Abstract

Background

A paucity of research addresses breast cancer screening strategies for women at lower-than-average breast cancer risk. The aim of this study was to examine screening harms and benefits among women aged 50-74 years at lower-than-average breast cancer risk by breast density.

Methods

Three well-established, validated Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Network models were used to estimate the lifetime benefits and harms of different screening scenarios, varying by screening interval (biennial, triennial). Breast cancer deaths averted, life-years and quality-adjusted life-years gained, false-positives, benign biopsies, and overdiagnosis were assessed by relative risk (RR) level (0.6, 0.7, 0.85, 1 [average risk]) and breast density category, for US women born in 1970.

Results

Screening benefits decreased proportionally with decreasing risk and with lower breast density. False-positives, unnecessary biopsies, and the percentage overdiagnosis also varied substantially by breast density category; false-positives and unnecessary biopsies were highest in the heterogeneously dense category. For women with fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density and a relative risk of no more than 0.85, the additional deaths averted and life-years gained were small with biennial vs triennial screening. For these groups, undergoing 4 additional screens (screening biennially [13 screens] vs triennially [9 screens]) averted no more than 1 additional breast cancer death and gained no more than 16 life-years and no more than 10 quality-adjusted life-years per 1000 women but resulted in up to 232 more false-positives per 1000 women.

Conclusion

Triennial screening from age 50 to 74 years may be a reasonable screening strategy for women with lower-than-average breast cancer risk and fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density.

There is general consensus that biennial screening from ages 50-74 years is effective in reducing breast cancer mortality and has a favorable balance between benefits and harms (1-3). Risk-based screening has been proposed to improve the efficiency of screening, because it has the potential to lead to a more favorable harm to benefit ratio at the population level (4). Most studies of risk-based screening have focused on women at increased risk (5-7) for whom more intense screening than biennial might be considered. Few studies have assessed the harms and benefits for women at decreased risk (lower than average, ie, a relative risk [RR] < 1). Women with lower-than-average risk of breast cancer are expected to have a less favorable harm to benefit ratio from untargeted screening, suggesting that less intense screening strategies than biennial screening might be appropriate for this group.

The proportion of women at low risk in the population is substantial; for example, 34% of US women aged 40-74 years have a 5-year risk of developing breast cancer below 1.00% based on the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) risk model (8,9). Established factors that are associated with substantially decreased risk for breast cancer include fatty breasts, young age at first birth (younger than 20 years), and young age at menopause (younger than 40 years) with relative risks of 0.6-0.7 (10-12); these factors apply to 8%, 12%, and 13% of US women, respectively (10,11). Factors associated with a more modest decrease in risk, such as 3 or 4 full pregnancies (RR = 0.84) and age at menopause between 45 and 49 years (RR = 0.86) (12,13), are even more common, with 39% and 24% of US women aged 50-79 years reporting those factors, respectively (11).

Breast density has also received attention as an important factor that influences risk of developing breast cancer, as well as affecting the balance between benefits and harms of screening, because low breast density not only leads to a reduced risk for developing disease but also increases the sensitivity of mammography (9,10,14). The aim of this study was to assess the benefits and harms of screening by breast cancer risk, breast density, and screening interval among women aged 50-74 years with lower-than-average risk levels using collaborative modeling. Study results are intended to inform discussions about risk-based screening guidelines and practice.

Methods

Model Overview

We used 3 well-established microsimulation models developed independently as part of the National Cancer Institute–funded Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network consortium: model E (15), model GE (16), and model W (see Table 1) (17). These models have been validated previously (19), have been shown to replicate US population trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality (20,21), and have been used extensively to estimate the impact of different screening scenarios (22‐25). The models and common inputs have been described in detail previously (15‐18,26) (Supplementary Methods, available online).

Table 1.

Summary of model featuresa

| Feature | Model E | Model GE | Model W |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural history of cancer | Continuous tumor growth | Stage transition | Continuous tumor growth |

| Details on natural history | Variation in growth rates, includes slow- and fast-growing tumors with varying fatal diameters | All lesions begin as DCIS and can evolve through AJCC-6 stages; variation in dwell times in each stage | Variation in growth rates from nonprogressive disease to hyperaggressive tumors |

| Tumors obligated to progress | DCIS nonobligate; invasive obligate | DCIS nonobligate; invasive obligate | DCIS and some small invasive are nonobligate; larger invasive obligate |

| SEER breast cancer data used for model calibration (1975-2010) | Incidence, stage distribution, mortality | Incidence, stage distribution | Incidence and mortality |

| Screen detection conditioned on | Tumor size, modality, age, density, frequency | Modality, age, density, frequency | Tumor size, modality, age, density, frequency |

| Implementation of screening benefit | Smaller tumor size | Younger age and earlier stage | Younger age and smaller tumor size |

| Estimation of overdiagnosisb | Difference screen and no screen | Difference screen and no screen | Difference screen and no screen |

| Implementation of treatment benefit | Cure fraction based on fatal diameter | Hazard reduction | Cure fraction |

| Factors affecting treatment benefit | ER and HER2; age; year of and size at diagnosis | ER and HER2; age; year of and stage at diagnosis | ER and HER2; age; year of and stage at diagnosis |

| Model software programc | Delphi | C++ | C++ |

| Detailed model description | van den Broek et al., 2018 (15) | Schechter et al., 2018 (16) | Alagoz et al., 2018 (17) |

Adapted from (6). Additional information is available from (18), and at https://resources.cisnet.cancer.gov/registry/site-summary/breast/. AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ; ER = estrogen receptor.

