Abstract

Ependymomas encompass a heterogeneous group of central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms that occur along the entire neuroaxis. In recent years, extensive (epi-)genomic profiling efforts have identified several molecular groups of ependymoma that are characterized by distinct molecular alterations and/or patterns. Based on unsupervised visualization of a large cohort of genome-wide DNA methylation data, we identified a highly distinct group of pediatric-type tumors (n = 40) forming a cluster separate from all established CNS tumor types, of which a high proportion were histopathologically diagnosed as ependymoma. RNA sequencing revealed recurrent fusions involving the pleomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1) gene in 19 of 20 of the samples analyzed, with the most common fusion being EWSR1:PLAGL1 (n = 13). Five tumors showed a PLAGL1:FOXO1 fusion and one a PLAGL1:EP300 fusion. High transcript levels of PLAGL1 were noted in these tumors, with concurrent overexpression of the imprinted genes H19 and IGF2, which are regulated by PLAGL1. Histopathological review of cases with sufficient material (n = 16) demonstrated a broad morphological spectrum of tumors with predominant ependymoma-like features. Immunohistochemically, tumors were GFAP positive and OLIG2- and SOX10 negative. In 3/16 of the cases, a dot-like positivity for EMA was detected. All tumors in our series were located in the supratentorial compartment. Median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 6.2 years. Median progression-free survival was 35 months (for 11 patients with data available). In summary, our findings suggest the existence of a novel group of supratentorial neuroepithelial tumors that are characterized by recurrent PLAGL1 fusions and enriched for pediatric patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00401-021-02356-6.

Keywords: Neuroepithelial tumor, Supratentorial, PLAGL1, EWSR1, FOXO1, EP300, Gene fusion

Introduction

Ependymomas encompass a heterogeneous group of central nervous system (CNS) neoplasms that occur along the entire neuroaxis and can affect both children and adults [18]. DNA methylation and gene expression profiling efforts in recent years have identified several molecular groups of ependymoma across different anatomic sites of the CNS with distinct clinicopathological characteristics and molecular alterations or patterns [6, 7, 23–26, 40–42]. Within the supratentorial compartment, two molecularly defined types of ependymoma are characterized by recurrent gene fusions, one involving the gene ZFTA (formerly referred to as C11orf95, most frequently fused to RELA), and the other involving YAP1 [3, 12, 24, 26, 43]. More recently, several reports have expanded on the spectrum of gene fusions observed in supratentorial ependymoma and ependymoma-like tumors, in particular in the pediatric setting [22, 35, 43]. Implementing these molecular markers into the WHO classification for brain tumors is of paramount importance in overcoming the challenge of histologically diverse tumor types and in increasing diagnostic accuracy. Still, many cases do not fit into the as of yet established CNS tumor types, leaving clinicians and patients with unclear or even incorrect diagnoses in further decision making.

Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling has emerged as a powerful tool for both robust classification of known CNS tumor entities and identification of novel and clinically relevant subclasses of brain tumors with characteristic alterations [5, 24]. Here, we describe a molecularly distinct subset of supratentorial neoplasms (n = 40) with predominant ependymal appearance identified by investigation of a large cohort of DNA methylation data. These tumors harbor recurrent fusions involving the pleomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1) gene.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Tumor samples and retrospective clinical data from 40 patients were obtained from multiple national and international collaborating centers and collected at the Department of Neuropathology of the University Hospital Heidelberg (Germany). Sample selection was based on unsupervised visualization of genome-wide DNA methylation data that revealed a molecularly distinct group of tumors (n = 40) forming a cluster separate from all established entities. Due to the aspect of a multicenter cohort (23 different centers) including DNA methylation data that have been uploaded via the web platform https://www.molecularneuropathology.org, availability of tissue and/or clinical data was restricted for some of the cases. A proportion of data was generated in the context of the Molecular Neuropathology 2.0 study. Analysis of tissue and clinical data was performed in accordance with local ethics regulations. Clinical details of the patients are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (online resource).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

For all cases with sufficient material (n = 16), histological review of an H&E-stained slide was performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 classification of tumors of the CNS [17]. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on a Ventana BenchMark ULTRA Immunostainer using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). Antibodies were directed against: glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP; Z0334, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000 dilution, Dako Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; clone GP1.4, mouse monoclonal, dilution 1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA), Sry-related HMG-BOX gene 10 (SOX10; clone EP268, rabbit monoclonal, dilution 1:100, Cell Marque Corp., Rocklin, CA, USA) and oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2 (OLIG2; clone EPR2673, rabbit monoclonal, dilution 1:50, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

