Abstract

Background

The year 2020 was dramatically characterized by SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outbreak. COVID-19-related heart diseases and myocarditis have been reported.

Case summary

A 45-year-old healthy male was admitted to the intensive care unit of our hospital because of cardiogenic shock. A diagnosis of COVID-19 infection and myocarditis was done. We present here several peculiarities about diagnostic workup, myocardial histological findings, choice of treatment, and the patient clinical course at 3 and 8 months of follow-up.

Discussion

COVID-19 myocardial damage and myocarditis are mainly linked to the cytokine storm with mild myocardial inflammatory infiltrate and very unusual platelet microclots in the setting of the microvascular obstructive thrombo-inflammatory syndrome. Counteracting the inflammatory burden with an interleukine-1 inhibitor appeared safe and led to a dramatic and stable improvement of cardiac function.

Keywords: Case report, Cardiogenic shock, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 myocarditis, Anakinra

Learning points

Nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 detection has low diagnostic accuracy in some context. History, clinical findings, and additional diagnostic exams are crucial to obtain a final diagnosis.

COVID-19 myocardial damage and myocarditis are mainly linked to the cytokine storm. In addition, platelet microclots can be observed in small vessels and may contribute to multiorgan dysfunction.

A therapeutic strategy with an IL-1 inhibitor to counteract the disease-related cytokine burden can lead to an important and stable improvement of cardiac function.

Introduction

The year 2020 was dramatically characterized by SARS-CoV-2 pandemic outbreak. COVID-19-related heart diseases and myocarditis have been reported. However, the mechanisms explaining myocardial injury in patients SARS-CoV-2 infection remain to be understood. We present an interesting case of a 45-year-old male admitted to our hospital with cardiogenic shock. Diagnostic and therapeutic workup allowed to highlight peculiarities about the disease, myocardial histological findings, and treatment choices.

Timeline

| Time | Event |

|---|---|

| 10 March | First symptoms: fever, mild dyspnoea, fatigue |

| 14 March | The patient presented to the emergency department because of worsening symptoms. A first computed tomography of the thorax showed mild ground-glass opacities but nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 tested negative |

|

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit of our hospital with the diagnosis of cardio-septic shock. He was pyretic, hypoxic (Sp02 85%), with severe biventricular impairment and metabolic acidosis (pH 7.26; lactate 9 mmol/L). Non-invasive mechanical ventilation and inotropic support with noradrenaline and then adrenaline was started together with empiric antibiotic therapy |

|

Because of worsening hypotension and persistent metabolic acidosis, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was placed |

| 16 March | The patient conditions remained critical but stable. Bronchoscopy was performed to explain the infective aetiology. Bronchoalveolar lavage tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 |

| 20 March | Clinical stabilization, IABP removed. Complete weaning from inotropic support |

| 21 March | The patient was transferred to the Cardiology department in decent clinical condition and haemodynamically stable. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): severe biventricular dysfunction, augmented T1 mapping, and signs of acute myocarditis |

| 23 March | Myocardial biopsy of the right ventricle was performed. Subsequent histology revealed mild lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and diffuse platelet clots. Parvovirus B-19 DNA was detected while SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not |

| 24 March | Levosimendan 0.5 μg/kg/min was administered for 24 h because of persistent severe ventricular impairment and intense fatigue |

| 25 March | The case was discussed with an immuno-rheumatologist. Subcutaneous Anakinra 100 mg bid was started |

| 01 April | Patients’ clinical conditions and blood tests ameliorated. Echocardiography revealed significant improvement of global systolic biventricular function |

| 05 April | The patient was discharged with optimal medical therapy for heart failure and 6-month subcutaneous IL-1 inhibitor (ANAKINRA) |

| July | First follow-up: good clinical conditions, mild effort dyspnoea, stable improvement of biventricular function at the MRI (left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) 47%, right ventricle ejection fraction (RVEF) 48%] with normalization of T1 mapping |

| December | Second follow-up: good clinical conditions. No more dyspnoea for mild effort. Cardiac MRI: normalization of biventricular function (LVEF 55%, RVEF 56%) |

