Abstract

A health care provider’s vaccination recommendation is one of the most important factors influencing parents’ decisions about whether to vaccinate their children. Unfortunately, vaccine hesitancy is associated with mistrust of health care providers and the medical system. We conducted a survey of 2,440 adults through the RAND American Life Panel in 2019. Respondents were asked to rate their trust in pediatricians, OB/GYNs, doulas, midwives, lactation consultants, friends and family for information about childhood vaccines. Respondents were also asked about willingness to vaccinate a hypothetical child as a measure of vaccine hesitancy. We used principal component analysis to characterize variance in responses on trust items and logistic regression to model the relationship between trust and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy was associated with: (1) lower overall trust; (2) reduced trust in OB/GYNs and pediatricians and greater trust in doulas, midwives, and lactation consultants; and (3) greater trust in friends and family.

Introduction

Childhood vaccines are safe and effective at preventing disease, [1] yet vaccine hesitancy remains a concern.[2] A health care provider’s vaccination recommendation is one of the most important factors influencing parents’ decisions about whether to vaccinate their children.[3] Unfortunately, vaccine hesitancy is associated with mistrust of health care providers and the medical system.[3,4] As a result, the relationship between trust in one’s own health care provider and decision to vaccinate among those who are hesitant is unclear. Most research on the association between trust in the medical system and parental vaccine hesitancy decisions consider providers as a homogeneous group.[5–7] Parents also often turn to friends and family as sources of information about childhood vaccinations.[7] In this study, our objective was to assess the relationship between vaccine hesitancy and trust in different types of health care providers as well as friends and family. Given that pregnancy and the first few months of an infant’s life are critical times for decision making around vaccines, the health providers we focused on were birth practitioners -- those who specialize in providing care to women during pregnancy and the post-partum period, or to infants.

Methods

We conducted a survey through the RAND American Life Panel (ALP), a nationally representative empaneled sample of the adult U.S. population. The survey was fielded between August and September of 2019. 2,440 of 3421 invited panelists (71% participation rate) answered: “Please rate how much you trust the advice of these individuals about childhood vaccinations”, with response options “distrust a lot”, “distrust”, “distrust a little”, “neither trust nor distrust”, “trust a little”, “trust”, and “trust a lot”, coded 1–7. Rated groups included five types of birth practitioners (obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYNs), midwives, lactation consultants, doulas, and pediatricians), as well as friends and family members. Finally, we asked, “We would like you to think about a child who is due to receive vaccinations, such as your child, grandchild, niece or nephew, or some other child you know. How likely would you be to fully vaccinate them based on the current recommended national vaccine schedule?” Response options were: “very unlikely”, “unlikely”, “slightly unlikely”, “equally likely”, “slightly likely”, “likely”, and “very likely”, coded 1–7. Previous studies have used a similar “intent to vaccinate” question to assess vaccine hesitancy.[8] We conducted an additional survey and analysis on a sample of parents from the ALP using reported vaccination behavior as our measure of vaccine hesitancy. The results from this analysis, which provided convergent results, are presented in the supplementary material.

We first divided the sample into a vaccine hesitant group and a non-hesitant group. Vaccine hesitancy was defined as selecting any of the “unlikely” responses (1 to 3) when reporting willingness to vaccinate a hypothetical child; all other responses were coded as non-vaccine hesitant. We then identified the groups (pediatricians; OB/GYNs; doulas; lactation consultants; midwives; family; friends) to which each individual gave their highest and lowest trust ratings. If an individual gave more than one group their highest (or lowest) trust score, all such groups were considered the most (or least) trusted for that individual. We calculated the percentage of vaccine hesitant and non-vaccine hesitant respondents who rated each group as their most and least trusted source of information about childhood vaccines. These analyses describe univariate patterns of trust based on groups of individuals. Second, we used principal component analysis (PCA) to assess the covariation in trust for all seven groups. This enabled us to identify the way respondents may bin the groups into broader categories. Third, we used logistic regression to model vaccine hesitancy (dependent variable) as a function of the scores on the dominant principal components and demographic variables. Principal component scores were standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

