Background:

Spirituality is an important, yet often overlooked, component of personal well-being. The purpose of this study was to assess whether spirituality plays an important role in the well-being of US plastic surgeons and residents, and whether spirituality is viewed as an important component of patient care.

Methods:

An anonymous and voluntary email survey was distributed to 3375 members of ASPS during the months of April through June of 2020. The survey distribution included 2230 active members of ASPS and 1149 resident members, all who practice or train within the United States. The survey consisted of 18 multiple-choice questions with answer choices based on a descriptive five-point Likert scale and ranking by priority. Statistical analysis of the results was performed using StataCorp 2019 software.

Results:

A total of 431 completed surveys were received for a response rate of 12.7%. The majority of participants (70%) reported that personal spiritual beliefs and faith contribute positively to emotional well-being. In total, 65% agreed or strongly agreed that their spiritual beliefs provide a healthy framework for handling conflict, suffering, and loss. More than half (51%) reported that as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, their spiritual beliefs and practices have provided increased support and guidance.

Conclusions:

Spirituality is an important component of maintaining wellness for plastic surgeons, and spirituality is recognized by plastic surgeons as an important aspect of the healing process for patients. Efforts should be made to promote spiritual health among the surgical community both during training and in practice.

INTRODUCTION

Spirituality is an important component of personal well-being. Although the concepts of physician wellness and burnout (both attending and resident) have garnered increased attention across medical specialties, little has been written about the role of spirituality in achieving wellness and mitigating burnout within surgery.1,2 In a broad sense, spirituality describes an individual’s relationship with what is transcendent and beyond the physical, an experience shared by both religious and nonreligious individuals.3 The spiritual aspect of humanity seeks to determine meaning, purpose, and value in life. Spirituality is by nature relational and can involve an individual’s relationship with God, nature, ideas or beliefs, and other individuals. In contrast, religion is a particular set of beliefs and practices shared by a larger community which describes or explains their relationship with the transcendent. An important consequence of this distinction is that many individuals are spiritual, but not necessarily religious, while others define their spirituality through religious beliefs. For the purpose of this article, the following definition for spirituality will be used, which was developed in 2013 at the International Consensus Conference on Improving the Spiritual Dimension of Whole Person Care in Geneva, Switzerland:

Spirituality is a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred. Spirituality is expressed through beliefs, values, traditions, and practices. 4

Intuitively, it would seem that maintaining a healthy spiritual life promotes overall wellness both personally and professionally. Data from the Pew Research Center in 2017 reveal that 75% of Americans claim to be “spiritual,” with a growing trend who identify as spiritual but not religious (27% compared with 19% in 2012).5 Similarly, a Gallup poll from 2018 showed that four of five Americans claim to “believe in God.”6 In 2012 members of the American College of Surgeons completed a survey regarding their personal health habits and wellness practices. Interestingly, the top three strategies employed for maintaining wellness and avoiding burnout were as follows: finding meaning in work, having protected time for family, friends, and relationships, and focusing on what is most important in life.7 These strategies are firmly connected to spirituality, demonstrating the significance of meaning, value, and relationships among US surgeons. When asked directly, 25% of surgeons felt religion and spirituality were “essential” strategies for preventing burnout, whereas another 26% felt this was “moderately important.”

Additionally, the spiritual aspect of healing can easily be overlooked when caring for patients. Most patients want physicians to address their spiritual beliefs and needs, but many physicians feel inadequately prepared for this task and uncomfortable discussing spiritual issues with patients and families.8 Surgeons are less likely to discuss religious or spiritual concerns with patients compared with other specialties such as family medicine and psychiatry.9,10 However, from the patient’s perspective, these concerns remain relevant. A study of orthopedic and general surgery patients from the University of South Alabama revealed that religious beliefs and faith were vitally important during the experience of a major injury or illness. Not unexpectedly, the majority of patients agreed that surgeons should be aware of their patients’ religious beliefs and should take a spiritual history. Approximately 73% of general surgery and 57% of orthopedic patients stated that trust in their surgeon would increase if they inquired about their spiritual beliefs.11

The purpose of this study was to assess whether spirituality plays an important role in the well-being of US plastic surgeons and residents, and whether spirituality is viewed as an important component of patient care. With our mission being to “restore and make whole,” consideration should be given to those aspects of healing that involve the spiritual nature, thereby helping patients heal in a more complete manner.

