Abstract

Objective:

The association between parental mental health difficulties and poor child outcomes is well documented. Few studies have investigated the intergenerational effects of trauma in immigrant populations. This study examined the relationships among parental trauma, parenting difficulty, duration of planned family separation, and child externalizing behavior in an archival dataset of West African voluntary and forced immigrants in New York City. We hypothesized that parenting difficulty would mediate the association between parental posttraumatic stress and child externalizing behavior and that this association would be stronger for parent-child dyads that had undergone lengthier separations during migration.

Method:

Ninety-one parents reported on their posttraumatic stress symptoms using the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) and on the behavioral health of one child between the ages of 5 and 12 years using the externalizing items of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL Externalizing). A 4-item self-report scale assessed difficulty parenting in the last month.

Results:

Linear regression analyses showed that parenting difficulty partially mediated the relationship between HTQ and CBCL scores. The relationship between HTQ and CBCL scores was not significant for parents separated from their children for one year or less but was significant for those never separated or separated for longer than one year. Higher HTQ scores were most strongly associated with higher CBCL Externalizing scores for those separated longer than one year.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that children of immigrants recovering from trauma are at risk of exhibiting behavioral symptoms and highlight a potential intervention target for improving child outcomes in immigrant families.

Keywords: child externalizing behavior, parental trauma, parenting difficulty, separation, immigrant families

International migration from sub-Saharan Africa has increased by a third since 2010, making the region among the fastest-growing sources of immigrants worldwide (Conner, 2018). Recent histories of civil conflict across the continent mean that many of these immigrants have higher rates of trauma exposure than other immigrant populations. In the U.S., one quarter of African immigrants are refugees (Capps, McCabe, & Fix, 2011). After entering the U.S., many African immigrants are at heightened risk for further traumatic exposure because African immigrants have tended to resettle in low-income neighborhoods with high crime rates (Kataoka et al., 2003). Thus, premigration histories and settlement patterns may put African immigrants at risk for posttraumatic stress and other stress-related problems. At the same time, psychological problems often go untreated in African immigrant communities due to concerns about stigma, which may further increase the risk of worsening symptoms (Fenta, Hyman, & Noh, 2006; Nadeem et al., 2007). Separation from old support systems may compound such vulnerability. How such vulnerability affects the second generation of African immigrants has not been examined and is the subject of this study.

The finding in the general population that parents’ psychological distress may have adverse impacts on their children’s mental health (Stein & Harold, 2015) holds for trauma-affected populations as well. A meta-analysis found that children of Holocaust survivors in clinical treatment settings had poorer mental health than comparable Jewish children whose parents had not been through the Holocaust (van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2003). A systematic review examining the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) on children’s outcomes in military families demonstrated that parents’ PTSD symptoms are associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in their children. The domains of parent-child communication and parental engagement were particularly challenging (Creech, 2017). Other research suggests that intergenerational effects of trauma may be mediated via the emotional numbing associated with PTSD, which negatively affects the quality of parent-child relationships (Ruscio, Weathers, King, & King, 2002).

Although there is little research on the impact of parents’ trauma-related symptoms on children’s wellbeing in the general immigrant literature, refugee parents’ symptoms have received some attention. Although effect sizes of the impact of immigrant parents’ mental health on their children’s wellbeing vary from study to study (Ajdukovic & Ajdukovic, 1993; Rousseau, Drapeau, & Corin, 1998), there is evidence supporting the contention that parents’ trauma symptoms among immigrants are associated with worse child health (Vaage, 2011; Panter-Brick, 2014). Southeast Asian refugee mothers’ traumatic distress was indirectly associated with their adolescents’ depressive symptoms and antisocial behavior (Sangalang, Jager, & Harachi, 2017). Children of torture victims with PTSD may be susceptible to higher levels of internalizing and externalizing symptoms than children of parents who did not experience torture (Daud, 2005). A meta-analysis of 42 refugee studies found that parental posttraumatic stress symptoms significantly affected child mental health status in some way (Lambert, Holzer, and Hasbun, 2014). There is even some evidence that some types of parental traumatic exposure are more strongly correlated with refugee children’s psychological problems than are even the children’s own exposures (Fazel, Reed, Panter-Brick, Stein, 2012).

Mediating Role of Parenting Difficulty

Few studies have examined factors that may explain the connection between immigrant parents’ mental health and their children’s psychological wellbeing. Parental trauma may result in poor child mental health via weak family functioning. Higher levels of family cohesion and parental support have been linked to greater mental wellbeing in refugee children (Kovacev, 2004; Rousseau, 2004). A number of studies implicate parenting style in explaining the transmission of psychological problems from parent to child. There is some evidence that parental posttraumatic stress leads to harsh, overprotective, and role-reversing parenting styles, which in turn causes higher levels of child conduct problems, hyperactivity, emotional problems, and interpersonal problems (Field, 2013; Bryant, 2018). Among Bosnian refugees living in Chicago, Weine and colleagues (Weine, Feetham, Kulauzovic, Knafl, Besic et al., 2006) found that many parents with severe trauma histories were more hypervigilant against the influence of American culture on their children and attempted to impose strict controls on their children’s time and movement, resulting in increased conflict with them. Cambodian refugee parents with mental health problems were at greater risk for anger towards their children as well (Hinton, Rasmussen, Nou, Pollack, & Good, 2009). A history of persecution may also result in a reluctance to examine the impact of parents’ own parenting practices in facilitating child behavior problems (Walter & Bala, 2007).

