Significance

Selected gram-negative bacteria employ a type-IX secretion system to shuttle virulence proteins with a C-terminal domain (CTD) as a secretion signal across the outer membrane. Upon secretion, the CTD is cleaved and replaced with lipopolysaccharide by PorU, the only known bifunctional signal peptidase and sortase. We discovered that PorU transits between active monomers and latent dimers and determined the structure of the ∼260-kDa dimer. PorU consists of seven domains, including a gingipain-type catalytic domain, which is regulated by a long “latency β-hairpin” that forms an intermolecular β-barrel with the symmetric protomer. Homology modeling followed by in vivo validation revealed that PorU functions as a monomer through a cysteine–histidine catalytic dyad. Thus, dimerization provides an intermolecular mechanism for PorU regulation.

Keywords: periodontal disease, bacterial virulence factor, infectious disease, protein secretion, X-ray crystal structure

Abstract

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a keystone pathogen of the human dysbiotic oral microbiome that causes severe periodontitis. It employs a type-IX secretion system (T9SS) to shuttle proteins across the outer membrane (OM) for virulence. Uniquely, T9SS cargoes carry a C-terminal domain (CTD) as a secretion signal, which is cleaved and replaced with anionic lipopolysaccharide by transpeptidation for extracellular anchorage to the OM. Both reactions are carried out by PorU, the only known dual-function, C-terminal signal peptidase and sortase. PorU is itself secreted by the T9SS, but its CTD is not removed; instead, intact PorU combines with PorQ, PorV, and PorZ in the OM-inserted “attachment complex.” Herein, we revealed that PorU transits between active monomers and latent dimers and solved the crystal structure of the ∼260-kDa dimer. PorU has an elongated shape ∼130 Å in length and consists of seven domains. The first three form an intertwined N-terminal cluster likely engaged in substrate binding. They are followed by a gingipain-type catalytic domain (CD), two immunoglobulin-like domains (IGL), and the CTD. In the first IGL, a long “latency β-hairpin” protrudes ∼30 Å from the surface to form an intermolecular β-barrel with β-strands from the symmetric CD, which is in a latent conformation. Homology modeling of the competent CD followed by in vivo validation through a cohort of mutant strains revealed that PorU is transported and functions as a monomer through a C690/H657 catalytic dyad. Thus, dimerization is an intermolecular mechanism for PorU regulation to prevent untimely activity until joining the attachment complex.

The human oral microbiome comprises more than six billion bacteria from >770 species arranged in a homeostatic climax community (1). However, imbalance caused by diet and insufficient oral hygiene leads to dysbiosis, under which commensal and mutualistic species are outnumbered by opportunistic and pathogenic ones. These cause caries and periodontal disease (PD). Severe PD results in chronic inflammation and host-tissue destruction and is among the most prevalent infectious diseases of humanity. It affects 5 to 20% of middle-aged adults and up to 40% of older people in Europe according to the WHO (https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/oral-health/data-and-statistics). PD leads to tooth loss in severe cases, resulting in ∼30% of Europeans aged 65 to 74 y having no natural teeth anymore. Among PD-causing species is Porphyromonas gingivalis, a “keystone pathogen” of humans (2) that has been associated with several systemic diseases outside the oral cavity (3, 4).

Host–microbiome interactions are characterized by the microbial secretion of macromolecules into host cells or the extracellular milieu (5–7). In gram-negative bacteria, secretory proteins are produced in the cytoplasm and translocated across the inner membrane (IM) and the outer membrane (OM), which are separated by the periplasm and cell-wall peptidoglycan. For this purpose, they have evolved several types of secretion systems, including T1SS through T6SS, the chaperone–usher system, the type-IV pilus assembly pathway, and the most recently described T9SS (7), which was originally called the “Por Secretion System” (8) and “PerioGate” (6, 9). It is present in members of the gram-negative Bacteroidetes phylum (6–8, 10–12), with several copies of the system per cell (13). In P. gingivalis, the T9SS is the major secretion pathway, and it translocates at least 35 cargo proteins, including hallmark virulence factors such as the gingipain cysteine peptidases RgpA, RgpB, and Kgp (14). Cargoes participate in biofilm formation, nutrition, antibiotic resistance, and adhesion as well as virulence and the degradation of host proteins (6–8). Given the systemic implications of these pathogenic processes, the translocon has attracted considerable attention as a target for pharmaceutical intervention to treat severe PD (6), which leads to yearly worldwide productivity losses worth $39 billion (15).

The T9SS spans the entire cell envelope but is a pure OM translocator that operates jointly with the Sec general secretory pathway for initial transport of cargoes across the IM (Fig. 1). After subsequent removal of the N-terminal signal peptide in the periplasm, proteins fold and are directed to the T9SS by a C-terminal ∼9-kDa β-sandwich domain (CTD) (16), also known as the “T9SS signal” (11). This feature is unique among bacterial secretion systems, which normally deploy short N-terminal signal peptides (7); hence, T9SS cargoes are also referred to as “CTD proteins” (17, 18). After OM translocation, the CTD is generally removed by a signal peptidase, and selected cargoes are released into the environment in a soluble form. However, most cargoes are linked to anionic lipopolysaccharide (A-LPS) (19) through the new C terminus by sortase-type transpeptidation for anchorage to the extracellular side of the OM (20–25). In this location, OM-bound proteins form an electron-dense surface layer characteristic of P. gingivalis cells (26).

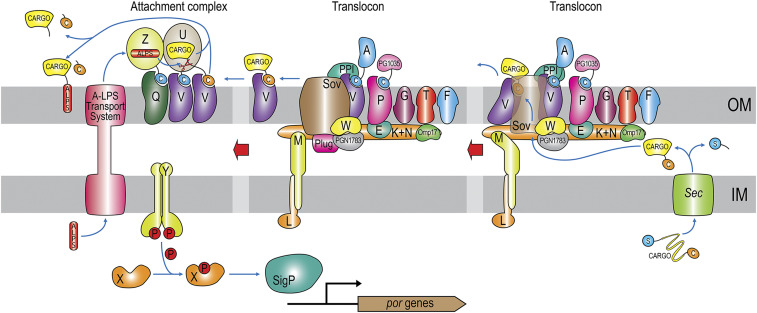

Fig. 1.

Architecture and function of the P. gingivalis T9SS. Each of the Por components (PorA, PorE–PorG, PorK–PorN, PorP, PorQ, PorT, and PorU–PorZ) is denoted by its letter. Other components are PG1035, PGN_1783, ECF SigP sigma factor, Sov, and Omp17. PPI, which is a FKBP-type peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase, and Plug were identified in the structure analysis of the Sov-ortholog SprA from F. johnsoniae (13). The respective closest matches in P. gingivalis W83 are PG0708 (UP Q7MVC1; 34% identical) and PG2092 (UP Q7MT87; 24% identical), respectively. In addition, “C” stands for the CTD (orange, cleavable; blue, noncleavable), “S” for the signal peptide for SecYEG secretion, “ALPS” for anionic lipopolysaccharide, and an encircled “P” for a phosphate group. Refer also to refs. 6, 10, 11, 13, and 57.

At present, at least 24 proteins have been identified as structural “Por” or regulatory elements of the T9SS in P. gingivalis (Fig. 1), all of which are conserved across bacterial species sharing the secretion system (6, 10, 11, 13, 27). Cytoplasmic and IM-anchored components include PorM and PorL, which energize translocation (28), as well as PorX and PorY, which regulate por gene transcription together with the SigP sigma factor (29). PorE, PorK, PorN, PorW, and Plug, as well as Omp17/PG0192/PGN_0300 and PGN_1783, are periplasmic components. Finally, PorA, PorF, PorG, PorP, PorQ, PorT, PorU, PorV, PorZ, Sov, protein PG1035, and possibly a peptidyl-proline cis/trans isomerase reside in the OM or on the surface. Information on the molecular structure is available for PorA (30), PorE (31), PorM (32), and PorZ (33), as well as PorK and PorN (34). In addition, the structures of the Sov, Plug, PorM, PorL, and PorV orthologs of Flavobacterium johnsoniae have been reported (13, 28). However, knowledge about the structures and functions of the other T9SS components is lacking.

