Abstract

Objective:

Intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) in somatosensory cortex can restore sensation to people with spinal cord injury or other conditions. One potential challenge for chronic ICMS is whether neural recording and stimulation can remain stable over many years. This is particularly relevant since the recording quality from implanted microelectrode arrays can degrade over time and limitations in stimulation longevity have been considered a potential barrier to the clinical use of ICMS. Our objective was to evaluate recording stability on intracortical stimulated sputtered iridium oxide (SIROF) and non-stimulated platinum electrodes in somatosensory and motor cortex in a human participant across a long period of implantation. Additionally, we measured how ICMS was able to evoke sensations over time.

Approach:

In a study investigating intracortical implants for a bidirectional brain-computer interface, we implanted microelectrode arrays with SIROF tips in the somatosensory cortex of a human participant with a cervical spinal cord injury. We regularly stimulated these electrodes to evoke tactile sensations on the hand. Here, we quantify the stability of these electrodes in comparison to non-stimulated platinum electrodes implanted in the motor cortex over 1500 days in two ways: recorded signal quality and electrode impedances. Additionally, we quantify the perceptual stability of ICMS-evoked sensations using detection thresholds.

Main results:

We found that recording quality, as assessed by the number of electrodes with high-amplitude waveforms (> 100 μV peak-to-peak), peak-to-peak voltage, noise, and signal-to-noise ratio, generally decreased over time on stimulated SIROF and non-stimulated platinum electrodes. However, stimulated SIROF electrodes were much more likely to continue to record high-amplitude signals than non-stimulated platinum electrodes. Interestingly, the detection thresholds for stimulus-evoked tactile sensations decreased over time from a median of 31.5 μA at day 100 to 10.4 μA at day 1500, with the most substantial changes occurring between day 100 and 500.

Significance:

These results provide evidence that ICMS in human somatosensory cortex can be provided over long periods of time without deleterious effects on recording or stimulation capabilities. In fact, the sensitivity to stimulation improved over time.

Keywords: intracortical microstimulation, microelectrode arrays, somatosensory cortex, brain-computer interfaces

1. Introduction

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) can be used to restore functional motor control by connecting the brain to an effector or assistive device and bypassing the spinal cord and limbs. Indeed, in recent years intracortical implants in motor cortex have enabled high-performance BCI control [1–5]. Additionally, electrical microstimulation through intracortical implants in somatosensory cortex can generate tactile percepts in people with spinal cord injury [6–8]. As these devices must be implanted surgically, microelectrode arrays need to function for long periods of time to be clinically practical.

The stability of microelectrode arrays in motor cortex has been well studied in non-human primates [9–11]. Additionally, there are several reports on signal quality and stability for electrodes implanted in human motor cortex [3,12–14]. Although intersubject variability is high, signals can be reliably recorded for up to 3–5 years when devices do not fail, although the quality of these recordings deteriorates over time. However, whether electrodes primarily used for intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) can record and stimulate effectively over clinically relevant timelines is unknown in humans, especially given that stimulation itself may have detrimental effects on the electrodes and the surrounding neural tissue [15–18].

In order to study the sensations evoked by ICMS in human somatosensory cortex, we implanted intracortical microelectrode arrays into the somatosensory cortex of a participant with C5/C6 spinal cord injury. With these devices, ICMS can elicit tactile percepts localized to the hand on the majority of implanted electrodes. Prior to this clinical study, a series of experiments in non-human primates were performed to establish safe stimulation limits using microelectrode arrays. These studies demonstrated that frequent microstimulation over six months did not appear to cause more damage to the cortex than what could be expected from implanting the devices themselves, that there were minimal effects on the characteristics of the electrode-tissue interface, and that that there were no detectable behavioral changes in the animals’ abilities to perform dexterous behaviors that require somatosensory feedback [19,20]. Other studies have also demonstrated that signals can be reliably recorded and that sensations can be reliably evoked over long periods of time in animals when using stimulation amplitudes up to 300 μA [17,20–22].

Given the absence of long-term human work, it is necessary to demonstrate that stimulation can be effective over long periods of time in people. Here, we present results on the stability of Utah microelectrode arrays with SIROF used for ICMS in the somatosensory cortex of a human participant over 1500 days and compare signal quality to non-stimulated platinum electrodes implanted in the motor cortex.

2. Materials and Methods

Data for this study were collected for the first 1500 days after implantation. Experiments were typically conducted in four-hour long sessions three days a week, although stimulation was not used in every session or for all four hours. Across the 1500 implant days, experiment sessions were performed on 510 days, 378 of which involved stimulation.

2.1. Participant and Implants

This study was conducted under an Investigational Device Exemption from the U.S. Food and Drug administration, approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA) and the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center Pacific (San Diego, CA), and registered at Clinical-Trials.gov (NCT0189-4802). Informed consent was obtained before any study procedures were conducted. A single subject was implanted with two microelectrode arrays (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT) in somatosensory cortex. Each electrode array consisted of 60 electrodes in a 6×10 grid, 32 of which were wired and functional. The remaining electrodes were not wired due to technical constraints related to the total available number of electrical contacts on the percutaneous connector. Electrode tips were coated with a sputtered iridium oxide film (SIROF) [6,23,24]. The participant also had two microelectrode arrays implanted in motor cortex. Each electrode array consisted of 88 wired electrodes distributed throughout a 10×10 grid. Electrode tips in motor cortex were coated with platinum. Throughout the text, we will refer to the stimulated electrodes as “SIROF-sensory” and the non-stimulated electrodes as “platinum-motor.”

2.2. Stimulation protocol

Stimulation was delivered using a CereStim R96 multichannel microstimulation system (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT). Pulse trains consisted of cathodal phase first, current-controlled, charge-balanced pulses delivered at frequencies from 20–300 Hz and at amplitudes from 2–100 μA. The cathodal phase was 200 μs long, the anodal phase was 400 μs long, and the anodal phase was set to half the amplitude of the cathodal phase. The phases were separated by a 100 μs interphase period. At the beginning of each test session involving stimulation, we sequentially stimulated each electrode first at 10 μA and 100 Hz for 0.5 s and then at 20 μA and 100 Hz for 0.5 s. During these trials, the interphase voltage on each electrode was measured at the end of the interphase period, immediately before the anodal phase [25]. If an electrode’s measured interphase voltage was below −1.5 V, the electrode was disabled for the day. This step was performed to minimize stimulation on electrodes that might potentially experience high voltages, which could result in irreversible damage. Typically, 2 to 8 electrodes were removed from the test set each day. The electrodes that were removed tended to change from day to day suggesting that the high interphase voltage was due to poor contact between the percutaneous connector and the stimulation cable. On any given day, tactile sensations localized to the hand were elicited on 50–60 of the 64 electrodes with stimulation. All electrodes, except those exhibiting high interphase voltages, were stimulated at suprathreshold amplitudes, typically 60 μA, at least once a month during a monthly survey of elicited tactile sensations. We additionally limited stimulation on individual electrodes to a maximum of 15 seconds of stimulation at 100 Hz, at which point stimulation would be disabled for an equivalent amount of time, which is thought to help reduce neuronal loss [26]. Some electrodes were used more frequently for other tasks involving stimulation. One electrode in particular, electrode 19, was used more than any other electrode for stimulation tasks and additional analysis was conducted on this electrode. This electrode was selected because it consistently evoked salient percepts even at lower stimulus amplitudes.

We conducted experiments exclusively at the participant’s home from day 364 to 498 for reasons unrelated to the study. Experiments conducted in the home used a duplicate version of the lab hardware and were subject to different environmental noise characteristics than the laboratory. Stimulation experiments were not conducted during this time because of clinical regulatory requirements. However, we did record neural data from electrodes in somatosensory cortex during this time and these data are included here. After implant day 498, stimulation experiments continued both at home and in the laboratory after regulatory modifications had been approved.

