Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia and the only illness among the top 10 causes of death for which there is no disease-modifying therapy. The failure rate of clinical trials is very high, in part due to the premature translation of successful results in transgenic mouse models to patients. Extensive evidence suggests that dysregulation of innate immunity and microglia/macrophages plays a key role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Activated resident microglia and peripheral macrophages can display protective or detrimental phenotypes depending on the stimulus and environment. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of innate immune regulators known to play an important role in governing the phenotypic status of microglia. We have shown in multiple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse models that harnessing innate immunity via TLR9 agonist CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) modulates age-related defects associated with immune cells and safely reduces amyloid plaques, oligomeric amyloid-β, tau pathology, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) while promoting cognitive benefits. In the current study we have used a non-human primate model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease pathology that develops extensive CAA—elderly squirrel monkeys. The major complications in current immunotherapeutic trials for Alzheimer’s disease are amyloid-related imaging abnormalities, which are linked to the presence and extent of CAA; hence, the prominence of CAA in elderly squirrel monkeys makes them a valuable model for studying the safety of the CpG ODN-based concept of immunomodulation. We demonstrate that long-term use of Class B CpG ODN 2006 induces a favourable degree of innate immunity stimulation without producing excessive or sustained inflammation, resulting in efficient amelioration of both CAA and tau Alzheimer’s disease-related pathologies in association with behavioural improvements and in the absence of microhaemorrhages in aged elderly squirrel monkeys. CpG ODN 2006 has been well established in numerous human trials for a variety of diseases. The present evidence together with our earlier, extensive preclinical research, validates the beneficial therapeutic outcomes and safety of this innovative immunomodulatory approach, increasing the likelihood of CpG ODN therapeutic efficacy in future clinical trials.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, immunomodulation, CpG ODN, squirrel monkey

Patel et al. show that using the TLR9 agonist CpG ODN 2006 to stimulate innate immunity reduces Alzheimer’s disease pathology and produces cognitive benefits in aged squirrel monkeys, suggesting that this immunomodulatory approach could also have therapeutic potential in patients.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia in the elderly, is characterized by amyloid-β plaques within the brain parenchyma and amyloid-β accumulation in blood vessels [cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)], as well as by the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neurodegeneration.1 It is becoming increasingly recognized that chronic neuroinflammation plays a significant role in Alzheimer’s disease progression.2-4 Large-scale genome wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several innate immunity-related genes that are associated with an elevated risk for the development of late onset Alzheimer’s disease.4,5 Many of these genes are highly expressed among microglia as regulators of phagocytic activity and inflammatory activation state, suggesting that microglial functions play a key role in the pathogenesis of late onset Alzheimer’s disease.6,7 Activated microglia/macrophages can display a beneficial or detrimental phenotype depending on the environment. Growing evidence suggests that tightly regulated modulation of innate immunity, particularly of mononuclear cell phenotypes and their phagocytic ability, can be neuroprotective and represents a viable therapeutic strategy contingent upon the nature of the stimulus, duration of the response, and the disease stage.2,8-11

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of innate immune modulators known to play an important role in governing the phenotypic status of microglia.12,13 Stimulation of TLR signalling pathways has been associated with immune responses contributing to mitigation of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.14–18 However, several studies have reported adverse effects from TLR manipulation in Alzheimer’s disease models.18–21 Discrepancies between various reports may be reconciled by the fact that depending on the type, concentration, and administration frequency of TLR ligands, different signalling pathways can be triggered, leading to either neuroprotection or neurotoxicity. We have focused on harnessing innate immunity via TLR9 to modulate age-related defects associated with immune cells and to counteract Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) that contain unmethylated CpG dinucleotides within specific sequence contexts (CpG motifs), similar to those found in bacterial DNA, trigger an immunostimulatory cascade via endosomal TLR9.22,23 Numerous clinical studies have explored the use of CpG ODNs, which do not cross the blood–brain barrier, for the treatment of cancers, allergies, and infectious diseases, including a recent application of CpG ODN advanced adjuvant in an ongoing COVID-19 vaccine trial (NCT04405908); hence, supporting the safety and therapeutic value of TLR9-based agents.24–27

To date, many immunotherapies targeting amyloid-β have been tested in clinical trials, but unfortunately, none have yet resulted in significant cognitive benefits, with the possible recent exception of aducanumab.28 The occurrence of microhaemorrhages and excessive neuroinflammation linked to the clearance of CAA and manifestation as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), have been the major complications in current immunotherapeutic trials.28–32 Our initial comprehensive findings from transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse models indicate that stimulation of innate immunity with TLR9 ligand, Class B CpG ODN, ameliorates all pathological lesions, including amyloid plaques, oligomeric amyloid-β, tau pathology, and CAA without associated microhaemorrhages or provoking sustained inflammation.33–35 Progress in discovering potential therapies for Alzheimer’s disease and CAA has been hindered by the lack of animal models that more closely resemble sporadic human disease.36 Prior to human clinical trials, non-human primates are a suitable choice for evaluating therapeutic agents that have previously shown to be effective in mice. Non-human primates are more proximate models of age-associated amyloid-β depositions with endogenous levels of amyloid-β similar to humans and an amino acid sequence of amyloid-β identical to human amyloid-β.37,38

The contribution of vascular pathology to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias has been increasingly acknowledged. Therefore, we advanced our studies using the New World species, squirrel monkeys, which unlike other non-human primates develop abundant age-dependent CAA.39,40 Recent evidence documents the occurrence of spontaneous ARIA in aged squirrel monkeys, making this model ideal for testing the safety of our approach.41 The present studies were designed to assess whether a well-characterized TLR9 ligand, Class B CpG ODN 2006, can efficiently and safely reduce CAA accumulation in elderly squirrel monkeys at the point of established Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. CpG ODN 2006 has shown excellent safety profiles in numerous clinical trials.25,26 However, this is the first report examining the ability of CpG ODN 2006 to boost immune responses in aged non-human primates with senescent immune functions. Hence, we further develop our novel concept of immunomodulation in order to provide essential preclinical evidence for CpG ODN use as an effective disease-modifying drug for Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and methods

Animals

Monkey, care and housing

The studies were performed in elderly (17–19 years of age) female squirrel monkeys (Saimiri boliviensis boliviensis). Squirrel monkeys are New World non-human primates that naturally develop amyloid-related pathology. The average lifespan of a squirrel monkey in captivity is 20 years and the maximum life expectancy is 30 years.42,43 Squirrel monkeys successfully breed in a harem scheme, consisting of single-male/multi-female groups with ratios as high as one male to 10–12 females.44 Therefore, only aged female squirrel monkeys were available for our study. Amyloid-β depositions in squirrel monkey brain are mainly within the brain vasculature rather than in the parenchyma.39,40 Monkeys were obtained from a colony of the Squirrel Monkey Breeding and Research Resource (SMBRR) at the Michale E. Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research (KCCMR), University of Texas (UT) MD Anderson Cancer Cener (MDACC). The animals included in the study had never been subjected to any experimental treatment and were disease free. Fifteen elderly and 12 young (treatment-naïve) animals were enrolled in the study. Squirrel monkeys were continuously monitored for signs of toxicity by the clinical veterinarian. Further details on housing and diet are available in the Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

This research was conducted at the AAALAC-I accredited Michale E. Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop, TX, USA (Common squirrel monkeys 03-09-02781). All animal experiments were carried out according to the provisions of the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Animal Welfare Policy, and the principles of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.45 All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the New York University School of Medicine and the University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Treatment and CpG ODN

TLR9 agonist CpG ODN 2006 (referred to as CpG ODN 7909 in human trials),25 a Class B 24mer single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) (5′-TCGTCGTTTTGTCGTTTTGTCGTT-3′) with a complete phosphorothioate backbone, was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The preferred route of administering CpG ODN and the most efficient in inducing immune response is subcutaneous. Female aged monkeys were subcutaneously injected into the interclavicular space with either 2 mg/kg CpG ODN (n = 8) or vehicle (vehicle/saline, n = 7) at monthly intervals for a 24-month period. Animals of the same age were randomly assigned to both treatment groups. All injections occurred in the morning (8–9 a.m.) before the animals were fed. During treatment primates were closely monitored for differences in total body weight, food consumption, body temperature, physical appearance, unprovoked behaviour, and response to external stimuli. Safety was determined through incidence of adverse events, changes in clinical laboratory measures (haematology and blood biochemistry), and physical examination. Attention was given to flu-like symptoms and injection site reactions (erythema, oedema).

Behavioural testing

Behavioural analyses were performed in the final months of treatment and consisted of a cognitive assessment and measurement of locomotor abilities. The latter locomotor activity test verified that performance on cognitive testing was not influenced by locomotor abnormalities. The Inhibitory Control of Behaviour test46 was chosen to evaluate learning and memory in elderly CpG ODN- and vehicle-treated animals (19–21 years old) and in young treatment-naïve animals (6–9 years old). Our young cohort was tested in parallel with our aged animals. Spatial working memory was assessed in aged monkeys using a Delayed Nonmatching-to-Sample T Maze test.47 Squirrel monkeys underwent behavioural testing within the animal’s social group by an individual who was blinded to the animal’s treatment status. Positive reinforcement training was used to teach the subjects to station at a test point and not interfere with one another’s testing.48 The Inhibitory Control of Behaviour test was performed prior to Delayed Nonmatching-to-Sample T maze test. T maze test was concluded 1 month prior to euthanasia. Detailed protocols of behavioural tests are provided in the Supplementary material.

Histological studies

Euthanasia

Following behavioural testing, animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and subsequently euthanized for analysis of brain pathology. Transcardial perfusion was conducted using a 0.1 M PBS-heparin solution (10 000 U/l; pH 7.4).

Tissue processing

After perfusion, the brain was removed and cut into 14 equidistant 4-mm thick coronal brain regions (rostral to caudal) using a commercially available squirrel monkey brain slicer. The cerebellum was dissected prior to coronal cuts. The coronal blocks were cut along the sagittal midline to separate the hemispheres. The right brain hemisphere was immersion-fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 48 h (room temperature) and processed for paraffin sectioning (NYU Langone’s Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory). The left brain hemisphere was snap-frozen and stored at −80°C for biochemical assays. In addition, samples of the liver, spleen, and kidneys were collected from all animals, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, and processed for paraffin sectioning for further histopathological assessment to evaluate any signs of systemic toxicity.

