Abstract

Purpose

Over 1 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been already administered across the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union at the time of writing. Furthermore, 1.82 million booster doses have been administered in the US since 13th August, and similar booster programmes are currently planned or under consideration in the UK and the EU beginning in the autumn of 2021. Early reports showed an association between vaccine administration and the development of ipsilateral axillary and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, which could interfere with the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of breast cancer patients. In this paper, we review the available evidence on vaccine-related lymphadenopathy, and we discuss the clinical implications of the same on breast cancer diagnosis and management.

Methods

A literature search was performed – PubMed, Ovid Medline, Scopus, CINHAL, Springer Nature, ScienceDirect, Academic Search Premier and the Directory of Open Access Journals were searched for articles reporting on regional palpable or image-detected lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination.

Separately, we compiled a series of case studies from the University Hospitals of Derby and Burton, United Kingdom and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, United States of America, to illustrate the impact that regional lymphadenopathy post-COVID-19 vaccination can have on the diagnosis and management of patients being seen in diagnostic and therapeutic breast clinics.

Results

From the literature search, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 2057 patients, 737 with lymphadenopathy). The incidence of lymphadenopathy ranged between 14.5% and 53% and persisted for >6 weeks in 29% of patients.

Conclusions

Clinicians managing breast cancer patients should be aware that the COVID-19 vaccination may result in regional lymphadenopathy in a significant number of patients, which can result in unnecessary investigations, treatment and increased patient anxiety. An accurate COVID-19 vaccination history should be collected from all patients where regional lymphadenopathy is a clinical and/or an imaging finding and then combined with clinical judgement when managing individual cases.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine, Lymphadenopathy, Breast cancer, Cancer diagnosis, Cancer follow-up

1. Background

At the time of writing (14th Sep 2021), almost 1.02 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been administered across the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union [[1], [2], [3]]. Since December 2020 four different vaccines have been approved for emergency use in these countries: the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (now fully approved in the US for individuals aged 16 or older), the Moderna vaccine, the AstraZeneca vaccine (not approved in the US) and the Janssen vaccine. Except for the single-dose Janssen vaccine, the current vaccine schedule involves a second vaccine dose that is administered between 21 days and up to 12 weeks after the initial dose, as there is variation in the vaccine schedule in different countries. On 12th August 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration amended the emergency use authorisations for both the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to allow for the use of an additional dose in moderately to severely immunocompromised people [4] and 1.82 million third doses have already been administered since [2]. The administration of a third ‘booster’ dose of vaccine has also been approved in the UK for those aged over 50 and is currently under consideration in the EU for the autumn of 2021 (possibly using different vaccines with a ‘mix and match’ approach) [[5], [6], [7]]. The results of the first heterologous COVID vaccine study (CombivacS study) enrolled 676 participants in a worldwide Phase 2 multicentre study and reported increased immune responses [8]. Similar results have been reported in three observational studies from Germany [[9], [10], [11]]. There are currently two other Phase II trials being run in the UK and the US [12,13]. This strategy, which offers complementary stimulation of different immune pathways, also appears to produce a more potent immune response against variants of concern such as Beta [11,14] and Delta [15].

During the first quarter of 2021, initial reports of patients developing regional lymphadenopathy (palpable or image-detected) after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine (mostly mRNA vaccines) were published [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]], and more recently, guidance to aid the management of COVID-19 vaccine-related lymphadenopathy in the primary care setting has been published [21].

In this paper, we review the available evidence on both palpable and image-detected regional lymphadenopathy attributed to recent receipt of the COVID-19 vaccination. By the use of case studies, we also discuss the clinical implications on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer.

2. Material and methods

A literature search was performed – PubMed, Ovid Medline, Scopus, CINHAL, Springer Nature, ScienceDirect, Academic Search Premier and the Directory of Open Access Journals were searched for articles published between January 2021 and May 2021 using the following terms: ((COVID-19) OR (Pfizer) OR (AstraZeneca) OR (Moderna) OR (Janssen) AND (vaccine) AND (lymphadenopathy)). The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) guidelines were followed [22]. Only English language articles were reviewed, and their reference lists were cross-referenced until the search strategy was exhausted. Additional searches were carried out using Google Scholar and ResearchGate. The most recent search was performed on 9th May 2021.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included only if the lymphadenopathy was diagnosed in one of the following scenarios: a symptomatic presentation with palpable lymphadenopathy; at breast screening examinations; as an incidental finding during other imaging exams or lymphadenopathy detected during breast cancer staging or follow-up exams. No study was excluded based on the design, given they all reported at least the following data: number of patients, age, location of the lymphadenopathy, modality of detection, vaccine dose details (1st or 2nd), and the time of onset of lymphadenopathy in relation to the vaccine. Given the disproportionate number of publications reporting on lymphadenopathy detected after a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan for cancer staging or surveillance, it was decided to exclude studies reporting on smaller numbers of patients in this scenario (i.e. case reports and case series of <50 patients).

2.2. Data collected

The following information was retrieved from the studies: study design/phase; the number of patients included; the number of patients with adenopathy; mean age and sex of patients; type of vaccine administered and the number of doses; site of the adenopathy and number of nodes identified; modality of presentation (symptomatic or image-detected); method of detection; time from vaccine to symptom onset/node detection; history of COVID-19 infection; degree of clinical suspicion; further diagnostic exams/biopsies; length of follow-up and time to resolution.

Case Studies – Case studies of patients presenting at either of our institutions have been compiled to illustrate the varying clinical scenarios that regional lymphadenopathy secondary to COVID-19 vaccination may impact the clinical care of patients attending breast clinics for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

