Abstract

Plant and animal lectins with various carbohydrate specificities were used to type 35 Irish clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori and the type strain NCTC 11637 in a microtiter plate assay. Initially, a panel of eight lectins with the indicated primary specificities were used: Anguilla anguilla (AAA), Lotus tetragonolobus (Lotus A), and Ulex europaeus I (UEA I), specific for α-l-fucose; Solanum tuberosum (STA) and Triticum vulgaris (WGA), specific for β-N-acetylglucosamine; Glycine max (SBA), specific for β-N-acetylgalactosamine; Erythrina cristagali (ECA), specific for β-galactose and β-N-acetylgalactosamine; and Lens culinaris (LCA), specific for α-mannose and α-glucose. Three of the lectins (SBA, STA, and LCA) were not useful in aiding in strain discrimination. An optimized panel of five lectins (AAA, ECA, Lotus A, UEA I, and WGA) grouped all 36 strains tested into eight lectin reaction patterns. For optimal typing, pretreatment by washing bacteria with a low-pH buffer to allow protein release, followed by proteolytic degradation to eliminate autoagglutination, was used. Lectin types of treated samples were stable and reproducible. No strain proved to be untypeable by this system. Electrophoretic and immunoblotting analyses of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) indicated that the lectins interact primarily, but not solely, with the O side chain of H. pylori LPS.

The widespread occurrence of the gastroduodenal pathogen Helicobacter pylori in the human population and the broad spectrum of clinical outcomes from this infection (5) have focused interest on differentiation of strains based on DNA typing methods (3, 7, 8, 15, 19) but also on phenotypic typing methods (1, 9, 16). Typing of bacterial strains based on differences in the structures of their lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) has proven valuable in typing members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. As H. pylori strains have been shown to exhibit mimicry of Lewis (Le) antigens in the O side chains of their LPSs (11, 16), a typing system based on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (16) utilizes this mimicry but has a number of limitations for epidemiological studies. First, the system is based upon differences in monoclonal antibody (MAb) recognition of a conserved set of Le antigens, suggesting a low level of discrimination in the system; second, a large number of untypeable strains occur (15%); and third, the technical expertise required to perform the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay limits the usefulness of such a system. Another phenotypic typing scheme which is based on hemagglutination of LPS exists for H. pylori (9) but again requires highly technical systems for antigen preparation and the use of antibodies raised in animals.

A simple, reproducible, and sensitive typing system which would not require the use of antibodies would be extremely valuable for epidemiological studies. It has been shown previously that the use of lectins can be a useful tool in differentiating strains of a variety of bacterial species (14). Lectins are animal or plant proteins or glycoproteins of nonimmune origin which possess binding specificities for various carbohydrates and have more stable storage properties than antibodies. The aim of our study was to develop, evaluate, and optimize the use of a panel of eight lectins for differentiating among H. pylori strains by using a technique based on agglutination in microtiter plates. A collection of H. pylori strains from a distinct geographical human population was used in testing since previous studies have shown differences in strains between populations (2).

(A preliminary report of this research was presented at the 3rd International Workshop on Pathogenesis and Host Response in Helicobacter Infections, Helsingør, Denmark, 1 to 4 July 1998.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultures and growth conditions.

A total of 36 H. pylori strains were used in this study: 35 clinical isolates of H. pylori (provided by D. Marshall, The Moyne Institute of Preventive Medicine, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland) and the type strain H. pylori NCTC 11637 (National Collection of Type Cultures, London, United Kingdom). Purity of cultures was established with the Gram stain and by urease, catalase, and oxidase tests (17). Strains were routinely cultured on Columbia agar (Oxoid, London, United Kingdom) with 7% horse blood and in GB broth (18) under humid microaerobic conditions for 48 h with a BR38 GasPak system (Oxoid). Cultures were maintained in Tryptone Soya broth (Oxoid) plus 20% (vol/vol) glycerol at −70°C.

Bacterial samples.