To calculate how much charge was injected on each electrode, we summed all pulses delivered to each electrode across all stimulation experiments using the charge delivered during the 200 μs cathodal phase.

2.3. Stability metrics

To quantify the stability of stimulated SIROF electrodes in somatosensory cortex and non-stimulated platinum electrodes in motor cortex, we measured recorded signal quality, electrode impedances, and stimulation detection thresholds over time. Signal quality and impedance were compared between stimulated SIROF electrodes in somatosensory cortex and non-stimulated platinum electrodes in motor cortex. Recording quality was evaluated using four metrics: (1) the number of electrodes with high-amplitude recordings, (2) peak-to-peak voltage, (3) noise, and (4) signal-to-noise ratio. Ideally, a clinical device would be able to record many neurons with large peak-to-peak voltages, have low noise levels, and therefore, a high signal-to-noise ratio for the duration of the implant.

Another key metric of electrode stability, particularly for stimulated electrodes, is the electrode impedance. Increases in the impedance could result in higher required voltages at the electrode-tissue interface for constant-current stimulation pulses, resulting in potentially irreversible reduction and oxidation reactions [25]. Therefore, it is necessary for electrode impedances to remain stable over the length of the implant.

Finally, the ability to elicit sensations with ICMS must necessarily be maintained. We used detection thresholds as a sensitive metric of perception to determine the minimum charge required to induce tactile percepts. Since increasing the stimulus charge has a direct effect on safety [18], detection thresholds should not systematically increase over the length of implantation. Increasing thresholds could result in an inability to evoke tactile percepts with parameters that have been shown to be safe.

2.4. Neural recordings

At the beginning of each session, we recorded neural data while the participant was at rest in a quiet room. These data were processed offline and used to assess signal quality. Neural signals were recorded using the NeuroPort data acquisition system (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT) and were sampled at 30 kHz with a 750 Hz first order high pass filter [27]. Each time the voltage crossed a pre-defined threshold of −4.5 times the baseline root-mean-square on each electrode, the time of the crossing and a 48-sample (1.6 ms) snippet of the signal, starting 11 samples before the crossing, was saved for offline analysis.

2.5. Signal quality

Neural activity recorded at rest was processed offline in MATLAB (Natick, MA). The peak-to-peak voltage was calculated individually for every snippet. Only the snippets with peak-to-peak voltages within the top 2% on a given electrode were used for analysis. This method was used to isolate the largest amplitude neural recordings and provide an unbiased estimate of the capacity of each electrode to record signals. More typical single-unit based analysis, especially over the long time periods of this study, could be subject to biases introduced by manual spike sorting [28]. We therefore selected analysis methods that did not require spike sorting. The largest 2% of the snippets for each electrode were averaged and the peak-to-peak voltage was calculated. If the firing rate of all the snippets on any electrode was less than 1.67 Hz, or the peak-to-peak voltage of the averaged signal was less than 30 μV, the electrode was excluded from analysis. We used 1.67 Hz because it ensured we would have at least two isolated waveforms for analysis when using only the top 2% of snippets across one minute of recording. Electrodes containing snippets which had peak-to-peak voltages over 100 μV were considered to be high-amplitude recordings. The noise metric was calculated as three times the standard deviation of the first five time samples of all action potential snippets. As the first five values of each snippet capture time points prior to the threshold crossing event, they provided a window of data representing noise in the recordings. A similar method for calculating noise was used in a previous publication examining single-unit recording stability in motor cortex [13]. Signal-to-noise ratio was calculated as the magnitude of the peak of the averaged waveform divided by the calculated noise.

The filter applied to the recorded neural data was changed at day 200 from a fourth order 250 Hz high-pass Butterworth filter to a first order 750 Hz high-pass Butterworth filter to reduce the effects of stimulus artifact. The increased cut-off frequency resulted in an overall decrease in noise and, therefore, an increase in SNR [27]. Because of this, we separated data into pre-and post- filter change epochs for all signal quality analysis. All reported statistical results for signal quality are from data collected after the filter change.

2.6. Impedances

Electrode impedances at 1 kHz were measured at the beginning of each test session for every electrode. Impedances were measured using the impedance mode built into the NeuroPort patient cable data acquisition system (Blackrock Microsystems, Salt Lake City, UT), which involves delivering a 1 kHz, 10 nA peak-to-peak sinusoidal current for 1 s to each implanted electrode.

2.7. Detection thresholds

Detection thresholds were calculated on at least two electrodes each day that stimulation was provided. One of these two was electrode 19 while the other electrode tested was taken sequentially from a list of seven electrodes (electrodes 8, 11, 28, 34, 40, 54, and 57). These electrodes were selected because they spanned both arrays and consistently generated perceptible sensations. Detection thresholds were calculated using a three-down, one-up staircase method [29]. This involved a two-alternative forced choice task in which the participant was presented with a stimulus pulse train during one of two 1 s intervals separated by a 1 s delay period and had to select which interval contained the pulse train. The amplitude of the stimulus was increased by 2 dB after an incorrect response and decreased by 2 dB after three correct responses. After five changes in direction, the trial was stopped and the threshold was calculated as the average of the last ten values before the end of the trial.

2.8. Data analysis and statistics

We tested for changes in signal quality, impedance, and detection thresholds over time using linear regression. Data points that had values more than three scaled median absolute deviations away from the median were excluded from analysis as outliers. Impedances and detection thresholds followed an exponential decay so the regressor, days post-implantation, was log-transformed prior to regression. Median data on SIROF-sensory electrodes were compared to data on platinum-motor electrodes using ANCOVA. We used ANCOVA because it allowed us to assess significant differences between mean values on SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes by accounting for changes over time as a covariate, producing an ANCOVA adjusted means comparison. Additionally, we were able to assess the interaction of the two factors, time and stimulation condition, to determine if the changes over time were significantly different between SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes, producing an ANCOVA interaction term. We also compared the amount of charge injected on each electrode to signal quality metrics using linear regression with the x-axis log-transformed. All p-values reported are for the coefficient of the regression slope unless otherwise indicated.

For detection thresholds measured across all electrodes at specific time points, we analysed the differences between blocks using Kruskal-Wallis tests and Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post-hoc tests. A non-parametric test was used because the detection data across electrodes were non-normal at each time point, as determined with an Anderson-Darling test. We quantified the spatial clustering of detection thresholds on the arrays using Moran’s I which is a method to assess spatial autocorrelation [30]. The weighting scheme considered only adjacent electrodes as neighbors. The significance for Moran’s I was determined using a z-test comparison to the predicted outcome of a random distribution. For visual clarity, interquartile ranges (IQRs) shown in figures were smoothed with a nine-point moving average filter with a triangular kernel. All statistical analysis was performed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

All p-values were considered to be significantly different than zero or from each other at the P < 0.05 level. Raw p-values are reported throughout unless the p-value was very small, in which case it is reported as P < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Recording stability