DNA methylation array processing and copy-number profiling

Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling of all samples was performed using the Infinium MethylationEPIC (EPIC) BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) or Infinium HumanMethylation450 (450 k) BeadChip array (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described [5]. Raw data were generated at the Department of Neuropathology of the University Hospital Heidelberg, the Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) or at respective international collaborator institutes, using both fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples. All computational analyses were performed in R version 3.6.0 (R Development Core Team, 2016; https://www.R-project.org). Copy-number variation analysis from 450 k and EPIC methylation array data was performed using the conumee Bioconductor package version 1.12.0 [4]. Raw signal intensities were obtained from IDAT-files using the minfi Bioconductor package version 1.21.4. Illumina EPIC and 450 k samples were merged to a combined data set by selecting the intersection of probes present on both arrays (combineArrays function, minfi). Each sample was individually normalized by performing a background correction (shifting of the 5% percentile of negative control probe intensities to 0) and a dye-bias correction (scaling of the mean of normalization control probe intensities to 10,000) for both color channels. Subsequently, a correction for the array type (450 k/EPIC) was performed by fitting univariable, linear models to the log2-transformed intensity values (removeBatchEffect function, limma package version 3.30.11). The methylated and unmethylated signals were corrected individually. Beta-values were calculated from the retransformed intensities using an offset of 100 (as recommended by Illumina). All samples were checked for duplicates by pairwise correlation of the genotyping probes on the 450 k/EPIC array. To perform unsupervised non-linear dimension reduction, the remaining probes after standard filtering [5] were used to calculate the 1-variance weighted Pearson correlation between samples. The resulting distance matrix was used as input for t-SNE analysis (t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding; Rtsne package version 0.13). The following non-default parameters were applied: is_distance = T, theta = 0, pca = F, max_iter = 10,000 perplexity = 20. DNA methylation sites of the PLAGL1 imprinted region (received via http://www.humanimprints.net/#data) were visualized in a heatmap using the R-package ‘pheatmap’. Control tissue DNA methylation samples (n = 119) as previously described [5] were used for comparison.

RNA sequencing and analysis

RNA was extracted from FFPE tissue samples using the automated Maxwell system with the Maxwell 16 LEV RNA FFPE Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcriptome analysis using messenger RNA (mRNA) sequencing of samples for which RNA of sufficient quality and quantity was available was performed on a NextSeq 500 instrument (Illumina) as previously described [31]. This was possible for 20 tumors within the novel group and 14 ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas. In addition, a reference cohort of other glioma and glioneuronal subtypes were used for differential gene expression analysis (YAP1:MAMLD1-fused ependymoma (n = 3), central neurocytoma (n = 9), extraventricular neurocytoma (n = 8), dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (n = 11), papillary glioneuronal tumor (n = 9), KIAA1549:BRAF-fused pilocytic astrocytoma (n = 14), diffuse midline glioma H3 K27M mutant (n = 14) and glioblastoma IDH wild-type (n = 9)). Fastq files from transcriptome sequencing were used for de novo annotation of fusion transcripts using the deFuse [20] and Arriba (v1.2.0) [36] algorithms with standard parameters. All further analysis was performed in R (version 3.6.0; R Core Team, 2019) using the DESeq2 package (v1.28.1) [19]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed after variance stabilizing transformation of the count data and normalization with respect to library size, based on the selection of the top 1,000 most variable genes with relative log expression normalization. Similarities between samples were determined by computing Manhattan distances on the variance stabilized data followed by unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Differential expression testing was performed on raw count data after fitting a negative binomial model. P-values were adjusted for multiplicity by applying the Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Targeted next-generation DNA sequencing and mutational analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from FFPE tumor tissue samples of 18 patients within the cohort using the automated Maxwell system with the Maxwell 16 FFPE Plus LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Capture-based next-generation DNA sequencing was performed on a NextSeq 500 instrument (Illumina) as previously described [29] using a custom brain tumor panel (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) covering the entire coding and selected intronic and promoter regions of 130 genes of particular relevance in CNS tumors (Supplementary Table 2, online resource).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data on survival could be retrospectively retrieved for eleven patients. Distribution of time to progression or recurrence (TTP) after surgery was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. Patients lost to follow-up are censored at date of last contact in analysis of TTP.

Results

DNA methylation profiling reveals a molecular distinct group of neuroepithelial tumors