Overdiagnosis was defined as screen-detected cancer that would not have been diagnosed in a woman’s lifetime in the absence of screening.

Combined output from all 3 models was analyzed using SAS (Cary, NC) version 9.4.

Model Inputs

A cohort of US women born in 1970 was simulated using previously described inputs (6,18), such as breast cancer incidence (27), adjuvant therapy (28), and data from the BCSC (http://www.bcsc-research.org) for sensitivity, specificity, and benign biopsy rate of digital mammography by age, breast density, and screening round (first vs subsequent). We modeled 16 subgroups of women, defined on the basis of combinations of risk levels (RR = 0.6, 0.7, 0.85, and 1; see Table 2 for examples of risk factors associated with decreased risk) and 4 breast density categories (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System categories almost entirely fatty [a], scattered fibroglandular densities [b], heterogeneously dense [c], or extremely dense [d]). The risk level (relative risk) influenced the onset of breast cancer and was assumed to be constant over age. Breast density category was assigned at age 50 years and could decrease by 1 level or remain the same at age 65 years, based on the observed age-specific prevalence in the BCSC. Density affected mammography performance (32), whereas mammography performance was assumed to be unaffected by risk. Risk associated with density (Table 3) was combined multiplicatively with the risk of the different risk levels (relative risks). In this way, density and other risk factors were assumed to be independent determinants of breast cancer risk, consistent with observed data. Thus, a 50-year-old woman with heterogeneously dense breasts and a relative risk of 0.7 had a relative risk of 0.875 (0.7*1.25). In each simulation, women were followed until death or a model-specific upper age of 100 or 120 years. To evaluate the efficacy of different screening scenarios, we assumed 100% uptake of screening and treatment. We modeled biennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (13 screens) and triennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (9 screens).

Table 2.

Factors that are associated with decreased risk for breast cancer reported in literaturea

| Risk estimates | Risk group | Comparison group | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.65 | Age at first birth <20 y | Nulliparity | Ewertz et al., 1990 (13) |

| 0.67 | Age at menopause <40 y | Age at menopause 50-54 y | CGHFBC, 2012 (12) |

| 0.69 | Age at first birth 20-24 y | Nulliparity | Ewertz et al., 1990 (13) |

| 0.69 | 5 or more full-term pregnancy | 1 or 2 full-term pregnancy | Ewertz et al., 1990 (13) |

| 0.73 | Age at menopause 40-44 y | Age at menopause 50-54 y | CGHFBC, 2012 (12) |

| 0.75 | Women who breastfed > 12 months | Women who never breastfed | Bernier et al., 2000 (29) |

| 0.78 | Women who ever breastfed | Women who never breastfed | Bernier et al., 2000 (29) |

| 0.80-0.81 | Age at first birth 25-29 y | Nulliparity | Ewertz et al., 1990 (13); Nelson et al., 2012 (30) |

| 0.82 | Age at menarche ≥16 y | Age at menarche = 13 y | CGHFBC, 2012 (12) |

| 0.84 | 3 or 4 full-term pregnancy | 1 or 2 full-term pregnancy | Ewertz et al., 1990 (13) |

| 0.86 | Age at menopause 45-49 y | Age at menopause 50-54 | CGHFBC, 2012 (12) |

| 0.89 | Physical activity for ≥8000 MET min/wk | Physical activity <600 MET min/wk | Wu et al., 2013 (31) |

| 0.87-0.92 | Age at menarche at ≥15 y | Age at menarche = 13 y | CGHFBC, 2012 (12); Nelson et al., 2012 (30) |

CGHFBC = Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer; MET = metabolic equivalent.

Table 3.

Age-specific model input parameters by breast density

| Density | Age, y | Density prevalence | Density relative riska |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almost entirely fatty | 50-64 | 0.097 | 0.5 |

| ≥65 | 0.135 | 0.61 | |

| Scattered fibroglandular | 50-64 | 0.464 | 0.84 |

| ≥65 | 0.533 | 0.94 | |

| Heterogeneously dense | 50-64 | 0.376 | 1.25 |

| ≥65 | 0.3 | 1.28 | |

| Extremely dense | 50-64 | 0.063 | 1.53 |

| ≥65 | 0.032 | 1.45 |

Age-specific relative risk of breast cancer associated with breast density; reference group is women with average density. Data source: Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The models used sensitivity and specificity by age and screening interval (6).

Screening Outcomes

For all screening scenarios, we estimated outcomes per 1000 women alive at age 50 years, including the number of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive breast cancers detected. Benefits included breast cancer deaths averted, life-years gained, and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained. To calculate QALYs, we applied health-related quality-of-life utilities by age (33), and we applied quality-of-life decrements by attaching weights to specific health states for women undergoing a mammogram and diagnostics (34) and life-years with breast cancer by stage of disease at diagnosis (35). Harms included overdiagnosis, false-positives, and benign biopsies. Overdiagnosis was defined as screen-detected cancer that would not have been diagnosed in a woman’s lifetime in the absence of screening. In addition, harm to benefit ratios (false-positives per life-year gained and overdiagnosis per breast cancer death averted) were calculated.

Analysis

We presented all outcomes by subgroups of risk and density for each strategy using the median (minimum, maximum) of the 3 models. Each outcome was compared with a reference value, defined as the model-specific results for biennial screening from age 50 to 74 years, all densities combined (thus, with representative population frequencies of breast density categories), and average risk (RR = 1). We evaluated the differences between screening scenarios by assessing the incremental benefits and incremental harms by dividing the incremental harm by the incremental benefits.