Results

Table 1 describes sample demographic characteristics, and the mean and standard deviations for the trust and intention to vaccinate a hypothetical child. The average age was 58 years; 57% were female; and 52% had at least a bachelor’s degree. Eighty percent were White, 10% Black/African American, and the rest Indigenous, Asian or Pacific Islander, or another race. Thirteen percent of the sample was Hispanic. Mean trust was highest for pediatricians (6.2), falling between “trust” and “trust a lot” on the 7-point scale. OB/GYNs were also highly trusted (mean=5.8). All remaining trust scores ranged between “neither trust nor distrust” (4) and “trust” (5). The average respondent reported a vaccine intent of 6.2, falling between “likely” and “very likely” to vaccinate a hypothetical child.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables and key variables of interest. The trust and vaccine intent measures are reported on a 7 point Likert scale with 1 representing “distrust a lot” and “very unlikely” on the two measure types and 7 representing “trust a lot” and “very likely”.

| Overall | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| n | 2440 |

|

| |

| Demographics | |

|

| |

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 57.9 (13.9) |

| Sex = Female (%) | 1382 (56.6) |

|

| |

| Education (%) | |

| Less than high school | 65 (2.7) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 276 (11.3) |

| Some college, no degree | 509 (20.9) |

| Associate degree | 325 (13.3) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 661 (27.1) |

| Postgraduate degree | 604 (24.8) |

| Race(%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 1958 (80.2) |

| Black/African American | 246 (10.1) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 25 (1.0) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 71 (2.9) |

