Significance

The modulation of the rate of formation and of the lifetime of transcription initiation complexes is a critical point in gene expression control. In Escherichia coli, single-nucleotide changes can change the half-life of an RNA polymerase (RNAP)–promoter DNA complex by more than an order of magnitude. The origins of these effects are poorly understood. Using cryoelectron microscopy, we find that small alterations in the sequence or size of the transcription bubble trigger global changes in RNAP–DNA interactions and in DNA base stacking. Our results reveal that nonadditive structural changes allow a few crucial DNA positions to tune the transcription initiation complex lifetime from seconds to hours, influencing the rate and efficiency of the initial steps of RNA synthesis.

Keywords: transcription, RNA polymerase, cryo-EM, open complex, promoter DNA

Abstract

The first step in gene expression in all organisms requires opening the DNA duplex to expose one strand for templated RNA synthesis. In Escherichia coli, promoter DNA sequence fundamentally determines how fast the RNA polymerase (RNAP) forms “open” complexes (RPo), whether RPo persists for seconds or hours, and how quickly RNAP transitions from initiation to elongation. These rates control promoter strength in vivo, but their structural origins remain largely unknown. Here, we use cryoelectron microscopy to determine the structures of RPo formed de novo at three promoters with widely differing lifetimes at 37 °C: λPR (t1/2 ∼10 h), T7A1 (t1/2 ∼4 min), and a point mutant in λPR (λPR-5C) (t1/2 ∼2 h). Two distinct RPo conformers are populated at λPR, likely representing productive and unproductive forms of RPo observed in solution studies. We find that changes in the sequence and length of DNA in the transcription bubble just upstream of the start site (+1) globally alter the network of DNA–RNAP interactions, base stacking, and strand order in the single-stranded DNA of the transcription bubble; these differences propagate beyond the bubble to upstream and downstream DNA. After expanding the transcription bubble by one base (T7A1), the nontemplate strand “scrunches” inside the active site cleft; the template strand bulges outside the cleft at the upstream edge of the bubble. The structures illustrate how limited sequence changes trigger global alterations in the transcription bubble that modulate the RPo lifetime and affect the subsequent steps of the transcription cycle.

The transcription by DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RNAPs) releases information stored in duplex DNA in the form of RNA transcripts. Appropriate responses to changing cellular conditions and growth rates require rapid and tight control of cellular RNA levels. In the model organism Escherichia coli, the rate of productive initiation events largely determines RNA transcript amount (1). RNA chain initiation frequencies vary over four orders of magnitude in vivo; during exponential growth, 103 to 104 ribosomal transcripts are synthesized per generation, whereas other transcripts may appear once or not at all (1–3). The intensive investigations of how E. coli achieves this extraordinary range are ongoing, recently revealing new modes of transcription initiation (4) and termination (5, 6), despite decades of study.

In bacteria, a single “core” enzyme (E), comprising five subunits (α2ββ’ω), catalyzes all templated phosphodiester bond synthesis. Operon-specific output is orchestrated by the addition of a sixth dissociable subunit sigma (σ), forming the holoenzyme (Eσ) (3, 7). The vast majority of studies have focused on the “housekeeping” group I σ factors [σ70 in Eco; σA in other bacteria (8)]. Regions of high-sequence conservation in the σ70 family (numbered sequentially 1.1 to 4.2) correspond to structural domains linked by flexible linkers (9, 10), each playing distinct roles in promoter DNA recognition and strand separation (3).

Exposing and positioning the start site (+1) near the RNAP catalytic Mg2+ in the RNAP open promoter complex (RPo) requires the unwinding of over a turn of the DNA helix (11). Because binding-free energy drives these steps, promoter DNA sequence intrinsically determines how quickly RPo forms and how long it persists (1, 12–14). These kinetic differences critically underlie cell function. For example, differences in RPo lifetime allow the RNAP-binding factors dksA and ppGpp to “discriminate” between the operons they regulate and those they do not and to have opposing effects at those they do (15, 16).

A striking discovery of ensemble and single-molecule, mechanistic investigations is that RPo is not a singular universal complex; multiple forms of RPo can exist at the same promoter (see for example refs. 17–22). At the model phage promoter λPR, a series of distinct open complexes form after the rate-limiting step [I1 to I2 (21, 22)]:

[1]

[1]

Eq. 1 is the minimal mechanism of RPo formation at λPR. Steps that contribute to the observed dissociation rate constant are shown in red (11, 21). I2 is only transiently populated; conversions to I3 and RPo successively stabilize the strand-separated state. The structural and functional differences between these complexes are largely unknown.

While the conserved −35 and −10 elements and the length of the “spacer” between them affect RPo formation and thus its overall stability, both the sequence and length of the “discriminator” [Fig. 1A (16)] has emerged as a primary determinant of RPo lifetime (23–25). Haugen et al. (23) demonstrated that the critical sequence runs from −6 to −4 (numbering with respect to the transcription start site at +1), with 5′-GGG-3′ (nontemplate strand [nt-strand] sequence) yielding the longest RPo half-lives (t1/2) (23). The cornerstone of “discrimination” was pinpointed to −5 on the nt-strand, in which the presence of G [G-5(nt)] increases RPo t1/2 by 10- to 50-fold at the rrnB P1, λPR, λPL, and Pgal promoters. Cross-linking, mutational, and other biochemical approaches mapped these large effects on RPo stability to specific interactions with σ70-conserved region 1.2 (σ701.2) (26, 27). The subsequent work found that the β “gate loop” (βGL) also plays a crucial role in nt-strand discriminator interactions (28). How do these interactions dictate RPo lifetimes that range from seconds to many hours?

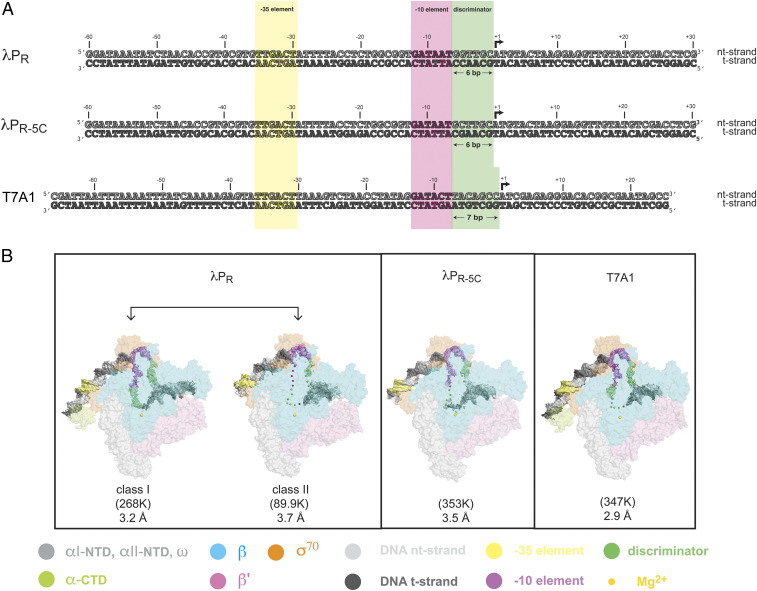

Fig. 1.