Biomasses were harvested from agar plates in 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.15 M NaCl (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) with 0.1% NaN3, centrifuged (3,000 × g, 10 min), and resuspended in 10 ml of PBS. Likewise, broth cultures were centrifuged, and the resultant pellets were washed once in PBS. Subsequently, biomasses were stored at 4°C for up to 2 weeks prior to use (13, 22).

Proteolytic degradation of bacterial biomass.

Stored samples were washed once in PBS, resuspended in 5 ml of PBS (pH 4), and incubated at 20°C for 30 min to induce autolysis of the cells and protein release. Subsequently, treated cells were washed twice in PBS, resuspended in 5 ml of PBS containing 0.1 mg of proteinase K (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml, incubated at 60°C for 1 h, and then heated to denature the enzyme (100°C, 5 min). Each suspension was centrifuged (5,000 × g, 15 min), and the resultant pellet of cell debris was resuspended in PBS to an A550 of 0.9 before lectin typing.

Representative strains were also tested as whole-cell samples in PBS (A550 of 0.9) in the lectin typing assay.

Lectin typing.

The following freeze-dried native lectins were purchased from Sigma and ICN Biomedicals (Cleveland, Ohio): Anguilla anguilla (AAA), Lotus tetragonolobus (Lotus A), and Ulex europaeus I (UEA I), specific for α-l-fucose; Solanum tuberosum (STA) and Triticum vulgaris (WGA), specific for β-N-acetylglucosamine; Glycine max (SBA), specific for β-N-acetylgalactosamine; Erythrina cristagali (ECA), specific for β-galactose and β-N-acetylgalactosamine; and Lens culinaris (LCA), specific for α-mannose and α-glucose. Lectins were dissolved in PBS containing 0.02% CaCl2 and 0.02% MgCl2 at a concentration of 0.5 mg per ml (1).

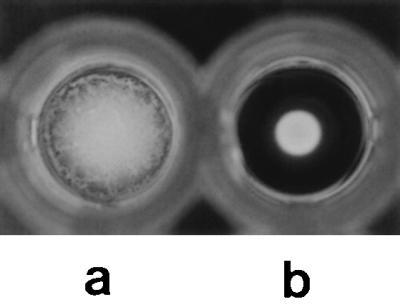

Bacterial samples (40 μl) were mixed with 10 μl of lectin solution (0.5 mg/ml) in U-shaped microtiter wells (Bibby Sterilin Ltd., Stone, United Kingdom) for 5 s or, alternatively, were mixed with 10 μl of PBS (negative control) and allowed to settle overnight, undisturbed, at 20°C. Results were read by visual inspection: a positive reaction was evidenced by a carpet of aggregated cells on the bottom of wells, and a negative reaction was evidenced by a dot of cellular material on the bottom of a well. Negative results were confirmed by tilting wells at an angle >45° and observing the movement of cellular material. As positive controls, lectins were shown to agglutinate a 0.75% suspension of human type O erythrocytes after incubation at 20°C for 2 h.

Protein concentration.

Protein concentrations of whole-cell samples and extracts were determined with a commercial assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.), with bovine serum albumin (Oxoid) as the standard.

SDS-PAGE, immunodot, and lectin dot analyses.

For analysis of O side chain expression on LPSs, proteolytically treated whole-cell lysates of H. pylori strains (4) and samples for lectin typing were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Electrophoresis was conducted with a constant current of 35 mA, a stacking gel of 4.5% acrylamide, and a separating gel of 15% acrylamide containing 3.2 M urea (ICN) (12). After SDS-PAGE, the gels were fixed and LPSs were detected by silver staining (20).

These preparations were also analyzed in an immunodot system in which samples (1 μl) were dotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham International, Amersham, United Kingdom) and probed with murine MAbs against Lex and Ley structures (Signet Laboratories, Dedham, Mass.) as the primary antibodies and with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate as the secondary antibody (Bio-Rad). Immunodots were visualized with an HRP substrate development kit (Bio-Rad). Furthermore, samples prepared for lectin typing were subjected to a lectin dot analysis in which samples (1 μl) were dotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and probed with Lotus A lectin-HRP conjugate (Sigma) and reactions were visualized as described for immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Effects of proteolytic treatment on H. pylori-lectin interaction.

