Summary

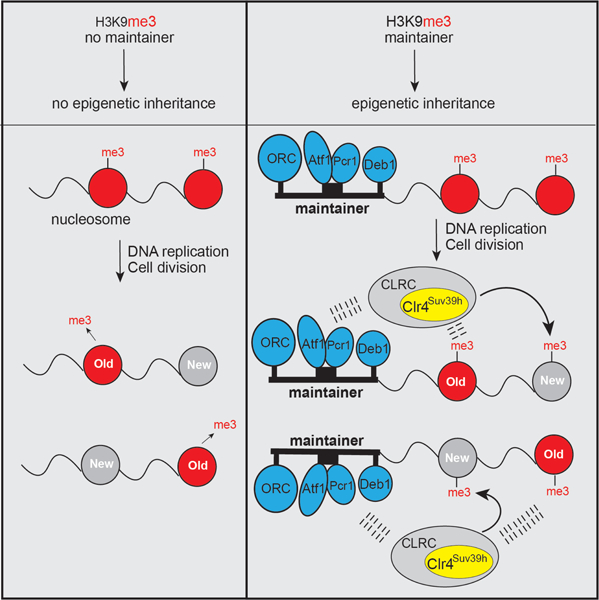

Epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin requires DNA sequence-independent propagation mechanisms, coupling to RNAi, or input from DNA sequence, but how DNA contributes to inheritance is not understood. Here, we identify a DNA element (termed “maintainer”) that is sufficient for epigenetic inheritance of preexisting histone H3 lysine 9 methylation (H3K9me) and heterochromatin in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, but cannot establish de novo gene silencing in wild-type cells. This maintainer is a composite DNA element with binding sites for the Atf1/Pcr1 and Deb1 transcription factors and the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC), located within a 130-base pair region, and can be converted to a silencer in cells with lower rates of H3K9me turnover, suggesting that it participates in recruiting the H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4/Suv39h. These results suggest that, in the absence of RNAi, histone H3K9me is only heritable when it can collaborate with maintainer-associated DNA-binding proteins that help recruit the enzyme responsible for its epigenetic deposition.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Wang et al. reveal the mechanism of DNA sequence-dependent epigenetic inheritance by showing that a 130-bp composite DNA element with binding sites for three site-specific DNA binding factors acts as a maintainer of epigenetic memory. This element works together with preexisting histone H3 lysine 9 methylation to ensure heterochromatin maintenance.

Introduction

Epigenetic inheritance mechanisms play important roles in maintaining gene expression patterns and safeguarding cell identity (Margueron and Reinberg, 2010; Moazed, 2011). Two classes of positive feedback mechanisms, broadly defined as trans- and cis-acting, are thought to mediate epigenetic memory (Moazed, 2011). The first class involves transcription factors that regulate the expression of downstream genes and also activate their own expression, thus allowing an initial response to persist in the absence of inducing signals (Ptashne and Gann, 2001). The second class involves changes in covalent modifications of DNA or histones, which are then propagated in cis following DNA replication by enzymes that recognize (read) certain parental modifications and catalyze (write) the same modification on newly synthesized DNA strands or newly deposited histones (Margueron and Reinberg, 2010; Moazed, 2011; Probst et al., 2009; Radman-Livaja et al., 2011). Trans-acting positive feedback loops rely on specific DNA sequences to which the auto-activating transcription factor binds (Ptashne, 2014; Ptashne and Gann, 2001). By contrast, cis-acting chromatin-based mechanisms are generally presumed to function in a DNA sequence-independent manner through read-write positive feedback. Recent studies have demonstrated that although the read-write mechanism can propagate meta-stable epigenetic states independently of DNA sequence, stable cis epigenetic inheritance requires both the read-write positive feedback loop and specific DNA sequences (Audergon et al., 2015; Coleman and Struhl, 2017; Laprell et al., 2017; Ragunathan et al., 2015; Wang and Moazed, 2017). Despite this profound impact on epigenetic memory of conserved chromatin states in both yeast and Drosophila, the nature of DNA sequences that promote cis- and allele-specific epigenetic inheritance and how such sequences work together with read-write mechanisms is poorly understood.

Heterochromatic domains of DNA have been shown to have epigenetic inheritance properties in eukaryotes ranging from yeast to mammals (Allshire and Madhani, 2018). In S. pombe, heterochromatin is localized at pericentromeric DNA repeats, sub-telomeric regions, and the mating type (mat) locus. These domains are associated with histone H3K9 methylation (H3K9me), which is conserved modification in heterochromatin from fission yeast to mammals. At the mat locus, heterochromatin formation requires the parallel activities of the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery, binding sites for the Atf1/Pcr1 transcription factor heterodimer, and other DNA elements, which recruit the Clr4 (Suv39h) H3K9 methyltransferase and other factors (Greenstein et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2004; Thon et al., 1999; Yamada et al., 2005). At an ectopic euchromatic locus, H3K9me domains established by artificial tethering of Clr4 to can only be epigenetically maintained in cells lacking the Epe1 anti-silencing factor, a member of the Jumonji domain family demethylases, demonstrating that the read-write mechanism could propagate epigenetic information independently of DNA sequence (Audergon et al., 2015; Ragunathan et al., 2015). In contrast, stable cis epigenetic inheritance at the mat locus and pericentromeric DNA repeats occurs in epe1+ cells (Ekwall et al., 1997; Grewal and Klar, 1996), suggesting a role for chromosomal context in stable epigenetic inheritance. Consistent with this expectation, we previously showed that the DNA sequence within the mat locus including two binding sites for the Atf1/Pcr1transcription factors are required for epigenetic inheritance of silencing and H3K9me (Wang and Moazed, 2017). However, it has remained unclear whether binding sites for Atf1/Pcr1, which also bind to and activate the transcription of many stress-induced genes across the S. pombe genome (Sanso et al., 2011a; Sanso et al., 2011b), are sufficient for epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin.

In this study, we used an inducible heterochromatin formation system that allowed us to identify native chromosomal sequences that are necessary and sufficient for epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me heterochromatin. We identify an epigenetic maintainer that is composed of closely juxtaposed binding sites for multiple factors, Atf1/Pcr1 and two additional factors. Outside of the heterochromatic mat locus, at numerous dispersed binding sites across the genome, each maintainer binding factor performs essential regulatory functions unrelated to heterochromatin formation, suggesting that their close juxtaposition at the mat locus gives rise to their ability to act as maintainers. Our findings suggest that site-specific DNA-binding factors acts together with preexisting H3K9me, via multiple weak interactions, to recruit the H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4/Suv39h, ensuring the restoration of heterochromatin following DNA replication and cell division.

Results

Identification of a Maintainer of Epigenetic Information

Previously we showed that the two Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites s1 and s2 are required for epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing and H3K9me at the mat locus when other redundant DNA sequences, including the cenH and mat2 regions, which can establish silencing by RNAi-dependent and -independent mechanisms, respectively, are deleted (Wang and Moazed, 2017). Up to 400 Atf1/Pcr1 binding-sites are present throughout the S. pombe genome (Sanso et al., 2011a; Sanso et al., 2011b). To test whether the Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites at the mat locus were sufficient to mediate epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation, we generated cells with deletion of the entire region between the Inverted Repeat-Left (IR-L) and Inverted Repeat-Right (IR-R) boundary elements, with or without insertion of the s1 and s2 Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites downstream the 9xtetO-ura4+ reporter gene (Figure 1A). As expected, tethering the catalytic domain of Clr4 via fusion to tetracycline repressor (TetR-Clr4-I) established silencing at both reporter loci, indicated by growth on FOA-containing medium in the absence of tetracycline (Figure 1A). Release of TetR-Clr4-I by the addition of tetracycline resulted in loss of silencing even in cells with the insertion of the s1 and s2 binding sites downstream of the reporter, indicating that, the two Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites were not sufficient to maintain silencing at the mat locus.