We performed sensitivity analyses on varying utility values for undergoing screening and additional workup and on varying specificity by risk (9) (Supplementary Methods, available online).

Results

Screening Outcomes

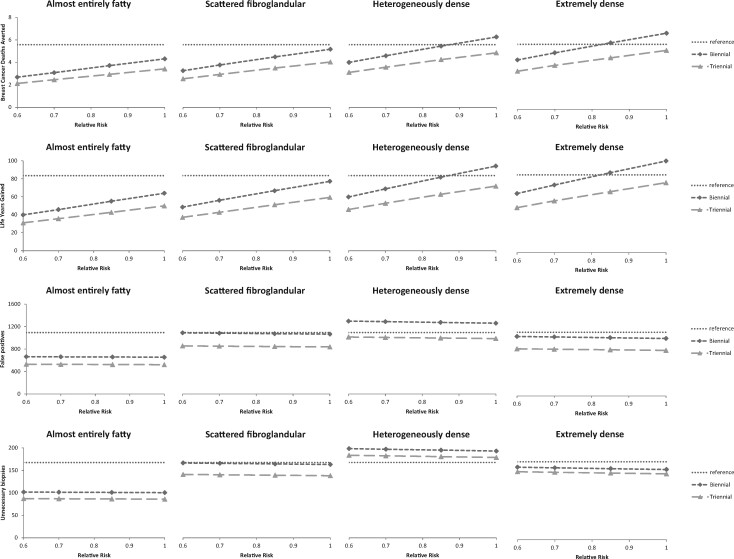

Among 1000 women aged 50 years followed over their lifetimes, the number of invasive breast cancers detected when screening biennially between ages 50 and 74 years varied substantially by subgroup; the highest number of invasive breast cancers was a median of 150 (range across models = 150-177) detected in the average-risk (RR = 1) extremely dense group and decreased with decreasing risk and density in all 3 models to 39 (range = 33-52) in the lowest risk-density category (ie, RR = 0.6 and almost entirely fatty breasts) (Table 4). The trends in lifetime benefits and harms are shown for 1 exemplar model (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Number of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), invasive breast cancers detected, lifetime benefits, and lifetime harms for biennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years per 1000 women followed over their lifetimes across modelsa

| Breast density at age 50 years | Relative risk | No. of DCIS detected, median (min, max) | No. of invasive BCs detected, median (min, max) | Lifetime benefits, median (min, max) |

Lifetime harms, median (min, max) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of BC deaths averted | Life-years gained | QALYs gained | False-positives | Biopsies | Overdiagnosis | ||||

| Almost entirely fatty | 0.60 | 16 (11, 24) | 39 (33, 52) | 2.5 (1.6, 2.7) | 40 (38, 44) | 25 (22, 26) | 665 (623, 824) | 102 (92, 128) | 12 (8, 19) |

| 0.70 | 18 (16, 27) | 45 (39, 77) | 2.9 (1.9, 3.1) | 46 (44, 52) | 30 (27, 30) | 663 (620, 821) | 101 (92, 127) | 14 (9, 22) | |

| 0.85 | 22 (20, 32) | 54 (47, 101) | 3.5 (2.3, 3.7) | 55 (53, 62) | 38 (33, 38) | 659 (617, 816) | 101 (91, 126) | 17 (11, 26) | |

| 1.00 | 25 (22, 37) | 63 (55, 117) | 4.1 (2.7, 4.3) | 64 (62, 73) | 45 (40, 46) | 656 (613, 811) | 100 (91, 126) | 20 (12, 29) | |

| Scattered fibroglandular density | 0.60 | 22 (12, 27) | 60 (58, 64) | 3.3 (2.6, 4.3) | 60 (48, 76) | 36 (29, 47) | 1088 (1018, 1267) | 166 (151, 197) | 17 (11, 18) |

| 0.70 | 25 (18, 30) | 74 (67, 89) | 3.8 (3.0, 4.9) | 70 (56, 88) | 43 (35, 56) | 1083 (1011, 1260) | 166 (150, 196) | 20 (12, 21) | |

| 0.85 | 31 (23, 36) | 89 (81, 116) | 4.5 (3.6, 6.0) | 84 (67, 106) | 54 (44, 70) | 1074 (1001, 1249) | 164 (148, 194) | 24 (15, 24) | |

| 1.00 | 36 (25, 41) | 103 (94, 133) | 5.2 (4.2, 7.0) | 98 (77, 124) | 65 (52, 84) | 1065 (991, 1238) | 163 (147, 192) | 27 (17, 27) | |

| Heterogeneously dense | 0.60 | 21 (15, 28) | 75 (72, 88) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.2) | 68 (60, 93) | 40 (36, 59) | 1297 (1213, 1495) | 198 (180, 232) | 17 (13, 18) |

| 0.70 | 24 (21, 32) | 102 (87, 106) | 4.6 (3.4, 6.0) | 79 (69, 108) | 49 (44, 71) | 1288 (1202, 1484) | 197 (178, 230) | 19 (15, 20) | |

| 0.85 | 29 (26, 38) | 121 (104, 136) | 5.5 (4.2, 7.2) | 95 (82, 130) | 61 (54, 88) | 1274 (1186, 1468) | 195 (176, 228) | 23 (18, 23) | |

