Abstract

Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice are refractory to hepatocarcinogenesis caused by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) agonist Wy-14,643. However, the duration of these earlier studies was limited to approximately 1 year of treatment, and the ligand used has a higher affinity for the mouse PPARα compared to the human PPARα. Thus, the present study examined the effect of long-term administration of a potent, high-affinity human PPARα agonist (GW7647) on hepatocarcinogenesis in wild-type, Ppara-null, or PPARA-humanized mice. In wild-type mice, GW7647 caused hepatic expression of known PPARα target genes, hepatomegaly, hepatic MYC expression, hepatic cytotoxicity, and a high incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis. By contrast, these effects were essentially absent in Ppara-null mice or diminished in PPARA-humanized mice, although hepatocarcinogenesis was observed in both genotypes. Enhanced fatty change (steatosis) was also observed in both Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice independent of GW7647. PPARA-humanized mice administered GW7647 also exhibited increased necrosis after 5 weeks of treatment. Results from these studies demonstrate that the mouse PPARα is required for hepatocarcinogenesis induced by GW7647 administered throughout adulthood. Results also indicate that a species difference exists between rodents and human PPARα in the response to ligand activation of PPARα. The hepatocarcinogenesis observed in control and treated Ppara-null mice is likely mediated in part by increased hepatic fatty change, whereas the hepatocarcinogenesis observed in PPARA-humanized mice may also be due to enhanced fatty change and cytotoxicity that could be influenced by the minimal activity of the human PPARα in this mouse line on downstream mouse PPARα target genes. The Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mouse models are valuable tools for examining the mechanisms of PPARα-induced hepatocarcinogenesis, but the background level of liver cancer must be controlled for in the design and interpretation of studies that use these mice.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), hepatocarcinogenesis, species difference

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are ligand-activated transcription factors that regulate numerous physiological pathways including lipid homeostasis, differentiation, and inflammation (Corton et al., 2014, 2018; Heikkinen et al., 2007; Peters et al., 2005, 2012, 2019). PPARα that was first identified in 1990 (Issemann and Green, 1990) is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily and has an essential role in the regulation of numerous target genes encoding proteins that modulate fatty acid transport and lipid catabolism particularly in the liver. PPARα is the molecular target for the widely prescribed lipid-lowering fibrate drugs (Fruchart et al., 1998). The lipid-lowering function of PPARα occurs across a number of mammalian species, demonstrating its importance in lipid homeostasis. Interestingly, despite this critical functional role in regulating lipid homeostasis, chronic administration of PPARα agonists causes hepatocarcinogenesis in rodent models (Hays et al., 2005; Peters et al., 1997; Reddy et al., 1980). The fact that PPARα binding and activation is essential for PPARα agonist-induced liver cancer in mice is based on the observation that long-term administration of PPARα agonists causes a high incidence of liver tumors in wild-type mice, while Ppara-null mice are refractory to this effect (Hays et al., 2005; Peters et al., 1997). However, there is a large body of evidence that the hepatocarcinogenic effect of PPARα agonists may be rodent-specific. For example, epidemiological and retrospective studies in humans treated with the fibrate class of hypolipidemic drugs do not indicate any relationship between fibrate administration and an increased incidence of liver cancer (reviewed in Corton et al., 2018; Klaunig et al., 2003; Peters, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012). A number of hypotheses were postulated to explain these apparent species differences including differences in PPARα expression levels, differences in DNA response elements of target genes, and most recently, differences in the function of mouse PPARα compared to human PPARα (reviewed in Gonzalez and Shah, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012).

While there is reason to suggest that species differences exist between human and rodent PPARα, there remains a need to firmly establish the precise mechanisms that underlie this/these difference(s). For example, the EC50 for in vitro activation of mouse PPARα by Wy-14,643 is 0.6 µM compared to the EC50 for in vitro activation of the human PPARα, which is 5.0 µM (Shearer and Hoekstra, 2003). Moreover, most studies showing that Ppara-null or PPARα-humanized mice are resistant to the hepatocarcinogenic effects of a PPARα agonist were performed using Wy-14,643 administered for less than a year (Cheung et al., 2004; Hays et al., 2005; Morimura et al., 2006; Peters et al., 1997). Thus, since there is a difference in the ability to activate mouse versus human PPARα, it remains possible that differences in the proliferative and hepatocarcinogenic effects of PPARα agonists in PPARα-humanized mice could be influenced by ligand affinity for the receptor, and/or longer administration of the PPARα agonist. For these reasons, the present study examined the effect of long-term administration of GW7647, a PPARα agonist with high affinity for the human PPARα, on hepatocarcinogenesis using wild-type, Ppara-null, and PPARA-humanized mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemical synthesis

2-Methyl-2-[[4-[2-[[(cyclohexylamino)carbonyl](4-cyclohexylbutyl)amino]ethyl]phenyl]thio]-propanoic acid (GW7647) was synthesized as previously described (Brown et al., 2001). Preliminary studies to determine the dietary concentration of GW7647 required to effectively activate PPARα were performed using GW7647 synthesized by the Penn State Cancer Institute Organic Synthesis Shared Resource confirmed to be 97.1% purity based on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. GW7647 used for the other studies were synthesized commercially (Dalton Pharma Services, Toronto, CA) and was between 96.6 and 98.4% pure based on HPLC analyses.