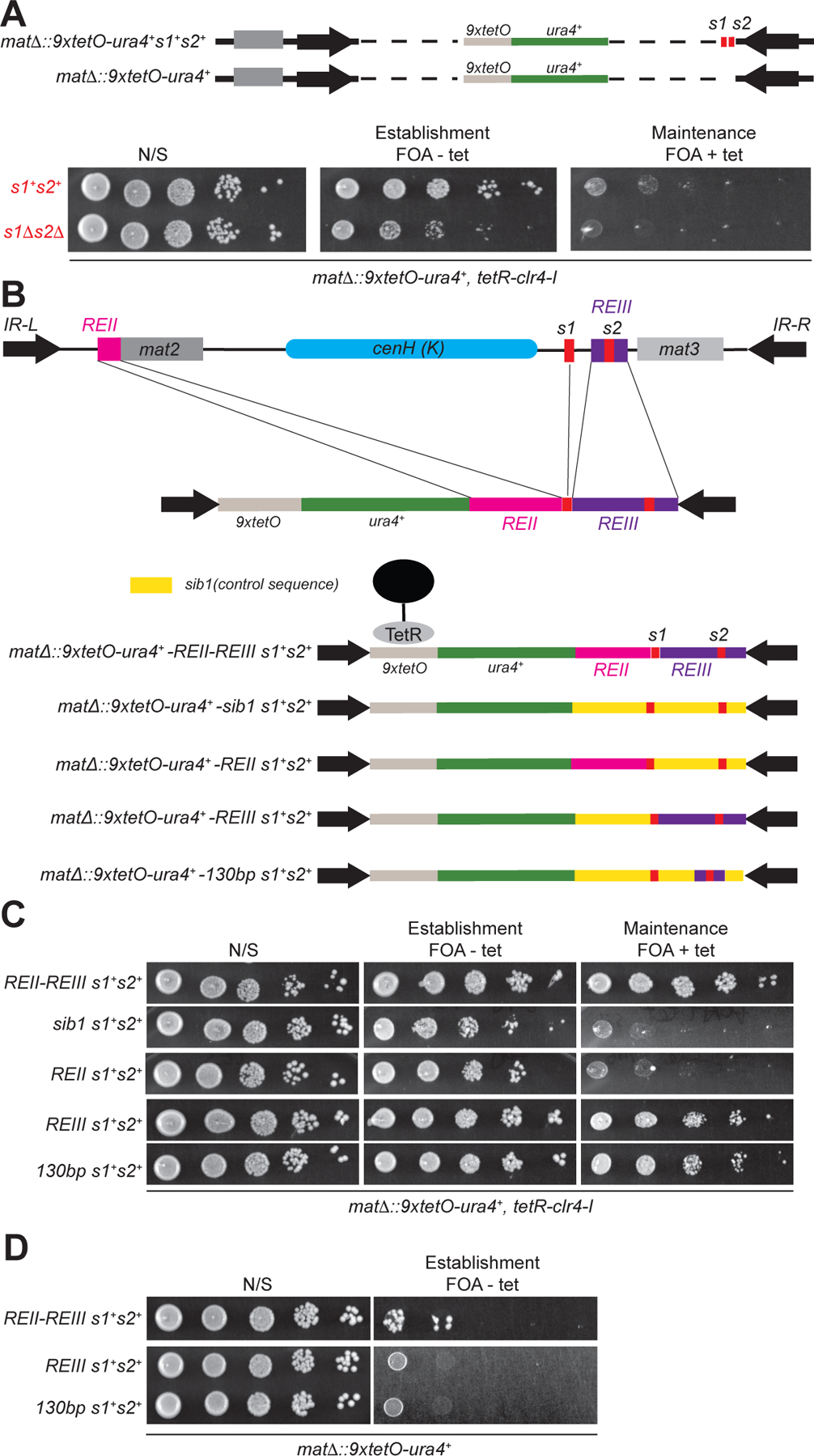

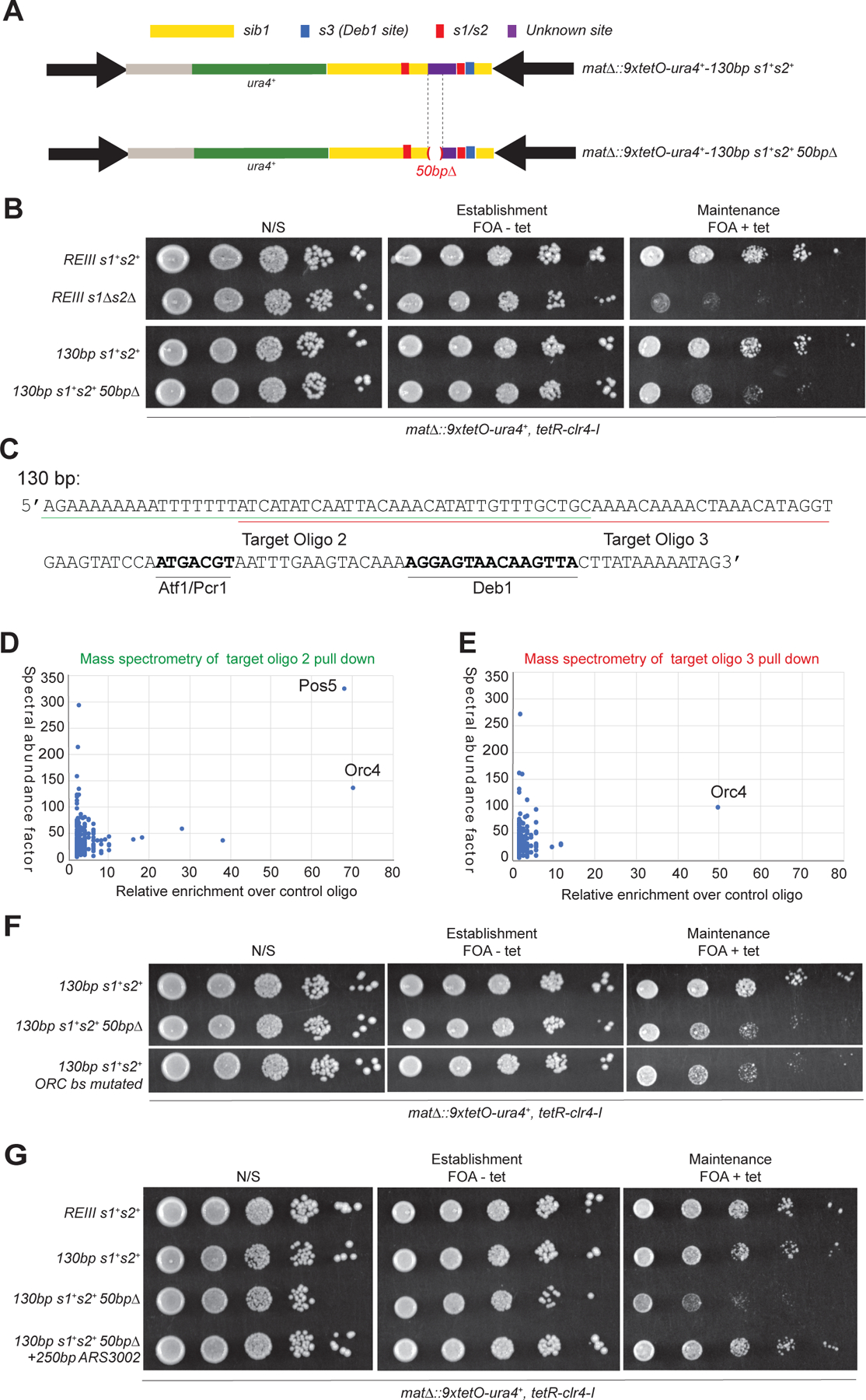

Figure 1. Identification of a minimal maintainer sequence at the mat locus.

(A) Schematic diagram of the silent mating type (mat) locus engineered for testing whether the Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites are sufficient to mediate epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation (top). Growth silencing assays of cells carrying the modified mat loci (bottom). (B, C) Schematic diagram and silencing assay of modified mat loci designed to identify the minimal sequences that are required for epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing. (D) Silencing assays showing that REIII and the 130-bp maintainer sequence lack heterochromatin establishment activity.

Previous studies have shown that two DNA elements, repressor element II (REII, 233 bp) and repressor element III (REIII, 424 bp), located immediately upstream of the mat2 and mat3 genes, respectively, contribute to gene silencing (Ayoub et al., 2000; Hansen et al., 2011; Thon et al., 1999) (Figure 1B). The REIII element contains the s2 Atf1/Pcr1 binding site (Figure 1B). We hypothesized that other sequences within the REII and REIII work together with the Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites to mediate epigenetic inheritance of silencing and H3K9 methylation. To test this hypothesis, we constructed strains with the REII, REIII (including s2), and s1 sequences inserted downstream of the mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+ reporter gene and tested whether these sequences were sufficient for maintenance of silencing (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1C (top row), the combination of REII, REIII, and s1 sequences allowed robust growth of the reporter gene on FOA-containing medium, even after the release of TetR-Clr4-I, indicating that the combined sequences were sufficient for maintenance of silencing when located within the boundary elements at the mat locus. As a control, replacement of the REII and REIII with control DNA of equal length from the ORF of a euchromatin gene, sib1+, did not support maintenance (Figure 1B and 1C, second row). These observations indicate that heritable gene silencing at the mat locus requires DNA sequences beyond the Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites.

To further analyze the minimal DNA sequences required for epigenetic maintenance, we constructed a series of strains with deletions of the REII and REIII elements (Figure 1B, Figure S1). While the combination of REII s1, and s2 did not support maintenance (Figure 1C, third row), the REIII element together with the s1 site was sufficient to maintain silencing (Figure 1C, fourth row). We further narrowed down the maintenance function of REIII to a minimal 130-bp region, which together with the s1 site (7 bp), was sufficient to maintain silencing (Figure 1C, row 5). We next deleted one or both s1 and s2 sites and found that while the s1 site, which is located outside the 130-bp element, was dispensable for maintenance, the s2 site located within the 130-bp element was essential (Figure S1C). To test whether the full REIII element or the 130-bp REIII DNA sequence, together with the s1 site, could also establish heterochromatin at the mat locus, we constructed cells with exactly the same genotype as the above-mentioned strains at the mat locus but lacking TetR-Clr4-I. Growth silencing assays showed that the REII, REIII, and s1 sequences mediated de novo establishment of silencing at the mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+ reporter locus at a low rate (Figure 1D, top row, ~0.05%). In contrast, REIII or the 130-bp minimal sequence plus the s1 site failed to establish silencing at the reporter locus, as indicated by the absence of growth on FOA-containing medium (Figure 1D, second and third rows). Since the REIII/s1, the 137 bp DNA sequence (130 bp plus s1), and the minimal 130-bp DNA sequence were able to mediate maintenance but not establishment of silencing, we termed the minimal sequence a “maintainer” element.

The Mating Type Maintainer Is Composed of Binding Sites for Atf1/Pcr1, Deb1, and ORC

We hypothesized that the 130-bp maintainer recruits other DNA binding protein(s) that work together with Atf1/Pcr1 to maintain silencing. To identify such proteins, we first dissected the 130-bp region by further deletion analysis (Figure 2A, Figure S1). As expected based on pervious results (Wang and Moazed, 2017)(Figure S1C), deletion of the s1 and s2 Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites abolished epigenetic inheritance (Figure 2B). Furthermore, deletion of a 32 bp region adjacent to the s2 site (replaced with 32 bp control sib1 DNA) resulted in loss of epigenetic maintenance (Figure 2B) and led to decreased levels of H3K9me3 at the reporter locus (Figure 2C) after tetracycline-mediated release of TetR-Clr4-I. As a control, H3K9me3 levels at the pericentromeric dg regions were not affected by deletion of the 32 bp element (Figure 2D).

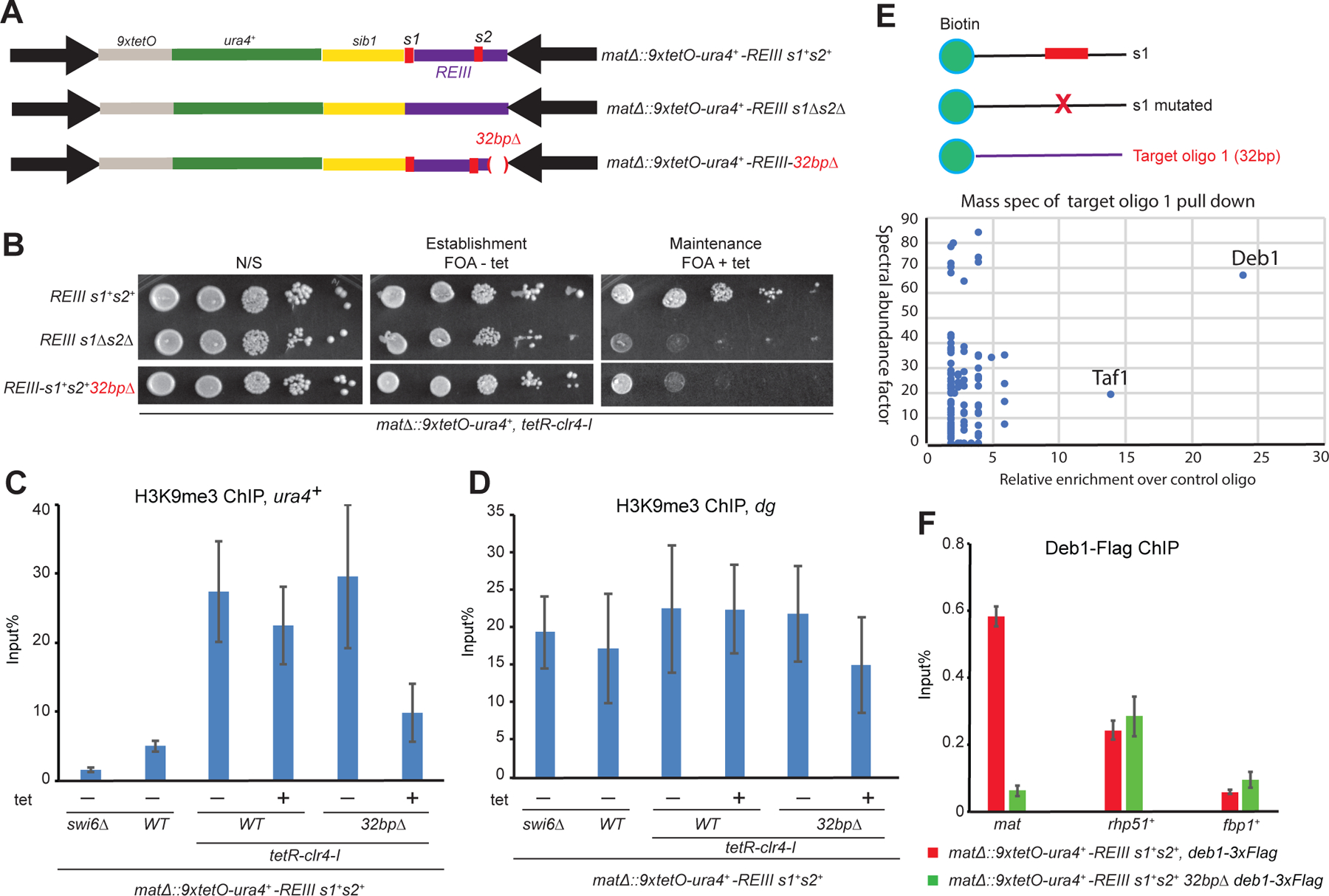

Figure 2. Identification of Deb1 as a maintainer-binding protein.

