies have investigated resilience in children and adolescents from the general population [13▪,14▪▪,15–17]. These studies showed that higher levels of resilience were related to depressive and/or anxiety symptoms. One study investigated the relationship between personality traits, resilience and depressive symptoms in 6019 high school students [13▪]. They found a moderating and mediating effect of resilience, and concluded that resilience may decrease the negative effect of neuroticism, and enhance the positive effect of extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness on depressive symptoms. Others investigated resiliency over multiple systems, such as family, school, peers [14▪▪,15,16]. Poorer quality in interpersonal relationships (with a parent, teacher, or peers) was related to mental health problems in children. Moreover, better interpersonal relationships were related to higher levels of resilience, which were related to fewer depressive symptoms [14▪▪]. Chung et al.[15] also found that living with a single parent was associated with lower resilience, which in turn was associated with higher levels of depression. Additionally, a study in 1473 high school students found that a construct of psychological capital (including hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism) buffered the influence of cumulative risk (an index of youth adjustment, family, school, peer and neighborhood aspects) on anxiety and depression symptoms but not life satisfaction [16]. Interestingly, a study in 456 high school students found that psychological capital was also positively related to flourishing. Furthermore, they found that the construct of psychological capital was a better predictor than the individual constructs, which shows the strength of combining different components that are related to resilience [17].

Adverse childhood experiences and negative life events

Nine cross-sectional studies and one longitudinal study examined resilience and psychopathology in the context of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and negative life events [18▪,19,20▪,21▪,22▪,23,24,25,26▪,27]. Overall, these studies show that higher levels of resilience are associated with mental health.

Five studies demonstrated the importance of investigating different components of resilience – for example, individual, relationship with a caregiver and educational support – in relation to ACEs and mental health in children and adolescents [18▪,19,20▪,23,24]. A retrospective file review in 176 children referred to a Child Abuse Service [18▪] found that protective factors (individual items: personal skills, peer support and social skills; caregiver: physical and psychological caregiving; and context: educational support) moderated the association between adversity and trauma-related distress. Notably, children who were exposed to higher levels of adversity had fewer protective factors. Another study in 450 youth who had experienced trauma and came to a preventive care visit, observed an inverse relationship of resilience and trauma [19] and found lower levels of resilience, in particular, relationship with caregiver, to be associated with poor health outcomes (obesity, hypertension or depression). In the National Survey of Children's Health [20▪] in 40 302 children, absence of child emotional resilience and lack of family problem-solving skills and hopefulness in the family, were significantly associated with depression. These effects were stronger in children experiencing more ACEs. In contrast, a study among 440 adolescents focusing on trauma symptoms, adversity and a range of psychological and social strengths, found that sense of purpose was the only unique contributor to lower trauma levels [21▪]. Social strengths did not add to this association.

One study reported on childhood maltreatment, resilience and gender specifically [22▪]. They found that the moderating effect of resilience on emotional abuse and depression was stronger in girls than boys.

Two studies investigated resilience and school-related events. Zhao et al[21▪]. studied school-bullying in 742 adolescents, and found that interpersonal relationship risks (with parents, classmates and teachers) were associated with lower individual resilience and higher risk of being bullied and depression [23]. The second study investigated 278 drop-out students over a period of 4 years [25]. They showed a dynamic course of perceived social stigma, depression and ego-resilience levels. An increase of social stigma over time was associated with higher levels of depression and lower ego-resilience. Initial and changes over time in ego-resilience mediated the relation between social stigma and depression.

One study investigated negative life events (e.g. violence from grown-ups, catastrophes, death of someone close to you), depressive symptoms and resilience in 9546 adolescents [26▪]. Resilient factors – that is, goal orientation, self-confidence, social competence, social support and family cohesion – were independently of life events all negatively associated with depressive symptoms, illustrating a compensatory effect. Also, a protective effect was found for goal orientation and self-confidence by showing lower depressive symptoms in adolescents who reported more negative life events.