Promoter DNA constructs used for cryo-EM studies and overall cryo-EM structures of RPos. (A) Promoter sequences studied by cryo-EM (nt-strand DNA [Top strand], light gray and t-strand [Bottom strand], dark gray). Numbers above the DNA sequences denote positions with respect to the transcription start site (+1, black arrow). Shaded colors highlight key promoter regions: −35 element (yellow), −10 element (magenta), and the discriminator (pale green; bp, base pair). (Top) λPR (−60 to +30: −60 to +20 are native λPR sequences; sequences downstream of +20 originate from the plasmid construct used in extensive kinetic and DNA footprinting studies of λPR (11)). (Middle) λPR-5C (−60 to +30) is a single base pair inversion of λPR G-5 to C. (Bottom) T7A1 (−66 to +20). While T7A1 and λPR share the same −35 element sequence, key differences exist in both the −10 element and the sequence and length (seven versus six nucleotides, respectively) of the discriminator. At the upstream end of the constructs used here, the T7A1 promoter has both proximal and distal UP elements (tight-binding αCTD binding sites), and λPR (and λPR-5C) has a distal UP (3). (B) Eco RNAP subunits are shown as transparent surfaces [αI-NTD, αII-NTD, and ω: light gray (NTD, N-terminal domain); αCTD: pale green; β: pale cyan; β’: light pink; and σ70: light orange], with the active site Mg2+ shown as a sphere (pale yellow). Promoter DNA is shown as the cryo-EM difference density (−35 element, −10 element, and discriminator colored as in A). Particle classification revealed two distinct RNAP-DNA complexes populated at λPR and a single class at T7A1 and at λPR-5C. The number of particles in each class and nominal resolution are shown. In λPR class I, good map density allowed all bases in the nt- and t-strands to be modeled. For comparison, disordered bases in the other RPo are shown as spheres positioned approximately at the corresponding position of the phosphate backbone in λPR class I. Outside of the transcription bubble, duplex DNA was modeled from −45 to +23 in λPR class I, −37 to +13 in λPR class II, −37 to +15 in λPR-5C, and −47 to +15 in T7A1.

The understanding of how the transcription bubble is differentially stabilized is currently limited. The first atomic resolution structures of RPo, determined by X-ray crystallography, used promoters with consensus −35 and −10 promoter elements and preformed bubble templates with short regions of downstream duplex (29, 30) or short downstream “fork” constructs (31, 32). Resulting structures often revealed strand disorder; to improve resolution, NTPs or short RNA primers were added, forming transcription initiation complexes (RPinit). Until very recently (33–36), the structure of RPo was mostly inferred from these RPinits formed at nonnative sequences/structures.

Similarly, detailed biochemical studies of RPo formation exist for only a small handful of promoters. Mechanistic and biochemical investigations of DNA opening at two phage promoters (λPR and T7A1) have largely defined the critical steps in forming the transcription bubble (see for example refs. 11, 14, 37–39). However, no high-resolution structural data exist for any complex formed at either promoter. Here, we begin to address these gaps by using cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize RPo formed de novo at λPR and T7A1. We also studied a single-point mutant in λPR (λPR-5C) that significantly decreases RPo half-life. The observed structural differences between these complexes provide insights into how changes in promoter sequence, even at a single base, give rise to orders of magnitude changes in RPo lifetimes.

Results

Cryo-EM Structures of Eσ70 RPo at the λPR, λPR-5C, and T7A1 Promoters.

To understand how promoter sequence dictates widely differing RPo lifetimes, we analyzed three de novo DNA-melted Eσ70–promoter complexes by single-particle cryo-EM (T7A1, λPR, and a point mutant at −5 in λPR [λPR-5C; Fig. 1A]). To reduce particle orientation bias at the liquid–air interface, the cryo-EM buffer contained 8 mM CHAPSO (40). CHAPSO decreases RPo lifetime (two- to threefold) but does not change the relative stabilities of each RPo (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). The steps of maximum likelihood classification (41) revealed two distinct conformational classes populated at λPR (75% of the particles fall into class I and 25% in class II), whereas only a single class was found for T7A1 and λPR-5C (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S8 and Table S2).

All complexes exhibit the following similarities: 1) the transcription bubble is fully open and 2) interactions with the −35 element, the spacer region, and the −10 element bases on the nt-strand are largely the same. Because these interfaces do not significantly differ from each other or from previously reported structures (see for example refs. 10, 29–31, 34, 42), they will not be discussed further.

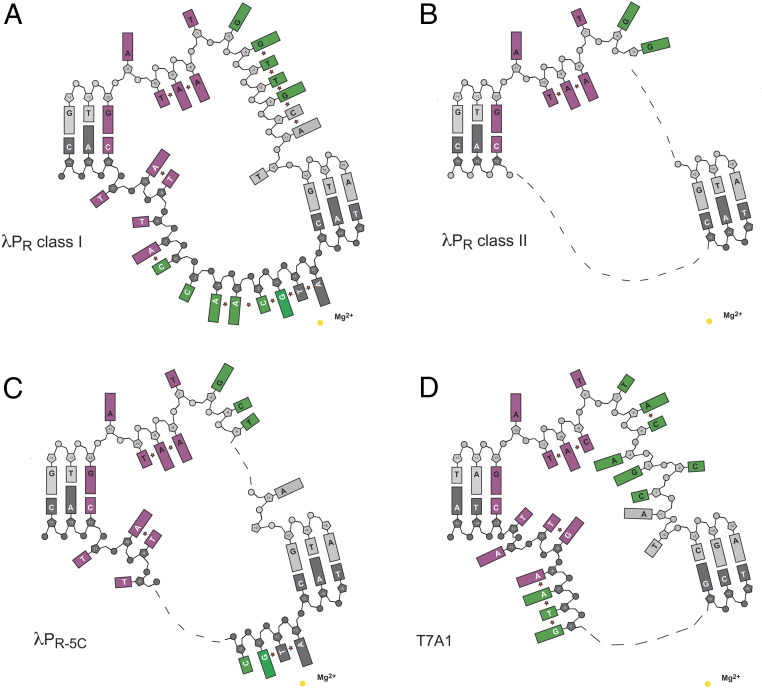

Relative to λPR class I, the DNA strands in transcription bubbles of the other RPo are more dynamic. Every single base in the nt- and t-strands within the transcription bubble is well resolved in λPR class I (Figs. 1B and 2A), whereas the entire t-strand (−11 to +2) and −4 to +2 on the nt-strand have little to no map density in class II (Figs. 1B and 2B). Similarly, the midregions of the λPR-5C bubble (Figs. 1B and 2C) and the T7A1 t-strand from −4 to +2 (Figs. 1B and 2D) could not be modeled.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of differences in base stacking in the transcription bubble. The schematic illustrates the following: 1) the position of bases in each open complex, with missing bases shown as dashes and 2) base stacking pairs indicated by a star symbol. DNA backbone and bases colored as in Fig. 1. (A) λPR class I. (B) λPR class II. (C) λPR-5C. (D) T7A1.

