Abstract

Background

Pediatric sickle cell disease (SCD) management can result in considerable caregiver distress. Parents of youth with chronic SCD pain may face the additional challenge of managing children’s chronic pain and chronic illness. This study examined associations between parent psychological distress and child functioning and the moderating role of chronic pain among youth with SCD.

Methods

Youth presenting to pediatric outpatient comprehensive SCD clinics and their primary caregivers completed a battery of questionnaires. Parents reported on parenting stress, parent mental and physical health, and family functioning. Children completed measures of pain characteristics, depressive symptoms, catastrophic thinking, functional disability, and quality of life.

Results

Patients (N = 73, Mage = 14.2 years, 57% female) and their caregivers (Mage = 41.1 years, 88% mothers, 88% Black) participated. Worse parent functioning was associated with worse child pain, functioning, quality of life, and depressive symptoms. Beyond the effects of SCD, chronic SCD pain magnified the negative associations between parenting stress frequency and child quality of life, parent physical health and child quality of life, and parent depressive symptoms and child depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

Chronic pain may exacerbate the relations between parent and child functioning beyond the effects of SCD alone. The management of both SCD and chronic pain may present additional challenges for parents that limit their psychosocial functioning. Family-focused interventions to support parents and youth with chronic SCD pain are warranted to optimize health outcomes.

Keywords: chronic and recurrent pain, parent psychosocial functioning, parenting stress sickle cell disease

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a family of genetic blood disorders in which pain is the most prevalent complication. Although pain is the leading driver of healthcare use in the emergency and inpatient settings for SCD, most SCD pain is managed at home (Dampier et al., 2002). For parents, managing a child’s SCD can result in considerable stress as parents assume a majority of the responsibility for the child’s disease management (Oliver-Carpenter et al., 2011). Although parents play a significant role in how their children cope with SCD (Mitchell et al., 2007), parents also are personally affected by caring for a child with SCD. The challenges of managing SCD for children and parents might be even more difficult when the child has additional disease-related complications, such as chronic pain. Approximately 20% of adolescents and up to 40% of adults with SCD experience chronic pain, which typically increases in incidence and severity with age and can contribute to declines in overall quality of life and physical functioning, and increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms (Dampier et al., 2017; Sil et al., 2016a). To date, there is limited scientific knowledge of how managing pediatric SCD relates to parent psychological distress, and whether managing chronic pain in addition to SCD is an exacerbating factor of the association between parent distress and child functioning.

Drawing from Wallander and Varni’s (1998) theoretical model of child adjustment to pediatric chronic physical disorders, SCD can be conceptualized as an ongoing chronic stressor for both youth and their parents. Child and parent risk factors to child adjustment (i.e., physical and emotional functioning and overall quality of life) may include disease-related complications (e.g., disease severity) and psychosocial stress whereas resistance factors may include intrapersonal characteristics, cognitive appraisals of stress (e.g., child catastrophic thinking), or socio-ecological factors (e.g., family member’s adaptation and family functioning). Although parents’ distress is considered a normal response to a child’s chronic medical condition, even subclinical levels of distress can negatively impact a child’s emotional, physical, and family functioning and interfere with decision-making related to a child’s treatment (Palermo & Eccleston, 2009). Mothers of youth with SCD are likely to experience poor psychological adjustment related to perceived stress of daily hassles regardless of their child’s disease severity or sociodemographic characteristics (Thompson et al., 1993). The handful of studies focused on parental distress in youth with SCD indicate that increased frequency of parenting stress predicts greater healthcare utilization among children (Logan et al., 2002); difficulty of parenting stress also partially explains the negative impact of pain frequency on quality of life (Barakat et al., 2008). Parents of youth with SCD can also experience elevated emotional distress, such as high levels of catastrophic thinking that is associated with increased risk of child disability and depressive symptoms (Goldstein-Leever et al., 2018; Sil et al., 2016b). Despite the distress that can be related to SCD management, parents commonly reported a supportive family environment that persists over time (Thompson et al., 2003). The majority of these studies reported collectively on the SCD experience and did not highlight the potential unique contribution of chronic pain as an additional SCD complication.

Within Wallander and Varni’s (1998) framework, SCD-related complications such as chronic pain may serve as a risk factor for children’s physical and psychosocial functioning within which parent and family factors are intricately embedded. A deeper conceptualization of the socio-ecological framework integrating parent and family influences on pediatric chronic pain and disability suggests a reciprocal influence of child pain and disability with parent and family functioning (Palermo & Chambers, 2005; Palermo et al., 2014). In addition to managing SCD, parents of youth with chronic SCD pain may experience even greater distress as they manage their child’s chronic medical condition as well as chronic pain. Among youth not diagnosed with SCD but who have chronic pain, parents were found to have high parenting stress and were at elevated risk for physical and psychiatric disorders (Hunfeld et al., 2002). Parents of youth with non-SCD chronic pain were found to experience clinically significant caregiving stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms compared with parents of healthy children (Eccleston et al., 2004). Moreover, parents of adolescents most disabled by chronic pain reported clinically significant levels of stress, anxiety, and depression relative to parents of adolescents least disabled by chronic pain (Cohen et al., 2010), highlighting the possible compounding effects of chronic pain and illness. These parenting experiences may lead to changes in parents’ own psychological functioning, alter their parenting behaviors, and in turn, negatively influence the child’s adjustment to chronic pain and potentially SCD.

Substantial research on other chronic medical conditions, such as cancer or diabetes, consistently finds that reduced parent physical and psychosocial well-being predicts poorer child adjustment (e.g., Barlow & Ellard, 2006; Kazak & Drotar, 1997). Parents’ pre-existing psychological conditions and poor physical health were associated with reduced functioning and poorer psychological adjustment among their children. Recent meta-analyses in pediatric chronic pain indicated parent anxiety and depression were associated with increased child disability (Donnelly et al., 2020). Among pediatric pain populations, familial or parental history of chronic pain was observed at high rates and also predicted increased child pain and disability (Piira & Pullukat, 2006). In fact, systematic reviews suggest that children of parents with chronic pain evidence increased pain complaints, greater emotional and behavioral problems, poorer social competence, and poorer family functioning than children of parents without chronic pain (Higgins et al., 2015). Beyond the parent–child relationship, families of children with chronic pain generally have poorer family functioning than healthy populations (Palermo & Holley, 2013), and family functioning can impact pain-related disability (Lewandowski et al., 2010). These indications imply that the quality of parent and family functioning is likely intertwined with child functioning, making it critical to intervene with parents who are distressed to optimize both SCD and chronic pain management.

