Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Clavien-Dindo classification is widely used to report postoperative morbidity but may underestimate the severity of colectomy complications.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess how well the Clavien-Dindo classification represents the severity of all grades of complications after colectomy using cost of care modeling.

DESIGN:

Retrospective cohort study.

SETTING:

Comprehensive cancer center.

PATIENTS:

Consecutive patients (n = 1807) undergoing elective colon or rectal resections without a stoma performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 2009 and 2014 who were followed up for ≥ 90 days, were not transferred to other hospitals, and did not receive intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Complication severity measured by the highest-grade complication per patient and attributable outpatient and inpatient costs. Associations were evaluated between patient complication grade and cost during 3 time periods: the 90 days after surgery, index admission, and post-discharge (up to 90 days).

RESULTS:

Of the 1807 patients (median age 62 years), 779 (43%) had a complication; 80% of these patients had only grade 1 or 2 complications. Increasing patient complication grade correlated with 90-day cost, driven by inpatient cost differences (p < 0.001). For grade 1 and 2 patients, most costs were incurred after discharge and were the same between these grade categories. Among patients with a single complication (52%), there was no difference in index hospitalization, post-discharge or total 90-day costs between grade 1 and 2 categories.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design, generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS:

The Clavien-Dindo classification correlates well with 90-day costs, driven largely by inpatient resource utilization. Clavien-Dindo does not discriminate well among low-grade complication patients in terms of their substantial post-discharge costs. These patients represent 80% of patients with a complication after colectomy. Examining the long-term burden associated with complications can help refine the Clavien-Dindo classification for use in colectomy studies.

Keywords: Clavien-Dindo, Colectomy, Complications, Cost of care

Abstract

ANTECEDENTES:

La clasificación de Clavien-Dindo es utilizada ampliamante para conocer la morbilidad posoperatoria, pero puede subestimar la gravedad de las complicaciones de la colectomía.

OBJETIVO:

Evaluar que tan bien representa la clasificación de Clavien-Dindo la gravedad de todos los grados de complicaciones después de la colectomía utilizando un modelo de costo de la atención.

DISEÑO:

Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo.

ENTORNO CLÍNICO:

Centro oncológico integral.

PACIENTES:

Pacientes consecutivos (n = 1807) sometidos a resecciones electivas de colon o recto sin estoma realizadas en el Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center entre 2009 y 2014 que fueron seguidos durante ≥ 90 días, no fueron transferidos a otros hospitales y no recibieron quimioterapia intraperitoneal.

PRINCIPALES MEDIDAS DE VALORACION:

Gravedad de la complicación medida por la complicación de mayor grado por paciente y los costos atribuibles para pacientes ambulatorios y hospitalizados. Se evaluó la asociación entre el grado de complicación del paciente y el costo durante 3 períodos de tiempo: posterior a la cirugía (hasta 90 días), a su ingreso y posterior al egreso (hasta 90 días).

RESULTADOS:

De los 1807 pacientes (mediana de edad de 62 años), 779 (43%) tuvieron una complicación; El 80% de estos pacientes tuvieron solo complicaciones de grado 1 o 2. El aumento del grado de complicación del paciente se correlacionó con el costo a 90 días, impulsado por las diferencias en el costo de los pacientes hospitalizados (p <0,001). Para los pacientes de grado 1 y 2, la mayoría de los costos se incurrieron después del alta y fueron los mismos entre ambas categorías. Entre los pacientes con una sola complicación (52%), no hubo diferencia en el índice de hospitalización, posterior al alta o en el costo total de 90 días entre las categorías de grado 1 y 2.

LIMITACIONES:

Diseño retrospectivo, generalizabilidad.

CONCLUSIONES:

La clasificación de Clavien-Dindo se correlaciona bien con los costos a 90 días, impulsados en gran parte por la utilización de recursos de pacientes hospitalizados. Clavien-Dindo no discrimina entre los pacientes con complicaciones de bajo grado en términos de sus costos sustanciales posterior al alta. Estos pacientes representan el 80% de los pacientes aquellos con una complicación tras la colectomía. Examinar la carga a largo plazo asociada a las complicaciones puede ayudar a mejorar la clasificación de Clavien-Dindo para su uso en estudios de colectomía. (Traducción—Dr. Yazmin Berrones-Medina)

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative morbidity is an important outcome measure in colorectal comparative effectiveness research.1,2 Along with oncologic control, the complication rate is a key metric by which we compare and assess the benefits of new surgical approaches and technologies. Decreasing complications has been a strong driver for innovations such as minimally invasive surgery, natural orifice procedures, and multimodality treatment. However, definitions of various complications and approaches to quantifying their severity have varied widely from study to study, limiting our ability to integrate and compare their findings.3–5

In the past 15 years, the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification has been increasingly used to compare postoperative morbidity in surgical studies.6,7 First developed as a reporting tool for Morbidity and Mortality conference, it is now commonly requested by journals and peer reviewers, and has been an outcome measure in randomized trials.8–10 The CD classification defines a complication as “any deviation from the expected postoperative course” and assigns it a severity according to the level of resource utilization required to treat it (Table 1). It has been validated with respect to length of stay and 30-day direct hospital cost in the adult surgical population, and is reliably scored by attending surgeons and residents alike.11,12

Table 1. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complication severity.