3. Results

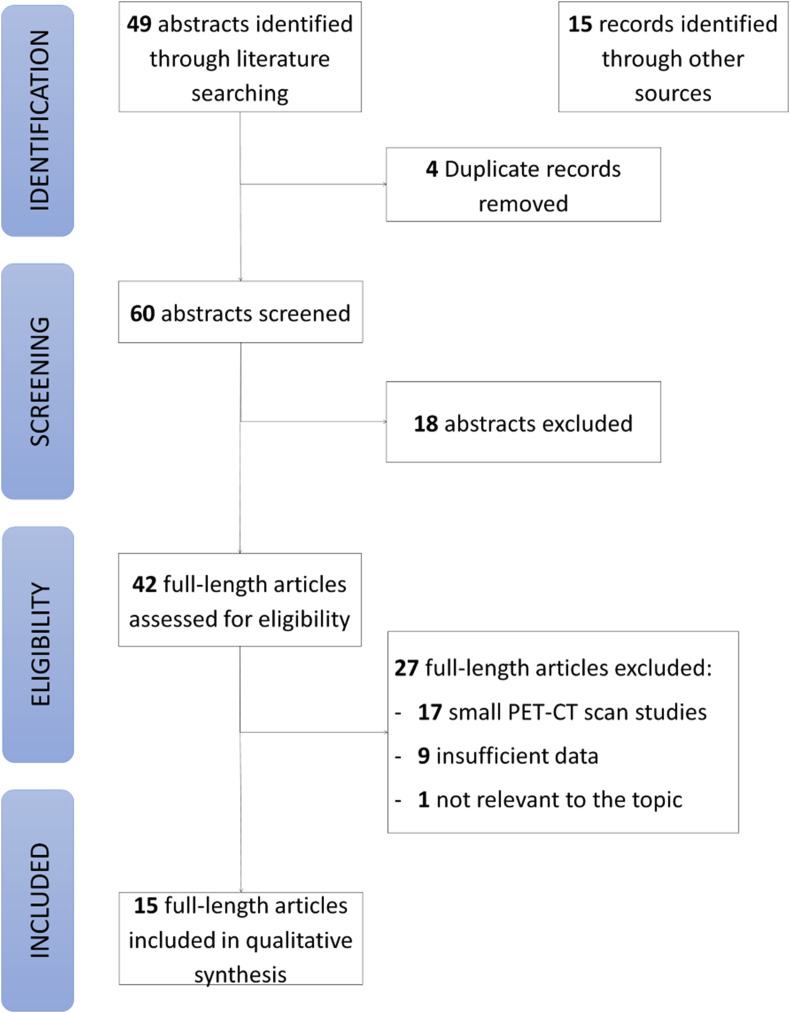

The search strategy identified 49 articles (Fig. 1 ) [22]. After the inclusion of records identified through the additional searches and removal of duplicates, 60 records were screened. The primary reason for exclusion at the screening stage was the lack of relevance to the topic. A total of 42 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 27 were excluded, most commonly because they were small PET-CT scan studies (n = 17) or did not report the minimum amount of data (n = 9). This left 15 studies eligible for inclusion [16,17,[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]] (Fig. 1, Table 1 ). These studies included 2057 patients, with a sample size ranging from 1 to 728, and of those patients, 737 had vaccine-related lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Study demographics and patient presentation details.

| Study | Study design | N patients | N patients with adenopathy | Mean age (range) | N females | N males | Presentation | Method of detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eifer [23] | Retrospective | 426 | 170 | 67 (20–95) | 207 | 219 | Cancer staging/Follow-up | PET-CT |

| Dominguez [24] | Case-report | 1 | 1 | 38 (38) | 0 | 1 | Image-detected | CT |

| Granata [25] | Retrospective | 18 | 18 | 46 (26–63) | 13 | 5 | - Symptomatic (10) - Image-detected (8) |

- Patient (10) - US (8) |

| Hiller [26] | Case-report | 3 | 3 | 45 (42–47) | 3 | 0 | - Symptomatic (2) - Screening (1) |

- Patient (2) - MRI (1) |

| Ahn [27] | Case-report | 3 | 3 | 35 (32–39) | 2 | 1 | - Screening (2) - Image-detected (1) |

- CT (1) - MRI (2) |

| Cohen [28] | Retrospective | 728 | 266 | 69.2 (59–77) | 413 | 315 | Cancer staging/Follow-up | PET-CT |

| Lehman [29] | Case-report | 5 | 5 | 34.6 (42–70) | 4 | 1 | - Screening (3) - Cancer staging/Follow-up (2) |

- MMG (1) - MRI (2) - CT (2) |

| Fernandez [30] | Retrospective | 20 | 20 | 44 (25–60) | 20 | 0 | Symptomatic | Patient |

| Ozutemiz [17] | Retrospective | 5 | 5 | 44 (32–57) | 5 | 0 | - Screening (1) - Cancer staging/Follow-up (2) - Image-detected (2) |

- MRI (2) - CT (1) - US (1) - PET-CT (1) |

| Edmonds [31] | Case-report | 1 | 1 | 48 (48) | 1 | 0 | Screening | MRI |

| Metha [16] | Case-report | 4 | 4 | 50 (42–59) | 4 | 0 | - Screening (3) - Symptomatic (1) |

- US (2) - MMG (1) - Patient (1) |

| Eshet [32] | Retrospective | 169 | 49 | 65 (51–79) | 83 | 86 | Cancer staging/Follow-up | PET-CT |

| Mortazavi [34] | Retrospective | 23 | 23 | 49 (28–70) | 23 | 0 | - Symptomatic (3) - Image-detected (10) - Screening (10) |

- Patient (3) - US (13) - MMG (5) - MRI (2) |

| Washington [35] | Case-report | 1 | 1 | 37 (37) | 1 | 0 | Symptomatic | Patient |

| Bernstine [33] | Retrospective | 650 | 168 | 68.9 (20–97) | 351 | 299 | Cancer staging/Follow-up | PET-CT |

| Total | 2057 | 737 | (20–97) | 1130 | 927 | - Cancer staging/Follow-up (657) - Symptomatic (37) - Image-detected (22) - Screening (21) |

- PET-CT (654) - Patient (37) - US (24) - MRI (9) - MMG (7) - CT (6) |

Legends: PET-CT: positron emission tomography and computed tomography; US: ultrasound; MMG: mammography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography.

All of the selected articles were retrospective studies. Most lymphadenopathies (n = 657) were identified during imaging for cancer staging or follow-up, and of those, almost all were identified on a PET-CT scan (n = 654). The remaining cases of lymphadenopathy presented as follows: 37 symptomatic patients with palpable adenopathy; 22 patients with incidental adenopathy identified during imaging performed for other reasons, and 21 patients with adenopathy identified during breast screening exams (Table 1).

All patients in the selected studies received an mRNA vaccine (mostly the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine), and the incidence of post-vaccination lymphadenopathy among the included studies that reported this information ranged between 14.5% (after a single dose) and 53% (Table 2 ). Receipt of a single dose of vaccine, older age (≥64 years) and an immunocompromised status have been associated with lower rates of lymphadenopathy, whereas higher rates of lymphadenopathy have been found in younger (<64 years), immunocompetent and fully vaccinated patients (Table 2). Among the patients with non-palpable lymphadenopathy, the enlarged nodes were mostly identified in the axilla (n = 688; 98.3%), whereas only 2 (0.3%) had supraclavicular fossa (SCF) adenopathy; 10 patients (1.4%) had both axillary and SCF adenopathy. On the contrary, palpable lymphadenopathies were mostly detected in the SCF (n 32; 86.5%), with only 4 patients (10.8%) presenting with axillary adenopathy and 1 patient (2.7%) presenting with both axillary and SCF adenopathy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccine history and lymphadenopathy details.

| Study | Vaccine type | N 1st dose | N 2nd dose | Site of lymphadenopathy (N) | Mean N nodes (range) | Time from vaccine to detection (days) | Incidence of adenopathy | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eifer [23] | Pfizer | 323 | 103 | Axilla (170) | NK | - 11 (1 dose) - 4 (2 doses) |