| Other | 140 (5.7) |

| Hispanic (%) | 330 (13.5) |

|

| |

| Trust Measures | |

|

| |

| Pediatrician Trust (mean (SD)) | 6.20 (1.2) |

| OB/GYN Trust (mean (SD)) | 5.81 (1.3) |

| Doula Trust (mean (SD)) | 4.06 (1.4) |

| Lactation Consultant Trust (mean (SD)) | 4.22 (1.5) |

| Midwife Trust (mean (SD)) | 4.24 (1.4) |

|

| |

| Family Trust (mean (SD)) | 4.82 (1.3) |

| Friends Trust (mean (SD)) | 4.63 (1.3) |

|

| |

| Vaccine Measures | |

|

| |

| Vaccine Intent (mean (SD)) | 6.20 (1.5) |

| Vaccine Hesitant (Vaccine Intent = 1, 2, or 3) (%) | 199 (8.2) |

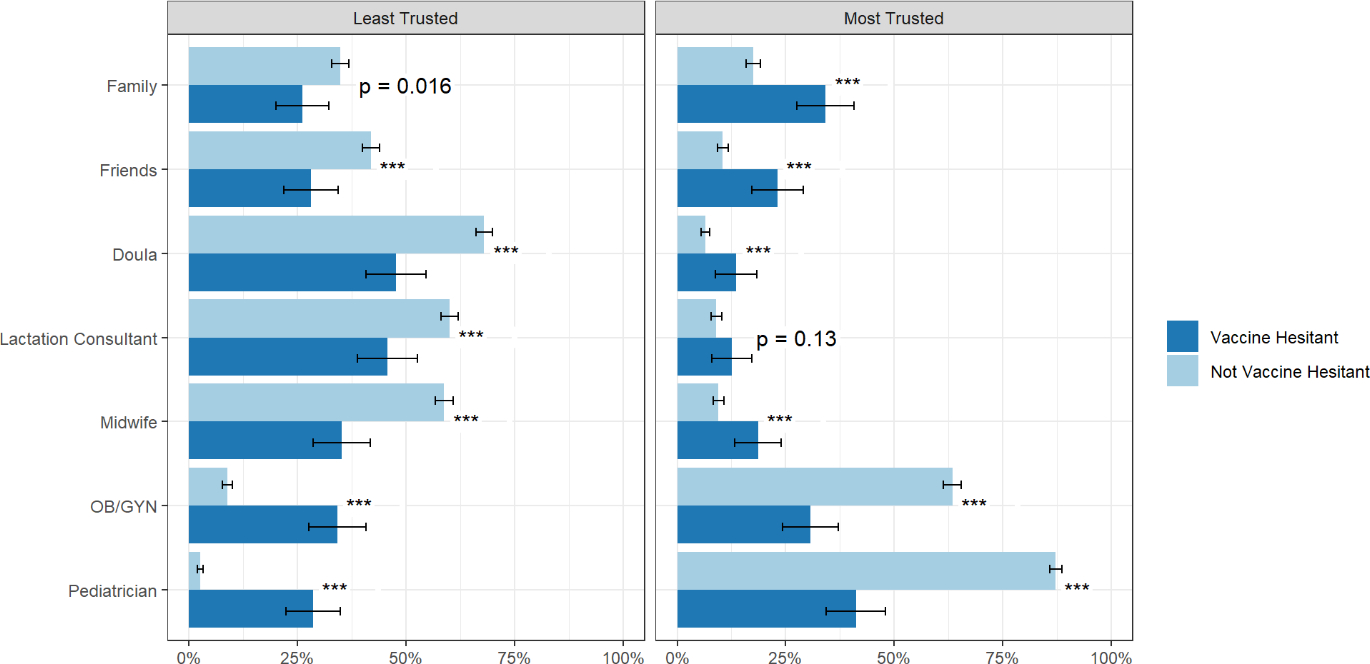

Non-vaccine hesitant respondents were more likely to rate pediatricians (87%) and OB/GYNs (63%) as most trusted than were vaccine hesitant respondents (42% and 31%, respectively; Figure 1). That said, vaccine hesitant respondents were still more likely to give their top score to pediatricians than to any other group. In contrast, friends, family, doulas, lactation consultants, and midwives were more likely to be most trusted by vaccine hesitant than by non-vaccine hesitant respondents. Whereas pediatricians and OB/GYNs were the least trusted for only 3% and 9% of non-vaccine hesitant respondents, these providers were the least trusted groups for more than a quarter of vaccine hesitant respondents (29% and 34%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Proportion of vaccine hesitant and non-vaccine hesitant respondents reporting each group as their most or least trusted source of information about childhood vaccines, based on ranked trust scores reported by each individual. Error bars show the estimated 95% confidence interval for each reported proportion. P-values are shown for differences in proportions calculated for the Vaccine Hesitant and Not Vaccine Hesitant groups. *** indicates a p-value <0.001.