| 1.00 | 33 (29, 43) | 140 (120, 156) | 6.3 (4.9, 8.4) | 111 (94, 152) | 73 (64, 106) | 1260 (1170, 1452) | 193 (174, 226) | 26 (20, 26) | |

| Extremely dense | 0.60 | 18 (17, 30) | 94 (83, 95) | 4.2 (2.9, 6.3) | 65 (63, 113) | 41 (40, 76) | 1023 (961, 1392) | 156 (142, 212) | 15 (14, 17) |

| 0.70 | 24 (21, 34) | 109 (108, 121) | 4.9 (3.3, 7.2) | 75 (73, 130) | 49 (48, 90) | 1014 (952, 1379) | 155 (141, 210) | 17 (15, 19) | |

| 0.85 | 30 (26, 40) | 130 (129, 155) | 5.7 (4.0, 8.7) | 90 (86, 157) | 60 (60, 111) | 1001 (938, 1360) | 153 (139, 208) | 20 (18, 22) | |

| 1.00 | 33 (30, 45) | 150 (150, 177) | 6.5 (4.7, 10.1) | 106 (98, 182) | 72 (70, 131) | 988 (924, 1342) | 151 (137, 205) | 22 (21, 24) | |

BC = breast cancer; QALYs = quality-adjusted life-years.

Figure 1.

Lifetime benefits and harms from exemplar model (model E). All outcomes are presented per 1000 women followed over their lifetimes by density, relative risk (RR), and screening scenario: breast cancer deaths averted, life-years gained, false-positives, and biopsies. Biennial (diamonds): biennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (13 screens). Triennial (triangles): triennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (9 screens). Reference (dotted horizontal line) shows the model-specific values for biennial screening from age 50 to 74 years, all densities combined, average risk (RR = 1).

Benefits

The absolute numbers of lifetime benefits decreased with decreasing risk and with decreasing density in all 3 models. For women with lower-than-average risk and fatty breasts, screening led to fewer benefits (breast cancer deaths averted and life-years gained) than for women at average risk and/or with denser breasts (Table 4; Supplementary Table 1, available online). For example, per 1000 women followed over their lifetime, biennial screening from age 50 to 74 years gained 40 (range = 38-44) life-years in low-risk women (RR = 0.6) with fatty breasts, whereas the same strategy gained a median of 64 (range = 62-73) life-years in average-risk women (RR = 1) with fatty breasts and a median of 106 (range = 98-182) in average-risk women (RR = 1) with extremely dense breast (Table 4). The finding that benefits decreased with decreasing risk (approximately linearly) was consistent across models, screening scenarios, density categories, and outcomes (breast cancer deaths averted, life-years gained, QALYs gained). Absolute benefits also increased with increasing density consistently across models, screening scenarios, and risk groups, although the increase was not linear and showed a leveling off for the highest density category (Table 4; Supplementary Table 1, available online). Biennial screening scenarios resulted in more benefits and triennial screening scenarios in all models and for all risk and density subgroups (Figure 1).

Harms

The number of false-positives were relatively stable over risk given our model assumptions (Table 4; Supplementary Table 2, available online), whereas the number of overdiagnoses decreased with decreasing risk (Figure 2). The number of false-positives was highest in breast density category C (heterogeneously dense) (Figure 1). The same trend was found for the number of benign biopsies (Figure 1).

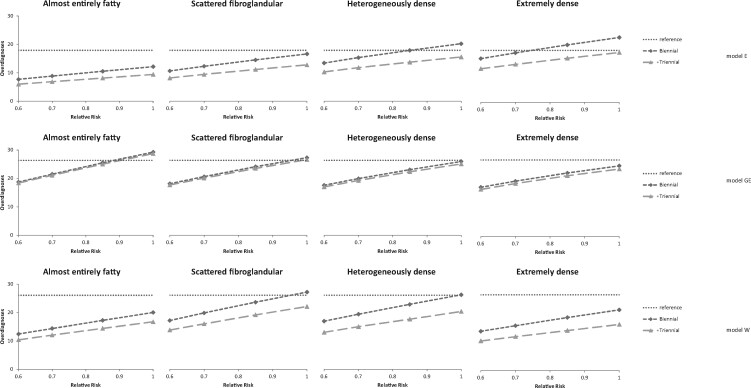

Figure 2.

Number of overdiagnosed women per 1000 women aged 40 years followed over their lifetime by density, relative risk (RR), screening scenario, and model: model E (upper part), model GE (middle part), and model W (lower part). Biennial (diamonds): biennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (13 screens). Triennial (triangles): and triennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years (9 screens). Reference (dotted horizontal line) shows the model-specific values for biennial screening from age 50 to 74 years, all densities combined, average risk (RR = 1).

The relationship between overdiagnosis and density varied across models: in model E, overdiagnosis increased with increasing density; in model W, overdiagnosis was highest in the 2 middle categories; and in model GE, overdiagnosis slightly decreased with increasing density (Figure 2). When overdiagnosis was expressed as a percentage of all breast cancers detected, the percentage decreased consistently in all models with increasing density from 22.7% (range = 12.1%-31.9%) to 11.6% (range =10.6%-12.5%) for a relative risk of 1 and did not vary by risk.

Harm to Benefit Ratios

The ratio between harms and benefits showed diversity across models and measures (Supplementary Table 3, available online). All models predicted a decrease in the number of false-positives per life-year gained with increasing risk and somewhat fewer false-positives per life-year gained in the extremely dense category.