Case presentation

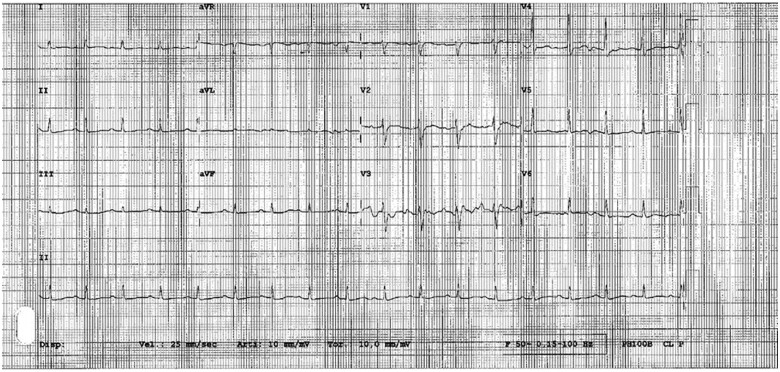

A 45-year-old healthy male (body mass index 24.7), without any previous medical history, was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of our hospital with shortness of breath, confusion, and severe asthenia. Arterial blood pressure was 75/50 mmHg, heart rate 120 beats per minute, and peripheral oxygen saturation 85% in room air. Medical examination revealed diffuse bilateral reduction in vesicular breath sounds and tachypnoea. Axillary temperature was 37.8°C. The ECG showed sinus tachycardia with diffuse repolarization abnormalities and low peripheral voltages (Figure 1). Blood analysis revealed mild leukocytosis (WBC 11.1 × 109/L, reference range 4.8–10.8 × 109/L) and thrombocytopenia (54 × 109/L, reference range 130–400 × 109/L); high sensitive troponin T was increased at seriate measurements (max 39 ng/dL, reference value <14 ng/dL), peak value of NT-proBNP was 17 000 pg/mL (reference value < 334 pg/mL), and C-reactive protein 285 mg/L (reference value < 6 mg/L) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

ECG at admission.

Table 1.

Main laboratory and instrumental findings during the hospital stay, at discharge, and at follow-up

| Value | Hospital stay (worst value) | Discharge | Follow-up (3 and 8 months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hs-troponin T (ref. 0–14 ng/dL) | 39 | Normal | Normal |

| Lactate (ref. <2 mmol/L) | 9 | Normal | Not tested |

| NT-proBNP (ref. <334 pg/dL) | 24 252 | 945 | 117–104 (normal) |

| CRP (ref <6 mg/L) | 285 | Normal | Normal |

| LVEF | 25% | 40–45% | 45–50% (3 months); 55% (8 months) |

| RVEF (MRI) | 29% | Not tested | 48% (3 months); 56% (8 months) |

CRP, C-reactive protein; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging, NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; RVEF, right ventricle ejection fraction; ref., reference value.

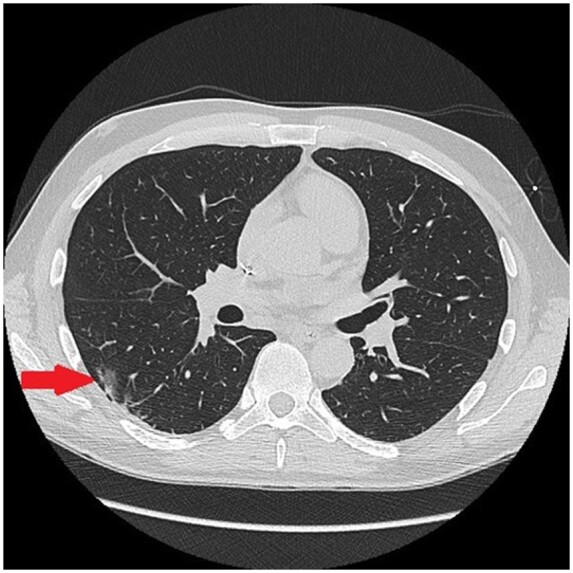

Chest X-ray revealed vascular congestion and very mild bilateral interstitial alterations. Transthoracic echocardiography was performed and highlighted severely impaired biventricular function [left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF): 25%, TAPSE 12 mm] with diffuse wall hypokinesia, mild biventricular dilatation, and no significant valvular disease. Thoracic and cardiac computed tomography (CT) showed minute bilateral ground-glass opacities (Figure 2) in the absence of coronary artery stenosis or aortic disease. A first nasopharyngeal swab for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection was performed and tested negative. Epidemiological investigation revealed that the patient spent a few days of ‘home working’ with a colleague of Lodi, one of the most affected cities by the epidemic outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in Lombardia, Italy. The colleague’s parents had had fever without other symptoms some days before. Because of the high suspicion of COVID-19, based on the findings of the CT and the epidemiological history, a bronchoalveolar lavage was also done and SARS-CoV-2 RNA was then detected. Simultaneous and subsequent nasopharyngeal swabs always resulted negative. Repeated blood cultures never isolated any microorganism.