The primary study aim was to evaluate the associations between parent psychological distress and child adjustment among youth with SCD and the potential moderating role of child chronic pain. Worse parent psychosocial functioning (high parenting stress, more depressive and anxiety symptoms, worse physical functioning, and worse family functioning) was expected to be associated with reduced child functioning (higher functional disability, reduced quality of life, and higher depressive symptoms) after adjusting for relevant child and parent intrapersonal and clinical characteristics. Additionally, chronic SCD pain was expected to magnify the anticipated negative associations between parent psychological distress and child functioning among youth with SCD.

Materials and Methods

Recruitment

Participants included children and adolescents with SCD and their parents presenting to outpatient comprehensive SCD clinics at three campus locations of a tertiary care children’s hospital over 14 months. Youth were eligible if they had any SCD genotype, aged 8 to 18 years, and English-speaking. Exclusion criteria included significant documented cognitive or developmental disabilities or chronic transfusion therapy indicated for central nervous system (CNS) complications (e.g., stroke) that would interfere with survey completion, or comorbid medical condition in which pain is common (e.g., rheumatological or gastrointestinal conditions). Patients receiving chronic transfusion therapy for non-CNS related concerns (e.g., chronic pain management) were eligible for inclusion.

Study Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to study initiation. Patients were prescreened for eligibility and approached by trained research coordinators to introduce the study, assess eligibility, and provide in-depth explanation of the study to interested families. Families were approached in clinic or by phone. Parents and youth provided informed consent and assent. Web-based or pencil-and-paper measures were completed in clinic or at home. Participants received monetary compensation for participation time (about 30 minutes).

Measures

This study included a battery of parent-reported and child-reported measures related to psychosocial functioning. Some child-reported measures from this study were utilized to support preliminary validation of a pain screening measure (Sil et al., 2019) and has minimal overlap with the aims and objectives of this study focused on parent psychosocial functioning.

Primary Child Functioning Outcomes

Child Functional Disability. The Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) is a well-validated 15-item self-report of perceived difficulty performing daily activities across settings (Walker & Greene, 1991). Items are rated from 0 (no trouble) to 4 (impossible) and totaled (range 0–60). Established clinical reference points are 0–12 (no/minimal disability), 13–29 (moderate disability), and 30–60 (severe disability; Kashikar-Zuck et al., 2011). The FDI has demonstrated high internal consistency, moderate to high test–retest reliability, and good predictive validity (Walker & Greene, 1991). Internal reliability for this study sample was 0.96.

Child Health-Related Quality of Life. The Pediatric Quality of Life Sickle Cell Disease Module (PedsQL-SCD) is a well-validated 42-item measure that assesses 9 dimensions of health-related quality of life specific to SCD (Panepinto et al., 2013). Total scores (range 0–100) were used for analyses and higher scores are indicative of better quality of life. The PedsQL-SCD demonstrates excellent reliability and construct validity among patient self-report and has been widely used in pediatric SCD research (e.g., Connolly et al., 2019). Internal consistency in the sample was 0.96.

Child Depressive Symptoms. The Children’s Depression Inventory-2 is a well-validated 24-item self-report of depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks (Kovacs, 1992) frequently used in pediatric pain research (e.g., Eccleston et al., 2004). Total scores are transformed into T-scores based on patient age and sex, such that higher scores (T-scores ≥ 65) are indicative of elevated depressive symptoms. Internal reliability for the current sample was 0.90.

Parent and Family Functioning

Parenting Stress. The Pediatric Inventory for Parents (PIP) is a 42-item parent-report of the frequency and difficulty of stress experienced by parents of youth with chronic or acute illness (Lewin et al., 2005; Streisand et al., 2001). The PIP assesses parenting stress related to communication, emotional distress, medical care, and role function. Parents rated items on how often an event happens (frequency) and how difficult they perceive the event (difficulty). Total scores are calculated separately for frequency and difficulty (range 42–210); higher scores indicate greater frequency and difficulty of parenting stress. The PIP has demonstrated strong internal validity among parents of youth with chronic illness and was previously used in studies on pediatric SCD (Barakat et al., 2008; Barakat et al., 2007a; Logan et al., 2002). Internal reliability for this study sample was 0.97 for frequency and 0.97 for difficulty.

Parent Depressive Symptoms. Parents completed the Center for Epidemiological study—Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R-10), a 10-item self-report measure for adults of depressive symptoms in the past week. Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicative of greater depressive symptoms. Total scores ≥ 10 are considered clinically elevated levels of depression. The CESD-R-10 has demonstrated excellent internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity among the general adult population and adults with SCD (Laurence et al., 2006; Radloff, 1977). Internal reliability for this study sample was 0.72.

Parent Anxiety Symptoms. Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) is a 7-item self-report screening measure for adults on anxiety symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Total scores range from 0 to 21. Established clinical cut-points include: 5–9 (mild), 10–14 (moderate), and 15–21 (severe); total scores ≥ 10 are considered clinically elevated. The GAD-7 has demonstrated good sensitivity and specificity to diagnose generalized anxiety disorder and screen for other anxiety disorders among the general adult population (Spitzer et al., 2006). It has been used in prior research of adults with SCD (e.g., Jonassaint et al., 2018). Internal reliability for this sample was 0.90.

Parent Physical Health. Parents completed the Short Form 36 Health Survey—Version 2 (SF-36), a 36-item self-report for adults on general physical health in the past 4 weeks (Hays & Morales, 2001). The measure assesses 8 elements of health including: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, social functioning, general mental health, role limitations due to emotional problems, vitality, and general health. Subscales are used to calculate two composite summary scores: Physical Health and Mental Health. The Physical Health Composite summary score was used in analyses. Higher scores (range 0–100) are indicative of better functioning. The SF-36 has strong psychometric properties (Hays et al., 1995) and is useful in assessing physical health in the general adult population as well as SCD (Dampier et al., 2011). The internal reliability for this sample was 0.75.

Family Functioning. The family assessment device (FAD) is a well-established measure of family functioning among pediatric populations previously used with families of youth with SCD (Alderfer et al., 2008; Herzer et al., 2010). Parents completed the 12-item General Functioning subscale. Scores are summed and divided by the total number of items. Higher scores are indicative of worse family functioning. A clinical cutoff score ≥ 2 is indicative of “unhealthy” family functioning (Miller et al., 1985). The FAD General Functioning subscale demonstrated excellent internal consistency in previous studies (Alderfer et al., 2008). Internal reliability scores for this study sample were 0.85.