The major effects of proteolytically treating H. pylori biomass prior to lectin typing is to enhance the clarity of negative and positive reactions in the agglutination assay and also to eliminate nonspecific agglutination in the control wells. The clear distinction between a positive and a negative result is shown in Fig. 1. Results for whole-cell samples which had proved untypeable through nonspecific agglutination in their control wells were typeable once they were proteolytically pretreated. Of five strains tested with whole-cell samples, four were untypeable due to autoagglutination in the control PBS well (Table 1). Proteolytic treatment of these samples led to loss of autoagglutination in PBS control wells and also to loss of reaction of some strains with lectins, suggesting nonspecific interaction of the strains with these lectins. None of the 36 tested strains had autoagglutination occurring in control wells when a pretreated extract was used for the lectin agglutination assay.

FIG. 1.

Representative results of the lectin agglutination assay. (a) Positive result; (b) negative result.

TABLE 1.

Representative results of autoagglutination of whole-cell samples and lectin typing after proteolytic treatment of H. pylori strains

| Lectin or PBS | Test result with indicated H. pylori strain

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97-f13

|

97-f30

|

97-f33

|

97-f34

|

97-f54

|

||||||

| WCa | PKb | WC | PK | WC | PK | WC | PK | WC | PK | |

| ECA | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Lotus A | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| UEA I | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + |

| WGA | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| PBSc | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

WC, H. pylori whole-cell samples.

PK, Bacterial cells treated with PBS (pH 4; 20°C, 30 min) and proteinase K (0.1 mg/ml; 60°C, 1 h).

Bacterial samples (40 μl) were mixed with PBS (10 μl) as negative controls.

Analysis of strains before and after pretreatment demonstrated a decrease in protein concentration (up to 67%) in the extracts, which then could be successfully lectin typed. Furthermore, samples of three strains were taken at three stages of the proteolytic pretreatment and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and silver staining. Whole-cell samples had many contaminating high- and low-molecular-weight protein bands, samples taken after treatment with PBS (pH 4) had in two cases notably fewer bands, and samples after the full pretreatment had profiles consistent with those of H. pylori high-molecular-weight LPS (10, 12). Taken together, the data point to removal of nonspecific protein interactions following pretreatment of strains, which eliminates autoagglutination and allows successful lectin typing.

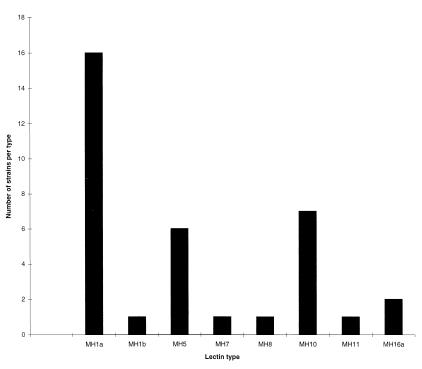

Lectin reaction patterns and typing scheme.

Of the initial eight lectins used, five were found to be the most useful for strain differentiation of H. pylori, namely, AAA, ECA, Lotus A, UEA I, and WGA. These lectins reacted with the extracts at relatively high frequencies and produced clear and consistent results between different batches of lectins used. Of the remaining three lectins, LCA and SBA bound to strains at frequencies too low (3 and 22%, respectively) to further aid strain differentiation whereas STA did not yield reproducible agglutination results. A possible 16 lectin types could be obtained upon testing with the four lectins ECA, Lotus A, UEA I, and WGA. Based on these 16 lectin patterns, we propose a strain typing scheme which is summarized in Table 2. Due to the high frequencies of reaction of AAA lectin with bacterial strains, we propose to use this lectin to subtype MH1 and MH16 types, which have, respectively, all positive and all negative reactions with the four lectins ECA, Lotus A, UEA I, and WGA. In tests with these five lectins, eight reaction patterns were observed with the 35 pretreated Irish strains, whose frequencies of distribution among the lectin types are shown in Fig. 2. The patterns were independent of culture on solid or in liquid media, independent of the batch of lectin, and stable following random selection of stocks that were grown and retyped over the course of 8 weeks.