Diets

Pelleted mouse chow was prepared (Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA) containing either 0.0 (control, based on Purina 5001 diet) or 0.01% GW7647 and provided to mice ad libitum. The concentration of GW7647 was based on results from a preliminary study that showed that relative to controls, 0.01% GW7647 caused a similar increase in liver weight and hepatic expression of the PPARα target gene cytochrome P450 4a10 (Cyp4a10) compared to 0.1% Wy-14,643 after 5 days of treatment (unpublished data). Tap water was available ad libitum.

Mice

Six- to 12-week-old male mice, either wild-type, Ppara-null, or PPARA-humanized were used for these studies. The three congenic lines of mice were bred in house at The Pennsylvania State University to generate mice for these studies that were all on the 129/Sv genetic background as previously described (Akiyama et al., 2001; Cheung et al., 2004). Mice were housed in an AAALAC-accredited animal vivarium in a temperature- and light-controlled environment (T = 25°C, 12-h light/12-h dark cycle).

Treatments

Adult, male wild-type, Ppara-null, or PPARA-humanized mice were fed either the control diet or one containing 0.01% GW7647 for either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term (Figure 1). The long-term treatment group was initially designed for the treatment of 104 weeks, but mice had to be terminated early due to morbidity and/or mortality. Mice were weighed at the initiation of each experiment, weekly thereafter, and at the time of euthanasia. Mice were euthanized after these four different exposure paradigms by over-exposure to carbon dioxide. Serum was obtained from blood collected after euthanasia and frozen at −80°C until further use. Tissues were weighed and gross observations were noted at necropsy. Representative sections of tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored frozen at −80°C and used for molecular/biochemical analyses as described below. Separate sections of representative tissue were also obtained and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) and processed for histopathologic examination as described below. Mice that died prior to scheduled euthanasia were not included for the calculation/compilation of endpoints for all groups.

Figure 1.

Schematic of treatments. Adult male wild-type, Ppara-null or PPARA-humanized mice were fed either a control diet or one containing 0.01% GW7647 for either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term administration, and tissues examined at each time point.

Pathology

Each liver was examined for the presence of grossly visible lesions. Representative liver samples were removed and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin and processed for embedding in paraffin. Paraffin sections were prepared from these samples, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined morphologically for the presence of preneoplastic lesions, adenomas, or carcinomas using established criteria (Thoolen et al., 2010). Histopathological analyses were performed by an expert pathologist who was blinded to the sample identities. Sample identities were revealed after the histopathological analyses were tabulated.

Target gene analyses of PPARα activation

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used to measure the mRNA expression of Cyp4a1, or acyl-CoA oxidase (Acox1) as previously described (Borland et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2016). Relative expression of each PPARα target gene was normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) that exhibited no change in expression by any treatment. Each assay included a standard curve with greater than 85% efficiency and a no-template control.

Serum alanine aminotransferase

Serum ALT was quantified from representative samples of mice as previously described (Zhang et al., 2016). Briefly, the VetScan MamMalian Liver Profile reagent rotors were used with the VetScan Chemistry Analyzer (Abaxis, Inc., Union City, CA) to determine the concentration of this marker in serum.

Western blot analysis

Liver extracts were prepared from mice treated with or without GW7647 as previously described (Koga et al., 2016). Hepatic extracts from mice fed GW7647 for long-term treatment were prepared from tissue with no grossly visible tumors. Quantitative Western blot analysis using a radioactive detection method was performed as previously described (Yao et al., 2014). The primary antibodies used were against MYC (catalog #9402, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; catalog #200-1173, Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA). The expression level of MYC was normalized to the expression of LDH and is presented as a fold increase compared to controls.

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey test for post hoc comparisons (Prism 8.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Histopathological and tumor incidence data were analyzed for differences between groups using the Fisher exact test (Prism 8.0; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). For all analyses, differences observed are only described when p ≤ .05.