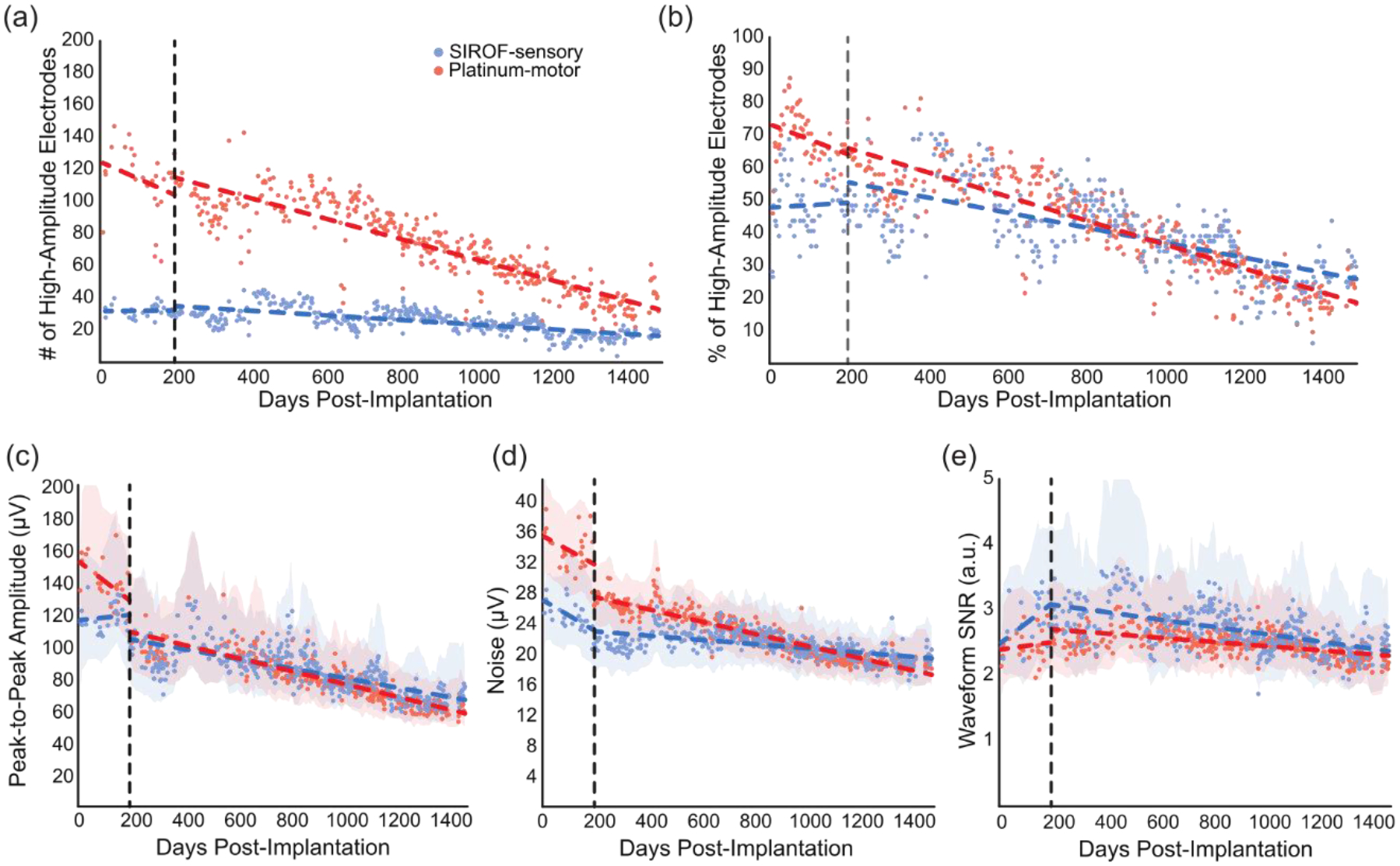

The number of electrodes with high-amplitude recordings decreased significantly over time on both platinum-motor and SIROF-sensory electrodes (P < 0.001, linear regression, figure 1(a,b)). Interestingly, the number of SIROF-sensory electrodes with high-amplitude recordings decreased less over time (slope = −5 electrodes/year) than the number of platinum-motor electrodes with high amplitude recordings (slope = −23 electrodes/year). This difference was highly significant (P < 0.001, ANCOVA interaction) and reflects a 47% loss of high-amplitude signals on SIROF-sensory electrodes and a 72% loss of high-amplitude signals on platinum-motor electrodes from day 200 to 1500. Early in the study, between days 200 and 300, we recorded high-amplitude signals on 30±3 SIROF-sensory electrodes and 101±10 platinum-motor electrodes. Late in the study, between days 1400 and 1500, we recorded high-amplitude signals on 17±4 SIROF-sensory and 38±9 platinum-motor. There were 64 SIROF-sensory electrodes and 176 platinum-motor electrodes, which favours recording a larger number of high-amplitude electrodes on platinum-motor electrodes. However, on a percentage basis, more of the SIROF-sensory recorded high-amplitude at the end of the study period (figure 1(b)).

Figure 1.

Signal quality over time. Blue points represent signal quality metrics from SIROF-sensory electrodes and red points represent platinum-motor electrodes. Dotted lines represent regression before and after day 200. Shaded areas represent the smoothed interquartile range for each data set. The dotted vertical line marks day 200, when the filter order was changed. (a) The number of electrodes on the motor and sensory arrays with high-amplitude recordings on each test day. (b) The percentage of electrodes on the motor and sensory arrays with high-amplitude recordings on each test day. There were 64 SIROF-sensory electrodes and 176 platinum-motor electrodes. (c) Median peak-to-peak voltage. (d) Median background noise. (e) Median signal-to-noise ratio.

There were significant differences in the changes in the peak-to-peak voltages, noise, and SNR on SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes (P < 0.001, ANCOVA interaction). Interestingly, the peak-to-peak voltage on SIROF-sensory electrodes decreased less over time (slope = −10.6 μV/year, P < 0.001, linear regression, figure 1(c)) than on the platinum-motor electrodes (slope = −14.2 μV/year, P < 0.001, linear regression, figure 1(c)) and the SIROF-sensory electrodes maintained a higher adjusted mean peak-to-peak voltage (P < 0.001, ANCOVA adjusted means). The noise on the platinum-motor electrodes also decreased more over time (slope = −1.0 μV/year, P < 0.001, figure 1(d)) than on the SIROF-sensory electrodes (slope = −2.9 μV/year, P < 0.001, figure 1(d)) but the SIROF-sensory electrodes maintained a lower adjusted mean noise (P < 0.001, ANCOVA adjusted means).

These changes in peak-to-peak voltage and noise resulted in the SNR decreasing more over time on SIROF-sensory electrodes (slope = −0.2 a.u./year, P < 0.001, figure 1(e)) than on platinum-motor electrodes (slope = −0.1 a.u./year, P < 0.001, figure 1(e)) due primarily to differences in how noise changed over time. This difference (P < 0.001, ANCOVA interaction) represents a decrease in SNR of 23% on SIROF-sensory electrodes and 15% on platinum-motor electrodes from day 200 to 1500. However, SIROF-sensory electrodes maintained a higher adjusted mean SNR than platinum-motor electrodes throughout the study period (P < 0.001, ANCOVA adjusted means). Early in the study, between day 200 and 300, the SNR was 2.9±0.3 on SIROF-sensory electrodes and 2.5±0.1 on platinum-motor electrodes. Later in the study, between day 1400 and 1500, the SNR had dropped by a small, but statistically significant amount to 2.4±0.5 on SIROF-sensory electrodes and 2.2±0.1 on platinum-motor electrodes. Even though there were significant differences between the SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes in terms of how SNR changed over time, this did not translate into practical differences in SNR, and SIROF-sensory electrodes maintained a higher SNR over time than platinum-motor electrodes.