P. gingivalis PorU is a multidomain, 1,158-residue protein that acts both as the T9SS signal peptidase and sortase-type transpeptidase (21, 23, 35). It is itself secreted by the T9SS but retains the CTD (21, 23), similarly to the A-LPS carrier PorZ (33) and to PorA (30). Indeed, PorU and PorZ associate through their CTDs with integral-membrane β-barrels PorV and PorQ, respectively, to form an “attachment complex” (Fig. 1), which regulates the activity of PorU on the OM surface (11, 36, 37). PorU contains a catalytic domain (CD) distantly related to gingipains, with a catalytic cysteine (C690; PorU residue numbers in superscript according to UniProt database [UP] entry B2RGP6; residue numbers of other proteins are in subscript). The CD is flanked by an unidentified number of domains of unknown architecture. By contrast, previously characterized sortases, which are not signal peptidases and have been described only from gram-positive bacteria, are small, single-domain β-barrel proteins (38, 39). They are grouped into six classes with a catalytic cysteine–histidine–arginine triad. They cleave substrates within a specific peptide motif and attach crossbridge peptide to the new C terminus for tethering proteins to the cell wall (39). Other sortases covalently link pilin subunits through lysine isopeptide bonds. By contrast, PorU cleaves the CTD within the upstream linker as a bona fide signal peptidase without a specific recognition sequence and attaches A-LPS to cargoes by transpeptidation (21, 23, 35). Consistent with these essential functions for transport, mutant P. gingivalis strains lacking the porU gene or expressing an inactive catalytic mutant (PorU-C690A) have a nonfunctional T9SS (21, 23, 35).

To gain insight into the architecture and function of P. gingivalis PorU, we analyzed its functional oligomerization state, solved its crystal structure, and derived plausible regulatory and functional mechanisms, which were supported by mutant studies.

Results and Discussion

Recombinant PorU Occurs as Catalytically Accessible Monomers and Occluded Dimers In Vitro.

A construct spanning the entire protein with the signal peptide replaced by an N-terminal His6-tag, hereafter rPorU, was produced by recombinant overexpression in Escherichia coli and purified through several chromatography steps. Gel filtration analysis of freshly purified protein revealed soluble dimers and monomers, in addition to soluble aggregates (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), and concentration of the monomeric fraction led to protein dimerization, as determined by multiangle laser light scattering (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B, inset). Regardless of the oligomeric state, rPorU showed no activity in vitro against a natural substrate, the zymogen of gingipain RgpB (proRgpB), even after prolonged incubation at equimolar concentration in the presence of PorZ (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), which points to additional factors necessary for activity. Moreover, this finding is consistent with only <1% of gram-positive sortase molecules isolated from the cell surface being catalytically functional for transpeptidation in vitro (39). Thus, we hypothesized that the active site should be accessible in functional oligomerization states. We used a biotinylated tripeptide chloromethylketone (Biot-F–P–R-ck), one of a class of reagents used to discriminate between active and zymogenic peptidases by covalent labeling (40), to screen the distinct oligomeric fractions. Although a background signal was detectable for all peaks, biotinylation was substantially higher only for monomeric rPorU (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B and C). Moreover, previous treatment with the nonbiotinylated form of the compound (F–P–R-ck) abolished biotin labeling of the intact monomeric rPorU and its degradation products (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D and E). In addition, the reagent was specific for rPorU as no signal was detected when using the RgpB- and Kgp-specific reagents Biot-R-ck and Biot-K-ck, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). Finally, neither the thermally denatured protein nor rPorU-C690A were labeled, i.e., they lacked accessible catalytic cysteines (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). Thus, rPorU appears to transit between dimers and monomers with occluded and accessible catalytic sites, respectively.

PorU Is Only Functional within the Attachment Complex on the P. gingivalis Surface.

In mutants of essential T9SS elements, both PorU and cargoes such as gingipains accumulate in the periplasm with intact CTDs (6, 35), which supports that periplasmic PorU is inactive. We thus assayed processing of a catalytic cysteine mutant of proRgpB, proRgpB-C449A, to its mature form as a proxy for correct PorU function. The protein was very efficiently processed by intact cells of a gingipain-null mutant (∆K/∆RAB) but not by cells expressing inactive PorU-C690A. Moreover, secretion mutant ∆porN, which retained PorU in the periplasm, was likewise unable to process proRgpB-C449A (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A), thus revealing the requirement that wild-type protein be located on the cell surface. Furthermore, to determine whether native PorU from the periplasm of T9SS mutants was enzymatically active, we incubated proRgpB-C449A cell lysates of various secretion-deficient mutants (∆sov, ∆porZ, ∆porN, and ∆porV), which included members of the attachment complex, in an experiment with the ∆K/∆RAB mutant as control. In contrast to the latter, we found no processing of proRgpB-C449A by lysates of the secretion mutants despite the presence of wild-type, full-length PorU (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 B and C). Collectively, these results support that PorU is inactive until joining the attachment complex on the cell surface.

Overall Structure of the rPorU Protomer and the N-Terminal Cluster.