METHODS

An anonymous and voluntary email survey was distributed to 3375 members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) during the months of April through June of 2020, with a total of four reminder e-mails sent throughout the 6-week time period. The survey distribution included 2230 active members of ASPS and 1149 resident members, all who practice or train within the United States. The surveyed population was deemed to be demographically representative of the entire US-based ASPS membership by ASPS. The survey consisted of 18 multiple-choice questions with answer choices based on a descriptive five-point Likert scale and ranking by priority (Table 1). The questions consisted of two groups designed specifically to assess the importance of spirituality in maintaining wellness among plastic surgeons, and secondly the influence spirituality has on the surgeon–patient relationship and patient care. Four additional questions provided demographic information, including age, gender, years in practice, and geographic location. Several questions were adapted from the Belief into Action scale, a previously validated measure of religious commitment.12

Table 1.

Survey Questions

| 1. Which gender identity do you most identify as? |

| 2. What category best represents your age? |

| 3. How many years have you been in practice? |

| 4. Please select the geographic location in which you currently practice. |

| 5. My personal spiritual beliefs have an impact on how I take care of patients clinically. |

| 6. The spiritual beliefs of my patients have a significant impact on their ability to heal and recover from surgery. |

| 7. It is appropriate to discuss my spiritual beliefs with a patient or participate in praying with a patient. |

| 8. I routinely consider my patient’s spiritual beliefs when providing care, and feel comfortable discussing spiritual beliefs with patients. |

| 9. Attending religious services is an important and regular activity for me. |

| 10. I regularly spend time praying or meditating, and reading religious scriptures/literature. |

| 11. I intentionally make an effort to conform my life to the teachings of my spiritual beliefs and religious faith. |

| 12. My spiritual beliefs provide a healthy framework for handling conflict, suffering, and loss. |

| 13. My personal spiritual beliefs contribute positively to my emotional well-being. |

| 14. I spend time reflecting on things I can improve about myself, my life, and my professional role. |

| 15. Feeling compassion for others is a regular part of how I work. |

| 16. As a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, my spiritual beliefs and practices have provided me increased support and guidance. |

| 17. Which of the following is the highest priority in your life now (most valued)? |

| 18. Rank in order or priority which of the following you consider the most effective in helping you overcome periods of emotional exhaustion and burnout. |

Statistical analysis of the results was performed using StataCorp 2019 software. Questions in the study included demographic questions, rank in priority, and multiple-choice questions using a five-point Likert scale (one being strongly agree and five being strongly disagree). Descriptive statistics were completed for the demographic variables and question 11. For question 17, a two-sided Fisher exact test was used to test for significant association with each of the demographic variables. Nonparametric tests were conducted to assess associations between Likert scale answers and gender identity, region of practice, age group, and years in practice.

RESULTS

A total of 431 completed surveys were received for a response rate of 12.7%. (See survey, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which displays the survey results. http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/B812.) Demographic data are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The majority of participants were men (66%). For statistical analysis, participant age distribution was categorized as those under age 35 (27%), age 35–54 (39%), and age 55 years and older (33%). In a similar fashion, the nine geographic regions used in the annual ASPS report were condensed into four groups. The majority of participants were from the Midwest and South regions of the United States. When asked how many years have you been in practice, 49% reported less than 10 years, while 28% reported being in practice 10–24 years, and 23% reported 25 years or more.

Table 2.

Demographic Data

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender identity | |

| Men | 286 (66.4) |

| Women | 141 (32.7) |

| Other | 4 (0.9) |

| Age group | |

| Under 35 | 118 (27.4) |

| 35–54 | 169 (39.2) |

| 55 and over | 143 (33.2) |

| Years in practice | |

| <10 | 209 (48.5) |

| 10–24 | 121 (28.1) |

| >25 | 100 (23.2) |

Table 3.