Child and Parent Intrapersonal and Clinical Characteristics

Demographics. Detailed demographic and background information, including patient and parent age, race, sex, annual family income, and common SCD treatments (i.e., disease-modifying therapies, such as hydroxyurea) was collected from parents. Additionally, parents were asked if they had been diagnosed with SCD (yes/no/not sure), and if so, what type of SCD. Parents also were asked if they had chronic pain (i.e., pain on most days lasting for more than 6 months; yes/no/not sure).

Child Pain Characteristics. Patients reported their average pain intensity over the last 2 weeks using a numeric rating scale (0 = no pain to 10 = worst possible pain). Patients reported the number of days they had pain in the past month (0–31 days) and for how long (i.e., duration) they experienced the current level of pain frequency on a 5-point Likert rating (1 = only this month to 5 = over 1 year); (Sil et al., 2016a). Per published diagnostic criteria, chronic SCD pain was defined as pain frequency ≥ 15 days per month with duration ≥ 6 months (Dampier et al., 2017).

Child Pain Catastrophizing. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale—Child is a well-validated 13-item questionnaire on thoughts and feelings about pain (Crombez et al., 2003) commonly used in pediatric pain samples (Pielech et al., 2014). Items are rated from 0 (mildly) to 4 (extremely). Higher total scores (0–52) reflect greater catastrophic thinking about pain. Established clinical reference points include: low (0–14), moderate (15–25), and high (≥ 26) (Pielech et al., 2014). Internal reliability for the current sample was 0.95.

Statistical Analyses

Data were entered into REDCap, a secure web application for online surveys and databases, and then exported into SPSS version 26 for analyses. Descriptive data on parent and child variables were computed to determine whether the data met the underlying assumptions of the proposed analytic procedures. Baseline characteristics of all participants who completed versus did not complete the study procedures were compared to ensure that there was no systematic source of bias due to selective attrition.

Bivariate correlations and univariate analysis of variance analyses were used to identify potential sociodemographic variables or clinical characteristics related to parent or child functioning relevant for inclusion as covariates in subsequent analyses. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were conducted among parent and family factors with child variables. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for each child functioning outcome (i.e., functional disability, quality of life, and depressive symptoms). Predictor variables were centered to aid in interpretation and interaction effects were probed using the data analytic techniques described by Hayes (2013). Due to multiple comparisons in this study, adjustments were made to control for spurious findings. Specifically, type-1 error inflation was controlled using the false discovery rate technique, which has demonstrated superior type-1 error rates and statistical power balance in comparison to Bonferroni correction (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 124 eligible participants were approached for the study, and 93 child–parent dyads consented (75% enrollment rate). The primary reason offered by families who did not consent (N = 26, 21%) was time constraints (e.g., expressed interest but unable to enroll because they arrived late to clinic). Five families (4%) declined participation. Of the 93 families who consented, 77 initiated study procedures (83% participation rate). The primary barrier to completing study procedures was completing and returning surveys after completing verbal consent by phone.

Four families had 100% missing data on all child-reported measures, and of these dyads, two also had 80% missing data on parent-reported measures; these four parent-child dyads were dropped from analyses. There were no significant differences between dyads who completed versus did not complete study procedures on parent or child age, sex, or race, child’s SCD genotype, parent’s marital status, or annual family income (all p’s > .16).

The final sample included 73 parent–child dyads. Patients were on average 14.2 years old (SD = 2.5), mostly female (57%), Black or African-American (88%), with hemoglobin type HbSS (73%), and prescribed hydroxyurea (78%). Parent reporters were on average 41.1 years old (SD = 7.7), primarily mothers (88%), and mostly Black or African-American (88%). About 19% (N = 15) of parents reported having SCD themselves, 33% (N = 24) reported having chronic pain, and 15% (N = 11) reported having both SCD and chronic pain (see Table I).

Table I.

Sample Characteristics (N = 73)

| Child | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | M = 14.24 | SD = 2.48 |

| Sex (female) | 57.3 | 43 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 88.3 | 68 |

| Multi-Racial | 2.6 | 2 |

| Caucasian | 1.3 | 1 |

| Other | 2.6 | 2 |

| Missing | 5.2 | 4 |

| Hemoglobin (Hb) type | ||

| HbSS | 72.7 | 56 |

| HbSC | 15.6 | 12 |

| HbS β+ Thalassemia | 9.1 | 7 |

| HbS β0 Thalassemia | 1.3 | 1 |

| HbSO-Arab | 1.3 | 1 |

| SCD treatments or complications | ||

| Hydroxyurea | 77.9 | 60 |

|

Chronic Transfusion Therapy |

14.3 |

11 |

|

Parent |

% |

N |

| Parent Reporter | ||

| Mother/stepmother | 88.3 | 68 |

| Father/stepfather | 5.2 | 4 |

| Legal guardian (e.g., aunt, grandmother) | 6.5 | 5 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 88.3 | 68 |

| Multi-racial | 9.1 | 7 |

| Hispanic | 1.3 | 1 |

| Other | 1.3 | 1 |

| Mean age (SD) | M = 41.1 | SD = 7.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/Partnered | 41.7 | 30 |

| Single | 33.3 | 24 |

| Divorced/separated | 20.8 | 15 |

| Widowed | 2.8 | 2 |

| Missing | 7.8 | 6 |

| Another caregiver in the home | 56.2 | 41 |

| Highest grade completeda | ||

| High School or less | 15.6 | 12 |

| Some college | 27.3 | 21 |

| College degree | 32.5 | 25 |

| Started graduate or professional school | 2.6 | 2 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 11.7 | 9 |

| Missing | 10.4 | 8 |

| Annual family income | ||

| ≤$10,000 | 2.6 | 2 |

| 10,001–20,000 | 23.4 | 18 |

| $20,001–30,000 | 14.3 | 11 |

| $30,001–50,000 | 19.5 | 15 |

| $50,001–75,000 | 11.7 | 9 |

| ≥$75,001 | 14.3 | 11 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2.6 | 2 |

| Missing | 11.7 | 9 |

| Parent SCD Diagnosis | ||

| Presence | 19.5 | 15 |

| Absence | 77.9 | 60 |

| Missing | 2.6 | 2 |

| Parent chronic pain history | ||

| Presence | 31.2 | 24 |

| Absence | 63.6 | 49 |

| Missing | 5.2 | 4 |

Some families filled out educational information for two parents, and thus percentages add to >100%.