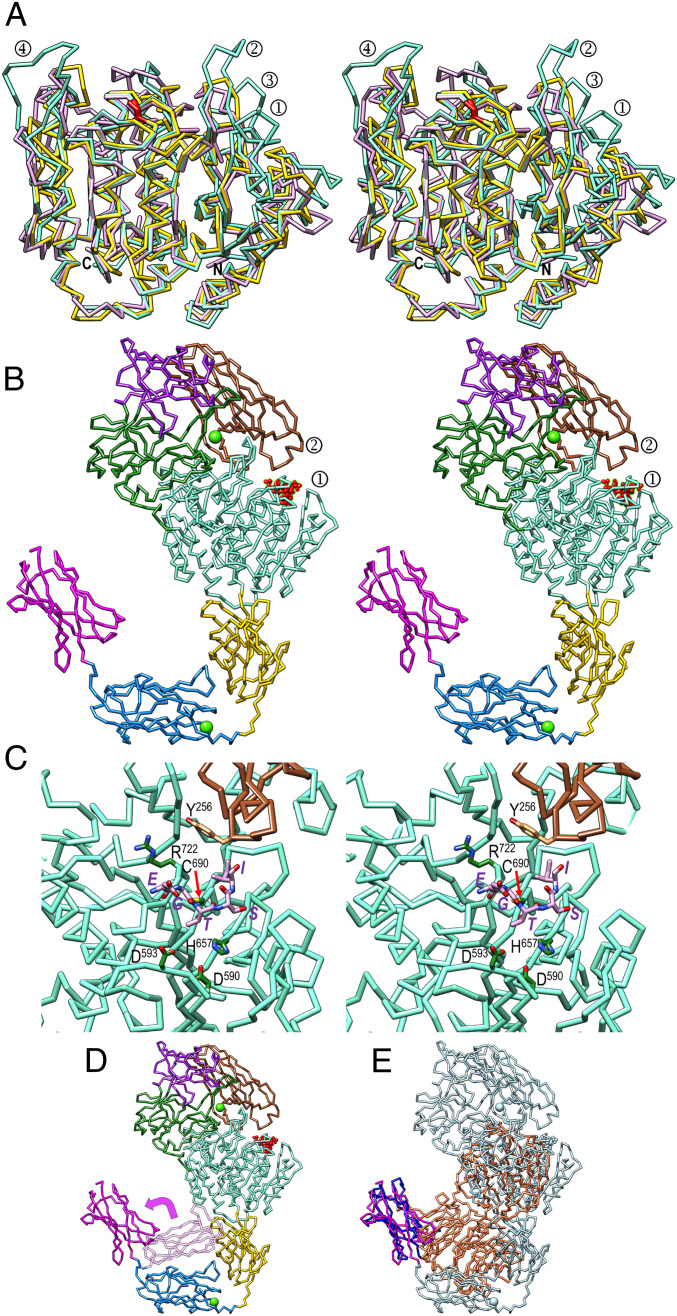

rPorU crystallized in a hexagonal space group (SI Appendix, Fig. S1G), and its structure was solved by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction of a selenomethionine-derivatized crystal, with two protomers (A and B) in the asymmetric unit, totaling 64 heavy-atom sites. The final model was refined with native diffraction data to 3.35-Å resolution, with Rfactor and free Rfactor values of 0.202 and 0.243, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S1). The rPorU molecule (Fig. 2A) has an elongated shape with maximal dimensions ∼130 Å (h) × ∼75 Å (w) × ∼65 Å (d) and consists of a CD flanked by three domains on either side (Fig. 2B).

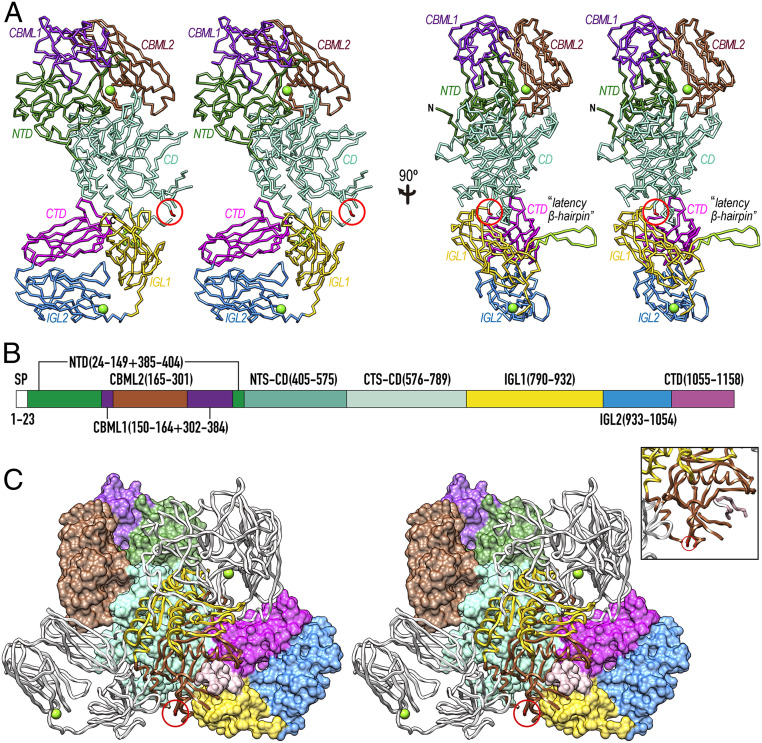

Fig. 2.

Overall structure of rPorU. (A) Two orthogonal views of the rPorU protomer, ∼130 Å in height and ∼75 Å in width (Left), as Cα plots in cross-eye stereo. The seven domains (the N-terminal NTD domain, carbohydrate-binding-module-like domains CBML1 and CBML2, the CD, immunoglobulin-like domains IGL1 and IGL2, and the C-terminal CTD domain) are colored differently and labeled. The calcium ions of CMBL2 and IGL2 are shown as green spheres, and the nonfunctional catalytic cysteine (C690) is encircled in red. The latency β-hairpin is shown in chartreuse and labeled in the Right panel. (B) Domain structure of rPorU with the residues spanning each domain colored as in A. (C) Stereo cartoon of the rPorU dimer particle, ∼105 Å high and ∼140 Å wide, with the back protomer shown for its Connolly surface and domain-colored as in A. The front protomer is depicted as a white ribbon except for the NTS-CD (in yellow) and the CTS-CD (in sienna). In the latter protomer, the nonfunctional catalytic cysteine (C690) is encircled in red and the calcium ions are displayed as green spheres. The Inset shows a close up to illustrate the inhibition of CTS-CD of the front protomer through the latency loop of the back protomer, displayed as a pink ribbon (Fig. 3G).

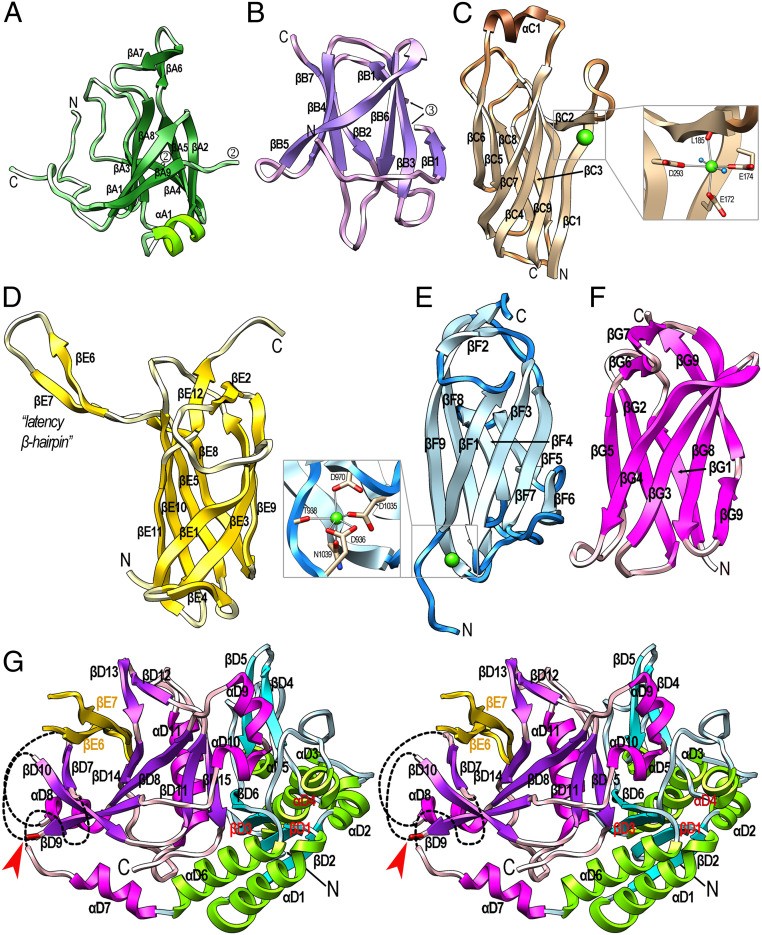

The 146-residue N-terminal domain (NTD; residues Q24–S149+Q385–E404) has a central, seven-stranded β-barrel core spanning strands βA1 through βA5, βA8, and βA9 (Fig. 3A). A β-hairpin (βA6βA7) and helix αA1 cap the barrel on the top and at the bottom, respectively. Overall, this compact domain bears no significant structural similarity with proteins of known structure. Next, carbohydrate-binding-module-like domain 1 (CBML1; Q150–Y164+D302–S384) spans 98 residues and is inserted within loop LβA8βA9 of the NTD. It is also a seven-stranded β-barrel (βB1 through βB7) but differs in connectivity (Fig. 3B). Overall, CBML1 exhibits significant structural similarity with carbohydrate-binding modules, such as those of AMP-activated protein kinase (Protein Data Bank access code [PDB] 4YEF), galectin-7 (PDB 3ZXE), and galectin-4 (PDB 4YM2). Inserted within βB1 of CBML1 is the 137-residue CBML2 domain (Y165–N301), which is a nine-stranded antiparallel β-sandwich that spans ∼50 Å along the direction of the strands (Fig. 3C). It consists of a large front sheet spanning βC7, βC4, βC9, and βC1+βC2 as the right outermost strand, which is split in two by a protruding loop (LβC1βC2) that embraces calcium-binding site 1. This site has structural relevance and keeps the loop poised for interaction with the preceding domains (see next paragraph). The calcium is octahedrally coordinated by carboxylate oxygens from E172, E174, and D293; the carbonyl oxygen of L185; and two solvent molecules (Fig. 3 C, Inset). The front sheet of CBML2 packs against a small four-stranded back sheet spanning βC6, βC5, βC8, and βC3. Like CBML1, CBML2 also resembles carbohydrate-binding modules such as a β-glucan-binding protein from Thermotoga maritima (PDB 1GUI) and a xyloglucan-binding moiety from Rhodothermus marinus (PDB 4BJ0).