Duplex DNA regions distant from the transcription bubble also exhibit distinct differences. Unlike the relatively unstable RPos (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1), an additional, helical turn could be modeled downstream of +13 (to +23) in λPR class I. Upstream of the −35 element, map density for the two flexibly tethered alpha C-terminal domains (αCTDs) bound to DNA (−38 to −55) exists for all RPo, but only the “proximal” αCTD in λPR class I and in T7A1 was well resolved (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S8, respectively; see also refs. 43 and 44). “Distal” αCTD (UP) sequences exist at both promoters (3), prompting a focused classification of this region. This approach extracted classes with different DNA trajectories but not distinct bound states of the second αCTD [see also ref. 35]. Thus, despite the presence of UP elements in these promoters and in the ribosomal promoters rpsT P2 and rrnB P1, by the time RPo has formed, the DNA upstream of −45 is dynamic and the DNA-binding mode of the second αCTD is heterogeneous (34–36, 45).

The superposition of the cryo-EM RPo structures here and published, high-resolution cryo-EM RPo complexes [rpsT P2 (34) and rrnB P1 (36)] revealed small to moderate differences in the conformation of the clamp and the β-lobe (SI Appendix, Table S3). With respect to λPR class I, the clamp and the β-lobe are more open in all other RPo. Additional narrowing of the cleft in λPR class I appears to be stabilized by the partial ordering of five σ70 residues (σ70S85 to S89; SI Appendix, Fig. S9) on the β-lobe. Extension across the β-lobe creates a “clasp” between β’ and β, similar to that observed in mycobacterial EσA (33); the clasp must be undone for DNA to leave the cleft.

σ70S85 to S89 lie at the C terminus of the 37-residue linker connecting σ701.2 to σ701.1 [σ701.1 linker (46)]. During RPo formation, DNA displaces σ701.1 bound in the cleft (35, 47). No density exists for σ701.1 in any RPo structure to date, indicating it does not rebind elsewhere. Instead, ejection creates a high local concentration of the flexibly tethered σ701.1 above the cleft. Interactions between the linker and the β-lobe may increase stability in the λPR class I by directing σ701.1 away from the channel, effectively reducing its concentration near the downstream DNA and disfavoring its reentry relative to other RPo (see SI Appendix for a discussion of relationship of class I and class II to the intermediates in Eq. 1).

Differences in Base Stacking in the Transcription Bubble.

To illustrate the differences in strand/base resolution and in the extent of base stacking, each transcription bubble is presented schematically in Fig. 2. At the upstream end, the nt-strand single-stranded −10 element hexamer exhibits the same conserved interactions seen in all RPo structures to date: A-11(nt) and T-7(nt) are flipped out into protein pockets on σ, the intervening bases from −10 to −8 stack with each other, facing into the channel with only the backbone atoms making interactions with σ. However, downstream of the −10 element, differences in the discriminator length and sequence impact both single-stranded base stacking and strand order. For λPR class I, almost every base in the bubble (nt- and t-strands) has a stacking partner (Fig. 2A). The single-base change from G to C (nt-strand) at −5 of λPR-5C affects the entire bubble, disordering regions of both strands (Fig. 2C). The addition of an additional nucleotide to the discriminator (T7A1) and placing an A at the same position as G-5(nt) in λPR [A-6(nt) T7A1 numbering] disrupts all base stacking interactions in the nt-strand downstream of −5 (Fig. 2D).

Interactions with the nt-Strand: Structural Consequences of Base Identity at −5 and of a Seven-Base Versus Six-Base Discriminator.

How do three nt-strand bases, out of all the bases that define a promoter, profoundly effect RPo lifetime (23)? DNA opening positions bases from −6 to −4 near highly conserved residues in σ701.2, σ702 (9, 10) and the opposing βGL [cf (31, 48, 49)]. These interactions close off the top of the active site channel, effectively trapping the strand-separated DNA inside (SI Appendix, Figs. S3C, S4C, S6C, and S8C). As detailed in the following sections, changes away from guanine (G) and increasing discriminator length significantly reduce the extent of these contacts, resulting in global changes in RPo structure.

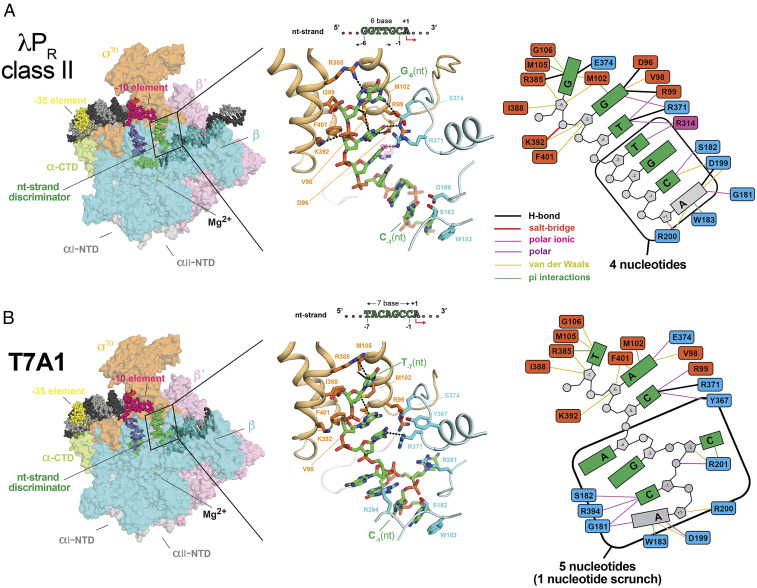

At λPR, base stacking and pairing interactions from −6 to −4 in the duplex DNA are replaced in RPo by an extensive network of polar, π, and van der Waals contacts with highly conserved Eσ70 residues (Fig. 3A). Notably, σ70M102, σ70R99, and βR371 interact with multiple bases in λPR class I RPo but not in T7A1 (Fig. 3B) or λPR-5C (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). The “keystone” G-5(nt) (23) is tightly held by distinct chemical interactions that include two base-specific hydrogen bonds [σ70R99(NE)-O6 and σ70D96(OD2)-N1; Fig. 3A]. Replacing λPR G-5(nt) with C not only eliminates these local contacts but abolishes the complex set of interactions that constrain the bases and sugar phosphate backbone from −6 to −4 in λPR (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). The quality and quantity of interactions in the T7A1 nt-strand interface are diminished as well (Fig. 3B). Because Eσ70 intimately reads out the bases at −6 to −4 (Fig. 3A), deviations from the optimal sequence (G) as well as length alter the interface cooperatively. As a result, the driving force for the isomerizations that stabilize RPo changes nonadditively with sequence. These energetic differences result in widespread changes in RPo structure (the extent of strand and downstream DNA order, clamp/β-lobe/σ701.1-linker positions; Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Figs. S10 and S11 and Table S3) and thus differences in RPo lifetime.