53% | Incidence 33% in immunocompromised |

| Dominguez [24] | Pfizer | 1 | 0 | Axilla (1) | 1 (1) | 3 | NK | |

| Granata [25] | Pfizer | 18 | 0 | - Axilla (8) - SCF (10) |

3.2 (1–5) | 1.2 | NK | |

| Hiller [26] | Pfizer | 3 | 0 | - Axilla (1) - SCF (1) - Both (1) |

NK | 12.6 | NK | 2 patients re-developed palpable nodes after 2nd dose |

| Ahn [27] | NK | 2 | 1 | Axilla (3) | NK | 9.3 | NK | |

| Cohen [28] | Pfizer | 346 | 328 | - Axilla (255) - SCF (2) - Both (9) |

NK | - 10 (1 dose) - 12 (2 doses) |

- 43.2% (overall) - 33.8% (1 dose) - 52.1% (2 doses) |

Includes 49 patients with equivocal adenopathy |

| Lehman [29] | Moderna | 3 | 2 | Axilla (5) | NK | 9.6 | NK | |

| Fernandez [30] | - Pfizer (19) - Moderna (1) |

6 | 14 | SCF (20) | NK | 3.8 | NK | |

| Ozutemiz [17] | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | - Axilla (4) - Both (1) |

NK | 8 | NK | |

| Edmonds [31] | NK | 1 | 0 | Axilla (1) | NK | 13 | NK | |

| Metha [16] | - Pfizer (3) - Moderna (1) |

3 | 1 | Axilla (4) | NK | 8.75 | NK | |

| Eshet [32] | Pfizer | 0 | 169 | Axilla (49) | NK | 87 | 29% | |

| Mortazavi [34] | - Pfizer (12) - Moderna (5) - NK (6) |

23 | 0 | Axilla (23) | 1.8 (1–5) | 9.5 | NK | |

| Washington [35] | Moderna | 1 | 0 | SCF (1) | NK | 5 | NK | |

| Bernstine [33] | Pfizer | 394 | 256 | Axilla (168) | - 3.2 (1–10) - 3.7 (1–12) |

- 12.3 (1 dose) - 7.5 (2 doses) |

- 14.5% (1 dose) - 43.3% (2 doses) |

- incidence in 64+ (22.1%) - incidence in <64 (37.5%) |

| Total | - Pfizer (1980) - Moderna (13) - NK (10) |

1126 | 877 | - Axilla (692) - SCF (34) - Both (11) |

Legends: NK: not known; SCF: supraclavicular fossa.

On balance, the degree of suspicion of such lymphadenopathies was considered to be low, with only 10 biopsies performed (1.3%) and little need for further workup imaging studies (Table 3 ). For palpable adenopathy, the average time to clinical resolution (when reported) was approximately 7–8 days. However, in 9 patients (25%), palpable nodes persisted for >21 days. Evidence from the PET-CT scan studies suggested that the lymphadenopathy can persist for longer than 21 days (and even beyond 6 weeks) in 29% of cases.

Table 3.

Clinical details.

| Study | Degree of suspicion | Node biopsy | Further imaging | Clinical resolution (days) | Imaging resolution (days) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eifer [23] | NK | 1 | N/A | NK | NK | |

| Dominguez [24] | Low | No | MMG, US | NK | NK | |

| Granata [25] | - Low (12) - Intermediate (6) |

No | US (10) | 7.1 | 7.1 | US performed in symptomatic patients |

| Hiller [26] | Low | No | US | 26.5 | NK | |

| Ahn [27] | Low | No | US | NK | NK | |

| Cohen [28] | - Low (217) - Intermediate (49) |

No | NK | NK | NK | 29% still present 21 days after 2nd dose |

| Lehman [29] | - Low (4) - Intermediate (1) |

1 | - US (1) - CT (2) |

NK | NK | |

| Fernandez [30] | - Low (15) - Intermediate (5) |

5 | - US (5) - MMG (1) |

8.7 (13 patients) | NK | Adenopathy still persistent in 7 patients after average 21 days (range 7–32) |

| Ozutemiz [17] | High | 2 | - PET-CT (1) - US (1) |

NK | NK | |

| Edmonds [31] | Intermediate | No | No | NK | NK | |

| Metha [16] | Intermediate | No | MMG, US | NK | NK | |

| Eshet [32] | Low | No | No | NK | NK | |

| Mortazavi [34] | - Low (22) - High (1) |

1 | US | NK | NK | |

| Washington [35] | Low | No | MMG,US | NK | NK | |

| Bernstine [33] | Low | No | N/A | NK | NK |

Legends: NK: not known; N/A: not applicable; US: ultrasound; MMG: mammography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography; PET-CT: positron emission tomography and computed tomography.

4. Discussion

Adverse events reported in the randomised controlled trials of the COVID-19 vaccines include data on lymphadenopathy [[36], [37], [38], [39]]. For the Moderna vaccine, the reported rate of ipsilateral axillary lymphadenopathy or tenderness (symptoms were not reported separately) was ∼11.6% and 16% after the first and second dose, respectively. A small number of cases of neck lymphadenopathy were also reported [36]. For the other vaccines, the incidence of ipsilateral axillary lymphadenopathy was reported to be lower: <1% for the Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines and 0.1% for the Janssen vaccine [[37], [38], [39]]. However, it is worth noting that in these trials, unlike the Moderna one, lymphadenopathy was only reported as an unsolicited adverse event, and hence, the true incidence rate is likely to be higher.

As COVID-19 vaccines are administered intramuscularly to the deltoid muscle, vaccination-associated adenopathy typically occurs in the axilla and supraclavicular region. Recognition of this association is crucial in patients with cancer, where it can lead to underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis, undertreatment or overtreatment and increased patient anxiety. This is especially relevant not only for breast cancer patients but also for patients with head and neck cancers, lymphoma, and melanoma of the back and upper extremities as these malignancies have a predilection for metastasising to these lymph node stations. As shown by the data from Israel, the true incidence of image-detected ipsilateral lymphadenopathy after an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine appears to be at least 2–3 times higher than previously reported in the Moderna trial [23,28,33] and, during the current mass vaccination campaign, patients should be routinely asked about their vaccination history when they are assessed for breast conditions. In the following paragraphs, we present some considerations regarding the potential impact of vaccine-related lymphadenopathy on the management of breast patients in different settings: from breast cancer screening to post-treatment cancer surveillance.

4.1. Breast cancer screening

The first cases of subclinical unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccinations were identified by breast imagers in women undergoing breast screening exams such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), mammography, and ultrasound [16,31]. The Society of Breast Imaging, as well as other groups in the US, responded by publishing different management recommendations [29,40,41]. Although there was a general consensus that COVID-19 vaccination should not be postponed due to the need for imaging in patients undergoing breast cancer screening or surveillance, the recommendations regarding the timing of imaging and management of the lymphadenopathy varied. According to the Society of Breast Imaging, patients with unilateral axillary adenopathy identified during screening exams should be recalled for further assessment of the ipsilateral breast and documentation of relevant medical history, including prior COVID-19 vaccination. Imaging follow-up 4–12 weeks after the second vaccine dose is recommended for patients with isolated axillary adenopathy [40]. They also recommend that routine screening exams should be postponed until 6 weeks after completion of the vaccination course [40]. According to the management guidance published in March 2021 by Lehman et al., in patients with isolated lymphadenopathy and a recent history of COVID-19 vaccination (up to 6 weeks prior), it would be appropriate to adopt an expectant management strategy without default imaging follow-up [29]. However, patients with remote vaccination history, bilateral lymphadenopathy, and palpable lymphadenopathy were excluded from this recommendation [29]. An expectant management strategy has also been advocated by a multidisciplinary panel of cancer experts for all axillary and supraclavicular adenopathies (both palpable and image-detected) where COVID-19 vaccination is felt to be the more likely cause. For those cases where there is a higher risk of metastatic adenopathy, short term follow-up imaging (at least 6 weeks) is recommended [41]. A longer delay of breast screening and all non-urgent imaging exams (at least 6 weeks from second vaccine dose) is also advocated by the panel [41].