Screening Scenarios (Biennial vs Triennial)

Biennial vs triennial screening has fewer benefits for the low-risk and low-density subgroups than for average-risk women (Table 5). The additional number of breast cancer deaths averted per 1000 women is 0.4 (range = 0.3-0.6) in women at lowest risk (RR = 0.6) with fatty breasts and 0.6 (range = 0.5-0.7) in women at lowest risk (RR = 0.6) with scattered fibroglandular densities with biennial vs triennial screening. For women with fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density and a relative risk of 0.6, 0.7, or 0.85, screening biennially (13 screens) vs screening triennially (9 screens) averted less than 1 additional breast cancer death and gained at most 16 life-years and 10 QALYs. For average-risk women with extremely dense breasts, there were 1.5 (range = 1.2-1.5) additional deaths averted, 28 life-years gained, and 19 QALYs gained with biennial vs triennial screening (Table 5).

Table 5.

The incremental number of breast cancer deaths averted, life-years gained, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained, false-positives, additional biopsies, and harm to benefit ratios when moving from triennial to biennial screening between ages 50 and 74 years per 1000 women followed over their lifetime

| Breast density at age 50 years | Relative risk | Median across models (min, max) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of additional breast cancer deaths averted | No. of additional life-years gained | QALYs gained | No. of additional false-positives | No. of additional biopsies | No. of additional overdiagnosis | Ratio of additional false-positives per additional life-year gained | Ratio of additional overdiagnosis per additional breast cancer death averted | Ratio of additional screens per additional life-year gained | ||

| Almost entirely fatty | 0.60 | 0.4 (0.3, 0.6) | 9 (6, 10) | 5 (2, 6) | 135 (126, 245) | 15 (13, 30) | 1.7 (0.3, 2.1) | 15 (13, 44) | 3.1 (1.1, 5.3) | 409 (373, 644) |

| 0.70 | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 10 (6, 11) | 6 (3, 7) | 135 (125, 244) | 15 (12, 30) | 2.0 (0.4, 2.3) | 13 (11, 38) | 3.2 (1.1, 5.2) | 356 (318, 558) | |

| 0.85 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) | 12 (8, 14) | 8 (4, 9) | 134 (125, 242) | 14 (12, 29) | 2.4 (0.5, 2.8) | 11 (9, 30) | 3.1 (1.0, 5.0) | 290 (259, 437) | |

| 1.00 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) | 14 (9, 16) | 10 (5, 11) | 133 (124, 241) | 14 (12, 29) | 2.7 (0.6, 3.3) | 9 (8, 26) | 3.1 (1.1, 5.1) | 254 (222, 384) | |

| Scattered fibroglandular density | 0.60 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 11 (10, 16) | 7 (5, 10) | 232 (216, 375) | 26 (22, 46) | 2.5 (0.4, 3.3) | 21 (14, 38) | 3.4 (0.8, 5.2) | 316 (224, 359) |

| 0.70 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.8) | 13 (12, 18) | 8 (6, 12) | 231 (215, 373) | 25 (22, 45) | 2.9 (0.5, 3.8) | 17 (12, 32) | 3.4 (0.8, 5.3) | 267 (194, 307) | |

| 0.85 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 16 (14, 21) | 10 (8, 14) | 229 (212, 369) | 25 (22, 45) | 3.4 (0.6, 4.5) | 15 (10, 27) | 3.4 (0.8, 5.1) | 226 (163, 254) | |

| 1.00 | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | 18 (16, 25) | 12 (10, 17) | 227 (210, 366) | 25 (21, 45) | 3.8 (0.7, 5.1) | 13 (8, 22) | 3.4 (0.8, 4.9) | 196 (138, 213) | |

| Heterogeneously dense | 0.60 | 0.8 (0.7, 0.9) | 14 (13, 18) | 8 (7, 11) | 283 (265, 444) | 15 (11, 38) | 3.1 (0.6, 3.9) | 20 (15, 33) | 3.5 (0.8, 5.3) | 253 (193, 264) |

| 0.70 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 16 (16, 21) | 10 (9, 14) | 281 (262, 441) | 15 (11, 38) | 3.5 (0.7, 4.4) | 18 (12, 28) | 3.5 (0.8, 4.9) | 219 (165, 226) | |

| 0.85 | 1.0 (1.0, 1.2) | 19 (19, 25) | 12 (11, 16) | 277 (258, 435) | 14 (11, 37) | 4.2 (0.8, 5.2) | 15 (10, 23) | 3.5 (0.7, 5.0) | 181 (138, 184) | |

| 1.00 | 1.2 (1.2, 1.4) | 22 (22, 29) | 15 (14, 20) | 274 (254, 430) | 14 (10, 37) | 4.7 (0.9, 5.9) | 12 (9, 20) | 3.3 (0.8, 4.9) | 153 (117, 158) | |

| Extremely dense | 0.60 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.0) | 18 (15, 18) | 10 (10, 12) | 213 (200, 423) | 10 (7, 36) | 3.4 (0.7, 3.5) | 14 (11, 24) | 3.6 (0.8, 4.5) | 199 (198, 231) |

| 0.70 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.1) | 20 (17, 20) | 12 (11, 14) | 211 (198, 419) | 10 (7, 36) | 3.8 (0.8, 4.0) | 12 (10, 21) | 3.7 (0.8, 4.4) | 173 (170, 203) | |

| 0.85 | 1.3 (1.0, 1.3) | 24 (20, 24) | 16 (14, 16) | 208 (195, 413) | 9 (7, 35) | 4.5 (1.0, 4.6) | 10 (8, 17) | 3.6 (0.7, 4.4) | 143 (141, 167) | |

| 1.00 | 1.5 (1.2, 1.5) | 28 (23, 28) | 19 (16, 20) | 205 (192, 408) | 9 (7, 35) | 5.1 (1.1, 5.2) | 9 (7, 14) | 3.5 (0.7, 4.2) | 120 (120, 145) | |