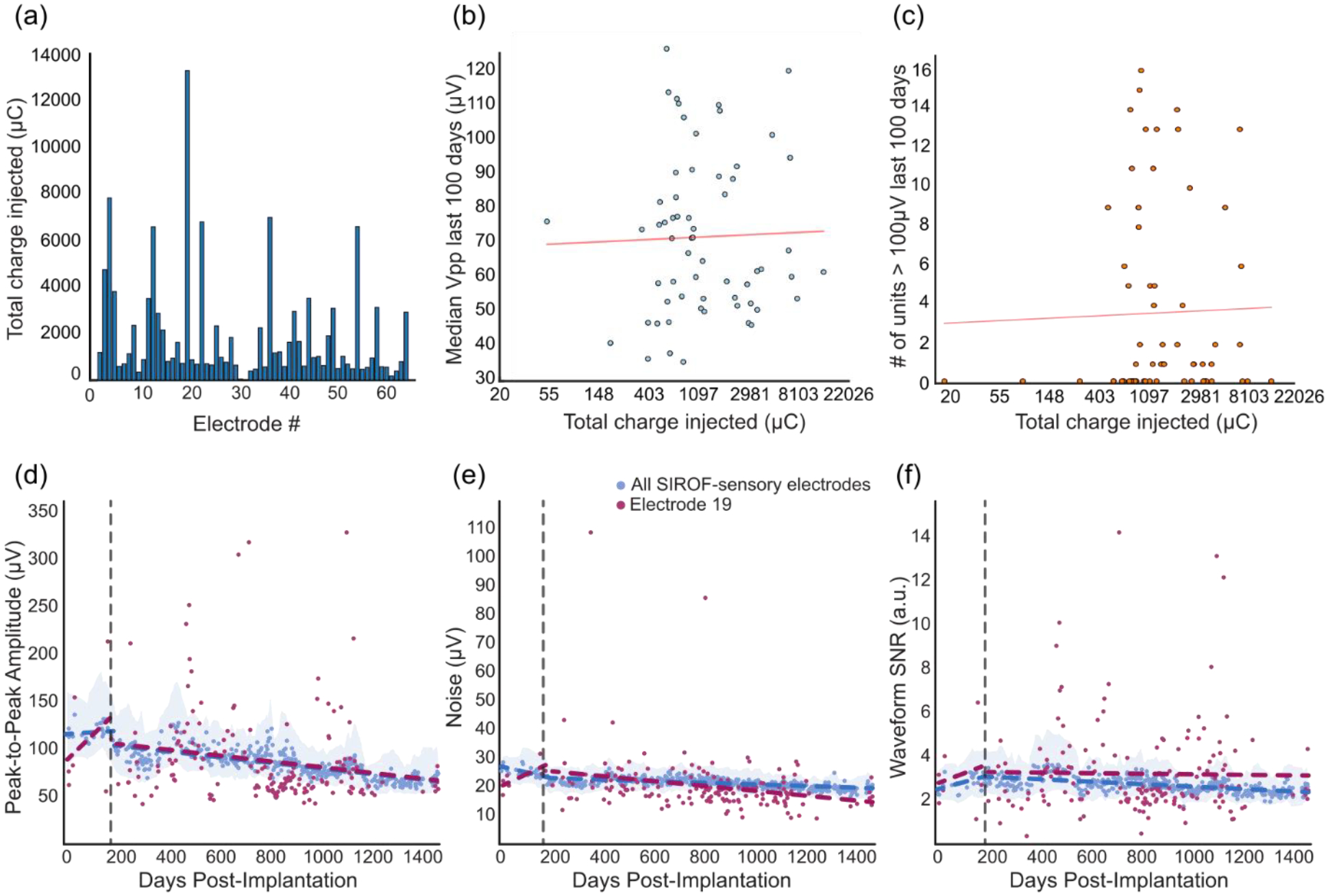

One possibility is that changes on SIROF-sensory electrodes are related to the amount of charge delivered through that electrode. To address this issue, we also investigated how the amount of charge injected on SIROF-sensory electrodes correlated with signal quality (figure 2). We compared the total charge injected on each electrode (figure 2a) with the number of high amplitude waveforms and the median peak-to-peak voltage from post-implant days 1400 to 1500. We found that there was no significant relationship between injected charge and median peak-to-peak voltage (p = 0.84, figure 2b) or the number of high amplitude waveforms recorded (p = 0.82, figure 2c). Additionally, we looked at how the signal quality metrics of a single electrode that received the most stimulation (electrode 19, figure 2a) compared to other SIROF-sensory electrodes. For reference, this electrode was stimulated during 255 out of 378 test sessions in which stimulation was used and received 13284 μC of charge injection, while most electrodes were stimulated in less than 100 test sessions with a median of 960 μC of charge injection. The detection threshold for this electrode was tested during most stimulation sessions and this electrode was additionally the most used electrode for bidirectional BCI tasks. Although the intersession variance was much larger for this electrode than the median data, neither the peak-to-peak amplitude (P = 0.92, ANCOVA interaction, figure 2(d)) nor SNR (P = 0.22, ANCOVA interaction, figure 2(f)) were significantly different over time compared to all SIROF-sensory electrodes. However, the baseline noise decreased more on electrode 19 than the rest of the SIROF-sensory electrodes (P < 0.001, ANCOVA interaction, figure 2(e)). This resulted in an adjusted mean noise that was significantly lower and an adjusted mean SNR that was significantly higher (P < 0.05, ANCOVA adjusted means) than the adjusted mean of the median noise and SNR for all SIROF-sensory electrodes. While significant, these differences were very small.

Figure 2.

Relationship between total charge injected and signal quality. (a) Histogram showing the amount of charge each electrode received over 1500 days. (b-c) Signal metrics measured from day post-implant 1400 to 1500 plotted against total charge injected for each electrode. The x-axis is log-transformed. The red line shows the log-transformed linear regression fit. (b) Median Vpp vs. charge. (c) The number of high amplitude waveforms recorded vs. charge. (d-f) Signal quality on a single electrode that received the most stimulation. Data points for all the SIROF-sensory electrodes (blue) represent median values from test days. Data points for the single electrode (red) are the measured values for each metric on each day. Dotted lines show regression across all data. Shaded areas represent the smoothed interquartile range for each for all SIROF-sensory electrodes. The dotted vertical line marks day 200 when the filter order was changed. (d) Peak-to-peak voltage. (e) Background noise. (f) Signal-to-noise ratio.

Next, we compared electrode 19 to the platinum-motor electrodes and found that the magnitude of the decrease in noise on electrode 19 over time (the slope) was not significantly different than the decrease in the median noise on the platinum-motor electrodes over time (P = 0.7786, ANCOVA interaction). However, the noise itself on electrode 19 was significantly lower than the median noise on platinum-motor electrodes (P<0.001, ANCOVA adjusted means). While the noise on platinum-motor electrodes decreased more quickly than the noise on SIROF-sensory elecrodes (figure 1(d)), this effect was not more prominent on the electrode receiving the most stimulation, suggesting that the differences in noise between platinum-motor and SIROF-sensory electrodes may have been driven by other factors such as electrode material or impedance, rather than stimulation itself.