From Dindo et al.7

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | Any deviation from the normal postoperative course without the need for pharmacological treatment, or surgical, endoscopic, and radiological interventions. Allowed therapeutic regimens are: drugs as antiemetics, antipyretics, analgesics, diuretics and electrolytes, and physiotherapy. This grade also includes wound infections opened at the bedside |

| II | Requiring pharmacological treatment with drugs other than such allowed for grade I complications, or requiring blood transfusion or total parenteral nutrition |

| III | Requiring surgical, endoscopic, or radiological intervention |

| IIIa | Intervention not under general anesthesia |

| IIIb | Intervention under general anesthesia |

| IV | Life-threatening complication (including central nervous system complications) requiring intensive care unit (ICU) management |

| IVa | Single organ dysfunction (including dialysis) |

| IVb | Multiorgan dysfunction |

| V | Death of a patient |

Despite the intuitiveness of the CD classification, clinical experience highlights potential obstacles to its validity as an outcome measure in colorectal surgery. First, the classification lends itself to focusing on “high-grade” complications since these require inpatient management, which can be identified and quantified reliably. However, most complications after colorectal surgery fall into “low-grade” categories. Surgical site infections (SSIs), for instance, are often classified by this system as “low-grade” because they require few in-hospital resources and are instead mostly managed post-discharge, on an outpatient basis. These are graded in a similar manner as hypokalemia, atelectasis on chest x-ray, nausea treated with antiemetics and other low-grade complications which require no long-term management. The current literature has not demonstrated the construct validity of the CD classification for the low-grade complications commonly seen after colorectal surgery e.g., whether SSI complications within a given grade are of similar severity, and whether increasing grade indicates increasing SSI severity. The question is critical if the CD classification is to be used as an outcome measure in colorectal surgery. For example, if a new surgical technique decreases grade 2 pulmonary complications but increases grade 1 wound complications, it would be difficult to assess the superiority of one technique over the other given the heterogeneity in complication severity encompassed in these two categories.

To assess how well the Clavien-Dindo classification represents the severity of complications after colon and rectal resection, we quantified the severity of complications using 90-day direct medical costs including inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation and home care utilization. We then examined associations between increasing complication grades and increasing costs during the overall 90-day period, the index admission and post-discharge period to see how well the classification correlated with severity in these time-periods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to identify all patients who had an elective colon or rectal resection at our institution between 2009 and 2014. To focus on the costs associated with complications, we excluded new ostomy patients who were likely to require routine post-discharge utilization regardless of complications. We also excluded patients who were transferred to another hospital or were lost to follow-up within 90-days of surgery. Lastly, we excluded patients who received intraperitoneal chemotherapy as inpatients. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Visiting Nurse Service of New York.

Clinical, operative, and postoperative complications within 90 days of surgery were collected by extensive review of the electronic medical records by two reviewers (MW, MK). An additional reviewer (PS) confirmed key outcomes. Comorbidities documented within 6 months of the date of surgery were gathered from an administrative database. Complications were described using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program descriptions when possible.

All complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification,7 and patients were classified according the highest CD grade complication they developed (PCD 1, 2, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b, 5), allowing patients with multiple complications to be represented by a single severity grade.7,12,13 The “disability” suffix was not used because its relationship with severity categories (i.e. 1d vs. 2d) has not been specified, nor is it commonly used in the literature, including in the CD validation studies.8,11,14

We quantified the severity of complications using direct medical costs incurred during the first 90 days after surgery. Direct cost data was obtained from our accounting system and from the most frequently used homecare provider for our patients, the Visiting Nurse Service of New York (VNSNY). Costs were normalized to reflect Medicare reimbursement levels using the ratio of hospital costs to Medicare reimbursement based on diagnosis-related group (DRG) and CPT codes, as previously described.15 All hospital costs were estimated based on 2014 US dollars using 2014 costs per unit for all services and were adjusted for inflation to reflect 2014 costs. Final Medicare-proportional dollar (MP$) cost estimates were rounded to the nearest $10.

To focus on the costs associated with complications, day-of-surgery costs were subtracted from all calculations. All costs and complications within 30 days of surgery were included, as this is the commonly used window of analysis for surgical studies and for the CD classification validation.1,12,16 After the 30-day period, attributable costs and complications included those that were directly related to surgery, such as an admission to a surgical service/ward, homecare services, and any emergency room consult managed by a surgical team.