Fig. 3.

Differences in Eσ70 interactions with the nt-strand discriminator region between λPR class II (A) (six-base discriminator) and T7A1 (B) (seven-base discriminator). (Left) Overall view of RPo (similar to Fig. 1B with the same color scheme and abbreviations), with RNAP subunits shown in the surface representation and DNA as atomic spheres. The boxed area is magnified in the middle. (Middle) Magnified view showing the interactions with the nt-strand from the discriminator to +1. RNAP subunits are shown in the backbone worm (β: pale cyan; β’: light pink; and σ70: light orange); the sidechains of atoms within 4.5 Å nucleic acid atoms (λPR [−6 to +1] or T7A1 [−7 to +1]) are shown as sticks. Atomic distances within 3.5 Å and interactions with the π electrons of the DNA bases (sulfur-π and cation-π) are shown by black dashed lines. The DNA carbon atoms are colored green. (Right) Schematic comparing the network of interactions between the nt-discriminator (and +1) and Eσ70. Favorable interactions within 3.5 Å (hydrogen bonds and salt bridges) are shown by heavier lines (see color key) than those within 4.5 Å (polar, ionic, van der Waals, and π [sulfur, cation, and π]). The corresponding cryo-EM density is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S10. Although the nature and extent of interactions with the nt-strand discriminator differ between λPR and T7A1, the DNA backbone is largely solvent exposed. Few favorable interactions exist with the sugar atoms (at upstream and downstream ends of the discriminator region), and only one positively charged amino acid falls within 4.5 Å the DNA phosphate backbone of either promoter.

One key similarity unites all RPo characterized to date: The majority of the nt-strand discriminator contacts are with the upstream and downstream ends, leaving the midregion fairly unconstrained and indeed observed to be dynamic in λPR-5C and in λPR class II. As seen in T7A1, adding another base to the canonical six-base discriminator is accommodated by unstacking and flipping bases out of the backbone, relative to one another in the “middle” of the discriminator (Fig. 3B). In this “scrunch,” A-4(nt) and G-3(nt) face the upstream end of the RNAP channel and are solvent-accessible; C-2(nt) occupies the downstream end of the channel where it interacts with βR201.

DNA Scrunches in the t-Strand at the Upstream End of the DNA Channel in RPo.

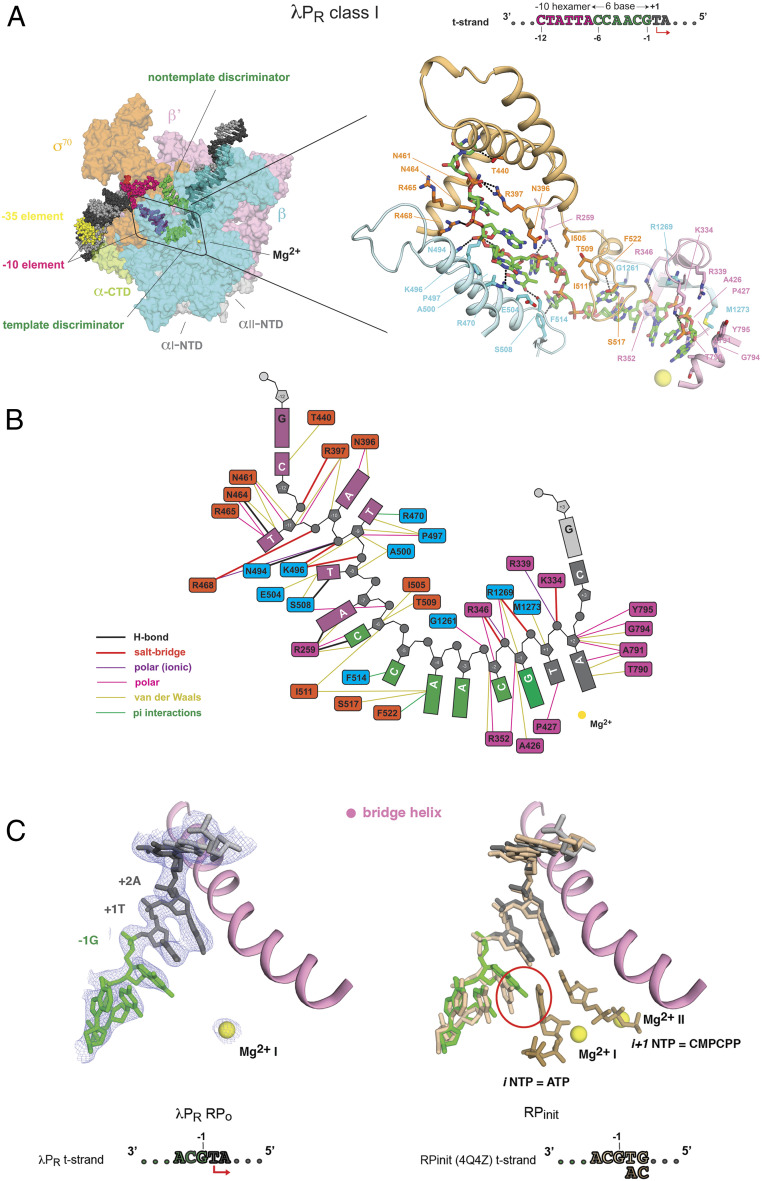

Entry of the t-strand into the active site channel at T-11(t) [T-12(t) in T7A1] distorts the DNA backbone, unstacking and flipping T-11(t) out at λPR and both T-12(t) and A-11(t) at T7A1, placing the t-strand scrunch at the upstream end of the channel (Fig. 4). While map density exists for these bases in locally filtered maps, it is weaker than that for the corresponding base partners on the nt-stand, consistent with the accessibility of these conserved thymines to permanganate ions (20, 50). As the strand descends further into the cleft, both λPR and T7A1 exhibit an intriguing interaction with the single-stranded −10 element t-strand at A-10(t)/T-9(t) or T-10(t)/G-9(t), respectively. In both RPo, these bases are stacked and captured by the loop between the α-helices formed by σ702.1 and σ702.2 and the opposing residues on the β-protrusion (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). At the upstream end of this “sandwich,” σ70R397 and σ70N396 interact with the −10 base; the −10 phosphate oxygen makes polar ionic contacts with σ70R468 (σ703 helix). At the downstream end, the −9 base and βR470 form a cation–π stacking interaction and βK496 makes both ionic and nonpolar interactions with the DNA backbone (Fig. 4). Whether the sandwich causes the scrunch or whether it helps stabilize the scrunch is unknown. However, placing the additional base (relative to six-base discriminator) at the upstream end of the channel equalizes the length of the t-strand from −8 to the active site (see Discussion).