Figure 2.

Chest computed tomography. Nuanced peripheral ground-glass opacities (arrow) compatible with very mild COVID-19 pneumonia.

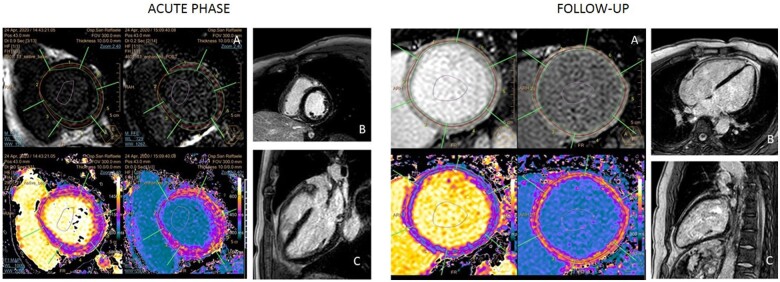

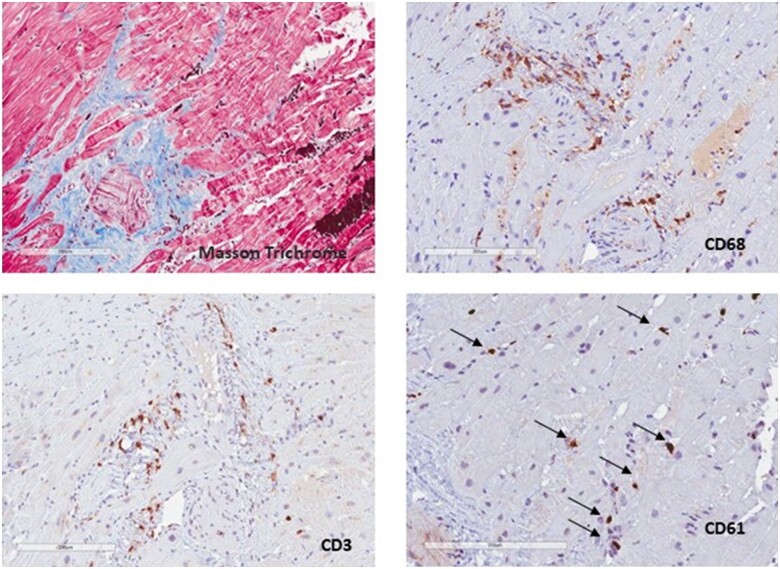

The patient was treated with non-invasive mechanical ventilation, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid (commonly used in March 2020 at our hospital for COVID-19), and large-spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy in the suspicion of cardio-septic shock. He needed mechanical circulatory support with intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) on top of inotropes (noradrenaline 0.15 μg/kg/min and adrenaline 0.15 μg/kg/min) because of worsening hypotension and severe metabolic acidosis with hyper-lactacidaemia (pH 7.26, base excess −10 mmol/L, lactates 9 mmol/L). Mechanical circulatory support was first attempted by IABP insertion due to its low rate of possible related vascular complications compared to Impella pump. About 1 week later, weaned from IABP and inotropes, he was transferred to the Clinical Cardiology department and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, confirming the severe impairment of biventricular global function associated with higher values of T1 and T2 mapping, in the absence of late gadolinium enhancement (findings compatible with acute myocarditis) (Figure 3). Myocardial biopsy (of the right ventricle) showed very mild lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate without myocardial necrosis, suggestive for myocarditis associated with very unusual diffuse platelets clots (Figure 4); parvovirus B19 DNA, but not SARS-CoV-2 RNA, was detected in the cardiac tissue by polymerase chain reaction. Intravenous continuous infusion of 0.05 μg/kg/min levosimendan for 24 h was administered. After collegial discussion with an immunology consultant and the patient, off-label therapy with subcutaneous IL-1 inhibitor (Anakinra 100 mg b.i.d.) was started. Few days later echocardiography was repeated, showing significant improvement in biventricular global function (LVEF = 40–45%, TAPSE 18 mm). No arrhythmias were recorded during the whole hospital stay and the patient was finally discharged asymptomatic with guidelines optimal medical therapy for heart failure (Metoprolol 50 mg daily, Ramipril 2.5 mg daily, Spironolactone 37 mg daily, Furosemide 25 mg daily) and a 6-month therapy with IL-1 inhibitor (Anakinra 100 mg daily). At the 3-month follow-up, cardiac MRI was repeated, confirming biventricular global function improvement, absence of late gadolinium enhancement and, finally, T1 and T2 mapping signals normalization (Figure 3). At 8 months of follow-up complete recovery of biventricular function was observed (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Cardiac magnetic resonance during the acute phase. (A) High basal left ventricle native T1 mapping values. The same trend was observed in mid-ventricular and apical sections. (B and C) Absence of late gadolinium enhancement. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging at the follow-up. (A) normalization of basal left ventricle native T1 mapping values. The same was observed in mid-ventricular and apical sections. (B and C) Absence of late gadolinium enhancement.

Figure 4.

Myocardial biopsy. Masson trichrome stain shows mild perivascular fibrosis. CD68 and CD3 show monocytes–macrophages and CD3 inflammatory infiltrate, mostly perivascular. CD61 positive platelets form microclots (arrows).

Discussion