Last, one study investigated the relationship of resilience with coping strategies in the context of negative life evens. In 253 juveniles sent to educational centers by a family court [27], resilience significantly predicted coping strategies, in particular active coping and seeking support from others. In addition, the relationship between resilience and mental wellbeing was mediated by seeking support from others and coping through discharging negative emotions.

Although these studies on resilience after ACEs and negative life events differ greatly in instruments, study design, type of adversity and outcome measures, they demonstrate that resilience is indeed a complex multisystemic dynamic process.

Natural disasters

Five studies investigated resilience and psychopathology in children and adolescents who had experienced a natural disaster [28▪▪,29▪▪,30–32]. All studies showed that higher levels of resilience were related to fewer mental health problems. Two longitudinal studies will be discussed in detail [28▪▪,29▪▪]. In the first study, 246 adolescents were assessed 6, 9, 12 and 18 months after the Yancheng tornado [28▪▪]. Six to nine months after the disaster, a decline of resilience was reported, with a gradual increase after 9 months. Furthermore, individuals with lower levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) 6 months after the tornado reported higher levels of resilience. Individuals for whom the PTSS severity decreased more quickly in 6–12 months also reported more rapid increase in resilience in 9–18 months, which shows that resilience is dynamic and takes time. Recovery of PTSS was associated with a steeper increase of resilience. Looking at timing of recovery, changes in PTSS and resilience occurred just after restoration of schools and homes, underscoring the importance of the multisystemic approach. The second study investigated the relationship between self-esteem, resilience, social support and mental health in 1015 adolescents 2 years after the Wenchuang earthquake [29▪▪]. Self-esteem and common mental health problems had a mutual negative effect on each other, whilst self-esteem and resilience positively affected each other. Social support had a promoting effect on self-esteem and resilience and a buffering effect against mental health problems. Moreover the study illustrated that all these aspects fluctuated over time. Other cross-sectional studies found that maternal parenting styles were significant predictors of resilience after earthquake experiences [30]; a positive association between PTSS, creative thinking and resilience were possible manifestations of posttraumatic growth [31]. Moreover, one study found that resilience mediated the association between depression and risky substance use behavior after natural disasters [32].

War

Two cross-sectional studies reported on resilience in children and adolescents living in refugee camps [33▪,34]. One study illustrated that resilience among 106 children and adolescents in refugee camps was positively associated with perceived level of community support, spiritual, cultural and educational resources [33▪]. The authors underscore that in addition to a universal approach in resiliency programs, the context must be prioritized as well. Another study in 339 children and adolescents reported that higher levels of resilience were related to fewer symptoms of depression but that prior trauma was not associated with resilience [34], which may reflect the dynamic process of resilience.

Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a global threat for public mental health. The pandemic exposes the underlying causes of insecurity, social and economic consequences, and thus challenges the multiple systems contributing to resilience [35]. Indeed, there appears a steep rise in mental health problems in youth [2▪]. Thus far, three cross-sectional studies have investigated resilience and mental wellbeing among children and adolescents during the pandemic [36–38]. An Italian study in 463 families during the first COVID-19 wave found a positive association between the child's resilience and wellbeing. Also more parental stress was related to lower levels of resilience in offspring [36]. Another study among 430 Chinese adolescents and the perceived impact of the pandemic showed both psychological distress and posttraumatic growth. Resilience and meaning in life served as protective factors for mental health [37]. Furthermore, in a study in 1488 Chinese teenagers, creative ideational behavior was positively related to intrusive rumination during the pandemic [38]. Interestingly, like Liang et al.[31], resilience and creativity were associated. In this study, the relationship between creativity and intrusive rumination was stronger in students with low levels of emotional resilience as compared with students with high levels of emotional resilience.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In this selected review, we discussed the recent literature on resilience, mental health and its correlates in children and adolescents up to 18 years old. Despite the heterogeneity between studies because of differences in instruments and study populations, all studies consistently show that higher levels of resilience are related to fewer mental health problems. Moreover, multiple factors, such as personal skills, social skills, peer support, school environment, contact with peers, parent–child relationship, family problem-solving, parental resilience, parental stress and goal orientation were related to resilience and demonstrate the importance of a multisystemic approach including social, cultural and family context in the study of resilience.