RESULTS

GW7647 Activates Hepatic Mouse and Human PPARα in Mice

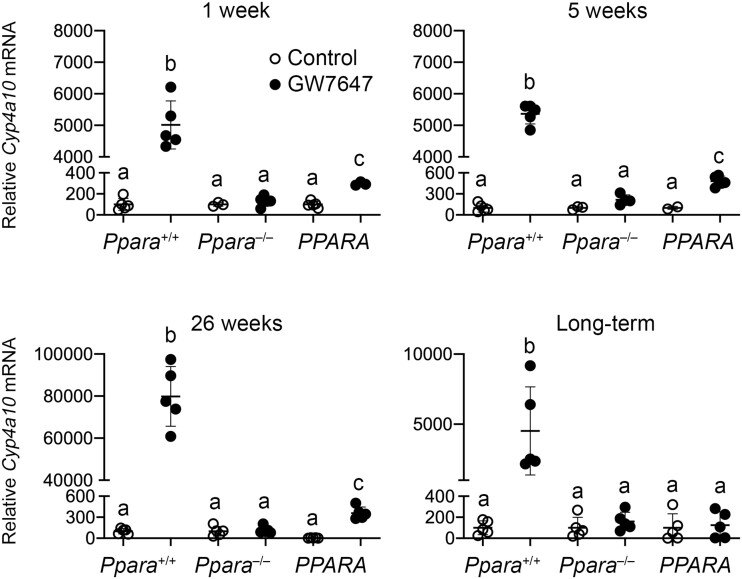

The relative expression of hepatic Cyp4a10 mRNA was higher in wild-type mice after administration of GW7647 at all time points compared to untreated controls (Figure 2). The increase in hepatic Cyp4a10 mRNA by administration of GW7647 did not occur in Ppara-null mice at all four time points (Figure 2). Compared to PPARA-humanized controls, relative expression of hepatic Cyp4a10 mRNA was increased by ligand activation of PPARα with GW7647 in PPARA-humanized mice after 1, 5, or 26 weeks of, but this effect was lower compared to similarly treated wild-type mice (Figure 2). Relative expression of hepatic Cyp4a10 mRNA was not affected in PPARA-humanized mice after long-term administration of GW7647 compared to controls in all genotypes (Figure 2). Relative expression of hepatic Acox1 mRNA was higher in wild-type mice following administration of GW7647 at all four time points as compared to untreated controls (Figure 3). Higher expression of Acox1 mRNA did not occur in Ppara-null mice in response to GW7647 administration at all four time points (Figure 3). Expression of hepatic Acox1 mRNA resembled the same pattern observed with Cyp4a10 as Acox1 mRNA was increased by ligand activation of PPARα by GW7647 in PPARA-humanized mice compared to PPARA-humanized controls at all four time points, an effect that was lower compared to similarly treated wild-type mice and was unchanged after long-term administration (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Relative hepatic expression of the PPARα target gene cytochrome P450 4A10 (Cyp4a10) in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–), or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice after either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 initiated as adults. Individual mouse data are presented as circles in the scatter plots, with the mean and standard deviation shown by lines within each scatter plot. Columns of data with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Figure 3.

Relative hepatic expression of the PPARα target gene cytochrome acyl CoA oxidase (Acox1) in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–), or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice after either 1, 5, and 26 weeks long-term administration of GW7647 initiated as adults. Individual mouse data are presented as circles in the scatter plots, with the mean and standard deviation shown by lines within each scatter plot. Columns of data with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Ligand Activation of PPARα Causes Differential Effects in Liver of Wild-Type, Ppara-Null and PPARA-Humanized Mice

Ligand activation of PPARα with GW7647 was associated with higher relative liver weight in wild-type mice as compared to wild-type controls at all four time points (Figure 4). Hepatomegaly was not observed in Ppara-null mice at any timepoint following GW7647 administration (Figure 4). Relative liver weight was higher in PPARA-humanized mice administered GW7647 compared to PPARA-humanized controls (Figure 4). However, the increase in relative liver weight at these time points in response to GW7647 was relatively lower in PPARA-humanized mice compared to similarly treated wild-type mice (Figure 4). Since MYC is regulated by mouse PPARα-dependent turnover (Shah et al., 2007), it is of interest to note that the relative hepatic expression of MYC was higher in wild-type mice in response to ligand activation of PPARα by GW7647 at all four time points compared to controls, and this effect was not found in similarly treated Ppara-null mice (Figure 5). Relative hepatic MYC expression was higher in PPARA-humanized mice after 5 or 26 weeks of GW7647 administration compared to PPARA-humanized controls (Figure 5). However, relative hepatic MYC expression was not different in PPARA-humanized mice after 1 week or long-term administration of dietary administration of GW7647 compared to PPARA-humanized controls (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Relative liver weight in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–) or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice after either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 initiated as adults. Individual mouse data are presented as circles in the scatter plots, with the mean and standard deviation shown by lines within each scatter plot. Columns of data with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Figure 5.

Quantitative western blot analysis of MYC expression (relative to LDH) in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–), or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice after either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 initiated as adults. Individual mouse data are presented as circles in the scatter plots, with the mean and standard deviation shown by lines within each scatter plot. Mean values with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

To examine whether hepatotoxicity was influenced by activation of PPARα, serum levels of ALT and histopathological analyses of the liver were performed. After 1 or 5 weeks of GW7647 administration, the average serum ALT concentration was not different in wild-type mice compared to wild-type controls (Figure 6). Average serum ALT was higher in wild-type mice by ligand activation of PPARα with GW7647 compared to wild-type controls after 26 weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 (Figure 6). This effect was not observed in similarly treated Ppara-null mice (Figure 6). Activation of PPARα with GW7647 in PPARA-humanized mice did not influence serum ALT after 1 or 26 weeks compared to control PPARA-humanized mice (Figure 6). However, compared to PPARA-humanized controls, serum levels of ALT were higher in PPARA-humanized mice after five weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–) or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice after either 1, 5, and 26 weeks or long-term administration of GW7647 initiated as adults. Individual mouse data are presented as circles in the scatter plots, with the mean and standard deviation shown by lines within each scatter plot. Columns of data with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