Planned Parent-child Separation

Although rarely examined in studies of immigrants’ mental health, planned parent-child separation may also impact children’s psychological wellbeing. In the Longitudinal Student Adaptation Study (LISA), 85% of the 385 adolescent children of Chinese, Central American, Dominican, Haitian, and Mexican origin revealed that they had been separated from at least one parent for extended periods of time in the migration process. Children who had experienced separation from their parents during the migratory process were more likely to report depressive symptoms than those who had not, though contexts of immigration and length of separation moderated the effects of separation on these outcomes (Suarez-Orozco, Todorova, & Louie, 2002). A study of refugee boys in Quebec found that those living with both biological parents had rates of psychological symptoms five times lower than those living with only one or neither parent (Tousignant et al., 1999). Parent-child separations during migration may be distressing because they involve, first, interrupted attachments with parents and, later, with interim guardians to whom the children were temporarily entrusted (Bernhard et al., 2006; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2002). However, the literature on the impact of planned separation on child outcomes is somewhat equivocal. A dissertation study examining stress responses in Jamaican immigrant families found no differences in levels of stress responses between children who had been separated from their mothers and those never separated (Hohn, 1996). Among Cambodian refugee families, Sack et al. (1995) found no association between rates of separation and intergenerational PTSD transmission, although the association between parental PTSD and children’s PTSD was significant. Paradoxically, Rasmussen, Cissé, Han, and Roubeni (2018) found that histories of parent-child separation were associated with greater perceptions of neighborhood safety among West Africans parents living in New York City, even after controlling for area crime rates. Exactly how histories of planned parent-child separation affect children’s subsequent behavior among immigrant populations has yet to be examined.

Child Age

A number of studies have examined externalizing behavior trajectories in children. These studies have reported that children exhibit varying levels of externalizing behavior in early childhood, generally exhibit reductions in externalizing behaviors as they transition to adolescence, and experience this decline at varying rates (Miner & Clarke-Stewart, 2008). In a study involving a representative sample of 2,000 Dutch girls and boys between the ages of 4 and 18, mothers reported declines in externalizing behaviors. Similar trends were documented in U.S.-based low-income boys ranging from ages 2 to 6 (Owens & Shaw, 2003) and community-based children ranging from ages 5 to 17 (Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005).

Additionally, children’s developmental stage may be a factor that influences the transmission of trauma from parent to child. A meta-analysis examining the relationship between parental psychopathology and child behavior problems found that maternal psychopathology has a greater effect on psychopathology in younger children, while paternal psychopathology has a greater effect in older children (Connell & Goodman, 2002). Studies examining the impact of the timing of children’s exposure to parental trauma symptoms are limited, and more research is needed to clarify whether younger age is associated with more deleterious impact.

The Current Study

The current study draws on data from a community-based needs survey surrounding childcare undertaken with a community-based organization (CBO) serving Fulani immigrants living in New York City. The Fulani are a predominantly Muslim people of approximately 20–25 million living across West Africa (Crowe, 2010; Danver, 2015). As market-dominant minorities in many West African countries, Fulani have been integral to economic growth throughout the region and have been present in large numbers among entrepreneurial immigrants to the U.S. As large minorities, they have also been targeted in recent conflicts in the region, and many have immigrated as refugees and asylum seekers. Fulani are present in large numbers in New York, NY, Philadelphia, PA, Atlanta, GA, and Columbus, OH.

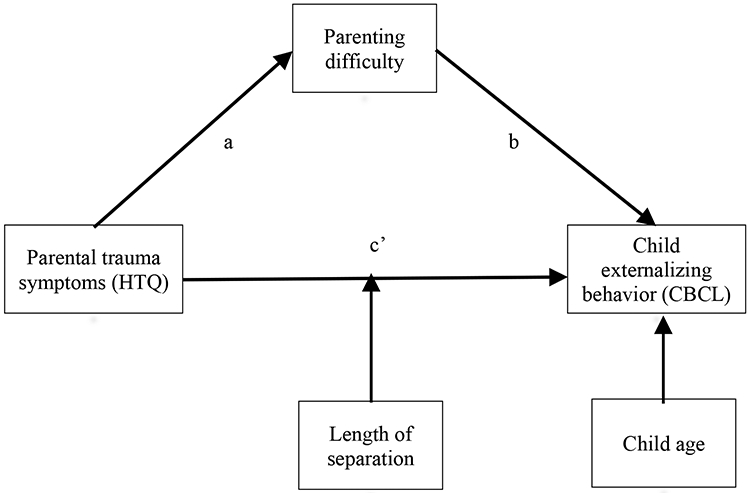

Aims of the current study were to test a model in which (1) parental posttraumatic stress symptoms predicted child behavior through the mediating effect of parenting difficulty and (2) planned separation between parents and children moderated intergenerational transmission of psychological symptoms from parents to children (see Figure 1). We hypothesized that parenting difficulty would significantly mediate the relationship between parental trauma symptoms and children’s externalizing behavior, and that a history of separation would moderate this association by strengthening it.

Figure 1.