(A) Schematic diagram of the intact maintenance competent mat locus (mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+-REIII s1+s2+) versus mat loci carrying deletion of the Atf1/Orc1 binding sites (mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+-REIII s1∆s2∆) or deletion of a 32 bp region located downstream of the s2 site (mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+-REIII 32bp∆). (B) Growth silencing assays showing that the 32 bp deletion results in loss of maintenance. The image of silencing assay is cropped from the image shown in Figure S1B, which also contains data for additional deletions. (C, D) ChIP experiments showing that the 32 bp deletion results in decreased level of H3K9me at the ura4+ reporter gene at the mat locus (c) but not pericentromeric heterochromatin (D). n=2 biological replicates. (E) Mass spectrometry identification of proteins enriched in the 32 bp oligonucleotide (oligo 1) pull down normalized to the s1 oligonucleotide pulldown. All enriched proteins (peptide count) are shown. n=1 technical replicates. (F) ChIP experiment showing enrichment of Deb1–3xFlag at the mat locus and control genes and the effect of deleting the 32 bp sequence, required for maintenance of silencing, on the Deb1–3xFlag enrichment. rph51+ and fpb1+ serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. n=2 biological replicates.

To identify the protein(s) that binds to this 32 bp sequence, we used an oligonucleotide pull-down approach in which 5’-biotinylated oligonucleotides bound to streptavidin beads were incubated with cell lysate and the bound proteins were identified by mass spectrometry (Figure 2E). 5’-biotinylated oligonucleotides with the wild type (s1) and mutant (s1 mutated) Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites served as positive and negative controls, respectively (Figure 2E, Figure S2A). As expected, Flag-Atf1 was enriched in biotin-s1, but not biotin-mutant s1, or other control oligonucleotide pull-downs (Figure S2B). Mass spectrometry analysis identified the Deb1 transcription factor as the most highly enriched protein in the biotin-32 bp oligonucleotide (oligo1) pull-down (Figure 2E). Consistent with this association, ChIP experiments showed that Flag-Deb1 was highly enriched at the mat locus and deletion of the 32 bp element abolished this enrichment (Figure 2F). Deb1 is an essential transcription factor and has been previously reported to bind to the promoter region of the rhp51+ gene (Shim et al., 2000) (Figure 3A). Based on similarity to the Deb1 binding sites at the rhp51+ locus, we identified a consensus Deb1 binding site within the 32 bp element (Figure 3A). Mutations within this putative Deb1 binding site abolished its association with the mat locus and its ability to maintain silencing (Figure 3B-E). Together, these results suggest that Deb1 is a second DNA-binding protein that is required for the maintainer function of the 130-bp element.

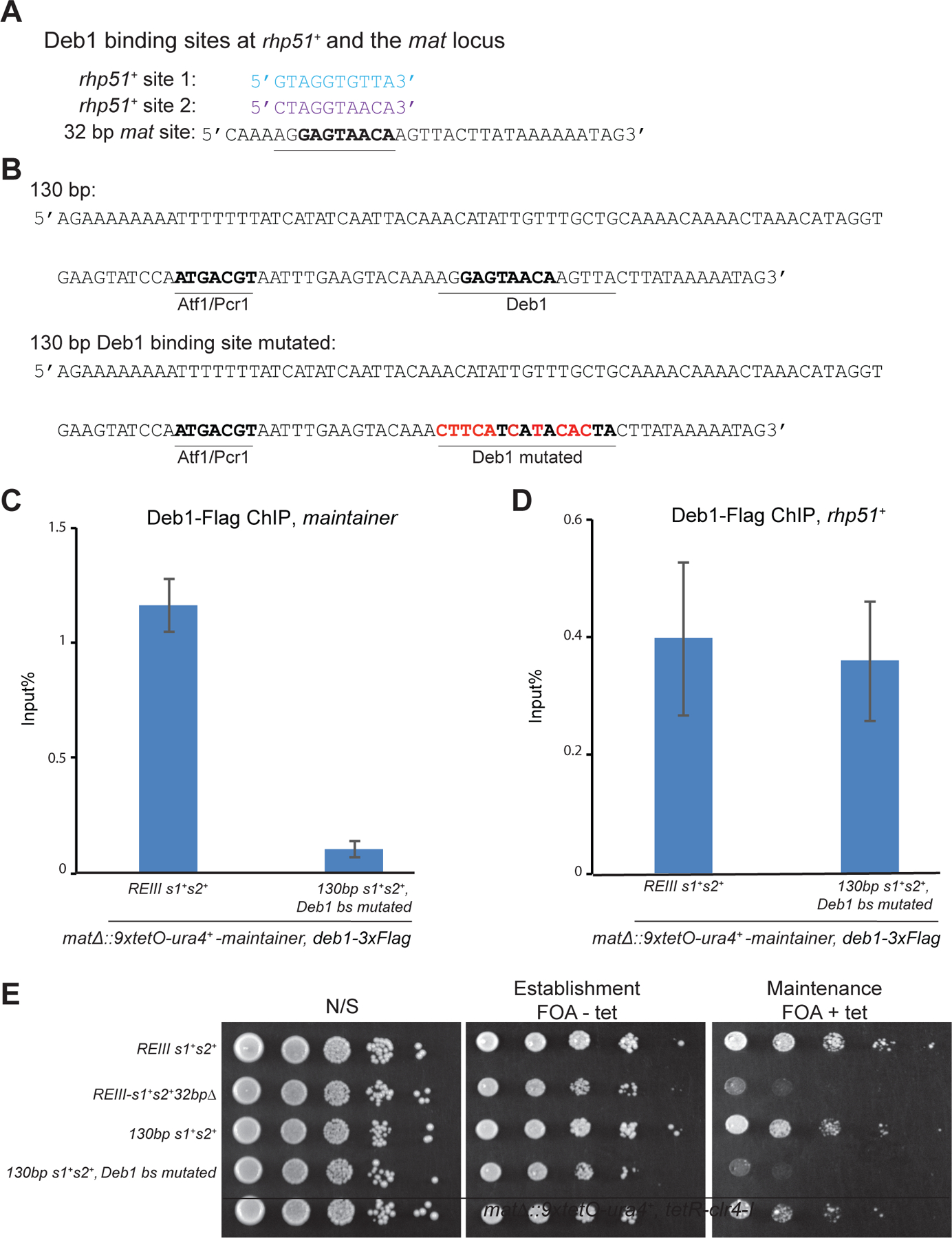

Figure 3. Mutation of the Deb1 binding site in the maintainer abolishes its ability to mediate epigenetic inheritance.

(A) DNA sequence comparison of the two previously reported Deb1 binding sites (rhp51+ promoter) and the putative Deb1 binding site in the 32 bp DNA sequence at the mat locus required for maintenance. Sequences showing similarity with the putative Deb1 binding site in the maintainer are shown in bold letters. (B) DNA sequence of the wild-type and Deb1 binding site-mutated 130-bp region are shown. Mutated bases are highlighted in red color. (C, D) ChIP experiments showing that mutation in the Deb1 binding site abolishes Deb1 localization to the maintainer region (C) but does not affect its binding to the promoter of its euchromatic target, rhp51+ (D). n=2 biological replicates (E) Silencing assays showing that deletion of the 32 bp element and mutations in the Deb1 binding site (Deb1 bs mutated) have similar loss of maintenance phenotypes.