Descriptive Analyses of Child, Parent, and Family Functioning

On average, youth with SCD reported mild pain intensity, moderate levels of catastrophic thinking of pain, moderate levels of functional disability, health-related quality of life within the average range, and depressive symptoms within normal range (see Table II). Based on SCD chronic pain diagnostic criteria (Dampier et al., 2017), 32 (43.8%) patients reported chronic pain (i.e., ≥ 15 days of pain per month, lasting ≥ 6 months) and 41 (56.2%) patients reported episodic pain. Patients with chronic pain reported an average of 17.2 pain days in the past month, of which most patients with chronic pain (N = 17, 53%) reported that chronic pain persisted for over 1 year. Patients with episodic pain reported an average of 2.6 pain days (SD = 2.6) in the past month. Additionally, youth with chronic SCD pain reported significantly higher average pain intensity (M = 5.4, SD = 2.3) than youth with episodic pain (M = 1.8, SD = 2.3; t = −6.73, p < .001).

Table II.

Means (M), Standard Deviations (SDs), and Correlations Among Parent Functioning and Child Functioning (N = 73)

| Child functioning |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent functioning | M (SD) | Pain intensity | Pain catastrophizing | Functional disability | Health-related quality of lifea | Depressive symptoms |

| Parenting stress frequency | 99.20 (36.16) | 0.46*** | 0.27* | 0.42*** | −0.40*** | 0.43*** |

| Parenting stress difficulty | 84.88 (36.70) | 0.36** | 0.32** | 0.34** | −0.40*** | 0.31** |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.39 (6.32) | 0.32** | 0.22 | 0.34** | −0.26* | 0.13 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 4.65 (4.89) | 0.26* | 0.17 | 0.26* | −0.25* | 0.23 |

| Physical health compositea | 48.22 (10.19) | −0.25* | −0.27* | −0.32* | 0.26* | −0.23 |

| Family functioning | 1.57 (0.49) | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.24* | 0.06 |

| M (SD) | 3.38 (2.93) | 23.76 (13.29) | 15.33 (14.19) | 57.01 (21.33) | 54.95 (11.26) | |

Indicates constructs where higher scores represent better functioning.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

On average, parents of youth with SCD reported parenting stress frequency and difficulty, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and physical health within normative ranges (see Table II). The sample reported family functioning falling within the healthy range. Regarding clinical cutoffs for parent depression, anxiety, and family functioning, about 40% (N = 29) of parents reported clinically elevated depression scores, 16% (N = 12) of parents reported clinically elevated anxiety scores, and 22% reported “unhealthy” family functioning.

Associations Between Parent and Child Functioning

There were no significant associations among child age, sex, genotype, SCD treatments (i.e., hydroxyurea, chronic transfusion therapy), parent age, parent marital status, parent highest education level, or parent history of having SCD themselves with child functioning, parent distress, or family functioning variables (all p’s > .30). However, child pain intensity and pain catastrophizing were significantly associated with child functioning outcomes (all r’s ≥ .38, p’s < .001) and parent distress variables (all r’s ≥ .25, p’s < .05). Annual family income was significantly associated with child functional disability (r = .46, p < .001), child quality of life (r = −.49, p < .001), parent depressive symptoms (r = −.33, p < .01), and parent physical health (r = .39, p < .001). Parent history of chronic pain was significantly associated with higher parenting stress frequency (F = 6.91, p < .01) and difficulty (F = 9.80, p < .01), parent depressive symptoms (F = 6.95, p < .01), parent physical health (F = 21.37, p < .001), child pain intensity (F = 6.70, p < .05), child depressive symptoms (F = 6.89, p < .01), child pain catastrophizing (F = 4.50, p < .05), and child functional disability (F = 5.33, p < .05). Therefore, annual family income, parent history of chronic pain, child pain intensity, and child pain catastrophizing were included as covariates in subsequent analyses.

As shown in Table II, there were significant, small to moderate associations between child pain intensity, catastrophic thinking, and functioning outcomes with parenting stress, parent mental health, and parent physical health (all r’s ≤ 0.46, p’s < .05). Notably, higher parenting stress frequency and difficulty were consistently associated with worse child functioning. Higher parent depressive and anxiety symptoms were related to higher child pain intensity, higher functional disability, and worse quality of life. Worse parent physical health was associated with worse child pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, functional disability, and quality of life. Last, worse family functioning was related to worse child quality of life.

Child Chronic Pain as a Moderator of Parent and Child Functioning

Three separate multiple regression analyses were conducted to investigate the unique relations between parent distress and child functioning and whether child chronic pain status strengthened the relation between parent distress and child functioning. First, annual family income, parent history of chronic pain, child pain intensity, and child pain catastrophizing were entered as covariates along with child chronic pain status. Second, parenting stress frequency and difficulty, parent depression, parent anxiety, parent physical health, and family functioning were entered into the model. Last, interaction terms for child chronic pain and each parent distress variable were included.

Functional Disability

Examination of child chronic pain as a moderator of the relations between parent distress and child functional disability revealed that the overall model was significant, F (17, 62) = 5.49, p < .001, accounting for 67.5% of the variance in functional disability (see Table III). Child pain intensity and child pain catastrophizing uniquely predicted child functional disability, but no parent or family functioning variables were significantly associated with child functional disability. Child chronic pain was not a significant moderator of the association between parent distress and child functional disability.

Table III.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis Examining the Moderating Effect of Child Chronic Pain on the Relation Between Parent Distress and Child Functional Disability, Quality of Life, And Depressive Symptoms, Separately

| Functional disability |

Quality of life |

Depressive symptoms |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Predictor | b | SE b | β | b | SE b | β | b | SE b | β |

| 1 | Annual income | −0.76 | 0.81 | −0.10 | 0.66 | 0.94 | 0.06 | −0.04 | 0.75 | −0.01 |

| Parent chronic pain | −3.67 | 3.49 | −0.13 | 10.40 | 4.03 | 0.23 * | 3.41 | 3.24 | 0.15 | |

| Child pain intensity | 2.34 | 0.61 | 0.50 ** | −1.93 | 0.70 | −0.27 * | 0.16 | −0.56 | 0.05 | |

| Child pain catastrophizing | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.25 * | −0.91 | 0.13 | −0.58 ** | 0.37 | 0.10 | 0.48 ** | |

| Child chronic pain | −2.87 | 3.59 | −0.10 | 1.94 | 4.16 | 0.05 | −0.95 | 3.34 | −0.05 | |

| 2 | Parenting stress frequency | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.49 |

| Parenting stress difficulty | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −0.24 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.13 | |

| Parent depression | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.19 | −0.08 | 0.44 | −0.03 | −0.73 | 0.35 | −0.45 | |

| Parent anxiety | 0.19 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.57 | 0.45 | 0.27 | |

| Parent physical health | −0.57 | 0.28 | −0.40 | 1.02 | 0.32 | 0.46 * | −0.25 | 0.26 | −0.23 | |

| Family functioning | −12.70 | 4.95 | −0.46 | −.57 | 5.73 | −0.04 | −1.19 | 4.60 | −0.06 | |

| 3 | Child chronic pain × Parenting stress frequency | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.18 | −0.41 | 0.13 | −0.47 ** | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.05 |

| Child chronic pain × Parenting stress difficulty | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.05 | |

| Child chronic pain × Parent depression | −0.09 | 0.59 | −0.03 | −0.17 | 0.68 | −0.03 | 1.29 | 0.55 | 0.52 * | |

| Child chronic pain × Parent anxiety | −0.83 | 0.70 | −0.24 | 0.17 | 0.81 | 0.03 | −0.99 | 0.65 | −0.37 | |

| Child chronic pain × Parent physical health | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.24 | −1.23 | 0.35 | −0.45 ** | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.33 | |

| Child chronic pain × Family functioning | 13.01 | 6.38 | 0.38 | −4.22 | 7.38 | −0.08 | −3.39 | 5.93 | −0.13 | |