Fig. 3.

Structural domains of rPorU. (A) Ribbon-type plot of the NTD colored similarly to Fig. 2B. The N and C termini are marked as are the regular secondary structural elements, β-strands βA1 through βA9, and α-helix αA1. Domains CBML1 and CBML2 are inserted within the two anchor points numbered 2. (B) Same as A for CBML1, which comprises β-strands βB1 through βB7. Domain CBML2 is inserted within the two anchor points numbered 3. (C) Domain CBML2 containing βC1 through βC9 and αC1. (Inset) A close up of calcium site 1, with the metal as a green sphere and solvents as blue spheres. (D) Domain IGL1 with strands βE1 through βE12. The latency β-hairpin LβE6βE7 is tagged. (E) Domain IGL2, which contains strands βF1 through βF9 and calcium site 2 (Inset). (F) The CTD of rPorU with strands βG1 through βG9. The last strand is interrupted by a bulge. (G) Domain CD shown in stereo with the termini labeled. The N-terminal subdomain (I405–D575) is in blue/green and comprises strands βD1 through βD6 and helices αD1 through αD6. The C-terminal subdomain (R576–L789) is in magenta/purple and contains strands βD7 through βD15 and helices αD7 through αD11. The three chain breaks of the subdomain are indicated by black dashed lines. The latency β-hairpin of the symmetric domain IGL1 is depicted in yellow (strands βE6 and βE7). They contribute with CD strands βD7, βD10, βD9, βD8, and βD14 to form a β-barrel, which is viewed down the barrel axis. The catalytic cysteine C690 is depicted as a red stick at the end of βD9 and pinpointed by a red arrow.

The NTD, CBML1, and CBML2 domains intercalate like Russian dolls (Fig. 2B) and fold on top of each other giving rise to a compact intertwined N-terminal cluster centered on the βA6βA7 β-hairpin of NTD, which protrudes ∼25 Å from the domain surface (Figs. 2A and 3A). The structural similarity of the two CBML domains with carbohydrate-binding proteins points to a putative role for this cluster in the binding of the PorU substrate A-LPS, probably in collaboration with PorZ within the attachment complex (25). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that enzymes processing complex carbohydrate polymers are often composite structures in which a CD is fused to one or more carbohydrate-binding modules (41).

The C-Terminal Cluster.

Downstream of the CD, the 143-residue immunoglobulin-like domain 1 (IGL1; P790–E932; Fig. 3D) is an antiparallel β-sandwich with a three-stranded front sheet (βE1, βE3, and βE9) and a four-stranded back sheet (βE11, βE10, βE5, and βE8). The most remarkable element of IGL1 is a large β-hairpin (βE6βE7; residues K850–Y868), hereafter called the “latency β-hairpin,” which laterally projects ∼30 Å away from the domain surface and has a pivotal regulatory function (see The Latency β-Hairpin Is an Essential Regulator of PorU Function). Overall, the domain core is structurally reminiscent of immunoglobulin-like domains present in an adhesin from Marinomonas primoryensis (PDB 4KDV) and a putative superoxide dismutase from T. maritima (PDB 2AMU). IGL1 is followed by the 122-residue domain IGL2 (V933–A1054), which is also a compact antiparallel β-sandwich, but it consists of four-stranded front (βF1, βF3, βF7, and βF6) and back β-sheets (βF9, βF8, βF4, and βF5) (Fig. 3E). At the bottom of the sandwich, calcium-binding site 2 is formed by oxygens from D936, T938, D970, D1035, and N1039 (Fig. 3 E, Inset). Like IGL1, IGL2 is also structurally related to immunoglobulin-like domains such as myosin-binding protein C (PDB 6G2T). Finally, the 104-residue CTD (P1055–Q1158) is a seven-stranded antiparallel β-sandwich with a four-stranded front sheet (βG4, βG3, βG8, and βG9) and a three-stranded back sheet (βG5, βG2, and βG) (Fig. 3F). Overall, the rPorU CTD is also an immunoglobulin-like domain, reminiscent of Fab fragments from antibodies such as 10C9 (PDB 2Z91), and it shares overall architecture and topology, but few other features, with the reported CTDs of RgpB, PorZ, and a 35-kDa heme-binding protein (16, 33, 42).

Akin to the first three domains, the last three moieties also form a structural unit of β-domains as a ring-shaped C-terminal cluster (Fig. 2A). The long axes of the sandwiches are rotated by ∼70° (IGL1–IGL2) and ∼160° (IGL2–CTD) along the direction of the polypeptide, so that the surface of the front sheet of IGL2 faces the back sheet of the CTD. Moreover, the top edge of the CTD contacts the outer surface of the back sheet of IGL2. Remarkably, the three domains share a seven-stranded β-sandwich core architecture, both in direction and connectivity of the strands.

The CD.

Inserted between NTD and IGL1, the 385-residue CD (I405–L789) consists of an N-terminal (NTS-CD; I405–D575) and a C-terminal (CTS-CD; R576–L789) subdomain (Figs. 2B and 3G). The former is an α/β/α-sandwich with a central parallel four-stranded β-sheet (βD6, βD3, βD1, and βD2) pinched between parallel helices αD1 and αD6 at the bottom, as well as αD5 plus perpendicular helices αD2 and αD3 on the top. This subdomain interacts laterally with the N-terminal cluster (Fig. 2A and Overall Structure of the rPorU Protomer and the N-Terminal Cluster), further supporting a role for the latter in substrate presentation to the CD. At R576, the chain enters the CTS-CD, which features a seven-stranded β-barrel. Two of the strands are provided by the latency β-hairpin of IGL1 of the symmetry-related protomer (see The C-Terminal Cluster), which results in a barrel spanning strands βD7, βD10, βD9, βD8, βD14, βE7, and βE6 (Fig. 3G). The barrel is decorated with two helices (αD7 and αD11) and β-ribbon βD11βD15. In addition, helix αD8 caps the barrel in the back and helices αD9 and αD10 protrude from the barrel in the front.

Dimeric rPorU Is in a Latent Conformation.

rPorU protomers A and B associate through C2 symmetry to form a compact intertwined dimeric particle with overall dimensions ∼105 Å (h) × ∼140 Å (w) × ∼105 Å (d) through an interaction surface of 3,268 Å2 (Fig. 2C). This large surface has a theoretical solvation, free-energy gain upon interface formation of −37.6 kcal/mol and a complexation significance score of 0.62, which indicate that it is unlikely the result of crystal packing artifacts (43). The interface is quasi-symmetric and involves 100 and 104 residues from molecules A and B, respectively.