This review underscores that the construct of resilience is essential in the study of risk for psychopathology. However, the majority of the studies in this review were cross-sectional and did not measure resilience or psychopathology over time. As resilience is a dynamic process, longitudinal studies are essential [10]. Therefore, we argue that prospective studies on the influence of both risk and resilience in children and adolescents are needed.

The study of resilience can inform researchers and clinicians on targets for screening, intervention and preventive strategies. As higher levels of resilience are clearly associated with wellbeing in the child, and the context plays a significant role, we strongly encourage to incorporate the assessment of resilience in standard clinical care. Children and families with lower levels of resilience may be in need of other therapeutic support and more close monitoring compared with those with higher levels of resilience and a stable and supporting environment.

Over the past two decades, our research group has extensively studied intergenerational transmission of psychopathology in offspring of patients with severe mood disorders and psychotic disorders [1,3,39]. To advance our understanding of the development of psychopathology and to accommodate the growing need from clinicians and patients’ organizations for tools to promote resilience and increase wellbeing in children and adolescents, our mission has expanded from identification of risk factors of psychopathology to understanding how protective factors are related to wellbeing and daily life functioning. This has resulted in the development of new, online preventive intervention tools for children and adolescents at increased risk of psychopathology. An example of this is the Grow it! App, a gamified smartphone application, which monitors emotions, thoughts and behaviors in daily life (using ESM), and offers daily challenges using cognitive behavior therapy-based elements to promote adaptive coping. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Grow it! has been offered to individuals from the general population (aged 12–25 years) [40]. Currently, we are also studying the efficacy of this application in offspring of parents with mood disorders, and children with a chronic illness.

CONCLUSION

Resilience is a crucial aspect in the study of psychopathology in children and adolescents and should be studied in a multisystem approach, including individual, social, familial and cultural context. As resilience is a dynamic process that can change over time, there is a need for longitudinal studies that assess resilience and psychopathology in children and adolescents prospectively. An improved understanding of resilience factors might offer new targets both for clinical settings and for preventive and early intervention programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude towards Sabrina Meertens-Gunput from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing the search strategy. We thank Fleur Helmink, MSc for her contributions to the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

The current work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), project number: 606360098021 and 636320009.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Esther Mesman and Annabel Vreeker shared first authorship.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Mesman E, Nolen WA, Reichart CG, et al. The Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study: 12-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170:542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2▪.Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2021; 293:78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting the high prevalence of mental health problems in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was based upon 23 studies (China and Turkey) including 57 927 children and is the first to examine pooled prevalence of common mental health disorders early in the pandemic.

- 3.Maciejewski D, Hillegers M, Penninx B. Offspring of parents with mood disorders: time for more transgenerational research, screening and preventive intervention for this high-risk population. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2018; 31:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 197:378–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oldehinkel AJ, Ormel J. A longitudinal perspective on childhood adversities and onset risk of various psychiatric disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015; 24:641–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6▪.King L, Jolicoeur-Martineau A, Laplante DP, et al. Measuring resilience in children: a review of recent literature and recommendations for future research. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2021; 34:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review illustrates an overview of current approaches of measuring resilience in children and adolescents. The authors propose new complementary methods to include proactive behavior and observational indicators.

- 7.Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Quality Life Outcomes 2011; 9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8▪▪.Ungar M, Theron L. Resilience and mental health: how multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors provide a detailed overview on the latest findings on resilience and mental health. They argue that a multisystemic approach is necessary when in studies on resilience.

- 9▪▪.Masten AS, Lucke CM, Nelson KM, Stallworthy IC. Resilience in development and psychopathology: multisystem perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2021; 17:521–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; From a developmental perspective, the authors provide a detailed overview on the emergence of the current theories, models, methods, models, theories and challenges in the field of resilience science.