Immunohistochemistry and histology

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded coronal brain sections cut at a thickness of 8 µm were used for histological assessment of brain pathology using standard techniques and as previously described.33,34,49 Antibodies and protocols for staining are provided in the Supplementary material. All stained brain sections were scanned by the NYU Langone’s Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory using a NanoZoomer whole-slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics) for subsequent quantitative analyses. Quantification of total amyloid burden (6E10/4G8), fibrillar amyloid burden (thioflavin-S), pyroglutamate amyloid burden [(AβpE3), post-translationally modified N-terminally truncated pyroglutamate-modified amyloid-β species], and CD3 T-lymphocyte burden were performed using ImageJ processing program (ImageJ V1.48). Assessments of astrocytosis (GFAP immunoreactivity), microgliosis (Iba1 immunoreactivity), perivascular macrophage CD163 immunoreactivity, and rating of microhaemorrhages (Perls’ Prussian blue staining for ferric iron in haemosiderin) were conducted semiquantitatively as we have previously reported.33,34,50 Specific details regarding the quantitative analyses are listed in the Supplementary material. Additionally, sectioned samples (8 µm) of the liver, kidney, and spleen were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for histological safety assessments following routine protocols.

Biochemical assessment of amyloid-β and tau pathology in the brain

Brain homogenization and tissue fractionation for biochemical analyses

Homogenates of brain tissue (10% w/v) from selected cortical regions (prefrontal cortex, temporal cortex, and occipital cortex) and the hippocampus of the left hemispheres were processed for extraction of soluble and insoluble fractions of amyloid-β and tau species, and for biochemical analyses (ELISA, Luminex) as previously published.33,51 Detailed methodology is described in the Supplementary material.

MILLIPLEX magnetic bead panel for amyloid-β and tau levels

The levels of amyloid-β40, amyloid-β42, pT181, and t-tau within total [formic acid (FA)] and soluble [diethylamine (DEA)] brain extracts were assessed using a MilliplexMAP Human amyloid-β and Tau Magnetic Bead Panel (MilliporeSigma) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For further information on sample dilution and analysis, refer to the Supplementary material.

Sandwich ELISAs for pyroglutamate AβpE3, aggregated amyloid-β total tau and phosphorylated tau levels

Quantitative determination of pyroglutamate amyloid-β levels in total (FA extract) and soluble (DEA extract) brain fractions was performed using Human AβpE3-40 and AβpE3-42 Assay kits (IBL America) according to manufacturer’s instructions and as previously reported.52 The levels of amyloid-β aggregates within a soluble brain fraction (100 000g; high speed supernatant fraction) were determined using Human Aggregated Aβ ELISA kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s manual and as previously described.34,53 The levels of human tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (pT181), threonine 231 (pT231), and total tau (t-tau) in 20 000× brain supernatant of 10% brain homogenate (S1 fraction) were quantified using Human tau ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and as we have previously published.33,54 See Supplementary material for more detailed methods.

Blood collection

Blood samples were collected in EDTA coated collection tubes from the femoral vein of CpG ODN and saline-treated study animals. Blood was centrifuged at 4°C (485g for 5 min) and all plasma samples were stored at −80°C until further use. All blood samples were taken from awake, un-anaesthetized, animals. Blood sampling volumes were approved by the IACUC and the clinical veterinarian.

Clinical laboratory measures

Routine blood haematology and biochemistry screens were performed at specific intervals throughout the course of the treatment, at 48 h or Day 7 after selected CpG ODN or saline injection, and at the time of euthanasia. EDTA whole blood samples were collected (BD Vacutainer) and haematology parameters were measured at the KCCMR on an Advia 120 Hematology Analyzer (Siemens). Additional blood was collected in serum collection tubes (BD Vacutainer) and processed. Serum samples underwent biochemistry analysis on a Beckman Coulter AU680® Chemistry Analyzer.

Immune response analyses

Peripheral cytokine/chemokine induction and autoantibody responses towards amyloid-β40/42 were evaluated in plasma samples. Animals were bled prior to first injection, at multiple intervals after specific CpG ODN or saline injections, and at the time of euthanasia. Since only limited volumes of blood can be collected because of the small size of squirrel monkeys, the peripheral immune responses were determined in plasma at selected times throughout the treatment period (see below).

Cytokine/chemokine assays

Cytokine/chemokine profiles in plasma from CpG ODN-treated and control animals were analysed using Luminex technology (Th1/Th2 NHP Multiplex Magnetic Bead Panel, 9 Plex) (MilliporeSigma). Plasma cytokines were screened in samples collected prior to first injection, and over a period of 14 days at five distinct time points (10 h, 24 h, 48 h, Day 7, and Day 14) following two representative injections (at Months 1 and 16) of CpG ODN or saline (vehicle). T final (at the time of euthanasia) was collected 1 month after the last injection. A custom 9-plex detection kit, which measured IL6, IL10, MCP1, TNFα, IFNγ, IL13, IL1RA, IL1β, and IL12p40 was used following the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously published.34,55 See Supplementary material for further details.

Amyloid-β autoantibody response

Plasma collected at specific times throughout the course of treatment (at baseline, Months 2, 5, 12, and T final) was examined for the presence of autoantibodies against amyloid-β40 and amyloid-β42 using ELISA as described previously.33,50 Immulon 2HB 96-well microtiter plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coated with 50 µg/plate of the amyloid-β40/42 peptides (4°C overnight). Plasma at dilutions of 1:150 was applied to plates for 2 h (room temperature) after a 2 h blocking with 1.5% soy milk. The bound antibodies in plasma were detected by a goat anti-human IgG HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, Inc.) at 1:5000 dilution. TMB was used as substrate, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using SpectraMAX 200 spectrophotometer.

Assessment of plasma amyloid-β species: Aβ42, Aβ40, AβpE3

Plasma amyloid-β40, amyloid-β42 and N-terminally truncated pyroglutamate amyloid-β (AβpE3) levels were measured at two time points during the second half of the treatment period (at Months 17 and 20), and during the post-treatment behavioural assessment, in a double-antibody sandwich ELISA as previously reported.56,57 Detailed methodology is described in the Supplementary material.

Statistical analysis

Details of statistical testing are provided in the results sections below. Parametric statistical tests, ANOVA or t-test (Student’s or Welch’s unpaired t-test), were used to compare normally distributed measures between CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated monkeys. Student’s t-test was used when the two independent groups had equal variances, and Welch’s t-test was used otherwise. When datasets were not normally distributed, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for independent groups was used instead of a t-test (biochemical assessment of amyloid-β levels in the brain).

The choice of one-tailed or two-tailed tests depends on the existence of prior evidence for directionality. More specifically, when published evidence strongly indicated that one-directional results should be expected, we used one-tailed tests. In the absence of strong prior evidence of directionality, two-tailed tests were used. In the instance of fibrillar amyloid depositions, a fraction of total amyloid burden depicted by thioflavine-S and pyroglutamate (AβpE3) immunohistochemistry, one-tailed t-test was performed to analyse expected change in a downward direction based on the results obtained with total amyloid burden quantification (see ‘Histological assessment of amyloid burden' section below). Reduced amyloid-related pathology was also anticipated based on existing literature from our past studies and those of others.14,33–35 Two-tailed tests were used for the analyses of tau pathology, plasma amyloid-β levels, brain microhaemorrhages, gliosis, and CD3 T lymphocytes, when the particular direction of outcomes could not be predicted.

Holm-Sidak correction was performed when multiple t-test analysis was run (plasma cytokine responses). In those instances where measurements were taken repeatedly from the same monkey, a repeated measures ANOVA test was used. The large datasets were subjected to a multivariate ANOVA to obtain an overall significance before the univariate ANOVAs were used in each individual subgroup to control for experimental-wise error levels (behavioural studies and autoantibody levels). All statistical analyses were completed using the SPSS v26 (IBM Corp. Released 2019, Armonk, NY) and GraphPad Prism v8.4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA USA, www.graphpad.com) software. The results were considered statistically significant if the tests resulted in a P-value of less than 0.05.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors, upon reasonable request.

Results

Assessment of safety

Animals used in our chronic treatment study were continuously monitored for potential toxicity [e.g. physical examination, weight and temperature measures, clinical laboratory screens (haematology and biochemistry)]. Routine observations by trained technical staff and veterinarians indicated that the animals were in good health. We did not observe any adverse events throughout the long-term CpG ODN treatment. Two control animals and one CpG ODN-treated animal were euthanized near the end of the treatment period due to natural causes associated with ageing. There was no indication that the premature death in the CpG ODN group was related to our treatment. All samples collected from these animals (in vivo and post-euthanasia) were included in our analyses, since the animals died in the final months of treatment. In addition, gross examination of organs indicated normal weight, size, and configuration in squirrel monkeys treated with CpG ODN. Further histopathological assessment of peripheral organs (e.g. liver, kidney, spleen) concluded that adverse systemic immunostimulation of CpG ODN did not occur during our long-term study. Overall, the assessment of peripheral toxicity combined with clinical examinations and laboratory screens further validated the safety of this novel concept of immunotherapy.