TABLE 2.

Proposed typing scheme for H. pylori with a panel of five lectins

| Type | Result of test with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECA | Lotus A | UEA I | WGA | AAA | |

| MH1 | + | + | + | + | |

| MH1a | + | ||||

| MH1b | − | ||||

| MH2 | + | + | + | − | |

| MH3 | + | + | − | − | |

| MH4 | + | − | − | − | |

| MH5 | − | + | + | + | |

| MH6 | − | − | + | + | |

| MH7 | − | − | − | + | |

| MH8 | + | − | − | + | |

| MH9 | + | − | + | + | |

| MH10 | + | + | − | + | |

| MH11 | − | + | − | − | |

| MH12 | − | − | + | − | |

| MH13 | − | + | − | + | |

| MH14 | + | − | + | − | |

| MH15 | − | + | + | − | |

| MH16 | − | − | − | − | |

| MH16a | + | ||||

| MH16b | − | ||||

FIG. 2.

Distribution of lectin types among the 35 H. pylori isolates from the Irish population.

Relationship of O side chain expression to bacterium-lectin interactions.

SDS-PAGE and silver stain analysis confirmed the expression of high-molecular-weight LPSs by all of the 36 H. pylori strains reported previously (10, 12). In particular, H. pylori NCTC 11637 that had been induced to express low-molecular-weight (rough-form) LPS (12) could not be lectin typed after proteolytic pretreatment of cells due to autoagglutination in control wells containing PBS. However, autoagglutination in the control wells was not observed for NCTC 11637 expressing smooth-form LPS (10) and this strain was lectin typeable (MH1a).

To further study this implied interaction of lectins and the O side chain, lectin dot analysis of three pretreated strains was performed with HRP-conjugated Lotus A lectin, which has been shown previously to have an affinity for the fucosylated Lex determinant (23), and the results were compared with those of immunodot analysis of the same pretreated extracts with anti-Lex and Ley MAbs. The lectin dot analysis gave the same reaction pattern with the strains as the lectin agglutination assay using native Lotus A, and the results were consistent with expression of Lex and Ley determinants by the LPSs of the strains as determined by immunodot analysis (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Correlation of results of three assays to detect fucose and fucosylated antigens in H. pylori proteolytically treated extractsa

| H. pylori strain extract | Test result by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agglutination with Lotus A lectin | Dot assay with Lotus A lectin | Immunodot assay with:

|

||

| Anti-Lex antibody | Anti-Ley antibody | |||

| 97-f78 | + | + | + | + |

| 97-f79 | + | + | + | + |

| 97-f82 | − | − | − | − |

H. pylori whole-cell samples were treated with PBS (pH 4; 20°C, 30 min) and proteinase K (0.1 mg/ml; 60°C, 1 h).

DISCUSSION

The widespread nature of H. pylori infection warrants development of a practical and simple assay for strain differentiation in large-scale epidemiological studies. In a preliminary investigation, Ascencio et al. used lectins in a slide agglutination assay to differentiate H. pylori strains (1). A microtiter assay was developed in the present study, since this method ensures a high rate of processing of strains and has been successfully applied to lectin typing of strains of Campylobacter spp. and investigation of lectin interactions with other bacterial species (13, 14, 21, 22). However, in contrast to a report of the superiority of slide agglutination over the use of microtiter plates for lectin typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli (22), no major problems were encountered with microtiter plates to analyze lectin-H. pylori interactions.