Missing costs were imputed using multiple imputation methods. Missing homecare costs for patients who received homecare from a different provider were imputed based on known VNS homecare costs using a two-step multiple imputation method in which 5 imputed datasets were created. First, the duration of care was imputed for patients with missing start or end dates. Next, missing costs were imputed using predictive mean matching with patient characteristics and total post-discharge cost (sans homecare costs) as covariates.17,18 For outside hospital readmissions and emergency room visits, missing costs were imputed by taking the average of MSK costs with similar indications. Outside hospital radiology costs were imputed by using the mean cost of these services at MSK. Finally, rehabilitation center costs were calculated on a per diem basis using a cost of $1301 per day, based on the 2013 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services report, which lists an average inpatient rehabilitation facility stay cost as $16785 (in 2014 dollars) and an average length of stay (LOS) of 12.9 days. Due to the use of multiple imputation, all summary statistics are pooled estimates, such that summary statistics should be interpreted as estimates of the true population means.

A linear mixed effects regression model was used to analyze the relationship between cost estimates and PCD grade during the 90 days after surgery, as well as costs within that period incurred during the index admission or post-discharge. The PCD 3a and 3b categories were grouped together due to paucity of these outcomes, as were PCD 4 and 5 categories. Additional exploratory analyses comparing costs between complications and costs based on setting (inpatient vs outpatient) used parametric and nonparametric tests for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively. In all models, surgeon was treated as a clustering variable. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Between 2009 and 2014, 1807 patients underwent elective colon or rectal resection. Demographic, preoperative, and operative characteristics are shown in Table 2. Most patients underwent colectomies for cancer. Approximately 62% of the operations were performed using a minimally invasive approach and 6 surgeons from the colorectal division performed all operations. The most frequently imputed variable was homecare cost, which was missing for 15% of patients.

Table 2. Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing colon or rectal resection between 2009 and 2014 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (n = 1807).

Categorical data are presented as n (%) and continuous data as median (IQR).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | 61.6 (50.8–72.1) |

|

| |

| Female sex | 927 (51%) |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 111 (6%) |