Behavioural studies

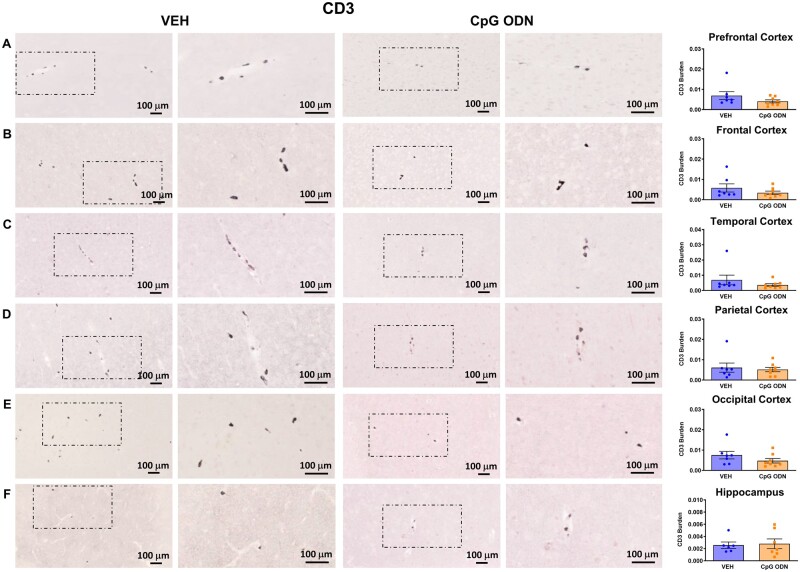

The elderly squirrel monkeys (19–21 years of age) underwent a battery of behavioural tests during the final months of treatment. Prior to cognitive assessment, both treatment groups were subjected to a locomotor activity test to verify that any CpG ODN treatment effects observed in the cognitive tasks could not be explained by differences in locomotor abilities. As shown in Fig. 1A, no significant differences were observed between treatment groups in their locomotor performance. Learning and memory was evaluated using an Inhibitory Control of Behaviour test. The calculated percentage of error attempts were compared across age and treatment groups (Fig. 1B). The results were analysed using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures to compare the post-treatment effects of CpG ODN administration to vehicle-treated animals and young control animals. A Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used to assess simple main effects of treatment within each session. There were no significant differences in error rate during the first session, the initial presentation of the task. Age effect on cognitive abilities was observed as the young cohort performed with overall fewer attempt errors than both CpG ODN-treated (young versus CpG ODN, P < 0.05) and vehicle-treated (young versus vehicle, P < 0.05) old monkeys during the second session where the opening remained on the same side as the first session. No significant differences were detected in the third session, where the opening was rotated 180°, suggesting all the animals had difficulty adjusting to the shift. During the fourth session the vehicle-treated old monkeys performed with significantly more errors than both the CpG ODN-treated old monkeys (vehicle versus CpG ODN, P < 0.05) and the young monkeys (vehicle versus young, P < 0.05). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between our old CpG ODN-treatment group and young monkeys. Hence, our novel immunotherapeutic approach was effective in reducing fourth session error rates in old monkeys compared to age-matched control animals. Spatial learning (working memory) was assessed using a Delayed Nonmatching-to-Sample T Maze test. A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was conducted to compare differences between the two treatment groups (CpG ODN versus vehicle) and across delays. Our post-treatment analyses across four trials revealed a statistically significant interaction between the treatment effect and time (P < 0.05). No group differences in the number of correct and incorrect choices were observed with shorter delays (5 and 10 min). However, CpG ODN-treated monkeys showed significantly greater response accuracy with a longer delay (20 min; CpG ODN versus vehicle, simple-main effect ANOVA, P < 0.05). Data are presented as percentage of incorrect choices across four trials at 5, 10, and 20-min time delay points (Fig. 1C). Overall, post-treatment behavioural assessment in our old cohort demonstrated cognitive improvement in CpG ODN-treated animals.

Figure 1.

Behavioural assessment. (A) Post-treatment locomotor activity test did not reveal significant differences in locomotor abilities between CpG ODN and vehicle elderly monkeys (VEH). (B) Learning and memory was assessed using an Inhibitory Control of Behaviour test. Results are expressed as the percentage of error attempts summed across 14 days. No significant differences in error rates were detected between groups during the first session, the initial presentation of the box opening. Age related differences in cognitive abilities were demonstrated as the young treatment-naïve animals performed with overall fewer reach attempt errors towards the incorrect size of the box than both CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated old monkeys (VEH-old) during the second test session. There were no group differences in the third session, where the box-opening orientation was reversed. During the fourth session, the CpG ODN-treated old monkeys executed the task with significantly less error attempts compared to age-matched control animals. Furthermore, no significant differences were observed between our old CpG ODN animals and young control group. Vehicle-treated old monkeys completed the task with significantly more errors compared to young cohort. (C) Spatial working memory was evaluated using a Delayed Nonmatching-to-Sample T Maze test. Long-term treatment with CpG ODN led to improvement in spatial working memory in our aged cohort, as demonstrated by CpG ODN-treated monkeys navigating the maze with significantly fewer incorrect responses than control animals at 20-min delay. No differences were detected between our treatment groups with shorter delays (5- and 10-min time delays). Results are reported as percentage of incorrect choices across four trials at 5, 10, and 20-min time delay points. Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance: *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.

Amyloid pathology

Histological assessment of amyloid burden

Aged squirrel monkeys were euthanized at 19–21 years of age after behavioural testing and their brains were processed for histology. Results obtained during quantitative histological evaluation were analysed using an unpaired t-test to compare CpG ODN-treated animals to vehicle-treated animals. Total amyloid burden was quantified on serial coronal sections immunostained with anti-amyloid-β 6E10/4G8 antibodies. Reduced amyloid-β burden was observed in all analysed brain regions of CpG ODN-treated animals compared to vehicle controls (Fig. 2A–F). Higher magnification images are presented in Supplementary Figs 1A–F and 2A–D.

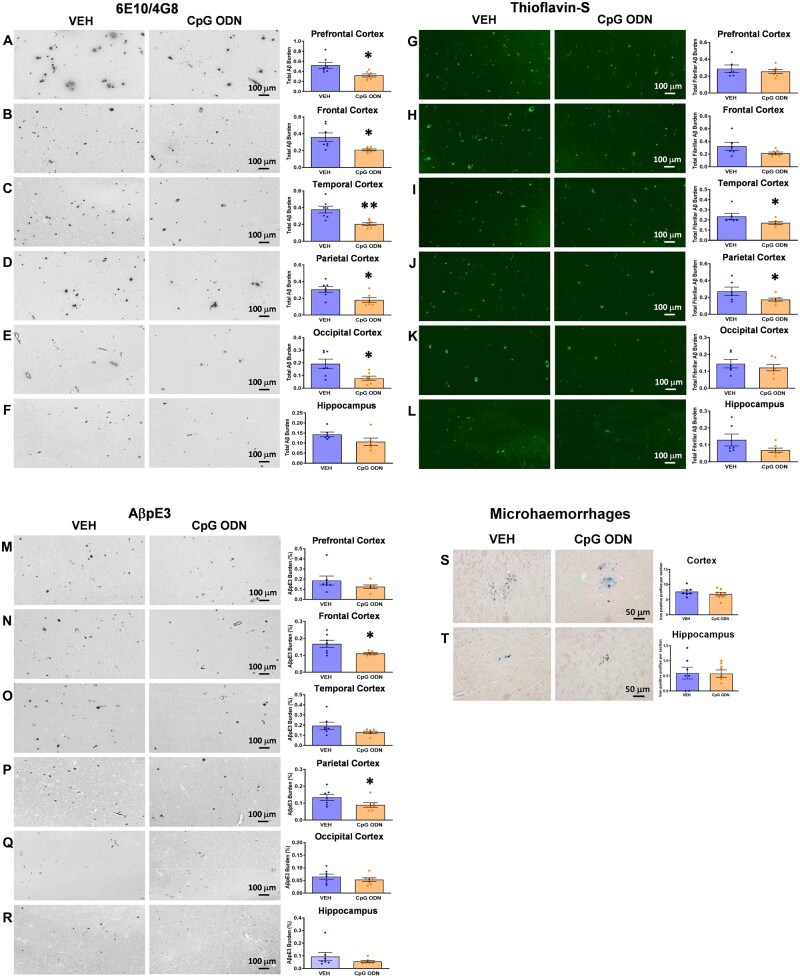

Figure 2.

Total amyloid and fibrillar amyloid burden. (A–F) Total amyloid burden. Immunohistochemistry of 6E10/4G8 showed a notable reduction in total amyloid burden in all analysed cortical and hippocampal brainregions in CpG ODN-treated animals compared with vehicle-treated animals (saline controls). ImageJ quantitative assessment of total amyloid burden revealed a significant 39% reduction in the prefrontal cortex (A), 42% in the frontal cortex (B), 46% reduction in the temporal cortex (C), 41% in the parietal cortex (D), and 59% in the occipital cortex (E). (F) Although not significant, a 26% reduction was observed in the hippocampus. (G–L) Total fibrillar amyloid burden. Thioflavin-S staining and subsequent ImageJ quantitative analysis demonstrated region-specific reductions in total fibrillar amyloid burden (predominantly CAA) between CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated animals. There was a significant 27% reduction in the temporal cortex (I) and a 36% reduction in the parietal cortex (J) in the CpG ODN group. Although not significant, a trend for reduction by 34% and 47% in fibrillar amyloid levels was detected in the frontal cortex (H) and in the hippocampus (L), respectively. No statistical differences between our treated and control monkeys were detected in prefrontal (G) and occipital cortical regions (K). (M–R) Pyroglutamate amyloid-β burden (AβpE3). Treatment with CpG ODN significantly lowered AβpE3-positive deposits (parenchymal and CAA) by 33% in the frontal cortical brain region (N) and by 33% in the parietal cortex (P), while there was a trend for reduction by 34% in total AβpE3 burden in the temporal cortex (O). No significant differences were detected between our treated and control animals in prefrontal (M) and occipital (Q) cortical brain regions and in the hippocampus (R). (S and T) Brain microhaemorrhages. Representative brain sections stained with Perls’ stain for ferric iron in haemosiderin indicated cerebral bleeding. Semiquantitative analysis did not reveal significant differences in the extent of CAA-associated cortical (S) or hippocampal (T) microhaemorrhages between our treatment groups. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Significance: **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05. Scale bars = 100 µm. VEH = vehicle.

Quantitative assessment (ImageJ V1.48) of total amyloid-β burden revealed significant reductions in defined brain regions such as prefrontal cortex (39% reduction; two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A), frontal cortex (42% reduction; two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B), temporal cortex (46% reduction; two-tailed t-test, P < 0.01; Fig. 2C), parietal cortex (41% reduction; two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2D), and occipital cortex (59% reduction; two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2E). Although not significant, a mild 26% reduction of total hippocampal amyloid burden was observed in the CpG ODN group compared to controls (Fig. 2F). Thioflavin-S staining depicted fibrillar amyloid depositions, which in this model correspond almost exclusively to the vascular amyloid burden. Reductions in the total fibrillar amyloid burden were observed in specific brain regions in CpG ODN-treated animals compared to saline controls (Fig. 2G–L). Quantitative analysis within the temporal cortex showed a significant reduction in the CpG ODN group (27% reduction; one-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2I). A 36% significant reduction (one tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2J) was noted in the parietal cortex. Furthermore, peripheral administration of CpG ODN led to a trend for reduction of total fibrillar amyloid burden in the frontal cortex (34% reduction; one-tailed t-test, P = 0.0503; Fig. 2H) and in the hippocampus (47% reduction; one-tailed t-test, P = 0.058; Fig. 2L). No significant differences between treatment groups were observed in prefrontal and occipital cortical regions (Fig. 2G and K). Pyroglutamate (AβpE3) is a post-translationally modified form of amyloid-β that is specific to deposited amyloid plaques.58 Here we report AβpE3 immunohistochemistry of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cortical and hippocampal brain sections from aged S. boliviensis boliviensis. In addition to observed amyloid-β 6E10/4G8 plaques, AβpE3-positive deposits in the form of CAA and parenchymal plaques were detected (Fig. 2M–R). Our quantitative analysis within the frontal cortex showed a significant 33% reduction in AβpE3 burden in CpG ODN-treated monkeys (one-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2N). A 33% significant reduction (one-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 2P) was detected in the parietal cortical region of CpG ODN animals. Further data revealed a trend for decreased AβpE3 burden in the temporal cortex (34% reduction; one-tailed t-test, P = 0.059; Fig. 2O) in CpG ODN-treated monkeys. Measurements of AβpE3-positive deposits in prefrontal (Fig. 2M) and occipital (Fig. 2Q) cortical brain regions and in the hippocampus (Fig. 2R) did not reveal significant differences between our treatment groups.