Fig. 4.

Scrunching in the t-strand. (A) λPR class I RPo flips out T-11(t) at the ds/ss junction. (B) T7A1 flips out two bases, T-12(t) and A-11(t), scrunching the t-strand at the upstream entrance to the active site channel. Residues within 4.5 Å nucleic acid atoms of the t-strand are shown as sticks. Eco Eσ70 subunits shown in backbone worm (β: pale cyan; β’: light pink; and σ70: light orange). Single-stranded bases from −11 to −9 (A; λPR) or −12 to −9 (B; T7A1) are shown as sticks (same color coding as Fig. 3) and also transparent atomic spheres (hot pink). The same σ and β residues stabilize the A-10(t)/T-9(t) or T-10(t)/G-9(t) stacking pairs in λPR and T7A1, respectively, noted and shown as transparent CPK atoms (σ: orange and β: cyan). The corresponding cryo-EM density is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S12.

λPR t-Strand Is Largely Stacked and Tightly Held in the Active Site Channel.

The relatively high resolution of all the transcription bubble bases of the λPR class I RPo and of the residues in the active site channel allows a molecular visualization of the interactions that direct the t-strand from the double-stranded/single-stranded (ds/ss) upstream fork to the Mg2+ active site on the “floor” of the cleft some 65 Å away. As illustrated in the stick/cartoon representation (Fig. 5A) and schematic (Fig. 5B), every base in the upstream half of the bubble makes multiple, favorable interactions with at least one residue of σ70, β, and/or β’. While flipped out of the helix at the ds/ss junction, T-11(t) is not captured in a protein pocket like its base-pairing partner on the nt-strand. Nonetheless, σ70 appears to constrain its position via numerous interactions with the base and backbone atoms: 1) polar contacts between thymine and a trio of residues in the σ703 helix, including an H-bond between σ70N461 and N3; 2) salt bridges between the phosphate oxygens of C-12(t) and T-11(t) and σ70R397 and σ70R468, respectively; and 3) multiple polar and nonpolar contacts with sugar atoms. With the exception of σ70N461, these residues are invariant or nearly invariant in the housekeeping σ factors. Multiple interactions form between Eσ70, the bases, and the sugar phosphate backbone from −11 to −6, including H-bonds with T-11(t), A-7(t), and C-6(t). As seen for the nt-strand, π interactions form with unstacked bases at T-9(t) (βR470), C-5(t) (σ70F514), and A-4(t) (σ70F522).

Fig. 5.

λPR class I t-strand interactions and positioning in the active site. (A, Left) Overall representation of RPo (same color scheme and abbreviations) as in Fig. 3. The boxed area is magnified to the right. (B) Schematic detailing the interactions between the t-strand and residues within 4.5 Å. (C) Comparison of the t-strand in λPR class I RPo and in RPinit. (Left) Cryo-EM density (blue mesh) defining the modeled position of single-strand bases on the t-strand (−3 to +2), the downstream ss/ds junction at +3 (shown as sticks), and the Mg2+ bound in the RPo active site (yellow sphere). The conserved RNAP bridge helix (β’: pink) is shown as a point of reference. Colors are the same as in Fig. 1. (Right) Result of aligning λPR class I RPo with a high-resolution X-ray structure of RPinit [2.9-Å resolution and PDB 4Q4Z (32)]. Initiating triphosphate ribonucleotides (dark beige) bound at +1 (iNTP = ATP) and +2 (i+1NTP = CMPCPP) pair with the corresponding t-strand bases. The backbone and bases from −3 to +3 in RPinit (beige) largely superpose with the equivalent positions in λPR, with the exception of G-1(t) in which a change in base tilt leads to a clash (red circle) with the iNTP (ATP).

Perhaps surprisingly, no positively (or negatively) charged groups fall within 4.5 Å (nor within 6 Å) of the phosphate oxygens from T-8(t) to C-3(t). By contrast, all interactions with the t-strand DNA near the active site (−2 to +2) are with the DNA backbone [with the exception of σ70P427 N near O2 of T+1(t)]; salt bridges to each of the phosphate oxygens at −2, −1, and +1 constrain the orientation of the bases with respect to the active site Mg2+, leaving the bases free for pairing with substrate.

λPR Class I May Be an Unproductive RPo.

The relatively high resolution of the t-strand in the λPR class I complex (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S12A and Table S2) obtained in the absence of NTPs led us to examine whether the observed order corresponds to a site that is preorganized to bind the first two initiating NTPs. To address this question, we took advantage of the high-resolution X-ray structure [2.9 Å, Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 4Q4Z (32)] of an initiation complex (RPinit) between Thermus thermophilus EσA at a downstream fork promoter construct, with the same t-strand sequence from −3 to +1 as λPR, and the first two initiating NTPs. In RPinit, the +1 and +2 t-strand bases pair with the initiating nucleotide (iNTP = ATP) and a nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analog of the i+1NTP (CMPCPP), respectively. Despite differences between the two RNAPs, the DNA constructs used to form RPo and the methods used (X-ray and cryo-EM), the t-strand from −3 to +3 largely superposes (Fig. 5C), reflecting the evolutionary conservation of this site in multisubunit RNAP (48, 49). While the path of the DNA backbone and the plane of the bases at all positions are strikingly similar, G-1(t) is a notable exception. In RPinit, G-1(t) forms an interstrand stack with the iNTP (32). However, the base tilt of G-1(t) in λPR differs. Modeling predicts that G-1(t) would clash with the incoming iNTP, suggesting that this form of RPo at λPR may be recalcitrant to iNTP binding. This structural result is in complete agreement with the recent finding that the most stable open complex at λPR (RPo) must undergo a conformational change to bind the first two nucleotides (51).

Discussion

Our results illuminate the structural strategies that Eco RNAP uses to stabilize the transcription bubble and reveal how small differences in DNA sequence and/or discriminator length globally alter RPo structure. Because the next steps of NTP addition largely disrupt these contacts, their quality and extent impacts how quickly and efficiently RNAP breaks its promoter interactions as it converts to a processive elongation complex (52). Promoter escape is a complex function of DNA sequence and other extrinsic variables (see ref. 52 and references therein and refs. 13, 53–56). However, in general, initiation from promoters that form highly stable RPo is often rate limited at escape, whereas unstable RPo are limited at the steps of DNA binding and opening (see for example refs. 13, 52). As a consequence, unstable RPo (e.g., rrnb P1 and T7A1) typically produce full-length (FL) transcripts with few abortive products (57, 58) in single-round assays. By contrast, highly stable RPo (e.g., λPR) produce smaller amounts of FL products, while continuing to synthesize short RNAs (25, 52, 57, 59, 60).