| Caucasian | 1479 (82%) |

| Other | 215 (12%) |

|

| |

| BMI | 27.8 (24.2–31.7) |

|

| |

| Insurance | |

| Medicare or Medicaid | 841 (47%) |

| Private | 966 (53%) |

|

| |

| 7th AJCC stage | |

| 0/Benign | 247 (14%) |

| I | 356 (20%) |

| II | 472 (26%) |

| III | 42 (24%) |

| IV | 300 (17%) |

|

| |

| Smoking history | |

| Current | 188 (10%) |

| Former | 615 (34%) |

| Never | 1004 (56%) |

|

| |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 246 (14%) |

|

| |

| Preoperative homecare | 19 (1%) |

|

| |

| Surgical approach | |

| Open | 692 (38%) |

| Laparoscopic | 846 (47%) |

| Robotic | 268 (15%) |

Complications

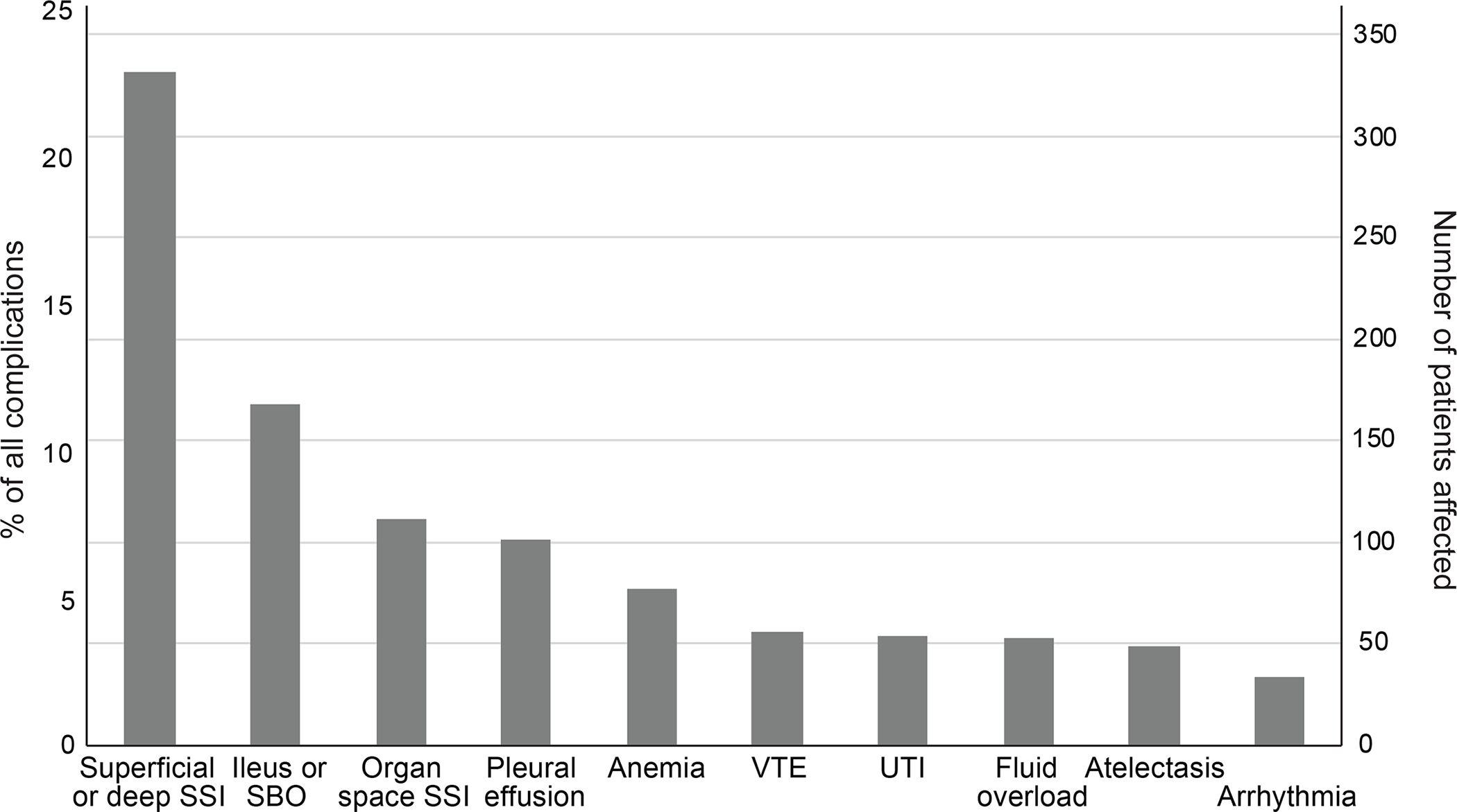

There were 1465 complications recorded in 779 patients, for an overall 90-day morbidity rate of 43% and mortality rate of 0.7%. The majority (52%) of patients who suffered a complication had a single complication. A list of the most common complications is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Frequency of 10 most common complications. SSI, surgical site infection; SBO, small bowel obstruction; VTE, venous thromboembolism; UTI, urinary tract infection.

When classified by CD grade, grade 2 complications were the most frequent (47%), followed by grade 1 (40%) (Supplementary Table 1). Together, these low-grade complications accounted for 87% of all complications.

The SSI rate was 22%, including superficial, deep, and organ space infections. Most of these (75%) were superficial or deep incisional infections, and the majority of these were grade 1 (57%) or grade 2 (41%).

Per-Patient Highest CD Grade Complications

The number and proportion of patients with complications stratified by their highest graded complication are presented in Table 3. Patients whose highest CD complication grade was 2 (PCD 2) or 1 (PCD 1) accounted for 80% of the 779 patients with a postoperative complication. Patients whose highest complication was grade 3 (PCD 3) were most likely to have an attributable readmission (75 of 131 patients, 57%) (Table 3). Fourteen patients (1%) with no complications had a readmission in 90 days, most commonly for chemotherapy-related adverse events.

Table 3. Number and proportion of patients with any complication stratified by the highest grade complication experienced.

As some patients had more than one complication, those listed are not necessarily the highest grade.

| PCD Category | Complication (3 most common) | n (%)a | Requiring readmissionb | Requiring homecareb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PCD 1 | 230 (30%) | 21 (9%) | 138 (60%) | |

| Superficial or deep incisional SSI | 103 (13%) | |||

| Ileus or small bowel obstruction | 38 (5%) | |||

| Atelectasis | 21 (3%) | |||

|

| ||||

| PCD 2 | 389 (50%) | 89 (23%) | 202 (52%) | |

| Superficial or deep incisional SSI | 164 (21%) | |||

| Ileus or small bowel obstruction | 91 (12%) | |||

| Hemorrhage or anemia | 53 (7%) | |||

|

| ||||

| PCD 3 | 131 (17%) | 75 (57%) | 92 (70%) | |

| Organ space SSI | 81 (10%) | |||

| Superficial or deep surgical site infection | 58 (7%) | |||

| Ileus or small bowel obstruction | 31 (4%) | |||

|

| ||||

| PCD 4+ | 29 (4%) | 10 (35%) | 14 (48%) | |

| Organ space SSI | 9 (1%) | |||

| Hemorrhage or anemia | 8 (1%) | |||

| Ileus or small bowel obstruction | 8 (1%) | |||

Percent of all patients with at least one complication (n = 779). Some patients experienced more than one complication within one or more grades.