The integrity of cerebral vessels was examined using the Perls’ stain method that detects ferric iron in haemosiderin, indicating cerebral bleeding. Semiquantitative analysis of iron-positive profiles per brain section indicated no evidence of increased cerebral microhaemorrhages in cortical or hippocampal regions of CpG ODN-treated animals providing further evidence of the safety of our approach (Fig. 2S and T).

Biochemical assessment of amyloid-β levels in the brain

Multiple biochemical analyses were performed to further examine the extent of amyloid pathology after CpG ODN administration. Reduced amyloid-β-related pathology was anticipated according to our published evidence,33–35 thus changes in a downward direction were also expected for biochemical measures. The datasets were not normally distributed; hence, instead of using a one-tailed t-test, we used a one-tailed Mann-Whitney non-parametric test to compare the CpG ODN-treated group to vehicle-treated control group. Luminex platform assays revealed a statistically significant reduction in the levels of total (FA extracted) amyloid-β42 species (one-tailed Mann-Whitney test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3A) and soluble (DEA extracted) amyloid-β42 species in the prefrontal cortex (one-tailed Mann-Whitney test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B) in CpG ODN-treated animals. Brain pyroglutamate amyloid-β levels were examined by ELISA. CpG ODN treatment significantly decreased the levels of total (FA extracted) AβpE3-42 species in the prefrontal cortex (one-tailed Mann-Whitney test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). No group differences were detected in the remaining brain regions. The levels of AβpE3-42 in the DEA brain extracts were unaffected. Further quantitative measurements of amyloid-β40 and AβpE3-40 levels in the FA-extracted and DEA-extracted samples of 10% brain homogenate showed no significant differences between our treatment groups (data not shown). Our subsequent ELISA analysis of aggregated amyloid-β species in the soluble brain fractions did not reveal differences between our treated and control animals (data not shown). Despite a less extensive treatment effect observed with biochemistry, our data demonstrate that stimulation of innate immunity with CpG ODN was effective in ameliorating amyloid-β42/AβpE3-42 species in the prefrontal cortex, the cortical region with the greatest amyloid burden.39

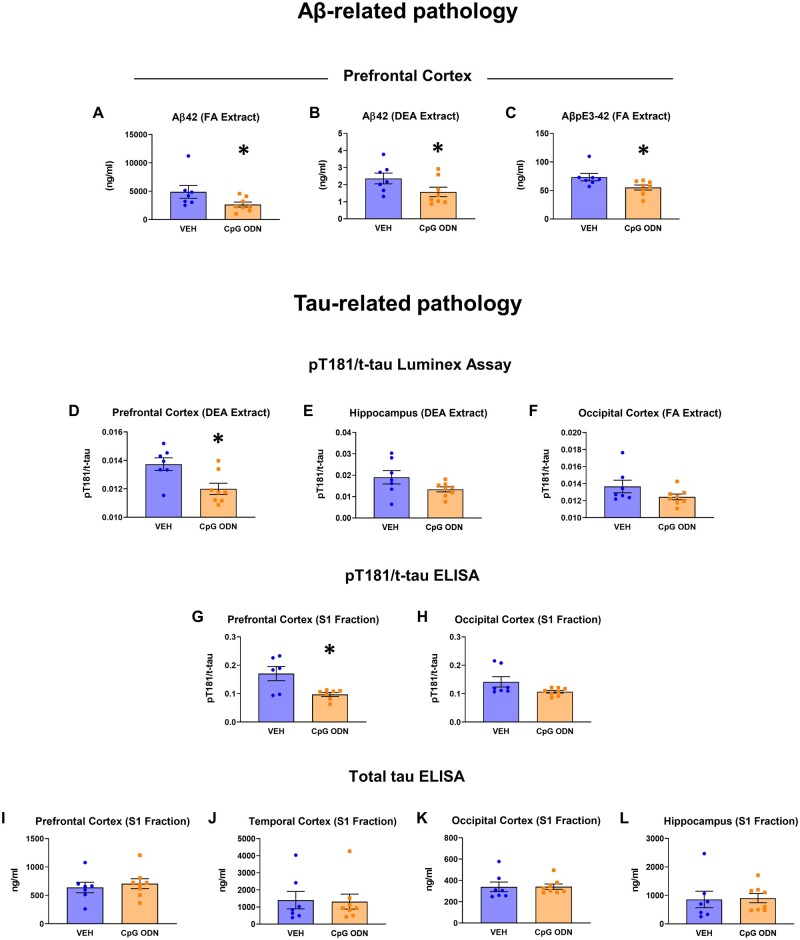

Figure 3.

Biochemical analysis of brain amyloid-β levels, and phosphorylated and total tau levels. (A–C) Biochemical analysis of brain amyloid-β levels. CpG ODN treatment significantly decreased total (FA extracted) amyloid-β42 (Aβ42) levels (A) and soluble (DEA extracted) amyloid-β42 levels (B) in the prefrontal cortex, as assessed by Luminex technology. (C) ELISA measurements of total (FA extracted) AβpE3-42 species revealed significant reduction in the prefrontal cortex in CpG ODN monkeys. (D–L) Biochemical analysis of phosphorylated and total tau levels. (D) Luminex assessment of pT181 to total tau (t-tau) ratio (pT181/t-tau) in DEA extracted soluble brain fraction indicated significant reduction in the prefrontal cortex in CpG ODN-treated animals. (E) Measurements of soluble pT181/t-tau in the hippocampus revealed a notable reduction; however, group differences did not reach significance. (F) Reduced levels of pT181/t-tau measured in FA extracted brain fraction were observed in the occipital cortical region of CpG ODN animals, although not statistically significant. (G) Subsequent ELISA analysis of pT181/t-tau in 20 000g brain supernatant fraction (S1) revealed a significant reduction in the prefrontal cortex, while a mild, but not significant reduction, was detected in the occipital cortex in CpG ODN monkeys (H). (I–L) No differences in total tau levels (t-tau) assessed by ELISA were detected in all analysed brain regions between our treated and control animals. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Significance: **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.VEH = vehicle.

Tau pathology

Biochemical assessment of phosphorylated and total tau levels in the brain

Although tauopathy is rare in aged squirrel monkeys,39,59 we performed biochemical analyses of tau pathology to confirm that immunomodulation via TLR9 agonist, CpG ODN, did not lead to an induction of tau-related pathology, in contrast to prior studies using TLR4 agonists (lipopolysaccharide).60,61 An unpaired two-tailed t-test was performed to compare CpG ODN-treated animals to vehicle-treated animals. Quantitative biochemical evaluation of tau phosphorylated at threonine 181 (pT181) and total tau (t-tau) levels in DEA (soluble) and FA (total) brain fractions was first performed by Luminex Technology. The ratio of pT181 to t-tau (pT181/t-tau) in DEA extracted brain fraction was significantly reduced in the prefrontal cortex (two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3D); furthermore, a notable, although not significant, reduction of soluble pT181/t-tau was detected in the hippocampus (Fig. 3E) in CpG ODN-treated animals. Reduced levels of pT181/t-tau measured in FA extracted brain fraction were observed in the occipital cortical region of CpG ODN animals; however, the differences between treatment groups did not reach significance (Fig. 3F). Additional ELISA analysis in 20 000g brain supernatant fraction (S1) indicated a significant reduction in pT181/t-tau levels in the prefrontal cortex (two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 3G) in CpG ODN animals. Although not statistically significant, a mild reduction of pT181/t-tau levels were detected in the occipital region of CpG ODN-treated animals (Fig. 3H). Remaining brain regions did not reveal differences between the treatment groups. The levels of tau phosphorylated at threonine 231 (pT231) in the S1 fraction were unaffected, as assessed by ELISA (data not shown). Furthermore, total tau levels remained unchanged in all analysed brain regions in CpG ODN animals when compared to vehicle group (Fig. 3I–L). Overall, our analyses indicated that chronic treatment with Class B CpG ODN does not lead to an increase in phospho-tau pathology and changes in total tau levels, supporting the safety and validity of our approach.