3.2. Impedance Stability

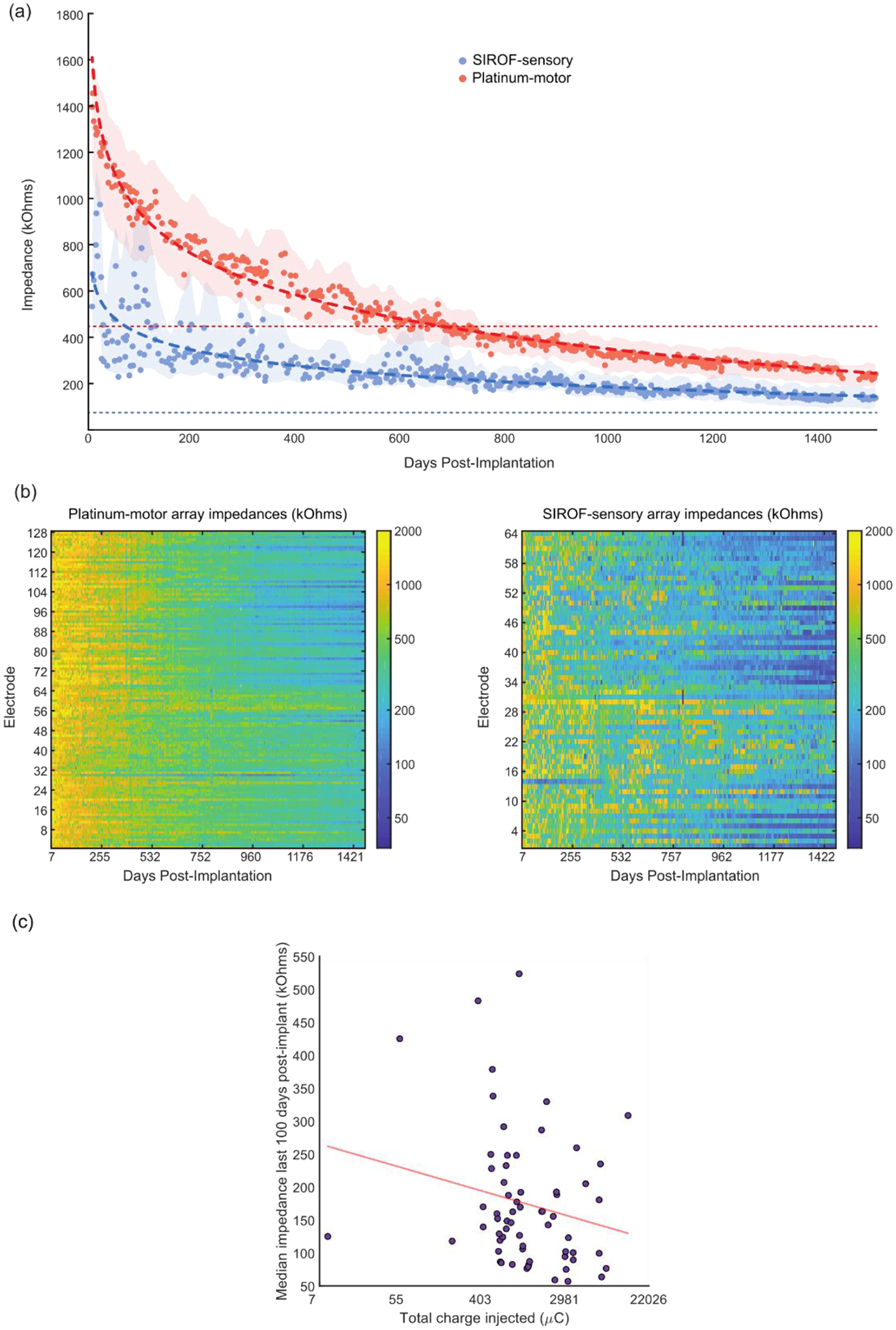

There was a large increase in the impedances at 1 kHz immediately following implantation on both platinum-motor electrodes (median pre-implant impedance: 447.5 kOhms; median day 7 impedances: 1396 kOhms) and SIROF-sensory electrodes (median pre-implant impedance: 74.5 kOhms; median day 7 impedances: 533 kOhms). After this increase, we assessed whether there was a significant change in the electrode impedances over 1500 days using linear regression (figure 3(a)). Electrode impedances decreased over time on both the SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes (P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant difference in the changes in impedance between SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes (P < 0.001, ANCOVA interaction) with a greater decrease in impedance over time on the platinum-motor electrodes. Over 1500 days, the impedance on the SIROF-sensory electrodes decreased by 79% while the platinum-motor electrode impedances decreased by 85%. The median impedances on the platinum-motor electrodes were initially much higher than the SIROF-sensory electrodes [23].

Figure 3.

Electrode impedances over time. (a) Median impedances of all electrodes plotted against days since implantation for the SIROF-sensory arrays (blue) and the platinum-motor arrays (red). Thick dotted lines represent the linear regression of the data with log-transformed days. Thin dotted lines represent the median pre-implant impedances. Shaded areas represent the smoothed interquartile range for each data set. (b) Heatmaps of electrode impedances plotted against days since implantation for the motor arrays (left) and somatosensory arrays (right). The color axis is log transformed to highlight changes over time. (c) The median impedance recorded from day post-implant 1400 to 1500 plotted against total charge injected by day 1500 for each electrode. The x-axis is log-transformed. The red line shows the log-transformed linear regression fit.

We also compared the amount of charge injected on individual SIROF-sensory electrodes to the median impedances measured from post-implant days 1400 to 1500. We found that increases in total charge injected correlated with decreases in median measured impedances, although the relationship was not significant (p = 0.09, figure 3(c)). Impedance measurements on individual electrodes, including electrode 19, were often highly variable from day to day (figure 3(b)), making the comparison of individual electrodes to group median values uninformative. These variable impedances may have been due to the connector and headstage used to measure impedances which were different than the connector and cable used to provide stimulation.

3.3. Detection Threshold Stability

Detection thresholds were measured in four different time ranges: near day 100, 500, 1000, and 1500. Due to limits on the participant’s time in the lab for each test session, these measurements were typically taken across multiple test sessions. Nearly all of the implanted electrodes (n=64) were tested within each time range with 54 electrodes tested around day 100, 61 electrodes around day 500, 58 electrodes around day 1000, and 53 electrodes around day 1500. Some electrodes were excluded due to high voltages during the interphase period at the beginning of the test session.