After 5 weeks of GW7647 administration, there were no consistent differences in the presence or degree of centrilobular hypertrophy, hepatocyte necrosis, inflammation, or macrovesicular fatty change between wild-type and Ppara-null mice compared to controls (Table 1). There was a higher incidence of severe centrilobular hypertrophy (p ≤ .05) and mild-to-severe hepatic macrovesicular fatty change (p ≤ .05) in PPARA-humanized mice after five weeks of GW7647 administration (Table 1, Figure 7) compared to wild-type and Ppara-null untreated controls (Table 1). After 26 weeks of GW7647 administration, no consistent changes in the presence or degree of centrilobular hypertrophy or hepatocyte necrosis were observed between wild-type and Ppara-null mice compared to controls of the same genotypes (Table 2). A PPARα-dependent increase in moderate to severe hepatic macrovesicular fatty change was observed in response to GW7647 in wild-type mice, an effect that was diminished in similarly treated Ppara-null mice (Table 2; p ≤ .05). Interestingly, acute hepatic inflammation was higher in Ppara-null mice treated with GW7647 compared to controls (Table 2; p ≤ .05). PPARA-humanized mice administered GW7647 exhibited more severe centrilobular hypertrophy, hepatic necrosis, and moderate to severe macrovesicular fatty change (Table 2; p ≤ .05, Figure 7) compared to PPARA-humanized control mice.

Table 1.

Effect of 5 weeks of Ligand Activation of PPARα with GW7647 Initiated in Adults on Liver Histopathology in Wild-Type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-Null (Ppara–/–) or PPARA Humanized Mice (PPARA)

| 5 weeks |

Ppara

+/+

|

Ppara

–/–

|

PPARA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | ||

| Centrilobular hypertrophy | None | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/5 |

| Mild | 0/5 | 4/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 2/4 | 0/5 | |

| Moderate | 5/5 | 1/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 2/4 | 0/5 | |

| Severe | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 1/5 | 0/4 | 5/5 | |

| Necrosis | None | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Present | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/5 | |

| Inflammation | None | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 5/5 |

| Acute | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/5 | |

| Chronic | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/5 | |

| Macrovesicular fatty change | None | 5/5 | 4/5 | 1/5 | 4/5 | 3/4 | 0/5 |

| Mild | 0/5 | 1/5 | 4/5 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 3/5 | |

| Moderate | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 1/5 | |

| Severe | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 1/5 | |

Figure 7.

Representative photomicrographs of liver histopathology. A, Hepatocellular hypertrophy in a PPARA-humanized mouse after five weeks of GW7647 administration. B, Hepatocellular hypertrophy and fatty change (steatosis) in PPARA-humanized mouse liver after twenty-six weeks of GW7647 administration. C, Region of hepatocellular necrosis in a PPARA-humanized mouse liver after 26 weeks of dietary GW7647 administration. D, Hepatocellular carcinoma in a wild-type mouse after long-term administration of GW7647. E, Hepatocellular carcinoma from a control Ppara-null mouse. F, Hepatocellular carcinoma from a Ppara-null mouse after long-term administration of GW7647. Note fatty change. G, Hepatocellular carcinoma from a control PPARA-humanized mouse. H, Hepatocellular carcinoma from a PPARA-humanized mouse after long-term administration of GW7647. Note excessive macrosteatosis. Magnification = 40×.

Table 2.

Effect of 26 weeks of Ligand Activation of PPARα with GW7647 Initiated in Adults on Liver Histopathology in Wild-Type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-Null (Ppara–/–) or PPARA Humanized Mice (PPARA)

| 26 weeks |

Ppara

+/+

|

Ppara –/– |

PPARA

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | ||

| Centrilobular hypertrophy | None | 0/10 | 1/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| Mild | 1/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 4/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | |

| Moderate | 4/10 | 6/10 | 8/10 | 4/10 | 8/10 | 2/10 | |

| Severe | 5/10 | 2/10 | 1/10 | 2/10 | 2/10 | 8/10 | |

| Necrosis | None | 8/10 | 9/10 | 10/10 | 8/10 | 10/10 | 4/10 |

| Present | 2/10 | 1/10 | 0/10 | 2/10 | 0/10 | 6/10 | |

| Inflammation | None | 6/10 | 6/10 | 6/10 | 1/10 | 9/10 | 8/10 |

| Acute | 1/10 | 3/10 | 3/10 | 7/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | |

| Chronic | 2/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 2/10 | 1/10 | 2/10 | |

| Macrovesicular fatty change | None | 8/10 | 0/10 | 5/10 | 5/10 | 1/10 | 2/10 |

| Mild | 1/10 | 0/10 | 3/10 | 2/10 | 1/10 | 0/10 | |

| Moderate | 1/10 | 4/10 | 1/10 | 3/10 | 6/10 | 2/10 | |

| Severe | 0/10 | 6/10 | 1/10 | 0/10 | 2/10 | 6/10 | |

Phenotypic Variance in the Response to Chronic Ligand Activation of Mouse or Human PPARα in a Mouse Model

Average body weight was not different between any genotype following long-term ligand activation of PPARα by GW7647 compared to controls (Figure 8). While morbidity and mortality were observed, the incidence of morbidity/mortality was not different between any genotype or treatment group (Table 3). The age at the time of euthanasia was not different between any groups (Table 3, Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Average weight gain in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–), or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice during GW7647 administration initiated as adults. Body weight was measured every 4 weeks. Values represent the mean ± SD.

Table 3.