Plasma amyloid-β levels

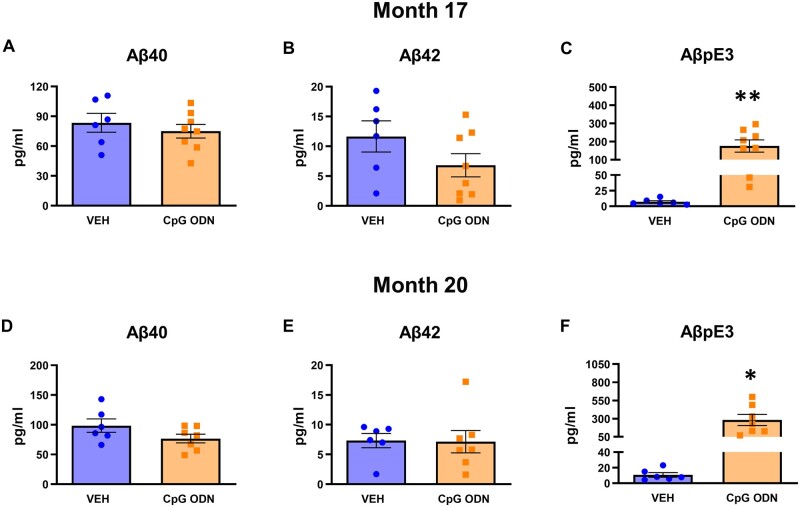

Plasma amyloid-β species levels were assessed during the second half of the treatment period (at Months 17 and 20) in blood samples collected prior to post-treatment behavioural assessment. Results were analysed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test to compare CpG ODN-treated animals to vehicle-treated animals. The presence of amyloid-β40/42 was assayed using an in-house ELISA. No differences in amyloid-β40/42 plasma levels were detected between our treatment groups at measured post-injection time -points (Fig. 4A, B, D and E). Furthermore, we investigated whether treatment with CpG ODN would result in AβpE3 efflux from the CNS to the periphery and an increase of AβpE3 in plasma of squirrel monkeys. AβpE3 is normally undetectable in plasma.62,63 Our biomarker analyses revealed a significant increase in AβpE3 plasma levels in the CpG ODN-treated group (Month 17: two-tailed t-test, P < 0.01; Month 20: two-tailed t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 4C and F), indicating clearance of deposited post-translationally modified amyloid-β into the systemic circulation.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of plasma amyloid-β levels. (A, B, D and E) Plasma amyloid-β species were determined at two time points during the later months of the chronic treatment period. No differences in amyloid-β40/42 (Aβ40/42) plasma levels were noted between our CpG ODN-treated animals and control group at analysed post-injection time points. (C and F) As further assessed by ELISA specific to N-terminally truncated pyroglutamate AβpE3, CpG ODN treatment led to a significant increase of AβpE3 levels in plasma collected from aged squirrel monkeys at Months 17 and 20, indicating efflux of this post-translationally modified amyloid-β into the systemic circulation. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Significance: **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05. VEH = vehicle.

Associated histopathology

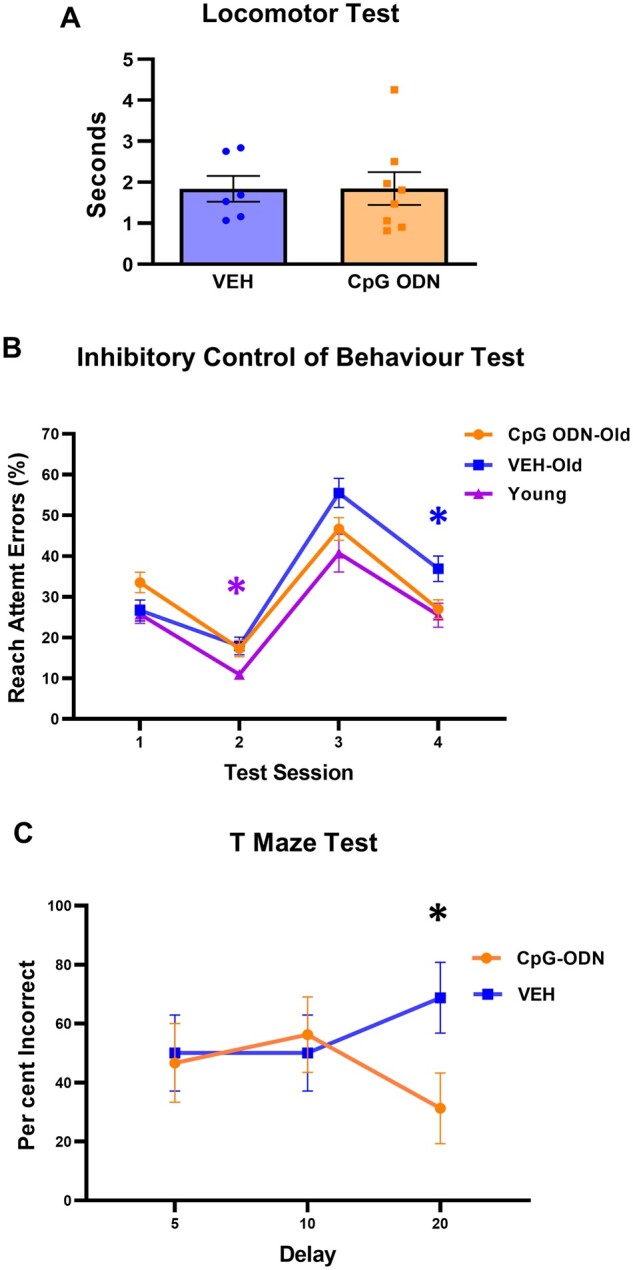

Histological assessment of microgliosis, astrogliosis, and CD3-positive T lymphocytes

Evaluation of CpG ODN effect on glial activation to assess for potential signs of cerebral toxicity was performed at the end of the treatment, one month after the last CpG ODN injection. Data were analysed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test to compare CpG ODN-treated animals to vehicle-treated animals. The assessment of Iba1, a generic microglia marker commonly used to label all microglia population whether resting or activated, was based on semiquantitative analysis of the extent of microgliosis.64 There were no apparent differences in Iba1 immunoreactive cells between CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated animals in all analysed cortical and hippocampal brain regions (Fig. 5A–F). Higher magnification images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3A–F. The presence of CD163 expressing perivascular macrophages was examined due to their close proximity to vascular amyloid and continuous turnover in the CNS.65,66 Our histological observation and semiquantitative rating of CD163 reactive perivascular macrophages in all defined brain regions did not reveal group differences (Fig. 5M–R). Additionally, CAA was associated with GFAP immunoreactive astrocytes. Subsequent semiquantitative analysis for astroglial marker GFAP showed no differences between our treatment groups (Fig. 5G–L). Higher magnification images are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4A–F. To assess if any neuroinflammation was induced, the brains were examined for the presence of lymphocytic infiltration. CD3 immunohistochemistry indicated the presence of T lymphocytes in all monkeys at the end of the study. However, quantification (ImageJ V1.48) of CD3-positive T lymphocytes in all brain regions did not reveal significant differences between CpG ODN-treated and control animals. Hence, CpG ODN immunostimulatory effect was not associated with increased T-cell infiltration in any brain region of aged squirrel monkeys (Fig. 6A–F). Overall, no signs of CpG ODN treatment associated sustained neuroinflammation were present in our elderly animals at the end of the chronic treatment period.

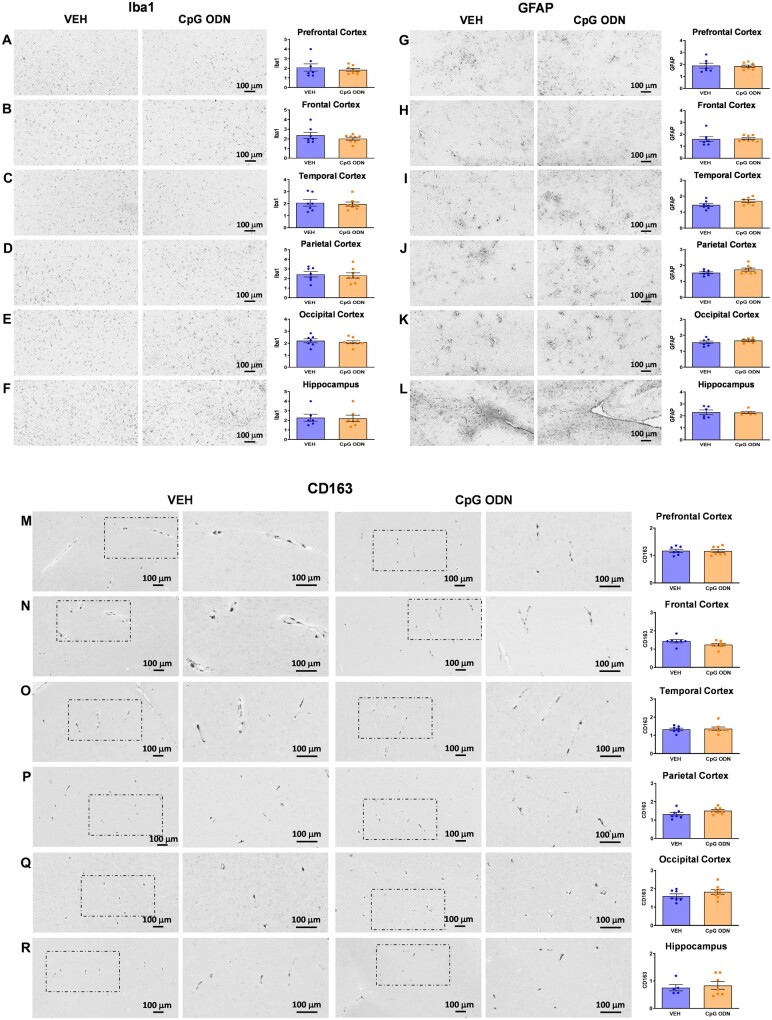

Figure 5.

Assessment of Iba1, GFAP, and CD163 immunoreactivity. Histological observation and semiquantitative rating of generic microglial marker Iba1 (A–F), astroglial marker GFAP (G–L), and perivascular macrophage activation marker CD163 (M–R), indicated no statistically significant differences between CpG ODN-treated and control animals in all analysed cortical and hippocampal brain regions at the end of the treatment period. The degree of Iba1, GFAP, and CD163 immunoreactivity was graded on a scale of 0–4. Columns 2 and 4 in rows M–R (CD163) are higher magnifications of boxed areas in columns 1 and 3, respectively. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Scale bars = 100 µm. VEH = vehicle.

Figure 6.

Assessment of CD3 immunoreactivity. ImageJ quantitative analysis of CD3-positive T lymphocytes did not reveal statistically significant differences between CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated animals in all cortical and hippocampal brain regions at the end of the treatment period. Columns 2 and 4 in rows A–F (CD3) are higher magnifications of boxed areas in columns 1 and 3, respectively. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Scale bars = 100 µm. VEH = vehicle.