It has been proposed that in addition to contributing to the attachment complex, PorV also shuttles cargoes across the translocation pore traversing the OM by binding their CTDs (Fig. 1 and refs. 13 and 37). For this to happen, the CTDs must be accessible for interaction, as observed in the structures of PorZ (PDB 5M11) (33) and HBP35 (PDB 5YLA) (42), which are both monomeric. Specifically, the CTD sandwich edges containing the respective C termini, which correspond to the top edge of the rPorU CTD in Fig. 3F, are surface-exposed in these structures. By contrast, in the rPorU dimer, the CTDs are buried (Fig. 2C). With respect to the CD, PorU was predicted to contain a gingipain-type cysteine peptidase module with C690 as the catalytic residue (21). However, comparison with Kgp and RgpB revealed that there is no functional active-site cleft in rPorU and that the catalytic cysteine is at the end of β-strand βD9, just preceding a 15-residue disordered loop segment (Fig. 3G). Two more flexible regions of 18 and 27 residues within LβD7αD8 and LαD7βD7, respectively, are present on the left side of the subdomain. Thus, rPorU is in an incompetent, latent conformation incapable of both translocation and catalysis in both protomers of the dimer, due to the crossed insertion of the symmetric latency β-hairpins (Fig. 2C). This finding would explain our failure to generate aptamers with the ability to interfere with PorU activity and thus block T9SS function (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

The Latency β-Hairpin Is an Essential Regulator of PorU Function.

We hypothesized that latent dimers might represent a regulatory mechanism to account for the aforementioned PorU inactivity in the periplasm, which may be unlatched once the protein is translocated to the OM surface. In this case, the latency β-hairpin would be an essential element for T9SS function. We used the aforementioned cellular approach with P. gingivalis strains expressing mutants of PorU with a C-terminal His8-tag (PorUHis) for better protein detection (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Fig. 4). We monitored strain growth and the presence of PorUHis on the cell surface by flow cytometry, as well as gingipain processing, secretion, and activity, as previously reported (8, 44–46). Indeed, gingipain activity results in the black pigmentation characteristic of wild-type strains (33).

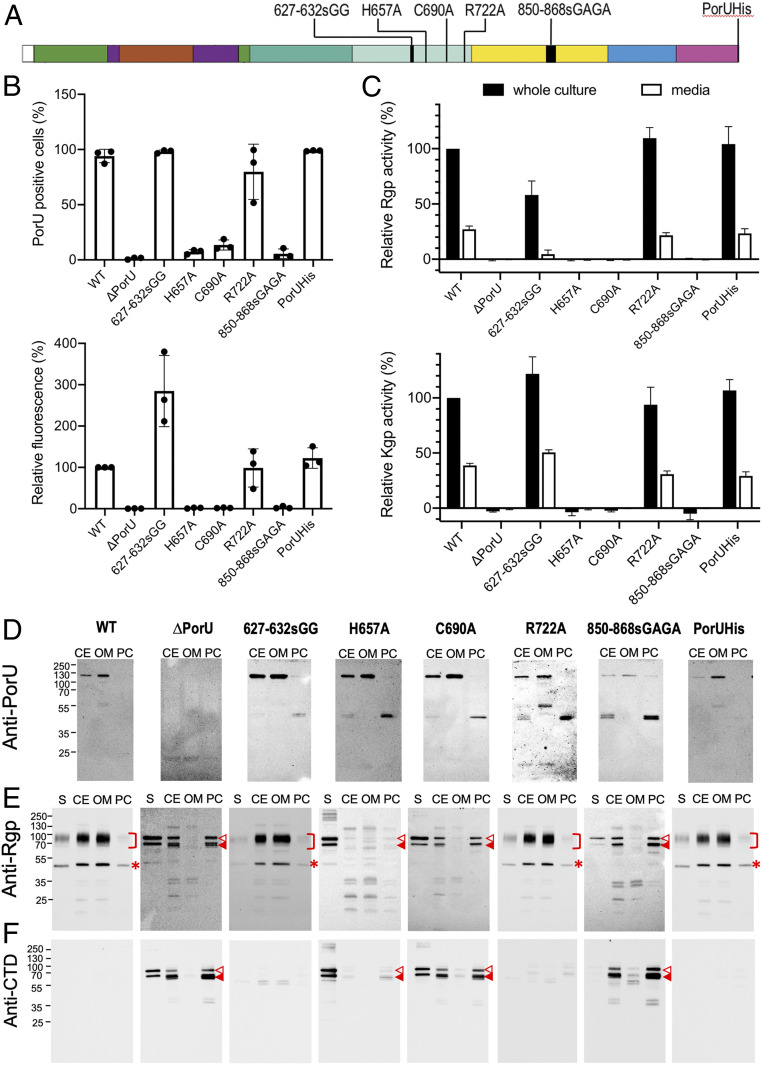

Fig. 4.

In vivo functional studies of PorU mutant strains. (A) Scheme depicting the localization along the sequence of the six PorUHis variants assayed, with domains colored as in Fig. 2B. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of the presence of PorUHis variants on the P. gingivalis surface as the percentage of PorU-positive bacterial cells (Top) and relative fluorescence analysis of the signal (Bottom) with respect to the wild-type parental P. gingivalis W83 strain normally producing PorUHis (100%) and the ΔporU knockout (0%). Dots depict the individual measurements (n = 3, mean ± SD). (C) Rgp (Top) and Kgp (Bottom) activity (n = 3, mean ± SD) in whole cultures and cell-free conditioned medium. Gingipain activity in whole cultures of wild-type P. gingivalis was taken as 100%. (D) Western blotting analysis of PorUHis variants in supernatants (S), cell extracts (CE), the OM fraction (OM), and the periplasmic/cytoplasmic fraction (PC). (E) Same as D for RgpB. Square parentheses pinpoint membrane-type RgpB; open triangles indicate unprocessed, full-length 80-kDa proRgpB with intact N-terminal prodomain and CTD; full triangles designate N-terminally truncated proRgpB; and asterisks highlight the RgpB CD. Absence of gingipain activity results from deficient proteolytic processing of the respective zymogens, which require the entire prodomain to be removed and degraded to release activity (35). (F) Same as E for the CTD of RgpB.

We analyzed a mutant in which the latency β-hairpin was replaced with the tetrapeptide G–A–G–A (mutant PorU-850–868sGAGA) to prevent dimerization. Given that this structural element protrudes from the domain surface and does not perform intramolecular contacts (Fig. 3D), its ablation should not impair proper folding, i.e., phenotypes would not result from misfolded protein artifacts. Indeed, recombinant PorU-850–868sGAGA migrated as a monomer that did not dimerize during protein concentration (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The modified wild-type strain W83, which produces functional PorUHis, and the deletion strain ∆porU were used as positive and negative controls, respectively (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). In fact, the PorU-850–868sGAGA strain was viable and reached similar levels of biomass to the control though through a longer generation time (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). By contrast, PorUHis was predominantly detected as an aberrant 50-kDa cleavage fragment retained in the periplasm according to Western blotting analysis (Fig. 4D). A small fraction of intact PorUHis was found associated with the OM (Fig. 4D) but absent from the cell surface according to flow cytometry (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the mutant displayed no gingipain activity (Fig. 4C) due to accumulation of their zymogens in the periplasm (Fig. 4 E and F), and it lacked pigmentation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Together, these results indicate that PorU-850–868sGAGA was not translocated across the OM owing to T9SS dysfunction. Thus, the latency β-hairpin, which causes protein dimerization, is essential for regulation and translocation of PorU and other T9SS cargoes.

A Model for Active Monomeric PorU.