Percent of patients with most severe complication of that CD grade.

PCD, highest graded complication per patient; SSI, surgical site infection

In sum, 535 patients required homecare services after discharge and 36 were discharged to rehab. Most homecare referrals were for attributable complications (501, 94%), with the most common being grade 1 and 2 superficial and deep incisional SSIs. Patients requiring homecare received services for an average of 51 days (95% CI, 42.8–53.4). A subset of patients (93/535, 16%) had multiple indications for homecare, usually because of a secondary referral to physical therapy. Among the PCD 3 patients, 50 (31%) ultimately required homecare for the management of lesser grade 1 or 2 superficial or deep SSI. Finally, 89 patients with no complications (9%) had a referral for home physical therapy. Indications for readmissions and homecare services are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

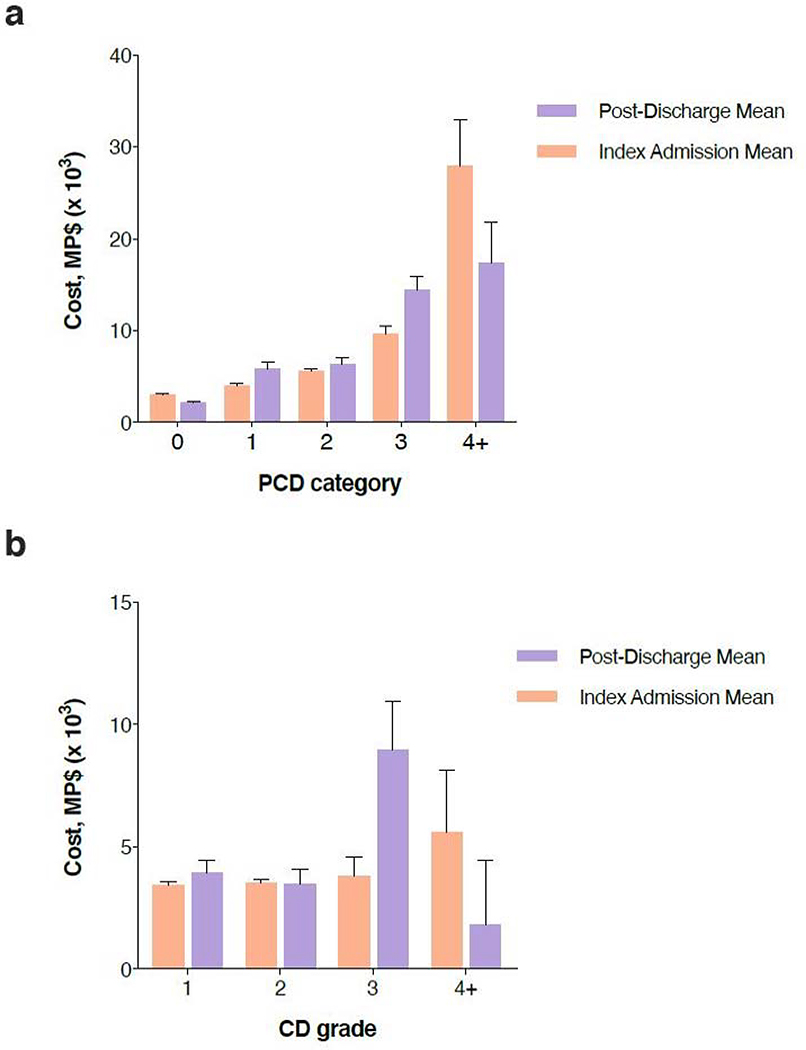

Per-Patient Costs by Highest CD Grade Complication

Figure 2a represents the per-patient estimated index hospitalization and post-discharge (up to 90 days post-surgery) costs, categorized by PCD grade. Increasing PCD grade was associated with greater total 90-day cost (p < 0.001) in both univariate and multivariable analyses. Readmissions accounted for most of the cost differences in post-discharge costs between patients with low-grade complications (PCD 1 and PCD 2) and those with PCD 3+ patients. On average, readmission costs accounted for only 13% of total post-discharge costs for PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients, compared with 46% for PCD 3+ patients. Patients with no complications had significantly lower costs compared to all PCD categories. Costs are further elaborated in Supplementary Table 4.

Figure 2a and 2b.

Estimated cost of care according to a) highest graded complication per patient (PCD) for all patients with complications, and b) complication grade in patients with a single complication, in Medicare proportional dollars (MP$). Excludes day of surgery costs, rounded to the nearest $10. Data are presented as median ± SE.