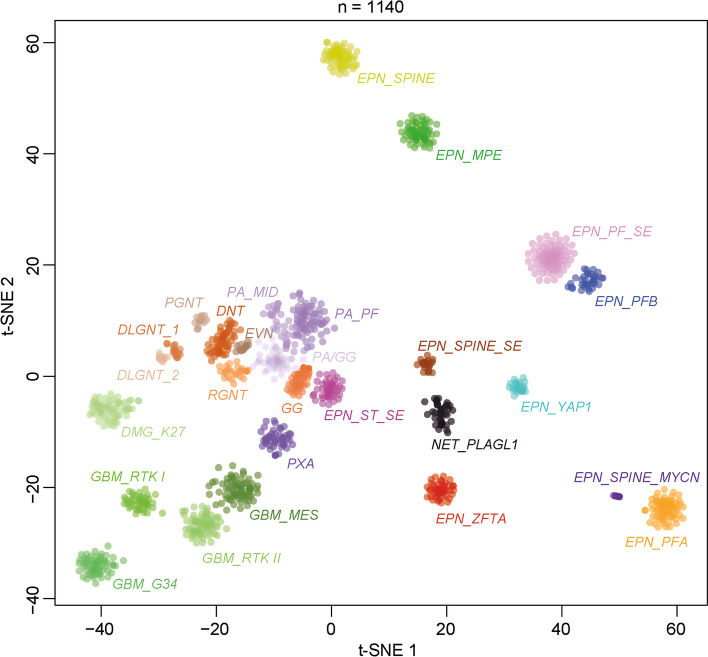

DNA methylation profiling has emerged as a powerful approach for robust classification of CNS neoplasms [5]. Using a screening approach based on unsupervised visualization of a large cohort of genome-wide DNA methylation data, we identified a highly distinct group of tumors (n = 40) forming a cluster separate from all established entities of which a high proportion of tumors (19/32, 59%) were histopathologically diagnosed as ependymoma. A more focused t-SNE analysis of DNA methylation patterns of these samples alongside 1100 other well-characterized glial and glioneuronal neoplasms (reference samples included in the current version of the Heidelberg DNA methylation classifier with a calibrated score > 0.9) confirmed the distinct nature of this novel group (Fig. 1). Analysis of copy-number variations (CNVs) derived from DNA methylation array data revealed a relatively balanced profile in most of the cases, with structural aberrations on chromosome 22q (21/40, 52.5%) and 6q (19/40, 47.5%) most frequently observed (Supplementary Fig. 1a, online resource). A chromothripsis-like pattern affecting chromosomes 6 and 13 was seen in one of the samples (Supplementary Fig. 1b, online resource). In one case, a homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/B was detected. An integrated plot of CNVs identified in all samples is given in Supplementary Fig. 1c (online resource).

Fig. 1.

DNA methylation profiling reveals a molecular distinct group of neuroepithelial tumors. t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis of DNA methylation profiles of the 40 tumors investigated (NET_PLAGL1) alongside 1100 selected reference samples. Reference DNA methylation classes: ependymoma posterior fossa group A (EPN_PFA), ependymoma posterior fossa group B (EPN_PFB), ependymoma spinal (EPN_SPINE), ependymoma with ZFTA fusion (EPN_ZFTA), ependymoma with YAP1 fusion (EPN_YAP1), myxopapillary ependymoma (EPN_MPE), spinal ependymoma (EPN_SPINE), posterior fossa subependymoma (EPN_PF_SE), spinal subependymoma (EPN_SPINE_SE), supratentorial subependymoma (EPN_ST_SE) and spinal ependymoma with MYCN amplification (EPN_SPINE_MYC), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA), posterior fossa pilocytic astrocytoma (PA_PF), midline pilocytic astrocytoma (PA_MID), pilocytic astrocytoma and ganglioglioma (PA/GG), ganglioglioma (GG), rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor (RGNT), dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNT), extraventricular neurocytoma (EVN), papillary glioneuronal tumor (PGNT), diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor subclass 1 and 2 (DLGNT_1/2), glioblastoma IDH wild-type subclass mesenchymal (GBM_MES), glioblastoma IDH wild-type subclass RTK I (GBM_RTK I), glioblastoma IDH wild-type subclass RTK II (GBM_RTK II), glioblastoma IDH wild-type H3.3 G34 mutant (GBM_G34) and diffuse midline glioma H3 K27M mutant (DMG_K27). Additional clustering analyses indicated that the PLAGL1 cohort can potentially be further subdivided into two clusters (not shown)

Recurrent rearrangements involving PLAGL1 are characteristic for the novel group of neuroepithelial tumors