At all promoters, the initiation of RNA synthesis drives the translocation of the nascent RNA/DNA hybrid and the further unwinding of the downstream duplex DNA. Because Eσ70 maintains its interactions with the upstream ds/ss fork junction, the transcription bubble progressively enlarges with each NTP addition, a process termed “scrunching” (61–63). Given the volume constraints of the active site cleft, the cost of DNA unwinding and compaction during initiation was proposed to create “stressed” intermediates and that an accumulation of stress could drive promoter escape (25, 52, 56, 64).

Based on the structures described here, the structural barriers to initially scrunching the nt-strand seem low, as few or no contacts are made from −3 to −1 in either λPR or T7A1 (Fig. 3). At other promoters, the map density for DNA in this region is poor [λPR-5C (Fig. 2); rrnB P1 (36); and rspT P2 (34)], indicating structural heterogeneity. We note that reducing interactions with the nt-strand discriminator region in RPo appears to favor a state in which regions of both strands in the bubble are dynamic (18, 19). The T7A1 RPo structure suggests that the first translocation step on a six-base discriminator promoter extends the nt-strand downstream of −4 into the channel without steric opposition; the subsequent steps are proposed to extrude the nt-strand out between the β-protrusion and β-lobe (65). While midregion contacts are minimal on the t-strand compared to those upstream (Fig. 5 A and B), the growing RNA–DNA hybrid pushes the t-strand further into the upstream end of the cleft (65). The t-strand sandwich at −10/−9 observed for λPR and T7A1 (Fig. 4) and rrnB P1 RPo (36) may provide an additional constraint that helps direct the bulge, as scrunching in the t-strand is proposed to disrupt regions (β’-lid and the σ-finger) that block RNA entry into its exit channel (65).

Proposed Structural Differences between Productive and Moribund RPo.

Seminal work by Shimamoto, Hsu, Chamberlin, and colleagues discovered that two forms of RPo can be populated at a given promoter: one that ultimately escapes to make FL RNA and one stuck in iterative rounds of abortive cycling (59, 60, 66). The latter “moribund” complex often backtracks (3′-OH RNA no longer correctly positioned in the active site), forming a dead-end complex in the absence of Gre factors (52). The relative amounts of these functionally distinct complexes are promoter sequence dependent (52, 57, 60). One of the striking implications of these studies is that core promoter sequence fundamentally sets the degree to which the initiation branches before NTP binding (see ref. 52 and references therein). Functionally, branching allows the additional regulation of transcriptional output, independent of the rate-limiting step of initiation (59), and is modulated by the Gre factors in vivo (see for example ref. 67).

While the structural basis of the moribund complex has been unknown, the unambiguous finding of two distinct cryo-EM classes at λPR but not at T7A1 or at λPR-5C may provide an answer. Based on studies of λPR by Shimamoto and colleagues (59, 67) and by the Record Laboratory (21, 22, 51), we propose that class I and class II represent unproductive (RPo) and productive (I3) forms of the open complex (Eq. 1). Multiple lines of evidence support this interpretation. Use of solutes and temperature to probe the conformational changes that occur after DNA opening at λPR indicate that RPo is stabilized relative to I3 by the “tightening” of the RNAP clamp via interactions involving mobile downstream elements [β’-jaw, sequence insertions Si1 and Si3 (48, 49)] and downstream DNA (11, 68–71); the deletion of either the β’-jaw or DNA downstream of +12 was proposed to prevent the conversion of I3 to RPo (68). Most recently, a mechanistic analysis of the steps of initiation at λPR led Record and coworkers to propose the following: 1) RPo must isomerize to bind the first two initiating NTPs and 2) I3 is the productive initiating complex (51). Because the cryo-EM λPR structures agree with these results and inferred, structural proposals, the simplest interpretation is that class I represents RPo and class II is I3 (see SI Appendix for further discussion).

At λPR, increasing i[NTP] increases the number of abortive products by ∼20-fold but does not drive synthesis of more FL products (59). Studies of initiation at other promoters found that the relative increase in abortive transcripts with [NTP] was greatest for the shortest RNAs (2 to 4 mers) (72). To explain these data, Hsu, Chamberlin, and coworkers hypothesized that the conformation of the catalytic site was somehow impaired in unproductive open complexes, resulting in a lower iNTP affinity (66). Based on this work and the observation that the production of abortive products at λPR persists long after the synthesis of FL transcripts ceases (25, 51, 59), we hypothesize that iNTP binding drives a change in base tilt at −1, converting class I (Fig. 5C) into a conformer which can initiate transcription but cannot escape the promoter. In this form of RPo, upstream movement of the nascent 2-mer hybrid and DNA unwinding/unpairing/unstacking at +3 (and any subsequent translocation step) are likely strongly disfavored because they require disrupting numerous interactions (described in Results) that do not exist in I3. When extension and translocation are slow, relatively unstable short hybrids dissociate. RNA release then restarts the abortive cycle by RPo. Because only abortives continue to increase with time in bulk single-round assays, the rate of binding iNTPs to RPo appears to be faster than the rate of RPo conversion back to the productive I3.

Implications of this Study for the Regulation of Transcription Initiation.

Stable transcription bubble formation requires establishing RNAP/DNA interactions that disfavor reannealing, rewinding, and DNA dissociation. Promoter sequence intrinsically dictates the cost of disrupting base stacking and base pairing and the degree to which unfavorable, conformational changes are driven by forming favorable protein interactions. Perhaps not surprisingly, in the most stable RPo studied here (λPR), bases on the separated strands are largely stacked (Fig. 2A) and DNA (both base and the phosphate backbone) interactions with Eσ70 appear to be maximized relative to the faster dissociating RPo (λPR-5C and T7A1). What is more remarkable is how the sequence and length of the nt-strand discriminator impact the overall RPo structure. In particular, the promoter-dependent degrees of disorder of the strands, in the bubble described here, presumably not only affect RPo lifetime but also start site selection and promoter escape.

The recent cryo-EM study of the steps of DNA opening at the rpsT P2 promoter revealed that bubble formation is not a simple progression in strand unwinding and base unstacking: DNA disruptions are dynamic and protein–DNA interactions form and unform (35). Chen et al. found that DNA entry into the active site channel is facilitated by unpairing and unstacking the DNA base pair at −12, which then repairs and restacks with −13 in the subsequent intermediate. In addition, T-9(t) binds in a pocket on the β-protrusion at an intermediate step but then leaves the pocket in subsequent intermediates and RPo (35).