Participant by Geographic Region

| Geographic Region | Responses | Percentile (%) |

|---|---|---|

| New England, Middle Atlantic (Northeast) CT, ME, MA, NH, RI, VT, NJ, NY, PA |

86 | 20 |

| East North Central, West North Central (Midwest) IL, IN, MI, OH, WI, IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, ND, SD |

104 | 24 |

| East South Central, West South Central, South Atlantic (South) AL, KY, MS, TN, AR, LA, OK, TX, DE, DC, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV |

147 | 34 |

| Mountain, Pacific (West) AZ, CO, ID, MT, NV, NM, UT, WY, AK, CA, HI, OR, WA |

93 | 22 |

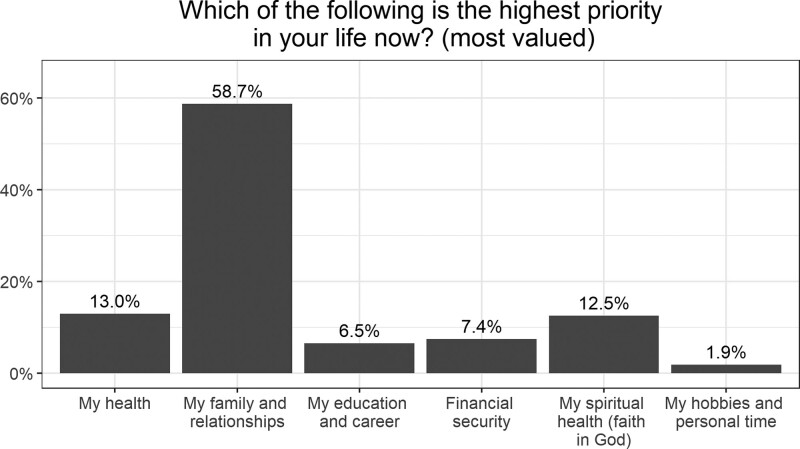

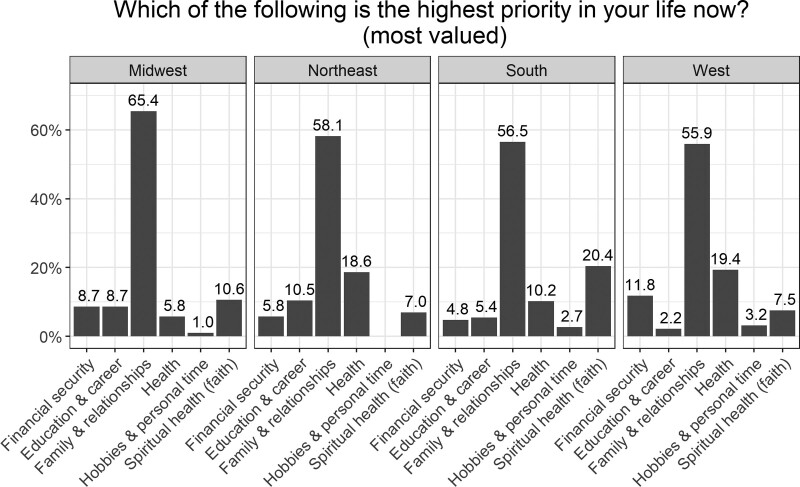

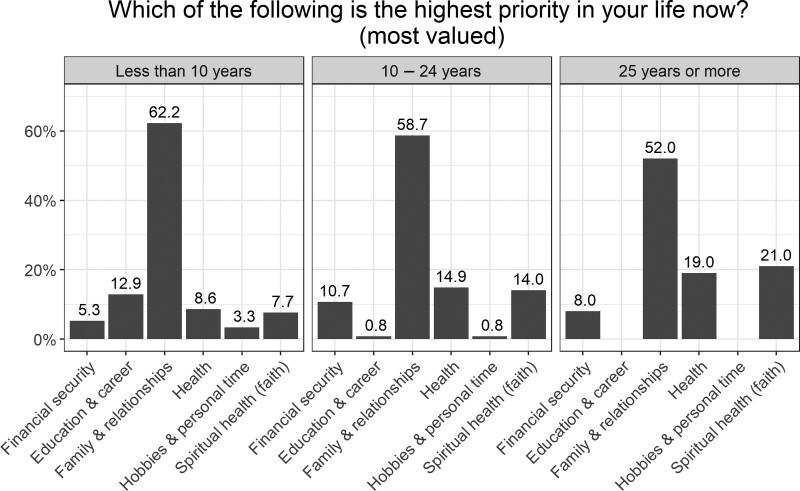

When asked what is the most important priority in your life, the majority of participants ranked “family and relationships” as being the highest (Fig. 1). A statistically significant association was evident between geographic region and choice of highest priority, with a P value of 0.002 (Fig. 2). Participants in the South (10.2%) and Midwest (5.8%) were less likely to rank personal health as their highest priority compared with those from the Northeast (18.6%) and West (19.4%). While the majority of participants under the age of 35 ranked “family and relationships” as their highest priority, this age group was more likely to rank “education and career” as their highest priority (18.6%) compared with those in the 35–54 (3.6%) and 55 and over groups (0%). Conversely, those under 35 were less likely to rank “spiritual health and faith in god” as their highest priority compared with the older age groups (P = 0.001). A statistically significant association was observed between years in practice and choice of highest priority (P = 0.001). Participants in practice 25 years or more were more likely to choose “spiritual health and faith in God” as their highest priority (21%) compared with those in practice for 10–24 years (14%) and those in practice for less than 10 years (7.7%; Fig. 3). No statistically significant association was found between gender identity and choice of highest priority.