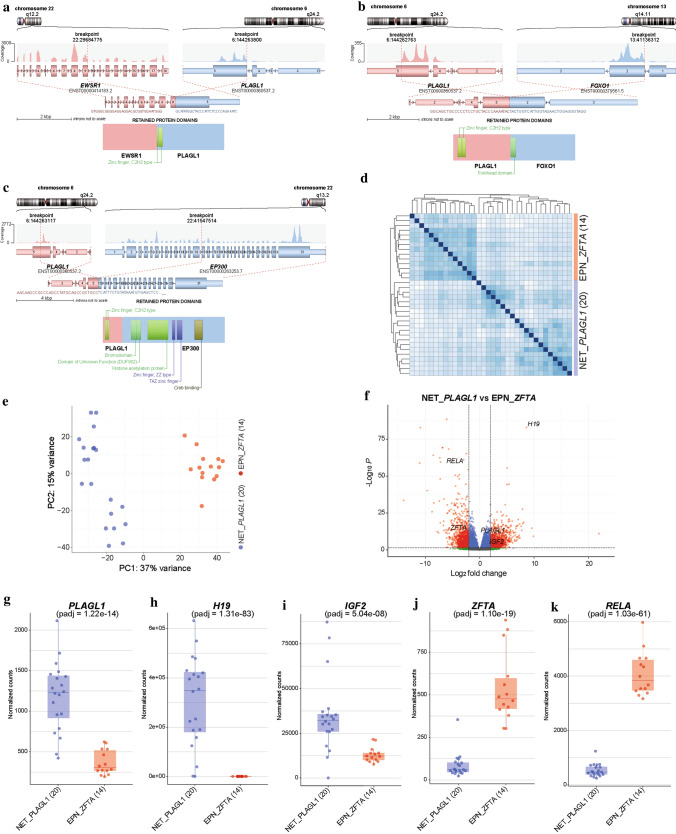

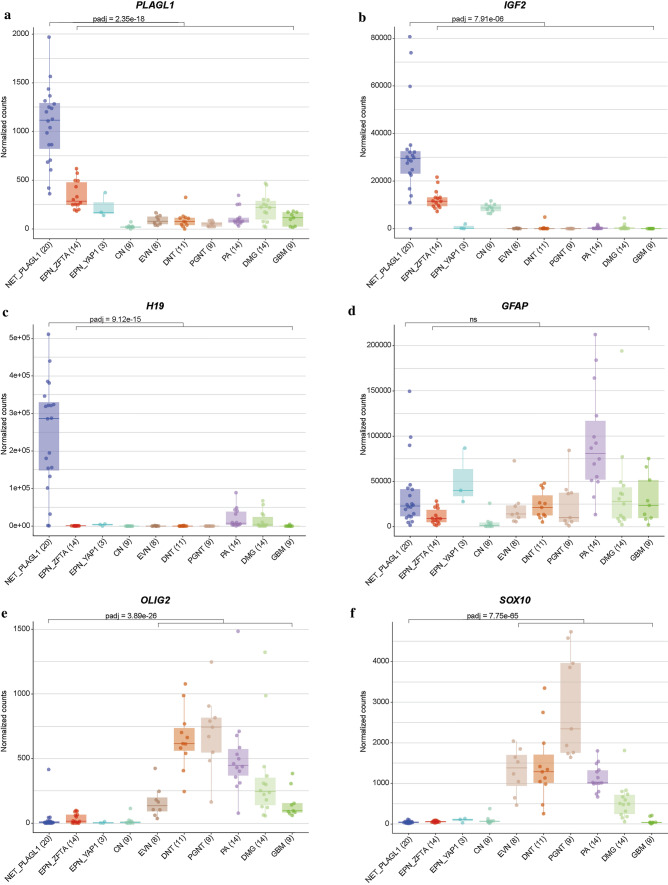

Since a high proportion of supratentorial ependymomas are driven by gene fusions involving ZFTA (C11orf95, most frequently fused to RELA) or YAP1, we performed mRNA sequencing of all samples with sufficient material (n = 20). In 19/20 of the cases, a gene fusion involving PLAGL1 was detected, conserving the zinc finger structure (C2H2 type) as part of the fusion product, with either EWSR1 as 5’ partner or FOXO1 or EP300 as a 3’ partner (Fig. 2a–c). In the most common EWSR1:PLAGL1 fusions (n = 13), exons 1–9 or 1–8 of EWSR1 (NM_013986), which is located on chromosome 22q12.2, were fused to exon 5 of PLAGL1 (NM_001289039), which is found on chromosome 6q24.2. Five out of 20 cases with exons 1–5 of PLAGL1 fused to FOXO1 upstream of exons 2–3 (NM_0017612) were also observed. In one case, exons 1–5 of PLAGL1 are fused to exons 15–31 of EP300 (NM_001429). In all rearrangements, the DNA binding domain (zinc finger structure) of PLAGL1 was retained and fused to the respective transactivation domain (TAD) of the partner gene (Fig. 2a–c). We next performed an exploratory differential gene expression analysis of tumor samples (n = 20) within the novel group in comparison to ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas (n = 14). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering demonstrated a clear segregation of tumor samples in comparison to ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymoma (Fig. 2d). These results were recapitulated by PCA of normalized transcript counts (Fig. 2e). Quantification of mRNA expression revealed that the PLAGL1 gene itself was more highly expressed in tumors within the novel group than in ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymoma (adjusted p = 1.22e − 14; Fig. 2f, g). Additionally, upregulated genes of potential interest included H19 and IGF2 (adjusted p = 1.31e − 83, adjusted p = 5.04e − 08; Fig. 2h, i), both regulated by PLAGL1 and with known functions in the tumorigenesis of different cancers [38]. RELA and ZFTA transcript levels were upregulated in ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas (adjusted p = 1.03e − 61 and adjusted p = 1.10e − 19, respectively; Fig. 2j, k). Differential gene expression analysis between tumors within the novel group and a reference cohort of other glial and glioneuronal subtypes confirmed high transcript levels of PLAGL1 (adjusted p = 2.35e − 18), H19 (adjusted p = 9.12e − 15), IGF2 (adjusted p = 7.91e − 06) and DLK1 (adjusted p = 1.12e − 10) in the PLAGL1-fused cohort (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Fig. 2, online resource). Expression of particular markers differentially expressed in astrocytic and in ependymal neoplasms [10, 14, 21] revealed low OLIG2 and SOX10 expression (adjusted p = 3.89e − 26 and adjusted p = 7.75e − 65) within the novel group, with similar expression of GFAP (Fig. 3d–f and Supplementary Fig. 2, online resource). Moreover, the nearby imprinting control region (ICR) of PLAGL1 showed evidence for loss of imprinting in the corresponding DNA methylation profiles (Supplementary Fig. 3, online resource). Analysis of the mutational landscape of 19/40 tumors in the novel group using targeted next-generation sequencing revealed TERT promoter mutations (C228T) in two of the cases (Supplementary Table 1, online resource), with no other relevant events involving putative brain tumor genes.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the PLAGL1 fusion genes and transcriptional profiling of tumors samples in the novel group (NET_PLAGL1). Visualization of the PLAGL1 fusion genes detected by RNA sequencing for three selected samples. EWSR1:PLAGL1 fusion in case #1, in which exons 1–9 of EWSR1, as the 5’ partner, are fused to exon 5 of PLAGL1 (a), PLAGL1:FOXO1 fusion in case #18, in which exons 1–5 of PLAGL1 are fused to exons 2–3 of FOXO1 as the 3’ partner (b), and PLAGL1:EP300 fusion in case #19, in which exons 1–5 of PLAGL1 are fused to exons 15–31 of EP300 as the 3’ partner (c), conserving the zinc finger structure (C2H2 type) as part of the fusion products. Differences in gene expression profiles between samples in the novel group and ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas. Normalized transcript counts from samples in the novel group and ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas clustered by Pearson’s correlation coefficient (d) and principal component analysis (e). Volcano plot depicting genes differentially expressed between samples in the novel group versus ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymomas (f). PLAGL1 (g), H19 (h), IGF2 (i), ZFTA (j), and RELA (k) expression in the novel group (n = 20) compared to ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymoma samples (n = 14)

Fig. 3.