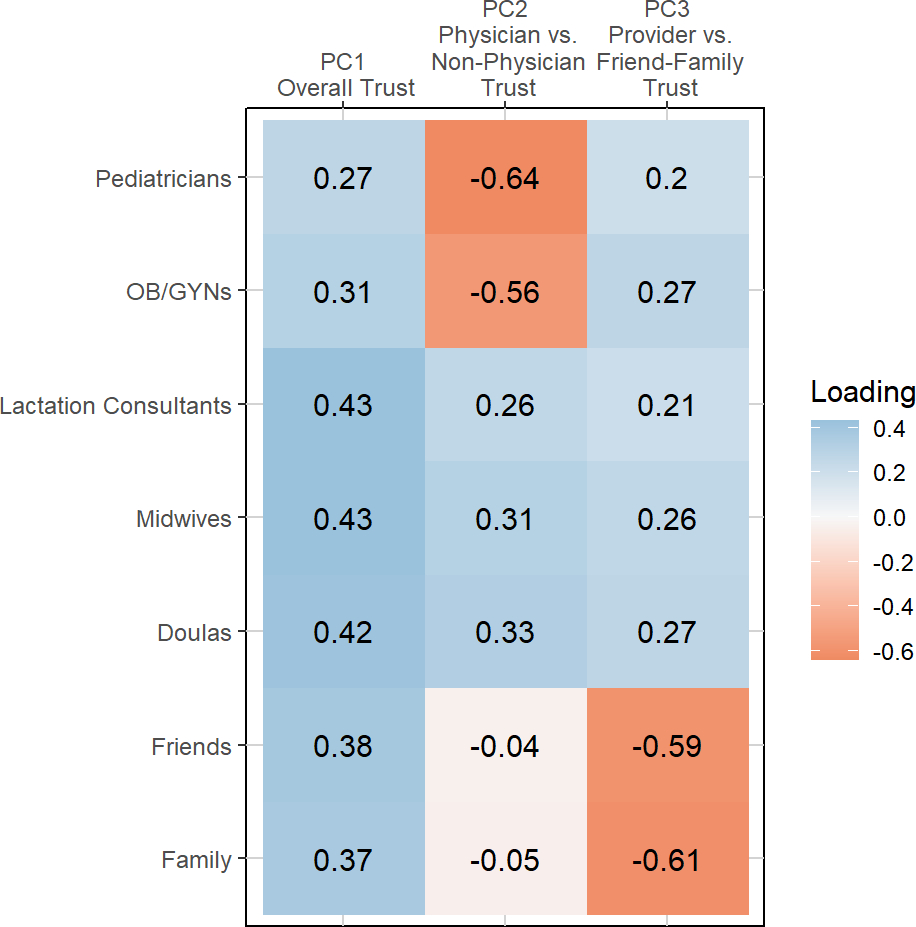

In a principal component analysis run on our seven trust survey items, the first three principal components explained 88.4% of the total variance in the seven items: 54.9%, 19.4%, and 14.1% respectively. The fourth principal component explained only 3.9% of the variance (the full scree plot is Figure S1 in the supplementary material). We use these three principal components in our remaining analysis.

Figure 2 shows the trust item loadings on these three principal components. All seven trust questions load in the same direction on the first component (0.27 to 0.43), reflecting a tendency for individuals to have either high or low overall trust across various information sources regarding childhood vaccines. The second principal component has negative loadings for pediatricians and OB/GYNs (−0.64 and −0.56), positive loadings for lactation consultants, midwives, and doulas (0.26 to 0.33), and small loadings for friends and family. This principal component appears to distinguish trust in physician birth practitioners from trust in non-physician birth practitioners. The third principal component has positive loadings (≥ 0.2) for all health care providers and negative loadings on friends and family, seemingly reflecting trust in health care providers versus trust in friends and family.

Figure 2:

Loadings on the first three principal components from the PCA analysis of seven trust items from our survey.

Table 2 presents a logistic regression model predicting vaccine hesitancy with respondents’ scores on the first three trust principal components (PC1 overall trust, PC2 non-physician vs. physician provider trust, PC3 provider trust vs. friends-family trust) and demographic variables. Principal component scores were normalized so that the standard deviation of each in our sample was 1. All three principal components were statistically significant predictors. Overall trust was associated with decreased vaccine hesitancy (odds ratio, OR = 0.65); trust in non-physician over physician providers was strongly associated with higher vaccine hesitancy (OR = 3.11), and trust in providers over friends-family was associated with decreased vaccine hesitancy (OR = 0.83). None of the demographic variables were significant at the p<0.05 level.

Table 2.

Results from a logistic regression model predicting vaccine hesitancy. In this model, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity was a binary variable separate from the other (mutually exclusive) race categories. Principal component scores (PC1, PC2, and PC3) were normalized so that the standard deviation of each in our sample was 1. Reported effect sizes therefore represent the effect of an increase in the score of one standard deviation.

| Variable | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.02 [0, 0.27] | 0.0027 |

| PC1 (overall trust) | 0.65 [0.55, 0.76] | <0.001 |

| PC2 (non-physician vs. physician trust) | 3.11 [2.59, 3.73] | <0.001 |

| PC3 (provider vs. friend-family trust) | 0.83 [0.7, 0.99] | 0.035 |

| Age (in years) | 1 [0.99, 1.01] | 0.87 |

| Sex | 1.21 [0.85, 1.72] | 0.28 |

| Education (Reference = Less than high school) | ||

| Some high school, no diploma | 2.89 [0.28, 30.2] | 0.38 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 2.29 [0.24, 21.85] | 0.47 |

| Some college, no degree | 1.76 [0.19, 16.5] | 0.62 |

| Associate degree | 1.94 [0.2, 18.51] | 0.56 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1.58 [0.17, 15.03] | 0.69 |

| Master’s degree | 1.66 [0.17, 16.07] | 0.66 |

| Professional school degree | 2.62 [0.24, 28.29] | 0.43 |

| Doctorate degree | 1.32 [0.11, 15.75] | 0.83 |

| Race (Reference = White) | ||

| Black/African American | 1.13 [0.7, 1.83] | 0.61 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1.79 [0.47, 6.79] | 0.39 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.85 [0.3, 2.37] | 0.76 |

| Other | 0.49 [0.23, 1.08] | 0.079 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.65 [0.37, 1.14] | 0.13 |