Given that PorU transits between catalytically accessible monomers and occluded dimers of latent structure in vitro and that all T9SS cargoes reported to date are monomeric (7), we hypothesized that active PorU on the OM would likewise be monomeric and contain a functional CD and an accessible CTD. Thus, we attempted to obtain crystals of the monomer, but all trials with wild-type protein and variants with ablated latency β-hairpin failed, as did extensive efforts to produce and crystallize shorter fragments of PorU. Thus, we produced a comparative model for full-length competent PorU (Fig. 5 A–E). First, we performed automatic homology modeling of the CD using a threading approach that produces high-quality models even based on remote templates (47). These calculations identified RgpB as the closest structural relative despite sequence identity of only 11% (refer to legend for Fig. 5A) and produced a high-confidence model with a fold, active site, and substrate-binding cleft that are similar to competent gingipains (48–51). Comparison of this model with the CD of the experimental dimeric structure revealed that NTS-CD and the final segment of CTS-CD (T751–L789) closely matched except for some loops, which supports the accuracy of the structure prediction. By contrast, the intermediate part of CTS-CD (R576–R750) largely deviated owing to the intrusion of the symmetric latency β-hairpin and other interactions within the dimer.

Fig. 5.

Comparative model of active monomeric PorU. (A) Superposition of the Cα traces in stereo of the CDs of P. gingivalis Kgp (plum, PDB 6I9A) (50) and RgpB (gold, PDB 4IEF) (49) onto the CD of the PorU homology model (aquamarine). The structure-based sequence identities between the CDs of PorU and Kgp or RgpB are 12% and 11%, respectively. The catalytic cysteines of Kgp, RgpB, and PorU are C477, C473, and C690, respectively. They overlap in the structures and are shown with their side chains as red sticks. The four most divergent loops in PorU surrounding the active site are numbered 1 (loop LβD3αD4), 2 (LβD4βD5), 3 (LαD5βD6), and 4 (LβD7αD8). Refer also to Fig. 3G. (B) Comparative model of full-length monomeric active PorU in stereo in the orientation of the latent reference (Fig. 2A) and same coloring. Only the CTS-CD and the position and orientation of the CTD diverge from the reference. A substrate is shown in red stick representation pinched between CTS-CD loop LβD7αD8 (numbered 1) and CMBL2 loop LβC6βC7 (numbered 2). (C) Close-up view of the active site and the substrate, with residues labeled in purple and carbons colored plum. Selected residues of the CD as a Cα trace in aquamarine (C690, H657, D590, D593, and R722) and of CBML2 as a Cα trace in sienna (Y256) are shown with side-chain carbons colored green and orange, respectively, and labeled in black. (D) Rearrangement of the CTD in the homology model entails an outward 90° rotation. (E) Superposition of the CTDs of PorZ (CTD in dark blue, upstream moiety in orange) and the PorU homology model (CTD in magenta, upstream moiety in light blue).

Second, we assembled and energy-minimized a model for full-length PorU that retained the overall architecture of the N-terminal cluster, NTS-CD, the final segment of CTS-CD, IGL1, and IGL2 of the experimental structure. The intermediate part of CTS-CD was taken from the homology model. This model contained four protruding loops surrounding the active site (LβD3αD4, LβD4βD5, LαD5βD6, and LβD7αD8; Fig. 5A). To validate the general architecture of this model, we analyzed the importance of LβD7αD8 in P. gingivalis cells by replacing I627–H632 with two glycines (mutant PorU-627–632sGG) following the strategy described in The Latency β-Hairpin Is an Essential Regulator of PorU Function. Given the exposed nature of this loop, its omission should not have major consequences for protein folding if the model were correct but be deleterious if it were not. Remarkably, PorU-627–632sGG was associated with the OM (Fig. 4D), and about three times more abundant on the P. gingivalis surface than was the wild-type protein (Fig. 4B) and fully functional, as confirmed by the black colony pigmentation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). Moreover, gingipain processing, activity, and localization were indistinguishable from the control strain (Fig. 4 C, E, and F). Notably, the higher abundancy of PorU-627–632sGG was not due to increased gene expression of this mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) but either enhanced messenger RNA or protein stability or superior translocation efficiency.

Third, the CTD was rotated outward by ∼90° about residue G1052 (Fig. 5D) to become accessible for a potential PorV interaction and adopt a position relative to the upstream domains similar to that found in PorZ (Fig. 5E), which is presumably in a competent conformation for translocation (33). Finally, we modeled a pentapeptide of sequence E-G-T–S-I (Fig. 5C), which is the RgpB sequence recognized and cleaved by PorU (21, 23), based on the coordinates of the complex between Kgp and a peptidomimetic inhibitor (52). Accordingly, this substrate would nestle between protruding loop LβD7αD8 and the long LβC6βC7 overhang loop on the top edge of the CMBL2 sandwich (see Overall Structure of the rPorU Protomer and the N-Terminal Cluster and Fig. 3C).

Remarkably, the model of active PorU was not compatible with the dimeric structure of latent rPorU due to clashes with the symmetry mate. These occurred among CTS-CDs, between a CTS-CD and its symmetric latency β-hairpin, and between protruding loop LβD7αD8 and its symmetric IGL1 and CTD domains. Thus, these structural studies further imply that active PorU is most probably monomeric.

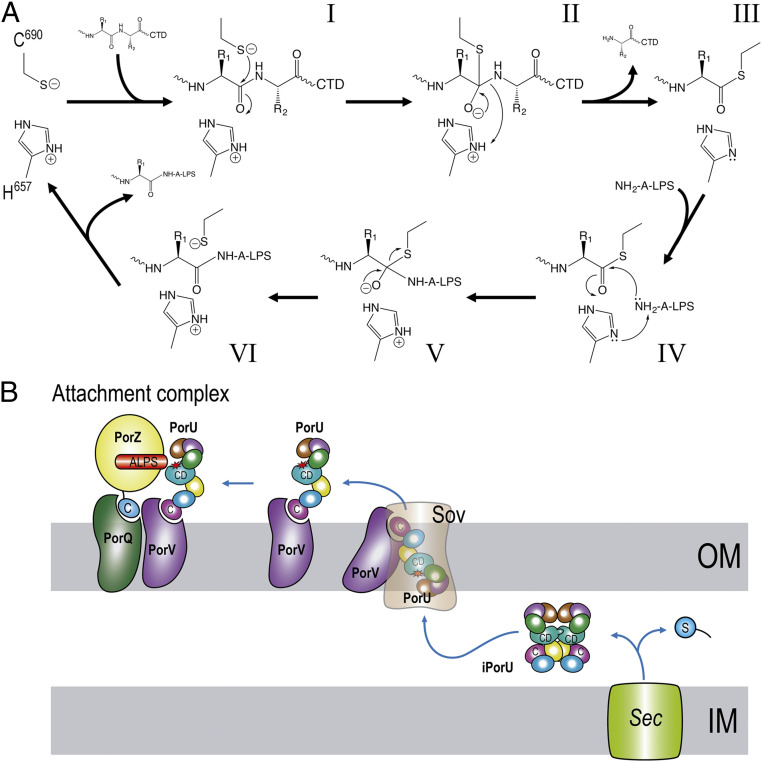

Analysis of the CD Model of Active PorU and Proposed Catalytic Mechanism.

Superposition of the active CD model of PorU on the CDs of RgpB (PDB 4IEF) and Kgp (PDB 6I9A) revealed extensive structural similarity (Fig. 5A). Specifically, key residues of RgpB for substrate binding or catalysis (16, 48) are in equivalent positions: C473/H657/E381 are replaced with C690/H657/D590 or D593 in PorU. The S1’ pocket (substrate and active-site subsite nomenclature according to refs. 53 and 54) of the latter would be smaller than in RgpB, which is consistent with the disparate substrate specificity: while RgpB has a strict preference for arginines in P1, PorU has a discrete preference for polar/acidic residues and small residues in P1 and P1’, respectively (21–23). Moreover, we identified R722 close to catalytic C690. This residue is absent from RgpB and Kgp but is reminiscent of R197 and R233 of Staphylococcus aureus sortases A and B, respectively, which are part of the respective catalytic triads of these enzymes (39).