Contrary to the US, where the general advice has been to perform breast screening exams either before receiving the COVID-19 vaccine or 6–10 weeks after the second dose, no specific recommendations regarding the timing of breast screening in relation to COVID-19 vaccination have been issued in the UK or in Europe [42]. In England, advice regarding the scheduling of mammograms has not altered. There is currently no requirement for women to wait for a predefined time period following a COVID-19 vaccination before attending a screening appointment.

A recently published retrospective case series analysed the mammograms of 750 patients with a history of administration of at least 1 dose of a COVID-19 vaccine within the previous 90 days and identified 23 cases of axillary adenopathy (3%), which is higher than reported rates of axillary adenopathy in otherwise normal mammography (0.02–0.04%). The incidence of adenopathy was found to be higher in the first 2 weeks following the vaccination, with no cases identified beyond 28 days from vaccine administration [43].

The finding of isolated axillary lymphadenopathy during a screening mammogram requires a recall for ultrasound assessment of lymph node morphology. In patients with suspicious or frankly malignant appearing nodes, a needle biopsy would be performed irrespective of their vaccination history, whereas patients with fatty or normal-appearing lymph nodes (i.e. BIRADS 1) would be discharged. It is in patients with probably benign/reactive nodes with regular cortical thickening that COVID-19 vaccination history becomes relevant, although this information should be used in the context of an overall patient's risk assessment. Patients who received a recent COVID-19 vaccination (<6 weeks) in the ipsilateral arm and who are at low risk of malignancy (i.e. fatty mammogram and no relevant family history) can be discharged and instructed to return in case they develop a palpable abnormality, whereas in patients with a significant family history of breast cancer and/or dense mammogram a 3–6 months follow-up would be advisable, based on clinical judgement.

In patients presenting with lymphadenopathy associated with an ipsilateral breast abnormality and recent COVID-19 vaccine history, the management will vary according to the appearance of the breast lesion. A lymph node biopsy will be performed only in cases where the breast abnormality looks suspicious or frankly malignant (i.e. BIRADS 4–5), whereas in patients with benign-appearing breast lesions (i.e. BIRADS 2–3) only a breast biopsy will be performed in the first instance (Fig. 2 ).

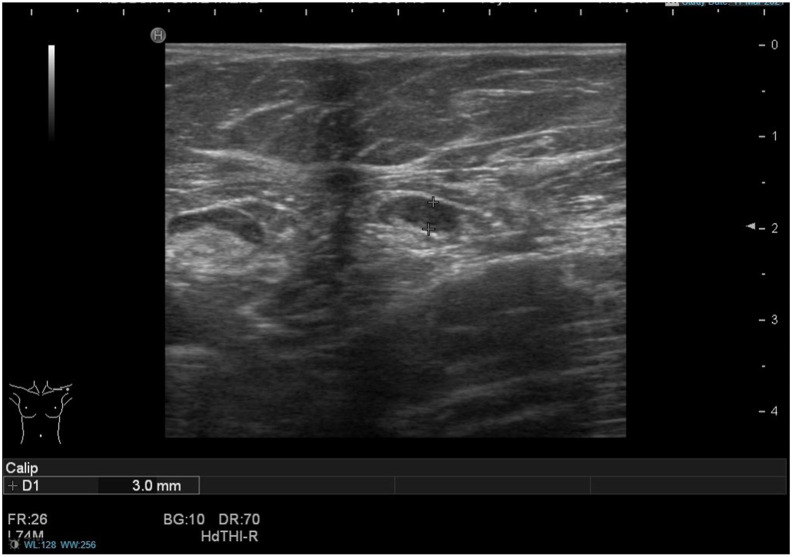

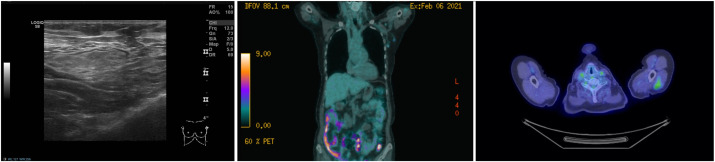

Fig. 2.

(Case 1): A 70-year-old woman was recalled following a screening mammogram for an ill-defined malignant-appearing mass in the left breast. The mass measured 17 mm on digital breast tomosynthesis and 16 mm on ultrasound scan. On ultrasound assessment of the axilla, there was an enlarged lymph node with a 3 mm cortex of indeterminate nature (U3). The patient reported having received the 1st dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in the left arm four weeks prior to the ultrasound date. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy of the breast mass showed a grade II invasive mixed ductal and lobular cancer, while ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lymph node demonstrated small and intermediate size lymphocytes with no obvious metastatic carcinoma cells (C2). The benign FNA result was accepted, and the patient underwent left-sided breast-conserving surgery and a left-sided sentinel node biopsy that was negative for metastasis.

4.2. Symptomatic patients

Axillary metastatic carcinoma without detection of a primary breast lesion (occult primary) is rare, occurring in only 0.3–1% of all breast cancer patients [44]. Therefore, in patients presenting to University Hospitals of Derby and Burton (UHDB) with palpable unilateral axillary/supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, normal breast imaging and a history of recent COVID-19 vaccination in the ipsilateral arm, short-term follow-up (4–5 weeks) is generally preferred to a potentially unnecessary and costly lymph node biopsy (Fig. 3 ). Although minimal data has been published on patients with palpable lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination, the available literature supports this approach. Of the 20 patients with palpable SCF adenopathy described by Fernandez et al., 13 (65%) had complete symptom resolution after an average of 8.7 days (range 5–15 days). Although palpable adenopathy was still persistent in 7 patients (35%) at the end of the reported follow-up (average 21 days, range 7–32 days), all showed signs of clinical improvement [30]. Other studies reported an average symptom duration between 7.1 and 26.5 days [25,26]. At the time of the follow-up appointment, a lymph node biopsy should be considered for patients with no signs of clinical improvement.

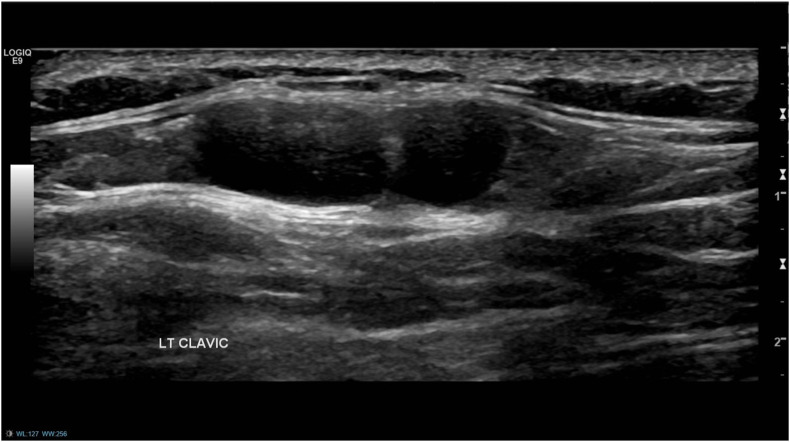

Fig. 3.