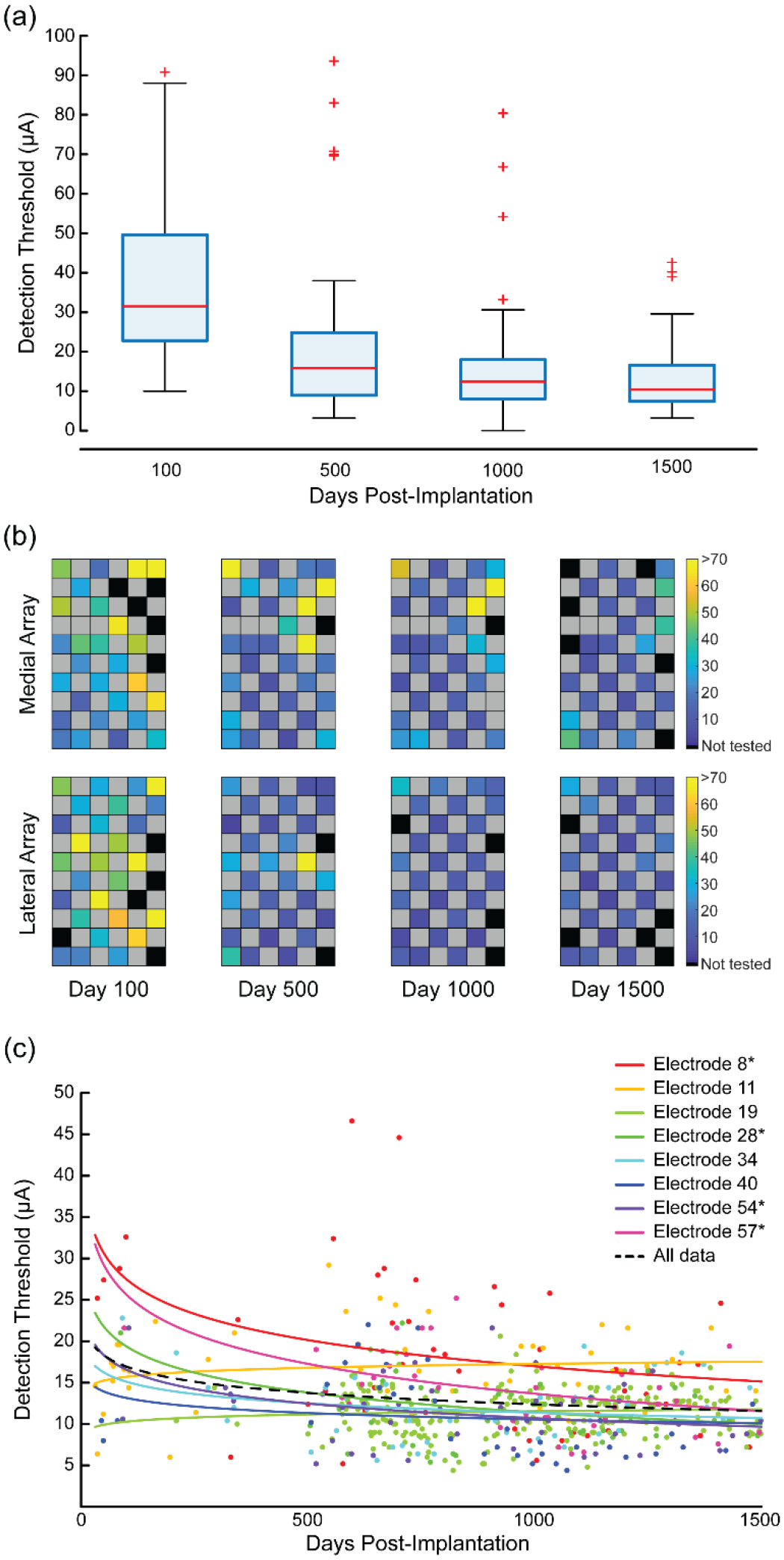

Over the course of the study, the median detection thresholds decreased by about two-thirds, from 31.5 μA at day 100 (IQR: 22.8–49.6 μA), to 15.8 μA at day 500 (IQR: 9.0–24.9 μA), 12.4 μA at day 1000 (IQR: 8.1–18.0 μA), and 10.4 μA at day 1500 (IQR: 7.4–16.6 μA) (figure 4(a)). The detection thresholds around day 100 were significantly higher than the other time periods (P < 0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test) but other sessions were not significantly different from each other (P > 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis Test with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test). We also assessed whether the detection thresholds were spatially organized on the arrays (figure 4(b)) and found that for all test ranges except day 100, there was significant clustering (P < 0.05, Moran’s I with z-test). This indicates that for most of the implant duration, the detection thresholds were not randomly distributed across the array and that electrodes with similar thresholds tended to be near each other.

Figure 4.

Detection thresholds for stimulated electrodes since implantation. (a) Box plots of the median detection threshold values from four different time points. (b) Detection thresholds for each electrode are shown on the stimulation arrays as a heat map. Black spaces represent electrodes that were not tested. Grey spaces represent electrodes that were not wired due to technical constraints. The color bars show the detection threshold values in microamperes. (c) Detection thresholds for eight electrodes over time. Each point represents an individual threshold for a single electrode and the color represents a specific electrode as indicated in the legend. Asterisks on the legend identify electrodes with statistically significant changes over time. Lines were fit to the data for each electrode using regression of the log-transformed data. The fits were reverse transformed for plotting. The dotted black line shows the regression for the aggregate detection data.

Finally, we measured the detection thresholds on a subset of electrodes more frequently throughout the study. These electrodes spanned the two somatosensory arrays but were otherwise chosen arbitrarily. Changes over time were quantified with regression of the individual electrode detection thresholds using a log-transformed time axis. Of the eight tested electrodes, the detection threshold on four electrodes decreased significantly over time (P < 0.05, figure 4(c), indicated with *) while no electrode had significant increases. The analysis of the group data in figure 4(a) showed that after day 500 there was no further decreases in detection thresholds. To examine whether this was true on the eight electrodes where we had considerably more measurements, we performed linear regression for data collected after day 500. We found that on five electrodes there was a significant change in detection thresholds after day 500 (P < 0.05). Four of these were significant decreases in thresholds and one was a significant increase. However, these changes were all small, with slopes of −5.4, −4.2, −3.2, −2.2, and 2.0 μA/year.

4. Discussion

Microstimulation in the somatosensory cortex of a person using SIROF-coated Utah microelectrode arrays can evoke detectable sensations for 1500 days. We found that SIROF-sensory electrodes maintained a higher SNR than platinum-motor electrodes throughout the length of the implant, although the SNR on SIROF-sensory electrodes declined at a slightly faster rate. In fact, SIROF-sensory electrodes were far more likely to retain the capacity to record high-amplitude signals after 1500 days than platinum-motor electrodes. Indeed, 50% of SIROF-sensory electrodes recorded high-amplitude signals within the first 100 days and 25% recorded high-amplitude signals in the last 100 days, representing a 50% loss. However, on platinum-motor electrodes, 70% recorded high-amplitude neurons within the first 100 days, but just 20% recorded high-amplitude neurons in the last 100 days, representing a 70% loss. The impedances of SIROF-sensory electrodes were lower overall and decreased by a smaller amount over time compared to platinum-motor electrodes. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, stimulation detection thresholds continually decreased for 1500 days, indicating an improvement in the ability to elicit sensations with ICMS.

4.1. Stimulation safety limits

The safety limits on the stimulus parameters used in this study, such as pulse amplitude and frequency were based on a series of studies in non-human primates investigating the effects of stimulation on safety at the electrode tissue interface [19,20]. However, these pulse parameters have not always been shown to be safe [17,18,24,26,31–35]. Of particular note, a study of chronic microstimulation in the cat cortex by McCreery et al. showed that continuous stimulation at just 4 nC/phase (equivalent to a stimulation amplitude of 20 μA with the 200 μs pulse width we used in this study), led to a loss of neurons around the electrode tips [26]. While we regularly exceeded this stimulation amplitude and used stimulation amplitudes up to 100 μA, we limited the duty cycle to a maximum of 15 seconds of stimulation at 100 Hz, at which point stimulation would be disabled for an equivalent amount of time. Limiting the duty cycle can help reduce neuronal loss [3,9–11,13,14], however the effect of duty cycle is not well understood. The limited duty cycle may have contributed to lack of measurable deleterious effects on electrodes or evoked sensations.

4.2. Recording signal quality

It is well known that signal quality deteriorates on recording electrodes over long periods of time [26,36,37]. In our study across 1500 days, we saw a 37% decrease in the peak-to-peak voltage on SIROF-sensory electrodes, while the peak-to-peak voltage on platinum-motor electrodes decreased by 46%. For comparison, Chestek et al. 2011 reported a 28.2% and 47% decrease in single-unit amplitude in two implanted non-human primates within the first two months after implant while Barrese et al. 2013 showed an average decrease in the signal amplitude of about 12% across 27 implanted non-human primates over 1000 days on viable electrodes. However, about half of electrodes were excluded from analysis because they were considered not viable, meaning the peak-to-peak voltage fell below 40 μV. Our results are broadly consistent with these and other studies showing that signal quality decreases over time. Our findings of greater decrease in signal quality on platinum-motor electrodes provide evidence that, at a minimum, ICMS did not additionally contribute to decreases in recording quality over time. Additionally, we found that on SIROF-sensory electrodes, more injected charge did not correlate with significant changes in peak-to-peak voltage or the number of high amplitude waveforms recorded, indicating further that stimulation does not additionally contribute to decreases in recording quality.

Previous work has posited that stimulation can rejuvenate the electrode-tissue interface, resulting in increased SNR through an improvement in signal amplitude and decreased impedances [38]. This rejuvenation effect could be related to the preservation of high amplitude recordings on stimulated electrodes that we observed. However, our results showed a steeper decline in SNR over time on stimulated SIROF-sensory electrodes compared to non-stimulated platinum-motor electrodes even though the SNR itself was higher on stimulated SIROF-sensory electrodes than non-stimulated platinum-motor electrodes. Furthermore, we saw that the impedance on stimulated SIROF-sensory electrodes declined at a slower rate than the impedances on non-stimulated platinum-motor electrodes. Impedances however were difficult to compare between SIROF-sensory and platinum-motor electrodes since these electrodes contained different materials with different impedance properties, and stimulated electrodes maintained lower impedance values throughout. We did find on SIROF-sensory electrodes that electrodes with more charge injected had lower median impedances, but this effect was not significant.