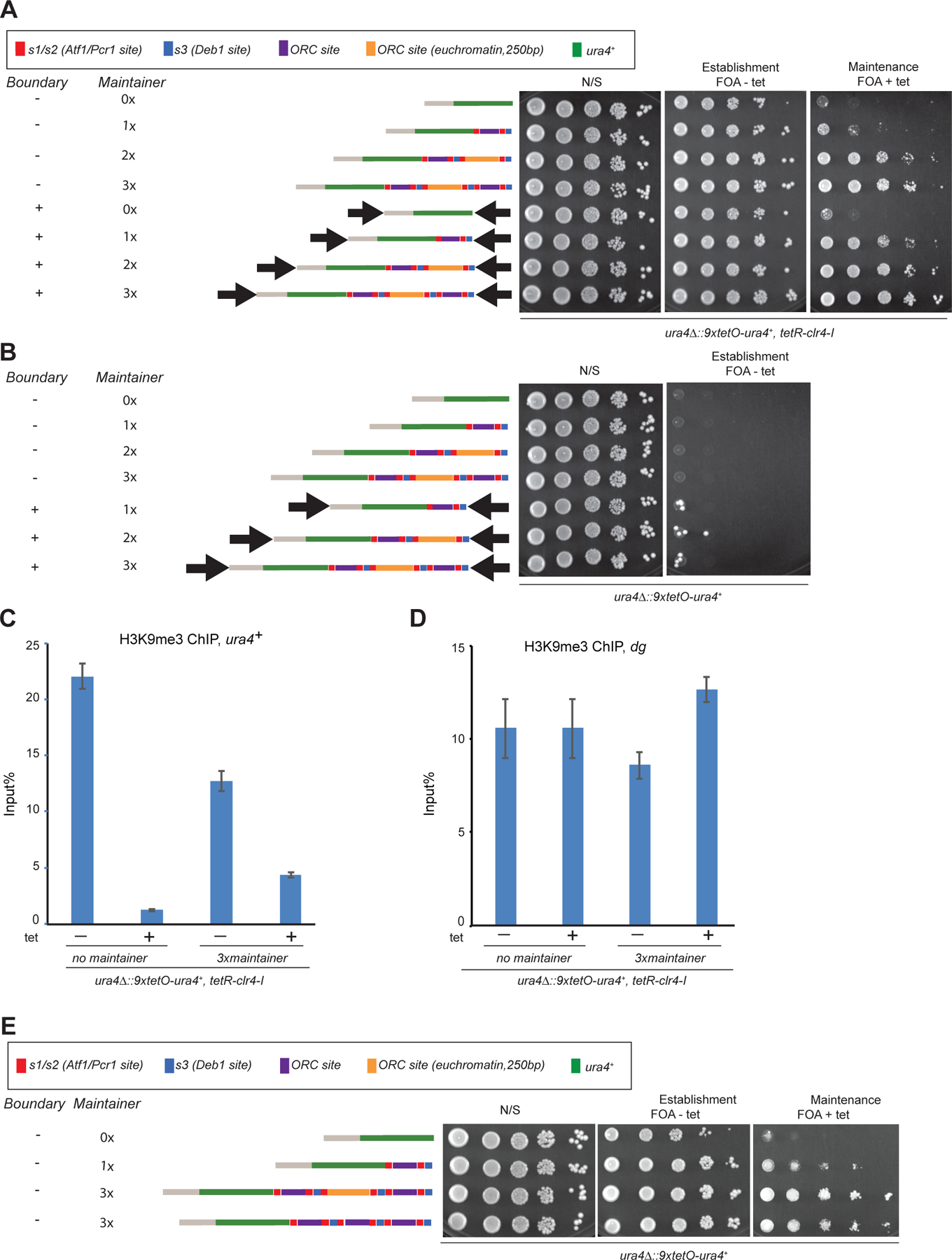

Further deletion of a 50 bp region in the 130-bp maintainer (50bp∆), to the left of the Atf1/Pcr1 binding sites, leaving the Atf1/Pcr1 and Deb1 binding sites intact, led to weaker maintenance (Figure 4A, B; Figure S2C). This observation suggested that at least one or more other DNA-binding protein(s) were required for full maintainer function. To identify the potential DNA binding protein(s), we designed two overlapping 49-bp and 53-bp oligonucleotides that contained the additional sequences required for maintainer function (Figure 4C, sequences underlined with green and red lines). We used the oligonucleotide pull-down approach with the same controls described earlier for identification of Deb1. Mass spectrometry analysis of the proteins bound to these oligonucleotides showed that the top enriched protein, which was shared in the two pull-downs, was Orc4 (Figure 4D, E). Orc4 is a subunit of the Origin Recognition Complex (ORC), which contains 6 subunits Orc1-Orc6 (Bell and Stillman, 1992). In S. cerevisiae, ORC recognizes a consensus sequence at origins of DNA replication (Bell and Dutta, 2002) but S. pombe Orc4, the DNA binding subunit of ORC in this organism, is thought to bind to AT-rich sequences usually spanning several hundred base pairs of DNA (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001). Consistent with these observations, the region of the 130-bp element used in the above pull-downs is highly AT-rich (79%, Figure 4C). To test the importance of these AT-rich putative Orc4/ORC binding sites in maintainer function, we generated a series of AT to GC mutations within the region (Figure S2C, highlighted in yellow). As shown by growth silencing assays, AT to GC mutations within the element phenocopied the effect of deleting the entire 50 bp AT-rich region (Figure 4F). Consistent with these results, ChIP enrichment of the Orc1 subunit of ORC (5xFlag-Orc1) at the mat locus was reduced upon deletion of the REIII element (Figure S2E-G). Further, if ORC binding sites were required for maintainer function, other ORC binding sites may be expected to functionally replace the putative ORC binding site in the element. To test this possibility, we constructed cells in which the endogenous ORC binding sites in the 130-bp region were replaced by the 250 bp ARS3002 sequence, which has been shown previously to bind to ORC (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001) (Figure S2D). The results showed that the ARS3002 sequence rescued the maintenance defect resulting from the deletion of the putative ORC binding site (Figure 4G), suggesting that ORC is the third DNA-binding protein complex that is required for maintainer function.

Figure 4. Identification of ORC as a maintainer-binding protein complex.

(A) Schematic diagram of the mating type (mat) locus showing the location of a 50 bp deletion upstream of the s2 site (mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+-REIII s1+s2+ versus mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+-REIII s1+s2+ 50bp∆). (B) Growth silencing assays showing that deletion of the 50 bp sequence results in defective maintenance. (C) DNA sequence of the 130-bp maintainer region and the oligonucleotides used for pull down experiments. Target oligo 2 corresponds to the first 49 bp of the 50 bp deletion and is underlined with green; target oligo 3, underlined red. The binding sites for Atf1/Pcr1 and Deb1 are indicated for reference. (D, E) Mass Spectrometry identification of proteins enriched in oligo 2 (D) and oligo 3 (E) pull downs normalized to the s1 oligo. n=1 technical replicates. (F) Silencing assays showing that the mutated 50 bp putative ORC binding site phenocopies deletion of the entire region. See Figure S3a for substitution in the ORC binding site. (G) Silencing assays showing that the maintenance defect resulting from deletion of the 50 bp ORC binding site could be rescued by insertion of a 251 bp euchromatic ARS sequence with known ORC recruitment activity.

To further test if additional DNA sequences within the 130-bp element were required for its maintainer function, we performed a deletion analysis of DNA sequence within the element that were not represented in the oligonucleotide pull-down assays (Figure S3). Replacement of sequences that were 10–20 bp, or 20–30 upstream of s2 site with random sequence has no effect on maintainer function (Figure S3A, B). We also replaced the DNA sequences immediately flanking the Atf1/Pcr1 s2 site (10 bp upstream and 11 bp downstream) with the flanking region of a euchromatin Atf1/Pcr1 binding site localized at SPNCRNA.458 (Figure S3). Replacing the s2 flanking sequences led to weaker maintenance mediated by the 130-bp element. We then tested whether the deleted sequence itself was important, for maintainer function or the alternative that the addition of euchromatic sequences perturbed maintenance. We inserted the flanking sequence of SPNCRNA.458 Atf1/Pcr1 binding site immediately upstream and downstream of the s2 site, without deleting any endogenous maintainer sequence. In support of the latter hypothesis, the insertion of euchromatic sequences weakened maintenance to the same extent as replacing the flanking sequence of s2 (Figure S3A, B). This result suggests that the sequences surrounding the s2 site contribute to maintainer function, but most likely through Atf1/Pcr1 binding, rather than recruitment of another DNA-binding protein. Altogether, we analyzed all of the sequences within the 130-bp element by deletion and replacement except for 6 bp upstream and 18 bp downstream of the Deb1 binding site. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that these sequences may contribute to maintainer function by recruiting other factors, we note that they were included in the 32 bp oligonucleotide pulldown experiment (Figure 2E), which did not identify proteins other than Deb1.

The above results suggest that a functional maintainer contains binding sites for Atf1/Pcr1, Deb1 and ORC. Certain mutations in these DNA binding proteins would therefore be expected to abolish maintainer function. Cells with deletions of either Atf1 or Pcr1 grow very poorly and Deb1, as well as every subunit of ORC, are essential for viability (Bell, 2002; Shim et al., 2000; Takeda et al., 1995). We therefore designed a strategy to isolate viable alleles in these factors that may specifically disrupt epigenetic maintenance. We constructed a strain in which the 9xtetO-ura4+ reporter gene at the mat locus was replaced with a 9xtetO-ade6+ reporter gene, followed by the REIII maintainer. Cells in which 9xtetO-ade6+ is silenced form red colonies allowing us to use an assay based on colony color to perform a genetic screen for viable mutations in the above factors that abolish maintainer function. We first modified the endogenous copy of the atf1+ gene to generate cells expressing a series of different Atf1 truncation, which left its DNA-binding domain intact and had wild-type growth rates (Figure S4). The results showed that a region of Atf1 located between amino acids 106 to 202 (Epigenetic Maintenance Domain, EMD) was required for maintainer-dependent epigenetic inheritance of silencing (Figure S4). Furthermore, using PCR mutagenesis, we obtained point mutations in Deb1 (W177R and M213V) and Orc1 (E129A) subunit of the ORC complex that abolished or reduced epigenetic maintenance but did not affect growth (Figure S5B, C). Interestingly, the Orc1-E129A mutation with severe maintenance defects localized to the Bromo adjacent homology (BAH) domain (Figure S5C), which is also required for the silencing activity of ORC in budding yeast (Zhang et al., 2002). Furthermore, combining the Orc1-E129A mutation with 50 bp deletion of the ORC binding site in the maintainer (130b s1+ s2+ 50bp∆, Figure 4F) resulted in a stronger maintenance defect for the mat∆::9xtetO-ura4+ reporter than either single mutation (Figure S5D). This result is consistent with the possibility that the 50 bp deletion does not completely abolish ORC binding to the maintainer since it does not remove all AT-rich sequences, although we cannot rule out the possibility that Orc1-E129A mutation has a general effect on epigenetic inheritance of silencing. Altogether, these results indicate that specific mutations in Atf1/Pcr1, Deb1 and ORC, which are located outside of their known DNA-binding domains, compromise maintainer function.

To test if maintainer-binding proteins interact directly with components of the CLRC complex we performed yeast two hybrid assays. Although the full length Deb1 fusion protein is toxic to yeast cells, we could express the N terminal fragment of Deb1(1–200) and found that it interacted with the Raf1 and Rik1 subunits of CLRC (Figure S6). Moreover, these interactions were weakened by the Deb1-W177R mutation, which abolishes maintainer function in vivo (Figure S6A, B), suggesting that the ability of Deb1 to interact with CLRC is critical for maintainer function. We also analyzed immune-purified Deb1-Flag using mass spectrometry and failed to detect Raf1, Rik1, or other subunits of the CLRC complex, suggesting that the interaction of isolated maintainer-binding proteins with the CLRC complex may be too weak to detect in whole cell extracts.

Maintainer is Sufficient for Epigenetic Inheritance

To investigate whether the epigenetic maintainer could act in a locus-independent manner, we generated cells with the minimal 130-bp element inserted at an ectopic locus. We previously showed that the IR-L and IR-R boundary sequences that flank the mat locus are necessary for epigenetic maintenance, but the nature of this requirement had remained unknown. Consistent with the requirement for the boundary elements in epigenetic maintenance at the native mat locus, the minimal maintainer alone mediated only weak maintenance of silencing when we inserted the 9xtetO-ura4+ reporter at the euchromatin ura4+ locus, unless it was flanked by the boundary sequences (Figure 5A, compare rows 1 and 2 with rows 5 and 6). Therefore, together with the boundary elements, the 130-bp element was sufficient for epigenetic maintenance independently of chromosomal location. We next asked whether the boundary sequences were absolutely essential for maintenance or could be bypassed by increasing the copy number of the 130-bp element. We found that 2 and 3 copies of the element showed increasing maintenance activity at the ectopic locus, whether the boundary elements were present or not (Figure 5A, compare rows 3 and 4 with rows 7 and 8, Figure 5E). The boundary elements therefore play a potentiating, rather than essential, role in maintainer function. Moreover, the IR-L and IR-R boundary elements were fully effective in promoting epigenetic maintenance when both were inserted at the centromere-proximal side of the reporter locus but not when inserted at the telomere-proximal side (Figure S7C), indicating that the 130-bp element did not need to be flanked by the boundary elements to be functional. At the ectopic locus, the boundary elements are likely to protect the H3K9me domain from anti-silencing effects of adjacent euchromatin, as is the case with their roles at the mat locus (Charlton et al., 2020; Thon et al., 2002). In the absence of the TetR-Clr4-I initiator, even at increased copy number, with or without the boundary elements, the 130-bp element showed little or no de novo silencing establishment activity, indicating that it could not function as a conventional silencer (Figure 5B). Consistent with the growth silencing assays, ChIP-qPCR experiments showed that 3 copies of the element inserted upstream of the reporter locus were sufficient for maintenance of H3K9me3 72 hours after tetracycline-mediated release of TetR-Clr4-I (Figure 5C). As controls, the presence of the 130-bp element and Tetr-Clr4-I at the ura4+ locus had little or no effect on H3K9me levels at the pericentromeric dg repeats (Figure 5D). Together these results demonstrate that the element, on its own, is sufficient for epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation.