Transcriptional profiling of PLAGL1-altered neuroepithelial tumor. Differential gene expression analysis between samples in the novel group (NET_PLAGL1) and a reference cohort of different glial/glioneuronal tumors (ZFTA:RELA-fused ependymoma (EPN_ZFTA), YAP1:MAMLD1-fused ependymoma (EPN_YAP1), central neurocytoma (CN), extraventricular neurocytoma (EVN), dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor (DNT), papillary glioneuronal tumor (PGNT), KIAA1549:BRAF-fused pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), diffuse midline glioma H3 K27M mutant (DMG) and glioblastoma IDH wild-type (GBM). PLAGL1, IGF2 and H19 are more highly expressed in NET_PLAGL1 cases when compared with representative glial/glioneuronal tumors (a–c). GFAP levels are similar compared to different glial/glioneuronal tumors (d). Expression of markers differentially expressed in astrocytic and in ependymal tumors revealed low OLIG2 and SOX10 expression in NET_PLAGL1 compared to astrocytic/glioneuronal tumors (e, f)

Clinical characteristics and morphological features demonstrate pediatric-type tumors with ependymoma-like appearance

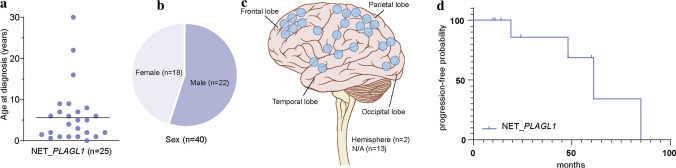

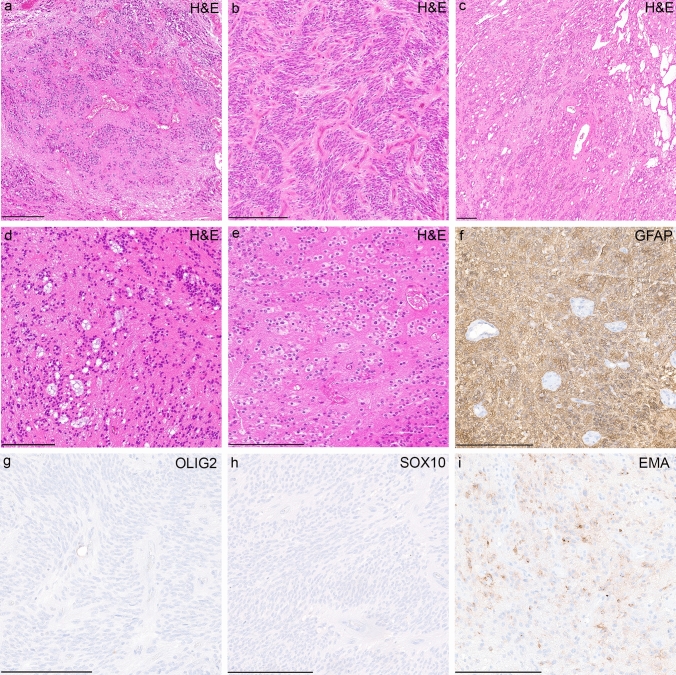

Analysis of available clinical data demonstrated that median age of the patients at the time of diagnosis was 6.2 years (n = 25; range 0–30; with 92% of the tumors occurring in patients < 17 years of age, Fig. 4a) and the sex distribution was relatively balanced (F/M = 1:1.2, Fig. 4b). All tumors in our series were located supratentorially (Fig. 4c). The proportion of PLAGL1-fused tumors from all supratentorial tumors cannot yet be accurately determined. However, within the pediatric Molecular Neuropathology 2.0 study, PLAGL1-fused tumors account for approximately 0.7% of all supratentorial neoplasms included in the study. Outcome data were available for 11 patients. Median progression-free survival was 35 months (range 10–85 months; Fig. 4d). The initial histopathological diagnoses of the tumors within the cohort were relatively wide, although a high proportion of cases were designated as ependymoma (19/32, 59%). Other recurrent diagnoses included ‘embryonal tumor’ and different low- and high-grade gliomas (Supplementary Table 1, online resource). More detailed descriptions of the cases are given in Supplementary Table 1. A histopathological review of samples with available material (n = 16) confirmed a relatively wide morphological spectrum of tumors with ependymoma-like features (Fig. 5a–i). Histologically, all reviewed tumors shared a moderate to high increase in cellular density in a mostly fine neurofibrillary matrix with prominent microcystic changes (Fig. 5a–d). The tumor cells typically had monomorphic, round to oval nuclei with finely dispersed chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Single cases presented more pleomorphic cells. In many cases, perivascular pseudorosettes were observed, at least focally. Two of the cases showed focal oligodendroglial morphology with perinuclear halos due to cytoplasmatic clearing (Fig. 5e). Extensive calcification was seen in a small number of tumors (n = 3). Necrosis was not observed. Mitotic activity was generally low, with exception of two cases. Immunoreactivity for GFAP was present in all cases (Fig. 5f). The tumor cells neither expressed OLIG2 nor SOX10 (Fig. 5g, h). In 3/16 of the cases, a dot-like positivity for EMA was detected (Fig. 5i).