Note. Regression coefficients reflect values for the final model. p-values reflect use of false discovery rate Type-1 error control for all comparisons.

p < .05;

p < .01.

Health-Related Quality of Life

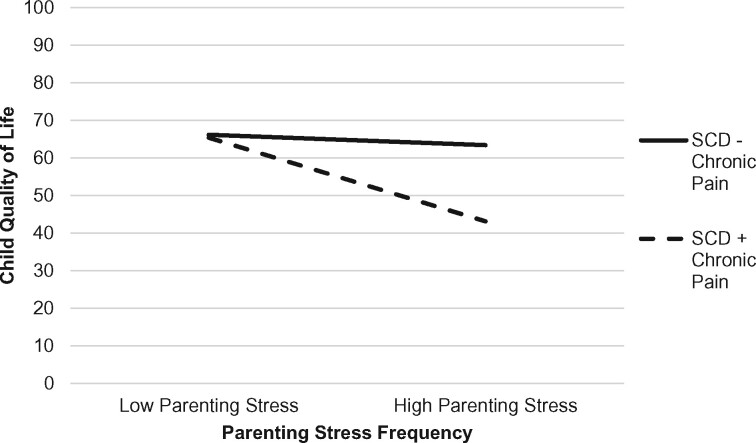

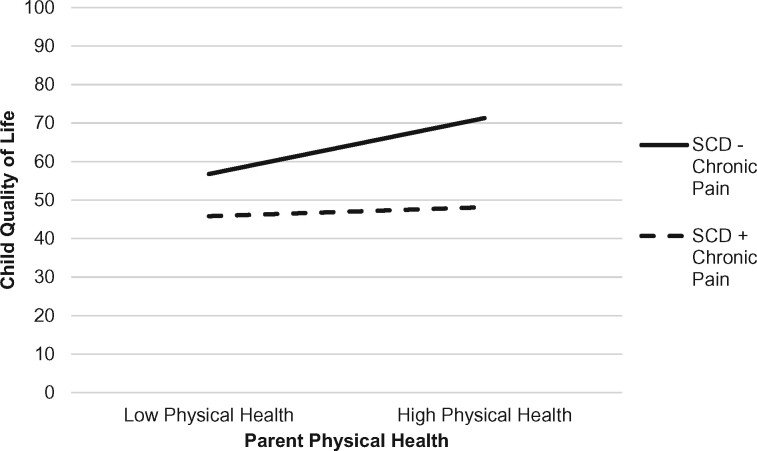

As depicted in Table III, the overall multiple regression model examining the moderating effect of child chronic pain on the association between parent distress and child health-related quality of life was significant, F (17, 62) = 11.91, p < .001, accounting for 81.8% of the variance in quality of life. Parent history of chronic pain, child pain intensity, child pain catastrophizing, and parent physical health were unique predictors of child quality of life. Significant two-way interactions emerged between child chronic pain and parenting stress frequency as well as child chronic pain and parent physical health in predicting child quality of life. The nature of the interaction effects was examined by plotting regression lines for patients with high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of parenting stress frequency and parent physical health, separately. As shown in Figure 1, the presence of chronic pain in addition to SCD exacerbated the relation between parenting stress frequency and child quality of life. Specifically, for youth with SCD and chronic pain, higher parenting stress frequency was associated with worse child quality of life (b = −20.25, t = −3.07, p < .001, f2 = 0.14). In contrast, for youth with SCD without chronic pain, the association between parenting stress frequency and child quality of life did not vary (b = −0.77, t = −0.09, p = .93). Regarding parent physical health (see Figure 2), for youth with SCD without chronic pain, worse parent physical health was associated with worse child quality of life (b = −23.13, t = −3.39, p < .001, f2 = .18). The association between parent physical health and child quality of life did not vary for youth with SCD and chronic pain (b = −0.77, t = −0.09, p = .93).

Figure 1.

Interaction effect with child chronic pain (presence/absence) as a moderator of parenting stress frequency and child health-related quality of life.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect with child chronic pain (presence/absence) as a moderator of parent physical health and child health-related quality of life.

Child Depressive Symptoms

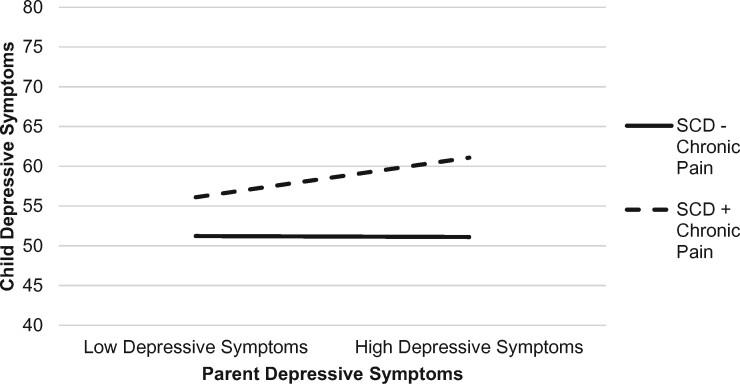

The overall model evaluating the moderating effect of child chronic pain on the relations between parent distress and child depressive symptoms was significant, F (17, 62) = 2.88, p < .01, accounting for 52.1% of the variance in child depressive symptoms (see Table III). Child pain catastrophizing uniquely predicted child depressive symptoms. A significant interaction emerged between child chronic pain and parent depression. As illustrated in Figure 3, the addition of chronic pain on top of SCD for youth strengthened the association between parent and child depression. Specifically, for youth with SCD and chronic pain, higher levels of parent depressive symptoms were associated with higher levels of child depressive symptoms (b = 9.99, t = 2.98, p < .01, f2 = 0.13). In contrast, the relation between child and parent depression did not vary for youth with SCD without chronic pain (b = 4.89, t = 1.40, p = .17).