Figure 5. The role of boundary sequences and maintainer copy number in epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing.

(A) Silencing assays showing that increasing the copy number of the maintainer bypasses the requirement for boundary sequences and is associated with stronger maintenance of silencing. Red: Atf1/Pcr1 binding site. Blue: Deb1 binding site. Purple: ORC binding site. Orange: euchromatic ORC binding site (250bp ARS3002 sequence). (B) Silencing assays showing that increasing the copy numbers of the maintainer does not convert it into a silencer that can establish silencing. (C) ChIP experiments showing that the 3xmaintainer sequence is sufficient to mediate epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me at an ectopic locus. (D) Control H3K9me ChIP results for pericentromeric heterochromatin for the same strains as in C. n=2 biological replicates. (E) Silencing assay showing that the 3x maintainer remained functional when one of the AT-rich ORC binding sites was replaced with a euchromatic ORC binding.

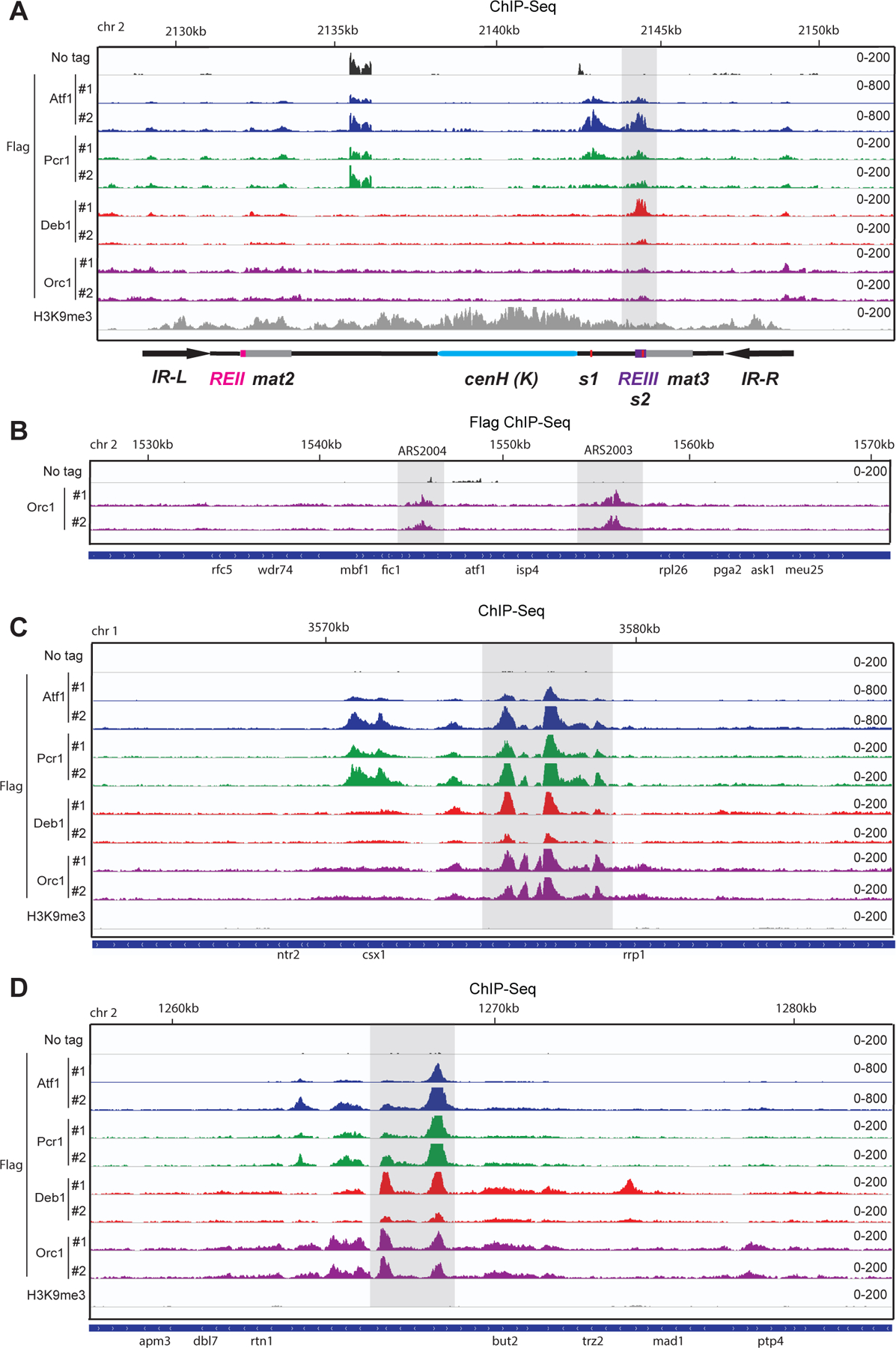

To gain insight into the genome-wide localization of maintainer-binding proteins and in particular their distribution at the mat locus, we performed a ChIP-Seq experiment of Flag tagged Atf1, Pcr1, Deb1 and Orc1. At the mat locus, consistent with the ChIP-qPCR results and previous reports, ChIP-seq showed two peaks for each Atf1-Flag and Pcr1-Flag, which were lost when we deleted the Atf1/Pcr1 consensus sites (Figure 6A and Figure S7A). Although the ChIP seq of Atf1 and Pcr1 was performed in CenH∆ background, previous ChIP-qPCR experiments did not detect Atf1 or Pcr1 localization at cenH (Jia et al., 2004). Deb1-Flag showed only one peak of binding, which localized at the REIII region (Figure 6A), consistent with its association with the 30 bp fragment of the maintainer element (Figure 2). For Flag-Orc1, we only observed very weak enrichment at REIII and the boundary sequences, suggesting that ORC associates with the AT-rich region of the 130-bp element weakly (Figure 6A). In contrast, we observed stronger peaks of Flag-Orc1 localization to known ARS regions such as ARS2003 and ARS 2004 (Figure 6B, Figure S7B)(Okuno et al., 1997). Despite this apparently weak Flag-Orc1 localization, it has previously been reported that sequences flanking the mat3 gene or the boundary sequence are both sufficient to drive the replication of a plasmid in S. pombe (Thon et al., 1999; Thon et al., 2002), indicating that sequences at the REIII region can act as functional ORC binding sites.

Figure 6. Genomic localization of Atf1, Pcr1, Deb1, and Orc1.

(A) Atf1-Flag, Pcr1-Flag, Deb1-Flag and Flag-Orc1 ChIP-Seq reads mapped to the mating type locus. Note that the Atf1-Flagand Pcr1-Flag ChIP was performed in cenH∆ cells. H3K9me3 ChIP seq data is from Iglesias et al., 2018. Top: chromosomal coordinates. Bottom: genes. Numbers of reads per million were shown on the right of the tracks.

(B) Flag-Orc1 ChIP-seq reads mapped to known ORC binding site ARS2003 and ARS2004.

(C) and (D) ChIP-Seq showing examples of co-localization of Atf1,Pcr1,Deb1 and ORC at euchromatin loci.

At the genome-wide level, we observed numerous binding sites for each Atf1-Flag, Pcr1-Flag, Deb1-Flag, and Flag-Orc1, and at least 49 instances in which their binding sites were co-localized (Figure 6C, Table S4). Consistent with our findings that the 130-bp element cannot establish de novo H3K9 methylation, none of the co-localization regions were associated with H3K9 methylation (Figure 6C, D). Furthermore, the requirement for either oligomerization of the 130-bp element or its association with boundary elements (Figure 5), to maintain silencing, suggests that the euchromatic binding sites will lack maintainer function.