The number of additional false-positives was highest for the heterogeneously dense category, lowest for the almost entirely fatty category, and did not vary much by risk. For women with fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density and a relative risk of no more than 0.85, there were up to 232 additional false-positives per 1000 women (Table 5). There were more additional false-positives per additional life-year gained among the low-risk groups, and this ratio decreased with increasing risk in all models (Table 5). The number of additional overdiagnoses per breast cancer death averted decreased in 2 of the 3 models by risk and density (Table 5). The number of additional screens per additional life-year gained when going from triennial to biennial screening increased with decreasing risk and density consistently across models. In average risk women (RR = 1) with extremely dense breasts, models predicted that 120 (range = 120-145) additional screens were needed to gain 1 life-year when going from triennial to biennial screening, whereas in women at lowest risk (RR = 0.6) with fatty breasts, models predicted a substantially higher number of additional screens needed to gain 1 life-year: 409 (range = 373-644) (Table 5).

Sensitivity Analysis

Varying utility values for undergoing screening and additional workup or varying specificity by risk did not majorly change the ranking and differences between subgroups (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, available online).

Discussion

This is the first collaborative modeling study of breast cancer screening strategies for women at lower-than-average risk, while considering breast density in this assessment. The results indicate that triennial screening from age 50 to 74 years should be considered for women at lower-than-average risk with low density, because this strategy reduces harms while maintaining a large part of the benefits. This conclusion was robust across models and assumptions about disutility associated with screening and variations in specificity by risk.

Our findings are largely in line with previous studies. A previous modeling study, including the same 3 models, focusing on women at increased risk, found that average-risk women with low breast density undergoing triennial screening will maintain a similar or better balance of benefits and harms than average-risk women receiving biennial screening (6). Another modeling study using combined risk-based strategies also found that triennial screening from age 50-74 years was optimal for low-risk and medium-low–risk Spanish women (7) and even investigated less intense strategies (quinquennial screening). Moreover, triennial screening is the currently employed screening frequency in the United Kingdom and has been predicted to lead to a substantial mortality reduction (36). Also, the Canadian Task Force recommends screening with mammography every 2-3 years for women aged 50-69 years (37).

Our results show that for a subgroup of women with a combination of fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density and low-risk (RR = 0.6, 0.7, 0.85) incremental benefits (deaths averted, life-years gained, and QALYs gained) are small for biennial screening from age 50 to 74 years compared with triennial screening. This is reflected in the higher ratio between additional false-positives and additional life-years gained in the low-risk and low-density subgroups when going from triennial to biennial screening than in the average-risk population, indicating that there are (relatively) more harms relative to benefits in these subgroups than in the average-risk population.

The models consistently found that the benefits of screening decrease with decreasing risk, whereas the number of false-positives and unnecessary biopsies are mostly stable over categories of low risk. The latter was due to our assumption that mammography performance was unaffected by risk. The benefits also decreased with decreasing density, although the decrease in benefits was not so steep when comparing the highest density category to the next category, indicating that elevated risk among women with high density is a more important determinant of absolute screening benefits than high breast density. With regard to harms, false-positives and unnecessary biopsies were highest in the heterogeneously dense category, whereas the trends in overdiagnosis across density categories varied across models.

These results are useful for informing guidelines and for clinical practice. Because the conditions that result in lower-than-average risk are common, primary care providers could use these results in shared decision-making discussions with women. Most risk factors that lead to a decreased risk are not easily modifiable, but they are relatively straightforward to ascertain. If a subgroup of women can be identified to be at low risk, these women can relatively safely decrease their screening intensity from biennial to triennial.

We acknowledge that breast density is not known in women who have never been screened and is therefore difficult to use to tailor the interval of screening among low-risk women. However, it is possible to tailor the screening interval after a first mammogram based on density, especially because mandated standard reporting of breast density to women after a mammogram has become increasingly more common in the United States. Importantly, the measurement of breast density has become more reliable with automated density measures and has similar accuracy in predicting breast cancers (38‐40).

Strengths of this study include consideration of breast density; evaluation of a comprehensive set of outcomes for benefits and harms; and the use of 3 well-established, validated models (19). One of the strengths of collaborative modeling is that the combined results from the different independent modeling groups constitute a sensitivity analysis on model structure. Each model was developed using common data from multiple sources and an elaborate calibration process varying multiple parameters to match population-level breast cancer incidence and mortality data (from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER]). If models were to include alternative values for standard parameters, they would no longer be calibrated to SEER data, and the resulting predictions could not be viewed as reliable. A strength of our analysis is that each model incorporates different structural assumptions about unobservable natural breast cancer history, including varying assumptions regarding the percent of cancers (invasive and/or DCIS) that do not progress, and sojourn times, which inherently provide a sensitivity analysis on screening benefit. Taken collectively, the cross-model results provide stronger evidence than would any single model varying each parameter individually. In addition, most trends and the ranking of scenarios were very similar across models, except for the overdiagnosis results. We found especially that the trends in overdiagnosis across density categories varied across the models; in model E, the number of overdiagnosed women increases with increasing density, reflecting the higher risk associated with density, whereas in model GE, the number of overdiagnosed women decreased, reflecting the lower sensitivity associated with density, and in model W, overdiagnosis was highest in the 2 middle categories as a result of the 2 opposing causes of higher risk and lower sensitivity. The variation across models reflects uncertainty around overdiagnosis in general and uncertainty around overdiagnosis by density in particular.