Based on these observations and the comparison between λPR class I and II (Fig. 2 A and B), we highlight what may have not been fully appreciated before this structural work: In a multistep mechanism (e.g., Eq. 1), if base restacking occurs, it provides an enthalpic driving force for conformational rearrangements in that step, even if the overall net cost to RPo is zero. For example, if unwinding the upstream bubble partially (or fully) unstacks bases in the −10 hexamer [e.g., T-10(nt)/A-9(nt)/A-8(nt) and/or T-9(t)] as part of entry into the cleft, the cost is reflected in a slower forward rate or faster back rate (depending on whether unstacking occurs before or after the transition state), relative to no disruption. Restacking in a later step will then have the opposite effect on the forward and back rates, respectively. If this scenario is applicable, we note that unstacking purines is more costly than unstacking pyrimidines, suggesting that the base sequence may play hidden roles in the individual steps of DNA opening and in the subsequent steps of promoter escape.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions of Eσ70 purification, assembly of Eσ70–promoter DNA complexes, specimen preparation for cryo-EM, cryo-EM data acquisition and processing, model building and refinement, and abortive initiation transcription assays are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E.A. Campbell, M. Lilic, and members of the Darst–Campbell Laboratory for experimental advice and helpful discussions and the reviewers for their careful evaluation and valuable comments. R.M.S. thanks M. T. Record Jr. and former members of the Record lab for many fruitful collaborations and T.M. Lohman and D. Jensen for stimulating conversations and encouragement. We are grateful to R. Landick, R. L. Gourse, and W. Ross for advice, insightful discussions, and inspiring work. Cryo-EM data were collected at the Rockefeller University Evelyn Gruss Lipper Cryo-electron Microscopy Resource Center and at the Simons Electron Microscopy Center and National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy, located at the New York Structural Biology Center (NYSBC). NYSBC is supported by grants from the Simons Foundation (SF349247); New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research; the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM103310); and the Agouron Institute (F00316). This work was supported by NIH Grant R35 GM118130 and Re-Entry Supplement R35 GM118130-04S1 to S.A.D.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2112877118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Structural models and cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the PDB and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMBD). The cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the EMBD under accession codes EMD-23892 (Eco Eσ70-λPR class I [RPo]), EMD-23893 (Eco Eσ70-λPR class II [I3]), EMD-23895 (Eco Eσ70-λPR-5C RPo), and EMD-23897 (Eco Eσ70-T7A1 RPo). The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under accession codes 7MKD (Eco Eσ70-λPR class I [RPo]), 7MKE (Eco Eσ70-λPR class II [I3]), 7MKI (Eco Eσ70-λPR-5C RPo), and 7MKJ (Eco Eσ70-T7A1 RPo). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Record M. T. Jr., Reznikoff W. S., Craig M. L., McQuade K. L., Schlax P. J., “Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (Eσ70), promoters, and the kinetics of the steps of transcription initiation” in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology (ASM Press, ed. 2, 1996), 1, pp. 792–821. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClure W. R., Mechanism and control of transcription initiation in prokaryotes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 54, 171–204 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haugen S. P., Ross W., Gourse R. L., Advances in bacterial promoter recognition and its control by factors that do not bind DNA. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 507–519 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warman E. A., et al., Widespread divergent transcription from bacterial and archaeal promoters is a consequence of DNA-sequence symmetry. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 746–756 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ju X., Li D., Liu S., Full-length RNA profiling reveals pervasive bidirectional transcription terminators in bacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1907–1918 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harden T. T., et al., Alternative transcription cycle for bacterial RNA polymerase. Nat. Commun. 11, 448 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feklístov A., Sharon B. D., Darst S. A., Gross C. A., Bacterial sigma factors: A historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68, 357–376 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruber T. M., Gross C. A., Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57, 441–466 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonetto M., Gribskov M., Gross C. A., The σ70 family: Sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J. Bacteriol. 174, 3843–3849 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell E. A., et al., Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity σ subunit. Mol. Cell 9, 527–539 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saecker R. M., Record M. T. Jr, Dehaseth P. L., Mechanism of bacterial transcription initiation: RNA polymerase—Promoter binding, isomerization to initiation-competent open complexes, and initiation of RNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 412, 754–771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galburt E. A., The calculation of transcript flux ratios reveals single regulatory mechanisms capable of activation and repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E11604–E11613 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen D., Galburt E. A., The context-dependent influence of promoter sequence motifs on transcription initiation kinetics and regulation. J. Bacteriol. 203, e00512-20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruff E. F., Record M. T. Jr, Artsimovitch I., Initial events in bacterial transcription initiation. Biomolecules 5, 1035–1062 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gourse R. L., et al., Transcriptional responses to ppGpp and DksA. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 72, 163–184 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travers A. A., Promoter sequence for stringent control of bacterial ribonucleic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 141, 973–976 (1980). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straney D. C., Crothers D. M., Intermediates in transcription initiation from the E. coli lac UV5 promoter. Cell 43, 449–459 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robb N. C., et al., The transcription bubble of the RNA polymerase-promoter open complex exhibits conformational heterogeneity and millisecond-scale dynamics: Implications for transcription start-site selection. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 875–885 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerner E., Ingargiola A., Weiss S., Characterizing highly dynamic conformational states: The transcription bubble in RNAP-promoter open complex as an example. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 123315 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suh W. C., Ross W., Record M. T. Jr, Two open complexes and a requirement for Mg2+ to open the λ PR transcription start site. Science 259, 358–361 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontur W. S., Saecker R. M., Capp M. W., Record M. T. Jr, Late steps in the formation of E. coli RNA polymerase-λ P R promoter open complexes: Characterization of conformational changes by rapid [perturbant] upshift experiments. J. Mol. Biol. 376, 1034–1047 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gries T. J., Kontur W. S., Capp M. W., Saecker R. M., Record M. T. Jr, One-step DNA melting in the RNA polymerase cleft opens the initiation bubble to form an unstable open complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10418–10423 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haugen S. P., et al., rRNA promoter regulation by nonoptimal binding of σ region 1.2: An additional recognition element for RNA polymerase. Cell 125, 1069–1082 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker M. M., Gaal T., Josaitis C. A., Gourse R. L., Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 673–688 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson K. L., et al., Mechanism of transcription initiation and promoter escape by E. coli RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E3032–E3040 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haugen S. P., Ross W., Manrique M., Gourse R. L., Fine structure of the promoter-σ region 1.2 interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3292–3297 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenkin N., et al., Region 1.2 of the RNA polymerase σ subunit controls recognition of the −10 promoter element. EMBO J. 26, 955–964 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NandyMazumdar M., et al., RNA polymerase gate loop guides the nontemplate DNA strand in transcription complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 14994–14999 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae B., Feklistov A., Lass-Napiorkowska A., Landick R., Darst S. A., Structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme open promoter complex. eLife 4, e08504 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuo Y., Steitz T. A., Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell 58, 534–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y., et al., Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science 338, 1076–1080 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu R. S., et al., Structural basis of transcription initiation by bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24549–24559 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyaci H., Chen J., Jansen R., Darst S. A., Campbell E. A., Structures of an RNA polymerase promoter melting intermediate elucidate DNA unwinding. Nature 565, 382–385 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J., et al., E. coli TraR allosterically regulates transcription initiation by altering RNA polymerase conformation. eLife 8, e49375 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J., et al., Stepwise promoter melting by bacterial RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell 78, 275–288.