The previous work suggesting a rejuvenation effect was focused on the short-term effects of stimulation on signal properties, with a maximum tested duration of eight days. Changes in the signal and impedance over this time scale may not reflect expected changes over many years. Additionally, we looked at recordings at the beginning of sessions to remove the impact of transient changes caused by stimulation on recording quality and impedances. Another substantial difference between the previous work and this current study is the stimulus protocol. In the previous work, stimulation was held constant at 1.5 V for four seconds, and this pulse was only delivered once prior to all signal and impedance measurements. Here, our stimulus parameters consisted of more typical stimulation protocols, including charge-balanced biphasic pulses with an initial cathodic phase lasting 200 μs. Stimulus trains were delivered at a maximum of 300 Hz for up to 15 seconds at a maximum amplitude of 100 μA over many years. The substantial differences in our stimulus protocols makes it difficult to assess similarities or differences in the results. Lastly, there are differences in the cellular composition of motor and somatosensory cortex, most notably the presence of large Betz cells in motor cortex which can produce larger signal [9,31–33]. Differences in recordings could then be affected by cortical differences regardless of stimulation. Overall, these data suggest that stimulation may have improved neural recordings over time, but additional studies will be required to confirm this observation and disentangle the potential effects of electrode material and cortical area.

4.3. Impedances

Electrode impedances have been shown to increase immediately after implantation but the decrease over long periods of time [23]. Here, the impedances of the platinum-motor electrodes decreased more than SIROF-sensory electrodes. One possible explanation relates to the different material properties of the electrodes. SIROF electrodes have considerably lower impedances than platinum electrodes as a result of their larger surface area, due in large part to the sputtering deposition process [25]. As a result, the impedances on the SIROF-sensory electrodes were much lower than the platinum electrodes shortly after implantation and therefore did not have as much range to decrease. Additionally, we found that more charge injection was correlated with lower impedances on SIROF-sensory electrodes, but this effect was not significant. If this is a real effect or not requires further investigation across more electrodes and participants. Increased charge injection could result in decreases in impedances in a few different ways. If stimulation was driving material changes in the metal tips or insulation, this could result in increased surface roughness or electrode leakage pathways, which could both result in decreases in impedances [39,40]. Additionally, stimulation results in transient decreases in impedance which typically recover by the next test session [37,41]. We measured impedances at the beginning of test sessions to account for this effect, but it is possible that delivered stimulation could affect the recorded impedances in the next session. Increasing impedances, potentially as a result of electrode damage resulting from stimulation itself, would result in higher voltages at the electrode-tissue interface which could damage tissue [19,31–33,35,42], or exceed the compliance voltage limits of the stimulator itself. However, SIROF-sensory electrodes in our study maintained a lower impedance than platinum-motor electrodes, most likely due to differences in material, and more charge injection did not increase impedances.

4.4. Detection thresholds

Perhaps the most supportive demonstration of the long-term utility of microstimulation in somatosensory cortex was the observation that that sensory percepts could be consistently evoked over the length of implantation, with detection thresholds decreasing over time. Non-human primate studies have demonstrated that sensations can be evoked over periods of months without behavioral deficits using stimulation parameters higher than those used in this experiment [43]. This is, however, the first time that a human participant has been studied with this protocol and it is promising for bidirectional BCIs that percepts can be reliably evoked and that detection thresholds themselves decrease over long periods of time. Improvements in detection thresholds could have occurred for a variety of reasons. Stimulation over many years could have induced neural plasticity resulting in stronger sensitivity to stimulation [44,45]. Additionally, the participant’s familiarity with the stimulus detection task could have resulted in increased behavioural sensitivity. We also demonstrated that the detection thresholds were spatially clustered on the electrode arrays. There are several possible explanations for this effect. First, if the arrays were not perfectly perpendicular to the cortical surface, or if the cortical surface was curved under the electrode, individual electrode tips on different parts of the array could be at different depths in the cortex, a factor which is known to have an effect on detection thresholds [46]. Additionally, localized tissue reactions could potentially affect the microenvironment around individual electrodes and adjacent electrodes or different locations in somatosensory cortex could be differentially responsive to stimulation. Further work is needed to explore the mechanisms of increased stimulus sensitivity as well as spatial clustering of thresholds.

4.5. Study limitations

Although these results are supportive of the long-term utility of microstimulation in the somatosensory cortex as a component of bidirectional BCIs, we have only tested this in one participant. Future implantations will need to be similarly evaluated to determine if signal quality and detection thresholds are stable over long periods of time. Another possible limitation is that the stimulation delivered as part of this experiment may be much less than what would be provided in a deployable BCI system. However, as stated previously, we have not seen any notable differences between electrodes based on the amount of stimulation they have received. Another factor in this study is that the stimulation electrodes in somatosensory cortex were coated in SIROF, while the recording electrodes in motor cortex were coated with platinum. If there are differences in how these materials are affected in the body over time regardless of stimulation, comparisons between the two could be difficult to make. To minimize this effect, future experiments could examine the recording quality on both stimulated and non-stimulated electrodes with iridium oxide coated tips. Lastly, we only tested four electrode arrays. Variability in the production and insertion of these arrays could potentially lead to differences in recording and stimulating abilities. More arrays across more implanted participants will need to be assessed in the future.

4.6. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that SIROF electrodes used for intracortical microstimulation in somatosensory cortex can maintain recording quality as well as, if not better than, non-stimulated platinum electrodes in motor cortex and can elicit sensory percepts over 1500 days. While this time frame may still be a relatively short in the context of a life-long implantation, demonstrating stability at these time points is a necessary step to support the continued development of these systems. These findings are promising for the field of neural prostheses and sensory restoration specifically and indicate that implanted microelectrodes to restore somatosensory feedback is plausible in clinical application.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Nathan Copeland for his extraordinary commitment and effort in relation to this study and insightful discussions with the study team; Debbie Harrington (Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation) for regulatory management of the study; Angelica Herrera for her help with data acquisition. This research was developed with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s (DARPA, Arlington) Revolutionizing Prosthetics program (Contract Number N66001-10-C-4056), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UH3NS107714 and U01NS108922 and the Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, Grant Numbers B6789C, B7143R, and RX720.