Effect of Long-Term Ligand Activation of PPARα with GW7647 Initiated in Adults on Liver Histopathology (and Overtly Present Liver Lesions) in Wild-Type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-Null (Ppara–/–) or PPARA Humanized Mice (PPARA)

|

Ppara

+/+

|

Ppara

–/–

|

PPARA

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | Control | GW7647 | ||

| Centrilobular hypertrophy | None | 3/8 | 8/11 | 7/10 | 7/13 | 7/13 | 7/11 |

| Mild | 5/8 | 0/11 | 2/10 | 3/13 | 3/13 | 1/11 | |

| Moderate | 0/8 | 2/11 | 1/10 | 2/13 | 1/13 | 2/11 | |

| Severe | 0/8 | 1/11 | 0/10 | 1/13 | 0/13 | 0/11 | |

| Necrosis | None | 7/8 | 11/11 | 9/10 | 13/13 | 13/13 | 10/11 |

| Present | 1/8 | 0/11 | 1/10 | 0/13 | 0/13 | 1/11 | |

| Inflammation | None | 3/8 | 6/11 | 2/10 | 6/13 | 4/13 | 0/11 |

| Acute | 1/8 | 1/11 | 2/10 | 3/13 | 7/13 | 10/11 | |

| Chronic | 4/8 | 4/11 | 6/10 | 4/13 | 2/13 | 1/11 | |

| Macrovesicular fatty change | None | 6/8 | 6/11 | 5/10 | 4/13 | 5/13 | 5/11 |

| Mild | 2/8 | 3/11 | 2/10 | 7/13 | 3/13 | 3/11 | |

| Moderate | 0/8 | 2/11 | 3/10 | 2/13 | 5/13 | 3/11 | |

| Severe | 0/8 | 0/11 | 0/10 | 0/13 | 0/13 | 0/11 | |

| Tumora | Total | 0/8 | 11/11 | 2/10 | 7/13 | 5/13 | 8/11 |

| Hepatocellular adenoma | 0/8 | 11/11 | 2/10 | 6/13 | 4/13 | 6/11 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0/8 | 0/11 | 0/10 | 1/13 | 1/13 | 3/11 | |

| Gross findingsb | Tumor-like | 1/8 | 11/11 | 3/10 | 6/14 | 4/13 | 9/11 |

| Morbidity/Mortalityc | 5/13 | 4/15 | 5/15d | 2/16d | 1/14 | 1/12 | |

The number of tumors per slide identified histopathologically per group.

The number of mice with gross findings in the liver at the time of necropsy.

Mice that died or were euthanized for health reasons.

Fixation of one liver sample from this group was unsuccessful and was not examined for histopathology, but this mouse had no visible gross lesions in the liver.

Figure 9.

Age at termination in wild-type (Ppara+/+), Ppara-null (Ppara–/–), or PPARA-humanized (PPARA) mice following long-term GW7647 administration initiated as adults. Values represent the mean ± SD. Data with different letters are statistically significant at p ≤ .05.

Consistent with past studies (Maronpot et al. 2010), centrilobular hypertrophy was not observed extensively in any control or treatment group after long-term administration of GW7647 in contrast to earlier time points (Table 3). The incidence of hepatocellular necrosis was not different for any genotype between control or treatment after long-term administration of GW7647 (Table 3). There was no difference in the incidence of hepatocellular inflammation after long-term administration of GW7647 between wild-type or Ppara-null mice (Table 3). At the long-term timepoint, the incidence of acute hepatocellular inflammation was higher in control and GW7647-treated PPARA-humanized mice compared to wild-type controls (Table 3, p ≤ .05). The incidence of hepatic macrovesicular fatty change was similar between all genotypes and treatment groups after long-term administration of GW7647 (Table 3).

The appearance of liver tumors was grossly examined under a light source. The incidence of grossly detected liver tumors was 100% in wild-type mice following long-term GW7647 treatment (Table 3). One wild-type control mouse exhibited a liver nodule that appeared to be a liver tumor, but this was not confirmed by histopathology (Table 3). The relatively low number of mice in the latter group is the result of morbidity/early mortality (Table 3). The incidence of grossly apparent liver tumors was not different between control wild-type compared to control Ppara-null or control PPARA-humanized mice (Table 3). The incidence of grossly apparent liver tumors was lower in Ppara-null mice administered GW7647 compared to similarly treated wild-type mice and PPARA-humanized mice (Table 3, p ≤ .05). Histopathological analyses of adenomas and carcinomas by light microscopy were similar to the assessment noted by gross tumor examination between each genotype and treatment group at the time of necropsy (Table 3). Adenomas and/or carcinomas were not identified in control wild-type mice but were in a smaller cohort of control Ppara-null or control PPARA-humanized mice (Table 3, p ≤ .05, Figure 7). The background incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis detected by histopathological analyses in the control groups was not different between any of the three genotypes. The incidence of liver adenomas or carcinomas was higher in wild-type mice following long-term administration of GW7647 compared to control wild-type mice (Table 3, p ≤ .05). The incidence of liver adenomas or carcinomas was lower in Ppara-null compared to wild-type mice after long-term administration of GW7647 (Table 3, p ≤ .05). The incidence of liver adenomas or carcinomas in PPARA-humanized mice after long-term administration of GW7647 was not different as compared to similarly treated wild-type or Ppara-null mice (Table 3). Moreover, long-term administration of GW7647 did not cause an increase in the incidence of liver adenomas or carcinomas in either Ppara-null or PPARA-humanized mice compared to the respective control.