- 10.Kalisch R, Baker DG, Basten U, et al. The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nat Hum Behav 2017; 1:784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen JR, Choi JW, Thakur H, Temple JR. Psychological distress and wellbeing in trauma-exposed adolescents: a residualized, person-centered approach to resilience. J Trauma Stress 2020; 34:487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalisch R, Cramer AOJ, Binder H, et al. Deconstructing and reconstructing resilience: a dynamic network approach. Perspect Psychol Sci 2019; 14:765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13▪.Gong Y, Shi J, Ding H, et al. Personality traits and depressive symptoms: the moderating and mediating effects of resilience in Chinese adolescents. J Affective Disord 2020; 265:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this cross-sectional study, the relationship between personality traits, resilience and depressive symptoms is investigated in 6019 high school students. The authors demonstrate that resilience plays a significant role in the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms.

- 14▪▪.Lee TSH, Wu YJ, Chao E, et al. Resilience as a mediator of interpersonal relationships and depressive symptoms amongst 10th to 12th grade students. J Affective Disord 2021; 278:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of the first studies to illustrate the interrelation between interpersonal relationships and resilience in relation to depressive symptoms (n = 450, 10th–12th grade students). The study reports a partial mediation effect for resilience on the relation between interpersonal relationships and depressive symptoms, that is interpersonal relationships may increase resilience and decrease depression. Also family income and gender were important correlates.

- 15.Chung J, Lam K, Ho KY, et al. Relationships among resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J Health Psychol 2020; 25 (13–14):2396–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong JM, Hai M, Wang JT, et al. Cumulative risk and mental health in Chinese adolescents: the moderating role of psychological capital. School Psychol Int 2020; 41:409–429. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finch J, Farrell LJ, Waters AM. Searching for the HERO in youth: does psychological capital (PsyCap) predict mental health symptoms and subjective wellbeing in Australian school-aged children and adolescents? Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2020; 51:1025–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18▪.Racine N, Eirich R, Dimitropoulos G, et al. Development of trauma symptoms following adversity in childhood: the moderating role of protective factors. Child Abuse Negl 2020; 101:104375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A retrospective file review among 176 children referred to Child Abuse service examined whether protective factors (individual, caregiver and educational) moderated the relationship of childhood adversity and trauma-related distress symptoms.

- 19.Hall A, Perez A, West X, et al. The association of adverse childhood experiences and resilience with health outcomes in adolescents: an observational study. Glob Pediatr Health 2021; 8:2333794X20982433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20▪.Elmore AL, Crouch E, Kabir Chowdhury MA. The interaction of adverse childhood experiences and resiliency on the outcome of depression among children and youth, 8–17 year olds. Child Abuse Negl 2020; 107:104616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first national survey to study adverse childhood experiences, depression and resilience. The study found main and interaction effects illustrating that more adverse childhood experiences and low resilience increased the probability of developing self-reported depression.

- 21▪.Zhao Y, Zhao Y, Lee Y-T, Chen L. Cumulative interpersonal relationship risk and resilience models for bullying victimization and depression in adolescents. Pers Individ Diff 2020; 155:109706. [Google Scholar]; This cross-sectional study among 742 adolescents is one of the first studies to investigate resilience in the context of schoolbullying, interpersonal relationship risks. Resilience mediated the relationship between interpersonal risk factors and bullying, that is, interpersonal risk factors can lower individual resilience and increase the risk of being bullied and depression.

- 22▪.Zhao X, Fu F, Zhou L. The mediating mechanism between psychological resilience and mental health among left-behind children in China. Children Youth Services Rev 2020; 110:104686. [Google Scholar]; This is one of the first studies that examined the effect of psychological resilience on self-esteem and depression in left-behind children.