Similar to previous investigators (22), we have found that untreated H. pylori cells tend to autoagglutinate or bind nonspecifically to lectins and, therefore, are unsuitable for use in a lectin assay. The system we have developed eliminates cell surface proteins that can contribute to autoagglutination. After a proteolytic treatment, which simply involved washing in buffer and treatment with proteinase K, lectin types remained stable and were independent of lectin source or batch, with the exception of STA, which was subsequently excluded from the typing scheme. Furthermore, with the typing system 35 Irish H. pylori strains were grouped into eight different lectin types. In the future, the addition of more lectins to the panel may increase the scheme’s discriminatory power and hence increase the number of groups observed for the same number of strains. This would be a particularly useful approach to further subdivide the predominant lectin type, MH1a. On the other hand, a very large number of groups would make it more difficult for useful epidemiological relationships to be observed, and thus, any further additions of lectins to the scheme have to be made in the light of these restrictions.

Our scheme to differentiate H. pylori strains has many advantages over existing H. pylori typing assays. In comparison with DNA-based methods (3, 7, 8, 15, 19), far less heterogeneity was observed with our five-lectin-panel typing scheme, and therefore, more useful groupings for epidemiology may be generated. Although many of the DNA-based methods have excellent reproducibility, good discriminatory power, and fair to good ease of interpretation, many of the techniques are demanding to perform, of high cost, and time-consuming. Our lectin typing scheme, like others (13, 14, 22), does not require the raising of antisera in animals, as is required for antibody-based typing systems (9). This is both ethically sound and economically advantageous. Moreover, the system used is simple and has no requirements for specialized equipment and the reagents are commercially available and stable on storage, making the system convenient for use in a nonspecialized clinical laboratory.

A previous study involving Campylobacter spp. demonstrated that a heating pretreatment greatly reduced nonspecific binding of lectins (22). A dominant and heat-stable cell surface carbohydrate-containing molecule of gram-negative bacteria is LPS, which is a virulence factor of H. pylori (10, 11). It has been shown that the O side chain of a majority of H. pylori strains express Lex and Ley blood group determinants containing galactose, N-acetylglucosamine, and fucose (11, 16). Therefore, we chose a panel of lectins to type H. pylori strains which had specificities for these moieties, and in addition, we included other lectins with specificities for sugars, some of which are present in the core of LPS, to increase the extent of discrimination among strains.

The results of SDS-PAGE, dot blot, and lectin dot analyses are consistent with the presence and availability for lectin binding of LPSs in bacterial extracts. The SDS-PAGE profiles of strains and proteolytically treated samples were consistent with the presence of high-molecular-weight LPS (10, 12). The occurrence of Lex and Ley determinants in the treated extracts correlated with a lectin dot assay with Lotus A. Thus, the lectins may interact primarily, but not solely, with the O side chains of H. pylori LPS. The possibility that other glycoconjugates present in H. pylori contribute to lectin reactivity could be argued. However, to date, evidence indicates that LPS is the predominant carbohydrate-containing antigen of H. pylori (10).

Expression of high-molecular-weight LPS was necessary for lectin typing of at least one strain. Although loss of O side chain production can occur upon extensive subculturing of strains on solid media (10, 12), maintenance of stock cultures without excessive subculturing can avoid such loss. Furthermore, as fresh clinical isolates of H. pylori express high-molecular-weight LPS (12) and are utilized in epidemiological studies, the requirement of the system for strains expressing an O side chain on their LPSs is not a limitation in a practical context. Nevertheless, in situations where it may be necessary to compare fresh clinical isolates with culture collection strains, growth of strains in liquid media can stabilize O side chain expression (10).