Overall 90-day costs differed significantly between PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients on both univariate and multivariable analyses. The largest driver of this difference was inpatient utilization during the index admission, as length of stay was significantly longer among PCD 2 patients (8 days vs. 7 days for PCD 1; p < 0.001). In contrast, there was no difference in post-discharge costs between PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients on either univariate or multivariable analyses (p = 0.75 unadjusted, 0.67 adjusted). In these low-grade complication categories, post-discharge costs contributed more to the 90-day total than did the index admission.

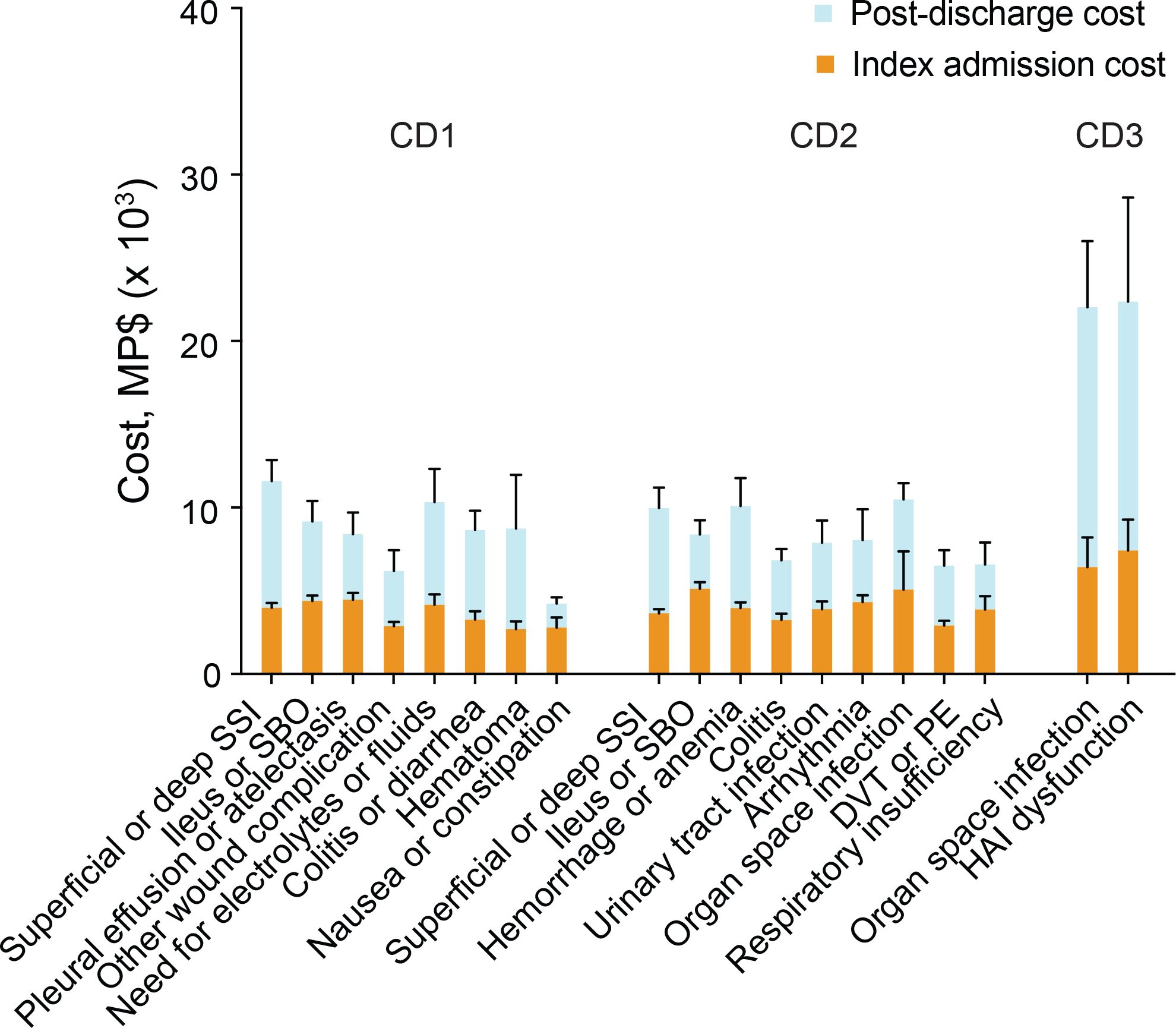

Figure 2b shows the per-patient estimated index admission and post-discharge costs in the 405 patients (52%) who had only a single complication. Among patients with grade 1 and 2 complications, there was no association between increasing complication grade and cost in the index admission, post-discharge or total 90-day periods. Figure 3 shows these costs according to the complication suffered. Again, costs were similar between within the low-grade categories, and for complications such as SSI and ileus, grade 1 complications appeared to incur more costs than grade 2.

Figure 3.