A conceptual diagram of the proposed regression model with parenting difficulty mediating the relationship between parent’s PTSD symptoms and children’s externalizing behavior and the length of parent-child separation moderating the relationship. Child age is a covariate.

Methods

Participants

Participants were parents of West African origin who had lived in the U.S. for at least three years and had at least one child between the ages of 5 and 12 years. Fulani-speaking community-based interviewers identified 107 individuals who met recruitment criteria. No exclusion criteria were employed. The large majority were Fulani (n = 87, 95.6%) and Muslim (n = 89, 97.8%). Additional demographics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 91)

| Characteristic | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 39.3 | 8.7 |

| Years lived in U.S. | 12.0 | 56.8 |

| Number of children | 3.3 | 1.5 |

| Number of children living in New York City | 3.2 | 1.5 |

| n | % | |

| Parent Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 33.0 |

| Female | 61 | 67.0 |

| Gender of referent child | ||

| Male | 52 | 57.1 |

| Female | 39 | 42.9 |

| Borough | ||

| Bronx | 55 | 60.4 |

| Manhattan | 17 | 18.7 |

| Brooklyn | 12 | 13.2 |

| Queens | 7 | 7.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 72 | 79.1 |

| Divorced | 8 | 8.8 |

| Separated | 3 | 3.3 |

| Never married | 8 | 8.8 |

| Currently employed | ||

| Blue collar job | 55 | 60.4 |

| White collar job | 27 | 29.7 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 9.9 |

| Birth country | ||

| Guinea | 66 | 72.5 |

| Sierra Leone | 13 | 14.3 |

| Senegal | 3 | 3.3 |

| Other | 9 | 9.9 |

| Immigration status | ||

| U.S. citizen | 21 | 23.1 |

| Permanent resident | 45 | 49.5 |

| Asylee or refugee | 7 | 7.7 |

| Asylum applicant | 6 | 6.6 |

| Other or no status endorsed | 12 | 13.2 |

| Reason for migration | ||

| Voluntary | 65 | 71.4 |

| Forced | 21 | 23.1 |

| Missing | 5 | 5.5 |

| Has at least one non-referent child in age range | ||

| Less than 5 | 60 | 65.9 |

| 5-12 | 46 | 50.5 |

| 13-17 | 44 | 48.4 |

| 18 and older | 24 | 26.4 |

Participants reported having an average of 3.33 children (SD = 1.54), with an average of 3.17 (SD = 1.5) living with them in New York. By design all had at least one child between the ages of 5 and 12. The mean number of these children per participant was 1.64 (SD = 0.78). Two-thirds (n = 60, 65.9%) also had children younger than 5 (M = 0.89, SD = 0.81), half (n = 44, 48.4%) aged 13–17 (M = 0.56, SD = 0.72), and a quarter (n = 24, 26.4%) older than 18 (M = 0.37, SD = 0.69).

In order to generate data specific to primary school-aged children, interviewers asked parents to select referent children between 5 and 12 years of age. For those with only one child in this age range, that child was selected; for those with more than one child in this age range, interviewers instructed parents to select the child with the birthday nearest to the interview date (there were no twins). Referent children consisted of 52 boys (57.1%) and 39 girls (42.9%), with a mean age of 8.18 years (SD = 2.04). Four-fifths (n = 74, 81.3%) were born in the U.S., one-tenth in Guinea (n = 10, 11%), and a small percentage in other African (n = 4, 4.4%) and Western countries (n = 3, 3.3%).

Procedures

The executive committee of the CBO emphasized that community members were unlikely to disclose personal information if interviewed by non-Fulani individuals with whom they had no personal connection. Many would be hesitant to participate for reasons such as limited English proficiency and vulnerable status as immigrants. In consultation with the PI, CBO leaders decided to implement a limited snowball sampling approach for recruitment that relied on Fulani-speaking community-based interviewers. Interviewers were recruited through monthly CBO meetings and Fulani radio advertisements. To reduce the likelihood of biases typically associated with snowball sampling, interviewers were asked to recruit a limited number of participants (five to 15 each). They were asked to recruit participants from their neighborhoods, places of worship, and other personal social networks. Interviews were conducted either in space provided by the CBO or in participants’ homes, and responses recorded on electronic tablets (but not audiorecorded). To maintain fidelity, the PI met regularly with interviewers to review the protocol, discuss participants’ reactions, and inquire about adverse events. (For more information on interviewer recruitment, qualifications and training, see Rasmussen et al., 2018).

None of the interviewers could read Fulani because the education systems of Guinea and Sierra Leone have not included formal instruction in the language since 1985. Translation of measures therefore involved (a) translating and teaching response scales to interviewers in Fulani, (b) collaborating with leaders of the CBO to translate other items, and (c) meeting with interviewers during data collection to address issues of translation and wording. Because members of Fulani communities in the U.S. occasionally mix Fulani and English, interviewers responded to an item after each interview measuring the balance of English and Fulani used. The mean of this 7-point Likert-type scale was 4.93 (SD = 1.78), with three (3.3%) recorded as “All English,” six (6.6%) “Almost all English,” 10 (11%) “Mostly English, but some Fulani,” 20 (22%) “Half Fulani, half English,” 12 (13.2%) “Mostly Fulani, but some English,” 12 (13.2%) “Almost all Fulani,” and 26 (28.6%) “All Fulani”. Such data was missing for two interviews.