Fig. 4.

Clinical features of the investigated cohort. Age at diagnosis with the median age of 6.2 years (a), patient sex distribution (b) and distribution of tumor location (c). Time to progression or recurrence (TTP) of the 11 patients from the investigated cohort (NET_PLAGL1) for whom follow-up data were available (d)

Fig. 5.

Morphological and immunohistochemical features of tumors within the cohort. Histologically, tumors shared a moderate to high increase in cellular density with mostly monomorphic, round to oval nuclei and often prominent microcystic changes (a–d). Perivascular pseudorosettes were observed in several of the cases, although very subtle in some the samples (a–d). Occasionally, tumor cells showed oligodendroglial morphology with perinuclear halos due to cytoplasmatic clearing (e). Immunohistochemically, tumors were GFAP positive (f) and OLIG2- and SOX10 negative (g, h). In 3/16 of the cases, a dot-like positivity for EMA was detected (i). Scale bars denote 200 μm

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence for the pathobiological heterogeneity of neuroepithelial tumors beyond the established spectrum by reporting the existence of an epigenetically distinct group of rare pediatric-type supratentorial neoplasms with often ependymoma-like appearance that shows recurrent gene fusions involving the PLAGL1 gene.

Our findings suggest rearrangements involving PLAGL1, particularly EWSR1:PLAGL1 and PLAGL1:FOXO1 fusions, as a molecular hallmark of this novel group of tumors. Gene fusions of PLAGL1 with EWSR1 have been reported exceptionally rarely in neoplasms of the CNS, including single cases of a SMARCB1-deficient atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) [27] and a glioneuronal tumor, not elsewhere classified (NEC) [16]. However, in a very recent report, a PLAGL1:EWSR1 fusion was described in a supratentorial ependymoma of a six-year-old child [44]. While EWSR1 has long been known to be involved in gene fusions in Ewing sarcoma and several other tumor entities [34], the role of PLAGL1 in tumorigenesis is not yet fully understood. The PLAGL1 gene encodes a C2H2 zinc finger protein that acts as a transcription factor as well as a cofactor of other regulatory proteins, and is expressed in diverse types of human tissues amongst others in neural stem/progenitor cells and developing neuroepithelial cells [37, 39]. Although its specific role in tumorigenesis is controversial and its functions appear to depend on the cellular context, altered expression of PLAGL1 has been linked to various types of cancer [1, 8, 32]. More recent studies provide evidence for its oncogenic function in brain tumors with overexpression of PLAGL1 being involved in tumorigenesis of glioblastoma [9, 13] and interaction of PLAGL family transcription factors in ZFTA:RELA-fused supratentorial ependymoma [3].

In the EWSR1:PLAGL1 fusions described here, the whole N-terminal transcriptional activation domain (TAD) of EWSR1 is fused in-frame to the zinc finger domain (with DNA binding activity) of PLAGL1, very similar to other oncogenic EWSR1 fusions, in particular rearrangements between EWSR1 and PATZ1 [28, 30]. This indicates aberrant recruitment of the TAD of EWSR1 to the DNA binding domain of PLAGL1 with subsequent downstream effects, as described for other EWSR1 rearrangements, as the likely oncogenic function of this fusion [11]. This also fits to the increased expression of PLAGL1 in these samples. In addition, five cases harbored a fusion between PLAGL1 and the transcriptional factor FOXO1, which is a known partner in other rearrangements [2, 15]. In the PLAGL1:FOXO1 fusion observed here, the DNA binding domain of PLAGL1 is juxtaposed to the C-terminal TAD of FOXO1, which seems quite similar to PAX3:FOXO1 rearrangements as frequently observed in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma [15]. In a single case, PLAGL1 was fused to EP300, a fusion partner known from ‘CNS tumors with BCOR alteration’ [33]. Additionally, upregulated genes included H19, IGF2 and DLK1, all regulated by PLAGL1 and with known functions in tumorigenesis of different cancers [38]. This might indicate a potential downstream effect of the fusion. However, the precise oncogenic mechanism of the EWSR1:PLAGL1, PLAGL1:FOXO1 and PLAGL1:EP300 chimeric proteins remain to be elucidated. Further studies will be needed to reveal the exact role of the fusions in these tumors.

Another important finding was the relatively wide morphological spectrum of tumors within this group. Although most tumors were originally diagnosed as ependymoma, a significant proportion of cases were designated to other entities, including different low- and high-grade tumors. Consistent with that, a histopathological review of cases with sufficient material revealed a morphologically heterogeneous group of tumors often with ependymoma-like features. A putative ependymal differentiation was further supported by differential gene expression analysis between tumors within the novel group and a reference cohort of other glial and glioneuronal tumors, that revealed low expression levels of OLIG2 and SOX10, both suggested to distinguish astrocytic from ependymal tumors [10, 14, 21]. However, the absence of a unifying morphological pattern in this group of tumors underlines the relevance of molecular profiling for precise diagnosis of these CNS neoplasms. This group has not been identified as a distinct subset in previous large-scale studies due to the relatively small case numbers, broad morphology and lack of routine RNA profiling in previous cohorts, again highlighting the importance of RNA sequencing in standard brain tumor diagnostics. According to the structure of specifying ‘essential diagnostic criteria’ of the upcoming 5th edition of the WHO classification of CNS tumors, we suggest (a) the specific signature by DNA methylation profiling or (b) the combination GFAP expression and PLAGL1 fusions as essential diagnostic criteria for these tumors.