DISCUSSION

The current weight of evidence supports a mode of action for PPARα agonist-induced hepatocarcinogenesis that is initiated with ligand activation of the receptor, followed by transcriptional regulation of molecular targets that lead to changes in gene expression that cause increased proliferation of hepatocytes with the ultimate formation of liver tumors in rodents (reviewed in Corton et al., 2018; Klaunig et al., 2003; Peters, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012). Potential mutations in oncogenes and/or tumor suppressor genes involved in this mechanism are possibly due to increased oxidative stress and production of oxidative clustered DNA lesions (Sharma et al., 2016) that could be influenced by PPARα (Corton et al., 2018). Previous studies established that PPARα is required to mediate the hepatocarcinogenic effects of Wy-14,643 and bezafibrate in mice because Ppara-null mice are refractory to these effects (Hays et al., 2005; Morimura et al., 2006; Peters et al., 1997). However, there is also strong evidence that species differences exist in the function of PPARα between rodents and humans. Indeed, the fibrate class of hypolipidemic drugs activates PPARα and lower serum lipids in humans through mechanisms conserved between species, but the evidence supporting a causal link between activating PPARα and liver cancer in humans is lacking (reviewed in Corton et al., 2018; Klaunig et al., 2003; Peters, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012). Others have suggested that the mode of action for PPARα agonist-induced hepatocarcinogenesis may be more complex because liver tumors were observed in a cohort of Ppara-null mice treated with the weak PPARα activator, diethylhexylphthalate, and liver tumors were not found in a transgenic mouse line that expresses an artificially active PPARα (reviewed in Guyton et al., 2009; Keshava and Caldwell, 2006). Results from the present studies are impactful because they provide additional evidence that addresses these issues and supports a mechanism that might explain the species differences in PPARα agonist-induced mode of action for liver carcinogenesis.

Activation of PPARα with GW7647 in wild-type mice caused a high incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis after long-term administration, but this effect was largely diminished in similarly treated Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice. These results demonstrate that GW7647, a high-affinity agonist for both human and mouse PPARα, effectively activated both the mouse and human PPARα in mouse models, as noted by increased expression of PPARα target genes associated with lipid metabolism and consistent with previous studies using other PPARα ligands (Cheung et al., 2004; Morimura et al., 2006). However, while the mouse and human PPARα are activated by GW7647 in mice, the hepatocarcinogenic response is clearly divergent. In wild-type mice, activation of the endogenous mouse PPARα caused hepatomegaly, increased hepatotoxicity, increased expression of MYC, and a very high incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis. By contrast, these effects were largely diminished or absent in Ppara-null mice confirming that activation of the mouse PPARα with a PPARα agonist with high affinity for the human homolog is required to mediate these changes in mice. These collective changes are consistent with the PPARα mode of action in the liver (reviewed in Corton et al., 2018; Klaunig et al., 2003; Peters, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012). However, liver tumors were observed in Ppara-null mice following long-term dietary administration of GW7647; albeit at a lower incidence than in wild-type controls. It is also of interest to note that by contrast, the incidence of liver tumors in mice administered GW7647 initiated during perinatal development is absent in Ppara-null mice (Foreman et al., 2021). This is important because it supports the view that the incidence of liver tumors in Ppara-null mice may be due, at least in part, to the “background” incidence of liver tumors associated with aging as previously reported (Howroyd et al., 2004). Although not specifically examined in these studies, Ppara-null mice exhibit a reduced capacity to metabolize fatty acids (Aoyama et al., 1998). Fatty change is a hepatotoxic effect and is a known risk factor for liver cancer (Kanda et al., 2020). Thus, the hepatic fatty change phenotype of the untreated Ppara-null mice may predispose this mouse line to a higher incidence of “background” liver cancer. This is consistent with the phenotype of aged Ppara-null control mice in the present studies and indicates that this hypothesis should be examined in more detail.