Two protections were implemented to ensure the safety of participants. First was a waiver signed consent, effectively allowing for anonymous participation. Although interviewers were privy to who participated in the study, identifying personal information (e.g., name, address, phone number) was never collected or stored. Second, interviewers did not directly inquire about undocumented status. Rather, it was inferred from negative responses to questions about various types of legal documented status. For example, participants were asked whether they were U.S. citizens. If they answered “no”, they were asked whether they were green card holders, and so on. Participants providing a negative response to all status questions were designated as undocumented.

The CBO overseeing the study played an influential role in the execution of this study. The organization set the agenda based on community concerns, hence the focus on healthcare for children and childcare for parents in the parent study. The CBO helped the research team identify and interview prospective interviewers, provided space for training and interviewing, and was provided a report of findings at the end of the study. Study procedures were approved by the CBO and the Institutional Review Board of Fordham University, which granted the researchers the waiver of signed consent.

Measures

Potentially Traumatic Events

Potentially traumatic events (PTEs) were measured using an adapted version of the 17-item Life Events Checklist (LEC). The original LEC has been found to be a comprehensive list of PTE types with good test–retest reliability and convergent validity with other PTE checklists (Gray, Litz, Hsu, & Lombardo, 2004). Drawing from a decade of experience working with this community, the research team adapted the original checklist using a rational restructuring approach. This entailed condensing items that were similar, identifying event types that were known to be represented in the community, and selecting event types that were likely to be honestly reported. The adapted LEC contained 12 items covering events such as natural disasters, transportation accidents, assault, forced sex, and exposure to combat. The total number of types of both personally experienced and witnessed PTEs was used to represent trauma exposure.

Parents’ Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

PTSD symptoms were measured with the 16-item PTSD section of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ; Mollica et al., 1992). The HTQ measures the four PTSD symptom clusters – re-experiencing (e.g., “Feeling as though the event is happening again”), avoidance (e.g., “Avoiding activities that remind you of the traumatic or hurtful event”), numbing (e.g., “Unable to feel emotions), and hyperarousal (e.g., “Feeling easily startled”) – and asks participants to respond to a 4-point scale measuring the severity of symptoms in the past week. The HTQ has been used in several West African populations, where it has attained good internal reliability estimates (Rasmussen, Smith, & Keller, 2007; Rasmussen et al., 2010). Cronbach’s alpha was .79 in the current sample.

Children’s Externalizing Behavior

Parents rated their children’s externalizing behavior using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) Externalizing behavior subscale. The CBCL is the most widely used parent report measure of child behavior and has shown good test–retest reliability across multiple populations. The Externalizing scale is comprised of 32 items representing forms of bothersome behavior at several levels of severity (e.g., “showing off or clowning,” “physically attacks people,” “sets fires”); parents respond with “not true,” “somewhat or sometimes true,” or “very true or often true.” Cronbach’s alpha for the CBCL Externalizing scale in the current sample was .90. Although the CBCL also includes an internalizing scale, they were not included in the study protocol. This decision was made because all of the problems identified by CBO leaders were externalizing. Additionally, it was the PI’s experience that, when discussing children’s behavior, parents in this community appeared to be almost exclusively attuned to externalizing problems.

Parenting Difficulty

Four items from the National Survey of Child Health (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, 2007) measured participants’ difficulty parenting in the last month in the following domains: difficulty caring for the child, behavior that bothered parents, feeling angry with the child, and the child behaving badly. Parents responded on a five- point frequency scale, from never to always. Cronbach’s alpha for these items in the current sample was .81.

Parent-child Separation

A third of parents (n = 32, 34.4%) reported that they had been voluntarily separated from referent children at some point during their children’s lives. Length of this planned separation was measured categorically using seven levels and ranged from less than 3 months (n = 7, 7.5%) to more than 5 years (n = 5, 5.4%). Histories of separation from children were later transformed into a three-level variable: never separated, separated 1 year or less, and separated for more than a year.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The average number of PTEs was 4.16 (SD = 4.22) and average score on the HTQ was 1.22 (SD = 0.28). Parents reported difficulty parenting referent children “rarely” in the past month (M = 1.98, SD = 0.81). The mean CBCL Externalizing score for referent children was 6.95 (SD = 7.08). Two-thirds of parents had never been separated from referent children (n = 61, 65.5%), one-tenth separated 1 year or less (n = 10, 11.1%), and a quarter separated for more than a year (n = 22, 23.3%).

Correlation analyses were first conducted to identify putative factors associated with children’s externalizing behavior (see Table 2). Parents’ HTQ scores, parenting difficulty, length of parent-child separation, and child age were significantly correlated with CBCL Externalizing scores. Child age was significantly correlated with CBCL Externalizing scores, but the association was not in the theorized direction (i.e., younger age associated with more externalizing symptoms). As a result, child age was included in the model as a covariate rather than as a moderator. An independent samples t-test and a one-way ANOVA were conducted to examine whether CBCL Externalizing scores differed by the gender and immigration status of the referent child. CBCL scores were not significantly different across gender (t89= −0.15, p >.05) or immigration status (F5,85= 0.37, p >.05).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CBCL - Exta | - | |||||||

| 2. HTQb | 0.45** | - | ||||||

| 3. Parenting difficulty | 0.56** | 0.38** | - | |||||

| 4. Length of separation | 0.35** | 0.13 | 0.15 | - | ||||

| 5. Child's age | 0.22* | 0.13 | −0.03 | 0.20 | - | |||

| 6. Forced migration | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.15 | 0.06 | - | ||

| 7. Paren's gender | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.09 | −0.32** | −0.10 | −0.36** | - | |

| 8. PTEsc | 0.02 | 0.22* | −0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.34** | −0.12 | - |

| M | 6.85 | 1.22 | 1.98 | 0.52 | 8.18 | 0.24 | 1.67 | 4.17 |

| SD | 7.08 | 0.28 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 2.04 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 4.22 |

Externalizing scale of the Child Behavior Checklist.

HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.

PTEs = Sum of potentially traumatic events (PTEs).

p < .05

p < .001.

Conditional Process Modeling

To assess the mediation hypothesis concerning the indirect effect of parents’ HTQ scores on CBCL Externalizing raw scores through parenting difficulty, we first established that that there were significant relationships between HTQ scores and CBCL Externalizing (i.e., the predictor and outcome ), HTQ scores and parenting difficulty (i.e., predictor and mediator), and parenting difficulty and CBCL Externalizing (i.e., mediator and outcome; c.f., Baron & Kenny, 1986). These associations were assessed using bivariate correlational analysis, the results of which are displayed in Table 2.

Regression analysis was used to investigate the hypothesis that parenting difficulty mediates the effect of parents’ HTQ symptoms on CBCL Externalizing raw scores. Results indicated that HTQ scores were a significant predictor of parenting difficulty, B = 1.13, SE = .29, p < .05 in a model that explained 15% of the variance in CBCL Externalizing (R2 = 0.15, F(2,88)=7.76, p<.001). Parenting difficulty was a significant predictor of CBCL Externalizing scores, B = 3.73, SE = .74, p < .05 (see Table 3). These results supported the mediational hypothesis. HTQ symptoms remained a significant predictor of CBCL Externalizing raw scores after controlling for the mediator, parenting difficulty, B = 5.41, SE = 2.65, consistent with partial mediation. The indirect effect was tested using a percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 5,000 samples (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), implemented with the PROCESS macro Version 3.3 (Hayes, 2019). The indirect coefficient was also significant, B = 4.23, SE = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.88, 7.56, p < .05.

Table 3.

Linear regression model for child externalizing behavior

| B | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | −5.27 | 2.90 |

| HTQa | 5.41* | 2.65 |

| Parenting difficulty | 3.73*** | 0.74 |

| Separated 0-1 yr | 2.56 | 1.64 |

| Separated >1yr | 4.08** | 1.52 |

| HTQ x Separated 0-1 yr | −4.57 | 4.96 |

| HTQ x Separated >1yr | 13.30** | 6.21 |

| Child age | 0.46 | 0.29 |

R2 = 0.50***.

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

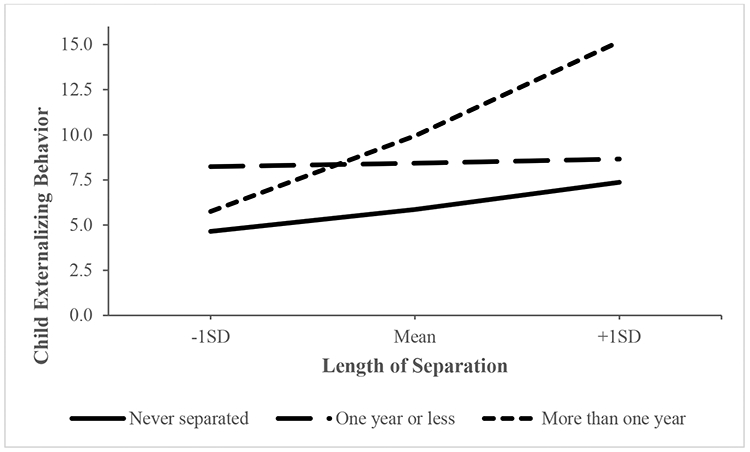

Moderation Analysis

HTQ scores were mean-centered prior to moderation analysis. History of planned separation between parent and child moderated the relationship between the HTQ scores and the CBCL Externalizing behavior scores (path c’) with the interaction term accounting for a significant but small increase in variance, ΔR2 = 0.04, F(2, 83) = 3.22, p < .05). Analysis of the moderation effect indicated that the relationship between HTQ scores and CBCL Externalizing behavior scores were not significant for parents separated from their children for one year or less, B = .84, SE = 4.30, 95% CI [−7.70, 9.37]. The relationship was significant for those never separated from their children, B = 5.41, SE = 2.65, 95% CI [.15, 10.67], or separated more than one year, B = 18.71, SE = 5.82, 95% CI [1.88, 7.56]. Higher HTQ scores were more strongly associated with higher CBCL Externalizing raw scores for those separated for more than a year than they were for those never separated and those separated one year or less (see Figure 2). Approximately 50% of the variance in CBCL Externalizing scores was accounted for by the predictors (R2 = 0.50).

Figure 2.

Conditional direct effects of HTQ scores on CBCL Externalizing behavior among parents never separated, separated for one year or less, and separated for more than one year from their children.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first quantitative research examining how trauma-related symptoms among West African immigrants in the U.S. may impact their children’s behavior. The aims of the study were (1) to assess whether parenting difficulty mediates the relationship between parental traumatic stress symptoms and child behavior problems in immigrant families and (2) to evaluate whether a history of planned parent-child separation moderates this relationship.