Our study also had some limitations. Most importantly, we assumed that the relative risk only influenced the onset of breast cancer and was constant over age. Thus, our models assumed that the age distribution of cancers was similar to the average population reported in SEER and was just proportionately lower. We also assumed that the screening performance and the distribution of tumors in terms of estrogen receptors and HER2 are the same for lower-than-average risk women as that for average-risk women. It would be useful to reassess our results when there are additional data on disease biology and screening performance by risk level. Second, we modeled digital mammography screening. Several studies have suggested that the introduction of tomosynthesis in the United States has led to a reduction in recall rates (41,42), so that the number of false-positives might be reduced if tomosynthesis is widely used. However, the reductions in recall rate are relatively small in the United States (approximately 1%), and the effect of tomosynthesis on other harms, such as overdiagnosis, is still uncertain. In addition, our sensitivity analysis showed that even when quality-of-life effects due to false-positives are not taken into account, the ranking and differences between subgroups were largely unchanged. In addition, our analysis focuses on screening scenarios starting at age 50 years, and results will be different for older starting ages (eg, age 60 years). The absolute risk (for a woman with relative risk of 0.6) is higher at age 60 years than at age 50 years, and therefore more benefits (breast cancer deaths averted) are expected. However, for 60-year-old women, there are fewer life-years to be gained, and overdiagnosis increases by age. Future work might focus on the balance of benefits and harms for starting screening in (low-risk) older women. Finally, the models incorporate different structural assumptions about unobservable natural history, including the following 4 factors. First, the percent of invasive breast cancers that do not progress: model W includes a fraction of tumors with limited malignant potential, whereas models E and GE do not include a subset of invasive cancers that do not regress. Second, the models include a range of nonprogressive DCIS, resulting in a wide range of predicted overdiagnosis of DCIS from 34% to 62% (43). Third, the models assume that the benefit of screening arises from either detection at a smaller tumor size or at an earlier stage, and at a younger age. There is a range between these 3 models in predicted mortality reductions of 25%-32% for biennial screening in ages 50-74 years (22). Finally, for sojourn times, model GE includes an age-dependent sojourn time ranging from 2 to 4 years, whereas models E and W simulate continuous tumor growth with certain distributions, resulting in a wide range of distribution of sojourn times, including a subset of tumors with very short sojourn times as well as very long sojourn times. Estimates of mean sojourn times may be biased if they are based on a model that does not allow for nonprogressive (overdiagnosed) cancer (44).

Despite the substantial differences between models on these key assumptions, models come to the same conclusion regarding the incremental benefits and harms of biennial vs triennial screening in low-risk women.

Overall, our collaborative modeling study showed that triennial screening from ages 50 to 74 years can be considered for women who have fatty or scattered fibroglandular breast density and average or low risk of developing breast cancer and for women with very low risk at any density level. By undergoing more intense screening, these women are subjected to more harms, with only small added benefits. The results contribute to the growing body of evidence that tailored screening has many advantages over age-based guidelines for average populations (7,45). It will be important to translate our findings, and other results, into clinical practice and test the most effective methods for communication of breast cancer risk and breast density to enhance shared decision making about breast cancer screening.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA154292, U01 CA199218, U01 CA152958, P30 CA014520, and P30 CA023108). Data collection for model inputs from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant P01 CA154292 and grant U54 CA163303. The collection of BCSC cancer and vital status data used in this study was supported in part by several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the United States. For a full description of these sources, please see https://www.bcsc-research.org/about/work-acknowledgement.

Notes

Role of the funders: The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: Dr Kerlikowske reports unpaid consulting with Grail on the STRIVE study. The other authors have no disclosures.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Isabelle Lefebvre for data processing and analysis.

Author contributions: Conception and design: NTvR, CBS, OA, KK, JSM, DLM, BLS, NKS, HJdK, ATD, ANAT; Data analysis and interpretation: NTvR, CBS, JHM, OA, JJvdB, KK, JSM, DLM, BLS, NKS, HJdK, ATD, ANAT; Funding acquisition: KK, JSM, DLM, BLS, ATD, ANAT; Writing-original draft: NTvR; Writing-review&editing: CBS, JHM, OA, JJvdB, KK, JSM, DLM, BLS, NKS, HJdK, ATD, ANAT.