Immune response monitoring

Plasma cytokine/chemokine responses

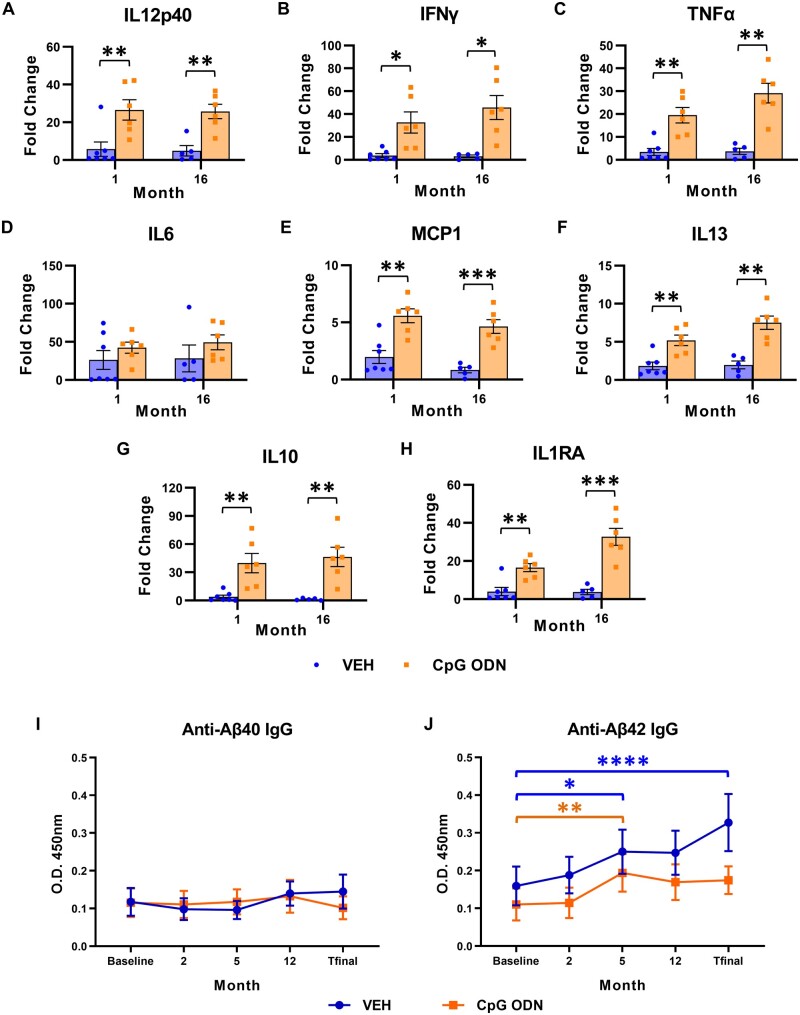

We next examined whether peripheral administration of CpG ODN in aged squirrel monkeys where immune system might be compromised was effective in inducing beneficial immunostimulatory response in the absence of any inflammatory toxicity. Cytokine/chemokine profiles were evaluated in plasma samples collected prior to first injection (baseline, T0) and at multiple intervals (10 h, 24 h, 48 h, Day 7, Day 14) following CpG ODN or saline subcutaneous administration using Multiplex NHP cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead panel. Since the small size of squirrel monkeys limits the volume of blood that can be collected at any time point, the peripheral immune responses were assessed at selected months throughout the treatment period. Data are presented as the fold change of maximum cytokine levels (pg/ml) induced after CpG ODN or saline injection versus cytokine levels detected at baseline (T0). Plasma cytokine profiles assessed during two representative injections (at Months 1 and 16) are shown in Fig. 7. Statistical analyses of cytokine levels were performed using multiple t-tests with Holm-Sidak correction to compare the means between CpG ODN- and vehicle- treated groups. Our subjects showed a significant induction of IL12p40 (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.01; Fig. 7A), IFNγ (Month 1: P < 0.05; Month 16: P < 0.05; Fig. 7B), and TNFα (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.01; Fig. 7C) plasma levels in response to CpG ODN compared with saline animals. No significant increase was detected in IL6 plasma levels post-CpG ODN administration when compared to control animals at Months 1 and 16 (Fig. 7D). IL1β, a potent inflammatory cytokine, was detectable at very low levels and exhibited no significant changes between the groups (data not shown). Slightly more modest but significant elevations were observed in circulating levels of MCP1 chemokine (monocyte chemotactic protein-1, also known as CCL2) (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.001; Fig. 7E) and IL13 (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.01; Fig. 7F) plasma levels in the CpG ODN group compared to controls. Furthermore, the plasma levels of potent anti-inflammatory cytokines IL10 (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.01; Fig. 7G) and IL1RA (Month 1: P < 0.01; Month 16: P < 0.001; Fig. 7H) were also significantly induced in CpG ODN-treated animals compared to vehicle group. Separate plasma cytokine analyses were performed at the time of euthanasia, 1 month after the last subcutaneous CpG ODN or saline injection. As expected, the cytokine/chemokine levels subsided over time and no significant differences were found between our treatment groups at the end of the study (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Longitudinal assessment of plasma cytokine/chemokine responses and plasma amyloid-β autoantibody levels. (A–H) Longitudinal assessment of plasma cytokine/chemokine responses. Th1/Th2 cytokine/chemokine Multiplex assay in the Luminex platform was used to evaluate peripheral cytokine profiles following CpG ODN or saline subcutaneous administration throughout the long-term treatment period. Results are expressed as fold change determined by dividing the maximum cytokine levels detected after specific CpG ODN/vehicle injections by the cytokine levels detected at baseline (T0, prior to injection). Data represent cytokine responses evaluated in plasma samples collected during two representative injections at Months 1 and 16. Significant increases in circulating (A) IL12p40, (B) IFNγ, (C) TNFα, (E) MCP1, (F) IL13, (G) IL10, and (H) IL1RA plasma levels were detected in response to CpG ODN as compared with vehicle-treated monkeys at all measured times. (D) No significant elevation in IL6 levels post-CpG ODN injection was observed at Months 1 and 16. (I and J) Longitudinal assessment of plasma amyloid-β autoantibody levels. Autoantibody responses towards amyloid-β40/42 (anti-Aβ40/42) were examined in plasma samples at five specific times (at baseline, Months 2, 5, 12, and T final) throughout the course of treatment by ELISA. No statistically significant differences in the levels of plasma anti-amyloid-β40 IgG were detected within each treatment group across time. (I) Periodical evaluations did not reveal differences between the CpG ODN and vehicle-treated animals. Both treatment groups displayed elevated anti- amyloid-β42 IgG plasma levels at Month 5 compared to baseline levels; however, no further increase was observed at later injections, including at the time of euthanasia (T final) in the CpG ODN group. (J) No differences were found in amyloid-β42 autoantibodies at the end of the study as compared with the beginning of the study in CpG ODN animals. Conversely, a further increase in anti-amyloid-β42 levels was noted in the second half of the treatment period in vehicle-treated animals. T final plasma amyloid-β42 autoantibody levels were significantly higher than baseline levels in the vehicle group. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. Significance: ****P < 0.0001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05. VEH = vehicle.

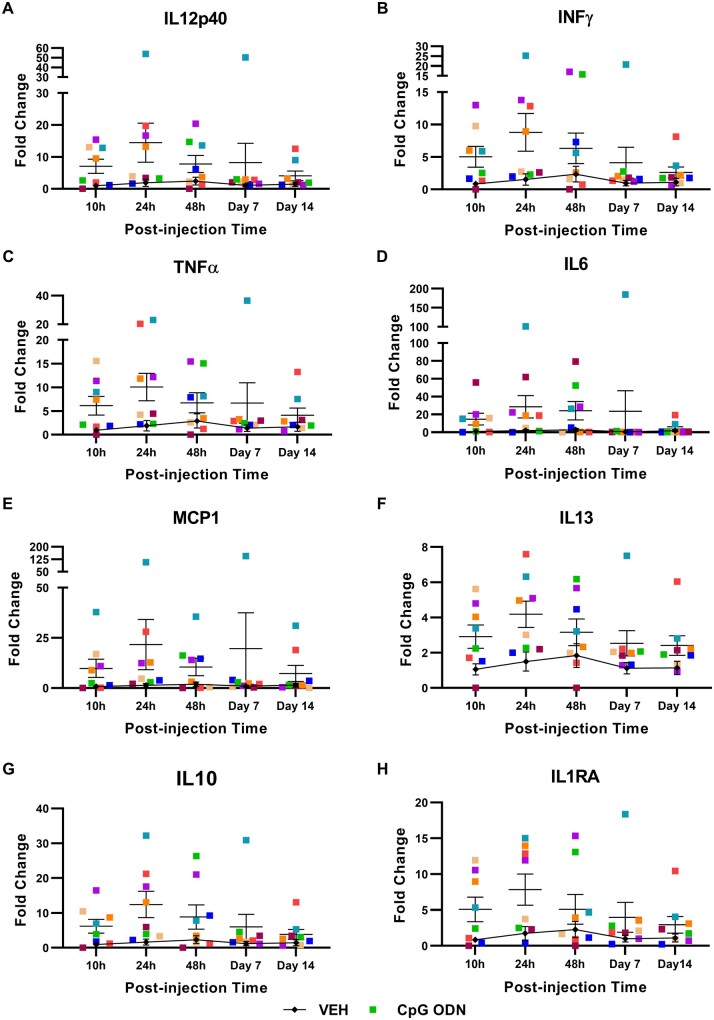

Furthermore, we performed separate analyses to evaluate the kinetic pattern of previously reported cytokine inductions. Plasma cytokines were screened over a period of 14 days at five specific time points (10 h, 24 h, 48 h, Day 7, Day 14) following CpG ODN or saline injection. Data are expressed as the fold changes of plasma cytokine levels detected at individual time points post-CpG ODN or vehicle injection versus plasma cytokine levels examined at the latest collection time point of the preceding injection. Fold changes evaluated in plasma samples collected after the representative injection at Month 12 are shown in Fig. 8A–H. Cytokine responses of individual monkeys are presented at each measured time point. Different kinetic patterns of cytokine induction were observed. In some cases, second cytokine peaks were detected 48 h or 7 days after the early peak. Hence, the cytokine responses showed considerable inter-subject variability in kinetics. As expected, 14 days after the injection, the levels of all analysed cytokines were lower than what was observed in plasma collected at earlier time points post-CpG ODN administration. Present findings demonstrate that stimulation of innate immunity with TLR9 agonist CpG ODN is effective at inducing a suitable degree of immunostimulatory response that reduces the accumulation of amyloid-β-related pathology, without producing excessive and sustained inflammatory environment.

Figure 8.