Figure 3.

Interaction effect with child chronic pain (presence/absence) as a moderator of parent depressive symptoms and child depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Data from studies of pediatric chronic illness and chronic pain populations suggest parent distress can negatively impact child functioning; however, the influence of parent psychosocial distress on the functioning of children and adolescents with SCD has been sparse to date and largely neglects to consider the potential added burden of chronic SCD pain. This study findings extend the few studies on parent psychosocial distress in pediatric SCD and further support associations among parenting stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and physical health, with child psychosocial and functional outcomes. To support the growing literature on chronic SCD pain, this study sheds light on how chronic pain may exacerbate the relation between parent functioning and child functioning beyond the effects of SCD alone.

The primary study objective examined associations between psychosocial distress among parents of youth with SCD and child functioning. Multiple aspects of parent functioning including parenting stress, parent depressive and anxiety symptoms, and parent physical health were associated with child pain, functioning, depressive symptoms, and quality of life with small to medium effect sizes. This is consistent with findings of previous studies indicating a relationship between caregivers’ distress and youth’s disease-related outcomes (Barakat et al., 2007b, 2008). Even after accounting for relevant covariates, study results suggest that some associations between parent psychological functioning and child functioning were strengthened within the context of chronic SCD pain. Specifically, relations between higher parenting stress frequency and worse child quality of life, worse parent physical health and worse child quality of life, and higher parent depressive symptoms and higher child depressive symptoms were exacerbated for youth with SCD and chronic pain. It is possible that the additional aspects of managing chronic pain on top of managing SCD contribute to greater parenting distress. For example, parents may have to navigate and monitor the integration of new or additional medications, multiple clinic visits or hospitalizations for chronic pain, or disruptions in daily routines such as missed school and work that may exacerbate stress already experienced within the context of disease management. This is consistent with literature that suggests parents of non-SCD adolescents with considerable chronic pain-related disability experience clinically significant parenting stress (Cohen et al., 2010]). Parents’ own chronic pain also increases children’s risk for chronic pain and adverse outcomes, such as disability or poor psychosocial functioning, with even stronger parent–child associations when both parents reported chronic pain (Stone & Wilson, 2016). Beyond the effects of parents’ own chronic pain, parents’ poor physical and mental health may further contribute to increased risk of adverse child functioning (Armistead et al., 1995). Youth with SCD may be vulnerable to developing chronic pain and adverse outcomes within the context of parent chronic pain or illness due to a combination of factors, such as genetic predisposition, neurobiological pathways, social learning (e.g., parental modeling of pain behaviors), general parenting, and exposure to a stressful environment (Stone & Wilson, 2016).

The connection between parent distress and child functioning could be due to a perceived imbalance of demands and resources, given that parents of youth with SCD report greater perceived burden of care than caregivers of healthy children (Moskowitz et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, parents of children with SCD spend significantly more time in technical care and crisis care activities than caregivers of healthy children (Moskowitz et al., 2007). Unplanned hospitalizations are disruptive and straining on normal routines and responsibilities, potentially leading to parenting behaviors and anxiety that unintentionally reinforce poor child functioning (Bioku et al., 2020). Parents of children with SCD report high levels of depressed mood, increased emotional distress toward having a child with SCD and managing their child’s emotional distress, and most perceive helping their children cope with pain to be challenging and emotionally distressing (Ievers-Landis et al., 2001; Moskowitz et al., 2007; Wesley et al., 2016). Family functioning can be negatively impacted by greater disease severity and healthcare utilization among adolescents with SCD, which may be complicated by increased adolescent autonomy of their disease management with age (Barakat et al., 2007b). Thus, evolving family member roles and responsibilities as youth progress through adolescence may also exacerbate parental distress and contribute to poorer youth outcomes.

When compared with the extant literature on parents of youth with chronic illness and chronic pain, this sample of parents of youth with SCD appear to demonstrate relatively lower levels of parenting stress (Goubert et al., 2006; Streisand et al., 2001), better family functioning (Hayaki et al., 2016; Herzer et al., 2010), comparable levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (Brehaut et al., 2009; Lalouni et al., 2017), and worse physical health (Benjamin et al., 2019; Klassen et al., 2008). Notably, this sample included families with somewhat higher parent education levels (i.e., college or graduate degrees) relative to other studies of pediatric SCD (e.g., Barakat et al., 2008; Bioku et al., 2020). Although parent education level was not significantly related to parent functioning among this sample, lower parent educational attainment and income have been connected to higher parenting stress (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). Additional work is needed to comprehensively evaluate the socio-ecological contributors to parenting stress in pediatric SCD.

Parent and family factors have been identified as essential for understanding how to effectively intervene with childhood chronic pain conditions (e.g., abdominal or back pain, headache, widespread musculoskeletal pain) (Palermo, 2000). Child-focused interventions may fail to recognize that children function within a larger system and social context, in which the role of family, parents, and parenting behavior are crucial to better understanding the experience and consequence of youth’s pain (Palermo & Chambers, 2005). Although parents are often included in psychological therapies for children, parent-focused interventions such as parent support groups (Chernoff et al., 2002), parent mindfulness training (Minor et al., 2006), and parent problem-solving skills training (Eccleston et al., 2012) can improve child adjustment and reduce stress and mental health concerns experienced by parents of youth with various chronic illness and warrant further development and investigation in SCD.

Study findings should be interpreted within the context of a few limitations. First, the cross-sectional study design limits the ability to draw any causal inferences of the role of chronic SCD pain on parent psychosocial distress or child functioning. Results from this study will require additional investigation within a well-powered longitudinal design and comparison groups to test a predictive, causal model. Additionally, parent psychosocial distress was primarily reflective of maternal reports given the low frequency of study participation by a second parent or caregiver. The potential similarities or differences in family dynamics as reported by a second caregiver or possible dyadic influences on parent or child functioning remain largely unknown. Future examination of biopsychosocial factors, such as concerns of opioid use for chronic pain that may contribute to high parenting stress among parents of youth with chronic SCD pain is warranted to help identify parents who may be at risk for experiencing high parental distress. Future studies focused on systematically identifying parents’ risk for psychological distress may also facilitate improved and targeted parent interventions that further support improved child outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and families for their time and participation in this research. Special thanks are also extended to the clinical research coordinators for their time and effort in supporting the study: Farida Abudulai, Morgan Barnett, Shelley Mays, Natasha Morris, Bailey Sturdivant, and Amanda Watt.