We replicated the complete analysis just described for a parent sample that reported vaccination behavior rather than hypothetical intent to vaccinate (Supplement). The results were highly consistent with those presented from the broader ALP sample, which suggests these findings are robust to variation in the form of vaccine hesitancy measurement and to variations in the sampled population.

Discussion

In a principal component analysis, we found that the second principal component, PC2, which comprised 19% of the overall variance, had positive loadings on doula, midwife, and lactation consultant items and negative loadings on pediatrician and OB/GYN trust items. Furthermore, PC2 scores were positively associated with vaccine hesitancy (3.11 [2.59, 3.73]).

While we used the labels “physicians” and “non-physicians” to describe these groupings for parsimony, we note that lactation consultants, doulas and midwives may also be viewed as less associated with the medical establishment than are pediatricians and OB/GYNs. Lactation consultant certifications were created in the context of efforts to “reverse the effects of medicalization” on childbirth and breastfeeding.[9] Midwifery has a similar history. The field preceded modern medicine and its use declined from the late 19th to early 20th centuries when physicians attending births became the norm.[10] Midwife certifications arose partly as a way to integrate the midwife profession into the medical system. [11] A recent review found that complementary and alternative medical practices are widely supported by midwives.[12] In addition, doulas often serve a role complementary and separate from physicians and nurses in the delivery room.[13] Prior evidence has shown that mistrust in the medical system is associated with vaccine hesitancy,[4] which may partly explain why these professions that evolved separately from the medical system but were later integrated with it, are viewed differently than pediatricians and OB/GYNs.

These results suggest that when it comes to childhood vaccination decisions, there may be multiple facets to medical provider trust. As such, it may be important to separately consider trust in physician and non-physician health care providers, or in providers that are viewed as more or less integrated with the medical establishment. On the other hand, in descriptive analyses, we found that pediatricians and OB/GYNs were the most trusted source of information about childhood vaccines for many vaccine hesitant respondents (42 percent and 31 percent for pediatricians and OB/GYNs). Pediatricians were most trusted by more vaccine hesitant respondents than any other group we asked about. In line with these descriptive analyses, we found that PC1, comprising 55% of the total variance, reflected a general propensity to trust any and all sources of vaccine information. Higher scores on PC1 (greater general trust) was associated with less vaccine hesitancy in the regression results. We found a strong association between trust in non-physician birth practitioners (lactation consultants, doulas, and midwives) relative to physicians (pediatricians and OB/GYNs) and vaccine hesitancy.

The relationship between vaccine beliefs, cultural identity, and trust is complex,[14,15] and we cannot infer causality from our results. For example, we found relatively lower trust in pediatricians and OB/GYNs among vaccine hesitant individuals compared to those who are not vaccine hesitant. Mistrust could precede vaccine hesitancy, and individuals could be skeptical of vaccines advocated by those they mistrust; or, vaccine hesitant beliefs could lead to lower trust in pediatricians and OB/GYNs. Alternatively, vaccine hesitancy and relative mistrust of pediatricians and OB/GYNs could both arise from identification with less medicalized forms of health care.