(Case 2): A 38-year-old woman, with no personal or family history of breast cancer, presented with a 4-week history of a palpable lump inferior to the left clavicle, which was first noticed approximately one week after receiving the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in the left arm. Ultrasound of the left axilla and supraclavicular fossa (SCF) revealed normal-appearing axillary lymph nodes and a couple of lymph nodes up to 8 mm in size in the area of interest, with appearances favouring benign reactive nodes. A bilateral mammogram showed no abnormalities. As the patient was due to have her 2nd vaccine dose in 5 weeks' time, she was advised to return for a 10-week follow-up ultrasound scan and clinical examination to ensure resolution. The patient reported that in the following weeks, the adenopathy progressively improved. Two days after receiving the 2nd vaccine dose, she again developed palpable SCF adenopathy that had resolved completely by the time of her follow-up appointment.

In patients with a personal or family history of breast cancer, or if another malignancy (i.e. lymphoma) is suspected, a lymph node biopsy may still be considered, depending on the degree of clinical concern (Fig. 4 ). In patients where a suspicious abnormality is identified in the ipsilateral breast, a lymph node biopsy should be routinely performed.

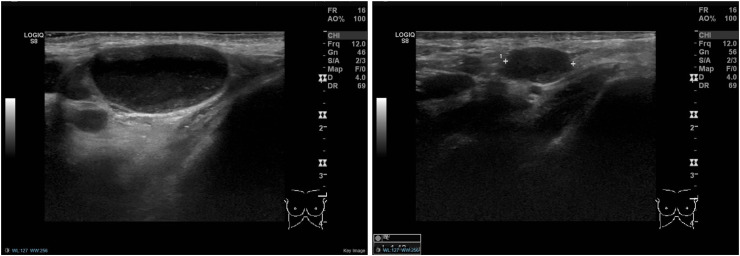

Fig. 4.

(Case 3): A 76-year-old woman presented with a palpable lump in her left axilla and no breast symptoms. She received the 1st dose of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in her left arm 8 weeks prior. Ultrasound of the left axilla demonstrated a large abnormal appearing lymph node, suspicious of malignancy (left). Mammography showed no breast abnormalities. Lymph node core biopsy demonstrated non-specific reactive changes. A 6-week follow-up ultrasound scan demonstrated no significant change in size and appearance of the node. However, the patient had the 2nd vaccine dose administered in the left arm the previous week, and therefore, biopsy was not repeated, and a further ultrasound scan was arranged in 6 weeks. This showed marked improvement, both clinically and radiologically, and the patient was reassured and discharged (right).

4.3. Patients with breast cancer diagnosis: staging, response to therapy and surgical planning

Incidental detection of enlarged lymph nodes in breast cancer patients undergoing staging or restaging scans could not only confound the accurate assessment of disease extent and/or treatment response but may also increase patient anxiety and lead to additional and unnecessary interventions. At UHDB, the detection of ipsilateral enlarged regional lymph nodes in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer during staging exams such as breast MRI or CT scan would mandate a targeted ultrasound and lymph node biopsy with fine-needle aspiration (FNA), unless the adenopathy could be confidently attributed to the COVID-19 vaccine (i.e. uptake at the site of injection in the deltoid muscle seen on PET-CT scan) (Fig. 5 ). For patients with benign-appearing lymph nodes (low suspicion), a benign FNA result is accepted, whereas a core biopsy would be performed in all patients with highly suspicious nodes. COVID-19 vaccination history becomes relevant for those patients with an intermediate grade of suspicion for malignancy, as we would tend to accept a benign FNA result in those patients with recent (previous 6 weeks) vaccination in the ipsilateral arm, whereas a core biopsy would be requested for those with no recent history of vaccination. This approach is supported by the published literature, as vaccine-related lymphadenopathies were generally associated with a low or intermediate degree of suspicion, and only a small minority of cases (6 out of 737, 0.81%) were described as highly suspicious (Table 3).

Fig. 5.

(Case 4): A 73-year-old female who was referred to the symptomatic breast clinic with a one-month history of a left-sided breast mass. Clinical examination revealed a 25 mm suspicious breast mass and no clinically palpable axillary or supraclavicular lymph nodes. On breast imaging, the mass was also suspicious of malignancy, measuring 26 mm on mammography and 24 mm on ultrasound scan. Axillary ultrasound at that time demonstrated no lymphadenopathy (left). The breast biopsy showed evidence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Due to the unusual histology, a whole-body PET-CT scan was performed to rule out primary SCC from other sites. This did not show evidence of another primary malignancy, however, clustered left axillary and subpectoral nodes, measuring <1 cm, were identified. Those were judged as presumably inflammatory in nature, although malignant infiltration could not be excluded (middle). There was also uptake noticed within the left deltoid muscle (right). The patient had the 1st dose of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in the left arm one day prior to the PET-CT scan. The lymphadenopathy was considered likely to be vaccine-related and the patient underwent a left mastectomy and left sentinel node biopsy, which was negative for lymph node metastasis.

Contralateral axillary metastasis is a rare occurrence in breast cancer (reported incidence between 1.6% and 6%) [45], and in those patients with a history of recent COVID-19 vaccination in the contralateral arm and image-detected lymphadenopathy, omission of a lymph node biopsy would be reasonable, especially if there is no adenopathy on the side of the patient's prior/current breast cancer. The biopsy of highly suspicious lymph nodes should not be omitted in those circumstances.

It is of paramount importance that breast cancer patients who are waiting to receive one or more of the vaccine doses, including any future booster doses, are instructed to do so in the contralateral arm to their breast cancer. Administration of the vaccine to the ipsilateral arm could cause confusion when assessing the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy as the appearance of enlarged axillary and/or supraclavicular nodes could mimic cancer progression (Fig. 6 ).

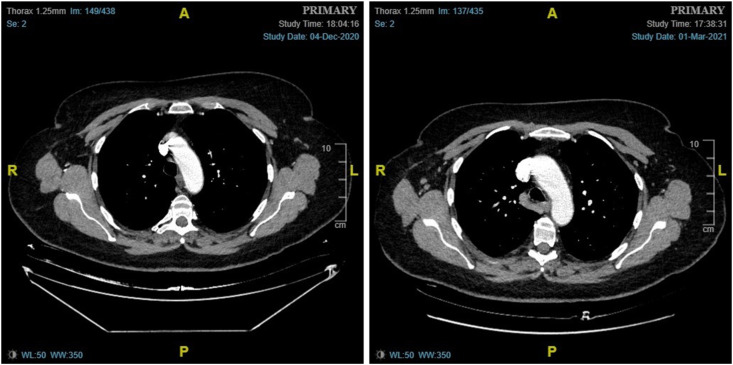

Fig. 6.