A limitation of our study is the relatively low extent of clinical data due to diverse origins and the retrospective nature of the series, in particular patient outcome data, which allows only a rough estimation of the malignancy of the tumors within this novel group. Considering the high number of cases without sequencing data, it seems also possible that other alterations apart from the described fusions could be present, particularly in those tumors which do not show indication for a PLAGL1 fusion in the copy-number profile. Follow-up analyses are needed to characterize this new group of CNS neoplasms in more detail.

In summary, we provide evidence for a novel group of supratentorial brain tumors and identify PLAGL1 as a putative relevant driver in this entity. Since there is no absolutely clear indication of a particular lineage at the moment, we suggest the term ‘supratentorial neuroepithelial tumor with PLAGL1 fusion’ to describe this novel group of tumors. However, we hope to further specify the name once additional studies provide a clearer picture of the cellular origin. These findings have immediate implications for brain tumor profiling in order to avoid incorrect diagnoses due to lack of alignment with established tumor types. PLAGL1 fusion-positive neuroepithelial tumors should thus be included into upcoming classifications of brain tumors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

For excellent technical support, we sincerely thank the Microarray Unit of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility, as well as I. Leis and M. Schalles (Department of Neuropathology, Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany). We also thank the German Childhood Cancer Foundation for funding (“Molecular Neuropathology 2.0-Increasing diagnostic accuracy in paediatric neurooncology” (DKS 2015.01)). This study was supported by the Hertie Network of Excellence in Clinical Neuroscience. P. Sievers is a fellow of the Hertie Academy of Excellence in Clinical Neuroscience. S. C. Henneken and D. R. Ghasemi received scholarships of the Mildred-Scheel doctoral program of the German Cancer Aid and the German Academic Scholarship Foundation. This study was generously supported by ‘Ein Kiwi gegen Krebs’. S. Brandner was partly funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre. A subset of the human tissue was obtained from University College London NHS Foundation Trust as part of the UK Brain Archive Information Network (BRAIN UK, Ref: 19/001) which is funded by the Medical Research Council and Brain Tumour Research UK. U. Schüller was supported by the Fördergemeinschaft Kinderkrebszentrum Hamburg.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Philipp Sievers, Sophie C. Henneken, Kristian W. Pajtler and Felix Sahm shared authorship.

Contributor Information

Kristian W. Pajtler, Email: k.pajtler@kitz-heidelberg.de

Felix Sahm, Email: felix.sahm@med.uni-heidelberg.de.