We next generated and analyzed mutant strains of the three hypothetical elements of a possible catalytic triad, PorU-C690A, PorU-H657A, and PorU-R722A. We found that the first mutant was not functional and characterized by white colonies (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C), absence of the protein from the cell surface (Fig. 4B), accumulation of unprocessed proRgpB in the periplasm (Fig. 4 E and F), and lack of gingipain activity (Fig. 4B), in accordance with C690 acting as the primary catalytic nucleophile (21). Remarkably, the phenotype of PorU-H657A was very similar to that of PorU-C690A (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5), which thus pinpointed the histidine as a previously unidentified catalytic residue. By contrast, PorU-R722A was indistinguishable from the parental strain, which strongly argues against a role for R722 in the transpeptidation reaction catalyzed by PorU, in contrast to gram-positive sortases (39).

Thus, in the proposed catalytic mechanism (Fig. 6A), C690 is assisted by H657 acting as a general base to enhance the nucleophilicity of the cysteine sulfur and generate a thiolate–imidazolium ion pair. The nucleophilic sulfur attacks the carbonyl oxygen of the substrate residue in P1, giving rise to a tetrahedral thioacyl intermediate with the upstream cleavage fragment, while releasing the downstream CTD according to the signal–peptidase function. At this point, H657 acts as an acid and donates a proton to the leaving amine nitrogen. The covalent thioacyl intermediate is resolved through attack of the thioacyl carbonyl by a nucleophile, from which H657 captures a proton to enhance reactivity. Nucleophiles may be a water molecule, amino acids, or peptides present in the medium for those cargo molecules to be released. By contrast, cargoes to be fastened to the OM would be resolved by one of the terminal amines of the phosphoetanolamine moieties of the inner-core oligosaccharide of A-LPS (25) (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Proposed operating modus of PorU. (A) The enzyme likely operates according to a two-step ping-pong mechanism comprising an endopeptidolytic cleavage reaction to remove the CTD (steps I through III) followed by transpeptidation with A-LPS acting as nucleophile (steps IV through VI) for cargoes targeted for insertion into the OM. The nucleophilic group is likely an amine from a phosphoethanolamine group attached to the inner core oligosaccharide of A-LPS (refer also to ref. 25). For secretory cargoes released into the medium, NH2-A-LPS is replaced by other nucleophiles including a water molecule, amines, amino acids, or short peptides. (B) Regulation of PorU activity in the cell involves removal of the signal peptide (blue circle labeled “S”) after Sec translocation to the periplasmic space in which the protein would fold and adopt an inactive dimeric structure (iPorU). Thereafter, conformational rearrangement, hypothetically through interaction with PorV and the Sov translocon, would lead to a monomer (PorU) with a competent CD and a PorV-accessible CTD (labeled “C”) for the transit across the OM. Finally, functional PorU associated with PorV would join PorZ and PorQ in the attachment complex, ready for catalysis, with PorZ presenting A-LPS (25) as one of the two substrates for transpeptidation (refer also to A and Fig. 1). The rest of the T9SS components have been omitted for clarity.

Corollary.

The T9SS of P. gingivalis is strictly dependent on PorU, a seven-domain, gingipain-like cysteine hydrolase with a CTD that, uniquely for bacterial secretion systems, simultaneously acts as a signal peptidase and sortase with transpeptidase functions. PorU is the first signal peptidase shown to cleave a signal that is at the C terminus, is not a peptide but a protein domain, and is not sequence driven. Regarding the sortase function, it has previously been described in depth for gram-positive sortases only (39), which are transpeptidases unrelated to PorU and gingipains. Herein, we revealed that PorU shares a C690/H657 catalytic dyad with sortases but lacks the characteristic arginine that engages in catalytic intermediate stabilization and fixation of the threonine of a strictly conserved recognition motif within substrates (39). As PorU performs its transpeptidase reaction without a particular sequence specificity (21, 23, 35), it is conceivable that an analog of this arginine is not required here for the sortase function.

Recombinant rPorU transits between monomers and dimers with accessible and occluded catalytic sites, respectively, in solution, and the crystal structure of the dimer revealed that the protomers have three β-barrel/sandwich domains upstream and downstream of the CD, respectively. Dimers are in a latent conformation, because the C-terminal half of the respective CDs are disrupted by symmetric cross-insertion of the latency β-hairpins. This insertion gives rise to a canonical β-barrel, an ordered structure that facilitates a regulated intermolecular mechanism of crossover latency to prevent untimely T9SS activity of PorU. Indeed, ablation of the hairpin yields a bacterial strain with a nonfunctional T9SS in vivo, which confirms its relevance. Thus, simple unlatching of the β-hairpin, hypothetically through interactions with PorV during translocation (Fig. 6B), might generate a competent gingipain-like CD and yield monomeric PorU, which would be the functional species in the attachment complex. This is supported by all reported T9SS cargoes being monomeric (7). Functionally, latent dimeric PorU would be the species present in the periplasm while active monomeric PorU would only be found as part of the attachment complex on the cell surface.

Materials and Methods

The Extended Experimental Procedures are provided in SI Appendix. Briefly, genomic modification of P. gingivalis was performed by homologous recombination with suicide plasmids derived from a master plasmid, which was subjected to mutagenesis with the site-directed, ligase-independent mutagenesis methodology (55). Subcellular fractionation of P. gingivalis cells, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE, and Western blotting analyses were performed according to standard laboratory approaches. Proteolytic activity of gingipains Kgp and RgpA/B in the extracellular milieu was assayed as previously described (56). Recombinant PorU with an N-terminal hexahistidine-tag was produced through heterologous overexpression in E. coli and purified following standard procedures of protein biochemistry. Flow cytometry studies, as well as labeling of PorU and multiangle laser light scattering after size-exclusion chromatography, followed reported protocols. The complex was crystallized by sitting-drop vapor diffusion and solved by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction using a selenomethionine derivative. A homology model of the competent CD of PorU was obtained by bioinformatics approaches based on gingipains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Laura Company, Xandra Kreplin, and Joan Pous from the joint Molecular Biology Institute of Barcelona/Institute for Research in Biomedicine Automated Crystallography Platform and the Protein Purification Service for assistance during purification, crystallization, and SEC-multiple-angle laser light scattering following size-exclusion chromatography experiments. We further would like to thank the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility and ALBA synchrotrons for beamtime and the beamline staff for assistance during diffraction data collection. This study was supported in part by grants from Polish (Narodowe Centrum Nauki and Ministry of Science and Higher Education), US (NIH/National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research), Spanish, and Catalan public and private bodies (grant/fellowship references PID2019-107725RG-I00, 2012/04/A/NZ1/00051, 2014/15/D/NZ6/02546, 2015/19/N/NZ1/00322, 1306/MOB/IV/2015/0, DE 022597, 2017SGR3, and Fundació “La Marató de TV3” 201815). The open-access publication of this article was funded by the BioS Priority Area under the program “Excellence Initiative - Research University” at the Jagiellonian University of Kraków (Poland).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. G.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2103573118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Protein coordinate data have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (6ZA2). The homology model of active monomeric PorU is provided in the supplementary information.