The levels of trauma exposure and trauma symptom severity observed in this sample were within range of those reported in a number of studies examining immigrant samples (Silove, Steel, McGorry, & Mohan, 1998; Kaltman, Green, Mete, Shara, & Miranda, 2010; Wagner, Burke, Kuoch, Scully, Armeli, Rajan, 2013; Akinsulure-Smith, 2014). Of note, the majority of participants in the present study were voluntary migrants, and general immigrant populations tend to report less trauma exposure and symptom severity than asylum seekers and refugees (Silove, Steel, McGorry, & Mohan, 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2012). Moreover, parent-reported CBCL Externalizing scores in this study may be relatively low. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that rates of externalizing disorders may be higher in U.S.-born youth than among immigrant youth (Glover et al., 1999; Hussey et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2003).

Our findings seem to support a model in which parents’ traumatic stress predicts children’s externalizing behavior through parenting difficulty and having a history of separation predicts greater impact of parents’ trauma symptoms on children’s externalizing behavior. Although previous research has suggested that forced versus voluntary migrant status may be associated with child behavioral health (Lustig et al., 2004) and parents’ gender may be associated with trauma transmission (Almqvist & Broberg, 1999; Connell & Goodman, 2002), neither was significantly correlated with child behavior in the present study.

Our finding that planned separation for more than one year magnified the association between PTSD symptoms of parent and child contributes to the somewhat equivocal findings on planned and voluntary parent-child separation in the literature. As reviewed above, studies that address the issue are few. Even fewer studies address the length of separation. Suarez-Orozco and colleagues (Suarez-Orozco, Bang, & Kim, 2011) reported that the psychological consequences of separation were magnified among immigrant students separated from their mother or father for longer periods of time, but that this effect had abated at a five-year followup. In contrast, a previous study by the same research group did not find a relationship between length of separation and psychological symptoms related to anxiety, cognitive functioning, interpersonal functioning, and hostility, though separation was associated with a greater level of reported depressive symptoms (Suarez-Orozco, Todorova, & Louis, 2002). Using the current study’s data, our research group found that greater length of separation was associated with reduced concern for children’s safety (Rasmussen et al., 2018), an ostensibly positive outcome. Among many West African immigrants to the U.S., planned separation is a common strategy perceived to be beneficial in balancing the requirements of parenting and financially successful immigration (Coe, 2008; 2012). However equivocal this limited literature might be, the common use of planned separation among many immigrant families and its association with child-related outcomes suggests that it should be included as a variable of interest in research with immigrant families.

Although we believe the model in which the effect of trauma symptoms on externalizing behavior is mediated by parenting difficulty is justified given the literature, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to rule out the reverse. In other words, it may be that parents’ reports of symptoms on the HTQ that are associated with child externalizing behavior are not the direct result of trauma. The symptoms on the HTQ overlap considerably with symptoms of general anxiety and depression. In light of this, it may be that child externalizing behavior causes parental anxiety and depression, and that this effect is mediated through parenting difficulty. Another possibility is that shared exposure to stressful experiences postmigration accounts for the associations between parents’ HTQ scores, parenting difficulty and children’s externalizing behavior. Consistent with the latter hypothesis, a study of Bosnian refugees in Sweden found that shared stressors accounted for the correlation between parental need for psychiatric treatment and children’s psychological problems (Angel, Hjern, & Ingleby, 2001).

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our findings suggest that children of West African immigrants with trauma-related symptoms may experience negative psychological consequences of trauma themselves. This study supports previous research describing parenting and family relationships (e.g., parental engagement, family communication problems) as pathways through which parental trauma is transmitted to offspring (Spencer & Le, 2006; Giladi & Bell, 2012). Providing treatment to this population is critical for the wellbeing of both parent and child. Indeed, parental trauma symptoms are all the more difficult to endure in tandem with other post-migration stressors and may interfere with the parents’ capacity to respond to the symptoms of their children. Clinicians who work with immigrant children presenting with externalizing symptoms should consider whether parents’ mental health is a factor in generating these symptoms. If this is the case, it may be beneficial to engage these parents in conversations about their own symptoms as well as their and difficulties associated with parenting in addition to equipping them with practical skills to regulate their symptoms during challenging interactions with their children.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of the current study include its cross-sectional design, the sampling strategy, and the use of both Fulani and English in data collection. We tested a regression model justified by the literature, but the cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal conclusions. Future studies employing longitudinal designs would provide empirical direction to theories addressing the relationships between psychological symptoms of parents and children. We attempted to limit the biases inherent in snowball sampling by limiting the number of participants recruited by each interviewer. Standardizing spoken Fulani for a group of non-literate Fulani speakers was a considerable challenge, but we feel confident that through the training we did and regular meetings we collected reliable data.

The number of families with separation in their history may also be a limitation of the study. However, that we found statistical significance indicates that findings related to separation are worth examining in future studies with greater statistical power. Moreover, because voluntary separation is not a feature of many empirical studies, the findings are novel enough to warrant inclusion.