Fig. 1.

Demonstration of which categories were prioritized most by respondents.

Fig. 2.

Geographic region vs highest priority choice (P = 0.002).

Fig. 3.

Years in practice vs highest priority choice.

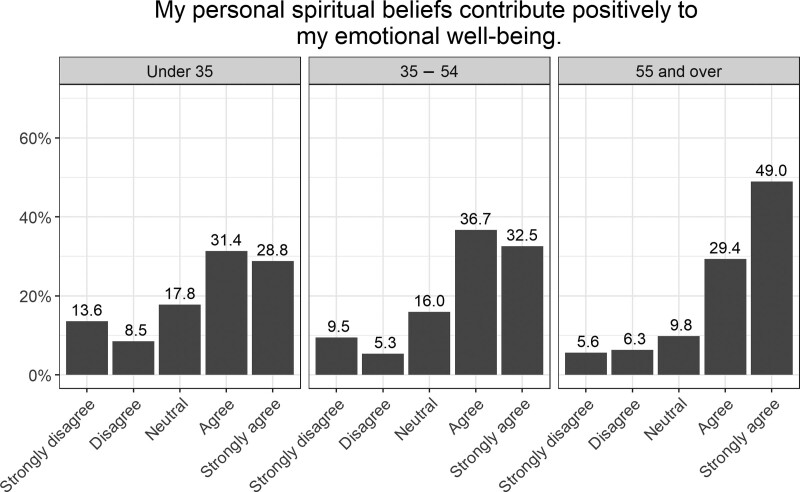

When asked whether attending regular spiritual services is an important activity, a statistically significant difference was observed between men (41%) and women (32%), (P = 0.013). Participants in the Midwest and the South were more likely to agree that spiritual beliefs play an important role in the healing process for patients and that discussing spiritual beliefs or praying with patients is appropriate compared with those in the Northeast and West regions (P value: 0.024 and 0.018, respectively). In general, as participant age and years in practice increased, so did the level of statistically significant agreement for the majority of the Likert-style questions. For example, a P value of less than 0.001 exists between age groups regarding agreement to the question of whether “personal spiritual beliefs contribute positively to my emotional well-being” (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Impact of spiritual beliefs on well-being by age group.

The majority of participants reported that personal spiritual beliefs and faith contribute positively to emotional well-being (33% agree and 37% strongly agree). Similarly, 65% agreed or strongly agreed that their spiritual beliefs provide a healthy framework for handling conflict, suffering, and loss. In total, 56% reported intentionally making an effort to conform their life to personal spiritual beliefs or religious faith. However, when asked about whether attending religious services is a priority, most participants reported they disagreed or strongly disagreed (47%) compared with 38% who agreed or strongly agreed. Additionally, a large portion reported they did not spend regular time in prayer, meditation, or reading religious texts (23% strongly disagreed, 22 % disagreed).