Evidence that the 130-bp Element Can Initiate H3K9me

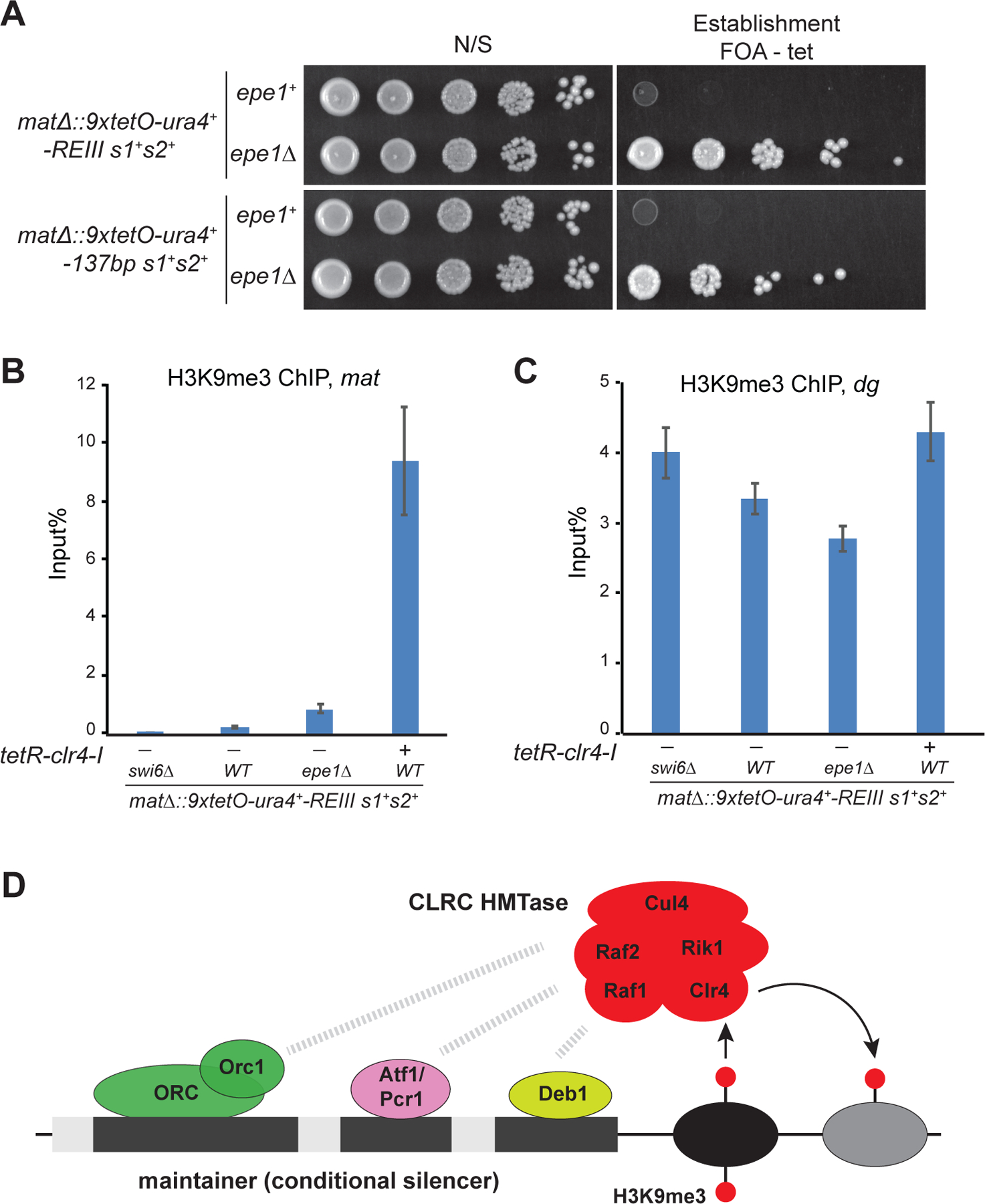

We next addressed the mechanism of maintainer action. Two mutually non-exclusive models can explain maintainer function (Wang and Moazed, 2017). In the first model, maintainer-binding proteins together with pre-existing H3K9me may act cooperatively to recruit Clr4 (Moazed, 2011). In the second model, the element forms a permissive chromatin or nuclear environment for the Clr4 read-write to copy pre-existing H3K9me. If the first model were correct, it may be possible to convert a maintainer from a functionally inert state into a state in which it could act as a silencer, which would only be possible if the element could recruit Clr4 de novo, directly or indirectly, to initiate H3K9me. In an attempt to distinguish between these possibilities, we deleted the gene encoding the anti-silencing factor epe1+ because previous studies have demonstrated that Epe1 promotes H3K9 demethylation and increases the threshold Clr4 activity required to initiate ectopic H3K9me (Iglesias et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2015). As shown in Figure 7A, deletion of epe1+ allowed both the REIII element and the 137 bp maintainer to initiate de novo silencing, acting as silencers. This silencing correlated with increased levels of H3K9me3 at the 130-bp element, but not a control locus, in epe1∆ cells (Figure 7B, C). Interestingly, low levels of H3K9me were present at the 130-bp region even in epe1+ cells but likely at levels which were too low to promote silencing of the ura4+ reporter gene (Figure 7B). To further test if the element alone without the boundary sequences could be converted into a silencer, we deleted epe1+ in 3x maintainer cells in which the maintainer and the 9xtetO-ura4+ reporter were inserted at the euchromatic ura4+ locus. Deletion of epe1+ resulted in only a low frequency of FOA resistant cells (~0.0005%), suggesting weak establishment (Figure S7D). However, the resulting FOA resistant cells could be stably propagated following replating, indicating that once established the silent state was stably maintained (Figure S7D). This could represent a low frequency of heterochromatin establishment or a genetic mutation in the ura4+ gene. To distinguish between these possibilities, we isolated FOA-resistant colonies and tested whether the silencing of ura4+ was dependent on heterochromatin proteins. Deletion of either swi6+ or clr4+ abolished maintainer-induced FOA resistance, indicating the observed FOA-resistant colonies resulted from maintainer-dependent establishment of silencing (Figure S7D). In support of the direct cooperativity model, these results demonstrate that the maintainer can act as a silencer when the anti-silencing factor epe1+ is removed, indicating that it can initiate de novo Clr4 recruitment and H3K9 methylation.

Figure 7. Deletion of Epe1 converts the maintainer to a silencer.

(A) Silencing assays showing that in epe1∆ cells the maintainer can establish de novo gene silencing. (B, C) ChIP experiments showing that in epe1∆ cells the maintainer can mediate de novo establishment of H3K9me3 at the ura4+ reporter gene inserted in the mat locus (B) without affecting H3K9me3 at the control pericentromeric heterochromatin locus (C). n=2 biological replicates. (D) Schematic diagram of the minimal maintainer and model for the recruitment of the Clr4-containing CLRC complex and methylation of H3K9 on newly deposited nucleosomes (new). CLRC recruitment requires input from maintainer-binding proteins and H3K9me on preexisting or inherited H3K9me3 (old). Maintainer-binding proteins may also participate in recruitment of other proteins that facilitate heterochromatin formation.

Discussion

Our findings reveal a minimal DNA element, termed maintainer, that is sufficient for epigenetic maintenance of H3K9me and gene silencing. Like silencers and enhancers, this epigenetic maintainer is a combinatorial DNA element containing binding sites for multiple site-specific DNA-binding factors, which are located within a 130-bp region. However, unlike enhancers and silencers, in wild-type cells, this maintainer element lacks de novo activity and cannot initiate H3K9me and silencing. Notably, deletion of epe1+, which encodes an anti-silencing and anti-inheritance protein (Audergon et al., 2015; Bao et al., 2019; Ragunathan et al., 2015; Raiymbek et al., 2020; Trewick et al., 2007), allows the maintainer to act as a silencer, revealing its inherent ability to recruit the Clr4/Suv39h H3K9 methyltransferase. A maintainer can thus be thought of as a conditional silencer whose activity can be regulated by anti-silencing factors such as Epe1. In the context of a wild-type mating type locus, the maintainer may also promote the RNAi-nucleated spreading of heterochromatin and gene silencing (Greenstein et al., 2018). The maintainer defines a new type of DNA sequence that becomes functional in the context of specific histone post-translational modifications, in the case of S. pombe heterochromatin, methylation of histone H3K9 that is inherited following DNA replication and cell division.

A key question regarding the role of maintainer DNA sequences in epigenetic inheritance is how such sequences can help maintain pre-existing histone modifications while lacking the ability to initiate de novo modification events. This feature is fundamental to the ability of a maintainer to act as an epigenetic memory module whose activity is history-dependent. The composite architecture of the maintainer provides a possible explanation for its H3K9me-dependent function in maintaining heterochromatin. The maintainer contains binding sites for Atf1/Pcr1, Deb1, and ORC, all of which have numerous binding sites outside of the heterochromatic mat locus and play important or essential roles that do not involve heterochromatin formation. The unique property of these factors in the maintainer is likely due to their close juxtaposition, which allows them to make multiple weak interactions with the Clr4 complex or other heterochromatin factors (Figure 7D). While these weak interactions, together with input from preexisting H3K9me, are sufficient to recruit Clr4, they cannot efficiently recruit Clr4 in the absence of preexisting H3K9me. We note that the ORC has been identified with heterochromatin-associated functions as a maintainer-binding protein in S. pombe (this study), a silencer binding protein in S. cerevisiae (Bell et al., 1993), and an HP1-interacting protein in human cells (Prasanth et al., 2010). In mammalian cells, HP1 proteins physically associate with the Clr4 homolog, SUV39H1 (Wang et al., 2019). It will be interesting to investigate whether ORC functions in heterochromatin maintenance in mammals by providing a bridge between maintainer-like sequences and HP1/SUV39H.

Fission yeast appear to have the capability to maintain epigenetic information using multiple strategies. First, the read-write ability of the Clr4 methyltransferase can mediate DNA sequence-independent epigenetic inheritance of H3K9me and silencing (Audergon et al., 2015; Ragunathan et al., 2015). However, this sequence-independent inheritance rapidly decays within a few cell divisions and the inheritance of silencing can be more readily observed in cells lacking the anti-silencing factor Epe1. Second, in wild-type epe1+ cells, an siRNA amplification loop can be coupled to Clr4 read-write-mediated H3K9me to promote epigenetic inheritance (Yu et al., 2018). In this case, siRNAs act in a similar manner to the maintainer described here. In the absence of preexisting H3K9me, the ability of siRNAs to initiate H3K9me at euchromatic loci is opposed by RNA processing mechanisms that promote mRNA polyadenylation and export from the nucleus (Kowalik et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2018). However, when siRNA amplification is coupled to H3K9me, the two positive feedback loops reinforce each other and maintain silencing for multiple generations. Finally, our identification of a DNA maintainer element demonstrates that specific DNA sequences can define chromosomal regions within which, once established, H3K9me can be epigenetically maintained.

Since histone modification turnover and heterochromatin properties are highly conserved, cooperation between maintainer-like elements and preexisting modifications is likely to govern the heritability of chromatin states in other organisms. In Drosophila, specific DNA sequences called Polycomb Response Elements (PREs) are continuously required for epigenetic inheritance of H3K27 methylation (Coleman and Struhl, 2017; Laprell et al., 2017). Similarly, in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, silencer DNA elements are continuously required for maintenance of gene silencing (Cheng and Gartenberg, 2000; Holmes and Broach, 1996). Maintainer-based mechanisms can in principle act as temporal and spatial sensors that determine whether histone modifications such as H3K9me and H3K27me associated with developmentally regulated genes are epigenetically maintained or not. For example, in the absence of preexisting H3K9me, deposited early during development, genes with maintainers will be expressed later in development. However, when H3K9me is deposited at maintainer-containing genes during early development, the genes will retain H3K9me and will be kept silenced for multiple cell divisions. In this way, DNA maintainers may provide a potential mechanism that determines which subsets of histone modifications, established as a result of transient spatial cues early in development, are faithfully inherited later in development.

Limitations of the Study

Our findings suggest that the maintainer is a composite DNA element that can recruit the Clr4 methylransferase to initiate H3K9 methylation on newly deposited nucleosomes only in the presence of preexisting H3K9 methylation. We have proposed that the maintainer-binding proteins and preexisting H3K9 methylation work together to cooperatively recruit Clr4. The demonstration of such a cooperativity-based conditional recruitment mechanism requires in vitro biochemical experiments using purified components. Furthermore, additional studies are required to determine if the arrangement or distance between the binding sites in the maintainer are critical for its function. Our results also do not rule out the possibility that the mating type maintainer may recruit factors other than the Clr4 complex that may create a chromatin environment that is permissive for epigenetic inheritance of heterochromatin. Future studies are required to address this issue. Finally, our identification of the maintainer required the deletion of other DNA elements at the mating type locus that act redundantly with the REIII element to establish silencing. In the wild-type context, the maintainer therefore acts as a sub-element that ensures the robust establishment of silencing. Our findings identify potential routes for the evolution of maintainers from silencers, and vice versa, but additional studies in organisms that use epigenetic memory to maintain distinct gene expression patterns are required to determine whether and how evolved maintainer elements participate in propagation of epigenetic states.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Danesh Moazed (danesh@hms.harvard.edu).

Materials Availability

The materials generated in this study would be shared without restriction.

Data and Code Availability

The accession number for the raw and processed high-throughput sequencing data is GEO: GSE169537. The Python script used in this study is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Yeast strains

Schizosaccharomyces pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. S.pombe cells were grown at 32 °C either in liquid YES or YEA media at 220rpm or on solid agarose plates. YEA or YES plates were used to grow and maintain S. pombe.