In summary, the use of a lectin agglutination assay to differentiate H. pylori strains is a simple, cost-effective method requiring small amounts of biomass. The cost is currently approximately 300 U.S. dollars for reagents per 1,000 strains tested. Future expansion of this system is possible. Further work analyzing the lectin reaction patterns of H. pylori clinical isolates from different European countries has been carried out. It has been shown with the lectin typing system described here that 116 strains can be divided into 16 types and that certain types predominate in specific geographic areas (6). Similar to other investigators typing Campylobacter spp. (13, 22), we have found that lectin type does not correlate with serotype, indicating different specific binding targets for lectins and antibodies (6). Our finding that autoagglutination of H. pylori cells can be eliminated upon proteolytic treatment, thereby allowing successful lectin typing of strains, may be useful in the context of future epidemiological and pathobiological studies of this organism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John Ferris and Linda McArdle for their technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from BioResearch Ireland and the Irish Health Research Board (to A.P.M.), the Swedish Medical Research Council (to T.W., 16X04723), and the medical faculty of Lund University, Lund, Sweden (to S.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ascencio F, Guruge J L, Ljungh A, Megraud F, Wei S, Wadström T. Lectin typing of Helicobacter pylori. In: Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit H, editors. Helicobacter pylori, gastritis and peptic ulcer. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1990. pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S, Fraser A, Holliss B, Schmid J, O’Toole P W. Evidence for ethnic tropism of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3708–3712. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3708-3712.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton C L, Kleanthous H, Dent J C, McNulty C A M, Tabaqchali S. Evaluation of fingerprinting methods for identification of Helicobacter pylori strains. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:1040–1047. doi: 10.1007/BF01984926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hitchcock P J, Brown T M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt R H. The role of Helicobacter pylori in pathogenesis: the spectrum of clinical outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(Suppl. 220):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hynes, S. O., and A. P. Moran. Unpublished data.

- 7.Li C, Ha T, Chi D S, Ferguson D A, Jr, Jiang C, Laffan J J, Thomas E. Differentiation of Helicobacter pylori strains directly from gastric biopsy specimens by PCR-based fragment length polymorphism analysis without culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;135:3021–3025. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3021-3025.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall D G, Chua A, Keeling P W N, Sullivan D J, Coleman D C, Smyth C J. Molecular analysis of Helicobacter pylori populations in antral biopsies from individual patients using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprinting. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;10:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mills S D, Kurjanczyk L A, Penner J L. Antigenicity of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1370–1377. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3175-3180.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran A P. Cell surface characteristics of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;10:271–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran A P, Appelmelk B J, Aspinall G O. Molecular mimicry of host structures by lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter and Helicobacter spp.: implications in pathogenesis. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran A P, Helander I M, Kosunen T U. Compositional analysis of Helicobacter pylori rough-form lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1370–1377. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1370-1377.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Sullivan N O, Benjamin J, Skirrow M B. Lectin typing of Campylobacter isolates. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:957–960. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.11.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pistole T G. Interaction of bacteria and fungi with lectins and lectin-like substances. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:85–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salama S M, Jiang Q, Chang N, Sherbaniuk R W, Taylor D E. Characterization of chromosomal DNA profiles from Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from sequential gastric biopsy specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2496–2497. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2496-2497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simoons-Smit I M, Appelmelk B J, Verboom T, Negrini R, Penner J L, Aspinall G O, Moran A P, Fei Fei S, Bi-Shan S, Rudnica W, Savio A, de Graaff J. Typing of Helicobacter pylori with monoclonal antibodies against Lewis antigens in lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2196–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2196-2200.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smibert R M, Krieg N R. General characteristics. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Costilow R N, Nester E W, Wood W A, Kreig N R, Philips G B, editors. Manual of methods for general bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1981. pp. 409–443. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soltesz L V, Mårdh P A. Serum-free liquid medium for Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Curr Microbiol. 1980;4:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tee W, Lambert J, Smallwood R, Schembri M, Ross B C, Dwyer B. Ribotyping of Helicobacter pylori from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1562–1567. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1562-1567.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai C, Frasch C E. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Ann Biochem. 1982;119:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong K H, Skelton S K, Feeley J C. Interaction of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli with lectins and blood group antibodies. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:134–135. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.1.134-135.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong K H, Skelton S K, Feeley J C. Strain characterization and grouping of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli by interaction with lectins. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:407–410. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.3.407-410.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan L, Wilkins P, Alvarez-Manilla G, Do S, Smith D F, Cummings R D. Immobilized Lotus tetragonolobus agglutinin binds oligosaccharides containing the Le x determinant. Glycoconj J. 1997;14:45–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1018508914551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]