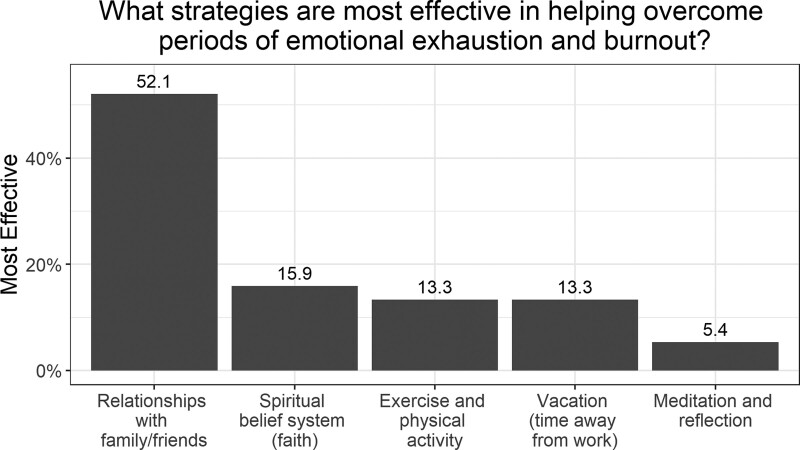

When asked what strategy was the most effective in overcoming exhaustion and burnout, participants ranked “relationships with family and friends,” “exercise and physical activity,” and “vacation (time away from work)” the highest, with reliance upon a “spiritual belief system (faith)” and “meditation and reflection” being the least effective (Fig. 5). The overwhelming majority reported spending time in self-reflection to improve aspects of their personal and professional lives (93% agreed or strongly agreed). Similarly, the majority of participants (97%) reported that feeling compassion for others is a regular part of their work. More than half (51%) reported that as a result of the COVID-19 global pandemic, their spiritual beliefs and practices have provided increased support and guidance.

Fig. 5.

Display of which strategies were most effective among respondents in overcoming emotional exhaustion and burnout.

DISCUSSION

Spirituality is an important component of wellness for plastic surgeons and residents, with the majority of participants reporting that spiritual beliefs contribute positively to their emotional well-being. Approximately two-thirds of participants agreed or strongly agreed their spiritual beliefs provide a healthy framework for handling conflict, suffering, and loss. Interestingly, when asked specifically about religious practices, the results differ somewhat, with only 38% reporting that attending religious services is a priority. Similarly, only 40% reported regular participation in prayer, meditation, and reading religious texts or scriptures. These results are consistent with known national trends of individuals claiming to be spiritual but not necessarily religious. Geographical differences were apparent in our data suggesting the significance of religion and spirituality vary across the country. Regarding the religious characteristics of US physicians compared with the general population, previous data showed that physicians are more likely to consider themselves spiritual but not religious.13 Another study demonstrating the importance of religious and spiritual beliefs among physicians was published in 2017 from the Mayo Clinic, showing 65% claimed to believe in God and 63% described religion as important in their life.14 However, only 53% of surgeons who participated reported that they pray daily.

The distinction between spirituality and religious belief systems is important. Based on the previously mentioned definition, spirituality involves the transcendent, but also includes the search for meaning and purpose, and the experience of relationships. These components of spirituality are directly related to the wellness strategies reported most important to plastic surgeons in our study. The most effective strategy for handling emotional exhaustion and preventing burnout was cultivating relationships with family and friends. Although the specific strategy of relying upon a spiritual belief system was ranked less important, the assumption could be made that plastic surgeons value intrinsic aspects of spirituality (relationships and meaning), rather than a defined spiritual belief system that relates more closely to religion. Data from the American College of Surgeons survey revealed the top three strategies employed for maintaining wellness and avoiding burnout were finding meaning in work, having protected time for family, friends, and relationships, and focusing on what is most important in life.5 Similar strategies at preventing burnout are described for plastic surgeons by Khansa and Janis, focusing on physical and intellectual health, maintaining autonomy, and finding purpose in work.1

The strategies described for improving psychological health are inherently linked to one’s spirituality—that is, finding meaning in one’s work and developing relationships with friends and family, and these were protective of wellness and treated or prevented burnout. Our survey data show that the majority of plastic surgeons value time spent with friends and family as their number one priority in their life, and time spent with family and friends was most often chosen as the most effective thing in helping them overcome burnout and emotional exhaustion. Respondents largely indicated that they agreed to the statements that their personal spiritual beliefs contributed positively to their emotional well-being. This congruency between evidence-based strategies to decrease burnout and our survey results indicates that developing a culture that allows for spirituality, personal growth, and time for family and friendships is paramount in developing a workforce of healthy surgeons.