Data Availability

Input and output data from the models are available by sending a request to the corresponding author of this study (e-mail: n.vanravesteyn@erasmusmc.nl).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet. 2012;380(9855):1778–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, et al. Breast-cancer screening—viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2353–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siu AL; on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shieh Y, Eklund M, Madlensky L, et al. Breast cancer screening in the precision medicine era: risk-based screening in a population-based trial. J Natl Cancer Inst . 2017;109(5):djw290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schousboe JT, Kerlikowske K, Loh A, et al. Personalizing mammography by breast density and other risk factors for breast cancer: analysis of health benefits and cost-effectiveness. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):10–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trentham-Dietz A, Kerlikowske K, Stout NK, et al. ; on behalf of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network. Tailoring breast cancer screening intervals by breast density and risk for women aged 50 years or older: collaborative modeling of screening outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(10):700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vilaprinyo E, Forne C, Carles M, et al. ; the Interval Cancer (INCA) Study Group. Cost-effectiveness and harm-benefit analyses of risk-based screening strategies for breast cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e86858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lehman CD, Arao RF, Sprague BL, et al. National performance benchmarks for modern screening digital mammography: update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology. 2017;283(1):49–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson ANA, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tice JA, Miglioretti DL, Li C-S, et al. Breast density and benign breast disease: risk assessment to identify women at high risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3137–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, et al. Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(8):741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1141–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ewertz M, Duffy SW, Adami HO, et al. Age at first birth, parity and risk of breast cancer: a meta‐analysis of 8 studies from the Nordic countries. Int J Cancer. 1990;46(4):597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(3):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van den Broek JJ, van Ravesteyn NT, Heijnsdijk EA, et al. Simulating the impact of risk-based screening and treatment on breast cancer outcomes with MISCAN-Fadia. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):54S–65S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schechter CB, Near AM, Jayasekera J, et al. Structure, function, and applications of the Georgetown-Einstein (GE) breast cancer simulation model. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):66S–77S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alagoz O, Ergun MA, Cevik M, et al. The University of Wisconsin breast cancer epidemiology simulation model: an update. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):99S–111S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mandelblatt JS, Near AM, Miglioretti DL, et al. Common model inputs used in CISNET collaborative breast cancer modeling. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):9S–23S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van den Broek JJ, van Ravesteyn NT, Mandelblatt JS, et al. Comparing CISNET breast cancer incidence and mortality predictions to observed clinical trial results of mammography screening from ages 40 to 49. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):140S–150S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Plevritis SK, Munoz D, Kurian AW, et al. Association of screening and treatment with breast cancer mortality by molecular subtype in US Women, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2018;319(2):154–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berry DA, Cronin KA, Plevritis SK, et al. Effect of screening and adjuvant therapy on mortality from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1784–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mandelblatt JS, Stout NK, Schechter CB, et al. Collaborative modeling of the benefits and harms associated with different U.S. Breast Cancer Screening Strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stout NK, Lee SJ, Schechter CB, et al. Benefits, harms, and costs for breast cancer screening after US implementation of digital mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee CI, Cevik M, Alagoz O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of combined digital mammography and tomosynthesis screening for women with dense breasts. Radiology. 2015;274(3):772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sprague BL, Stout NK, Schechter C, et al. Benefits, harms, and cost-effectiveness of supplemental ultrasonography screening for women with dense breasts. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(3):157–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gangnon RE, Stout NK, Alagoz O, et al. Contribution of breast cancer to overall mortality for US women. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):24S–31S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gangnon RE, Sprague BL, Stout NK, et al. The contribution of mammography screening to breast cancer incidence trends in the United States: an updated age-period-cohort model. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(6):905–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100 000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):432–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bernier MO, Plu-Bureau G, Bossard N, et al. Breastfeeding and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of published studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(4):374–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson HD, Zakher B, Cantor A, et al. Risk factors for breast cancer for women aged 40 to 49 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(9):635–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wu Y, Zhang D, Kang S.. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(3):869–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kerlikowske K, Hubbard RA, Miglioretti DL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of digital versus film-screen mammography in community practice in the United States: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hanmer J, Lawrence WF, Anderson JP, et al. Report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for 7 health-related quality-of-life scores. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(4):391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Haes JC, de Koning HJ, van Oortmarssen GJ, et al. The impact of a breast cancer screening programme on quality-adjusted life-years. Int J Cancer. 1991;49(4):538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stout NK, Rosenberg MA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Retrospective cost-effectiveness analysis of screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(11):774–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gunsoy NB, Garcia-Closas M, Moss SM.. Estimating breast cancer mortality reduction and overdiagnosis due to screening for different strategies in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(10):2412–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Breast cancer update—clinician summary. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. 2018. https://canadiantaskforce.ca/breast-cancer-update-clinician-summary/. Accessed May 6, 2019.

- 38. Brandt KR, Scott CG, Ma L, et al. Comparison of clinical and automated breast density measurements: implications for risk prediction and supplemental screening. Radiology. 2016;279(3):710–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kerlikowske K, Scott CG, Mahmoudzadeh AP, et al. Automated and clinical breast imaging reporting and data system density measures predict risk for screen-detected and interval cancers: a case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(11):757–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alonzo-Proulx O, Mawdsley GE, Patrie JT, et al. Reliability of automated breast density measurements. Radiology. 2015;275(2):366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Miglioretti DL, Abraham L, Lee CI, et al. ; for the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Digital breast tomosynthesis: radiologist learning curve. Radiology. 2019;291(1):34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Ravesteyn NT, van den Broek JJ, Li X, et al. Modeling ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): an overview of CISNET Model Approaches. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):126S–139S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ryser MD, Gulati R, Eisenberg MC, et al. Identification of the fraction of indolent tumors and associated overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(1):197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pashayan N, Morris S, Gilbert FJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness and benefit-to-harm ratio of risk-stratified screening for breast cancer: a life-table model. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(11):1504–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Input and output data from the models are available by sending a request to the corresponding author of this study (e-mail: n.vanravesteyn@erasmusmc.nl).