Taken as a whole, our results suggest that vaccine hesitant individuals are more heterogeneous and overall less trustful than non-vaccine hesitant respondents in their relative trust in medical providers, friends, and family, for information about childhood vaccination. They are also generally less trustful of any information source, which suggests the commonly recommended communication strategy of “finding a trusted messenger” faces inherent limitations for improving vaccine uptake. Among many of the vaccine hesitant, there simply is no trusted messenger, at least among the groups about which we asked. This observation is consistent with separate surveys we have conducted on political misinformation that have found many individuals who espouse political misinformation mostly distrust, rather than trust, all definable societal experts including doctors, scientists, journalists, and even religious and business leaders.[16] Interventions designed to increase the acceptability of childhood vaccines in vaccine hesitant individuals ought to consider a variety of messengers including non-physician health care providers, and community members including friends and family, but policy makers should be aware this strategy faces inherent limitations to its success with regard to the vaccine hesitancy problem. It is also important to appreciate the ability of physicians, including pediatricians and OB/GYNs, to address vaccine hesitancy. While these physician providers are not well-trusted by the vaccine hesitant, they are still often more trusted than other sources of information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Eunice Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in the National Institutes of Health (R21HD087749). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare and all authors attest that they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Human Subjects Review

This study was approved by the RAND Institutional Review Board, called the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee (HSPC). The approval letter stated: “On 9/12/2017, the Human Subjects Protection Committee (HSPC) approved the study referenced below in expedited review Category 7. In addition, the HSPC approved a waiver of documentation of consent under 45 CFR 46.117(c)(2). The HSPC determined that the study is minimal risk.” While documentation of consent was not required, participants in the RAND American Life Panel consent to participate in the panel through an annual survey question. Those who do not consent are not included in the survey panel.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Maglione MA, Das L, Raaen L, Smith A, Chari R, Newberry S, et al. Safety of vaccines used for routine immunization of US children: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014;134:325–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shrivastava SR, Shrivastava PS, Ramasamy J. The growing global problem of vaccine hesitancy: Time to take action. Int J Prev Med 2016;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wiley KE, Massey PD, Cooper SC, Wood N, Quinn HE, Leask J. Pregnant women’s intention to take up a post-partum pertussis vaccine, and their willingness to take up the vaccine while pregnant: A cross sectional survey. Vaccine 2013;31:3972–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hornsey MJ, Lobera J, Díaz-Catalán C. Vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with distrust of conventional medicine, and only weakly associated with trust in alternative medicine. Soc Sci Med 2020;255:113019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Soveri A, Karlsson LC, Mäki O, Antfolk J, Waris O, Karlsson H, et al. Trait reactance and trust in doctors as predictors of vaccination behavior, vaccine attitudes, and use of complementary and alternative medicine in parents of young children. PloS One 2020;15:e0236527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Quinn S, Jamison A, Musa D, Hilyard K, Freimuth V. Exploring the Continuum of Vaccine Hesitancy Between African American and White Adults: Results of a Qualitative Study. PLoS Curr 2016;8. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.3e4a5ea39d8620494e2a2c874a3c4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Larson HJ, Clarke RM, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Levine Z, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring trust in vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2018;14:1599–609. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1459252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014;133:e835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Torres JMC. Medicalizing to demedicalize: Lactation consultants and the (de)medicalization of breastfeeding. Soc Sci Med 2014;100:159–66. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Turner PK. Mainstreaming Alternative Medicine: Doing Midwifery at the Intersection. Qual Health Res 2004;14:644–62. 10.1177/1049732304263656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ettinger LE. Nurse-midwifery: the birth of a new American profession. The Ohio State University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hall HG, McKenna LG, Griffiths DL. Midwives’ support for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: a literature review. Women Birth J Aust Coll Midwives 2012;25:4–12. 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ballen LE, Fulcher AJ. Nurses and Doulas: Complementary Roles to Provide Optimal Maternity Care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35:304–11. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hornsey MJ, Edwards M, Lobera J, Díaz-Catalán C, Barlow FK. Resolving the small-pockets problem helps clarify the role of education and political ideology in shaping vaccine scepticism. Br J Psychol n.d.;n/a. 10.1111/bjop.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kahan DM. Misconceptions, Misinformation, and the Logic of Identity-Protective Cognition. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2017. 10.2139/ssrn.2973067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Matthews LJ, Parker AM, Carman KG, Kerber R, Kavanagh J. Individual Differences in Resistance to Truth Decay. In Revision.: n.d. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.