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmids

Plasmids were constructed by restriction enzyme digestion followed by Gibson ligation, as previously reported (Wang and Moazed, 2017). Briefly, potential maintainer sequences were synthesized by IDT as gene blocks, which were then assembled to SalI and PacI digested pFA6A plasmid backbone with ura4+, 9xtetO sequence and a ~350 bp mat sequence used for homologous recombination by Gibson ligation (Gibson et al., 2009). Plasmids with Atf11 truncations and Flag tagged Deb1 were also constructed by Gibson ligation.

Strain construction

S. pombe strains were constructed as previously described (Wang and Moazed, 2017). Briefly, all strains are either constructed by transforming a PCR based targeting DNA fragment into cells by using lithium acetate protocol or by genetic crossing. To insert the reporter gene with maintainer sequences at the mat locus, swi6+ were first deleted and cenH was replaced with the ade6+ gene. The 9xtetO-ura4+ reporter, with different maintainer sequences, was then introduced to replace ade6+. swi6+ and TetR-Clr4 were then introduced by genetic crosses. To construct strains with the boundary sequences at ura4+ locus, the IR-L or IR-R boundary elements were first inserted into pFA6a plasmids containing hygromycin B (hph) or blasticidin (bsd), transformed into yeast cells and plated on medium containing hph or bsd to select for insertion into the ura4+ locus. 9xtetO- ura4+- maintainer cassette were introduced by transformation following insertion of the boundary sequences. Proper insertion was further verified by colony PCR.

Silencing assays

Cell with the ura4+ reporter gene were harvested by centrifugation after overnight growth at 32°C in yeast extract+adenine (YEA) medium (Forsburg and Rhind, 2006) followed by 5-fold serial dilution in H2O before plating on yeast extract+supplements (YES), and YES+FOA(2ug/ml) with or without tetracycline (5µg/ml). For cells with the ade6+ reporter gene, cells were spotted on yeast extract (YE) medium containing low adenine (Low Ade) or YE Low Ade with tetracycline (5µg/ml) for 3 days in 32°C and one day in 4°C before being photographed.

Quantitative Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qPCR)

ChIP experiments were performed as described previously (Wang and Moazed, 2017). For H3K9me3 ChIP experiments, cells from a 50 ml overnight (24 hours) culture at optical density (OD) of 1–2 (24hours), with or without tetracycline (5µg/ml), were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 minutes. Cells were quenched with 130 mM glycine for 5 minutes and pelleted before lysate preparation. For Flag ChIP, cells were first grown at 18°C for 2 hours before crosslinking with 1% formaldehyde at 18°C for 30 minutes. The following steps were performed as previously described (Egan et al., 2014). Specifically, the pellets were washed twice with 1xTBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and then resuspended in 600 µl lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors) in a 2 ml screw-cap tube. Cells were then lysed by bead beating with 1 ml acid-washed 0.5 mm glass beads with 3 cycles of 90 s at 4500 rpm and 1 cycle of 30s at 5000rpm on a MagNA Lyser Instrument (Roche). For preparation of ChIP-Seq samples, cells were lysed by bead beating on the same instrument with 6 cycles of 30s at 5000 rpm. Extracts were then sonicated for 3×20 s at 50% amplitude using a sonicator (Branson Digital Sonifier), centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 10 mins in a microfuge, and the supernatant was incubated with antibody. Antibodies used for ChIP experiments (per sample): 1 µg anti-H3K9me3 (Diagenode C15500003) and 4 µg anti-Flag (M2, Sigma) antibody for FLAG-tagged Atf1, Deb1 or Orc1. Immunoprecipitated DNA was then quantified by q-PCR using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system.

Sample preparation and analysis of ChIP-Seq

Library for illumine sequencing was performed as previously described following standard manufacture protocols, starting with 1–10ng immunoprecipitated DNA (Yu et al., 2018). Each library was generated by ligating with unique custom made adaptors. Libraries were pooled together and sequenced with Illumina HiSeq2500. Data analysis was also performed as previously described (Yu et al., 2018), reads mapped to repeat regions (IR-L, IR-R) were randomly assigned. The raw and processed reads can be accessed via accession number GSE169537. To call peaks of different DNA binding proteins, we used MACS2 and modified the parameters according to the yeast genome. Specifically, the following parameter was used to call peak: genome size:1.38e7 bp, bind width: 150bp, upper mfold: 200, lower mfold:3. To identify genomic locations that is bound by all four factors, regions with more than 40% overlap of peaks from all four proteins were calculated and are presented in Table S4.

Oligonucleotide Pull down

For each oligonucleotide (oligo) pulldown experiment, 40 μg of biotinylated double strand DNA oligos (IDT) were mixed with 200μl Streptavidin myOne C1 magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the binding buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5mM EDTA, 1 M NaCl) and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. Beads with immobilized DNA oligos were incubated with 3 ml of whole cell lysate (~20 mg/ml), prepared by using the following protocol. 1L cultures of cells were grown in YEA to OD600 of 1. Cell were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Hepes [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche)) and lysed by bead beating at 5,000 rpm for 6 × 45 sec using a MagNa Lyser (Roche). Beads with DNA and cell lysates were incubated for 3 hr at 4 °C. After the incubation, beads were washed 3 times with lysis buffer and incubated in a shaker with 500 mM NH4OH at 37 °C for 20 minutes to elute bound proteins, which were vacuum dried with centrifugation. For western blot analysis, dried elutes were resuspended in SDS sample buffer. 0.5% of input and 10% of bound proteins were run on a 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and blotted with mouse anti-Flag conjugated to HRP (Sigma A8592) at 1: 5,000 dilution. 90% of the bound protein was used for mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass spectrometry

Protein was eluted from beads using 500 mM ammonium hydroxide and the eluate was dried via vacuum centrifugation. We added 20 µl of 8 M urea, 100 mM EPPS pH 8.5 to the bead. We added 5mM TCEP and incubated the mixture for 15 min at room temperature. We then added 10 mM of iodoacetamide for 15min at room temperature in the dark. We added 15 mM DTT to consume any unreacted iodoacetamide. We added 180µl of 100 mM EPPS pH 8.5. to reduce the urea concentration to <1 M, 1 µg of trypsin, and incubated at 37°C for 6 hrs. The solution was acidified with 2% formic acid and the digested peptides were desalted via StageTip, dried via vacuum centrifugation, and reconstituted in 5% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid for LC-MS/MS processing.

All label-free mass spectrometry data were collected using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) coupled with a Famos Autosampler (LC Packings) and an Accela600 liquid chromatography (LC) pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated on a 100 μm inner diameter microcapillary column packed with ∼20 cm of Accucore C18 resin (2.6 μm, 150 Å, Thermo Fisher Scientific). For each analysis, we loaded ~2 μg onto the column. Peptides were separated using a 1 hr method from 5 to 29% acetonitrile in 0.125% formic acid with a flow rate of ∼300 nL/min. The scan sequence began with an Orbitrap MS1 spectrum with the following parameters: resolution 70,000, scan range 300−1500 Th, automatic gain control (AGC) target 1 × 105, maximum injection time 250 ms, and centroid spectrum data type. We selected the top twenty precursors for MS2 analysis which consisted of HCD high-energy collision dissociation with the following parameters: resolution 17,500, AGC 1 × 105, maximum injection time 60 ms, isolation window 2 Th, normalized collision energy (NCE) 25, and centroid spectrum data type. The underfill ratio was set at 9%, which corresponds to a 1.5 × 105 intensity threshold. In addition, unassigned and singly charged species were excluded from MS2 analysis and dynamic exclusion was set to automatic.

Mass spectrometric data analysis

Mass spectra were processed using a Sequest-based in-house software pipeline. MS spectra were converted to mzXML using a modified version of ReAdW.exe. Database searching included all entries from the S. pombe uniprot database which was concatenated with a reverse database composed of all protein sequences in reversed order. Searches were performed using a 50 ppm precursor ion tolerance. Product ion tolerance was set to 0.03 Th. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine residues (+57.0215Da) were set as static modifications, while oxidation of methionine residues (+15.9949 Da) was set as a variable modification

Peptide spectral matches (PSMs) were altered to a 1% FDR (Elias and Gygi, 2007, 2010). PSM filtering was performed using a linear discriminant analysis, as described previously (Huttlin et al., 2010). Briefly, target-decoy filtering was applied to control false discovery rates, employing a linear discriminant function for peptide filtering and probabilistic scoring at the protein level (Huttlin et al., 2010). We considered the following parameters: XCorr, ΔCn, missed cleavages, peptide length, charge state, and precursor mass accuracy. As such, peptide-spectral matches were identified, quantified, and collapsed to a 1% FDR and then further collapsed to a final protein-level FDR of 1%. Furthermore, protein assembly was guided by principles of parsimony to produce the smallest set of proteins necessary to account for all observed peptides. For quantification of differences between samples, we assigned a value of 0.5 to proteins with 0 peptides.

Yeast two hybrid assay

Yeast two hybrid (Y2H) assays were performed by using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System (Takara). Briefly, proteins of interest were cloned into vectors expressing the bait (GAL4 DNA-BD) and prey (GAL4 AD) as fusion proteins. Yeast cells expressing different bait and prey proteins were crossed and diploid cells were collected by picking colonies growing on selective medium (-Leu-Trp). Expression of the reporter genes reflected by growth in -Leu-Trp-Ade-His dropout medium indicated interaction between specific bait and prey pairs of proteins.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

For ChIP-qPCR, statistical analysis was performed using the two-tailed, two-sample unequal variance Student’s t test. Error bars show standard deviation (s.d.) and three replicates were performed for each experiment. Microsoft Excel was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

List of fission yeast S. pombe strains used in this study. Related to Figures 1–7

Supplementary Table 5

Mass spectrometry results of oligo1 pull-down experiment revealing the interaction of Deb1 with the 30-bp maintainer subelement. Related to figure 2.