References

- 1.Abdollahi A. LOT1 (ZAC1/PLAGL1) and its family members: mechanisms and functions. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:16–25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonescu CR, Huang SC, Sung YS, Zhang L, Helmke BM, Kirchner M, et al. Novel GATA6-FOXO1 fusions in a subset of epithelioid hemangioma. Mod Pathol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00723-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arabzade A, Zhao Y, Varadharajan S, Chen HC, Jessa S, Rivas B, et al. ZFTA-RELA dictates oncogenic transcriptional programs to drive aggressive supratentorial ependymoma. Cancer Discov. 2021 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V, Schrimpf D, Sturm D, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature. 2018;555:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nature26000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavalli FMG, Hubner JM, Sharma T, Luu B, Sill M, Zapotocky M, et al. Heterogeneity within the PF-EPN-B ependymoma subgroup. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1888-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghasemi DR, Sill M, Okonechnikov K, Korshunov A, Yip S, Schutz PW, et al. MYCN amplification drives an aggressive form of spinal ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138:1075–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godlewski J, Krazinski BE, Kowalczyk AE, Kiewisz J, Kiezun J, Kwiatkowski P, et al. PLAGL1 (ZAC1/LOT1) expression in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: correlations with disease progression and unfavorable prognosis. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:617–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hide T, Takezaki T, Nakatani Y, Nakamura H, Kuratsu J, Kondo T. Sox11 prevents tumorigenesis of glioma-initiating cells by inducing neuronal differentiation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7953–7959. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Donson AM, Richmond AM, Pekmezci M, Tihan T, Foreman NK. SOX10 distinguishes pilocytic and pilomyxoid astrocytomas from ependymomas but shows no differences in expression level in ependymomas from infants versus older children or among molecular subgroups. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75:295–298. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krystel-Whittemore M, Taylor MS, Rivera M, Lennerz JK, Le LP, Dias-Santagata D, et al. Novel and established EWSR1 gene fusions and associations identified by next-generation sequencing and fluorescence in-situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 2019;93:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2019.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupp R, Ruff L, Terranova S, Nathan E, Ballereau S, Stark R, et al. ZFTA-translocations constitute ependymoma chromatin remodeling and transcription factors. Cancer Discov. 2021 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C, Cho HJ, Yamashita D, Abdelrashid M, Chen Q, Bastola S, et al. Tumor edge-to-core transition promotes malignancy in primary-to-recurrent glioblastoma progression in a PLAGL1/CD109-mediated mechanism. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2:vdaa163. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdaa163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ligon KL, Alberta JA, Kho AT, Weiss J, Kwaan MR, Nutt CL, et al. The oligodendroglial lineage marker OLIG2 is universally expressed in diffuse gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:499–509. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linardic CM. PAX3-FOXO1 fusion gene in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2008;270:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopez-Nunez O, Cafferata B, Santi M, Ranganathan S, Pearce TM, Kulich SM, et al. The spectrum of rare central nervous system (CNS) tumors with EWSR1-non-ETS fusions: experience from three pediatric institutions with review of the literature. Brain Pathol. 2021;31:70–83. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD. WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPherson A, Hormozdiari F, Zayed A, Giuliany R, Ha G, Sun MG, et al. deFuse: an algorithm for gene fusion discovery in tumor RNA-Seq data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1001138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otero JJ, Rowitch D, Vandenberg S. OLIG2 is differentially expressed in pediatric astrocytic and in ependymal neoplasms. J Neurooncol. 2011;104:423–438. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0509-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pages M, Pajtler KW, Puget S, Castel D, Boddaert N, Tauziede-Espariat A, et al. Diagnostics of pediatric supratentorial RELA ependymomas: integration of information from histopathology, genetics, DNA methylation and imaging. Brain Pathol. 2019;29:325–335. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pajtler KW, Wen J, Sill M, Lin T, Orisme W, Tang B, et al. Molecular heterogeneity and CXorf67 alterations in posterior fossa group A (PFA) ependymomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:211–226. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1877-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, et al. Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:728–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panwalkar P, Clark J, Ramaswamy V, Hawes D, Yang F, Dunham C, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of H3K27me3 demonstrates global reduction in group-A childhood posterior fossa ependymoma and is a powerful predictor of outcome. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:705–714. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, et al. C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature. 2014;506:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramkissoon SH, Bandopadhayay P, Hwang J, Ramkissoon LA, Greenwald NF, Schumacher SE, et al. Clinical targeted exome-based sequencing in combination with genome-wide copy number profiling: precision medicine analysis of 203 pediatric brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:986–996. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi S, Barresi S, Giovannoni I, Alesi V, Ciolfi A, Colafati GS, et al. Expanding the spectrum of EWSR1-PATZ1 rearranged CNS tumors: an infantile case with leptomeningeal dissemination. Brain Pathol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Jones DT, Meyer J, Kratz A, Reuss D, et al. Next-generation sequencing in routine brain tumor diagnostics enables an integrated diagnosis and identifies actionable targets. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:903–910. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siegfried A, Rousseau A, Maurage CA, Pericart S, Nicaise Y, Escudie F, et al. EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion may define a new glioneuronal tumor entity. Brain Pathol. 2019;29:53–62. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stichel D, Schrimpf D, Casalini B, Meyer J, Wefers AK, Sievers P, et al. Routine RNA sequencing of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens in neuropathology diagnostics identifies diagnostically and therapeutically relevant gene fusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138:827–835. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su HC, Wu SC, Yen LC, Chiao LK, Wang JK, Chiu YL, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies the role of Zac1 in cervical cancer metastasis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11837. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68835-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tauziede-Espariat A, Pierron G, Siegfried A, Guillemot D, Uro-Coste E, Nicaise Y, et al. The EP300:BCOR fusion extends the genetic alteration spectrum defining the new tumoral entity of “CNS tumors with BCOR internal tandem duplication”. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8:178. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-01064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thway K, Fisher C. Mesenchymal tumors with EWSR1 gene rearrangements. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12:165–190. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomomasa R, Arai Y, Kawabata-Iwakawa R, Fukuoka K, Nakano Y, Hama N, et al. Ependymoma-like tumor with mesenchymal differentiation harboring C11orf95-NCOA1/2 or -RELA fusion: a hitherto unclassified tumor related to ependymoma. Brain Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/bpa.12943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhrig S, Ellermann J, Walther T, Burkhardt P, Frohlich M, Hutter B, et al. Accurate and efficient detection of gene fusions from RNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2021;31:448–460. doi: 10.1101/gr.257246.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valente T, Junyent F, Auladell C. Zac1 is expressed in progenitor/stem cells of the neuroectoderm and mesoderm during embryogenesis: differential phenotype of the Zac1-expressing cells during development. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:667–679. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varrault A, Gueydan C, Delalbre A, Bellmann A, Houssami S, Aknin C, et al. Zac1 regulates an imprinted gene network critically involved in the control of embryonic growth. Dev Cell. 2006;11:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vega-Benedetti AF, Saucedo C, Zavattari P, Vanni R, Zugaza JL, Parada LA. PLAGL1: an important player in diverse pathological processes. J Appl Genet. 2017;58:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s13353-016-0355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wani K, Armstrong TS, Vera-Bolanos E, Raghunathan A, Ellison D, Gilbertson R, et al. A prognostic gene expression signature in infratentorial ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:727–738. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witt H, Gramatzki D, Hentschel B, Pajtler KW, Felsberg J, Schackert G, et al. DNA methylation-based classification of ependymomas in adulthood: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:1616–1624. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witt H, Mack SC, Ryzhova M, Bender S, Sill M, Isserlin R, et al. Delineation of two clinically and molecularly distinct subgroups of posterior fossa ependymoma. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng T, Ghasemi DR, Okonechnikov K, Korshunov A, Sill M, Maass KK, et al. Cross-species genomics reveals oncogenic dependencies in ZFTA/C11orf95 fusion-positive supratentorial ependymomas. Cancer Discov. 2021 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zschernack V, Junger ST, Mynarek M, Rutkowski S, Garre ML, Ebinger M, et al. Supratentorial ependymoma in childhood: more than just RELA or YAP. Acta Neuropathol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02260-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.