Results from the present studies also demonstrate a differential phenotype in the PPARA-humanized mice. Similar to the phenotype observed in Ppara-null mice, in response to GW7647 PPARA-humanized mice exhibited an intermediate degree of changes that preceded hepatocarcinogenesis including hepatomegaly, changes in hepatic MYC levels, and increased hepatocyte cytotoxicity. However, the magnitude of these changes was greater compared to these effects induced by GW7647 in Ppara-null mice. Moreover, whereas the observed increase in liver tumor incidence in wild-type mice following ligand activation of PPARα by GW7647 was 100% in this study and markedly higher compared to wild-type controls, ligand activation of PPARα with GW7647 did not cause a significant increase in the incidence of liver tumors in either Ppara-null or PPARA-humanized mice as compared to their untreated genotype-specific controls. Because the PPARA-humanized mice express a functional human PPARα, these results suggest that the mechanism by which liver tumors develop in PPARA-humanized and the Ppara-null mice are likely different than those induced by the mouse PPARα in response to GW7647 (a high-affinity human PPARα agonist). Consistent with this, ligand activation with GW7647 for 26 weeks in the present studies caused severe liver necrosis in PPARA-humanized mice that were not found in similarly treated wild-type or Ppara-null mice. Enhanced chronic inflammation was also found in PPARA-humanized mice in response to ligand activation of PPARα with GW7647. Combined, these observations suggest that the necrotic changes accompanying chronic inflammation could contribute to the mechanisms that mediate hepatocarcinogenesis in PPARA-humanized mice treated with GW7647. It is also possible that the effects observed in PPARA-humanized mice might be related to basal activity of the human PPARα, similar to effects observed in other humanized transgenic models (Tateno et al., 2015; Yamada et al., 2014). This is supported by the finding that hepatic changes did occur in PPARA-humanized mice treated with GW7647 but were less as compared to similarly treated wild-type mice consistent with previous studies (Cheung et al., 2004; Morimura et al., 2006). Lastly, although less likely for reasons explained above, the human PPARα could retain some activity and mediate changes similar to that observed in wild-type mice expressing the mouse PPARα. The notion that the human PPARα does not cause changes in human hepatocytes that promote liver cancer in response to ligand activation is supported by results from this study and others (reviewed in Corton et al., 2018; Klaunig et al., 2003; Peters, 2008; Peters et al., 2005, 2012), but additional studies are needed to distinguish between these possibilities.

Results from the present studies, and those from the companion paper (Foreman et al., 2021), strongly support the body of evidence indicating that there are species differences in the hepatic response to ligand activation of PPARα. Age in this strain (Sv/129) appears to influence the effects of activating PPARα. For example, more liver tumors were observed in both Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice when chronic activation of PPARα is initiated in adult mice as compared to initiating treatment during perinatal development (Foreman et al., 2021). This suggests that aging may contribute to liver tumorigenesis in Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice, independent of activating PPARα. Importantly, these studies also provide strong evidence demonstrating the utility of both the Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice for studying the mechanisms mediating liver cancer resulting from activation of PPARα.

Combined, results from these studies provide further mechanistic insight into how the effects of PPARα ligands on the mouse and human PPAR are similar, and still different, with respect to modulating liver cancer. The background incidence of liver carcinogenesis observed in Ppara-null and PPARA-humanized mice must be controlled for in studies using these models.

FUNDING

The National Institutes of Health (ES017568 to J.E.F.); the USDA National Institute of Food and Federal Appropriations (Project PEN04607 and accession number 1009993 to J.M.P.); the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco C.U.R.E. Funds to J.M.P. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author/authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Penn State Cancer Institute Organic Synthesis Shared Resource for the synthesis of some of the GW7647 used for some of these studies. The authors thank Dr Lance Kramer and Mr Leonard Collins of the UNC Biomarker Facility Core for technical assistance with these studies.