- 23.Hamby S, Taylor E, Mitchell K, et al. Poly-victimization, trauma, and resilience: exploring strengths that promote thriving after adversity. J Trauma Dissociation 2020; 21:376–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei J, Gong Y, Wang X, et al. Gender differences in the relationships between different types of childhood trauma and resilience on depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents. Prev Med 2021; 148:106523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon T. Social stigma, ego-resilience, and depressive symptoms in adolescent school dropouts. J Adolesc 2020; 85:153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26▪.Askeland KG, Bøe T, Breivik K, et al. Life events and adolescent depressive symptoms: protective factors associated with resilience. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0234109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study illustrated among 9546 adolescents aged 16–19 years that the association between negative life events and more depressive symptoms. Protective effects were found for self-confidence and family cohesion. The large sample size allowed to investigate interaction effects and the relative contributions of protective factors.

- 27.Konaszewski K, Niesiobędzka M, Surzykiewicz J. Resilience and mental health among juveniles: role of strategies for coping with stress. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2021; 19:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28▪▪.An Y, Sun X, Le Y, Zhou X. Trajectory and relation between posttraumatic stress disorder on resilience in adolescents following the Yancheng tornado. Pers Individ Diff 2020; 164:110097. [Google Scholar]; In this longitudinal study, 246 adolescents were followed up to 18 months after the Yancheng Tornado. This study illustrates that both resilience and posttraumatic stress symptoms follow a dynamic course and recovery of PTSS and resilience are intertwined. Also, context was seemingly important as changes in PTSD symptoms and resiliency took off after restoration of schools, homes.

- 29▪▪.Liu Q, Jiang M, Li S, Yang Y. Social support, resilience, and self-esteem protect against common mental health problems in early adolescence: a nonrecursive analysis from a two-year longitudinal study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021; 100:e24334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Five repeated measurements over 2 years among 1015 adolescents (mean age 12.7 years) living in the Whenchuan Earthquake areas illustrated that selfesteem and mental health problems have a mutual negative effect on each other.

- 30.Shi X, Wang S, Wang Z, Fan F. The resilience scale: factorial structure, reliability, validity, and parenting-related factors among disaster-exposed adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 2021; 21:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang YM, Zheng H, Cheng J, et al. Associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms, creative thinking, and trait resilience among Chinese adolescents exposed to the Lushan Earthquake. J Creative Behav 2021; 55:362–373. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs R, Glaude M, Hansel T, et al. Adolescent risk substance use behavior, posttraumatic stress, depression, and resilience: Innovative considerations for disaster recovery. Subst Abus 2020; 1–8. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33▪.Wilson N, Turner-Halliday F, Minnis H. Escaping the inescapable: risk of mental health disorder, somatic symptoms and resilience in Palestinian refugee children. Transcult Psychiatry 2021; 58:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This cross-sectional study among 106 Palestinian refugee children confirm the negative association between resilience and mental health and that resilience was significantly associated with contextual factors, such as perceived level of community support, spiritual, cultural and educational resources.

- 34.Dehnel R, Dalky H, Sudarsan S, Al-Delaimy WK. Resilience and mental health among Syrian refugee children in Jordan 2021; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, et al. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res 2020; 293:113429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cusinato M, Iannattone S, Spoto A, et al. Stress, resilience, and wellbeing in Italian children and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y, Yu Y, Hu J. COVID-19 among Chinese high school graduates: psychological distress, growth, meaning in life and resilience. J Health Psychol 2021; 1359105321990819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, Zhao X, Yuan YM, Shi BG. The relationship between creativity and intrusive rumination among Chinese teenagers during the COVID-19 pandemic: emotional resilience as a moderator. Front Psychol 2021; 11:601104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Haren NEM, Setiaman N, Koevoets MGJC, et al. Brain structure, IQ, and psychopathology in young offspring of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2020; 63:e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dietvorst E, Aukes MA, Legerstee JS, et al. A serious-gaming mobile app to identify emotional problems and promote adaptive coping in adolescents: Grow It! Under review. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.