(Case 5): A 71-year-old woman, with a history of a right-sided breast cancer 9 years ago, attended the symptomatic breast clinic with a new lump in her left breast. Mammogram and breast ultrasound identified a 29 mm malignant appearing lesion in the lower inner quadrant of the left breast. Ultrasound of the left axilla was normal. A core biopsy of the left breast mass showed grade 2 invasive ductal cancer, which was ER positive, and HER2 positive. Breast MRI confirmed the presence of a 31 mm spiculated mass in the left breast. Staging CT scans of chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of metastatic disease, with only small volume para-aortic lymphadenopathy seen, and no pathological lymphadenopathy in the axilla or SCF/ICF bilaterally (left). The patient was started on neoadjuvant chemotherapy to downsize the cancer and facilitate breast conserving surgery. A repeat CT scan was performed after 3 months of neoadjuvant systemic treatment, which identified the interval emergence of prominent right-sided axillary nodes, of uncertain clinical significance (right). The patient had the first dose of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine administered into the right arm 4 weeks prior. On imaging review, the left breast cancer showed signs of interval response to treatment compared to the previous CT scan. In view of this, and due to the patient's vaccine history, it was felt that the right axillary adenopathy was unlikely to represent metastatic disease, and a 6-month follow-up with an ultrasound of the right axilla was advised. The patient completed neoadjuvant chemotherapy and underwent left breast-conserving surgery and sentinel node biopsy that showed complete pathological response in the breast and no evidence of lymph node metastasis or fibrosis.

Vaccine-related lymphadenopathy could also negatively affect the quality of breast cancer care by resulting in more extensive axillary surgery. Similar considerations have been recently published by Ko et al., who advised vaccine administration at least one week prior to surgery or one to two weeks after (to avoid confusion in the causality attribution of symptoms such as fever) and in the arm opposite to the affected breast [46]. It is worth noting, however, that the maximum levels of protection following COVID-19 vaccine administration are achieved in 3–4 weeks [47], and therefore, it would be preferable to perform the surgery after this time interval, especially in elderly patients or in those who have been treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

4.4. Breast cancer surveillance and metastatic breast cancer

Interpretation of the significance of lymphadenopathy after COVID-19 vaccination in breast cancer (or other malignancies that tend to involve axillary and supraclavicular lymph nodes) can be challenging. Of the 332 vaccinated patients with ipsilateral hypermetabolic axillary and/or SCF lymph nodes detected during PET-CT scan in the study by Cohen et al., the lymphadenopathy was described as equivocal in 49 cases (14.8%), and of those, 20 (40.8%) were women with ipsilateral breast cancer [28]. Among the 728 vaccinated patients who underwent PET-CT scans in the aforementioned study, 113 (15.5%) were breast cancer patients [28]. A recently published study from the US (although with limited sample size and follow-up) also found that women might be more likely to develop reactive nodes following COVID-19 vaccination, with 7 out of 9 (78%) patients with lymphadenopathy (in a cohort of 68 vaccinated patients undergoing PET-CT scan for oncological indications) being female [48].

The fact that equivocal lymphadenopathy was detected in 17.7% of breast cancer patients highlights the importance of administering the vaccine into the contralateral arm. Awareness of vaccine-related lymphadenopathy should be raised among all the members of breast multidisciplinary teams. Oncologists, in particular, play an important role in the coordination of both imaging and COVID-19 vaccination in patients undergoing systemic therapies and should recommend vaccine administration in the arm contralateral to their breast cancer.

If the imaging assessment is required in an urgent or timely manner (i.e. for staging or treatment initiation), then the examination should not be delayed on the basis of the potential confounding effect of the COVID-19 vaccination. If the indication for imaging is non-urgent (i.e. routine surveillance or monitoring of metastatic disease when disease progression is not suspected except for the lymphadenopathy), then delaying the exam could be considered. A delay of at least 2 weeks after completion of the vaccination course before performing a PET-CT scan (but preferably 4–6 weeks if the exam is non-urgent) has been proposed to avoid potential confounding findings [49]. However, the usefulness of this approach could be questioned when considering the recent findings of an Israeli study that included 169 patients undergoing a PET-CT scan 7–10 weeks after receiving the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine; persistent unilateral lymphadenopathy was observed in 29% of patients [32].

The appropriate management strategy for these patients should be determined on a case-by-case basis taking into account characteristics of the cancer, COVID-19 vaccination history and the degree of clinical suspicion. If the lymphadenopathy is felt unlikely to be malignant, then clinical judgement could be used to attribute the findings to the vaccination, and no further follow-up would be needed. In the case of indeterminate or confounding lymphadenopathy (i.e. a vaccine administered on the same side as the breast cancer or known prior axillary metastases), then management would be determined by the relevance of the clinical findings. If clinically irrelevant (i.e. will not change disease stage), then no further imaging is recommended, and attention should be given on follow-up. If clinically relevant, then a lymph node biopsy should be considered (Fig. 7, Fig. 8 ).

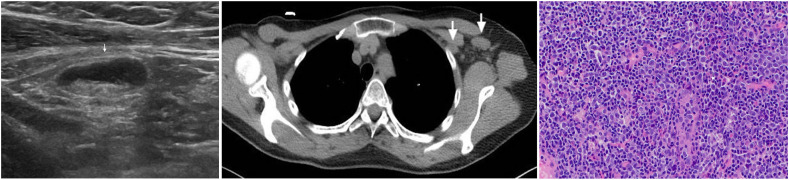

Fig. 7.

(Case 6): A 58-year-old woman with a history of a stage III right-sided breast cancer receiving extended adjuvant endocrine treatment with exemestane was found to have new palpable axillary lymphadenopathy during a follow-up visit. Three weeks prior, she received the 2nd dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine to her left arm. Ultrasound of left axilla (left) and a chest CT scan (middle) demonstrated new multiple abnormal-appearing left axillary and subpectoral lymph nodes, the largest measuring 2 cm. A core biopsy of the largest lymph node revealed reactive changes with mild follicular and paracortical lymphoid hyperplasia, including an increased number of polytopic B-immunoblasts (right). Cytokeratin stain was negative for metastatic disease.