During the ongoing epidemic, different cases of SARS-CoV-2 myocarditis have been reported. Our case report presents several peculiarities. First, it confirms the well-known low diagnostic accuracy of the nasopharyngeal swab for coronavirus detection. Despite this is the most common test used for active viral infection detection, its sensitivity is quite low.1 Apart from the result of nasopharyngeal swab, it is important to consider patients’ clinical history, clinical status, and instrumental findings.2 In this case, an accurate patient medical history collection, associated with thoracic CT findings, made the suspicion of COVID-19 infection very high, which was subsequently confirmed by an invasive diagnostic technique.

Another interesting key point is the observed histological myocardial injury in our patient. It has already been demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection can directly cause myocarditis and myocardial injury event in the absence of nasopharyngeal swab positivity.3 However, in the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection, myocardial injury is mostly mediated by indirect mechanisms.4,5 In our patient, Parvovirus B-19 DNA was detected in the myocardial tissue. However, Parvovirus B-19 myocarditis is often a benign, self-limiting disease and Parvovirus-DNA is frequently incidentally detected in the myocardial tissue of patients without evident myocardial injury or myocarditis and clinical correlates.6,7 Therefore, it is very likely that the severe impairment of cardiac function in our patient was the result of the massive cytokine storm caused by COVID-19. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not detected in endomyocardial biopsy and myocarditis was microscopically characterized by mild lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, thus supporting the indirect damage hypothesis. Additionally, platelet microclots were observed in myocardial tissue, a finding strictly related to the ‘Microvascular COVID-19 vessels obstructive thrombo-inflammatory syndrome’ hypothesis. This condition can hit lung and other organs,8 and probably contributes to global myocardial distress.

The final interesting point is the therapeutic strategy we chose for our patient after the initial mechanical support in the ICU. In this setting, apart from standard medical therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers, no specific treatments are indicated for acute myocarditis. In severely impaired ventricular function, there are anecdotal reports that intravenous levosimendan can improve biventricular function.9 In our case, we observed a dramatic improvement from 25% to 40–45% of left ventricular ejection fraction during the hospital stay. However, our concern was the potential transient positive inotropic effect of levosimendan. After an accurate discussion with an immunology consultant and the patient eliciting risks and benefits, once obtained his informed consent, we decided to use the IL-1 inhibitor Anakinra to counteract the inflammatory burden triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection.10 Patient had been already treated by hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid while high dose steroids had not yet been introduced into COVID-19 therapy during the first wave of the pandemic. Literature showed that IL-1 inhibition was associated with a significant reduction of mortality in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19, respiratory insufficiency, and hyper-inflammation, compared to standard immunosuppressive therapy.11 This therapeutic approach was well tolerated and led to a stable complete recovery of ventricular function at the 3- and 8-month follow-up. Anakinra has already been evaluated in a pilot study for the treatment of autoimmune myocarditis with positive results.12 A double blind, randomized, phase IIb placebo-controlled clinical trial of Anakinra in patients with acute myocarditis is ongoing and we expect it will clarify the role of this drug as a specific treatment for the acute, inflammatory phase of myocarditis.13