With regard to spirituality and patient care, most plastic surgeons agreed their personal spiritual beliefs impact how they provide clinical care, and that spirituality plays an important role in the healing and recovery process of patients. This is consistent with literature from other medical specialties demonstrating that spiritual well-being is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Garimella et al reported on recent data showing how spiritual well-being was associated with better rehabilitation outcomes and life satisfaction among traumatic brain injury patients, and the positive correlation between spirituality and quality of life in breast cancer and prostate cancer survivors.15 A more detailed account of the existing literature supporting the role of spirituality and health outcomes is beyond the scope of this article, but the authors would recommend the Handbook of Religion and Health written by Dr. Harold Koenig and a review article published in 2015 by Dr. Koenig as well.16,17

An important finding is that although plastic surgeons agree spirituality is a significant aspect of healing, most do not feel comfortable discussing their own spiritual beliefs with patients or praying with patients. Reasons for this finding may include the desire not to proselytize or impose beliefs onto another individual when a power discrepancy exists such as the surgeon–patient relationship. Surprisingly, a large portion of participants (42%) report routinely considering a patient’s spiritual beliefs when providing care and feel comfortable discussing those beliefs. However, 26% remained neutral and 32% of participants reported they did not routinely consider patients’ spiritual needs. Many reasons may exist why surgeons do not routinely address spiritual issues when providing care—for example, inadequate training, lack of time and expertise, and feeling uncomfortable.6 One practical approach is for the surgeon to consider recommending a referral to the chaplaincy services offered at each institution.18 Table 4 outlines the various responsibilities of chaplains.

Table 4.

Indication and Role of the Chaplain

| Role of the Chaplain | Indications for Chaplain Referral |

|---|---|

| Spiritual/emotional support | Patient isolation, fear, loneliness |

| Prayer | Unmet spiritual needs |

| Communication | Complex family dynamics |

| Presence/listening | Lack of social support |

| Negotiate complex family dynamics | Presenting difficult diagnosis, bad news |

| Grief and bereavement counseling | Grieving or emotional distress |

Spiritual health has been recognized across the world as an important component of wellness and quality of life. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Group has developed an international definition for quality of life as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns. It is a broad ranging concept affected in a complex way by the person’s physical health, psychological state, personal beliefs, social relationships and their relationship to salient features of their environment.”19,20 The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations requires addressing the spiritual and religious needs of patients.21 Similarly, the American College of Surgeons’ Code of Professional Conduct outlines the specific responsibility of each surgeon to “acknowledge patients’ psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual needs.”22

Over the past several decades, US medical schools have recognized the importance of this concept and have implemented spirituality courses into their academic curricula, an effort initially started by Dr. Christina Puchalski, Director of the George Washington University School of Medicine Institute for Spirituality and Health. Given the findings of this study and other supporting literature, the significance of maintaining spiritual health is apparent, especially as issues related to spirituality are so important for surgeon wellness and avoiding burnout. In fact, Dr. Puchalski describes physician burnout as “spiritual fatigue,” which communicates the loss of purpose, meaning, and relationships that surgeons prioritize and value.23 A search for purpose and connection through relationships is fundamental to a satisfying career in medicine, and individuals are intrinsically motivated to find purpose and connection.

Limitations to our data include the low response rate of 12.7%, although this is above the average response rate of official ASPS surveys, which is 11%.24 One reason for this may be survey fatigue, as the number of email surveys has certainly increased over the years. Also, many potential respondents may not have felt comfortable participating in the survey due to the more personal nature of the subject matter, whereas others may have been more likely to participate because of an inherent interest in spirituality. There is the possibility of sampling bias because not all active members and resident-members of ASPS were contacted, but only a subset of the group, although the subgroup was specifically constructed by ASPS to be representative of the whole. Other potential biases that might affect data integrity with surveys include “extreme bias” (choosing the extreme options in a Likert scale question model) and “acquiescence bias” (where respondents choose answers based on what they think the reviewers want to hear). Some bias is possible due to geographic differences in spiritual/religious practices and beliefs.