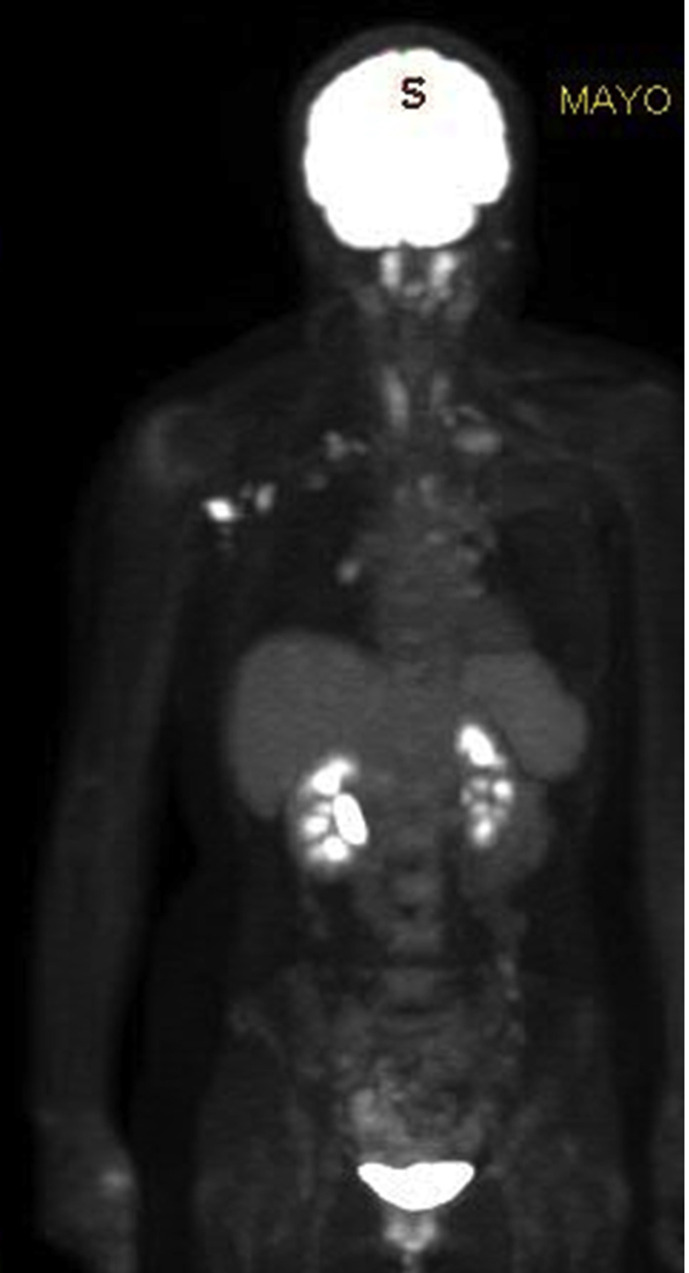

Fig. 8.

(Case 7): A 41-year-old female with a prior history of locally advanced left breast cancer at the age of 33, presented to the Mayo Clinic Neurology service with the slow onset numbness of the 4th and 5th digits of her left hand, progressing to weakness in the left hand and forearm. In 2003, she presented with a T2, N3 breast cancer (ER+/HER2-) treated with bilateral mastectomies and left axillary node dissection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormonal therapy. She received sequential doses of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to her right arm, with the last dose two weeks prior to her presentation to the Mayo Clinic. A PET-CT scan identified hypermetabolic right axillary, retropectoral and retro-clavicular lymph nodes, most consistent with nodal metastasis, as well as local and linear areas of FDG uptake along the left brachial plexus at the level of C7-T1 paravertebral region also extending to intervertebral neural foramen and probably to the spinal canal. A non-diagnostic FNA of the pathological right axillary lymph node was followed by a core biopsy that was negative for malignancy (lymphocytes consistent with sampled lymph node). Neurosurgical exploration of left brachial plexus demonstrated nodular enlargement and swelling of C8 and two fascicular biopsies demonstrated perineural space involved by metastatic carcinoma, consistent with a breast primary.

5. Conclusions

The real-world experience from the mass- COVID-19 vaccination campaign shows that a higher proportion of vaccinated people will develop regional lymphadenopathy than what was originally reported in vaccine randomised clinical trials, and this could last beyond 6 weeks. This has important implications for the diagnosis and/or management of patients with a known or suspected breast cancer diagnosis. Accurate information regarding COVID-19 vaccination history should be collected from all patients and combined with clinical judgement when managing individual cases. Clinicians should provide patients with clear information and advice regarding the potential onset of regional lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 (particularly vaccine administration to the arm opposite to the affected breast) and its implications for breast cancer care in order to avoid misconceptions that may lead to vaccine hesitancy [50].

Ethics approval

The case studies were prepared in accordance with the policies and ethical standards of the University Hospitals of Derby and Burton and the Mayo Clinic.

Consent to publish

Patients described in the case studies consented to the publication of their data and photographs.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conceptualisation and writing. Literature search and data analysis were performed by EG. Material for the case studies was provided by AH, CO'S, JY and AZH. JFR and MPG provided overall supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.UK Government Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/vaccinations Available at:

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID Data Tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations Available at:

- 3.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker. https://vaccinetracker.ecdc.europa.eu/public/extensions/COVID-19/vaccine-tracker.html#uptake-tab Available at:

- 4.Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes additional vaccine dose for certain immunocompromised individuals. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-vaccine-dose-certain-immunocompromised Food and Drug Administration. Available at:

- 5.Mahase E. Covid-19: booster vaccine to be rolled out in autumn as UK secures 60m more Pfizer doses. BMJ. 2021 Apr 29;373:n1116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MHRA statement on booster doses of Pfizer and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/mhra-statement-on-booster-doses-of-pfizer-and-astrazeneca-covid-19-vaccines Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Available at:

- 7.ECDC and EMA highlight considerations for additional and booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ecdc-ema-highlight-considerations-additional-booster-doses-covid-19-vaccines European Medicines Agency. Available at:

- 8.Borobia A.M., Carcas A.J., Pérez-Olmeda M., Castaño L., Bertran M.J., García-Pérez J., et al. CombiVacS Study Group Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of BNT162b2 booster in ChAdOx1-S-primed participants (CombiVacS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2021 Jul 10;398(10295):121–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01420-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillus D., Schwarz T., Tober-Lau P., Vanshylla K., Hastor H., Thibeault C., Jentzsch S., Helbig E.T., Lippert L.J., Tscheak P., Schmidt M.L., Riege J., Solarek A., von Kalle C., Dang-Heine C., Gruell H., Kopankiewicz P., Suttorp N., Drosten C., Bias H., Seybold J., EICOV/COVIM Study Group. Klein F., Kurth F., Corman V.M., Sander L.E. Safety, reactogenicity, and immunogenicity of homologous and heterologous prime-boost immunisation with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and BNT162b2: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Aug 12 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00357-X. S2213-2600(21)00357-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt T., Klemis V., Schub D., Mihm J., Hielscher F., Marx S., et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/mRNA vaccination. Nat Med. 2021 Jul 26;27(9):1530–1535. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01464-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barros-Martins J., Hammerschmidt S.I., Cossmann A., Odak I., Stankov M.V., Morillas Ramos G., et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after heterologous and homologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/BNT162b2 vaccination. Nat Med. 2021 Jul 14;27(9):1525–1529. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.COV-BOOST Evaluating COVID-19 vaccine boosters. https://www.covboost.org.uk/home Available at:

- 13.Delayed heterologous SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dosing (boost) after receipt of EUA vaccines. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04889209 Available at:

- 14.Normark J., Vikström L., Gwon Y.D., Persson I.L., Edin A., Björsell T., et al. Heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 9;385(11):1049–1051. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2110716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behrens G.M., Cossmann A., Stankov M.V., Nehlmeier I., Kempf A., Hoffmann M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 delta variant neutralisation after heterologous ChAdOx1-S/BNT162b2 vaccination. Lancet. 2021 Aug 17 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01891-2. S0140-6736(21)01891-01892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta N., Sales R.M., Babagbemi K., Levy A.D., McGrath A.L., Drotman M., et al. Unilateral axillary Adenopathy in the setting of COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Imaging. 2021 Jan 19;75:12–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Özütemiz C., Krystosek L.A., Church A.L., Chauhan A., Ellermann J.M., Domingo-Musibay E., et al. Lymphadenopathy in COVID-19 vaccine recipients: diagnostic dilemma in oncology patients. Radiology. 2021 Feb 24:210275. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nawwar A.A., Searle J., Singh R., Lyburn I.D. Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination induced lymphadenopathy on [18F]Choline PET/CT-not only an FDG finding. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 Mar 4:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cellina M., Irmici G., Carrafiello G. Unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy after coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 May;216(5):W27. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.25683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell O.R., Dave R., Bekker J., Brennan P.A. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination: an increasing presentation to the two-week wait neck lump clinic? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021 Feb 15 doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2021.02.002. S0266-4356(21)00060-00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garreffa E., York J., Turnbull A., Kendrick D. Regional lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination: considerations for primary care management. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 May 27;71(707):284–285. doi: 10.3399/bjgp21X716117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eifer M., Tau N., Alhoubani Y., Kanana N., Domachevsky L., Shams J., et al. Covid-19 mRNA vaccination: age and immune status and its association with axillary lymph node PET/CT uptake. J Nucl Med. 2021 Apr 23 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262194. jnumed.121.262194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dominguez J.L., Eberhardt S.C., Revels J.W. Unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and imaging findings. Radiol Case Rep. 2021 Jul;16(7):1660–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granata V., Fusco R., Setola S.V., Galdiero R., Picone C., Izzo F., et al. Lymphadenopathy after BNT162b2 covid-19 vaccine: preliminary ultrasound findings. Biology (Basel) 2021 Mar 11;10(3):214. doi: 10.3390/biology10030214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiller N., Goldberg S.N., Cohen-Cymberknoh M., Vainstein V., Simanovsky N. Lymphadenopathy associated with the COVID-19 vaccine. Cureus. 2021 Feb 23;13(2) doi: 10.7759/cureus.13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahn R.W., Mootz A.R., Brewington C.C., Abbara S. Axillary lymphadenopathy after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021 Feb 3;3(1) doi: 10.1148/ryct.2021210008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen D., Krauthammer S.H., Wolf I., Even-Sapir E. Hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy following administration of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine: incidence assessed by [18F]FDG PET-CT and relevance to study interpretation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021 Mar 27:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05314-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehman C.D., D'Alessandro H.A., Mendoza D.P., Succi M.D., Kambadakone A., Lamb L.R. Unilateral lymphadenopathy after COVID-19 vaccination: a practical management plan for radiologists across specialties. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021 Mar 4 doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2021.03.001. S1546-1440(21)00212-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernández-Prada M., Rivero-Calle I., Calvache-González A., Martinón-Torres F. Acute onset supraclavicular lymphadenopathy coinciding with intramuscular mRNA vaccination against COVID-19 may be related to vaccine injection technique, Spain, January and February 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021 Mar;26(10):2100193. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.10.2100193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edmonds C.E., Zuckerman S.P., Conant E.F. Management of unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy detected on breast MRI in the era of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 Feb 5 doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.25604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eshet Y., Tau N., Alhoubani Y., Kanana N., Domachevsky L., Eifer M. Prevalence of increased FDG PET/CT axillary lymph node uptake beyond 6 Weeks after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination. Radiology. 2021 Apr 27:210886. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernstine H., Priss M., Anati T., Turko O., Gorenberg M., Steinmetz A.P., et al. Axillary lymph nodes hypermetabolism after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients undergoing 18F-FDG PET/CT: a cohort study. Clin Nucl Med. 2021 May 1;46(5):396–401. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mortazavi S. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) vaccination associated axillary adenopathy: imaging findings and follow-up recommendations in 23 women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 Feb 24;217(4):857–858. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.25651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Washington T., Bryan R., Clemow C. Adenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination. Radiology. 2021 Feb 24:210236. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Local reactions, systemic reactions, adverse events, and serious adverse events: Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-byproduct/moderna/reactogenicity.html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from:

- 37.Local reactions, systemic reactions, adverse events, and serious adverse events: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-byproduct/pfizer/reactogenicity.html Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at:

- 38.Public Assessment Report for AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulatory-approval-of-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca/information-for-healthcare-professionals-on-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Available at:

- 39.Public Assessment Report for COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/covid-19-vaccine-janssen#product-information-section European Medicines Agency. Available at:

- 40.Grimm L., Destounis S., Dogan B., Nicholson B., Dontchos B., Sonnenblick E., et al. 2021. SBI recommendations for the management of axillary adenopathy in patients with recent COVID-19 vaccination: society of breast imaging patient care and delivery committee.https://www.sbi-online.org/Portals/0/Position%20Statements/2021/SBI-recommendations-for-managing-axillary-adenopathy-post-COVID-vaccination.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker A.S., Perez-Johnston R., Chikarmane S.A., Chen M.M., El Homsi M., Feigin K.N., et al. Multidisciplinary recommendations regarding post-vaccine adenopathy and radiologic imaging: radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology. 2021 Feb 24:210436. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021210436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lane S., Shakir S. Drug Safety Research Unit; 2021. Pharmacovigilance evidence review: the effect of covid-19 vaccines on breast screening.www.dsru.org/pharmacovigilance-evidence-review-the-effect-of-covid-19-vaccines-on-breast-screening Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson K.A., Maimone S., Gococo-Benore D.A., Li Z., Advani P.P., Chumsri S. Incidence of axillary adenopathy in breast imaging after COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Jul 22 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ofri A., Moore K. Occult breast cancer: where are we at? Breast. 2020 Dec;54:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magnoni F., Colleoni M., Mattar D., Corso G., Bagnardi V., Frassoni S., et al. Contralateral axillary lymph node metastases from breast carcinoma: is it time to review TNM cancer staging? Ann Surg Oncol. 2020 Oct;27(11):4488–4499. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko G., Hota S., Cil T.D. COVID-19 vaccination and breast cancer surgery timing. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021 Aug;188(3):825–826. doi: 10.1007/s10549-021-06293-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Robertson C., Stowe J., Tessier E., et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021 May 13;373:n1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adin M.E., Isufi E., Kulon M., Pucar D. Association of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine with ipsilateral axillary lymph node reactivity on imaging. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Aug 1;7(8):1241–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McIntosh L.J., Bankier A.A., Vijayaraghavan G.R., Licho R., Rosen M.P. COVID-19 vaccination-related uptake on FDG PET/CT: an emerging dilemma and suggestions for management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021 Mar 1;217(4):975–983. doi: 10.2214/AJR.21.25728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Villarreal-Garza C., Vaca-Cartagena B.F., Becerril-Gaitan A., Ferrigno A.S., Mesa-Chavez F., Platas A., et al. Attitudes and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Aug 1;7(8):1242–1244. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]