Conclusions

The severe impairment of cardiac function in our patient was the result of the massive cytokine storm caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Platelet microclots were observed in myocardial tissue, related to the ‘Microvascular COVID-19 vessels obstructive thrombo-inflammatory syndrome’, contributing to myocardial distress. A therapeutic strategy with an IL-1 inhibitor to counteract the disease-related cytokine burden can lead to an important and stable improvement of cardiac function. Controlled clinical studies are needed to confirm this thesis.

Lead author biography

Dr Giorgio Fiore is a 27-year-old resident in Cardiology working at San Raffaele University Hospital in Milan, Italy. He graduated from Federico II University in Napoli, Italy. He has studied for an academic year at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, with the Erasmus study project. After that he also performed a fellowship at the Division of Cardiology of University Hospitals of Coimbra (CHUC), Portugal. His area of interest spreads within clinical cardiology, arrhythmology, heart failure, and intensive cardiovascular care.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr G. De Luca and Dr C. Campochiaro for their precious contribution in the choice of therapeutic strategy.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

References

- 1. Gopaul R, Davis J, Gangai L, Goetz L.. Practical diagnostic accuracy of nasopharyngeal swab testing for novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). West J Emerg Med 2020;21:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Y, Yang M, Shen C, Wang F, Yuan J, Li J. et al. Evaluating the accuracy of different respiratory specimens in the laboratory diagnosis and monitoring the viral shedding of 2019-nCoV infections. Innovation (N Y) 2020;1:100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wenzel P, Kopp S, Göbel S, Jansen T, Geyer M, Hahn F. et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA in endomyocardial biopsies of patients with clinically suspected myocarditis tested negative for COVID-19 in nasopharyngeal swab. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:1661–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, Russak AJ, Paranjpe I, Richter F. et al. ; Mount Sinai COVID Informatics Center. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:2043–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Gill D, Walker J, Tarighati Rasekhi R, Bozorgnia B, Amanullah A.. Myocardial injury and COVID-19: possible mechanisms. Life Sci 2020;253:117723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schenk T, Enders M, Pollak S, Hahn R, Huzly D.. High prevalence of human parvovirus B19 DNA in myocardial autopsy samples from subjects without myocarditis or dilative cardiomyopathy. J Clin Microbiol 2009;47:106–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lotze U, Egerer R, Gluck B, Zell R, Sigusch H, Erhardt C. et al. Low level myocardial parvovirus B19 persistence is a frequent finding in patients with heart disease but unrelated to ongoing myocardial injury. J Med Virol 2010;82:1449–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ciceri F, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, Colombo S, Landoni G, Ruggeri A. et al. Microvascular COVID19 lung vessels obstructive thromboinflammatory syndrome (MicroCLOTS): an atypical acute respiratory distress syndrome working hypothesis. Crit Care Resusc 2020;22:95–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ercan S, Davutoglu V, Cakici M, Kus E, Alici H, Sari I.. Rapid recovery from acute myocarditis under levosimendan treatment: report of two cases. J Clin Pharm Ther 2013;38:179–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Della-Torre E, Ripa M, Canetti D. et al. Interleukin 1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2020;2:e325–e331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cavalli G, Larcher A, Tomelleri A, Campochiaro C, Della Torre E, De Luca G. et al. Interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 inhibition compared with standard management in patients with COVID-19 and hyperinflammation: a cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2021;3:e253–e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Luca G, Campochiaro C, Cavalli G, Sartorelli S, Dagna L. et al. Efficacy and safety of anakinra in the treatment of autoimmune myocarditis. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:576. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anakinra versus Placebo for the Treatment of Acute MyocarditIS (ARAMIS). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03018834.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.