Funding

Funding for this study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the NIH under Award UL1TR000454. Preparation of this paper was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Award 1K23Hl133457-01A1 to S.S., PhD. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: SS, KEW, YLJ, and LLC have no conflicts of interest to report. CD has research funding from Pfizer, Micelle BioPharma, Novartis, Merck, Katz Foundation, and NIH/NICHD/NCATS; he is a consultant for Pfizer, Novartis, Global Blood Therapeutics, Epizyme, Micelle BioPharma, Modus Therapeutics, Hilton Publishing Company, and Ironwood Pharmaceutics; and he is on the advisory board of Pfizer, Novartis, and Micelle BioPharma.

References

- Alderfer M. A., Fiese B. H., Gold J. I., Cutuli J. J., Holmbeck G. N., Goldbeck L., Chambers C. T., Abad M., Spetter D., Patterson J. (2008). Evidence-based Assessment in Pediatric Psychology: Family Measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33(9), 1046–1061. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armistead L., Klein K., Forehand R. (1995). Parental physical illness and child functioning. Clinical Psychology Review, 15(5), 409–422. 10.1016/0272-7358(95)00023-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L., Patterson C., Daniel L. C., Dampier C. (2008). Quality of life among adolescents with sickle cell disease: Mediation of pain by internalizing symptoms and parenting stress. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6(1), 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L., Patterson C., Tarazi R. A., Ely E. (2007a). Disease-related parenting stress in two sickle cell disease caregiver samples: Preschool and adolescent. Families, Systems, & Health, 25(2), 147–161. 10.1037/1091-7527.25.2.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L., Patterson C., Weinberger B. S., Simon K., Gonzalez E. R., Dampier C. (2007b). A prospective study of the role of coping and family functioning in health outcomes for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 29(11), 752–760. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318157fdac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J. H., Ellard D. R. (2006). The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: An overview of the research evidence base. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(1), 19–31. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00591.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin J. Z., Harbeck-Weber C., Sim L. (2019). Pain is a family matter: Quality of life in mothers and fathers of youth with chronic pain. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(3), 440–447. 10.1111/cch.12662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bioku A. A., Ohaeri J. U., Oluwaniyi S. O., Olagunju T. O., Chaimowitz G. A., Olagunju A. T. (2020). Emotional distress among parent caregivers of adolescents with sickle cell disease: Association with patients and caregivers variables. Journal of Health Psychology. 10.1177/1359105320935986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehaut J. C., Kohen D. E., Garner R. E., Miller A. R., Lach L. M., Klassen A. F., Rosenbaum P. L. (2009). Health among caregivers of children with health problems: Findings from a Canadian population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 99(7), 1254–1262. 10.2105/ajph.2007.129817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff R. G., Ireys H. T., DeVet K. A., Kim Y. J. (2002). A Randomized, controlled trial of a community-based support program for families of children with chronic illness: Pediatric outcomes. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(6), 533–539. 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. L., Vowles K. E., Eccleston C. (2010). Parenting an adolescent with chronic pain: An investigation of how a taxonomy of adolescent functioning relates to parent distress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(7), 748–757. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger R. D., Donnellan M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 175–199. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly M. E., Bills S. E., Hardy S. J. (2019). Neurocognitive and psychological effects of persistent pain in pediatric sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 66(9), e27823. 10.1002/pbc.27823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez G., Bijttebier P., Eccleston C., Mascagni T., Mertens G., Goubert L., Verstraeten K. (2003). The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): A preliminary validation. Pain, 104(3), 639–646. 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00121-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C., Ely E., Brodecki D., O’Neal P. (2002). Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: A daily diary study in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 24(8), 643–647. http://journals.lww.com/jpho-online/Fulltext/2002/11000/Home_Management_of_Pain_in_Sickle_Cell_Disease__A.8.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C., LeBeau P., Rhee S., Lieff S., Kesler K., Ballas S., Rogers Z., Wang W.; the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers (CSCC) Clinical Trial Consortium (CTC) Site Investigators. (2011). Health-related quality of life in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD): A report from the comprehensive sickle cell centers clinical trial consortium. American Journal of Hematology, 86(2), 203–205. 10.1002/ajh.21905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampier C., Palermo T. M., Darbari D. S., Hassell K., Smith W., Zempsky W. (2017). AAPT diagnostic criteria for chronic sickle cell disease pain. Journal of Pain, 18(5), 490-498. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly T. J., Palermo T. M., Newton-John T. R. O. (2020). Parent cognitive, behavioural, and affective factors and their relation to child pain and functioning in pediatric chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 161(7), 1401–1419. https://journals.lww.com/pain/Fulltext/2020/07000/Parent_cognitive,_behavioural,_and_affective.2.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. E., Drotar D. (1997). Relating parent and family functioning to the psychological adjustment of children with chronic health conditions: What have we learned? What do we need to know? Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(2), 149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C., Crombez G., Scotford A., Clinch J., Connell H. (2004). Adolescent chronic pain: Patterns and predictors of emotional distress in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents. Pain, 108(3), 221–229. 10.1016/j.pain.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston C., Palermo T. M., Fisher E., Law E. (2012). Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online), 8, CD009660. 10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein-Leever A., Cohen L. L., Dampier C., Sil S. (2018). Parent pain catastrophizing predicts child depressive symptoms in youth with sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 65(7), e27027. 10.1002/pbc.27027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubert L., Eccleston C., Vervoort T., Jordan A., Crombez G. (2006). Parental catastrophizing about their child’s pain. The parent version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-P): A preliminary validation. Pain, 123(3), 254–263. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki C., Anno K., Shibata M., Iwaki R., Kawata H., Sudo N., Hosoi M. (2016). Family dysfunction: A comparison of chronic widespread pain and chronic localized pain. Medicine (Baltimore), 95(49), e5495. 10.1097/md.0000000000005495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hays R. D., Morales L. S. (2001). The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 350–357. 10.3109/07853890109002089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays R. D., Sherbourne C. D., Mazel R. M. (1995). User’s manual for the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) core measures of health-related quality of life. Rand Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Herzer M., Godiwala N., Hommel K. A., Driscoll K., Mitchell M., Crosby L. E., Piazza-Waggoner C., Zeller M. H., Modi A. C. (2010). Family functioning in the context of pediatric chronic conditions. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 31(1), 26–34. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c7226b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins K. S., Birnie K. A., Chambers C. T., Wilson A. C., Caes L., Clark A. J., Lynch M., Stinson J., Campbell-Yeo M. (2015). Offspring of parents with chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of pain, health, psychological, and family outcomes. Pain, 156(11), 2256–2266. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunfeld J. A. M., Perquin C. W., Hazebroek-Kampschreur A. A. J. M., Passchier J., Suijlekom-Smit L. W. A., Wouden J. C. (2002). Physically unexplained chronic pain and its impact on children and their families: The mother’s perception. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 75(3), 251–260. 10.1348/147608302320365172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ievers-Landis C. E., Brown R. T., Drotar D., Bunke V., Lambert R. G., Walker A. A. (2001). Situational analysis of parenting problems for caregivers of children with sickle cell syndromes. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 22(3), 169–178. 10.1097/00004703-200106000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassaint C. R., Kang C., Prussien K. V., Yarboi J., Sanger M. S., Wilson J. D., De Castro L., Shah N., Sarkar U. (2018). Feasibility of implementing mobile technology-delivered mental health treatment in routine adult sickle cell disease care. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(1), 58-67. 10.1093/tbm/iby107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashikar-Zuck S., Flowers S. R., Claar R. L., Guite J. W., Logan D. E., Lynch-Jordan A. M., Palermo T. M., Wilson A. C. (2011). Clinical utility and validity of the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI) among a multicenter sample of youth with chronic pain. Pain, 152(7), 1600–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen A. F., Klaassen R., Dix D., Pritchard S., Yanofsky R., O'Donnell M., Scott A., Sung L. (2008). Impact of caring for a child with cancer on parents’ health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26(36), 5884–5889. 10.1200/jco.2007.15.2835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory. Multi-Health Systems Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lalouni M., Ljotsson B., Bonnert M., Hedman-Lagerlof E., Hogstrom J., Serlachius E., Olen O. (2017). Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for children with pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: Feasibility Study. JMIR Mental Health, 4(3), e32. 10.2196/mental.7985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence B., George D., Woods D. (2006). Association between elevated depressive symptoms and clinical disease severity in african-american adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(3), 365–369. https://login.proxy.library.emory.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2006-21975-002&site=ehost-live&scope=siteblaurenc@yahoo.com [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski A. S., Palermo T. M., Stinson J., Handley S., Chambers C. T. (2010). Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. The Journal of Pain, 11(11), 1027–1038. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin A. B., Storch E. A., Silverstein J. H., Baumeister A. L., Strawser M. S., Geffken G. R. (2005). Validation of the pediatric inventory for parents in mothers of children with type 1 diabetes: An examination of parenting stress, anxiety, and childhood psychopathology. Families, Systems, & Health, 23(1), 56–65. 10.1037/1091-7527.23.1.56 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan D. E., Radcliffe J., Smith-Whitley K. (2002). Parent factors and adolescent sickle cell disease: Associations with patterns of health service use. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(5), 475–484. 10.1093/jpepsy/27.5.475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I. W., Epstein N. B., Bishop D. S., Keitner G. I. (1985). The McMaster family assessment device: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 11(4), 345–356. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1985.tb00028.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minor H. G., Carlson L. E., Mackenzie M. J., Zernicke K., Jones L. (2006). Evaluation of a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Program for Caregivers of Children with Chronic Conditions. Social Work in Health Care, 43(1), 91–109. 10.1300/J010v43n01_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M. J., Lemanek K., Palermo T. M., Crosby L. E., Nichols A., Powers S. W. (2007). Parent perspectives on pain management, coping, and family functioning in pediatric sickle cell disease. Clinical Pediatrics, 46(4), 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz J. T., Butensky E., Harmatz P., Vichinsky E., Heyman M. B., Acree M., Wrubel J., Wilson L., Folkman S. (2007). Caregiving time in sickle cell disease: Psychological effects in maternal caregivers. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 48(1), 64–71. 10.1002/pbc.20792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Carpenter G., Barach I., Crosby L. E., Valenzuela J., Mitchell M. J. (2011). Disease management, coping, and functional disability in pediatric sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103(2), 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T. M. (2000). Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 21(1), 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T. M., Chambers C. T. (2005). Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain, 119(1–3), 1–4. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T. M., Eccleston C. (2009). Parents of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain, 146(1–2), 15–17. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T. M., Holley A. (2013). The importance of the family environment in pediatric chronic pain. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(1), 93–94. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo T. M., Valrie C. R., Karlson C. W. (2014). Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: A developmental perspective. American Psychologist, 69(2), 142–152. 10.1037/a0035216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panepinto J. A., Torres S., Bendo C. B., McCavit T. L., Dinu B., Sherman-Bien S., Bemrich-Stolz C., Varni J. W. (2013). PedsQL sickle cell disease module: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 60(8), 1338–1344. 10.1002/pbc.24491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pielech M., Ryan M., Logan D., Kaczynski K., White M. T., Simons L. E. (2014). Pain catastrophizing in children with chronic pain and their parents: Proposed clinical reference points and reexamination of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale measure. Pain, 155(11), 2360–2367. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.08.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piira T., Pullukat R. (2006). Are the children of chronic pain patients more likely to develop pain? Enfance, 58(1), 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sil S., Cohen L. L., Dampier C. (2016a). Psychosocial and functional outcomes in youth with chronic sickle cell pain. Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(6), 527–533. 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil S., Cohen L. L., Dampier C. (2019). Pediatric pain screening identifies youth at risk of chronic pain in sickle cell disease. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 66(3), e27538. 10.1002/pbc.27538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil S., Dampier C., Cohen L. L. (2016b). Pediatric sickle cell disease and parent and child catastrophizing. The Journal of Pain, 17(9), 963–971. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R. L., Kroenke K., Williams J. B., Lowe B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone A. L., Wilson A. C. (2016). Transmission of risk from parents with chronic pain to offspring: An integrative conceptual model. Pain, 157(12), 2628–2639. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streisand R., Braniecki S., Tercyak K. P., Kazak A. E. (2001). Childhood illness-related parenting stress: The pediatric inventory for parents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26(3), 155–162. 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. J., Armstrong F. D., Link C. L., Pegelow C. H., Moser F., Wang W. C. (2003). A prospective study of the relationship over time of behavior problems, intellectual functioning, and family functioning in children with sickle cell disease: A report from the cooperative study of sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28(1), 59–65. 10.1093/jpepsy/28.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. J., Gil K. M., Burbach D. J., Keith B. R., Kinney T. R. (1993). Psychological adjustment of mothers of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: The role of stress, coping methods, and family functioning. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 18(5), 549–559. 10.1093/jpepsy/18.5.549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. S., Greene J. W. (1991). The functional disability inventory: Measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 16(1), 39–58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=1826329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander J. L., Varni J. W. (1998). Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(1), 29–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley K. M., Zhao M., Carroll Y., Porter J. S. (2016). Caregiver perspectives of stigma associated with sickle cell disease in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31(1), 55–63. 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]