Supplementary Table 6

Mass spectrometry results of oligo 2 and 3 pull-down experiments revealing the interaction of Orc4 with the AT-rich region of maintainer. Related to figure 4.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# F1804; RRID:AB_262044 |

| Monoclonal recombinant H3K9me3 | Diagenode | Cat# C15500003 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Flag M2-Peroxidase | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A8592; RRID:AB_439702 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Pierce Silver Stain SNAP Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 24612 |

| PMSF | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 36978 |

| cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 05056489001 |

| 0.5mm glass beads 10 lbs bulk container | BioSpec | Cat# 11079105 |

| Dynabeads Protein G | Invitrogen | Cat# 1004D |

| Dynabeads Protein A | Invitrogen | Cat# 100–02D |

| Formaldehyde, 37% | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# F79–500 |

| Proteinase K | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 03115828001 |

| Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol 25:24:1 Saturated | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P2069–100ML |

| Glycogen | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 10901393001 |

| Acid-Phenol: Chloroform, pH 4.5 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# AM9720 |

| Chloroform | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# BP1145–1 |

| DNase I, RNase free | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 04716728001 |

| Superscript III reverse transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat# 18080–044 |

| T4 DNA Polymerase | NEB | Cat# M0203L |

| T4 Polynucleotide kinase | NEB | Cat# M0201L |

| DNA Polymerase I, Large (Klenow) Fragment | NEB | Cat# M0210S |

| Klenow Fragment (3’/5’ exo–) | NEB | Cat# M0212L |

| Quick Ligase | NEB | Cat# M2200L |

| T5 Exonuclease | NEB | Cat #M0663 |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | NEB | Cat #M0530S |

| Taq DNA Ligase | NEB | Cat #M0208S |

| DNA Size Selector I | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# NC1148310 |

| G418 sulfate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11811031 |

| Hygromycin B | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 10843555001 |

| 5-Fluoroorotic acid monohydrate | Goldbio | Cat#F-230–10 |

| Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11206D |

| Dynabead MyOne Streptavidin C1 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 65001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28106 |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat# Q32854 |

| NucleoSpin_ Extract | Takara/Clontech | Cat# 740609.250 |

| MiniElute Reaction Cleanup kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28206 |

| SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 34577 |

| Supersignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 34095 |

| Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Takara/Clontech | Cat# 630489 |

| Deposited data | ||

| ChIP-seq data | This study | GEO169537 |

| Mass spectrometry | Tables S5 and S6 | PXD027214 |

| Experimental models: organisms/strains | ||

| S. pombe strains | Table S1 | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers and biotinylated oligos | Table S2 | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmids | Table S3 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Bowtie | N/A | RRID:SCR_005476 |

| IGV | N/A | RRID:SCR_011793, https://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/ |

| macs2–2.1.2 | N/A | RRID:SCR_013291 https://pypi.org/project/MACS2/ |

| BEDTools | N/A | RRID:SCR_006646 |

| Microsoft Excel | N/A | RRID:SCR_016137 https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/ |

Article highlights.

A composite DNA element acts as a maintainer of epigenetic memory in heterochromatin

Maintainer contains binding sites for Atf1/Pcr1, Deb1, and the Origin Recognition Complex

Maintainer functions at native and ectopic loci

Maintainer works together with preexisting H3K9me3 to recruit Clr4Suv39h

Acknowledgements.

We thank Hisao Masukata for a gift of strain SPY8500, Wayne Wahls for a gift of Atf1 plasmids, members of Moazed labs for helpful discussions, and Swapnil Parhad, Gergana Shipkovenska and Andy Yuan for comments on the manuscripts, and Andy Yuan for suggesting the term maintainer. This work was support by the National Institutes of Health grants GM132129 (J.A.P.), GM67945 (S.P.G.), and GM072805 (D.M.). D.M. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Allshire RC, and Madhani HD (2018). Ten principles of heterochromatin formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 229–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audergon PN, Catania S, Kagansky A, Tong P, Shukla M, Pidoux AL, and Allshire RC (2015). Epigenetics. Restricted epigenetic inheritance of H3K9 methylation. Science 348, 132–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub N, Goldshmidt I, Lyakhovetsky R, and Cohen A (2000). A fission yeast repression element cooperates with centromere-like sequences and defines a mat silent domain boundary. Genetics 156, 983–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao K, Shan CM, Moresco J, Yates J 3rd, and Jia S (2019). Anti-silencing factor Epe1 associates with SAGA to regulate transcription within heterochromatin. Genes Dev 33, 116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP (2002). The origin recognition complex: from simple origins to complex functions. Genes Dev 16, 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP, and Dutta A (2002). DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem 71, 333–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP, Kobayashi R, and Stillman B (1993). Yeast origin recognition complex functions in transcription silencing and DNA replication. Science 262, 1844–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SP, and Stillman B (1992). ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex [see comments]. Nature 357, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SJ, Jorgensen MM, and Thon G (2020). Integrity of a heterochromatic domain ensured by its boundary elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 21504–21511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TH, and Gartenberg MR (2000). Yeast heterochromatin is a dynamic structure that requires silencers continuously. Genes Dev 14, 452–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RT, and Struhl G (2017). Causal role for inheritance of H3K27me3 in maintaining the OFF state of a Drosophila HOX gene. Science [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan ED, Braun CR, Gygi SP, and Moazed D (2014). Post-transcriptional regulation of meiotic genes by a nuclear RNA silencing complex. RNA 20, 867–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwall K, Olsson T, Turner BM, Cranston G, and Allshire RC (1997). Transient inhibition of histone deacetylation alters the structural and functional imprint at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 91, 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, and Gygi SP (2007). Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods 4, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, and Gygi SP (2010). Target-decoy search strategy for mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Methods Mol Biol 604, 55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsburg SL, and Rhind N (2006). Basic methods for fission yeast. Yeast 23, 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd, and Smith HO (2009). Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6, 343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein RA, Jones SK, Spivey EC, Rybarski JR, Finkelstein IJ, and Al-Sady B (2018). Noncoding RNA-nucleated heterochromatin spreading is intrinsically labile and requires accessory elements for epigenetic stability. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, and Klar AJ (1996). Chromosomal inheritance of epigenetic states in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell 86, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KR, Hazan I, Shanker S, Watt S, Verhein-Hansen J, Bahler J, Martienssen RA, Partridge JF, Cohen A, and Thon G (2011). H3K9me-independent gene silencing in fission yeast heterochromatin by Clr5 and histone deacetylases. PLoS Genet 7, e1001268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SG, and Broach JR (1996). Silencers are required for inheritance of the repressed state in yeast. Genes Dev 10, 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttlin EL, Jedrychowski MP, Elias JE, Goswami T, Rad R, Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Haas W, Sowa ME, and Gygi SP (2010). A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 143, 1174–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias N, Currie MA, Jih G, Paulo JA, Siuti N, Kalocsay M, Gygi SP, and Moazed D (2018). Automethylation-induced conformational switch in Clr4/Suv39h maintains epigenetic stability. Nature DOI 10.1038/s41586-018-0398-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, Noma K, and Grewal SI (2004). RNAi-independent heterochromatin nucleation by the stress-activated ATF/CREB family proteins. Science 304, 1971–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, and DePamphilis ML (2001). Site-specific DNA binding of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex is determined by the Orc4 subunit. Mol Cell Biol 21, 8095–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalik KM, Shimada Y, Flury V, Stadler MB, Batki J, and Buhler M (2015). The Paf1 complex represses small-RNA-mediated epigenetic gene silencing. Nature 520, 248–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laprell F, Finkl K, and Muller J (2017). Propagation of Polycomb-repressed chromatin requires sequence-specific recruitment to DNA. Science [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, and Reinberg D (2010). Chromatin structure and the inheritance of epigenetic information. Nat Rev Genet 11, 285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D (2011). Mechanisms for the inheritance of chromatin states. Cell 146, 510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno Y, Okazaki T, and Masukata H (1997). Identification of a predominant replication origin in fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth SG, Shen Z, Prasanth KV, and Stillman B (2010). Human origin recognition complex is essential for HP1 binding to chromatin and heterochromatin organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 15093–15098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst AV, Dunleavy E, and Almouzni G (2009). Epigenetic inheritance during the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10, 192–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M (2014). The chemistry of regulation of genes and other things. J Biol Chem 289, 5417–5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M, and Gann A (2001). Genes and Signals (New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Radman-Livaja M, Verzijlbergen KF, Weiner A, van Welsem T, Friedman N, Rando OJ, and van Leeuwen F (2011). Patterns and mechanisms of ancestral histone protein inheritance in budding yeast. PLoS biology 9, e1001075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragunathan K, Jih G, and Moazed D (2015). Epigenetic inheritance uncoupled from sequence-specific recruitment. Science 348, 1258699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiymbek G, An S, Khurana N, Gopinath S, Larkin A, Biswas S, Trievel RC, Cho US, and Ragunathan K (2020). An H3K9 methylation-dependent protein interaction regulates the non-enzymatic functions of a putative histone demethylase. Elife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanso M, Vargas-Perez I, Garcia P, Ayte J, and Hidalgo E (2011a). Nuclear roles and regulation of chromatin structure by the stress-dependent MAP kinase Sty1 of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Microbiol 82, 542–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanso M, Vargas-Perez I, Quintales L, Antequera F, Ayte J, and Hidalgo E (2011b). Gcn5 facilitates Pol II progression, rather than recruitment to nucleosome-depleted stress promoters, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res 39, 6369–6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim YS, Jang YK, Lim MS, Lee JS, Seong RH, Hong SH, and Park SD (2000). Rdp1, a novel zinc finger protein, regulates the DNA damage response of rhp51(+) from Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Cell Biol 20, 8958–8968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, Toda T, Kominami K, Kohnosu A, Yanagida M, and Jones N (1995). Schizosaccharomyces pombe atf1+ encodes a transcription factor required for sexual development and entry into stationary phase. EMBO J 14, 6193–6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon G, Bjerling KP, and Nielsen IS (1999). Localization and properties of a silencing element near the mat3-M mating-type cassette of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 151, 945–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon G, Bjerling P, Bunner CM, and Verhein-Hansen J (2002). Expression-state boundaries in the mating-type region of fission yeast. Genetics 161, 611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trewick SC, Minc E, Antonelli R, Urano T, and Allshire RC (2007). The JmjC domain protein Epe1 prevents unregulated assembly and disassembly of heterochromatin. EMBO J 26, 4670–4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Reddy BD, and Jia S (2015). Rapid epigenetic adaptation to uncontrolled heterochromatin spreading. Elife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Gao Y, Zheng X, Liu C, Dong S, Li R, Zhang G, Wei Y, Qu H, Li Y, et al. (2019). Histone Modifications Regulate Chromatin Compartmentalization by Contributing to a Phase Separation Mechanism. Mol Cell 76, 646–659 e646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, and Moazed D (2017). DNA sequence-dependent epigenetic inheritance of gene silencing and histone H3K9 methylation. Science 356, 88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Fischle W, Sugiyama T, Allis CD, and Grewal SI (2005). The nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin by a histone deacetylase in fission yeast. Mol Cell 20, 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Jih G, Iglesias N, and Moazed D (2014). Determinants of heterochromatic siRNA biogenesis and function. Mol Cell 53, 262–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R, Wang X, and Moazed D (2018). Epigenetic inheritance mediated by coupling of RNAi and histone H3K9 methylation. Nature [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Hayashi MK, Merkel O, Stillman B, and Xu RM (2002). Structure and function of the BAH-containing domain of Orc1p in epigenetic silencing. Embo J 21, 4600–4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1

List of fission yeast S. pombe strains used in this study. Related to Figures 1–7

Supplementary Table 5

Mass spectrometry results of oligo1 pull-down experiment revealing the interaction of Deb1 with the 30-bp maintainer subelement. Related to figure 2.

Supplementary Table 6

Mass spectrometry results of oligo 2 and 3 pull-down experiments revealing the interaction of Orc4 with the AT-rich region of maintainer. Related to figure 4.

Data Availability Statement

The accession number for the raw and processed high-throughput sequencing data is GEO: GSE169537. The Python script used in this study is available from the lead contact upon request.