We used a parenting difficulty measure that had yet to be examined in either the immigrant health or intergenerational trauma transmission literatures. Studies that informed our hypotheses evaluated similar constructs, such as family functioning (Sangalang, Jager, & Harachi, 2017) and parenting style (Field, 2013; Bryant, 2018). Future research should examine parenting difficulty alongside related constructs to see which factors are most influential in mediating the relationship between parental posttraumatic stress and child behavioral health. Additionally, the current study did not examine parenting practices or sources of conflict. Moreover, although we feel justified in not including the internalizing scale of the CBCL in the parent study protocol, it is clearly a limitation for this research because there may be internalizing symptoms that are subject to the same intergenerational transmission process as externalizing symptoms. Research clarifying which aspects of parenting and children’s behavior pose the greatest challenge to immigrants will inform interventions to provide trauma-affected immigrants with skills that are effective and culturally appropriate. The current study focused on Fulani immigrant parents and their children. Additional research is needed to determine whether these findings are generalizable to immigrant populations representing other regions and ethnic identities.

Conclusions

In this study within a West African immigrant population in New York City, parents’ PTSD symptoms predicted children’s externalizing behavior. This relationship was strongest among parents who had been separated from their children for more than one year as compared to those who were never separated or separated for up to one year. These findings suggest that providing mental health services to immigrant parents would benefit both parent and child. Moreover, children of forced and voluntary migrants recovering from the deleterious effects of trauma are at risk of experiencing psychological ramifications of trauma exposure themselves. This vulnerability seems to be greatest among children who have experienced lengthy separations from at least one parent. Identifying such children may empower social service professionals and healthcare providers to strategically offer parenting support and other preventive resources to families that are at highest risk of intergenerational trauma transmission.

Clinical Impact Statement.

This study found that parental PTSD is associated with externalizing behavior in West African immigrant children, a relationship that is strongest in parent-child dyads that experienced more than one year of separation. Parent-focused mental health interventions may benefit both parent and child. Recognizing lengthy parent-child separation as a risk factor may inform development of supportive policies and programs as well as enable social service and healthcare professionals to identify and strategically offer parenting support to families that are at greatest risk of parent-child trauma transmission.

Footnotes

This work is based on a parent study that was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fordham University and the Executive Committee of Union Fouta.

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Ajduković M, & Ajduković D (1993). Psychological well-being of refugee children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 17(6), 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinsulure-Smith AM (2014). Exploring female genital cutting among West African immigrants. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 16(3), 559–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almqvist K, & Broberg AG (1999). Mental health and social adjustment in young refugee children y 3½ years after their arrival in Sweden. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(6), 723–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel B, Hjern A, & Ingleby D (2001). Effects of war and organized violence on children: a study of Bosnian refugees in Sweden. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(1), 4–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean T, Derluyn I, Eurelings-Bontekoe E, Broekaert E, & Spinhoven P (2007). Comparing psychological distress, traumatic stress reactions, and experiences of unaccompanied refugee minors with experiences of adolescents accompanied by parents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(4), 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard JK, Landolt P, & Goldring L (2006). Transnational, multi-local motherhood: Experiences of separation and reunification among Latin American families in Canada. CERIS, Policy Matters, 24. Retrieved July 15, 2009, from http://ceris.metropolis.net/PolicyMatter/2006/PolicyMatters24.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Edwards B, Creamer M, O'Donnell M, Forbes D, Felmingham KL, … & Van Hooff M (2018). The effect of post-traumatic stress disorder on refugees' parenting and their children's mental health: a cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 3(5), e249–e258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capps R, McCabe K, Fix M (2011). New streams: Black African migration to the United States. Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Coe C (2008). The structuring of feeling in Ghanaian transnational families. City & Society, 20(2), 222e250. [Google Scholar]

- Coe Cati (2012). Transnational Parenting: Child Fostering in Ghanaian Immigrant Families. In Capps R & Fix M (Eds.), Young children of Black immigrants in America: Changing flows, changing faces (Chapter 8). Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, & Goodman SH (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children's internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner P (2018). International migration from sub-Saharan Africa has grown dramatically since 2010. Fact Tank: Pew Research Center. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/28/international-migration-from-sub-saharan-africa-has-grown-dramatically-since-2010/. [Google Scholar]

- Creech SK, & Misca G (2017). Parenting with PTSD: A review of research on the influence of PTSD on parent-child functioning in military and veteran families. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daud A, Skoglund E, & Rydelius PA (2005). Children in families of torture victims: Transgenerational transmission of parents’ traumatic experiences to their children. International Journal of Social Welfare, 14(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Derluyn I, Mels C, & Broekaert E (2009). Mental health problems in separated refugee adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(3), 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, & Stein A (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenta H, Hyman I, & Noh S (2006). Mental health service utilization by Ethiopian immigrants and refugees in Toronto. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(12), 925–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field NP, Muong S, & Sochanvimean V (2013). Parental styles in the intergenerational transmission of trauma stemming from the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(4), 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks BA (2011). Moving targets: A developmental framework for understanding children's changes following disasters. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(2), 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Giladi L, Bell TS. Protective factors for intergenerational transmission of trauma among second and third generation Holocaust survivors. Psychol Trauma. 2012; 5(4):384–91. [Google Scholar]