Plasma cytokine induction kinetics. (A–H) Further analysis was performed to evaluate the kinetic patterns of reported cytokine inductions: (A) IL12p40; (B) IFNγ; (C) TNFα; (D) IL6; (E) MCP1; (F) IL13; (G) IL10; and (H) IL1RA. Kinetic patterns of individual monkey plasma cytokine responses were evaluated over a period of 14 days at five specific time points (10 h, 24 h, 48 h, Day 7, and Day 14) post-CpG ODN or saline injection. Results are expressed as fold change of plasma cytokine levels examined at each measured time point following CpG ODN or vehicle injection versus cytokine levels detected at the last evaluated blood collection time point of the preceding injection. Data are shown as fold change of cytokine responses assessed in plasma collected after the representative injection at Month 12. Even though the cytokine responses showed inter-subject variability, an evident increase in all analysed cytokines/chemokines was observed in CpG ODN animals compared to saline group. (A–H) As expected, reduced cytokine levels were detected in plasma collected 14 days after the CpG ODN injection Hence, stimulation of innate immunity with CpG ODN was effective in inducing immunostimulatory response in the absence of prolonged and excessive inflammatory environment. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. VEH = vehicle.

Amyloid-β autoantibody levels

We next set out to test whether the CpG ODN therapeutic effect had any relationship with the production of anti-amyloid-β autoantibodies. The autoantibody response towards amyloid-β40/42 was assessed periodically throughout our long-term treatment study using an in-house ELISA. Comparisons of amyloid-β40/42 IgG autoantibody levels between the two treatment groups were made at five specific times across the study (at baseline, Months 2, 5, 12, and T final). A two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was conducted to compare differences between the two treatment groups (CpG ODN versus vehicle) and across the time points. If the interaction factor in the model was significantly different from expected, the simple main effects for both, treatment effect at each time point (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) and time point differences within each treatment, (Sidak’s multiple comparison test) are presented. Plasma amyloid-β40 IgG autoantibody levels did not show any statistically significant differences either across time within each treatment group or between the two treatment groups (Fig. 7I). Longitudinal evaluation of plasma amyloid-β42 IgG autoantibody levels revealed a statistically significant interaction between the treatment effect and time [F(4,47) = 2.8, P < 0.05]. Within each treatment group, there were significant changes across time. The vehicle group had a significant rise in anti-amyloid-β42 levels at Month 5 compared to baseline levels (Month 5 versus baseline, P < 0.05; Fig. 7J). Anti-amyloid-β42 levels displayed a further increase in the final months of the treatment period and through to the time of euthanasia (T final). Significantly higher levels of anti-amyloid-β42 IgG were noted in plasma obtained at the end of the study, compared with the beginning of the study, in vehicle-treated animals (T final versus baseline, P < 0.0001; Fig. 7J). Within the CpG ODN-treated group there were significantly higher levels of plasma amyloid-β42 IgG autoantibody at Month 5 compared to baseline (Month 5 versus baseline, P < 0.01). However, anti-amyloid-β42 levels in subsequent months did not differ statistically from each other.Hence, no further increase in the levels of anti-amyloid-β42 was detected at later injections throughout the course of treatment in CpG ODN-treated monkeys. No differences were detected in anti-amyloid-β42 IgG levels at the end of the study compared with the baseline levels in the CpG ODN group. Overall, stimulation of innate immunity with TLR9 agonist, CpG ODN, did not lead to increased generation of plasma anti-amyloid-β40/42 IgG levels. This indicates that the effects of CpG ODN on reducing vascular amyloid burden cannot be attributed to secondary activation of adaptive immunity against amyloid-β.

Discussion

Active and passive immunotherapies have emerged as promising therapeutic interventions for Alzheimer’s disease. However, major challenges of clinically tested immunotherapeutic approaches that mainly target the adaptive immune system include limited clinical benefits, excessive neuroinflammation, and the incidence of CAA-related adverse events.31,67–69 CAA, for which there is no treatment in humans, occurs in nearly all Alzheimer’s disease cases with more than 30% of patients having severe vascular amyloid pathology.70,71 The presence of CAA promotes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease pathology-related clinical symptoms and is also associated with more rapid cognitive decline in non-cognitively impaired subjects.29,72–74 Furthermore, there is a significant interaction between tau pathology and CAA on the severity of cognitive symptoms within the Alzheimer’s disease clinical spectrum.75 In addition, CAA is more resistant to clearance than parenchymal amyloid and may contribute to the development of ARIA identified in trials of anti-amyloid immunotherapy, complications that were not anticipated by numerous studies in transgenic mouse models.32,76,77 These MRI abnormalities include parenchymal vasogenic oedema and sulcal effusion (ARIA-E), and appearance of microhaemorrhage-related haemosiderin depositions (ARIA-H).78,79 Our earlier extensive studies from multiple Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mouse models clearly demonstrate that stimulation of innate immunity via TLR9 with CpG ODN can alleviate all pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, including amyloid plaques, tau pathology, and CAA, in association with behavioural improvements and without any toxicity.33–35 However, a premature leap from studies completed in transgenic mice directly to human trials has been cited as one of the significant reasons for the failure of the vast majority of Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials.36,80

The potential translatability to humans is enhanced by testing our promising therapeutic concept in non-human primates, which more closely resemble Alzheimer’s disease-related pathology. Previous studies established that non-human primates are useful models for exploring the therapeutic potential of CpG ODN planned for human use.81–84 Since TLR9 is expressed in a broader range by immune cells in rodents compared to primates, results from non-human primates are more accurate predictors of human immune responses to CpG ODN.23,25,26 Hence, to expand the extensive work accomplished in transgenic models, we advanced our research using a New World non-human primate model of naturally occurring amyloid pathology—the squirrel monkey. An important feature of cerebral amyloid-β depositions in squirrel monkeys is their predilection for abundant CAA in addition to some parenchymal amyloid depositions.39,42,59,85 The major complication in on-going immunotherapeutic clinical trials is ARIA, which is linked to the presence and degree of CAA. Hence, the prominence of this pathology in aged squirrel monkeys makes them an ideal model to assess for toxicities such as microhaemorrhages, vasculitis, and encephalitis.36,41,42

The interventions described here represent the first study using elderly squirrel monkeys with established CAA pathology to assess the efficacy and long-term safety of a well-characterized TLR9 agonist Class B CpG ODN 2006. This molecule has shown good tolerability in human immunotherapy trials for cancer, infectious diseases, and allergy.25,86,87 The age effect on cognitive performance in the squirrel monkey model and the proper execution of the task protocol were first confirmed on the Inhibitory Control of Behaviour test. Stimulation of TLR9 signalling with CpG ODN in elderly monkeys was effective at improving learning and spatial working memory evaluated on the Inhibitory Control of Behaviour and Nonmatching-to-Sample T Maze tests. Histological evaluation accompanied by quantitative image analysis of total amyloid burden demonstrated significant reductions in all analysed cortical brain regions in CpG ODN-treated monkeys compared to controls. In addition, there was a trend for reduction in the hippocampus. Staining with thioflavin-S shows only the fibrillar component of amyloid depositions. Total fibrillar amyloid burden in this model constitute a fraction of the parenchymal amyloid burden and the entire vascular amyloid burden. Even though fibrillar deposits are less susceptible to clearance, CpG ODN treatment led to significant reductions in temporal and parietal cortical regions. Similar reductions in the degree of thioflavin-S-positive deposits were noted in the frontal cortex and in the hippocampus of CpG ODN-treated animals; however, the quantitative analyses did not reach significance because of inter-animal variability. Pyroglutamate (AβpE3), a post-translationally modified amyloid-β variant that may display higher neurotoxicity and forms fibrils more easily,58,62 was detected in aged squirrel monkeys as a component of parenchymal plaques and CAA. AβpE3 burden levels within the frontal and parietal cortical brain regions were significantly decreased in CpG ODN-treated animals. Although not significant, a comparable degree of reduction was evident in the temporal cortex. The subsequent histological examination of haemosiderin deposits confirmed that CpG ODN did not accelerate microhaemorrhages in contrast to some reports of prior immunotherapeutic applications, enhancing the safety profile of this method of immunomodulation. Our biochemical assessment clearly demonstrated that peripheral administration of CpG ODN was effective in reducing the levels of soluble and total amyloid-β42/AβpE3-42 species in the prefrontal cortex, the cortical region with greatest density of amyloid lesions.39 The levels of amyloid-β40/AβpE3-40 species in the soluble and total brain extracts were unaffected. One potential explanation for a less robust treatment effect observed with biochemistry may be that histological analyses allowed assessment of amyloid-related pathology by quantifying individual immunoreactive deposits present in numerous histological sections per defined brain region, whereas homogenization of a brain region for biochemical analysis may have diluted any measurable changes.

Prior studies have shown that some forms of TLR stimulation can promote an increase in tau pathology.60,61,88 Even though, only occasional tau-immunoreactive neurons and neurites occur in elderly squirrel monkeys,39,59 in the current research, we felt it was critical to evaluate the effect of TLR9 agonist CpG ODN on the extent of tau-related pathology. Long-term treatment with Class B CpG ODN did not promote an increase in phospho-tau pathology in aged monkeys, with biochemical evaluation showing region specific reduction of pT181/t-tau ratio, providing additional validity to our immunomodulatory strategy. Furthermore, total tau levels were not affected by CpG ODN treatment in all analysed brain regions, which was consistent with a lack of toxicity from this therapeutic approach.

The appearance of AβpE3 in plasma has been previously reported as a marker of CNS amyloid clearance, as AβpE3 is normally undetectable in plasma.62,89,90 Chronic administration of CpG ODN resulted in AβpE3 efflux from the CNS to the periphery as indicated by increased AβpE3 plasma levels in aged squirrel monkeys. Hence, our longitudinal plasma analyses identified AβpE3 as a potential biomarker associated with CpG ODN treatment efficacy.

Microglia/macrophage activation responses, as well as potential signs of cerebral inflammatory toxicity associated with CpG ODN treatment were evaluated at the end of the chronic treatment period, 1 month after the last CpG ODN injection. The assessment of Iba1 microgliosis and GFAP astrogliosis revealed no differences in cortical and hippocampal regions comparing CpG ODN-treated and vehicle-treated animals. No alteration in the extent of CD163-reactive perivascular macrophages was observed in CpG ODN animals. Moreover, chronic dosing of CpG ODN did not result in an increased T-cell infiltration in any brain region at the end of the treatment. Hence, overt neuroinflammation was not present in the brains of aged monkeys treated with CpG ODN. Importantly, no inflammatory damage or other signs of adverse reactions were detected in the major peripheral organs of our elderly animals, supporting the safety of our approach.