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin Y., et al., Structural basis of ribosomal RNA transcription regulation. Nat. Commun. 12, 528 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogozina A., Zaychikov E., Buckle M., Heumann H., Sclavi B., DNA melting by RNA polymerase at the T7A1 promoter precedes the rate-limiting step at 37 degrees C and results in the accumulation of an off-pathway intermediate. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 5390–5404 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sclavi B., et al., Real-time characterization of intermediates in the pathway to open complex formation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at the T7A1 promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4706–4711 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schickor P., Metzger W., Werel W., Lederer H., Heumann H., Topography of intermediates in transcription initiation of E.coli. EMBO J. 9, 2215–2220 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen J., Noble A. J., Kang J. Y., Darst S. A., Eliminating effects of particle adsorption to the air/water interface in single-particle cryo-electron microscopy: Bacterial RNA polymerase and CHAPSO. J. Struct. Biol X 1, 100005 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheres S. H. W., RELION: Implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 519–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feklistov A., Darst S. A., Structural basis for promoter-10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase σ subunit. Cell 147, 1257–1269 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross W., Ernst A., Gourse R. L., Fine structure of E. coli RNA polymerase-promoter interactions: α subunit binding to the UP element minor groove. Genes Dev. 15, 491–506 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross W., Schneider D. A., Paul B. J., Mertens A., Gourse R. L., An intersubunit contact stimulating transcription initiation by E. coli RNA polymerase: Interaction of the α C-terminal domain and σ region 4. Genes Dev. 17, 1293–1307 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Naryshkin N., Revyakin A., Kim Y., Mekler V., Ebright R. H., Structural organization of the RNA polymerase-promoter open complex. Cell 101, 601–611 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bae B., et al., Phage T7 Gp2 inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase involves misappropriation of σ70 domain 1.1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 19772–19777 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mekler V., et al., Structural organization of bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme and the RNA polymerase-promoter open complex. Cell 108, 599–614 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane W. J., Darst S. A., Molecular evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases: Sequence analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 671–685 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lane W. J., Darst S. A., Molecular evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases: Structural analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 686–704 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaychikov E., Denissova L., Meier T., Götte M., Heumann H., Influence of Mg2+ and temperature on formation of the transcription bubble. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2259–2267 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plaskon D. M., et al., Temperature effects on RNA polymerase initiation kinetics reveal which open complex initiates and that bubble collapse is stepwise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2021941118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsu L. M., Promoter escape by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Ecosal Plus 3, 10.1128/ecosalplus.4.5.2.2 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Skancke J., Bar N., Kuiper M., Hsu L. M., Sequence-dependent promoter escape efficiency is strongly influenced by bias for the pretranslocated state during initial transcription. Biochemistry 54, 4267–4275 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heyduk E., Heyduk T., DNA template sequence control of bacterial RNA polymerase escape from the promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 4469–4486 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ko J., Heyduk T., Kinetics of promoter escape by bacterial RNA polymerase: Effects of promoter contacts and transcription bubble collapse. Biochem. J. 463, 135–144 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazumder A., Kapanidis A. N., Recent advances in understanding σ70-dependent transcription initiation mechanisms. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3947–3959 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sen R., Nagai H., Hernandez V. J., Shimamoto N., Reduction in abortive transcription from the λPR promoter by mutations in region 3 of the σ70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 9872–9877 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gourse R. L., Visualization and quantitative analysis of complex formation between E. coli RNA polymerase and an rRNA promoter in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 9789–9809 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubori T., Shimamoto N., A branched pathway in the early stage of transcription by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 256, 449–457 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Susa M., Sen R., Shimamoto N., Generality of the branched pathway in transcription initiation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15407–15412 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Revyakin A., Liu C., Ebright R. H., Strick T. R., Abortive initiation and productive initiation by RNA polymerase involve DNA scrunching. Science 314, 1139–1143 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kapanidis A. N., et al., Initial transcription by RNA polymerase proceeds through a DNA-scrunching mechanism. Science 314, 1144–1147 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheetham G. M., Steitz T. A., Structure of a transcribing T7 RNA polymerase initiation complex. Science 286, 2305–2309 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Straney D. C., Crothers D. M., A stressed intermediate in the formation of stably initiated RNA chains at the Escherichia coli lac UV5 promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 193, 267–278 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winkelman J. T., et al., Crosslink mapping at amino acid-base resolution reveals the path of scrunched DNA in initial transcribing complexes. Mol. Cell 59, 768–780 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vo N. V., Hsu L. M., Kane C. M., Chamberlin M. J., In vitro studies of transcript initiation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. 2. Formation and characterization of two distinct classes of initial transcribing complexes. Biochemistry 42, 3787–3797 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Susa M., Kubori T., Shimamoto N., A pathway branching in transcription initiation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 1807–1817 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Drennan A., et al., Key roles of the downstream mobile jaw of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase in transcription initiation. Biochemistry 51, 9447–9459 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruff E. F., et al., E. coli RNA polymerase determinants of open complex lifetime and structure. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 2435–2450 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mekler V., Minakhin L., Borukhov S., Mustaev A., Severinov K., Coupling of downstream RNA polymerase-promoter interactions with formation of catalytically competent transcription initiation complex. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 3973–3984 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kontur W. S., Saecker R. M., Davis C. A., Capp M. W., Record M. T. Jr, Solute probes of conformational changes in open complex (RPo) formation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at the λPR promoter: Evidence for unmasking of the active site in the isomerization step and for large-scale coupled folding in the subsequent conversion to RPo. Biochemistry 45, 2161–2177 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hsu L. M., Vo N. V., Kane C. M., Chamberlin M. J., In vitro studies of transcript initiation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. 1. RNA chain initiation, abortive initiation, and promoter escape at three bacteriophage promoters. Biochemistry 42, 3777–3786 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Structural models and cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the PDB and the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMBD). The cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the EMBD under accession codes EMD-23892 (Eco Eσ70-λPR class I [RPo]), EMD-23893 (Eco Eσ70-λPR class II [I3]), EMD-23895 (Eco Eσ70-λPR-5C RPo), and EMD-23897 (Eco Eσ70-T7A1 RPo). The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the PDB under accession codes 7MKD (Eco Eσ70-λPR class I [RPo]), 7MKE (Eco Eσ70-λPR class II [I3]), 7MKI (Eco Eσ70-λPR-5C RPo), and 7MKJ (Eco Eσ70-T7A1 RPo). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.