References

- 1.Dewhirst F. E., et al., The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5002–5017 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajishengallis G., Darveau R. P., Curtis M. A., The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 717–725 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonetti M. S., Van Dyke T. E.; Working Group 1 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop , Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Periodontol. 84, S24–S29 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominy S. S., et al., Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green E. R., Mecsas J., Bacterial secretion systems: An overview. Microbiol. Spectr. 4, 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0012-2015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasica A. M., Ksiazek M., Madej M., Potempa J., The type IX secretion system (T9SS): Highlights and recent insights into its structure and function. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 215 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christie P. J., The rich tapestry of bacterial protein translocation systems. Protein J. 38, 389–408 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato K., et al., A protein secretion system linked to bacteroidete gliding motility and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 276–281 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulas T., et al., Structure and mechanism of a bacterial host-protein citrullinating virulence factor, Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase. Sci. Rep. 5, 11969 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakayama K., Porphyromonas gingivalis and related bacteria: From colonial pigmentation to the type IX secretion system and gliding motility. J. Periodontal Res. 50, 1–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veith P. D., Glew M. D., Gorasia D. G., Reynolds E. C., Type IX secretion: The generation of bacterial cell surface coatings involved in virulence, gliding motility and the degradation of complex biopolymers. Mol. Microbiol. 106, 35–53 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride M. J., Bacteroidetes gliding motility and the type IX secretion system. Microbiol. Spectr. 7, PSIB-0002-2018 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauber F., Deme J. C., Lea S. M., Berks B. C., Type 9 secretion system structures reveal a new protein transport mechanism. Nature 564, 77–82 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hočevar K., Potempa J., Turk B., Host cell-surface proteins as substrates of gingipains, the main proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biol. Chem. 399, 1353–1361 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Righolt A. J., Jevdjevic M., Marcenes W., Listl S., Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. J. Dent. Res. 97, 501–507 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Diego I., et al., The outer-membrane export signal of Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion system (T9SS) is a conserved C-terminal β-sandwich domain. Sci. Rep. 6, 23123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seers C. A., et al., The RgpB C-terminal domain has a role in attachment of RgpB to the outer membrane and belongs to a novel C-terminal-domain family found in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6376–6386 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoji M., et al., Por secretion system-dependent secretion and glycosylation of Porphyromonas gingivalis hemin-binding protein 35. PLoS One 6, e21372 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shoji M., et al., Identification of genes encoding glycosyltransferases involved in lipopolysaccharide synthesis in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 33, 68–80 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis M. A., et al., Variable carbohydrate modifications to the catalytic chains of the RgpA and RgpB proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect. Immun. 67, 3816–3823 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glew M. D., et al., PG0026 is the C-terminal signal peptidase of a novel secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24605–24617 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veith P. D., et al., Protein substrates of a novel secretion system are numerous in the Bacteroidetes phylum and have in common a cleavable C-terminal secretion signal, extensive post-translational modification, and cell-surface attachment. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4449–4461 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorasia D. G., et al., Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion substrates are cleaved and modified by a sortase-like mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005152 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veith P. D., et al., Type IX secretion system cargo proteins are glycosylated at the C terminus with a novel linking sugar of the Wbp/Vim pathway. MBio 11, e01497–e01420 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madej M., et al., PorZ, an essential component of the type IX secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis, delivers anionic lipopolysaccharide to the PorU sortase for transpeptidase processing of T9SS cargo proteins. MBio 12, e02262-20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y. Y., et al., The outer membrane protein LptO is essential for the O-deacylation of LPS and the co-ordinated secretion and attachment of A-LPS and CTD proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 1380–1401 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorasia D. G., et al., In situ structure and organisation of the type IX secretion system. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2020). 10.1101/2020.05.13.094771. [DOI]

- 28.Hennell James R., et al., Structure and mechanism of the proton-driven motor that powers type 9 secretion and gliding motility. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 221–233 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadowaki T., et al., A two-component system regulates gene expression of the type IX secretion component proteins via an ECF sigma factor. Sci. Rep. 6, 23288 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yukitake H., et al., PorA, a conserved C-terminal domain-containing protein, impacts the PorXY-SigP signaling of the type IX secretion system. Sci. Rep. 10, 21109 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trinh N. T. T., et al., Crystal structure of Type IX secretion system PorE C-terminal domain from Porphyromonas gingivalis in complex with a peptidoglycan fragment. Sci. Rep. 10, 7384 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leone P., et al., Type IX secretion system PorM and gliding machinery GldM form arches spanning the periplasmic space. Nat. Commun. 9, 429 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lasica A. M., et al., Structural and functional probing of PorZ, an essential bacterial surface component of the type-IX secretion system of human oral-microbiomic Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 6, 37708 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorasia D. G., et al., Structural insights into the PorK and PorN components of the Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005820 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veillard F., et al., Proteolytic processing and activation of gingipain zymogens secreted by T9SS of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biochimie 166, 161–172 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saiki K., Konishi K., Porphyromonas gingivalis C-terminal signal peptidase PG0026 and HagA interact with outer membrane protein PG27/LptO. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 29, 32–44 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glew M. D., et al., PorV is an outer membrane shuttle protein for the type IX secretion system. Sci. Rep. 7, 8790 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazmanian S. K., Liu G., Ton-That H., Schneewind O., Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science 285, 760–763 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobitz A. W., Kattke M. D., Wereszczynski J., Clubb R. T., Sortase transpeptidases: Structural biology and catalytic mechanism. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 109, 223–264 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams E. B., Krishnaswamy S., Mann K. G., Zymogen/enzyme discrimination using peptide chloromethyl ketones. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 7536–7545 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boraston A. B., et al., Differential oligosaccharide recognition by evolutionarily-related β-1,4 and β-1,3 glucan-binding modules. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 1143–1156 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato K., et al., Immunoglobulin-like domains of the cargo proteins are essential for protein stability during secretion by the type IX secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 110, 64–81 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krissinel E., Henrick K., Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishiguro I., Saiki K., Konishi K., PG27 is a novel membrane protein essential for a Porphyromonas gingivalis protease secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292, 261–267 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saiki K., Konishi K., The role of Sov protein in the secretion of gingipain protease virulence factors of Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 302, 166–174 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato K., et al., Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis proteins secreted by the Por secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 338, 68–76 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Källberg M., et al., Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1511–1522 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eichinger A., et al., Crystal structure of gingipain R: An Arg-specific bacterial cysteine proteinase with a caspase-like fold. EMBO J. 18, 5453–5462 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Diego I., et al., Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence factor gingipain RgpB shows a unique zymogenic mechanism for cysteine peptidases. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 14287–14296 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Diego I., et al., Structure and mechanism of cysteine peptidase gingipain K (Kgp), a major virulence factor of Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontitis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 32291–32302 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorman M. A., et al., Structure of the lysine specific protease Kgp from Porphyromonas gingivalis, a target for improved oral health. Protein Sci. 24, 162–166 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guevara T., et al., Structural determinants of inhibition of Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipain K by KYT-36, a potent, selective, and bioavailable peptidase inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 9, 4935 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schechter I., Berger A., On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27, 157–162 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomis-Rüth F. X., Botelho T. O., Bode W., A standard orientation for metallopeptidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1824, 157–163 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chiu J., March P. E., Lee R., Tillett D., Site-directed, ligase-independent mutagenesis (SLIM): A single-tube methodology approaching 100% efficiency in 4 h. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e174 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veillard F., et al., Purification and characterisation of recombinant His-tagged RgpB gingipain from Porphymonas gingivalis. Biol. Chem. 396, 377–384 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorasia D. G., Veith P. D., Reynolds E. C., The type IX secretion system: Advances in structure, function and organisation. Microorganisms 8, 1173 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Protein coordinate data have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (6ZA2). The homology model of active monomeric PorU is provided in the supplementary information.