References

- [1].Carmena JM, Lebedev MA, Crist RE, O’Doherty JE, Santucci DM, Dimitrov DF, Patil PG, Henriquez CS and Nicolelis MAL 2003. Learning to control a brain-machine interface for reaching and grasping by primates ed Idan Segev PLoS Biology 1 e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Collinger JL, Wodlinger B, Downey JE, Wang W, Tyler-Kabara EC, Weber DJ, McMorland AJC, Velliste M, Boninger ML and Schwartz AB 2013. High-performance neuroprosthetic control by an individual with tetraplegia The Lancet 381 557–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hochberg LR, Serruya MD, Friehs GM, Mukand JA, Saleh M, Caplan AH, Branner A, Chen D, Penn RD and Donoghue JP 2006. Neuronal ensemble control of prosthetic devices by a human with tetraplegia. Nature 442 164–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Santhanam G, Ryu SI, Yu BM, Afshar A and Shenoy KV. 2006. A high-performance brain–computer interface Nature 442 195–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Velliste M, Perel S, Spalding MC, Whitford AS and Schwartz AB 2008. Cortical control of a prosthetic arm for self-feeding. Nature 453 1098–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Flesher SN, Collinger JL, Foldes ST, Weiss JM, Downey JE, Tyler-Kabara EC, Bensmaia SJ, Schwartz AB, Boninger ML and Gaunt RA 2016. Intracortical microstimulation of human somatosensory cortex Science Translational Medicine 8 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Armenta Salas M, Bashford L, Kellis S, Jafari M, Jo H, Kramer D, Shanfield K, Pejsa K, Lee B, Liu CY and Andersen RA 2018. Proprioceptive and cutaneous sensations in humans elicited by intracortical microstimulation eLife e32904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fifer MS, McMullen DP, Thomas TM, Osborn LE, Nickl R, Candrea D, Pohlmeyer E, Thompson M, Anaya M, Schellekens W, Ramsey N, Bensmia S, Anderson W, Wester B, Crone N, Celnik P, Cantarero G and Tenore F v 2020. Intracortical microstimulation of human fingertip sensations medRxiv [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barrese JC, Rao N, Paroo K, Triebwasser C, Vargas-Irwin C, Franquemont L and Donoghue JP 2013. Failure mode analysis of silicon-based intracortical microelectrode arrays in non-human primates Journal of Neural Engineering 10 066014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chestek CA, Gilja V, Kaufman MT, Rivera-Alvidrez Z, Ryu SI, Nuyujukian P, Fan JM, Foster JD, Shenoy KV, Churchland MM and Cunningham JP 2011. Long-term stability of neural prosthetic control signals from silicon cortical arrays in rhesus macaque motor cortex Journal of Neural Engineering 8 045005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Suner S, Fellows M, Vargas-Irwin C, Nakata GK and Donoghue JP 2005. Reliability of Signals From a Chronically Implanted, Silicon-Based Electrode Array in Non-Human Primate Primary Motor Cortex IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 13 524–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Simeral JD, Kim SP, Black MJ, Donoghue JP and Hochberg LR 2011. Neural control of cursor trajectory and click by a human with tetraplegia 1000 days after implant of an intracortical microelectrode array Journal of Neural Engineering vol 8 p 025027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Downey JE, Schwed N, Chase SM, Schwartz AB and Collinger JL 2018. Intracortical recording stability in human brain-computer interface users Journal of Neural Engineering 15 046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bullard AJ, Hutchison BC, Lee J, Chestek CA and Patil PG 2019. Estimating Risk for Future Intracranial, Fully Implanted, Modular Neuroprosthetic Systems: A Systematic Review of Hardware Complications in Clinical Deep Brain Stimulation and Experimental Human Intracortical Arrays Neuromodulation ner.13069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Weber DJ, Friesen R and Miller LE 2012. Interfacing the somatosensory system to restore touch and Proprioception: Essential considerations Journal of Motor Behavior [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Agnew WF, Yuen TGH, McCreery DB and Bullara LA 1986. Histopathologic evaluation of prolonged intracortical electrical stimulation Experimental Neurology 92 162–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rousche PJ and Normann RA 1999. Chronic intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) of cat sensory cortex using the utah intracortical electrode array IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McCreery DB, Agnew WF, Yuen TGH and Bullara L 1990. Charge density and charge per phase as cofactors in neural injury induced by electrical stimulation IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 37 996–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kim S, Callier T, Tabot G a, Gaunt RA, Tenore F v and Bensmaia SJ 2015. Behavioral assessment of sensitivity to intracortical microstimulation of primate somatosensory cortex Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 15202–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen KH, Dammann JF, Boback JL, Tenore FV, Otto KJ, Gaunt RA and Bensmaia SJ 2014. The effect of chronic intracortical microstimulation on the electrode–tissue interface Journal of Neural Engineering 11 026004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Callier T, Schluter EW, Tabot GA, Miller LE, Tenore F v. and Bensmaia SJ 2015. Long-term stability of sensitivity to intracortical microstimulation of somatosensory cortex Journal of Neural Engineering [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davis TS, Parker RA, House PA, Bagley E, Wendelken S, Normann RA and Greger B 2012. Spatial and temporal characteristics of V1 microstimulation during chronic implantation of a microelectrode array in a behaving macaque Journal of Neural Engineering vol 9 p 065003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Negi S, Bhandari R, Rieth L and Solzbacher F 2010. In vitro comparison of sputtered iridium oxide and platinum-coated neural implantable microelectrode arrays Biomedical Materials 5 015007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Negi S, Bhandari R, Rieth L, van Wagenen R and Solzbacher F 2010. Neural electrode degradation from continuous electrical stimulation: Comparison of sputtered and activated iridium oxide Journal of Neuroscience Methods 186 8–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cogan SF 2008. Neural Stimulation and Recording Electrodes Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 10 275–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McCreery D, Pikov V and Troyk PR 2010. Neuronal loss due to prolonged controlled-current stimulation with chronically implanted microelectrodes in the cat cerebral cortex. Journal of Neural Engineering 7 036005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Weiss JM, Flesher SN, Franklin R, Gaunt RA and Collinger JL 2018. Artifact-free recordings in human bidirectional brain–computer interfaces Journal of Neural Engineering 16 016002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wood F, Black MJ, Vargas-Irwin C, Fellows M and Donoghue JP 2004. On the variability of manual spike sorting IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 51 912–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Leek MR 2001. Adaptive procedures in psychophysical research Perception and Psychophysics 63 1279–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Moran PAP. Notes on Continuous Stochastic Phenomena. Biometrika. 1950;37:17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kane SR, Cogan SF, Ehrlich J, Plante TD, McCreery DB and Troyk PR 2013. Electrical Performance of Penetrating Microelectrodes Chronically Implanted in Cat Cortex IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 60 2153–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Parker RA, Davis TS, House PA, Normann RA and Greger B 2011. The functional consequences of chronic, physiologically effective intracortical microstimulation Progress in Brain Research 194 145–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Torab K, Davis TS, Warren DJ, House PA, Normann RA and Greger B 2011. Multiple factors may influence the performance of a visual prosthesis based on intracortical microstimulation: Nonhuman primate behavioural experimentation Journal of Neural Engineering 8 035001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Negi S, Bhandari R, van Wagenen R and Solzbacher F 2010. Factors affecting degradation of sputtered iridium oxide used for neuroprosthetic applications Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) pp 568–71 [Google Scholar]

- [35].McCreery DB, Bullara LA and Agnew WF 1986. Neuronal activity evoked by chronically implanted intracortical microelectrodes Experimental Neurology 92 147–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Johnson MD, Otto KJ and Kipke DR 2005. Repeated voltage biasing improves unit recordings by reducing resistive tissue impedances IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 13 160–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Otto KJ, Johnson MD and Kipke DR 2006. Voltage pulses change neural interface properties and improve unit recordings with chronically implanted microelectrodes IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 53 333–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rivara CB, Sherwood CC, Bouras C and Hof PR 2003. Stereologic characterization and spatial distribution patterns of Betz cells in the human primary motor cortex Anatomical Record - Part A Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology 270 137–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Prasad A, Xue QS, Dieme R, Sankar V, Mayrand RC, Nishida T, Streit WJ and Sanchez JC 2014. Abiotic-biotic characterization of Pt/Ir microelectrode arrays in chronic implants Frontiers in Neuroengineering 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Vomero M, Castagnola E, Ciarpella F, Maggiolini E, Goshi N, Zucchini E, Carli S, Fadiga L, Kassegne S and Ricci D 2017. Highly Stable Glassy Carbon Interfaces for Long-Term Neural Stimulation and Low-Noise Recording of Brain Activity Scientific Reports 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Newbold C, Richardson R, Millard R, Seligman P, Cowan R and Shepherd R 2011. Electrical stimulation causes rapid changes in electrode impedance of cell-covered electrodes Journal of neural engineering 8 036029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Romo R, Hernández A, Zainos A and Salinas E 1998. Somatosensory discrimination based on cortical microstimulation Nature 392 387–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jackson A, Mavoori J and Fetz EE 2006. Long-term motor cortex plasticity induced by an electronic neural implant Nature 444 56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].DeYoe EA, Lewine JD and Doty RW 2005. Laminar variation in threshold for detection of electrical excitation of striate cortex by macaques Journal of Neurophysiology 94 3443–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tehovnik EJ and Slocum WM 2009. Depth-dependent detection of microampere currents delivered to monkey V1 European Journal of Neuroscience 29 1477–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Grand L, Wittner L, Herwik S, Göthelid E, Ruther P, Oscarsson S, Neves H, Dombovári B, Csercsa R, Karmos G and Ulbert I 2010. Short and long term biocompatibility of NeuroProbes silicon probes Journal of Neuroscience Methods 189 216–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]