Estimated cost of individual complications. Data are derived from patients with only 1 complication (n = 405) and represented as 2014 Medicare proportional dollars (MP$) rounded to the nearest $10, ± SE, excluding surgery costs. Only complications affecting ≥ 5 patients are shown.

Superficial and deep incisional SSIs were the most common indications for homecare in PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients. There was no difference in mean homecare costs (p = 0.31 unadjusted, p = 0.07 adjusted) or length of homecare services (p = 0.45 unadjusted, p = 0.14) between these categories on unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Other common low-grade complications including ileus and hemorrhage or anemia requiring transfusion, did not require referral to homecare services. Venous thromboembolism, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, commonly required homecare referral for anticoagulation.

When we analyzed costs by setting (inpatient vs outpatient) instead of time-period (index admission vs post-discharge), we saw similar associations (Supplementary Table 5). There was a significant difference in inpatient costs between PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients, but their outpatient costs were the same. Outpatient costs accounted for the majority of costs in PCD 1 patients (56%). Among PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients with an SSI, there was no difference in outpatient or total 90-day costs.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed the strong correlation between Clavien-Dindo complication grade and severity, as quantified by attributable inpatient and outpatient direct medical costs in the first 90 days after surgery. Among PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients, the association between cost and grade was driven by a 1-day length of stay difference during the index admission, with no difference seen in the substantial post-discharge costs between these groups. When the analysis was limited to patients with a single complication, we found no difference in the 90-day, index admission or post-discharge costs between patients with grade 1 versus grade 2 complications.

Our findings suggest that the CD classification underestimates the burden of some complications after colectomy. This is especially true for patients whose complications were low-grade and substantially managed in the outpatient setting, which account for 80% of patients with a complication after colectomy. The dominating effect of PCD grade on overall 90-day costs is due to the high cost of inpatient care relative to outpatient costs; for example, the average cost of 1 day of inpatient care was nearly 6 times the costs associated with a single day of homecare.

Healthcare utilization beyond the discharge period is rarely quantified or included in surgical outcomes studies.19–21 In our cohort, most costs were incurred in the post-discharge period for PCD 1–3 patients, and nearly 1/3 of all patients received homecare for an attributable indication. Among PCD 1 and PCD 2 patients, 55% required homecare services for average duration was 51 days, consistent with the few reports from the colorectal literature. In the CLASICC trial, post-discharge outpatient utilization was also common (38.3–77.4%, depending on the service).20 In a study of colorectal cancer patients from a Canadian registry, nearly 2/3 of patients received homecare services.22

The severity of superficial and deep incisional SSIs was potentially the most underestimated complication by the CD classification. Nearly all SSIs (98%) were grade 1 or 2, yet they represented 49% of referrals to homecare. In addition, 31% of PCD 3 patients required homecare specifically for the treatment of lower-graded SSIs. These data suggest that for some patients, care for their high-grade complications ended with discharge, while care for their low-grade complications continued for a significant time after. In patients with only one complication, SSIs were the most expensive low-grade complications, and grade 1 SSIs were indistinguishable from grade 2 SSIs in terms of cost. At a minimum, we suggest that deep and superficial incisional SSIs should be classified as grade 2 complications, regardless of whether antibiotics are used.

The limitations of the CD classification likely apply to other indices. Both the Accordion Severity Grading System and the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI)1,9 were created by surveying experts regarding the inpatient care required to manage complications.23,24 While the framework is intuitive, our study exposes a pitfall of this approach, which tends to focus on easy-to-quantify, hospital-based treatments. By considering the long-term burden associated with complications, many difficult-to-quantify “treatments”—time, dressing changes, nursing care, absenteeism— can be accounted for. Our findings suggest that optimization of the CD classification for colectomy studies requires a better understanding of the true burden associated with complications. Additional modifications including item selection to focus on common and impactful complications could help improve responsiveness and discriminative ability. Ultimately, a colorectal-specific outcome measure based on the Clavien-Dindo framework may be ideal.

This was a retrospective study conducted at a specialized cancer center. While this allowed us to minimize practice pattern variations, it may also limit the generalizability of our findings.25 Compared to nationwide cohorts, our patients were younger, but had similar AJCC stages at diagnosis.26 The age discrepancy permitted us to analyze healthcare utilization and complications among a growing cohort of younger colorectal cancer patients who are not Medicare beneficiaries.26 Our 43% complication rate might appear high, but we believe this is reflective of a known underreporting of low-grade complications in the literature.27–29 At least one other study that aimed to captured all low-grade complications reported a similar 41% overall morbidity rate.28

An additional limitation of this study is missing data, especially in the outpatient setting. While costs were imputed using validated methods, imputation can lead to less precise estimates. The inclusion of direct non-medical costs, such as those related to absenteeism from work in patients and their caregivers, was not within the scope of the present study, but their impacts cannot be underestimated.30–32 Inclusion of these costs in our analysis might alter some of our findings, as patients who require significant prolonged outpatient care and can’t work could incur more “costs” than those whose treatment ended at discharge.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Clavien-Dindo classification may underestimate the true severity of many low-grade complications after colectomy, which are the most common complications after colectomy. A better understanding of the burden associated with surgical complications could guide modifications of the well-known CD classification or development of a more discriminative and sensitive outcome measure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. We thank Jessica Moore for her assistance in editing this manuscript.