- Glover SH, Pumariega AJ, Holzer CE, Wise BK, & Rodriguez M (1999). Anxiety symptomatology in Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 8(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Rasmussen A, Nou L, Pollack MH, & Good MJ (2009). Anger, PTSD, and the nuclear family: A study of Cambodian refugees. Social Science & Medicine, 69(9), 1387–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes M, Jagdev D, Chandra N, & Cunniff A (2008). Risk and resilience for psychological distress amongst unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(7), 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohn GE (1996). The effects of family functioning on the psychological and social adjustment of Jamaican immigrant children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Iritani BJ, Halpern CT, & Bauer DJ (2007). Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: Association with immigrant status. Journal of Immigrant Health, 9, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Green BL, Mete M, Shara N, & Miranda J (2010). Trauma, depression, and comorbid PTSD/depression in a community sample of Latina immigrants. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(1), 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Wong M, Escudero P, Tu W, Zaragoza C, & Fink A (2003). A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacev L, & Shute R (2004). Acculturation and social support in relation to psychosocial adjustment of adolescent refugees resettled in Australia. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(3), 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Holzer J, & Hasbun A (2014). Association between parents’ PTSD severity and children's psychological distress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(1), 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, & Pears KC (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(5), 505–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig SL, Kia-Keating M, Knight WG, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie JD, … & Saxe GN (2004). Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JL, & Clarke-Stewart KA (2008). Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: Relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Edge D, Fongwa M, Belin T, & Miranda J (2007). Does stigma keep poor young immigrant and US-born black and Latina women from seeking mental health care?. Psychiatric Services, 58(12), 1547–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, & Shaw DS (2003). Predicting growth curves of externalizing behavior across the preschool years. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(6), 575–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick C, Grimon MP, & Eggerman M (2014). Caregiver-child mental health: A prospective study in conflict and refugee settings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(4), 313–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2019, January 25). Latin America, Caribbean no longer world’s fastest growing source of international migrants. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/25/latin-america-caribbean-no-longer-worlds-fastest-growing-source-of-international-migrants/ [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Crager M, Baser RE, Chu T, & Gany F (2012). Onset of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression among refugees and voluntary migrants to the United States. Journal of traumatic stress, 25(6), 705–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, Drapeau A, & Corin E (1998). Risk and protective factors in Central American and Southeast Asian refugee children. Journal of Refugee Studies, 11(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau C, Drapeau A, & Platt R (2004). Family environment and emotional and behavioural symptoms in adolescent Cambodian refugees: Influence of time, gender, and acculturation. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 20(2), 151–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangalang CC, Jager J, & Harachi TW (2017). Effects of maternal traumatic distress on family functioning and child mental health: An examination of Southeast Asian refugee families in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 184, 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D, Steel Z, McGorry P, & Mohan P (1998). Trauma exposure, postmigration stressors, and symptoms of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in Tamil asylum-seekers: comparison with refugees and immigrants. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 97(3), 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira ER, & Ebrahim S (1998). Social determinants of psychiatric morbidity and well-being in immigrant elders and whites in east London. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13(11), 801–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JH, Le TN. Parent refugee status, immigration stressors, and Southeast Asian youth violence. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006; 8(4):359–68. [PubMed: 16841183] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Ramchandani P, & Murray L (2008). Impact of parental psychiatric disorder and physical illness. In: Rutter M, Bishop D, Pine D, et al. (Eds.). Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry (5th ed., pp. 407–420). Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, & Harold G (2015). Impact of parental psychiatric disorder and physical illness. Rutter's child and adolescent psychiatry, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Bang HJ, & Kim HY (2011). I felt like my heart was staying behind: Psychological implications of family separations & reunifications for immigrant youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 26(2), 222–257. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Todorova IL, & Louie J (2002). Making up for lost time: The experience of separation and reunification among immigrant families. Family Process, 41(4), 625–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SS, & Fox SH (2001). Traumatic experiences and the mental health of Senegalese refugees. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(8), 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibeault MA, Mendez JL, Nelson-Gray RO, & Stein GL (2017). Impact of trauma exposure and acculturative stress on internalizing symptoms for recently arrived migrant-origin youth: results from a community-based partnership. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(8), 984–998. [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant M, Habimana E, Biron C, Malo C, Sidoli-LeBlanc E, & Bendris N (1999). The Quebec Adolescent Refugee Project: psychopathology and family variables in a sample from 35 nations. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(11), 1426–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaage AB, Thomsen PH, Rousseau C, Wentzel-Larsen T, Ta TV, & Hauff E (2011). Paternal predictors of the mental health of children of Vietnamese refugees. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5(1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & Sagi-Schwartz A (2003). Are children of Holocaust survivors less well-adapted? A meta-analytic investigation of secondary traumatization. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(5), 459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J, Burke G, Kuoch T, Scully M, Armeli S, & Rajan TV (2013). Trauma, healthcare access, and health outcomes among Southeast Asian refugees in Connecticut. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 15(6), 1065–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegersma PA, Stellinga-Boelen AA, & Reijneveld SA (2011). Psychosocial problems in asylum seekers' children: The parent, child, and teacher perspective using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(2), 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolmer L, Laor N, Gershon A, Mayes LC, & Cohen DJ (2000). The mother-child dyad facing trauma: a developmental outlook. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(7), 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Schwalberg RH, Overpeck M, & Kogan MD (2003). Acculturation and the health and well-being of U.S. immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]