REFERENCES

- Akiyama T. E., Nicol C. J., Fievet C., Staels B., Ward J. M., Auwerx J., Lee S. S., Gonzalez F. J., Peters J. M. (2001). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α regulates lipid homeostasis, but is not associated with obesity: Studies with congenic mouse lines. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39088–39093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama A., Peters J. M., Iritani N., Nasu-Nakajima T., Furihata K., Hashimoto T., Gonzalez F. J. (1998). Altered constitutive expression of fatty acid-metabolizing enzymes in mice lacking the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5678–5684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland M. G., Yao P. L., Kehres E. M., Lee C., Pritzlaff A. M., Ola E., Wagner A. L., Shannon B. E., Albrecht P. P., Zhu B., et al. (2017). Editor's Highlight: PPARβ/δ and PPARγ inhibit melanoma tumorigenicity by modulating inflammation and apoptosis. Toxicol. Sci. 159, 436–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. J., Stuart L. W., Hurley K. P., Lewis M. C., Winegar D. A., Wilson J. G., Wilkison W. O., Ittoop O. R., Willson T. M. (2001). Identification of a subtype selective human PPARα agonist through parallel-array synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 1225–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C., Akiyama T. E., Ward J. M., Nicol C. J., Feigenbaum L., Vinson C., Gonzalez F. J. (2004). Diminished hepatocellular proliferation in mice humanized for the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α. Cancer Res. 64, 3849–3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corton J. C., Cunningham M. L., Hummer B. T., Lau C., Meek B., Peters J. M., Popp J. A., Rhomberg L., Seed J., Klaunig J. E. (2014). Mode of action framework analysis for receptor-mediated toxicity: The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) as a case study. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 44, 1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corton J. C., Peters J. M., Klaunig J. E. (2018). The PPARα-dependent rodent liver tumor response is not relevant to humans: Addressing misconceptions. Arch. Toxicol. 92, 83–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman J. E., Koga T., Kosyk O., Kang B.-H., Zhu, X., Cohen S. M., Billy L. J., Sharma A., Amin S., Gonzalez F. J., et al. (2021). Species differences between mouse and human PPARα in modulating the hepatocarcinogenic effects of perinatal exposure to a high affinity human PPARα agonist in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 183, 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchart J. C., Brewer H. B. Jr., Leitersdorf E. (1998). Consensus for the use of fibrates in the treatment of dyslipoproteinemia and coronary heart disease. Fibrate Consensus Group. Am. J. Cardiol. 81, 912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez F. J., Shah Y. M. (2008). PPARα: Mechanism of species differences and hepatocarcinogenesis of peroxisome proliferators. Toxicology 246, 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton K. Z., Chiu W. A., Bateson T. F., Jinot J., Scott C. S., Brown R. C., Caldwell J. C. (2009). A reexamination of the PPAR-α activation mode of action as a basis for assessing human cancer risks of environmental contaminants. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 1664–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays T., Rusyn I., Burns A. M., Kennett M. J., Ward J. M., Gonzalez F. J., Peters J. M. (2005). Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) in bezafibrate-induced hepatocarcinogenesis and cholestasis. Carcinogenesis 26, 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen S., Auwerx J., Argmann C. A. (2007). PPARγ in human and mouse physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 999–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howroyd P., Swanson C., Dunn C., Cattley R. C., Corton J. C. (2004). Decreased longevity and enhancement of age-dependent lesions in mice lacking the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα). Toxicol. Pathol. 32, 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issemann I., Green S. (1990). Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature 347, 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda T., Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Masuzaki R., Moriyama M., Omata M. (2020). Molecular mechanisms: Connections between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci 21, 1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshava N., Caldwell J. C. (2006). Key issues in the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonism and cell signaling in trichloroethylene toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1464–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaunig J. E., Babich M. A., Baetcke K. P., Cook J. C., Corton J. C., David R. M., DeLuca J. G., Lai D. Y., McKee R. H., Peters J. M., et al. (2003). PPARα agonist-induced rodent tumors: Modes of action and human relevance. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 33, 655–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga T., Yao P. L., Goudarzi M., Murray I. A., Balandaram G., Gonzalez F. J., Perdew G. H., Fornace A. J. Jr.,, Peters J. M. (2016). Regulation of cytochrome P450 2B10 (CYP2B10) expression in liver by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ modulation of SP1 promoter occupancy. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 25255–25263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maronpot R. R., Yoshizawa K., Nyska A., Harada T., Flake G., Mueller G., Singh B., Ward J. M. (2010). Hepatic enzyme induction: Histopathology. Toxicol. Pathol. 38, 776–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimura K., Cheung C., Ward J. M., Reddy J. K., Gonzalez F. J. (2006). Differential susceptibility of mice humanized for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α to Wy-14,643-induced liver tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis 27, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M. (2008). Mechanistic evaluation of PPAR-mediated hepatocarcinogenesis: Are we there yet? Toxicol. Sci. 101, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M., Cattley R. C., Gonzalez F. J. (1997). Role of PPARα in the mechanism of action of the nongenotoxic carcinogen and peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643. Carcinogenesis 18, 2029–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M., Cheung C., Gonzalez F. J. (2005). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α and liver cancer: Where do we stand? J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 83, 774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M., Shah Y. M., Gonzalez F. J. (2012). The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. M., Walter V., Patterson A. D., Gonzalez F. J. (2019). Unraveling the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPARβ/δ) expression in colon carcinogenesis. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 3, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy J. K., Azarnoff D. L., Hignite C. E. (1980). Hypolipidaemic hepatic peroxisome proliferators form a novel class of chemical carcinogens. Nature 283, 397–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah Y. M., Morimura K., Yang Q., Tanabe T., Takagi M., Gonzalez F. J. (2007). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α regulates a microRNA-mediated signaling cascade responsible for hepatocellular proliferation. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4238–4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Collins L. B., Chen T. H., Herr N., Takeda S., Sun W., Swenberg J. A., Nakamura J. (2016). Oxidative stress at low levels can induce clustered DNA lesions leading to NHEJ mediated mutations. Oncotarget 7, 25377–25390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer B. G., Hoekstra W. J. (2003). Recent advances in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor science. Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 267–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno C., Yamamoto T., Utoh R., Yamasaki C., Ishida Y., Myoken Y., Oofusa K., Okada M., Tsutsui N., Yoshizato K. (2015). Chimeric mice with hepatocyte-humanized liver as an appropriate model to study human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α. Toxicol. Pathol. 43, 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoolen B., Maronpot R. R., Harada T., Nyska A., Rousseaux C., Nolte T., Malarkey D. E., Kaufmann W., Kuttler K., Deschl U., et al. (2010). Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol. Pathol. 38, 5s–81s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Okuda Y., Kushida M., Sumida K., Takeuchi H., Nagahori H., Fukuda T., Lake B. G., Cohen S. M., Kawamura S. (2014). Human hepatocytes support the hypertrophic but not the hyperplastic response to the murine nongenotoxic hepatocarcinogen sodium phenobarbital in an in vivo study using a chimeric mouse with humanized liver. Toxicol. Sci. 142, 137–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao P. L., Morales J. L., Zhu B., Kang B. H., Gonzalez F. J., Peters J. M. (2014). Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ (PPAR-β/δ) inhibits human breast cancer cell line tumorigenicity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 1008–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Krishnan P., Ehresman D. J., Smith P. B., Dutta M., Bagley B. D., Chang S. C., Butenhoff J. L., Patterson A. D., Peters J. M. (2016). Editor's highlight: Perfluorooctane sulfonate-choline ion pair formation: a potential mechanism modulating hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 153, 186–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]