Funding/Support: NCI grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Financial Disclaimers: Dr. Garcia-Aguilar has received honoraria from Intuitive Inc., Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson.

REFERENCES

- 1.Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;258:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan MF, Radzyner M, Rubin DM. Outcome--more than just operative mortality. J Surg Oncol 2009;99:470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin RC II, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Quality of complication reporting in the surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2002;235:803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton R Surgical research or comic opera: questions, but few answers. Lancet. 1996;347:984–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel AS, Bergman A, Moore BW, Haglund U. The economic burden of complications occurring in major surgical procedures: a systematic review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11:577–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2009;250:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schultz JK, Yaqub S, Wallon C, et al. ; SCANDIV Study Group. Laparoscopic lavage vs primary resection for acute perforated diverticulitis: the SCANDIV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1364–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwyer ME, Dwyer JT, Cannon GM Jr, Stephany HA, Schneck FX, Ost MC. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications is not a statistically reliable system for grading morbidity in pediatric urology. J Urol. 2016;195:460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vonlanthen R, Slankamenac K, Breitenstein S, et al. The impact of complications on costs of major surgical procedures: a cost analysis of 1200 patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254:907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beilan J, Strakosha R, Palacios DA, Rosser CJ. The Postoperative Morbidity Index: a quantitative weighing of postoperative complications applied to urological procedures. BMC Urol. 2014;14:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitropoulos D, Artibani W, Biyani CS, Bjerggaard Jensen J, Rouprêt M, Truss M. Validation of the Clavien-Dindo Grading System in Urology by the European Association of Urology Guidelines Ad Hoc Panel. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selby LV, Gennarelli RL, Schnorr GC, et al. Association of hospital costs with complications following total gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:953–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bilimoria KY, Cohen ME, Ingraham AM, et al. Effect of postdischarge morbidity and mortality on comparisons of hospital surgical quality. Ann Surg. 2010;252:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briggs A, Clark T, Wolstenholme J, Clarke P. Missing... presumed at random: cost-analysis of incomplete data. Health Econ. 2003;12:377–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton A, Billingham LJ, Bryan S. Cost-effectiveness in clinical trials: using multiple imputation to deal with incomplete cost data. Clin Trials. 2007;4:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacks GD, Lawson EH, Dawes AJ, Gibbons MM, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Which Patients Require More Care after Hospital Discharge? An Analysis of Post-Acute Care Use among Elderly Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220:1113–1121 e1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franks PJ, Bosanquet N, Thorpe H, et al. ; CLASICC trial participants. Short-term costs of conventional vs laparoscopic assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial). Br J Cancer. 2006;95:6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tevis SE, Kennedy GD. Postoperative complications and implications on patient-centered outcomes. J Surg Res. 2013;181:106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittmann N, Liu N, Porter J, et al. ; Hon. Utilization and costs of home care for patients with colorectal cancer: a population-based study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:E11–E17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porembka MR, Hall BL, Hirbe M, Strasberg SM. Quantitative weighting of postoperative complications based on the accordion severity grading system: demonstration of potential impact using the american college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slankamenac K, Graf R, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. Perception of surgical complications among patients, nurses and physicians: a prospective cross-sectional survey. Patient Saf Surg. 2011;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krell RW, Girotti ME, Dimick JB. Extended length of stay after surgery: complications, inefficient practice, or sick patients? JAMA Surg. 2014;149:815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures. 2017; https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-figures.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 27.Gunnarsson U, Seligsohn E, Jestin P, Påhlman L. Registration and validity of surgical complications in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2003;90:454–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazeh H, Samet Y, Abu-Wasel B, et al. Application of a novel severity grading system for surgical complications after colorectal resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strong VE, Selby LV, Sovel M, et al. Development and assessment of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Surgical Secondary Events grading system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:1061–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yabroff KR, Borowski L, Lipscomb J. Economic studies in colorectal cancer: challenges in measuring and comparing costs. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2013;2013:62–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al. The personal financial burden of complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Cancer. 2014;120:3074–3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaldo A, Seal BS, Lage MJ. The cost of absenteeism and short-term disability associated with colorectal cancer: a case-control study. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56:848–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.