CONCLUSIONS

The essence of plastic surgery can be summarized in Tagliacozzi’s famous words, “We restore, rebuild, and make whole those parts which nature hath given, but which fortune has taken away.” The healing process involves the whole person, and the surgeon–patient relationship by necessity involves the spiritual experience of both individuals. As plastic surgeons, we must continue to rebuild the whole person, “Not so much that it may delight the eye, but that it might buoy up the spirit, and help the mind of the afflicted.”25

In conclusion, spirituality is an important component of maintaining wellness for plastic surgeons, and spirituality is recognized by plastic surgeons as an important aspect of the healing process for patients. Efforts should be made to promote spiritual health among the surgical community both during training and in practice. It is hoped that such efforts will lead to less burnout and overall better patient care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 7 October 2021.

Disclosure: Dr. Janis receives royalties from Thieme and Springer publishing. All the other authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. This article was funded, in part, through an educational grant from the Michael D. Hendrix Burn Research Center at Johns Hopkins Bayview.

This study is an officially sponsored survey of the ASPS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Khansa I, Janis JE. A growing epidemic: plastic surgeons and burnout—a literature review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:298e–305e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart AM, Crowley C, Janis JE, et al. Survey based assessment of burnout rates among US plastic surgery residents. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85:215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sulmasy DP. Spirituality, religion, and clinical care. Chest. 2009;135:1634–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puchalski CM, Vitillo R, Hull SK, et al. Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: reaching national and international consensus. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:642–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipka M, Gecewicz C. More Americans now say they're spiritual but not religious. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2017. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/06/more-americans-now-say-theyre-spiritual-but-not-religious/. Accessed September 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hrynowski Z. How many Americans believe in God? Gallup, Inc; 2018. Available at https://news.gallup.com/poll/268205/americans-believe-god.aspx. Accessed September 20, 2021.

- 7.Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255:625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:400–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasinski KA, Kalad YG, Yoon JD, et al. An assessment of US physicians’ training in religion, spirituality, and medicine. Med Teach. 2011;33:944–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson HG, Fleenor D, Lerner SM, et al. Teaching third-year medical students to address patients’ spiritual needs in the surgery/anesthesiology clerkship. Mededportal. 2018;14:10784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor D, Mulekar MS, Luterman A, et al. Spirituality within the patient-surgeon relationship. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig H, Wang Z, Al Zaben F, et al. Belief into action scale: a comprehensive and sensitive measure of religious involvement. Religions 2015;6:1006–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curlin FA, Lantos JD, Roach CJ, et al. Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson KA, Cheng MR, Hansen PD, et al. Religious and spiritual beliefs of physicians. J Relig Health. 2017;56:205–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garimella R, Koenig HG, Larson DL, et al. Of these, faith, hope, and love: assessing and providing for the psychosocial and spiritual needs of burn patients. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenig H, King D, Carson V. Handbook of Religion and Health. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: a review and update. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hultman CS, Saou MA, Roach ST, et al. To heal and restore broken bodies: a retrospective, descriptive study of the role and impact of pastoral care in the treatment of patients with burn injury. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. Available at https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/. Accessed February 1, 2021.

- 20.Willemse S, Smeets W, van Leeuwen E, et al. Spiritual care in the intensive care unit: An integrative literature research. J Crit Care. 2020;57:55–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CAMH: Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Surgeons: Statements on Principles. Code of Professional Conduct. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons;2021. Available at https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/stonprin#code. Accessed September 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puchalski CM, Guenther M. Restoration and re-creation: spirituality in the lives of healthcare professionals. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6:254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Email communication: Dated 6/7/2020 Christopher Simmons, Manager, Registry and Data Analytics, American Society of Plastic Surgeons. csimmons@plasticsurgery.org.

- 25.Tagliacozzi G. De curtorum chirurgia per insitionem, Venezia, 1597. Margaret and J. J. Longacre Memorial Library of Plastic Surgery, in the Boston Medical Library (f RD118.T12 c.2). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.