Dysfunctional/senescent profile of resident microglia and peripherally derived macrophages, characterized by diminished chemotactic and phagocytic activities, occurs with ageing and during Alzheimer’s disease.4,91,92 Modifying the microglia/macrophage activation state rather than inhibiting their function has strong therapeutic promise; however, a greater understanding of the multiple activated cell subtypes and their functional characteristics during different stages of the disease is needed.9,10 CpG ODN role in restricting Alzheimer’s disease pathology via activated microglia/macrophages has been demonstrated.14,18,33,34 In particular, prior reports suggest that CpG ODN stimulation increases myeloid cells lysosomal proteolytic activity, allowing for more efficient degradation of amyloid-β.14,93,94 Since CpG ODNs do not cross the intact blood–brain barrier we recognize the possibility that cytokines/chemokines secreted in the periphery after CpG ODN administration may enter the CNS and have either a direct effect on resident microglia or induce signalling leading to the recruitment of peripheral cells capable of eliminating amyloid-β. Peripherally derived macrophages have been found to enter the brain in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models and are known to be more effective in the clearance of amyloid deposit.95–98 The enhanced clearance of deposited amyloid-β through transient recruitment of peripheral macrophages due to TLR9 stimulation via CpG ODN has been supported in our initial acute studies using transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mouse models.33,34

We next examined whether CpG ODN beneficial effects were partially associated with the secondary activation of adaptive immunity linked to production of autoantibodies against amyloid-β. Plasma IgG autoantibody responses towards amyloid-β40/42 were assessed at baseline and at specific times across the treatment period. No increased generation of anti-amyloid-β40 IgG was noted in our CpG ODN-treated elderly monkeys at any measured time point throughout the course of treatment. Even though a transient increase in plasma anti-amyloid-β42 IgG levels was noticed in the CpG ODN group at Month 5 when compared to baseline, no further increase was identified with continuous monthly injections. Significantly higher plasma levels of amyloid-β42 autoantibodies were detected in our vehicle-treated animals at Month 5 when compared to the beginning of the study. Interestingly, anti-amyloid-β42 levels in plasma obtained from control animals continued to rise through to the end of the study, suggesting a strong immune response against amyloid-β. IgG antibodies directed against amyloid-β are common in Alzheimer’s disease patients; hence, we speculate that the humoral immune response towards amyloid-β may be stronger in our control subjects with higher amyloid-β levels, which is more antigenic.99 Overall, the present data indicates that the effects of CpG ODN on reducing vascular amyloid burden cannot be attributed to the stimulation of a humoral response against amyloid-β.

How to harness innate immunity without stimulating potentially harmful inflammation has become a critical question in Alzheimer’s disease research. Further evidence of CpG ODN activity was obtained by evaluating peripheral cytokine/chemokine profiles. Even though the cytokine responses showed inter-animal variability, elevations of both Th1/Th2 plasma cytokine levels were detected following CpG ODN injection compared to saline controls. Importantly, induction of a potent inflammatory cytokine, IL1β, which has been proposed to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis,88,100,101 was detected at very low levels and no differences were observed between our treated groups with the longitudinal stimulation regimen. The role of the TNFα signalling pathway has been explored in several other studies, and their findings may have contributed to the development of new therapeutic avenues for Alzheimer’s disease (e.g. XPro1595: NCT03943264).102–104 TNFα, a classic proinflammatory cytokine, has been shown to induce memory deficits.105 On the other hand, a neuroprotective effect of the TLR9 stimulation with CpG ODN, which required an increase in TNFα levels, was reported in a model of ischaemic injury.106 Hence, evidence shows TNFα as either a mediator of neuroprotection or a contributor to dysfunction, contingent on the nature of the stimulus, and the magnitude and duration of the response that follows. Additionally, mFPR2, a receptor involved in amyloid-β phagocytosis and clearance, may be stimulated by CpG ODN and TNFα.93,107 We speculate that the significant and transient boost of peripherally derived TNFα caused by CpG ODN in aged squirrel monkeys is likely to have played a partial role in microglia/macrophage migration and the clearance of amyloid-β deposits by phagocytosis. Recently, it has been shown that temporary blocking of inhibitory immune checkpoints or a reduction of the regulatory T cells leads to an IFNγ-dependent increase in monocytes trafficking through the choroid plexus epithelium which correlates with improved cognition and reduction of amyloid-β pathology.95 Hence, we cannot exclude the possibility that IFNγ elevations noted in the CpG ODN group may be involved in the alternative recruitment of peripherally derived myeloid cells to sites of brain pathology. Several lines of evidence implicate aberrant IL10 signalling in Alzheimer’s disease. Chronic overexpression of IL10 has been identified to have adverse effects on amyloid-β deposition.108–110 Significant peripheral elevation of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL10 was observed after CpG ODN injection; however, the levels declined over time. IL10 release was likely reflective of the increase in proinflammatory markers in order to maintain balance/homeostasis.10 Importantly, the effect of CpG ODN on triggering a targeted immune response without producing excessive and prolonged inflammatory environment in elderly monkeys was confirmed by reduced cytokine levels measured 2 weeks post-injection during the treatment period. As expected, the levels of all analysed cytokines/chemokines subsided 4 weeks after the last CpG ODN injection, at the time of euthanasia. The mild to moderate and transient profile of CpG ODN-induced responses may be essential for the reported therapeutic benefits.17,110 Moreover, we confirmed that subcutaneous administration of the Class B CpG ODN was effective in eliciting beneficial immune response patterns in aged populations, whose immune systems may have been compromised.

Future studies will be aimed at determining the interplay between signalling pathways and cell types activated during an acute CpG ODN administration phase to further decipher the mechanism responsible for CpG ODN’s favourable immunomodulatory capabilities. Squirrel monkeys provide a necessary environment to generate mechanistic data that are more applicable for future human translation. The present study represents the first in vivo evidence that stimulation of innate immunity with TLR9 agonist, CpG ODN, leads to behavioural improvements and a reduction of amyloid-related pathology, predominantly CAA, in the absence of microhaemorrhages and encephalitis in elderly squirrel monkeys. Overall, the current research together with our earlier extensive preclinical evidence validates the beneficial therapeutic outcomes and safety of this innovative approach, enhancing the likelihood of CpG ODN’s therapeutic efficacy in clinical trials that are now being initiated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Virginia Moore, Bethany R. Brock, and Casey S. Austin from KCCMR, UT MD Anderson Cancer Center for maintaining the SQM colony and providing in vivo samples to the study. We thank Dr Stephen D. Ginsberg from Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research for his help with SQM brain dissection. We also thank Dr Pankaj D. Mehta for his help with plasma Aβ levels analyses. We thank the following students for their assistance with brain histology: Thomas Genovese, Sohail Karimi, Alexandra Padova, Jozef Conka, Andreia Andrade, and Eliana Shasken. We also thank Mark Alu and Branka Dabovic from the Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory for their assistance.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants NS102845 (H.S.), NS079676 (H.S.), OD010938-40 (L.E.W.) and AG066512 (T.W.), as well as Alzheimer’s Association grant AARG-16–440596 (H.S.), and Cattleman for Cancer Research grant (P.N.N.). The Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory and the Precision Immunology Laboratory are both partially supported by NYU Cancer Institute Center support grant (P30CA016087) at NYU Langone’s Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

- ARIA

amyloid-related imaging abnormalities

- CAA

cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

References

- 1. Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andreasson KI, Bachstetter Alzheimer’s disease, Colonna M, et al. Targeting innate immunity for neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system. J Neurochem. 2016;138(5):653–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee DC, Rizer J, Hunt JB, Selenica ML, Gordon MN, Morgan D.. Review: Experimental manipulations of microglia in mouse models of Alzheimer's pathology: Activation reduces amyloid but hastens tau pathology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39(1):69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schwabe T, Srinivasan K, Rhinn H.. Shifting paradigms: The central role of microglia in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;143:104962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dourlen P, Kilinc D, Malmanche N, Chapuis J, Lambert JC.. The new genetic landscape of Alzheimer's disease: From amyloid cascade to genetically driven synaptic failure hypothesis? Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138(2):221–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M.. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(2):459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McQuade A, Blurton-Jones M.. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease: Exploring how genetics and phenotype influence risk. J Mol Biol. 2019;431(9):1805–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anwar S, Rivest S.. Alzheimer's disease: Microglia targets and their modulation to promote amyloid phagocytosis and mitigate neuroinflammation. Expert Opin Therap Targets. 2020;24(4):331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dionisio-Santos DA, Olschowka JA, O’Banion MK.. Exploiting microglial and peripheral immune cell crosstalk to treat Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflamm. 2019;16(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guillot-Sestier MV, Town T.. Let's make microglia great again in neurodegenerative disorders. J Neural Transm. 2018;125(5):751–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rawji KS, Mishra MK, Michaels NJ, Rivest S, Stys PK, Yong VW.. Immunosenescence of microglia and macrophages: Impact on the ageing central nervous system. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 3):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garaschuk O, Verkhratsky A.. Physiology of microglia. In: Garaschuk O, Verkhratsky A, eds. Microglia: Methods and protocols. New York, NY: Springer; 2019:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hanke ML, Kielian T.. Toll-like receptors in health and disease in the brain: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci. 2011;121(9):367–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doi Y, Mizuno T, Maki Y, et al. Microglia activated with the toll-like receptor 9 ligand CpG attenuate oligomeric amyloid {beta} neurotoxicity in in vitro and in vivo models of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(5):2121–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Michaud JP, Halle M, Lampron A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 stimulation with the detoxified ligand monophosphoryl lipid A improves Alzheimer's disease-related pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(5):1941–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Richard KL, Filali M, Prefontaine P, Rivest S.. Toll-like receptor 2 acts as a natural innate immune receptor to clear amyloid beta 1-42 and delay the cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28(22):5784–5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Selles MC, Fortuna JTS, Santos LE.. Immunomodulation via Toll-like Receptor 9: An Adjunct Therapy Strategy against Alzheimer's Disease? J Neurosci. 2017;37(19):4864–4867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Su F, Bai F, Zhou H, Zhang Z.. Reprint of: Microglial toll-like receptors and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2016;55:166–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Campbell JD, Cho Y, Foster ML, et al. CpG-containing immunostimulatory DNA sequences elicit TNF-alpha-dependent toxicity in rodents but not in humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(9):2564–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heikenwalder M, Polymenidou M, Junt T, et al. Lymphoid follicle destruction and immunosuppression after repeated CpG oligodeoxynucleotide administration. Nat Med. 2004;10(2):187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]